4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 161

Unit 3 Chemical Reactions

Unit 3 Chemical Reactions

Menu • • • The Chemical Industry Hess’s Law Equilibrium Acids and Bases Redox Reactions Nuclear Chemistry

Menu • • • The Chemical Industry Hess’s Law Equilibrium Acids and Bases Redox Reactions Nuclear Chemistry

The Chemical Industry

The Chemical Industry

The Chemical Industry Major contributor to quality of life and economy.

The Chemical Industry Major contributor to quality of life and economy.

The Chemical Industry • Quality of life • Fuels (eg petrol for cars) • Plastics (Polythene etc) • Agrochemicals (Fertilisers, pesticides etc) • Alloys (Inc. Steel for building) • Chemicals (eg Cl 2 for water purification) • Dyes (for clothing etc) • Cosmetics and medicines • Soaps and detergents • Etc!!!!

The Chemical Industry • Quality of life • Fuels (eg petrol for cars) • Plastics (Polythene etc) • Agrochemicals (Fertilisers, pesticides etc) • Alloys (Inc. Steel for building) • Chemicals (eg Cl 2 for water purification) • Dyes (for clothing etc) • Cosmetics and medicines • Soaps and detergents • Etc!!!!

The Chemical Industry • Contributes to National Economy • Major employer of people at all skill levels • Revenue from taxation on fuels etc • Revenue from sales of product • Revenue from exports of products

The Chemical Industry • Contributes to National Economy • Major employer of people at all skill levels • Revenue from taxation on fuels etc • Revenue from sales of product • Revenue from exports of products

The Chemical Industry • Research chemists identify a chemical route to make a new product, using available reactants.

The Chemical Industry • Research chemists identify a chemical route to make a new product, using available reactants.

The Chemical Industry • Feasibility study produces small amounts of product – to see if the process will work

The Chemical Industry • Feasibility study produces small amounts of product – to see if the process will work

The Chemical Industry • The process is now scaled up to go into full scale production. • Process so far will have taken months. • Many problems will have been encountered and will have to be resolved before full scale production commences

The Chemical Industry • The process is now scaled up to go into full scale production. • Process so far will have taken months. • Many problems will have been encountered and will have to be resolved before full scale production commences

The Chemical Industry • Chemical plant is built in a suitable site • Operators employed • Early production will allow monitoring of cost, safety, pollution risks, yield and profitability

The Chemical Industry • Chemical plant is built in a suitable site • Operators employed • Early production will allow monitoring of cost, safety, pollution risks, yield and profitability

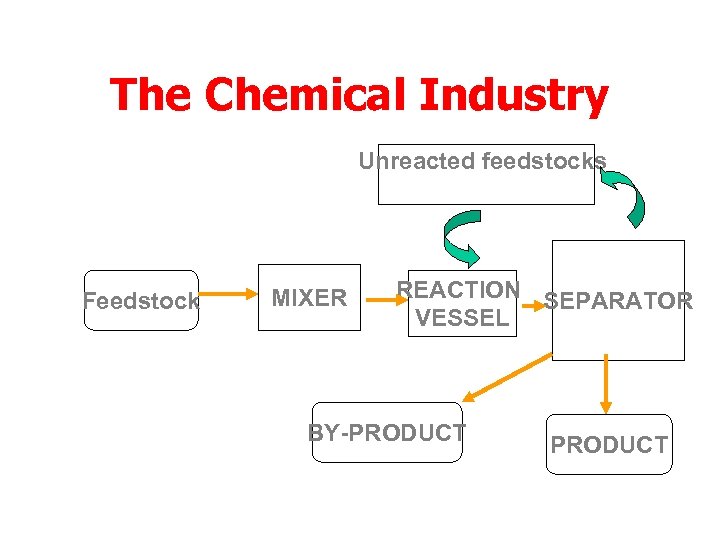

The Chemical Industry Unreacted feedstocks recycled Feedstock MIXER REACTION SEPARATOR VESSEL BY-PRODUCT

The Chemical Industry Unreacted feedstocks recycled Feedstock MIXER REACTION SEPARATOR VESSEL BY-PRODUCT

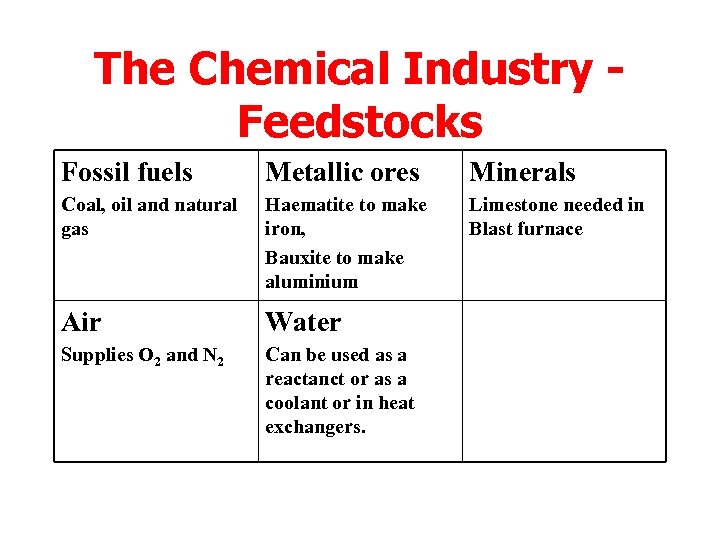

The Chemical Industry Feedstocks Fossil fuels Metallic ores Minerals Coal, oil and natural gas Haematite to make iron, Bauxite to make aluminium Limestone needed in Blast furnace Air Water Supplies O 2 and N 2 Can be used as a reactanct or as a coolant or in heat exchangers.

The Chemical Industry Feedstocks Fossil fuels Metallic ores Minerals Coal, oil and natural gas Haematite to make iron, Bauxite to make aluminium Limestone needed in Blast furnace Air Water Supplies O 2 and N 2 Can be used as a reactanct or as a coolant or in heat exchangers.

The Chemical Industry • Can be Continuous process • Or can be Batch Process

The Chemical Industry • Can be Continuous process • Or can be Batch Process

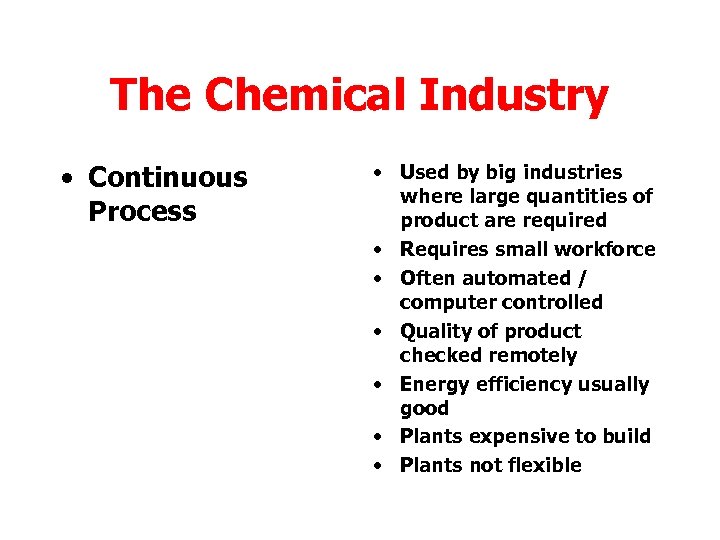

The Chemical Industry • Continuous Process • Used by big industries where large quantities of product are required • Requires small workforce • Often automated / computer controlled • Quality of product checked remotely • Energy efficiency usually good • Plants expensive to build • Plants not flexible

The Chemical Industry • Continuous Process • Used by big industries where large quantities of product are required • Requires small workforce • Often automated / computer controlled • Quality of product checked remotely • Energy efficiency usually good • Plants expensive to build • Plants not flexible

The Chemical Industry • Batch Process • Make substance which are required in smaller amounts • Process looks more like the initial reaction • Overhaul of system needed regularly – time and energy lost if plant has to be shut down • Plant can be more flexible • Plant is usually less expensive to build initially

The Chemical Industry • Batch Process • Make substance which are required in smaller amounts • Process looks more like the initial reaction • Overhaul of system needed regularly – time and energy lost if plant has to be shut down • Plant can be more flexible • Plant is usually less expensive to build initially

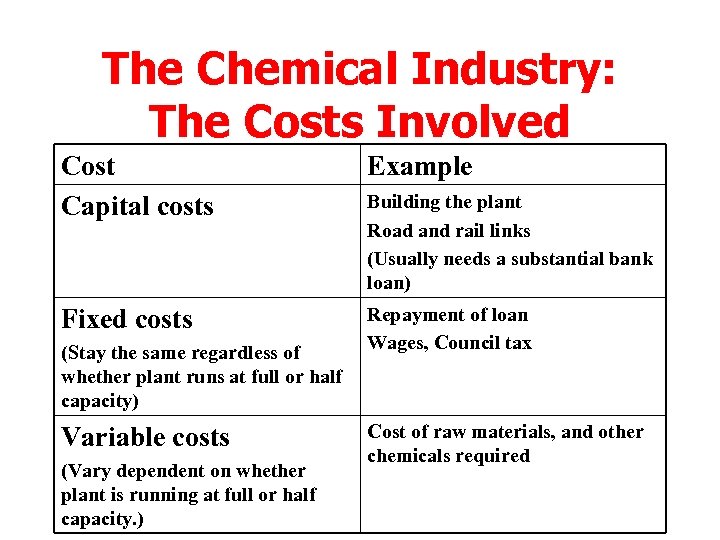

The Chemical Industry: The Costs Involved Cost Capital costs Example Fixed costs Repayment of loan Wages, Council tax (Stay the same regardless of whether plant runs at full or half capacity) Variable costs (Vary dependent on whether plant is running at full or half capacity. ) Building the plant Road and rail links (Usually needs a substantial bank loan) Cost of raw materials, and other chemicals required

The Chemical Industry: The Costs Involved Cost Capital costs Example Fixed costs Repayment of loan Wages, Council tax (Stay the same regardless of whether plant runs at full or half capacity) Variable costs (Vary dependent on whether plant is running at full or half capacity. ) Building the plant Road and rail links (Usually needs a substantial bank loan) Cost of raw materials, and other chemicals required

The Chemical Industry Industries can be classed as: • Labour intensive • Capital intensive

The Chemical Industry Industries can be classed as: • Labour intensive • Capital intensive

The Chemical Industry • Service industries (Catering, education, healthcare), are labour intensive

The Chemical Industry • Service industries (Catering, education, healthcare), are labour intensive

The Chemical Industry • Chemical industry tends to be more Capital intensive as a large investment is required to buy equipment and build plants

The Chemical Industry • Chemical industry tends to be more Capital intensive as a large investment is required to buy equipment and build plants

The Chemical Industry • Expectations of work safety and a clean environment increase during the twentieth century • H & S legislation protects workforce

The Chemical Industry • Expectations of work safety and a clean environment increase during the twentieth century • H & S legislation protects workforce

The Chemical Industry • Tradition is important – steel making continues in areas where it was set up even if raw materials are no longer available locally • Transport options are important

The Chemical Industry • Tradition is important – steel making continues in areas where it was set up even if raw materials are no longer available locally • Transport options are important

The Chemical Industry Choice of a particular chemical route is dependent upon: • • • Cost of raw materials Suitability of feedstocks Yield of product Option to recycle unreacted feedstock Marketability of by products Costs of getting rid of wastes, and safety considerations for workforce and locals • Prevention of pollution

The Chemical Industry Choice of a particular chemical route is dependent upon: • • • Cost of raw materials Suitability of feedstocks Yield of product Option to recycle unreacted feedstock Marketability of by products Costs of getting rid of wastes, and safety considerations for workforce and locals • Prevention of pollution

The Chemical Industry Click here to repeat The Chemical Industry. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

The Chemical Industry Click here to repeat The Chemical Industry. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Hess’s Law

Hess’s Law

Hess’s law • Hess’s law states that the enthalpy change for a chemical reaction is independent of the route taken. • This means that chemical equations can be treated like simultaneous equations. • Enthalpy changes can be worked out using Hess’s law.

Hess’s law • Hess’s law states that the enthalpy change for a chemical reaction is independent of the route taken. • This means that chemical equations can be treated like simultaneous equations. • Enthalpy changes can be worked out using Hess’s law.

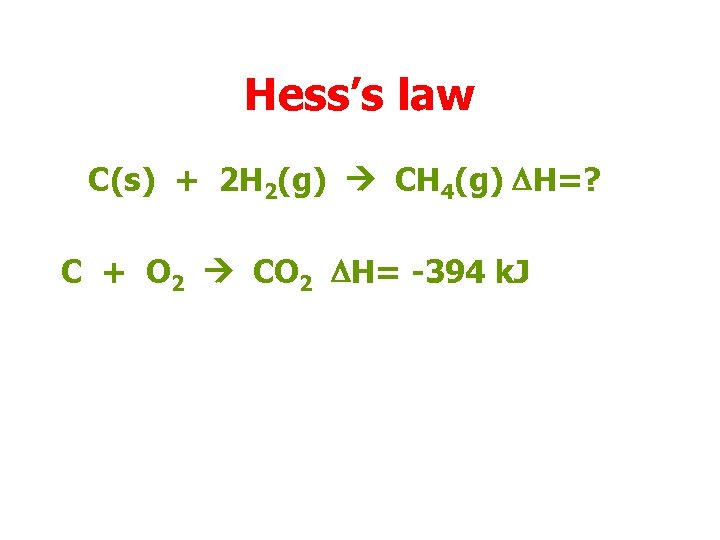

Hess’s law • Calculate the enthalpy change for the reaction: C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) using the enthalpies of combustion of carbon, hydrogen and methane.

Hess’s law • Calculate the enthalpy change for the reaction: C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) using the enthalpies of combustion of carbon, hydrogen and methane.

Hess’s law First write the target equation.

Hess’s law First write the target equation.

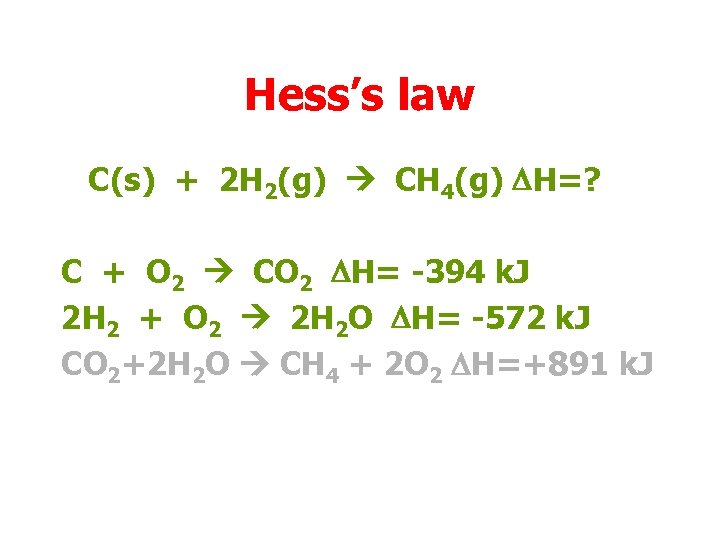

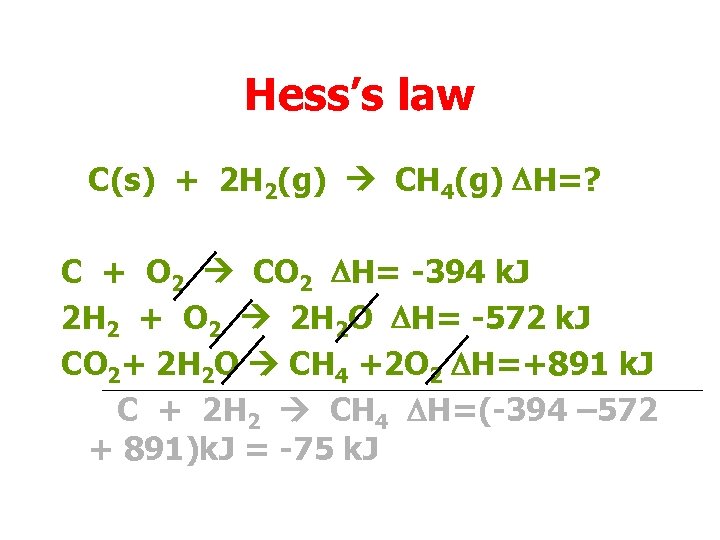

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? Then write the given equations.

