61d1408c6dcae42a061f6c41ae47351a.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 176

Web Services Chapter 28

Web Basics

Internet • Collection of physically interconnected computers. • Messages decomposed into packets. • Packets transmitted from source to destination using a store-and-forward technique. • Routing algorithm directs packets to destination 3

Connection-Oriented Protocol • Prior to transmission: connection is established between source and destination. Each maintains state information: – Sequence numbers, acknowledgements provide reliability • guarantee that packet loss or duplication will be detected • packets arrive in the order they were sent – Buffers, flow control algorithm guarantee transmission rate appropriate to both sender and receiver – Destination address – Characteristics of connection (e. g. , out-of-band messages) • Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is connection-oriented. • Problem: Overhead of setting up & taking down connection. 4

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) • A high level protocol built on top of a TCP connection for exchanging messages (with arbitrary content) – Each (request) message from client to server is followed by a (response) message from server to client. – Facilitates remote invocation of methods on the server. • Web: A set of client and server processes on the Internet that communicate via HTTP. 5

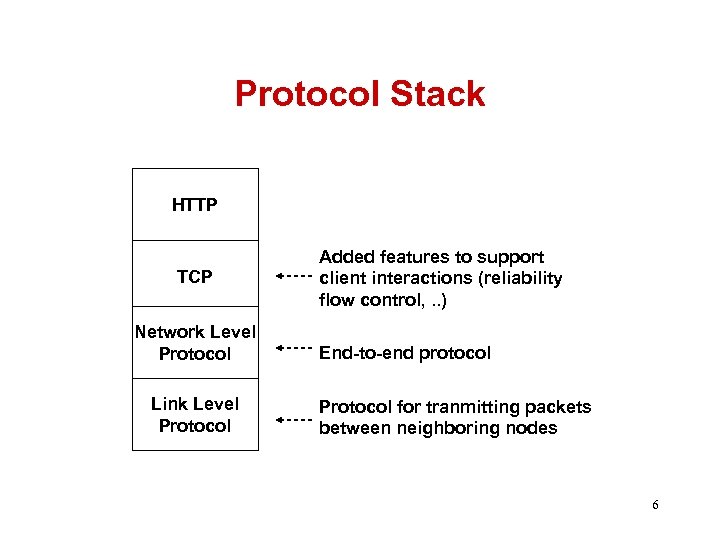

Protocol Stack HTTP TCP Network Level Protocol Link Level Protocol Added features to support client interactions (reliability flow control, . . ) End-to-end protocol Protocol for tranmitting packets between neighboring nodes 6

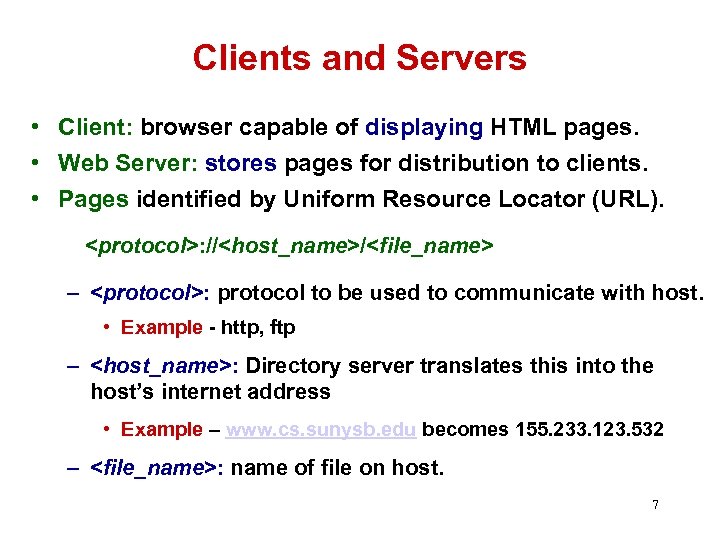

Clients and Servers • Client: browser capable of displaying HTML pages. • Web Server: stores pages for distribution to clients. • Pages identified by Uniform Resource Locator (URL). <protocol>: //<host_name>/<file_name> – <protocol>: protocol to be used to communicate with host. • Example - http, ftp – <host_name>: Directory server translates this into the host’s internet address • Example – www. cs. sunysb. edu becomes 155. 233. 123. 532 – <file_name>: name of file on host. 7

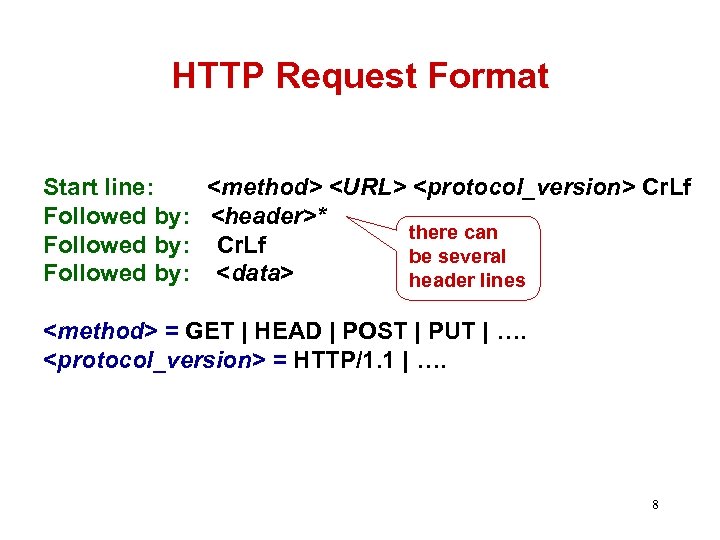

HTTP Request Format Start line: <method> <URL> <protocol_version> Cr. Lf Followed by: <header>* there can Followed by: Cr. Lf be several Followed by: <data> header lines <method> = GET | HEAD | POST | PUT | …. <protocol_version> = HTTP/1. 1 | …. 8

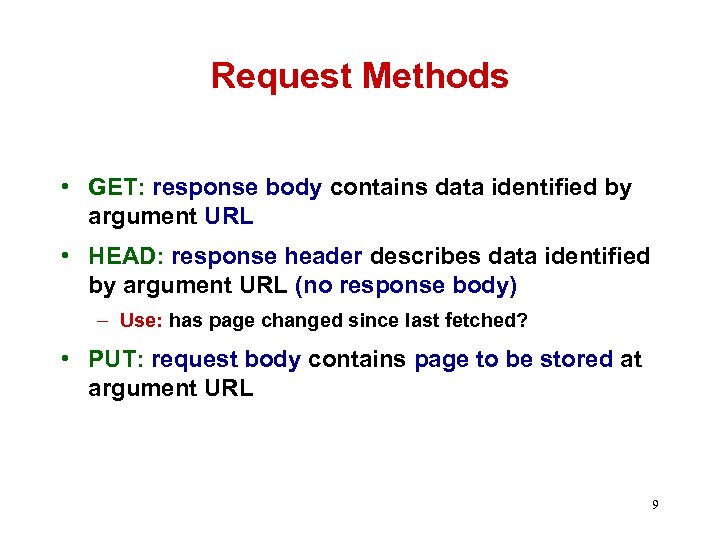

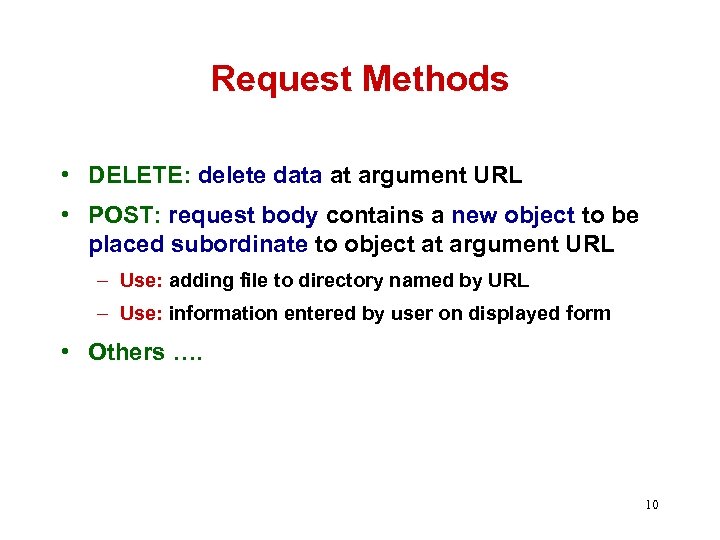

Request Methods • GET: response body contains data identified by argument URL • HEAD: response header describes data identified by argument URL (no response body) – Use: has page changed since last fetched? • PUT: request body contains page to be stored at argument URL 9

Request Methods • DELETE: delete data at argument URL • POST: request body contains a new object to be placed subordinate to object at argument URL – Use: adding file to directory named by URL – Use: information entered by user on displayed form • Others …. 10

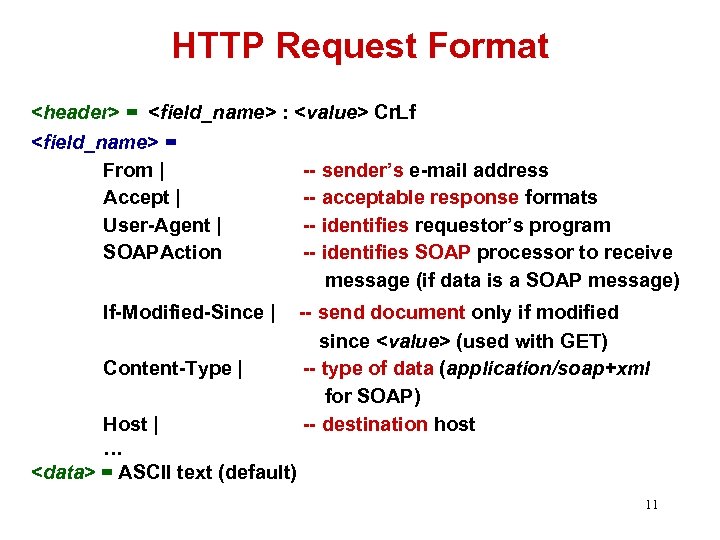

HTTP Request Format <header> = <field_name> : <value> Cr. Lf <field_name> = From | -- sender’s e-mail address Accept | -- acceptable response formats User-Agent | -- identifies requestor’s program SOAPAction -- identifies SOAP processor to receive message (if data is a SOAP message) If-Modified-Since | Content-Type | Host | … <data> = ASCII text (default) -- send document only if modified since <value> (used with GET) -- type of data (application/soap+xml for SOAP) -- destination host 11

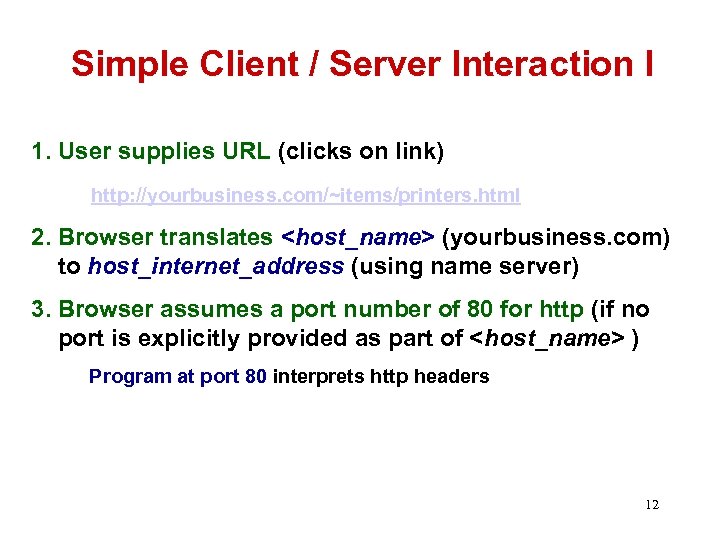

Simple Client / Server Interaction I 1. User supplies URL (clicks on link) http: //yourbusiness. com/~items/printers. html 2. Browser translates <host_name> (yourbusiness. com) to host_internet_address (using name server) 3. Browser assumes a port number of 80 for http (if no port is explicitly provided as part of <host_name> ) Program at port 80 interprets http headers 12

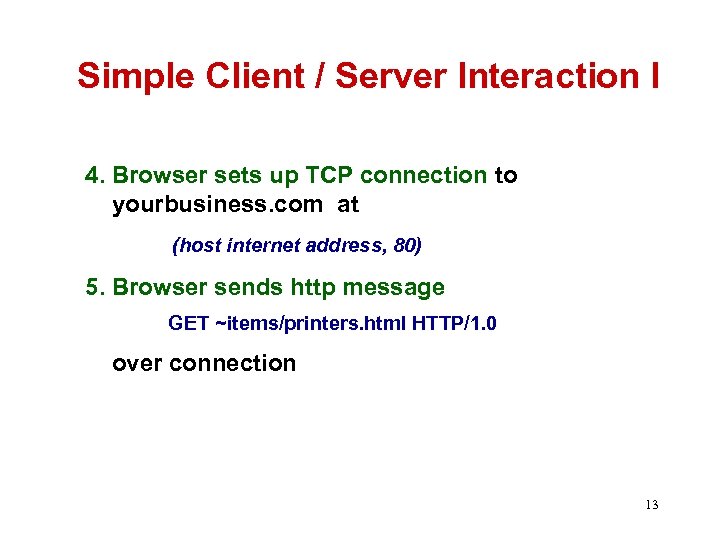

Simple Client / Server Interaction I 4. Browser sets up TCP connection to yourbusiness. com at (host internet address, 80) 5. Browser sends http message GET ~items/printers. html HTTP/1. 0 over connection 13

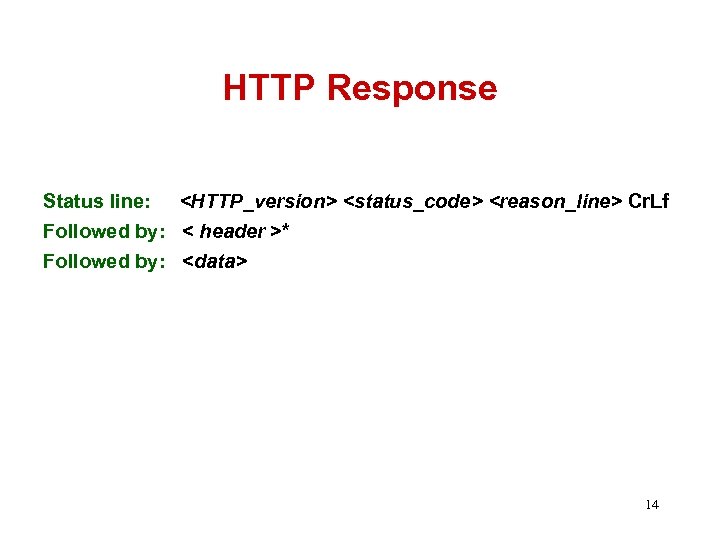

HTTP Response Status line: <HTTP_version> <status_code> <reason_line> Cr. Lf Followed by: < header >* Followed by: <data> 14

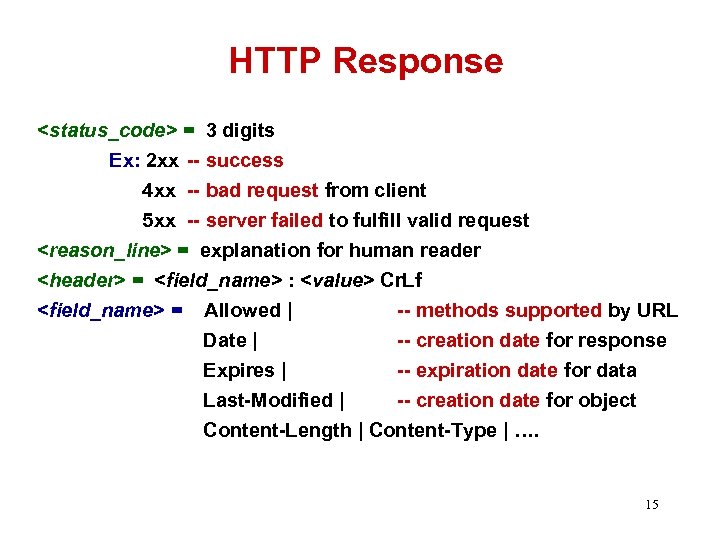

HTTP Response <status_code> = 3 digits Ex: 2 xx -- success 4 xx -- bad request from client 5 xx -- server failed to fulfill valid request <reason_line> = explanation for human reader <header> = <field_name> : <value> Cr. Lf <field_name> = Allowed | -- methods supported by URL Date | -- creation date for response Expires | -- expiration date for data Last-Modified | -- creation date for object Content-Length | Content-Type | …. 15

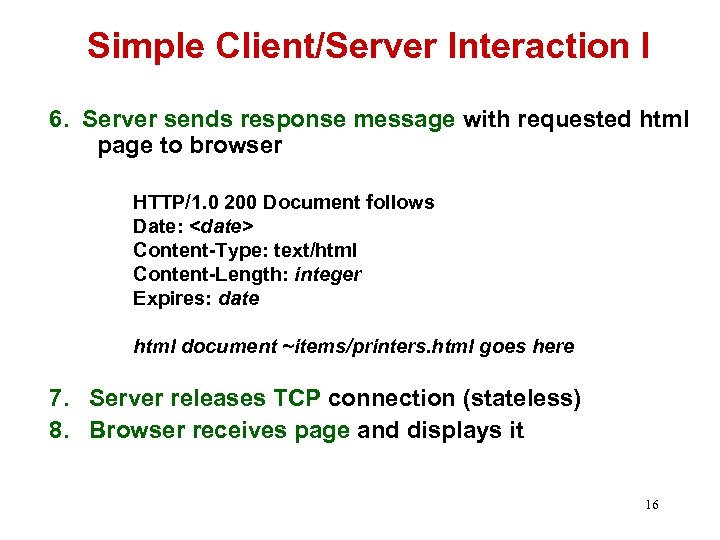

Simple Client/Server Interaction I 6. Server sends response message with requested html page to browser HTTP/1. 0 200 Document follows Date: <date> Content-Type: text/html Content-Length: integer Expires: date html document ~items/printers. html goes here 7. Server releases TCP connection (stateless) 8. Browser receives page and displays it 16

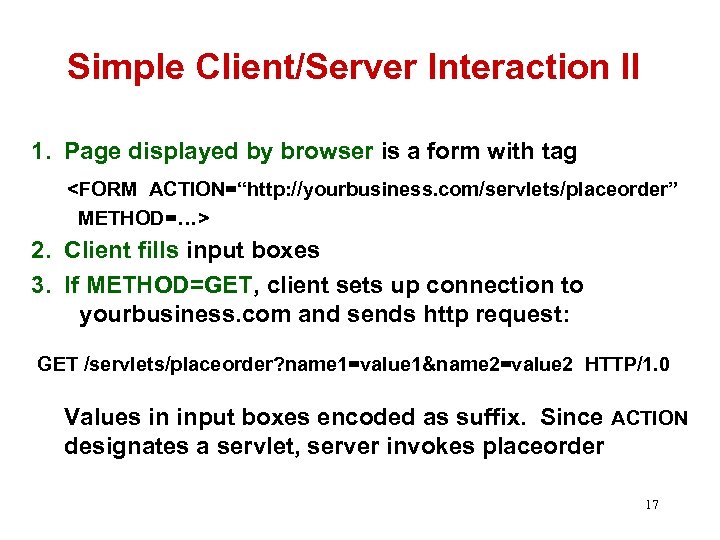

Simple Client/Server Interaction II 1. Page displayed by browser is a form with tag <FORM ACTION=“http: //yourbusiness. com/servlets/placeorder” METHOD=…> 2. Client fills input boxes 3. If METHOD=GET, client sets up connection to yourbusiness. com and sends http request: GET /servlets/placeorder? name 1=value 1&name 2=value 2 HTTP/1. 0 Values in input boxes encoded as suffix. Since ACTION designates a servlet, server invokes placeorder 17

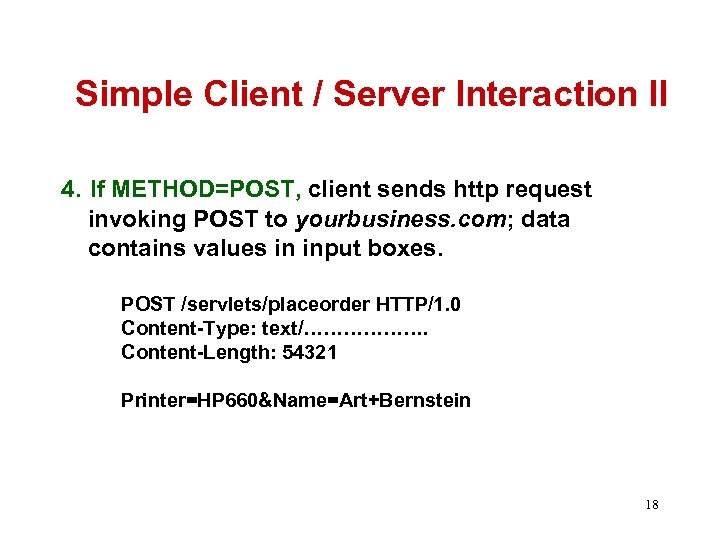

Simple Client / Server Interaction II 4. If METHOD=POST, client sends http request invoking POST to yourbusiness. com; data contains values in input boxes. POST /servlets/placeorder HTTP/1. 0 Content-Type: text/………………. Content-Length: 54321 Printer=HP 660&Name=Art+Bernstein 18

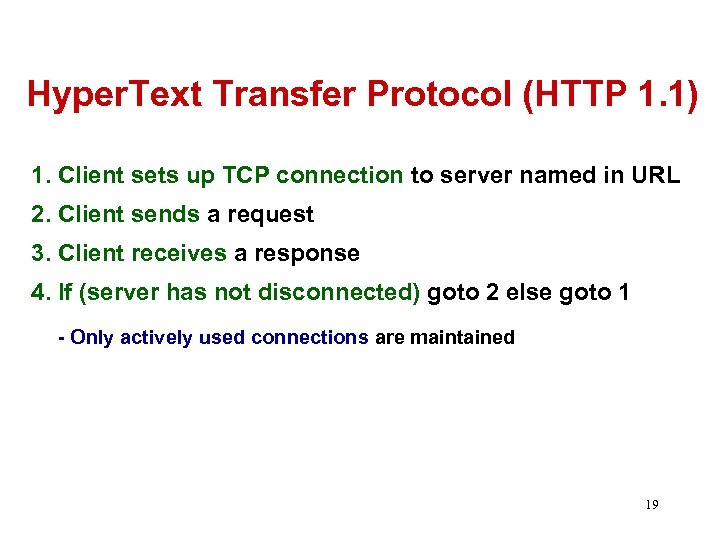

Hyper. Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP 1. 1) 1. Client sets up TCP connection to server named in URL 2. Client sends a request 3. Client receives a response 4. If (server has not disconnected) goto 2 else goto 1 - Only actively used connections are maintained 19

SOAP Version 1. 2

What is SOAP? • The de facto standard for Web Service communication that provides support for: – Remote procedure call (RPC) to invoke methods on servers – Messaging to exchange documents – Extensibility – Error handling – Flexible data encoding – Binding to a variety of transports (e. g. , SOAP, SMTP) • We will discuss Version 1. 2 21

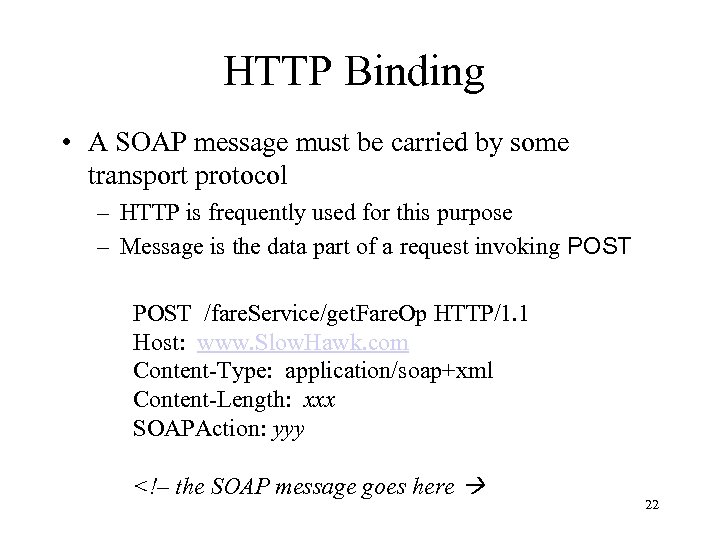

HTTP Binding • A SOAP message must be carried by some transport protocol – HTTP is frequently used for this purpose – Message is the data part of a request invoking POST /fare. Service/get. Fare. Op HTTP/1. 1 Host: www. Slow. Hawk. com Content-Type: application/soap+xml Content-Length: xxx SOAPAction: yyy <!– the SOAP message goes here 22

SOAP and XML • Since XML is language and platform independent, it is the lingua franca for the exchange of information in a heterogeneous distributed system. • SOAP supports the transmission of arbitrary XML documents • For RPC, SOAP provides a message format for invoking a procedure and returning results in XML 23

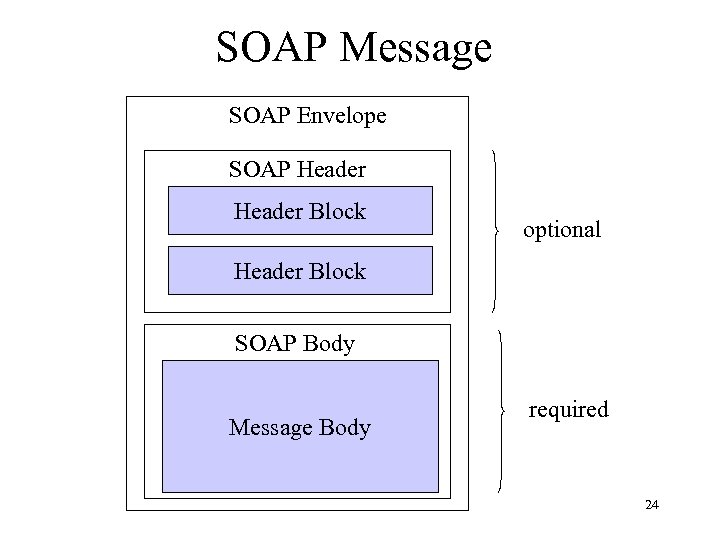

SOAP Message SOAP Envelope SOAP Header Block optional Header Block SOAP Body Message Body required 24

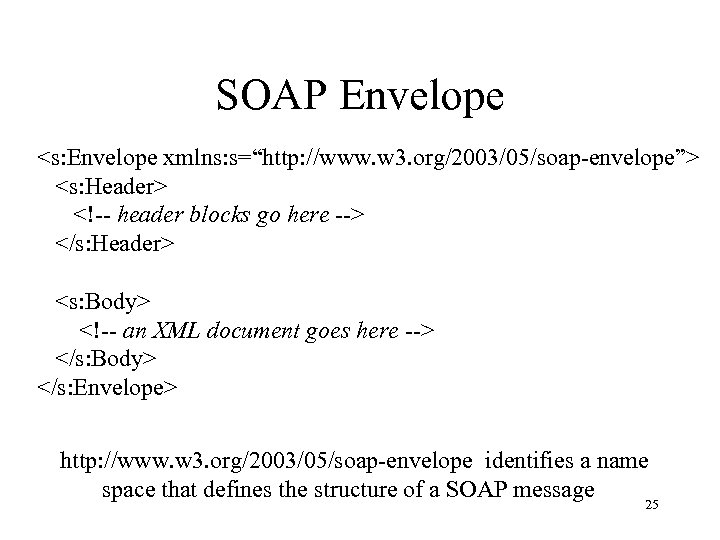

SOAP Envelope <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope”> <s: Header> <!-- header blocks go here --> </s: Header> <s: Body> <!-- an XML document goes here --> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope identifies a name space that defines the structure of a SOAP message 25

