53bf7f1ad97df29f6aa505f46c50714f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 22

“Where did I park my car? ” How do Older Adults Cope with a Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment Alison Mc. Kinlay, Janet Leathem, Paul Merrick A. R. Mc. Kinlay@massey. ac. nz Joint NZCCP and NZPs. S Conference April 2012, Wellington, New Zealand

“Where did I park my car? ” How do Older Adults Cope with a Diagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment Alison Mc. Kinlay, Janet Leathem, Paul Merrick A. R. Mc. Kinlay@massey. ac. nz Joint NZCCP and NZPs. S Conference April 2012, Wellington, New Zealand

Objectives for Pe. Ar. LS Session To outline: › The literature on older adults and cognitive impairment. › Issues in the literature on these topics. › Research on coping with cognitive impairment. To describe the research plan in its current form. To open a discussion about the project. It is hoped that comments during this session will ensure that this research is of maximum benefit to key stakeholders: › Clients with MCI and their families › Practitioners in the field › Future researchers

Objectives for Pe. Ar. LS Session To outline: › The literature on older adults and cognitive impairment. › Issues in the literature on these topics. › Research on coping with cognitive impairment. To describe the research plan in its current form. To open a discussion about the project. It is hoped that comments during this session will ensure that this research is of maximum benefit to key stakeholders: › Clients with MCI and their families › Practitioners in the field › Future researchers

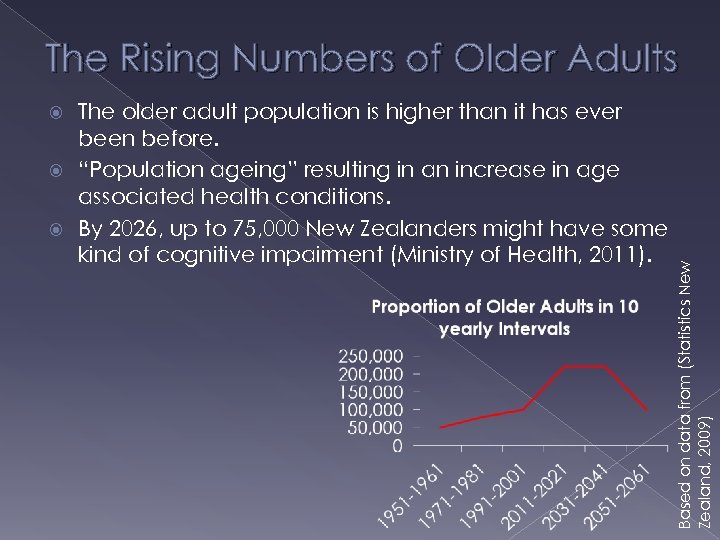

The Rising Numbers of Older Adults The older adult population is higher than it has ever been before. “Population ageing” resulting in an increase in age associated health conditions. By 2026, up to 75, 000 New Zealanders might have some kind of cognitive impairment (Ministry of Health, 2011). Based on data from (Statistics New Zealand, 2009)

The Rising Numbers of Older Adults The older adult population is higher than it has ever been before. “Population ageing” resulting in an increase in age associated health conditions. By 2026, up to 75, 000 New Zealanders might have some kind of cognitive impairment (Ministry of Health, 2011). Based on data from (Statistics New Zealand, 2009)

Dementia is a progressive neurological disorder. Typically occurs in adults over 65. Symptoms include: › › › Memory difficulties Problem solving difficulties Agnosia Apraxia Difficulties with social and occupational functioning Results in: › Disruption of everyday functional activities › Mortality High prevalence of comorbid conditions: › › Depression Delirium Mania Delusions

Dementia is a progressive neurological disorder. Typically occurs in adults over 65. Symptoms include: › › › Memory difficulties Problem solving difficulties Agnosia Apraxia Difficulties with social and occupational functioning Results in: › Disruption of everyday functional activities › Mortality High prevalence of comorbid conditions: › › Depression Delirium Mania Delusions

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) MCI is a transitional phase between normal ageing and dementia. › Approximately 10% annual conversion rate to dementia but this does not always occur. People with MCI typically experience objective memory complaints, but everyday functioning is still preserved. Usually occurs in adults over 65 Chances of developing cognitive impairment increase with age. Much debate in the literature about MCI Definition – Numerous terms used in research Criteria – Differing criteria (Morris, 2012)

