US and UK Educational Systems. Overview of the

british_educational_system.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 32

US and UK Educational Systems

US and UK Educational Systems

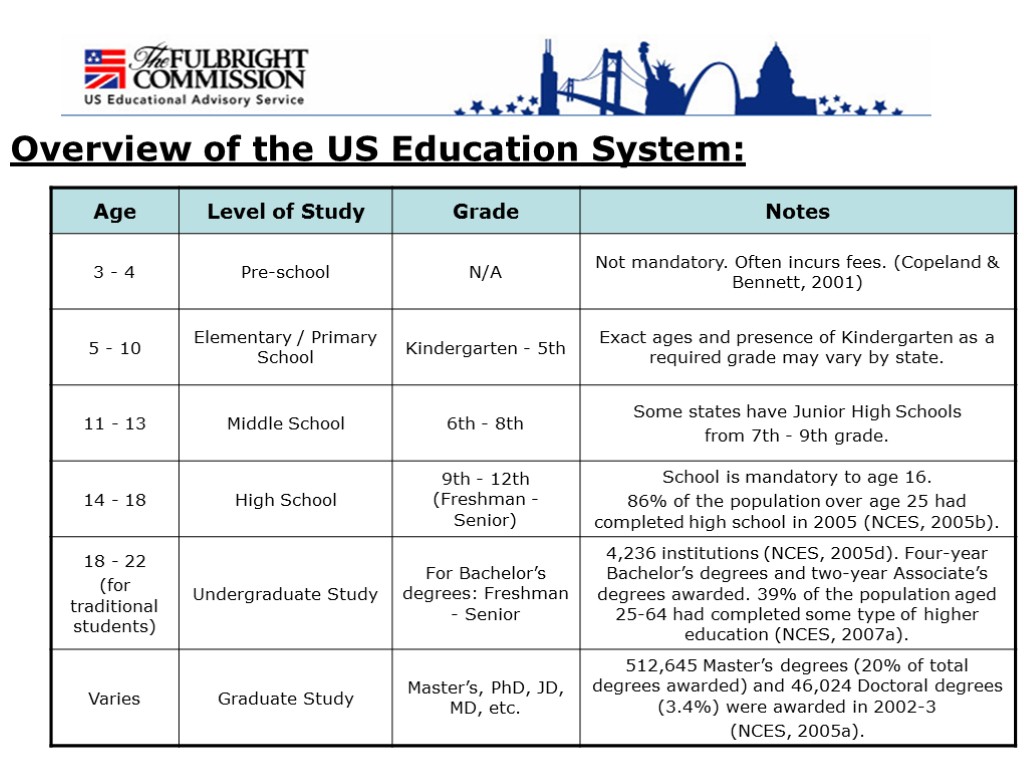

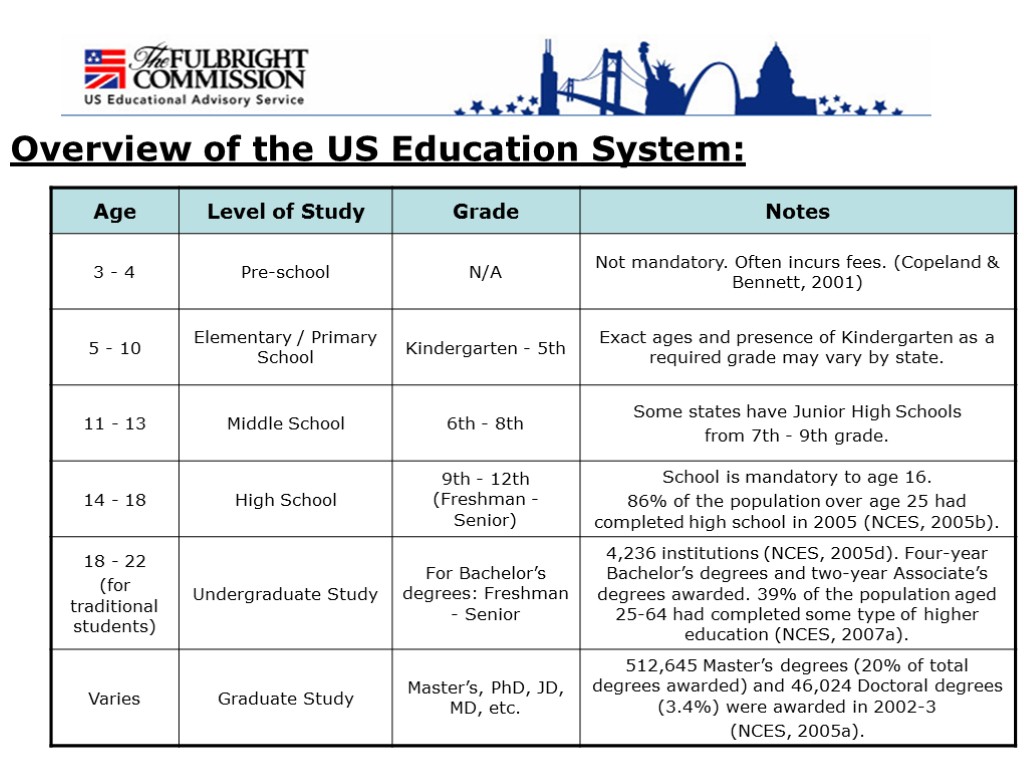

Overview of the US Education System:

Overview of the US Education System:

