Lecture 3a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 45

WORLD ENGLISHES

WORLD ENGLISHES

SCOTTISH ENGLISH, SHORT FORMS SCOE, SCE. The English language as used in Scotland

SCOTTISH ENGLISH, SHORT FORMS SCOE, SCE. The English language as used in Scotland

PRONUNCIATION. IN MANY WAYS, THE CONSERVATIVE SCOE ACCENT IS PHONOLOGICALLY CLOSE TO SCOTS, WHILE IN OTHERS IT HAS DEPARTED FROM IT (1) The Sco. E accent is rhotic, and all the vowels and diphthongs appear unchanged before /r/: beard /bird/, laird /lerd/, lard /lard/, moored /murd/, bird /bird/. (2) In some speakers, initial /p, t, k/ are unaspirated.

PRONUNCIATION. IN MANY WAYS, THE CONSERVATIVE SCOE ACCENT IS PHONOLOGICALLY CLOSE TO SCOTS, WHILE IN OTHERS IT HAS DEPARTED FROM IT (1) The Sco. E accent is rhotic, and all the vowels and diphthongs appear unchanged before /r/: beard /bird/, laird /lerd/, lard /lard/, moored /murd/, bird /bird/. (2) In some speakers, initial /p, t, k/ are unaspirated.

PRONUNCIATION (3) There is no distinction between cam and calm, both having /a/, between cot and caught, both having /o/, and between full and fool, both having /u/. (4) The monophthongs and diphthongs total 14 vowel sounds, perhaps the smallest vowel system of any longestablished variety of English.

PRONUNCIATION (3) There is no distinction between cam and calm, both having /a/, between cot and caught, both having /o/, and between full and fool, both having /u/. (4) The monophthongs and diphthongs total 14 vowel sounds, perhaps the smallest vowel system of any longestablished variety of English.

PRONUNCIATION (5) Sco. E retains from Scots the voiceless velar fricative /x/: for example, in such names as Brechin and Mac. Lachlan, such Gaelicisms as loch and pibroch, such Scotticisms as dreich and sough. (6) The wh- in such words as whale, what, why is pronounced /hw/ and such pairs as which/witch are sharply distinguished.

PRONUNCIATION (5) Sco. E retains from Scots the voiceless velar fricative /x/: for example, in such names as Brechin and Mac. Lachlan, such Gaelicisms as loch and pibroch, such Scotticisms as dreich and sough. (6) The wh- in such words as whale, what, why is pronounced /hw/ and such pairs as which/witch are sharply distinguished.

GRAMMAR. FEATURES OF PRESENT-DAY SCOTS GRAMMAR ARE CARRIED OVER INTO SCOE: (1) Passives. The passive may be expressed by get: I got told off. (2) Negatives. Sco. E not is favoured over -n't: He'll not come in preference to He won't come, You're not wanted to You aren't wanted, and similarly Is he not coming? Can you not come? Do you not want it? Did he not come? Not may negate a main verb as well as an auxiliary: He isn't still not working? ; Nobody would dream of not obeying.

GRAMMAR. FEATURES OF PRESENT-DAY SCOTS GRAMMAR ARE CARRIED OVER INTO SCOE: (1) Passives. The passive may be expressed by get: I got told off. (2) Negatives. Sco. E not is favoured over -n't: He'll not come in preference to He won't come, You're not wanted to You aren't wanted, and similarly Is he not coming? Can you not come? Do you not want it? Did he not come? Not may negate a main verb as well as an auxiliary: He isn't still not working? ; Nobody would dream of not obeying.

Pronouns in -self may be used nonreflexively: How's yourself today? Is himself in? (Is the man of the house at home? ). (4) Anybody, everybody, nobody, somebody are preferred to anyone, everyone, no one, someone. (5) Amn't I? is used virtually to the exclusion of aren't I? : I’m expected too, amn't I? (3)

Pronouns in -self may be used nonreflexively: How's yourself today? Is himself in? (Is the man of the house at home? ). (4) Anybody, everybody, nobody, somebody are preferred to anyone, everyone, no one, someone. (5) Amn't I? is used virtually to the exclusion of aren't I? : I’m expected too, amn't I? (3)

VOCABULARY AND IDIOM. THERE IS A CONTINUUM OF SCOE LEXICAL USAGE, FROM THE MOST TO THE LEAST INTERNATIONAL: There is a continuum of Sco. E lexical usage, from the most to the least international: (1) Words of original Scottish provenance used in the language at large for so long that few people think of them as Sco. E: caddie, collie , cosy, croon, eerie, glamour, golf, pony, raid, , weird. (2) Words widely used or known and generally perceived to be Scottish: cairn, clan, gloaming, kilt, whisky. (3) Words that have some external currency but are used more in Scotland than elsewhere, many as covert Scotticisms: brae, canny, douce.

VOCABULARY AND IDIOM. THERE IS A CONTINUUM OF SCOE LEXICAL USAGE, FROM THE MOST TO THE LEAST INTERNATIONAL: There is a continuum of Sco. E lexical usage, from the most to the least international: (1) Words of original Scottish provenance used in the language at large for so long that few people think of them as Sco. E: caddie, collie , cosy, croon, eerie, glamour, golf, pony, raid, , weird. (2) Words widely used or known and generally perceived to be Scottish: cairn, clan, gloaming, kilt, whisky. (3) Words that have some external currency but are used more in Scotland than elsewhere, many as covert Scotticisms: brae, canny, douce.

WELSH ENGLISH. THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AS USED IN WALES. Pronunciation. Accent varies according to region, ethnicity, and education. RP is spoken mainly by English expatriates and its influence is strongest in the south-east. The following generalizations refer to the English of native Welsh people:

WELSH ENGLISH. THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE AS USED IN WALES. Pronunciation. Accent varies according to region, ethnicity, and education. RP is spoken mainly by English expatriates and its influence is strongest in the south-east. The following generalizations refer to the English of native Welsh people:

WELSH ENGLISH. PRONUNCIATION. (1) Speakers of Welsh are often described as having a lilting singsong intonation in their English, an effect created by three tendencies: a rise-fall tone at the end of statements (where RP has a fall); long vowels only in stressed syllables, the vowels in the second syllables of such words as 'increase and 'expert being short; reduced vowels avoided in polysyllabic words, speakers preferring, for example, /tiket/ for ticket and /konekjon/ for connection. (2) Welsh English is usually non-rhotic, but people who regularly speak Welsh are likely to have a postvocalic r (in such words as worker).