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) MCI is a transitional phase between normal ageing and dementia. › Approximately 10% annual conversion rate to dementia but this does not always occur. People with MCI typically experience objective memory complaints, but everyday functioning is still preserved. Usually occurs in adults over 65 Chances of developing cognitive impairment increase with age. Much debate in the literature about MCI Definition – Numerous terms used in research Criteria – Differing criteria (Morris, 2012)

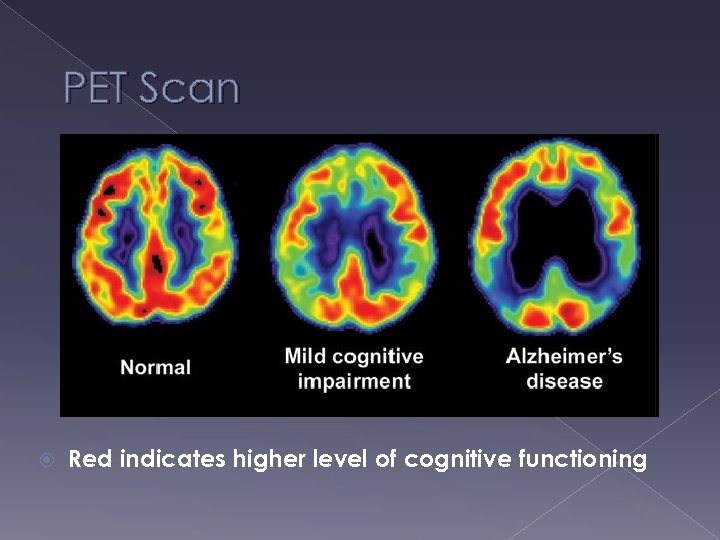

PET Scan Red indicates higher level of cognitive functioning

PET Scan Red indicates higher level of cognitive functioning

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) MCI is a transitional phase between normal ageing and dementia. › Approximately 10% annual conversion rate but this does not always occur. People with MCI typically experience objective memory complaints, but everyday functioning is still preserved. Usually occurs in adults over 65 Chances of developing cognitive impairment increase with age. Much debate in the literature about MCI Definition – Numerous terms used in research Criteria – Differing criteria (Morris, 2012)

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) MCI is a transitional phase between normal ageing and dementia. › Approximately 10% annual conversion rate but this does not always occur. People with MCI typically experience objective memory complaints, but everyday functioning is still preserved. Usually occurs in adults over 65 Chances of developing cognitive impairment increase with age. Much debate in the literature about MCI Definition – Numerous terms used in research Criteria – Differing criteria (Morris, 2012)

What are the issues with MCI? The number of people with MCI is set to rise in the coming years. Despite varying transition rates from MCI >Dementia, the psychological response to diagnosis could be the same. Dementia research tells us that people can have severe psychological reactions to diagnosis. › Same for people with MCI? Softening the delivery of the diagnosis: › Protect Client from fear or hurt › Protect those prone to anxiety and depression › Client and family may lose opportunity to prepare for future

What are the issues with MCI? The number of people with MCI is set to rise in the coming years. Despite varying transition rates from MCI >Dementia, the psychological response to diagnosis could be the same. Dementia research tells us that people can have severe psychological reactions to diagnosis. › Same for people with MCI? Softening the delivery of the diagnosis: › Protect Client from fear or hurt › Protect those prone to anxiety and depression › Client and family may lose opportunity to prepare for future

What are the issues with MCI? Little research on the nature of diagnostic reporting of MCI Client barriers: Delay in or avoidance of Diagnosis › Misattribution of symptoms › Fear of diagnosis › Stigma attached to cognitive impairment When a diagnosis of dementia is given, some people have a positive psychological response (eg, relief), while others have a negative psychological response (eg, fear).

What are the issues with MCI? Little research on the nature of diagnostic reporting of MCI Client barriers: Delay in or avoidance of Diagnosis › Misattribution of symptoms › Fear of diagnosis › Stigma attached to cognitive impairment When a diagnosis of dementia is given, some people have a positive psychological response (eg, relief), while others have a negative psychological response (eg, fear).

Summary of the Literature A diagnosis of cognitive impairment is distressing (Leszcz, 2011: Banningh et al. 2008), associated with feelings of fear and uncertainty (Coulson, Marino & Strang, 2005), and leads to changes in identity (Moniz-Cook et al. 2006) and self concept (Beard, 2004). On the other hand, for many diagnosis of cognitive impairment is a relief (Carpenter et al. 2008: Robinson et al. 2011) and linked to lower levels of psychological distress (Mc. Ilvane et al. 2008). Previous research in New Zealand indicated that 44% of practitioners do not label the term MCI or early dementia when they feedback results (Mitchell et al. 2007). Interactions with practitioners during diagnosis of serious illness can have an impact on functional outcomes with clients (Narita et al. 2009). The process by which a diagnosis is delivered and explained to those affected by cognitive difficulties is under-researched (Robinson et al. 2011).

