e317ff690697f2d8c812aff106409766.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 24

Week 2: Defining State Crime

Week 2: Defining State Crime

• How much money did the former Nigerian dictator, Sani Abacha, steal from his country? • • $40, 000 $400, 000 $4 million $4 billion

• How much money did the former Nigerian dictator, Sani Abacha, steal from his country? • • $40, 000 $400, 000 $4 million $4 billion

• How much was stolen and damaged in all residential and commercial burglaries in England Wales in 2000? • • £ 230, 000 £ 2. 3 million £ 2. 3 billion £ 2. 3 trillion

• How much was stolen and damaged in all residential and commercial burglaries in England Wales in 2000? • • £ 230, 000 £ 2. 3 million £ 2. 3 billion £ 2. 3 trillion

Defining State Crime 1. Narrow legalism – acts defined by law as criminal, committed by state officials in their capacity as representatives of the state. But: • State crime is not clearly defined in either domestic or international law • Domestic legal framework allows us to charge individuals but not so the collective. • International Law Commission couldn’t reach agreement on what to define as state crime. • US, China, Israel and India refused to sign up to the International Criminal Court in 2002 (due to tensions between geopolitical interests and protecting human rights).

Defining State Crime 1. Narrow legalism – acts defined by law as criminal, committed by state officials in their capacity as representatives of the state. But: • State crime is not clearly defined in either domestic or international law • Domestic legal framework allows us to charge individuals but not so the collective. • International Law Commission couldn’t reach agreement on what to define as state crime. • US, China, Israel and India refused to sign up to the International Criminal Court in 2002 (due to tensions between geopolitical interests and protecting human rights).

Defining State Crime 2. Moral Crusade – includes a broad spectrum of ‘rights’ e. g. food, shelter, clothing, medical supplies – things that can cause ‘social harm’ as opposed to things that regarded as the more serious human rights abuses, e. g. genocide, mass political killings, state terrorism etc. • It is argued that equating economic exploitation with genocide does not help in the criminological study of state crimes either. • A further problem is that rights are contested and contradictory

Defining State Crime 2. Moral Crusade – includes a broad spectrum of ‘rights’ e. g. food, shelter, clothing, medical supplies – things that can cause ‘social harm’ as opposed to things that regarded as the more serious human rights abuses, e. g. genocide, mass political killings, state terrorism etc. • It is argued that equating economic exploitation with genocide does not help in the criminological study of state crimes either. • A further problem is that rights are contested and contradictory

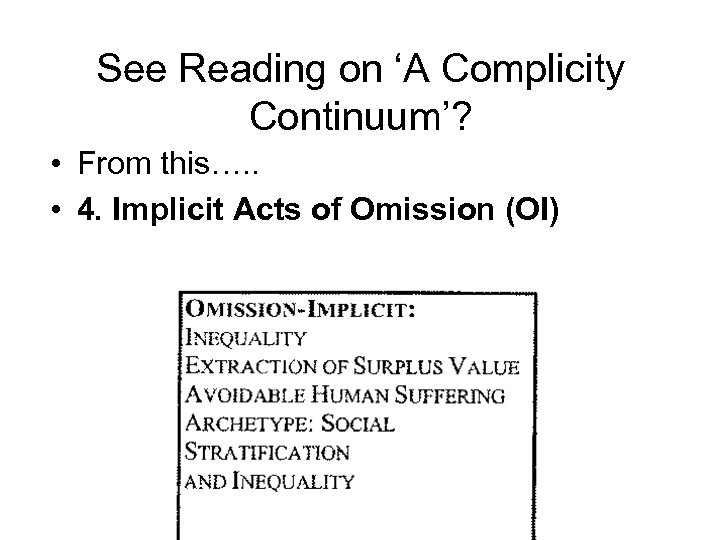

See Reading on ‘A Complicity Continuum’? • From this…. . • 4. Implicit Acts of Omission (OI)

See Reading on ‘A Complicity Continuum’? • From this…. . • 4. Implicit Acts of Omission (OI)

