3ce084ad1a905f73bbc19e17e5295157.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 69

Week 7 Monday, October 10 • Knowledge Management • Managing Operations R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 1

Knowledge and Expertise as a Resource Capturing Knowledge through IT R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 2

Knowledge as a Resource • Information that is contextual, relevant and actionable • Used for problem solving – Applied in a context Meaningful and valuable, – Relevant to the task but ephemeral (i. e. , transitory) – Used to support an action • Fuzzy and loosely coupled – Must be understood within a context – Foundational resource – Implied understanding of its use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 3

Types of Knowledge • • Descriptive – knowing what Procedural – knowing how Reasoning – knowing why Presentation – knowing how to communicate or deliver knowledge – Linguistic – knowing how to interpret communication • Assimilative – knowing how to maintain knowledge by improving existing knowledge R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Basic knowledge Communicating, understanding and learning 4

Characteristics of Knowledge • Ground truth grained from experience, not theory • Complexity as applied to problem solving – Simplification of problem space • Judgment puts knowledge in actionable form • Heuristic and intuitive approaches to problem solving • Value and beliefs applied to defining the problem space R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 5

Decision Making • Modeling the problem Inputs Process Output – – Represents the real thing Identifies the components and their interactions Specifies the behavior Predicts the outcome based on an established process given a set of inputs R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 6

What is an Expert System? • “An expert system is an intelligent computer program that uses knowledge and inference procedures to solve problems that are difficult enough to require significant human expertise for their solution. The knowledge to perform at such a level plus the inference procedures used, can be thought of as a model of the expertise of the best practitioners of the field. ” Feigenbaum (1983) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 7

Benefits of Expert Systems (Turban) • • • Increased output and productivity Increased quality Reduced down time Capturing scarce expertise Flexibility Equipment operation Using less expensive equipment Operation in hazardous environments Reliability R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 8

Benefits of Expert Systems Cont. • Response time • Integration of several experts' opinions • Working with incomplete and uncertain information Turban (1990) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 9

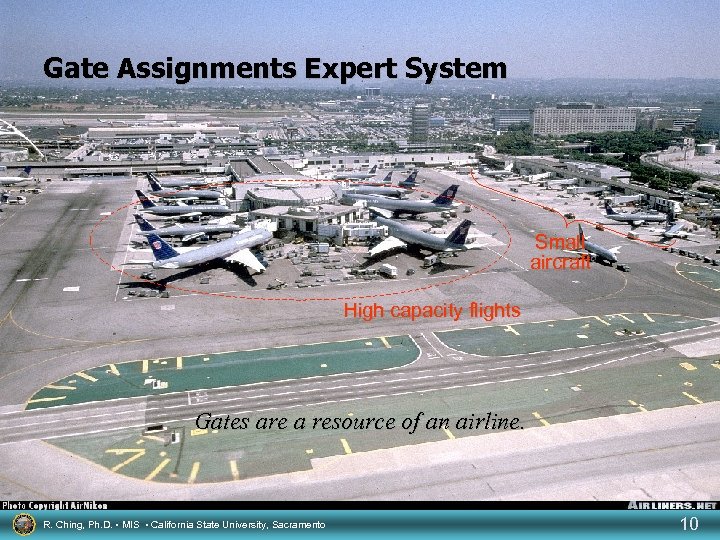

Gate Assignments Expert System Small aircraft High capacity flights Gates are a resource of an airline. R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 10

Boeing 747: 347 passengers Boeing 767: 193 -244 passengers Boeing 777: 276 -348 passengers Boeing 757: 181 passengers Airbus A 319/320: 120 -138 passengers R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Boeing 737: 110 -120 passengers 11

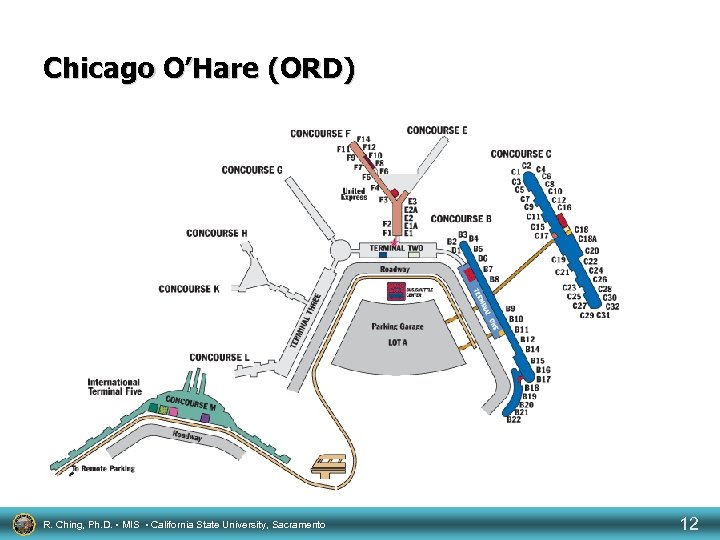

Chicago O’Hare (ORD) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 12

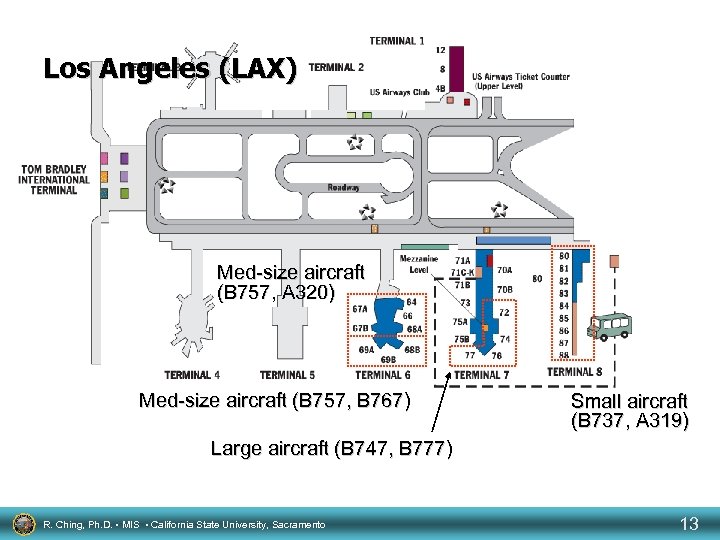

Los Angeles (LAX) Med-size aircraft (B 757, A 320) Med-size aircraft (B 757, B 767) Small aircraft (B 737, A 319) Large aircraft (B 747, B 777) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 13

