19c44480cf43c6c43aaf119fda4edf8e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 56

Wisconsin Rural School Teachers 1880 - 1950 UW-Eau Claire Center of Excellence for Faculty and Undergraduate Student Research Collaboration

Wisconsin Rural School Teachers 1880 - 1950 UW-Eau Claire Center of Excellence for Faculty and Undergraduate Student Research Collaboration

Attributes of rural Wisconsin teachers The role, influence and impact of rural teachers Selection and supervision of rural Wisconsin teachers Typical day in the One Room School House Highlight three Wisconsin rural teachers Dr. Maureen D. Mack Sunshine Mc Faul & Annelies Slack

Attributes of rural Wisconsin teachers The role, influence and impact of rural teachers Selection and supervision of rural Wisconsin teachers Typical day in the One Room School House Highlight three Wisconsin rural teachers Dr. Maureen D. Mack Sunshine Mc Faul & Annelies Slack

Rural Teachers Were Born Winter 1870: 2 small boys, 5 and 6 years old began school in a one-room schoolhouse in Nebraska. They had no preparation and did not know their ABC’s. Two months later, the county superintendent heard them read every word from Hillard’s First Reader without a mistake. In his report the county superintendent wrote: They were bright little fellows, but it was not all in the children; there was power in the teacher…There is more than one kind of education necessary to make a good teacher. They are born, not altogether made.

Rural Teachers Were Born Winter 1870: 2 small boys, 5 and 6 years old began school in a one-room schoolhouse in Nebraska. They had no preparation and did not know their ABC’s. Two months later, the county superintendent heard them read every word from Hillard’s First Reader without a mistake. In his report the county superintendent wrote: They were bright little fellows, but it was not all in the children; there was power in the teacher…There is more than one kind of education necessary to make a good teacher. They are born, not altogether made.

From Male Schoolmasters to Young Women Schoolteachers Late 1800’s - 1900’s enormous amount of time and energy devoted to teaching teachers to teach. Once women became the dominate rural school teachers, county superintendents from Ohio to Nebraska and from Minnesota to Missouri, believed that country school teachers were inefficient, ineffectual, incompetent, and in desperate need of training.

From Male Schoolmasters to Young Women Schoolteachers Late 1800’s - 1900’s enormous amount of time and energy devoted to teaching teachers to teach. Once women became the dominate rural school teachers, county superintendents from Ohio to Nebraska and from Minnesota to Missouri, believed that country school teachers were inefficient, ineffectual, incompetent, and in desperate need of training.

The Civil War …was the initial reason women replaced men as schoolteachers. Two major reasons women continued on as teachers. Men had choices between a variety of different occupations (women didn’t). As more women entered into teaching, men proclaimed it “women’s work” and began to shun the profession. Women were paid same job. significantly less to do the When it became obvious that women teachers could always be hired for less money, educators asserted that women were better teachers than men, and women were better suited to teaching.

The Civil War …was the initial reason women replaced men as schoolteachers. Two major reasons women continued on as teachers. Men had choices between a variety of different occupations (women didn’t). As more women entered into teaching, men proclaimed it “women’s work” and began to shun the profession. Women were paid same job. significantly less to do the When it became obvious that women teachers could always be hired for less money, educators asserted that women were better teachers than men, and women were better suited to teaching.

Exception to the Rule Wisconsin always preferred women schoolteachers. Was it difficult for her to get through the snow in the winter? Then, the thing to do was to find one that is robust…Let her dress warmly, wear good stout boots, and she would do very well. She was not merely man’s equal as a teacher, said some, but actually his superior. What is the true object of teaching? Is it not inciting to right action by culture of right principles implanted in the mind and heart? Who is more fitted to do this great work aright than women? (Jorgenson, Lloyd P. “The Founding of Public Education in Wisconsin. ” Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 1956. ) In 1872 an educator wrote: Woman is more sprightly and vivacious than men; has larger buoyancy and animal spirits, is generally less clumsy, is mentally more agile and versatile then the male, knows how to conquer by yielding. But women schoolteachers had their faults: their voice defective, their carriage faulty, and they lacked intellectual independence.

Exception to the Rule Wisconsin always preferred women schoolteachers. Was it difficult for her to get through the snow in the winter? Then, the thing to do was to find one that is robust…Let her dress warmly, wear good stout boots, and she would do very well. She was not merely man’s equal as a teacher, said some, but actually his superior. What is the true object of teaching? Is it not inciting to right action by culture of right principles implanted in the mind and heart? Who is more fitted to do this great work aright than women? (Jorgenson, Lloyd P. “The Founding of Public Education in Wisconsin. ” Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 1956. ) In 1872 an educator wrote: Woman is more sprightly and vivacious than men; has larger buoyancy and animal spirits, is generally less clumsy, is mentally more agile and versatile then the male, knows how to conquer by yielding. But women schoolteachers had their faults: their voice defective, their carriage faulty, and they lacked intellectual independence.

Wisconsin Rural Teachers Were Women n Average young female schoolteacher in the Midwest (Wisconsin) was likely to be a farm girl who had grown up in a large family and had experience with milking cows and plowing fields. She was no more than 16. Later, the average of the teachers increased, to around 20 years old. n She rose early, and took care of herself and others. Her knowledge of school was limited to what she learned in her school. She might have read through the sixth grade reader, knew how to diagram a sentence, how to spell, and learned the names and capitals of the states. She passed the third grade certificate which allowed her to teach for six months of a year without reexaminations.

Wisconsin Rural Teachers Were Women n Average young female schoolteacher in the Midwest (Wisconsin) was likely to be a farm girl who had grown up in a large family and had experience with milking cows and plowing fields. She was no more than 16. Later, the average of the teachers increased, to around 20 years old. n She rose early, and took care of herself and others. Her knowledge of school was limited to what she learned in her school. She might have read through the sixth grade reader, knew how to diagram a sentence, how to spell, and learned the names and capitals of the states. She passed the third grade certificate which allowed her to teach for six months of a year without reexaminations.

Competence of Young Women Were the female rural schoolteachers as incompetent and ignorant as the male educators made them out to be? In 1889 a school inspector in Michigan wrote: We hear much in these days about the poor quality of instruction in the rural district schools; in fact, there is a tendency to belittle the important work they do. I think that much of this opinion arises from lack of knowledge of the quality of work that these schools actual accomplishes…I am convinced from long observation of the work of both graded and rural schools that the average rural school teacher is as efficient as the average graded school teachers.

Competence of Young Women Were the female rural schoolteachers as incompetent and ignorant as the male educators made them out to be? In 1889 a school inspector in Michigan wrote: We hear much in these days about the poor quality of instruction in the rural district schools; in fact, there is a tendency to belittle the important work they do. I think that much of this opinion arises from lack of knowledge of the quality of work that these schools actual accomplishes…I am convinced from long observation of the work of both graded and rural schools that the average rural school teacher is as efficient as the average graded school teachers.

Country School Teachers Mobility Local policy did not favor retaining teachers for more than one or two years n Sometimes a teacher was not rehired simply because the farmers’ wives found her unsatisfactory. n One teacher in Iowa lost her job because, unknown to her, she had defeated a man who wanted to be Sunday school superintendent.

Country School Teachers Mobility Local policy did not favor retaining teachers for more than one or two years n Sometimes a teacher was not rehired simply because the farmers’ wives found her unsatisfactory. n One teacher in Iowa lost her job because, unknown to her, she had defeated a man who wanted to be Sunday school superintendent.

