1efb29b4ab21fec3d22374921efce202.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 107

Why Computer Security • The past decade has seen an explosion in the concern for the security of information – Malicious codes (viruses, worms, etc. ) caused over $28 billion in economic losses in 2003, and will grow to over $75 billion by 2007 • Jobs and salaries for technology professionals have lessened in recent years. BUT … • Security specialists markets are expanding ! – “ Full-time information security professionals will rise almost 14% per year around the world, going past 2. 1 million in 2008” (IDC report)

Why Computer Security • The past decade has seen an explosion in the concern for the security of information – Malicious codes (viruses, worms, etc. ) caused over $28 billion in economic losses in 2003, and will grow to over $75 billion by 2007 • Jobs and salaries for technology professionals have lessened in recent years. BUT … • Security specialists markets are expanding ! – “ Full-time information security professionals will rise almost 14% per year around the world, going past 2. 1 million in 2008” (IDC report)

Why Computer Security (cont’d) • Internet attacks are increasing in frequency, severity and sophistication • Denial of service (Do. S) attacks – Cost $1. 2 billion in 2000 – 1999 CSI/FBI survey 32% of respondents detected Do. S attacks directed to their systems – Thousands of attacks per week in 2001 – Yahoo, Amazon, e. Bay, Microsoft, White House, etc. , attacked

Why Computer Security (cont’d) • Internet attacks are increasing in frequency, severity and sophistication • Denial of service (Do. S) attacks – Cost $1. 2 billion in 2000 – 1999 CSI/FBI survey 32% of respondents detected Do. S attacks directed to their systems – Thousands of attacks per week in 2001 – Yahoo, Amazon, e. Bay, Microsoft, White House, etc. , attacked

Why Computer Security (cont’d) • Virus and worms faster and powerful – Melissa, Nimda, Code Red II, Slammer … – Cause over $28 billion in economic losses in 2003, growing to over $75 billion in economic losses by 2007. – Code Red (2001): 13 hours infected >360 K machines $2. 4 billion loss – Slammer (2003): 10 minutes infected > 75 K machines $1 billion loss • Spams, phishing … • New Internet security landscape emerging: BOTNETS !

Why Computer Security (cont’d) • Virus and worms faster and powerful – Melissa, Nimda, Code Red II, Slammer … – Cause over $28 billion in economic losses in 2003, growing to over $75 billion in economic losses by 2007. – Code Red (2001): 13 hours infected >360 K machines $2. 4 billion loss – Slammer (2003): 10 minutes infected > 75 K machines $1 billion loss • Spams, phishing … • New Internet security landscape emerging: BOTNETS !

Outline • History of Security and Definitions • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outline • History of Security and Definitions • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

The History of Computing • For a long time, security was largely ignored in the community – The computer industry was in “survival mode”, struggling to overcome technological and economic hurdles – As a result, a lot of comers were cut and many compromises made – There was lots of theory, and even examples of systems built with very good security, but were largely ignored or unsuccessful • E. g. , ADA language vs. C (powerful and easy to use)

The History of Computing • For a long time, security was largely ignored in the community – The computer industry was in “survival mode”, struggling to overcome technological and economic hurdles – As a result, a lot of comers were cut and many compromises made – There was lots of theory, and even examples of systems built with very good security, but were largely ignored or unsuccessful • E. g. , ADA language vs. C (powerful and easy to use)

Computing Today is Very Different • Computers today are far from “survival mode” – Performance is abundant and the cost is very cheap – As a result, computers now ubiquitous at every facet of society • Internet – Computers are all connected and interdependent – This codependency magnifies the effects of any failures

Computing Today is Very Different • Computers today are far from “survival mode” – Performance is abundant and the cost is very cheap – As a result, computers now ubiquitous at every facet of society • Internet – Computers are all connected and interdependent – This codependency magnifies the effects of any failures

Biological Analogy • Computing today is very homogeneous. – A single architecture and a handful of OS dominates • In biology, homogeneous populations are in danger – A single disease or virus can wipe them out overnight because they all share the same weakness – The disease only needs a vector to travel among hosts • Computers are like the animals, the Internet provides the vector. – It is like having only one kind of cow in the world, and having them drink from one single pool of water!

Biological Analogy • Computing today is very homogeneous. – A single architecture and a handful of OS dominates • In biology, homogeneous populations are in danger – A single disease or virus can wipe them out overnight because they all share the same weakness – The disease only needs a vector to travel among hosts • Computers are like the animals, the Internet provides the vector. – It is like having only one kind of cow in the world, and having them drink from one single pool of water!

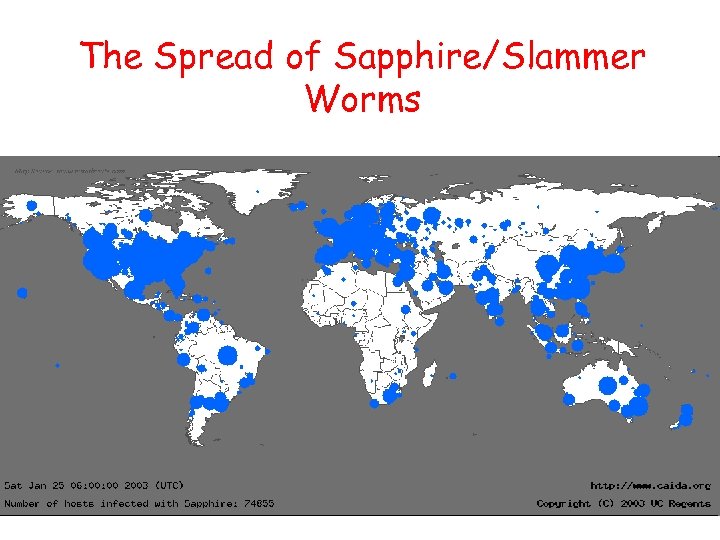

The Spread of Sapphire/Slammer Worms

The Spread of Sapphire/Slammer Worms

The Flash Worm • Slammer worm infected 75, 000 machines in <15 minutes • A properly designed worm, flash worm, can take less than 1 second to compromise 1 million vulnerable machines in the Internet – The Top Speed of Flash Worms. S. Staniford, D. Moore, V. Paxson and N. Weaver, ACM WORM Workshop 2004. – Exploit many vectors such as P 2 P file sharing, intelligent scanning, hitlists, etc.

The Flash Worm • Slammer worm infected 75, 000 machines in <15 minutes • A properly designed worm, flash worm, can take less than 1 second to compromise 1 million vulnerable machines in the Internet – The Top Speed of Flash Worms. S. Staniford, D. Moore, V. Paxson and N. Weaver, ACM WORM Workshop 2004. – Exploit many vectors such as P 2 P file sharing, intelligent scanning, hitlists, etc.

The Definition of Computer Security • Security is a state of well-being of information and infrastructures in which the possibility of successful yet undetected theft, tampering, and disruption of information and services is kept low or tolerable • Security rests on confidentiality, authenticity, integrity, and availability

The Definition of Computer Security • Security is a state of well-being of information and infrastructures in which the possibility of successful yet undetected theft, tampering, and disruption of information and services is kept low or tolerable • Security rests on confidentiality, authenticity, integrity, and availability

The Basic Components • Confidentiality is the concealment of information or resources. – E. g. , only sender, intended receiver should “understand” message contents • Authenticity is the identification and assurance of the origin of information. • Integrity refers to the trustworthiness of data or resources in terms of preventing improper and unauthorized changes. • Availability refers to the ability to use the information or resource desired.

The Basic Components • Confidentiality is the concealment of information or resources. – E. g. , only sender, intended receiver should “understand” message contents • Authenticity is the identification and assurance of the origin of information. • Integrity refers to the trustworthiness of data or resources in terms of preventing improper and unauthorized changes. • Availability refers to the ability to use the information or resource desired.

Security Threats and Attacks • A threat/vulnerability is a potential violation of security. – Flaws in design, implementation, and operation. • An attack is any action that violates security. – Active adversary • An attack has an implicit concept of “intent” – Router mis-configuration or server crash can also cause loss of availability, but they are not attacks

Security Threats and Attacks • A threat/vulnerability is a potential violation of security. – Flaws in design, implementation, and operation. • An attack is any action that violates security. – Active adversary • An attack has an implicit concept of “intent” – Router mis-configuration or server crash can also cause loss of availability, but they are not attacks

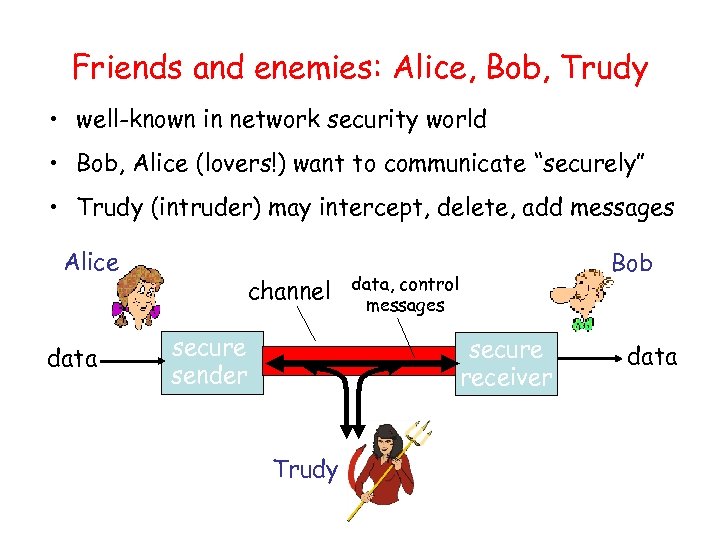

Friends and enemies: Alice, Bob, Trudy • well-known in network security world • Bob, Alice (lovers!) want to communicate “securely” • Trudy (intruder) may intercept, delete, add messages Alice data channel secure sender Bob data, control messages secure receiver Trudy data

Friends and enemies: Alice, Bob, Trudy • well-known in network security world • Bob, Alice (lovers!) want to communicate “securely” • Trudy (intruder) may intercept, delete, add messages Alice data channel secure sender Bob data, control messages secure receiver Trudy data

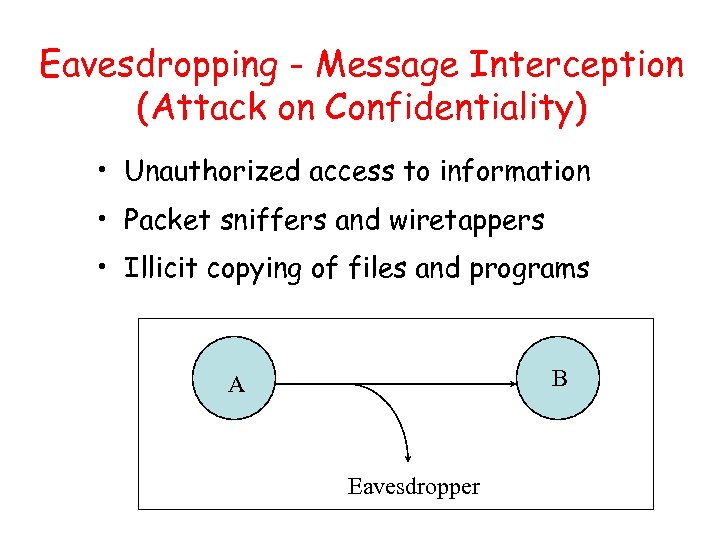

Eavesdropping - Message Interception (Attack on Confidentiality) • Unauthorized access to information • Packet sniffers and wiretappers • Illicit copying of files and programs B A Eavesdropper

Eavesdropping - Message Interception (Attack on Confidentiality) • Unauthorized access to information • Packet sniffers and wiretappers • Illicit copying of files and programs B A Eavesdropper

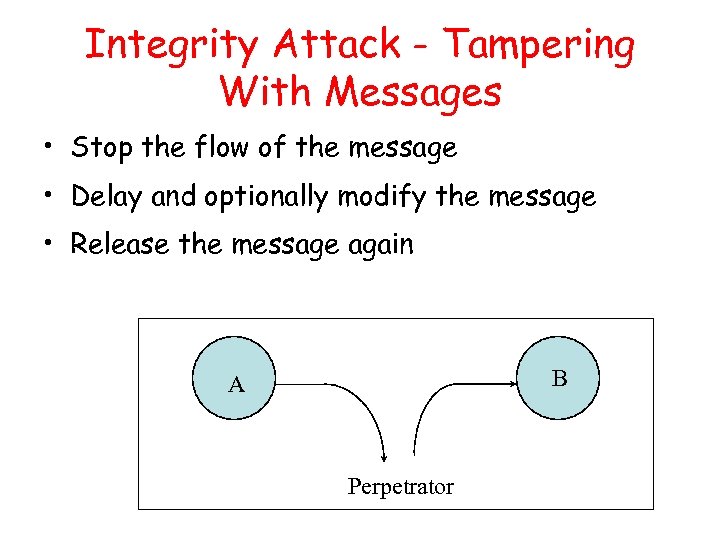

Integrity Attack - Tampering With Messages • Stop the flow of the message • Delay and optionally modify the message • Release the message again B A Perpetrator

Integrity Attack - Tampering With Messages • Stop the flow of the message • Delay and optionally modify the message • Release the message again B A Perpetrator

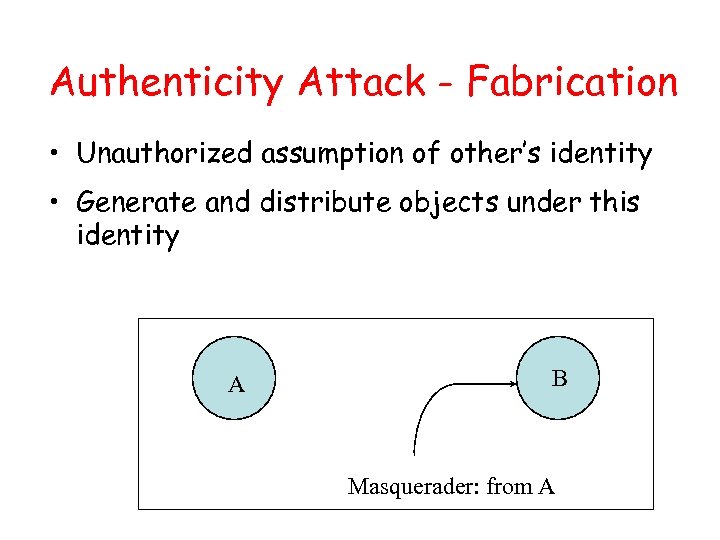

Authenticity Attack - Fabrication • Unauthorized assumption of other’s identity • Generate and distribute objects under this identity A B Masquerader: from A

Authenticity Attack - Fabrication • Unauthorized assumption of other’s identity • Generate and distribute objects under this identity A B Masquerader: from A