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? Then write the given equations.

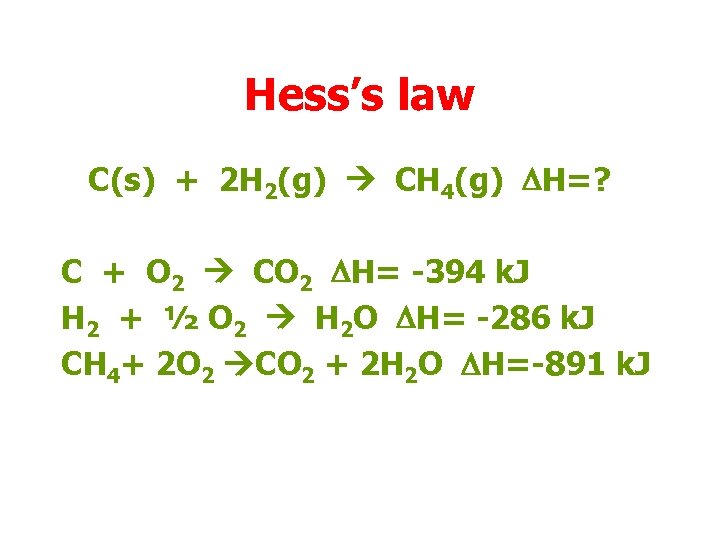

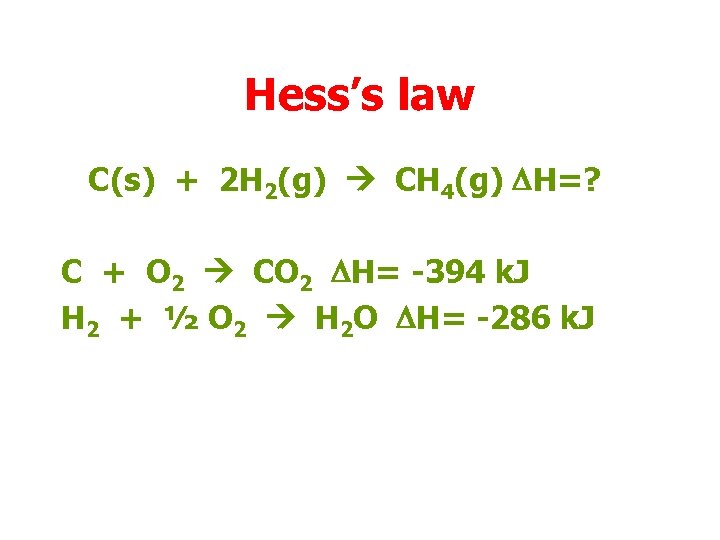

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J H 2 + ½ O 2 H 2 O DH= -286 k. J CH 4+ 2 O 2 CO 2 + 2 H 2 O DH=-891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J H 2 + ½ O 2 H 2 O DH= -286 k. J CH 4+ 2 O 2 CO 2 + 2 H 2 O DH=-891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? Build up the target equation from the given equations. If we multiply we must also multiply DH. If we reverse an equation we reverse the sign of DH.

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? Build up the target equation from the given equations. If we multiply we must also multiply DH. If we reverse an equation we reverse the sign of DH.

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J H 2 + ½ O 2 H 2 O DH= -286 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J H 2 + ½ O 2 H 2 O DH= -286 k. J

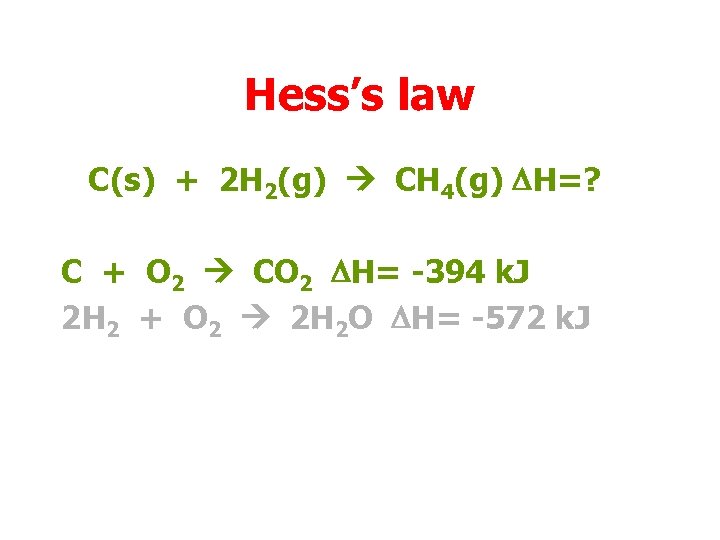

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J

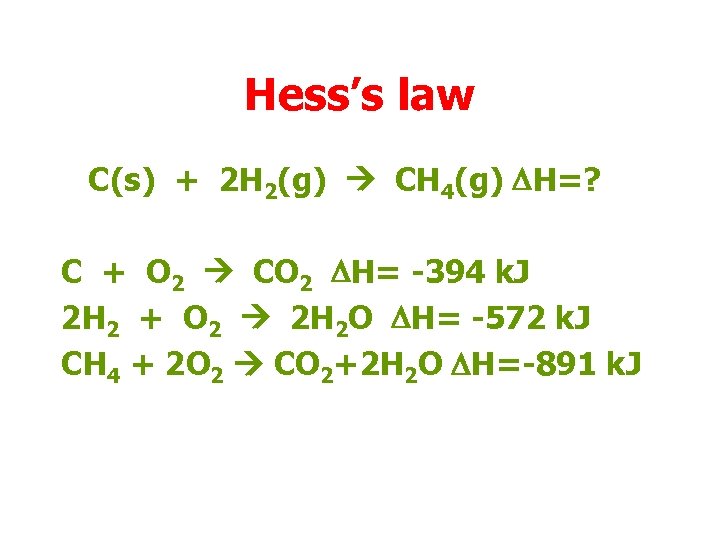

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CH 4 + 2 O 2 CO 2+2 H 2 O DH=-891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CH 4 + 2 O 2 CO 2+2 H 2 O DH=-891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

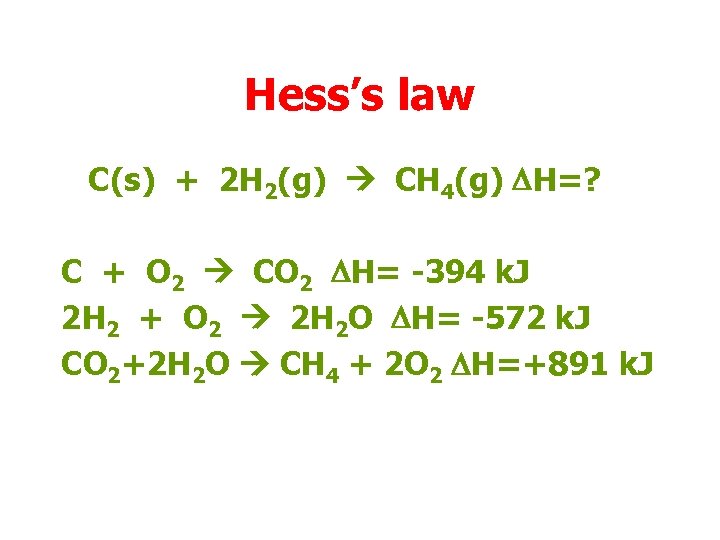

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? We can add all the equations, striking out species that will appear in equal numbers on both sides.

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? We can add all the equations, striking out species that will appear in equal numbers on both sides.

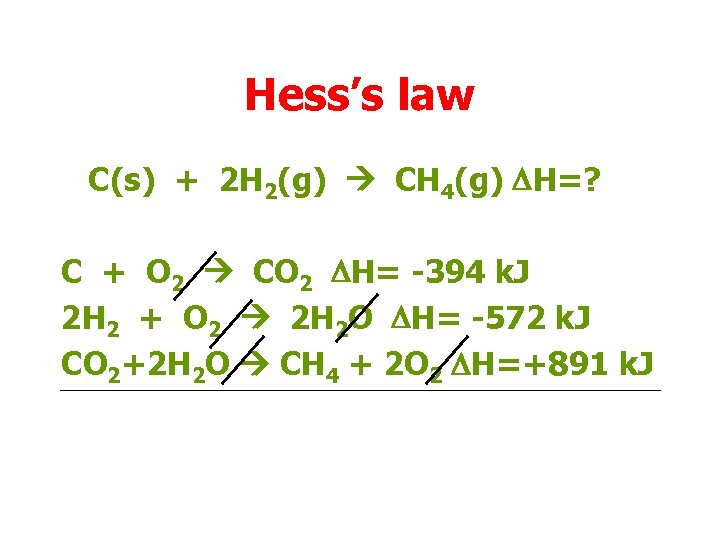

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+2 H 2 O CH 4 + 2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J

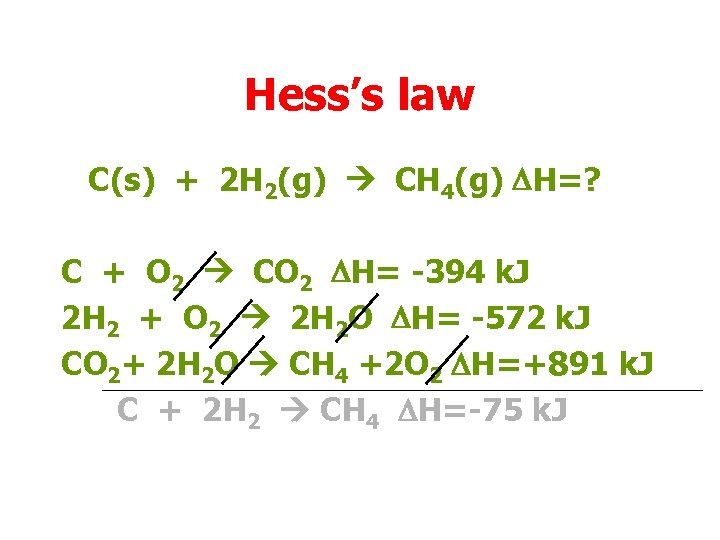

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+ 2 H 2 O CH 4 +2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J C + 2 H 2 CH 4 DH=(-394 – 572 + 891)k. J = -75 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+ 2 H 2 O CH 4 +2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J C + 2 H 2 CH 4 DH=(-394 – 572 + 891)k. J = -75 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+ 2 H 2 O CH 4 +2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J C + 2 H 2 CH 4 DH=-75 k. J

Hess’s law C(s) + 2 H 2(g) CH 4(g) DH=? C + O 2 CO 2 DH= -394 k. J 2 H 2 + O 2 2 H 2 O DH= -572 k. J CO 2+ 2 H 2 O CH 4 +2 O 2 DH=+891 k. J C + 2 H 2 CH 4 DH=-75 k. J

Hess’s Law Click here to repeat Hess’s Law. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Hess’s Law Click here to repeat Hess’s Law. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Equilibrium

Equilibrium

Dynamic Equilibrium • Reversible reactions reach a state of dynamic equilibrium • The rates of forward and reverse reactions are equal. • At equilibrium, the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant, although not necessarily equal.

Dynamic Equilibrium • Reversible reactions reach a state of dynamic equilibrium • The rates of forward and reverse reactions are equal. • At equilibrium, the concentrations of reactants and products remain constant, although not necessarily equal.

Changing the Equilibrium • Using a catalyst does not change the position of the equilibrium. • A catalyst speeds up both the forward and back reactions equally and so the equilibrium is reached more quickly.

Changing the Equilibrium • Using a catalyst does not change the position of the equilibrium. • A catalyst speeds up both the forward and back reactions equally and so the equilibrium is reached more quickly.

Changing the Equilibrium • Changes in concentration, pressure and temperature can alter the position of equilibrium. • Le Chatelier’s Principle states that when we act on an equilibrium the position of the equilibrium will move to reduce the effect of the change.

Changing the Equilibrium • Changes in concentration, pressure and temperature can alter the position of equilibrium. • Le Chatelier’s Principle states that when we act on an equilibrium the position of the equilibrium will move to reduce the effect of the change.

Concentration • Consider the equilibrium: A+B C+D If we increase the concentration of A, we speed up the forward reaction. This results in more C and D being formed.

Concentration • Consider the equilibrium: A+B C+D If we increase the concentration of A, we speed up the forward reaction. This results in more C and D being formed.

Concentration • Consider the equilibrium: Br 2(aq) + H 2 O(l) 2 H+(aq) + Br-(aq) + Br. O-(aq) The solution is red-brown, due the Br 2 molecules. If we add sodium bromide, increasing the concentration of Br-, we favour the RHS and so the equilibrium moves to the left. The red-brown colour will increase.

Concentration • Consider the equilibrium: Br 2(aq) + H 2 O(l) 2 H+(aq) + Br-(aq) + Br. O-(aq) The solution is red-brown, due the Br 2 molecules. If we add sodium bromide, increasing the concentration of Br-, we favour the RHS and so the equilibrium moves to the left. The red-brown colour will increase.

Pressure • Remember: • 1 mole of any gas has the same volume (under the same conditions of pressure and temperature). • This means that the number of moles of has are the same as the volumes.

Pressure • Remember: • 1 mole of any gas has the same volume (under the same conditions of pressure and temperature). • This means that the number of moles of has are the same as the volumes.

Pressure • Increasing pressure means putting the same number of moles in a smaller space. • This is the same as increasing concentration. • To reduce this effect the equilibrium will shift so as to reduce the number of moles of gas.

Pressure • Increasing pressure means putting the same number of moles in a smaller space. • This is the same as increasing concentration. • To reduce this effect the equilibrium will shift so as to reduce the number of moles of gas.

Pressure • Increasing pressure favours the side with the smaller volume of gas. Consider: N 2 O 4(g) 2 NO 2(g) 1 mole 2 moles 1 volume 2 volumes • If we increase the pressure we favour the forward reaction, so more N 2 O 4 is formed.

Pressure • Increasing pressure favours the side with the smaller volume of gas. Consider: N 2 O 4(g) 2 NO 2(g) 1 mole 2 moles 1 volume 2 volumes • If we increase the pressure we favour the forward reaction, so more N 2 O 4 is formed.

Temperature • An equilibrium involves two opposite reactions. • One of these processes must release energy (exothermic). • The reverse process must take in energy (endothermic).

