685a46923cd9426f6d7f2c737d7263ea.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 29

Warning • I estimate 3 weeks of intensive reading for you to understand your assigned topic Ø These are not self contained and you will need to understand other topics first before we cover them inb class. • I estimate 4 -5 weeks before you have successfully installed the planning system and be able to run it in your domain

Warning • I estimate 3 weeks of intensive reading for you to understand your assigned topic Ø These are not self contained and you will need to understand other topics first before we cover them inb class. • I estimate 4 -5 weeks before you have successfully installed the planning system and be able to run it in your domain

Plan Representation in Classical Planning Sources: • Ch. 2 • Appendix B. 2 • Slides from Dana Nau’s lecture Dr. Héctor Muñoz-Avila

Plan Representation in Classical Planning Sources: • Ch. 2 • Appendix B. 2 • Slides from Dana Nau’s lecture Dr. Héctor Muñoz-Avila

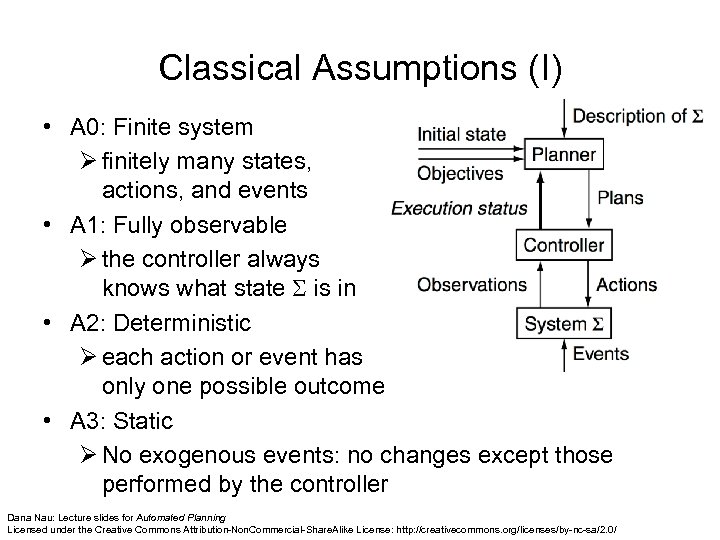

Classical Assumptions (I) • A 0: Finite system Ø finitely many states, actions, and events • A 1: Fully observable Ø the controller always knows what state is in • A 2: Deterministic Ø each action or event has only one possible outcome • A 3: Static Ø No exogenous events: no changes except those performed by the controller Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Classical Assumptions (I) • A 0: Finite system Ø finitely many states, actions, and events • A 1: Fully observable Ø the controller always knows what state is in • A 2: Deterministic Ø each action or event has only one possible outcome • A 3: Static Ø No exogenous events: no changes except those performed by the controller Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

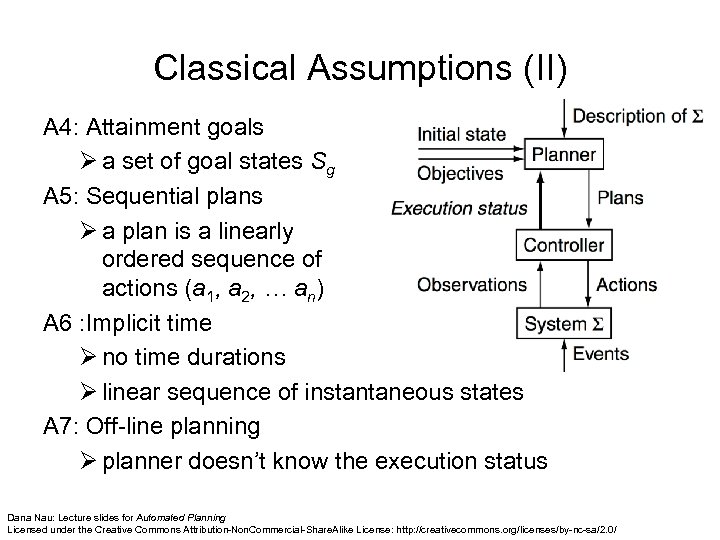

Classical Assumptions (II) A 4: Attainment goals Ø a set of goal states Sg A 5: Sequential plans Ø a plan is a linearly ordered sequence of actions (a 1, a 2, … an) A 6 : Implicit time Ø no time durations Ø linear sequence of instantaneous states A 7: Off-line planning Ø planner doesn’t know the execution status Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Classical Assumptions (II) A 4: Attainment goals Ø a set of goal states Sg A 5: Sequential plans Ø a plan is a linearly ordered sequence of actions (a 1, a 2, … an) A 6 : Implicit time Ø no time durations Ø linear sequence of instantaneous states A 7: Off-line planning Ø planner doesn’t know the execution status Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Ok So Why Even Study Classical Planning? • By restricting the complex processes we can study properties and limitations (e. g. , complexity) • Some classical planning techniques can be expanded to deal with more realistic situations Ø We will study these later • Surprisingly some classical planners have made it into actual deployed applications

Ok So Why Even Study Classical Planning? • By restricting the complex processes we can study properties and limitations (e. g. , complexity) • Some classical planning techniques can be expanded to deal with more realistic situations Ø We will study these later • Surprisingly some classical planners have made it into actual deployed applications