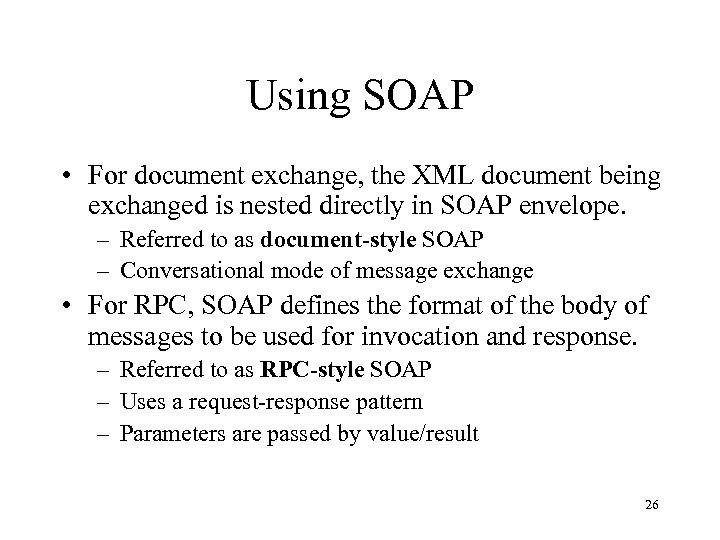

Using SOAP • For document exchange, the XML document being exchanged is nested directly in SOAP envelope. – Referred to as document-style SOAP – Conversational mode of message exchange • For RPC, SOAP defines the format of the body of messages to be used for invocation and response. – Referred to as RPC-style SOAP – Uses a request-response pattern – Parameters are passed by value/result 26

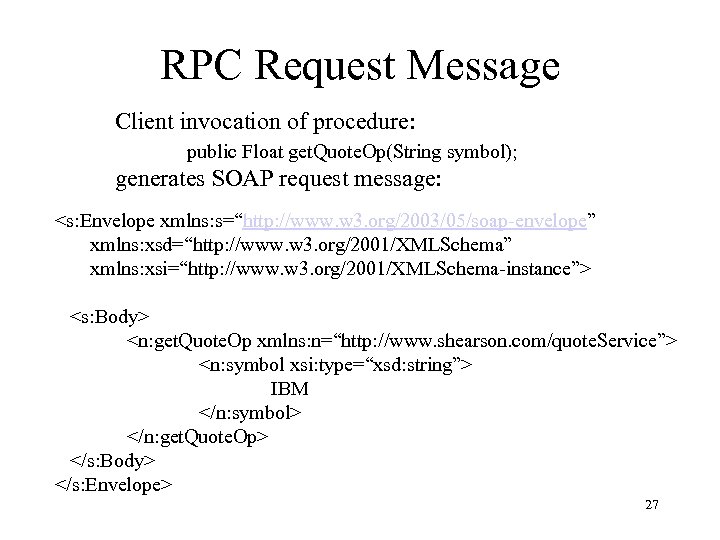

RPC Request Message Client invocation of procedure: public Float get. Quote. Op(String symbol); generates SOAP request message: <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: xsi=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema-instance”> <s: Body> <n: get. Quote. Op xmlns: n=“http: //www. shearson. com/quote. Service”> <n: symbol xsi: type=“xsd: string”> IBM </n: symbol> </n: get. Quote. Op> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 27

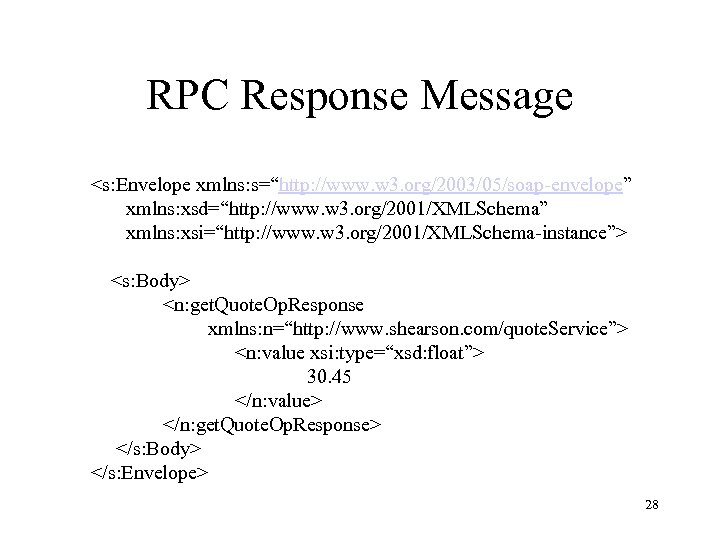

RPC Response Message <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: xsi=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema-instance”> <s: Body> <n: get. Quote. Op. Response xmlns: n=“http: //www. shearson. com/quote. Service”> <n: value xsi: type=“xsd: float”> 30. 45 </n: value> </n: get. Quote. Op. Response> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 28

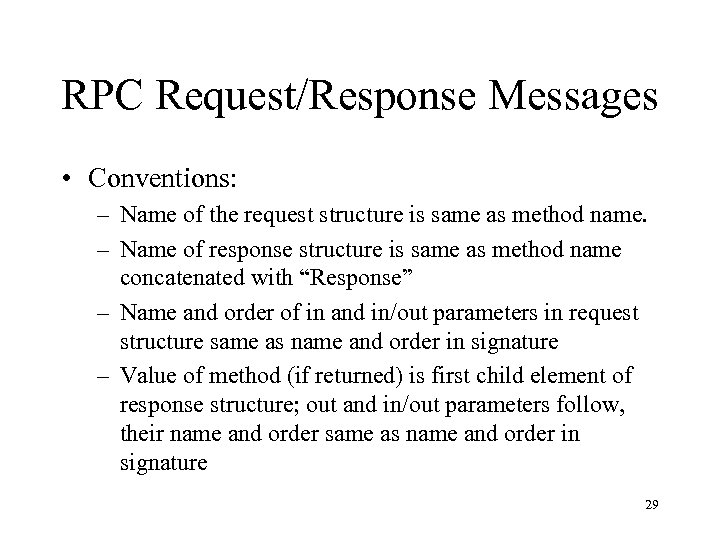

RPC Request/Response Messages • Conventions: – Name of the request structure is same as method name. – Name of response structure is same as method name concatenated with “Response” – Name and order of in and in/out parameters in request structure same as name and order in signature – Value of method (if returned) is first child element of response structure; out and in/out parameters follow, their name and order same as name and order in signature 29

Data Encoding • Problem: SOAP provides a language/platform independent mechanism for invoking remote procedures – Argument values are carried in an XML document – Caller and callee may use different representations of the same types (e. g. , Java, C) – A mechanism is needed for mapping from caller’s format to XML syntax and from XML syntax to callee’s format (referred to as serialization/deserialization) • Example: mapping a Java array to XML syntax 30

Serialization • Serialization is simple for simple types (integer, string, float, …) since they correspond to XML Schema types. – Translate from binary to ASCII using XML schema specified format • Serialization not so simple for complex types – Ex: What tags will be used for an array? Will it be stored by rows or by columns? How will a sparse array be sent? 31

Encoding Style • encoding. Style attribute used to identify the serialization rules to encode the data contents of an element – An arbitrary set of rules can be used – SOAP defines its own set of rules – Message is referred to as RPC/encoded • RPC refers to the format of the message as a whole • Encoded refers to the fact that argument values have been represented using the rule set specified in the encoding style attribute 32

SOAP Encoding Style • SOAP defines its own graphical data model for describing complex types and rules for transforming instances of the model into serialized ASCII strings – Vendors provide serializers (and deserializers) which maps each local type to an instance of the model and then transforms the local representation to the encoded data using the SOAP rules 33

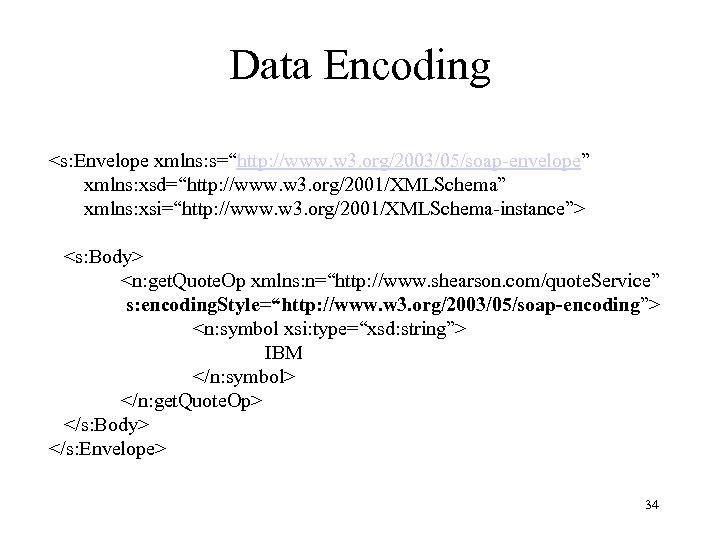

Data Encoding <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: xsi=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema-instance”> <s: Body> <n: get. Quote. Op xmlns: n=“http: //www. shearson. com/quote. Service” s: encoding. Style=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-encoding”> <n: symbol xsi: type=“xsd: string”> IBM </n: symbol> </n: get. Quote. Op> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 34

SOAP Extensibility • A SOAP message goes from client to server to advance some application related cause. • It is often the case that some orthogonal issues related to the message must be handled: – Security: encryption, authentication, authorization – Transaction management – Tracing – Logging 35

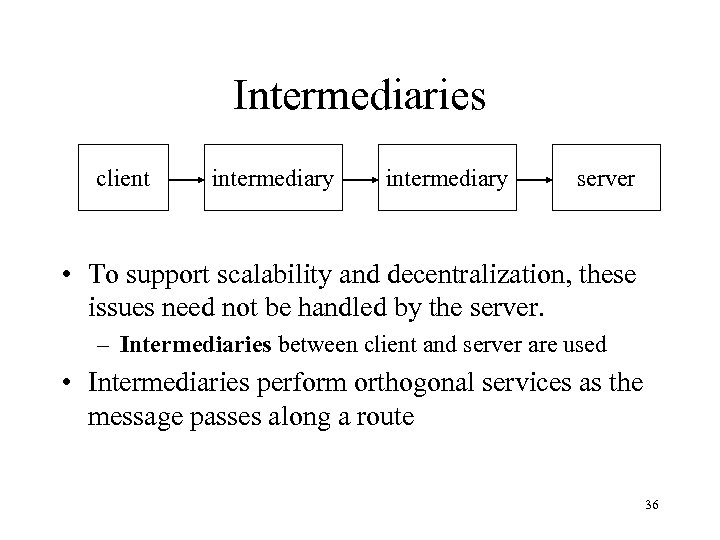

Intermediaries client intermediary server • To support scalability and decentralization, these issues need not be handled by the server. – Intermediaries between client and server are used • Intermediaries perform orthogonal services as the message passes along a route 36

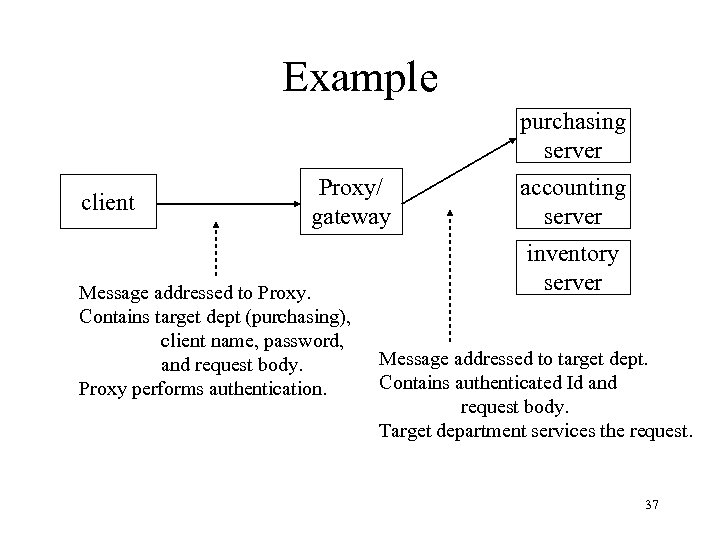

Example purchasing server client Proxy/ gateway Message addressed to Proxy. Contains target dept (purchasing), client name, password, and request body. Proxy performs authentication. accounting server inventory server Message addressed to target dept. Contains authenticated Id and request body. Target department services the request. 37

Requirements • Information directed to each intermediary and to final destination kept separate – Intermediaries can be easily added/deleted, route changed • SOAP does not specify how routing is to be done – It is up to each node along the chain to know where to send the message next • Information carried in the message may direct routing 38

Header • SOAP envelope defines an optional header containing an arbitrary number of header blocks. Each block: – Has an optional role and should be processed by an intermediary that can perform that role – Can have its own namespace declaration • Eliminates the possibility of interference between groups that independently design headers. 39

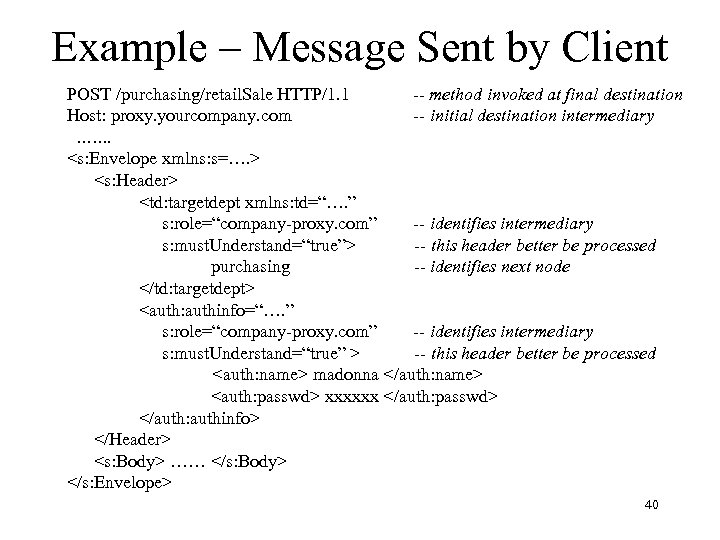

Example – Message Sent by Client POST /purchasing/retail. Sale HTTP/1. 1 -- method invoked at final destination Host: proxy. yourcompany. com -- initial destination intermediary ……. <s: Envelope xmlns: s=…. > <s: Header> <td: targetdept xmlns: td=“…. ” s: role=“company-proxy. com” -- identifies intermediary s: must. Understand=“true”> -- this header better be processed purchasing -- identifies next node </td: targetdept> <auth: authinfo=“…. ” s: role=“company-proxy. com” -- identifies intermediary s: must. Understand=“true” > -- this header better be processed <auth: name> madonna </auth: name> <auth: passwd> xxxxxx </auth: passwd> </auth: authinfo> </Header> <s: Body> …… </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 40

Processing Model • An intermediary has an assigned set of roles • On receiving a message, it identifies the blocks whose role attribute matches an element of its set (or has value next) – A block without a role attribute is targeted for final destination • The intermediary – – can modify/delete its block can insert new blocks should retarget the message to the next destination can do anything (frowned upon) 41

Must Understand • An intermediary can choose to ignore a block directed to it • If must. Understand attribute has value “true” intermediary must process the block or else abort the message and return a fault message 42

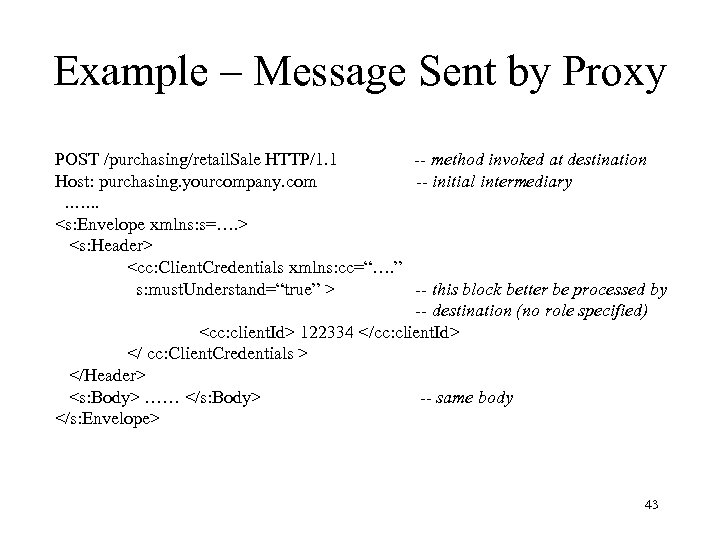

Example – Message Sent by Proxy POST /purchasing/retail. Sale HTTP/1. 1 -- method invoked at destination Host: purchasing. yourcompany. com -- initial intermediary ……. <s: Envelope xmlns: s=…. > <s: Header> <cc: Client. Credentials xmlns: cc=“…. ” s: must. Understand=“true” > -- this block better be processed by -- destination (no role specified) <cc: client. Id> 122334 </cc: client. Id> </ cc: Client. Credentials > </Header> <s: Body> …… </s: Body> -- same body </s: Envelope> 43

Example – Message Sent by Proxy • Proxy has deleted the two headers – Verified that user is valid using <name> and <passwd> and determined Id – Retargeted message to final destination using <targetdept> • Proxy has inserted a new header containing Id – Final destination uses Id to determine authorization 44

WS-Addressing • Problem: As described up to this point destination address (including target SOAP processor) is not included in SOAP message – This information is contained in transport header (e. g. , SOAPAction header in HTTP) – Information has to be supplied separately to the transport and the mechanism for doing this is different for different transports • SOAP is not transport-neutral 45

WS-Addressing • Solution: Include the information in SOAP header blocks. • WS-Addressing is defined for this purpose: – <wsa: To> - destination URL – <wsa: Action> - message intent (analogous to SOAPAction) – <wsa: Message. ID> - unique Id – <wsa: Reply. To> - address for reply – <wsa: Relates. To> - Id of another message – …. 46

WS-Addressing • The type Endpoint. Reference. Type is defined to carry references to endpoints (e. g. , value of Reply. To) – Contains destination address as well as additional information that might be needed to send a message to that address: • Identity of WSDL elements describing destination (port type, service, . . ) • Policy information (e. g. , should message be encrypted) 47

SOAP Faults • SOAP provides a message format for communicating information about errors containing the following information: – Fault category identifies error (not meant for human consumption) – • • Version. Mismatch Must. Understand – related to headers Sender – problem with message content Receiver – error had nothing to do with the message – human readable explanation – node at which error occurred (related to intermediaries) – application specific information about Client error 48

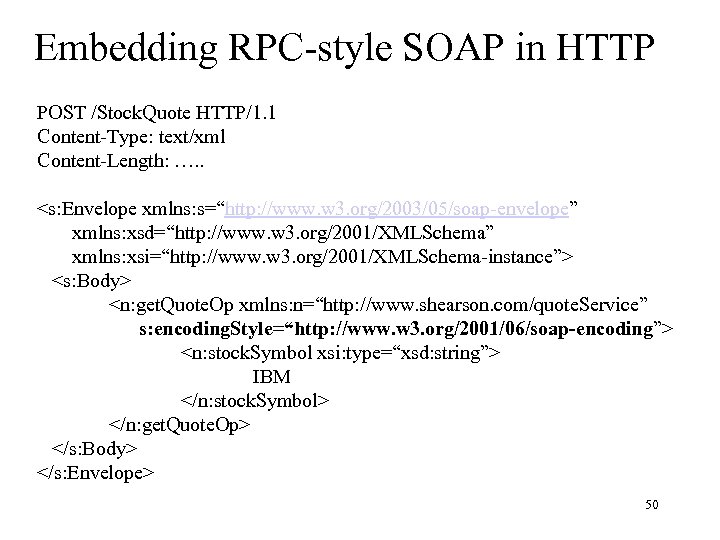

Embedding SOAP in HTTP: POST • For document-style SOAP, the envelope is the body of an HTTP POST. – The HTTP response message simply acknowledges receipt of HTTP request messsage • For RPC-style SOAP, the envelope containing the SOAP request is the body of an HTTP POST; the envelope containing the SOAP response (or fault) is the body of the corresponding HTTP response. 49

Embedding RPC-style SOAP in HTTP POST /Stock. Quote HTTP/1. 1 Content-Type: text/xml Content-Length: …. . <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: xsi=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema-instance”> <s: Body> <n: get. Quote. Op xmlns: n=“http: //www. shearson. com/quote. Service” s: encoding. Style=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/06/soap-encoding”> <n: stock. Symbol xsi: type=“xsd: string”> IBM </n: stock. Symbol> </n: get. Quote. Op> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 50

Embedding Soap in HTTP: GET • In some situations the client simply wants to retrieve an XML document – An HTTP GET request message is sent with no data (no SOAP content) – Document (actually a SOAP envelope) is returned as the data in the HTTP response 51

Web Services Description Language (WSDL) Version 1. 1

Goals of WSDL • Describes the formats and protocols of a Web Service in a standard way – The operations the service supports – The message(s) needed to invoke the operations – The binding of the messages to a communication protocol – The address to which messages should be sent 53

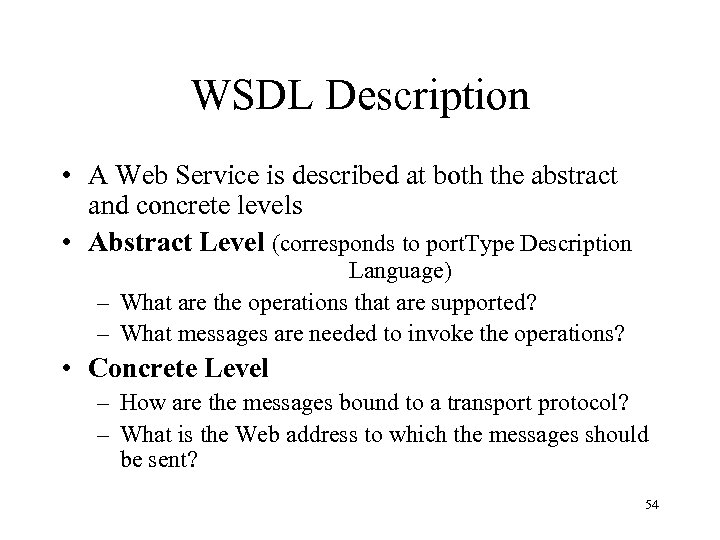

WSDL Description • A Web Service is described at both the abstract and concrete levels • Abstract Level (corresponds to port. Type Description Language) – What are the operations that are supported? – What messages are needed to invoke the operations? • Concrete Level – How are the messages bound to a transport protocol? – What is the Web address to which the messages should be sent? 54

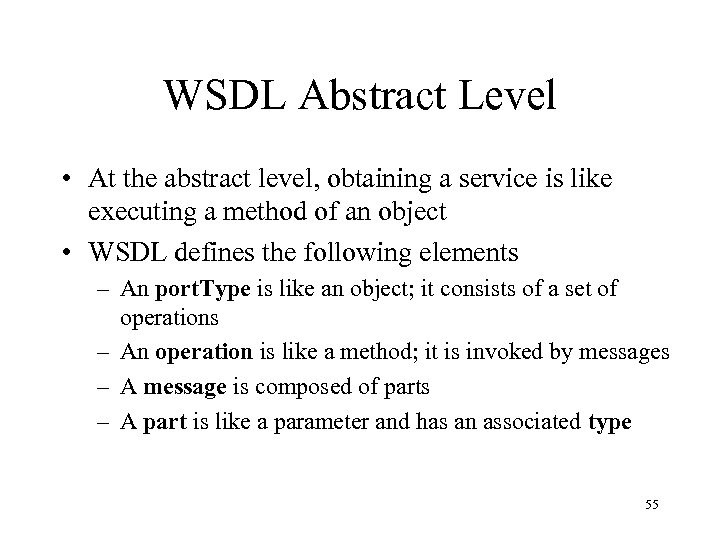

WSDL Abstract Level • At the abstract level, obtaining a service is like executing a method of an object • WSDL defines the following elements – An port. Type is like an object; it consists of a set of operations – An operation is like a method; it is invoked by messages – A message is composed of parts – A part is like a parameter and has an associated type 55

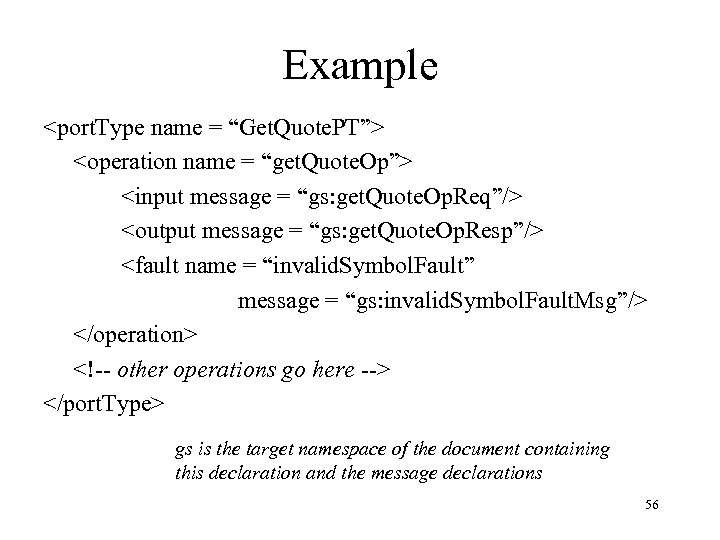

Example <port. Type name = “Get. Quote. PT”> <operation name = “get. Quote. Op”> <input message = “gs: get. Quote. Op. Req”/> <output message = “gs: get. Quote. Op. Resp”/> <fault name = “invalid. Symbol. Fault” message = “gs: invalid. Symbol. Fault. Msg”/> </operation> <!-- other operations go here --> </port. Type> gs is the target namespace of the document containing this declaration and the message declarations 56