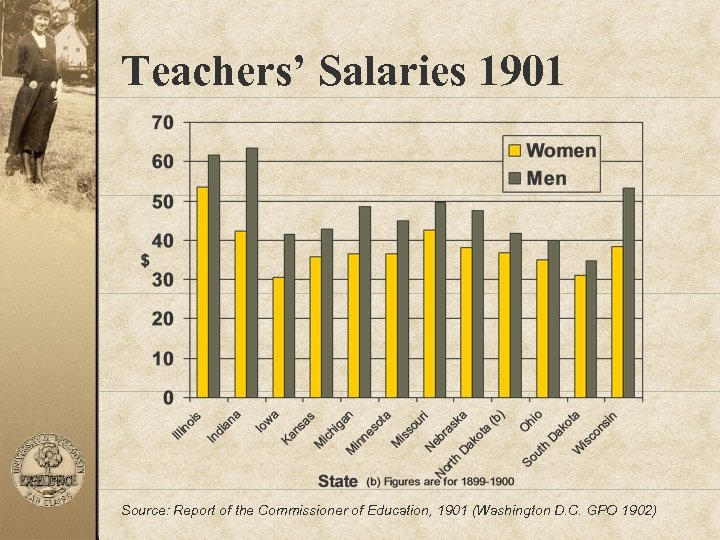

Teachers’ Salaries 1901 Source: Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1901 (Washington D. C. GPO 1902)

Teachers’ Salaries 1901 Source: Report of the Commissioner of Education, 1901 (Washington D. C. GPO 1902)

County Teacher Institutes n 1870’s: States agreed that teacher institutes should be n n held in each county. County teacher institutes were rural institutions, and were as unpretentious as the farmers and more acceptable to them than the normal schools were. County institutes were inexpensive--- the poorest farmer’s daughter could attend. Financed by a one dollar tax on teaching certificates, a one dollar entrance fee, and sometimes by a modest state government stipend and were locally controlled. This irritated the professional educators and state superintendents of public instruction. Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n 1870’s: States agreed that teacher institutes should be n n held in each county. County teacher institutes were rural institutions, and were as unpretentious as the farmers and more acceptable to them than the normal schools were. County institutes were inexpensive--- the poorest farmer’s daughter could attend. Financed by a one dollar tax on teaching certificates, a one dollar entrance fee, and sometimes by a modest state government stipend and were locally controlled. This irritated the professional educators and state superintendents of public instruction. Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n The conductors were not professionals in education but were appointed for political reasons. They were often installed to give opportunities to individuals to earn or save money—they were not professional educators. n In the early 1880’s the superintendent of Iowa invited Herbert Quick, a country schoolteacher, and Carrie Lane, the superintendent of schools in Mason City, to teach at the upcoming county institute. Carrie Lane— later known as Carrie Chapman Catt, leader of the women’s suffrage movement—refused because, among other things, the superintendent had invited country schoolteachers to teach at the institute! Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n The conductors were not professionals in education but were appointed for political reasons. They were often installed to give opportunities to individuals to earn or save money—they were not professional educators. n In the early 1880’s the superintendent of Iowa invited Herbert Quick, a country schoolteacher, and Carrie Lane, the superintendent of schools in Mason City, to teach at the upcoming county institute. Carrie Lane— later known as Carrie Chapman Catt, leader of the women’s suffrage movement—refused because, among other things, the superintendent had invited country schoolteachers to teach at the institute! Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n Teacher institutes stirred a flurry of excitement in the slow- paced Midwestern rural life in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. n The institutes weren’t all work. n Teachers reflected the dominant rural opinion: drills in arithmetic, grammar, reading, spelling, and human anatomy. n Instruction time was devoted to: Object lesson method n Teaching word and phonic methods n How to hold class recitations n Keeping school records n How to manage one-room schools n Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n Teacher institutes stirred a flurry of excitement in the slow- paced Midwestern rural life in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. n The institutes weren’t all work. n Teachers reflected the dominant rural opinion: drills in arithmetic, grammar, reading, spelling, and human anatomy. n Instruction time was devoted to: Object lesson method n Teaching word and phonic methods n How to hold class recitations n Keeping school records n How to manage one-room schools n Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n County institutes made an immense contribution to the education of Midwest country children. Rural people were given a chance to continue their educations beyond the country school with little expense. They sent out to the little white schoolhouses young people who were able, as a rule, to teach effectively and to lift some three generations of rural Americans to a standard of literacy unequaled by any other regions in the nation. Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

County Teacher Institutes n County institutes made an immense contribution to the education of Midwest country children. Rural people were given a chance to continue their educations beyond the country school with little expense. They sent out to the little white schoolhouses young people who were able, as a rule, to teach effectively and to lift some three generations of rural Americans to a standard of literacy unequaled by any other regions in the nation. Fuller, The Old Country School. 1982.

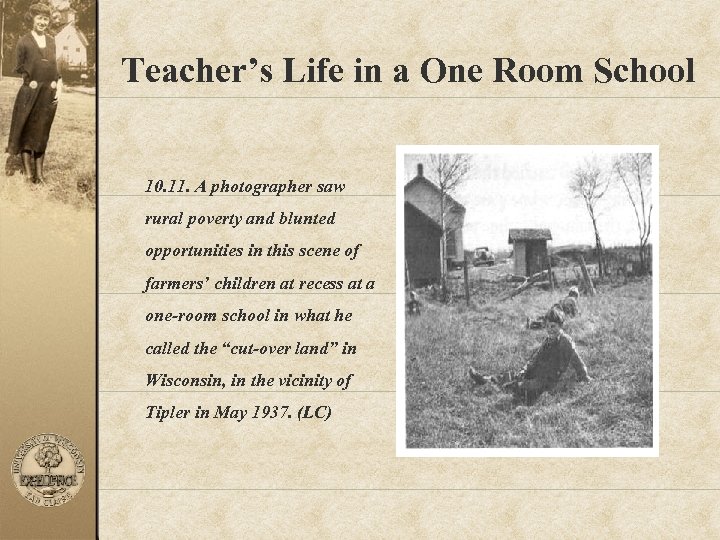

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School 10. 11. A photographer saw rural poverty and blunted opportunities in this scene of farmers’ children at recess at a one-room school in what he called the “cut-over land” in Wisconsin, in the vicinity of Tipler in May 1937. (LC)

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School 10. 11. A photographer saw rural poverty and blunted opportunities in this scene of farmers’ children at recess at a one-room school in what he called the “cut-over land” in Wisconsin, in the vicinity of Tipler in May 1937. (LC)

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School n April, 1872: Mary Bradford and her parents drove west from Kenosha Wisconsin in the family two-seated buggy on their way to a farm that sat near the boundary line between Kenosha and Racine counties. Mary was to board at that farm. Her parents visited with the farm family and bid a hasty farewell. She shared a bed with the farmer’s daughter and, consequently, her hair became infested with lice. n While boarding had its limitations, it worked to the advantage of the young female schoolteacher. She learned quickly what she must and must not do to fit into the family structure of the local community. n Mary signed a three month contract for $25 a month.

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School n April, 1872: Mary Bradford and her parents drove west from Kenosha Wisconsin in the family two-seated buggy on their way to a farm that sat near the boundary line between Kenosha and Racine counties. Mary was to board at that farm. Her parents visited with the farm family and bid a hasty farewell. She shared a bed with the farmer’s daughter and, consequently, her hair became infested with lice. n While boarding had its limitations, it worked to the advantage of the young female schoolteacher. She learned quickly what she must and must not do to fit into the family structure of the local community. n Mary signed a three month contract for $25 a month.

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School n Early on her first morning of school, Mary took the school bell, the key, a watch, and a tin lunch pail and walked the half mile from the farm to her schoolhouse. She arrived to discover a schoolhouse in shambles. There was a broken doorstep and ashes and papers were strewn about the mud-clod filled floor. Mary tidied up and rang the bell to bring her students to their seats. Among her 16 students of varying ages was a 19 year old girl who wanted to study algebra—a subject Mary had just begun to study before leaving her own high school studies. n Mary Bradford’s experiences were not unique. Thousands of young rural girls left their homes to teach in a country school. Loneliness, homesickness, uneasiness, worry over place to board, and even cleaning the schoolhouse the first day were the common experiences of teachers who taught in a Wisconsin rural school.

Teacher’s Life in a One Room School n Early on her first morning of school, Mary took the school bell, the key, a watch, and a tin lunch pail and walked the half mile from the farm to her schoolhouse. She arrived to discover a schoolhouse in shambles. There was a broken doorstep and ashes and papers were strewn about the mud-clod filled floor. Mary tidied up and rang the bell to bring her students to their seats. Among her 16 students of varying ages was a 19 year old girl who wanted to study algebra—a subject Mary had just begun to study before leaving her own high school studies. n Mary Bradford’s experiences were not unique. Thousands of young rural girls left their homes to teach in a country school. Loneliness, homesickness, uneasiness, worry over place to board, and even cleaning the schoolhouse the first day were the common experiences of teachers who taught in a Wisconsin rural school.