Temperature • An equilibrium involves two opposite reactions. • One of these processes must release energy (exothermic). • The reverse process must take in energy (endothermic).

Temperature • First consider an exothermic reaction.

Temperature • First consider an exothermic reaction.

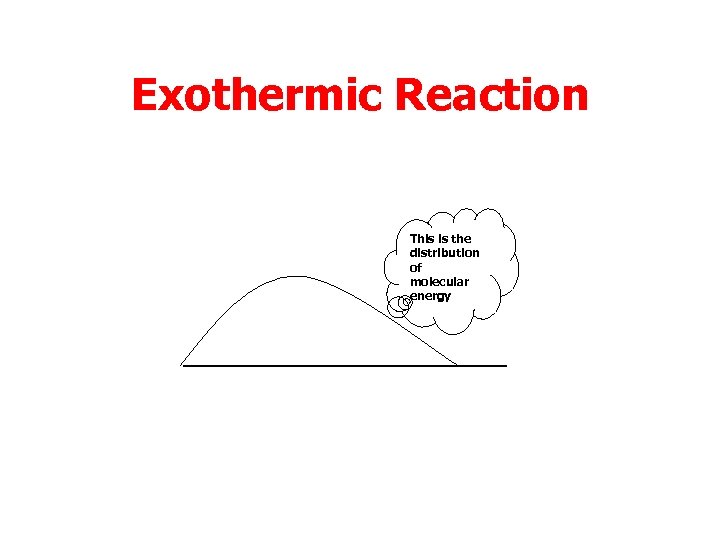

Exothermic Reaction This is the distribution of molecular energy

Exothermic Reaction This is the distribution of molecular energy

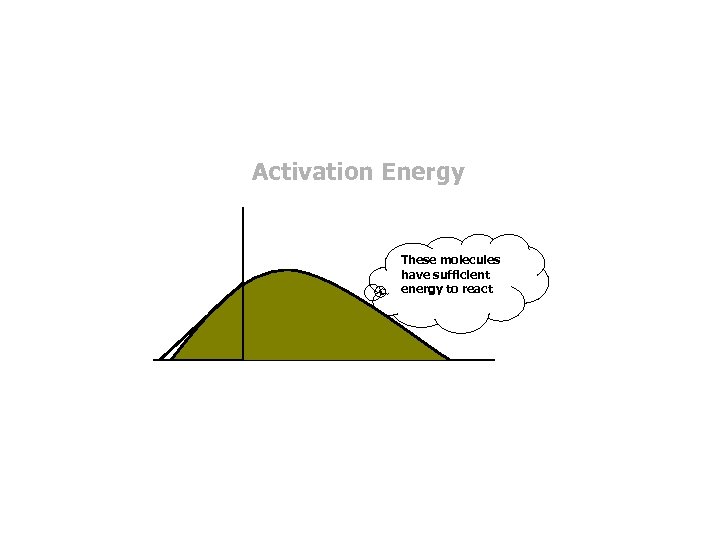

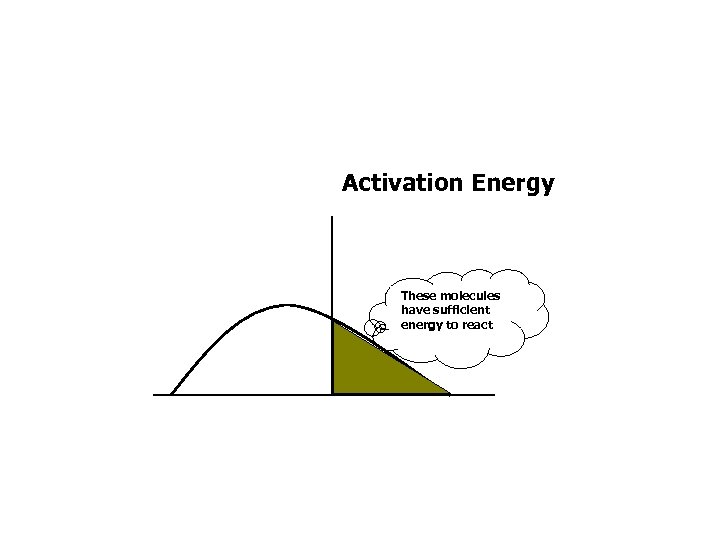

Activation Energy These molecules have sufficient energy to react

Activation Energy These molecules have sufficient energy to react

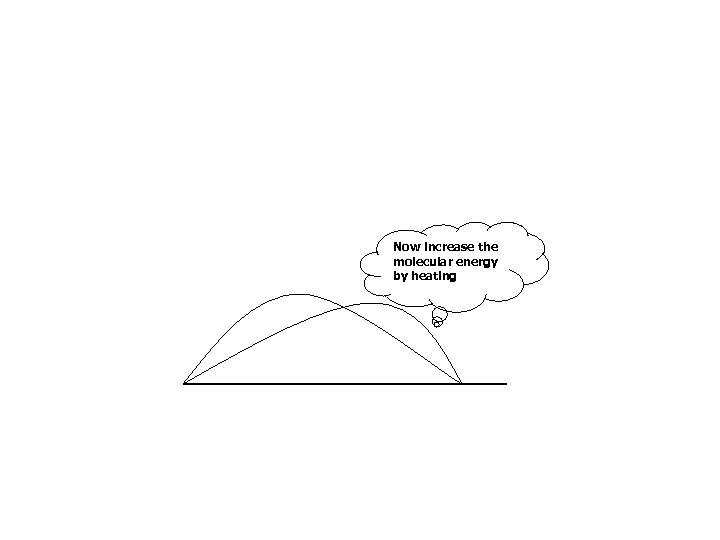

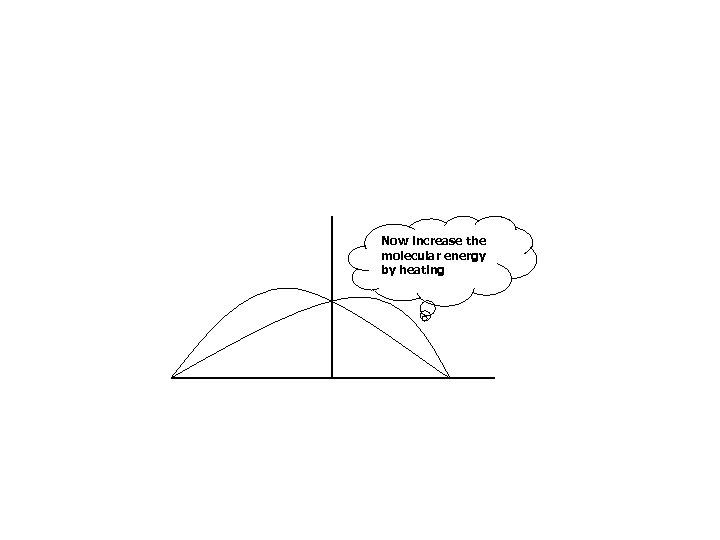

Now increase the molecular energy by heating

Now increase the molecular energy by heating

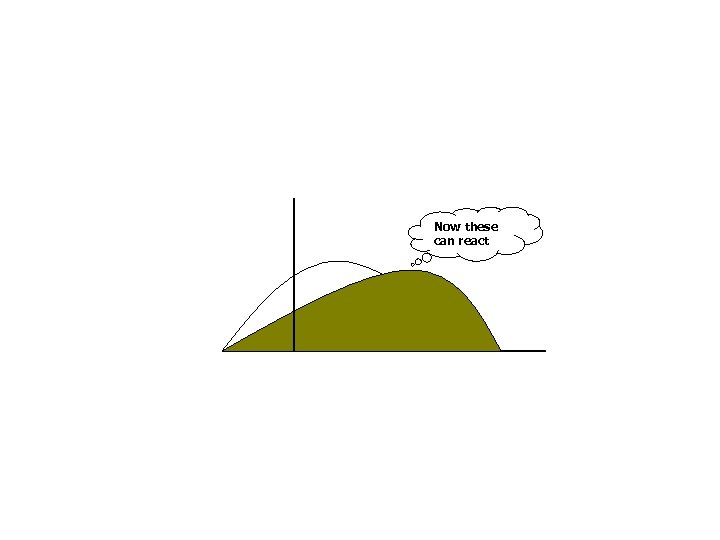

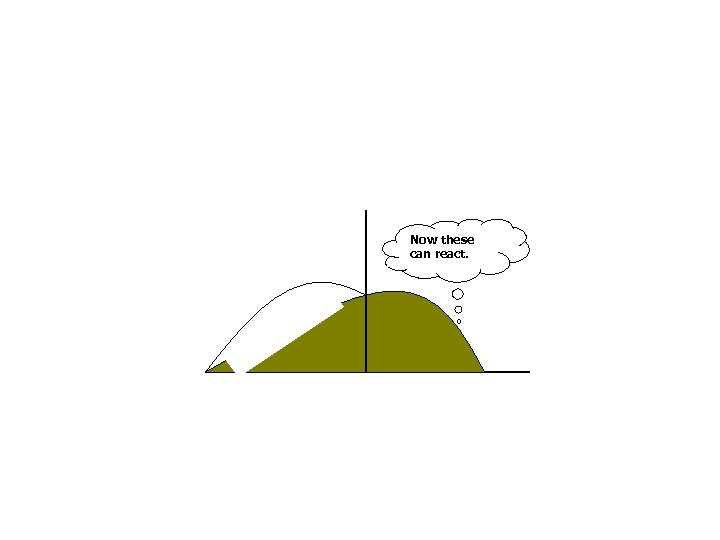

Now these can react

Now these can react

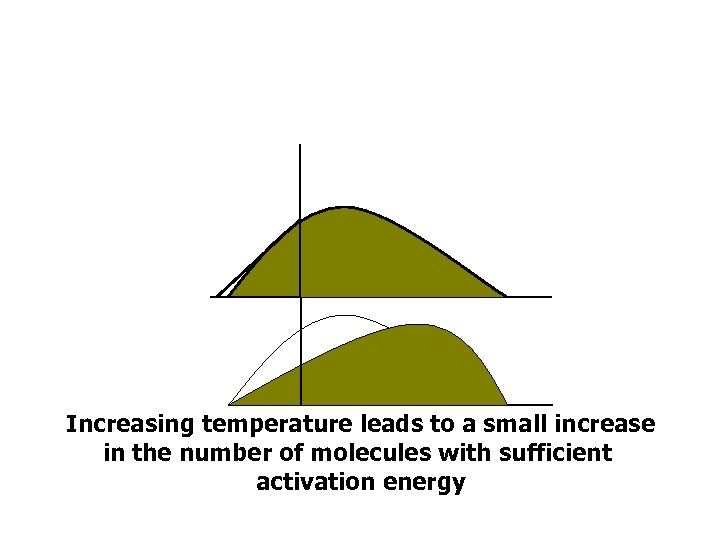

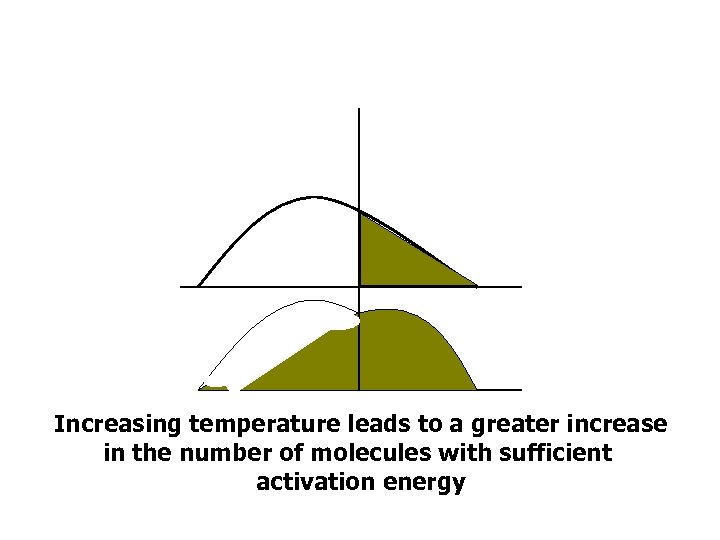

Increasing temperature leads to a small increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy

Increasing temperature leads to a small increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy

Temperature • Now consider an endothermic reaction.

Temperature • Now consider an endothermic reaction.

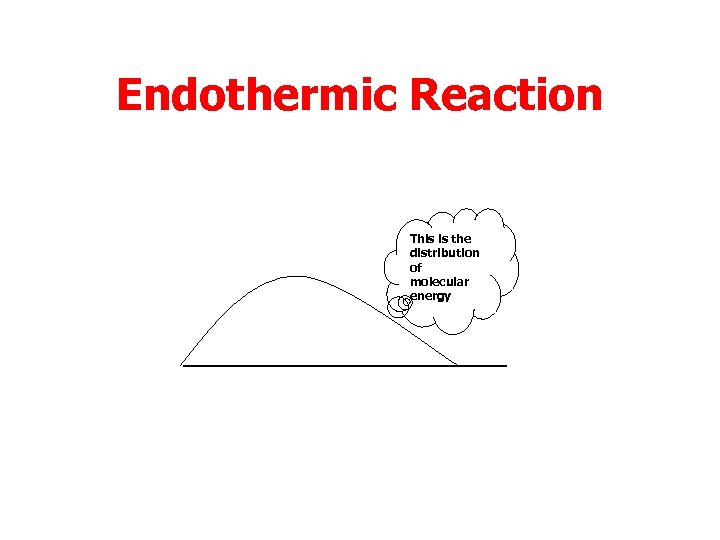

Endothermic Reaction This is the distribution of molecular energy

Endothermic Reaction This is the distribution of molecular energy

Activation Energy These molecules have sufficient energy to react

Activation Energy These molecules have sufficient energy to react

Now increase the molecular energy by heating

Now increase the molecular energy by heating

Now these can react.

Now these can react.

Increasing temperature leads to a greater increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy

Increasing temperature leads to a greater increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy

Temperature • The percentage increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy is much greater in the endothermic reaction, compared to the exothermic reaction.

Temperature • The percentage increase in the number of molecules with sufficient activation energy is much greater in the endothermic reaction, compared to the exothermic reaction.

• Thus both the endothermic and exothermic processes are speeded up by increasing temperature. • However an increase in temperature has a greater effect on the endothermic process.

• Thus both the endothermic and exothermic processes are speeded up by increasing temperature. • However an increase in temperature has a greater effect on the endothermic process.

• Increasing temperature favours the endothermic side of the equilibrium. Consider: N 2 O 4(g) 2 NO 2(g) DH= +58 k. J • If we increase the temperature we favour the forward reaction so more NO 2 is formed.

• Increasing temperature favours the endothermic side of the equilibrium. Consider: N 2 O 4(g) 2 NO 2(g) DH= +58 k. J • If we increase the temperature we favour the forward reaction so more NO 2 is formed.