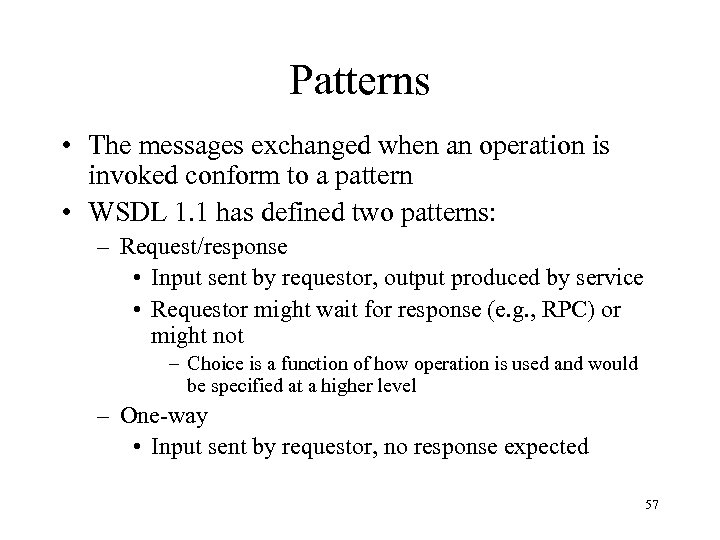

Patterns • The messages exchanged when an operation is invoked conform to a pattern • WSDL 1. 1 has defined two patterns: – Request/response • Input sent by requestor, output produced by service • Requestor might wait for response (e. g. , RPC) or might not – Choice is a function of how operation is used and would be specified at a higher level – One-way • Input sent by requestor, no response expected 57

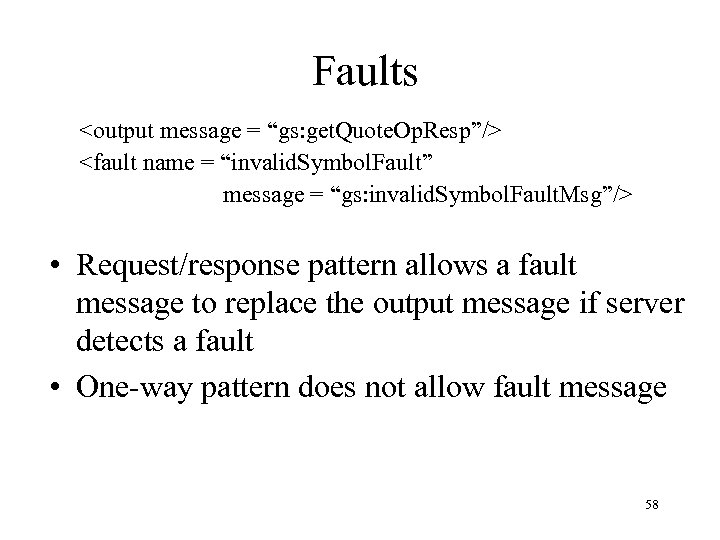

Faults <output message = “gs: get. Quote. Op. Resp”/> <fault name = “invalid. Symbol. Fault” message = “gs: invalid. Symbol. Fault. Msg”/> • Request/response pattern allows a fault message to replace the output message if server detects a fault • One-way pattern does not allow fault message 58

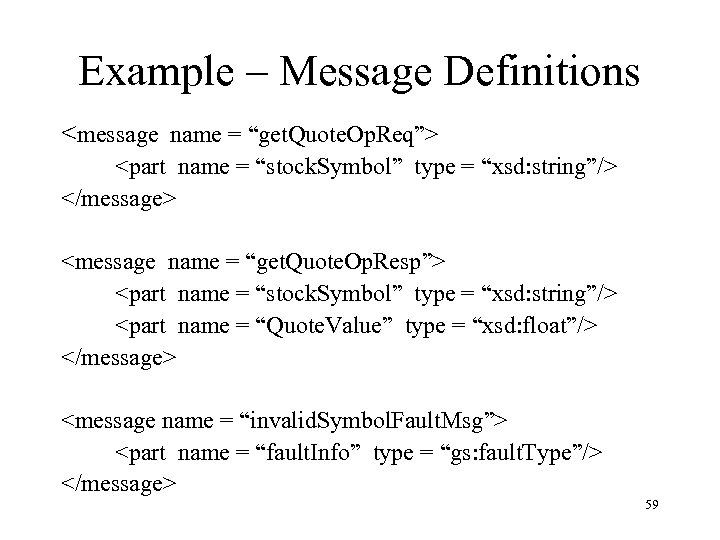

Example – Message Definitions <message name = “get. Quote. Op. Req”> <part name = “stock. Symbol” type = “xsd: string”/> </message> <message name = “get. Quote. Op. Resp”> <part name = “stock. Symbol” type = “xsd: string”/> <part name = “Quote. Value” type = “xsd: float”/> </message> <message name = “invalid. Symbol. Fault. Msg”> <part name = “fault. Info” type = “gs: fault. Type”/> </message> 59

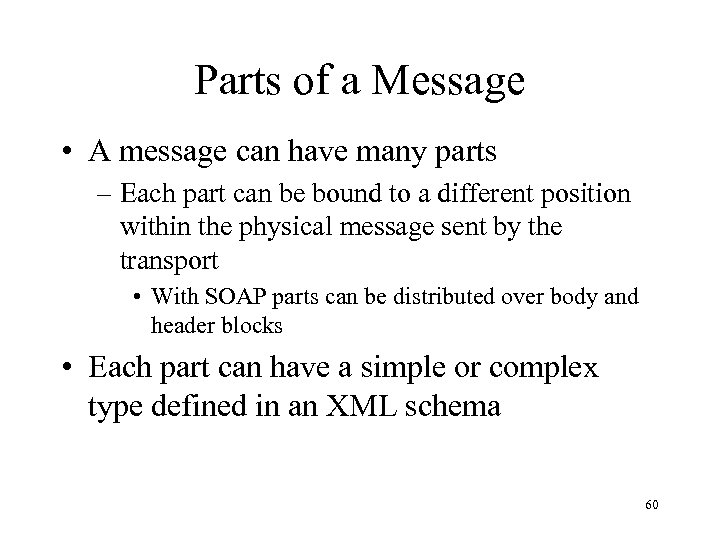

Parts of a Message • A message can have many parts – Each part can be bound to a different position within the physical message sent by the transport • With SOAP parts can be distributed over body and header blocks • Each part can have a simple or complex type defined in an XML schema 60

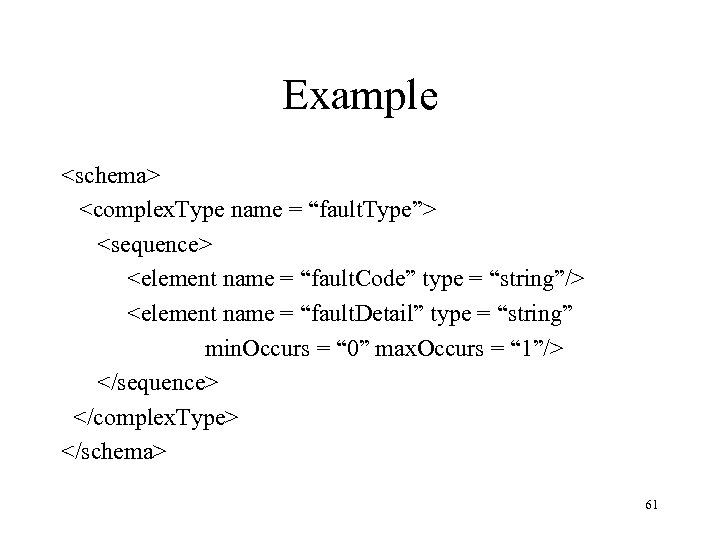

Example <schema> <complex. Type name = “fault. Type”> <sequence> <element name = “fault. Code” type = “string”/> <element name = “fault. Detail” type = “string” min. Occurs = “ 0” max. Occurs = “ 1”/> </sequence> </complex. Type> </schema> 61

Concrete Level • The concrete level defines how port. Types and operations are bound to transports and addresses • A given port. Type can be bound to several different transports and addresses – A Web Service might support a port. Type using several different transports • For example, the operations can be invoked using SOAP over either HTTP or SMTP – The same port. Type might be supported by several different Web Services using the same or different transports – In all of these cases, semantically identical service should be provided at each address 62

Concrete Level • At the concrete level, WSDL defines the following elements – A binding describes how the messages of a port. Type are mapped to the messages of a particular transport – An port maps a binding to a Web address – A service is a collection of ports that host related port. Types 63

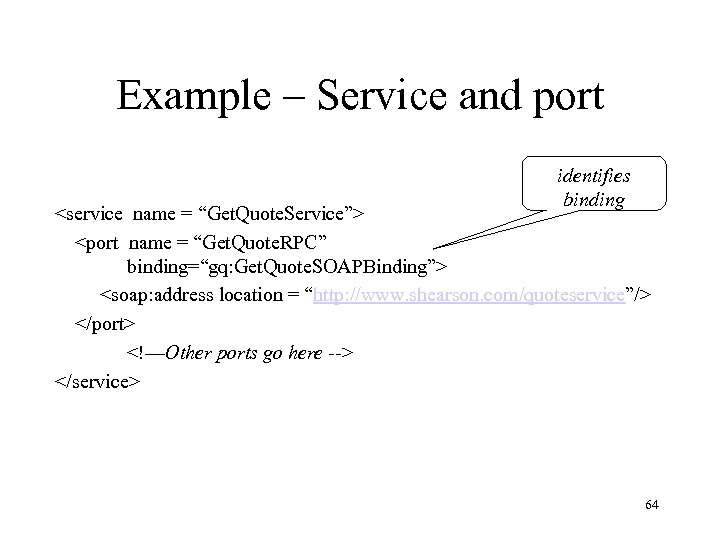

Example – Service and port identifies binding <service name = “Get. Quote. Service”> <port name = “Get. Quote. RPC” binding=“gq: Get. Quote. SOAPBinding”> <soap: address location = “http: //www. shearson. com/quoteservice”/> </port> <!—Other ports go here --> </service> 64

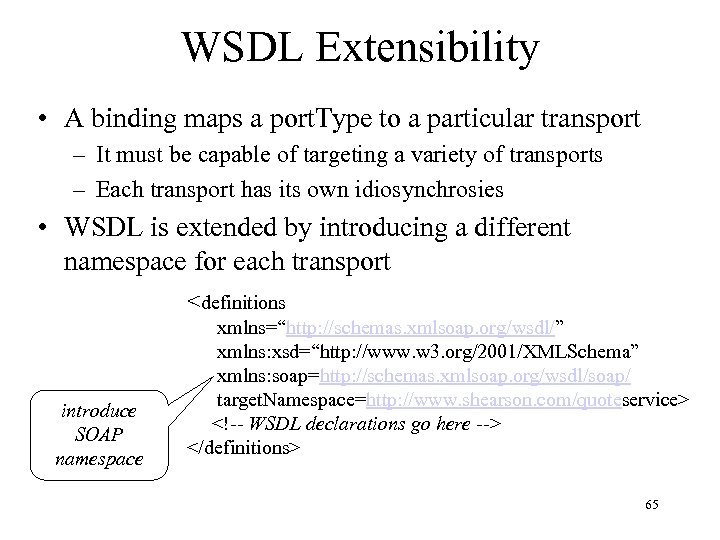

WSDL Extensibility • A binding maps a port. Type to a particular transport – It must be capable of targeting a variety of transports – Each transport has its own idiosynchrosies • WSDL is extended by introducing a different namespace for each transport <definitions introduce SOAP namespace xmlns=“http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/wsdl/” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: soap=http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/wsdl/soap/ target. Namespace=http: //www. shearson. com/quoteservice> <!-- WSDL declarations go here --> </definitions> 65

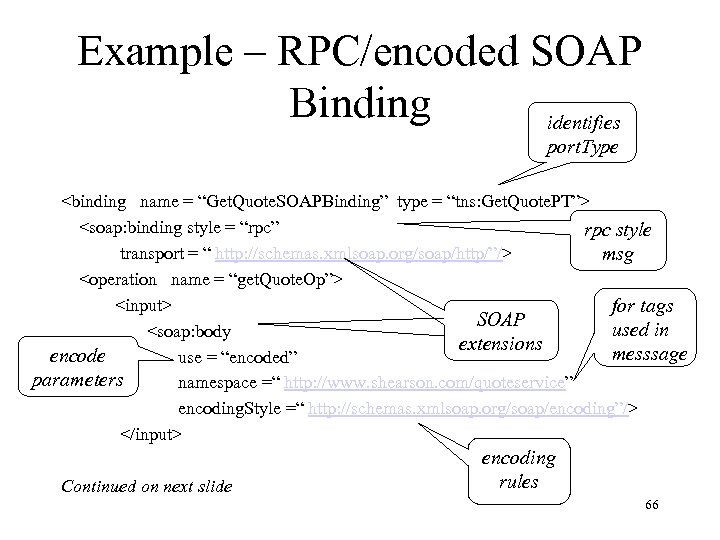

Example – RPC/encoded SOAP Binding identifies port. Type <binding name = “Get. Quote. SOAPBinding” type = “tns: Get. Quote. PT”> <soap: binding style = “rpc” rpc style transport = “ http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/http/”/> msg <operation name = “get. Quote. Op”> <input> for tags SOAP used in <soap: body extensions messsage encode use = “encoded” parameters namespace =“ http: //www. shearson. com/quoteservice” encoding. Style =“ http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/encoding”/> </input> Continued on next slide encoding rules 66

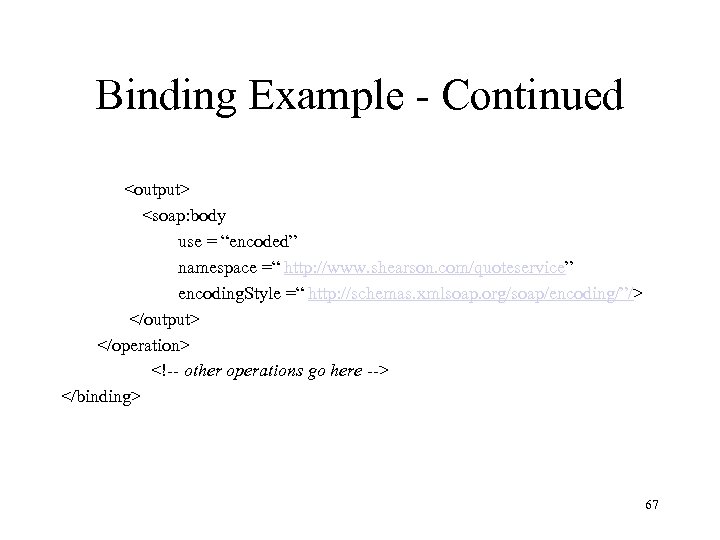

Binding Example - Continued <output> <soap: body use = “encoded” namespace =“ http: //www. shearson. com/quoteservice” encoding. Style =“ http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/encoding/”/> </output> </operation> <!-- other operations go here --> </binding> 67

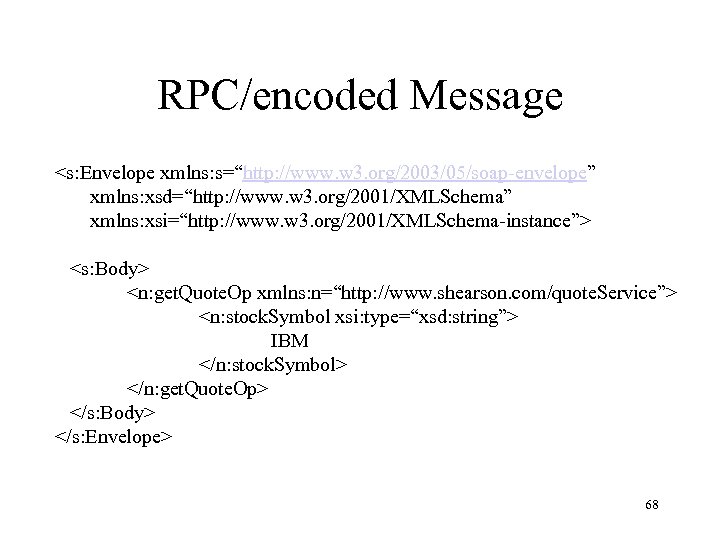

RPC/encoded Message <s: Envelope xmlns: s=“http: //www. w 3. org/2003/05/soap-envelope” xmlns: xsd=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema” xmlns: xsi=“http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema-instance”> <s: Body> <n: get. Quote. Op xmlns: n=“http: //www. shearson. com/quote. Service”> <n: stock. Symbol xsi: type=“xsd: string”> IBM </n: stock. Symbol> </n: get. Quote. Op> </s: Body> </s: Envelope> 68

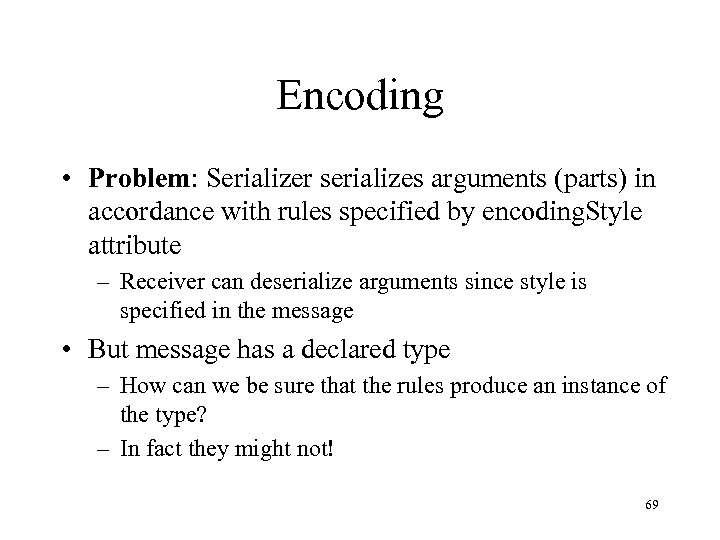

Encoding • Problem: Serializer serializes arguments (parts) in accordance with rules specified by encoding. Style attribute – Receiver can deserialize arguments since style is specified in the message • But message has a declared type – How can we be sure that the rules produce an instance of the type? – In fact they might not! 69

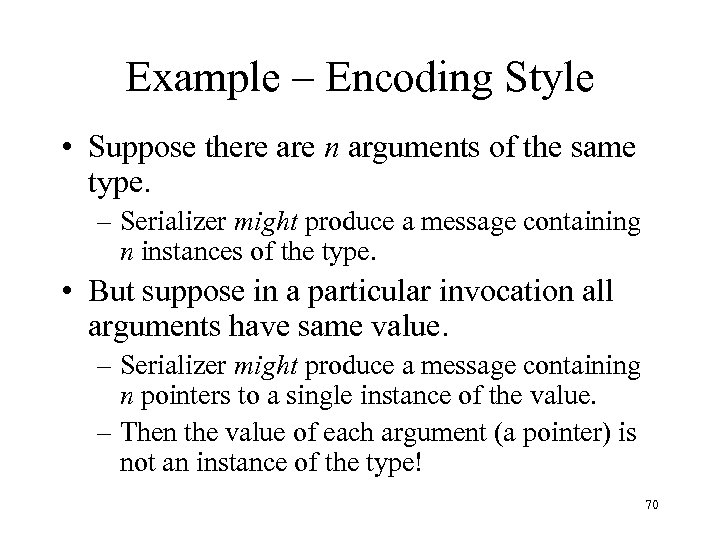

Example – Encoding Style • Suppose there are n arguments of the same type. – Serializer might produce a message containing n instances of the type. • But suppose in a particular invocation all arguments have same value. – Serializer might produce a message containing n pointers to a single instance of the value. – Then the value of each argument (a pointer) is not an instance of the type! 70

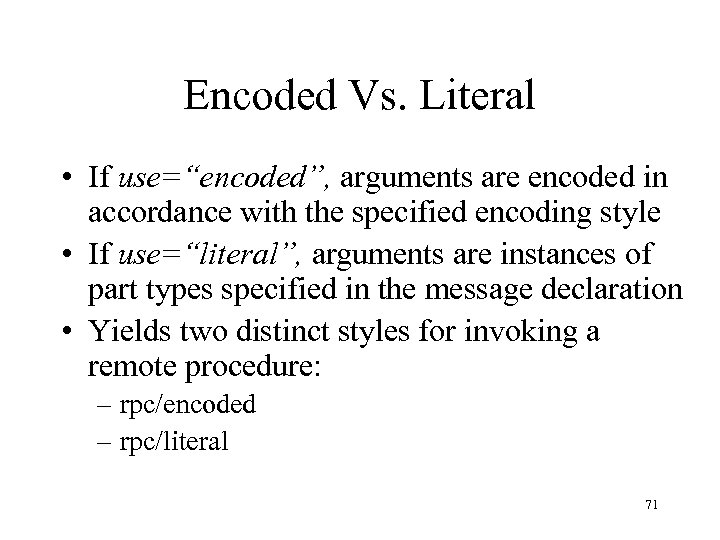

Encoded Vs. Literal • If use=“encoded”, arguments are encoded in accordance with the specified encoding style • If use=“literal”, arguments are instances of part types specified in the message declaration • Yields two distinct styles for invoking a remote procedure: – rpc/encoded – rpc/literal 71

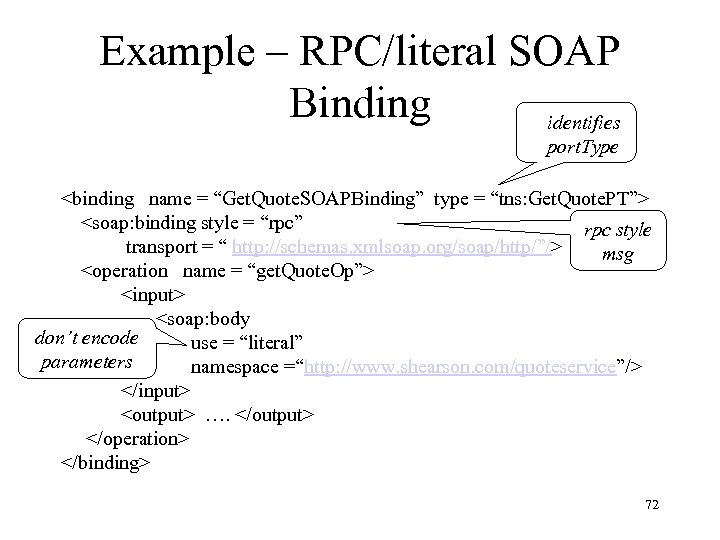

Example – RPC/literal SOAP Binding identifies port. Type <binding name = “Get. Quote. SOAPBinding” type = “tns: Get. Quote. PT”> <soap: binding style = “rpc” rpc style transport = “ http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/http/”/> msg <operation name = “get. Quote. Op”> <input> <soap: body don’t encode use = “literal” parameters namespace =“http: //www. shearson. com/quoteservice”/> </input> <output> …. </output> </operation> </binding> 72

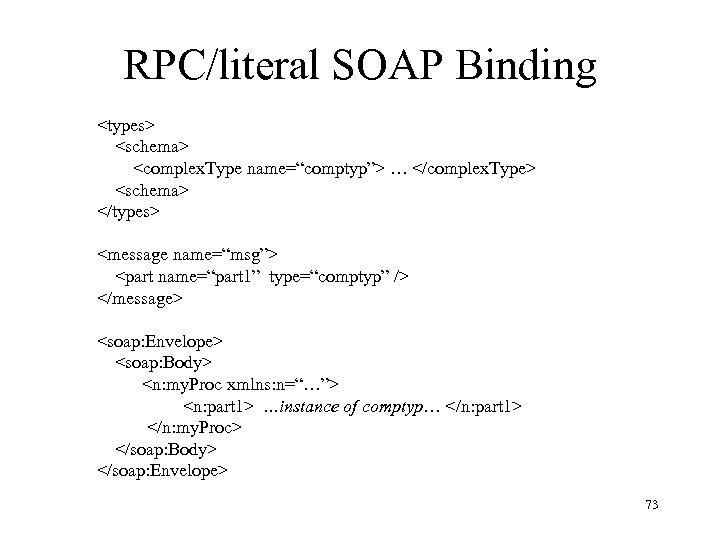

RPC/literal SOAP Binding <types> <schema> <complex. Type name=“comptyp”> … </complex. Type> <schema> </types> <message name=“msg”> <part name=“part 1” type=“comptyp” /> </message> <soap: Envelope> <soap: Body> <n: my. Proc xmlns: n=“…”> <n: part 1> …instance of comptyp… </n: part 1> </n: my. Proc> </soap: Body> </soap: Envelope> 73

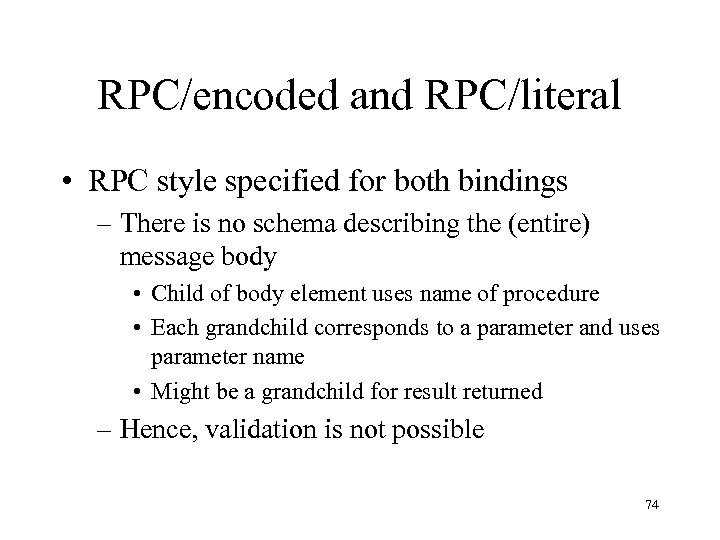

RPC/encoded and RPC/literal • RPC style specified for both bindings – There is no schema describing the (entire) message body • Child of body element uses name of procedure • Each grandchild corresponds to a parameter and uses parameter name • Might be a grandchild for result returned – Hence, validation is not possible 74

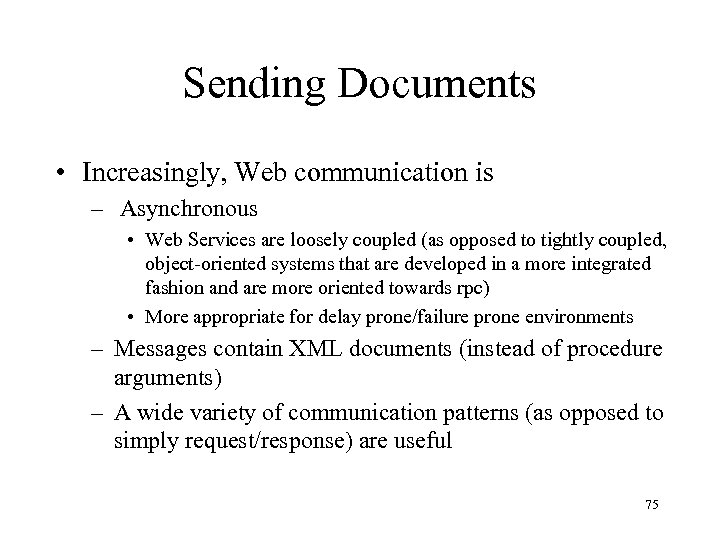

Sending Documents • Increasingly, Web communication is – Asynchronous • Web Services are loosely coupled (as opposed to tightly coupled, object-oriented systems that are developed in a more integrated fashion and are more oriented towards rpc) • More appropriate for delay prone/failure prone environments – Messages contain XML documents (instead of procedure arguments) – A wide variety of communication patterns (as opposed to simply request/response) are useful 75