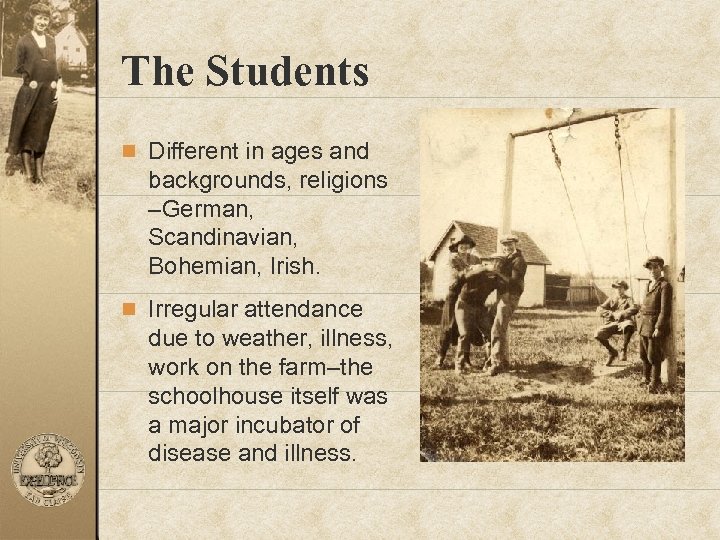

The Students n Different in ages and backgrounds, religions –German, Scandinavian, Bohemian, Irish. n Irregular attendance due to weather, illness, work on the farm–the schoolhouse itself was a major incubator of disease and illness.

The Students n Different in ages and backgrounds, religions –German, Scandinavian, Bohemian, Irish. n Irregular attendance due to weather, illness, work on the farm–the schoolhouse itself was a major incubator of disease and illness.

One Room Teaching Methods n Success due to her. n No visual aids and up until the 1890’s; had no clock on the wall. n Many rural teachers planted trees, shrubs, and flower gardens in the school yard. n Oftentimes the school had no well. n Yet in these unlikely places the illiteracy rate was reduced from 9. 3% to 4. 2% between 1870 and 1900 in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri. No other area of the nation had done as well, even given the massive influx of immigrants.

One Room Teaching Methods n Success due to her. n No visual aids and up until the 1890’s; had no clock on the wall. n Many rural teachers planted trees, shrubs, and flower gardens in the school yard. n Oftentimes the school had no well. n Yet in these unlikely places the illiteracy rate was reduced from 9. 3% to 4. 2% between 1870 and 1900 in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri. No other area of the nation had done as well, even given the massive influx of immigrants.

One Room Teaching Methods n Cleanliness was stressed in the schools. n Protestant values. n English was the forced language. n She met with others doing the same job in various corners of their counties The desire to train the faculties of the mind was theory behind recitations and drills.

One Room Teaching Methods n Cleanliness was stressed in the schools. n Protestant values. n English was the forced language. n She met with others doing the same job in various corners of their counties The desire to train the faculties of the mind was theory behind recitations and drills.

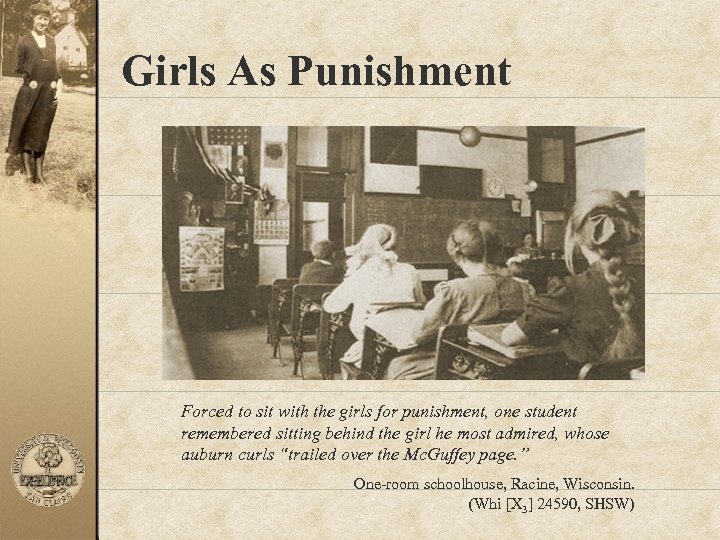

Girls As Punishment Forced to sit with the girls for punishment, one student remembered sitting behind the girl he most admired, whose auburn curls “trailed over the Mc. Guffey page. ” One-room schoolhouse, Racine, Wisconsin. (Whi [X 3] 24590, SHSW)

Girls As Punishment Forced to sit with the girls for punishment, one student remembered sitting behind the girl he most admired, whose auburn curls “trailed over the Mc. Guffey page. ” One-room schoolhouse, Racine, Wisconsin. (Whi [X 3] 24590, SHSW)

A Typical Day in a One Room Schoolhouse

A Typical Day in a One Room Schoolhouse

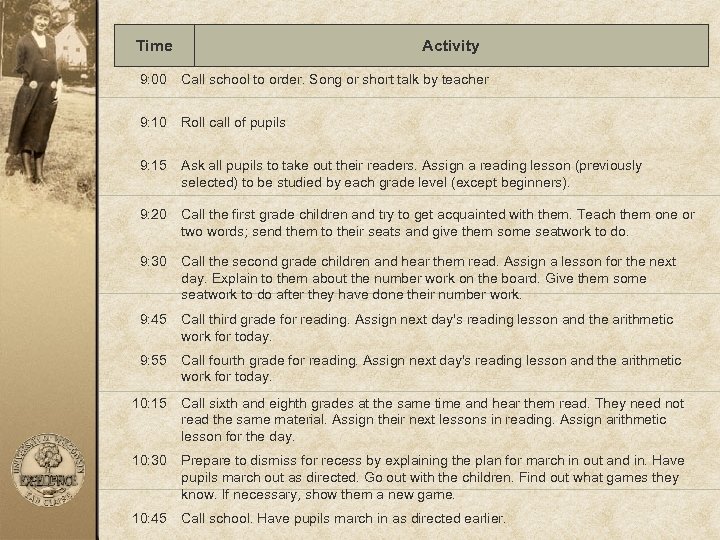

Time Activity 9: 00 Call school to order. Song or short talk by teacher 9: 10 Roll call of pupils 9: 15 Ask all pupils to take out their readers. Assign a reading lesson (previously selected) to be studied by each grade level (except beginners). 9: 20 Call the first grade children and try to get acquainted with them. Teach them one or two words; send them to their seats and give them some seatwork to do. 9: 30 Call the second grade children and hear them read. Assign a lesson for the next day. Explain to them about the number work on the board. Give them some seatwork to do after they have done their number work. 9: 45 Call third grade for reading. Assign next day's reading lesson and the arithmetic work for today. 9: 55 Call fourth grade for reading. Assign next day's reading lesson and the arithmetic work for today. 10: 15 Call sixth and eighth grades at the same time and hear them read. They need not read the same material. Assign their next lessons in reading. Assign arithmetic lesson for the day. 10: 30 Prepare to dismiss for recess by explaining the plan for march in out and in. Have pupils march out as directed. Go out with the children. Find out what games they know. If necessary, show them a new game. 10: 45 Call school. Have pupils march in as directed earlier.

Time Activity 9: 00 Call school to order. Song or short talk by teacher 9: 10 Roll call of pupils 9: 15 Ask all pupils to take out their readers. Assign a reading lesson (previously selected) to be studied by each grade level (except beginners). 9: 20 Call the first grade children and try to get acquainted with them. Teach them one or two words; send them to their seats and give them some seatwork to do. 9: 30 Call the second grade children and hear them read. Assign a lesson for the next day. Explain to them about the number work on the board. Give them some seatwork to do after they have done their number work. 9: 45 Call third grade for reading. Assign next day's reading lesson and the arithmetic work for today. 9: 55 Call fourth grade for reading. Assign next day's reading lesson and the arithmetic work for today. 10: 15 Call sixth and eighth grades at the same time and hear them read. They need not read the same material. Assign their next lessons in reading. Assign arithmetic lesson for the day. 10: 30 Prepare to dismiss for recess by explaining the plan for march in out and in. Have pupils march out as directed. Go out with the children. Find out what games they know. If necessary, show them a new game. 10: 45 Call school. Have pupils march in as directed earlier.

