abc66c3fffc519f3e5f1a60f5b6901fe.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 1

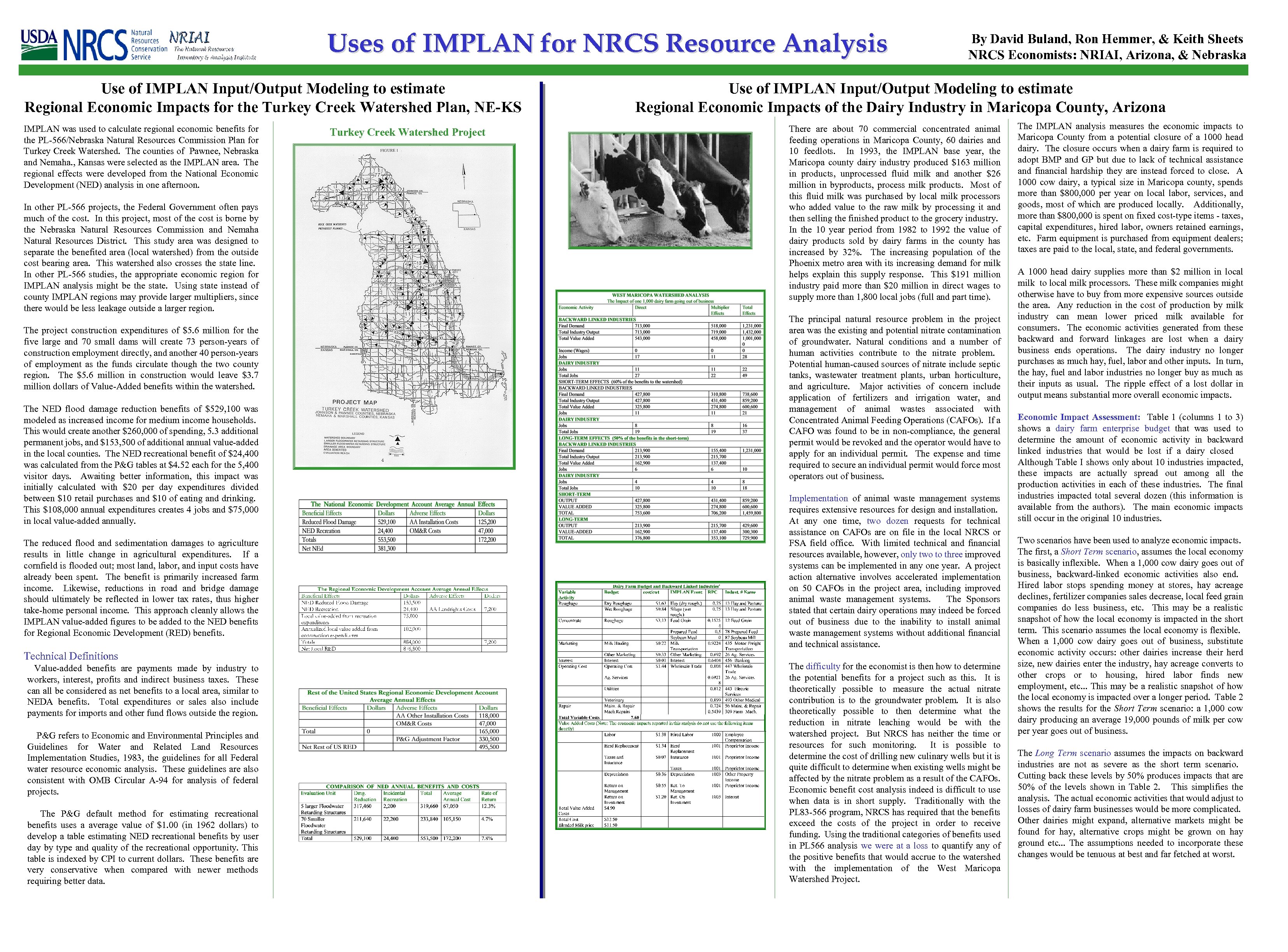

Uses of IMPLAN for NRCS Resource Analysis Use of IMPLAN Input/Output Modeling to estimate Regional Economic Impacts for the Turkey Creek Watershed Plan, NE-KS IMPLAN was used to calculate regional economic benefits for the PL-566/Nebraska Natural Resources Commission Plan for Turkey Creek Watershed. The counties of Pawnee, Nebraska and Nemaha. , Kansas were selected as the IMPLAN area. The regional effects were developed from the National Economic Development (NED) analysis in one afternoon. In other PL-566 projects, the Federal Government often pays much of the cost. In this project, most of the cost is borne by the Nebraska Natural Resources Commission and Nemaha Natural Resources District. This study area was designed to separate the benefited area (local watershed) from the outside cost bearing area. This watershed also crosses the state line. In other PL-566 studies, the appropriate economic region for IMPLAN analysis might be the state. Using state instead of county IMPLAN regions may provide larger multipliers, since there would be less leakage outside a larger region. The project construction expenditures of $5. 6 million for the five large and 70 small dams will create 73 person-years of construction employment directly, and another 40 person-years of employment as the funds circulate though the two county region. The $5. 6 million in construction would leave $3. 7 million dollars of Value-Added benefits within the watershed. The NED flood damage reduction benefits of $529, 100 was modeled as increased income for medium income households. This would create another $260, 000 of spending, 5. 3 additional permanent jobs, and $153, 500 of additional annual value-added in the local counties. The NED recreational benefit of $24, 400 was calculated from the P&G tables at $4. 52 each for the 5, 400 visitor days. Awaiting better information, this impact was initially calculated with $20 per day expenditures divided between $10 retail purchases and $10 of eating and drinking. This $108, 000 annual expenditures creates 4 jobs and $75, 000 in local value-added annually. The reduced flood and sedimentation damages to agriculture results in little change in agricultural expenditures. If a cornfield is flooded out; most land, labor, and input costs have already been spent. The benefit is primarily increased farm income. Likewise, reductions in road and bridge damage should ultimately be reflected in lower tax rates, thus higher take-home personal income. This approach cleanly allows the IMPLAN value-added figures to be added to the NED benefits for Regional Economic Development (RED) benefits. Technical Definitions Value-added benefits are payments made by industry to workers, interest, profits and indirect business taxes. These can all be considered as net benefits to a local area, similar to NEDA benefits. Total expenditures or sales also include payments for imports and other fund flows outside the region. P&G refers to Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies, 1983, the guidelines for all Federal water resource economic analysis. These guidelines are also consistent with OMB Circular A-94 for analysis of federal projects. The P&G default method for estimating recreational benefits uses a average value of $1. 