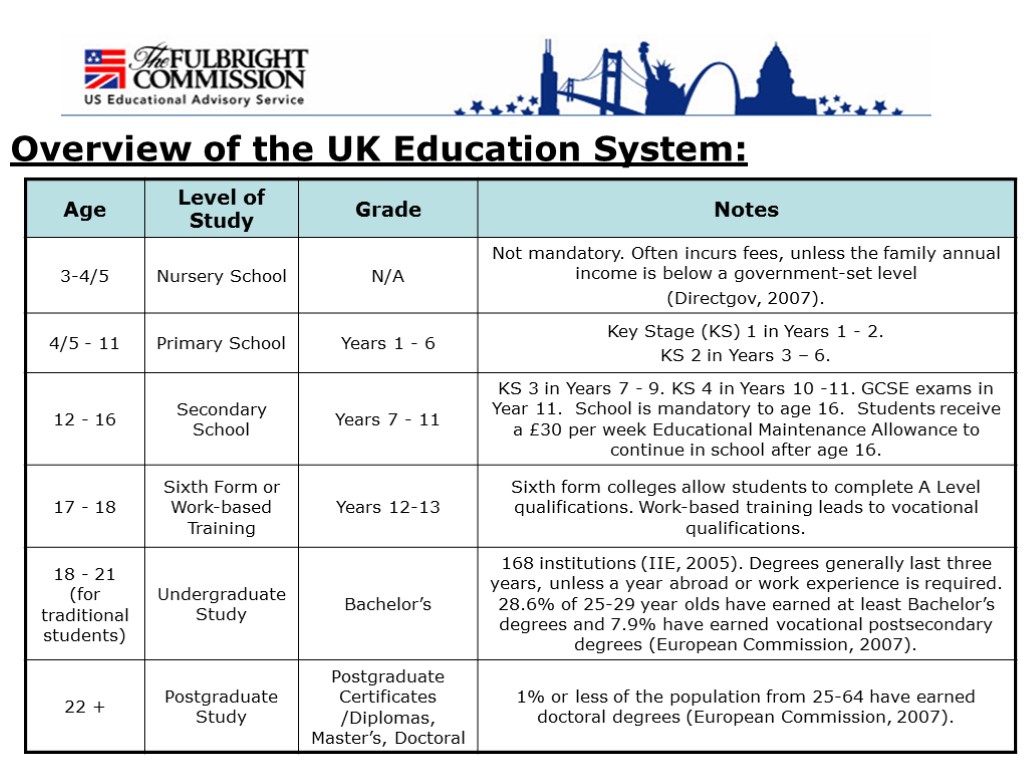

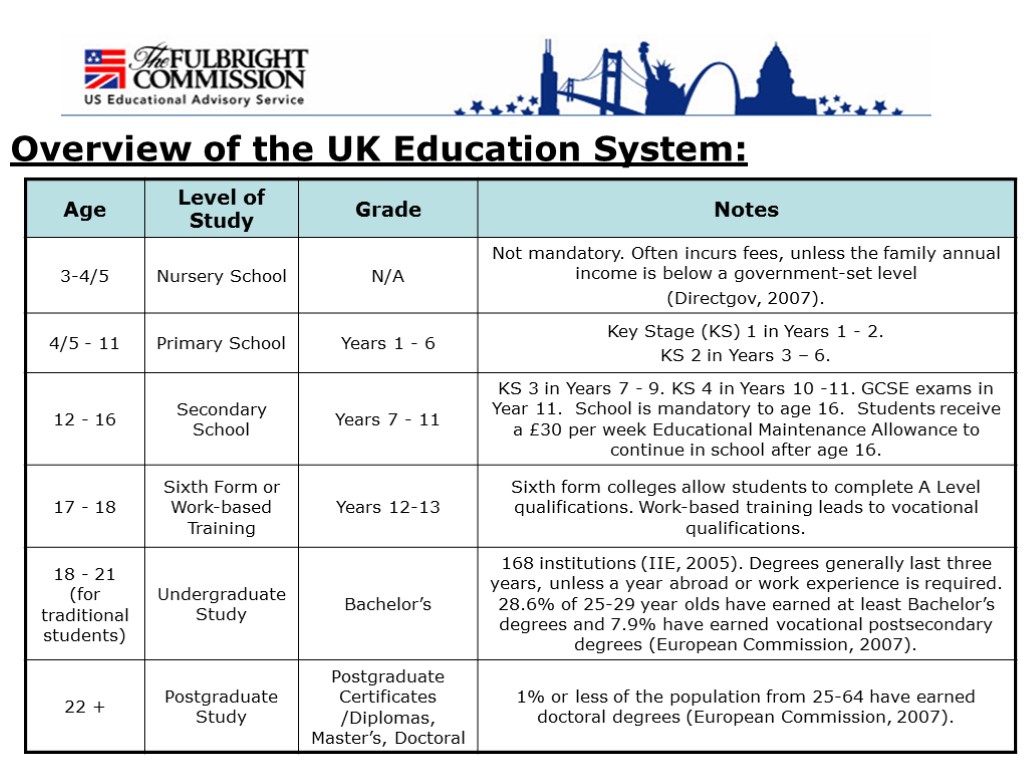

Overview of the UK Education System:

Overview of the UK Education System:

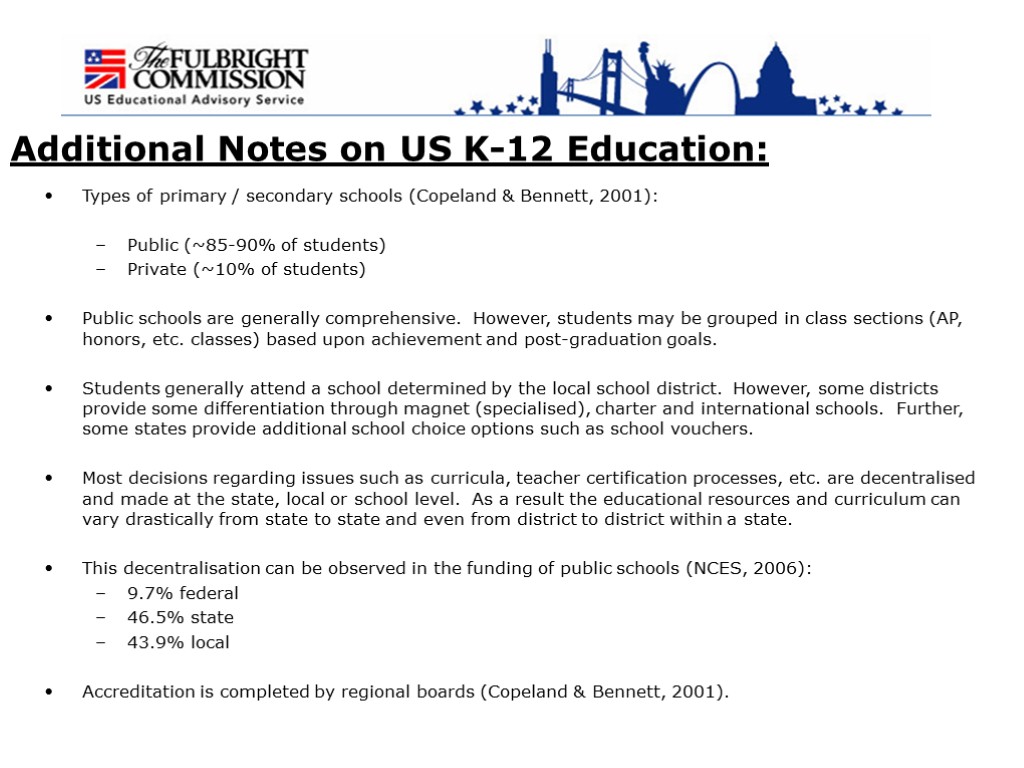

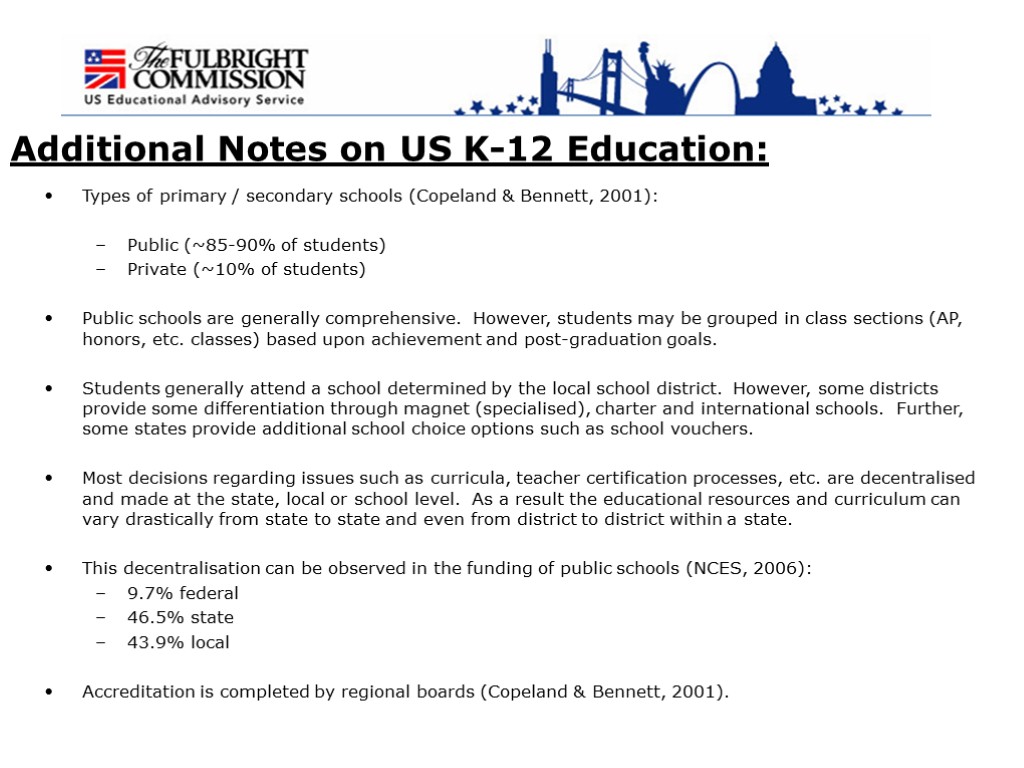

Additional Notes on US K-12 Education: Types of primary / secondary schools (Copeland & Bennett, 2001): Public (~85-90% of students) Private (~10% of students) Public schools are generally comprehensive. However, students may be grouped in class sections (AP, honors, etc. classes) based upon achievement and post-graduation goals. Students generally attend a school determined by the local school district. However, some districts provide some differentiation through magnet (specialised), charter and international schools. Further, some states provide additional school choice options such as school vouchers. Most decisions regarding issues such as curricula, teacher certification processes, etc. are decentralised and made at the state, local or school level. As a result the educational resources and curriculum can vary drastically from state to state and even from district to district within a state. This decentralisation can be observed in the funding of public schools (NCES, 2006): 9.7% federal 46.5% state 43.9% local Accreditation is completed by regional boards (Copeland & Bennett, 2001).