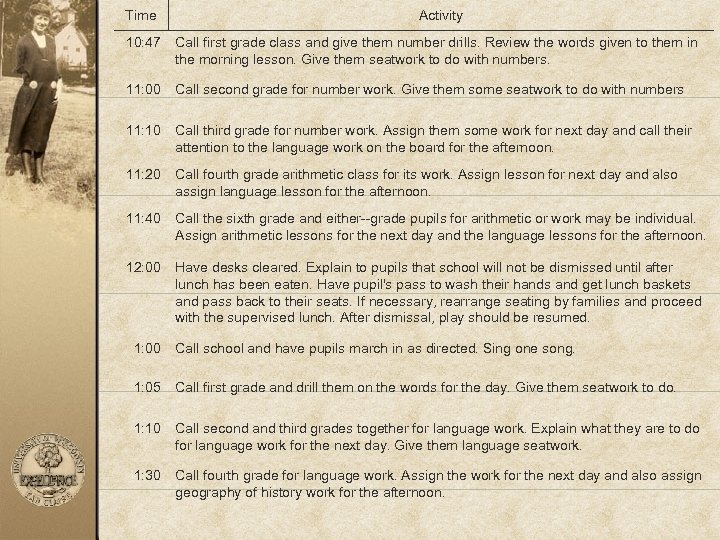

Time Activity 10: 47 Call first grade class and give them number drills. Review the words given to them in the morning lesson. Give them seatwork to do with numbers. 11: 00 Call second grade for number work. Give them some seatwork to do with numbers 11: 10 Call third grade for number work. Assign them some work for next day and call their attention to the language work on the board for the afternoon. 11: 20 Call fourth grade arithmetic class for its work. Assign lesson for next day and also assign language lesson for the afternoon. 11: 40 Call the sixth grade and either--grade pupils for arithmetic or work may be individual. Assign arithmetic lessons for the next day and the language lessons for the afternoon. 12: 00 Have desks cleared. Explain to pupils that school will not be dismissed until after lunch has been eaten. Have pupil's pass to wash their hands and get lunch baskets and pass back to their seats. If necessary, rearrange seating by families and proceed with the supervised lunch. After dismissal, play should be resumed. 1: 00 Call school and have pupils march in as directed. Sing one song. 1: 05 Call first grade and drill them on the words for the day. Give them seatwork to do. 1: 10 Call second and third grades together for language work. Explain what they are to do for language work for the next day. Give them language seatwork. 1: 30 Call fourth grade for language work. Assign the work for the next day and also assign geography of history work for the afternoon.

Time Activity 10: 47 Call first grade class and give them number drills. Review the words given to them in the morning lesson. Give them seatwork to do with numbers. 11: 00 Call second grade for number work. Give them some seatwork to do with numbers 11: 10 Call third grade for number work. Assign them some work for next day and call their attention to the language work on the board for the afternoon. 11: 20 Call fourth grade arithmetic class for its work. Assign lesson for next day and also assign language lesson for the afternoon. 11: 40 Call the sixth grade and either--grade pupils for arithmetic or work may be individual. Assign arithmetic lessons for the next day and the language lessons for the afternoon. 12: 00 Have desks cleared. Explain to pupils that school will not be dismissed until after lunch has been eaten. Have pupil's pass to wash their hands and get lunch baskets and pass back to their seats. If necessary, rearrange seating by families and proceed with the supervised lunch. After dismissal, play should be resumed. 1: 00 Call school and have pupils march in as directed. Sing one song. 1: 05 Call first grade and drill them on the words for the day. Give them seatwork to do. 1: 10 Call second and third grades together for language work. Explain what they are to do for language work for the next day. Give them language seatwork. 1: 30 Call fourth grade for language work. Assign the work for the next day and also assign geography of history work for the afternoon.

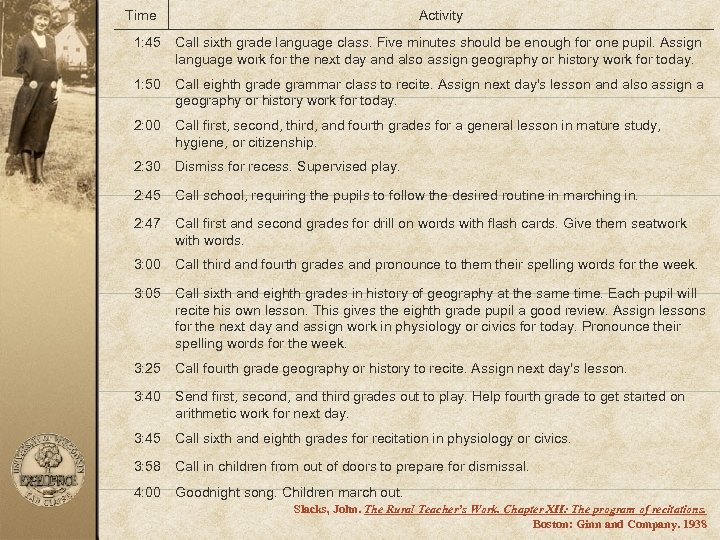

Time Activity 1: 45 Call sixth grade language class. Five minutes should be enough for one pupil. Assign language work for the next day and also assign geography or history work for today. 1: 50 Call eighth grade grammar class to recite. Assign next day's lesson and also assign a geography or history work for today. 2: 00 Call first, second, third, and fourth grades for a general lesson in mature study, hygiene, or citizenship. 2: 30 Dismiss for recess. Supervised play. 2: 45 Call school, requiring the pupils to follow the desired routine in marching in. 2: 47 Call first and second grades for drill on words with flash cards. Give them seatwork with words. 3: 00 Call third and fourth grades and pronounce to them their spelling words for the week. 3: 05 Call sixth and eighth grades in history of geography at the same time. Each pupil will recite his own lesson. This gives the eighth grade pupil a good review. Assign lessons for the next day and assign work in physiology or civics for today. Pronounce their spelling words for the week. 3: 25 Call fourth grade geography or history to recite. Assign next day's lesson. 3: 40 Send first, second, and third grades out to play. Help fourth grade to get started on arithmetic work for next day. 3: 45 Call sixth and eighth grades for recitation in physiology or civics. 3: 58 Call in children from out of doors to prepare for dismissal. 4: 00 Goodnight song. Children march out. Slacks, John. The Rural Teacher’s Work. Chapter XII: The program of recitations. Boston: Ginn and Company. 1938

Time Activity 1: 45 Call sixth grade language class. Five minutes should be enough for one pupil. Assign language work for the next day and also assign geography or history work for today. 1: 50 Call eighth grade grammar class to recite. Assign next day's lesson and also assign a geography or history work for today. 2: 00 Call first, second, third, and fourth grades for a general lesson in mature study, hygiene, or citizenship. 2: 30 Dismiss for recess. Supervised play. 2: 45 Call school, requiring the pupils to follow the desired routine in marching in. 2: 47 Call first and second grades for drill on words with flash cards. Give them seatwork with words. 3: 00 Call third and fourth grades and pronounce to them their spelling words for the week. 3: 05 Call sixth and eighth grades in history of geography at the same time. Each pupil will recite his own lesson. This gives the eighth grade pupil a good review. Assign lessons for the next day and assign work in physiology or civics for today. Pronounce their spelling words for the week. 3: 25 Call fourth grade geography or history to recite. Assign next day's lesson. 3: 40 Send first, second, and third grades out to play. Help fourth grade to get started on arithmetic work for next day. 3: 45 Call sixth and eighth grades for recitation in physiology or civics. 3: 58 Call in children from out of doors to prepare for dismissal. 4: 00 Goodnight song. Children march out. Slacks, John. The Rural Teacher’s Work. Chapter XII: The program of recitations. Boston: Ginn and Company. 1938

