59281350d9d24fcb3cc744d354e6ef9b.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 15

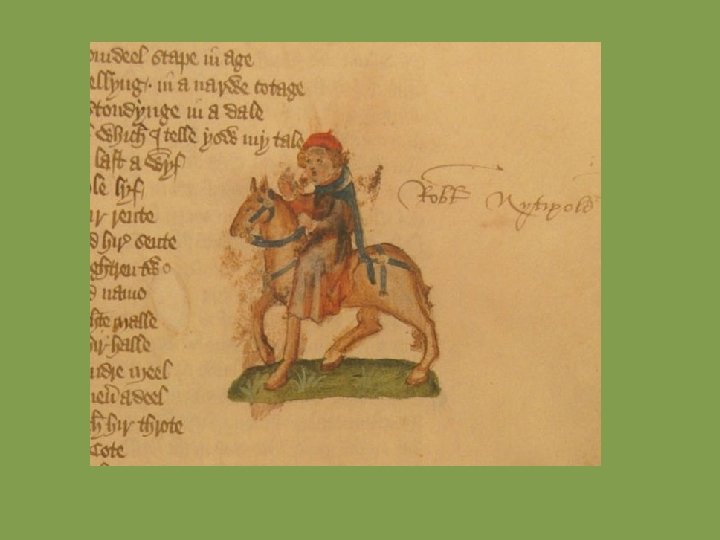

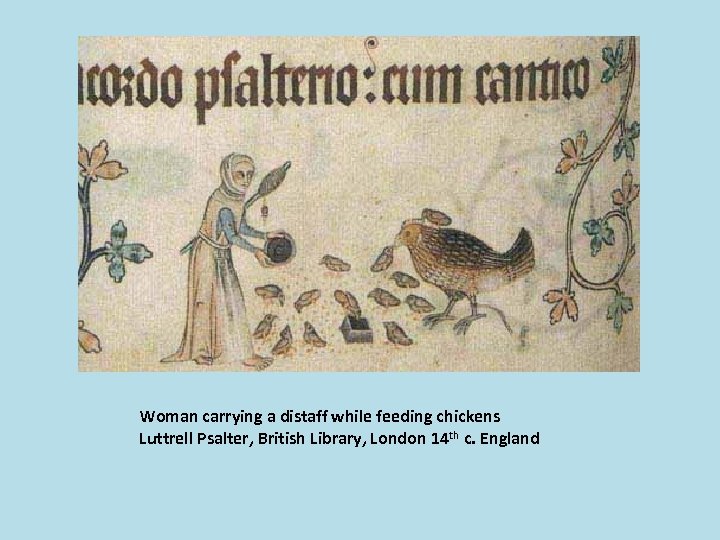

Woman carrying a distaff while feeding chickens Luttrell Psalter, British Library, London 14 th c. England

Woman carrying a distaff while feeding chickens Luttrell Psalter, British Library, London 14 th c. England

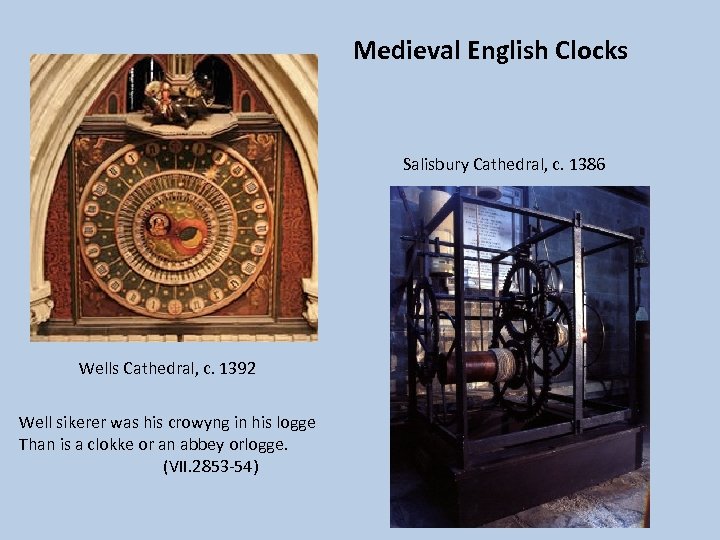

Medieval English Clocks Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1386 Wells Cathedral, c. 1392 Well sikerer was his crowyng in his logge Than is a clokke or an abbey orlogge. (VII. 2853 -54)

Medieval English Clocks Salisbury Cathedral, c. 1386 Wells Cathedral, c. 1392 Well sikerer was his crowyng in his logge Than is a clokke or an abbey orlogge. (VII. 2853 -54)