Attack on Availability • Destroy hardware (cutting fiber) or software • Modify software in a subtle way (alias commands) • Corrupt packets in transit A • Blatant denial of service (Do. S): – Crashing the server – Overwhelm the server (use up its resource) B

Attack on Availability • Destroy hardware (cutting fiber) or software • Modify software in a subtle way (alias commands) • Corrupt packets in transit A • Blatant denial of service (Do. S): – Crashing the server – Overwhelm the server (use up its resource) B

Classify Security Attacks as • Passive attacks - eavesdropping on, or monitoring of, transmissions to: – obtain message contents, or – monitor traffic flows • Active attacks – modification of data stream to: – masquerade of one entity as some other – replay previous messages – modify messages in transit – denial of service

Classify Security Attacks as • Passive attacks - eavesdropping on, or monitoring of, transmissions to: – obtain message contents, or – monitor traffic flows • Active attacks – modification of data stream to: – masquerade of one entity as some other – replay previous messages – modify messages in transit – denial of service

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Basic Terminology • plaintext - the original message • ciphertext - the coded message • cipher - algorithm for transforming plaintext to ciphertext • key - info used in cipher known only to sender/receiver • encipher (encrypt) - converting plaintext to ciphertext • decipher (decrypt) - recovering ciphertext from plaintext • cryptography - study of encryption principles/methods • cryptanalysis (codebreaking) - the study of principles/ methods of deciphering ciphertext without knowing key • cryptology - the field of both cryptography and cryptanalysis

Basic Terminology • plaintext - the original message • ciphertext - the coded message • cipher - algorithm for transforming plaintext to ciphertext • key - info used in cipher known only to sender/receiver • encipher (encrypt) - converting plaintext to ciphertext • decipher (decrypt) - recovering ciphertext from plaintext • cryptography - study of encryption principles/methods • cryptanalysis (codebreaking) - the study of principles/ methods of deciphering ciphertext without knowing key • cryptology - the field of both cryptography and cryptanalysis

Classification of Cryptography • Number of keys used – Hash functions: no key – Secret key cryptography: one key – Public key cryptography: two keys - public, private • Type of encryption operations used – substitution / transposition / product • Way in which plaintext is processed – block / stream

Classification of Cryptography • Number of keys used – Hash functions: no key – Secret key cryptography: one key – Public key cryptography: two keys - public, private • Type of encryption operations used – substitution / transposition / product • Way in which plaintext is processed – block / stream

Secret Key vs. Secret Algorithm • Secret algorithm: additional hurdle • Hard to keep secret if used widely: – Reverse engineering, social engineering • Commercial: published – Wide review, trust • Military: avoid giving enemy good ideas

Secret Key vs. Secret Algorithm • Secret algorithm: additional hurdle • Hard to keep secret if used widely: – Reverse engineering, social engineering • Commercial: published – Wide review, trust • Military: avoid giving enemy good ideas

Cryptanalysis Scheme • Ciphertext only: – Exhaustive search until “recognizable plaintext” – Need enough ciphertext • Known plaintext: – Secret may be revealed (by spy, time), thus

Cryptanalysis Scheme • Ciphertext only: – Exhaustive search until “recognizable plaintext” – Need enough ciphertext • Known plaintext: – Secret may be revealed (by spy, time), thus

Unconditional vs. Computational Security • Unconditional security – No matter how much computer power is available, the cipher cannot be broken – The ciphertext provides insufficient information to uniquely determine the corresponding plaintext – Only one-time pad scheme qualifies • Computational security – The cost of breaking the cipher exceeds the value of the encrypted info – The time required to break the cipher exceeds the useful lifetime of the info

Unconditional vs. Computational Security • Unconditional security – No matter how much computer power is available, the cipher cannot be broken – The ciphertext provides insufficient information to uniquely determine the corresponding plaintext – Only one-time pad scheme qualifies • Computational security – The cost of breaking the cipher exceeds the value of the encrypted info – The time required to break the cipher exceeds the useful lifetime of the info

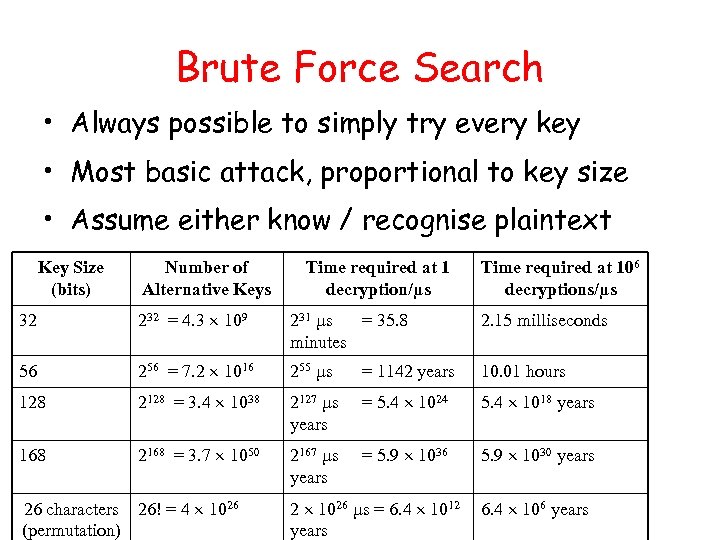

Brute Force Search • Always possible to simply try every key • Most basic attack, proportional to key size • Assume either know / recognise plaintext Key Size (bits) Number of Alternative Keys Time required at 1 decryption/µs Time required at 106 decryptions/µs 32 232 = 4. 3 109 231 µs = 35. 8 minutes 2. 15 milliseconds 56 256 = 7. 2 1016 255 µs = 1142 years 10. 01 hours 128 2128 = 3. 4 1038 2127 µs years = 5. 4 1024 5. 4 1018 years 168 2168 = 3. 7 1050 2167 µs years = 5. 9 1036 5. 9 1030 years 26 characters 26! = 4 1026 (permutation) 2 1026 µs = 6. 4 1012 years 6. 4 106 years

Brute Force Search • Always possible to simply try every key • Most basic attack, proportional to key size • Assume either know / recognise plaintext Key Size (bits) Number of Alternative Keys Time required at 1 decryption/µs Time required at 106 decryptions/µs 32 232 = 4. 3 109 231 µs = 35. 8 minutes 2. 15 milliseconds 56 256 = 7. 2 1016 255 µs = 1142 years 10. 01 hours 128 2128 = 3. 4 1038 2127 µs years = 5. 4 1024 5. 4 1018 years 168 2168 = 3. 7 1050 2167 µs years = 5. 9 1036 5. 9 1030 years 26 characters 26! = 4 1026 (permutation) 2 1026 µs = 6. 4 1012 years 6. 4 106 years

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Classical Symmetric Cipher – Substitution Cipher – Transposition Cipher • Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Classical Symmetric Cipher – Substitution Cipher – Transposition Cipher • Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

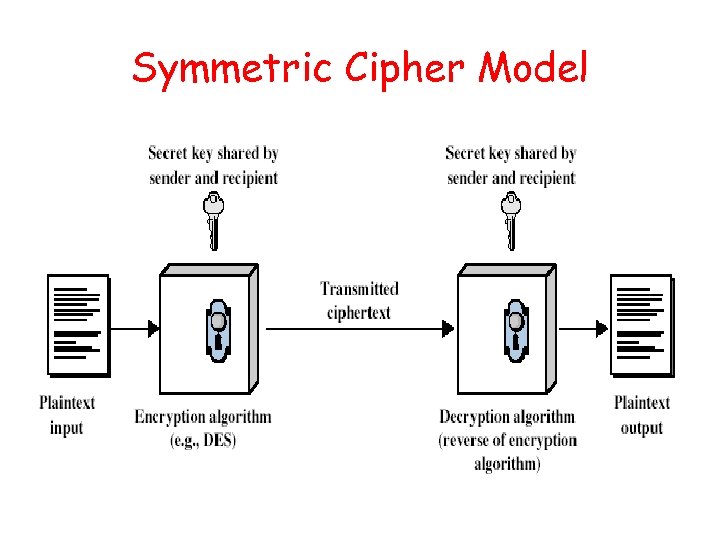

Symmetric Cipher Model

Symmetric Cipher Model

Requirements • Two requirements for secure use of symmetric encryption: – a strong encryption algorithm – a secret key known only to sender / receiver Y = EK(X) X = DK(Y) • Assume encryption algorithm is known • Implies a secure channel to distribute key

Requirements • Two requirements for secure use of symmetric encryption: – a strong encryption algorithm – a secret key known only to sender / receiver Y = EK(X) X = DK(Y) • Assume encryption algorithm is known • Implies a secure channel to distribute key

Classical Substitution Ciphers • Letters of plaintext are replaced by other letters or by numbers or symbols • Plaintext is viewed as a sequence of bits, then substitution replaces plaintext bit patterns with ciphertext bit patterns

Classical Substitution Ciphers • Letters of plaintext are replaced by other letters or by numbers or symbols • Plaintext is viewed as a sequence of bits, then substitution replaces plaintext bit patterns with ciphertext bit patterns

Caesar Cipher • Earliest known substitution cipher • Replaces each letter by 3 rd letter on • Example: meet me after the toga party PHHW PH DIWHU WKH WRJD SDUWB

Caesar Cipher • Earliest known substitution cipher • Replaces each letter by 3 rd letter on • Example: meet me after the toga party PHHW PH DIWHU WKH WRJD SDUWB

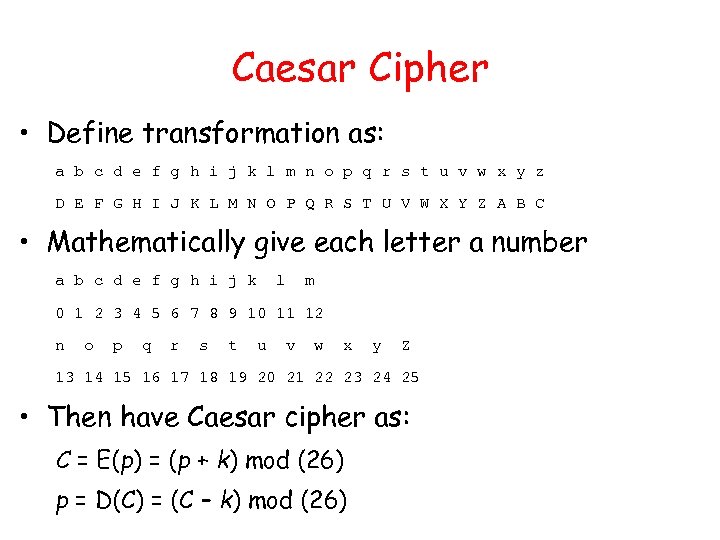

Caesar Cipher • Define transformation as: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C • Mathematically give each letter a number a b c d e f g h i j k l m 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 n o p q r s t u v w x y Z 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 • Then have Caesar cipher as: C = E(p) = (p + k) mod (26) p = D(C) = (C – k) mod (26)

Caesar Cipher • Define transformation as: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C • Mathematically give each letter a number a b c d e f g h i j k l m 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 n o p q r s t u v w x y Z 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 • Then have Caesar cipher as: C = E(p) = (p + k) mod (26) p = D(C) = (C – k) mod (26)

Cryptanalysis of Caesar Cipher • Only have 25 possible ciphers – A maps to B, . . Z • Given ciphertext, just try all shifts of letters • Do need to recognize when have plaintext • E. g. , break ciphertext "GCUA VQ DTGCM"

Cryptanalysis of Caesar Cipher • Only have 25 possible ciphers – A maps to B, . . Z • Given ciphertext, just try all shifts of letters • Do need to recognize when have plaintext • E. g. , break ciphertext "GCUA VQ DTGCM"

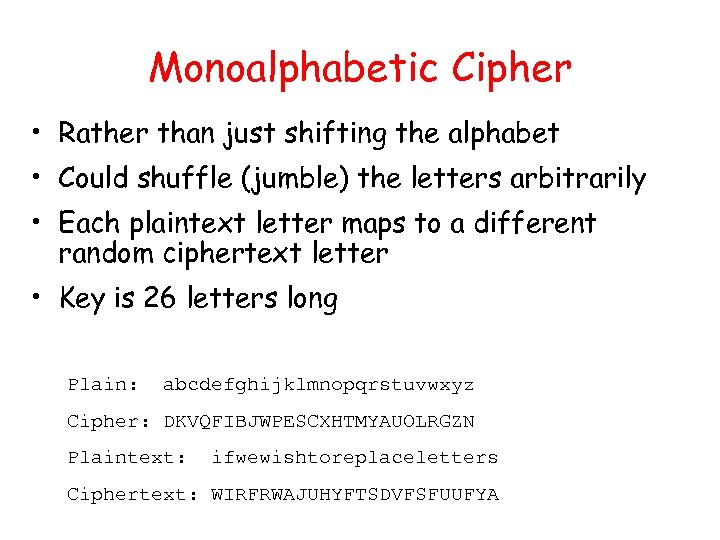

Monoalphabetic Cipher • Rather than just shifting the alphabet • Could shuffle (jumble) the letters arbitrarily • Each plaintext letter maps to a different random ciphertext letter • Key is 26 letters long Plain: abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz Cipher: DKVQFIBJWPESCXHTMYAUOLRGZN Plaintext: ifwewishtoreplaceletters Ciphertext: WIRFRWAJUHYFTSDVFSFUUFYA

Monoalphabetic Cipher • Rather than just shifting the alphabet • Could shuffle (jumble) the letters arbitrarily • Each plaintext letter maps to a different random ciphertext letter • Key is 26 letters long Plain: abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz Cipher: DKVQFIBJWPESCXHTMYAUOLRGZN Plaintext: ifwewishtoreplaceletters Ciphertext: WIRFRWAJUHYFTSDVFSFUUFYA

Monoalphabetic Cipher Security • Now have a total of 26! = 4 x 1026 keys • Is that secure? • Problem is language characteristics – Human languages are redundant – Letters are not equally commonly used

Monoalphabetic Cipher Security • Now have a total of 26! = 4 x 1026 keys • Is that secure? • Problem is language characteristics – Human languages are redundant – Letters are not equally commonly used

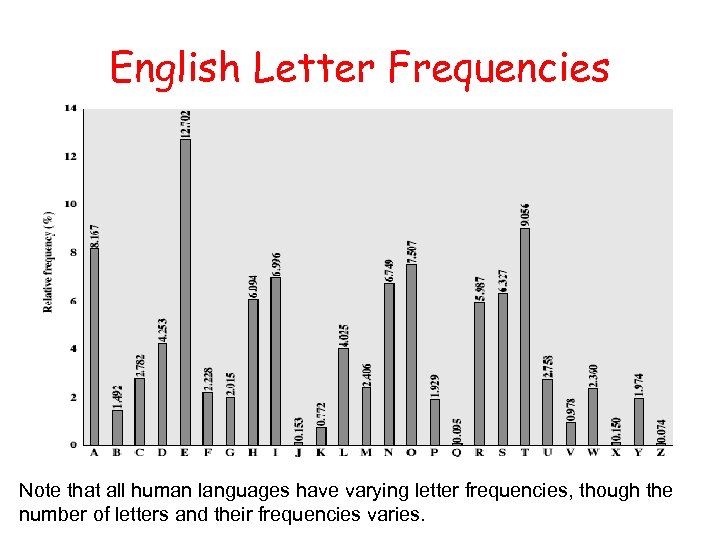

English Letter Frequencies Note that all human languages have varying letter frequencies, though the number of letters and their frequencies varies.