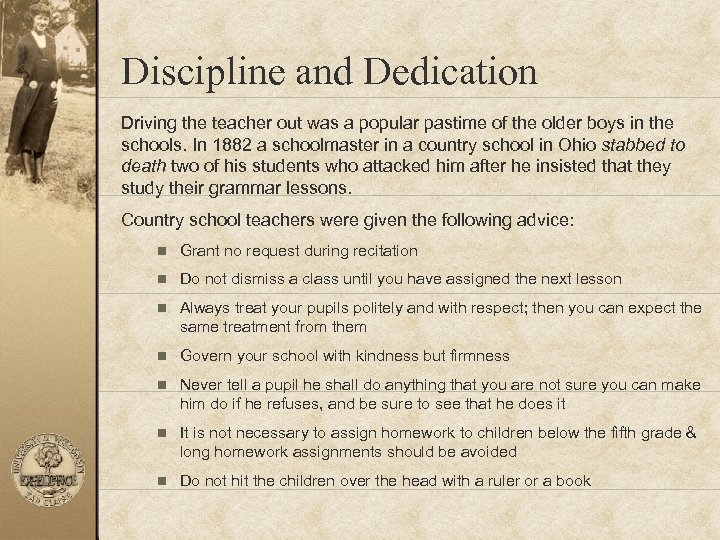

Discipline and Dedication Driving the teacher out was a popular pastime of the older boys in the schools. In 1882 a schoolmaster in a country school in Ohio stabbed to death two of his students who attacked him after he insisted that they study their grammar lessons. Country school teachers were given the following advice: n Grant no request during recitation n Do not dismiss a class until you have assigned the next lesson n Always treat your pupils politely and with respect; then you can expect the same treatment from them n Govern your school with kindness but firmness n Never tell a pupil he shall do anything that you are not sure you can make him do if he refuses, and be sure to see that he does it n It is not necessary to assign homework to children below the fifth grade & long homework assignments should be avoided n Do not hit the children over the head with a ruler or a book

Discipline and Dedication Driving the teacher out was a popular pastime of the older boys in the schools. In 1882 a schoolmaster in a country school in Ohio stabbed to death two of his students who attacked him after he insisted that they study their grammar lessons. Country school teachers were given the following advice: n Grant no request during recitation n Do not dismiss a class until you have assigned the next lesson n Always treat your pupils politely and with respect; then you can expect the same treatment from them n Govern your school with kindness but firmness n Never tell a pupil he shall do anything that you are not sure you can make him do if he refuses, and be sure to see that he does it n It is not necessary to assign homework to children below the fifth grade & long homework assignments should be avoided n Do not hit the children over the head with a ruler or a book

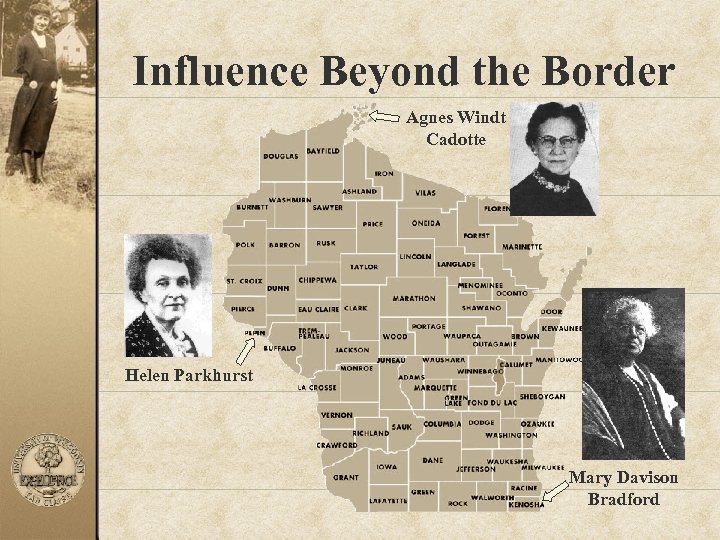

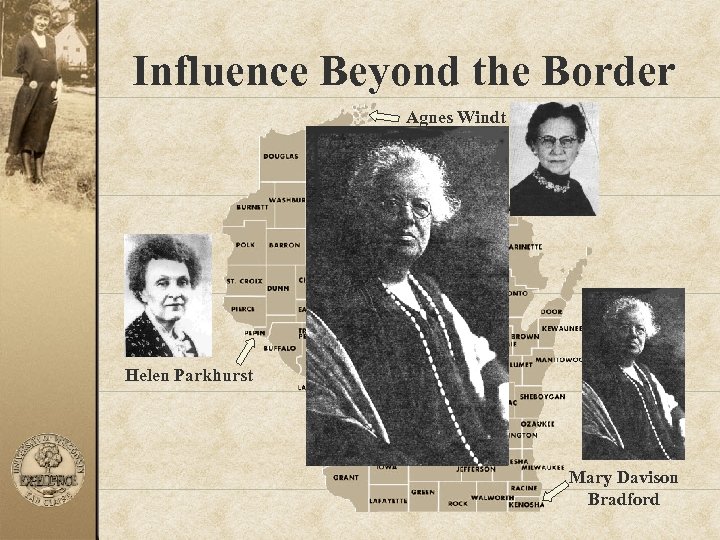

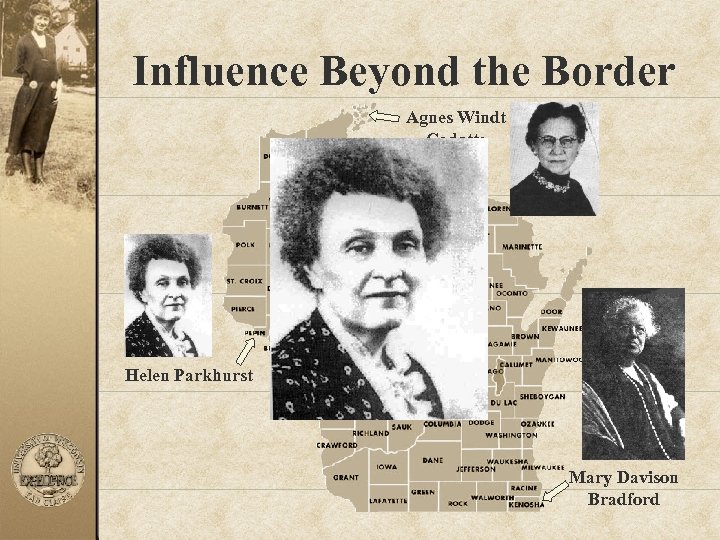

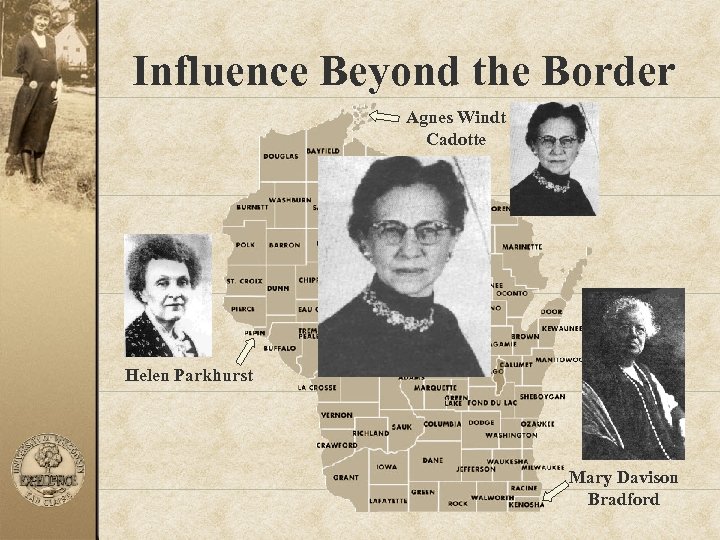

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

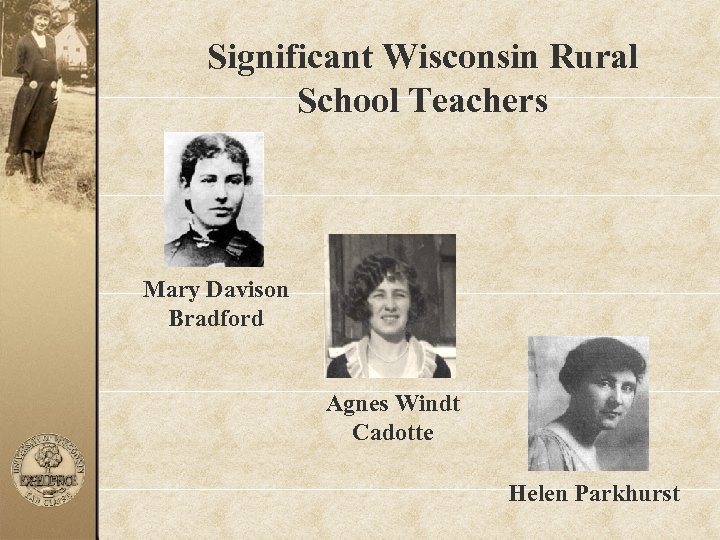

Significant Wisconsin Rural School Teachers Mary Davison Bradford Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst