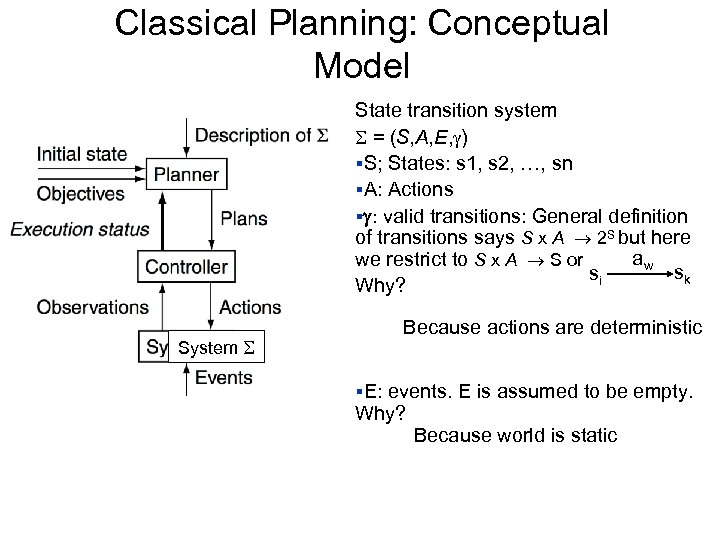

Classical Planning: Conceptual Model State transition system = (S, A, E, ) §S; States: s 1, s 2, …, sn §A: Actions § : valid transitions: General definition of transitions says S x A 2 S but here aw we restrict to S x A S or sk si Why? System Because actions are deterministic §E: events. E is assumed to be empty. Why? Because world is static

Classical Planning: Conceptual Model State transition system = (S, A, E, ) §S; States: s 1, s 2, …, sn §A: Actions § : valid transitions: General definition of transitions says S x A 2 S but here aw we restrict to S x A S or sk si Why? System Because actions are deterministic §E: events. E is assumed to be empty. Why? Because world is static

Three Representations • Set-Theoretic: Ø uses propositional logic • Classical representation: Ø uses predicate logic • State-variable representations Ø Represent states in terms of variables used

Three Representations • Set-Theoretic: Ø uses propositional logic • Classical representation: Ø uses predicate logic • State-variable representations Ø Represent states in terms of variables used

Propositional Logic Definition. A proposition over a set P is defined as follows: • any element in a set P is a proposition • If 1 and 2, are propositions then: Ø ( 1 2) are also propositions • If is a proposition then is a proposition Example: tired ¬hungry • Semantics defined in the usual way • Difference with predicate logic? • No variables • No quantifiers: , (Hai!)

Propositional Logic Definition. A proposition over a set P is defined as follows: • any element in a set P is a proposition • If 1 and 2, are propositions then: Ø ( 1 2) are also propositions • If is a proposition then is a proposition Example: tired ¬hungry • Semantics defined in the usual way • Difference with predicate logic? • No variables • No quantifiers: , (Hai!)

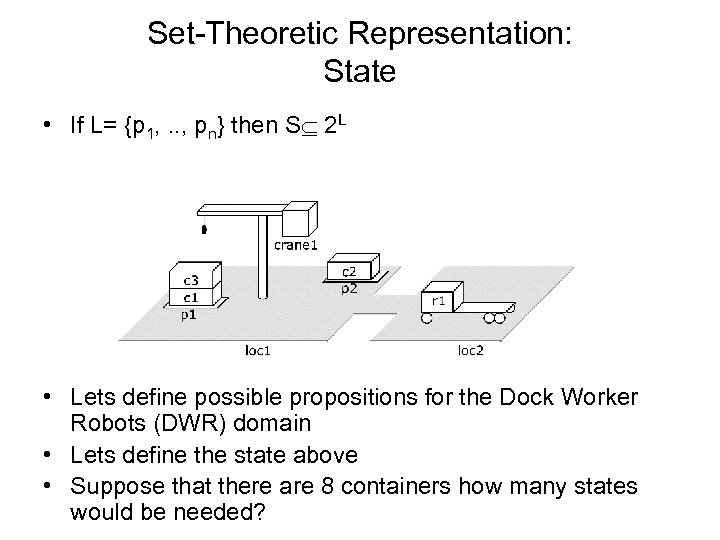

Set-Theoretic Representation: State • If L= {p 1, . . , pn} then S 2 L • Lets define possible propositions for the Dock Worker Robots (DWR) domain • Lets define the state above • Suppose that there are 8 containers how many states would be needed?

Set-Theoretic Representation: State • If L= {p 1, . . , pn} then S 2 L • Lets define possible propositions for the Dock Worker Robots (DWR) domain • Lets define the state above • Suppose that there are 8 containers how many states would be needed?