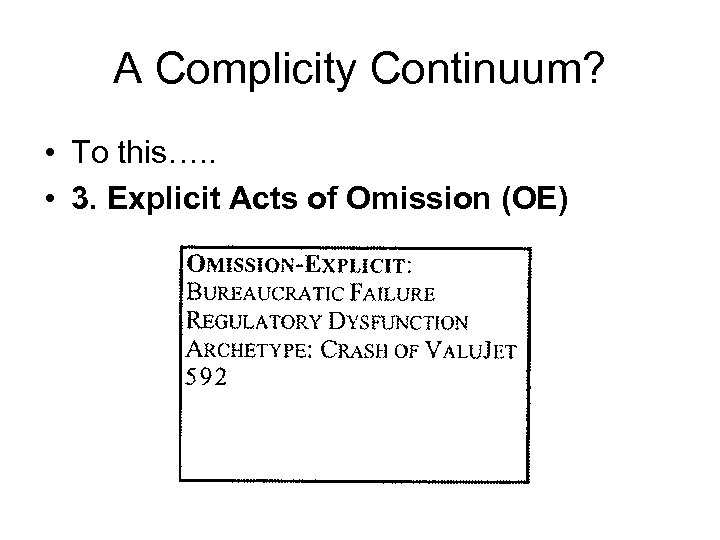

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 3. Explicit Acts of Omission (OE)

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 3. Explicit Acts of Omission (OE)

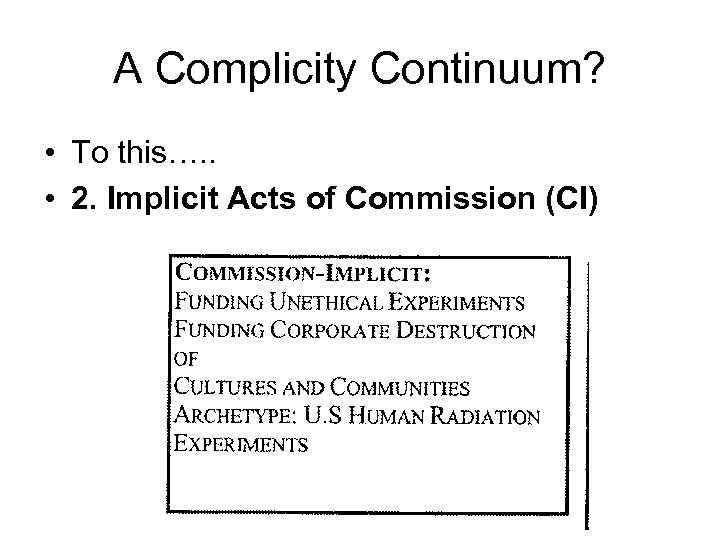

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 2. Implicit Acts of Commission (CI)

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 2. Implicit Acts of Commission (CI)

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 1. Explicit Acts of Commission (CE)

A Complicity Continuum? • To this…. . • 1. Explicit Acts of Commission (CE)

What is state crime in this module? • Green and Ward define it as ‘state organisational deviance involving the violation of human rights’ (2004: 2) • You need to understand 3 key concepts to understand this – the state, organisational deviance, human rights.

What is state crime in this module? • Green and Ward define it as ‘state organisational deviance involving the violation of human rights’ (2004: 2) • You need to understand 3 key concepts to understand this – the state, organisational deviance, human rights.

The State • Liberal states and autocratic states, while different in many respects are similar in one- -they claim an entitlement to do things which would be considered as violent or extortionate if it were not the state that was doing it. • Max Weber’s ‘monopoly of the legitimate use of force’.

The State • Liberal states and autocratic states, while different in many respects are similar in one- -they claim an entitlement to do things which would be considered as violent or extortionate if it were not the state that was doing it. • Max Weber’s ‘monopoly of the legitimate use of force’.

Where does the state get it’s legitimacy from? • When it behaves according to the rules that it has set down for itself and its citizens. • When its rules are justified by shared beliefs, the creation of a consensus and a ‘common sense’ approach and the creation of a hegemony. • Known as ‘willing compliance’, ‘passive acquiescence’, ‘ingrained dependence’.

Where does the state get it’s legitimacy from? • When it behaves according to the rules that it has set down for itself and its citizens. • When its rules are justified by shared beliefs, the creation of a consensus and a ‘common sense’ approach and the creation of a hegemony. • Known as ‘willing compliance’, ‘passive acquiescence’, ‘ingrained dependence’.