WELSH ENGLISH. PRONUNCIATION. (1) Speakers of Welsh are often described as having a lilting singsong intonation in their English, an effect created by three tendencies: a rise-fall tone at the end of statements (where RP has a fall); long vowels only in stressed syllables, the vowels in the second syllables of such words as 'increase and 'expert being short; reduced vowels avoided in polysyllabic words, speakers preferring, for example, /tiket/ for ticket and /konekjon/ for connection. (2) Welsh English is usually non-rhotic, but people who regularly speak Welsh are likely to have a postvocalic r (in such words as worker).

(3) The accents of South Wales are generally aitchless. In North Wales, word-initial /h/ is not usually dropped, partly because it occurs in Welsh. (4) There is a tendency towards the monophthongs /e/ and /o/ and away from the diphthongs /ei/ and /au/ in such words as late and hope. (5) The vowel /a/ is often used for both gas and glass. (6) There is a preference for /u/ over /ju/ in such words as actually /aktuali/ and speculate /spekulet/.

(3) The accents of South Wales are generally aitchless. In North Wales, word-initial /h/ is not usually dropped, partly because it occurs in Welsh. (4) There is a tendency towards the monophthongs /e/ and /o/ and away from the diphthongs /ei/ and /au/ in such words as late and hope. (5) The vowel /a/ is often used for both gas and glass. (6) There is a preference for /u/ over /ju/ in such words as actually /aktuali/ and speculate /spekulet/.

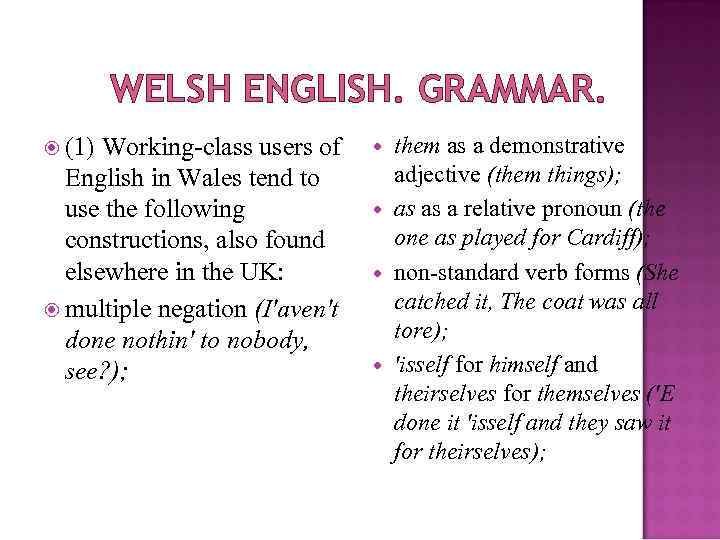

WELSH ENGLISH. GRAMMAR. (1) Working-class users of English in Wales tend to use the following constructions, also found elsewhere in the UK: multiple negation (I'aven't done nothin' to nobody, see? ); them as a demonstrative adjective (them things); as as a relative pronoun (the one as played for Cardiff); non-standard verb forms (She catched it, The coat was all tore); 'isself for himself and theirselves for themselves ('E done it 'isself and they saw it for theirselves);

WELSH ENGLISH. GRAMMAR. (1) Working-class users of English in Wales tend to use the following constructions, also found elsewhere in the UK: multiple negation (I'aven't done nothin' to nobody, see? ); them as a demonstrative adjective (them things); as as a relative pronoun (the one as played for Cardiff); non-standard verb forms (She catched it, The coat was all tore); 'isself for himself and theirselves for themselves ('E done it 'isself and they saw it for theirselves);

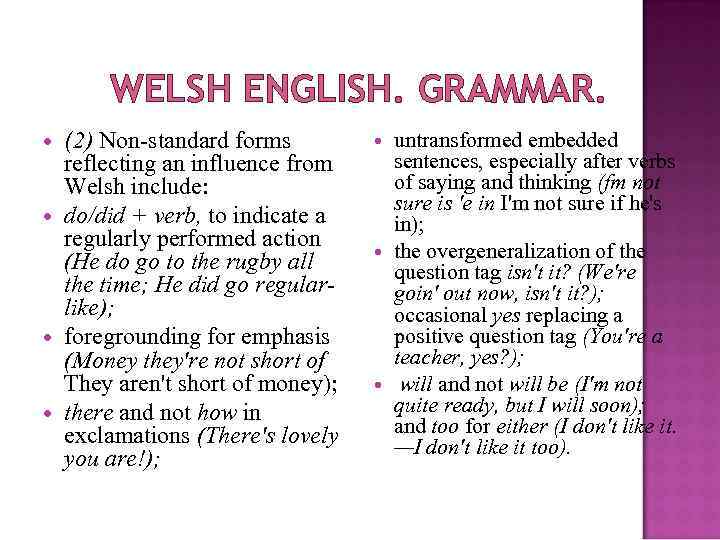

WELSH ENGLISH. GRAMMAR. (2) Non-standard forms reflecting an influence from Welsh include: do/did + verb, to indicate a regularly performed action (He do go to the rugby all the time; He did go regularlike); foregrounding for emphasis (Money they're not short of They aren't short of money); there and not how in exclamations (There's lovely you are!); untransformed embedded sentences, especially after verbs of saying and thinking (fm not sure is 'e in I'm not sure if he's in); the overgeneralization of the question tag isn't it? (We're goin' out now, isn't it? ); occasional yes replacing a positive question tag (You're a teacher, yes? ); will and not will be (I'm not quite ready, but I will soon); and too for either (I don't like it. —I don't like it too).

WELSH ENGLISH. GRAMMAR. (2) Non-standard forms reflecting an influence from Welsh include: do/did + verb, to indicate a regularly performed action (He do go to the rugby all the time; He did go regularlike); foregrounding for emphasis (Money they're not short of They aren't short of money); there and not how in exclamations (There's lovely you are!); untransformed embedded sentences, especially after verbs of saying and thinking (fm not sure is 'e in I'm not sure if he's in); the overgeneralization of the question tag isn't it? (We're goin' out now, isn't it? ); occasional yes replacing a positive question tag (You're a teacher, yes? ); will and not will be (I'm not quite ready, but I will soon); and too for either (I don't like it. —I don't like it too).