Constraints • • Certain aircraft can fit only certain gates Minimize traffic in an area Minimize distance between aircraft for connecting flights Delays due to weather, mechanical problems, aircraft servicing, arrivals and others have an impact on the assignments • International flights cannot park at a domestic gate R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 14

When to Use an Expert System • • • High potential payoff or significantly reduced downside risk Ability to capture and preserve irreplaceable human expertise Ability to develop a system more consistent than human experts • Expertise is needed at a number of locations at the same time • Expertise is needed in a hostile environment that is dangerous to human health R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 15

When to Use an Expert System Cont. • The expert system solution can be developed faster than the solution from human experts • An expert system is needed for training and development so as to share the wisdom and experience of human experts with a large number of people Turban, 1995 R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 16

Problems in Knowledge Acquisition • • • Expressing the knowledge Transfer to machine Number of participants – – Expert Knowledge engineer System designer User • Structuring knowledge – Representing knowledge R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 17

Problems in Knowledge Acquisition Cont. • Others – – Experts may lack time or may be unwilling to cooperate Testing and refining knowledge is complicated Methods for knowledge elicitation may be poorly defined System builders have a tendency to collect knowledge from one source, but the relevant knowledge may be scattered across several sources – Builders may attempt to collect documented knowledge rather than using experts R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 18

Problems in Knowledge Acquisition Cont. • Others – It is difficult to recognize specific knowledge when it is mixed up with irrelevant data – Experts may change their behavior when they are being observed and/or interviewed – Problematic interpersonal communication factors may exist between the KE and the expert Turban, 1995 R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 19

Knowledge Engineering Bottleneck • Eliciting expertise from an expert: – Costly – Error Prone – Time Consuming • "Gaps" in the expert's knowledge • Inability to articulate knowledge – "The ability to function at an expert level in a task domain does not necessarily confer a corresponding ability to articulate this know-how. " Quinlan (1987) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 20

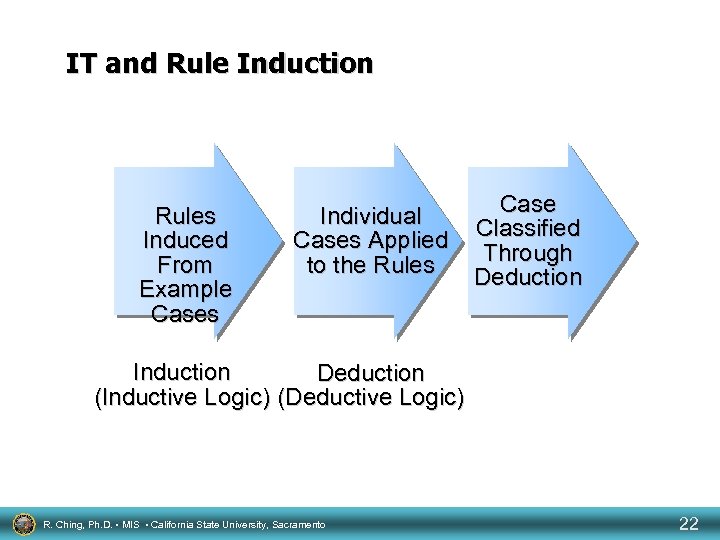

Rule Induction • ". . . process of reasoning from the specific to the general. In ES terminology it refers to the process in which rules are generated by a computer program from example cases. " Turban, 1990 R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 21

IT and Rule Induction Rules Induced From Example Cases Individual Cases Applied to the Rules Case Classified Through Deduction Induction Deduction (Inductive Logic) (Deductive Logic) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 22

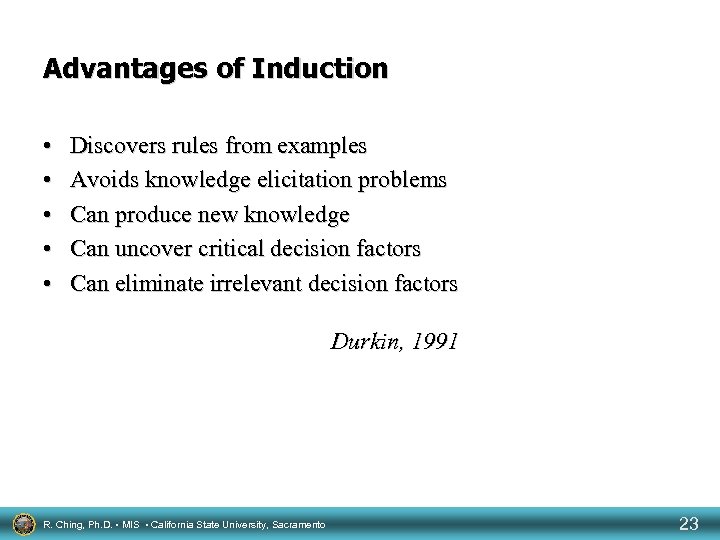

Advantages of Induction • • • Discovers rules from examples Avoids knowledge elicitation problems Can produce new knowledge Can uncover critical decision factors Can eliminate irrelevant decision factors Durkin, 1991 R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 23