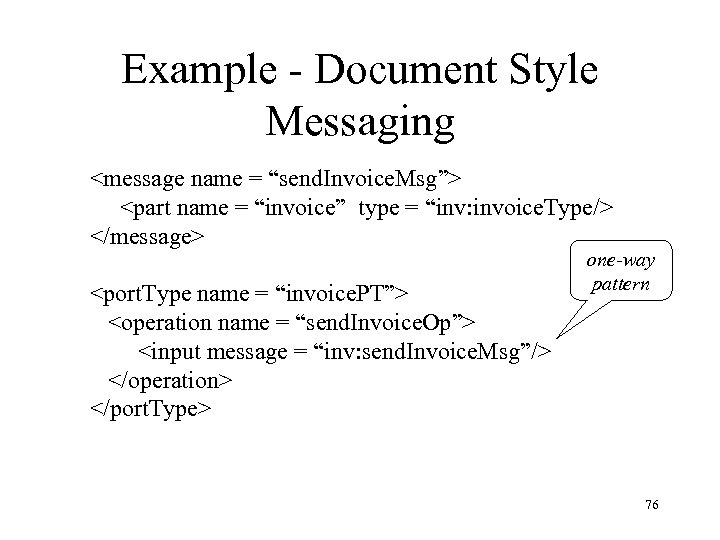

Example - Document Style Messaging <message name = “send. Invoice. Msg”> <part name = “invoice” type = “inv: invoice. Type/> </message> <port. Type name = “invoice. PT”> <operation name = “send. Invoice. Op”> <input message = “inv: send. Invoice. Msg”/> </operation> </port. Type> one-way pattern 76

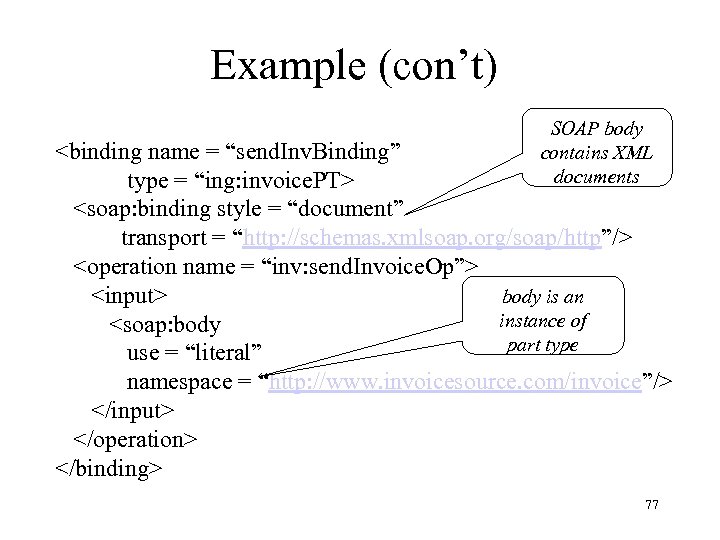

Example (con’t) SOAP body contains XML documents <binding name = “send. Inv. Binding” type = “ing: invoice. PT> <soap: binding style = “document” transport = “http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/http”/> <operation name = “inv: send. Invoice. Op”> body is an <input> instance of <soap: body part type use = “literal” namespace = “http: //www. invoicesource. com/invoice”/> </input> </operation> </binding> 77

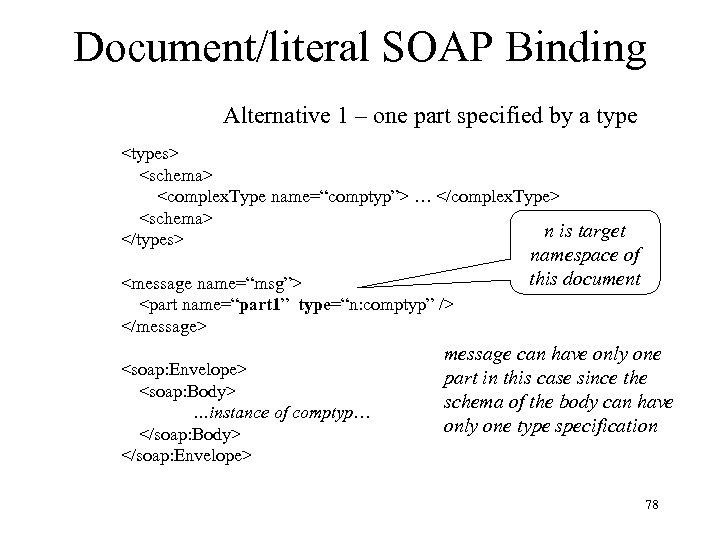

Document/literal SOAP Binding Alternative 1 – one part specified by a type <types> <schema> <complex. Type name=“comptyp”> … </complex. Type> <schema> n is target </types> <message name=“msg”> <part name=“part 1” type=“n: comptyp” /> </message> <soap: Envelope> <soap: Body> …instance of comptyp… </soap: Body> </soap: Envelope> namespace of this document message can have only one part in this case since the schema of the body can have only one type specification 78

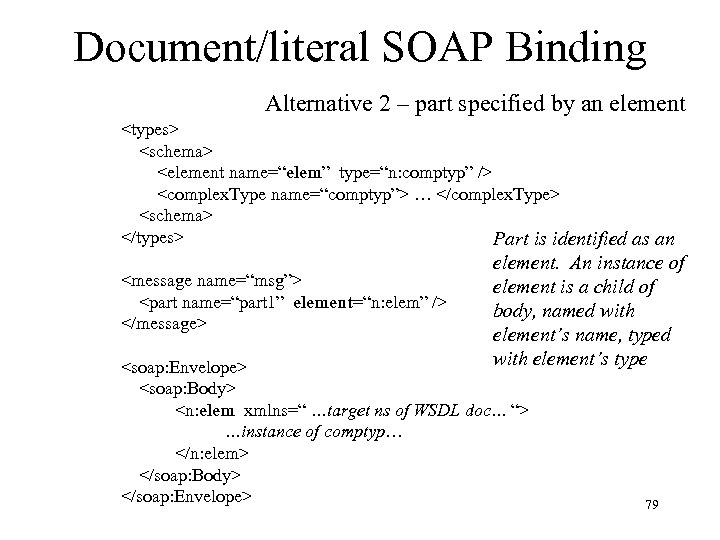

Document/literal SOAP Binding Alternative 2 – part specified by an element <types> <schema> <element name=“elem” type=“n: comptyp” /> <complex. Type name=“comptyp”> … </complex. Type> <schema> </types> Part is identified as an <message name=“msg”> <part name=“part 1” element=“n: elem” /> </message> element. An instance of element is a child of body, named with element’s name, typed with element’s type <soap: Envelope> <soap: Body> <n: elem xmlns=“ …target ns of WSDL doc… “> …instance of comptyp… </n: elem> </soap: Body> </soap: Envelope> 79

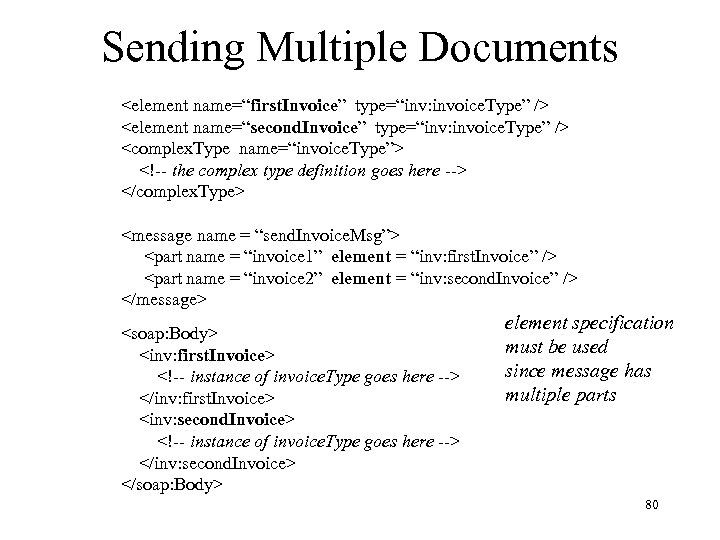

Sending Multiple Documents <element name=“first. Invoice” type=“inv: invoice. Type” /> <element name=“second. Invoice” type=“inv: invoice. Type” /> <complex. Type name=“invoice. Type”> <!-- the complex type definition goes here --> </complex. Type> <message name = “send. Invoice. Msg”> <part name = “invoice 1” element = “inv: first. Invoice” /> <part name = “invoice 2” element = “inv: second. Invoice” /> </message> <soap: Body> <inv: first. Invoice> <!-- instance of invoice. Type goes here --> </inv: first. Invoice> <inv: second. Invoice> <!-- instance of invoice. Type goes here --> </inv: second. Invoice> </soap: Body> element specification must be used since message has multiple parts 80

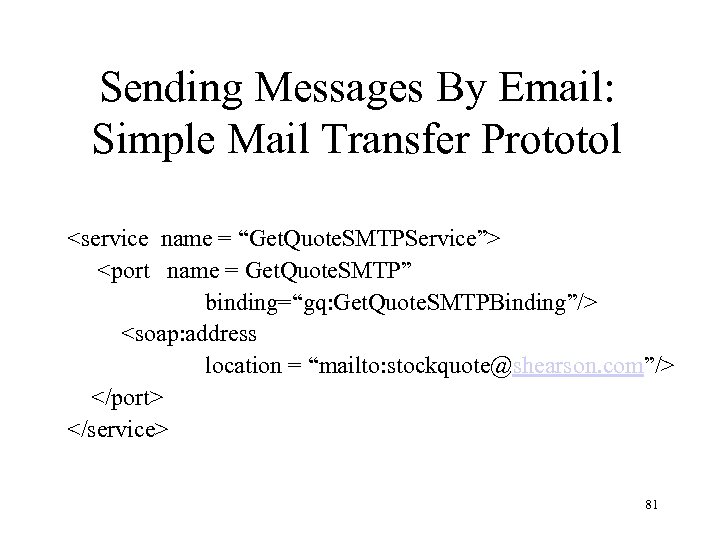

Sending Messages By Email: Simple Mail Transfer Prototol <service name = “Get. Quote. SMTPService”> <port name = Get. Quote. SMTP” binding=“gq: Get. Quote. SMTPBinding”/> <soap: address location = “mailto: stockquote@shearson. com”/> </port> </service> 81

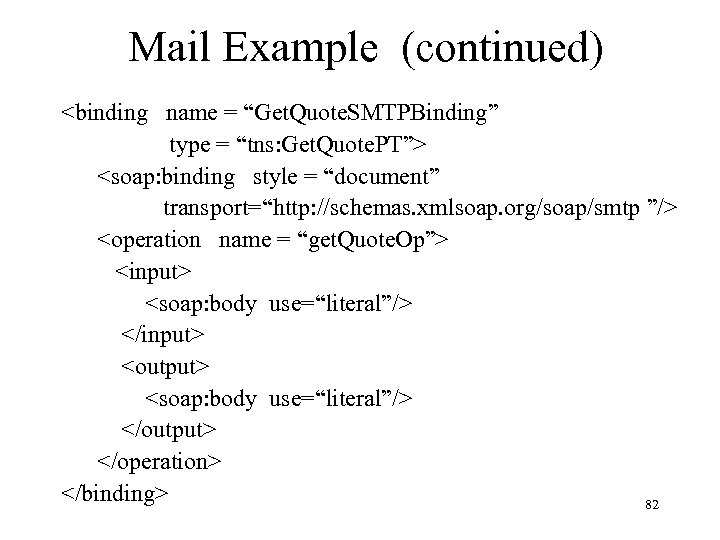

Mail Example (continued) <binding name = “Get. Quote. SMTPBinding” type = “tns: Get. Quote. PT”> <soap: binding style = “document” transport=“http: //schemas. xmlsoap. org/soap/smtp ”/> <operation name = “get. Quote. Op”> <input> <soap: body use=“literal”/> </input> <output> <soap: body use=“literal”/> </output> </operation> </binding> 82

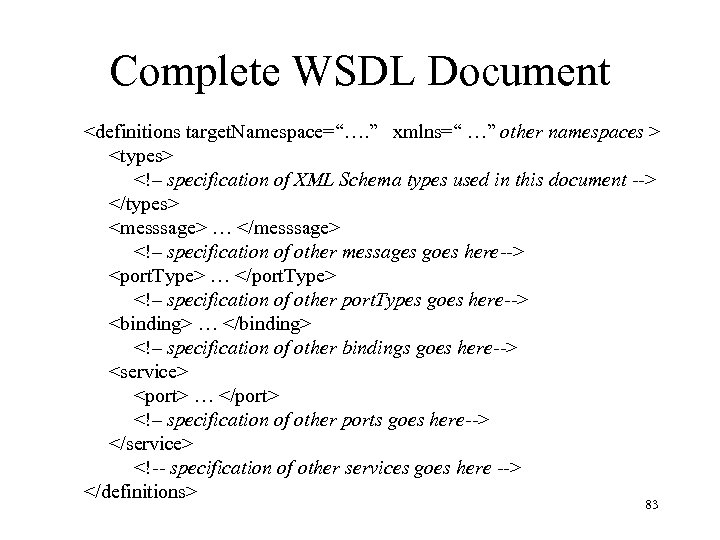

Complete WSDL Document <definitions target. Namespace=“…. ” xmlns=“ …” other namespaces > <types> <!– specification of XML Schema types used in this document --> </types> <messsage> … </messsage> <!– specification of other messages goes here--> <port. Type> … </port. Type> <!– specification of other port. Types goes here--> <binding> … </binding> <!– specification of other bindings goes here--> <service> <port> … </port> <!– specification of other ports goes here--> </service> <!-- specification of other services goes here --> </definitions> 83

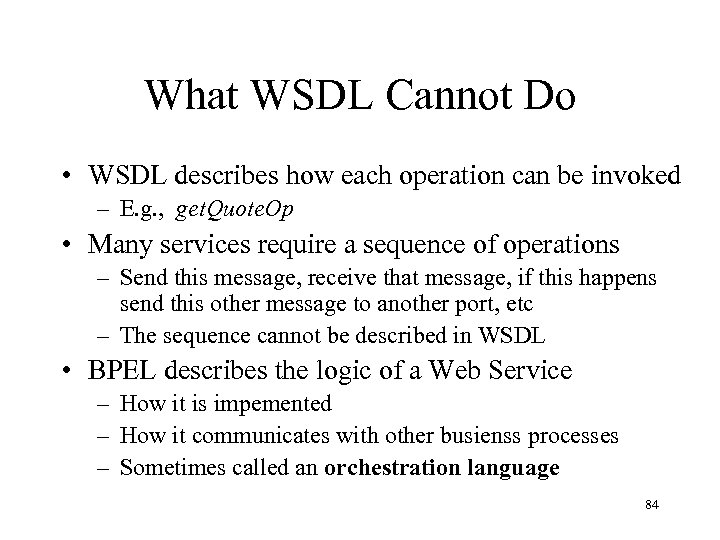

What WSDL Cannot Do • WSDL describes how each operation can be invoked – E. g. , get. Quote. Op • Many services require a sequence of operations – Send this message, receive that message, if this happens send this other message to another port, etc – The sequence cannot be described in WSDL • BPEL describes the logic of a Web Service – How it is impemented – How it communicates with other busienss processes – Sometimes called an orchestration language 84

Business Process Execution Language for Web Services (BPEL 4 WS) Version 1. 1

BPEL vs. WSDL • WSDL supports a stateless model which describes operations supported by web servers – One or two messages needed for client/server communication – No mechanism for describing state between operations • A business process (BP) typically characterized by long-running, statefull sequence of operations with one or more web services (business partners). 86

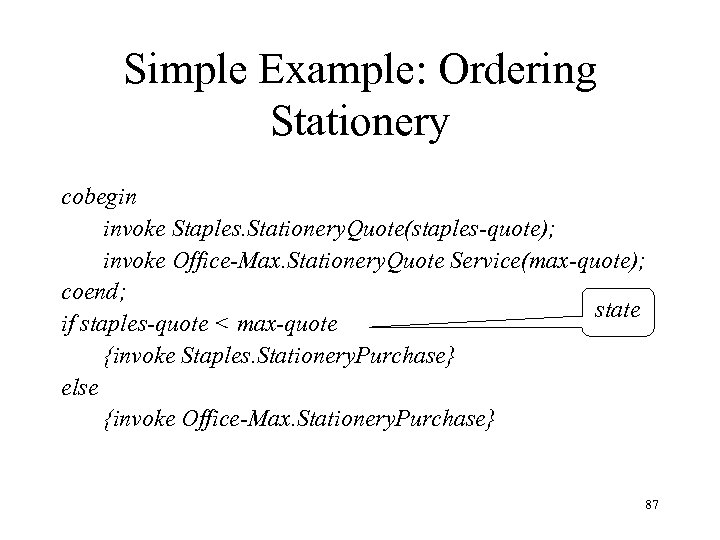

Simple Example: Ordering Stationery cobegin invoke Staples. Stationery. Quote(staples-quote); invoke Office-Max. Stationery. Quote Service(max-quote); coend; state if staples-quote < max-quote {invoke Staples. Stationery. Purchase} else {invoke Office-Max. Stationery. Purchase} 87

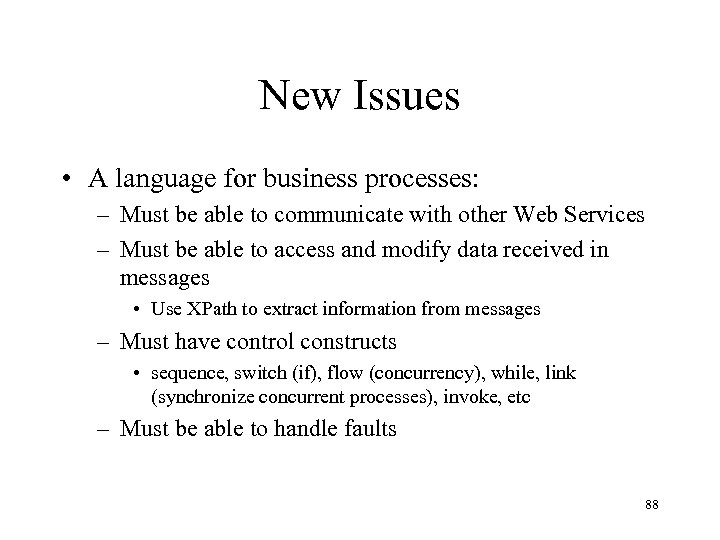

New Issues • A language for business processes: – Must be able to communicate with other Web Services – Must be able to access and modify data received in messages • Use XPath to extract information from messages – Must have control constructs • sequence, switch (if), flow (concurrency), while, link (synchronize concurrent processes), invoke, etc – Must be able to handle faults 88

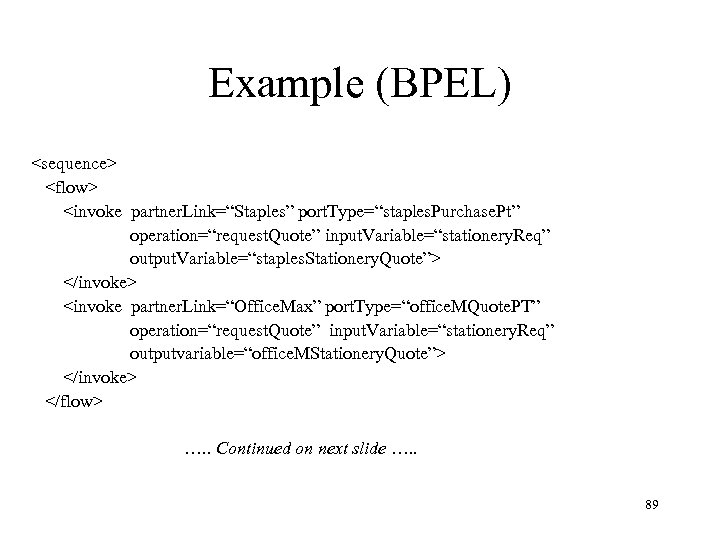

Example (BPEL) <sequence> <flow> <invoke partner. Link=“Staples” port. Type=“staples. Purchase. Pt” operation=“request. Quote” input. Variable=“stationery. Req” output. Variable=“staples. Stationery. Quote”> </invoke> <invoke partner. Link=“Office. Max” port. Type=“office. MQuote. PT” operation=“request. Quote” input. Variable=“stationery. Req” outputvariable=“office. MStationery. Quote”> </invoke> </flow> …. . Continued on next slide …. . 89

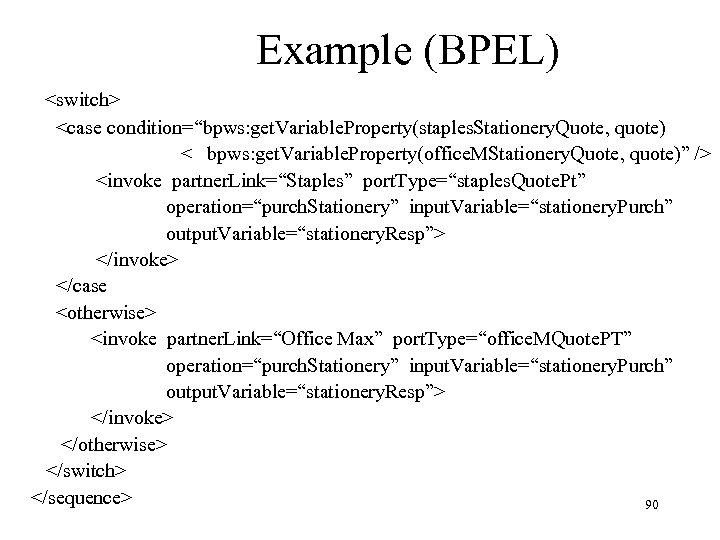

Example (BPEL) <switch> <case condition=“bpws: get. Variable. Property(staples. Stationery. Quote, quote) < bpws: get. Variable. Property(office. MStationery. Quote, quote)” /> <invoke partner. Link=“Staples” port. Type=“staples. Quote. Pt” operation=“purch. Stationery” input. Variable=“stationery. Purch” output. Variable=“stationery. Resp”> </invoke> </case <otherwise> <invoke partner. Link=“Office Max” port. Type=“office. MQuote. PT” operation=“purch. Stationery” input. Variable=“stationery. Purch” output. Variable=“stationery. Resp”> </invoke> </otherwise> </switch> </sequence> 90

Business Process (BP) • A BP consists of both internal computations and invocations of operations exported by Web service partners • The operations it exports constitute its interface to its partners • The sequence of invocations it executes is referred to as a protocol and – is data dependent – responds to exceptional conditions 91

Abstract Vs. Executable BPs • Executable BP – complete description of BP (including all computations) • Abstract BP – contains only externally visible (communication related) behavior of BP – Not executable – Intention: Internal decision making algorithm and data manipulation not described (although this is not enforced) • Languages for describing abstract and executable BPs share a common core, but differ primarily in data handling capabilities • BPEL 4 WS is used to specify both abstract and executable BPs 92

Executable BPs • BPEL is sufficient for describing a complete (executable) BP that – Relies on Web services and XML data – Is portable (platform independent) • Executable BP is a complete specification of the Web service – Actual implementation, however, might not use BPEL, • Abstract BP specifies external interface and can be exported for use by business partners 93

Abstract BP • Unfolding of protocol related portion of BP – depends on properties - a subset of the data contained in messages – Ex. Message invoking get. Quote. Request might have parts instrument. Type (with value stock or bond) and symbol (which identifies a particular instrument of that type) • instrument. Type will be a property if it affects the course of the protocol • symbol will not if it does not affect the course of the protocol • Only properties are visible to abstract BP 94

Abstract Vs Executable BP • Internal computation of executable BP not included in abstract BP – If assignment is to a variable that is not a property, it is eliminated from abstract process • Ex. Address data might not affect the protocol – If assignment is to a variable that is a property, it (generally) affects the protocol • Ex. Value of bid. Price might affect protocol: – if (bid. Price>1000) invoke web. Service 1 else invoke web. Service 2 – bid. Price will be a property, but its value is computed by an internal algorithm • The computation that produces the new value is generally not relevant to the protocol 95

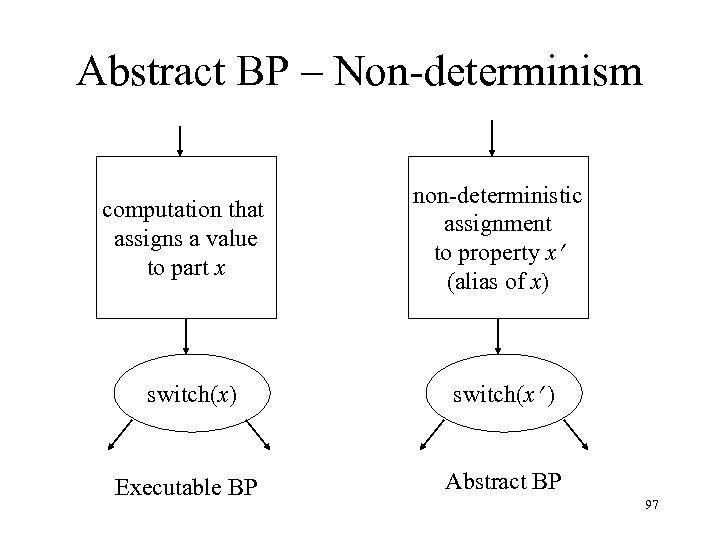

Abstract BP – Non-determinism • Description of abstract BP allows assignment of non -deterministic values to properties to model this • Abstract and executable BPs differ in data handling ability – Executable can explicitly manipulate all data – Abstract can access only properties and can assign non-deterministic values to them – Executable cannot assign non-deterministic values to anything 96

Abstract BP – Non-determinism computation that assigns a value to part x non-deterministic assignment to property x (alias of x) switch(x ) Executable BP Abstract BP 97

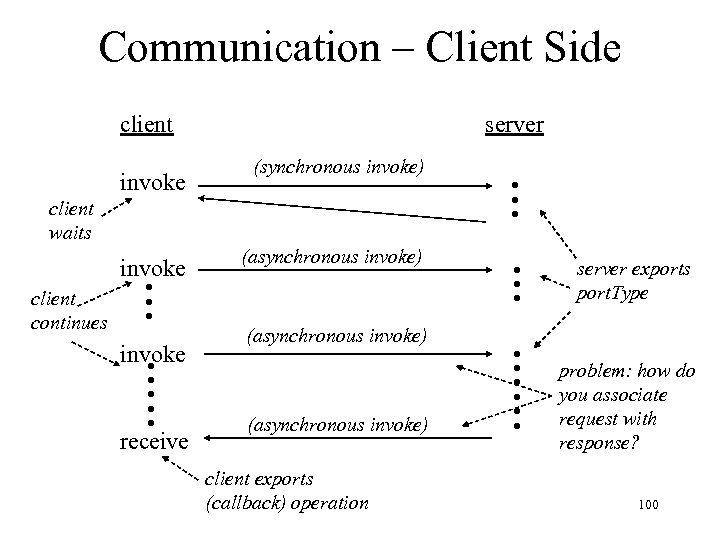

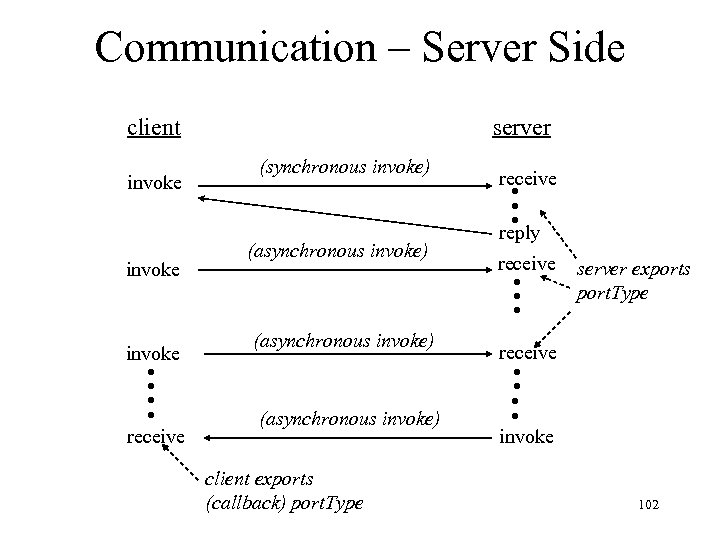

Communication – Client Side • Invoking an operation of a port. Type (specified in WSDL) exported by server – Client assigns message to operation’s input variable – Client executes invoke on operation • Asynchronous (one-way WSDL pattern): – Client resumes execution immediately • Synchronous (request/response WSDL pattern): – Client waits for response and then resumes execution » Synchronization imposed by BPEL – Client can access response message in operation’s output variable 98