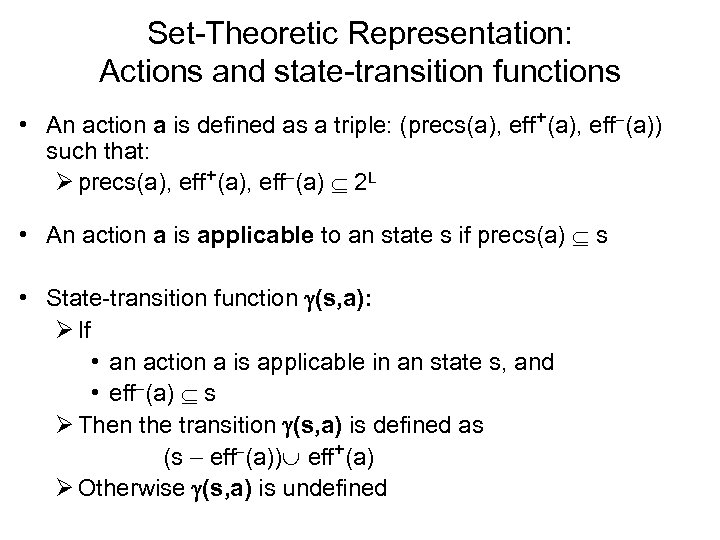

Set-Theoretic Representation: Actions and state-transition functions • An action a is defined as a triple: (precs(a), eff+(a), eff (a)) such that: Ø precs(a), eff+(a), eff (a) 2 L • An action a is applicable to an state s if precs(a) s • State-transition function (s, a): Ø If • an action a is applicable in an state s, and • eff (a) s Ø Then the transition (s, a) is defined as (s eff (a)) eff+(a) Ø Otherwise (s, a) is undefined

Set-Theoretic Representation: Actions and state-transition functions • An action a is defined as a triple: (precs(a), eff+(a), eff (a)) such that: Ø precs(a), eff+(a), eff (a) 2 L • An action a is applicable to an state s if precs(a) s • State-transition function (s, a): Ø If • an action a is applicable in an state s, and • eff (a) s Ø Then the transition (s, a) is defined as (s eff (a)) eff+(a) Ø Otherwise (s, a) is undefined

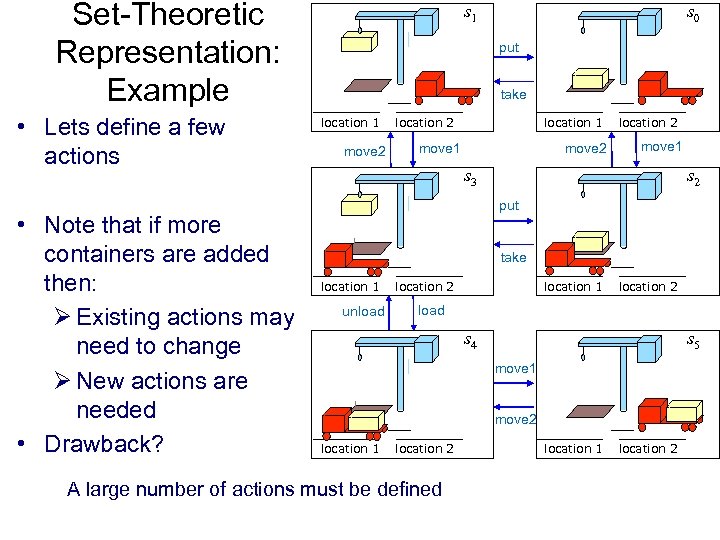

Set-Theoretic Representation: Example • Lets define a few actions • Note that if more containers are added then: Ø Existing actions may need to change Ø New actions are needed • Drawback? s 1 s 0 put take location 1 move 2 move 1 location 2 move 1 s 3 s 2 put take location 1 unload location 2 location 1 location 2 load s 4 s 5 move 1 move 2 location 1 location 2 A large number of actions must be defined location 1 location 2

Set-Theoretic Representation: Example • Lets define a few actions • Note that if more containers are added then: Ø Existing actions may need to change Ø New actions are needed • Drawback? s 1 s 0 put take location 1 move 2 move 1 location 2 move 1 s 3 s 2 put take location 1 unload location 2 location 1 location 2 load s 4 s 5 move 1 move 2 location 1 location 2 A large number of actions must be defined location 1 location 2

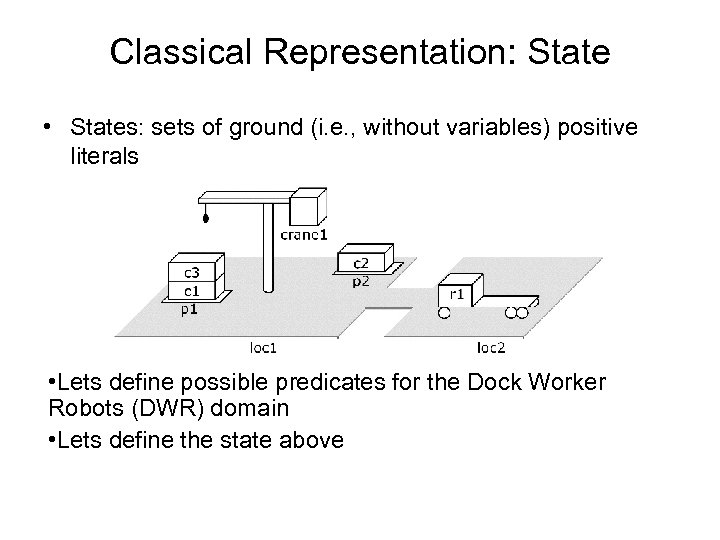

Classical Representation: State • States: sets of ground (i. e. , without variables) positive literals • Lets define possible predicates for the Dock Worker Robots (DWR) domain • Lets define the state above

