7d1758032f4eac3cc934b30f12afef73.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 106

Types of Noun Phrases Referential vs. Quantified NPs Inherently referring noun phrases pick out individuals in the world. e. g. John, Mary, the President, the department chair Non-referring noun phrases do not pick out an individual (or individuals) in the world. We will call these ‘quantified NPs’ or ‘operators’ e. g. No bear, every boy, all the students, each boy, who, two rabbits, some teacher, etc.

Types of Noun Phrases Referential vs. Quantified NPs Inherently referring noun phrases pick out individuals in the world. e. g. John, Mary, the President, the department chair Non-referring noun phrases do not pick out an individual (or individuals) in the world. We will call these ‘quantified NPs’ or ‘operators’ e. g. No bear, every boy, all the students, each boy, who, two rabbits, some teacher, etc.

![A Paradigm with a Missing Cell 1) 2) 3) 4) [No talk show host]i A Paradigm with a Missing Cell 1) 2) 3) 4) [No talk show host]i](https://present5.com/presentation/7d1758032f4eac3cc934b30f12afef73/image-2.jpg) A Paradigm with a Missing Cell 1) 2) 3) 4) [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himk [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himi [No talk show host]i admires himk *[No talk show host]i admires himi The phenomenon is the same for referential NP, e. g. , ‘Geraldo’ Example (4) cannot mean that no talk show host admires himself; it must mean that no talk show host admires some other male

A Paradigm with a Missing Cell 1) 2) 3) 4) [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himk [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himi [No talk show host]i admires himk *[No talk show host]i admires himi The phenomenon is the same for referential NP, e. g. , ‘Geraldo’ Example (4) cannot mean that no talk show host admires himself; it must mean that no talk show host admires some other male

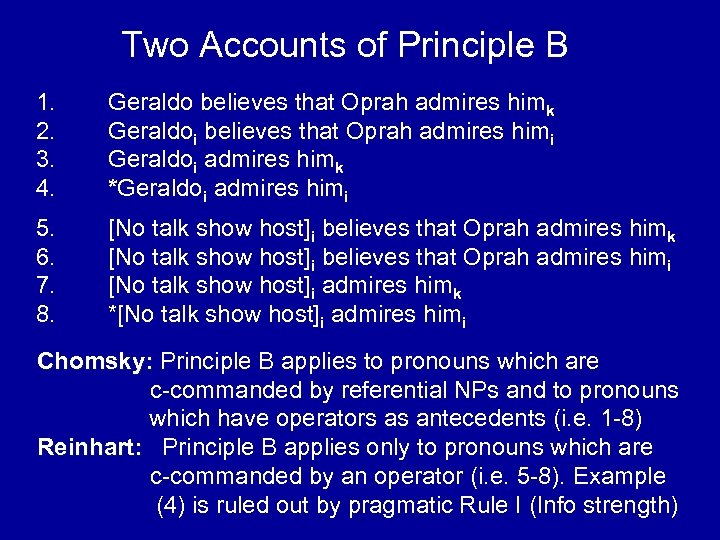

Two Accounts of Principle B 1. 2. 3. 4. Geraldo believes that Oprah admires himk Geraldoi believes that Oprah admires himi Geraldoi admires himk *Geraldoi admires himi 5. 6. 7. 8. [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himk [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himi [No talk show host]i admires himk *[No talk show host]i admires himi Chomsky: Principle B applies to pronouns which are c-commanded by referential NPs and to pronouns which have operators as antecedents (i. e. 1 -8) Reinhart: Principle B applies only to pronouns which are c-commanded by an operator (i. e. 5 -8). Example (4) is ruled out by pragmatic Rule I (Info strength)