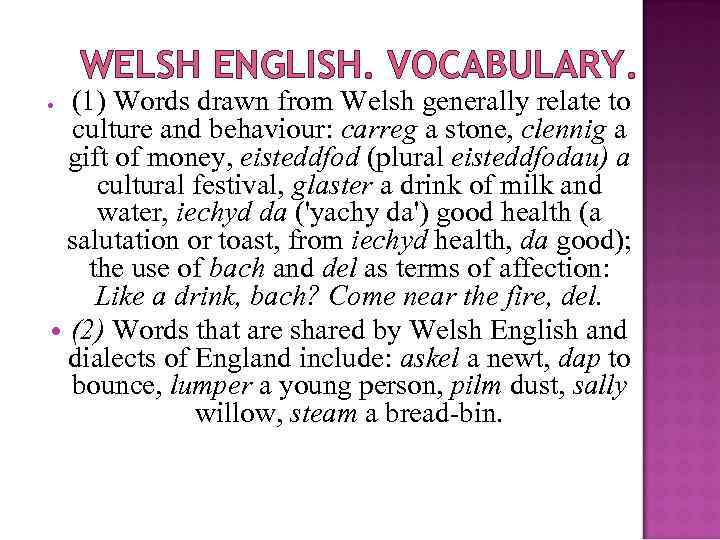

WELSH ENGLISH. VOCABULARY. (1) Words drawn from Welsh generally relate to culture and behaviour: carreg a stone, clennig a gift of money, eisteddfod (plural eisteddfodau) a cultural festival, glaster a drink of milk and water, iechyd da ('yachy da') good health (a salutation or toast, from iechyd health, da good); the use of bach and del as terms of affection: Like a drink, bach? Come near the fire, del. (2) Words that are shared by Welsh English and dialects of England include: askel a newt, dap to bounce, lumper a young person, pilm dust, sally willow, steam a bread-bin.

WELSH ENGLISH. VOCABULARY. (1) Words drawn from Welsh generally relate to culture and behaviour: carreg a stone, clennig a gift of money, eisteddfod (plural eisteddfodau) a cultural festival, glaster a drink of milk and water, iechyd da ('yachy da') good health (a salutation or toast, from iechyd health, da good); the use of bach and del as terms of affection: Like a drink, bach? Come near the fire, del. (2) Words that are shared by Welsh English and dialects of England include: askel a newt, dap to bounce, lumper a young person, pilm dust, sally willow, steam a bread-bin.

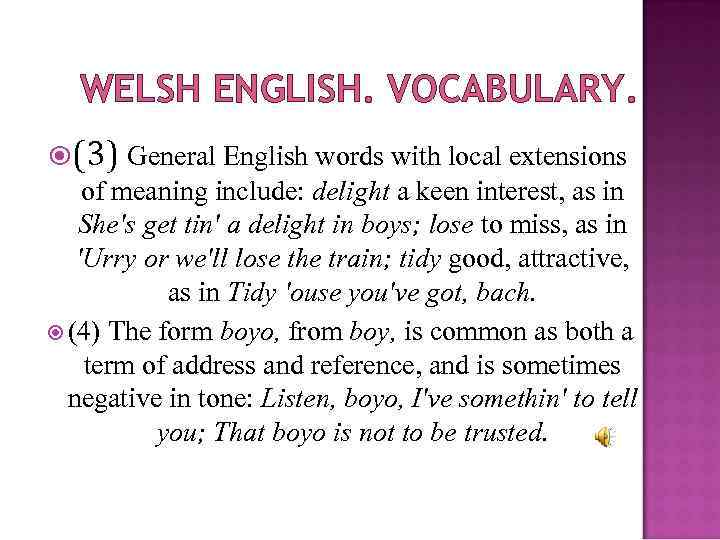

WELSH ENGLISH. VOCABULARY. (3) General English words with local extensions of meaning include: delight a keen interest, as in She's get tin' a delight in boys; lose to miss, as in 'Urry or we'll lose the train; tidy good, attractive, as in Tidy 'ouse you've got, bach. (4) The form boyo, from boy, is common as both a term of address and reference, and is sometimes negative in tone: Listen, boyo, I've somethin' to tell you; That boyo is not to be trusted.

WELSH ENGLISH. VOCABULARY. (3) General English words with local extensions of meaning include: delight a keen interest, as in She's get tin' a delight in boys; lose to miss, as in 'Urry or we'll lose the train; tidy good, attractive, as in Tidy 'ouse you've got, bach. (4) The form boyo, from boy, is common as both a term of address and reference, and is sometimes negative in tone: Listen, boyo, I've somethin' to tell you; That boyo is not to be trusted.

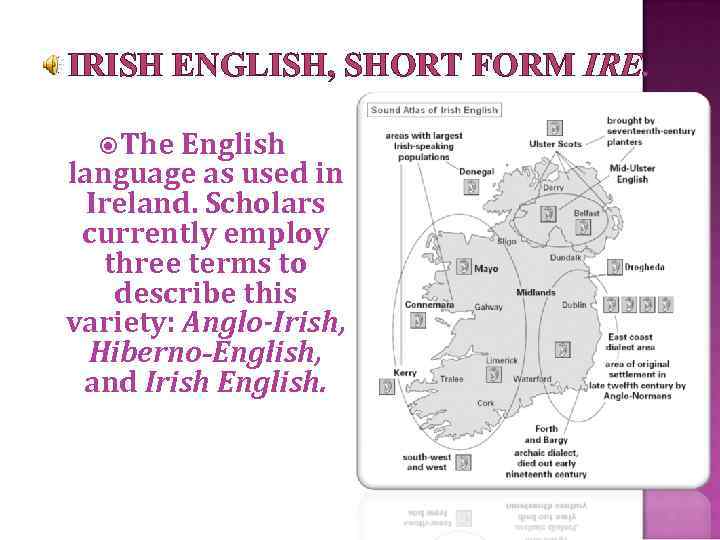

IRISH ENGLISH, SHORT FORM IRE. The English language as used in Ireland. Scholars currently employ three terms to describe this variety: Anglo-Irish, Hiberno-English, and Irish English.

IRISH ENGLISH, SHORT FORM IRE. The English language as used in Ireland. Scholars currently employ three terms to describe this variety: Anglo-Irish, Hiberno-English, and Irish English.

MODELS OF PRONUNCIATION. In pronunciation, three main models are followed: (1) Received Pronunciation. Two small groups of people have RP accents: men educated in England, especially in the public (private) schools, and some individuals in the media. (2) Received Irish Pronunciation. A rhotic accent and the prestige pronunciation of Radio Telefis Eireann (Irish Radio and Television). It is closer to RP than other varieties of Irish speech and is favoured by middle-class speakers of Anglo-Irish. (3) Received Ulster Pronunciation. In Northern Ireland, many broadcasters speak standard English with a regional accent and are more influential as models than speakers of RP.

MODELS OF PRONUNCIATION. In pronunciation, three main models are followed: (1) Received Pronunciation. Two small groups of people have RP accents: men educated in England, especially in the public (private) schools, and some individuals in the media. (2) Received Irish Pronunciation. A rhotic accent and the prestige pronunciation of Radio Telefis Eireann (Irish Radio and Television). It is closer to RP than other varieties of Irish speech and is favoured by middle-class speakers of Anglo-Irish. (3) Received Ulster Pronunciation. In Northern Ireland, many broadcasters speak standard English with a regional accent and are more influential as models than speakers of RP.