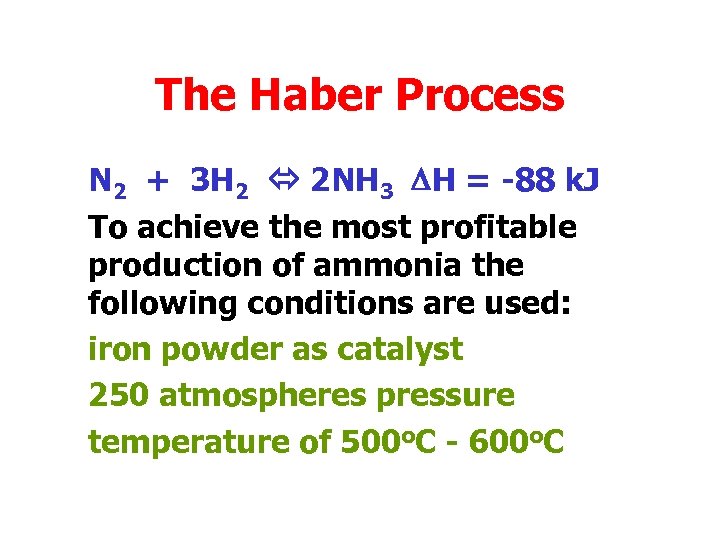

The Haber Process • The Haber process involves the preparation of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J • We shall look at the factors affecting this equilibrium.

The Haber Process • The Haber process involves the preparation of ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen. N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J • We shall look at the factors affecting this equilibrium.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J A catalyst of finely divided iron is used to increase the reaction speed and so shorten the time needed to reach the equilibrium.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J A catalyst of finely divided iron is used to increase the reaction speed and so shorten the time needed to reach the equilibrium.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J 1 mole 3 moles 2 moles 1 vol 3 vols 2 vols 4 vols 2 vols Since the RHS has a lower volume of gas than the LHS, higher pressure will favour the production of ammonia. A reaction chamber to withstand the higher pressure will cost much more.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J 1 mole 3 moles 2 moles 1 vol 3 vols 2 vols 4 vols 2 vols Since the RHS has a lower volume of gas than the LHS, higher pressure will favour the production of ammonia. A reaction chamber to withstand the higher pressure will cost much more.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J Since the forward reaction is exothermic more ammonia will be produced at low temperatures. At low temperatures the reaction is very slow so the rate of production of ammonia is low.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J Since the forward reaction is exothermic more ammonia will be produced at low temperatures. At low temperatures the reaction is very slow so the rate of production of ammonia is low.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J To ensure maximum conversion the unreacted gases are recycled through the reaction chamber after reaction.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J To ensure maximum conversion the unreacted gases are recycled through the reaction chamber after reaction.

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J To achieve the most profitable production of ammonia the following conditions are used: iron powder as catalyst 250 atmospheres pressure temperature of 500 o. C - 600 o. C

The Haber Process N 2 + 3 H 2 2 NH 3 DH = -88 k. J To achieve the most profitable production of ammonia the following conditions are used: iron powder as catalyst 250 atmospheres pressure temperature of 500 o. C - 600 o. C

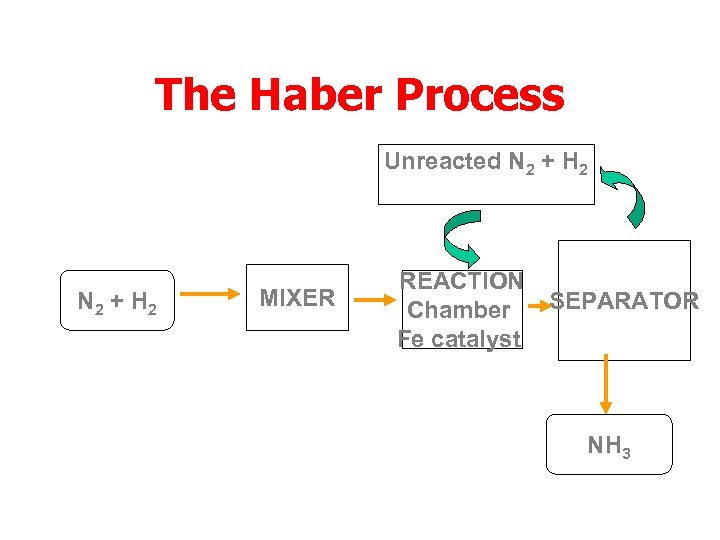

The Haber Process Unreacted N 2 + H 2 recycled N 2 + H 2 MIXER REACTION Chamber Fe catalyst SEPARATOR NH 3

The Haber Process Unreacted N 2 + H 2 recycled N 2 + H 2 MIXER REACTION Chamber Fe catalyst SEPARATOR NH 3

Equilibrium Click here to repeat Equilibrium. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Equilibrium Click here to repeat Equilibrium. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Acids and Bases

Acids and Bases

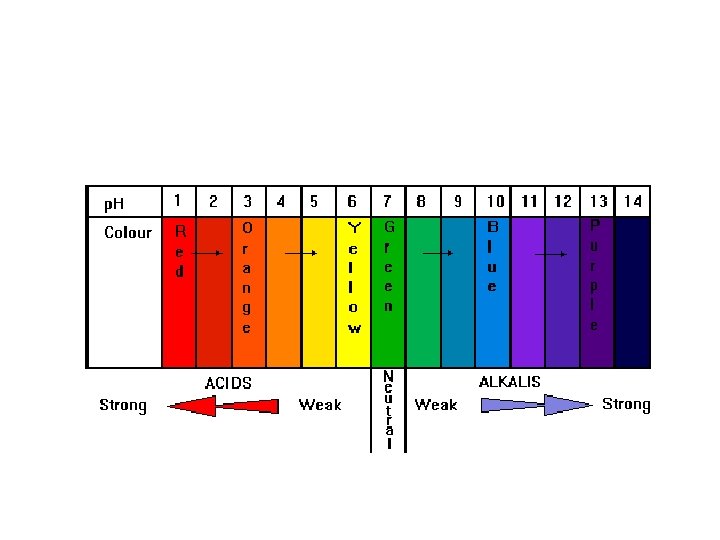

p. H • • • p. H is a scale of acidity. It can be measured using: p. H paper Universal Indicator solution A p. H meter.

p. H • • • p. H is a scale of acidity. It can be measured using: p. H paper Universal Indicator solution A p. H meter.

• We carry out an experiment where we progressively dilute acid. Tube 1 10 ml 0. 1 mol/l hydrochloric acid

• We carry out an experiment where we progressively dilute acid. Tube 1 10 ml 0. 1 mol/l hydrochloric acid

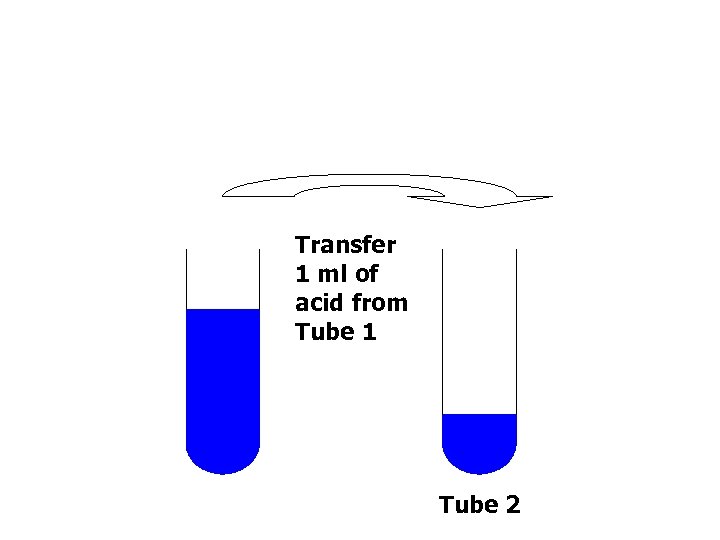

Transfer 1 ml of acid from Tube 1 Tube 2

Transfer 1 ml of acid from Tube 1 Tube 2

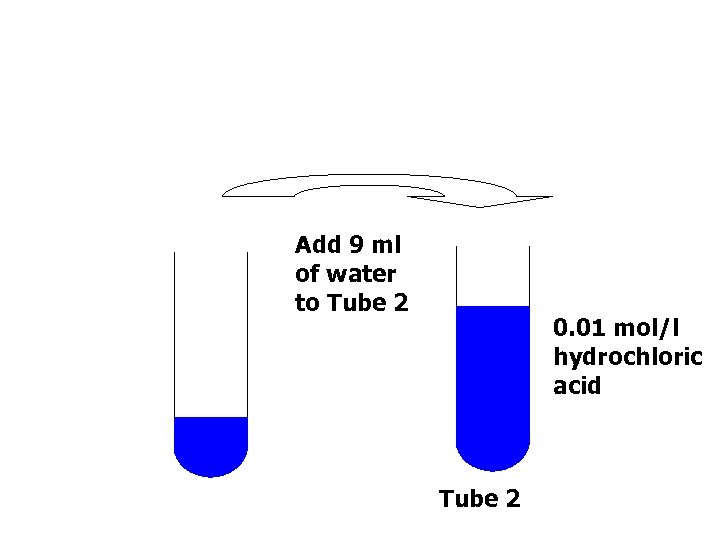

Add 9 ml of water to Tube 2 0. 01 mol/l hydrochloric acid Tube 2

Add 9 ml of water to Tube 2 0. 01 mol/l hydrochloric acid Tube 2

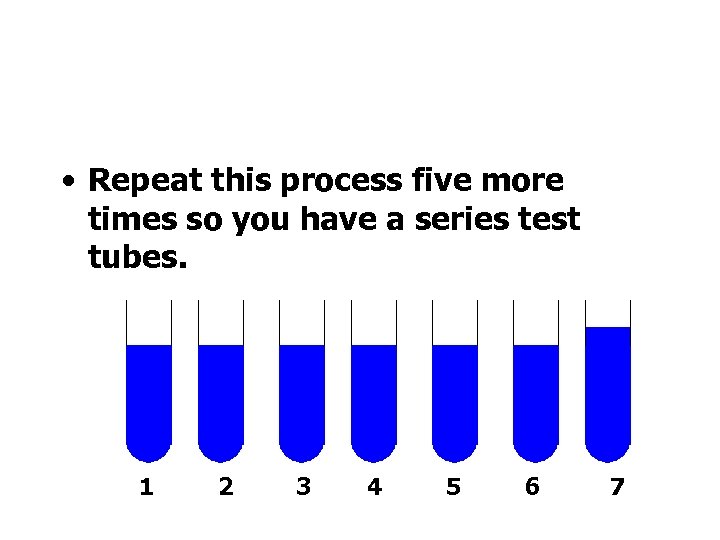

• Repeat this process five more times so you have a series test tubes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

• Repeat this process five more times so you have a series test tubes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

![• Concentrations are: 1 [H+] 2 10 -1 10 -2 3 4 5 • Concentrations are: 1 [H+] 2 10 -1 10 -2 3 4 5](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-82.jpg) • Concentrations are: 1 [H+] 2 10 -1 10 -2 3 4 5 6 7 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7

• Concentrations are: 1 [H+] 2 10 -1 10 -2 3 4 5 6 7 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7

![• Add Universal Indicator: 1 [H+] p. H 2 10 -1 10 -2 • Add Universal Indicator: 1 [H+] p. H 2 10 -1 10 -2](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-83.jpg) • Add Universal Indicator: 1 [H+] p. H 2 10 -1 10 -2 1 2 3 4 10 -3 10 -4 3 4 5 6 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 5 6 7

• Add Universal Indicator: 1 [H+] p. H 2 10 -1 10 -2 1 2 3 4 10 -3 10 -4 3 4 5 6 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 5 6 7

• Look for a relationship between the concentration of acid and the p. H. • If [H+] = 10 -x • p. H = x

• Look for a relationship between the concentration of acid and the p. H. • If [H+] = 10 -x • p. H = x

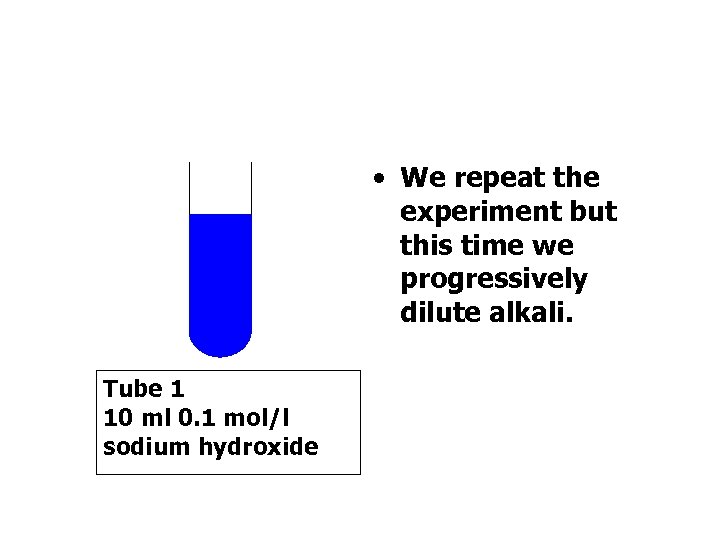

• We repeat the experiment but this time we progressively dilute alkali. Tube 1 10 ml 0. 1 mol/l sodium hydroxide

• We repeat the experiment but this time we progressively dilute alkali. Tube 1 10 ml 0. 1 mol/l sodium hydroxide

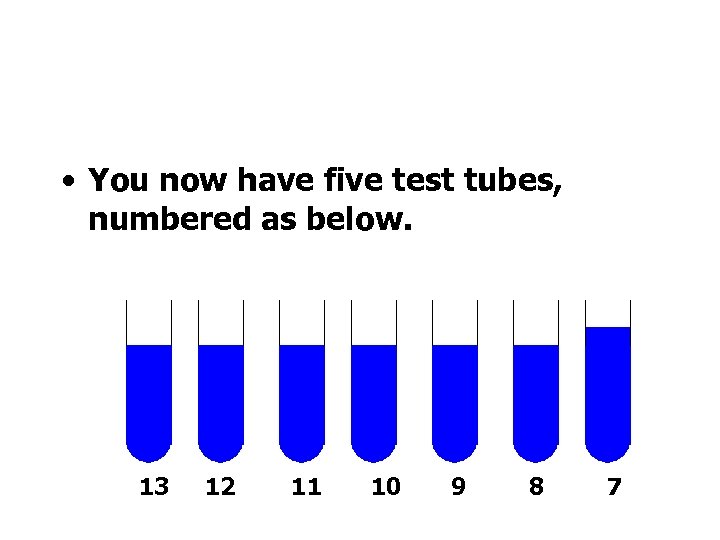

• You now have five test tubes, numbered as below. 13 12 11 10 9 8 7

• You now have five test tubes, numbered as below. 13 12 11 10 9 8 7

![• Concentrations are: 13 [OH-] 12 10 -1 10 -2 11 10 10 • Concentrations are: 13 [OH-] 12 10 -1 10 -2 11 10 10](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-87.jpg) • Concentrations are: 13 [OH-] 12 10 -1 10 -2 11 10 10 -3 10 -4 9 8 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7

• Concentrations are: 13 [OH-] 12 10 -1 10 -2 11 10 10 -3 10 -4 9 8 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7

![• Add Universal Indicator: 13 12 [OH-] 10 -1 10 -2 p. H • Add Universal Indicator: 13 12 [OH-] 10 -1 10 -2 p. H](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-88.jpg) • Add Universal Indicator: 13 12 [OH-] 10 -1 10 -2 p. H 13 12 11 10 10 -3 10 -4 11 10 9 8 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 9 8 7

• Add Universal Indicator: 13 12 [OH-] 10 -1 10 -2 p. H 13 12 11 10 10 -3 10 -4 11 10 9 8 7 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 9 8 7