English Letter Frequencies Note that all human languages have varying letter frequencies, though the number of letters and their frequencies varies.

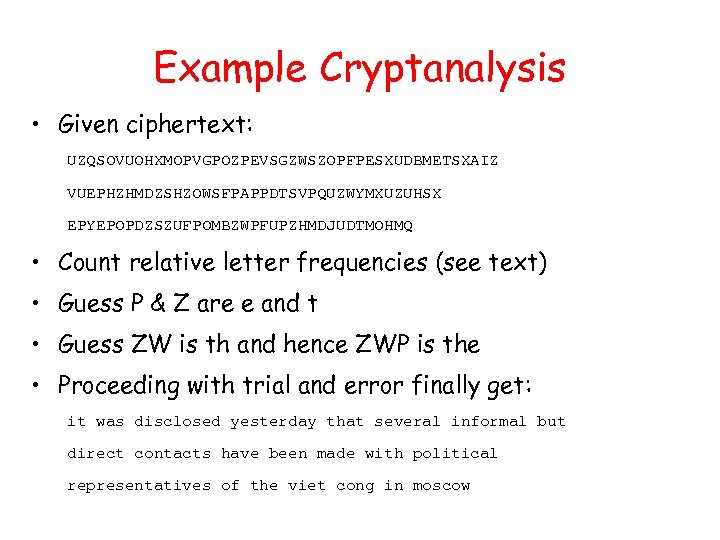

Example Cryptanalysis • Given ciphertext: UZQSOVUOHXMOPVGPOZPEVSGZWSZOPFPESXUDBMETSXAIZ VUEPHZHMDZSHZOWSFPAPPDTSVPQUZWYMXUZUHSX EPYEPOPDZSZUFPOMBZWPFUPZHMDJUDTMOHMQ • Count relative letter frequencies (see text) • Guess P & Z are e and t • Guess ZW is th and hence ZWP is the • Proceeding with trial and error finally get: it was disclosed yesterday that several informal but direct contacts have been made with political representatives of the viet cong in moscow

Example Cryptanalysis • Given ciphertext: UZQSOVUOHXMOPVGPOZPEVSGZWSZOPFPESXUDBMETSXAIZ VUEPHZHMDZSHZOWSFPAPPDTSVPQUZWYMXUZUHSX EPYEPOPDZSZUFPOMBZWPFUPZHMDJUDTMOHMQ • Count relative letter frequencies (see text) • Guess P & Z are e and t • Guess ZW is th and hence ZWP is the • Proceeding with trial and error finally get: it was disclosed yesterday that several informal but direct contacts have been made with political representatives of the viet cong in moscow

One-Time Pad • If a truly random key as long as the message is used, the cipher will be secure - One-Time pad • E. g. , a random sequence of 0’s and 1’s XORed to plaintext, no repetition of keys • Unbreakable since ciphertext bears no statistical relationship to the plaintext • For any plaintext, it needs a random key of the same length – Hard to generate large amount of keys • Have problem of safe distribution of key

One-Time Pad • If a truly random key as long as the message is used, the cipher will be secure - One-Time pad • E. g. , a random sequence of 0’s and 1’s XORed to plaintext, no repetition of keys • Unbreakable since ciphertext bears no statistical relationship to the plaintext • For any plaintext, it needs a random key of the same length – Hard to generate large amount of keys • Have problem of safe distribution of key

Transposition Ciphers • Now consider classical transposition or permutation ciphers • These hide the message by rearranging the letter order, without altering the actual letters used • Any shortcut for breaking it? • Can recognise these since have the same frequency distribution as the original text

Transposition Ciphers • Now consider classical transposition or permutation ciphers • These hide the message by rearranging the letter order, without altering the actual letters used • Any shortcut for breaking it? • Can recognise these since have the same frequency distribution as the original text

Rail Fence Cipher • Write message letters out diagonally over a number of rows • Then read off cipher row by row • E. g. , write message out as: m e m a t r h t g p r y e t e f e t e o a a t • Giving ciphertext MEMATRHTGPRYETEFETEOAAT

Rail Fence Cipher • Write message letters out diagonally over a number of rows • Then read off cipher row by row • E. g. , write message out as: m e m a t r h t g p r y e t e f e t e o a a t • Giving ciphertext MEMATRHTGPRYETEFETEOAAT

Product Ciphers • Ciphers using substitutions or transpositions are not secure because of language characteristics • Hence consider using several ciphers in succession to make harder, but: – Two substitutions make another substitution – Two transpositions make a more complex transposition – But a substitution followed by a transposition makes a new much harder cipher • This is bridge from classical to modern ciphers

Product Ciphers • Ciphers using substitutions or transpositions are not secure because of language characteristics • Hence consider using several ciphers in succession to make harder, but: – Two substitutions make another substitution – Two transpositions make a more complex transposition – But a substitution followed by a transposition makes a new much harder cipher • This is bridge from classical to modern ciphers

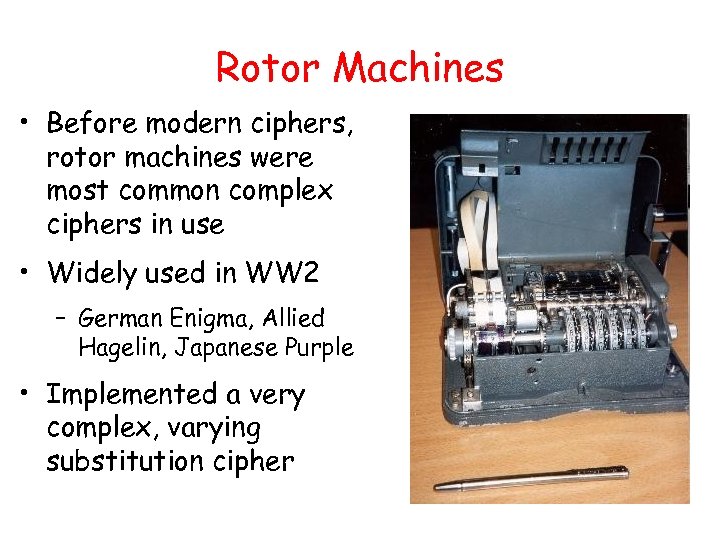

Rotor Machines • Before modern ciphers, rotor machines were most common complex ciphers in use • Widely used in WW 2 – German Enigma, Allied Hagelin, Japanese Purple • Implemented a very complex, varying substitution cipher

Rotor Machines • Before modern ciphers, rotor machines were most common complex ciphers in use • Widely used in WW 2 – German Enigma, Allied Hagelin, Japanese Purple • Implemented a very complex, varying substitution cipher

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Classical Symmetric Cipher • Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES/AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outline • Overview of Cryptography • Classical Symmetric Cipher • Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES/AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages in into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted • Like a substitution on very big characters – 64 -bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting • Many current ciphers are block ciphers, one of the most widely used types of cryptographic algorithms

Block vs Stream Ciphers • Block ciphers process messages in into blocks, each of which is then en/decrypted • Like a substitution on very big characters – 64 -bits or more • Stream ciphers process messages a bit or byte at a time when en/decrypting • Many current ciphers are block ciphers, one of the most widely used types of cryptographic algorithms

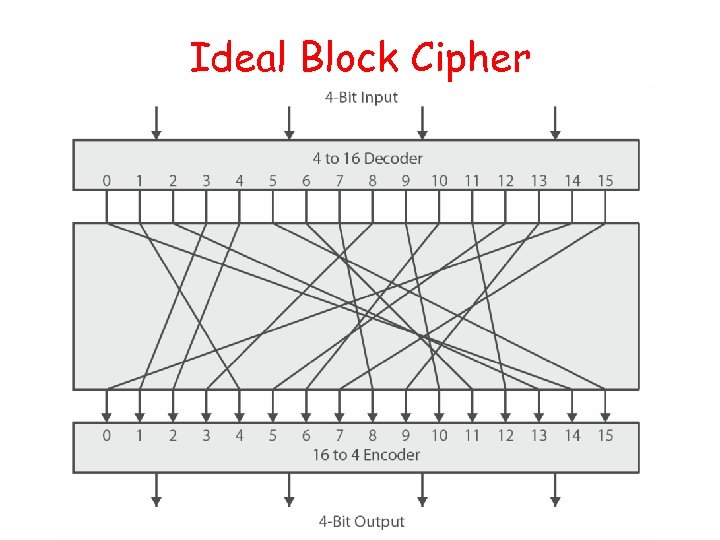

Block Cipher Principles • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64 -bit block • Instead create from smaller building blocks • Using idea of a product cipher

Block Cipher Principles • Most symmetric block ciphers are based on a Feistel Cipher Structure • Block ciphers look like an extremely large substitution • Would need table of 264 entries for a 64 -bit block • Instead create from smaller building blocks • Using idea of a product cipher

Ideal Block Cipher

Ideal Block Cipher

![Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • Substitution-permutation (S-P) networks [Shannon, 1949] – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • Substitution-permutation (S-P) networks [Shannon, 1949] – modern substitution-transposition product cipher •](https://present5.com/presentation/1efb29b4ab21fec3d22374921efce202/image-46.jpg) Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • Substitution-permutation (S-P) networks [Shannon, 1949] – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) • provide confusion and diffusion of message

Substitution-Permutation Ciphers • Substitution-permutation (S-P) networks [Shannon, 1949] – modern substitution-transposition product cipher • These form the basis of modern block ciphers • S-P networks are based on the two primitive cryptographic operations – substitution (S-box) – permutation (P-box) • provide confusion and diffusion of message

Confusion and Diffusion • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this • More practically Shannon suggested S-P networks to obtain: • Diffusion – dissipates statistical structure of plaintext over bulk of ciphertext • Confusion – makes relationship between ciphertext and key as complex as possible

Confusion and Diffusion • Cipher needs to completely obscure statistical properties of original message • A one-time pad does this • More practically Shannon suggested S-P networks to obtain: • Diffusion – dissipates statistical structure of plaintext over bulk of ciphertext • Confusion – makes relationship between ciphertext and key as complex as possible

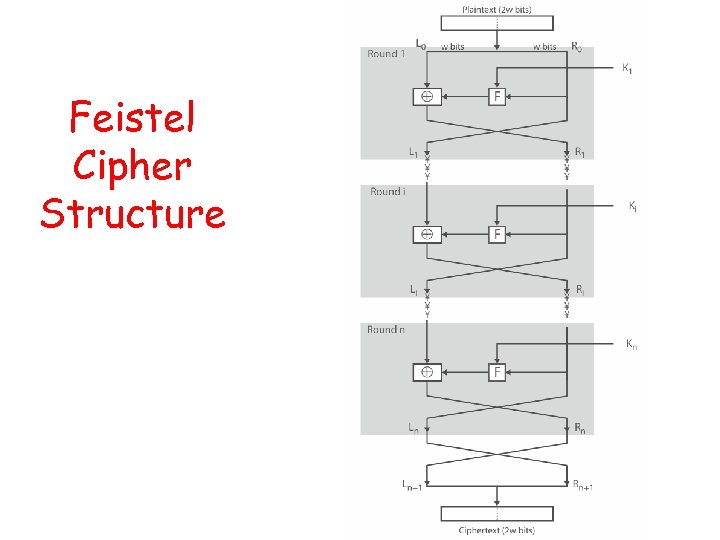

Feistel Cipher Structure • Feistel cipher implements Shannon’s S-P network concept – based on invertible product cipher • Process through multiple rounds which – partitions input block into two halves – perform a substitution on left data half – based on round function of right half & subkey – then have permutation swapping halves

Feistel Cipher Structure • Feistel cipher implements Shannon’s S-P network concept – based on invertible product cipher • Process through multiple rounds which – partitions input block into two halves – perform a substitution on left data half – based on round function of right half & subkey – then have permutation swapping halves

Feistel Cipher Structure

Feistel Cipher Structure

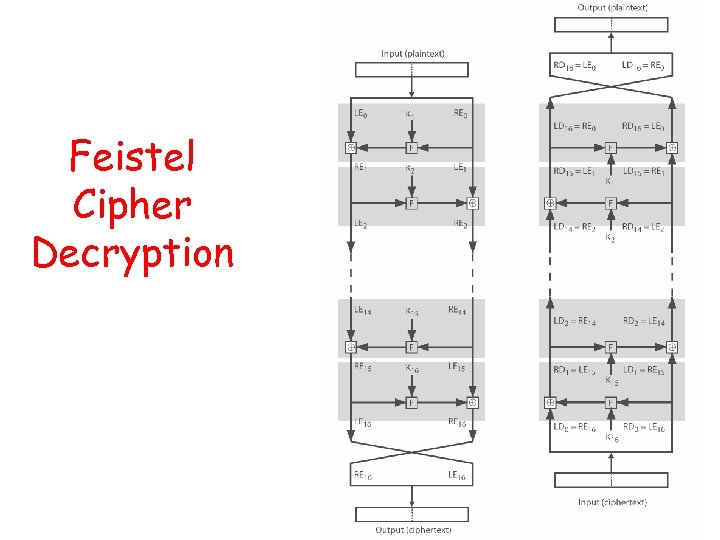

Feistel Cipher Decryption

Feistel Cipher Decryption

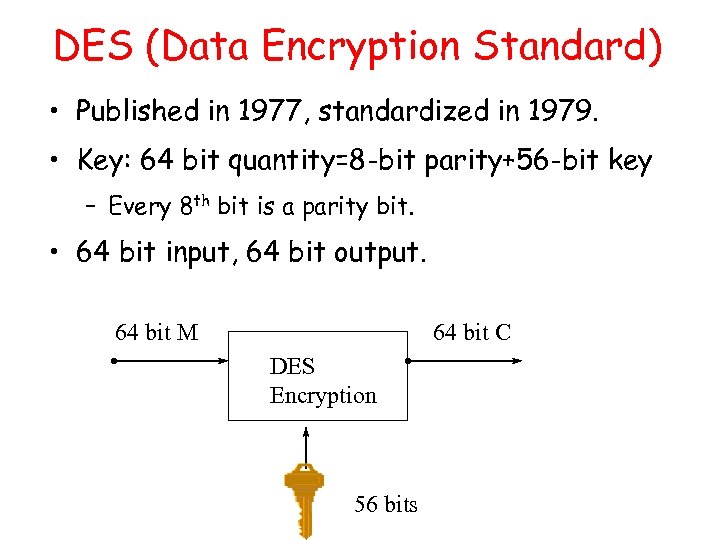

DES (Data Encryption Standard) • Published in 1977, standardized in 1979. • Key: 64 bit quantity=8 -bit parity+56 -bit key – Every 8 th bit is a parity bit. • 64 bit input, 64 bit output. 64 bit M 64 bit C DES Encryption 56 bits