Two Accounts of Principle B 1. 2. 3. 4. Geraldo believes that Oprah admires himk Geraldoi believes that Oprah admires himi Geraldoi admires himk *Geraldoi admires himi 5. 6. 7. 8. [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himk [No talk show host]i believes that Oprah admires himi [No talk show host]i admires himk *[No talk show host]i admires himi Chomsky: Principle B applies to pronouns which are c-commanded by referential NPs and to pronouns which have operators as antecedents (i. e. 1 -8) Reinhart: Principle B applies only to pronouns which are c-commanded by an operator (i. e. 5 -8). Example (4) is ruled out by pragmatic Rule I (Info strength)

The Experimental Findings Chien and Wexler (1990 Language Acquisition) Methodology: Picture-judgment task Results: First, children ‘appear’ to violate Principle B in sentences like ‘Mama Bear is touching her’, allowing the prohibited meaning, i. e. Mama Bear is touching herself about 50% of the time However, the same children do not violate Principle B when the antecedent of the pronoun is a quantified NP such as ‘every bear’. E. g. , Every bear is touching her is accepted only 15% of the time in a situation where every bear touches herself, but no bear touches another salient female who is depicted in the picture (say Goldilocks).

The Experimental Findings Chien and Wexler (1990 Language Acquisition) Methodology: Picture-judgment task Results: First, children ‘appear’ to violate Principle B in sentences like ‘Mama Bear is touching her’, allowing the prohibited meaning, i. e. Mama Bear is touching herself about 50% of the time However, the same children do not violate Principle B when the antecedent of the pronoun is a quantified NP such as ‘every bear’. E. g. , Every bear is touching her is accepted only 15% of the time in a situation where every bear touches herself, but no bear touches another salient female who is depicted in the picture (say Goldilocks).

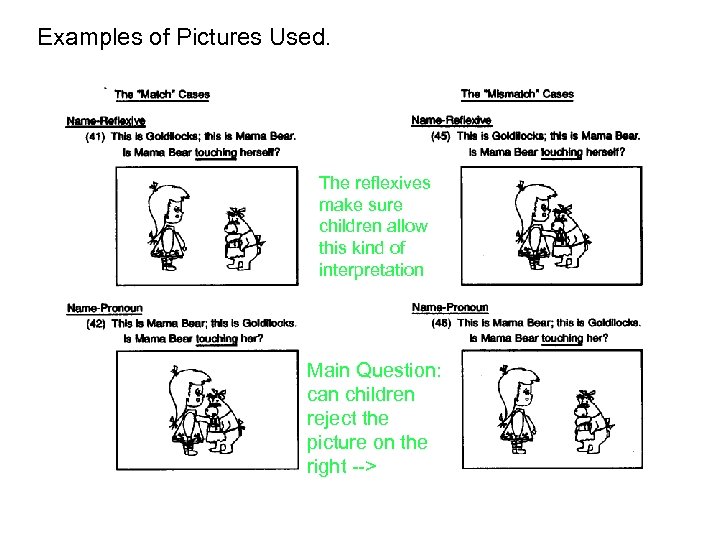

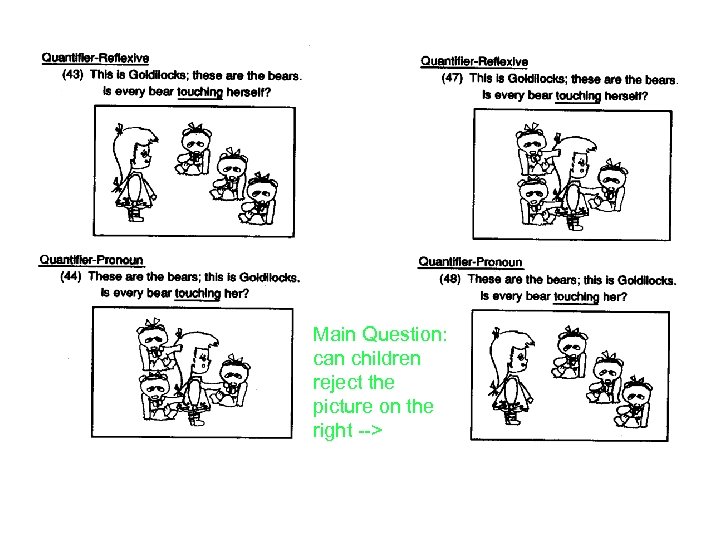

Examples of Pictures Used. The reflexives make sure children allow this kind of interpretation Main Question: can children reject the picture on the right -->