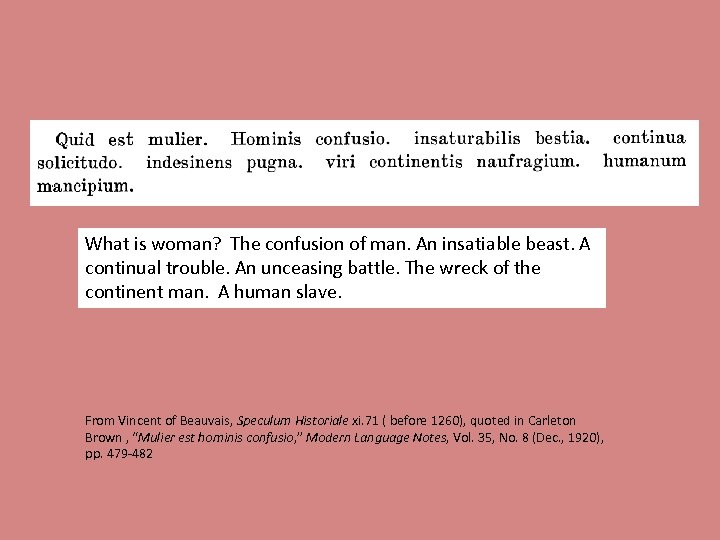

What is woman? The confusion of man. An insatiable beast. A continual trouble. An unceasing battle. The wreck of the continent man. A human slave. From Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum Historiale xi. 71 ( before 1260), quoted in Carleton Brown , “Mulier est hominis confusio, ” Modern Language Notes, Vol. 35, No. 8 (Dec. , 1920), pp. 479 -482

What is woman? The confusion of man. An insatiable beast. A continual trouble. An unceasing battle. The wreck of the continent man. A human slave. From Vincent of Beauvais, Speculum Historiale xi. 71 ( before 1260), quoted in Carleton Brown , “Mulier est hominis confusio, ” Modern Language Notes, Vol. 35, No. 8 (Dec. , 1920), pp. 479 -482

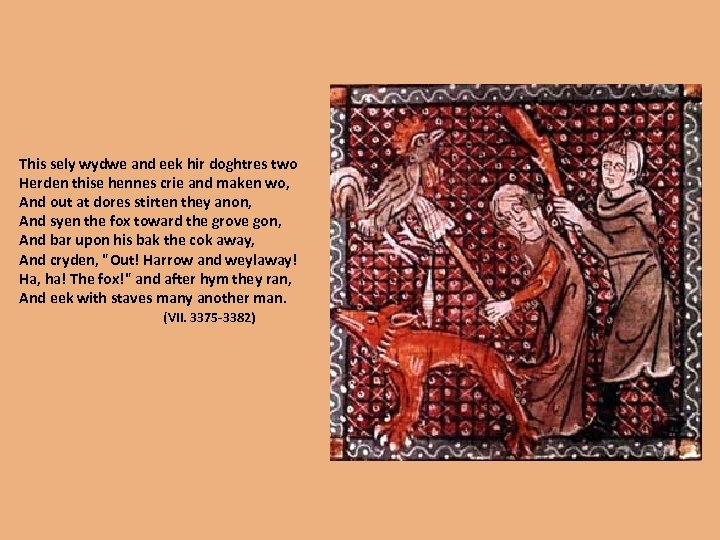

This sely wydwe and eek hir doghtres two Herden thise hennes crie and maken wo, And out at dores stirten they anon, And syen the fox toward the grove gon, And bar upon his bak the cok away, And cryden, "Out! Harrow and weylaway! Ha, ha! The fox!" and after hym they ran, And eek with staves many another man. (VII. 3375 -3382)

This sely wydwe and eek hir doghtres two Herden thise hennes crie and maken wo, And out at dores stirten they anon, And syen the fox toward the grove gon, And bar upon his bak the cok away, And cryden, "Out! Harrow and weylaway! Ha, ha! The fox!" and after hym they ran, And eek with staves many another man. (VII. 3375 -3382)

