What is the Chinese philosophy? Four influential schools

![in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey, in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey,](https://present5.com/presentacii-2/20171208\11222-the_chinese_philosophy_of_science_lecture_14.ppt\11222-the_chinese_philosophy_of_science_lecture_14_15.jpg)

11222-the_chinese_philosophy_of_science_lecture_14.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 50

What is the Chinese philosophy?

What is the Chinese philosophy?

Four influential schools came into Existence about 500 BC Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought

Four influential schools came into Existence about 500 BC Contention of a Hundred Schools of Thought

Confucianism Quasi-religious in nature Meritocracy and the Golden Rule Yin and Yang (endless contradiction; find the Middle Ground) Ren (humanness); Zhengming (rectification of Names); Zhong (loyalty); Xiao (filial piety); Li (ritual)

Confucianism Quasi-religious in nature Meritocracy and the Golden Rule Yin and Yang (endless contradiction; find the Middle Ground) Ren (humanness); Zhengming (rectification of Names); Zhong (loyalty); Xiao (filial piety); Li (ritual)

To be able under all circumstances to practice five things constitutes perfect virtue; these five things are gravity, generosity of soul, sincerity, earnestness and kindness.

To be able under all circumstances to practice five things constitutes perfect virtue; these five things are gravity, generosity of soul, sincerity, earnestness and kindness.

Taoism Humanism, relativism, emptiness, spontaneity, flexibility, non-action

Taoism Humanism, relativism, emptiness, spontaneity, flexibility, non-action

“Knowing others is intelligence; knowing yourself is true wisdom. Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.” ― Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

“Knowing others is intelligence; knowing yourself is true wisdom. Mastering others is strength; mastering yourself is true power.” ― Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

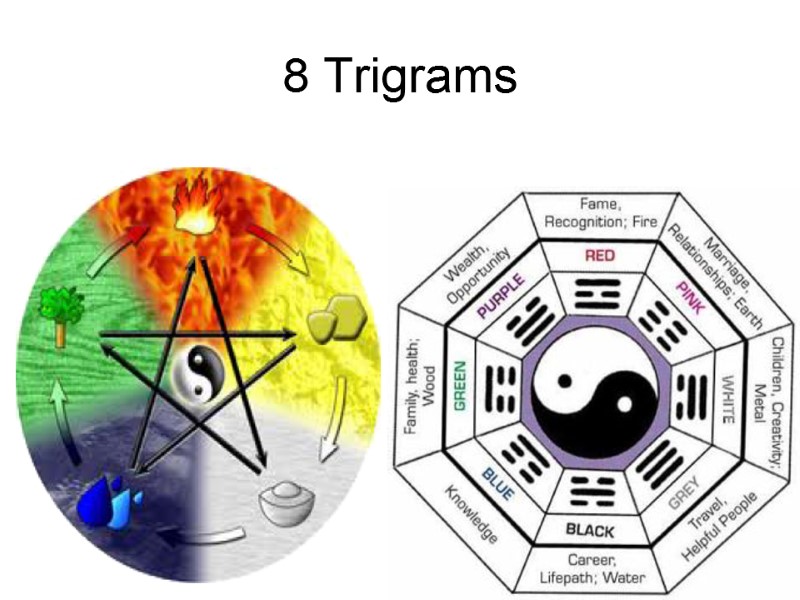

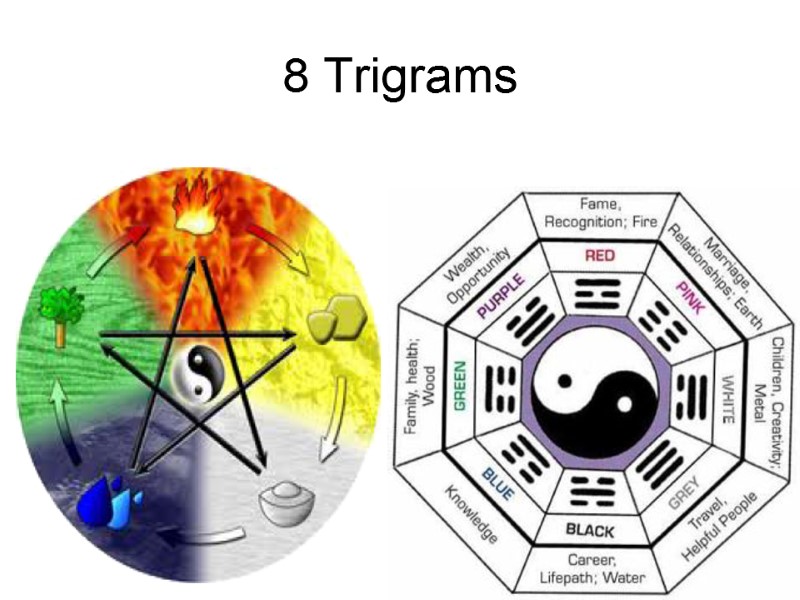

8 Trigrams

8 Trigrams

Legalism Strict laws and harsh punishment Fa (Law) Shu (Tactic, art, method and managing state affairs) Shi (power and legitimacy)

Legalism Strict laws and harsh punishment Fa (Law) Shu (Tactic, art, method and managing state affairs) Shi (power and legitimacy)

Mohism Mutual benefit by the universal love (otherwise war is inevitable) Mozi (470-390 BC) was against Confucianism. Farming, fortification, managing stat e affairs are more practical ways of survival

Mohism Mutual benefit by the universal love (otherwise war is inevitable) Mozi (470-390 BC) was against Confucianism. Farming, fortification, managing stat e affairs are more practical ways of survival

“If the rulers sincerely desire the empire to be wealthy and dislike to have it poor, desire to have it orderly and dislike to have it chaotic, they should bring about universal love and mutual aid. This is the way of the sage-kings and the way to order for the world, and it should not be neglected.” ―Mozi

“If the rulers sincerely desire the empire to be wealthy and dislike to have it poor, desire to have it orderly and dislike to have it chaotic, they should bring about universal love and mutual aid. This is the way of the sage-kings and the way to order for the world, and it should not be neglected.” ―Mozi

fa (法 principle or method) was developed by the School of Names (名家Ming jia, ming=name), which initiated a systematic exploration of logic. All this was cut short by the downfall of Mohism's political sponsors during the Qin Dynasty, and the subsumption of fa as law rather than method by the Legalists (法家Fajia)

fa (法 principle or method) was developed by the School of Names (名家Ming jia, ming=name), which initiated a systematic exploration of logic. All this was cut short by the downfall of Mohism's political sponsors during the Qin Dynasty, and the subsumption of fa as law rather than method by the Legalists (法家Fajia)

Stereotypes of Chinese philosophy as consisting almost entirely of Confucianism and claims that Confucians were not interested in science add to this perception.

Stereotypes of Chinese philosophy as consisting almost entirely of Confucianism and claims that Confucians were not interested in science add to this perception.

