77960b5be3b7ffc3dced0a288d432f03.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 1

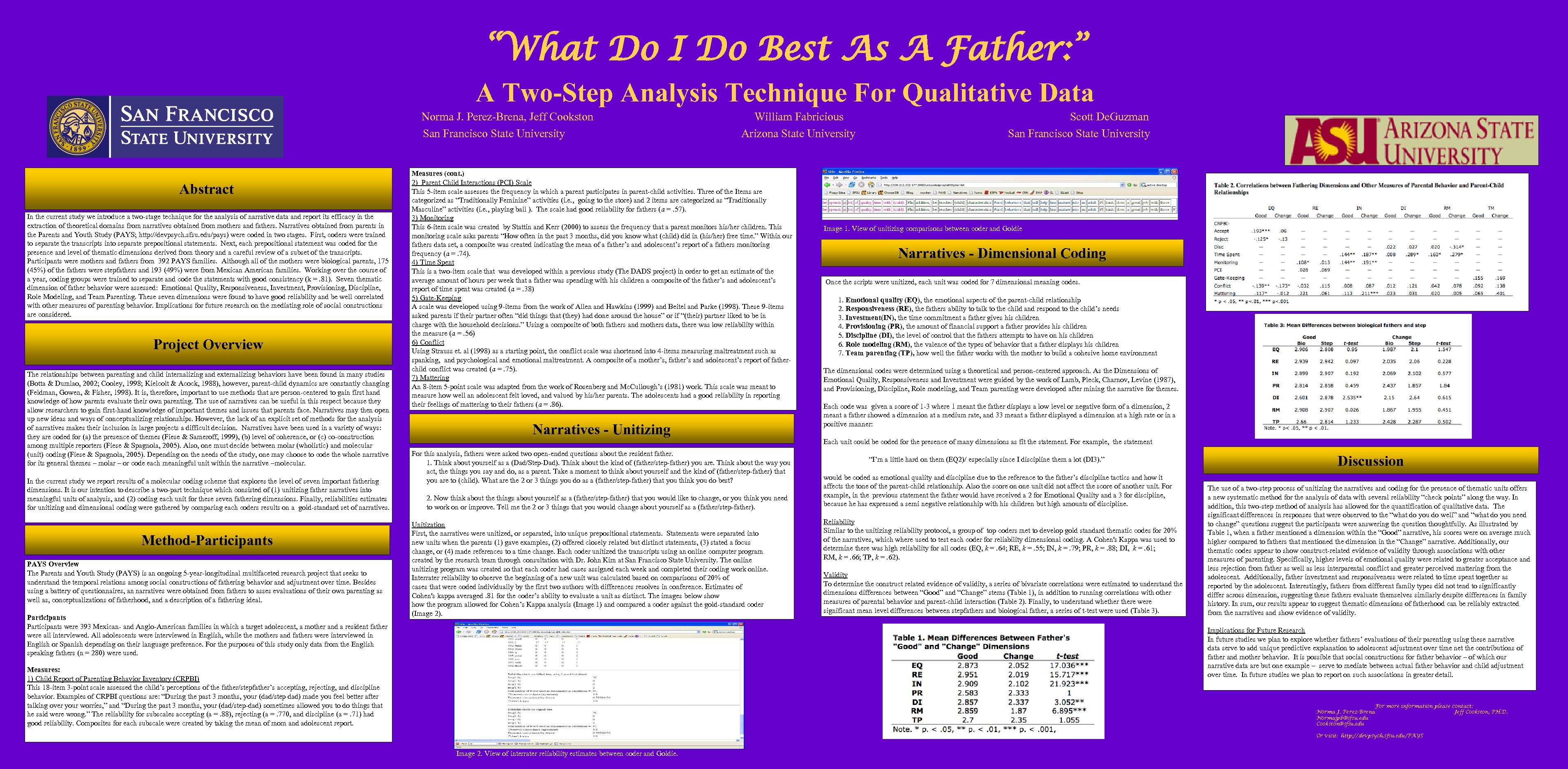

“What Do I Do Best As A Father: ” A Two-Step Analysis Technique For Qualitative Data Norma J. Perez-Brena, Jeff Cookston San Francisco State University Abstract In the current study we introduce a two-stage technique for the analysis of narrative data and report its efficacy in the extraction of theoretical domains from narratives obtained from mothers and fathers. Narratives obtained from parents in the Parents and Youth Study (PAYS; http: //devpsych. sfsu. edu/pays) were coded in two stages. First, coders were trained to separate the transcripts into separate prepositional statements. Next, each prepositional statement was coded for the presence and level of thematic dimensions derived from theory and a careful review of a subset of the transcripts. Participants were mothers and fathers from 392 PAYS families. Although all of the mothers were biological parents, 175 (45%) of the fathers were stepfathers and 193 (49%) were from Mexican American families. Working over the course of a year, coding groups were trained to separate and code the statements with good consistency (k =. 81). Seven thematic dimension of father behavior were assessed: Emotional Quality, Responsiveness, Investment, Provisioning, Discipline, Role Modeling, and Team Parenting. These seven dimensions were found to have good reliability and be well correlated with other measures of parenting behavior. Implications for future research on the mediating role of social constructions are considered. Project Overview The relationships between parenting and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors have been found in many studies (Botta & Dumlao, 2002; Cooley, 1998; Kielcolt & Acock, 1988), however, parent-child dynamics are constantly changing (Feldman, Gowen, & Fisher, 1998). It is, therefore, important to use methods that are person-centered to gain first hand knowledge of how parents evaluate their own parenting. The use of narratives can be useful in this respect because they allow researchers to gain first-hand knowledge of important themes and issues that parents face. Narratives may then open up new ideas and ways of conceptualizing relationships. However, the lack of an explicit set of methods for the analysis of narratives makes their inclusion in large projects a difficult decision. Narratives have been used in a variety of ways: they are coded for (a) the presence of themes (Fiese & Sameroff, 1999), (b) level of coherence, or (c) co-construction among multiple reporters (Fiese & Spagnola, 2005). Also, one must decide between molar (wholistic) and molecular (unit) coding (Fiese & Spagnola, 2005). Depending on the needs of the study, one may choose to code the whole narrative for its general themes – molar – or code each meaningful unit within the narrative –molecular. In the current study we report results of a molecular coding scheme that explores the level of seven important fathering dimensions. It is our intention to describe a two-part technique which consisted of (1) unitizing father narratives into meaningful units of analysis, and (2) coding each unit for these seven fathering dimensions. Finally, reliabilities estimates for unitizing and dimensional coding were gathered by comparing each coders results on a gold-standard set of narratives. Method-Participants PAYS Overview The Parents and Youth Study (PAYS) is an ongoing 5 -year-longitudinal multifaceted research project that seeks to understand the temporal relations among social constructions of fathering behavior and adjustment over time. Besides using a battery of questionnaires, an narratives were obtained from fathers to asses evaluations of their own parenting as well as, conceptualizations of fatherhood, and a description of a fathering ideal. Participants were 393 Mexican- and Anglo-American families in which a target adolescent, a mother and a resident father were all interviewed. All adolescents were interviewed in English, while the mothers and fathers were interviewed in English or Spanish depending on their language preference. For the purposes of this study only data from the English speaking fathers (n = 280) were used. William Fabricious Arizona State University Measures (cont. ) 2) Parent Child Interactions (PCI) Scale This 5 -item scale assesses the frequency in which a parent participates in parent-child activities. Three of the Items are categorized as “Traditionally Feminine” activities (i. e. , going to the store) and 2 items are categorized as “Traditionally Masculine” activities (i. e. , playing ball ). The scale had good reliability for fathers (a =. 57). 