Additional Notes on US K-12 Education: Types of primary / secondary schools (Copeland & Bennett, 2001): Public (~85-90% of students) Private (~10% of students) Public schools are generally comprehensive. However, students may be grouped in class sections (AP, honors, etc. classes) based upon achievement and post-graduation goals. Students generally attend a school determined by the local school district. However, some districts provide some differentiation through magnet (specialised), charter and international schools. Further, some states provide additional school choice options such as school vouchers. Most decisions regarding issues such as curricula, teacher certification processes, etc. are decentralised and made at the state, local or school level. As a result the educational resources and curriculum can vary drastically from state to state and even from district to district within a state. This decentralisation can be observed in the funding of public schools (NCES, 2006): 9.7% federal 46.5% state 43.9% local Accreditation is completed by regional boards (Copeland & Bennett, 2001).

US K-12 Student Assessment: Assessment can vary significantly from school to school and even from teacher to teacher within the same school. Students are generally assessed continually throughout a semester, via a combination of tests, mid-term/final exams, papers, quizzes, homework assignments, classroom participation, group work, projects, attendance, etc. (Copeland & Bennett, 2001). This assessment culminates with a final ‘grade’ for each course awarded at the end of the semester. These grades are weighted according to the number of credit hours of the course and averaged over the student’s high school career, resulting in a ‘Grade Point Average’ (GPA). Students may also receive a ‘class rank’ and/or level of distinction at graduation, such as ‘summa cum laude’ (GPA: 3.75 and above), ‘magna cum laude’ (GPA: 3.5 - 3.74) and ‘cum laude’ (GPA: 3.25 - 3.49) or ‘valedictorian’ (class rank of 1) and ‘salutatorian’ (class rank of 2). To graduate, a student must typically pass the courses outlined in a curriculum set by state or school officials. Under the ‘No Child Left Behind’ policy, students also complete state exams in reading/language arts and math in Grades 3-8 and once at the high school level. In 2007/08, a science exam will be introduced at the elementary, middle and high school levels (US Department of Education, 2007).

US K-12 Student Assessment: Assessment can vary significantly from school to school and even from teacher to teacher within the same school. Students are generally assessed continually throughout a semester, via a combination of tests, mid-term/final exams, papers, quizzes, homework assignments, classroom participation, group work, projects, attendance, etc. (Copeland & Bennett, 2001). This assessment culminates with a final ‘grade’ for each course awarded at the end of the semester. These grades are weighted according to the number of credit hours of the course and averaged over the student’s high school career, resulting in a ‘Grade Point Average’ (GPA). Students may also receive a ‘class rank’ and/or level of distinction at graduation, such as ‘summa cum laude’ (GPA: 3.75 and above), ‘magna cum laude’ (GPA: 3.5 - 3.74) and ‘cum laude’ (GPA: 3.25 - 3.49) or ‘valedictorian’ (class rank of 1) and ‘salutatorian’ (class rank of 2). To graduate, a student must typically pass the courses outlined in a curriculum set by state or school officials. Under the ‘No Child Left Behind’ policy, students also complete state exams in reading/language arts and math in Grades 3-8 and once at the high school level. In 2007/08, a science exam will be introduced at the elementary, middle and high school levels (US Department of Education, 2007).

Additional Notes on UK K-12 Education: Types of primary / secondary schools (Directgov, 2007): State-funded schools, which follow the ‘National Curriculum’ Independent or ‘public schools’, which set their own curricula and are funded by student fees and interest earned on school endowments/investments Students apply for a place at a school, and the school sets its own admissions criteria. Assessment of schools: The Office for Standards in Education, Child Services and Skills (Ofsted) inspects state-funded schools (and some independent schools) every three years and publishes the results online (Ofsted, 2007). The Department for Education and Skills publishes school achievement tables, listing average student scores at KS 2-4 and post-16 qualifications (Directgov, 2007). The Independent Schools Inspectorate also assesses independent schools.

Additional Notes on UK K-12 Education: Types of primary / secondary schools (Directgov, 2007): State-funded schools, which follow the ‘National Curriculum’ Independent or ‘public schools’, which set their own curricula and are funded by student fees and interest earned on school endowments/investments Students apply for a place at a school, and the school sets its own admissions criteria. Assessment of schools: The Office for Standards in Education, Child Services and Skills (Ofsted) inspects state-funded schools (and some independent schools) every three years and publishes the results online (Ofsted, 2007). The Department for Education and Skills publishes school achievement tables, listing average student scores at KS 2-4 and post-16 qualifications (Directgov, 2007). The Independent Schools Inspectorate also assesses independent schools.

UK K-12 Student Assessment: The UK government sets a K-12 National Curriculum and assessment framework (Directgov, 2007). At the end of KS 1, teachers assess students in English and Maths, and at the end of KS 2 and 3, students complete national tests in English, Maths and Science. At the end of KS 4, students take GCSE exams (General Certificate of Secondary Education). Students may choose the number and subject of their exams (from the 48 GCSE exams available). They may opt to sit higher (possible results: A* - D) or lower (C-G) level exams. However, English, Maths and Science are required subjects, and UK universities typically expect students to sit at least five GCSE exams. Students continuing on an educational track after GCSEs attend sixth form colleges and sit AS (Advanced Subsidiary) and/or A2 Level exams. Students on a work-based training scheme after GCSEs may earn vocational qualifications, such as the NVQ. Students may attend sixth form for one year, sit the AS Level exams and leave with AS Level qualifications. Alternatively, students may continue after the AS Level exams for a second year, sit the A2 Level exams and leave with A (Advanced) Level qualifications. Students may choose the number and subjects of their exams (from the 80 subjects available). However, universities typically expect students to complete at least 2 A Level exams, and some courses may specify A Level subjects and results required for admission. AS, A2 and A Level results range from A – E, and AS and A2 Level results are combined to generate the A Level final results. and are awarded by one of five exam boards (QCA, 2007). Final results are generally determined by a combined outside assessment of an examination (70%) and teacher assessment of coursework (30%).

UK K-12 Student Assessment: The UK government sets a K-12 National Curriculum and assessment framework (Directgov, 2007). At the end of KS 1, teachers assess students in English and Maths, and at the end of KS 2 and 3, students complete national tests in English, Maths and Science. At the end of KS 4, students take GCSE exams (General Certificate of Secondary Education). Students may choose the number and subject of their exams (from the 48 GCSE exams available). They may opt to sit higher (possible results: A* - D) or lower (C-G) level exams. However, English, Maths and Science are required subjects, and UK universities typically expect students to sit at least five GCSE exams. Students continuing on an educational track after GCSEs attend sixth form colleges and sit AS (Advanced Subsidiary) and/or A2 Level exams. Students on a work-based training scheme after GCSEs may earn vocational qualifications, such as the NVQ. Students may attend sixth form for one year, sit the AS Level exams and leave with AS Level qualifications. Alternatively, students may continue after the AS Level exams for a second year, sit the A2 Level exams and leave with A (Advanced) Level qualifications. Students may choose the number and subjects of their exams (from the 80 subjects available). However, universities typically expect students to complete at least 2 A Level exams, and some courses may specify A Level subjects and results required for admission. AS, A2 and A Level results range from A – E, and AS and A2 Level results are combined to generate the A Level final results. and are awarded by one of five exam boards (QCA, 2007). Final results are generally determined by a combined outside assessment of an examination (70%) and teacher assessment of coursework (30%).