DES (Data Encryption Standard) • Published in 1977, standardized in 1979. • Key: 64 bit quantity=8 -bit parity+56 -bit key – Every 8 th bit is a parity bit. • 64 bit input, 64 bit output. 64 bit M 64 bit C DES Encryption 56 bits

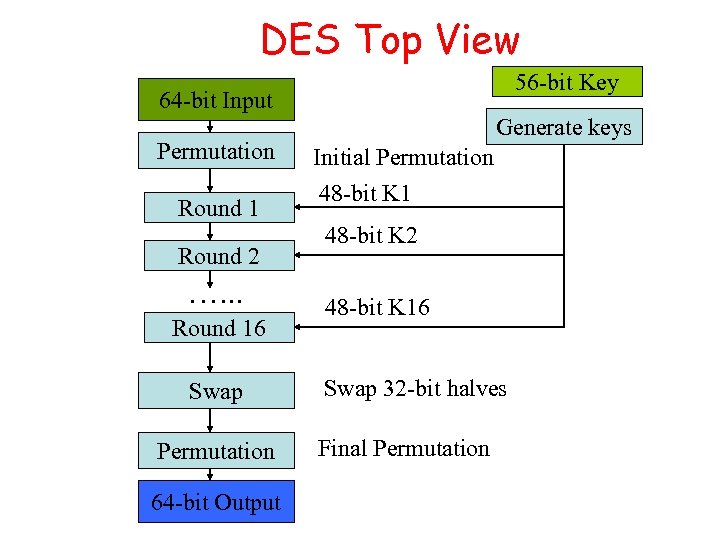

DES Top View 56 -bit Key 64 -bit Input 48 -bit K 1 Permutation Round 1 Round 2 …. . . Round 16 Swap Permutation 64 -bit Output Generate keys Initial Permutation 48 -bit K 1 48 -bit K 2 48 -bit K 16 Swap 32 -bit halves Final Permutation

DES Top View 56 -bit Key 64 -bit Input 48 -bit K 1 Permutation Round 1 Round 2 …. . . Round 16 Swap Permutation 64 -bit Output Generate keys Initial Permutation 48 -bit K 1 48 -bit K 2 48 -bit K 16 Swap 32 -bit halves Final Permutation

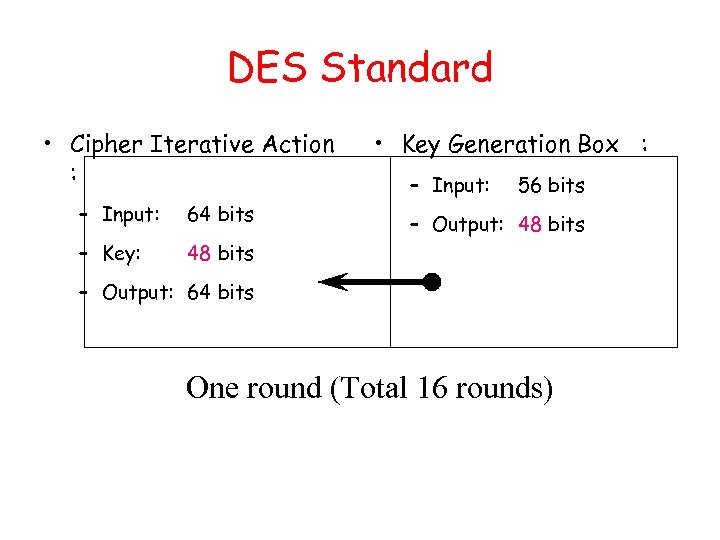

DES Standard • Cipher Iterative Action : – Input: 64 bits – Key: • Key Generation Box : – Input: 56 bits 48 bits – Output: 64 bits One round (Total 16 rounds)

DES Standard • Cipher Iterative Action : – Input: 64 bits – Key: • Key Generation Box : – Input: 56 bits 48 bits – Output: 64 bits One round (Total 16 rounds)

DES Box Summary • Simple, easy to implement: – Hardware/gigabits/second, software/megabits/second • 56 -bit key DES may be acceptable for noncritical applications but triple DES (DES 3) should be secure for most applications today • Supports several operation modes (ECB CBC, OFB, CFB) for different applications

DES Box Summary • Simple, easy to implement: – Hardware/gigabits/second, software/megabits/second • 56 -bit key DES may be acceptable for noncritical applications but triple DES (DES 3) should be secure for most applications today • Supports several operation modes (ECB CBC, OFB, CFB) for different applications

Avalanche Effect • Key desirable property of encryption alg • Where a change of one input or key bit results in changing more than half output bits • DES exhibits strong avalanche

Avalanche Effect • Key desirable property of encryption alg • Where a change of one input or key bit results in changing more than half output bits • DES exhibits strong avalanche

Strength of DES – Key Size • 56 -bit keys have 256 = 7. 2 x 1016 values • Brute force search looks hard • Recent advances have shown is possible – in 1997 on a huge cluster of computers over the Internet in a few months – in 1998 on dedicated hardware called “DES cracker” by EFF in a few days ($220, 000) – in 1999 above combined in 22 hrs! • Still must be able to recognize plaintext • No big flaw for DES algorithms

Strength of DES – Key Size • 56 -bit keys have 256 = 7. 2 x 1016 values • Brute force search looks hard • Recent advances have shown is possible – in 1997 on a huge cluster of computers over the Internet in a few months – in 1998 on dedicated hardware called “DES cracker” by EFF in a few days ($220, 000) – in 1999 above combined in 22 hrs! • Still must be able to recognize plaintext • No big flaw for DES algorithms

DES Replacement • Triple-DES (3 DES) – 168 -bit key, no brute force attacks – Underlying encryption algorithm the same, no effective analytic attacks – Drawbacks • Performance: no efficient software codes for DES/3 DES • Efficiency/security: bigger block size desirable • Advanced Encryption Standards (AES) – US NIST issued call for ciphers in 1997 – Rijndael was selected as the AES in Oct-2000

DES Replacement • Triple-DES (3 DES) – 168 -bit key, no brute force attacks – Underlying encryption algorithm the same, no effective analytic attacks – Drawbacks • Performance: no efficient software codes for DES/3 DES • Efficiency/security: bigger block size desirable • Advanced Encryption Standards (AES) – US NIST issued call for ciphers in 1997 – Rijndael was selected as the AES in Oct-2000

AES • Private key symmetric block cipher • 128 -bit data, 128/192/256 -bit keys • Stronger & faster than Triple-DES • Provide full specification & design details • Evaluation criteria – Security: effort to practically cryptanalysis – Cost: computational efficiency and memory requirement – Algorithm & implementation characteristics: flexibility to apps, hardware/software suitability, simplicity

AES • Private key symmetric block cipher • 128 -bit data, 128/192/256 -bit keys • Stronger & faster than Triple-DES • Provide full specification & design details • Evaluation criteria – Security: effort to practically cryptanalysis – Cost: computational efficiency and memory requirement – Algorithm & implementation characteristics: flexibility to apps, hardware/software suitability, simplicity

AES Shortlist • After testing and evaluation, shortlist in Aug-99: – MARS (IBM) - complex, fast, high security margin – RC 6 (USA) - v. simple, v. fast, low security margin – Rijndael (Belgium) - clean, fast, good security margin – Serpent (Euro) - slow, clean, v. high security margin – Twofish (USA) - complex, v. fast, high security margin • Then subject to further analysis & comment

AES Shortlist • After testing and evaluation, shortlist in Aug-99: – MARS (IBM) - complex, fast, high security margin – RC 6 (USA) - v. simple, v. fast, low security margin – Rijndael (Belgium) - clean, fast, good security margin – Serpent (Euro) - slow, clean, v. high security margin – Twofish (USA) - complex, v. fast, high security margin • Then subject to further analysis & comment

Outlines • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outlines • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Private-Key Cryptography • Private/secret/single key cryptography uses one key • Shared by both sender and receiver • If this key is disclosed communications are compromised • Also is symmetric, parties are equal • Hence does not protect sender from receiver forging a message & claiming is sent by sender

Private-Key Cryptography • Private/secret/single key cryptography uses one key • Shared by both sender and receiver • If this key is disclosed communications are compromised • Also is symmetric, parties are equal • Hence does not protect sender from receiver forging a message & claiming is sent by sender

Public-Key Cryptography • Probably most significant advance in the 3000 year history of cryptography • Uses two keys – a public & a private key • Asymmetric since parties are not equal • Uses clever application of number theoretic concepts to function • Complements rather than replaces private key crypto

Public-Key Cryptography • Probably most significant advance in the 3000 year history of cryptography • Uses two keys – a public & a private key • Asymmetric since parties are not equal • Uses clever application of number theoretic concepts to function • Complements rather than replaces private key crypto

Public-Key Cryptography • Public-key/two-key/asymmetric cryptography involves the use of two keys: – a public-key, which may be known by anybody, and can be used to encrypt messages, and verify signatures – a private-key, known only to the recipient, used to decrypt messages, and sign (create) signatures • Asymmetric because – those who encrypt messages or verify signatures cannot decrypt messages or create signatures

Public-Key Cryptography • Public-key/two-key/asymmetric cryptography involves the use of two keys: – a public-key, which may be known by anybody, and can be used to encrypt messages, and verify signatures – a private-key, known only to the recipient, used to decrypt messages, and sign (create) signatures • Asymmetric because – those who encrypt messages or verify signatures cannot decrypt messages or create signatures

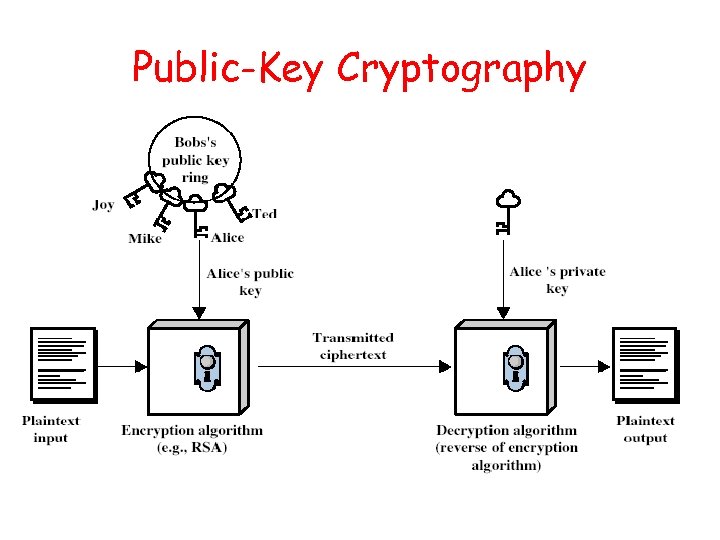

Public-Key Cryptography

Public-Key Cryptography

Public-Key Characteristics • Public-Key algorithms rely on two keys with the characteristics that it is: – computationally infeasible to find decryption key knowing only algorithm & encryption key – computationally easy to en/decrypt messages when the relevant (en/decrypt) key is known – either of the two related keys can be used for encryption, with the other used for decryption (in some schemes) • Analogy to delivery w/ a padlocked box

Public-Key Characteristics • Public-Key algorithms rely on two keys with the characteristics that it is: – computationally infeasible to find decryption key knowing only algorithm & encryption key – computationally easy to en/decrypt messages when the relevant (en/decrypt) key is known – either of the two related keys can be used for encryption, with the other used for decryption (in some schemes) • Analogy to delivery w/ a padlocked box

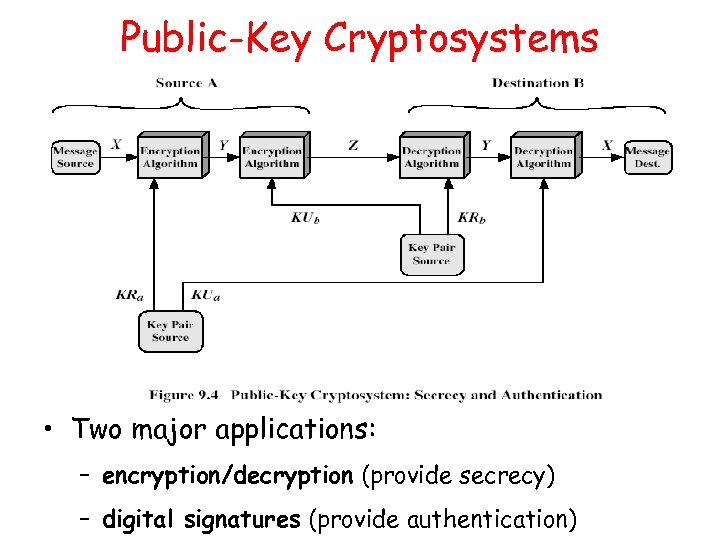

Public-Key Cryptosystems • Two major applications: – encryption/decryption (provide secrecy) – digital signatures (provide authentication)

Public-Key Cryptosystems • Two major applications: – encryption/decryption (provide secrecy) – digital signatures (provide authentication)

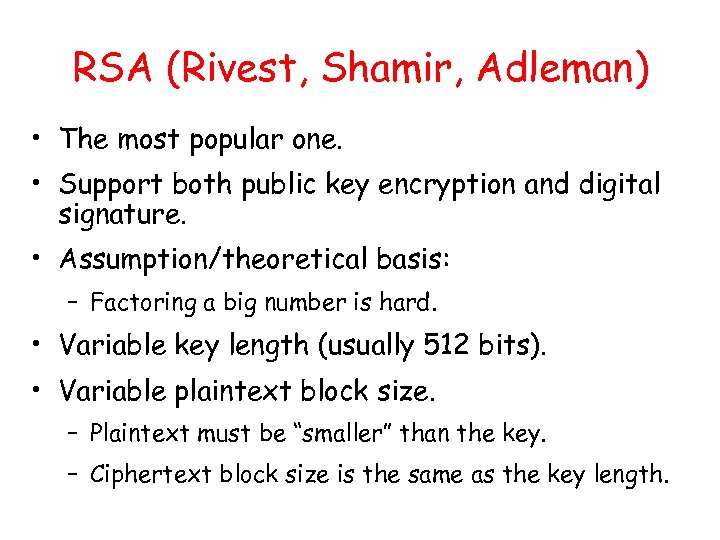

RSA (Rivest, Shamir, Adleman) • The most popular one. • Support both public key encryption and digital signature. • Assumption/theoretical basis: – Factoring a big number is hard. • Variable key length (usually 512 bits). • Variable plaintext block size. – Plaintext must be “smaller” than the key. – Ciphertext block size is the same as the key length.