00 (in 1962 dollars) to develop a table estimating NED recreational benefits by user day by type and quality of the recreational opportunity. This table is indexed by CPI to current dollars. These benefits are very conservative when compared with newer methods requiring better data. Turkey Creek Watershed Project By David Buland, Ron Hemmer, & Keith Sheets NRCS Economists: NRIAI, Arizona, & Nebraska Use of IMPLAN Input/Output Modeling to estimate Regional Economic Impacts of the Dairy Industry in Maricopa County, Arizona There about 70 commercial concentrated animal feeding operations in Maricopa County, 60 dairies and 10 feedlots. In 1993, the IMPLAN base year, the Maricopa county dairy industry produced $163 million in products, unprocessed fluid milk and another $26 million in byproducts, process milk products. Most of this fluid milk was purchased by local milk processors who added value to the raw milk by processing it and then selling the finished product to the grocery industry. In the 10 year period from 1982 to 1992 the value of dairy products sold by dairy farms in the county has increased by 32%. The increasing population of the Phoenix metro area with its increasing demand for milk helps explain this supply response. This $191 million industry paid more than $20 million in direct wages to supply more than 1, 800 local jobs (full and part time). The principal natural resource problem in the project area was the existing and potential nitrate contamination of groundwater. Natural conditions and a number of human activities contribute to the nitrate problem. Potential human-caused sources of nitrate include septic tanks, wastewater treatment plants, urban horticulture, and agriculture. Major activities of concern include application of fertilizers and irrigation water, and management of animal wastes associated with Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). If a CAFO was found to be in non-compliance, the general permit would be revoked and the operator would have to apply for an individual permit. The expense and time required to secure an individual permit would force most operators out of business. Implementation of animal waste management systems requires extensive resources for design and installation. At any one time, two dozen requests for technical assistance on CAFOs are on file in the local NRCS or FSA field office. With limited technical and financial resources available, however, only two to three improved systems can be implemented in any one year. A project action alternative involves accelerated implementation on 50 CAFOs in the project area, including improved animal waste management systems. The Sponsors stated that certain dairy operations may indeed be forced out of business due to the inability to install animal waste management systems without additional financial and technical assistance. The difficulty for the economist is then how to determine the potential benefits for a project such as this. It is theoretically possible to measure the actual nitrate contribution is to the groundwater problem. It is also theoretically possible to then determine what the reduction in nitrate leaching would be with the watershed project. But NRCS has neither the time or resources for such monitoring. It is possible to determine the cost of drilling new culinary wells but it is quite difficult to determine when existing wells might be affected by the nitrate problem as a result of the CAFOs. Economic benefit cost analysis indeed is difficult to use when data is in short supply. Traditionally with the PL 83 -566 program, NRCS has required that the benefits exceed the costs of the project in order to receive funding. Using the traditional categories of benefits used in PL 566 analysis we were at a loss to quantify any of the positive benefits that