c71ceca523139b2ed5ec973d64c98332.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 10

W. E. B. Du Bois William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was born in 1868, the year that Congress passed the 14 th amendment to the Constitution, recognizing all person born within the United States as citizens. Du Bois took the amendment at face value; however, even in New England, there were signs that African. Americans were not as equal as whites. After college a Fisk University in Nashville and Harvard, Du Bois gained a scholarship to study in Berlin. Back in American, he became the first African American to earn a Ph. D. at Harvard. In 1899, Du Bois published the first sociological study of African-Americans, The Philadelphia Negro. But his most famous work was The Souls of Black Folk (1903), in which he famously argued against Booker T. Washington’s accommodation with white Southerners. Du Bois was an intellectual warrior all his life. While he published several other scholarly books, he made his mark in American history by being a primary force in the founding of the N. A. A. C. P. and editing the magazine of the organization, The Crisis. W. E. B. Dubois, 1918; portrait by Cornelius M. Battey. Library of Congress image. Source: commons. wikimedia. org

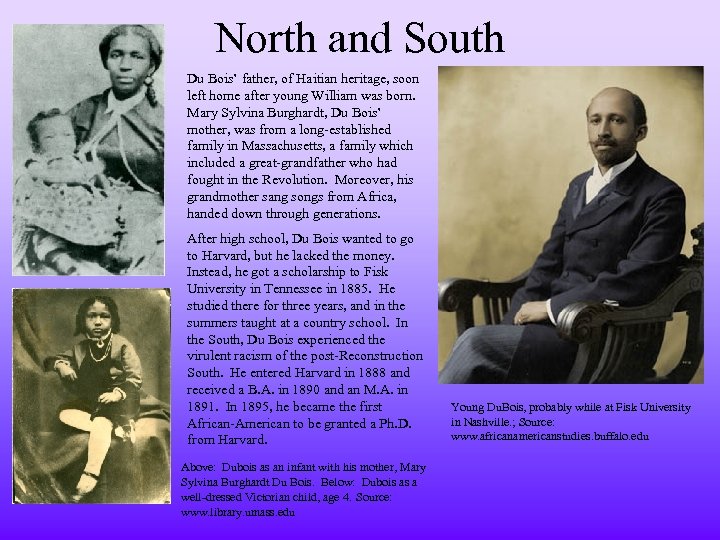

North and South Du Bois’ father, of Haitian heritage, soon left home after young William was born. Mary Sylvina Burghardt, Du Bois’ mother, was from a long-established family in Massachusetts, a family which included a great-grandfather who had fought in the Revolution. Moreover, his grandmother sang songs from Africa, handed down through generations. After high school, Du Bois wanted to go to Harvard, but he lacked the money. Instead, he got a scholarship to Fisk University in Tennessee in 1885. He studied there for three years, and in the summers taught at a country school. In the South, Du Bois experienced the virulent racism of the post-Reconstruction South. He entered Harvard in 1888 and received a B. A. in 1890 and an M. A. in 1891. In 1895, he became the first African-American to be granted a Ph. D. from Harvard. Above: Dubois as an infant with his mother, Mary Sylvina Burghardt Du Bois. Below: Dubois as a well-dressed Victorian child, age 4. Source: www. library. umass. edu Young Du. Bois, probably while at Fisk University in Nashville. ; Source: www. africanamericanstudies. buffalo. edu