RSA (Rivest, Shamir, Adleman) • The most popular one. • Support both public key encryption and digital signature. • Assumption/theoretical basis: – Factoring a big number is hard. • Variable key length (usually 512 bits). • Variable plaintext block size. – Plaintext must be “smaller” than the key. – Ciphertext block size is the same as the key length.

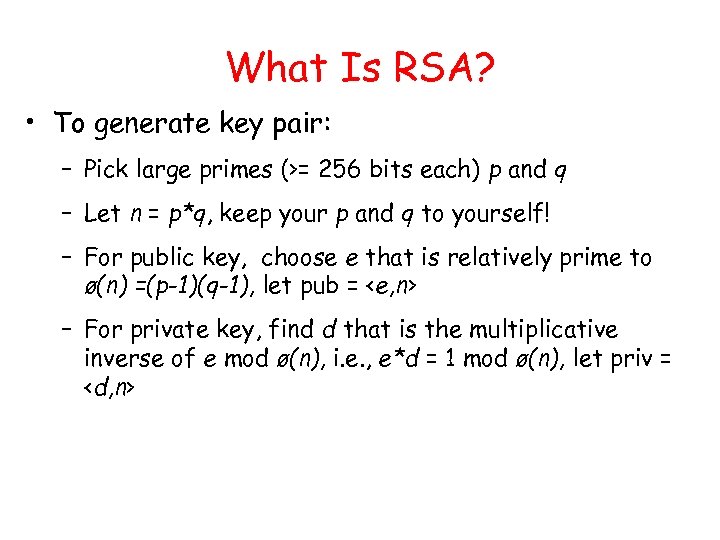

What Is RSA? • To generate key pair: – Pick large primes (>= 256 bits each) p and q – Let n = p*q, keep your p and q to yourself! – For public key, choose e that is relatively prime to ø(n) =(p-1)(q-1), let pub =

What Is RSA? • To generate key pair: – Pick large primes (>= 256 bits each) p and q – Let n = p*q, keep your p and q to yourself! – For public key, choose e that is relatively prime to ø(n) =(p-1)(q-1), let pub =

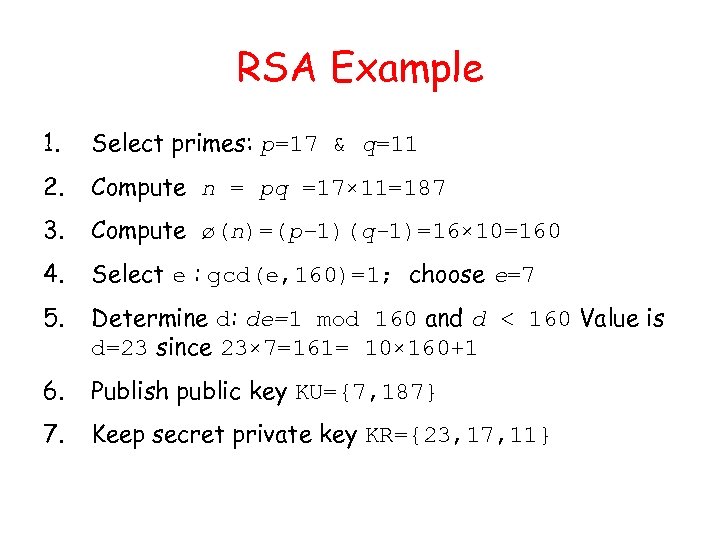

RSA Example 1. Select primes: p=17 & q=11 2. Compute n = pq =17× 11=187 3. Compute ø(n)=(p– 1)(q-1)=16× 10=160 4. Select e : gcd(e, 160)=1; choose e=7 5. Determine d: de=1 mod 160 and d < 160 Value is d=23 since 23× 7=161= 10× 160+1 6. Publish public key KU={7, 187} 7. Keep secret private key KR={23, 17, 11}

RSA Example 1. Select primes: p=17 & q=11 2. Compute n = pq =17× 11=187 3. Compute ø(n)=(p– 1)(q-1)=16× 10=160 4. Select e : gcd(e, 160)=1; choose e=7 5. Determine d: de=1 mod 160 and d < 160 Value is d=23 since 23× 7=161= 10× 160+1 6. Publish public key KU={7, 187} 7. Keep secret private key KR={23, 17, 11}

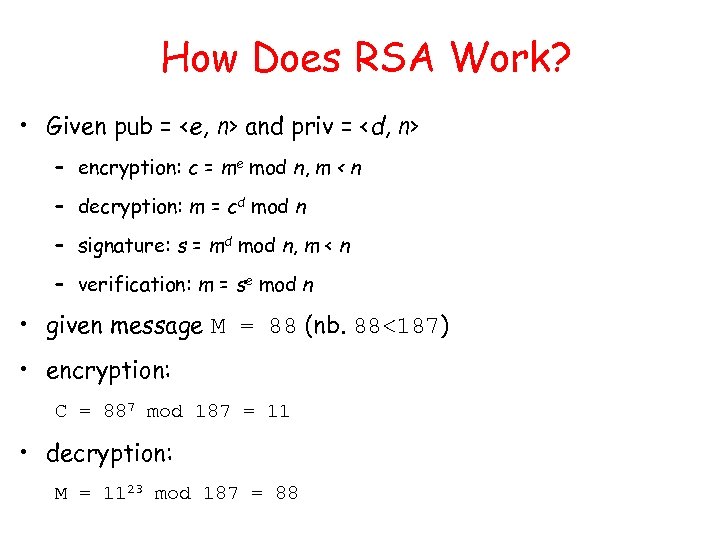

How Does RSA Work? • Given pub =

How Does RSA Work? • Given pub =

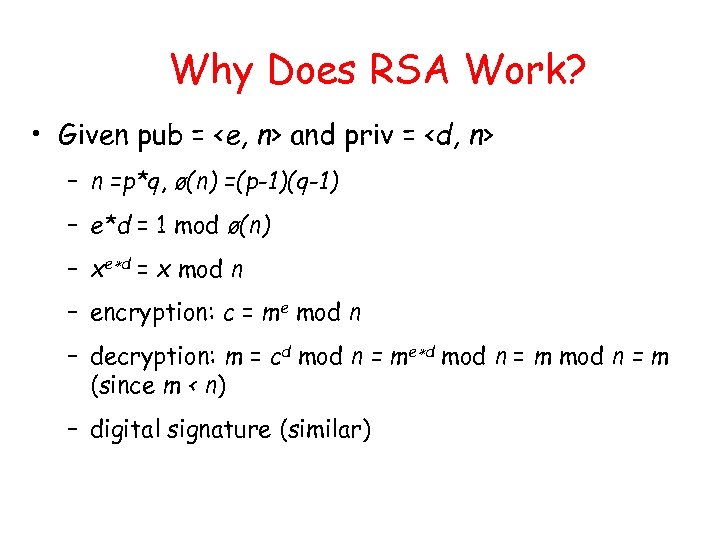

Why Does RSA Work? • Given pub =

Why Does RSA Work? • Given pub =

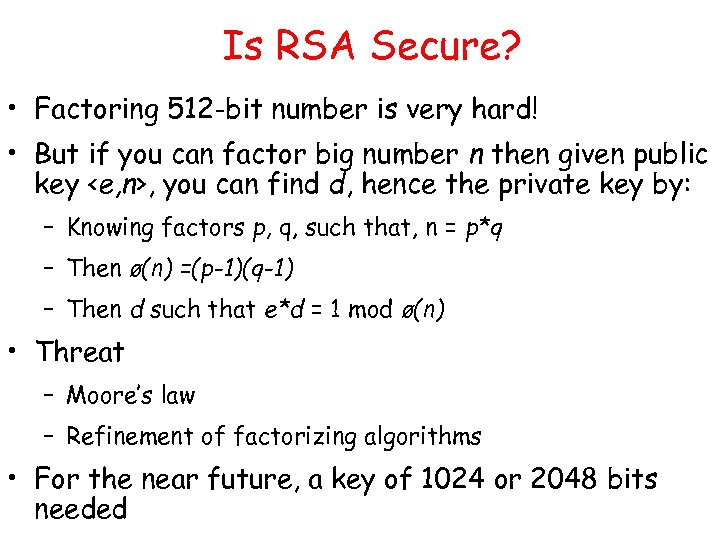

Is RSA Secure? • Factoring 512 -bit number is very hard! • But if you can factor big number n then given public key

Is RSA Secure? • Factoring 512 -bit number is very hard! • But if you can factor big number n then given public key

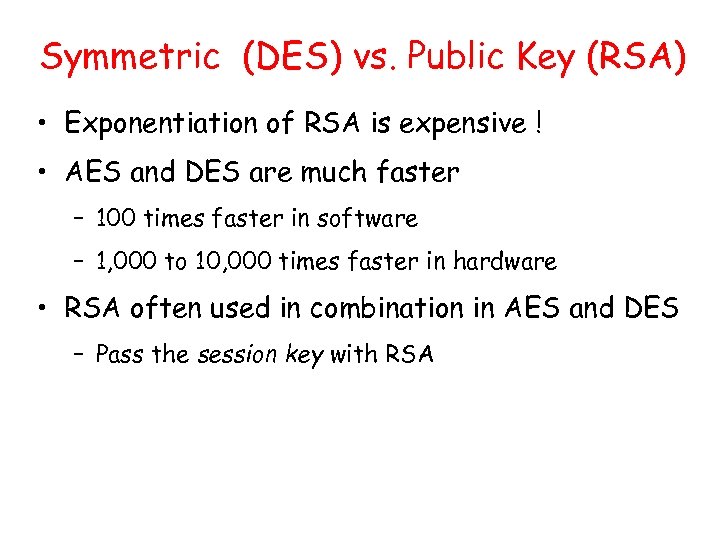

Symmetric (DES) vs. Public Key (RSA) • Exponentiation of RSA is expensive ! • AES and DES are much faster – 100 times faster in software – 1, 000 to 10, 000 times faster in hardware • RSA often used in combination in AES and DES – Pass the session key with RSA

Symmetric (DES) vs. Public Key (RSA) • Exponentiation of RSA is expensive ! • AES and DES are much faster – 100 times faster in software – 1, 000 to 10, 000 times faster in hardware • RSA often used in combination in AES and DES – Pass the session key with RSA

Outline • History of Security and Definitions • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Outline • History of Security and Definitions • Overview of Cryptography • Symmetric Cipher – Classical Symmetric Cipher – Modern Symmetric Ciphers (DES and AES) • Asymmetric Cipher • One-way Hash Functions and Message Digest

Confidentiality => Authenticity ? • Symmetric cipher ? – Plaintext has to be intelligible/understandable • Asymmetric cipher? – Straightforward use provides no authenticity – Coupled encryption • Too expensive • Requires intelligible text, otherwise message size doubles

Confidentiality => Authenticity ? • Symmetric cipher ? – Plaintext has to be intelligible/understandable • Asymmetric cipher? – Straightforward use provides no authenticity – Coupled encryption • Too expensive • Requires intelligible text, otherwise message size doubles

Hash Functions • Condenses arbitrary message to fixed size h = H(M) • Usually assume that the hash function is public and not keyed • Hash used to detect changes to message • Can use in various ways with message • Most often to create a digital signature

Hash Functions • Condenses arbitrary message to fixed size h = H(M) • Usually assume that the hash function is public and not keyed • Hash used to detect changes to message • Can use in various ways with message • Most often to create a digital signature

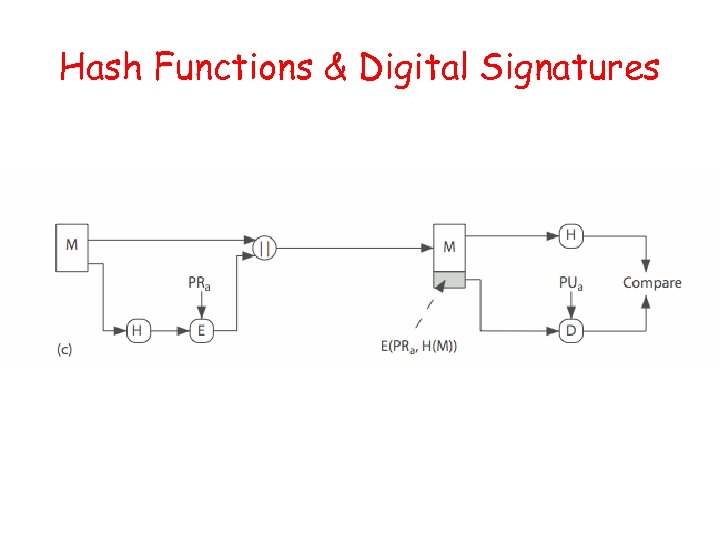

Hash Functions & Digital Signatures

Hash Functions & Digital Signatures

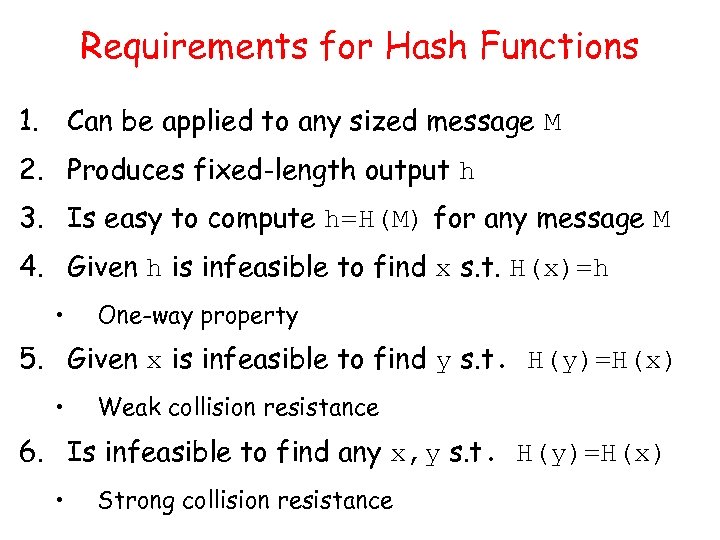

Requirements for Hash Functions 1. Can be applied to any sized message M 2. Produces fixed-length output h 3. Is easy to compute h=H(M) for any message M 4. Given h is infeasible to find x s. t. H(x)=h • One-way property 5. Given x is infeasible to find y s. t. H(y)=H(x) • Weak collision resistance 6. Is infeasible to find any x, y s. t. H(y)=H(x) • Strong collision resistance