Two cultural genes have passed through generations of Chinese intellectuals for more than 2,000 years. The first is the thoughts of Confucius, who proposed that intellectuals should become loyal administrators. The second is the writings of Zhuang Zhou, who said that a harmonious society would come from isolating families so as to avoid exchange and conflict, and by shunning technology to avoid greed. Together, these cultures have encouraged small-scale and self-sufficient practices in Chinese society, but discouraged curiosity, commercialization and technology.

Two cultural genes have passed through generations of Chinese intellectuals for more than 2,000 years. The first is the thoughts of Confucius, who proposed that intellectuals should become loyal administrators. The second is the writings of Zhuang Zhou, who said that a harmonious society would come from isolating families so as to avoid exchange and conflict, and by shunning technology to avoid greed. Together, these cultures have encouraged small-scale and self-sufficient practices in Chinese society, but discouraged curiosity, commercialization and technology.

![>in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey, >in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey,](https://present5.com/presentacii-2/20171208\11222-the_chinese_philosophy_of_science_lecture_14.ppt\11222-the_chinese_philosophy_of_science_lecture_14_15.jpg) in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey, argued that: “what keeps China back is that she has no science,” but that: “China has no science, because according to her own standard of value she does not need any.”

in 1922, Fung Yu-lan [Feng Youlan] 馮友蘭 (1895–1990), then a student of John Dewey, argued that: “what keeps China back is that she has no science,” but that: “China has no science, because according to her own standard of value she does not need any.”

he introduces what he calls two tendencies in Chinese philosophy, which he calls “nature” and “art” On his account, the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) developed two philosophies, Daoism and Mohism respectively, which followed these two tendencies to extreme, and a third, Confucianism, which he represents as a compromise between them.

he introduces what he calls two tendencies in Chinese philosophy, which he calls “nature” and “art” On his account, the Warring States period (475–221 BCE) developed two philosophies, Daoism and Mohism respectively, which followed these two tendencies to extreme, and a third, Confucianism, which he represents as a compromise between them.

he distinguishes the “nature” oriented Confucianism of Mencius (372–289 BCE) from the “art”-oriented Confucianism of Xunzi (313-238 BCE), who aspired to conquer nature instead of returning to it: “It is better to treat nature as a thing and regulate it than to consider it very great and always think of it. It is better to control nature and use it than to follow and admire it.” This, Fung remarks, is nearly the same as the Baconian conception of power

he distinguishes the “nature” oriented Confucianism of Mencius (372–289 BCE) from the “art”-oriented Confucianism of Xunzi (313-238 BCE), who aspired to conquer nature instead of returning to it: “It is better to treat nature as a thing and regulate it than to consider it very great and always think of it. It is better to control nature and use it than to follow and admire it.” This, Fung remarks, is nearly the same as the Baconian conception of power

after the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) the “art” or scientific tendency within Chinese philosophy all but disappeared

after the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE) the “art” or scientific tendency within Chinese philosophy all but disappeared

In the tenth century CE the Song Neo-Confucians combined Daoist, Confucian and Buddhist teachings into a new philosophy that has persisted to the present. According to the “Great Learning” (Da xue), the ancients who wished to enlighten their bright virtue “investigated things”:

In the tenth century CE the Song Neo-Confucians combined Daoist, Confucian and Buddhist teachings into a new philosophy that has persisted to the present. According to the “Great Learning” (Da xue), the ancients who wished to enlighten their bright virtue “investigated things”:

Wishing to be sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things (zhi zhi zai ge wu 致知在格物). Things being investigated, knowledge became complete (Da xue, 412).

Wishing to be sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things (zhi zhi zai ge wu 致知在格物). Things being investigated, knowledge became complete (Da xue, 412).

But Neo-Confucian philosophers disagreed about what “things” to investigate. Some took “things” as external, but did not pursue the investigation of the empirical world. The other, prevailing view took “things” to refer to the mind. Fung points out that the Song dynasty (960–1279) corresponded to the period of the development of modern science in Europe, but Europeans developed techniques for understanding and controlling matter, while the Chinese Neo-Confucians developed techniques for understanding and controlling mind

But Neo-Confucian philosophers disagreed about what “things” to investigate. Some took “things” as external, but did not pursue the investigation of the empirical world. The other, prevailing view took “things” to refer to the mind. Fung points out that the Song dynasty (960–1279) corresponded to the period of the development of modern science in Europe, but Europeans developed techniques for understanding and controlling matter, while the Chinese Neo-Confucians developed techniques for understanding and controlling mind

the meaning of xin – “mind,” or more properly “heart-mind” – is much broader than the English term mind, cultivating it refers to a much broader kind of cognitive, intellectual, physical and spiritual cultivation than the phrase “cultivation of the mind” suggests

the meaning of xin – “mind,” or more properly “heart-mind” – is much broader than the English term mind, cultivating it refers to a much broader kind of cognitive, intellectual, physical and spiritual cultivation than the phrase “cultivation of the mind” suggests

China did not discover the scientific method because Chinese thought started from the mind, and did not require proof or logical or empirical demonstration. Instead, Chinese philosophers preferred the certainty of perception, and thus: “would not, and did not translate their concrete vision into the form of science. In one word China has no science, because of all philosophies the Chinese philosophy is the most human and the most practical”

China did not discover the scientific method because Chinese thought started from the mind, and did not require proof or logical or empirical demonstration. Instead, Chinese philosophers preferred the certainty of perception, and thus: “would not, and did not translate their concrete vision into the form of science. In one word China has no science, because of all philosophies the Chinese philosophy is the most human and the most practical”

mathematics (suan 算), mathematical harmonics or acoustics (lü 律 or lü lü 律呂) and mathematical astronomy (li 歷 or li fa 歷法) astronomy or astrology (tian wen 天文) included the observation of celestial and meteorological events whose proper reading could be used to rectify the political order

mathematics (suan 算), mathematical harmonics or acoustics (lü 律 or lü lü 律呂) and mathematical astronomy (li 歷 or li fa 歷法) astronomy or astrology (tian wen 天文) included the observation of celestial and meteorological events whose proper reading could be used to rectify the political order

Using shadow clocks and the abacus (both invented in the ancient Near East before spreading to China), the Chinese were able to record observations, documenting the first recorded solar eclipse in 2137 BC, and making the first recording of any planetary grouping in 500 BC.

Using shadow clocks and the abacus (both invented in the ancient Near East before spreading to China), the Chinese were able to record observations, documenting the first recorded solar eclipse in 2137 BC, and making the first recording of any planetary grouping in 500 BC.

Chinese astronomers were the first to record observations of a supernova recorded during the Han Dynasty. Chinese astronomers made two more notable supernova observations during the Song Dynasty

Chinese astronomers were the first to record observations of a supernova recorded during the Han Dynasty. Chinese astronomers made two more notable supernova observations during the Song Dynasty

The Book of Silk was the first definitive atlas of comets, written c.400 BC. It listed 29 comets (referred to as sweeping stars) that appeared over a period of about 300 years

The Book of Silk was the first definitive atlas of comets, written c.400 BC. It listed 29 comets (referred to as sweeping stars) that appeared over a period of about 300 years

Medicine included “Nurturing Life” (yang sheng 養生), a broad category that included a wide range of self-cultivation techniques with important philosophical implications. In later periods, medicine also included materia medica (ben cao 本草) and internal (nei dan 內丹) and external (wai dan 外丹) alchemy.