Communication – Client Side • Receiving an invocation of an operation exported by client – Client executes receive on operation – Client waits for message – Client can access message in variable associated with operation and resume execution – Ex: an asynchronous response to a prior invocation on a callback port. Type 99

Communication – Client Side client (synchronous invoke) invoke • • • • • client continues (asynchronous invoke) receive • • • client waits server exports port. Type • • • invoke server problem: how do you associate request with response? (asynchronous invoke) client exports (callback) operation 100

Communication – Server Side • Accepting an operation invocation on an (exported) port. Type (specified in WSDL) – Server executes receive on operation and waits • Responding to a synchronous operation invocation – Server executes reply on operation (rpc) • Invoking a client’s exported (callback) operation – Server executes invoke on operation 101

Communication – Server Side client receive • • • (asynchronous invoke) reply (asynchronous invoke) server exports port. Type receive (asynchronous invoke) client exports (callback) port. Type • • • • invoke receive • • invoke (synchronous invoke) • • • invoke server invoke 102

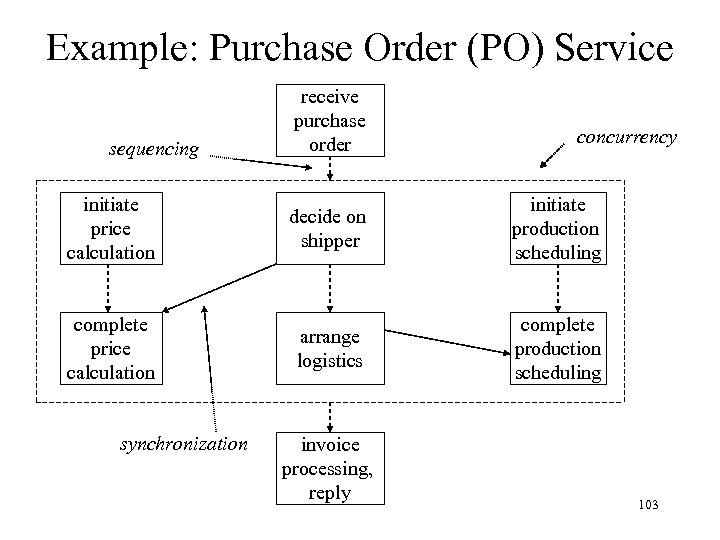

Example: Purchase Order (PO) Service sequencing receive purchase order concurrency initiate price calculation decide on shipper initiate production scheduling complete price calculation arrange logistics complete production scheduling synchronization invoice processing, reply 103

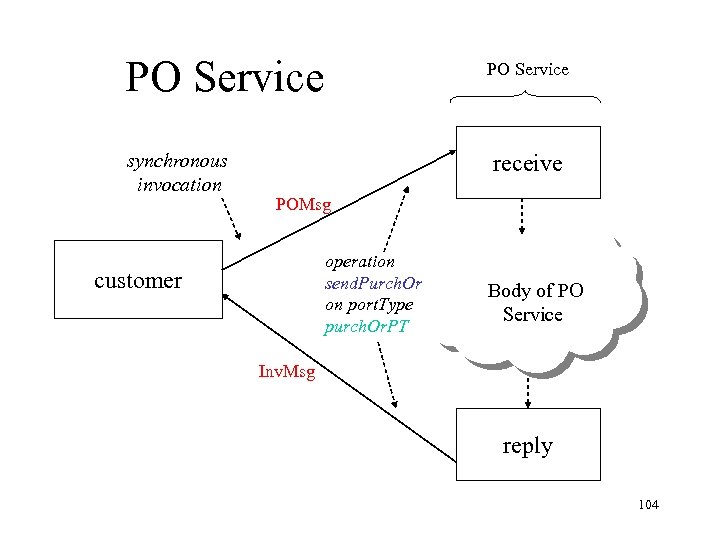

PO Service synchronous invocation PO Service receive POMsg operation send. Purch. Or on port. Type purch. Or. PT customer Body of PO Service Inv. Msg reply 104

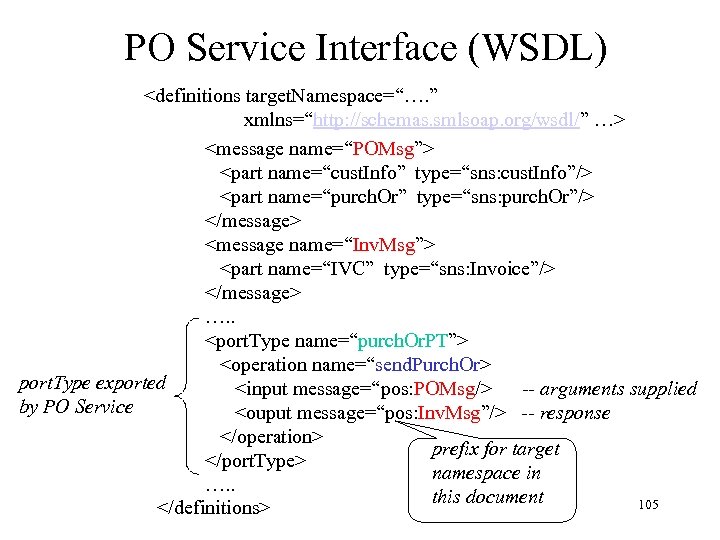

PO Service Interface (WSDL) <definitions target. Namespace=“…. ” xmlns=“http: //schemas. smlsoap. org/wsdl/” …> <message name=“POMsg”> <part name=“cust. Info” type=“sns: cust. Info”/> <part name=“purch. Or” type=“sns: purch. Or”/> </message> <message name=“Inv. Msg”> <part name=“IVC” type=“sns: Invoice”/> </message> …. . <port. Type name=“purch. Or. PT”> <operation name=“send. Purch. Or> port. Type exported <input message=“pos: POMsg/> -- arguments supplied by PO Service <ouput message=“pos: Inv. Msg”/> -- response </operation> prefix for target </port. Type> namespace in …. . this document 105 </definitions>

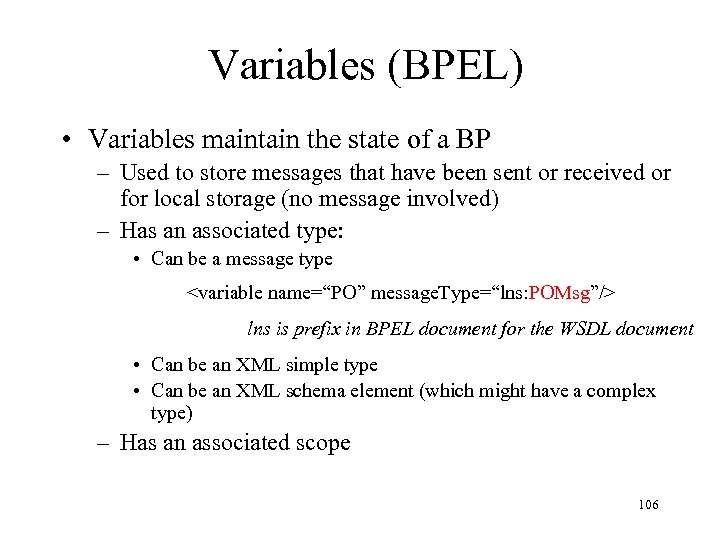

Variables (BPEL) • Variables maintain the state of a BP – Used to store messages that have been sent or received or for local storage (no message involved) – Has an associated type: • Can be a message type <variable name=“PO” message. Type=“lns: POMsg”/> lns is prefix in BPEL document for the WSDL document • Can be an XML simple type • Can be an XML schema element (which might have a complex type) – Has an associated scope 106

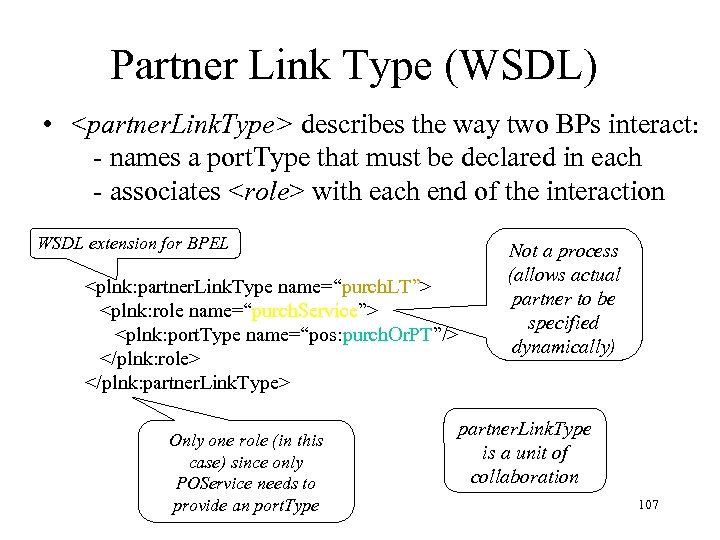

Partner Link Type (WSDL) • <partner. Link. Type> describes the way two BPs interact: - names a port. Type that must be declared in each - associates <role> with each end of the interaction WSDL extension for BPEL <plnk: partner. Link. Type name=“purch. LT”> <plnk: role name=“purch. Service”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: purch. Or. PT”/> </plnk: role> </plnk: partner. Link. Type> Only one role (in this case) since only POService needs to provide an port. Type Not a process (allows actual partner to be specified dynamically) partner. Link. Type is a unit of collaboration 107

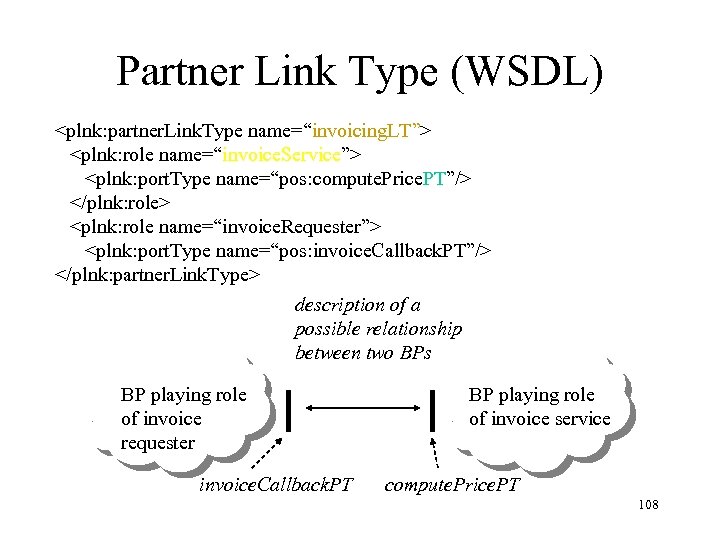

Partner Link Type (WSDL) <plnk: partner. Link. Type name=“invoicing. LT”> <plnk: role name=“invoice. Service”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: compute. Price. PT”/> </plnk: role> <plnk: role name=“invoice. Requester”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: invoice. Callback. PT”/> </plnk: partner. Link. Type> description of a possible relationship between two BPs BP playing role of invoice requester invoice. Callback. PT BP playing role of invoice service compute. Price. PT 108

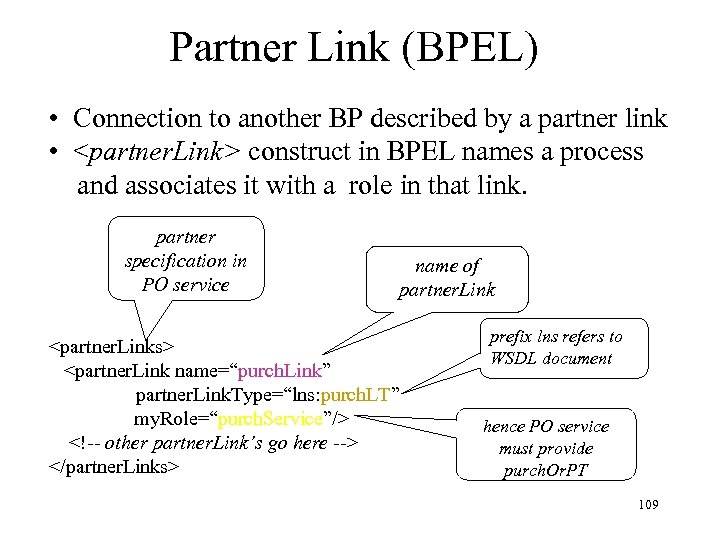

Partner Link (BPEL) • Connection to another BP described by a partner link • <partner. Link> construct in BPEL names a process and associates it with a role in that link. partner specification in PO service name of partner. Link <partner. Links> <partner. Link name=“purch. Link” partner. Link. Type=“lns: purch. LT” my. Role=“purch. Service”/> <!-- other partner. Link’s go here --> </partner. Links> prefix lns refers to WSDL document hence PO service must provide purch. Or. PT 109

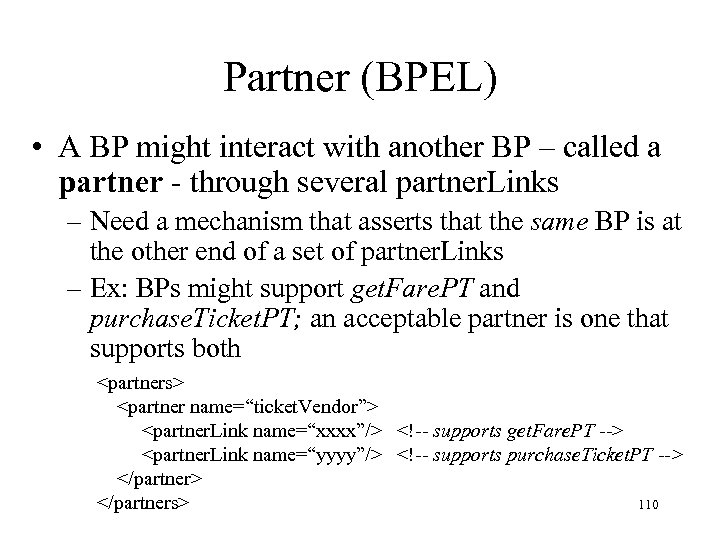

Partner (BPEL) • A BP might interact with another BP – called a partner - through several partner. Links – Need a mechanism that asserts that the same BP is at the other end of a set of partner. Links – Ex: BPs might support get. Fare. PT and purchase. Ticket. PT; an acceptable partner is one that supports both <partners> <partner name=“ticket. Vendor”> <partner. Link name=“xxxx”/> <!-- supports get. Fare. PT --> <partner. Link name=“yyyy”/> <!-- supports purchase. Ticket. PT --> </partners> 110

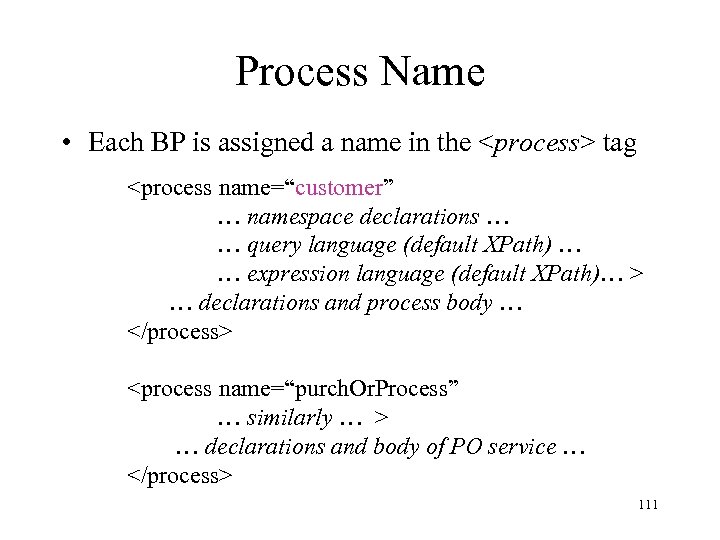

Process Name • Each BP is assigned a name in the <process> tag <process name=“customer” … namespace declarations … … query language (default XPath) … … expression language (default XPath)… > … declarations and process body … </process> <process name=“purch. Or. Process” … similarly … > … declarations and body of PO service … </process> 111

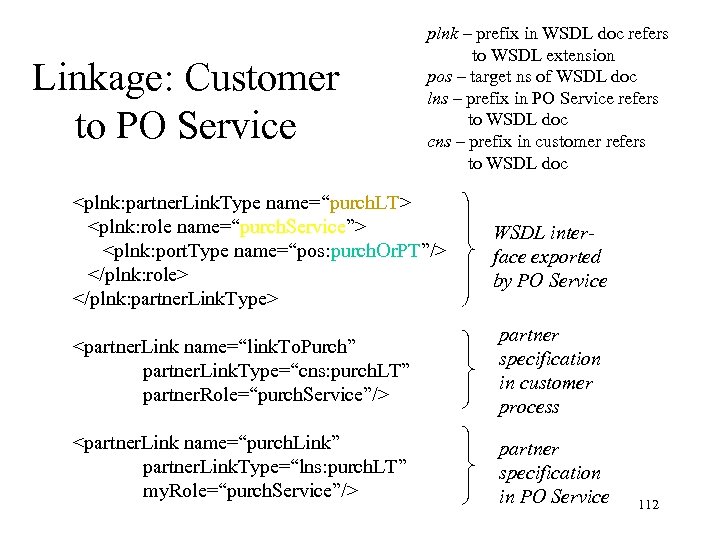

Linkage: Customer to PO Service plnk – prefix in WSDL doc refers to WSDL extension pos – target ns of WSDL doc lns – prefix in PO Service refers to WSDL doc cns – prefix in customer refers to WSDL doc <plnk: partner. Link. Type name=“purch. LT> <plnk: role name=“purch. Service”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: purch. Or. PT”/> </plnk: role> </plnk: partner. Link. Type> WSDL interface exported by PO Service <partner. Link name=“link. To. Purch” partner. Link. Type=“cns: purch. LT” partner. Role=“purch. Service”/> partner specification in customer process <partner. Link name=“purch. Link” partner. Link. Type=“lns: purch. LT” my. Role=“purch. Service”/> partner specification in PO Service 112

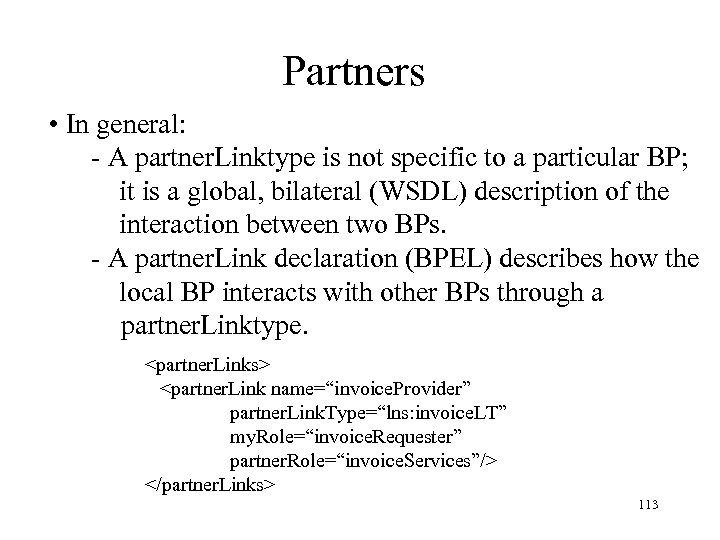

Partners • In general: - A partner. Linktype is not specific to a particular BP; it is a global, bilateral (WSDL) description of the interaction between two BPs. - A partner. Link declaration (BPEL) describes how the local BP interacts with other BPs through a partner. Linktype. <partner. Links> <partner. Link name=“invoice. Provider” partner. Link. Type=“lns: invoice. LT” my. Role=“invoice. Requester” partner. Role=“invoice. Services”/> </partner. Links> 113

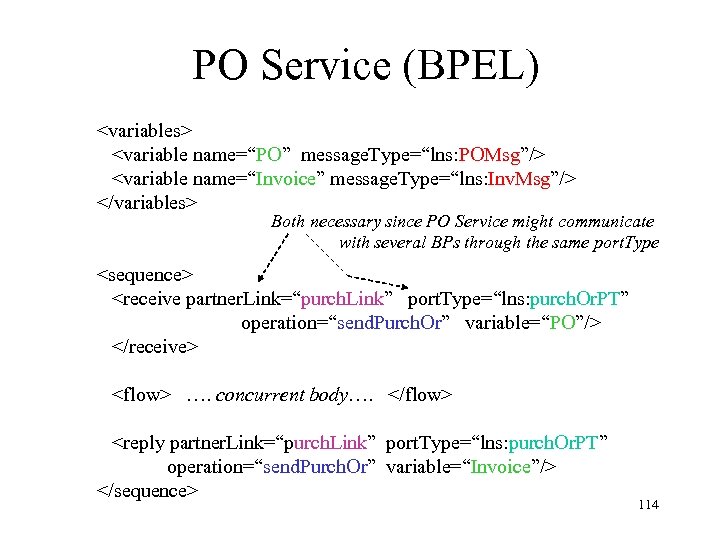

PO Service (BPEL) <variables> <variable name=“PO” message. Type=“lns: POMsg”/> <variable name=“Invoice” message. Type=“lns: Inv. Msg”/> </variables> Both necessary since PO Service might communicate with several BPs through the same port. Type <sequence> <receive partner. Link=“purch. Link” port. Type=“lns: purch. Or. PT” operation=“send. Purch. Or” variable=“PO”/> </receive> <flow> …. concurrent body…. </flow> <reply partner. Link=“purch. Link” port. Type=“lns: purch. Or. PT” operation=“send. Purch. Or” variable=“Invoice”/> </sequence> 114

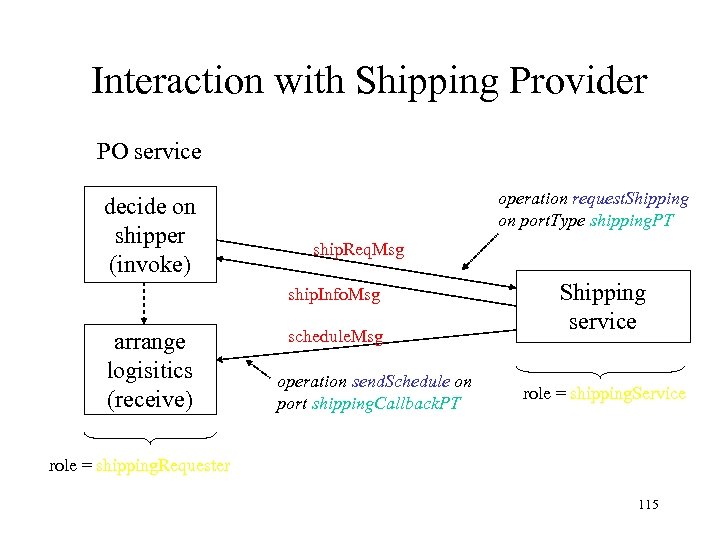

Interaction with Shipping Provider PO service decide on shipper (invoke) operation request. Shipping on port. Type shipping. PT ship. Req. Msg ship. Info. Msg arrange logisitics (receive) schedule. Msg operation send. Schedule on port shipping. Callback. PT Shipping service role = shipping. Service role = shipping. Requester 115

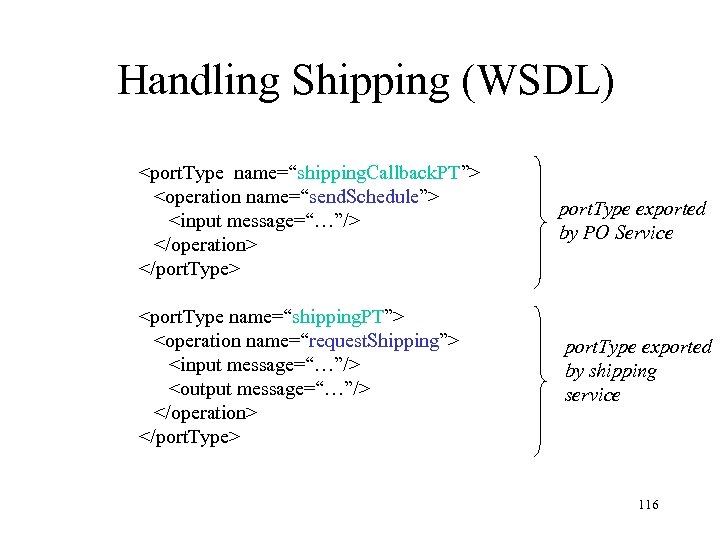

Handling Shipping (WSDL) <port. Type name=“shipping. Callback. PT”> <operation name=“send. Schedule”> <input message=“…”/> </operation> </port. Type> port. Type exported by PO Service <port. Type name=“shipping. PT”> <operation name=“request. Shipping”> <input message=“…”/> <output message=“…”/> </operation> </port. Type> port. Type exported by shipping service 116

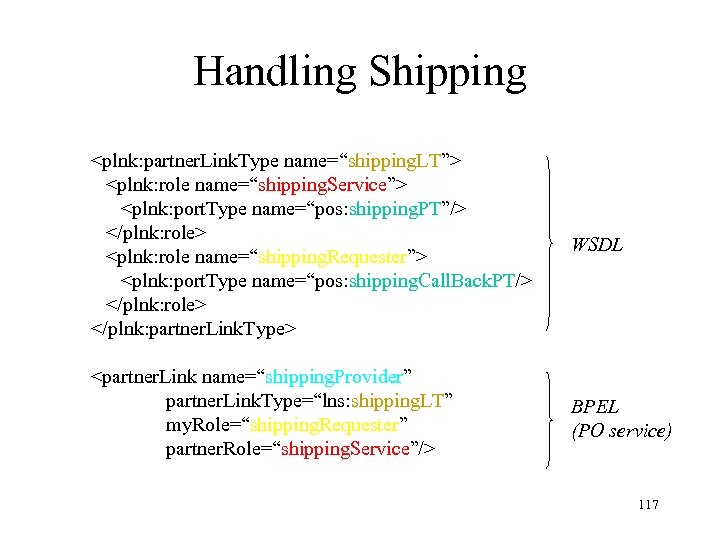

Handling Shipping <plnk: partner. Link. Type name=“shipping. LT”> <plnk: role name=“shipping. Service”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: shipping. PT”/> </plnk: role> <plnk: role name=“shipping. Requester”> <plnk: port. Type name=“pos: shipping. Call. Back. PT/> </plnk: role> </plnk: partner. Link. Type> WSDL <partner. Link name=“shipping. Provider” partner. Link. Type=“lns: shipping. LT” my. Role=“shipping. Requester” partner. Role=“shipping. Service”/> BPEL (PO service) 117