would accrue to the watershed with the implementation of the West Maricopa Watershed Project. The IMPLAN analysis measures the economic impacts to Maricopa County from a potential closure of a 1000 head dairy. The closure occurs when a dairy farm is required to adopt BMP and GP but due to lack of technical assistance and financial hardship they are instead forced to close. A 1000 cow dairy, a typical size in Maricopa county, spends more than $800, 000 per year on local labor, services, and goods, most of which are produced locally. Additionally, more than $800, 000 is spent on fixed cost-type items - taxes, capital expenditures, hired labor, owners retained earnings, etc. Farm equipment is purchased from equipment dealers; taxes are paid to the local, state, and federal governments. A 1000 head dairy supplies more than $2 million in local milk to local milk processors. These milk companies might otherwise have to buy from more expensive sources outside the area. Any reduction in the cost of production by milk industry can mean lower priced milk available for consumers. The economic activities generated from these backward and forward linkages are lost when a dairy business ends operations. The dairy industry no longer purchases as much hay, fuel, labor and other inputs. In turn, the hay, fuel and labor industries no longer buy as much as their inputs as usual. The ripple effect of a lost dollar in output means substantial more overall economic impacts. Economic Impact Assessment: Table 1 (columns 1 to 3) shows a dairy farm enterprise budget that was used to determine the amount of economic activity in backward linked industries that would be lost if a dairy closed Although Table I shows only about 10 industries impacted, these impacts are actually spread out among all the production activities in each of these industries. The final industries impacted total several dozen (this information is available from the authors). The main economic impacts still occur in the original 10 industries. Two scenarios have been used to analyze economic impacts. The first, a Short Term scenario, assumes the local economy is basically inflexible. When a 1, 000 cow dairy goes out of business, backward-linked economic activities also end. Hired labor stops spending money at stores, hay acreage declines, fertilizer companies sales decrease, local feed grain companies do less business, etc. This may be a realistic snapshot of how the local economy is impacted in the short term. This scenario assumes the local economy is flexible. When a 1, 000 cow dairy goes out of business, substitute economic activity occurs: other dairies increase their herd size, new dairies enter the industry, hay acreage converts to other crops or to housing, hired labor finds new employment, etc. . . This may be a realistic snapshot of how the local economy is impacted over a longer period. Table 2 shows the results for the Short Term scenario: a 1, 000 cow dairy producing an average 19, 000 pounds of milk per cow per year goes out of business. The Long Term scenario assumes the impacts on backward industries are not as severe as the short term scenario. Cutting back these levels by 50% produces impacts that are 50% of the levels shown in Table 2. This simplifies the analysis. The actual economic activities that would adjust to losses of dairy farm businesses would be more complicated. Other dairies might expand, alternative markets might be found for hay, alternative crops might be grown on hay ground etc. . . The assumptions needed to incorporate these changes would be tenuous at best and far fetched at worst.