Examples of Pictures Used. The reflexives make sure children allow this kind of interpretation Main Question: can children reject the picture on the right -->

Main Question: can children reject the picture on the right -->

Main Question: can children reject the picture on the right -->

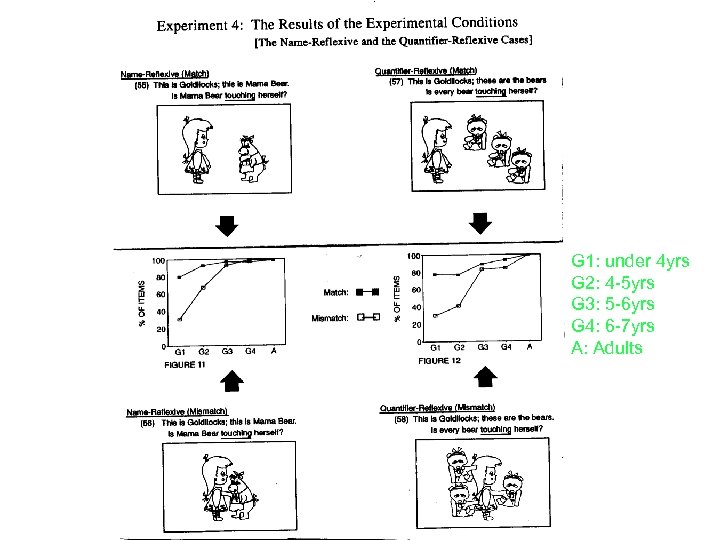

G 1: under 4 yrs G 2: 4 -5 yrs G 3: 5 -6 yrs G 4: 6 -7 yrs A: Adults

G 1: under 4 yrs G 2: 4 -5 yrs G 3: 5 -6 yrs G 4: 6 -7 yrs A: Adults

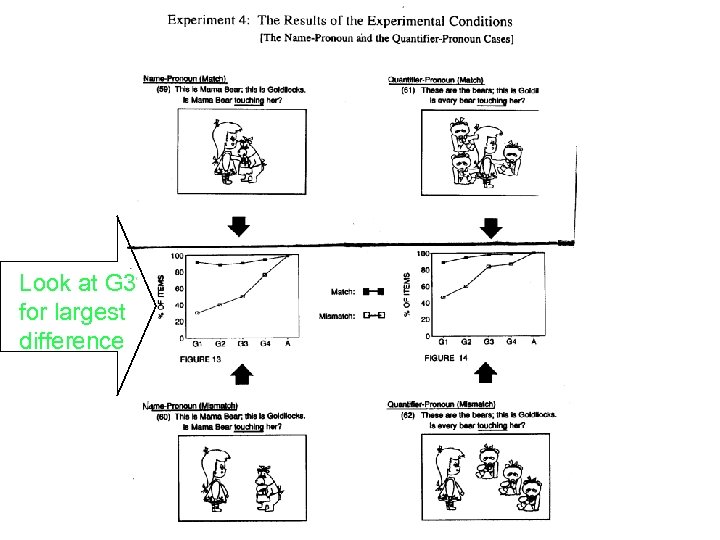

Look at G 3 for largest difference

Look at G 3 for largest difference

Summary of Chien and Wexler’s Findings In general, the youngest children didn’t perform well. It may be that the task is too hard for them, at least for some of the test sentences. Putting the youngest children (Groups 1 and 2) aside, however, children do pretty well with reflexives. They reject the mismatch sentence/picture pairs at high rates. Children also perform well with pronouns with a quantified NP as antecedent by 5 -6 years-old (Group 3), but these children still accept coreference for pronouns with a referential NP as antecedent.