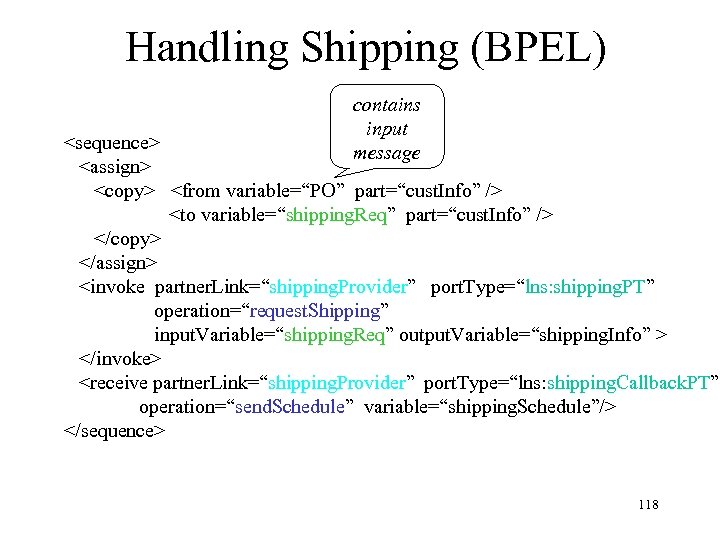

Handling Shipping (BPEL) contains input message <sequence> <assign> <copy> <from variable=“PO” part=“cust. Info” /> <to variable=“shipping. Req” part=“cust. Info” /> </copy> </assign> <invoke partner. Link=“shipping. Provider” port. Type=“lns: shipping. PT” operation=“request. Shipping” input. Variable=“shipping. Req” output. Variable=“shipping. Info” > </invoke> <receive partner. Link=“shipping. Provider” port. Type=“lns: shipping. Callback. PT” operation=“send. Schedule” variable=“shipping. Schedule”/> </sequence> 118

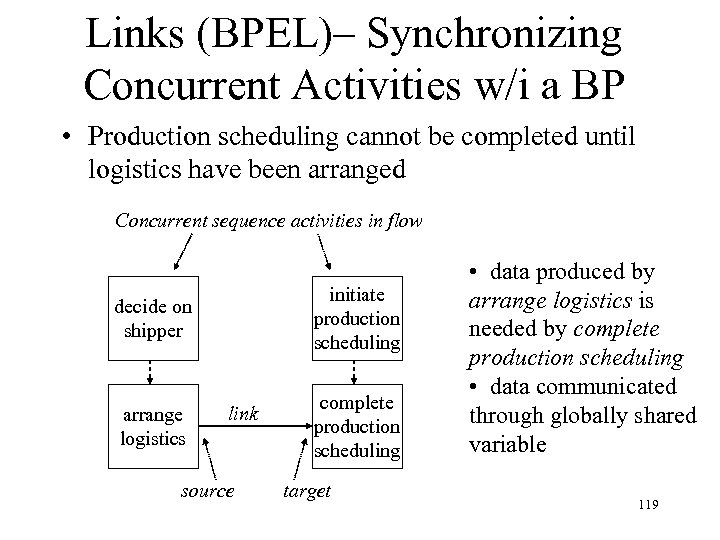

Links (BPEL)– Synchronizing Concurrent Activities w/i a BP • Production scheduling cannot be completed until logistics have been arranged Concurrent sequence activities in flow initiate production scheduling decide on shipper arrange logistics link source complete production scheduling target • data produced by arrange logistics is needed by complete production scheduling • data communicated through globally shared variable 119

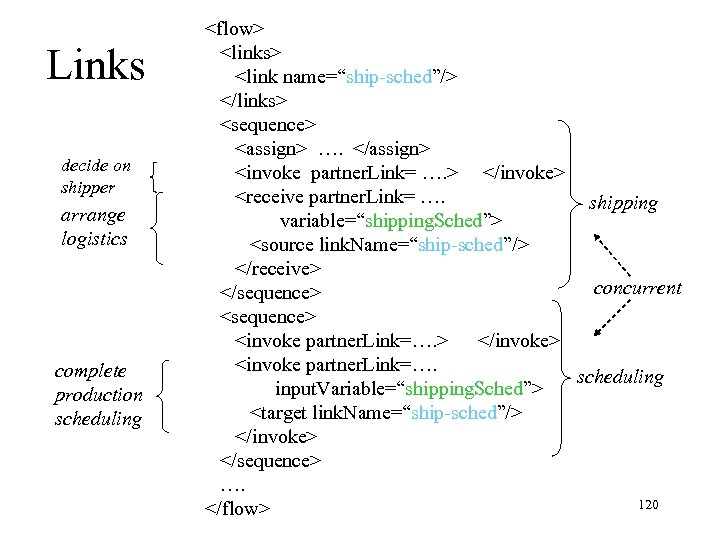

Links decide on shipper arrange logistics complete production scheduling <flow> <links> <link name=“ship-sched”/> </links> <sequence> <assign> …. </assign> <invoke partner. Link= …. > </invoke> <receive partner. Link= …. shipping variable=“shipping. Sched”> <source link. Name=“ship-sched”/> </receive> concurrent </sequence> <invoke partner. Link=…. > </invoke> <invoke partner. Link=…. scheduling input. Variable=“shipping. Sched”> <target link. Name=“ship-sched”/> </invoke> </sequence> …. 120 </flow>

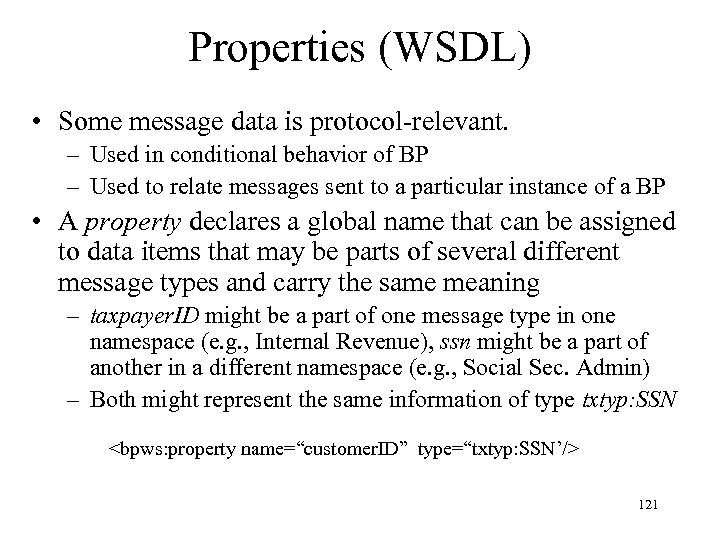

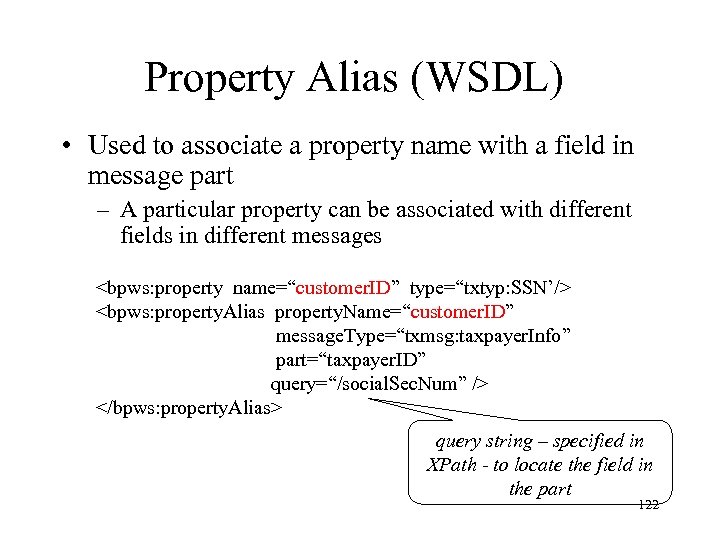

Properties (WSDL) • Some message data is protocol-relevant. – Used in conditional behavior of BP – Used to relate messages sent to a particular instance of a BP • A property declares a global name that can be assigned to data items that may be parts of several different message types and carry the same meaning – taxpayer. ID might be a part of one message type in one namespace (e. g. , Internal Revenue), ssn might be a part of another in a different namespace (e. g. , Social Sec. Admin) – Both might represent the same information of type txtyp: SSN <bpws: property name=“customer. ID” type=“txtyp: SSN’/> 121

Property Alias (WSDL) • Used to associate a property name with a field in message part – A particular property can be associated with different fields in different messages <bpws: property name=“customer. ID” type=“txtyp: SSN’/> <bpws: property. Alias property. Name=“customer. ID” message. Type=“txmsg: taxpayer. Info” part=“taxpayer. ID” query=“/social. Sec. Num” /> </bpws: property. Alias> query string – specified in XPath - to locate the field in the part 122

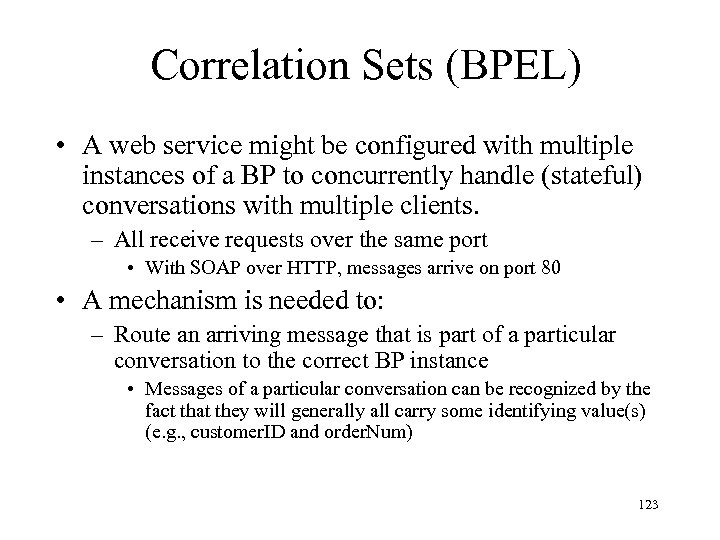

Correlation Sets (BPEL) • A web service might be configured with multiple instances of a BP to concurrently handle (stateful) conversations with multiple clients. – All receive requests over the same port • With SOAP over HTTP, messages arrive on port 80 • A mechanism is needed to: – Route an arriving message that is part of a particular conversation to the correct BP instance • Messages of a particular conversation can be recognized by the fact that they will generally all carry some identifying value(s) (e. g. , customer. ID and order. Num) 123

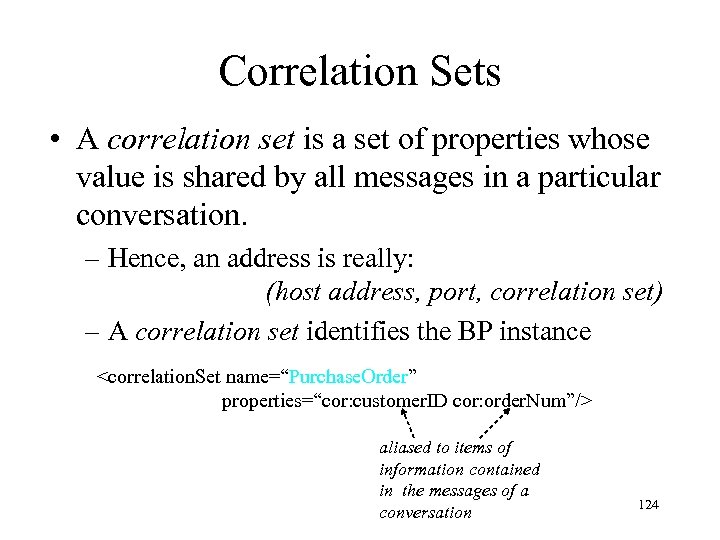

Correlation Sets • A correlation set is a set of properties whose value is shared by all messages in a particular conversation. – Hence, an address is really: (host address, port, correlation set) – A correlation set identifies the BP instance <correlation. Set name=“Purchase. Order” properties=“cor: customer. ID cor: order. Num”/> aliased to items of information contained in the messages of a conversation 124

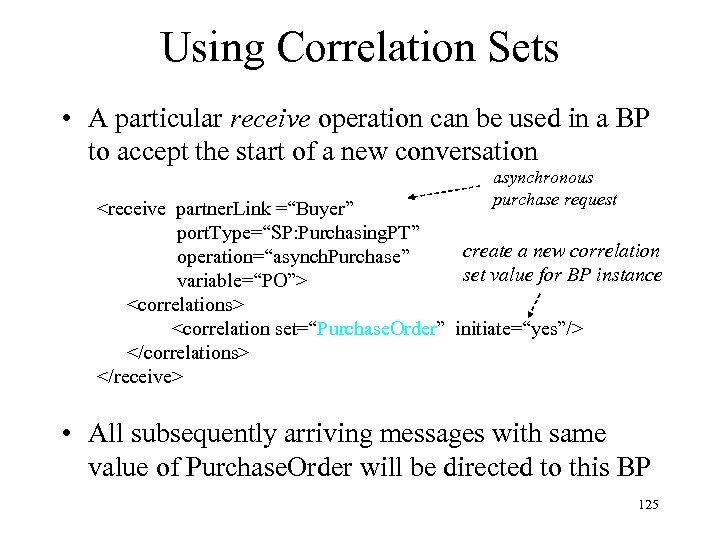

Using Correlation Sets • A particular receive operation can be used in a BP to accept the start of a new conversation asynchronous purchase request <receive partner. Link =“Buyer” port. Type=“SP: Purchasing. PT” create a new correlation operation=“asynch. Purchase” set value for BP instance variable=“PO”> <correlations> <correlation set=“Purchase. Order” initiate=“yes”/> </correlations> </receive> • All subsequently arriving messages with same value of Purchase. Order will be directed to this BP 125

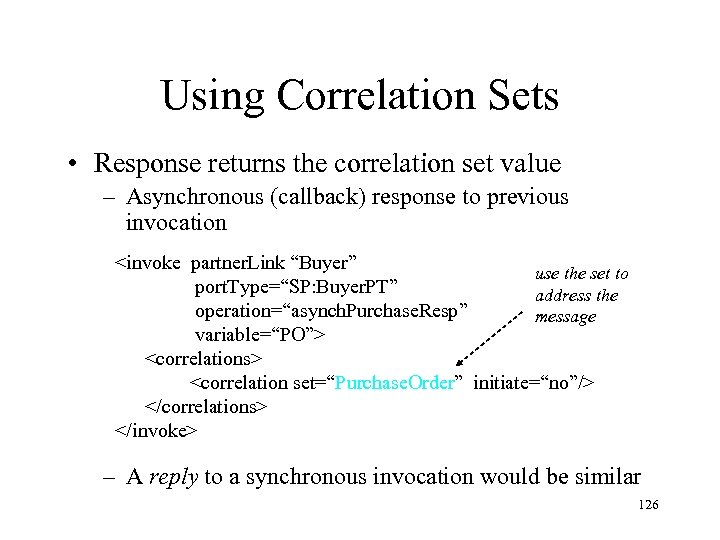

Using Correlation Sets • Response returns the correlation set value – Asynchronous (callback) response to previous invocation <invoke partner. Link “Buyer” use the set to port. Type=“SP: Buyer. PT” address the operation=“asynch. Purchase. Resp” message variable=“PO”> <correlations> <correlation set=“Purchase. Order” initiate=“no”/> </correlations> </invoke> – A reply to a synchronous invocation would be similar 126

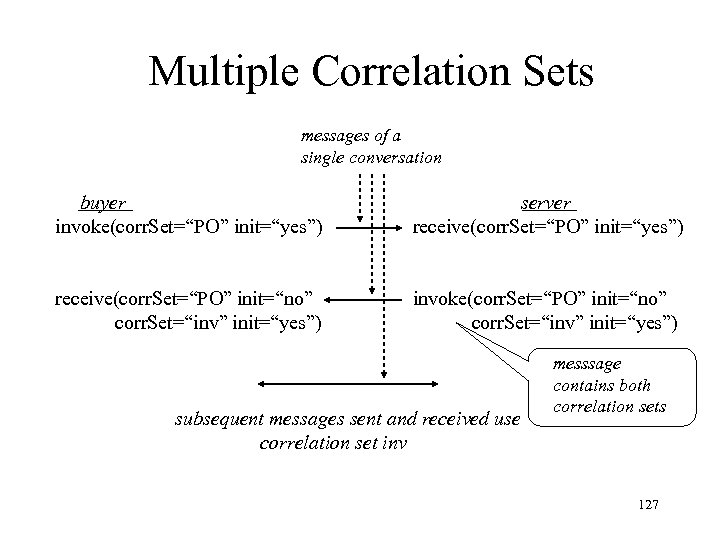

Multiple Correlation Sets messages of a single conversation buyer invoke(corr. Set=“PO” init=“yes”) server receive(corr. Set=“PO” init=“yes”) receive(corr. Set=“PO” init=“no” corr. Set=“inv” init=“yes”) invoke(corr. Set=“PO” init=“no” corr. Set=“inv” init=“yes”) subsequent messages sent and received use correlation set inv messsage contains both correlation sets 127

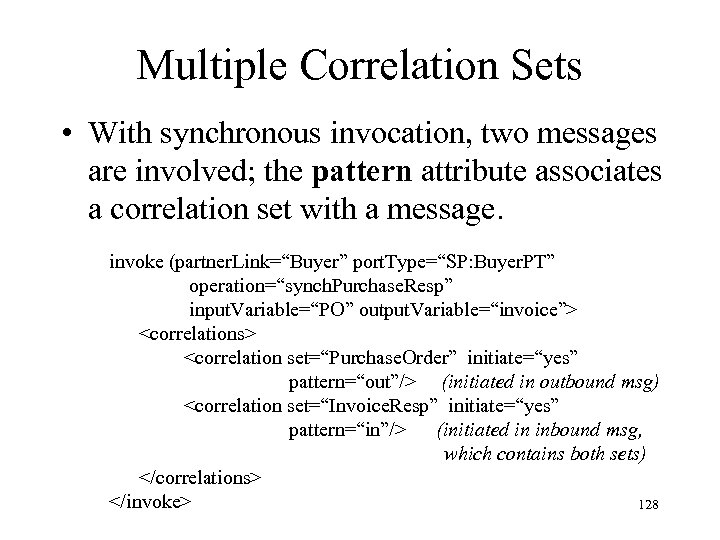

Multiple Correlation Sets • With synchronous invocation, two messages are involved; the pattern attribute associates a correlation set with a message. invoke (partner. Link=“Buyer” port. Type=“SP: Buyer. PT” operation=“synch. Purchase. Resp” input. Variable=“PO” output. Variable=“invoice”> <correlations> <correlation set=“Purchase. Order” initiate=“yes” pattern=“out”/> (initiated in outbound msg) <correlation set=“Invoice. Resp” initiate=“yes” pattern=“in”/> (initiated in inbound msg, which contains both sets) </correlations> </invoke> 128

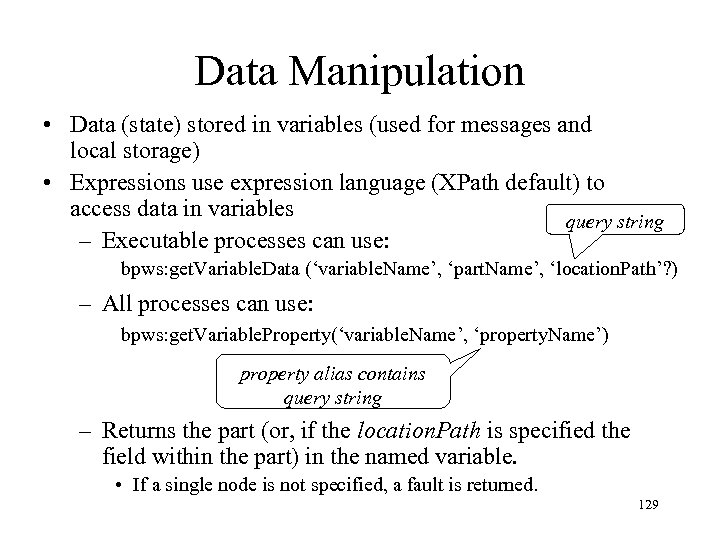

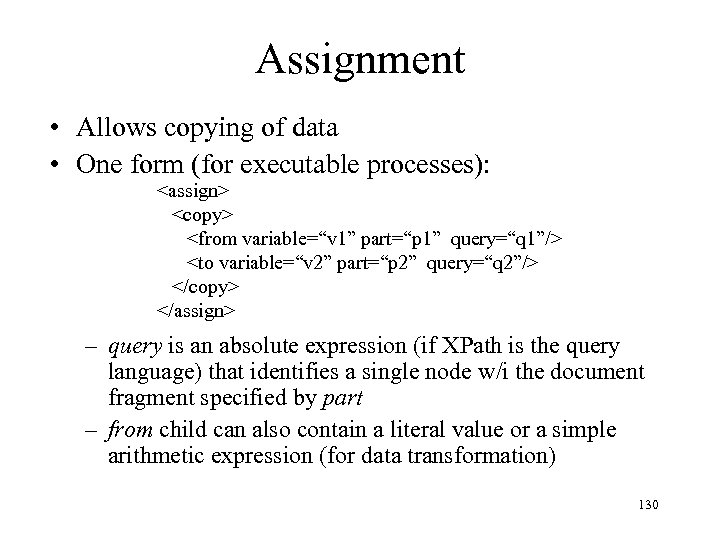

Data Manipulation • Data (state) stored in variables (used for messages and local storage) • Expressions use expression language (XPath default) to access data in variables query string – Executable processes can use: bpws: get. Variable. Data (‘variable. Name’, ‘part. Name’, ‘location. Path’? ) – All processes can use: bpws: get. Variable. Property(‘variable. Name’, ‘property. Name’) property alias contains query string – Returns the part (or, if the location. Path is specified the field within the part) in the named variable. • If a single node is not specified, a fault is returned. 129

Assignment • Allows copying of data • One form (for executable processes): <assign> <copy> <from variable=“v 1” part=“p 1” query=“q 1”/> <to variable=“v 2” part=“p 2” query=“q 2”/> </copy> </assign> – query is an absolute expression (if XPath is the query language) that identifies a single node w/i the document fragment specified by part – from child can also contain a literal value or a simple arithmetic expression (for data transformation) 130

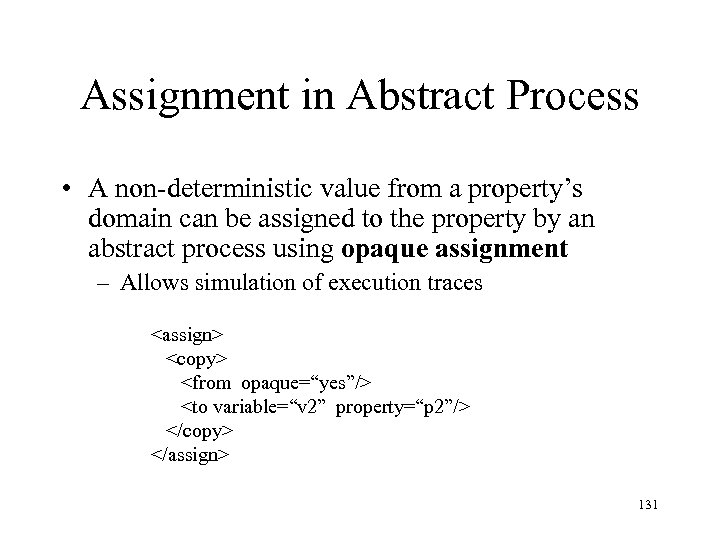

Assignment in Abstract Process • A non-deterministic value from a property’s domain can be assigned to the property by an abstract process using opaque assignment – Allows simulation of execution traces <assign> <copy> <from opaque=“yes”/> <to variable=“v 2” property=“p 2”/> </copy> </assign> 131

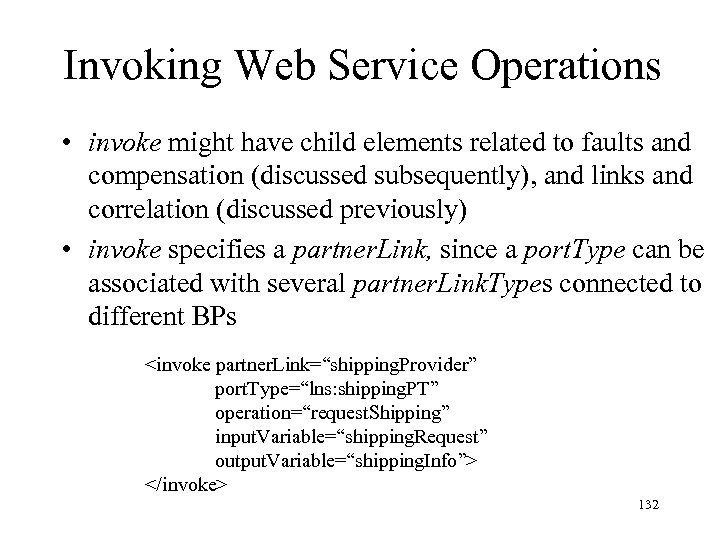

Invoking Web Service Operations • invoke might have child elements related to faults and compensation (discussed subsequently), and links and correlation (discussed previously) • invoke specifies a partner. Link, since a port. Type can be associated with several partner. Link. Types connected to different BPs <invoke partner. Link=“shipping. Provider” port. Type=“lns: shipping. PT” operation=“request. Shipping” input. Variable=“shipping. Request” output. Variable=“shipping. Info”> </invoke> 132

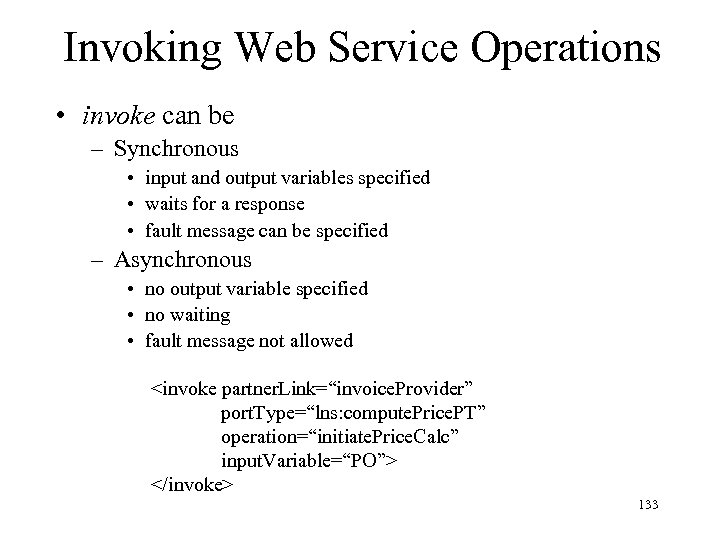

Invoking Web Service Operations • invoke can be – Synchronous • input and output variables specified • waits for a response • fault message can be specified – Asynchronous • no output variable specified • no waiting • fault message not allowed <invoke partner. Link=“invoice. Provider” port. Type=“lns: compute. Price. PT” operation=“initiate. Price. Calc” input. Variable=“PO”> </invoke> 133