Summary of the Literature A diagnosis of cognitive impairment is distressing (Leszcz, 2011: Banningh et al. 2008), associated with feelings of fear and uncertainty (Coulson, Marino & Strang, 2005), and leads to changes in identity (Moniz-Cook et al. 2006) and self concept (Beard, 2004). On the other hand, for many diagnosis of cognitive impairment is a relief (Carpenter et al. 2008: Robinson et al. 2011) and linked to lower levels of psychological distress (Mc. Ilvane et al. 2008). Previous research in New Zealand indicated that 44% of practitioners do not label the term MCI or early dementia when they feedback results (Mitchell et al. 2007). Interactions with practitioners during diagnosis of serious illness can have an impact on functional outcomes with clients (Narita et al. 2009). The process by which a diagnosis is delivered and explained to those affected by cognitive difficulties is under-researched (Robinson et al. 2011).

Shortfalls in Research Much of the research focuses on Dementia and overlooks MCI. Definition of MCI in research has been variable. Though some reactions have been documented, little has been done to explain why some people respond positively and others don’t. No model or framework of understanding to help predict who is likely to cope and who isn’t. Investigations have been restricted (eg, use of quantitative measures over qualitative measures) Changes in perception of diagnosis over time have not been investigated.

Shortfalls in Research Much of the research focuses on Dementia and overlooks MCI. Definition of MCI in research has been variable. Though some reactions have been documented, little has been done to explain why some people respond positively and others don’t. No model or framework of understanding to help predict who is likely to cope and who isn’t. Investigations have been restricted (eg, use of quantitative measures over qualitative measures) Changes in perception of diagnosis over time have not been investigated.

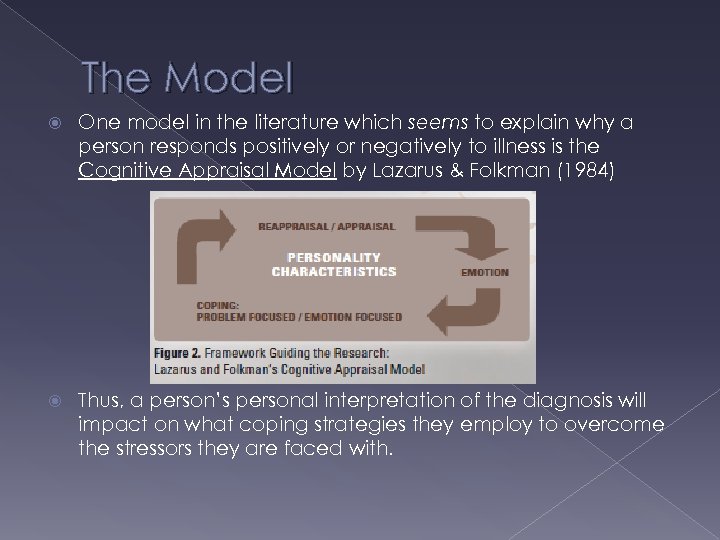

The Model One model in the literature which seems to explain why a person responds positively or negatively to illness is the Cognitive Appraisal Model by Lazarus & Folkman (1984) Thus, a person’s personal interpretation of the diagnosis will impact on what coping strategies they employ to overcome the stressors they are faced with.

The Model One model in the literature which seems to explain why a person responds positively or negatively to illness is the Cognitive Appraisal Model by Lazarus & Folkman (1984) Thus, a person’s personal interpretation of the diagnosis will impact on what coping strategies they employ to overcome the stressors they are faced with.

Shortfalls in Research Much of the research focuses on Dementia and overlooks MCI. Definition of MCI in research has been variable. Though some reactions have been documented, little has been done to explain why some people respond positively and others don’t. No model or framework of understanding to help predict who is likely to cope and who isn’t. Investigations have been restricted (eg, use of quantitative measures over qualitative measures) Changes in perception of diagnosis over time have not been investigated.

Shortfalls in Research Much of the research focuses on Dementia and overlooks MCI. Definition of MCI in research has been variable. Though some reactions have been documented, little has been done to explain why some people respond positively and others don’t. No model or framework of understanding to help predict who is likely to cope and who isn’t. Investigations have been restricted (eg, use of quantitative measures over qualitative measures) Changes in perception of diagnosis over time have not been investigated.