Summary of Chien and Wexler’s Findings In general, the youngest children didn’t perform well. It may be that the task is too hard for them, at least for some of the test sentences. Putting the youngest children (Groups 1 and 2) aside, however, children do pretty well with reflexives. They reject the mismatch sentence/picture pairs at high rates. Children also perform well with pronouns with a quantified NP as antecedent by 5 -6 years-old (Group 3), but these children still accept coreference for pronouns with a referential NP as antecedent.

Picture Tasks Experiments using pictures can give us an idea about what’s going on in children’s grammars, although these experiments tend to underestimate children’s knowledge, as compared to experiments using the Truth Value Judgment task However, large numbers of subjects can be run, because the experiment is quick to carry out, though children don’t enjoy it. So, how would the results of Chien and Wexler’s experiment stand up -- if we switch to a TVJ task?

Picture Tasks Experiments using pictures can give us an idea about what’s going on in children’s grammars, although these experiments tend to underestimate children’s knowledge, as compared to experiments using the Truth Value Judgment task However, large numbers of subjects can be run, because the experiment is quick to carry out, though children don’t enjoy it. So, how would the results of Chien and Wexler’s experiment stand up -- if we switch to a TVJ task?

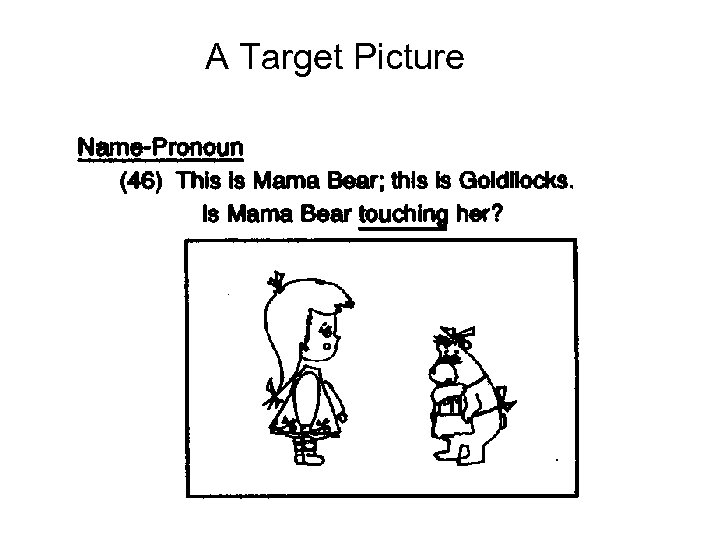

A Target Picture

A Target Picture

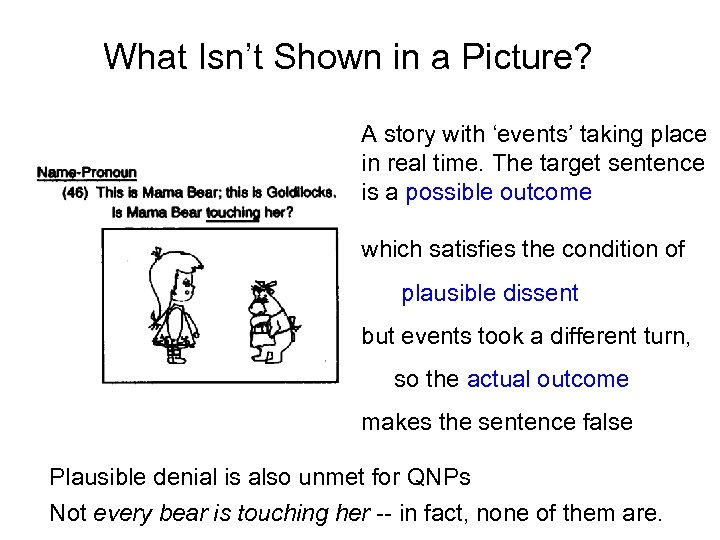

What Isn’t Shown in a Picture? A story with ‘events’ taking place in real time. The target sentence is a possible outcome which satisfies the condition of plausible dissent but events took a different turn, so the actual outcome makes the sentence false Plausible denial is also unmet for QNPs Not every bear is touching her -- in fact, none of them are.