Classical Representation: State • States: sets of ground (i. e. , without variables) positive literals • Lets define possible predicates for the Dock Worker Robots (DWR) domain • Lets define the state above

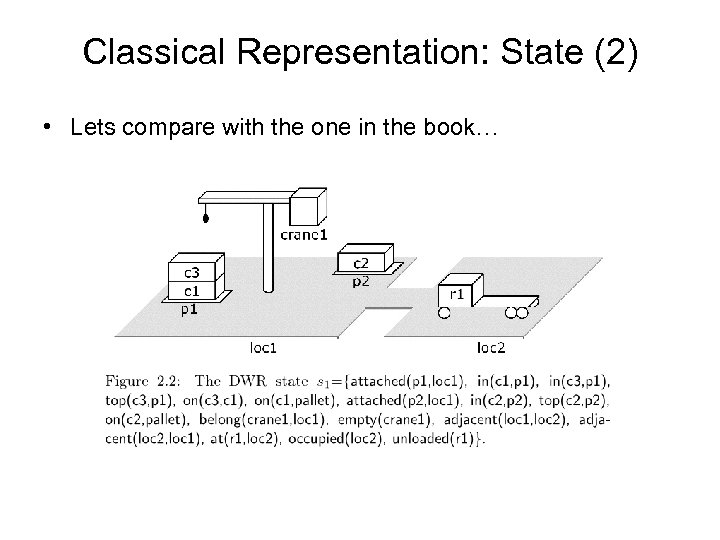

Classical Representation: State (2) • Lets compare with the one in the book…

Classical Representation: State (2) • Lets compare with the one in the book…

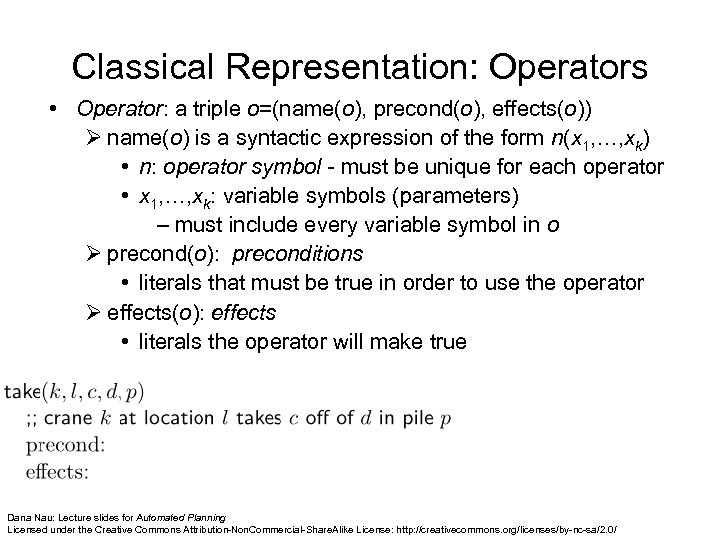

Classical Representation: Operators • Operator: a triple o=(name(o), precond(o), effects(o)) Ø name(o) is a syntactic expression of the form n(x 1, …, xk) • n: operator symbol - must be unique for each operator • x 1, …, xk: variable symbols (parameters) – must include every variable symbol in o Ø precond(o): preconditions • literals that must be true in order to use the operator Ø effects(o): effects • literals the operator will make true Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Classical Representation: Operators • Operator: a triple o=(name(o), precond(o), effects(o)) Ø name(o) is a syntactic expression of the form n(x 1, …, xk) • n: operator symbol - must be unique for each operator • x 1, …, xk: variable symbols (parameters) – must include every variable symbol in o Ø precond(o): preconditions • literals that must be true in order to use the operator Ø effects(o): effects • literals the operator will make true Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

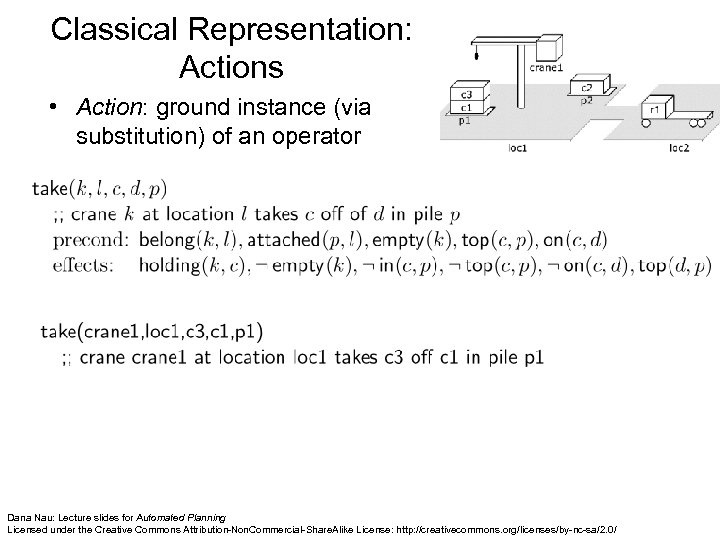

Classical Representation: Actions • Action: ground instance (via substitution) of an operator Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Classical Representation: Actions • Action: ground instance (via substitution) of an operator Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