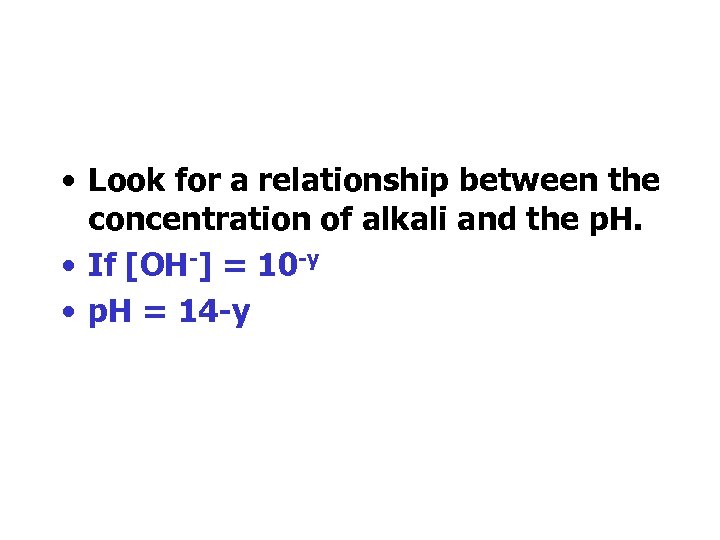

• Look for a relationship between the concentration of alkali and the p. H. • If [OH-] = 10 -y • p. H = 14 -y

• Look for a relationship between the concentration of alkali and the p. H. • If [OH-] = 10 -y • p. H = 14 -y

![[H+] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 [H+] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-90.jpg) [H+] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 p. H 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 [OH-] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 p. H 13 12 11 10 9 8 7

[H+] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 p. H 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 [OH-] mol/l 10 -1 10 -2 10 -3 10 -4 10 -5 10 -6 10 -7 p. H 13 12 11 10 9 8 7

![• If we look at water, p. H=7 • [H+] = [OH-] = • If we look at water, p. H=7 • [H+] = [OH-] =](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-91.jpg) • If we look at water, p. H=7 • [H+] = [OH-] = 10 -7 mol/l [H+] x [OH-] = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2 This is due to the equilibrium in water: H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) • For any solution [H+] x [OH-] = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2

• If we look at water, p. H=7 • [H+] = [OH-] = 10 -7 mol/l [H+] x [OH-] = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2 This is due to the equilibrium in water: H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) • For any solution [H+] x [OH-] = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2

![• Thus we can find [H+] for any solution. • What is [H+] • Thus we can find [H+] for any solution. • What is [H+]](https://present5.com/presentation/4fd42206895d3d98d1216cb94612fd17/image-92.jpg) • Thus we can find [H+] for any solution. • What is [H+] of a solution with p. H 10? [OH-] = 10 -4 mol/l [H+] x 10 -4 = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2 Thus [H+] = 10 -10

• Thus we can find [H+] for any solution. • What is [H+] of a solution with p. H 10? [OH-] = 10 -4 mol/l [H+] x 10 -4 = 10 -14 mol 2/l 2 Thus [H+] = 10 -10

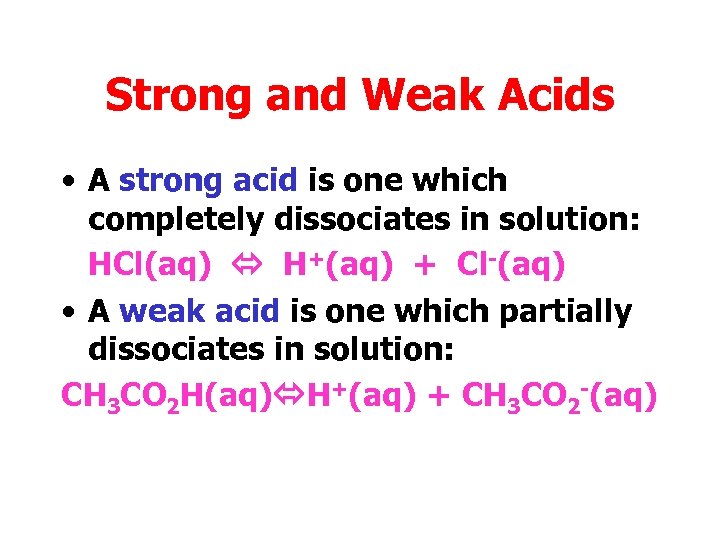

Strong and Weak Acids • A strong acid is one which completely dissociates in solution: HCl(aq) H+(aq) + Cl-(aq) • A weak acid is one which partially dissociates in solution: CH 3 CO 2 H(aq) H+(aq) + CH 3 CO 2 -(aq)

Strong and Weak Acids • A strong acid is one which completely dissociates in solution: HCl(aq) H+(aq) + Cl-(aq) • A weak acid is one which partially dissociates in solution: CH 3 CO 2 H(aq) H+(aq) + CH 3 CO 2 -(aq)

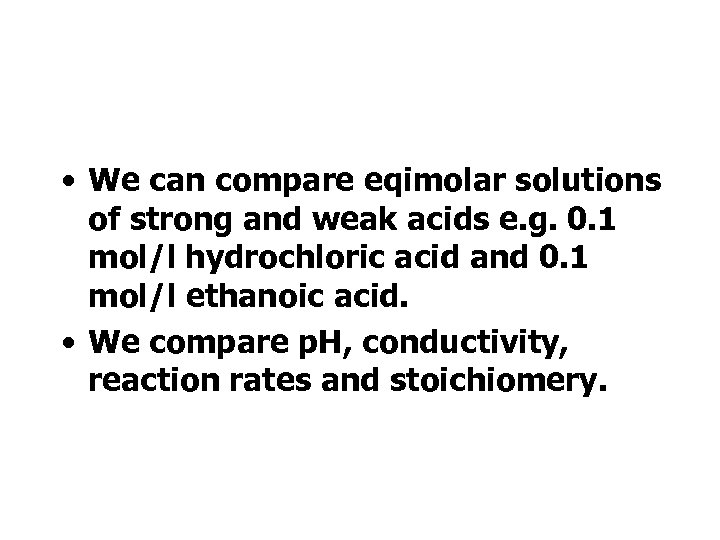

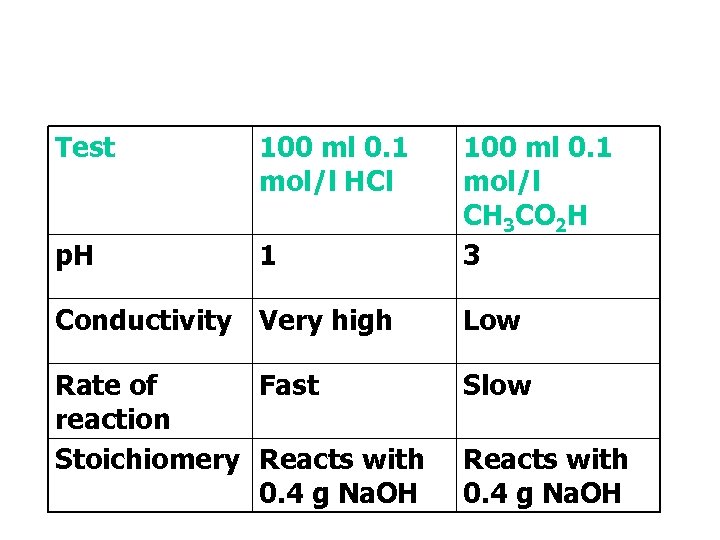

• We can compare eqimolar solutions of strong and weak acids e. g. 0. 1 mol/l hydrochloric acid and 0. 1 mol/l ethanoic acid. • We compare p. H, conductivity, reaction rates and stoichiomery.

• We can compare eqimolar solutions of strong and weak acids e. g. 0. 1 mol/l hydrochloric acid and 0. 1 mol/l ethanoic acid. • We compare p. H, conductivity, reaction rates and stoichiomery.

Test 100 ml 0. 1 mol/l HCl p. H 1 100 ml 0. 1 mol/l CH 3 CO 2 H 3 Conductivity Very high Low Rate of Fast reaction Stoichiomery Reacts with 0. 4 g Na. OH Slow Reacts with 0. 4 g Na. OH

Test 100 ml 0. 1 mol/l HCl p. H 1 100 ml 0. 1 mol/l CH 3 CO 2 H 3 Conductivity Very high Low Rate of Fast reaction Stoichiomery Reacts with 0. 4 g Na. OH Slow Reacts with 0. 4 g Na. OH

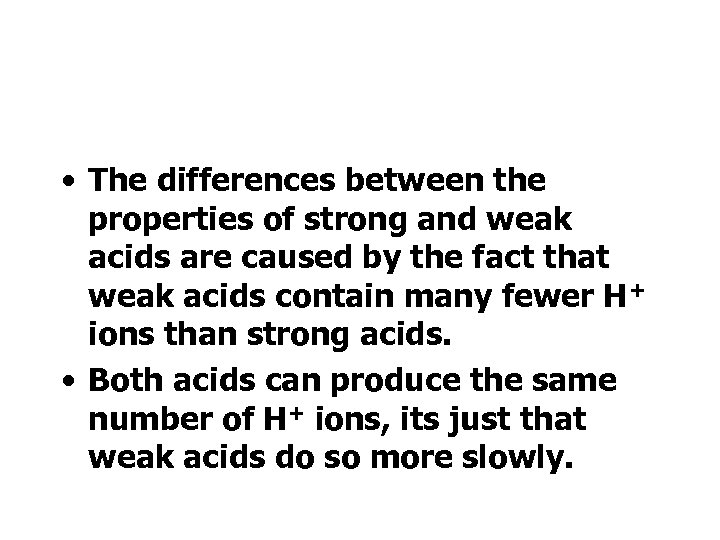

• The differences between the properties of strong and weak acids are caused by the fact that weak acids contain many fewer H+ ions than strong acids. • Both acids can produce the same number of H+ ions, its just that weak acids do so more slowly.

• The differences between the properties of strong and weak acids are caused by the fact that weak acids contain many fewer H+ ions than strong acids. • Both acids can produce the same number of H+ ions, its just that weak acids do so more slowly.

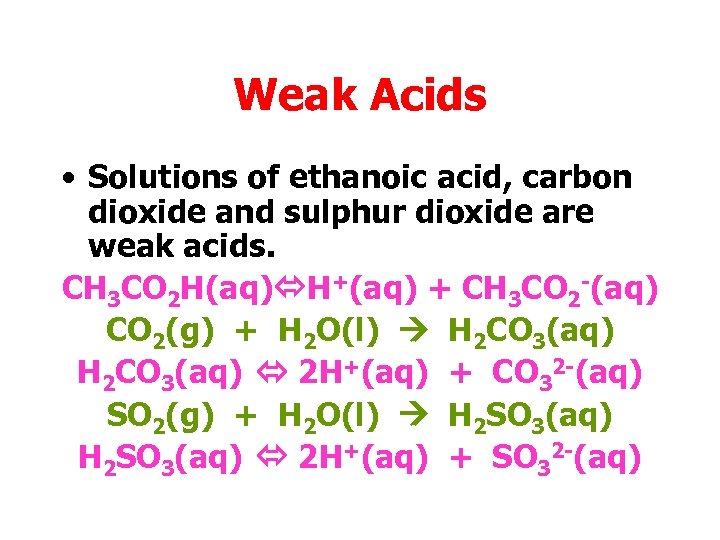

Weak Acids • Solutions of ethanoic acid, carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide are weak acids. CH 3 CO 2 H(aq) H+(aq) + CH 3 CO 2 -(aq) CO 2(g) + H 2 O(l) H 2 CO 3(aq) 2 H+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) SO 2(g) + H 2 O(l) H 2 SO 3(aq) 2 H+(aq) + SO 32 -(aq)

Weak Acids • Solutions of ethanoic acid, carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide are weak acids. CH 3 CO 2 H(aq) H+(aq) + CH 3 CO 2 -(aq) CO 2(g) + H 2 O(l) H 2 CO 3(aq) 2 H+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) SO 2(g) + H 2 O(l) H 2 SO 3(aq) 2 H+(aq) + SO 32 -(aq)

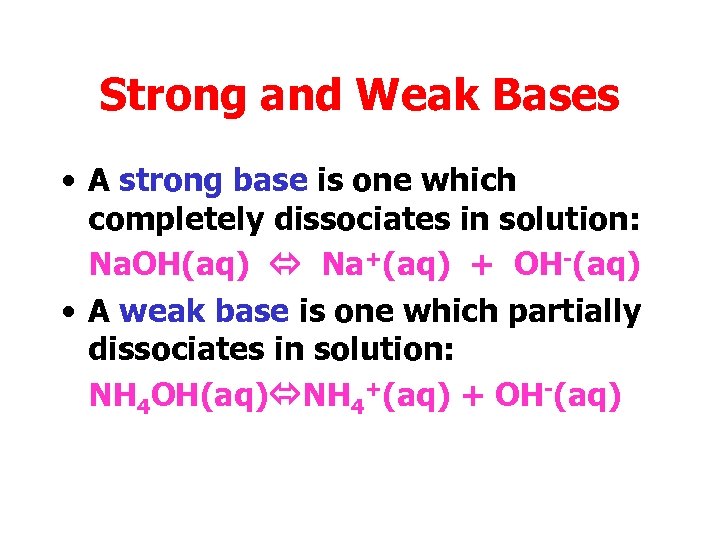

Strong and Weak Bases • A strong base is one which completely dissociates in solution: Na. OH(aq) Na+(aq) + OH-(aq) • A weak base is one which partially dissociates in solution: NH 4 OH(aq) NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Strong and Weak Bases • A strong base is one which completely dissociates in solution: Na. OH(aq) Na+(aq) + OH-(aq) • A weak base is one which partially dissociates in solution: NH 4 OH(aq) NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq)

• We can compare eqimolar solutions of strong and weak bases e. g. 0. 1 mol/l sodium hydroxide and 0. 1 mol/l ammonium hydroxide. • When we compare p. H, conductivity, reaction rates and stoichiomery we find similar results to the comparison of weak and strong acids.

• We can compare eqimolar solutions of strong and weak bases e. g. 0. 1 mol/l sodium hydroxide and 0. 1 mol/l ammonium hydroxide. • When we compare p. H, conductivity, reaction rates and stoichiomery we find similar results to the comparison of weak and strong acids.

Weak Bases • A solution of ammonia is a weak base. NH 3(g) + H 2 O(l) NH 4 OH(aq) NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Weak Bases • A solution of ammonia is a weak base. NH 3(g) + H 2 O(l) NH 4 OH(aq) NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Acids + Bases • A strong acid and a strong base produce a salt which is neutral. • A strong acid and a weak base produce a salt which is acidic. • A weak acid and a strong base produce a salt which is basic.

Acids + Bases • A strong acid and a strong base produce a salt which is neutral. • A strong acid and a weak base produce a salt which is acidic. • A weak acid and a strong base produce a salt which is basic.