What Isn’t Shown in a Picture? A story with ‘events’ taking place in real time. The target sentence is a possible outcome which satisfies the condition of plausible dissent but events took a different turn, so the actual outcome makes the sentence false Plausible denial is also unmet for QNPs Not every bear is touching her -- in fact, none of them are.

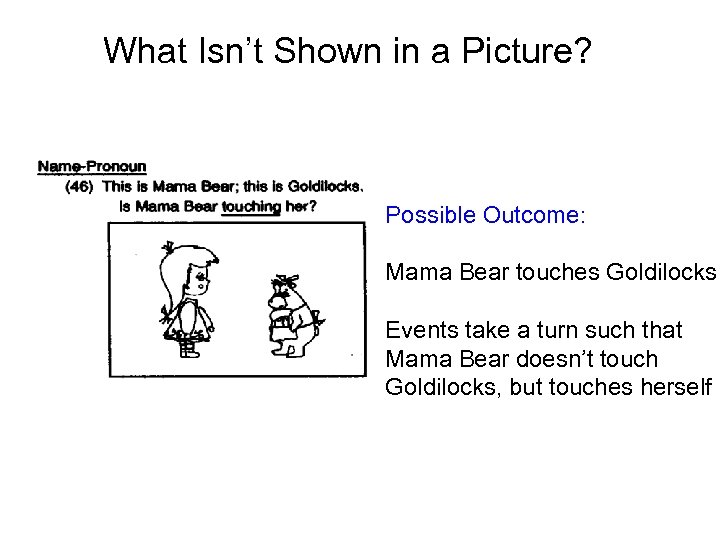

What Isn’t Shown in a Picture? Possible Outcome: Mama Bear touches Goldilocks Events take a turn such that Mama Bear doesn’t touch Goldilocks, but touches herself

What Isn’t Shown in a Picture? Possible Outcome: Mama Bear touches Goldilocks Events take a turn such that Mama Bear doesn’t touch Goldilocks, but touches herself

The TVJ task Background: Every troll dried so-and-so Assertion: Every troll dried a salient female character: Ariel Possible Outcome: Every troll dried Ariel. Actual Outcomes: Only one troll dried Ariel Every troll dried herself NB: there are other Background/Assertion pairs

The TVJ task Background: Every troll dried so-and-so Assertion: Every troll dried a salient female character: Ariel Possible Outcome: Every troll dried Ariel. Actual Outcomes: Only one troll dried Ariel Every troll dried herself NB: there are other Background/Assertion pairs