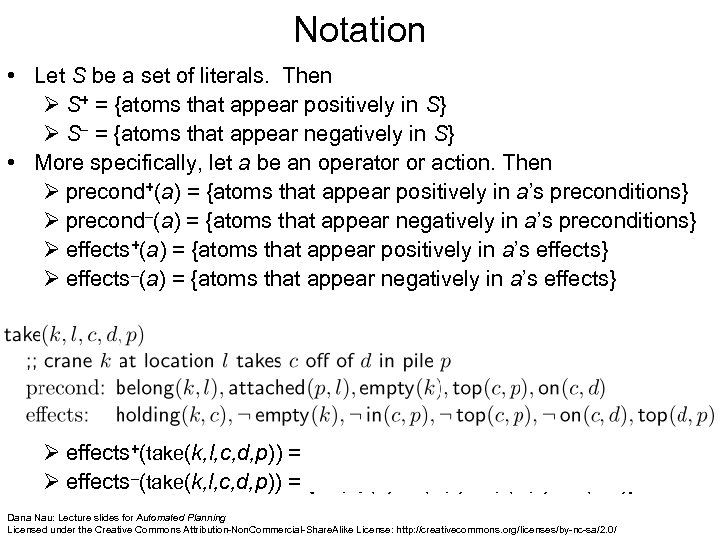

Notation • Let S be a set of literals. Then Ø S+ = {atoms that appear positively in S} Ø S– = {atoms that appear negatively in S} • More specifically, let a be an operator or action. Then Ø precond+(a) = {atoms that appear positively in a’s preconditions} Ø precond–(a) = {atoms that appear negatively in a’s preconditions} Ø effects+(a) = {atoms that appear positively in a’s effects} Ø effects–(a) = {atoms that appear negatively in a’s effects} Ø effects+(take(k, l, c, d, p)) = {holding(k, c), top(d, p)} Ø effects–(take(k, l, c, d, p)) = {empty(k), in(c, p), top(c, p), on(c, d)} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Notation • Let S be a set of literals. Then Ø S+ = {atoms that appear positively in S} Ø S– = {atoms that appear negatively in S} • More specifically, let a be an operator or action. Then Ø precond+(a) = {atoms that appear positively in a’s preconditions} Ø precond–(a) = {atoms that appear negatively in a’s preconditions} Ø effects+(a) = {atoms that appear positively in a’s effects} Ø effects–(a) = {atoms that appear negatively in a’s effects} Ø effects+(take(k, l, c, d, p)) = {holding(k, c), top(d, p)} Ø effects–(take(k, l, c, d, p)) = {empty(k), in(c, p), top(c, p), on(c, d)} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

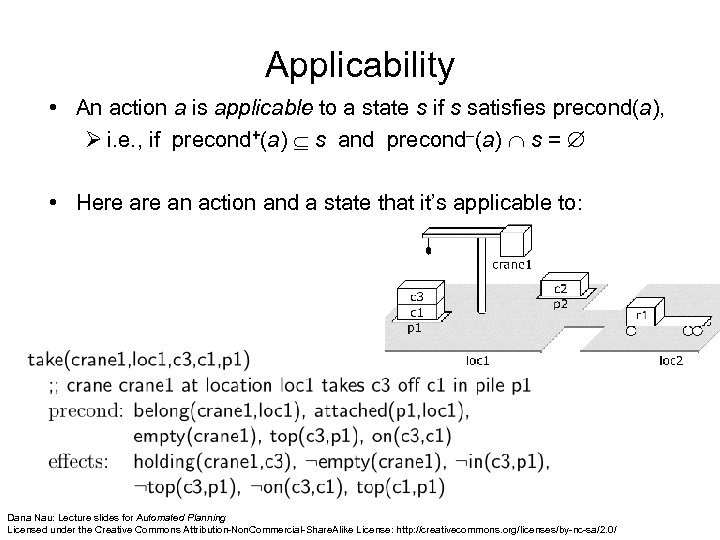

Applicability • An action a is applicable to a state s if s satisfies precond(a), Ø i. e. , if precond+(a) s and precond–(a) s = • Here an action and a state that it’s applicable to: Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Applicability • An action a is applicable to a state s if s satisfies precond(a), Ø i. e. , if precond+(a) s and precond–(a) s = • Here an action and a state that it’s applicable to: Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

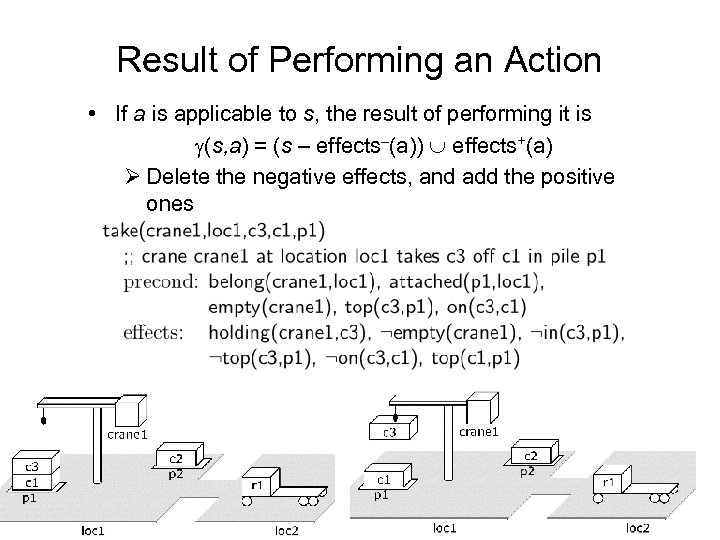

Result of Performing an Action • If a is applicable to s, the result of performing it is (s, a) = (s – effects–(a)) effects+(a) Ø Delete the negative effects, and add the positive ones