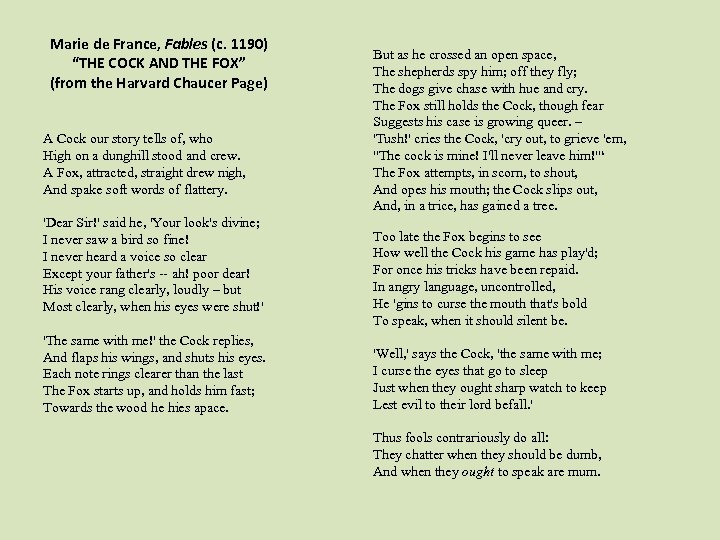

Marie de France, Fables (c. 1190) “THE COCK AND THE FOX” (from the Harvard Chaucer Page) A Cock our story tells of, who High on a dunghill stood and crew. A Fox, attracted, straight drew nigh, And spake soft words of flattery. 'Dear Sir!' said he, 'Your look's divine; I never saw a bird so fine! I never heard a voice so clear Except your father's -- ah! poor dear! His voice rang clearly, loudly – but Most clearly, when his eyes were shut!' 'The same with me!' the Cock replies, And flaps his wings, and shuts his eyes. Each note rings clearer than the last The Fox starts up, and holds him fast; Towards the wood he hies apace. But as he crossed an open space, The shepherds spy him; off they fly; The dogs give chase with hue and cry. The Fox still holds the Cock, though fear Suggests his case is growing queer. – 'Tush!' cries the Cock, 'cry out, to grieve 'em, "The cock is mine! I'll never leave him!"‘ The Fox attempts, in scorn, to shout, And opes his mouth; the Cock slips out, And, in a trice, has gained a tree. Too late the Fox begins to see How well the Cock his game has play'd; For once his tricks have been repaid. In angry language, uncontrolled, He 'gins to curse the mouth that's bold To speak, when it should silent be. 'Well, ' says the Cock, 'the same with me; I curse the eyes that go to sleep Just when they ought sharp watch to keep Lest evil to their lord befall. ' Thus fools contrariously do all: They chatter when they should be dumb, And when they ought to speak are mum.

Marie de France, Fables (c. 1190) “THE COCK AND THE FOX” (from the Harvard Chaucer Page) A Cock our story tells of, who High on a dunghill stood and crew. A Fox, attracted, straight drew nigh, And spake soft words of flattery. 'Dear Sir!' said he, 'Your look's divine; I never saw a bird so fine! I never heard a voice so clear Except your father's -- ah! poor dear! His voice rang clearly, loudly – but Most clearly, when his eyes were shut!' 'The same with me!' the Cock replies, And flaps his wings, and shuts his eyes. Each note rings clearer than the last The Fox starts up, and holds him fast; Towards the wood he hies apace. But as he crossed an open space, The shepherds spy him; off they fly; The dogs give chase with hue and cry. The Fox still holds the Cock, though fear Suggests his case is growing queer. – 'Tush!' cries the Cock, 'cry out, to grieve 'em, "The cock is mine! I'll never leave him!"‘ The Fox attempts, in scorn, to shout, And opes his mouth; the Cock slips out, And, in a trice, has gained a tree. Too late the Fox begins to see How well the Cock his game has play'd; For once his tricks have been repaid. In angry language, uncontrolled, He 'gins to curse the mouth that's bold To speak, when it should silent be. 'Well, ' says the Cock, 'the same with me; I curse the eyes that go to sleep Just when they ought sharp watch to keep Lest evil to their lord befall. ' Thus fools contrariously do all: They chatter when they should be dumb, And when they ought to speak are mum.

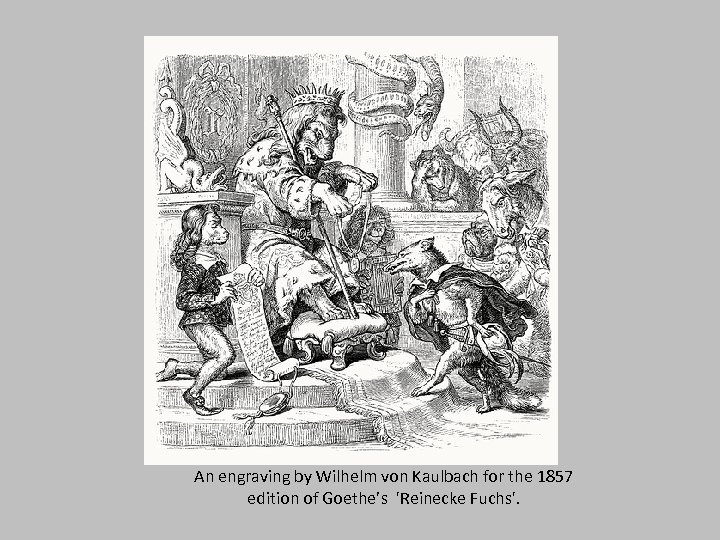

An engraving by Wilhelm von Kaulbach for the 1857 edition of Goethe’s 'Reinecke Fuchs'.