US Undergraduate Curriculum: Degrees are awarded on the satisfactory completion of a set number of credit hours or courses (N. Morales, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Some ‘degree programs’ also have a capstone project or the option of a department or honors thesis in the final year. Under the ‘liberal arts philosophy’, a degree program may include a combination of required major courses, electives within the major, electives outside the major and/or general education requirements in a variety of disciplines. The curriculum is generally determined by the university or faculty within the department.

US Undergraduate Curriculum: Degrees are awarded on the satisfactory completion of a set number of credit hours or courses (N. Morales, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Some ‘degree programs’ also have a capstone project or the option of a department or honors thesis in the final year. Under the ‘liberal arts philosophy’, a degree program may include a combination of required major courses, electives within the major, electives outside the major and/or general education requirements in a variety of disciplines. The curriculum is generally determined by the university or faculty within the department.

US Undergraduate Assessment: Assessment can vary significantly from university to university and even from professor to professor within the same department (N. Morales, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Students are generally assessed continually throughout a semester, via a combination of tests, mid-term/final exams, papers, quizzes, homework assignments, classroom participation, group work, projects, attendance, etc. This assessment culminates with a final ‘grade’ for each class, awarded at the end of the semester. These grades are weighted according to the number of credit hours of the course and averaged over the student’s undergraduate career, resulting in a ‘GPA’. Students may also receive a ‘class rank’ and/or level of distinction at graduation, such as ‘summa cum laude’ (GPA: 3.75 and above), ‘magna cum laude’ (GPA: 3.5 - 3.74) and ‘cum laude’ (GPA: 3.25 - 3.49) or ‘valedictorian’ (class rank of 1) and ‘salutatorian’ (class rank of 2). To graduate, a student must typically pass the classes outlined in a degree curriculum for a particular major set by department and/or university officials.

US Undergraduate Assessment: Assessment can vary significantly from university to university and even from professor to professor within the same department (N. Morales, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Students are generally assessed continually throughout a semester, via a combination of tests, mid-term/final exams, papers, quizzes, homework assignments, classroom participation, group work, projects, attendance, etc. This assessment culminates with a final ‘grade’ for each class, awarded at the end of the semester. These grades are weighted according to the number of credit hours of the course and averaged over the student’s undergraduate career, resulting in a ‘GPA’. Students may also receive a ‘class rank’ and/or level of distinction at graduation, such as ‘summa cum laude’ (GPA: 3.75 and above), ‘magna cum laude’ (GPA: 3.5 - 3.74) and ‘cum laude’ (GPA: 3.25 - 3.49) or ‘valedictorian’ (class rank of 1) and ‘salutatorian’ (class rank of 2). To graduate, a student must typically pass the classes outlined in a degree curriculum for a particular major set by department and/or university officials.

US Undergraduate Admissions: At the undergraduate level, US students apply to each university individually. Students generally submit applications to the university admissions office, rather than the department in which they plan to study (B. Costello, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Admissions decisions are made by ‘admissions counselors’ upon evaluation of a package typically containing: the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular activities essay(s) 2-3 letters of recommendation by school or community representatives admissions exam results (SAT I, SAT II and/or ACT) a transcript of high school grades admissions fee, often ranging from $50-100 per university Admissions decisions generally take into account a wide range of factors: a student’s academic record, extracurricular or community involvement during high school, work experience, character, leadership abilities, motivations, interest in attending the specific university or studying a particular field, etc.

US Undergraduate Admissions: At the undergraduate level, US students apply to each university individually. Students generally submit applications to the university admissions office, rather than the department in which they plan to study (B. Costello, personal communication, July 24, 2007). Admissions decisions are made by ‘admissions counselors’ upon evaluation of a package typically containing: the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular activities essay(s) 2-3 letters of recommendation by school or community representatives admissions exam results (SAT I, SAT II and/or ACT) a transcript of high school grades admissions fee, often ranging from $50-100 per university Admissions decisions generally take into account a wide range of factors: a student’s academic record, extracurricular or community involvement during high school, work experience, character, leadership abilities, motivations, interest in attending the specific university or studying a particular field, etc.

US Graduate Curriculum: Academic/research degree programs (Master’s, PhD) (EAS, 1999): These programs typically begin with a significant classroom-based component (required classes and possibly electives). Following the completion of ‘comprehensive exams’ on class content, students may progress to ‘doctoral candidacy’. An academic/research Master’s or PhD will also include a significant research component, as well as completion and publication of an original piece of research in the form of a ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’. Degrees are awarded upon successful defense of the thesis / dissertation. Professional degree programs (JD, MBA, MD, MSW, MPA, etc.): These programs often include a set of ‘required courses’ or ‘core classes’ and ‘electives’ closely-related to the field of study. Degrees are awarded upon satisfactory completion of these courses.

US Graduate Curriculum: Academic/research degree programs (Master’s, PhD) (EAS, 1999): These programs typically begin with a significant classroom-based component (required classes and possibly electives). Following the completion of ‘comprehensive exams’ on class content, students may progress to ‘doctoral candidacy’. An academic/research Master’s or PhD will also include a significant research component, as well as completion and publication of an original piece of research in the form of a ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’. Degrees are awarded upon successful defense of the thesis / dissertation. Professional degree programs (JD, MBA, MD, MSW, MPA, etc.): These programs often include a set of ‘required courses’ or ‘core classes’ and ‘electives’ closely-related to the field of study. Degrees are awarded upon satisfactory completion of these courses.

US Graduate Assessment: Generally, classes will be continually assessed in the same manner as the undergraduate level, resulting in a cumulative ‘GPA’ (EAS, 1999). However, some programs use a high pass/pass/fail grading system Academic/research degree programs: The ‘comprehensive exams’ and ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ component will be assessed by a faculty committee. Ideally, the student’s advisor and/or faculty committee will provide feedback on the ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ proposal, as well as guidance throughout the research and writing process. This culminates in a submission of the written ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ to the committee and an ‘oral defense’. Feedback is once again provided, and upon successful defense, the student will submit a final, revised version of the written work. The student may also submit written work to journals or industry publications, which will be peer-reviewed by members of the student’s field.

US Graduate Assessment: Generally, classes will be continually assessed in the same manner as the undergraduate level, resulting in a cumulative ‘GPA’ (EAS, 1999). However, some programs use a high pass/pass/fail grading system Academic/research degree programs: The ‘comprehensive exams’ and ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ component will be assessed by a faculty committee. Ideally, the student’s advisor and/or faculty committee will provide feedback on the ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ proposal, as well as guidance throughout the research and writing process. This culminates in a submission of the written ‘thesis’ / ‘dissertation’ to the committee and an ‘oral defense’. Feedback is once again provided, and upon successful defense, the student will submit a final, revised version of the written work. The student may also submit written work to journals or industry publications, which will be peer-reviewed by members of the student’s field.

US Graduate Admissions: At the graduate level, US students apply to each university individually again. However, for law and medicine, students apply through a centralised online application portal (LSAC and AAMC respectively) (EAS, 1999). However, admissions decisions are more often made by the department in which the student plans to study based upon evaluation of a package containing: the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular and professional experience a personal statement 2-3 letters of recommendation by university or work referees admissions exam results (GRE, GMAT, MCAT or LSAT) a transcript of postsecondary grades. admissions fee, often ranging from $50-100 per university Admissions decisions generally take into account a wide range of factors: a student’s academic record at the postsecondary level, extracurricular involvement, work experience, research experience, character, interest in attending the specific university or studying a particular field, etc.

US Graduate Admissions: At the graduate level, US students apply to each university individually again. However, for law and medicine, students apply through a centralised online application portal (LSAC and AAMC respectively) (EAS, 1999). However, admissions decisions are more often made by the department in which the student plans to study based upon evaluation of a package containing: the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular and professional experience a personal statement 2-3 letters of recommendation by university or work referees admissions exam results (GRE, GMAT, MCAT or LSAT) a transcript of postsecondary grades. admissions fee, often ranging from $50-100 per university Admissions decisions generally take into account a wide range of factors: a student’s academic record at the postsecondary level, extracurricular involvement, work experience, research experience, character, interest in attending the specific university or studying a particular field, etc.