Uses of IMPLAN for NRCS Resource Analysis Use of IMPLAN Input/Output Modeling to estimate Regional Economic Impacts for the Turkey Creek Watershed Plan, NE-KS IMPLAN was used to calculate regional economic benefits for the PL-566/Nebraska Natural Resources Commission Plan for Turkey Creek Watershed. The counties of Pawnee, Nebraska and Nemaha. , Kansas were selected as the IMPLAN area. The regional effects were developed from the National Economic Development (NED) analysis in one afternoon. In other PL-566 projects, the Federal Government often pays much of the cost. In this project, most of the cost is borne by the Nebraska Natural Resources Commission and Nemaha Natural Resources District. This study area was designed to separate the benefited area (local watershed) from the outside cost bearing area. This watershed also crosses the state line. In other PL-566 studies, the appropriate economic region for IMPLAN analysis might be the state. Using state instead of county IMPLAN regions may provide larger multipliers, since there would be less leakage outside a larger region. The project construction expenditures of $5. 6 million for the five large and 70 small dams will create 73 person-years of construction employment directly, and another 40 person-years of employment as the funds circulate though the two county region. The $5. 6 million in construction would leave $3. 7 million dollars of Value-Added benefits within the watershed. The NED flood damage reduction benefits of $529, 100 was modeled as increased income for medium income households. This would create another $260, 000 of spending, 5. 3 additional permanent jobs, and $153, 500 of additional annual value-added in the local counties. The NED recreational benefit of $24, 400 was calculated from the P&G tables at $4. 52 each for the 5, 400 visitor days. Awaiting better information, this impact was initially calculated with $20 per day expenditures divided between $10 retail purchases and $10 of eating and drinking. This $108, 000 annual expenditures creates 4 jobs and $75, 000 in local value-added annually. The reduced flood and sedimentation damages to agriculture results in little change in agricultural expenditures. If a cornfield is flooded out; most land, labor, and input costs have already been spent. The benefit is primarily increased farm income. Likewise, reductions in road and bridge damage should ultimately be reflected in lower tax rates, thus higher take-home personal income. This approach cleanly allows the IMPLAN value-added figures to be added to the NED benefits for Regional Economic Development (RED) benefits. Technical Definitions Value-added benefits are payments made by industry to workers, interest, profits and indirect business taxes. These can all be considered as net benefits to a local area, similar to NEDA benefits. Total expenditures or sales also include payments for imports and other fund flows outside the region. P&G refers to Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies, 1983, the guidelines for all Federal water resource economic analysis. These guidelines are also consistent with OMB Circular A-94 for analysis of federal projects. The P&G default method for estimating recreational benefits uses a average value of $1. 00 (in 1962 dollars) to develop a table estimating NED recreational benefits by user day by type and quality of the recreational opportunity. This table is indexed by CPI to current dollars. These benefits are very conservative when compared with newer methods requiring better data. Turkey Creek Watershed Project By David Buland, Ron Hemmer, & Keith Sheets NRCS Economists: NRIAI, Arizona, & Nebraska Use of IMPLAN Input/Output Modeling to estimate Regional Economic Impacts of the Dairy Industry in Maricopa County, Arizona There about 70 commercial concentrated animal feeding operations in Maricopa County, 60 dairies and 10 feedlots. In 1993, the IMPLAN base year, the Maricopa county dairy industry produced $163 million in products, unprocessed fluid milk and another $26 million in byproducts, process milk products. Most of this fluid milk was purchased by local milk processors who added value to the raw milk by processing it and then selling the finished product to the grocery industry. In the 10 year period from 1982 to 1992 the value of dairy products sold by dairy farms in the county has increased by 32%. The increasing population of the Phoenix metro area with its increasing demand for milk helps explain this supply response. This $191 million industry paid more than $20 million in direct wages to supply more than 1, 800 local jobs (full and part time). The principal natural resource problem in the project area was the existing and potential nitrate contamination of groundwater. Natural conditions and a number of human activities contribute to the nitrate problem. Potential human-caused sources of nitrate include septic tanks, wastewater treatment plants, urban horticulture, and agriculture. Major activities of concern include application of fertilizers and irrigation water, and management of animal wastes associated with Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs). If a CAFO was found to be in non-compliance, the general permit would be revoked and the operator would have to apply for an individual permit. The expense and time required to secure