Basic Salts

Basic Salts

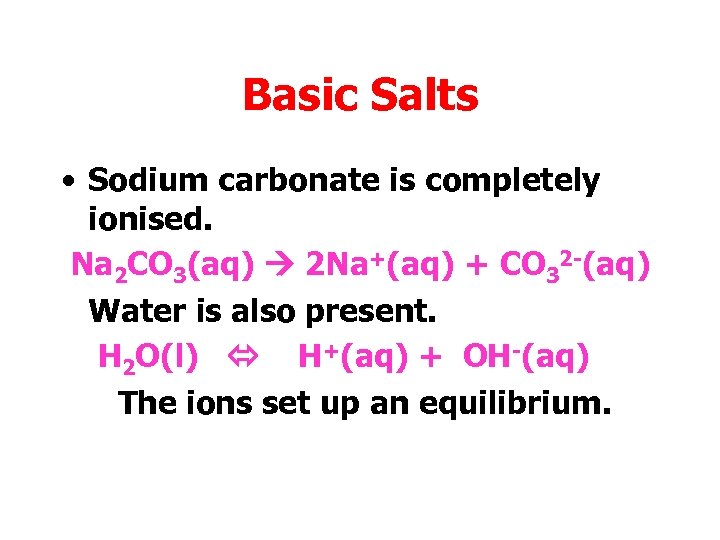

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised.

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised.

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq)

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq)

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present.

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present.

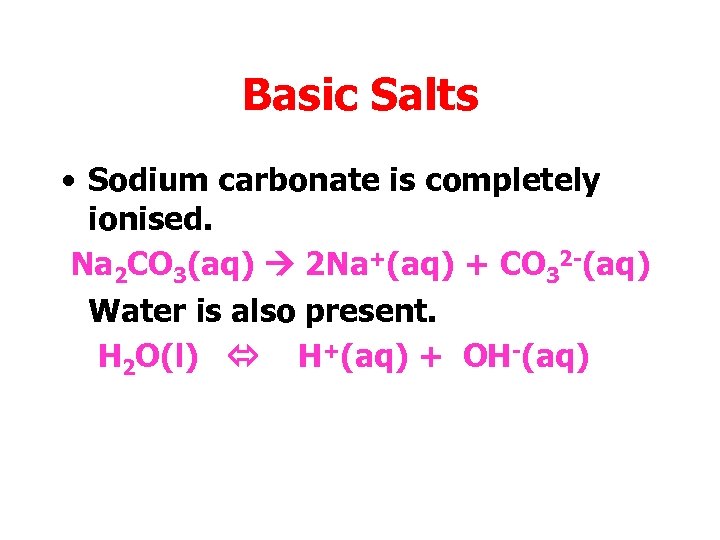

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium.

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium.

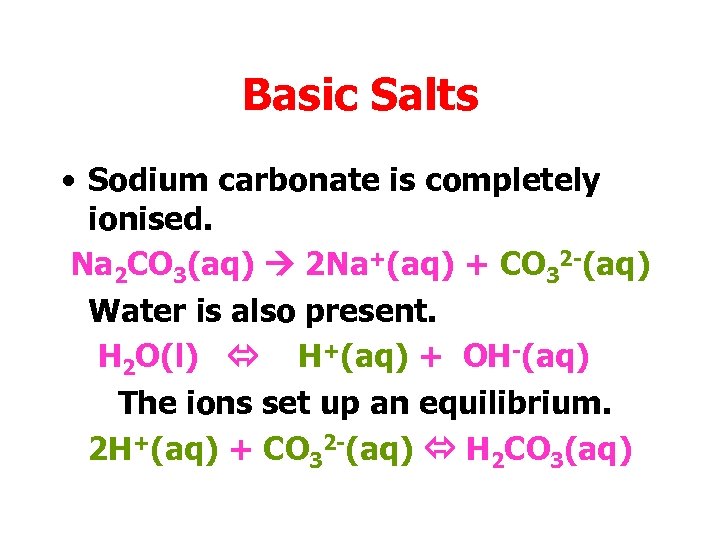

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium. 2 H+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) H 2 CO 3(aq)

Basic Salts • Sodium carbonate is completely ionised. Na 2 CO 3(aq) 2 Na+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium. 2 H+(aq) + CO 32 -(aq) H 2 CO 3(aq)

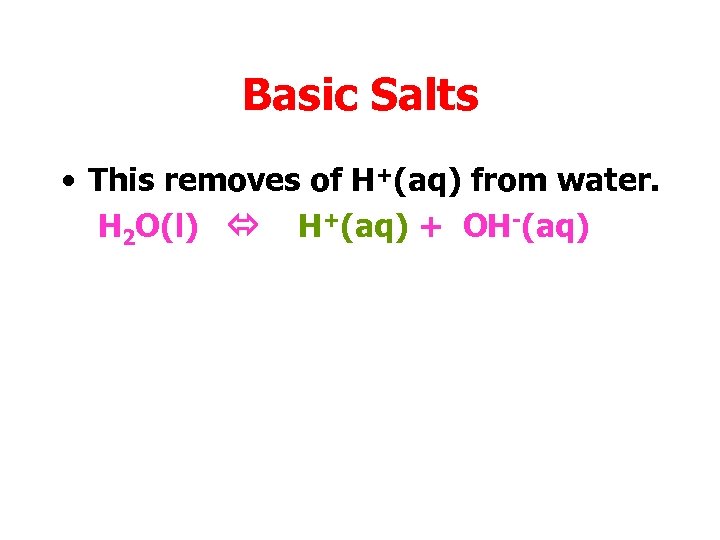

Basic Salts • This removes of H+(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Basic Salts • This removes of H+(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

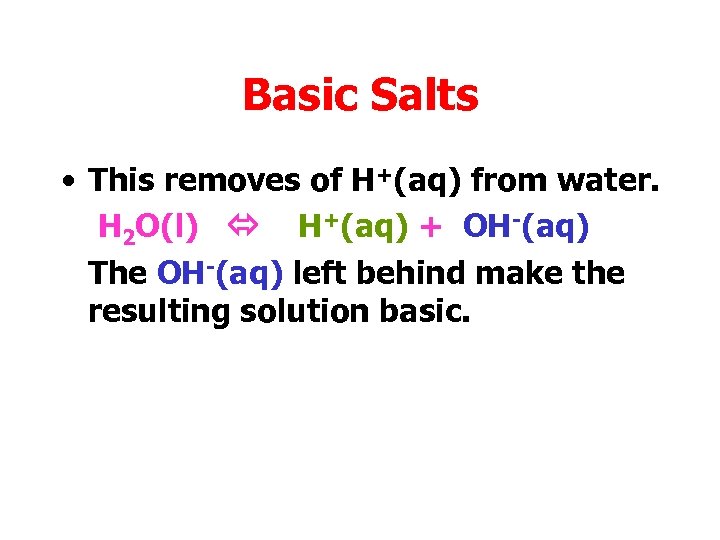

Basic Salts • This removes of H+(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The OH-(aq) left behind make the resulting solution basic.

Basic Salts • This removes of H+(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The OH-(aq) left behind make the resulting solution basic.

Acid Salts

Acid Salts

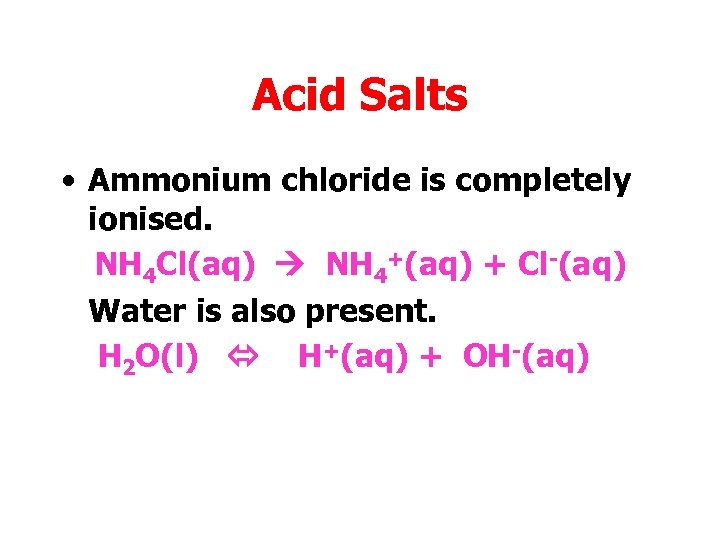

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised.

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised.

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq)

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq)

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present.

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present.

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium.

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium.

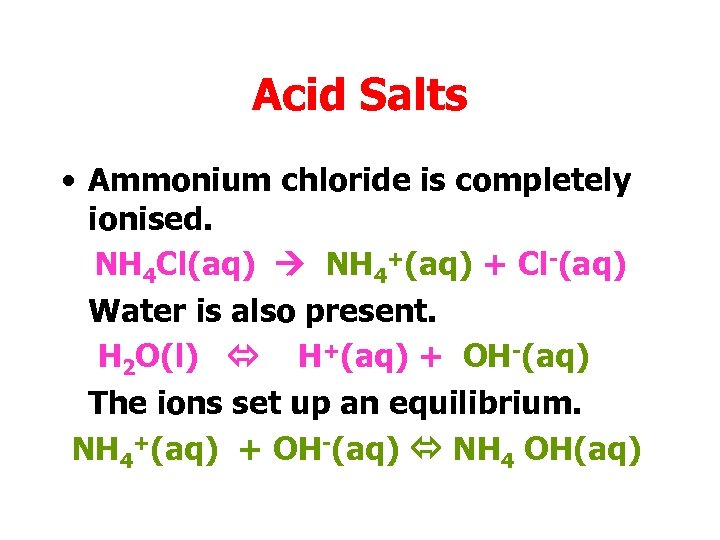

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium. NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq) NH 4 OH(aq)

Acid Salts • Ammonium chloride is completely ionised. NH 4 Cl(aq) NH 4+(aq) + Cl-(aq) Water is also present. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The ions set up an equilibrium. NH 4+(aq) + OH-(aq) NH 4 OH(aq)

Acid Salts • This removes of OH-(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Acid Salts • This removes of OH-(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq)

Acid Salts • This removes of OH-(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The H+(aq) left behind make the resulting solution acidic.

Acid Salts • This removes of OH-(aq) from water. H 2 O(l) H+(aq) + OH-(aq) The H+(aq) left behind make the resulting solution acidic.

Acids and Bases Click here to repeat Acids and Bases. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Acids and Bases Click here to repeat Acids and Bases. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Redox Reactions

Redox Reactions

Redox • An oxidation reaction is one where electrons are lost. Zn(s) Zn 2+(aq) + 2 e • A reduction reaction is one where electrons are gained. Cu 2+(aq) + 2 e Cu(s) • A redox reaction is one in which both oxidation and reduction are occurring. Zn(s) + Cu 2+(aq) Zn 2+(aq) + Cu(s)

Redox • An oxidation reaction is one where electrons are lost. Zn(s) Zn 2+(aq) + 2 e • A reduction reaction is one where electrons are gained. Cu 2+(aq) + 2 e Cu(s) • A redox reaction is one in which both oxidation and reduction are occurring. Zn(s) + Cu 2+(aq) Zn 2+(aq) + Cu(s)

Redox • An oxidising agent is a substance which accepts electrons. • This means that an oxidising agent must itself be reduced.

Redox • An oxidising agent is a substance which accepts electrons. • This means that an oxidising agent must itself be reduced.

Redox • A reducing agent is a substance which donates electrons. • This means that a reducing agent must itself be oxidised.

Redox • A reducing agent is a substance which donates electrons. • This means that a reducing agent must itself be oxidised.

Redox • We should be able to recognise oxidising and reducing agents from the reaction equation. • 5 Fe 2+ + Mn. O 4 - + 8 H+ 5 Fe 3+ + Mn 2+ + 4 H 2 O • Fe 2+ is oxidised to Fe 3+ so Mn. O 4– acts as an oxidising agent.

Redox • We should be able to recognise oxidising and reducing agents from the reaction equation. • 5 Fe 2+ + Mn. O 4 - + 8 H+ 5 Fe 3+ + Mn 2+ + 4 H 2 O • Fe 2+ is oxidised to Fe 3+ so Mn. O 4– acts as an oxidising agent.

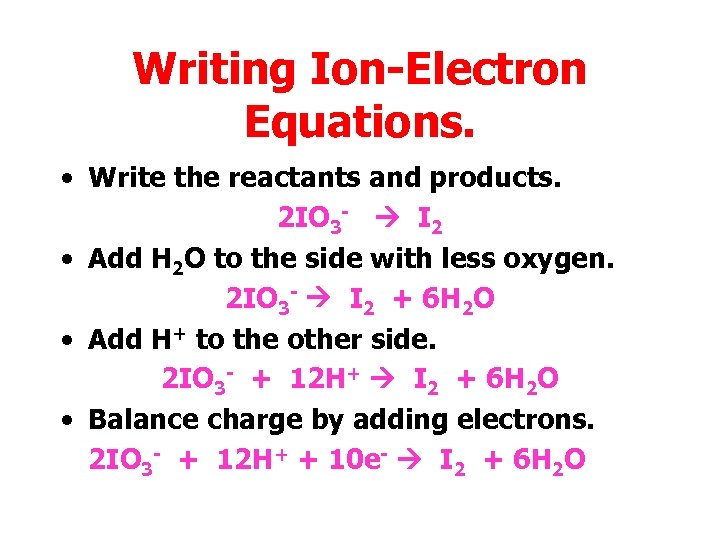

Writing Ion-Electron Equations. • Simple equations can be obtained from the data booklet. • More complex equations are written using the following routine.

Writing Ion-Electron Equations. • Simple equations can be obtained from the data booklet. • More complex equations are written using the following routine.

Writing Ion-Electron Equations. • Write the reactants and products. 2 IO 3 - I 2 • Add H 2 O to the side with less oxygen. 2 IO 3 - I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Add H+ to the other side. 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Balance charge by adding electrons. 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O

Writing Ion-Electron Equations. • Write the reactants and products. 2 IO 3 - I 2 • Add H 2 O to the side with less oxygen. 2 IO 3 - I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Add H+ to the other side. 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Balance charge by adding electrons. 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O

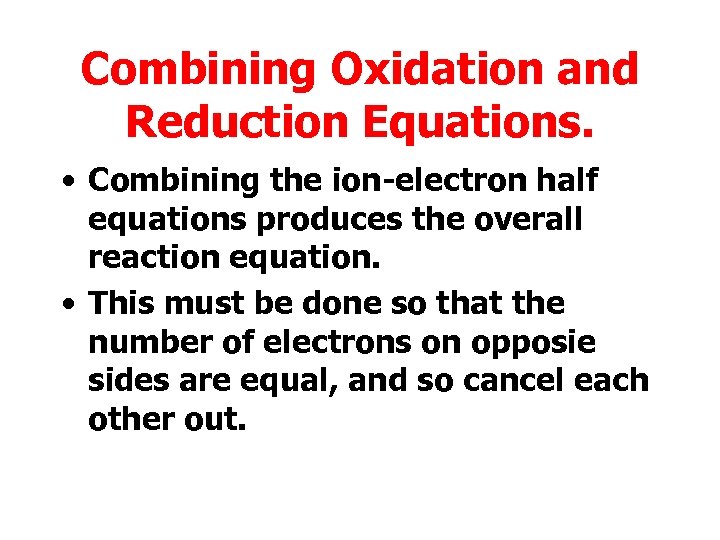

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Combining the ion-electron half equations produces the overall reaction equation. • This must be done so that the number of electrons on opposie sides are equal, and so cancel each other out.

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Combining the ion-electron half equations produces the overall reaction equation. • This must be done so that the number of electrons on opposie sides are equal, and so cancel each other out.