Synchronous Vs. Asynchronous Invocation • Web service communication characterized by: – Services are not always available. – Loads tend to be unpredictable. • Attempts to handle too many requests in real time can lead to thrashing and failure. – Many requests can’t be handled instantly even with low loads. • Hence, asynchronous invocation will play an increasingly important role. 134

Providing Web Service Operations • receive waits for an invocation to arrive <receive partner. Link=“customer” port. Type=“lns: purch. Or. PT” operation=“send. Purch. Or” variable=“POmsg”/> </receive> – specifies a partner. Link, since a port. Type can be associated with several partner. Link. Types connected to different BPs 135

Providing Web Service Operations • Initiating a new instance of a BP: <receive partner. Link=“customer” port. Type=“lns: purch. Or. PT” operation=“send. Purch. Or” variable=“POmsg” create. Instance=“yes”> </receive> – create. Instance=“yes” => a new instance of the BP is created and this is its initial activity. • The receive should be the first activity in the BP (since prior activities will not be executed within the new instance) • If the message is the start of a conversation then a correlation child element should be specified: <correlation set=“Purchase. Order” initiation=“yes”/> 136

Providing Web Service Operations • reply is used to respond to a synchronous invocation. – connection between receive and reply based on constraint that not more than one synchronous request from a particular (partner. Link, port. Type, operation) can be outstanding at a time <reply partner. Link=“customer” port. Type=“lns: purch. Or. PT” operation=“send. Purch. Or” variable=“Invoice”/> • Response to an asynchronous invocation is made using an invoke on a callback operation – partner. Link between requestor and requestee must have two roles 137

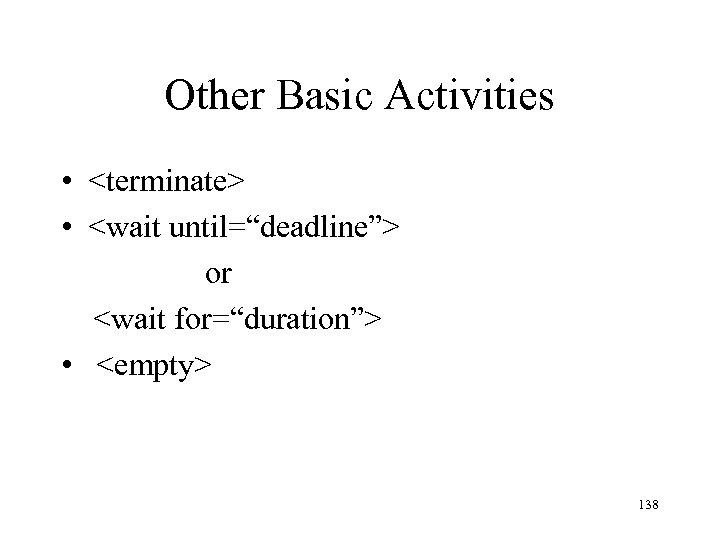

Other Basic Activities • <terminate> • <wait until=“deadline”> or <wait for=“duration”> • <empty> 138

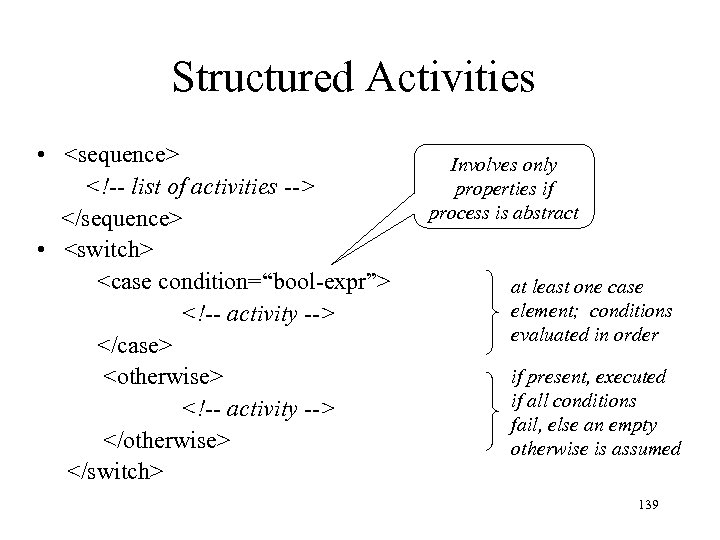

Structured Activities • <sequence> <!-- list of activities --> </sequence> • <switch> <case condition=“bool-expr”> <!-- activity --> </case> <otherwise> <!-- activity --> </otherwise> </switch> Involves only properties if process is abstract at least one case element; conditions evaluated in order if present, executed if all conditions fail, else an empty otherwise is assumed 139

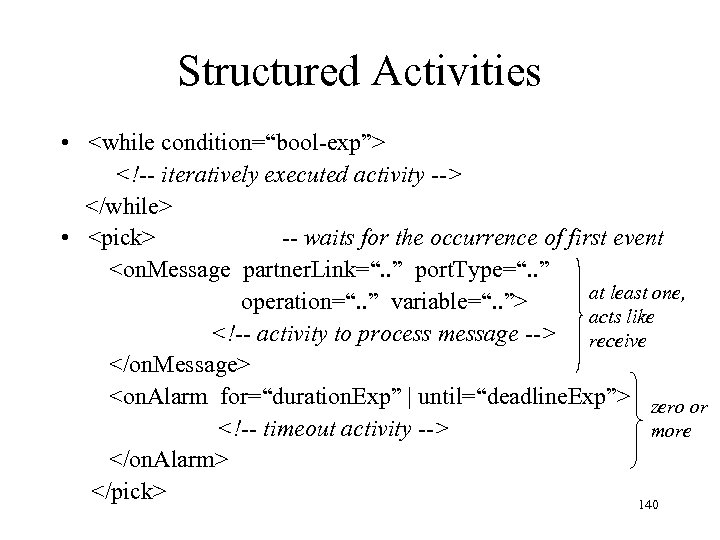

Structured Activities • <while condition=“bool-exp”> <!-- iteratively executed activity --> </while> • <pick> -- waits for the occurrence of first event <on. Message partner. Link=“. . ” port. Type=“. . ” at least one, operation=“. . ” variable=“. . ”> acts like <!-- activity to process message --> receive </on. Message> <on. Alarm for=“duration. Exp” | until=“deadline. Exp”> zero or <!-- timeout activity --> more </on. Alarm> </pick> 140

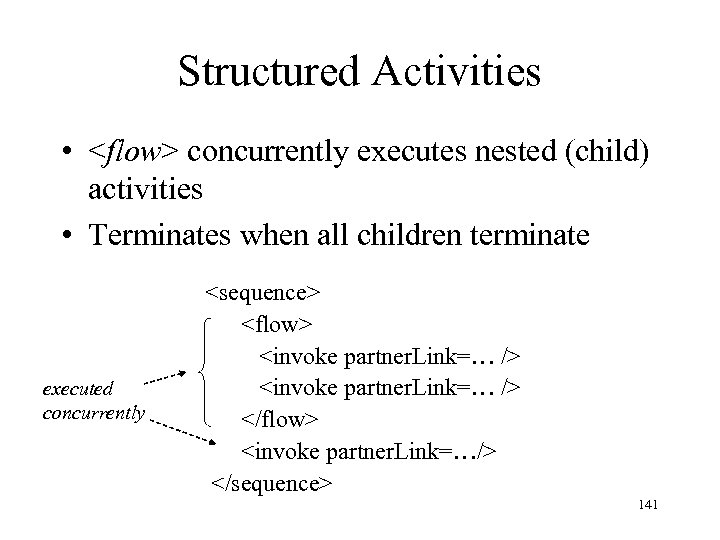

Structured Activities • <flow> concurrently executes nested (child) activities • Terminates when all children terminate executed concurrently <sequence> <flow> <invoke partner. Link=… /> </flow> <invoke partner. Link=…/> </sequence> 141

WSDL Review • WHAT: port. Type describes abstract functionality (operations, messages) • HOW: binding describes how elements of a port. Type (operations, messages) are mapped to a particular transport protocol (e. g. , SOAP over HTTP) • WHERE: port maps a binding to an address (particular server at a URL) – service is a collection of related ports 142

Endpoint References • A BP is statically dependent on the port. Types with which it communicates • However, the endpoint associated with a port. Type (and hence the identity of the BP instance with which it communicates) can change dynamically – Endpoints can be sent in messages • Hence, a BP can dynamically bind to another BP – Example: client can send a callback port. Type to which server can send response 143

Endpoint References • A message part can have type Endpoint. Reference. Type (as defined in WSAddressing) • Each role in a partner. Link has an associated Endpoint. Reference • An End. Point. Reference received in a message can be assigned to a partner link to dynamically establish a connection 144

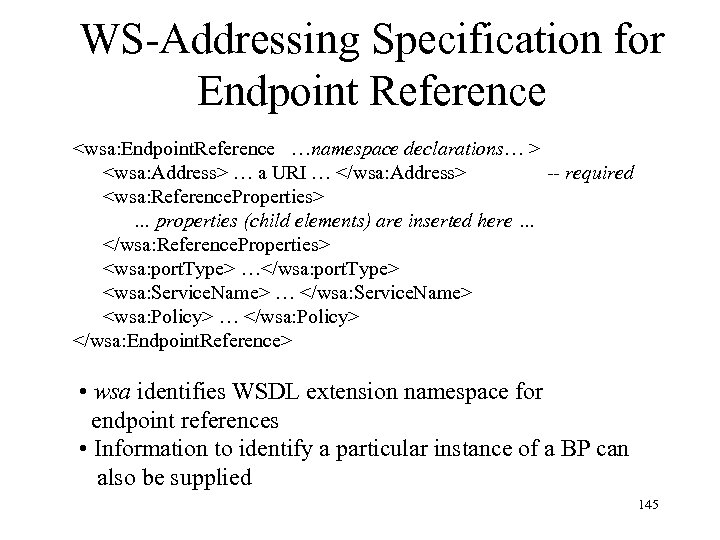

WS-Addressing Specification for Endpoint Reference <wsa: Endpoint. Reference …namespace declarations… > <wsa: Address> … a URI … </wsa: Address> -- required <wsa: Reference. Properties> … properties (child elements) are inserted here … </wsa: Reference. Properties> <wsa: port. Type> …</wsa: port. Type> <wsa: Service. Name> … </wsa: Service. Name> <wsa: Policy> … </wsa: Policy> </wsa: Endpoint. Reference> • wsa identifies WSDL extension namespace for endpoint references • Information to identify a particular instance of a BP can also be supplied 145

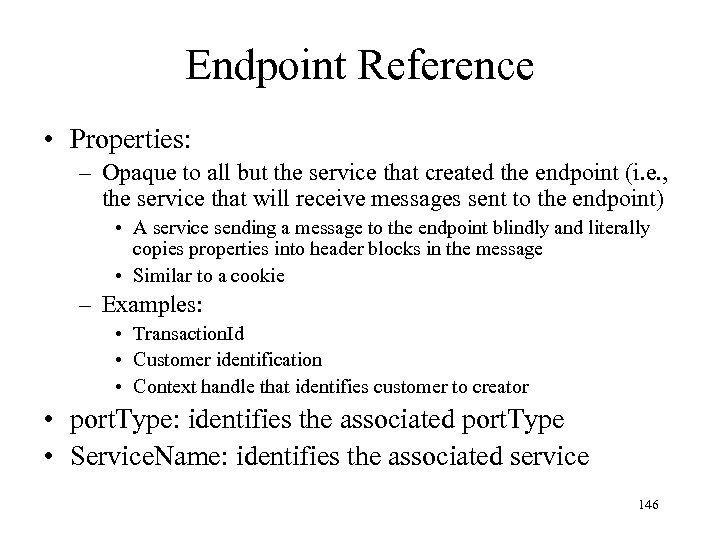

Endpoint Reference • Properties: – Opaque to all but the service that created the endpoint (i. e. , the service that will receive messages sent to the endpoint) • A service sending a message to the endpoint blindly and literally copies properties into header blocks in the message • Similar to a cookie – Examples: • Transaction. Id • Customer identification • Context handle that identifies customer to creator • port. Type: identifies the associated port. Type • Service. Name: identifies the associated service 146

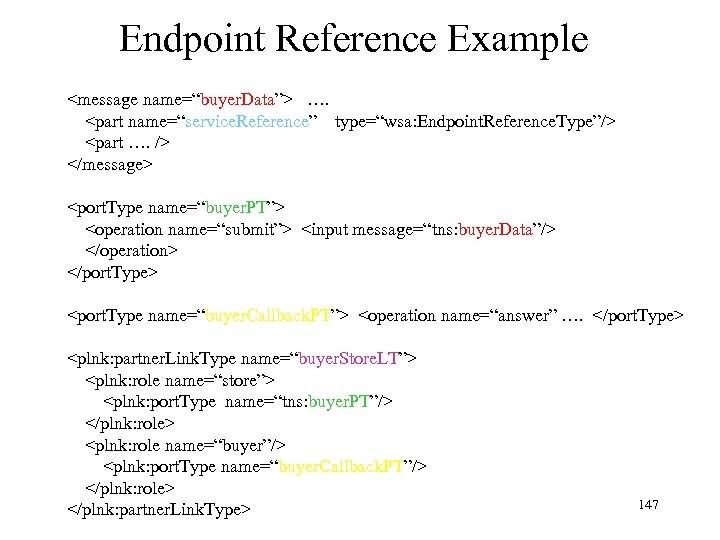

Endpoint Reference Example <message name=“buyer. Data”> …. <part name=“service. Reference” type=“wsa: Endpoint. Reference. Type”/> <part …. /> </message> <port. Type name=“buyer. PT”> <operation name=“submit”> <input message=“tns: buyer. Data”/> </operation> </port. Type> <port. Type name=“buyer. Callback. PT”> <operation name=“answer” …. </port. Type> <plnk: partner. Link. Type name=“buyer. Store. LT”> <plnk: role name=“store”> <plnk: port. Type name=“tns: buyer. PT”/> </plnk: role> <plnk: role name=“buyer”/> <plnk: port. Type name=“buyer. Callback. PT”/> </plnk: role> </plnk: partner. Link. Type> 147

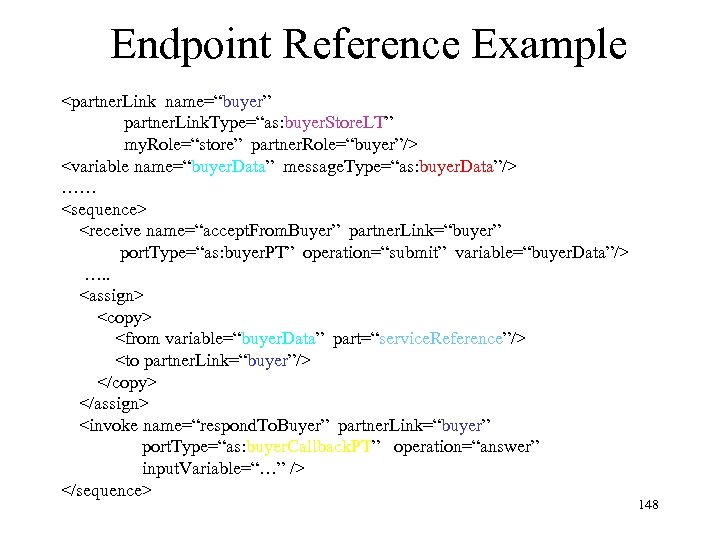

Endpoint Reference Example <partner. Link name=“buyer” partner. Link. Type=“as: buyer. Store. LT” my. Role=“store” partner. Role=“buyer”/> <variable name=“buyer. Data” message. Type=“as: buyer. Data”/> …… <sequence> <receive name=“accept. From. Buyer” partner. Link=“buyer” port. Type=“as: buyer. PT” operation=“submit” variable=“buyer. Data”/> …. . <assign> <copy> <from variable=“buyer. Data” part=“service. Reference”/> <to partner. Link=“buyer”/> </copy> </assign> <invoke name=“respond. To. Buyer” partner. Link=“buyer” port. Type=“as: buyer. Callback. PT” operation=“answer” input. Variable=“…” /> </sequence> 148

Endpoint Reference • Since the partner. Link, port. Type and operation are (statically) specified in the invoke statement, the exchange of an endpoint. Reference allows a BP to dynamically bind to a BP that supports that operation and port. Type (not to any BP) 149

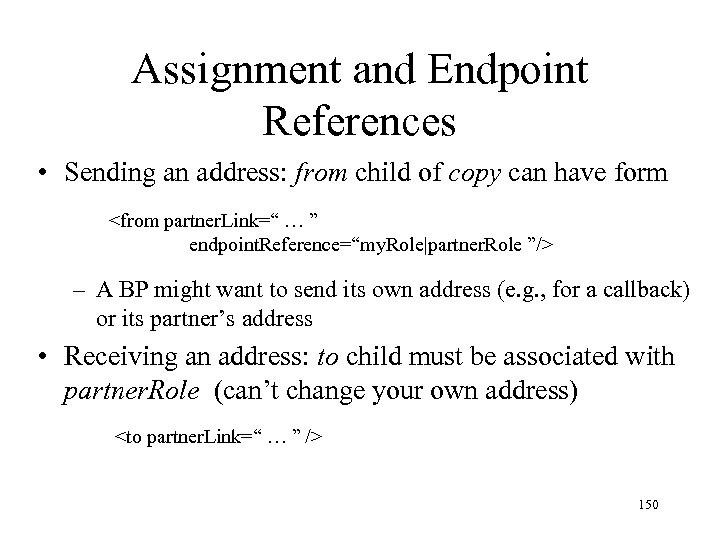

Assignment and Endpoint References • Sending an address: from child of copy can have form <from partner. Link=“ … ” endpoint. Reference=“my. Role|partner. Role ”/> – A BP might want to send its own address (e. g. , for a callback) or its partner’s address • Receiving an address: to child must be associated with partner. Role (can’t change your own address) <to partner. Link=“ … ” /> 150

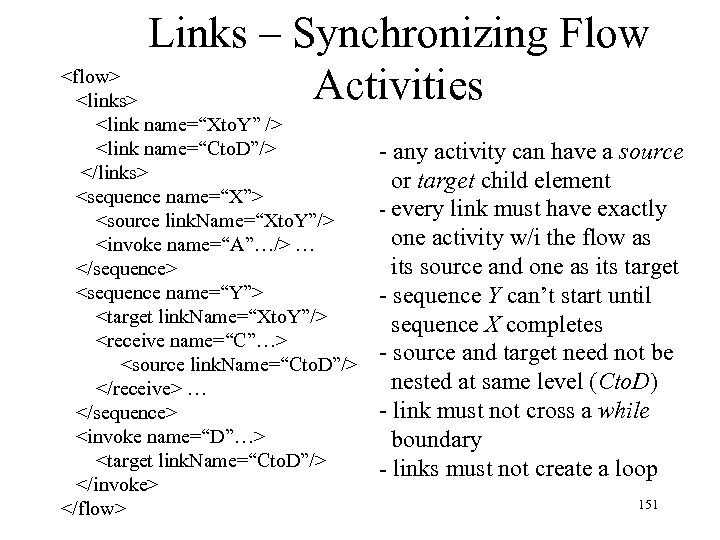

Links – Synchronizing Flow <flow> Activities <links> <link name=“Xto. Y” /> <link name=“Cto. D”/> </links> <sequence name=“X”> <source link. Name=“Xto. Y”/> <invoke name=“A”…/> … </sequence> <sequence name=“Y”> <target link. Name=“Xto. Y”/> <receive name=“C”…> <source link. Name=“Cto. D”/> </receive> … </sequence> <invoke name=“D”…> <target link. Name=“Cto. D”/> </invoke> </flow> - any activity can have a source or target child element - every link must have exactly one activity w/i the flow as its source and one as its target - sequence Y can’t start until sequence X completes - source and target need not be nested at same level (Cto. D) - link must not cross a while boundary - links must not create a loop 151

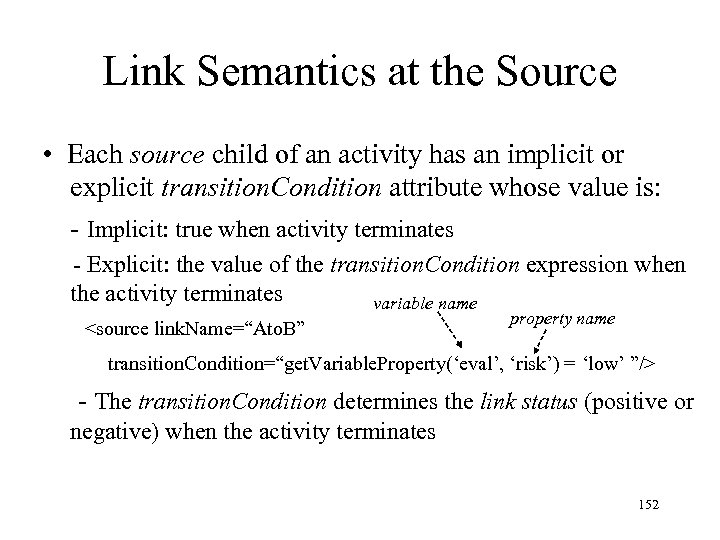

Link Semantics at the Source • Each source child of an activity has an implicit or explicit transition. Condition attribute whose value is: - Implicit: true when activity terminates - Explicit: the value of the transition. Condition expression when the activity terminates variable name <source link. Name=“Ato. B” property name transition. Condition=“get. Variable. Property(‘eval’, ‘risk’) = ‘low’ ”/> - The transition. Condition determines the link status (positive or negative) when the activity terminates 152

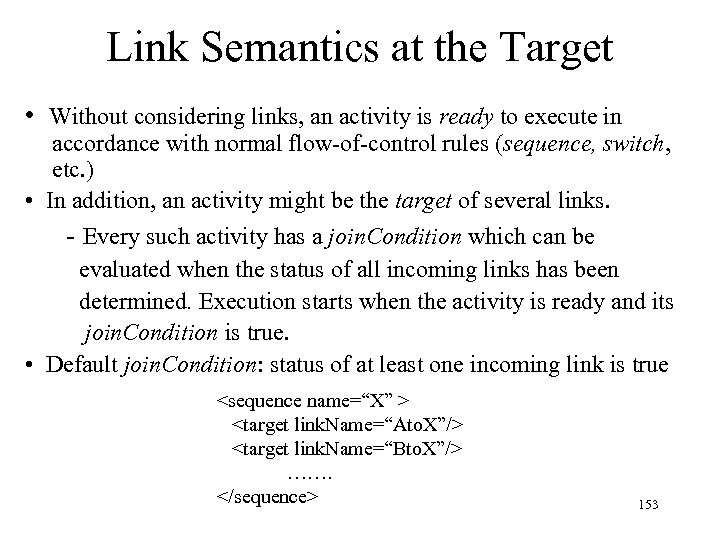

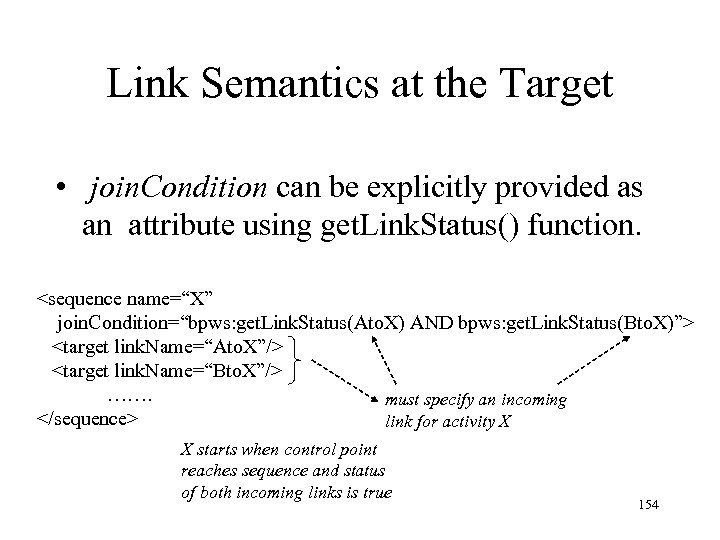

Link Semantics at the Target • Without considering links, an activity is ready to execute in accordance with normal flow-of-control rules (sequence, switch, etc. ) • In addition, an activity might be the target of several links. - Every such activity has a join. Condition which can be evaluated when the status of all incoming links has been determined. Execution starts when the activity is ready and its join. Condition is true. • Default join. Condition: status of at least one incoming link is true <sequence name=“X” > <target link. Name=“Ato. X”/> <target link. Name=“Bto. X”/> ……. </sequence> 153

Link Semantics at the Target • join. Condition can be explicitly provided as an attribute using get. Link. Status() function. <sequence name=“X” join. Condition=“bpws: get. Link. Status(Ato. X) AND bpws: get. Link. Status(Bto. X)”> <target link. Name=“Ato. X”/> <target link. Name=“Bto. X”/> ……. must specify an incoming </sequence> link for activity X X starts when control point reaches sequence and status of both incoming links is true 154

Link Semantics at the Target • If the join. Condition evaluates to false a join. Failure fault is thrown, else the activity is started • If an activity, X, will not be executed (e. g. a case in a switch, an activity that does not complete due to a fault) then the status of all outgoing links from X is set to negative. 155

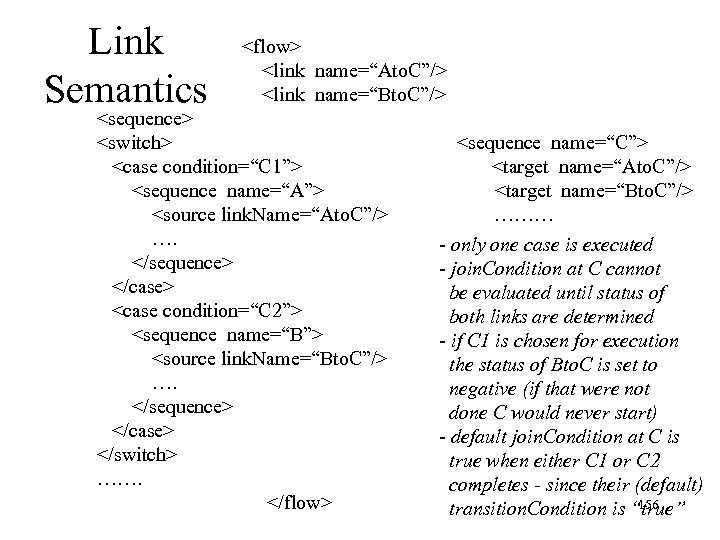

Link Semantics <flow> <link name=“Ato. C”/> <link name=“Bto. C”/> <sequence> <switch> <case condition=“C 1”> <sequence name=“A”> <source link. Name=“Ato. C”/> …. </sequence> </case> <case condition=“C 2”> <sequence name=“B”> <source link. Name=“Bto. C”/> …. </sequence> </case> </switch> ……. </flow> <sequence name=“C”> <target name=“Ato. C”/> <target name=“Bto. C”/> ……… - only one case is executed - join. Condition at C cannot be evaluated until status of both links are determined - if C 1 is chosen for execution the status of Bto. C is set to negative (if that were not done C would never start) - default join. Condition at C is true when either C 1 or C 2 completes - since their (default) 156 transition. Condition is “true”