Requirements for Hash Functions 1. Can be applied to any sized message M 2. Produces fixed-length output h 3. Is easy to compute h=H(M) for any message M 4. Given h is infeasible to find x s. t. H(x)=h • One-way property 5. Given x is infeasible to find y s. t. H(y)=H(x) • Weak collision resistance 6. Is infeasible to find any x, y s. t. H(y)=H(x) • Strong collision resistance

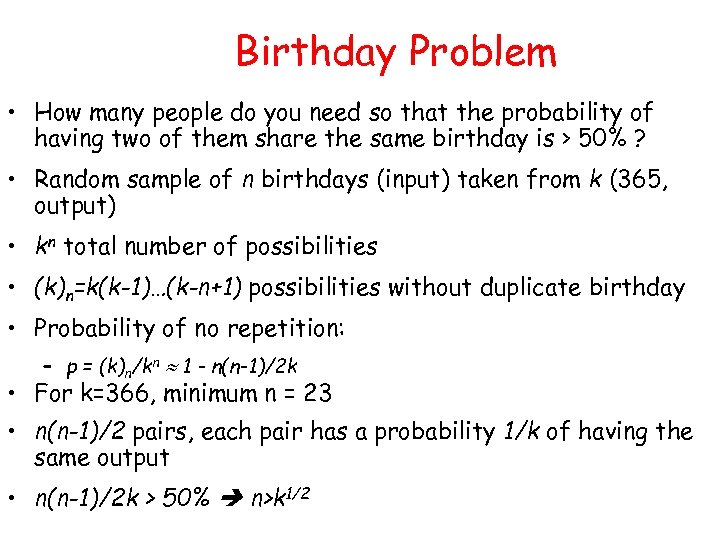

Birthday Problem • How many people do you need so that the probability of having two of them share the same birthday is > 50% ? • Random sample of n birthdays (input) taken from k (365, output) • kn total number of possibilities • (k)n=k(k-1)…(k-n+1) possibilities without duplicate birthday • Probability of no repetition: – p = (k)n/kn 1 - n(n-1)/2 k • For k=366, minimum n = 23 • n(n-1)/2 pairs, each pair has a probability 1/k of having the same output • n(n-1)/2 k > 50% n>k 1/2

Birthday Problem • How many people do you need so that the probability of having two of them share the same birthday is > 50% ? • Random sample of n birthdays (input) taken from k (365, output) • kn total number of possibilities • (k)n=k(k-1)…(k-n+1) possibilities without duplicate birthday • Probability of no repetition: – p = (k)n/kn 1 - n(n-1)/2 k • For k=366, minimum n = 23 • n(n-1)/2 pairs, each pair has a probability 1/k of having the same output • n(n-1)/2 k > 50% n>k 1/2

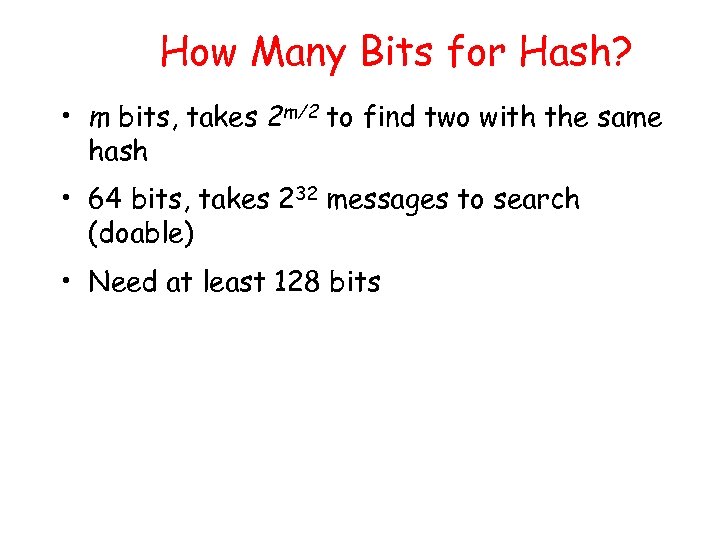

How Many Bits for Hash? • m bits, takes 2 m/2 to find two with the same hash • 64 bits, takes 232 messages to search (doable) • Need at least 128 bits

How Many Bits for Hash? • m bits, takes 2 m/2 to find two with the same hash • 64 bits, takes 232 messages to search (doable) • Need at least 128 bits

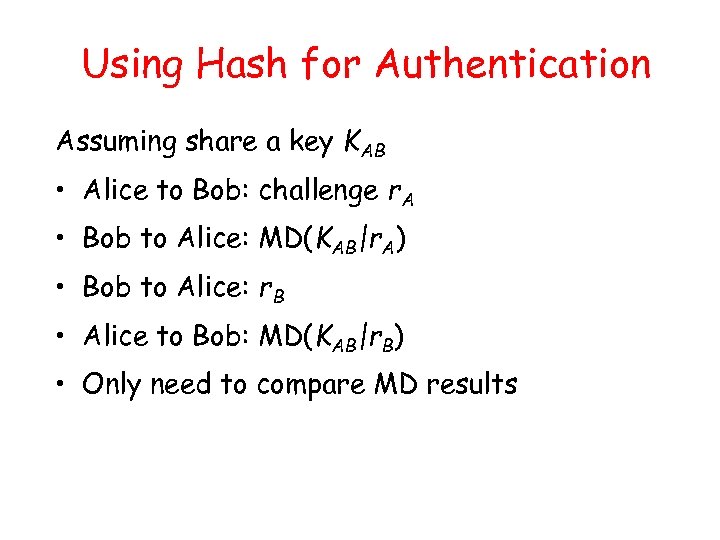

Using Hash for Authentication Assuming share a key KAB • Alice to Bob: challenge r. A • Bob to Alice: MD(KAB|r. A) • Bob to Alice: r. B • Alice to Bob: MD(KAB|r. B) • Only need to compare MD results

Using Hash for Authentication Assuming share a key KAB • Alice to Bob: challenge r. A • Bob to Alice: MD(KAB|r. A) • Bob to Alice: r. B • Alice to Bob: MD(KAB|r. B) • Only need to compare MD results

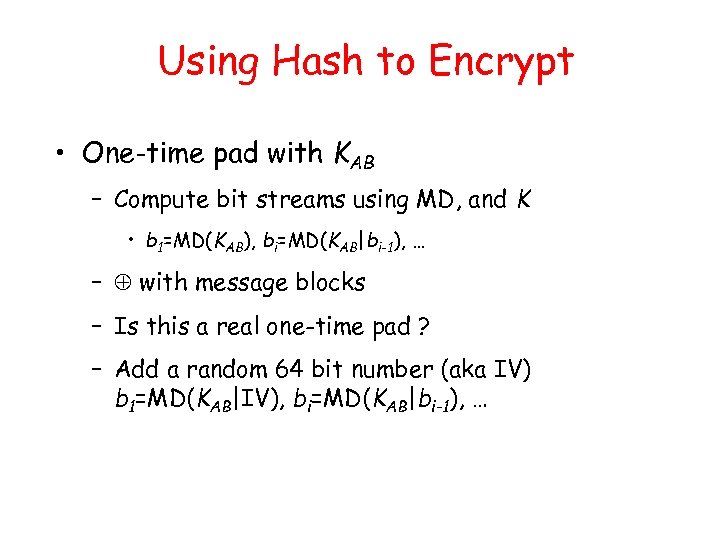

Using Hash to Encrypt • One-time pad with KAB – Compute bit streams using MD, and K • b 1=MD(KAB), bi=MD(KAB|bi-1), … – with message blocks – Is this a real one-time pad ? – Add a random 64 bit number (aka IV) b 1=MD(KAB|IV), bi=MD(KAB|bi-1), …

Using Hash to Encrypt • One-time pad with KAB – Compute bit streams using MD, and K • b 1=MD(KAB), bi=MD(KAB|bi-1), … – with message blocks – Is this a real one-time pad ? – Add a random 64 bit number (aka IV) b 1=MD(KAB|IV), bi=MD(KAB|bi-1), …

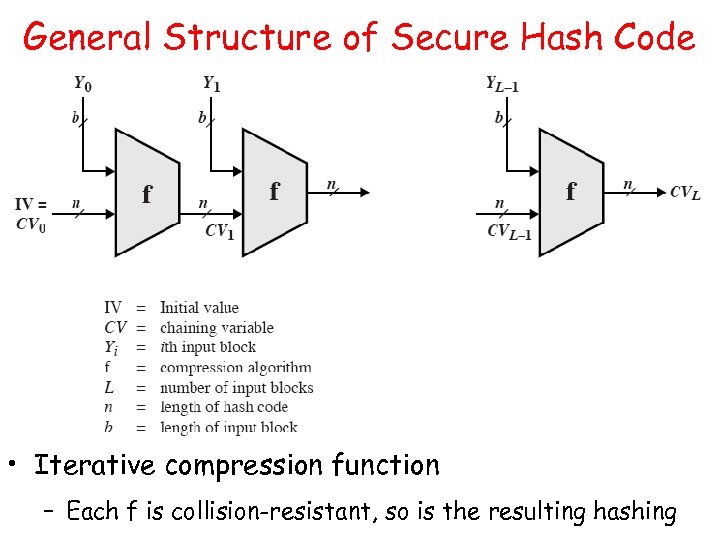

General Structure of Secure Hash Code • Iterative compression function – Each f is collision-resistant, so is the resulting hashing

General Structure of Secure Hash Code • Iterative compression function – Each f is collision-resistant, so is the resulting hashing

MD 5: Message Digest Version 5 input Message Output 128 bits Digest • Until recently the most widely used hash algorithm – in recent times have both brute-force & cryptanalytic concerns • Specified as Internet standard RFC 1321

MD 5: Message Digest Version 5 input Message Output 128 bits Digest • Until recently the most widely used hash algorithm – in recent times have both brute-force & cryptanalytic concerns • Specified as Internet standard RFC 1321

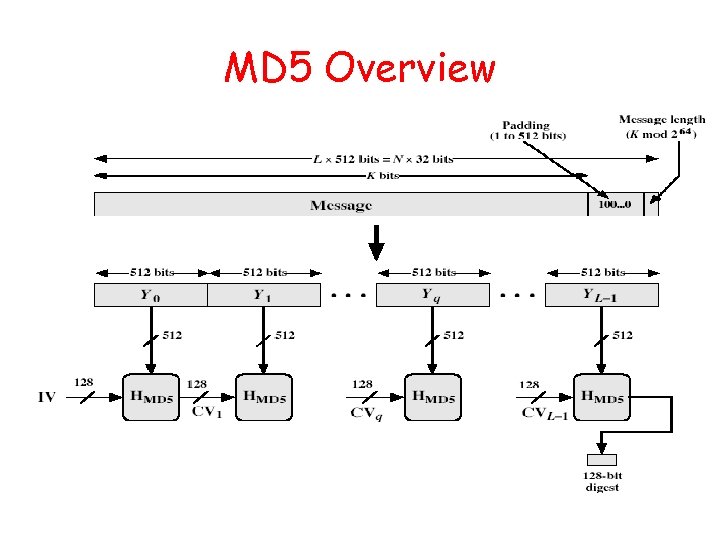

MD 5 Overview

MD 5 Overview

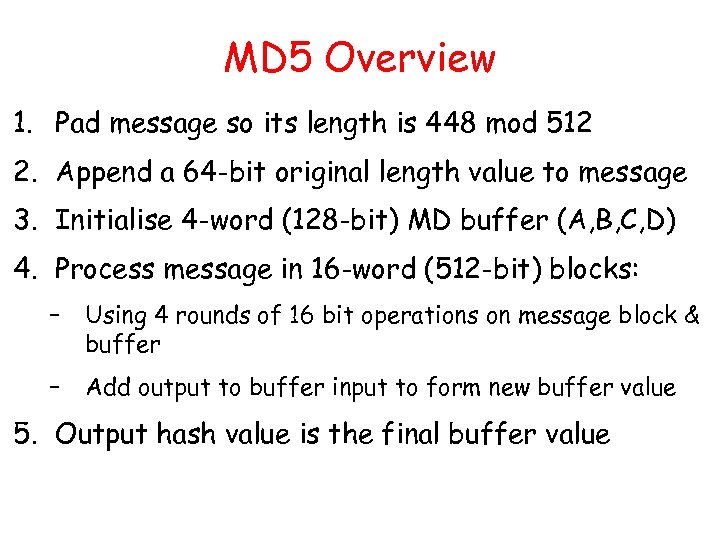

MD 5 Overview 1. Pad message so its length is 448 mod 512 2. Append a 64 -bit original length value to message 3. Initialise 4 -word (128 -bit) MD buffer (A, B, C, D) 4. Process message in 16 -word (512 -bit) blocks: – Using 4 rounds of 16 bit operations on message block & buffer – Add output to buffer input to form new buffer value 5. Output hash value is the final buffer value

MD 5 Overview 1. Pad message so its length is 448 mod 512 2. Append a 64 -bit original length value to message 3. Initialise 4 -word (128 -bit) MD buffer (A, B, C, D) 4. Process message in 16 -word (512 -bit) blocks: – Using 4 rounds of 16 bit operations on message block & buffer – Add output to buffer input to form new buffer value 5. Output hash value is the final buffer value

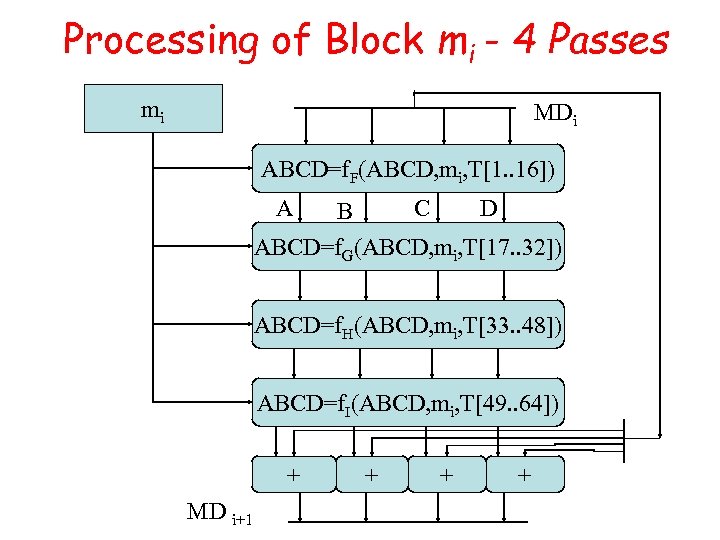

Processing of Block mi - 4 Passes mi MDi ABCD=f. F(ABCD, mi, T[1. . 16]) A C B D ABCD=f. G(ABCD, mi, T[17. . 32]) ABCD=f. H(ABCD, mi, T[33. . 48]) ABCD=f. I(ABCD, mi, T[49. . 64]) + MD i+1 + + +