Significant Wisconsin Rural School Teachers Mary Davison Bradford Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

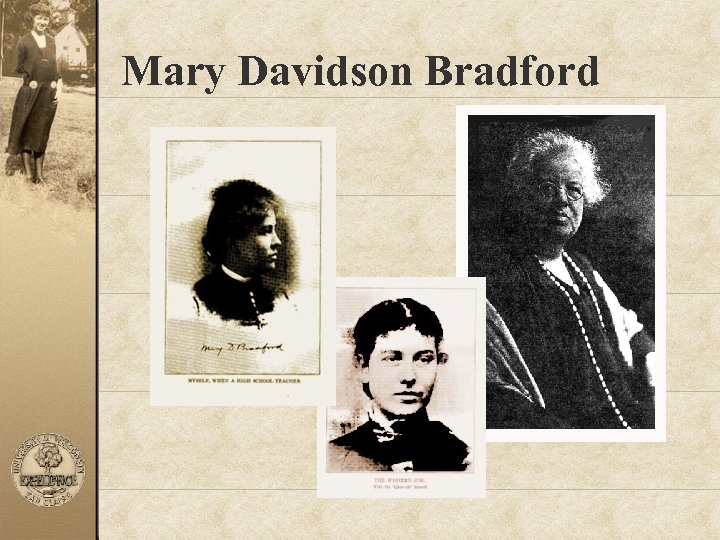

Mary Davidson Bradford The Pioneer Teacher 1856 -1943 n 1921 Bradford retired after 43 years of WI Service n 1858 began rural schooling at 2 n 1932 published memoir detailed from childhood to teacher to superintendent of schools

Mary Davidson Bradford The Pioneer Teacher 1856 -1943 n 1921 Bradford retired after 43 years of WI Service n 1858 began rural schooling at 2 n 1932 published memoir detailed from childhood to teacher to superintendent of schools

Bradford Accomplishments n Established K’s in Kenosha schools n Began 1 st WI program for the deaf n Began WI open air school for the frail n Inaugurated home economics, industrial arts & vocational training

Bradford Accomplishments n Established K’s in Kenosha schools n Began 1 st WI program for the deaf n Began WI open air school for the frail n Inaugurated home economics, industrial arts & vocational training

Bradford Biography n Born on a farm in Paris, WI in 1856 n Age 12, began HS in Kenosha n Summer school teacher while in HS n Fall 1874 took 3 rd position and attended Oshkosh State Normal School n 1876 Kenosha High School position n 1878 married William Bradford

Bradford Biography n Born on a farm in Paris, WI in 1856 n Age 12, began HS in Kenosha n Summer school teacher while in HS n Fall 1874 took 3 rd position and attended Oshkosh State Normal School n 1876 Kenosha High School position n 1878 married William Bradford

Bradford Biography n 1880 -81 son William born; husband died n 1882 returned to teaching; 10 years at Kenosha HS n Reputation as innovative teacher n University of Chicago

Bradford Biography n 1880 -81 son William born; husband died n 1882 returned to teaching; 10 years at Kenosha HS n Reputation as innovative teacher n University of Chicago

From Rural Schools to Leadership n 1894 supervising instructor at Stevens Point Normal at age 38 n Summers attended Clark University and Emerson in MA n 1906 joined faculty at Stout Institute in Menomonie, WI

From Rural Schools to Leadership n 1894 supervising instructor at Stevens Point Normal at age 38 n Summers attended Clark University and Emerson in MA n 1906 joined faculty at Stout Institute in Menomonie, WI

Public School Administrator n Appointed Asst. Superintendent Menomonie City Schools n Age 54, returned to Kenosha in 1910 to become Superintendent of Schools n 11 years tenure transformed schools into a modern public school system n New York Times “Wisconsin elects female”

Public School Administrator n Appointed Asst. Superintendent Menomonie City Schools n Age 54, returned to Kenosha in 1910 to become Superintendent of Schools n 11 years tenure transformed schools into a modern public school system n New York Times “Wisconsin elects female”

Bradford Honors n 1911 President Wisconsin State Teachers’ Assoc. n 1917 UW-Madison honorary Master of Arts Degree-first award of its kind at the UW

Bradford Honors n 1911 President Wisconsin State Teachers’ Assoc. n 1917 UW-Madison honorary Master of Arts Degree-first award of its kind at the UW

Retirement to Author n 1921 Bradford retired at age 65 after career that spanned a half century n 1932 published “The Memoirs of Mary D. Bradford”—Time Magazine “a salty, widely read autobiography”. n 1937 published “Pioneers! O Pioneers”-- pioneer education on the WI frontier n 1938 Dean of Wisconsin Educators

Retirement to Author n 1921 Bradford retired at age 65 after career that spanned a half century n 1932 published “The Memoirs of Mary D. Bradford”—Time Magazine “a salty, widely read autobiography”. n 1937 published “Pioneers! O Pioneers”-- pioneer education on the WI frontier n 1938 Dean of Wisconsin Educators

Mary Davidson Bradford

Mary Davidson Bradford

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

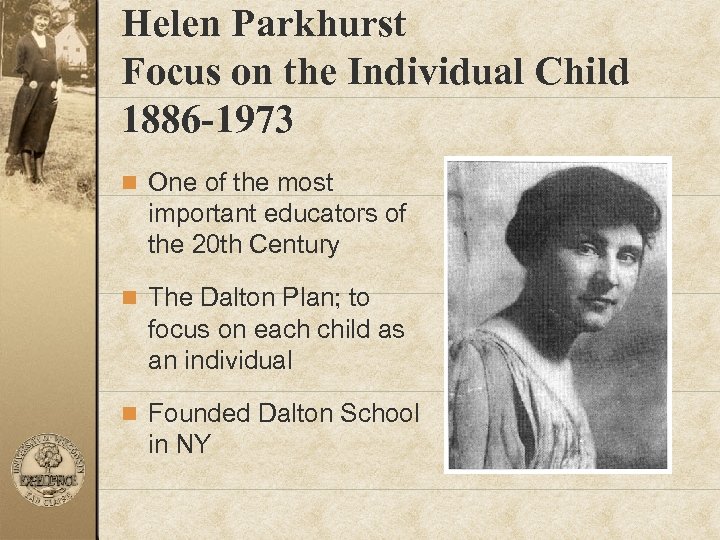

Helen Parkhurst Focus on the Individual Child 1886 -1973 n One of the most important educators of the 20 th Century n The Dalton Plan; to focus on each child as an individual n Founded Dalton School in NY

Helen Parkhurst Focus on the Individual Child 1886 -1973 n One of the most important educators of the 20 th Century n The Dalton Plan; to focus on each child as an individual n Founded Dalton School in NY

Parkhurst Accomplishments n One-room school teacher n Colleague of Maria Montessori n Among 100 greatest educators in America

Parkhurst Accomplishments n One-room school teacher n Colleague of Maria Montessori n Among 100 greatest educators in America