BILINGUAL SIGNS Since the Irish Republic is officially bilingual, English appears widely with Irish on public buildings and signs, and on official forms and documents, as in the following pairs on notice-boards at Dublin Airport: Shops/Siopai, Bar/Bear, Snacksj. Solaisti, Post Office/Oifig an Phoist, Telephones/Telefoin, Information/

BILINGUAL SIGNS Since the Irish Republic is officially bilingual, English appears widely with Irish on public buildings and signs, and on official forms and documents, as in the following pairs on notice-boards at Dublin Airport: Shops/Siopai, Bar/Bear, Snacksj. Solaisti, Post Office/Oifig an Phoist, Telephones/Telefoin, Information/

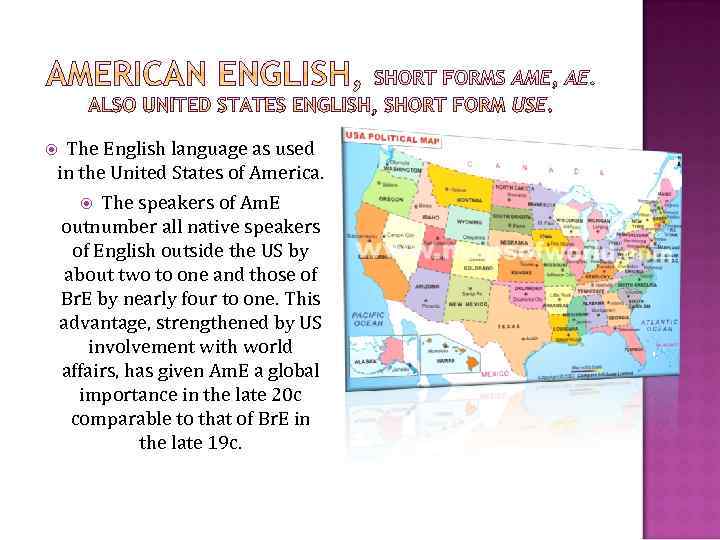

The English language as used in the United States of America. The speakers of Am. E outnumber all native speakers of English outside the US by about two to one and those of Br. E by nearly four to one. This advantage, strengthened by US involvement with world affairs, has given Am. E a global importance in the late 20 c comparable to that of Br. E in the late 19 c.

The English language as used in the United States of America. The speakers of Am. E outnumber all native speakers of English outside the US by about two to one and those of Br. E by nearly four to one. This advantage, strengthened by US involvement with world affairs, has given Am. E a global importance in the late 20 c comparable to that of Br. E in the late 19 c.

falls into three periods, whose dates correspond to political and social events with important consequences for the language: (1) The Colonial Period, during which a distinctive Am. E was gestating. (2) The National Period, which saw its birth, establishment, and consolidation. (3) The International Period, during which it has come increasingly under foreign influence and has exerted influence on the varieties of English and on other languages.

falls into three periods, whose dates correspond to political and social events with important consequences for the language: (1) The Colonial Period, during which a distinctive Am. E was gestating. (2) The National Period, which saw its birth, establishment, and consolidation. (3) The International Period, during which it has come increasingly under foreign influence and has exerted influence on the varieties of English and on other languages.

Variation within Am. E is far less than within many other national languages. Although Americans are conscious of the odd way their fellow citizens in other communities talk, considering the size and population of the US, its language is relatively homogeneous. Yet there are distinctive speechways in particular communities: the Boston Brahmins, the old families of New England who pride themselves on their culture and conservative attitudes and are noted for their haughtiness

Variation within Am. E is far less than within many other national languages. Although Americans are conscious of the odd way their fellow citizens in other communities talk, considering the size and population of the US, its language is relatively homogeneous. Yet there are distinctive speechways in particular communities: the Boston Brahmins, the old families of New England who pride themselves on their culture and conservative attitudes and are noted for their haughtiness

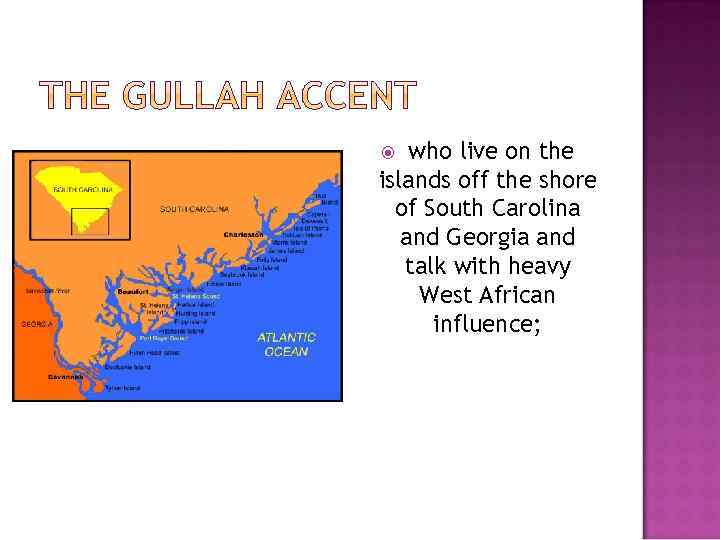

who live on the islands off the shore of South Carolina and Georgia and talk with heavy West African influence;

who live on the islands off the shore of South Carolina and Georgia and talk with heavy West African influence;

the Appalachian mountain people the Tex-Mex broncobusters the laid-back lifestylers of Marin County, California; the Charlestonian Old South aristocracy; the inner-city African Americans the Minnesota Swedes the Chicanos of the Southwest

the Appalachian mountain people the Tex-Mex broncobusters the laid-back lifestylers of Marin County, California; the Charlestonian Old South aristocracy; the inner-city African Americans the Minnesota Swedes the Chicanos of the Southwest

Beneath the relative uniformity of its standard, edited variety, American English is a rich gallimaufry of exotic and native stuffs. Underlying the regional accents of the US are some widespread features that are typical of Am. E: (1) With the exception of the Southern states, eastern New England, and New York City, pronunciation is rhotic, postvocalic /r/ being pronounced in such words as part, four, motor. (2) The Am. E /r/ is retroflex, and is often lost after an unstressed vowel if another /r/ follows: the r in govern is pronounced but is dropped in governor. (3) In words like path, can't, dance, Am. E generally has the vowel of pat and cant.