Medicine included “Nurturing Life” (yang sheng 養生), a broad category that included a wide range of self-cultivation techniques with important philosophical implications. In later periods, medicine also included materia medica (ben cao 本草) and internal (nei dan 內丹) and external (wai dan 外丹) alchemy.

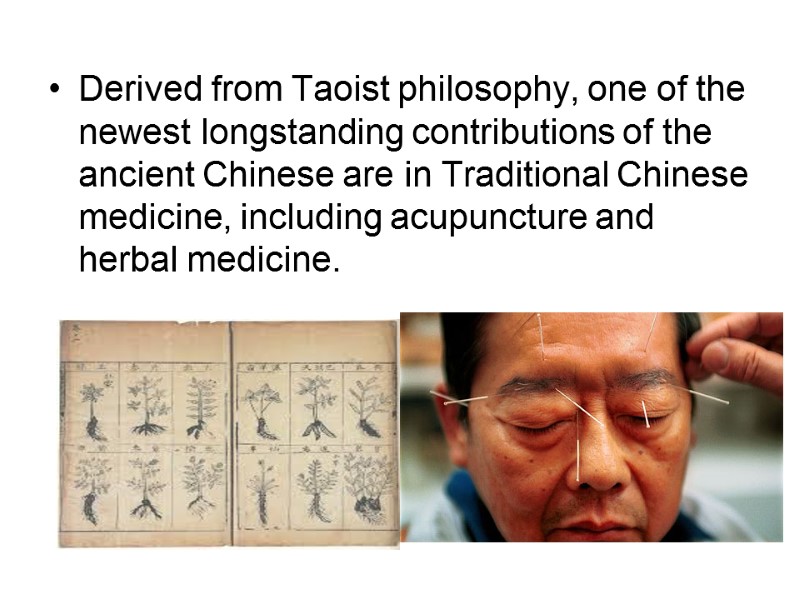

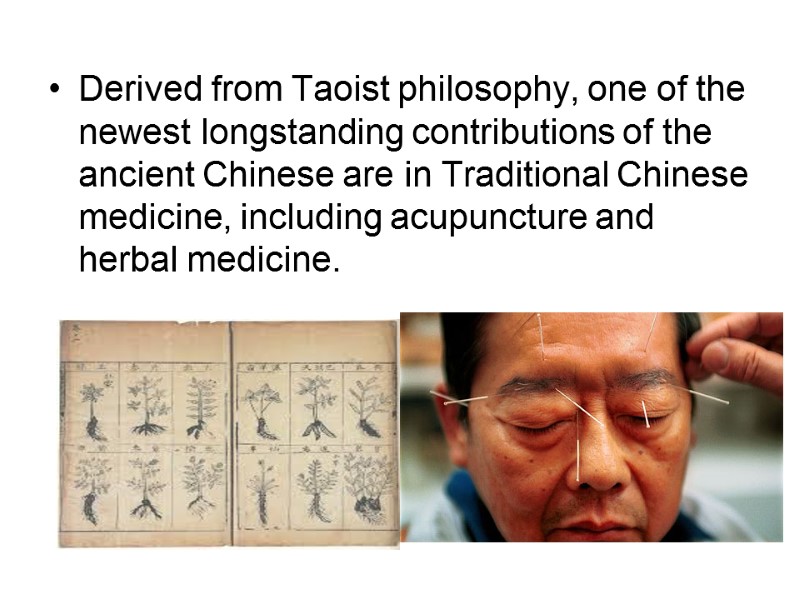

Derived from Taoist philosophy, one of the newest longstanding contributions of the ancient Chinese are in Traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture and herbal medicine.

Derived from Taoist philosophy, one of the newest longstanding contributions of the ancient Chinese are in Traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture and herbal medicine.

siting (feng shui 風水)

siting (feng shui 風水)

The written language was ill adapted to the expression of scientific ideas, the combined influence of an authoritarian imperial government, a conservative academic elite and a philosophical tradition preoccupied with morals and burdened by “organicist” thinking

The written language was ill adapted to the expression of scientific ideas, the combined influence of an authoritarian imperial government, a conservative academic elite and a philosophical tradition preoccupied with morals and burdened by “organicist” thinking

Humans were not distinct from other natural phenomena, and were part of a dao that was ultimately mysterious and incomprehensible But, in the same time, most scientific and technical expertise arose from popular sources and not from Daoist schools; and once this key distinction is made, we no longer need to mis-classify all or most Chinese science as Daoist

Humans were not distinct from other natural phenomena, and were part of a dao that was ultimately mysterious and incomprehensible But, in the same time, most scientific and technical expertise arose from popular sources and not from Daoist schools; and once this key distinction is made, we no longer need to mis-classify all or most Chinese science as Daoist