US Higher Ed. Funding: In 2006, the US government spent $24,074 per student and 2.9% of its GDP on postsecondary education (NCES, 2007a). Universities receive funding from state government appropriations (more important for public institutions), the federal government (student aid, research grants, appropriations), private donors, interest on endowments (more important for private institutions), student tuition and fees, private organisations (research grants), etc. (NCES, 2007c) Financial aid: The average undergraduate cost of attendance for student living on-campus was $26,626 at private non-profit institutions, $20,328 for out-of-state students at public institutions and $13,455 for in-state students at public institutions (NCES, 2006c). Average tuition charges rose 30% at four-year, private non-profit institutions, 35% for out-of-state students at public institutions and 41% for in-state students at public institutions. At the undergraduate level, 50.7% of students receive grants, 35.2 take out loans and 12% use work study positions to fund their studies (NCES, 2005c). The average graduate tuition was $11,621 in 2003/04 (NCES, 2006a). At the graduate level, funding is often available through the US university in the form or research and teaching assistantships (25.9% Master’s students receiving aid, 53.2% doctoral and 15.1% first-professional degree), loans (57.9%, 37.6%, 84.6%) and grants (39.9%, 64.7%, 39.7%) (NCES, 2006b). At both the undergraduate and graduate level, student financial need is determined through the FAFSA process (Federal, 2007). US citizens may take out a government loan, generally at a maximum amount determined through FAFSA (the cost of attendance minus the estimated family contribution figure). Depending upon financial need, students may be eligible to receive a non-repayable Pell Grant at a maximum of $4,130 in 2007/08 or a subsidised government loan, meaning the student will not accrue interest on the loan during study. Students typically start payment on government loans within 6-9 months of graduation. Federal ‘work study programs’ and private loans are also a source of funding for students.

US Higher Ed. Funding: In 2006, the US government spent $24,074 per student and 2.9% of its GDP on postsecondary education (NCES, 2007a). Universities receive funding from state government appropriations (more important for public institutions), the federal government (student aid, research grants, appropriations), private donors, interest on endowments (more important for private institutions), student tuition and fees, private organisations (research grants), etc. (NCES, 2007c) Financial aid: The average undergraduate cost of attendance for student living on-campus was $26,626 at private non-profit institutions, $20,328 for out-of-state students at public institutions and $13,455 for in-state students at public institutions (NCES, 2006c). Average tuition charges rose 30% at four-year, private non-profit institutions, 35% for out-of-state students at public institutions and 41% for in-state students at public institutions. At the undergraduate level, 50.7% of students receive grants, 35.2 take out loans and 12% use work study positions to fund their studies (NCES, 2005c). The average graduate tuition was $11,621 in 2003/04 (NCES, 2006a). At the graduate level, funding is often available through the US university in the form or research and teaching assistantships (25.9% Master’s students receiving aid, 53.2% doctoral and 15.1% first-professional degree), loans (57.9%, 37.6%, 84.6%) and grants (39.9%, 64.7%, 39.7%) (NCES, 2006b). At both the undergraduate and graduate level, student financial need is determined through the FAFSA process (Federal, 2007). US citizens may take out a government loan, generally at a maximum amount determined through FAFSA (the cost of attendance minus the estimated family contribution figure). Depending upon financial need, students may be eligible to receive a non-repayable Pell Grant at a maximum of $4,130 in 2007/08 or a subsidised government loan, meaning the student will not accrue interest on the loan during study. Students typically start payment on government loans within 6-9 months of graduation. Federal ‘work study programs’ and private loans are also a source of funding for students.

UK Undergraduate Curriculum: Bachelor’s degrees (BA, BSc) are generally awarded on the satisfactory completion of three years of full-time study in a subject (Directgov, 2007). Some ‘courses’ require a year abroad or practical training and are four years in length. Courses typically require students to complete ‘core modules’ within the department. Some courses also have a ‘thesis’ requirement in the final year. Some flexibility in the course structure may be afforded through ‘elective modules’ typically taken within the department or ‘joint honours’ degrees, by which a student completes half of the required modules for two courses. Note medicine (MB) and law may be studied at the undergraduate level. Medicine is a five- to six-year course. Law is a three-year course. Due to the nature of study (ie almost solely within one’s department), transferring departments or universities can mean starting over (B. Costello, personal communication, July 24, 2007).

UK Undergraduate Curriculum: Bachelor’s degrees (BA, BSc) are generally awarded on the satisfactory completion of three years of full-time study in a subject (Directgov, 2007). Some ‘courses’ require a year abroad or practical training and are four years in length. Courses typically require students to complete ‘core modules’ within the department. Some courses also have a ‘thesis’ requirement in the final year. Some flexibility in the course structure may be afforded through ‘elective modules’ typically taken within the department or ‘joint honours’ degrees, by which a student completes half of the required modules for two courses. Note medicine (MB) and law may be studied at the undergraduate level. Medicine is a five- to six-year course. Law is a three-year course. Due to the nature of study (ie almost solely within one’s department), transferring departments or universities can mean starting over (B. Costello, personal communication, July 24, 2007).

UK Undergraduate Assessment: Students are not continually assessed as in the US. Rather, papers are generally completed at the end of each module and assessed by faculty members (M. Osbourn, personal communication, October 20, 2007). Students receive a ‘mark’ (expressed in a percentage) for each module, which is taken into account in determining the student’s final ‘degree results’. Modules taken in the first year often do not count toward the student’s degree results. Assessment frameworks, assessment processes and the manner in which marks are translated into final degree results are determined by the academic department. Example of assessment in a UK undergraduate humanities degree: In the Modern Languages department at the University of Oxford, students are assessed through oral examinations, 12 papers and an extended essay completed primarily in the final year of study (Modern, 2007). Papers and the extended essay are assessed independently by two graders using a department framework and then read by a third reader if necessary (Modern, 2006). Final ‘degree results’ are expressed in terms of: ‘1:1 - First class honours’, ‘2:1 - Upper-second class honours’, ‘2:2 - Lower-second class honours’, ‘2:3 – Third’, ‘Pass’ and/or ‘Fail’ (Directgov, 2007).

UK Undergraduate Assessment: Students are not continually assessed as in the US. Rather, papers are generally completed at the end of each module and assessed by faculty members (M. Osbourn, personal communication, October 20, 2007). Students receive a ‘mark’ (expressed in a percentage) for each module, which is taken into account in determining the student’s final ‘degree results’. Modules taken in the first year often do not count toward the student’s degree results. Assessment frameworks, assessment processes and the manner in which marks are translated into final degree results are determined by the academic department. Example of assessment in a UK undergraduate humanities degree: In the Modern Languages department at the University of Oxford, students are assessed through oral examinations, 12 papers and an extended essay completed primarily in the final year of study (Modern, 2007). Papers and the extended essay are assessed independently by two graders using a department framework and then read by a third reader if necessary (Modern, 2006). Final ‘degree results’ are expressed in terms of: ‘1:1 - First class honours’, ‘2:1 - Upper-second class honours’, ‘2:2 - Lower-second class honours’, ‘2:3 – Third’, ‘Pass’ and/or ‘Fail’ (Directgov, 2007).

UK Undergraduate Admissions: At the undergraduate level, UK students apply to a maximum of five universities through a centralised application portal, ‘UCAS’ - Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS, 2007). Students may apply to either Oxford or Cambridge, but not both. Students apply to the ‘course’, rather than to the university at large. Admissions decisions are made by ‘admissions tutors’ within the academic department upon evaluation of a package containing: a 47-line personal statement one letter of recommendation from a school representative GCSE, AS-level and predicted A-level results or other relevant qualifications application fee £5-15 Admissions decisions generally centre upon the student’s academic record and potential (P. Edge, personal communication, 2007). Students may be interviewed as part of the admissions process, either as a mandatory component of the admissions process or for borderline applicants. Students submit applications prior to receiving final A-level results (European Commission, 2007). Students are generally given a ‘conditional offer’ of admission, upon earning stated A Level results in the summer before university begins. If students do not earn these results, they must re-apply for remaining spaces at other universities through the ‘clearing process’ (Directgov, 2007).