Beneath the relative uniformity of its standard, edited variety, American English is a rich gallimaufry of exotic and native stuffs. Underlying the regional accents of the US are some widespread features that are typical of Am. E: (1) With the exception of the Southern states, eastern New England, and New York City, pronunciation is rhotic, postvocalic /r/ being pronounced in such words as part, four, motor. (2) The Am. E /r/ is retroflex, and is often lost after an unstressed vowel if another /r/ follows: the r in govern is pronounced but is dropped in governor. (3) In words like path, can't, dance, Am. E generally has the vowel of pat and cant.

Some widespread features that are typical of Am. E (4) The vowels of the stressed syllables in such words as, father ['fäT Hər] and fodder ['fädər] are generally identical. (5) A /d/ typically occurs where the spelling has t or tt in words like latter, atom, metal, bitty, which are homophonous with ladder, Adam, medal, biddy. (6) Similarly, /t/ is often lost from /nt/ in winter ('winner'), and international ('innernational').

Some widespread features that are typical of Am. E (4) The vowels of the stressed syllables in such words as, father ['fäT Hər] and fodder ['fädər] are generally identical. (5) A /d/ typically occurs where the spelling has t or tt in words like latter, atom, metal, bitty, which are homophonous with ladder, Adam, medal, biddy. (6) Similarly, /t/ is often lost from /nt/ in winter ('winner'), and international ('innernational').

(1) A simple preterite rather than a perfect form is sometimes used for action leading up to the present time, even with adverbs: Did you ever hear that? ; I already did it. (2) In formal mandative constructions, with clauses following verbs, adjectives, and nouns of requiring and urging, Am. E prefers the present subjunctive form: They insisted that he go with them, It is imperative that you be here on time.

(1) A simple preterite rather than a perfect form is sometimes used for action leading up to the present time, even with adverbs: Did you ever hear that? ; I already did it. (2) In formal mandative constructions, with clauses following verbs, adjectives, and nouns of requiring and urging, Am. E prefers the present subjunctive form: They insisted that he go with them, It is imperative that you be here on time.

(3) When the subject of a clause is a collective noun, there is generally a singular verb, in concord with the form rather than the sense of the subject: The airline insists. . . ; The government is. . . (4) The u s e o f prepositions is often distinctive: Americans live on a street (Br. E in), do things on the weekend (Br. E at), are of two minds about something (Br. E in), have a new lease on life (Br. E of), and when mentioning dates when things happen, may use or omit on (Jack went home on Monday and came back Thursday).

(3) When the subject of a clause is a collective noun, there is generally a singular verb, in concord with the form rather than the sense of the subject: The airline insists. . . ; The government is. . . (4) The u s e o f prepositions is often distinctive: Americans live on a street (Br. E in), do things on the weekend (Br. E at), are of two minds about something (Br. E in), have a new lease on life (Br. E of), and when mentioning dates when things happen, may use or omit on (Jack went home on Monday and came back Thursday).

A distinctive vocabulary developed from the Colonial Period until the present, including: (1) Borrowing from Amerindian languages: chipmunk, hickory, moccasin, pecan, skunk, squash, totem, wigwam. Sometimes such words came through French: caribou, toboggan. (2) Borrowing from other colonial languages: French chowder, prairie; Dutch boss, coleslaw, cookie, Santa Claus, sleigh. (3) Borrowing from later immigrant languages: African goober, gumbo, juke; German (especially through Pennsylvania Dutch) noodle, sauerkraut, snorkel, and the fest and -burger endings in bookfest, cheeseburger, etc.

A distinctive vocabulary developed from the Colonial Period until the present, including: (1) Borrowing from Amerindian languages: chipmunk, hickory, moccasin, pecan, skunk, squash, totem, wigwam. Sometimes such words came through French: caribou, toboggan. (2) Borrowing from other colonial languages: French chowder, prairie; Dutch boss, coleslaw, cookie, Santa Claus, sleigh. (3) Borrowing from later immigrant languages: African goober, gumbo, juke; German (especially through Pennsylvania Dutch) noodle, sauerkraut, snorkel, and the fest and -burger endings in bookfest, cheeseburger, etc.

(4) Some typically Am. E words with complex histories: lagniappe, a term for a small present given by merchants to their customers, extended to any little extra benefit. Associated with the South, it is from Louisiana French, borrowed from Spanish la napa the gift, from Quechua yapa. A selection of words of American origin indicates the variety and significance of the Am. E contribution to English at large: airline, boondoggle, checklist, disco, expense account, flowchart, inner city, junk food, laser, mass meeting, ouch, pants, radio, soap opera, teddy bear, UFO, xerox, yuppie, zipper.

(4) Some typically Am. E words with complex histories: lagniappe, a term for a small present given by merchants to their customers, extended to any little extra benefit. Associated with the South, it is from Louisiana French, borrowed from Spanish la napa the gift, from Quechua yapa. A selection of words of American origin indicates the variety and significance of the Am. E contribution to English at large: airline, boondoggle, checklist, disco, expense account, flowchart, inner city, junk food, laser, mass meeting, ouch, pants, radio, soap opera, teddy bear, UFO, xerox, yuppie, zipper.

The English language as used in Canada. This national variety has coexisted for some 230 years with Canadian French, which is almost a century older, as well as with a range of indigenous languages such as Cree, Iroquois, and Inuktitut and a number of immigrant languages such as Italian and Ukrainian. It has been marked by the now less significant influence of Br. E and the enormous ongoing impact of Am. E. Because of the similarity of American and Canadian accents, English Canadians travelling abroad are virtually resigned to being taken for Americans. Because Can. E and Am. E are so alike, some scholars have argued that in linguistic terms Canadian English is no more or less than a variety of Northern American English. In addition, the environment of Can. E differs significantly from that of other varieties in two ways: (1) The presence of French as co-official language. (2) A preoccupation with the wilderness. An awareness of the great empty northern spaces exists even among urban Canadians.

The English language as used in Canada. This national variety has coexisted for some 230 years with Canadian French, which is almost a century older, as well as with a range of indigenous languages such as Cree, Iroquois, and Inuktitut and a number of immigrant languages such as Italian and Ukrainian. It has been marked by the now less significant influence of Br. E and the enormous ongoing impact of Am. E. Because of the similarity of American and Canadian accents, English Canadians travelling abroad are virtually resigned to being taken for Americans. Because Can. E and Am. E are so alike, some scholars have argued that in linguistic terms Canadian English is no more or less than a variety of Northern American English. In addition, the environment of Can. E differs significantly from that of other varieties in two ways: (1) The presence of French as co-official language. (2) A preoccupation with the wilderness. An awareness of the great empty northern spaces exists even among urban Canadians.