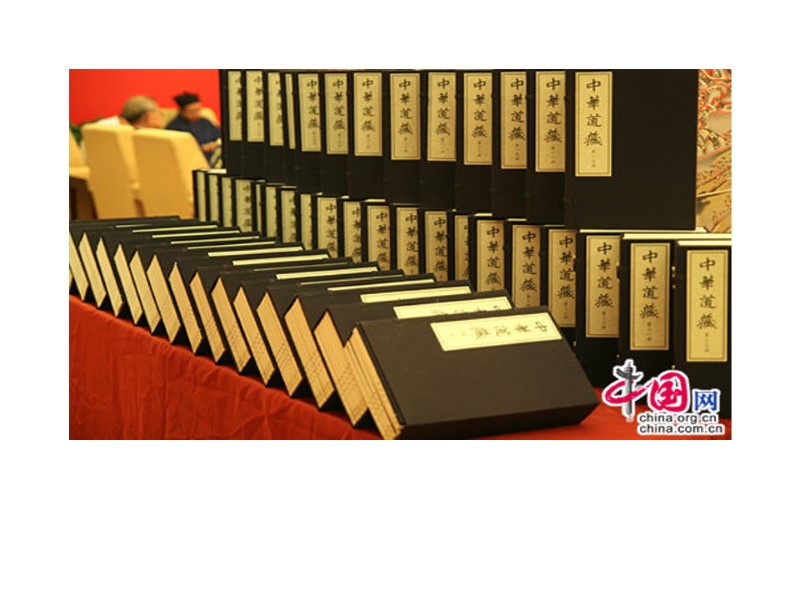

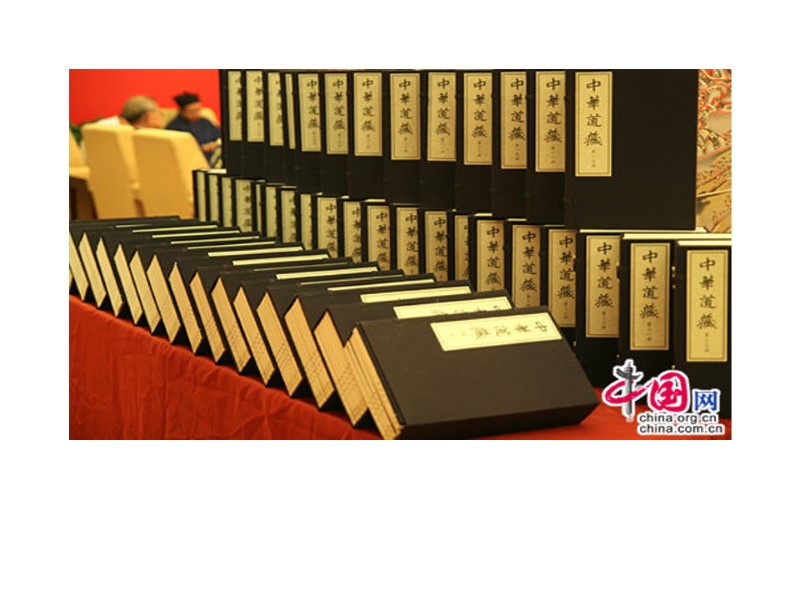

The Daoist Canon (Dao zang 道藏) was first printed in about 1477, and was reprinted in a commercial edition in 1924–1926. The original edition consisted of some 5,305 volumes, on a wide range of subjects, including astronomy and cosmology, biology and botany, medicine and pharmacology, chemistry and mineralogy, and mathematics and physics. Much of the engagement with science after the Han dynasty is relegated to the “non-philosophical” texts classified as Dao jiao, and often in ways that obscure the relation between philosophy and science in early China.

The Daoist Canon (Dao zang 道藏) was first printed in about 1477, and was reprinted in a commercial edition in 1924–1926. The original edition consisted of some 5,305 volumes, on a wide range of subjects, including astronomy and cosmology, biology and botany, medicine and pharmacology, chemistry and mineralogy, and mathematics and physics. Much of the engagement with science after the Han dynasty is relegated to the “non-philosophical” texts classified as Dao jiao, and often in ways that obscure the relation between philosophy and science in early China.

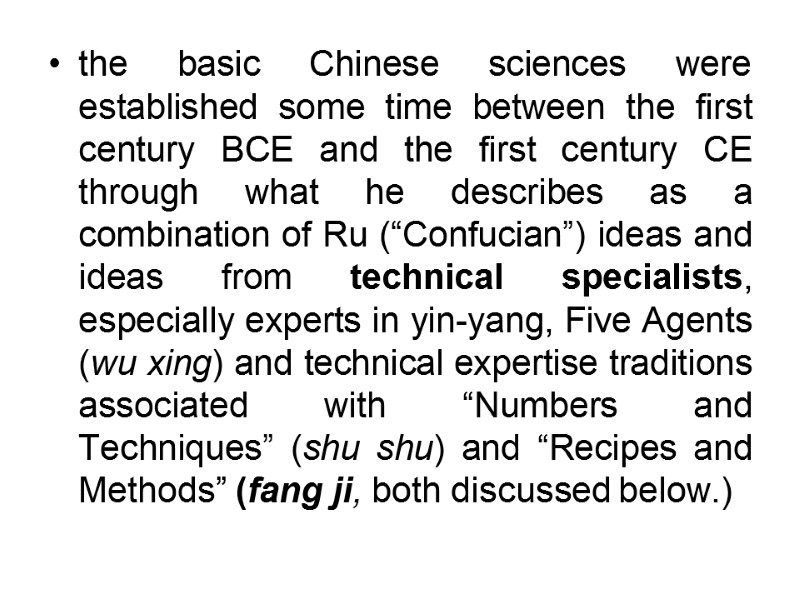

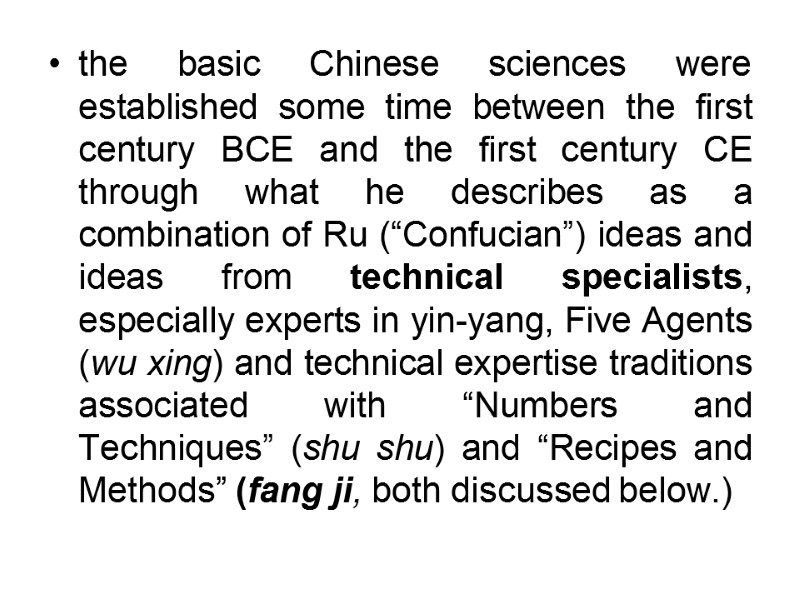

the basic Chinese sciences were established some time between the first century BCE and the first century CE through what he describes as a combination of Ru (“Confucian”) ideas and ideas from technical specialists, especially experts in yin-yang, Five Agents (wu xing) and technical expertise traditions associated with “Numbers and Techniques” (shu shu) and “Recipes and Methods” (fang ji, both discussed below.)

the basic Chinese sciences were established some time between the first century BCE and the first century CE through what he describes as a combination of Ru (“Confucian”) ideas and ideas from technical specialists, especially experts in yin-yang, Five Agents (wu xing) and technical expertise traditions associated with “Numbers and Techniques” (shu shu) and “Recipes and Methods” (fang ji, both discussed below.)

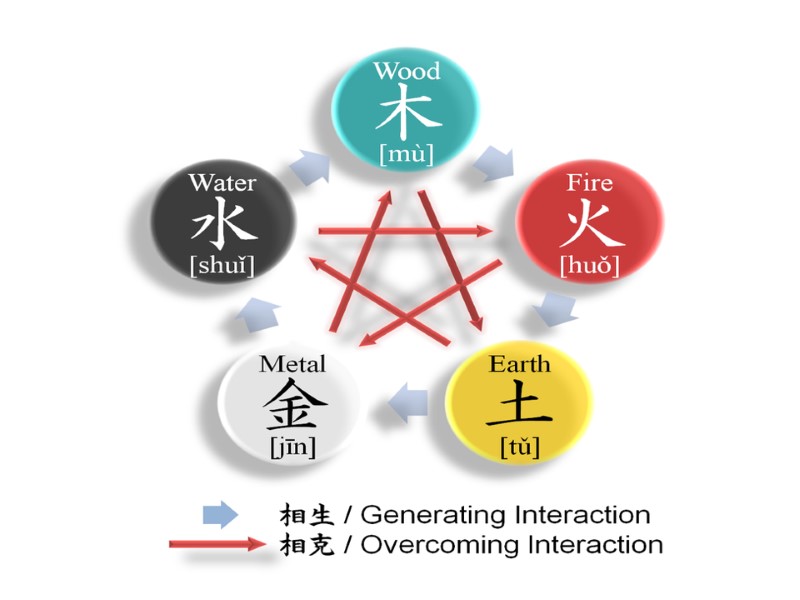

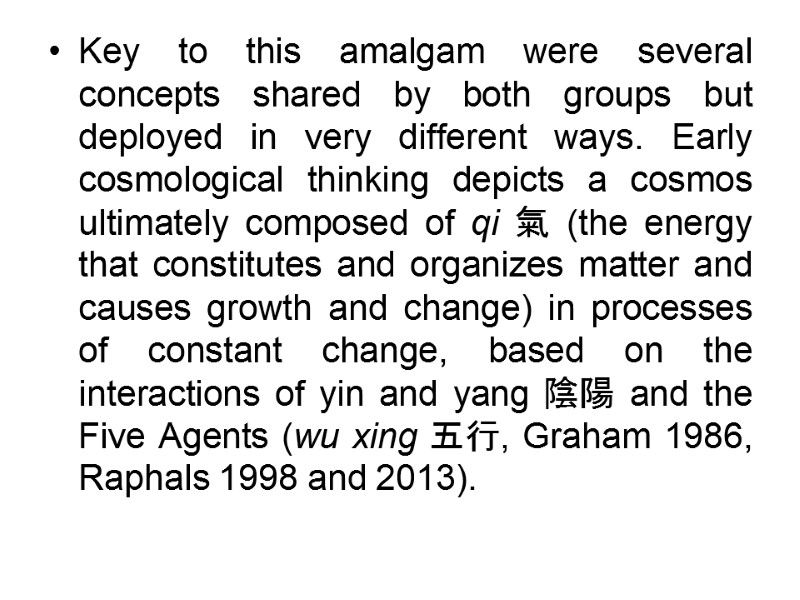

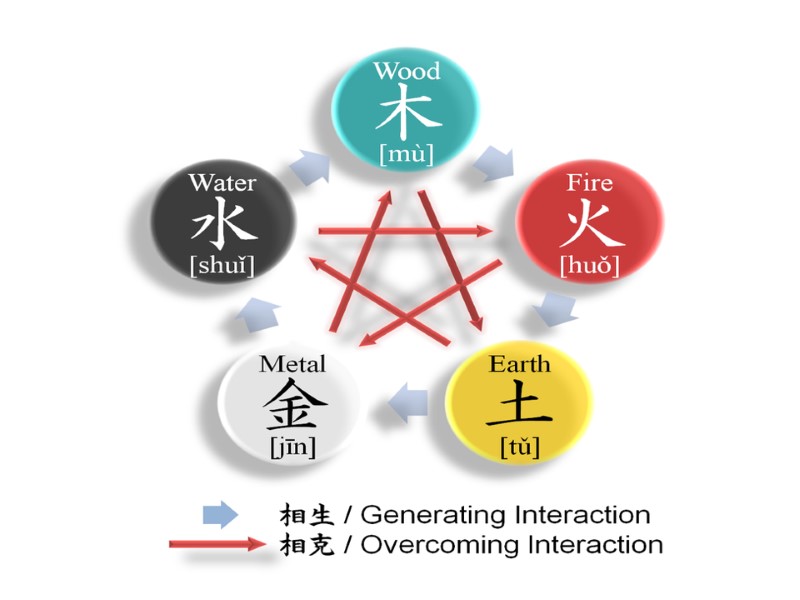

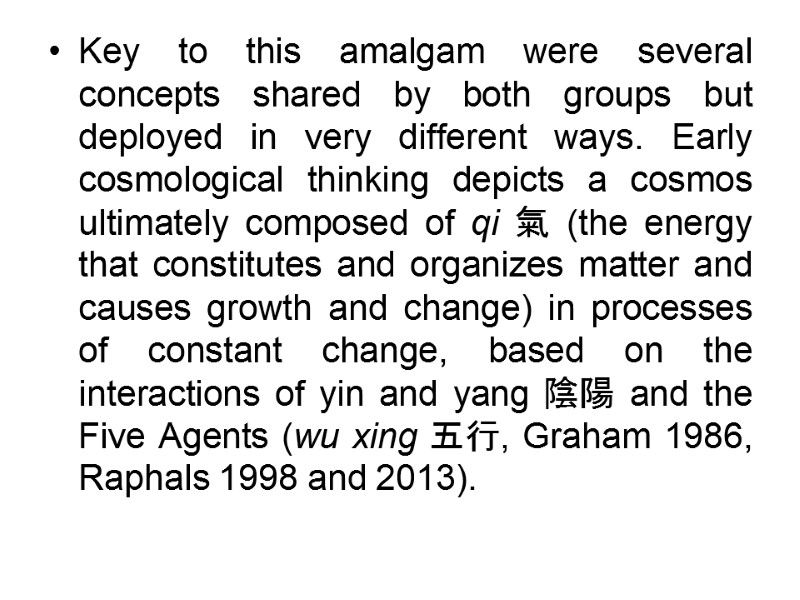

Key to this amalgam were several concepts shared by both groups but deployed in very different ways. Early cosmological thinking depicts a cosmos ultimately composed of qi 氣 (the energy that constitutes and organizes matter and causes growth and change) in processes of constant change, based on the interactions of yin and yang 陰陽 and the Five Agents (wu xing 五行, Graham 1986, Raphals 1998 and 2013).

Key to this amalgam were several concepts shared by both groups but deployed in very different ways. Early cosmological thinking depicts a cosmos ultimately composed of qi 氣 (the energy that constitutes and organizes matter and causes growth and change) in processes of constant change, based on the interactions of yin and yang 陰陽 and the Five Agents (wu xing 五行, Graham 1986, Raphals 1998 and 2013).

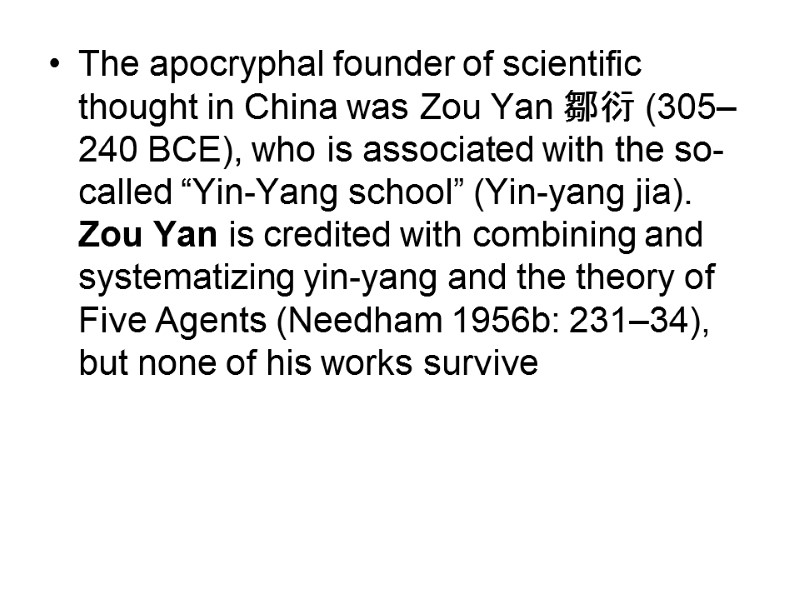

The apocryphal founder of scientific thought in China was Zou Yan 鄒衍 (305–240 BCE), who is associated with the so-called “Yin-Yang school” (Yin-yang jia). Zou Yan is credited with combining and systematizing yin-yang and the theory of Five Agents (Needham 1956b: 231–34), but none of his works survive

The apocryphal founder of scientific thought in China was Zou Yan 鄒衍 (305–240 BCE), who is associated with the so-called “Yin-Yang school” (Yin-yang jia). Zou Yan is credited with combining and systematizing yin-yang and the theory of Five Agents (Needham 1956b: 231–34), but none of his works survive

Philosophers deployed these ideas in (1) the yin-yang cosmology of the Yi jing, (2) theories of correlative correspondence between Heaven, Earth and Humanity as a shared representation of cosmic order, and (3) the idea of a “classic” or “canon” as the founding text of a textual lineage. Fang expertise also included divination by the heavens, both by the stars, and by interpreting sub-celestial phenomena, including weather, clouds, mists, and winds

Philosophers deployed these ideas in (1) the yin-yang cosmology of the Yi jing, (2) theories of correlative correspondence between Heaven, Earth and Humanity as a shared representation of cosmic order, and (3) the idea of a “classic” or “canon” as the founding text of a textual lineage. Fang expertise also included divination by the heavens, both by the stars, and by interpreting sub-celestial phenomena, including weather, clouds, mists, and winds

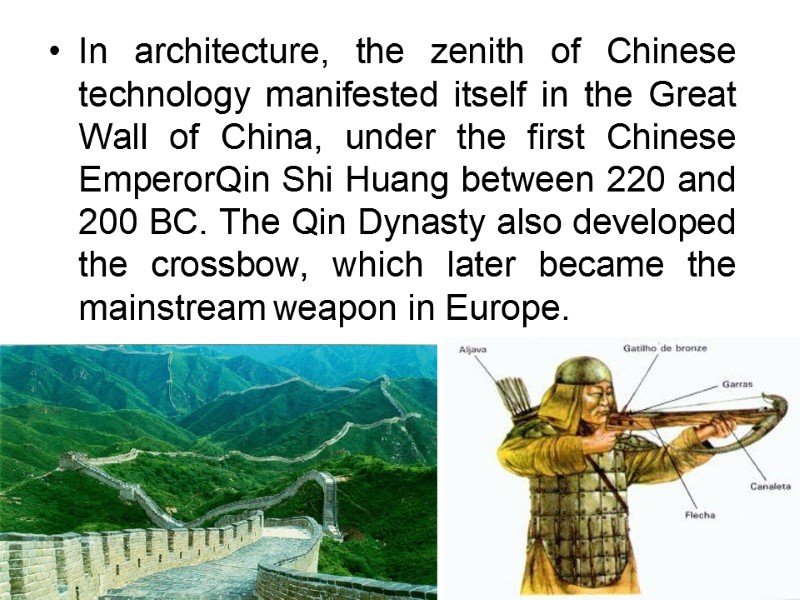

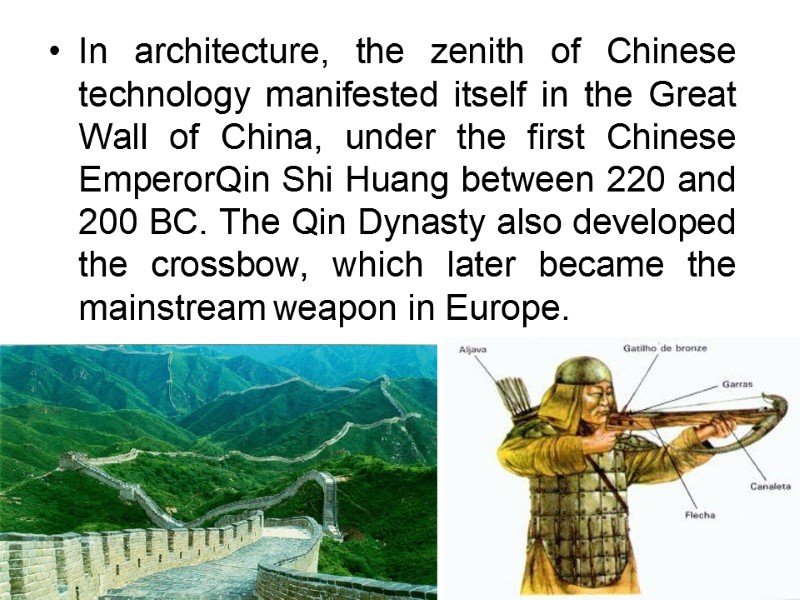

In architecture, the zenith of Chinese technology manifested itself in the Great Wall of China, under the first Chinese EmperorQin Shi Huang between 220 and 200 BC. The Qin Dynasty also developed the crossbow, which later became the mainstream weapon in Europe.

In architecture, the zenith of Chinese technology manifested itself in the Great Wall of China, under the first Chinese EmperorQin Shi Huang between 220 and 200 BC. The Qin Dynasty also developed the crossbow, which later became the mainstream weapon in Europe.