How does the state get this ‘willing compliance’? • Denial of injury (didn’t really hurt anybody), denial of the victim (t’was their own fault), denial of responsibility (didn’t mean it), condemnation of the condemner (it’s only because you don’t like me/picking on me), appeals to higher loyalty (I did it for you/for God) – see reading list. • Also, by defining political aims, defining political in- and out-groups, disseminating propaganda and justifications for violence against the out-group, and signalling that it expects these aims, rules, views, and orders to be followed. • Stanley Milgrim Experiments and Obedience.

How does the state get this ‘willing compliance’? • Denial of injury (didn’t really hurt anybody), denial of the victim (t’was their own fault), denial of responsibility (didn’t mean it), condemnation of the condemner (it’s only because you don’t like me/picking on me), appeals to higher loyalty (I did it for you/for God) – see reading list. • Also, by defining political aims, defining political in- and out-groups, disseminating propaganda and justifications for violence against the out-group, and signalling that it expects these aims, rules, views, and orders to be followed. • Stanley Milgrim Experiments and Obedience.

Organisational Deviance • Deviance – behaviour which infringes a social rule. • Green and Ward define it as: ‘an act is deviant where there is a social audience that (1) accepts a certain rule as standard behaviour, (2) interprets the act (or similar acts of which it is aware) as violating the rule and (3) is disposed to apply significant sanctions – that is significant from the point of view of the actor – to such violations’. (2004: 4) • State crime is ONE category of organisational deviance

Organisational Deviance • Deviance – behaviour which infringes a social rule. • Green and Ward define it as: ‘an act is deviant where there is a social audience that (1) accepts a certain rule as standard behaviour, (2) interprets the act (or similar acts of which it is aware) as violating the rule and (3) is disposed to apply significant sanctions – that is significant from the point of view of the actor – to such violations’. (2004: 4) • State crime is ONE category of organisational deviance

Human Rights • The normative ideals of human rights – such as in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Human Rights • The normative ideals of human rights – such as in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

An alternative definition: It’s not crime – it’s HARM • Looking at State Crime as State Harm instead: • Problem with existing definitions of state crime (in the legal sense) include the problematic way in which crime is defined, the highly political nature of defining harms as crimes (while ignoring equally harmful behaviors), the problematic way in which the state creates harm by controlling crime, and the overall ineffectiveness – and potential harmfulness – of mechanisms of social control. • Expanded to the concept of state crime, then, some advocates of the social harms perspective would encourage criminologists to focus their efforts not on defining the actions of the state as criminal, but rather cataloging the wide range of state behaviors that are harmful.

An alternative definition: It’s not crime – it’s HARM • Looking at State Crime as State Harm instead: • Problem with existing definitions of state crime (in the legal sense) include the problematic way in which crime is defined, the highly political nature of defining harms as crimes (while ignoring equally harmful behaviors), the problematic way in which the state creates harm by controlling crime, and the overall ineffectiveness – and potential harmfulness – of mechanisms of social control. • Expanded to the concept of state crime, then, some advocates of the social harms perspective would encourage criminologists to focus their efforts not on defining the actions of the state as criminal, but rather cataloging the wide range of state behaviors that are harmful.

Case Study: International Criminal Court • Established in 1998 by International Treaty in Rome • Created to provide justice for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes when national systems fail. • One hundred and eight states have ratified the Rome statute, but there are notable absentees - the US, Israel, China and India. Britain opposed the ICC until Tony Blair replaced John Major as prime minister in 1997. • Questions over the court's legitimacy have inevitably arisen because it has not been ratified by key parties.

Case Study: International Criminal Court • Established in 1998 by International Treaty in Rome • Created to provide justice for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes when national systems fail. • One hundred and eight states have ratified the Rome statute, but there are notable absentees - the US, Israel, China and India. Britain opposed the ICC until Tony Blair replaced John Major as prime minister in 1997. • Questions over the court's legitimacy have inevitably arisen because it has not been ratified by key parties.