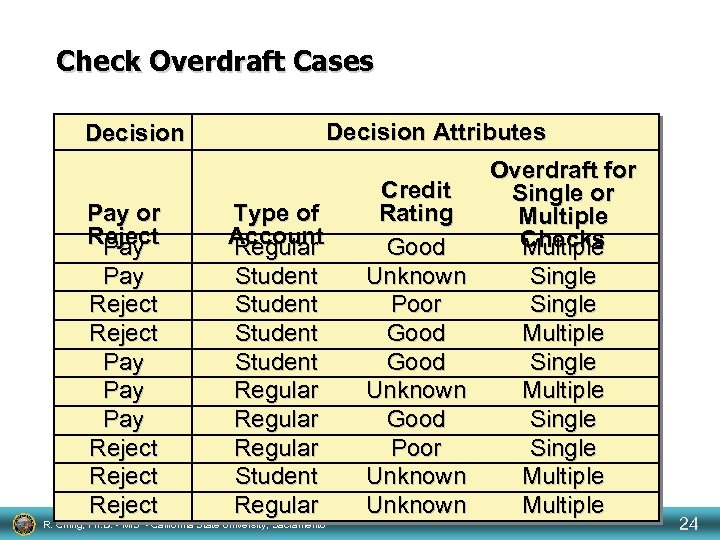

Check Overdraft Cases Decision Attributes Decision Pay or Reject Pay Pay Reject Type of Account Regular Student Regular Student Regular R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Credit Rating Good Unknown Poor Good Unknown Good Poor Unknown Overdraft for Single or Multiple Checks Multiple Single Single Multiple 24

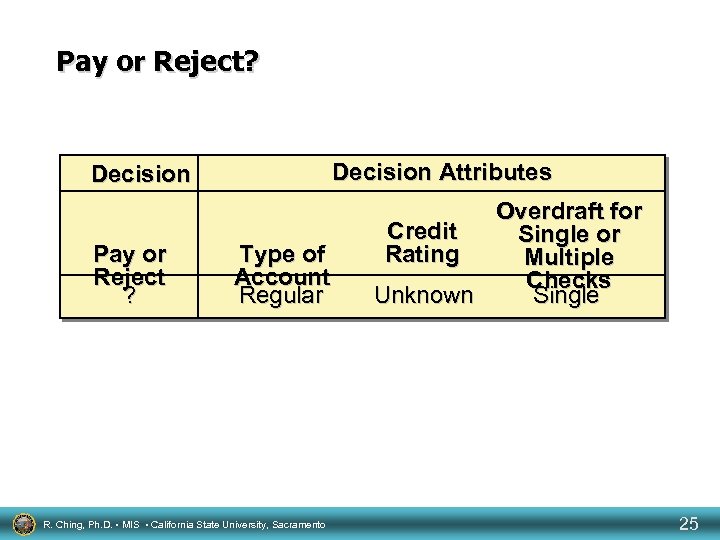

Pay or Reject? Decision Attributes Decision Pay or Reject ? Type of Account Regular R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Overdraft for Credit Single or Rating Multiple Checks Unknown Single 25

Decision Trees • A decision tree is a representation of a decision procedure for determining the class of a given instance. Each node of the tree specifies either a class name or a specific test that partitions the space of instances at the node according to the possible outcomes of the test. Each subset of the partition corresponds to a classification subproblem for that subspace of the instances which is solved by a tree. Utgoff, 1989 R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 26