Parkhurst Biography n Born in Durand, WI in 1887 n Grew up with 2 brothers near Chippewa River n Learned to read at age 3; invited by Pepin County Teachers’ Institute as “guest” for model classes n Taught at Black School (still stands-barely) where she formed early impressions on how to meet individual children’s needs

Parkhurst Biography n Born in Durand, WI in 1887 n Grew up with 2 brothers near Chippewa River n Learned to read at age 3; invited by Pepin County Teachers’ Institute as “guest” for model classes n Taught at Black School (still stands-barely) where she formed early impressions on how to meet individual children’s needs

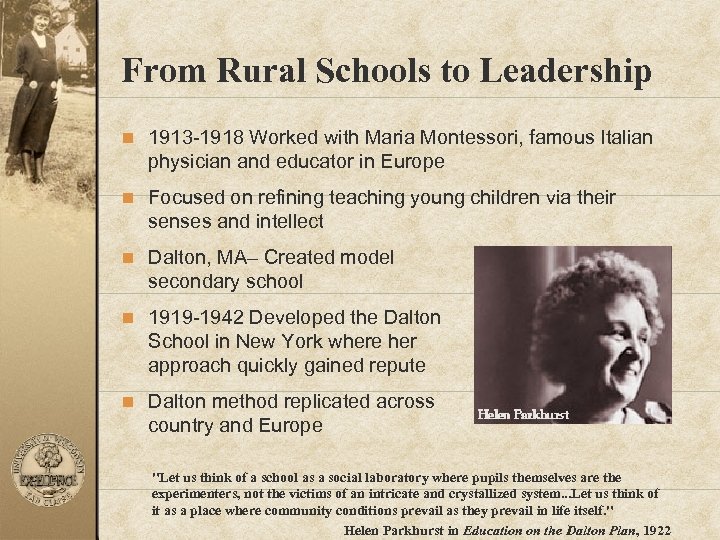

From Rural Schools to Leadership n 1913 -1918 Worked with Maria Montessori, famous Italian physician and educator in Europe n Focused on refining teaching young children via their senses and intellect n Dalton, MA– Created model secondary school n 1919 -1942 Developed the Dalton School in New York where her approach quickly gained repute n Dalton method replicated across country and Europe "Let us think of a school as a social laboratory where pupils themselves are the experimenters, not the victims of an intricate and crystallized system. . . Let us think of it as a place where community conditions prevail as they prevail in life itself. " Helen Parkhurst in Education on the Dalton Plan, 1922

From Rural Schools to Leadership n 1913 -1918 Worked with Maria Montessori, famous Italian physician and educator in Europe n Focused on refining teaching young children via their senses and intellect n Dalton, MA– Created model secondary school n 1919 -1942 Developed the Dalton School in New York where her approach quickly gained repute n Dalton method replicated across country and Europe "Let us think of a school as a social laboratory where pupils themselves are the experimenters, not the victims of an intricate and crystallized system. . . Let us think of it as a place where community conditions prevail as they prevail in life itself. " Helen Parkhurst in Education on the Dalton Plan, 1922

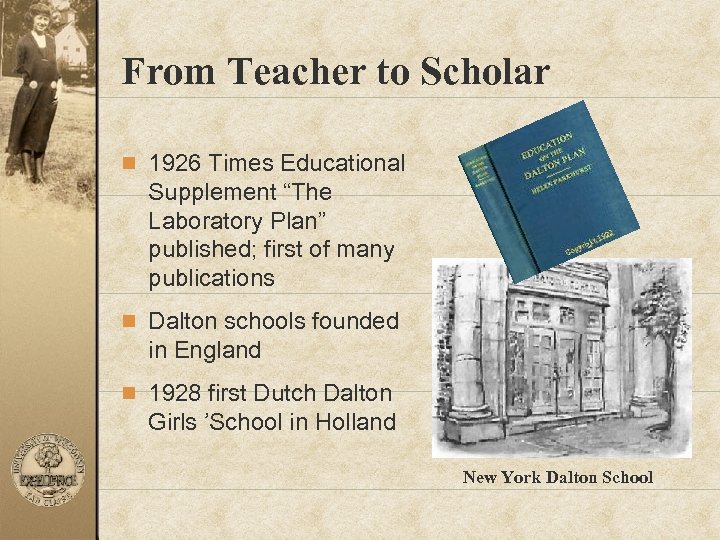

From Teacher to Scholar n 1926 Times Educational Supplement “The Laboratory Plan” published; first of many publications n Dalton schools founded in England n 1928 first Dutch Dalton Girls ’School in Holland New York Dalton School

From Teacher to Scholar n 1926 Times Educational Supplement “The Laboratory Plan” published; first of many publications n Dalton schools founded in England n 1928 first Dutch Dalton Girls ’School in Holland New York Dalton School

Helen Parkhurst

Helen Parkhurst

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

Influence Beyond the Border Agnes Windt Cadotte Helen Parkhurst Mary Davison Bradford

Agnes Windt Cadotte “Great Lady” Island Teacher 1903 -1980 n 1965 Cadotte retired after 24 years in one room school on Madeline Island n Lighthouse for highlighting literacy n Taught 3 generations of Island children and their families

Agnes Windt Cadotte “Great Lady” Island Teacher 1903 -1980 n 1965 Cadotte retired after 24 years in one room school on Madeline Island n Lighthouse for highlighting literacy n Taught 3 generations of Island children and their families

Agnes Windt Cadotte No Child is an Island 1903 -1980 n Each child one dream n Teach the whole child n Home school methods n Island children deserve best in education methods

Agnes Windt Cadotte No Child is an Island 1903 -1980 n Each child one dream n Teach the whole child n Home school methods n Island children deserve best in education methods

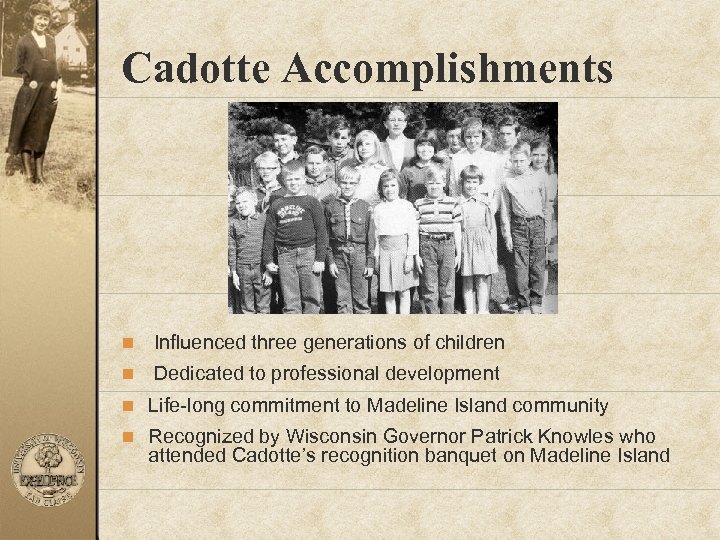

Cadotte Accomplishments n Influenced three generations of children n Dedicated to professional development n Life-long commitment to Madeline Island community n Recognized by Wisconsin Governor Patrick Knowles who attended Cadotte’s recognition banquet on Madeline Island

Cadotte Accomplishments n Influenced three generations of children n Dedicated to professional development n Life-long commitment to Madeline Island community n Recognized by Wisconsin Governor Patrick Knowles who attended Cadotte’s recognition banquet on Madeline Island

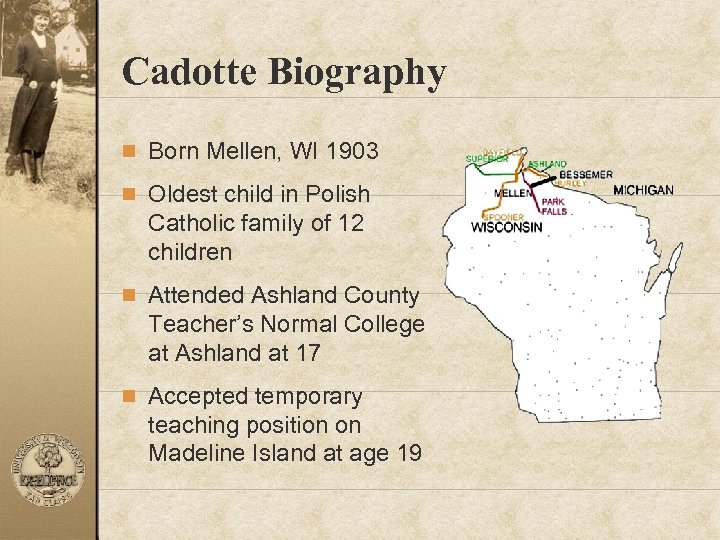

Cadotte Biography n Born Mellen, WI 1903 n Oldest child in Polish Catholic family of 12 children n Attended Ashland County Teacher’s Normal College at Ashland at 17 n Accepted temporary teaching position on Madeline Island at age 19