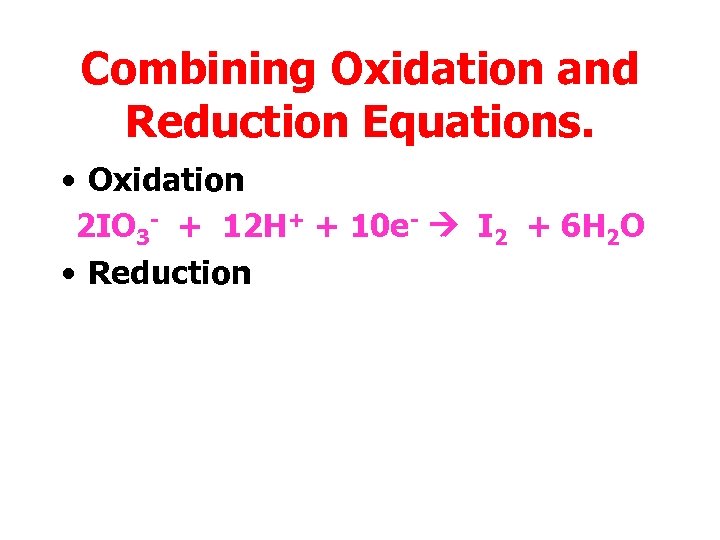

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation

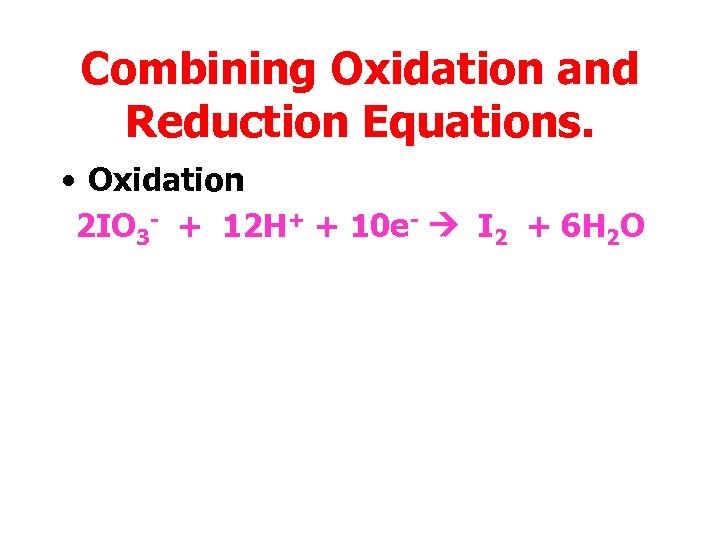

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction

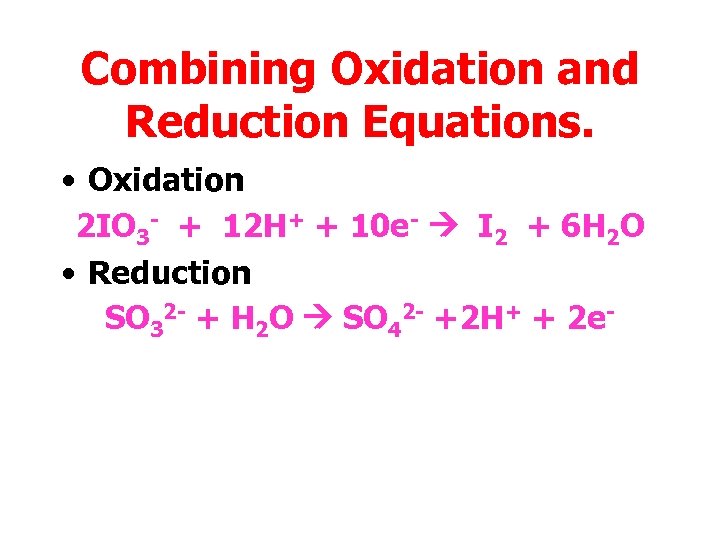

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction SO 32 - + H 2 O SO 42 - +2 H+ + 2 e-

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e- I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction SO 32 - + H 2 O SO 42 - +2 H+ + 2 e-

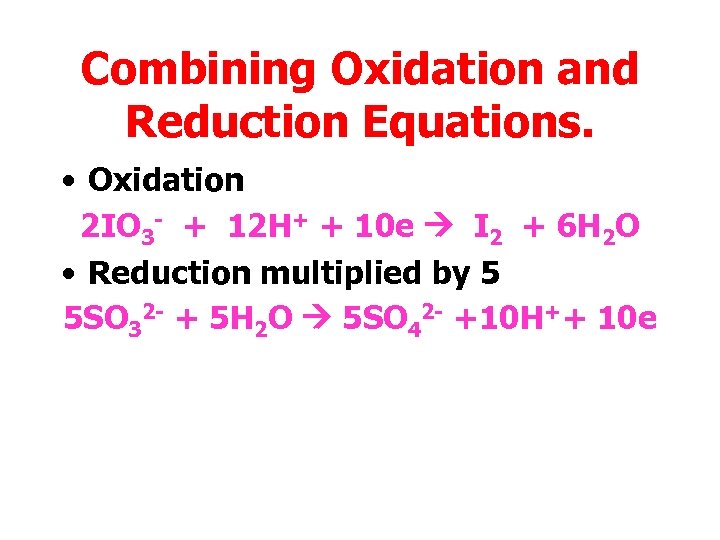

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction multiplied by 5 5 SO 32 - + 5 H 2 O 5 SO 42 - +10 H++ 10 e

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Oxidation 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e I 2 + 6 H 2 O • Reduction multiplied by 5 5 SO 32 - + 5 H 2 O 5 SO 42 - +10 H++ 10 e

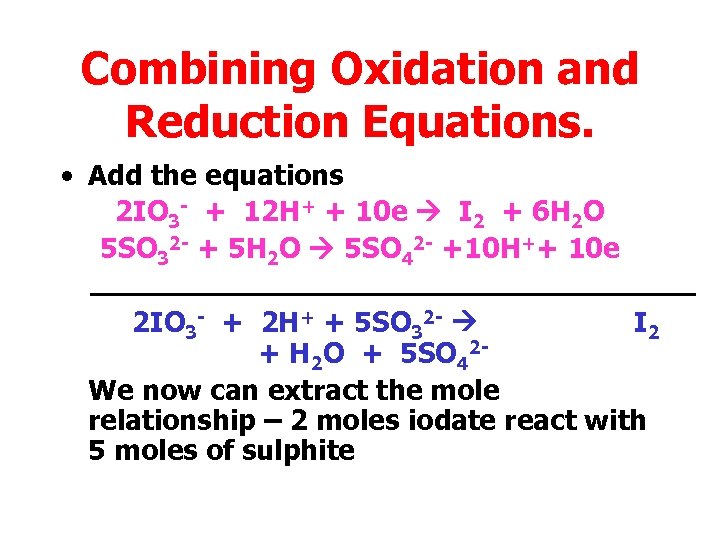

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Add the equations 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e I 2 + 6 H 2 O 5 SO 32 - + 5 H 2 O 5 SO 42 - +10 H++ 10 e 2 IO 3 - + 2 H+ + 5 SO 32 - I 2 + H 2 O + 5 SO 42 We now can extract the mole relationship – 2 moles iodate react with 5 moles of sulphite

Combining Oxidation and Reduction Equations. • Add the equations 2 IO 3 - + 12 H+ + 10 e I 2 + 6 H 2 O 5 SO 32 - + 5 H 2 O 5 SO 42 - +10 H++ 10 e 2 IO 3 - + 2 H+ + 5 SO 32 - I 2 + H 2 O + 5 SO 42 We now can extract the mole relationship – 2 moles iodate react with 5 moles of sulphite

Redox Titrations. • These can be carried out to calculate concentration. • Many use permanganate or starch/iodine reactions which are self-indicating – the colour change of the reaction tells you when the end point is reached.

Redox Titrations. • These can be carried out to calculate concentration. • Many use permanganate or starch/iodine reactions which are self-indicating – the colour change of the reaction tells you when the end point is reached.

Redox Titrations. • It was found that 12. 5 ml of of 0. 1 mol/l acidified potassium dichromate was required to oxidise the alcohol in a sample of 1 ml of wine. • Calculate the mass of alcohol in 1 ml of wine.

Redox Titrations. • It was found that 12. 5 ml of of 0. 1 mol/l acidified potassium dichromate was required to oxidise the alcohol in a sample of 1 ml of wine. • Calculate the mass of alcohol in 1 ml of wine.

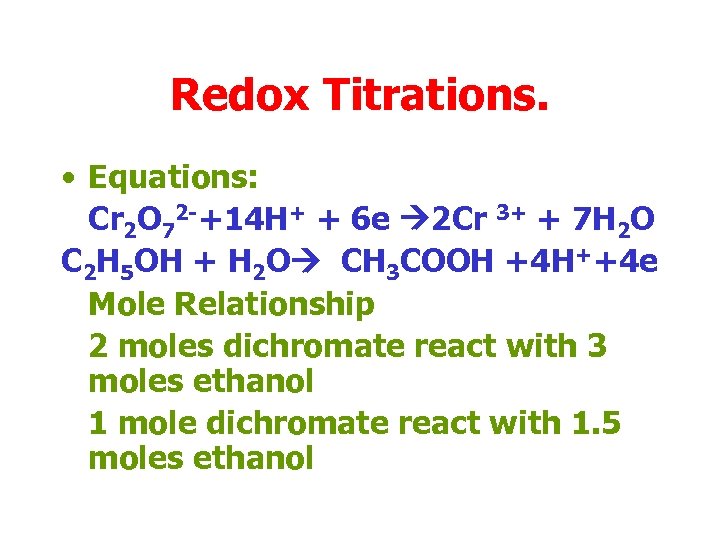

Redox Titrations. • Equations: Cr 2 O 72 -+14 H+ + 6 e 2 Cr 3+ + 7 H 2 O C 2 H 5 OH + H 2 O CH 3 COOH +4 H++4 e Mole Relationship 2 moles dichromate react with 3 moles ethanol 1 mole dichromate react with 1. 5 moles ethanol

Redox Titrations. • Equations: Cr 2 O 72 -+14 H+ + 6 e 2 Cr 3+ + 7 H 2 O C 2 H 5 OH + H 2 O CH 3 COOH +4 H++4 e Mole Relationship 2 moles dichromate react with 3 moles ethanol 1 mole dichromate react with 1. 5 moles ethanol

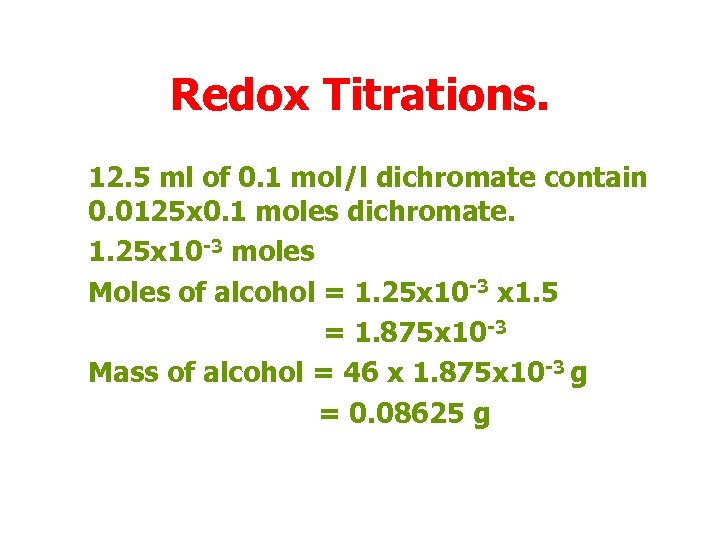

Redox Titrations. 12. 5 ml of 0. 1 mol/l dichromate contain 0. 0125 x 0. 1 moles dichromate. 1. 25 x 10 -3 moles Moles of alcohol = 1. 25 x 10 -3 x 1. 5 = 1. 875 x 10 -3 Mass of alcohol = 46 x 1. 875 x 10 -3 g = 0. 08625 g

Redox Titrations. 12. 5 ml of 0. 1 mol/l dichromate contain 0. 0125 x 0. 1 moles dichromate. 1. 25 x 10 -3 moles Moles of alcohol = 1. 25 x 10 -3 x 1. 5 = 1. 875 x 10 -3 Mass of alcohol = 46 x 1. 875 x 10 -3 g = 0. 08625 g

Electrolysis • Electrolysis takes place when electricity is passed through an ionic liquid. • Chemical reaction take place at the electrodes – reduction at the negative electrode and oxidation at the positive electrode.

Electrolysis • Electrolysis takes place when electricity is passed through an ionic liquid. • Chemical reaction take place at the electrodes – reduction at the negative electrode and oxidation at the positive electrode.

Electrolysis • The electrode reactions can be represented by ion electron equations. • In the electrolysis of nickel(II) chloride the reactions are: + electrode 2 Cl- Cl 2 + 2 e - electrode Ni 2+ + 2 e Ni

Electrolysis • The electrode reactions can be represented by ion electron equations. • In the electrolysis of nickel(II) chloride the reactions are: + electrode 2 Cl- Cl 2 + 2 e - electrode Ni 2+ + 2 e Ni

Electrolysis + electrode 2 Cl- Cl 2 + 2 e - electrode Ni 2+ + 2 e Ni • In both of these ion electron equations one mole of product is produced by two moles of electrons.

Electrolysis + electrode 2 Cl- Cl 2 + 2 e - electrode Ni 2+ + 2 e Ni • In both of these ion electron equations one mole of product is produced by two moles of electrons.

The Faraday • To find the value for one mole of electrons multiply Avogadro’s number by the charge on the electron (1. 6 x 10 -19 coulombs) • One mole of electrons is called a Faraday and is 96, 500 coulombs.

The Faraday • To find the value for one mole of electrons multiply Avogadro’s number by the charge on the electron (1. 6 x 10 -19 coulombs) • One mole of electrons is called a Faraday and is 96, 500 coulombs.

The Faraday • Using the value for the Faraday and the equation: • Charge = Current x Time (Coulombs) (Amps) (Seconds) we can carry out many calculations.

The Faraday • Using the value for the Faraday and the equation: • Charge = Current x Time (Coulombs) (Amps) (Seconds) we can carry out many calculations.

Redox Reactions Click here to repeat Redox Reactions. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Redox Reactions Click here to repeat Redox Reactions. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

Nuclear Chemistry

Nuclear Chemistry

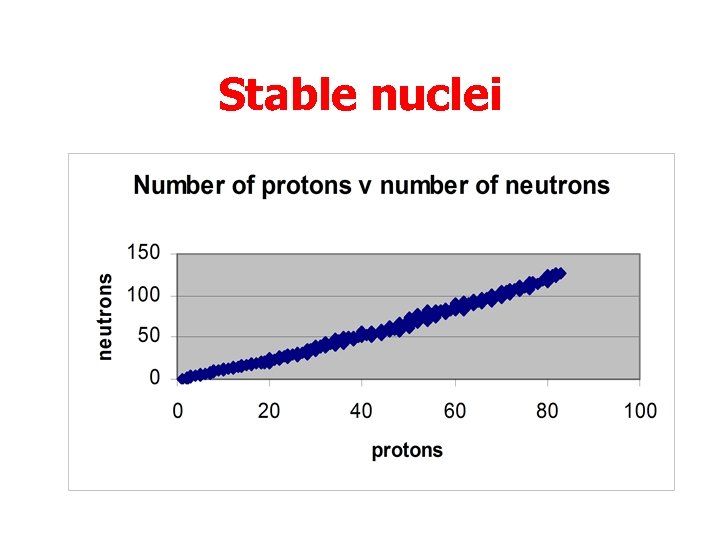

Stable nuclei • Nuclei contain protons and neutrons. • Energy is needed to hold these particles together. • We can plot the number of protons against the number of neutrons.