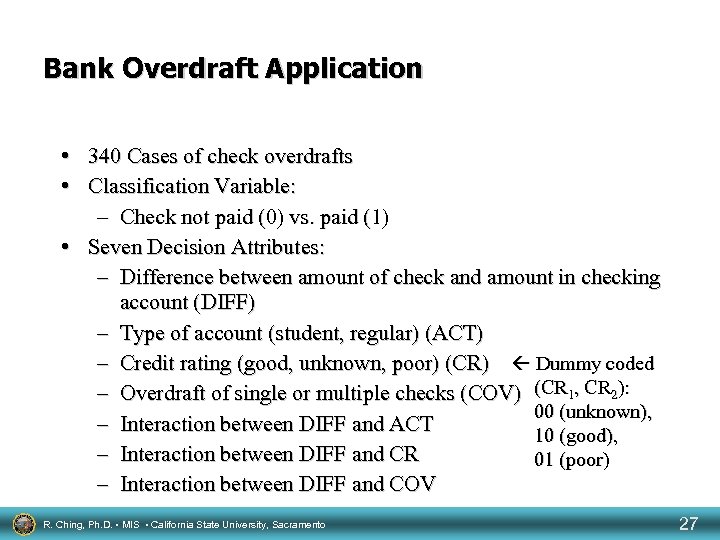

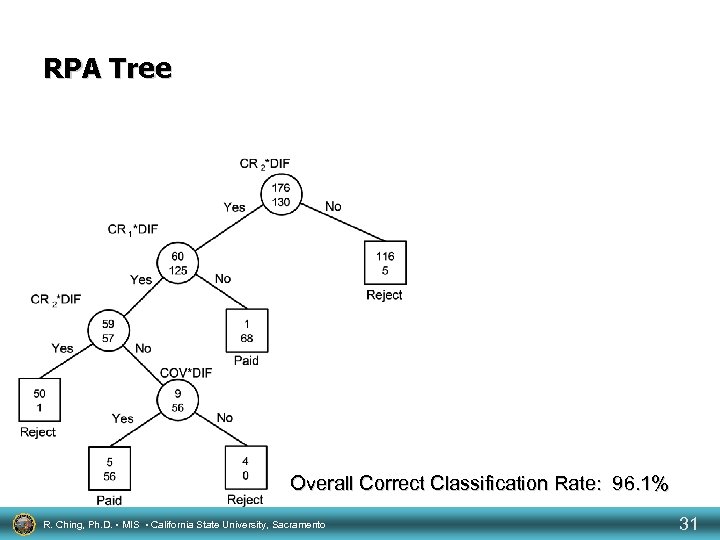

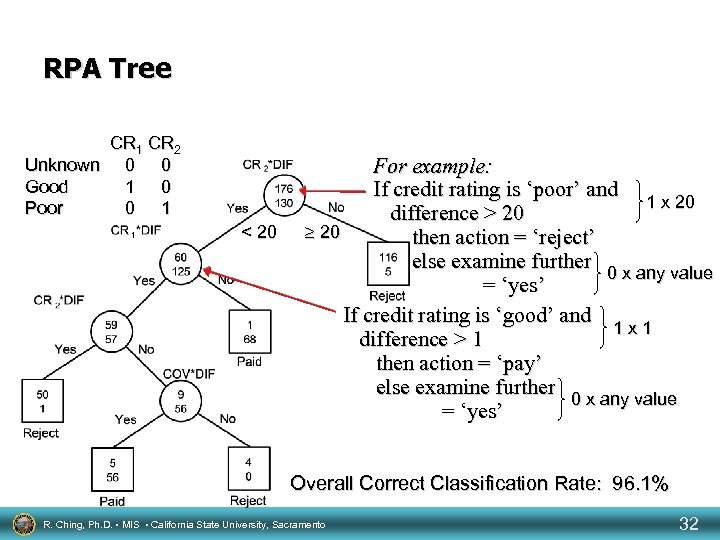

Bank Overdraft Application • 340 Cases of check overdrafts • Classification Variable: – Check not paid (0) vs. paid (1) • Seven Decision Attributes: – Difference between amount of check and amount in checking account (DIFF) – Type of account (student, regular) (ACT) – Credit rating (good, unknown, poor) (CR) Dummy coded – Overdraft of single or multiple checks (COV) (CR 1, CR 2): 00 (unknown), – Interaction between DIFF and ACT 10 (good), – Interaction between DIFF and CR 01 (poor) – Interaction between DIFF and COV R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 27

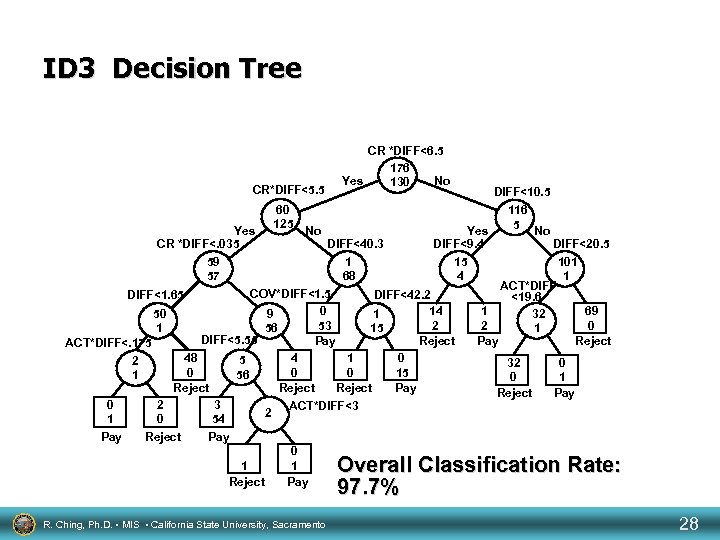

ID 3 Decision Tree CR*DIFF<5. 5 CR *DIFF<6. 5 176 Yes No 130 DIFF<10. 5 60 116 125 5 No Yes CR *DIFF<. 035 DIFF<40. 3 DIFF<9. 4 DIFF<20. 5 59 1 15 101 57 68 4 1 ACT*DIFF COV*DIFF<1. 5 DIFF<42. 2 DIFF<1. 65 <19. 6 0 14 1 69 50 9 1 32 53 2 2 0 1 56 15 1 DIFF<5. 55 Pay Reject ACT*DIFF<. 175 48 4 1 0 5 2 32 0 0 15 56 1 0 1 Reject Pay 2 3 0 ACT*DIFF<3 2 0 54 1 2 Pay Reject Pay 2 0 1 1 Reject Pay Overall Classification Rate: 97. 7% R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 28

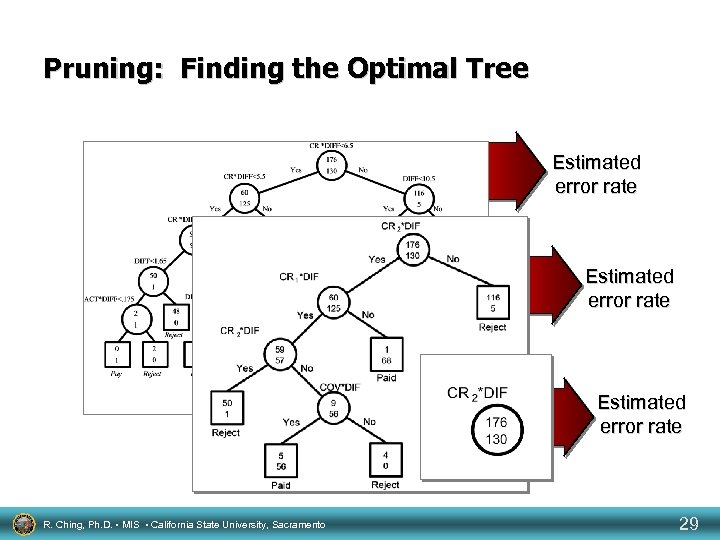

Pruning: Finding the Optimal Tree Estimated error rate R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 29

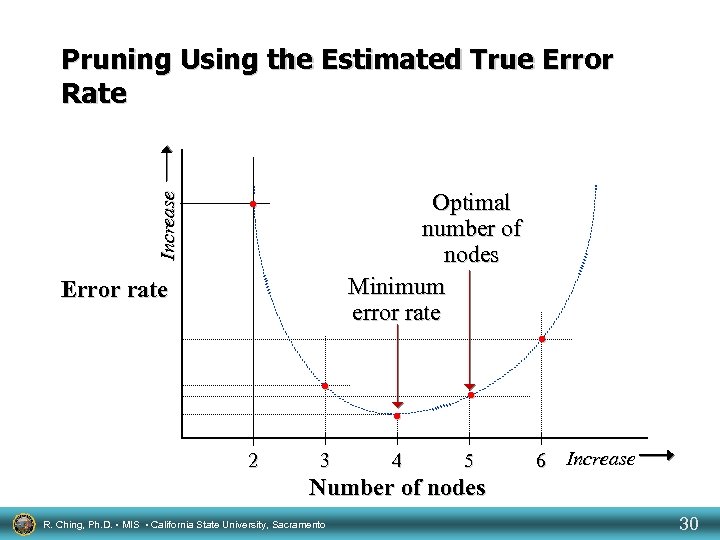

Increase Pruning Using the Estimated True Error Rate Optimal number of nodes Minimum error rate • Error rate • • 2 3 4 • • 5 6 Increase Number of nodes R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 30