Link Semantics • Problem – in some cases a false join. Condition is not a fault; it is an indication that the activity should not be performed in at a particular point in the execution – In that case the status of all outgoing links should be set to false so that the join. Condition of other activities can be evaluated • Solution – use activity attribute suppress. Join. Failure 157

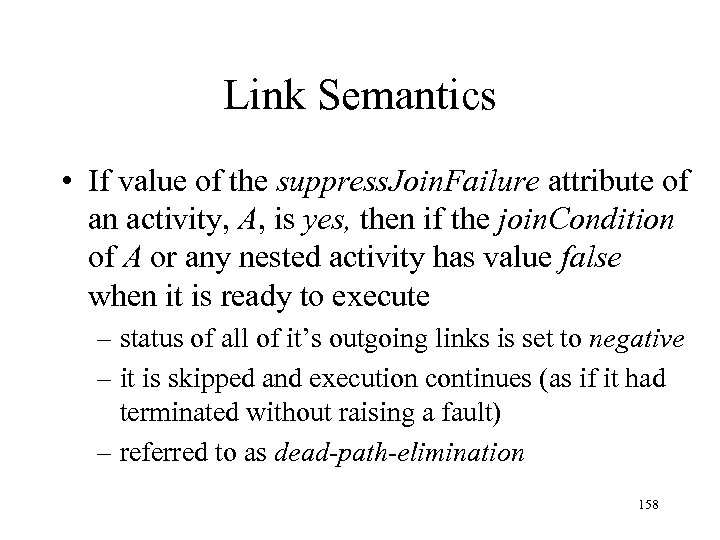

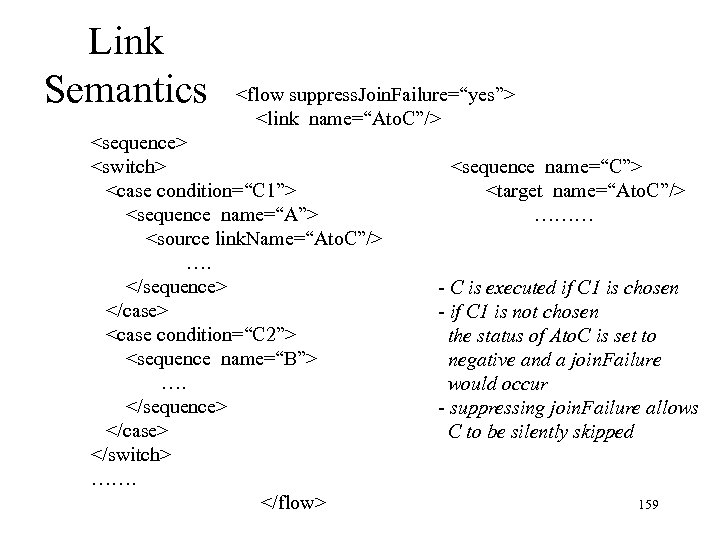

Link Semantics • If value of the suppress. Join. Failure attribute of an activity, A, is yes, then if the join. Condition of A or any nested activity has value false when it is ready to execute – status of all of it’s outgoing links is set to negative – it is skipped and execution continues (as if it had terminated without raising a fault) – referred to as dead-path-elimination 158

Link Semantics <flow suppress. Join. Failure=“yes”> <link name=“Ato. C”/> <sequence> <switch> <case condition=“C 1”> <sequence name=“A”> <source link. Name=“Ato. C”/> …. </sequence> </case> <case condition=“C 2”> <sequence name=“B”> …. </sequence> </case> </switch> ……. </flow> <sequence name=“C”> <target name=“Ato. C”/> ……… - C is executed if C 1 is chosen - if C 1 is not chosen the status of Ato. C is set to negative and a join. Failure would occur - suppressing join. Failure allows C to be silently skipped 159

Scope • Nested scoping is provided through the scope activity in the conventional way. • Variables, fault and compensation handlers, and correlation sets can be declared. • Properties are global since they are mapped to data in messages. 160

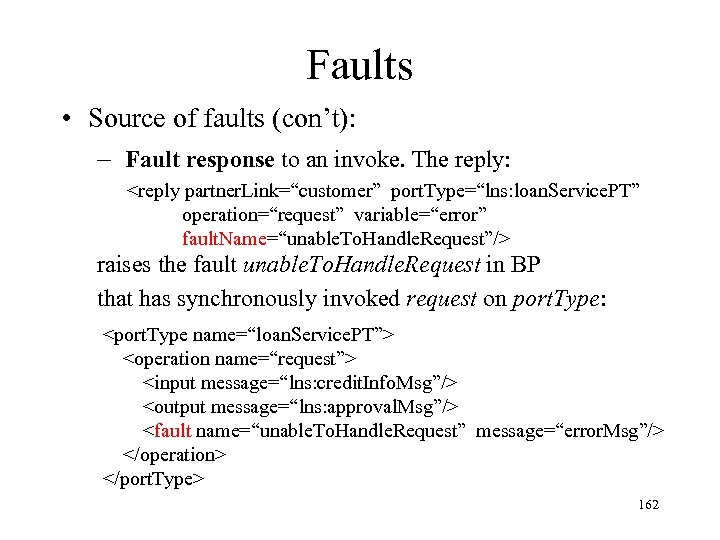

Faults • Fault has a unique name and an (optional) fault variable describing the event • Sources of faults: – Explicit raising of a fault <throw fault. Name=“trouble” fault. Variable=“descr”/> – Standard BPEL faults bpws: join. Failure - join. Condition has value false bpws: conflicting. Receive – two receive’s for same partner. Link, port. Type and operation pending within a flow at the same time 161

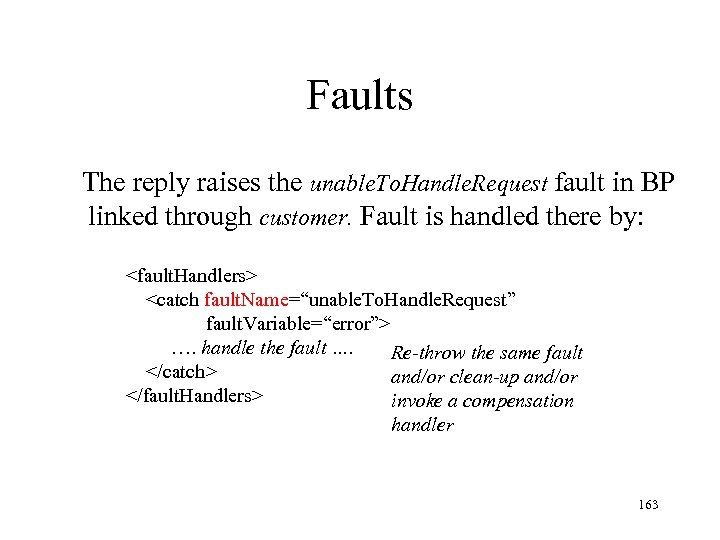

Faults • Source of faults (con’t): – Fault response to an invoke. The reply: <reply partner. Link=“customer” port. Type=“lns: loan. Service. PT” operation=“request” variable=“error” fault. Name=“unable. To. Handle. Request”/> raises the fault unable. To. Handle. Request in BP that has synchronously invoked request on port. Type: <port. Type name=“loan. Service. PT”> <operation name=“request”> <input message=“lns: credit. Info. Msg”/> <output message=“lns: approval. Msg”/> <fault name=“unable. To. Handle. Request” message=“error. Msg”/> </operation> </port. Type> 162

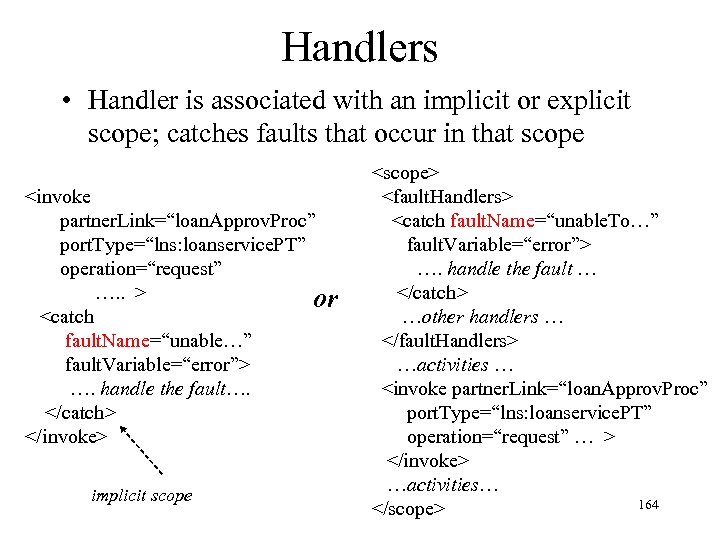

Faults The reply raises the unable. To. Handle. Request fault in BP linked through customer. Fault is handled there by: <fault. Handlers> <catch fault. Name=“unable. To. Handle. Request” fault. Variable=“error”> …. handle the fault …. Re-throw the same fault </catch> and/or clean-up and/or </fault. Handlers> invoke a compensation handler 163

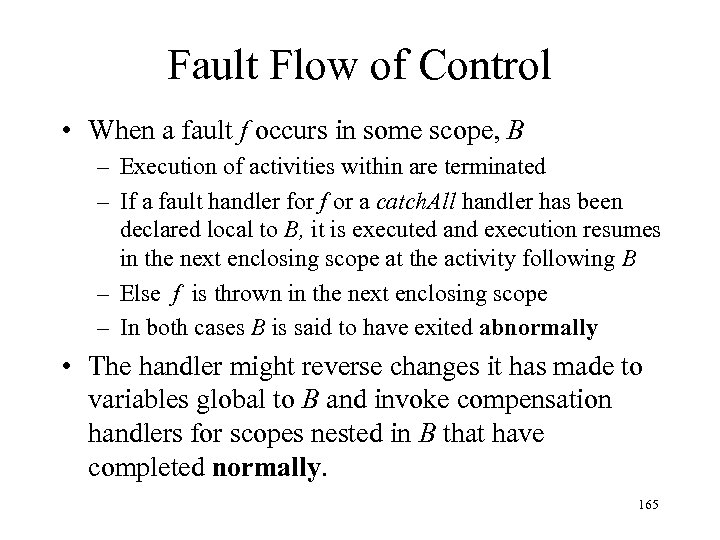

Handlers • Handler is associated with an implicit or explicit scope; catches faults that occur in that scope <invoke partner. Link=“loan. Approv. Proc” port. Type=“lns: loanservice. PT” operation=“request” …. . > or <catch fault. Name=“unable…” fault. Variable=“error”> …. handle the fault…. </catch> </invoke> implicit scope <scope> <fault. Handlers> <catch fault. Name=“unable. To…” fault. Variable=“error”> …. handle the fault … </catch> …other handlers … </fault. Handlers> …activities … <invoke partner. Link=“loan. Approv. Proc” port. Type=“lns: loanservice. PT” operation=“request” … > </invoke> …activities… 164 </scope>

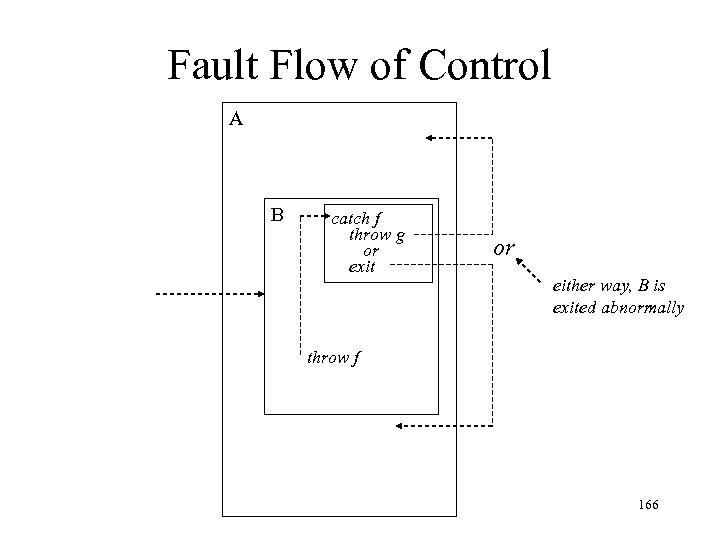

Fault Flow of Control • When a fault f occurs in some scope, B – Execution of activities within are terminated – If a fault handler for f or a catch. All handler has been declared local to B, it is executed and execution resumes in the next enclosing scope at the activity following B – Else f is thrown in the next enclosing scope – In both cases B is said to have exited abnormally • The handler might reverse changes it has made to variables global to B and invoke compensation handlers for scopes nested in B that have completed normally. 165

Fault Flow of Control A B catch f throw g or exit or either way, B is exited abnormally throw f 166

Atomicity • A BP is a long running process involving invocations of operations at a number of web services, S 1, S 2, …Sn. • It is unrealistic to treat a BP as a single transaction, since a particular service Si will not hold locks for the duration of the BP • Instead, an invocation at Si might be treated as a transaction that commits when it executes reply – BPEL does not support global atomicity (e. g. , twophase commit) over multiple invocations by a BP 167

Long-Running Business Transactions (LRT) • Reversing the effect of a BP relies on compensation – a web service might offer a compensating operation for a synchronous operation – Ex. Cancel. Purchase compensates for Purchase • BPEL supports an LRT by providing compensation handlers – Allows application to specify a recovery strategy using compensating operations – No guarantee of atomicity or isolation 168

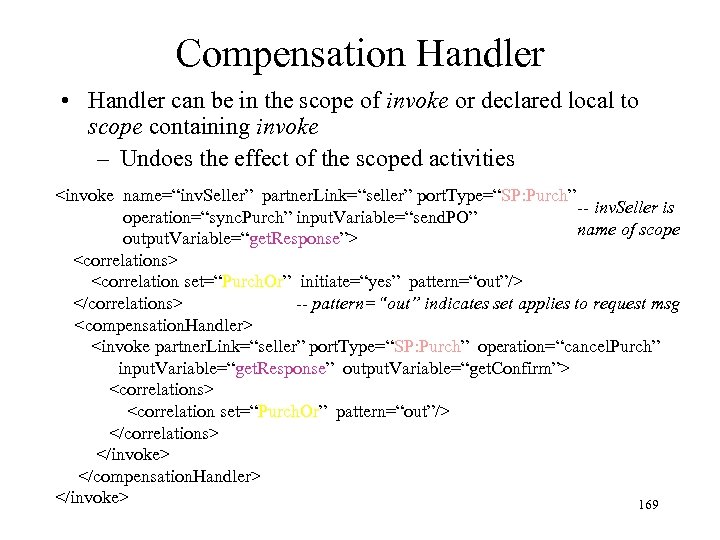

Compensation Handler • Handler can be in the scope of invoke or declared local to scope containing invoke – Undoes the effect of the scoped activities <invoke name=“inv. Seller” partner. Link=“seller” port. Type=“SP: Purch” -- inv. Seller is operation=“sync. Purch” input. Variable=“send. PO” name of scope output. Variable=“get. Response”> <correlations> <correlation set=“Purch. Or” initiate=“yes” pattern=“out”/> </correlations> -- pattern=“out” indicates set applies to request msg <compensation. Handler> <invoke partner. Link=“seller” port. Type=“SP: Purch” operation=“cancel. Purch” input. Variable=“get. Response” output. Variable=“get. Confirm”> <correlations> <correlation set=“Purch. Or” pattern=“out”/> </correlations> </invoke> </compensation. Handler> </invoke> 169

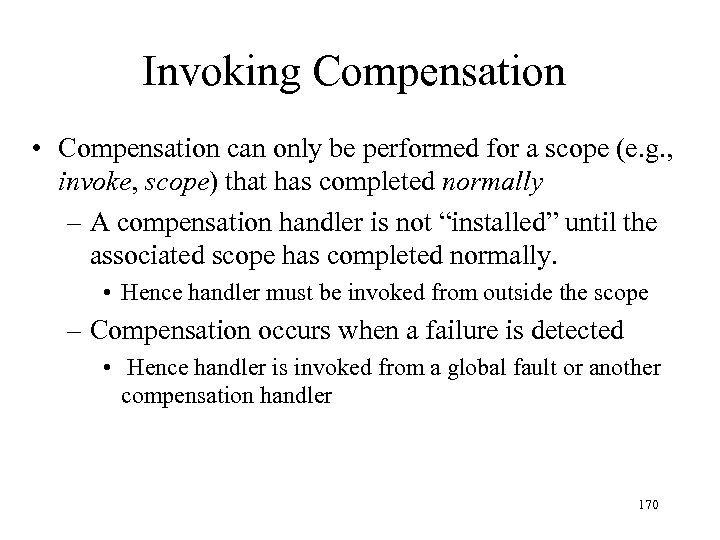

Invoking Compensation • Compensation can only be performed for a scope (e. g. , invoke, scope) that has completed normally – A compensation handler is not “installed” until the associated scope has completed normally. • Hence handler must be invoked from outside the scope – Compensation occurs when a failure is detected • Hence handler is invoked from a global fault or another compensation handler 170

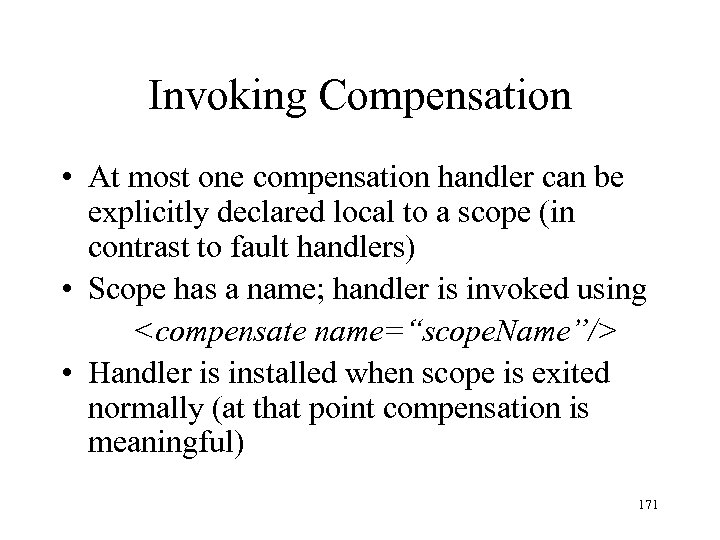

Invoking Compensation • At most one compensation handler can be explicitly declared local to a scope (in contrast to fault handlers) • Scope has a name; handler is invoked using <compensate name=“scope. Name”/> • Handler is installed when scope is exited normally (at that point compensation is meaningful) 171

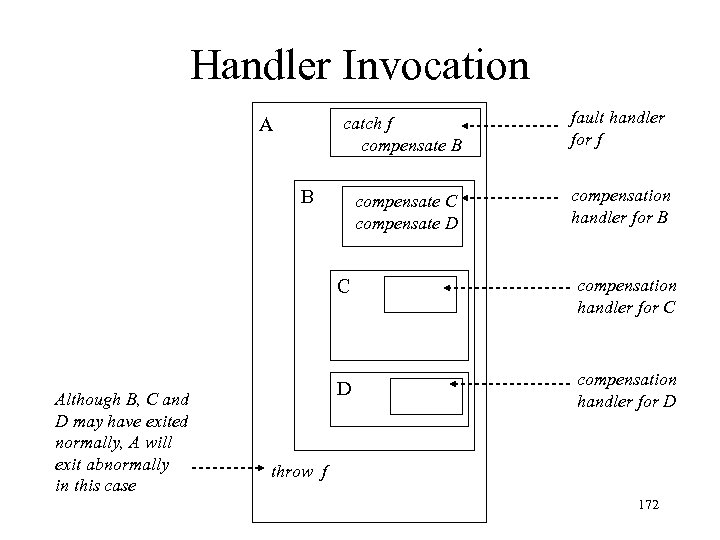

Handler Invocation catch f compensate B A fault handler for f compensate C compensate D compensation handler for B B C Although B, C and D may have exited normally, A will exit abnormally in this case compensation handler for C D compensation handler for D throw f 172

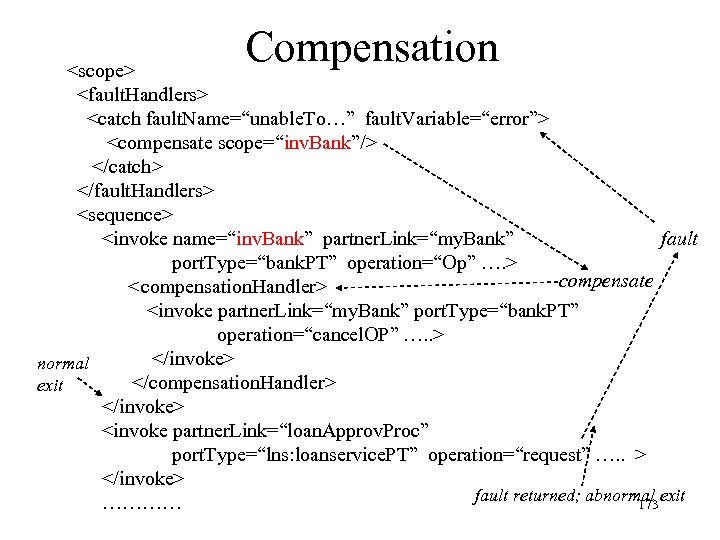

Compensation <scope> <fault. Handlers> <catch fault. Name=“unable. To…” fault. Variable=“error”> <compensate scope=“inv. Bank”/> </catch> </fault. Handlers> <sequence> <invoke name=“inv. Bank” partner. Link=“my. Bank” fault port. Type=“bank. PT” operation=“Op” …. > compensate <compensation. Handler> <invoke partner. Link=“my. Bank” port. Type=“bank. PT” operation=“cancel. OP” …. . > </invoke> normal </compensation. Handler> exit </invoke> <invoke partner. Link=“loan. Approv. Proc” port. Type=“lns: loanservice. PT” operation=“request” …. . > </invoke> fault returned; abnormal exit ………… 173

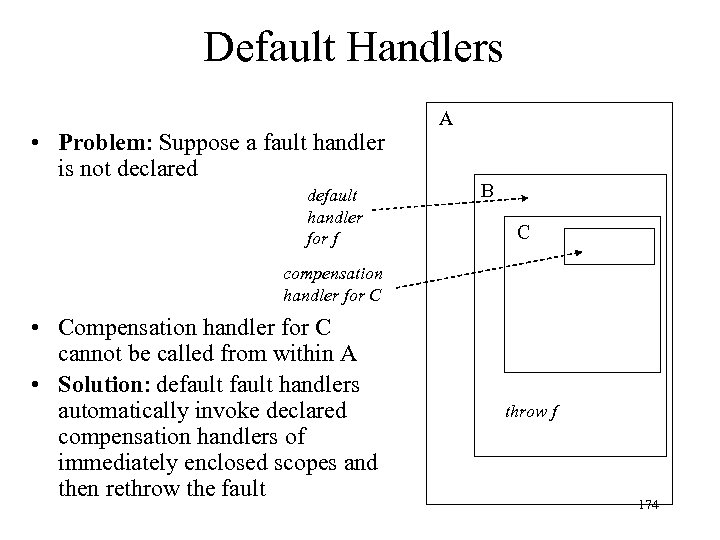

Default Handlers • Problem: Suppose a fault handler is not declared default handler for f A B C compensation handler for C • Compensation handler for C cannot be called from within A • Solution: default handlers automatically invoke declared compensation handlers of immediately enclosed scopes and then rethrow the fault throw f 174

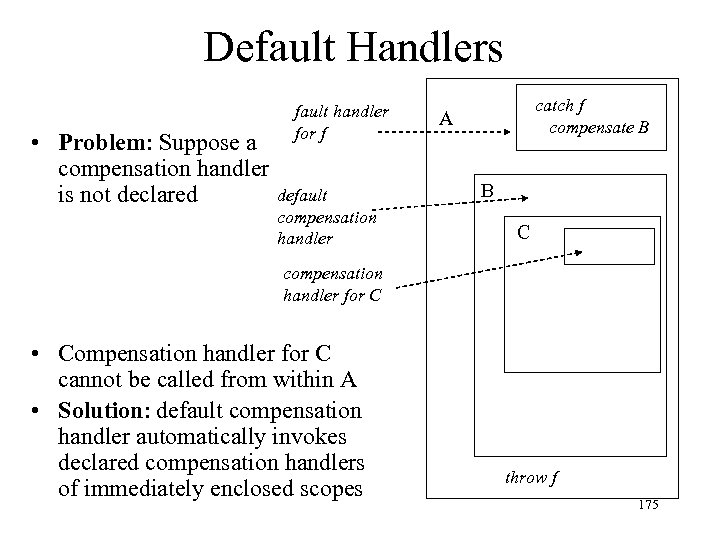

Default Handlers • Problem: Suppose a compensation handler is not declared fault handler for f default compensation handler catch f compensate B A B C compensation handler for C • Compensation handler for C cannot be called from within A • Solution: default compensation handler automatically invokes declared compensation handlers of immediately enclosed scopes throw f 175

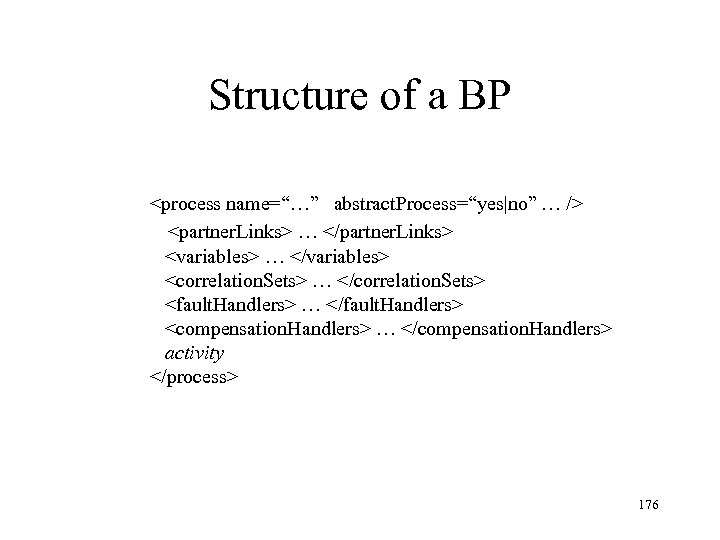

Structure of a BP <process name=“…” abstract. Process=“yes|no” … /> <partner. Links> … </partner. Links> <variables> … </variables> <correlation. Sets> … </correlation. Sets> <fault. Handlers> … </fault. Handlers> <compensation. Handlers> … </compensation. Handlers> activity </process> 176

61d1408c6dcae42a061f6c41ae47351a.ppt