an individual permit would force most operators out of business. Implementation of animal waste management systems requires extensive resources for design and installation. At any one time, two dozen requests for technical assistance on CAFOs are on file in the local NRCS or FSA field office. With limited technical and financial resources available, however, only two to three improved systems can be implemented in any one year. A project action alternative involves accelerated implementation on 50 CAFOs in the project area, including improved animal waste management systems. The Sponsors stated that certain dairy operations may indeed be forced out of business due to the inability to install animal waste management systems without additional financial and technical assistance. The difficulty for the economist is then how to determine the potential benefits for a project such as this. It is theoretically possible to measure the actual nitrate contribution is to the groundwater problem. It is also theoretically possible to then determine what the reduction in nitrate leaching would be with the watershed project. But NRCS has neither the time or resources for such monitoring. It is possible to determine the cost of drilling new culinary wells but it is quite difficult to determine when existing wells might be affected by the nitrate problem as a result of the CAFOs. Economic benefit cost analysis indeed is difficult to use when data is in short supply. Traditionally with the PL 83 -566 program, NRCS has required that the benefits exceed the costs of the project in order to receive funding. Using the traditional categories of benefits used in PL 566 analysis we were at a loss to quantify any of the positive benefits that would accrue to the watershed with the implementation of the West Maricopa Watershed Project. The IMPLAN analysis measures the economic impacts to Maricopa County from a potential closure of a 1000 head dairy. The closure occurs when a dairy farm is required to adopt BMP and GP but due to lack of technical assistance and financial hardship they are instead forced to close. A 1000 cow dairy, a typical size in Maricopa county, spends more than $800, 000 per year on local labor, services, and goods, most of which are produced locally. Additionally, more than $800, 000 is spent on fixed cost-type items - taxes, capital expenditures, hired labor, owners retained earnings, etc. Farm equipment is purchased from equipment dealers; taxes are paid to the local, state, and federal governments. A 1000 head dairy supplies more than $2 million in local milk to local milk processors. These milk companies might otherwise have to buy from more expensive sources outside the area. Any reduction in the cost of production by milk industry can mean lower priced milk available for consumers. The economic activities generated from these backward and forward linkages are lost when a dairy business ends operations. The dairy industry no longer purchases as much hay, fuel, labor and other inputs. In turn, the hay, fuel and labor industries no longer buy as much as their inputs as usual. The ripple effect of a lost dollar in output means substantial more overall economic impacts. Economic Impact Assessment: Table 1 (columns 1 to 3) shows a dairy farm enterprise budget that was used to determine the amount of economic activity in backward linked industries that would be lost if a dairy closed Although Table I shows only about 10 industries impacted, these impacts are actually spread out among all the production activities in each of these industries. The final industries impacted total several dozen (this information is available from the authors). The main economic impacts still occur in the original 10 industries. Two scenarios have been used to analyze economic impacts. The first, a Short Term scenario, assumes the local economy is basically inflexible. When a 1, 000 cow dairy goes out of business, backward-linked economic activities also end. Hired labor stops spending money at stores, hay acreage declines, fertilizer companies sales decrease, local feed grain companies do less business, etc. This may be a realistic snapshot of how the local economy is impacted in the short term. This scenario assumes the local economy is flexible. When a 1, 000 cow dairy goes out of business, substitute economic activity occurs: other dairies increase their herd size, new dairies enter the industry, hay acreage converts to other crops or to housing, hired labor finds new employment, etc. . . This may be a realistic snapshot of how the local economy is impacted over a longer period. Table 2 shows the results for the Short Term scenario: a 1, 000 cow dairy producing an average 19, 000 pounds of milk per cow per year goes out of business. The Long Term scenario assumes the impacts on backward industries are not as severe as the short term scenario. Cutting back these levels by 50% produces impacts that are 50% of the levels shown in Table 2. This simplifies the analysis. The actual economic activities that would adjust to losses of dairy farm businesses would be more complicated. Other dairies might expand, alternative markets might be found for hay, alternative crops might be grown on hay ground etc. . . The assumptions needed to incorporate these changes would be tenuous at best and far fetched at worst.