RPA Tree Overall Correct Classification Rate: 96. 1% R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 31

RPA Tree CR 1 CR 2 Unknown 0 0 Good 1 0 Poor 0 1 < 20 For example: If credit rating is ‘poor’ and 1 x 20 difference > 20 then action = ‘reject’ else examine further 0 x any value = ‘yes’ If credit rating is ‘good’ and 1 x 1 difference > 1 then action = ‘pay’ else examine further 0 x any value = ‘yes’ Overall Correct Classification Rate: 96. 1% R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 32

Another Example… R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 33

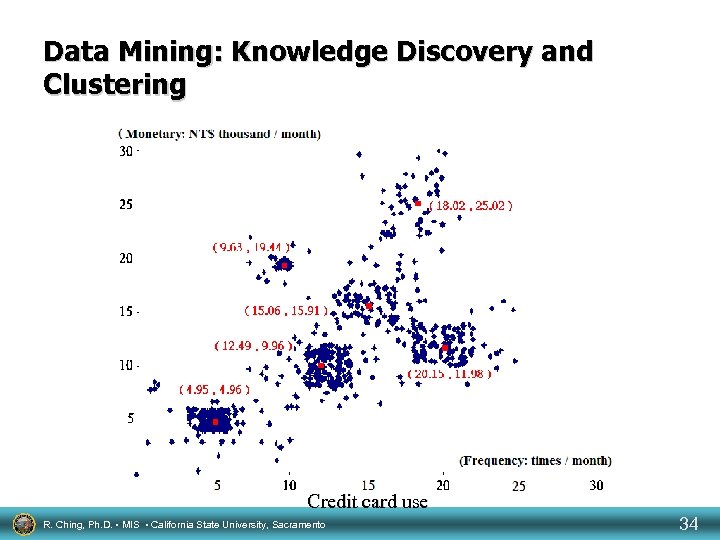

Data Mining: Knowledge Discovery and Clustering Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 34

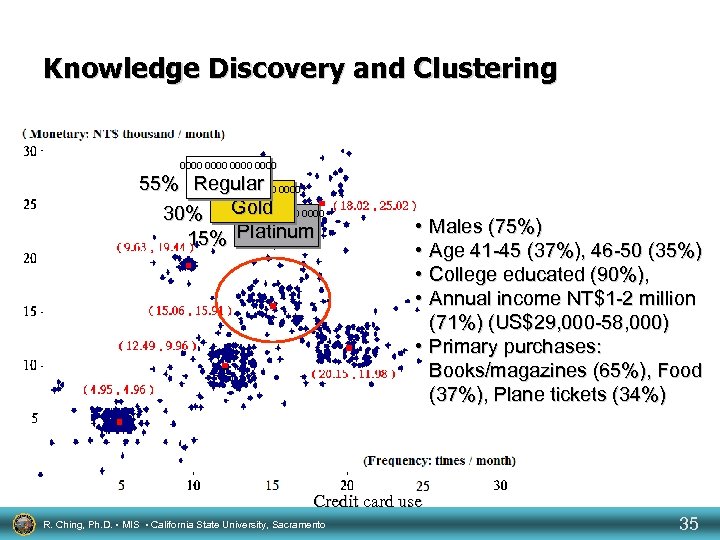

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering 0000 55% Regular 0000 Gold 30% 0000 15% Platinum • Males (75%) • Age 41 -45 (37%), 46 -50 (35%) • College educated (90%), • Annual income NT$1 -2 million (71%) (US$29, 000 -58, 000) • Primary purchases: Books/magazines (65%), Food (37%), Plane tickets (34%) Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 35

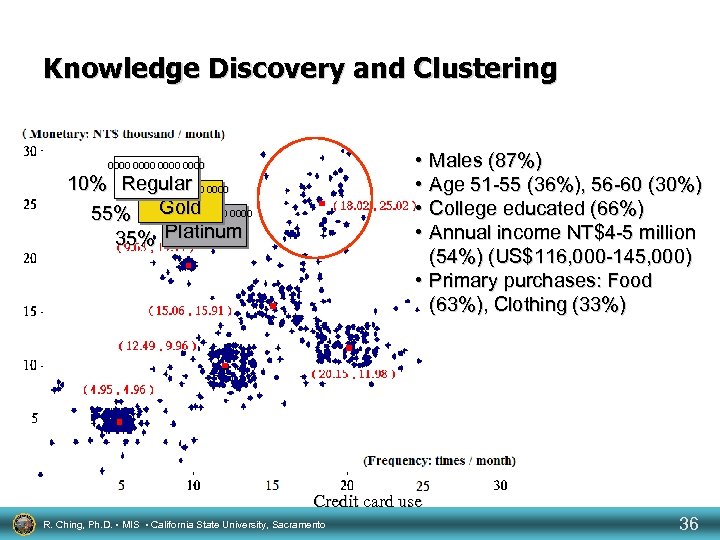

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering • Males (87%) • Age 51 -55 (36%), 56 -60 (30%) • College educated (66%) • Annual income NT$4 -5 million (54%) (US$116, 000 -145, 000) • Primary purchases: Food (63%), Clothing (33%) 0000 10% Regular 0000 Gold 55% 0000 35% Platinum Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 36