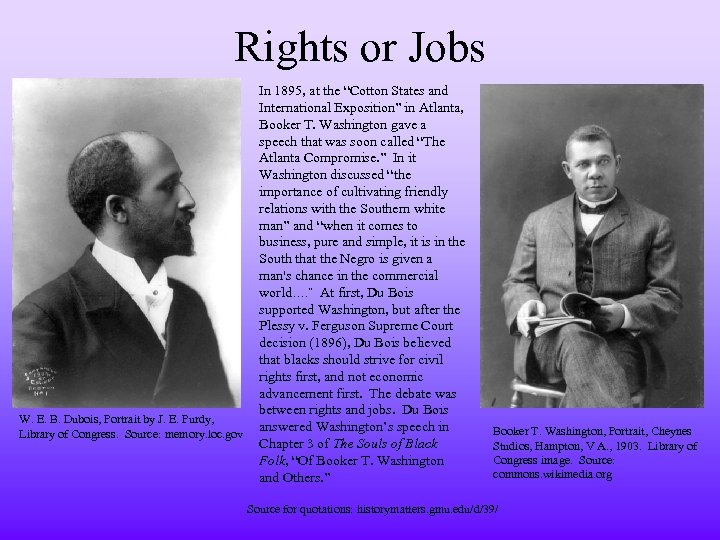

Rights or Jobs W. E. B. Dubois, Portrait by J. E. Purdy, Library of Congress. Source: memory. loc. gov In 1895, at the “Cotton States and International Exposition” in Atlanta, Booker T. Washington gave a speech that was soon called “The Atlanta Compromise. ” In it Washington discussed “the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man” and “when it comes to business, pure and simple, it is in the South that the Negro is given a man's chance in the commercial world…. ” At first, Du Bois supported Washington, but after the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision (1896), Du Bois believed that blacks should strive for civil rights first, and not economic advancement first. The debate was between rights and jobs. Du Bois answered Washington’s speech in Chapter 3 of The Souls of Black Folk, “Of Booker T. Washington and Others. ” Booker T. Washington, Portrait, Cheynes Studios, Hampton, V A. , 1903. Library of Congress image. Source: commons. wikimedia. org Source for quotations: historymatters. gmu. edu/d/39/

The Souls of Black Folk While Du Bois felt that Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist approach to civil rights had to be answered, two other events impelled the writing of The Souls of Black Folk: 1) in 1899, while a sociology professor at Atlanta University, Du Bois’ son, Burghardt, died of diphtheria, and Du Bois felt that the lack of medical facilities for blacks in Atlanta contributed to his son’s death; 2) that same year, a black man named Sam Hose was lynched, accused of killing his landlord and raping his wife--and his knuckles were put on display in a local Atlanta store. The barbarity of that event led to a decision: Du Bois could no longer be a “calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved. ” At the time, The Souls of Black Folk was not something that a “calm, cool, detached scientist, ” trained in German sociological principles in Berlin, would write. Instead, the book mixes Negro spirituals with historical facts, academic argument against Booker T. Washington and personal grief over his son’s death. The work of an impassioned, brilliant mind, the book established Du Bois as an important African American thinker. Source for quotations and facts: www. georgiaencyclopedia. org/nge/Article. jsp? id=h-905 Title page, The Souls of Black Folk, 1903. Source: commons. wikimedia. org

“Booker T. and W. E. B. ” Detroit poet Dudley Randall published this poem in Poem Counterpoem (1966), and it has been anthologized often By the modern Civil Rights movement, Du Bois’ ideas had won. Photo source: www. poetryoutloud. org "It seems to me, " said Booker T. , "It shows a mighty lot of cheek To study chemistry and Greek When Mister Charlie needs a hand To hoe the cotton on his land, And when Miss Ann looks for a cook, Why stick your nose inside a book? " "I don't agree, " said W. E. B. "If I should have the drive to seek Knowledge of chemistry or Greek, I'll do it. Charles and Miss can look Another place for hand or cook, Some men rejoice in skill of hand, And some in cultivating land, But there are others who maintain The right to cultivate the brain. " It seems to me, " said Booker T. , "That all you folks have missed the boat Who shout about the right to vote, And spend vain days and sleepless nights In uproar over civil rights. Just keep your mouths shut, do not grouse, But work, and save, and buy a house. " "I don't agree, " said W. E. B. "For what can property avail If dignity and justice fail? Unless you help to make the laws, They'll steal your house with trumped-up clause. A rope's as tight, a fire as hot, No matter how much cash you've got. Speak soft, and try your little plan, But as for me, I'll be a man. " "It seems to me, " said Booker T. -"I don't agree, " Said W. E. B. /Source: www. huarchivesnet. howard. edu/9908 huarnet/randall. htm