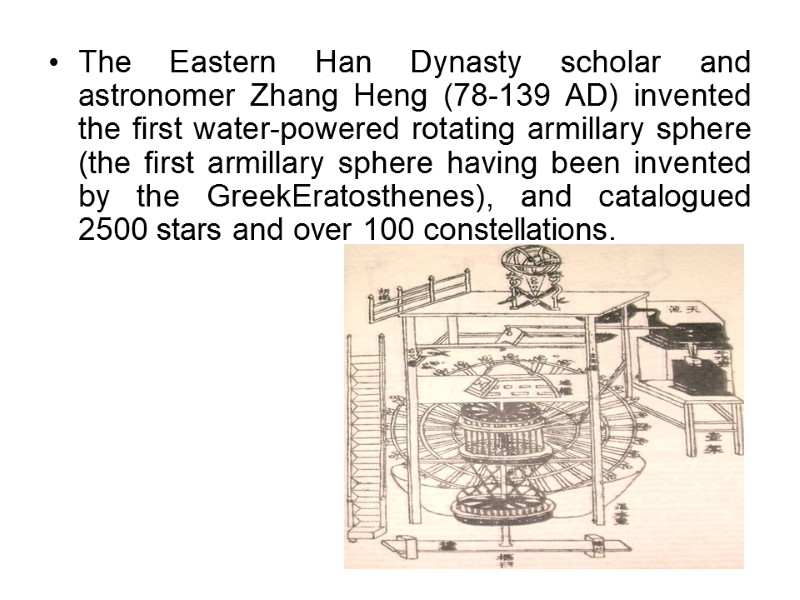

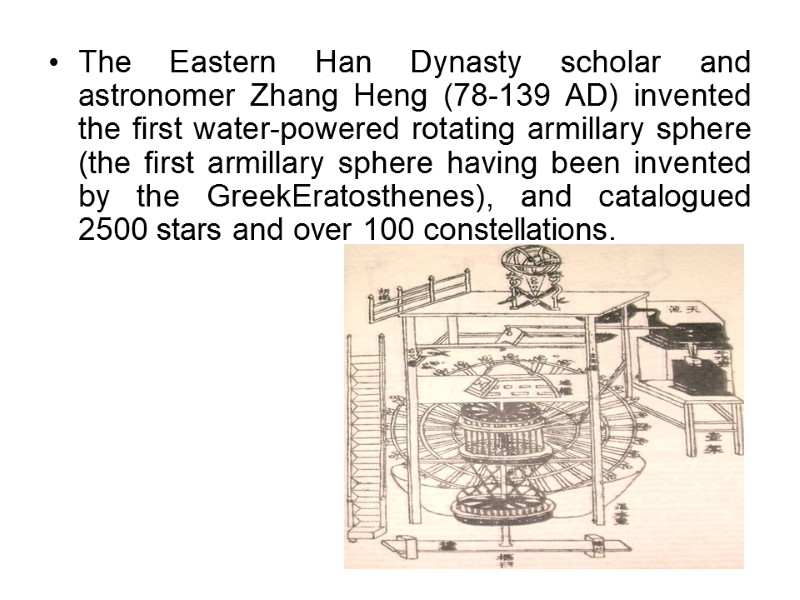

The Eastern Han Dynasty scholar and astronomer Zhang Heng (78-139 AD) invented the first water-powered rotating armillary sphere (the first armillary sphere having been invented by the GreekEratosthenes), and catalogued 2500 stars and over 100 constellations.

The Eastern Han Dynasty scholar and astronomer Zhang Heng (78-139 AD) invented the first water-powered rotating armillary sphere (the first armillary sphere having been invented by the GreekEratosthenes), and catalogued 2500 stars and over 100 constellations.

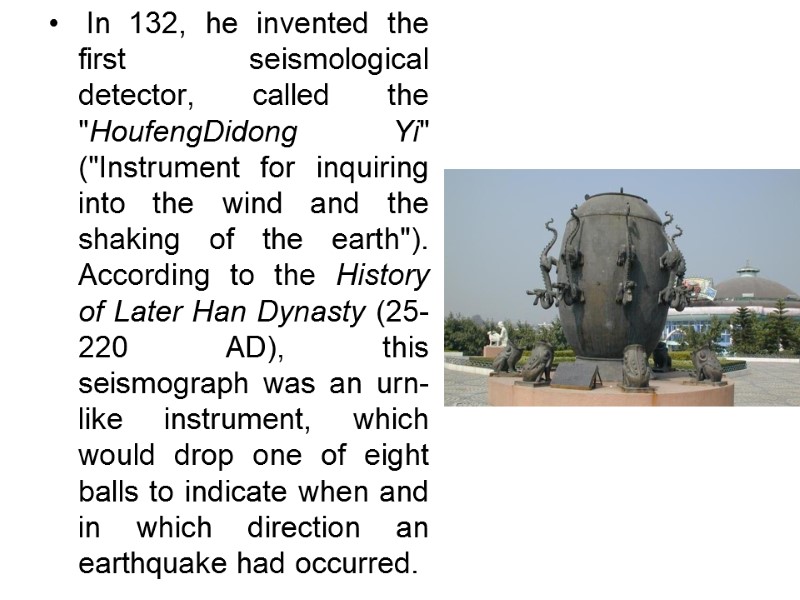

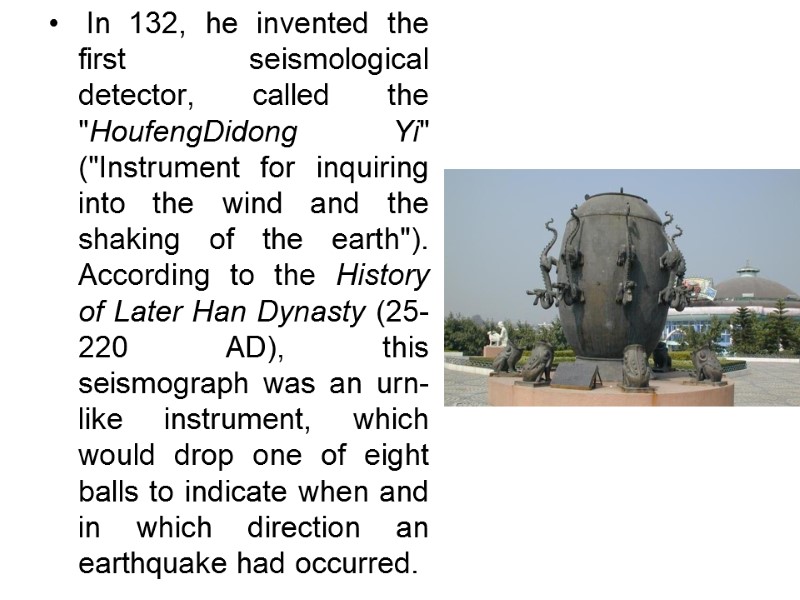

In 132, he invented the first seismological detector, called the "HoufengDidong Yi" ("Instrument for inquiring into the wind and the shaking of the earth"). According to the History of Later Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), this seismograph was an urn-like instrument, which would drop one of eight balls to indicate when and in which direction an earthquake had occurred.

In 132, he invented the first seismological detector, called the "HoufengDidong Yi" ("Instrument for inquiring into the wind and the shaking of the earth"). According to the History of Later Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), this seismograph was an urn-like instrument, which would drop one of eight balls to indicate when and in which direction an earthquake had occurred.

The mechanical engineer Ma Jun (c.200-265 AD) was another impressive figure from ancient China. most impressive invention was the south-pointing chariot, a complex mechanical device that acted as a mechanical compass vehicle. It incorporated the use of a differential gear in order to apply equal amount of momentum to wheels rotating at different speeds, a device that is found in all modern automobiles

The mechanical engineer Ma Jun (c.200-265 AD) was another impressive figure from ancient China. most impressive invention was the south-pointing chariot, a complex mechanical device that acted as a mechanical compass vehicle. It incorporated the use of a differential gear in order to apply equal amount of momentum to wheels rotating at different speeds, a device that is found in all modern automobiles

The Chinese civilization was the earliest civilization to experiment successfully with aviation, with the kite and Kongming lantern (proto Hot air balloon) being the first flying machines.

The Chinese civilization was the earliest civilization to experiment successfully with aviation, with the kite and Kongming lantern (proto Hot air balloon) being the first flying machines.

The "Four Great Inventions" (simplified Chinese: 四大发明; traditional Chinese: 四大發明; pinyin: sìdàfāmíng) are the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and printing. Paper and printing were developed first.

The "Four Great Inventions" (simplified Chinese: 四大发明; traditional Chinese: 四大發明; pinyin: sìdàfāmíng) are the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and printing. Paper and printing were developed first.