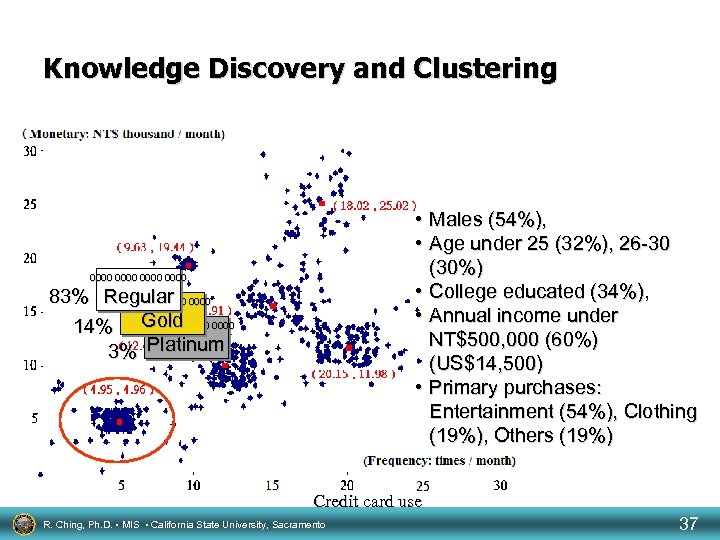

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering • Males (54%), • Age under 25 (32%), 26 -30 (30%) • College educated (34%), • Annual income under NT$500, 000 (60%) (US$14, 500) • Primary purchases: Entertainment (54%), Clothing (19%), Others (19%) 0000 83% Regular 0000 Gold 14% 0000 3% Platinum Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 37

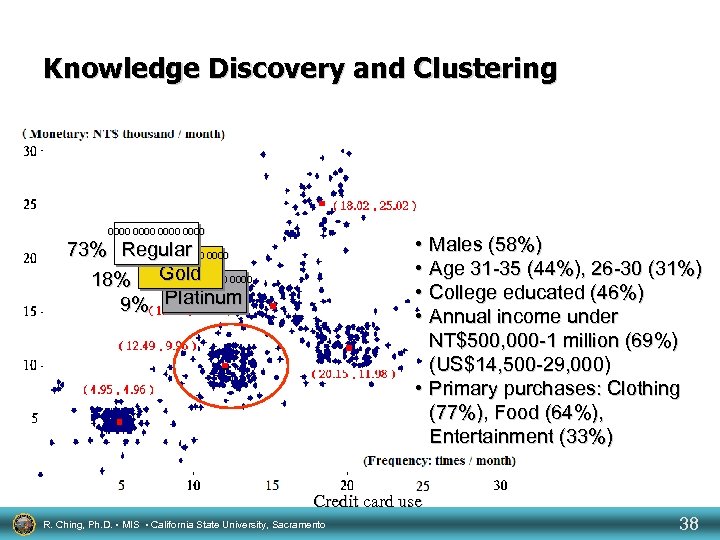

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering 0000 • Males (58%) • Age 31 -35 (44%), 26 -30 (31%) • College educated (46%) • Annual income under NT$500, 000 -1 million (69%) (US$14, 500 -29, 000) • Primary purchases: Clothing (77%), Food (64%), Entertainment (33%) 73% Regular 0000 Gold 18% 0000 9% Platinum Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 38

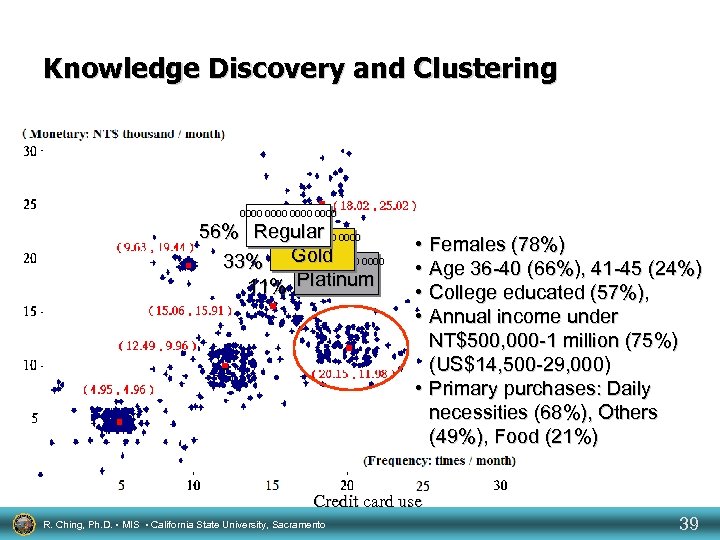

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering 0000 56% Regular 0000 Gold 33% 0000 11% Platinum • Females (78%) • Age 36 -40 (66%), 41 -45 (24%) • College educated (57%), • Annual income under NT$500, 000 -1 million (75%) (US$14, 500 -29, 000) • Primary purchases: Daily necessities (68%), Others (49%), Food (21%) Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 39

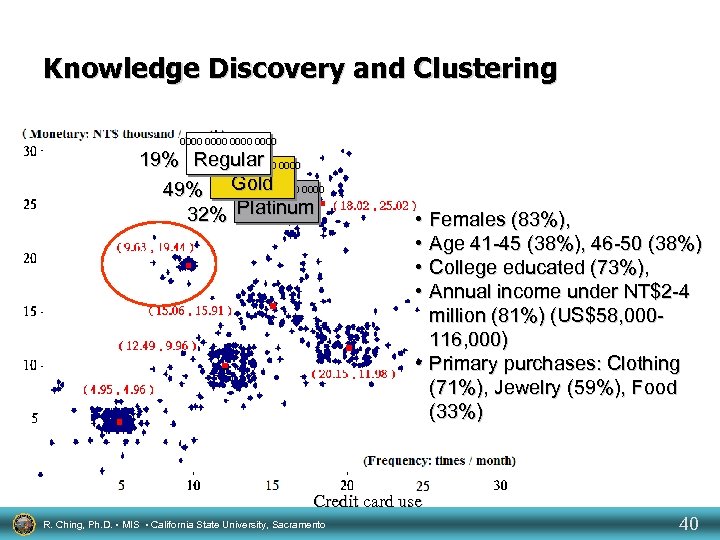

Knowledge Discovery and Clustering 0000 19% Regular 0000 Gold 49% 0000 32% Platinum • Females (83%), • Age 41 -45 (38%), 46 -50 (38%) • College educated (73%), • Annual income under NT$2 -4 million (81%) (US$58, 000116, 000) • Primary purchases: Clothing (71%), Jewelry (59%), Food (33%) Credit card use R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 40