The Current Research Study 1 – Practitioners’ processes and attitudes regarding the diagnosis of cognitive impairment in New Zealand Study 2 –How do older adults cope with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment

The Current Research Study 1 – Practitioners’ processes and attitudes regarding the diagnosis of cognitive impairment in New Zealand Study 2 –How do older adults cope with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment

Study 1 Status: Seeking Ethics Approval Aims: To present an impression of diagnostic practices of cognitive impairment in NZ. To inform future research relating to how people cope with a diagnosis of MCI (addressed in Study 2). Methodology: Cross sectional, survey design

Study 1 Status: Seeking Ethics Approval Aims: To present an impression of diagnostic practices of cognitive impairment in NZ. To inform future research relating to how people cope with a diagnosis of MCI (addressed in Study 2). Methodology: Cross sectional, survey design

Study 2 - Research Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. How do people react when they’re diagnosed with MCI? What mechanisms are underlying the coping process as a person comes to cope or not cope with their illness? How does this change over time? What do clients with MCI recommend for the delivery of diagnosis to help future clients diagnosed with MCI?

Study 2 - Research Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. How do people react when they’re diagnosed with MCI? What mechanisms are underlying the coping process as a person comes to cope or not cope with their illness? How does this change over time? What do clients with MCI recommend for the delivery of diagnosis to help future clients diagnosed with MCI?

Study 2 - Hypotheses • • The following variables will provide valuable information in isolating what influences positive or negative coping strategies: • Social Support and Loneliness • Religiousness and Spirituality • Hope and Resiliency • Illness Perception The cognitive appraisal model will be a useful framework for predicting coping strategies

Study 2 - Hypotheses • • The following variables will provide valuable information in isolating what influences positive or negative coping strategies: • Social Support and Loneliness • Religiousness and Spirituality • Hope and Resiliency • Illness Perception The cognitive appraisal model will be a useful framework for predicting coping strategies

Study 2 - Methodology (Proposed) Design: › Data will be longitudinal, via interview and questionnaires collected at several points in time to monitor change in coping behaviours. Participants : › Recruited through memory clinics in 3 main centres of New Zealand. › Diagnosed with MCI in the previous 3 month period.

Study 2 - Methodology (Proposed) Design: › Data will be longitudinal, via interview and questionnaires collected at several points in time to monitor change in coping behaviours. Participants : › Recruited through memory clinics in 3 main centres of New Zealand. › Diagnosed with MCI in the previous 3 month period.

Study 2 - Methodology (Proposed) Procedure – face to face interviews › Quantitative – questionnaire General Health, Mental Health and Social functioning subscales of the SF-36 v 2 Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) Six Item Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ 6) 14 Item Resilience Scale (RS-14) Brief COPE (Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced) › Qualitative – discussion Participants will be asked open ended questions about experiences of diagnosis and coping.

Study 2 - Methodology (Proposed) Procedure – face to face interviews › Quantitative – questionnaire General Health, Mental Health and Social functioning subscales of the SF-36 v 2 Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ) Six Item Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ 6) 14 Item Resilience Scale (RS-14) Brief COPE (Coping Orientations to Problems Experienced) › Qualitative – discussion Participants will be asked open ended questions about experiences of diagnosis and coping.

Study 2 - Analysis Mixed methods › Quantitative data will be analysed using multivariate regression analysis. › Though undecided upon at this stage, qualitative data will be coded analysed using: the grounded theory approach, as is commonly used with this kind of exploratory research (Banningh et al. 2008: Lingler et al. 2006: Beard, 2004).

Study 2 - Analysis Mixed methods › Quantitative data will be analysed using multivariate regression analysis. › Though undecided upon at this stage, qualitative data will be coded analysed using: the grounded theory approach, as is commonly used with this kind of exploratory research (Banningh et al. 2008: Lingler et al. 2006: Beard, 2004).

Anticipated outcome • • • It is hoped that this research will reveal practical ways that people with MCI have coped in the past. This will provide information for clients and their families diagnosed with MCI in the future. That it will provide useful feedback to practitioners Further that the findings will provide a guide to other researchers who are considering implementing psychosocial intervention for people who have been recently diagnosed with MCI.

Anticipated outcome • • • It is hoped that this research will reveal practical ways that people with MCI have coped in the past. This will provide information for clients and their families diagnosed with MCI in the future. That it will provide useful feedback to practitioners Further that the findings will provide a guide to other researchers who are considering implementing psychosocial intervention for people who have been recently diagnosed with MCI.