UK Undergraduate Admissions: At the undergraduate level, UK students apply to a maximum of five universities through a centralised application portal, ‘UCAS’ - Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS, 2007). Students may apply to either Oxford or Cambridge, but not both. Students apply to the ‘course’, rather than to the university at large. Admissions decisions are made by ‘admissions tutors’ within the academic department upon evaluation of a package containing: a 47-line personal statement one letter of recommendation from a school representative GCSE, AS-level and predicted A-level results or other relevant qualifications application fee £5-15 Admissions decisions generally centre upon the student’s academic record and potential (P. Edge, personal communication, 2007). Students may be interviewed as part of the admissions process, either as a mandatory component of the admissions process or for borderline applicants. Students submit applications prior to receiving final A-level results (European Commission, 2007). Students are generally given a ‘conditional offer’ of admission, upon earning stated A Level results in the summer before university begins. If students do not earn these results, they must re-apply for remaining spaces at other universities through the ‘clearing process’ (Directgov, 2007).

UK Postgraduate Curriculum: There are four types of postgraduate degrees (Directgov, 2007) ‘Postgraduate certificates’ and ‘postgraduate diplomas’ are generally 9-12 months in length and more vocational in nature. Master’s degrees (MA, MSc, LLM, MBA, MEd, MRes, MPhil, etc.) are generally one or two years in length and are divided into two categories. A ‘taught Master’s course’ (MSc, MA, MBA, MEd, LLM) includes significant classroom-based instruction. A ‘research Master’s course’ (MRes, MPhil) includes research training and prepares students for doctoral study. Both types of degrees generally require completion of a 10,000-15,000 word thesis. Doctoral degrees (DPhil, PhD) are typically three years in length and are driven primarily by students’ independent research, though students will often be asked to attend seminars during the course. At end of the course, students submit a dissertation. Professional training for many fields occurs through certificate programmes or ‘graduate training schemes’, through which a recent graduate is hired by a company and then completes its professional training and assessment programme (G. P. Pearce, personal communication, November 1, 2007). Due to the existence of such programmes, one does not have to study a particular field at the undergraduate level in order to enter the field.

UK Postgraduate Curriculum: There are four types of postgraduate degrees (Directgov, 2007) ‘Postgraduate certificates’ and ‘postgraduate diplomas’ are generally 9-12 months in length and more vocational in nature. Master’s degrees (MA, MSc, LLM, MBA, MEd, MRes, MPhil, etc.) are generally one or two years in length and are divided into two categories. A ‘taught Master’s course’ (MSc, MA, MBA, MEd, LLM) includes significant classroom-based instruction. A ‘research Master’s course’ (MRes, MPhil) includes research training and prepares students for doctoral study. Both types of degrees generally require completion of a 10,000-15,000 word thesis. Doctoral degrees (DPhil, PhD) are typically three years in length and are driven primarily by students’ independent research, though students will often be asked to attend seminars during the course. At end of the course, students submit a dissertation. Professional training for many fields occurs through certificate programmes or ‘graduate training schemes’, through which a recent graduate is hired by a company and then completes its professional training and assessment programme (G. P. Pearce, personal communication, November 1, 2007). Due to the existence of such programmes, one does not have to study a particular field at the undergraduate level in order to enter the field.

UK Postgraduate Assessment: Students are not continually assessed as in the US (E. E. Frey, personal communication, November 13, 2007). Rather, for ‘taught Master’s courses’, essays and/or exams are completed at the end of each module and assessed by faculty, and the dissertation/thesis is assessed by faculty upon completion. For ‘research Master’s courses’, the thesis/dissertation is assessed by faculty upon completion. For doctoral courses, often a student will be registered in a research Master’s course in the first instance. Upon successful completion of work in the first or second year, the student will be registered in the doctoral course. Results for Master’s courses are classified as (Directgov, 2007): ‘Distinction’ ‘Merit’ (for some but not all courses) ‘Pass’ ‘Fail’ Results for doctoral courses are classified as: ‘Pass’ ‘Fail’

UK Postgraduate Assessment: Students are not continually assessed as in the US (E. E. Frey, personal communication, November 13, 2007). Rather, for ‘taught Master’s courses’, essays and/or exams are completed at the end of each module and assessed by faculty, and the dissertation/thesis is assessed by faculty upon completion. For ‘research Master’s courses’, the thesis/dissertation is assessed by faculty upon completion. For doctoral courses, often a student will be registered in a research Master’s course in the first instance. Upon successful completion of work in the first or second year, the student will be registered in the doctoral course. Results for Master’s courses are classified as (Directgov, 2007): ‘Distinction’ ‘Merit’ (for some but not all courses) ‘Pass’ ‘Fail’ Results for doctoral courses are classified as: ‘Pass’ ‘Fail’

UK Postgraduate Admissions: At the postgraduate level, UK students apply to each university individually (European Commission, 2007). However, a ‘UKPASS’ centralised application service will be available in 2007. Admissions decisions are made by the department in which the student plans to study based upon evaluation of a package containing (E. E. Frey, personal communication, November 13, 2007): the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular and professional experience a personal statement / research proposal 2-3 letters of recommendation by university or work referees a transcript of postsecondary grades an application fee Admissions decisions generally centre upon the student’s academic record and potential. Generally, applicants must have at least a ‘2:2 - lower-second class honours’ at the undergraduate level (Directgov, 2007).

UK Postgraduate Admissions: At the postgraduate level, UK students apply to each university individually (European Commission, 2007). However, a ‘UKPASS’ centralised application service will be available in 2007. Admissions decisions are made by the department in which the student plans to study based upon evaluation of a package containing (E. E. Frey, personal communication, November 13, 2007): the application form a summary of the student’s extracurricular and professional experience a personal statement / research proposal 2-3 letters of recommendation by university or work referees a transcript of postsecondary grades an application fee Admissions decisions generally centre upon the student’s academic record and potential. Generally, applicants must have at least a ‘2:2 - lower-second class honours’ at the undergraduate level (Directgov, 2007).

UK Higher Ed. Funding: In 2003, the UK government spent ~9,100 euros / student (European Commission, 2007). ~75% of which is distributed directly to the educational institutions ~25% of which is financial assistance to students In 2003, the UK government spent 1.14% of its GDP on postsecondary education. UK universities receive funding from the government (~38%), fees from undergraduates (9%), research grants (16%), services (18%) and income on endowments / investments (2%) (Universities UK, 2007c). As of 1997-98, UK students pay fees to attend university. Fees are set by individual institutions or departments, but are limited by a feecap set by the UK government. The maximum fee for 2008/09 is £3,145 pounds, a 2.4% increase from the £3,070 maximum fee for 2007/08 (Directgov). Most universities set their tuition rates at the maximum amount (Reddin, 2007). The government-imposed tuition cap may be lifted or may end as early as 2010, allowing universities to set their own rates (BBC, 2007). Meanwhile, some university officials from the ‘Russell Group’, a consortium of 20 research-intensive UK universities, have expressed a desire to double if not triple the present tuition rates.

UK Higher Ed. Funding: In 2003, the UK government spent ~9,100 euros / student (European Commission, 2007). ~75% of which is distributed directly to the educational institutions ~25% of which is financial assistance to students In 2003, the UK government spent 1.14% of its GDP on postsecondary education. UK universities receive funding from the government (~38%), fees from undergraduates (9%), research grants (16%), services (18%) and income on endowments / investments (2%) (Universities UK, 2007c). As of 1997-98, UK students pay fees to attend university. Fees are set by individual institutions or departments, but are limited by a feecap set by the UK government. The maximum fee for 2008/09 is £3,145 pounds, a 2.4% increase from the £3,070 maximum fee for 2007/08 (Directgov). Most universities set their tuition rates at the maximum amount (Reddin, 2007). The government-imposed tuition cap may be lifted or may end as early as 2010, allowing universities to set their own rates (BBC, 2007). Meanwhile, some university officials from the ‘Russell Group’, a consortium of 20 research-intensive UK universities, have expressed a desire to double if not triple the present tuition rates.