Result of Performing an Action • If a is applicable to s, the result of performing it is (s, a) = (s – effects–(a)) effects+(a) Ø Delete the negative effects, and add the positive ones

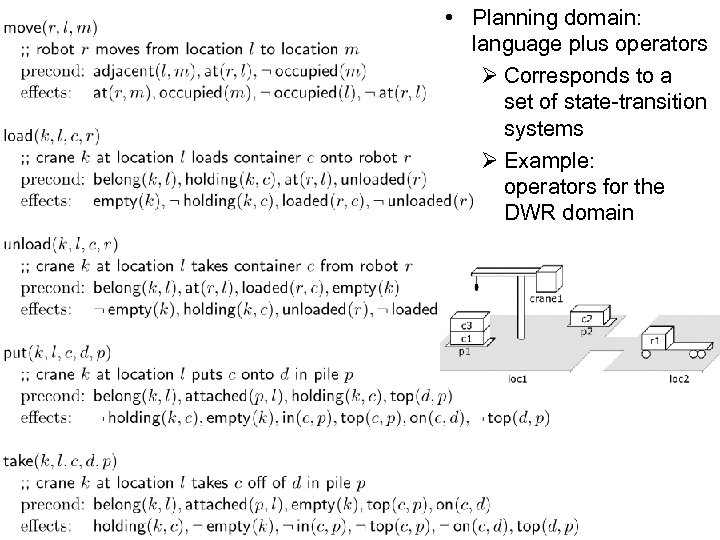

• Planning domain: language plus operators Ø Corresponds to a set of state-transition systems Ø Example: operators for the DWR domain

• Planning domain: language plus operators Ø Corresponds to a set of state-transition systems Ø Example: operators for the DWR domain

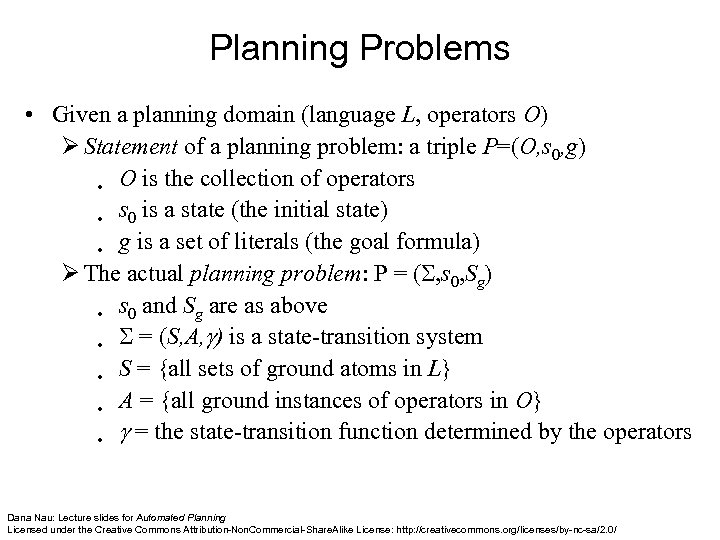

Planning Problems • Given a planning domain (language L, operators O) Ø Statement of a planning problem: a triple P=(O, s 0, g) • O is the collection of operators • s 0 is a state (the initial state) • g is a set of literals (the goal formula) Ø The actual planning problem: P = ( , s 0, Sg) • s 0 and Sg are as above • = (S, A, ) is a state-transition system • S = {all sets of ground atoms in L} • A = {all ground instances of operators in O} • = the state-transition function determined by the operators Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Planning Problems • Given a planning domain (language L, operators O) Ø Statement of a planning problem: a triple P=(O, s 0, g) • O is the collection of operators • s 0 is a state (the initial state) • g is a set of literals (the goal formula) Ø The actual planning problem: P = ( , s 0, Sg) • s 0 and Sg are as above • = (S, A, ) is a state-transition system • S = {all sets of ground atoms in L} • A = {all ground instances of operators in O} • = the state-transition function determined by the operators Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