Stable nuclei • Nuclei contain protons and neutrons. • Energy is needed to hold these particles together. • We can plot the number of protons against the number of neutrons.

Stable nuclei

Stable nuclei

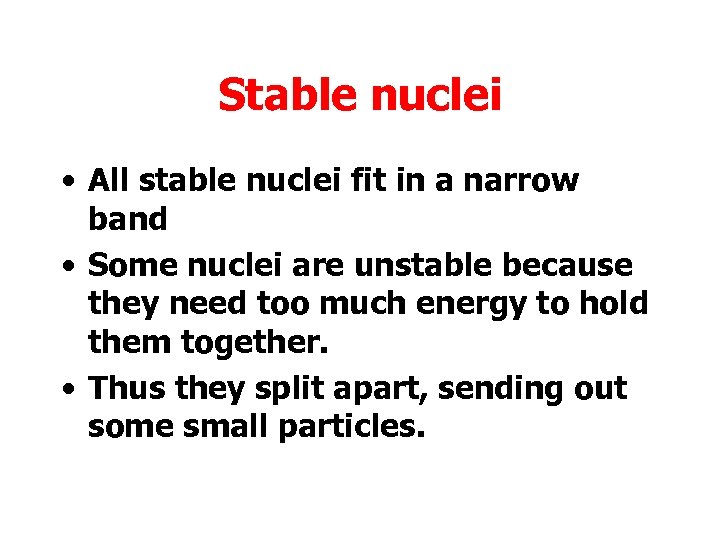

Stable nuclei • All stable nuclei fit in a narrow band • Some nuclei are unstable because they need too much energy to hold them together. • Thus they split apart, sending out some small particles.

Stable nuclei • All stable nuclei fit in a narrow band • Some nuclei are unstable because they need too much energy to hold them together. • Thus they split apart, sending out some small particles.

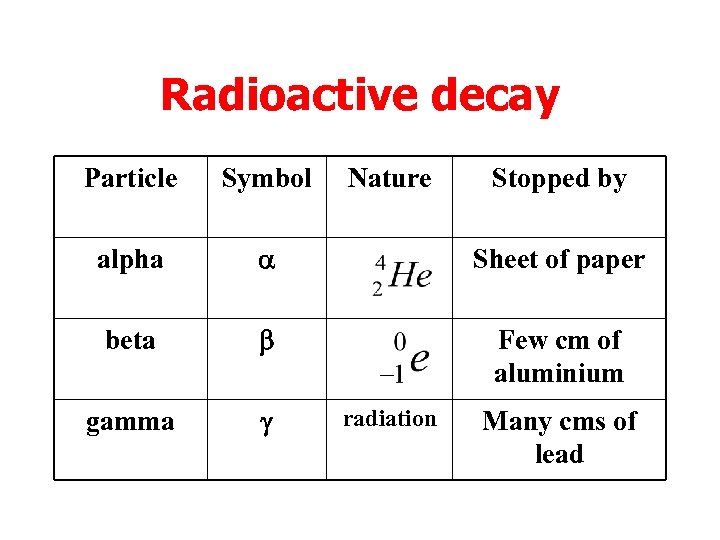

Radioactive decay Particle Symbol Nature alpha a Sheet of paper beta b Few cm of aluminium gamma g radiation Stopped by Many cms of lead

Radioactive decay Particle Symbol Nature alpha a Sheet of paper beta b Few cm of aluminium gamma g radiation Stopped by Many cms of lead

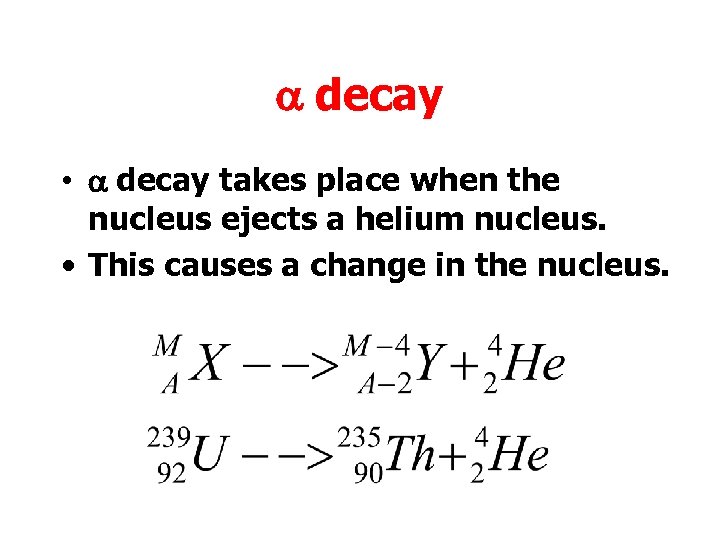

a decay • a decay takes place when the nucleus ejects a helium nucleus. • This causes a change in the nucleus.

a decay • a decay takes place when the nucleus ejects a helium nucleus. • This causes a change in the nucleus.

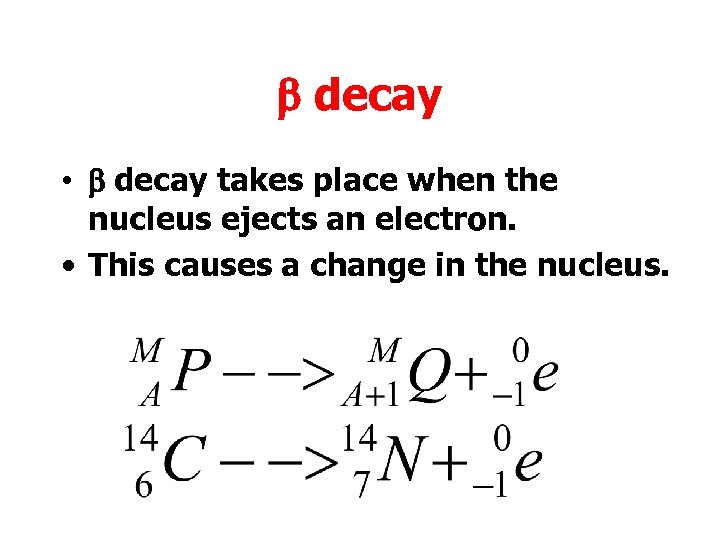

b decay • b decay takes place when the nucleus ejects an electron. • This causes a change in the nucleus.

b decay • b decay takes place when the nucleus ejects an electron. • This causes a change in the nucleus.

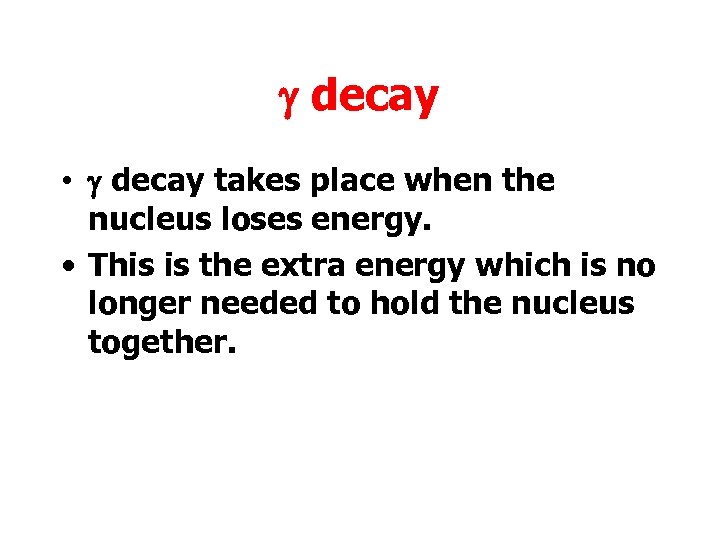

g decay • g decay takes place when the nucleus loses energy. • This is the extra energy which is no longer needed to hold the nucleus together.

g decay • g decay takes place when the nucleus loses energy. • This is the extra energy which is no longer needed to hold the nucleus together.

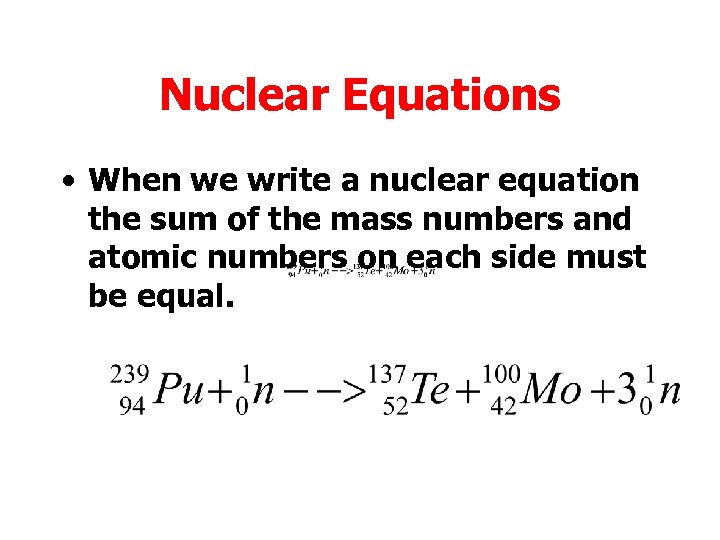

Nuclear Equations • When we write a nuclear equation the sum of the mass numbers and atomic numbers on each side must be equal.

Nuclear Equations • When we write a nuclear equation the sum of the mass numbers and atomic numbers on each side must be equal.

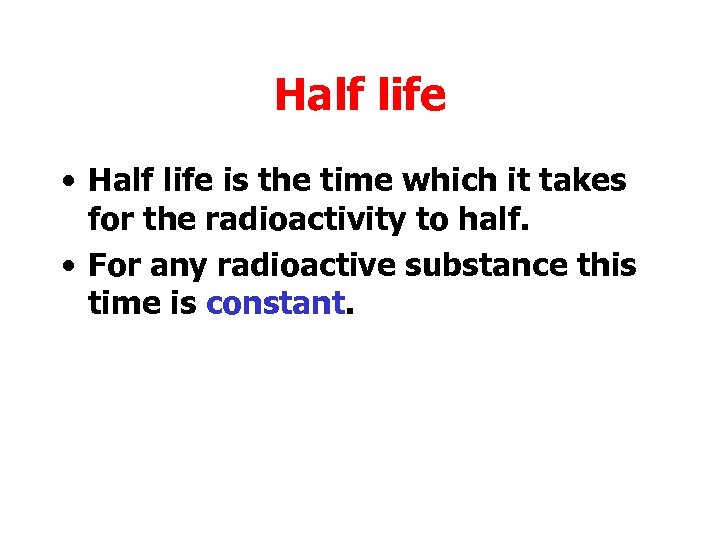

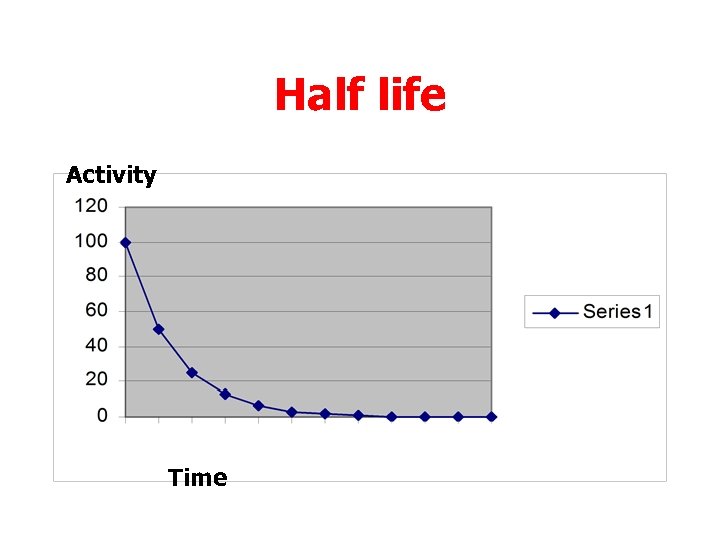

Half life • Half life is the time which it takes for the radioactivity to half. • For any radioactive substance this time is constant.

Half life • Half life is the time which it takes for the radioactivity to half. • For any radioactive substance this time is constant.

Half life • The decay of individual nuclei within a sample is random and is does not depend of chemical or physical state of the element. • Half lives of individual elements may vary from seconds to thousands of years.

Half life • The decay of individual nuclei within a sample is random and is does not depend of chemical or physical state of the element. • Half lives of individual elements may vary from seconds to thousands of years.

Half life • Calculations involving half life usually involve precise fractions e. g. • 3 H is a b-emitting isotope with a half life of 12. 3 years. How long will it take for the radioactivity of a sample to drop to 1/8 of its original value?

Half life • Calculations involving half life usually involve precise fractions e. g. • 3 H is a b-emitting isotope with a half life of 12. 3 years. How long will it take for the radioactivity of a sample to drop to 1/8 of its original value?

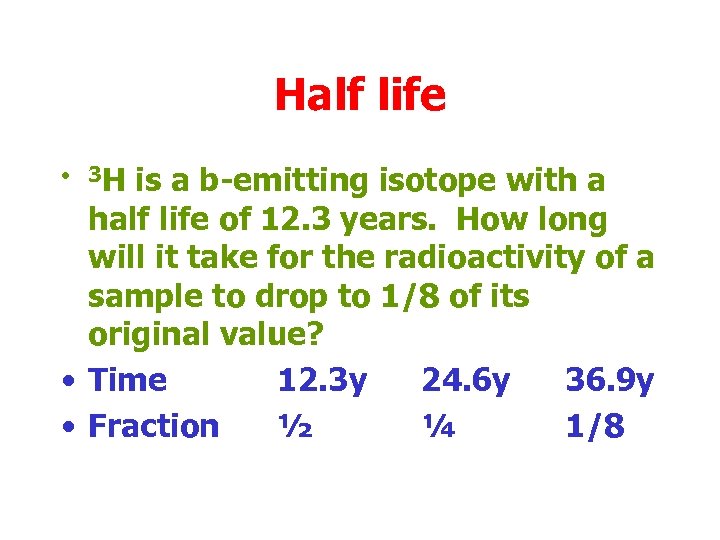

Half life • 3 H is a b-emitting isotope with a half life of 12. 3 years. How long will it take for the radioactivity of a sample to drop to 1/8 of its original value? • Time 12. 3 y 24. 6 y 36. 9 y • Fraction ½ ¼ 1/8

Half life • 3 H is a b-emitting isotope with a half life of 12. 3 years. How long will it take for the radioactivity of a sample to drop to 1/8 of its original value? • Time 12. 3 y 24. 6 y 36. 9 y • Fraction ½ ¼ 1/8

Half life • For examples where the numbers are more complex the quantity of radioactive material against time is best estimated from a graph.

Half life • For examples where the numbers are more complex the quantity of radioactive material against time is best estimated from a graph.

Half life Activity Time

Half life Activity Time

The Nuclear Chemistry Click here to repeat Nuclear Chemistry. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

The Nuclear Chemistry Click here to repeat Nuclear Chemistry. Click here to return to the Menu Click here to End.

The End Hope you found the revision useful. Come back soon!!

The End Hope you found the revision useful. Come back soon!!