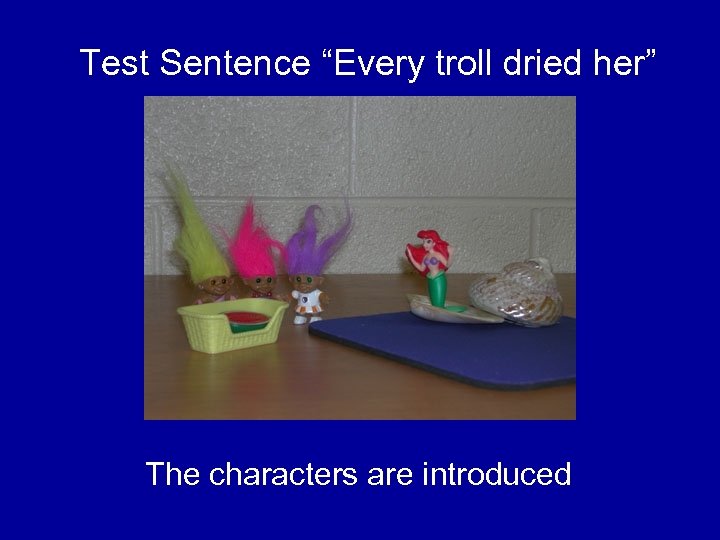

Test Sentence “Every troll dried her” The characters are introduced

Test Sentence “Every troll dried her” The characters are introduced

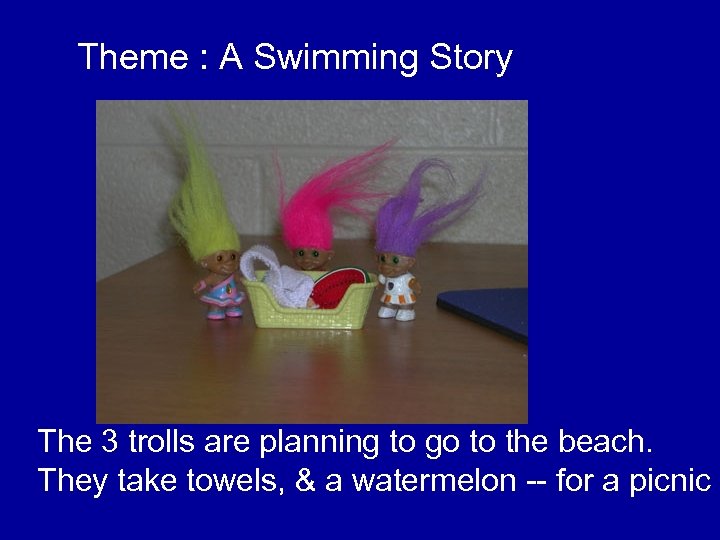

Theme : A Swimming Story The 3 trolls are planning to go to the beach. They take towels, & a watermelon -- for a picnic

Theme : A Swimming Story The 3 trolls are planning to go to the beach. They take towels, & a watermelon -- for a picnic

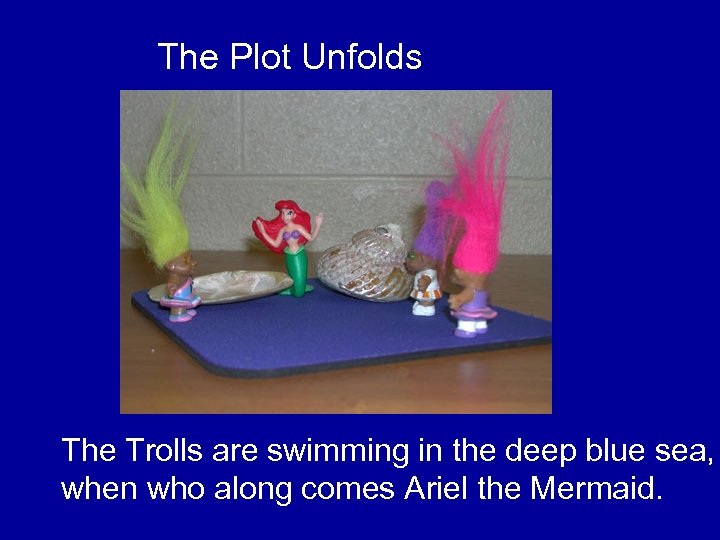

The Plot Unfolds The Trolls are swimming in the deep blue sea, when who along comes Ariel the Mermaid.

The Plot Unfolds The Trolls are swimming in the deep blue sea, when who along comes Ariel the Mermaid.

The Plot Unfolds The trolls invite Ariel to share the watermelon with them -- once they are all dried off. Ariel’s hair & tail are very wet.

The Plot Unfolds The trolls invite Ariel to share the watermelon with them -- once they are all dried off. Ariel’s hair & tail are very wet.