3) Monitoring This 6 -item scale was created by Stattin and Kerr (2000) to assess the frequency that a parent monitors his/her children. This monitoring scale asks parents “How often in the past 3 months, did you know what (child) did in (his/her) free time. ” Within our fathers data set, a composite was created indicating the mean of a father’s and adolescent’s report of a fathers monitoring frequency (a =. 74). 4) Time Spent This is a two-item scale that was developed within a previous study (The DADS project) in order to get an estimate of the average amount of hours per week that a father was spending with his children a composite of the father’s and adolescent’s report of time spent was created (a =. 38) 5) Gate-Keeping A scale was developed using 9 -items from the work of Allen and Hawkins (1999) and Beitel and Parke (1998). These 9 -items asked parents if their partner often “did things that (they) had done around the house” or if “(their) partner liked to be in charge with the household decisions. ” Using a composite of both fathers and mothers data, there was low reliability within the measure (a =. 56) 6) Conflict Using Strauss et. al (1998) as a starting point, the conflict scale was shortened into 4 -items measuring maltreatment such as spanking, and psychological and emotional maltreatment. A composite of a mother’s, father’s and adolescent’s report of fatherchild conflict was created (a =. 75). 7) Mattering An 8 -item 5 -point scale was adapted from the work of Rosenberg and Mc. Cullough’s (1981) work. This scale was meant to measure how well an adolescent felt loved, and valued by his/her parents. The adolescents had a good reliability in reporting their feelings of mattering to their fathers (a =. 86). Narratives - Unitizing Scott De. Guzman San Francisco State University Image 1. View of unitizing comparisons between coder and Goldie Narratives - Dimensional Coding Once the scripts were unitized, each unit was coded for 7 dimensional meaning codes. 1. Emotional quality (EQ), the emotional aspects of the parent-child relationship 2. Responsiveness (RE), the fathers ability to talk to the child and respond to the child’s needs 3. Investment(IN), the time commitment a father gives his children 4. Provisioning (PR), the amount of financial support a father provides his children 5. Discipline (DI), the level of control that the fathers attempts to have on his children 6. Role modeling (RM), the valence of the types of behavior that a father displays his children 7. Team parenting (TP), how well the father works with the mother to build a cohesive home environment The dimensional codes were determined using a theoretical and person-centered approach. As the Dimensions of Emotional Quality, Responsiveness and Investment were guided by the work of Lamb, Pleck, Charnov, Levine (1987), and Provisioning, Discipline, Role modeling, and Team parenting were developed after mining the narrative for themes. Each code was given a score of 1 -3 where 1 meant the father displays a low level or negative form of a dimension, 2 meant a father showed a dimension at a medium rate, and 33 meant a father displayed a dimension at a high rate or in a positive manner: Each unit could be coded for the presence of many dimensions as fit the statement. For example, the statement For this analysis, fathers were asked two open-ended questions about the resident father. 1. Think about yourself as a (Dad/Step-Dad). Think about the kind of (father/step-father) you are. Think about the way you act, the things you say and do, as a parent. Take a moment to think about yourself and the kind of (father/step-father) that you are to (child). What are the 2 or 3 things you do as a (father/step-father) that you think you do best? 2. Now think about the things about yourself as a (father/step-father) that you would like to change, or you think you need to work on or improve. Tell me the 2 or 3 things that you would change about yourself as a (father/step-father). Unitization First, the narratives were unitized, or separated, into unique prepositional statements. Statements were separated into new units when the parents (1) gave examples, (2) offered closely related but distinct statements, (3) stated a focus change, or (4) made references to a time change. Each coder unitized the transcripts using an online computer program created by the research team through consultation with Dr. John Kim at San Francisco State University. The online unitizing program was created so that each coder had cases assigned each week and completed their coding work online. Interrater reliability to observe the beginning of a new unit was calculated based on comparisons of 20% of cases that were coded individually by the first two authors with differences resolves in conference. Estimates of Cohen's kappa averaged. 