UK Higher Ed. Funding: Financial aid: The national government offers ‘fee loans’ and ‘maintenance loans’ to all undergraduate students with the maximum loan amount determined by the university fee rate, family income, whether the student lives at home and whether the student is studying in London (Universities UK, 2007b). These government loans are paid back at an interest rate equal to inflation, after the student earns £15,000 per year. Loan payments are automatically deducted from the student’s paycheck at a fixed amount of 9% of the income earned over £15,000. Non-repayable ‘student maintenance grants’ are available for up to £2,765 per year for undergraduates. Grants are ‘means tested’, ie determined on a sliding scale based on family income. Full grants are generally available to families earning £17,910 per year or less, and partial grants are often awarded for families earning between £17,991 and £38,330 per year. Nearly half of all first-year students are eligible for a grant. Universities may offer a limited number of ‘bursaries’ or scholarships. Universities charging the maximum fee rate must provide a non-repayable bursary at a minimum of £305 per year to students receiving the full maintenance grant. Most universities offer other forms of need- and merit-based financial aid, which is distributed by the university. At the postgraduate level, funding is often available through government-funded ‘research councils’ specific to major fields of study (Directgov, 2007). Some research and teaching assistantships are also available from the university, but not on the same scale as the US.

UK Higher Ed. Funding: Financial aid: The national government offers ‘fee loans’ and ‘maintenance loans’ to all undergraduate students with the maximum loan amount determined by the university fee rate, family income, whether the student lives at home and whether the student is studying in London (Universities UK, 2007b). These government loans are paid back at an interest rate equal to inflation, after the student earns £15,000 per year. Loan payments are automatically deducted from the student’s paycheck at a fixed amount of 9% of the income earned over £15,000. Non-repayable ‘student maintenance grants’ are available for up to £2,765 per year for undergraduates. Grants are ‘means tested’, ie determined on a sliding scale based on family income. Full grants are generally available to families earning £17,910 per year or less, and partial grants are often awarded for families earning between £17,991 and £38,330 per year. Nearly half of all first-year students are eligible for a grant. Universities may offer a limited number of ‘bursaries’ or scholarships. Universities charging the maximum fee rate must provide a non-repayable bursary at a minimum of £305 per year to students receiving the full maintenance grant. Most universities offer other forms of need- and merit-based financial aid, which is distributed by the university. At the postgraduate level, funding is often available through government-funded ‘research councils’ specific to major fields of study (Directgov, 2007). Some research and teaching assistantships are also available from the university, but not on the same scale as the US.

UK Governance and Stakeholders: All UK universities but one are ‘government-dependent private institutions’ (European Commission, 2007, 26). The number of university students is determined by the federal government, but universities select their own students (European Commission, 2007) Assessment data on UK universities available from a number of bodies: Research Assessment Exercise for 2001 (and for 2008, forthcoming) (RAE, 2007) The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA, 2007) Teaching Quality Information (TQI, 2007) The Times Good Universities Guide league tables (The Times, 2007) BBC Student Guide (British Council, 2007) Guardian University Guide For accreditation purposes, universities must be recognised by the Department for Children, Schools and Families (Dfes, 2007). A list of recognised universities can be found on the Dfes website. UK universities have recently started hiring development officers and seeking more private funds (jobs.ac.uk, 2007). Additional stakeholders include students and families.

UK Governance and Stakeholders: All UK universities but one are ‘government-dependent private institutions’ (European Commission, 2007, 26). The number of university students is determined by the federal government, but universities select their own students (European Commission, 2007) Assessment data on UK universities available from a number of bodies: Research Assessment Exercise for 2001 (and for 2008, forthcoming) (RAE, 2007) The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA, 2007) Teaching Quality Information (TQI, 2007) The Times Good Universities Guide league tables (The Times, 2007) BBC Student Guide (British Council, 2007) Guardian University Guide For accreditation purposes, universities must be recognised by the Department for Children, Schools and Families (Dfes, 2007). A list of recognised universities can be found on the Dfes website. UK universities have recently started hiring development officers and seeking more private funds (jobs.ac.uk, 2007). Additional stakeholders include students and families.

Key Similarities and Differences: Given the historical roots of the US higher education system in Oxbridge, the US and UK systems retain similar structures of undergraduate and postgraduate study (Altbach, 2005). However, the influence of the German system on the US in the late 1800s can be seen in the level of academic freedom and importance of research as a function of the university. The US higher education system maintains greater autonomy from government influences relative to the UK (Bok, 1986). The autonomy of US institutions from the government has resulted in greater institutional diversity and a higher level of competition between institutions, relative to the UK. However, when the cap on UK tuition and fees ends in 2010, diversity at least in terms of cost and prestige may develop in the UK, as less prestigious UK institutions may compete for students by offering lower tuition rates. This government autonomy in the US also results in a decentralised undergraduate application process, university accreditation processes and decisions regarding cost of attendance, leading to a less transparent and more complicated admissions process for students and parents.

Key Similarities and Differences: Given the historical roots of the US higher education system in Oxbridge, the US and UK systems retain similar structures of undergraduate and postgraduate study (Altbach, 2005). However, the influence of the German system on the US in the late 1800s can be seen in the level of academic freedom and importance of research as a function of the university. The US higher education system maintains greater autonomy from government influences relative to the UK (Bok, 1986). The autonomy of US institutions from the government has resulted in greater institutional diversity and a higher level of competition between institutions, relative to the UK. However, when the cap on UK tuition and fees ends in 2010, diversity at least in terms of cost and prestige may develop in the UK, as less prestigious UK institutions may compete for students by offering lower tuition rates. This government autonomy in the US also results in a decentralised undergraduate application process, university accreditation processes and decisions regarding cost of attendance, leading to a less transparent and more complicated admissions process for students and parents.

Key Similarities and Differences: US faculty and teachers also maintain a high level of autonomy within the university and secondary school system, as reflected in the decentralised methods of assessment and decisions about course content. In the absence of a national curriculum, US students also gain more independence (and responsibility) for shaping their secondary and postsecondary educational experiences. US institutions have more stakeholders than UK institutions, and US universities tend to also be more responsive to these stakeholders and other external forces such as students, parents, corporate entities, market competition, etc. Further, US institutions are more competitive than UK institutions in terms of funding, students, faculty, etc. However, with the introduction of university fees in the UK and increase in development activities, the notion of institutional competition and the ‘student as consumer’ will likely evolve into a more US model. The number of bachelor’s degree holders in age brackets over 30 suggests access to higher education in the US has been greater than the UK (NCES, 2005b; European Commission, 2007). However, this has changed in recent years with similar percentages of UK and US students under age 30 attending postsecondary education. The participation in postsecondary education in the UK has risen dramatically over the last 50 years, from 5% in 1956 to approximately 30% presently (Universities UK, 2007a).

Key Similarities and Differences: US faculty and teachers also maintain a high level of autonomy within the university and secondary school system, as reflected in the decentralised methods of assessment and decisions about course content. In the absence of a national curriculum, US students also gain more independence (and responsibility) for shaping their secondary and postsecondary educational experiences. US institutions have more stakeholders than UK institutions, and US universities tend to also be more responsive to these stakeholders and other external forces such as students, parents, corporate entities, market competition, etc. Further, US institutions are more competitive than UK institutions in terms of funding, students, faculty, etc. However, with the introduction of university fees in the UK and increase in development activities, the notion of institutional competition and the ‘student as consumer’ will likely evolve into a more US model. The number of bachelor’s degree holders in age brackets over 30 suggests access to higher education in the US has been greater than the UK (NCES, 2005b; European Commission, 2007). However, this has changed in recent years with similar percentages of UK and US students under age 30 attending postsecondary education. The participation in postsecondary education in the UK has risen dramatically over the last 50 years, from 5% in 1956 to approximately 30% presently (Universities UK, 2007a).