An engraving by Wilhelm von Kaulbach for the 1857 edition of Goethe’s 'Reinecke Fuchs'.

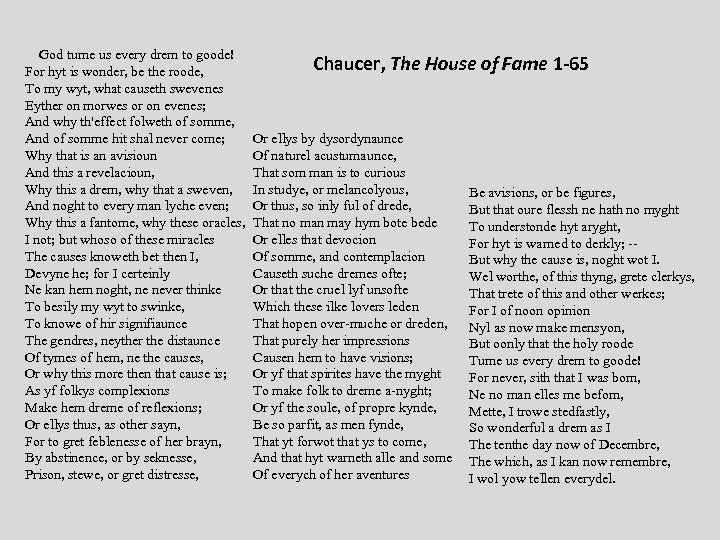

God turne us every drem to goode! Chaucer, The House of Fame 1 -65 For hyt is wonder, be the roode, To my wyt, what causeth swevenes Eyther on morwes or on evenes; And why th'effect folweth of somme, And of somme hit shal never come; Or ellys by dysordynaunce Why that is an avisioun Of naturel acustumaunce, And this a revelacioun, That som man is to curious Why this a drem, why that a sweven, In studye, or melancolyous, Be avisions, or be figures, And noght to every man lyche even; Or thus, so inly ful of drede, But that oure flessh ne hath no myght Why this a fantome, why these oracles, That no man may hym bote bede To understonde hyt aryght, Or elles that devocion I not; but whoso of these miracles For hyt is warned to derkly; -Of somme, and contemplacion The causes knoweth bet then I, But why the cause is, noght wot I. Causeth suche dremes ofte; Devyne he; for I certeinly Wel worthe, of this thyng, grete clerkys, Ne kan hem noght, ne never thinke Or that the cruel lyf unsofte That trete of this and other werkes; To besily my wyt to swinke, Which these ilke lovers leden For I of noon opinion That hopen over-muche or dreden, To knowe of hir signifiaunce Nyl as now make mensyon, That purely her impressions The gendres, neyther the distaunce But oonly that the holy roode Causen hem to have visions; Turne us every drem to goode! Of tymes of hem, ne the causes, Or why this more then that cause is; Or yf that spirites have the myght For never, sith that I was born, To make folk to dreme a-nyght; As yf folkys complexions Ne no man elles me beforn, Or yf the soule, of propre kynde, Make hem dreme of reflexions; Mette, I trowe stedfastly, Be so parfit, as men fynde, Or ellys thus, as other sayn, So wonderful a drem as I That yt forwot that ys to come, The tenthe day now of Decembre, For to gret feblenesse of her brayn, And that hyt warneth alle and some The which, as I kan now remembre, By abstinence, or by seknesse, Of everych of her aventures Prison, stewe, or gret distresse, I wol yow tellen everydel.

God turne us every drem to goode! Chaucer, The House of Fame 1 -65 For hyt is wonder, be the roode, To my wyt, what causeth swevenes Eyther on morwes or on evenes; And why th'effect folweth of somme, And of somme hit shal never come; Or ellys by dysordynaunce Why that is an avisioun Of naturel acustumaunce, And this a revelacioun, That som man is to curious Why this a drem, why that a sweven, In studye, or melancolyous, Be avisions, or be figures, And noght to every man lyche even; Or thus, so inly ful of drede, But that oure flessh ne hath no myght Why this a fantome, why these oracles, That no man may hym bote bede To understonde hyt aryght, Or elles that devocion I not; but whoso of these miracles For hyt is warned to derkly; -Of somme, and contemplacion The causes knoweth bet then I, But why the cause is, noght wot I. Causeth suche dremes ofte; Devyne he; for I certeinly Wel worthe, of this thyng, grete clerkys, Ne kan hem noght, ne never thinke Or that the cruel lyf unsofte That trete of this and other werkes; To besily my wyt to swinke, Which these ilke lovers leden For I of noon opinion That hopen over-muche or dreden, To knowe of hir signifiaunce Nyl as now make mensyon, That purely her impressions The gendres, neyther the distaunce But oonly that the holy roode Causen hem to have visions; Turne us every drem to goode! Of tymes of hem, ne the causes, Or why this more then that cause is; Or yf that spirites have the myght For never, sith that I was born, To make folk to dreme a-nyght; As yf folkys complexions Ne no man elles me beforn, Or yf the soule, of propre kynde, Make hem dreme of reflexions; Mette, I trowe stedfastly, Be so parfit, as men fynde, Or ellys thus, as other sayn, So wonderful a drem as I That yt forwot that ys to come, The tenthe day now of Decembre, For to gret feblenesse of her brayn, And that hyt warneth alle and some The which, as I kan now remembre, By abstinence, or by seknesse, Of everych of her aventures Prison, stewe, or gret distresse, I wol yow tellen everydel.