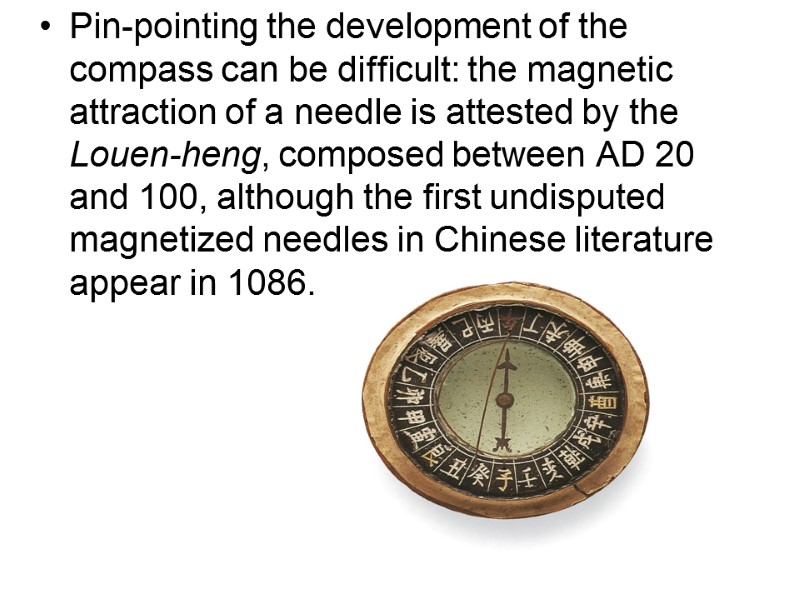

Pin-pointing the development of the compass can be difficult: the magnetic attraction of a needle is attested by the Louen-heng, composed between AD 20 and 100, although the first undisputed magnetized needles in Chinese literature appear in 1086.

Pin-pointing the development of the compass can be difficult: the magnetic attraction of a needle is attested by the Louen-heng, composed between AD 20 and 100, although the first undisputed magnetized needles in Chinese literature appear in 1086.

By AD 300, Ge Hong, an alchemist of the Jin Dynasty, conclusively recorded the chemical reactions caused when saltpetre, pine resin and charcoal were heated together, in Book of the Master of the Preservations of Solidarity. Another early record of gunpowder, a Chinese book from c. 850 AD, indicates: "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down."

By AD 300, Ge Hong, an alchemist of the Jin Dynasty, conclusively recorded the chemical reactions caused when saltpetre, pine resin and charcoal were heated together, in Book of the Master of the Preservations of Solidarity. Another early record of gunpowder, a Chinese book from c. 850 AD, indicates: "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down."

These four discoveries had an enormous impact on the development of Chinese civilization and a far-ranging global impact. Gunpowder, for example, spread to the Arabs in the 13th century and thence to Europe.

These four discoveries had an enormous impact on the development of Chinese civilization and a far-ranging global impact. Gunpowder, for example, spread to the Arabs in the 13th century and thence to Europe.

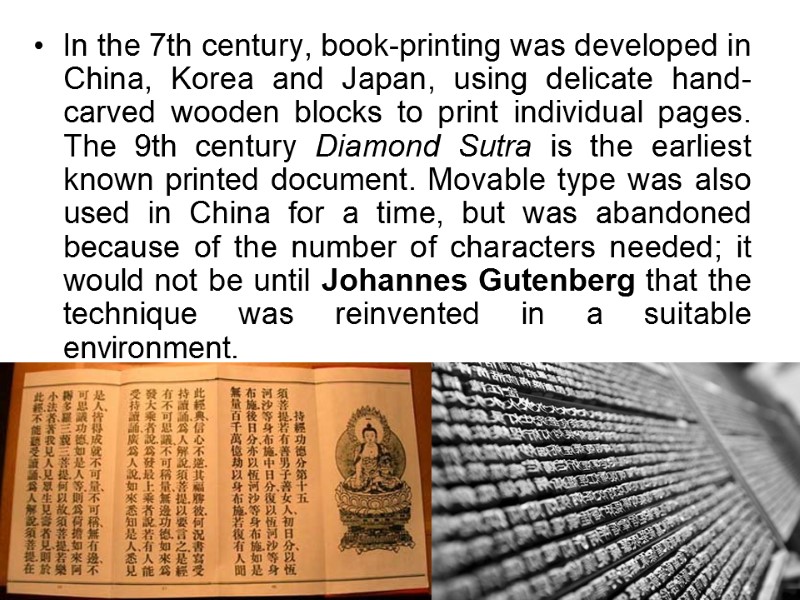

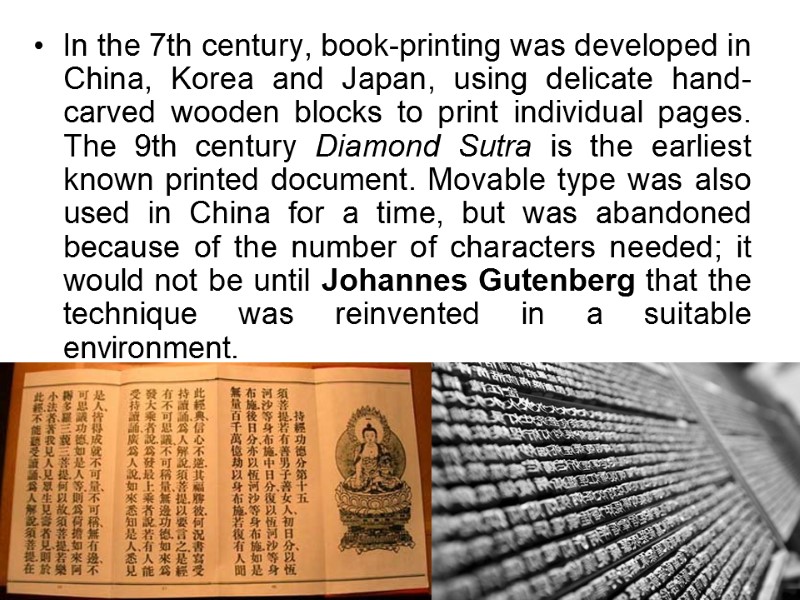

In the 7th century, book-printing was developed in China, Korea and Japan, using delicate hand-carved wooden blocks to print individual pages. The 9th century Diamond Sutra is the earliest known printed document. Movable type was also used in China for a time, but was abandoned because of the number of characters needed; it would not be until Johannes Gutenberg that the technique was reinvented in a suitable environment.

In the 7th century, book-printing was developed in China, Korea and Japan, using delicate hand-carved wooden blocks to print individual pages. The 9th century Diamond Sutra is the earliest known printed document. Movable type was also used in China for a time, but was abandoned because of the number of characters needed; it would not be until Johannes Gutenberg that the technique was reinvented in a suitable environment.

Printing, gunpowder and the compass: These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation; whence have followed innumerable changes, in so much that no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.

Printing, gunpowder and the compass: These three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation; whence have followed innumerable changes, in so much that no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.