References Banningh, L. , Vernooij-Dassen, M. , Rikkert, M. O. , & Teunisse, J. P. (2008). “Mild cognitive impairment: coping with an uncertain label. ” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 148 -154. Beard, R. L. (2004). "In their voices: Identity preservation and experiences of Alzheimer's disease. " Journal of Aging Studies 18(4): 415 -428. Carpenter, B. D. , C. Xiong, et al. (2008). "Reaction to a dementia diagnosis in individuals with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. " Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56(3): 405 -412. Coulson, I. , Marino, R. , & Strang, V. (2005). Considerations and challenges in the prevention of dementia (pp. 105 -119). In V Minichiello, & I Coulson (Eds. ), Contemporary issues in gerontology. New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. Lazarus, R. S. , & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing. Lingler, J. H. , et al. (2006). “Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: A qualitative exploration of the patient’s experience. ” The Gerontologist, 45, 791 -800. Leszcz, M. (2011). “Psychotherapeutic approaches for patients with cognitive impairment. International journal of Group Psychotherapy. ” 61 (1): 153 -158. Ministry of Health. (2011). Mental Health and Addiction Services for Older People and Dementia Services: Guideline for district health boards on an integrated approach to mental health an addiction services for older people and dementia services for people of any age. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Mitchell, T. , M. Woodward, et al. (2008). "A survey of attitudes of clinicians towards the diagnosis and treatment of mild cognitive impairment in Australia and New Zealand. " International Psychogeriatrics 20(1): 77 -85. Moniz-Cook, E. , Manthorpe, J. , Carr, L. , Gibson, G. , & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2006). Facing the future: a qualitative study of older people referred to a memory clinic prior to assessment and diagnosis. Dementia, 5, 375 -395. Narita, Y. , Miyakita, Y. , Momota, H. , Miyahara, R. , & Shibui, S. (2009). A survey of neurosurgeons’ policies and attitudes regarding the disclosure of a diagnosis of glioma and the decision to pursue end of life care in glioma patients. Neurological Surgery, 10, 973 -981. Robinson, L. , A. Gemski, et al. (2011). "The transition to dementia - individual and family experiences of receiving a diagnosis: a review. " International Psychogeriatrics, 23(7): 1026 -1043.

References Banningh, L. , Vernooij-Dassen, M. , Rikkert, M. O. , & Teunisse, J. P. (2008). “Mild cognitive impairment: coping with an uncertain label. ” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 148 -154. Beard, R. L. (2004). "In their voices: Identity preservation and experiences of Alzheimer's disease. " Journal of Aging Studies 18(4): 415 -428. Carpenter, B. D. , C. Xiong, et al. (2008). "Reaction to a dementia diagnosis in individuals with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. " Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56(3): 405 -412. Coulson, I. , Marino, R. , & Strang, V. (2005). Considerations and challenges in the prevention of dementia (pp. 105 -119). In V Minichiello, & I Coulson (Eds. ), Contemporary issues in gerontology. New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin. Lazarus, R. S. , & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publishing. Lingler, J. H. , et al. (2006). “Making sense of mild cognitive impairment: A qualitative exploration of the patient’s experience. ” The Gerontologist, 45, 791 -800. Leszcz, M. (2011). “Psychotherapeutic approaches for patients with cognitive impairment. International journal of Group Psychotherapy. ” 61 (1): 153 -158. Ministry of Health. (2011). Mental Health and Addiction Services for Older People and Dementia Services: Guideline for district health boards on an integrated approach to mental health an addiction services for older people and dementia services for people of any age. Wellington: Ministry of Health. Mitchell, T. , M. Woodward, et al. (2008). "A survey of attitudes of clinicians towards the diagnosis and treatment of mild cognitive impairment in Australia and New Zealand. " International Psychogeriatrics 20(1): 77 -85. Moniz-Cook, E. , Manthorpe, J. , Carr, L. , Gibson, G. , & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2006). Facing the future: a qualitative study of older people referred to a memory clinic prior to assessment and diagnosis. Dementia, 5, 375 -395. Narita, Y. , Miyakita, Y. , Momota, H. , Miyahara, R. , & Shibui, S. (2009). A survey of neurosurgeons’ policies and attitudes regarding the disclosure of a diagnosis of glioma and the decision to pursue end of life care in glioma patients. Neurological Surgery, 10, 973 -981. Robinson, L. , A. Gemski, et al. (2011). "The transition to dementia - individual and family experiences of receiving a diagnosis: a review. " International Psychogeriatrics, 23(7): 1026 -1043.