Cadotte Biography n Born Mellen, WI 1903 n Oldest child in Polish Catholic family of 12 children n Attended Ashland County Teacher’s Normal College at Ashland at 17 n Accepted temporary teaching position on Madeline Island at age 19

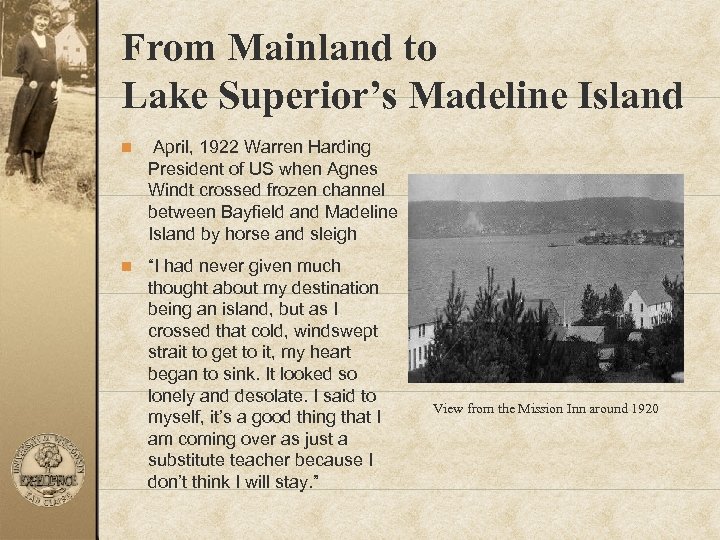

From Mainland to Lake Superior’s Madeline Island n April, 1922 Warren Harding President of US when Agnes Windt crossed frozen channel between Bayfield and Madeline Island by horse and sleigh n “I had never given much thought about my destination being an island, but as I crossed that cold, windswept strait to get to it, my heart began to sink. It looked so lonely and desolate. I said to myself, it’s a good thing that I am coming over as just a substitute teacher because I don’t think I will stay. ” View from the Mission Inn around 1920

From Mainland to Lake Superior’s Madeline Island n April, 1922 Warren Harding President of US when Agnes Windt crossed frozen channel between Bayfield and Madeline Island by horse and sleigh n “I had never given much thought about my destination being an island, but as I crossed that cold, windswept strait to get to it, my heart began to sink. It looked so lonely and desolate. I said to myself, it’s a good thing that I am coming over as just a substitute teacher because I don’t think I will stay. ” View from the Mission Inn around 1920

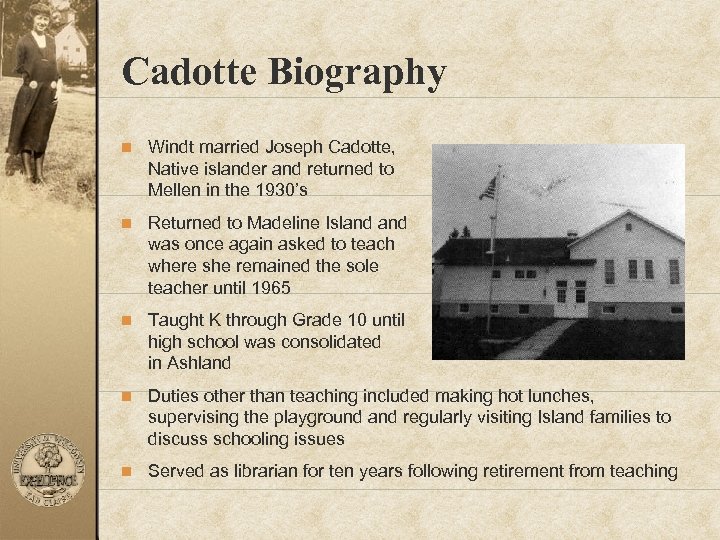

Cadotte Biography n Windt married Joseph Cadotte, Native islander and returned to Mellen in the 1930’s n Returned to Madeline Island was once again asked to teach where she remained the sole teacher until 1965 n Taught K through Grade 10 until high school was consolidated in Ashland n Duties other than teaching included making hot lunches, supervising the playground and regularly visiting Island families to discuss schooling issues n Served as librarian for ten years following retirement from teaching

Cadotte Biography n Windt married Joseph Cadotte, Native islander and returned to Mellen in the 1930’s n Returned to Madeline Island was once again asked to teach where she remained the sole teacher until 1965 n Taught K through Grade 10 until high school was consolidated in Ashland n Duties other than teaching included making hot lunches, supervising the playground and regularly visiting Island families to discuss schooling issues n Served as librarian for ten years following retirement from teaching

Cadotte Biography n Completed a bachelors degree in teaching in 1962 attending summer sessions at Northland College and Superior State University n Attended Wisconsin NEA conventions in Milwaukee and other teacher conventions in Minnesota and Wisconsin to keep abreast of teaching issues and methods n Retired in 1965 “I don’t think I would have retired then; it wasn’t my age. I just didn’t have the strength”.

Cadotte Biography n Completed a bachelors degree in teaching in 1962 attending summer sessions at Northland College and Superior State University n Attended Wisconsin NEA conventions in Milwaukee and other teacher conventions in Minnesota and Wisconsin to keep abreast of teaching issues and methods n Retired in 1965 “I don’t think I would have retired then; it wasn’t my age. I just didn’t have the strength”.

Influence Beyond Madeline Island n Most island school children found their way to “mainland” in Wisconsin-Nation n Referred by them as “A Great Lady” for dedicated service and devotion to Island children and their families n Instilled values of community service, self-development and education

Influence Beyond Madeline Island n Most island school children found their way to “mainland” in Wisconsin-Nation n Referred by them as “A Great Lady” for dedicated service and devotion to Island children and their families n Instilled values of community service, self-development and education

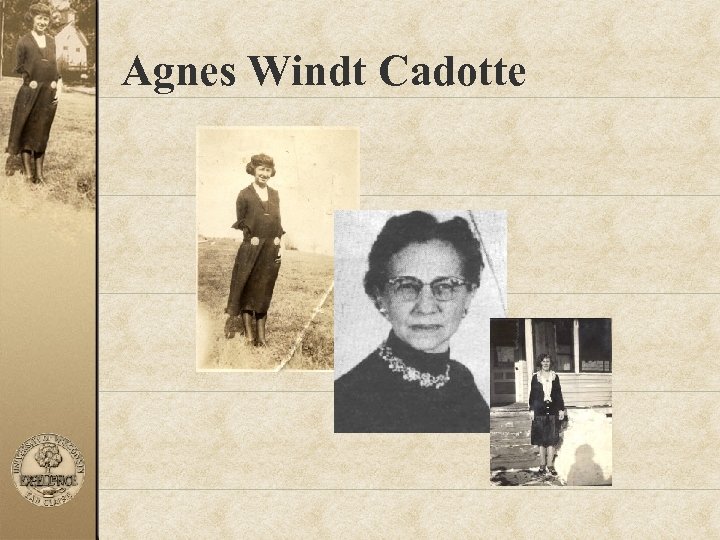

Agnes Windt Cadotte

Agnes Windt Cadotte

Combined Influence 142 years of teaching and service among Bradford, Parkhurst and Cadotte Touched thousands of lives Provided vision for potential Held sacred the gift and grace of the individual

Combined Influence 142 years of teaching and service among Bradford, Parkhurst and Cadotte Touched thousands of lives Provided vision for potential Held sacred the gift and grace of the individual