The main features of standard Can. E are: (1) Canadian Raising (a term coined by J. K. Chambers in 1973) is a convenient term for what is in fact a nonlowering of certain diphthongs that are lowered in most other dialects. The tongue is raised higher to produce the diphthong in knife, house than in knives, houses. In general terms, these diphthongs have a raised onset before voiceless consonants: and. In the following pairs, only the first word has the raised onset: tripe/tribe, bite/bide, tyke/tiger, knife/knives, price/prizes, lout/loud, mouth (n)/mouth (2) The cot/caught distinction. Many phonological features shared with Northern Am. E are distributed distinctively in standard Can. E: for example, the low back vowels have merged, so that Canadians pronounce cot/caught, Don/Dawn, awful/offal, caller/collar with the same vowel sound, although the quality of this sound varies.

The main features of standard Can. E are: (1) Canadian Raising (a term coined by J. K. Chambers in 1973) is a convenient term for what is in fact a nonlowering of certain diphthongs that are lowered in most other dialects. The tongue is raised higher to produce the diphthong in knife, house than in knives, houses. In general terms, these diphthongs have a raised onset before voiceless consonants: and. In the following pairs, only the first word has the raised onset: tripe/tribe, bite/bide, tyke/tiger, knife/knives, price/prizes, lout/loud, mouth (n)/mouth (2) The cot/caught distinction. Many phonological features shared with Northern Am. E are distributed distinctively in standard Can. E: for example, the low back vowels have merged, so that Canadians pronounce cot/caught, Don/Dawn, awful/offal, caller/collar with the same vowel sound, although the quality of this sound varies.

(3) T-flapping and T-deletion. Especially in casual speech, many Canadians, like many Americans, pronounce /t/ as /d/ between vowels and after /r/, a feature known as tflapping. Such pairs as waiting I wading, metal/medal, latter/ladder, hearty/hardy are therefore often homophones and the city of Ottawa is called 'Oddawa'. In addition, the /t/ is usually deleted after n, so that Toronto is pronounced 'Toronna' or 'Trawna' by most of the city's inhabitants. ( (4) Use of WH. Speakers of standard Can. E tend more than speakers of standard Northern Am. E to drop the distinction between initial /hw/ and /w/, making homophones out of which/witch.

(3) T-flapping and T-deletion. Especially in casual speech, many Canadians, like many Americans, pronounce /t/ as /d/ between vowels and after /r/, a feature known as tflapping. Such pairs as waiting I wading, metal/medal, latter/ladder, hearty/hardy are therefore often homophones and the city of Ottawa is called 'Oddawa'. In addition, the /t/ is usually deleted after n, so that Toronto is pronounced 'Toronna' or 'Trawna' by most of the city's inhabitants. ( (4) Use of WH. Speakers of standard Can. E tend more than speakers of standard Northern Am. E to drop the distinction between initial /hw/ and /w/, making homophones out of which/witch.

Where Can. E differs grammatically from Br. E it tends to agree with Am. E. However, where such differences exist, Canadians are often more aware of both usages than Americans, either because they use both or have been exposed to both.

Where Can. E differs grammatically from Br. E it tends to agree with Am. E. However, where such differences exist, Canadians are often more aware of both usages than Americans, either because they use both or have been exposed to both.

English Canadians have developed the vocabulary they have needed in their special environment by borrowing from indigenous languages: chipmunk, mackinaw (a bush jacket), moose, muskeg (boggy, mossy land), muskrat , kayak, mukluk, anorak, parka, malemute. and from French: caboteur (a ship engaged in coastal trade), cache (a place for storing supplies; a supply of goods kept for future use), coureur du bois (a French or Metis trader or woodsman), Metis (a person or people of'mixed' blood), portage (the carrying of canoes past rapids), by extending and adapting traditional English words: Native officially referring to the indigenous peoples of Canada (the Native Peoples); the distinction between prime minister (federal chief minister) and premier (provincial chief minister); province, provincial (referring to the major political divisions of the country, most of which were once distinct British colonies); riding (a political constituency); status Indian (someone officially registered as a Canadian Indian); Can. E reserve as opposed to Am. E reservation as a term describing land set aside for Native peoples. and by coining new words, in addition to which, Can. E vocabulary has been affected by institutional bilingualism.

English Canadians have developed the vocabulary they have needed in their special environment by borrowing from indigenous languages: chipmunk, mackinaw (a bush jacket), moose, muskeg (boggy, mossy land), muskrat , kayak, mukluk, anorak, parka, malemute. and from French: caboteur (a ship engaged in coastal trade), cache (a place for storing supplies; a supply of goods kept for future use), coureur du bois (a French or Metis trader or woodsman), Metis (a person or people of'mixed' blood), portage (the carrying of canoes past rapids), by extending and adapting traditional English words: Native officially referring to the indigenous peoples of Canada (the Native Peoples); the distinction between prime minister (federal chief minister) and premier (provincial chief minister); province, provincial (referring to the major political divisions of the country, most of which were once distinct British colonies); riding (a political constituency); status Indian (someone officially registered as a Canadian Indian); Can. E reserve as opposed to Am. E reservation as a term describing land set aside for Native peoples. and by coining new words, in addition to which, Can. E vocabulary has been affected by institutional bilingualism.

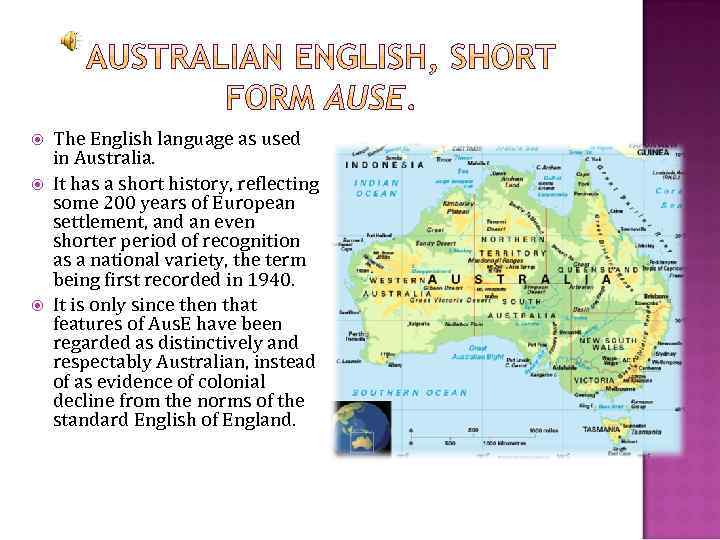

The English language as used in Australia. It has a short history, reflecting some 200 years of European settlement, and an even shorter period of recognition as a national variety, the term being first recorded in 1940. It is only since then that features of Aus. E have been regarded as distinctively and respectably Australian, instead of as evidence of colonial decline from the norms of the standard English of England.