Processing of Block mi - 4 Passes mi MDi ABCD=f. F(ABCD, mi, T[1. . 16]) A C B D ABCD=f. G(ABCD, mi, T[17. . 32]) ABCD=f. H(ABCD, mi, T[33. . 48]) ABCD=f. I(ABCD, mi, T[49. . 64]) + MD i+1 + + +

Secure Hash Algorithm • Developed by NIST, specified in the Secure Hash Standard (SHS, FIPS Pub 180), 1993 • SHA is specified as the hash algorithm in the Digital Signature Standard (DSS), NIST

Secure Hash Algorithm • Developed by NIST, specified in the Secure Hash Standard (SHS, FIPS Pub 180), 1993 • SHA is specified as the hash algorithm in the Digital Signature Standard (DSS), NIST

General Logic • Input message must be < 264 bits – not really a problem • Message is processed in 512 -bit blocks sequentially • Message digest is 160 bits • SHA design is similar to MD 5, a little slower, but a lot stronger

General Logic • Input message must be < 264 bits – not really a problem • Message is processed in 512 -bit blocks sequentially • Message digest is 160 bits • SHA design is similar to MD 5, a little slower, but a lot stronger

SHA-1 verses MD 5 • Brute force attack is harder (160 vs 128 bits for MD 5) • A little slower than MD 5 (80 vs 64 steps) – Both work well on a 32 -bit architecture • Both designed as simple and compact for implementation • Cryptanalytic attacks – MD 4/5: vulnerability discovered since its design – SHA-1: no until recent 2005 results raised concerns on its use in future applications

SHA-1 verses MD 5 • Brute force attack is harder (160 vs 128 bits for MD 5) • A little slower than MD 5 (80 vs 64 steps) – Both work well on a 32 -bit architecture • Both designed as simple and compact for implementation • Cryptanalytic attacks – MD 4/5: vulnerability discovered since its design – SHA-1: no until recent 2005 results raised concerns on its use in future applications

Revised Secure Hash Standard • NIST have issued a revision FIPS 180 -2 in 2002 • Adds 3 additional hash algorithms • SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512 – Collectively called SHA-2 • Designed for compatibility with increased security provided by the AES cipher • Structure & detail are similar to SHA-1 • Hence analysis should be similar, but security levels are rather higher

Revised Secure Hash Standard • NIST have issued a revision FIPS 180 -2 in 2002 • Adds 3 additional hash algorithms • SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512 – Collectively called SHA-2 • Designed for compatibility with increased security provided by the AES cipher • Structure & detail are similar to SHA-1 • Hence analysis should be similar, but security levels are rather higher

Backup Slides

Backup Slides

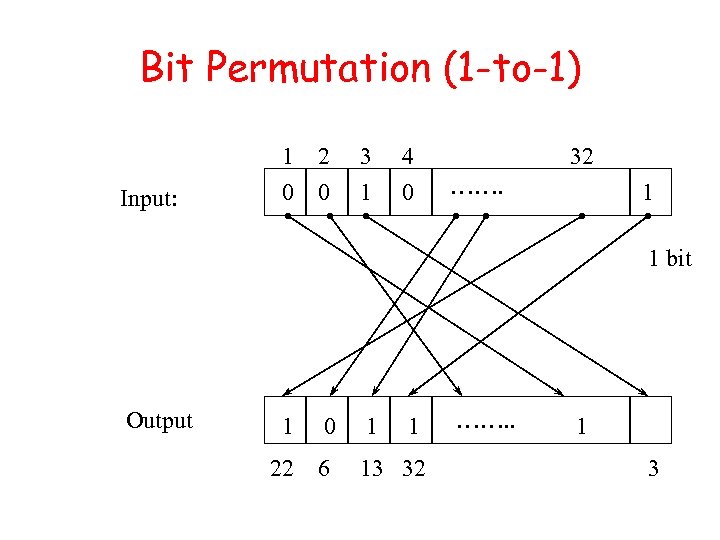

Bit Permutation (1 -to-1) Input: 1 2 0 0 3 1 4 0 32 ……. 1 1 bit Output 1 0 1 1 22 6 13 32 ……. . 1 3

Bit Permutation (1 -to-1) Input: 1 2 0 0 3 1 4 0 32 ……. 1 1 bit Output 1 0 1 1 22 6 13 32 ……. . 1 3

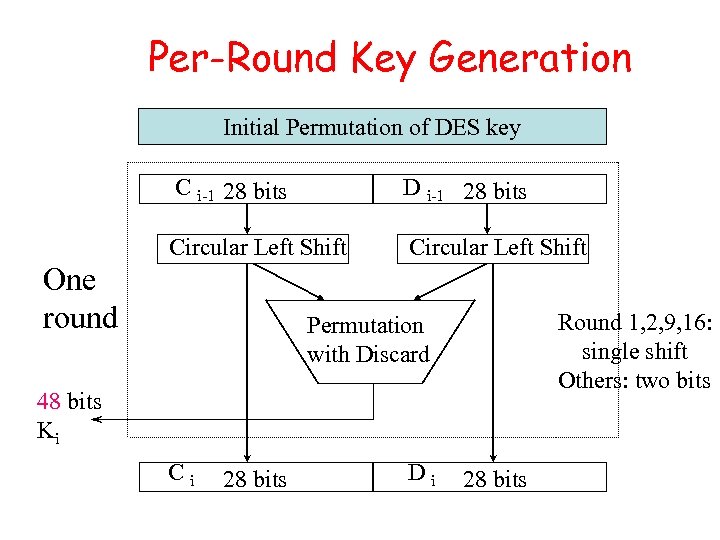

Per-Round Key Generation Initial Permutation of DES key C i-1 28 bits D i-1 28 bits Circular Left Shift One round Round 1, 2, 9, 16: single shift Others: two bits Permutation with Discard 48 bits Ki Ci 28 bits Di 28 bits

Per-Round Key Generation Initial Permutation of DES key C i-1 28 bits D i-1 28 bits Circular Left Shift One round Round 1, 2, 9, 16: single shift Others: two bits Permutation with Discard 48 bits Ki Ci 28 bits Di 28 bits

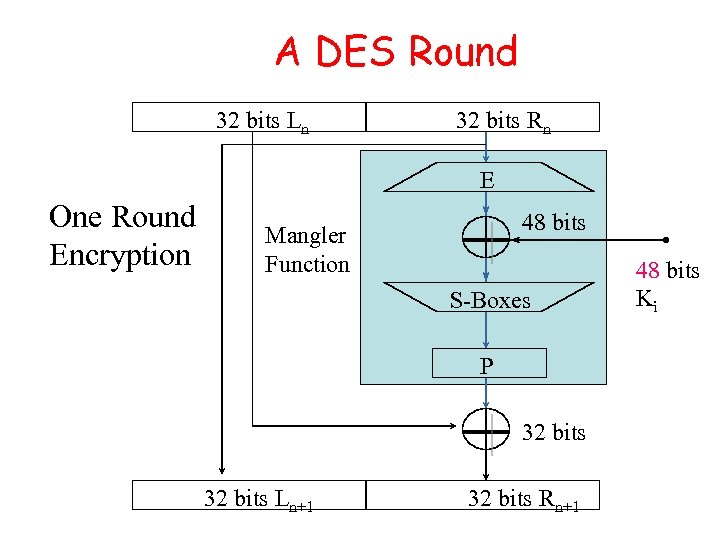

A DES Round 32 bits Ln 32 bits Rn E One Round Encryption 48 bits Mangler Function S-Boxes P 32 bits Ln+1 32 bits Rn+1 48 bits Ki

A DES Round 32 bits Ln 32 bits Rn E One Round Encryption 48 bits Mangler Function S-Boxes P 32 bits Ln+1 32 bits Rn+1 48 bits Ki

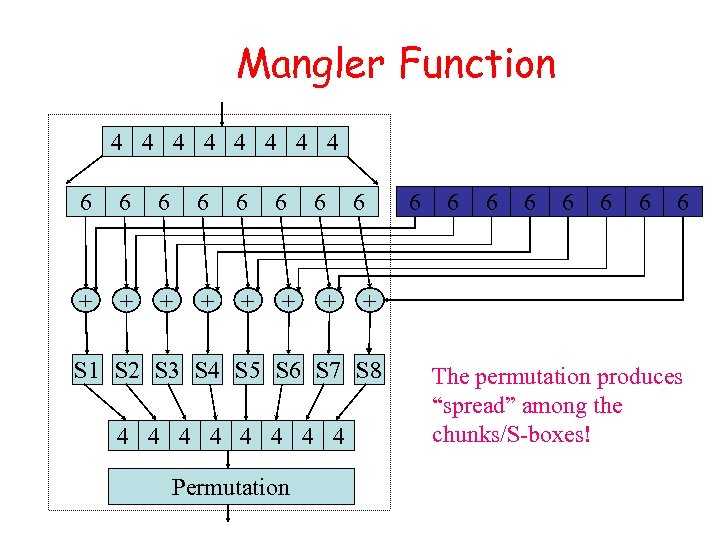

Mangler Function 4 4 4 4 6 6 6 + + + 6 + 6 Permutation 6 6 6 6 + S 1 S 2 S 3 S 4 S 5 S 6 S 7 S 8 4 4 4 4 6 The permutation produces “spread” among the chunks/S-boxes!

Mangler Function 4 4 4 4 6 6 6 + + + 6 + 6 Permutation 6 6 6 6 + S 1 S 2 S 3 S 4 S 5 S 6 S 7 S 8 4 4 4 4 6 The permutation produces “spread” among the chunks/S-boxes!

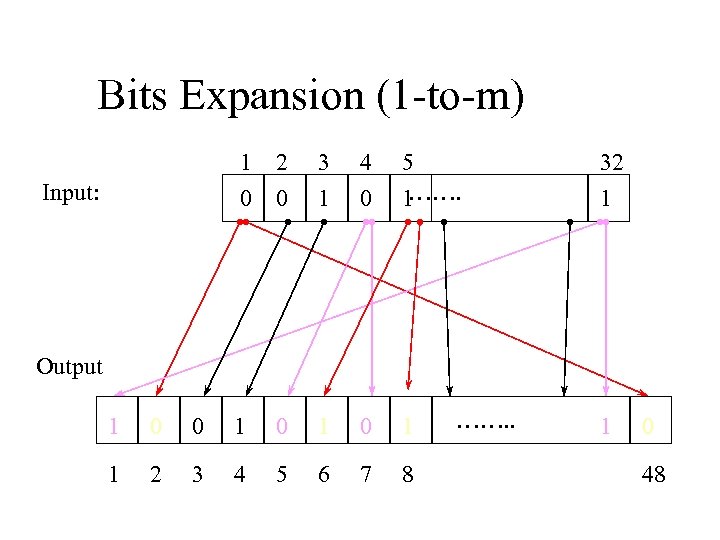

Bits Expansion (1 -to-m) 1 0 Input: 2 0 3 1 4 0 5 ……. 1 32 1 Output 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ……. . 1 0 48

Bits Expansion (1 -to-m) 1 0 Input: 2 0 3 1 4 0 5 ……. 1 32 1 Output 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ……. . 1 0 48

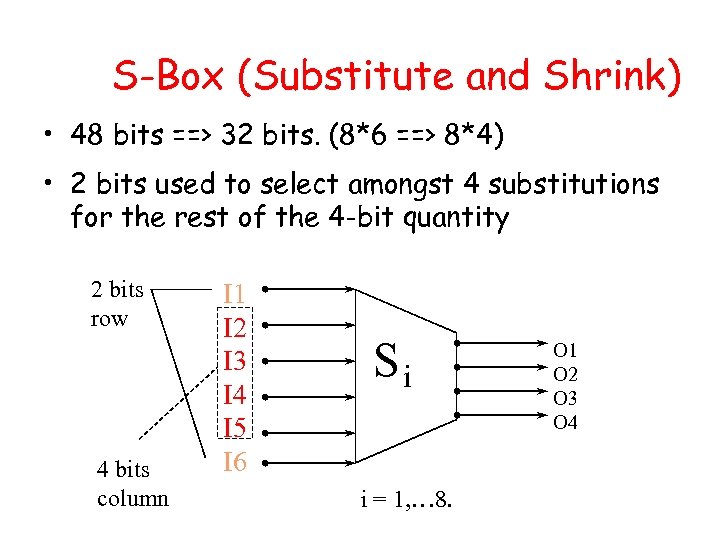

S-Box (Substitute and Shrink) • 48 bits ==> 32 bits. (8*6 ==> 8*4) • 2 bits used to select amongst 4 substitutions for the rest of the 4 -bit quantity 2 bits row 4 bits column I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 I 5 I 6 Si i = 1, … 8. O 1 O 2 O 3 O 4

S-Box (Substitute and Shrink) • 48 bits ==> 32 bits. (8*6 ==> 8*4) • 2 bits used to select amongst 4 substitutions for the rest of the 4 -bit quantity 2 bits row 4 bits column I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 I 5 I 6 Si i = 1, … 8. O 1 O 2 O 3 O 4

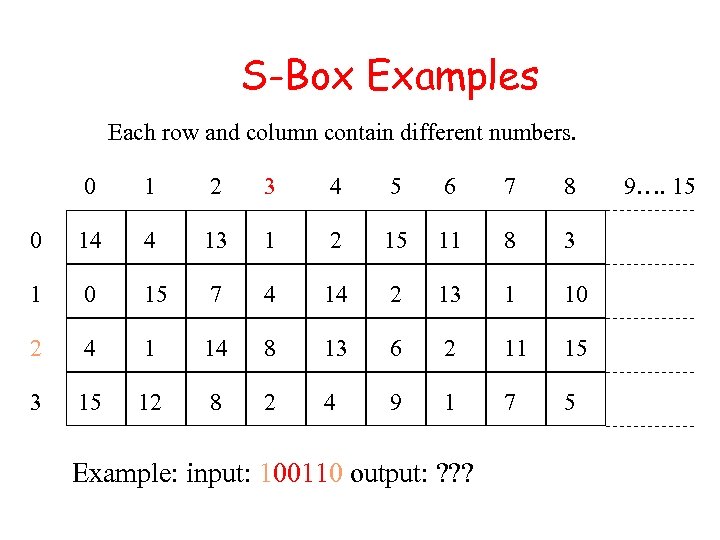

S-Box Examples Each row and column contain different numbers. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0 14 4 13 1 2 15 11 8 3 1 0 15 7 4 14 2 13 1 10 2 4 1 14 8 13 6 2 11 15 3 15 12 8 2 4 9 1 7 5 Example: input: 100110 output: ? ? ? 9…. 15