Implications for Advising UK Students: In advising UK students, it is particularly important to take into account issues related to differences in the US and UK educational systems: Differences in US and UK terminology Terms UK students may not be familiar with Several commonly-held misconceptions Though not explicitly related to educational differences, it is important to take into account the following cultural and communication issues when advising UK students: National terminology Diversity Language differences Cultural and communication style differences

Implications for Advising UK Students: In advising UK students, it is particularly important to take into account issues related to differences in the US and UK educational systems: Differences in US and UK terminology Terms UK students may not be familiar with Several commonly-held misconceptions Though not explicitly related to educational differences, it is important to take into account the following cultural and communication issues when advising UK students: National terminology Diversity Language differences Cultural and communication style differences

US and UK Terminology: ‘School’ is used in the US to describe a place of study at any level. -- In the UK, a ‘school’ is a place of study at the primary or secondary level. ‘College’ is used in the US to describe a place of postsecondary study. -- In the UK, a ‘college’ is place of secondary education. ‘University’ is used in the US interchangeably with ‘college’. -- In the UK, ‘college’ and ‘university’ may not be used interchangeably. ‘Course’ is used in the US to describe a unit of a degree. -- In the UK, a ‘course’ is a full degree. ‘Module’ is the term for an individual unit of a degree at postsecondary level in the UK. ‘Grade’ is used in the US to describe a student’s level in school and result of student assessment. -- In the UK, ‘years’ refer to levels in school. ‘Results’ or ‘marks’ refer to student assessment.

US and UK Terminology: ‘School’ is used in the US to describe a place of study at any level. -- In the UK, a ‘school’ is a place of study at the primary or secondary level. ‘College’ is used in the US to describe a place of postsecondary study. -- In the UK, a ‘college’ is place of secondary education. ‘University’ is used in the US interchangeably with ‘college’. -- In the UK, ‘college’ and ‘university’ may not be used interchangeably. ‘Course’ is used in the US to describe a unit of a degree. -- In the UK, a ‘course’ is a full degree. ‘Module’ is the term for an individual unit of a degree at postsecondary level in the UK. ‘Grade’ is used in the US to describe a student’s level in school and result of student assessment. -- In the UK, ‘years’ refer to levels in school. ‘Results’ or ‘marks’ refer to student assessment.

Terms Students May Not Be Familiar With: ‘Freshman’, ‘Sophomore’, ‘Junior’ and ‘Senior’ years of US high school are the equivalent of ‘Years 10 – 13’ in the UK. ‘Undergraduate’ / ‘graduate degrees’ in the US are the equivalent of ‘first degrees’ or ‘Bachelor’s degrees’ / ‘postgraduate degrees’ in the UK. There is no direct equivalent for ‘credit hours’ in US universities, as UK degrees are expressed in time lengths rather than credit hours to be completed. ‘Required courses’ and ‘electives’ in the US are similar to ‘core modules and ‘elective modules’ in the UK. A ‘double major’ in the US is similar to ‘joint honours’ in the UK, though US students complete the curricular requirements for both degrees rather than half the requirements for joint hounours degrees There is no direct equivalent of a ‘minor’ in the US, as students specialise in a particular subject at the undergraduate level.

Terms Students May Not Be Familiar With: ‘Freshman’, ‘Sophomore’, ‘Junior’ and ‘Senior’ years of US high school are the equivalent of ‘Years 10 – 13’ in the UK. ‘Undergraduate’ / ‘graduate degrees’ in the US are the equivalent of ‘first degrees’ or ‘Bachelor’s degrees’ / ‘postgraduate degrees’ in the UK. There is no direct equivalent for ‘credit hours’ in US universities, as UK degrees are expressed in time lengths rather than credit hours to be completed. ‘Required courses’ and ‘electives’ in the US are similar to ‘core modules and ‘elective modules’ in the UK. A ‘double major’ in the US is similar to ‘joint honours’ in the UK, though US students complete the curricular requirements for both degrees rather than half the requirements for joint hounours degrees There is no direct equivalent of a ‘minor’ in the US, as students specialise in a particular subject at the undergraduate level.

Common Misconceptions: ‘The UK educational system is just as good as the US system and less expensive. Why should I study in the US’? As tuition rates continue to rise in the UK, the appeal and affordability of US universities will likely increase for British students. UK students commonly cite the following reasons for studying at the undergraduate level in the US: the breadth, number, quality and diversity of US universities, the flexibility of courses / degree programmes, the liberal arts philosophy, the opportunity for cultural exchange and improved job prospects. At the postgraduate level, students also cite the opportunity to conduct research with or study under a particular faculty member, as well as the increased opportunities to gain funding, contacts and professional experience whilst studying through assistantships. Advising strategy: Talk through the benefits of studying in the US with prospective students, respecting the quality and merits of both the US and UK educational systems.

Common Misconceptions: ‘The UK educational system is just as good as the US system and less expensive. Why should I study in the US’? As tuition rates continue to rise in the UK, the appeal and affordability of US universities will likely increase for British students. UK students commonly cite the following reasons for studying at the undergraduate level in the US: the breadth, number, quality and diversity of US universities, the flexibility of courses / degree programmes, the liberal arts philosophy, the opportunity for cultural exchange and improved job prospects. At the postgraduate level, students also cite the opportunity to conduct research with or study under a particular faculty member, as well as the increased opportunities to gain funding, contacts and professional experience whilst studying through assistantships. Advising strategy: Talk through the benefits of studying in the US with prospective students, respecting the quality and merits of both the US and UK educational systems.

Common Misconceptions: ‘Where can I find official rankings of US universities’? Through league tables, RAE and other forms of assessment discussed in previous slides, relatively unbiased and transparent rankings of UK schools and university departments are available. Therefore, comparisons between institutions may be made easily by prospective students and parents. UK students and parents may expect to find a similar set of rankings for the US. Yet, in the US, accreditation is handled by regional accreditation bodies, and standardised, government rankings of universities do not exist. Unofficial rankings of US universities such as US News and World Reports are available. Students and parents should be encouraged to read the fine print on how rankings of US universities are calculated. Rankings may provide a rough indication of the relative prestige of universities. Note that commercial interests may influence which universities are profiled or highlighted in ‘university guide’ publications.

Common Misconceptions: ‘Where can I find official rankings of US universities’? Through league tables, RAE and other forms of assessment discussed in previous slides, relatively unbiased and transparent rankings of UK schools and university departments are available. Therefore, comparisons between institutions may be made easily by prospective students and parents. UK students and parents may expect to find a similar set of rankings for the US. Yet, in the US, accreditation is handled by regional accreditation bodies, and standardised, government rankings of universities do not exist. Unofficial rankings of US universities such as US News and World Reports are available. Students and parents should be encouraged to read the fine print on how rankings of US universities are calculated. Rankings may provide a rough indication of the relative prestige of universities. Note that commercial interests may influence which universities are profiled or highlighted in ‘university guide’ publications.

National Terminology: Keep in mind that each nation of the UK has its own history, national symbols, cultural norms, football/rugby teams, dialects and ancestral language. ‘UK’ is an abbreviation for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. ‘Great Britain’ and ‘Britain’ refer to the island comprising England, Wales and Scotland which is inhabited by British people. The ‘Republic of Ireland’ is a separate country on the Island of Eire. The ‘Republic of Ireland’ is located on the same island as ‘Northern Ireland’, but is not part of the UK. Sources for cultural notes: (Morrison, Conaway, & Borden, 1994; Norbury, 2003)

National Terminology: Keep in mind that each nation of the UK has its own history, national symbols, cultural norms, football/rugby teams, dialects and ancestral language. ‘UK’ is an abbreviation for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. ‘Great Britain’ and ‘Britain’ refer to the island comprising England, Wales and Scotland which is inhabited by British people. The ‘Republic of Ireland’ is a separate country on the Island of Eire. The ‘Republic of Ireland’ is located on the same island as ‘Northern Ireland’, but is not part of the UK. Sources for cultural notes: (Morrison, Conaway, & Borden, 1994; Norbury, 2003)

Language Differences: British English is rather different from American English in terms of grammar, punctuation and vocabulary.

Language Differences: British English is rather different from American English in terms of grammar, punctuation and vocabulary.