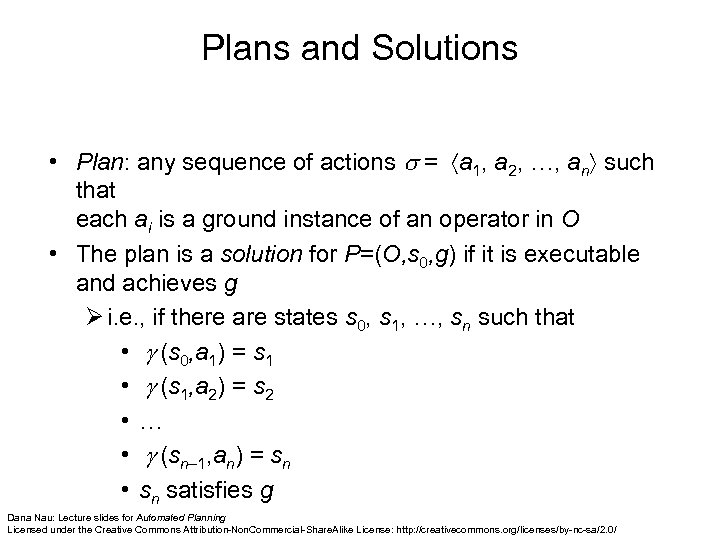

Plans and Solutions • Plan: any sequence of actions = a 1, a 2, …, an such that each ai is a ground instance of an operator in O • The plan is a solution for P=(O, s 0, g) if it is executable and achieves g Ø i. e. , if there are states s 0, s 1, …, sn such that • (s 0, a 1) = s 1 • (s 1, a 2) = s 2 • … • (sn– 1, an) = sn • sn satisfies g Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Plans and Solutions • Plan: any sequence of actions = a 1, a 2, …, an such that each ai is a ground instance of an operator in O • The plan is a solution for P=(O, s 0, g) if it is executable and achieves g Ø i. e. , if there are states s 0, s 1, …, sn such that • (s 0, a 1) = s 1 • (s 1, a 2) = s 2 • … • (sn– 1, an) = sn • sn satisfies g Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

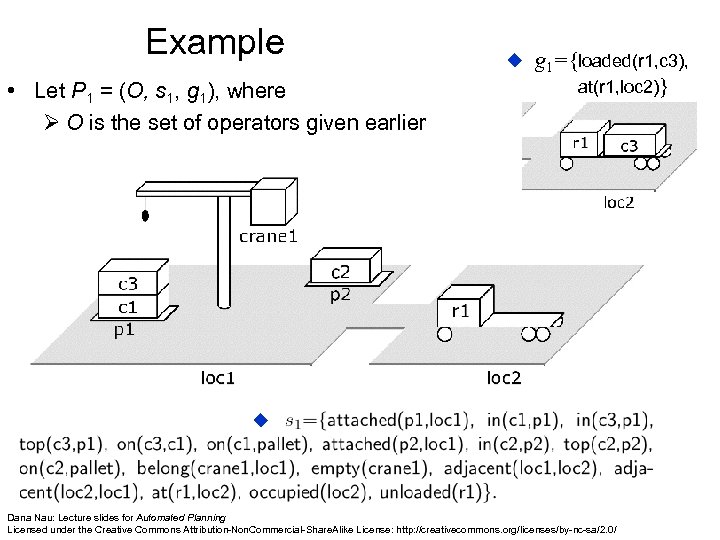

Example • Let P 1 = (O, s 1, g 1), where Ø O is the set of operators given earlier g 1={loaded(r 1, c 3), at(r 1, loc 2)} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Example • Let P 1 = (O, s 1, g 1), where Ø O is the set of operators given earlier g 1={loaded(r 1, c 3), at(r 1, loc 2)} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Example (continued) • Here are three solutions for P 1: Ø take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), move(r 1, loc 2), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) Ø take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) Ø move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) • Each of them produces the state shown here: Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Example (continued) • Here are three solutions for P 1: Ø take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), move(r 1, loc 2), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) Ø take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) Ø move(r 1, loc 2, loc 1), take(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, c 1, p 1), load(crane 1, loc 1, c 3, r 1), move(r 1, loc 2) • Each of them produces the state shown here: Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Comparison: Classical versus Set. Theoretical Representations • A set-theoretic representation is equivalent to a classical representation in which all of the atoms are ground • From classical to set-theoretical: Exponential blowup? Ø If a classical operator contains n atoms and each atom has arity k, then it corresponds to cnk actions where c = |{constant symbols}| Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Comparison: Classical versus Set. Theoretical Representations • A set-theoretic representation is equivalent to a classical representation in which all of the atoms are ground • From classical to set-theoretical: Exponential blowup? Ø If a classical operator contains n atoms and each atom has arity k, then it corresponds to cnk actions where c = |{constant symbols}| Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Extensions to Classical Representation • Conditional effects • Quantified expressions • Disjunctive preconditions • Axioms • Extended goals

Extensions to Classical Representation • Conditional effects • Quantified expressions • Disjunctive preconditions • Axioms • Extended goals