S-Box Examples Each row and column contain different numbers. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 0 14 4 13 1 2 15 11 8 3 1 0 15 7 4 14 2 13 1 10 2 4 1 14 8 13 6 2 11 15 3 15 12 8 2 4 9 1 7 5 Example: input: 100110 output: ? ? ? 9…. 15

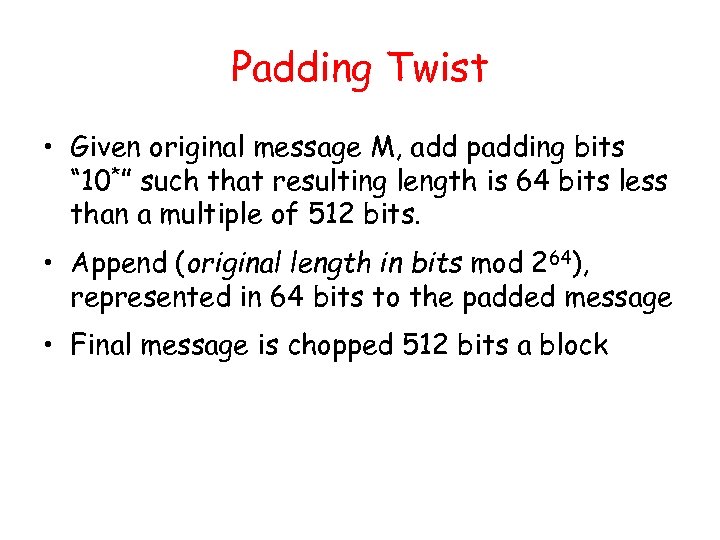

Padding Twist • Given original message M, add padding bits “ 10*” such that resulting length is 64 bits less than a multiple of 512 bits. • Append (original length in bits mod 264), represented in 64 bits to the padded message • Final message is chopped 512 bits a block

Padding Twist • Given original message M, add padding bits “ 10*” such that resulting length is 64 bits less than a multiple of 512 bits. • Append (original length in bits mod 264), represented in 64 bits to the padded message • Final message is chopped 512 bits a block

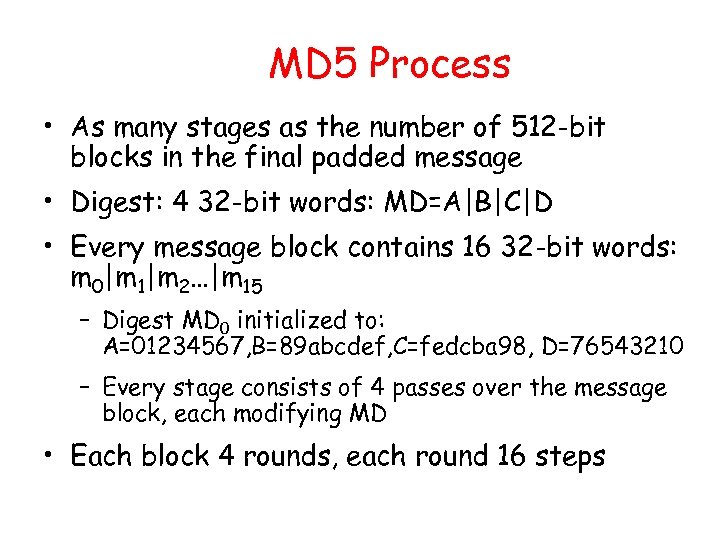

MD 5 Process • As many stages as the number of 512 -bit blocks in the final padded message • Digest: 4 32 -bit words: MD=A|B|C|D • Every message block contains 16 32 -bit words: m 0|m 1|m 2…|m 15 – Digest MD 0 initialized to: A=01234567, B=89 abcdef, C=fedcba 98, D=76543210 – Every stage consists of 4 passes over the message block, each modifying MD • Each block 4 rounds, each round 16 steps

MD 5 Process • As many stages as the number of 512 -bit blocks in the final padded message • Digest: 4 32 -bit words: MD=A|B|C|D • Every message block contains 16 32 -bit words: m 0|m 1|m 2…|m 15 – Digest MD 0 initialized to: A=01234567, B=89 abcdef, C=fedcba 98, D=76543210 – Every stage consists of 4 passes over the message block, each modifying MD • Each block 4 rounds, each round 16 steps

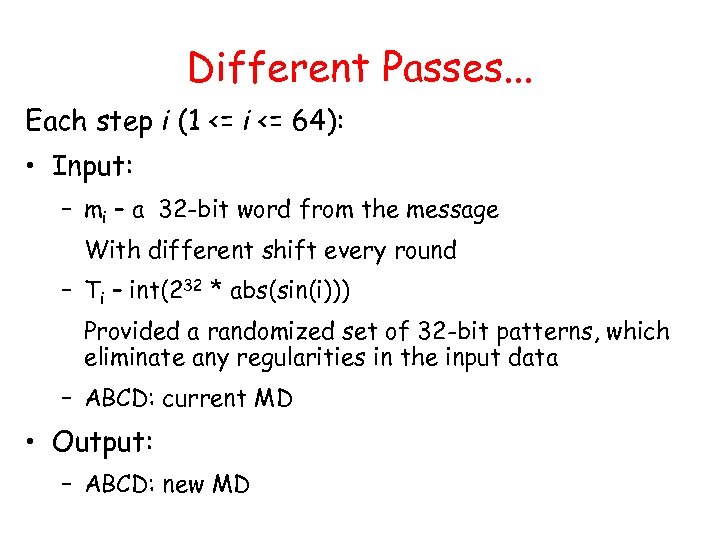

Different Passes. . . Each step i (1 <= i <= 64): • Input: – mi – a 32 -bit word from the message With different shift every round – Ti – int(232 * abs(sin(i))) Provided a randomized set of 32 -bit patterns, which eliminate any regularities in the input data – ABCD: current MD • Output: – ABCD: new MD

Different Passes. . . Each step i (1 <= i <= 64): • Input: – mi – a 32 -bit word from the message With different shift every round – Ti – int(232 * abs(sin(i))) Provided a randomized set of 32 -bit patterns, which eliminate any regularities in the input data – ABCD: current MD • Output: – ABCD: new MD

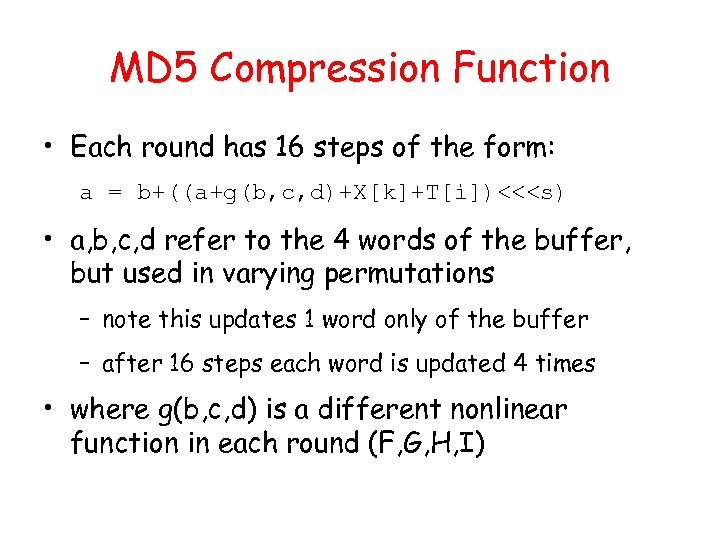

MD 5 Compression Function • Each round has 16 steps of the form: a = b+((a+g(b, c, d)+X[k]+T[i])<<

MD 5 Compression Function • Each round has 16 steps of the form: a = b+((a+g(b, c, d)+X[k]+T[i])<<

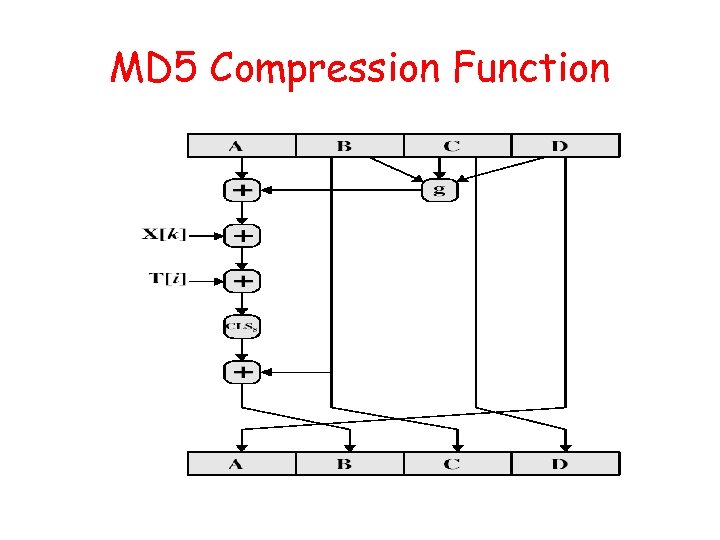

MD 5 Compression Function

MD 5 Compression Function

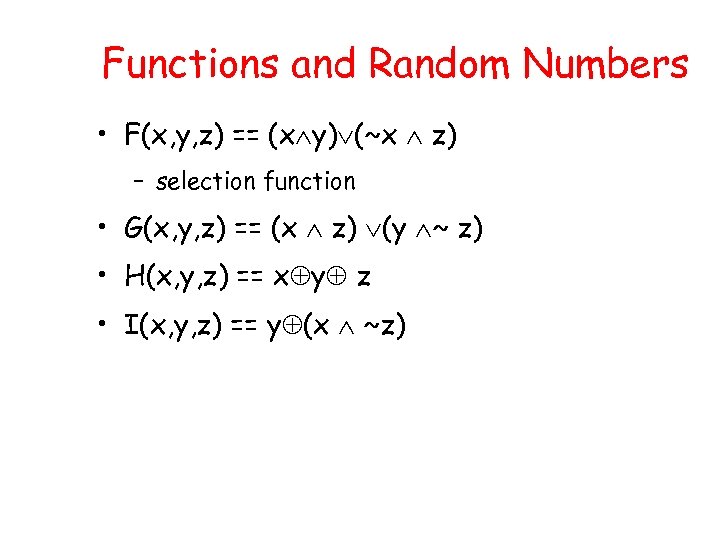

Functions and Random Numbers • F(x, y, z) == (x y) (~x z) – selection function • G(x, y, z) == (x z) (y ~ z) • H(x, y, z) == x y z • I(x, y, z) == y (x ~z)

Functions and Random Numbers • F(x, y, z) == (x y) (~x z) – selection function • G(x, y, z) == (x z) (y ~ z) • H(x, y, z) == x y z • I(x, y, z) == y (x ~z)

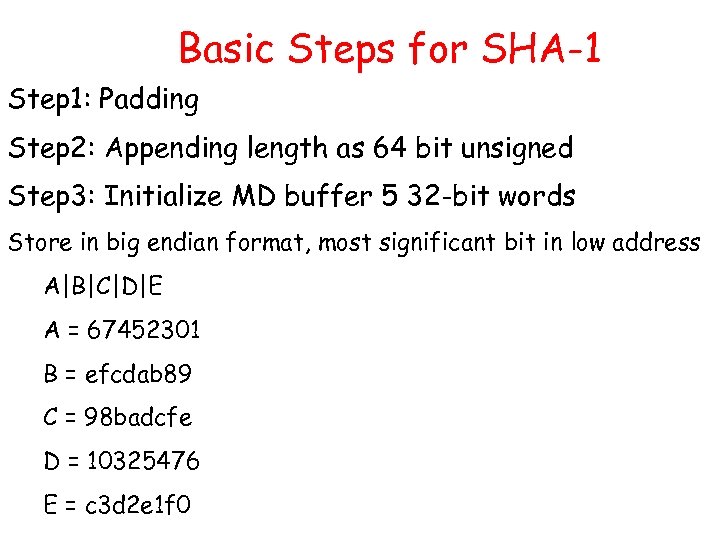

Basic Steps for SHA-1 Step 1: Padding Step 2: Appending length as 64 bit unsigned Step 3: Initialize MD buffer 5 32 -bit words Store in big endian format, most significant bit in low address A|B|C|D|E A = 67452301 B = efcdab 89 C = 98 badcfe D = 10325476 E = c 3 d 2 e 1 f 0

Basic Steps for SHA-1 Step 1: Padding Step 2: Appending length as 64 bit unsigned Step 3: Initialize MD buffer 5 32 -bit words Store in big endian format, most significant bit in low address A|B|C|D|E A = 67452301 B = efcdab 89 C = 98 badcfe D = 10325476 E = c 3 d 2 e 1 f 0

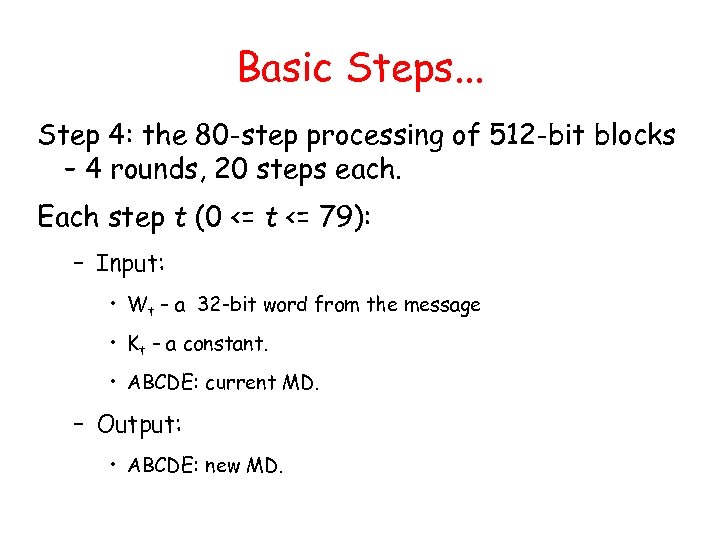

Basic Steps. . . Step 4: the 80 -step processing of 512 -bit blocks – 4 rounds, 20 steps each. Each step t (0 <= t <= 79): – Input: • Wt – a 32 -bit word from the message • Kt – a constant. • ABCDE: current MD. – Output: • ABCDE: new MD.

Basic Steps. . . Step 4: the 80 -step processing of 512 -bit blocks – 4 rounds, 20 steps each. Each step t (0 <= t <= 79): – Input: • Wt – a 32 -bit word from the message • Kt – a constant. • ABCDE: current MD. – Output: • ABCDE: new MD.