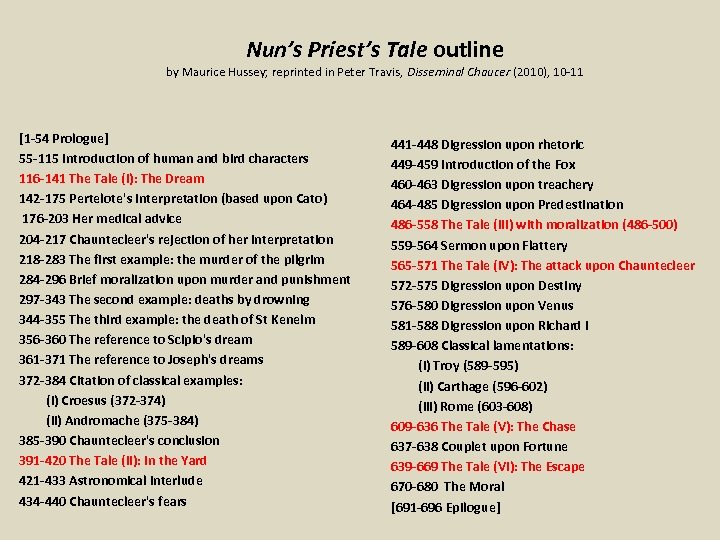

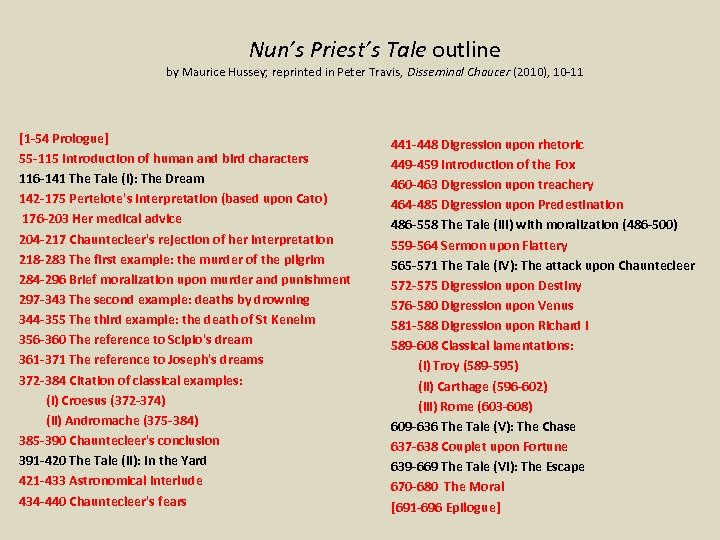

Nun’s Priest’s Tale outline by Maurice Hussey; reprinted in Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer (2010), 10 -11 [1 -54 Prologue] 55 -115 Introduction of human and bird characters 116 -141 The Tale (I): The Dream 142 -175 Pertelote's interpretation (based upon Cato) 176 -203 Her medical advice 204 -217 Chauntecleer's rejection of her interpretation 218 -283 The first example: the murder of the pilgrim 284 -296 Brief moralization upon murder and punishment 297 -343 The second example: deaths by drowning 344 -355 The third example: the death of St Kenelm 356 -360 The reference to Scipio's dream 361 -371 The reference to Joseph's dreams 372 -384 Citation of classical examples: (i) Croesus (372 -374) (ii) Andromache (375 -384) 385 -390 Chauntecleer's conclusion 391 -420 The Tale (II): In the Yard 421 -433 Astronomical interlude 434 -440 Chauntecleer's fears 441 -448 Digression upon rhetoric 449 -459 Introduction of the Fox 460 -463 Digression upon treachery 464 -485 Digression upon Predestination 486 -558 The Tale (III) with moralization (486 -500) 559 -564 Sermon upon Flattery 565 -571 The Tale (IV): The attack upon Chauntecleer 572 -575 Digression upon Destiny 576 -580 Digression upon Venus 581 -588 Digression upon Richard I 589 -608 Classical lamentations: (i) Troy (589 -595) (ii) Carthage (596 -602) (iii) Rome (603 -608) 609 -636 The Tale (V): The Chase 637 -638 Couplet upon Fortune 639 -669 The Tale (VI): The Escape 670 -680 The Moral [691 -696 Epilogue]