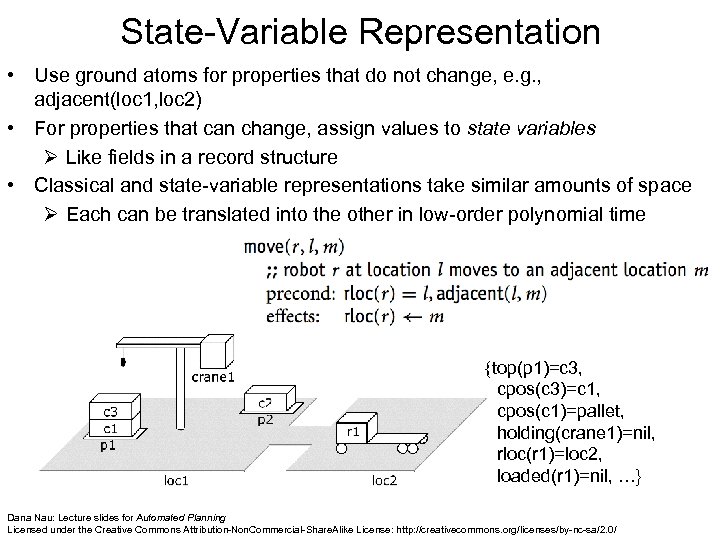

State-Variable Representation • Use ground atoms for properties that do not change, e. g. , adjacent(loc 1, loc 2) • For properties that can change, assign values to state variables Ø Like fields in a record structure • Classical and state-variable representations take similar amounts of space Ø Each can be translated into the other in low-order polynomial time {top(p 1)=c 3, cpos(c 3)=c 1, cpos(c 1)=pallet, holding(crane 1)=nil, rloc(r 1)=loc 2, loaded(r 1)=nil, …} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

State-Variable Representation • Use ground atoms for properties that do not change, e. g. , adjacent(loc 1, loc 2) • For properties that can change, assign values to state variables Ø Like fields in a record structure • Classical and state-variable representations take similar amounts of space Ø Each can be translated into the other in low-order polynomial time {top(p 1)=c 3, cpos(c 3)=c 1, cpos(c 1)=pallet, holding(crane 1)=nil, rloc(r 1)=loc 2, loaded(r 1)=nil, …} Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

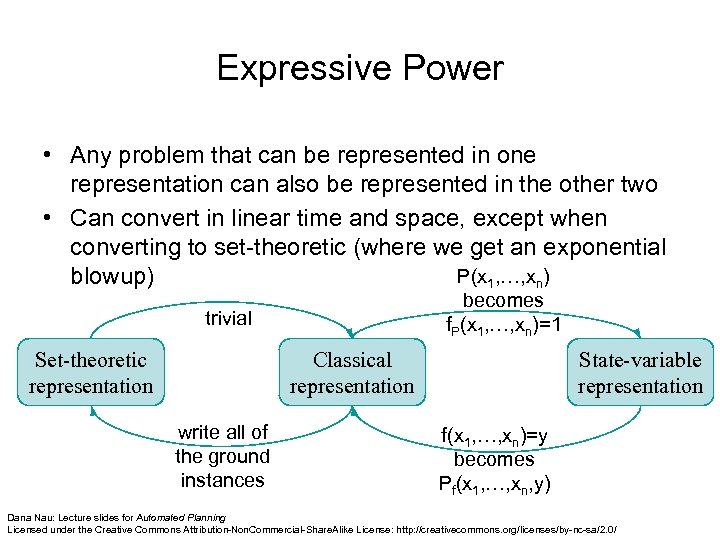

Expressive Power • Any problem that can be represented in one representation can also be represented in the other two • Can convert in linear time and space, except when converting to set-theoretic (where we get an exponential P(x 1, …, xn) blowup) becomes f. P(x 1, …, xn)=1 trivial Set-theoretic representation Classical representation write all of the ground instances State-variable representation f(x 1, …, xn)=y becomes Pf(x 1, …, xn, y) Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Expressive Power • Any problem that can be represented in one representation can also be represented in the other two • Can convert in linear time and space, except when converting to set-theoretic (where we get an exponential P(x 1, …, xn) blowup) becomes f. P(x 1, …, xn)=1 trivial Set-theoretic representation Classical representation write all of the ground instances State-variable representation f(x 1, …, xn)=y becomes Pf(x 1, …, xn, y) Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Comparison • Classical representation Ø The most popular for classical planning, partly for historical reasons • Set-theoretic representation Ø Can take much more space than classical representation Ø Useful in algorithms that manipulate ground atoms directly • e. g. , planning graphs (Chapter 6), satisfiability (Chapters 7) Ø Useful for certain kinds of theoretical studies • State-variable representation Ø Equivalent to classical representation Ø Less natural for logicians, more natural for engineers Ø Useful in non-classical planning problems as a way to handle numbers, functions, time Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

Comparison • Classical representation Ø The most popular for classical planning, partly for historical reasons • Set-theoretic representation Ø Can take much more space than classical representation Ø Useful in algorithms that manipulate ground atoms directly • e. g. , planning graphs (Chapter 6), satisfiability (Chapters 7) Ø Useful for certain kinds of theoretical studies • State-variable representation Ø Equivalent to classical representation Ø Less natural for logicians, more natural for engineers Ø Useful in non-classical planning problems as a way to handle numbers, functions, time Dana Nau: Lecture slides for Automated Planning Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non. Commercial-Share. Alike License: http: //creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2. 0/

“Hidden” Issues • Closed World Assumption Ø Ground literals not in the state are assumed to be false • Unification: Ø When unifying two atoms there is a unique Most General Unifier (sans variable names) Ø But: when matching sets of atoms (e. g. , operator preconditions versus state) multiple different Most General Unifiers may exist • This increases branching factor of search space

“Hidden” Issues • Closed World Assumption Ø Ground literals not in the state are assumed to be false • Unification: Ø When unifying two atoms there is a unique Most General Unifier (sans variable names) Ø But: when matching sets of atoms (e. g. , operator preconditions versus state) multiple different Most General Unifiers may exist • This increases branching factor of search space