• Currently hearing evidence against a A Congolese militia leader, Thomas Lubanga, the former head of the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC). • The ICC's first case is being seen as a significant test of its credibility, and has already attracted controversy. • Human rights groups have criticised the prosecutors for limiting charges against Lubanga to the recruitment of child soldiers when the UPC was responsible for a host of other crimes.

• Currently hearing evidence against a A Congolese militia leader, Thomas Lubanga, the former head of the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC). • The ICC's first case is being seen as a significant test of its credibility, and has already attracted controversy. • Human rights groups have criticised the prosecutors for limiting charges against Lubanga to the recruitment of child soldiers when the UPC was responsible for a host of other crimes.

Thomas Lubanga – charged with recruiting child soldiers under the age of 15.

Thomas Lubanga – charged with recruiting child soldiers under the age of 15.

• In 2002 and 2003, Lubanga was the head of an armed opposition group known as the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) in the Ituri region of eastern Congo. He claimed to have 15, 000 troops under his command; local observers believed that at least 40% were children. Lubanga's soldiers routinely recruited children by force, including boys and girls as young as seven. In one incident in 2002, UPC soldiers entered a school and forcibly rounded up the entire fifth grade for military service. Children were so prevalent in the UPC that the force was known as "an army of children".

• In 2002 and 2003, Lubanga was the head of an armed opposition group known as the Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) in the Ituri region of eastern Congo. He claimed to have 15, 000 troops under his command; local observers believed that at least 40% were children. Lubanga's soldiers routinely recruited children by force, including boys and girls as young as seven. In one incident in 2002, UPC soldiers entered a school and forcibly rounded up the entire fifth grade for military service. Children were so prevalent in the UPC that the force was known as "an army of children".

The first witness…. • The first witness at the war crimes trial of DR Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga has retracted his testimony at the International Criminal Court (just last week). • A delay of the trial has been agreed to investigate "concerns the witness has about protective measures. . . what happens after he gives his testimony and returns home".

The first witness…. • The first witness at the war crimes trial of DR Congolese warlord Thomas Lubanga has retracted his testimony at the International Criminal Court (just last week). • A delay of the trial has been agreed to investigate "concerns the witness has about protective measures. . . what happens after he gives his testimony and returns home".

But consider this…. . • In the UK, in 2001, there were 6000 soldiers under the age of eighteen serving in the armed forces. • In March 2002, under pressure from the European Union, the government stated that these soldiers would no longer be sent into combat positions. • However, Article 38 of the UNCRC states that fifteen is the minimum age for recruitment and there is no law which forbids children under eighteen to fight.

But consider this…. . • In the UK, in 2001, there were 6000 soldiers under the age of eighteen serving in the armed forces. • In March 2002, under pressure from the European Union, the government stated that these soldiers would no longer be sent into combat positions. • However, Article 38 of the UNCRC states that fifteen is the minimum age for recruitment and there is no law which forbids children under eighteen to fight.

Conclusions • Criminologists should not be in the business of allowing the state to define the scope of their inquiry. • Therefore, it is important not to consider ‘state crime’ in the narrow legalistic framework but rather in a wider framework. • That said, the problems of definitions of what should/could be included in the definition of a ‘state crime’ remains.

Conclusions • Criminologists should not be in the business of allowing the state to define the scope of their inquiry. • Therefore, it is important not to consider ‘state crime’ in the narrow legalistic framework but rather in a wider framework. • That said, the problems of definitions of what should/could be included in the definition of a ‘state crime’ remains.

Things to Do/Consider • Look at the International Law Commission, particularly its Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. • Look into the International Criminal Court. How many cases are they progressing with at the minute? What are they in relation to? • Look at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Consider whether violations of some of the ‘rights’ by the state would constitute a ‘state crime’ in your mind. If so, why? If not, why not? • Why is the study of children in the context of conflicts and state crimes considered to be so difficult?

Things to Do/Consider • Look at the International Law Commission, particularly its Draft Articles on the Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts. • Look into the International Criminal Court. How many cases are they progressing with at the minute? What are they in relation to? • Look at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Consider whether violations of some of the ‘rights’ by the state would constitute a ‘state crime’ in your mind. If so, why? If not, why not? • Why is the study of children in the context of conflicts and state crimes considered to be so difficult?