Nun’s Priest’s Tale outline by Maurice Hussey; reprinted in Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer (2010), 10 -11 [1 -54 Prologue] 55 -115 Introduction of human and bird characters 116 -141 The Tale (I): The Dream 142 -175 Pertelote's interpretation (based upon Cato) 176 -203 Her medical advice 204 -217 Chauntecleer's rejection of her interpretation 218 -283 The first example: the murder of the pilgrim 284 -296 Brief moralization upon murder and punishment 297 -343 The second example: deaths by drowning 344 -355 The third example: the death of St Kenelm 356 -360 The reference to Scipio's dream 361 -371 The reference to Joseph's dreams 372 -384 Citation of classical examples: (i) Croesus (372 -374) (ii) Andromache (375 -384) 385 -390 Chauntecleer's conclusion 391 -420 The Tale (II): In the Yard 421 -433 Astronomical interlude 434 -440 Chauntecleer's fears 441 -448 Digression upon rhetoric 449 -459 Introduction of the Fox 460 -463 Digression upon treachery 464 -485 Digression upon Predestination 486 -558 The Tale (III) with moralization (486 -500) 559 -564 Sermon upon Flattery 565 -571 The Tale (IV): The attack upon Chauntecleer 572 -575 Digression upon Destiny 576 -580 Digression upon Venus 581 -588 Digression upon Richard I 589 -608 Classical lamentations: (i) Troy (589 -595) (ii) Carthage (596 -602) (iii) Rome (603 -608) 609 -636 The Tale (V): The Chase 637 -638 Couplet upon Fortune 639 -669 The Tale (VI): The Escape 670 -680 The Moral [691 -696 Epilogue]

Nun’s Priest’s Tale outline by Maurice Hussey; reprinted in Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer (2010), 10 -11 [1 -54 Prologue] 55 -115 Introduction of human and bird characters 116 -141 The Tale (I): The Dream 142 -175 Pertelote's interpretation (based upon Cato) 176 -203 Her medical advice 204 -217 Chauntecleer's rejection of her interpretation 218 -283 The first example: the murder of the pilgrim 284 -296 Brief moralization upon murder and punishment 297 -343 The second example: deaths by drowning 344 -355 The third example: the death of St Kenelm 356 -360 The reference to Scipio's dream 361 -371 The reference to Joseph's dreams 372 -384 Citation of classical examples: (i) Croesus (372 -374) (ii) Andromache (375 -384) 385 -390 Chauntecleer's conclusion 391 -420 The Tale (II): In the Yard 421 -433 Astronomical interlude 434 -440 Chauntecleer's fears 441 -448 Digression upon rhetoric 449 -459 Introduction of the Fox 460 -463 Digression upon treachery 464 -485 Digression upon Predestination 486 -558 The Tale (III) with moralization (486 -500) 559 -564 Sermon upon Flattery 565 -571 The Tale (IV): The attack upon Chauntecleer 572 -575 Digression upon Destiny 576 -580 Digression upon Venus 581 -588 Digression upon Richard I 589 -608 Classical lamentations: (i) Troy (589 -595) (ii) Carthage (596 -602) (iii) Rome (603 -608) 609 -636 The Tale (V): The Chase 637 -638 Couplet upon Fortune 639 -669 The Tale (VI): The Escape 670 -680 The Moral [691 -696 Epilogue]

Nun’s Priest’s Tale outline by Maurice Hussey; reprinted in Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer (2010), 10 -11 [1 -54 Prologue] 55 -115 Introduction of human and bird characters 116 -141 The Tale (I): The Dream 142 -175 Pertelote's interpretation (based upon Cato) 176 -203 Her medical advice 204 -217 Chauntecleer's rejection of her interpretation 218 -283 The first example: the murder of the pilgrim 284 -296 Brief moralization upon murder and punishment 297 -343 The second example: deaths by drowning 344 -355 The third example: the death of St Kenelm 356 -360 The reference to Scipio's dream 361 -371 The reference to Joseph's dreams 372 -384 Citation of classical examples: (i) Croesus (372 -374) (ii) Andromache (375 -384) 385 -390 Chauntecleer's conclusion 391 -420 The Tale (II): In the Yard 421 -433 Astronomical interlude 434 -440 Chauntecleer's fears 441 -448 Digression upon rhetoric 449 -459 Introduction of the Fox 460 -463 Digression upon treachery 464 -485 Digression upon Predestination 486 -558 The Tale (III) with moralization (486 -500) 559 -564 Sermon upon Flattery 565 -571 The Tale (IV): The attack upon Chauntecleer 572 -575 Digression upon Destiny 576 -580 Digression upon Venus 581 -588 Digression upon Richard I 589 -608 Classical lamentations: (i) Troy (589 -595) (ii) Carthage (596 -602) (iii) Rome (603 -608) 609 -636 The Tale (V): The Chase 637 -638 Couplet upon Fortune 639 -669 The Tale (VI): The Escape 670 -680 The Moral [691 -696 Epilogue]