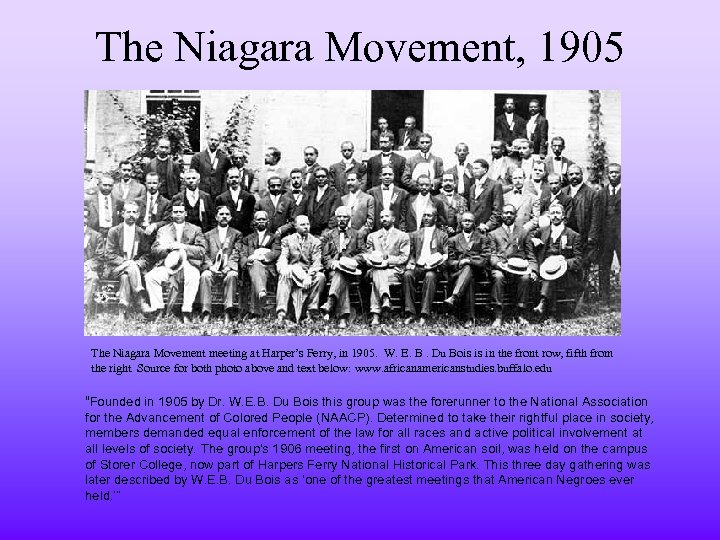

The Niagara Movement, 1905 The Niagara Movement meeting at Harper’s Ferry, in 1905. W. E. B. Du Bois is in the front row, fifth from the right Source for both photo above and text below: www. africanamericanstudies. buffalo. edu “Founded in 1905 by Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois this group was the forerunner to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Determined to take their rightful place in society, members demanded equal enforcement of the law for all races and active political involvement at all levels of society. The group's 1906 meeting, the first on American soil, was held on the campus of Storer College, now part of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. This three day gathering was later described by W. E. B. Du Bois as ‘one of the greatest meetings that American Negroes ever held. ’”

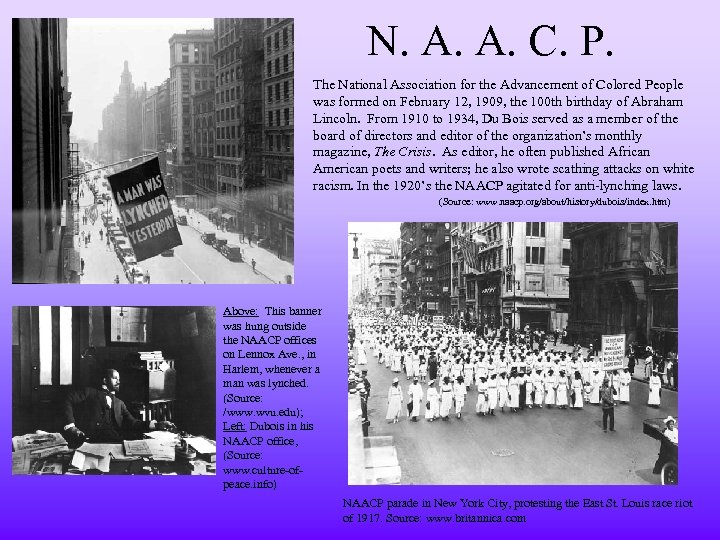

N. A. A. C. P. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was formed on February 12, 1909, the 100 th birthday of Abraham Lincoln. From 1910 to 1934, Du Bois served as a member of the board of directors and editor of the organization’s monthly magazine, The Crisis. As editor, he often published African American poets and writers; he also wrote scathing attacks on white racism. In the 1920’s the NAACP agitated for anti-lynching laws. (Source: www. naacp. org/about/history/dubois/index. htm) Above: This banner was hung outside the NAACP offices on Lennox Ave. , in Harlem, whenever a man was lynched. (Source: /www. wvu. edu); Left: Dubois in his NAACP office, (Source: www. culture-ofpeace. info) NAACP parade in New York City, protesting the East St. Louis race riot of 1917. Source: www. britannica. com