The English language as used in Australia. It has a short history, reflecting some 200 years of European settlement, and an even shorter period of recognition as a national variety, the term being first recorded in 1940. It is only since then that features of Aus. E have been regarded as distinctively and respectably Australian, instead of as evidence of colonial decline from the norms of the standard English of England.

The most marked feature of the Australian accent is its homogeneity, with no regional differences as marked as those in Br. E and Am. E, though recent studies have associated particular phonological characteristics with state capitals. There is, however, a social continuum in which three varieties are generally recognized: Broad Australian, General Australian, and Cultivated Australian. Of these, Cultivated Australian most closely approaches British RP and Broad Australian most vigorously exhibits distinctive regional features. It is generally assumed that the Australian accent derives from the mixing of British and Irish accents in the early years of settlement.

The most marked feature of the Australian accent is its homogeneity, with no regional differences as marked as those in Br. E and Am. E, though recent studies have associated particular phonological characteristics with state capitals. There is, however, a social continuum in which three varieties are generally recognized: Broad Australian, General Australian, and Cultivated Australian. Of these, Cultivated Australian most closely approaches British RP and Broad Australian most vigorously exhibits distinctive regional features. It is generally assumed that the Australian accent derives from the mixing of British and Irish accents in the early years of settlement.

(1) It is non-rhotic (r is pronounced before a consonant (as in hard) and at the ends of words (as in far). (2) Its intonation is flatter than that of RP. (3) Speech rhythms are slow, stress being more evenly spaced than in RP. (4) Consonants do not differ significantly from those in RP. (5) Vowels are in general closer and more frontal than in RP, with /i/ and /u/ as in tea, two diphthongized əi and təu respectively. (6) The vowel in can't dance may be æ or a.

(1) It is non-rhotic (r is pronounced before a consonant (as in hard) and at the ends of words (as in far). (2) Its intonation is flatter than that of RP. (3) Speech rhythms are slow, stress being more evenly spaced than in RP. (4) Consonants do not differ significantly from those in RP. (5) Vowels are in general closer and more frontal than in RP, with /i/ and /u/ as in tea, two diphthongized əi and təu respectively. (6) The vowel in can't dance may be æ or a.

(7) The schwa is busier than in RP, frequently replacing /i/ in unaccented positions, as in boxes, dances, darkest, velvet, acid. (8) Some diphthongs shift, RP as in Australia, day, mate, and , as in high, wide. (9) Speakers whose first language is not English or who have a bilingual background (Aboriginal, immigrant) often use sounds and a delivery influenced by the patterns of the first or other language. (10) The name of the letter h is often pronounced 'haitch' by speakers wholly or partly of Irish-Catholic background.

(7) The schwa is busier than in RP, frequently replacing /i/ in unaccented positions, as in boxes, dances, darkest, velvet, acid. (8) Some diphthongs shift, RP as in Australia, day, mate, and , as in high, wide. (9) Speakers whose first language is not English or who have a bilingual background (Aboriginal, immigrant) often use sounds and a delivery influenced by the patterns of the first or other language. (10) The name of the letter h is often pronounced 'haitch' by speakers wholly or partly of Irish-Catholic background.

There are no syntactic features that distinguish standard Aus. E from standard Br. E, or indeed any major nonstandard features not also found in Britain, but there are many distinctive words and phrases. However, although Aus. E has added some 10, 000 items to the language, few have become internationally active. The largest demand for new words has concerned flora and fauna, and predominant occupations like stockraising have also required new terms. Because of this, Australianisms are predominantly naming words: single nouns (mulga , an acacia , mullock mining refuse, muster a round-up of livestock), compounds (black tracker an Aboriginal employed by the police to track down missing persons, black velvet Aboriginal women as sexual objects, red-back a spider), nouns used attributively (convict colony a penal colony, convict servant or convict slave a convict assigned as a servant).

There are no syntactic features that distinguish standard Aus. E from standard Br. E, or indeed any major nonstandard features not also found in Britain, but there are many distinctive words and phrases. However, although Aus. E has added some 10, 000 items to the language, few have become internationally active. The largest demand for new words has concerned flora and fauna, and predominant occupations like stockraising have also required new terms. Because of this, Australianisms are predominantly naming words: single nouns (mulga , an acacia , mullock mining refuse, muster a round-up of livestock), compounds (black tracker an Aboriginal employed by the police to track down missing persons, black velvet Aboriginal women as sexual objects, red-back a spider), nouns used attributively (convict colony a penal colony, convict servant or convict slave a convict assigned as a servant).

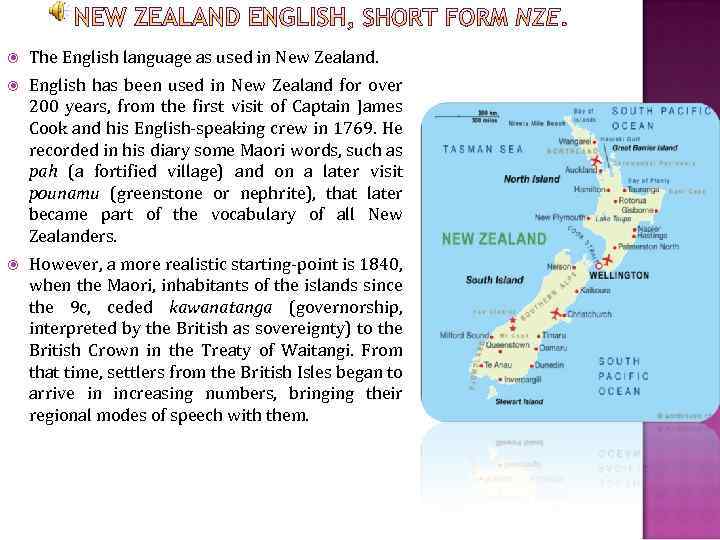

The English language as used in New Zealand. English has been used in New Zealand for over 200 years, from the first visit of Captain James Cook and his English-speaking crew in 1769. He recorded in his diary some Maori words, such as pah (a fortified village) and on a later visit pounamu (greenstone or nephrite), that later became part of the vocabulary of all New Zealanders. However, a more realistic starting-point is 1840, when the Maori, inhabitants of the islands since the 9 c, ceded kawanatanga (governorship, interpreted by the British as sovereignty) to the British Crown in the Treaty of Waitangi. From that time, settlers from the British Isles began to arrive in increasing numbers, bringing their regional modes of speech with them.