Managing Islands of Information • Networked IT infrastructure – Centralized vs. distributed • Trends – Centralized data center – Decentralized processing to business operating units – Client-server architecture • Fat-client vs. thin-client – Networked computing architecture and reengineering – Distributed IT architecture and the Internet R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 41

Operations • Managing operations includes – Solving operational problems – Defining operational measures – Applying management principles to managing the IT resources Ensuring the IT resources are accessible to and supporting the right people in and outside the organization R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 42

Major Operational Issues • • • Outsourcing IS functions Information security in the Internet age Planning for business continuity R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 43

Managing IT Outsourcing R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 44

Managing IT Outsourcing • “Goal is to improve return on assets by moving these assets off the financial books while retaining control over their use. ” Sprague and Mc. Nurlin, 1993 • Drivers: Focus and Value • Reasons for outsourcing: – Cost-effective access to specialized or occasionally needed computing power (operational) or systems development skills (development) – Avoidance of building in-house IT skills and skill sets – Access to special functional capabilities R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 45

Market Changes • Changing customer and vendor relationships • Changes that occur with movement to outsourcing – IS/IT management loses an increasing amount of control because more of the activities are turned over to outsiders – Providers take more risks as they offer more options – Providers’ margins improve as they offer more services – The importance of choosing the right provider becomes more important due to the increased risk with outsourcing R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 46

Types of Outsourcing • • • IT outsourcing – Moving entire IT function to an outsourcer Transitional outsourcing – Project-base outsourcing Best-of-breed outsourcing – Selective outsourcing Shared services – Insourcing Business process outsourcing – Outsourcing all or most of a reengineered process that has a large IT component • e-Business outsourcing – e-business function R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 47

Another view on outsourcing R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 48

Motives to Outsource • Two major factors: – Recognition of strategic alliances • Strengthening the weakest link in the chain – Finding a strong partner that complements an organization’s skills – Changes in the technology environment • New technology, new strategies Need to compete effectively R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 49

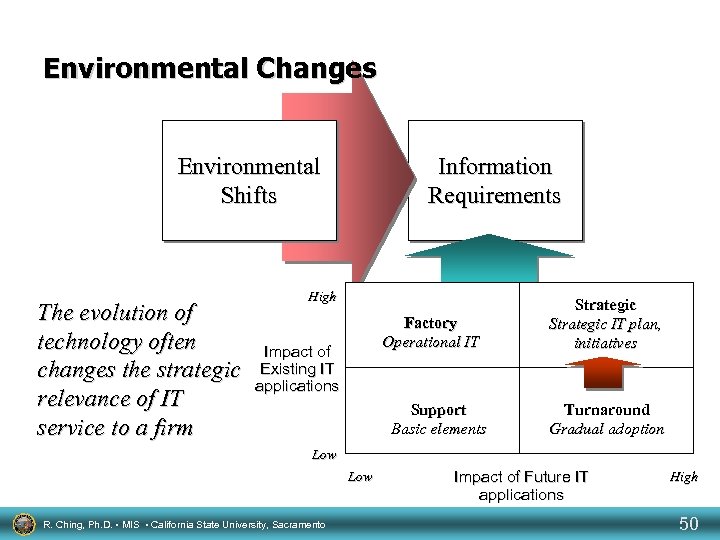

Environmental Changes Environmental Shifts The evolution of technology often changes the strategic relevance of IT service to a firm Information Requirements High Factory Operational IT Impact of Existing IT applications Support Basic elements Strategic IT plan, initiatives Turnaround Gradual adoption Low R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Impact of Future IT applications High 50

Drivers of Outsourcing • Concerns about Cost and Quality – High inhouse costs and less sensitive (to internal requirements) IT personnel • Lacking in current technology skills • Capacity utilization problems – High standards (and quality) to complete American Airlines and Sabre (coeffectively hosting) – High stakes game to hire specialized IT people – Lower costs of outsourcers (generally) – Greater responsiveness from outsourcer to IT needs of the organization R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 51

Drivers of Outsourcing • Breakdown in IT performance – Need to retool lacking technology • Intense supplier pressures – Sales of surplus supplier capacity • Simplified general management agenda – Outsource non-core competence operations • Financial factors – Reduce sporadic capital investments in IT – Downsizing IT operating costs – Greater organizational awareness of IT’s costs – More appealing for takeovers R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 52

Drivers of Outsourcing • Corporate culture – Resistance to change within the organization – Labor unions • Eliminating an internal irritant – Conflicts between users and IT staff • Other factors – Quick access to current technology and skills – Need to quickly response to changes in the market R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 53

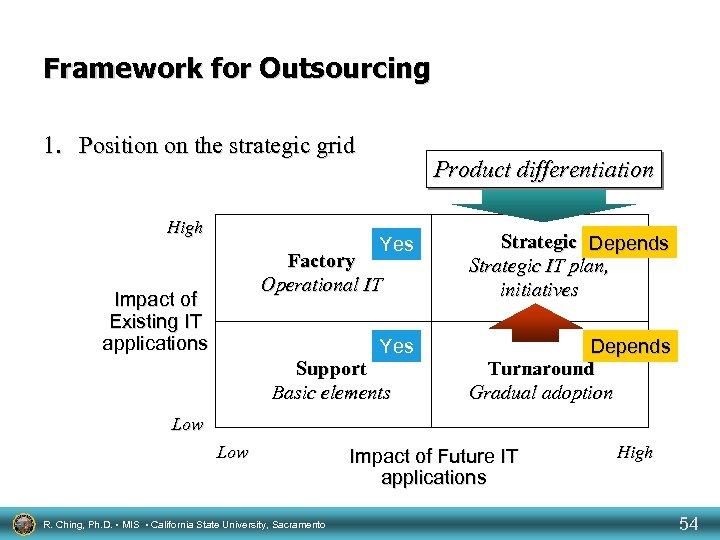

Framework for Outsourcing 1. Position on the strategic grid High Product differentiation Yes Strategic Depends Strategic IT plan, initiatives Yes Depends Turnaround Gradual adoption Factory Operational IT Impact of Existing IT applications Support Basic elements Low R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Impact of Future IT applications High 54