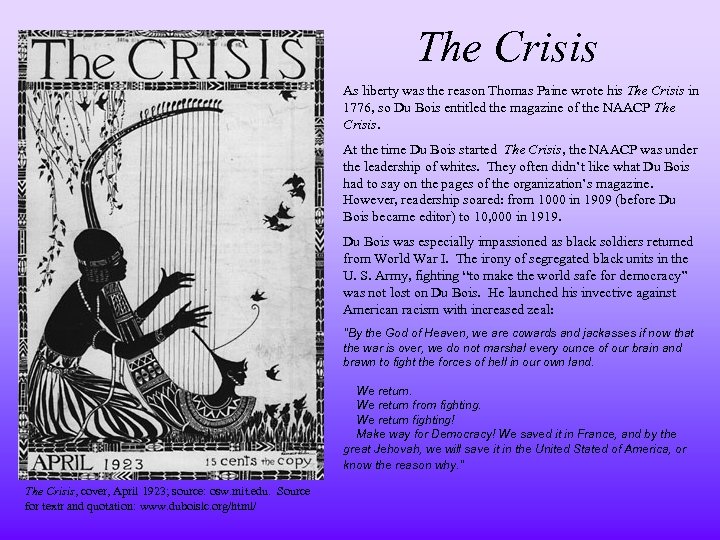

The Crisis As liberty was the reason Thomas Paine wrote his The Crisis in 1776, so Du Bois entitled the magazine of the NAACP The Crisis. At the time Du Bois started The Crisis, the NAACP was under the leadership of whites. They often didn’t like what Du Bois had to say on the pages of the organization’s magazine. However, readership soared: from 1000 in 1909 (before Du Bois became editor) to 10, 000 in 1919. Du Bois was especially impassioned as black soldiers returned from World War I. The irony of segregated black units in the U. S. Army, fighting “to make the world safe for democracy” was not lost on Du Bois. He launched his invective against American racism with increased zeal: "By the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight the forces of hell in our own land. We return from fighting. We return fighting! Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the great Jehovah, we will save it in the United Stated of America, or know the reason why. " The Crisis, cover, April 1923; source: osw. mit. edu. Source for textr and quotation: www. duboislc. org/html/

“Lift Every Voice and Sing” Written by James Weldon Johnson, the poem was set to music by his brother John. In 1919 the NAACP adopted it as “The Negro National Anthem, ” and it soon became popular in African American churches in the South. In 1990, singer Melba Moore recorded the song with other black artists and saw that it was entered into the Congressional Record as “The African American National Hymn. ” James Weldon Johnson Lift every voice and sing, till earth and Heaven ring, Ring with the harmonies of liberty; Let our rejoicing rise, high as the listening skies, Let it resound loud as the rolling sea. Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us, Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us; Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, Let us march on till victory is won. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has been performed countless times; You. Tube has several good renditions: Whitney Young High School (Chicago) Concert Choir : www. youtube. com/watch? v=tf 71 iek. NASk Tennessee State University Choir: www. youtube. com/watch? v=UYd_q. WXB-4 A The Chicago Children’s Choir: http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=6 LAr 9 y. Ibc. DQ And an Obama election memorial—to remind us all: http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=z. Wtx. CW 9 st. Nk&feature=fvw John R. Johnson Stony the road we trod, bitter the chastening rod, Felt in the days when hope unborn had died; Yet with a steady beat, have not our weary feet, Come to the place for which our fathers sighed? We have come over a way that with tears has been watered, We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered; Out from the gloomy past, till now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast. . Source, for both photos and text, plus music: www. cyberhymnal. org/htm/l/i/liftevry. htm

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line" Those famous words appear in the Forward to The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois always saw the problem of racism in the United States as connected to colonialism and racism around the world. Du Bois resigned from the NAACP in 1934 because he became disillusioned with the slow progress against racism in America. Instead, he believed in an African American nationalist strategy: “African American controlled institutions, schools, and economic cooperatives. ” Clearly, such a strategy was opposed to the NAACP belief in integration. He re-joined the NAACP from 1944 -48, and served as a consultant at the founding of the United Nations, writing “An Appeal to the World” in 1947, about the persistence of American racism. The persistence of racism in America reinforced Du Bois’ belief that the situation of American blacks was similar to the condition of Africans under European colonialism. He had attended the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900, and he helped organize a series of such congresses around the world in 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927. Despairing of America’s ability to deal with racism, Du Bois became a citizen of Ghana in 1961; he was given a state funeral in Ghana on Aug 27, 1963; ironically, he was buried the day before Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Source: www. naacp. org/about/history/dubois/index. htm Du Bois in 1946; photo by Carl Van Vechten; Library of Congress. Source: en. wikipedia. org

c71ceca523139b2ed5ec973d64c98332.ppt