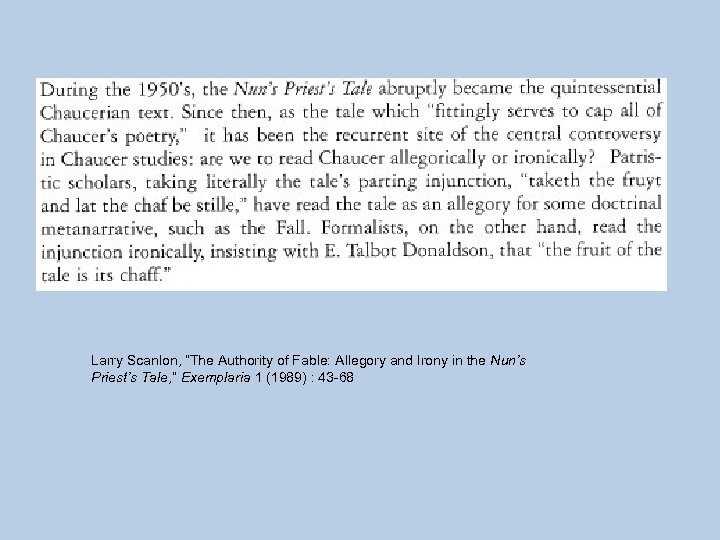

Larry Scanlon, “The Authority of Fable: Allegory and Irony in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, ” Exemplaria 1 (1989) : 43 -68

Larry Scanlon, “The Authority of Fable: Allegory and Irony in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, ” Exemplaria 1 (1989) : 43 -68

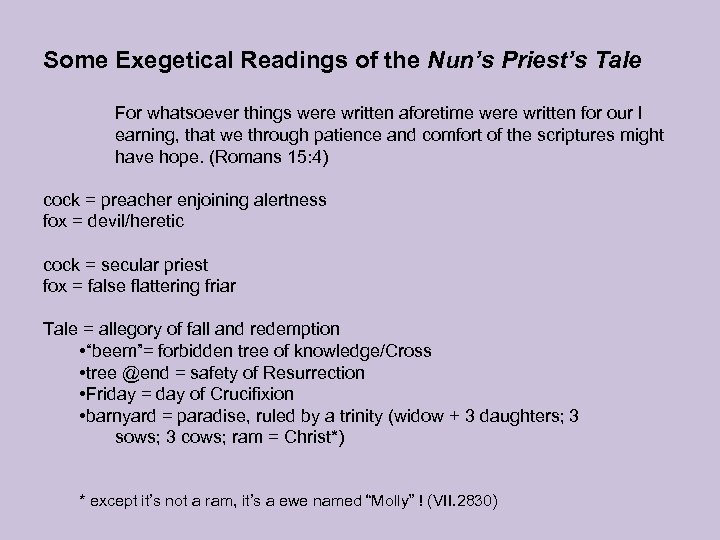

Some Exegetical Readings of the Nun’s Priest’s Tale For whatsoever things were written aforetime were written for our l earning, that we through patience and comfort of the scriptures might have hope. (Romans 15: 4) cock = preacher enjoining alertness fox = devil/heretic cock = secular priest fox = false flattering friar Tale = allegory of fall and redemption • “beem”= forbidden tree of knowledge/Cross • tree @end = safety of Resurrection • Friday = day of Crucifixion • barnyard = paradise, ruled by a trinity (widow + 3 daughters; 3 sows; 3 cows; ram = Christ*) * except it’s not a ram, it’s a ewe named “Molly” ! (VII. 2830)

Some Exegetical Readings of the Nun’s Priest’s Tale For whatsoever things were written aforetime were written for our l earning, that we through patience and comfort of the scriptures might have hope. (Romans 15: 4) cock = preacher enjoining alertness fox = devil/heretic cock = secular priest fox = false flattering friar Tale = allegory of fall and redemption • “beem”= forbidden tree of knowledge/Cross • tree @end = safety of Resurrection • Friday = day of Crucifixion • barnyard = paradise, ruled by a trinity (widow + 3 daughters; 3 sows; 3 cows; ram = Christ*) * except it’s not a ram, it’s a ewe named “Molly” ! (VII. 2830)

The Nun’s Priest’s Tale—the ironic approach There is allusion to serious matters here, and indeed the tale is shot through with such allusion, which has provided a temptation that modern interpreters, unwilling to regard laughter as an adequate reward for the effort expended in reading the tale, have found it difficult to resist, despite the wise warnings issued by Muscatine: The tale will betray with laughter any too-solemn scrutiny of its naked argument; if it is true that Chauntecleer and Pertelote are rounded characters, it is also true that they are chickens…Unlike fable, the Nun’s Priest’s Tale does not so much make true and solemn assertions about life as it tests truths and tries out solemnities. If you are not careful, it will try out your solemnity too. (1957, p. 242) *** *** The manner in which the Nun’s Priest’s Tale recoils upon all systematic attempts at interpretation is not a sign that more efforts should be made to find one that works. Its machinery is designed to defy such attempts: that is the point of the tale. Language and rhetoric and learning are noble arts, but they are constantly shown in the tale being used, by expert practitioners, to conceal the world from themselves, and themselves from themselves. They become, not means to understanding, but a series of reflecting mirrors in which we can be satisfied we shall see only those things that preserve our high opinion of ourselves…. The laughter has an edge, but it is salutary, not satirical: it implicates the reader, and the critic. Derek Pearsall, The Canterbury Tales (1985), 235, 238

The Nun’s Priest’s Tale—the ironic approach There is allusion to serious matters here, and indeed the tale is shot through with such allusion, which has provided a temptation that modern interpreters, unwilling to regard laughter as an adequate reward for the effort expended in reading the tale, have found it difficult to resist, despite the wise warnings issued by Muscatine: The tale will betray with laughter any too-solemn scrutiny of its naked argument; if it is true that Chauntecleer and Pertelote are rounded characters, it is also true that they are chickens…Unlike fable, the Nun’s Priest’s Tale does not so much make true and solemn assertions about life as it tests truths and tries out solemnities. If you are not careful, it will try out your solemnity too. (1957, p. 242) *** *** The manner in which the Nun’s Priest’s Tale recoils upon all systematic attempts at interpretation is not a sign that more efforts should be made to find one that works. Its machinery is designed to defy such attempts: that is the point of the tale. Language and rhetoric and learning are noble arts, but they are constantly shown in the tale being used, by expert practitioners, to conceal the world from themselves, and themselves from themselves. They become, not means to understanding, but a series of reflecting mirrors in which we can be satisfied we shall see only those things that preserve our high opinion of ourselves…. The laughter has an edge, but it is salutary, not satirical: it implicates the reader, and the critic. Derek Pearsall, The Canterbury Tales (1985), 235, 238

Larry Scanlon, “The Authority of Fable: Allegory and Irony in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, ” Exemplaria 1 (1989) : 43 -68

Larry Scanlon, “The Authority of Fable: Allegory and Irony in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, ” Exemplaria 1 (1989) : 43 -68

For Chaucer’s literate audience, each of these characteristics—beast fable, debate, Catonian assertion, Latin translation, and a string of variously told narrative proofs—would have been poignantly evocative, triggering a collage of bittersweet personal memories from their early years of grammar school linguistic and literary training. …I want to emphasize that Chaucer’s parodic evocations of the classroom are not designed to satirize the foundations of the medieval liberal arts curriculum for any perceived imperfections in its pedagogical principles or literary precepts. Rather, Chaucer takes his readers back to basics in order that they might reexperience, now at a more sophisticated level, both the profundities and baffling complexities of literature. Thus, by casting his ars poetica as an Aesopian beast fable, Chaucer is reopening that interlinear space—invoking his readers’ memories of a time when they were most intimately engaged in the craft of literary analysis, imitation, and production. In the very same gesture, Chaucer zeroes in on the fundamentals of literature itself. Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer: Rereading The Nun’s Priest’s Tale (University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), pp. 52 -53, 55.

For Chaucer’s literate audience, each of these characteristics—beast fable, debate, Catonian assertion, Latin translation, and a string of variously told narrative proofs—would have been poignantly evocative, triggering a collage of bittersweet personal memories from their early years of grammar school linguistic and literary training. …I want to emphasize that Chaucer’s parodic evocations of the classroom are not designed to satirize the foundations of the medieval liberal arts curriculum for any perceived imperfections in its pedagogical principles or literary precepts. Rather, Chaucer takes his readers back to basics in order that they might reexperience, now at a more sophisticated level, both the profundities and baffling complexities of literature. Thus, by casting his ars poetica as an Aesopian beast fable, Chaucer is reopening that interlinear space—invoking his readers’ memories of a time when they were most intimately engaged in the craft of literary analysis, imitation, and production. In the very same gesture, Chaucer zeroes in on the fundamentals of literature itself. Peter Travis, Disseminal Chaucer: Rereading The Nun’s Priest’s Tale (University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), pp. 52 -53, 55.