81 for the coder’s ability to evaluate a unit as distinct. The images below show the program allowed for Cohen’s Kappa analysis (Image 1) and compared a coder against the gold-standard coder (Image 2). “I’m a little hard on them (EQ 2)/ especially since I discipline them a lot (DI 3). ” would be coded as emotional quality and discipline due to the reference to the father’s discipline tactics and how it affects the tone of the parent-child relationship. Also the score on one unit did not affect the score of another unit. For example, in the previous statement the father would have received a 2 for Emotional Quality and a 3 for discipline, because he has expressed a semi negative relationship with his children but high amounts of discipline. Reliability Similar to the unitizing reliability protocol, a group of top coders met to develop gold standard thematic codes for 20% of the narratives, which where used to test each coder for reliability dimensional coding. A Cohen's Kappa was used to determine there was high reliability for all codes (EQ, k =. 64; RE, k =. 55; IN, k =. 79; PR, k =. 88; DI, k =. 61; RM, k =. 66; TP, k =. 62). Validity To determine the construct related evidence of validity, a series of bivariate correlations were estimated to understand the dimensions differences between “Good” and “Change” stems (Table 1), in addition to running correlations with other measures of parental behavior and parent-child interaction (Table 2). Finally, to understand whethere were significant mean level differences between stepfathers and biological father, a series of t-test were used (Table 3). Discussion The use of a two-step process of unitizing the narratives and coding for the presence of thematic units offers a new systematic method for the analysis of data with several reliability “check points” along the way. In addition, this two-step method of analysis has allowed for the quantification of qualitative data. The significant differences in responses that were observed to the “what do you do well” and “what do you need to change” questions suggest the participants were answering the question thoughtfully. As illustrated by Table 1, when a father mentioned a dimension within the “Good” narrative, his scores were on average much higher compared to fathers that mentioned the dimension in the “Change” narrative. Additionally, our thematic codes appear to show construct-related evidence of validity through associations with other measures of parenting. Specifically, higher levels of emotional quality were related to greater acceptance and less rejection from father as well as less interparental conflict and greater perceived mattering from the adolescent. Additionally, father investment and responsiveness were related to time spent together as reported by the adolescent. Interestingly, fathers from different family types did not tend to significantly differ across dimension, suggesting these fathers evaluate themselves similarly despite differences in family history. In sum, our results appear to suggest thematic dimensions of fatherhood can be reliably extracted from the narratives and show evidence of validity. Implications for Future Research In future studies we plan to explore whether fathers’ evaluations of their parenting using these narrative data serve to add unique predictive explanation to adolescent adjustment over time net the contributions of father and mother behavior. It is possible that social constructions for father behavior – of which our narrative data are but one example – serve to mediate between actual father behavior and child adjustment over time. In future studies we plan to report on such associations in greater detail. Measures: 1) Child Report of Parenting Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) This 18 -item 3 -point scale assessed the child’s perceptions of the father/stepfather’s accepting, rejecting, and discipline behavior. Examples of CRPBI questions are: “During the past 3 months, your (dad/step dad) made you feel better after talking over your worries, ” and “During the past 3 months, your (dad/step-dad) sometimes allowed you to do things that he said were wrong. ” The reliability for subscales accepting (a =. 88), rejecting (a =. 770, and discipline (a =. 71) had good reliability. Composites for each subscale were created by taking the mean of mom and adolescent report. For more information please contact: Norma J. Perez-Brena Jeff Cookston, PH. D. Normajpb@sfsu. edu Cookston@sfsu. edu Or visit: http; //devpsych. sfsu. edu/PAYS Image 2. View of interrater reliability estimates between coder and Goldie.

77960b5be3b7ffc3dced0a288d432f03.ppt