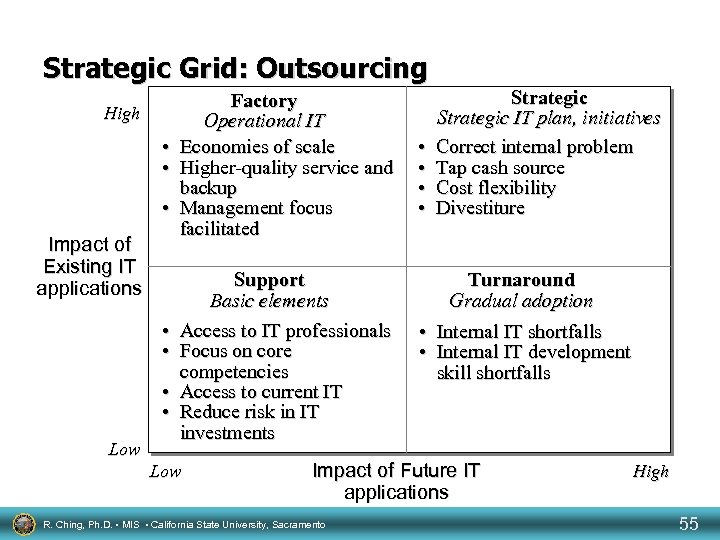

Strategic Grid: Outsourcing High Impact of Existing IT applications Factory Operational IT • Economies of scale • Higher-quality service and backup • Management focus facilitated • • Low Support Basic elements Access to IT professionals Focus on core competencies Access to current IT Reduce risk in IT investments Low • • Strategic IT plan, initiatives Correct internal problem Tap cash source Cost flexibility Divestiture Turnaround Gradual adoption • Internal IT shortfalls • Internal IT development skill shortfalls Impact of Future IT applications R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento High 55

Framework for Outsourcing 1. Position on strategic grid (cont. ) – Outsource operational activities • More operationally dependent organizations – Need for greater analysis when large IT budgets involved 2. Development portfolio – Maintenance vs. development projects • High structured vs. low structured development work R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 56

Framework for Outsourcing 3. Operational learning – Organizational assimilation of technology 4. Organization’s IT architecture and infrastructure – Currency of architecture 5. Current technology in the organization – Segregated operations more easily outsourced R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 57

Structuring the Alliance between Outsourcer and “Outsourcee” (Customer) • Factors – Contract flexibility – Standards and control – Areas to outsource – Cost savings – Supplier stability and quality – Management fit – Conversion problems R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento Alliance 58

Structuring the Alliance between Outsourcer and “Outsourcee” (Customer) • Contract flexibility – Accommodating changes in the environment • Information needs • Competitive needs • Advances in IT • Standards and control – Risk (i. e. , lost of control, disruptions) in operations – Risk in introducing innovations to the organization – Risk in revealing internal secrets R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 59

Structuring the Alliance between Outsourcer and “Outsourcee” (Customer) • Areas to outsource – Determine • Are operations segregated or tightly embedded? • Can specialized competencies be acquired in the long run? • Are operations core to the organization? • Cost savings – Objective evaluation of costs and savings R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 60

Structuring the Alliance between Outsourcer and “Outsourcee” (Customer) • Supplier Stability and Quality – Financial stability • Difficult to insource • Difficult to change outsourcers – Incompatibility between the organization and outsourcer • Technology • Organization culture • Between technology and organization’s strategy R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 61

Structuring the Alliance between Outsourcer and “Outsourcee” (Customer) • Management fit – Compatibility between management styles and cultures • Conversion problems – Mergers and acquisitions • Incompatibilities R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 62

Managing the Alliance • Critical areas: – CIO Function • Management (balance between organization and outsourcer) • Planning (vision) • Awareness of emerging technologies • Continuous adaptation (evolution) – Performance measurements • Essential standards, measurements and interpretations R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 63

Managing the Alliance – Mix and coordination of Tasks • Development versus maintenance (portfolios) – Associated risks inherent to each – Customer-outsourcer interface • Delegation of authority, not responsibility R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 64

Information Security Protecting the Information Resource • Five security pillars – Authentication – verifying the authenticity of the user • Something you know, have or are (i. e. , physical attribute) – Identification – identifying users to grant them appropriate access – Privacy – protecting information from being seen Encryption – Integrity – keeping information in its original form – Nonrepudiation – preventing parties from denying actions they have taken R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 65

Management and Technical Countermeasures Management countermeasures • Evaluate return on their security expenditures • Conduct security audits • Do not outsource cybersecurity Expense • Security awareness training Likelihood Technical countermeasures • Firewalls Balancing between expense • Encryption and likelihood of a threat • Virtual private networks (VPN) R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 66

Planning for Business Continuity • Recognize threats • Contingency plans if a threat is realized – Alternate workspaces for people to resume work – Backup IT sites – Up-to-date evacuation plans – Backed up computers and servers – Helping people cope with disaster R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 67

Internal and External Resources Internal • Multiple data centers • Distributed processing • Backup communications facilities • LANs External • Integrated disaster recovery services • Specialized disaster recovery services • Online and off-line data storage R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 68

R. Ching, Ph. D. • MIS • California State University, Sacramento 69

3ce084ad1a905f73bbc19e17e5295157.ppt