Potential Antecedent for the Pronoun Ariel accepts, but needs to dry off. “Can you trolls help. My hair is very wet, and so is my tail. ”

Potential Antecedent for the Pronoun Ariel accepts, but needs to dry off. “Can you trolls help. My hair is very wet, and so is my tail. ”

The Possible Outcome “Sure, we can help. We’ll go get our towels. ”

The Possible Outcome “Sure, we can help. We’ll go get our towels. ”

Possible Outcome Troll 1: “I have a big towel. I’ll dry your hair, and then I’ll get dry too. I’m still wet.

Possible Outcome Troll 1: “I have a big towel. I’ll dry your hair, and then I’ll get dry too. I’m still wet.

Possible Outcome Troll 1: ”Here you go Ariel. Now your hair is dry. ”

Possible Outcome Troll 1: ”Here you go Ariel. Now your hair is dry. ”

Condition of Falsification Troll 2: “Your tail is still wet. Oh look. I only brought a small towel. It’s not big enough to dry us both. And I’m wet too. ”

Condition of Falsification Troll 2: “Your tail is still wet. Oh look. I only brought a small towel. It’s not big enough to dry us both. And I’m wet too. ”

Possible Outcome becomes Untenable Troll 3: “I can’t help either. Your wet tail will soak my little towel, and I need it to dry off. ”

Possible Outcome becomes Untenable Troll 3: “I can’t help either. Your wet tail will soak my little towel, and I need it to dry off. ”

The Actual Outcome: & Reminder Troll 1: “Now I feel better”

The Actual Outcome: & Reminder Troll 1: “Now I feel better”

The Story Ends Let’s have watermelon together now. (The towels are still next to the Trolls. )

The Story Ends Let’s have watermelon together now. (The towels are still next to the Trolls. )

The Linguistic Antecedent “That was a story about Ariel and some girl trolls. And I know one thing that happened. Every troll dried her. ”

The Linguistic Antecedent “That was a story about Ariel and some girl trolls. And I know one thing that happened. Every troll dried her. ”

The Truth Value Judgment Child: “No. ” Kermit: “No? What really happened? ” Child: “Only one troll dried her. ”

The Truth Value Judgment Child: “No. ” Kermit: “No? What really happened? ” Child: “Only one troll dried her. ”

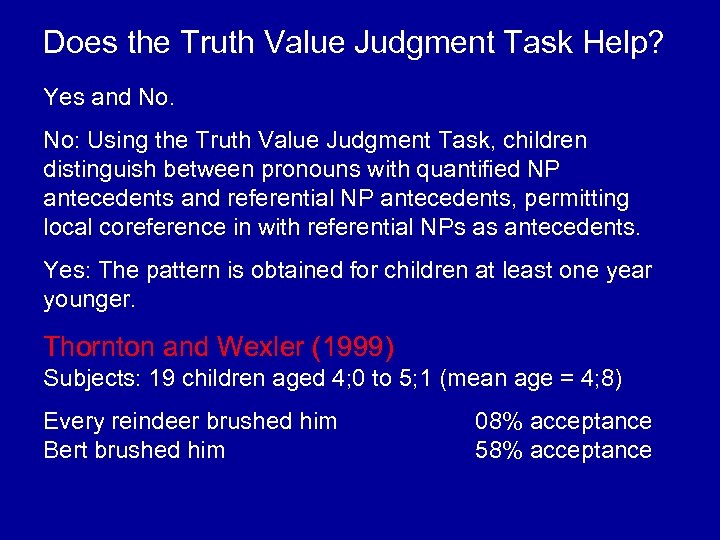

Does the Truth Value Judgment Task Help? Yes and No. No: Using the Truth Value Judgment Task, children distinguish between pronouns with quantified NP antecedents and referential NP antecedents, permitting local coreference in with referential NPs as antecedents. Yes: The pattern is obtained for children at least one year younger. Thornton and Wexler (1999) Subjects: 19 children aged 4; 0 to 5; 1 (mean age = 4; 8) Every reindeer brushed him Bert brushed him 08% acceptance 58% acceptance

Does the Truth Value Judgment Task Help? