Women: The Longest Revolution

Women: The Longest Revolution

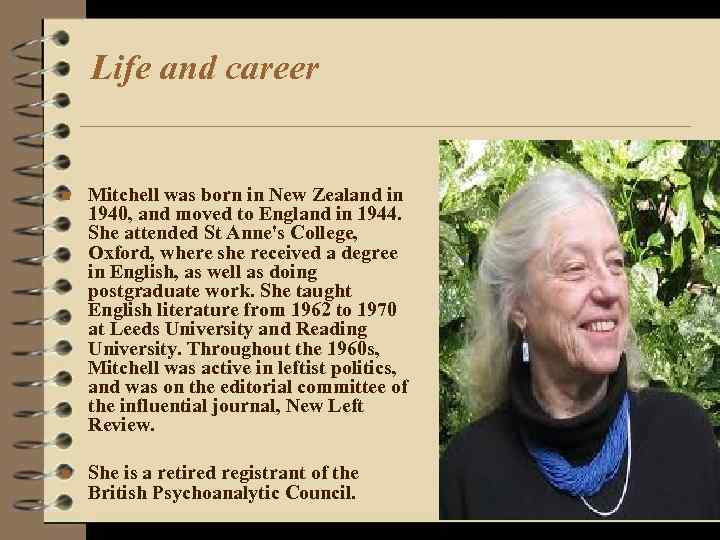

Life and career n Mitchell was born in New Zealand in 1940, and moved to England in 1944. She attended St Anne's College, Oxford, where she received a degree in English, as well as doing postgraduate work. She taught English literature from 1962 to 1970 at Leeds University and Reading University. Throughout the 1960 s, Mitchell was active in leftist politics, and was on the editorial committee of the influential journal, New Left Review. n She is a retired registrant of the British Psychoanalytic Council.

Life and career n Mitchell was born in New Zealand in 1940, and moved to England in 1944. She attended St Anne's College, Oxford, where she received a degree in English, as well as doing postgraduate work. She taught English literature from 1962 to 1970 at Leeds University and Reading University. Throughout the 1960 s, Mitchell was active in leftist politics, and was on the editorial committee of the influential journal, New Left Review. n She is a retired registrant of the British Psychoanalytic Council.

n Mitchell is best known for her book Psychoanalysis and Feminism: Freud, Reich, Laing and Women (1974), in which she tried to reconcile psychoanalysis and feminism at a time when many considered them incompatible.

n Mitchell is best known for her book Psychoanalysis and Feminism: Freud, Reich, Laing and Women (1974), in which she tried to reconcile psychoanalysis and feminism at a time when many considered them incompatible.

The Position of Women n Situation of women is different from that of any other oppressed social group: they are half of the human species. In some ways they are exploited and oppressed like, and along with, other exploited classes or oppressed groups – the working-class, Blacks, etc. . Until there is a revolution in production, the labour situation will prescribe women’s situation within the world of men. But women are offered a universe of their own: the family. Women are exploited at work, and relegated to the home: the two positions compound their oppression. Their subservience in production is obscured by their assumed dominance in their own world – the family. What is the family? And what are the actual functions that a woman fulfils within it? Like woman herself, the family appears as a natural object, but is actually a cultural creation. There is nothing inevitable about the form or role of the family, any more than there is about the character or role of women. It is the function of ideology to present these given social types as aspects of Nature itself. Both can be exalted, paradoxically, as ideals. The ‘true’ woman and the ‘true’ family are images of peace and plenty: in actuality they may both be sites of violence and despair

The Position of Women n Situation of women is different from that of any other oppressed social group: they are half of the human species. In some ways they are exploited and oppressed like, and along with, other exploited classes or oppressed groups – the working-class, Blacks, etc. . Until there is a revolution in production, the labour situation will prescribe women’s situation within the world of men. But women are offered a universe of their own: the family. Women are exploited at work, and relegated to the home: the two positions compound their oppression. Their subservience in production is obscured by their assumed dominance in their own world – the family. What is the family? And what are the actual functions that a woman fulfils within it? Like woman herself, the family appears as a natural object, but is actually a cultural creation. There is nothing inevitable about the form or role of the family, any more than there is about the character or role of women. It is the function of ideology to present these given social types as aspects of Nature itself. Both can be exalted, paradoxically, as ideals. The ‘true’ woman and the ‘true’ family are images of peace and plenty: in actuality they may both be sites of violence and despair

Production n The biological differentiation of the sexes into male and female and the division of labour that is based on this have seemed, throughout history, an interlocked necessity. Anatomically smaller and weaker, woman’s physiology and her psychobiological metabolism appear to render her a less useful member of a workforce. It is always stressed how, particularly in the early stages of social development, man’s physical superiority gave him the means of conquest over nature which was denied to women. Once woman was accorded the menial tasks involved in maintenance while man undertook conquest and creation, she became an aspect of the things preserved: private property and children.

Production n The biological differentiation of the sexes into male and female and the division of labour that is based on this have seemed, throughout history, an interlocked necessity. Anatomically smaller and weaker, woman’s physiology and her psychobiological metabolism appear to render her a less useful member of a workforce. It is always stressed how, particularly in the early stages of social development, man’s physical superiority gave him the means of conquest over nature which was denied to women. Once woman was accorded the menial tasks involved in maintenance while man undertook conquest and creation, she became an aspect of the things preserved: private property and children.

The Reproduction of Children n Women’s absence from the critical sector, of production historically, of course, has been caused not just by their assumed physical weakness in a context of coercion – but also by their role in reproduction. Maternity necessitates withdrawals from work, but this is not a decisive phenomenon. It is rather women’s role in reproduction which has become, in capitalist society at least, the spiritual ‘complement’ of men’s role in production. Bearing children, bringing them up, and maintaining the home – these form the core of woman’s natural vocation.

The Reproduction of Children n Women’s absence from the critical sector, of production historically, of course, has been caused not just by their assumed physical weakness in a context of coercion – but also by their role in reproduction. Maternity necessitates withdrawals from work, but this is not a decisive phenomenon. It is rather women’s role in reproduction which has become, in capitalist society at least, the spiritual ‘complement’ of men’s role in production. Bearing children, bringing them up, and maintaining the home – these form the core of woman’s natural vocation.

Sexuality and the Position of Women: Today n The situation today is defined by a new contradiction. Once formal conjugal equality (monogamy) is established, sexual freedom as such -which under polygamous conditions was usually a form of exploitation – becomes, conversely, a possible force for liberation. It then means, simply, the freedom of both sexes to transcend the limits of present sexual institutions. n Historically, then, there has been a dialectical movement in , which sexual expression was ‘sacrificed’ in an epoch of more-or-less puritan repression, which nevertheless produced a greater parity of sexual roles and in turn creates the pre-condition for a genuine sexual liberation, in the dual sense of equality and freedom – whose unity defines socialism.

Sexuality and the Position of Women: Today n The situation today is defined by a new contradiction. Once formal conjugal equality (monogamy) is established, sexual freedom as such -which under polygamous conditions was usually a form of exploitation – becomes, conversely, a possible force for liberation. It then means, simply, the freedom of both sexes to transcend the limits of present sexual institutions. n Historically, then, there has been a dialectical movement in , which sexual expression was ‘sacrificed’ in an epoch of more-or-less puritan repression, which nevertheless produced a greater parity of sexual roles and in turn creates the pre-condition for a genuine sexual liberation, in the dual sense of equality and freedom – whose unity defines socialism.

Infancy n For the mother, breast-feeding becomes a complement to the act of creation. It gives her a heightened sense of fulfilment and allows her to participate in a relationship as close to perfection as any that a woman can hope to achieve. . The simple fact of giving birth, however, does not of itself fulfil this need and longing. . Motherliness is a way of life. It enables a woman to express her total self with the tender feelings, the protective attitudes, the encompassing love of the motherly woman.

Infancy n For the mother, breast-feeding becomes a complement to the act of creation. It gives her a heightened sense of fulfilment and allows her to participate in a relationship as close to perfection as any that a woman can hope to achieve. . The simple fact of giving birth, however, does not of itself fulfil this need and longing. . Motherliness is a way of life. It enables a woman to express her total self with the tender feelings, the protective attitudes, the encompassing love of the motherly woman.

Family Patterns n This ideology corresponds in dislocated form to a real change in the pattern of the family. As the family has become smaller, each child has become more important; the actual act of reproduction occupies less and less time, and the socializing and nurturance process increase commensurately in significance. Contemporary society is obsessed by the physical, moral and sexual problems of childhood and adolescence. Ultimate responsibility for these is placed on the mother

Family Patterns n This ideology corresponds in dislocated form to a real change in the pattern of the family. As the family has become smaller, each child has become more important; the actual act of reproduction occupies less and less time, and the socializing and nurturance process increase commensurately in significance. Contemporary society is obsessed by the physical, moral and sexual problems of childhood and adolescence. Ultimate responsibility for these is placed on the mother

Conclusion n The State cannot exist without the family. Marriage is a positive value for the Socialist Soviet State only if the partners see in it a lifelong union. So-called free love is a bourgeois invention and has nothing in common with the principles of conduct of a Soviet citizen. Moreover, marriage receives its full value for the State only if there is progeny, and the consorts experience the highest happiness of parenthood.

Conclusion n The State cannot exist without the family. Marriage is a positive value for the Socialist Soviet State only if the partners see in it a lifelong union. So-called free love is a bourgeois invention and has nothing in common with the principles of conduct of a Soviet citizen. Moreover, marriage receives its full value for the State only if there is progeny, and the consorts experience the highest happiness of parenthood.