The English language as used in New Zealand. English has been used in New Zealand for over 200 years, from the first visit of Captain James Cook and his English-speaking crew in 1769. He recorded in his diary some Maori words, such as pah (a fortified village) and on a later visit pounamu (greenstone or nephrite), that later became part of the vocabulary of all New Zealanders. However, a more realistic starting-point is 1840, when the Maori, inhabitants of the islands since the 9 c, ceded kawanatanga (governorship, interpreted by the British as sovereignty) to the British Crown in the Treaty of Waitangi. From that time, settlers from the British Isles began to arrive in increasing numbers, bringing their regional modes of speech with them.

NZE is non-rhotic, with the exception of the Southland burr, the use by some speakers in Southland Otago, South Island, of an /r/ in words like afford and heart. It is believed to derive from Sco. E, since Otago was a predominantly Scottish settlement. The norm of educated NZE is the Received Pronunciation of the BBC World Service. There are, however, relatively few RP-speakers in New Zealand, a larger proportion speaking what is now called Near -RP. Its consonants do not differ significantly from those in RP except that a wh/w distinction is often maintained in words like which/witch. In words like wharf, where no nearhomonym *warf exists, aspiration is less detectable.

NZE is non-rhotic, with the exception of the Southland burr, the use by some speakers in Southland Otago, South Island, of an /r/ in words like afford and heart. It is believed to derive from Sco. E, since Otago was a predominantly Scottish settlement. The norm of educated NZE is the Received Pronunciation of the BBC World Service. There are, however, relatively few RP-speakers in New Zealand, a larger proportion speaking what is now called Near -RP. Its consonants do not differ significantly from those in RP except that a wh/w distinction is often maintained in words like which/witch. In words like wharf, where no nearhomonym *warf exists, aspiration is less detectable.

Features of General New Zealand include: (1) Such words as ham, pen perceived by outsiders as 'hem', 'pin'. (2) The maintenance of RP 'ɑː' in castle, dance by contrast with General Australian /kæ sl, dæ ns/. (3) Schwa used in most unstressed syllables, including for both affect and effect, and for rubbish. (4) A tendency to pronounce grown, mown, thrown as disyllabic with a schwa: 'growen', 'mowen', 'throwen'. (5) A distinctive pronunciation for certain words: geyser rhyming with 'riser', oral with 'sorrel'; the first syllable of vitamin like 'high', as in Am. E and Sco. E; the Zea of Zealand pronounced with the vowel of kit.

Features of General New Zealand include: (1) Such words as ham, pen perceived by outsiders as 'hem', 'pin'. (2) The maintenance of RP 'ɑː' in castle, dance by contrast with General Australian /kæ sl, dæ ns/. (3) Schwa used in most unstressed syllables, including for both affect and effect, and for rubbish. (4) A tendency to pronounce grown, mown, thrown as disyllabic with a schwa: 'growen', 'mowen', 'throwen'. (5) A distinctive pronunciation for certain words: geyser rhyming with 'riser', oral with 'sorrel'; the first syllable of vitamin like 'high', as in Am. E and Sco. E; the Zea of Zealand pronounced with the vowel of kit.

In the absence of a comprehensive dictionary of NZE on historical principles, the number of distinctive words cannot be estimated with any certainty, but the total is likely to be less than a third of the 10, 000 claimed for Aus. E. This vocabulary falls into five classes: loanwords from Polynesian languages, words showing extension of or departure from the meanings of general English words, the elevation of regional Br. E words into standard currency, loanwords from Aus. E, and distinct regional word forms. This vocabulary is distributed through all walks of life, but particularly in the language of farming, food production, government, local administration, education, and informal usage.

In the absence of a comprehensive dictionary of NZE on historical principles, the number of distinctive words cannot be estimated with any certainty, but the total is likely to be less than a third of the 10, 000 claimed for Aus. E. This vocabulary falls into five classes: loanwords from Polynesian languages, words showing extension of or departure from the meanings of general English words, the elevation of regional Br. E words into standard currency, loanwords from Aus. E, and distinct regional word forms. This vocabulary is distributed through all walks of life, but particularly in the language of farming, food production, government, local administration, education, and informal usage.

Loanwords from Maori. In addition to names of flora and fauna, there is an increasing number of Maori loanwords for abstract concepts and tribal arrangements and customs: aue an interjection expressing astonishment, distress, etc. , haere mai a term of greeting, iwi a people, tribe, mana power, prestige, authority, manuwhiri a visitor, guest, mauri the life principle, rahui a sign warning against trespass, tupuna an ancestor. Standardization of British English dialect words. Br. E dialect words promoted to standard, all also Aus. E, include: barrack to shout or jeer (at players in a game, etc. ), bowyang a band or strip round a trouser -leg below the knee, to prevent trousers from dragging on the ground.

Loanwords from Maori. In addition to names of flora and fauna, there is an increasing number of Maori loanwords for abstract concepts and tribal arrangements and customs: aue an interjection expressing astonishment, distress, etc. , haere mai a term of greeting, iwi a people, tribe, mana power, prestige, authority, manuwhiri a visitor, guest, mauri the life principle, rahui a sign warning against trespass, tupuna an ancestor. Standardization of British English dialect words. Br. E dialect words promoted to standard, all also Aus. E, include: barrack to shout or jeer (at players in a game, etc. ), bowyang a band or strip round a trouser -leg below the knee, to prevent trousers from dragging on the ground.

Loanwords from Australian English. Words acquired from Aus. E include, from the preceding section, larrikin, Rajferty's rules, and: backblocks land in the remote interior, battler someone who struggles against the odds, dill a fool, simpleton, ocker a boor, offsider a companion, deputy, partner, shanghai a catapult. Distinct word forms. Regional coinages include compounds, fixed phrases, and diminutives: (adjective + noun) chilly bin a portable insulated container for keeping food and drink cool; (diminutive suffix -ie) boatie a boating enthusiast, postie a person delivering post (shared with Sco. E and Can. E) ; (diminutive suffix -o, -oh): arvo afternoon, bottle-oh a dealer in used bottles.

Loanwords from Australian English. Words acquired from Aus. E include, from the preceding section, larrikin, Rajferty's rules, and: backblocks land in the remote interior, battler someone who struggles against the odds, dill a fool, simpleton, ocker a boor, offsider a companion, deputy, partner, shanghai a catapult. Distinct word forms. Regional coinages include compounds, fixed phrases, and diminutives: (adjective + noun) chilly bin a portable insulated container for keeping food and drink cool; (diminutive suffix -ie) boatie a boating enthusiast, postie a person delivering post (shared with Sco. E and Can. E) ; (diminutive suffix -o, -oh): arvo afternoon, bottle-oh a dealer in used bottles.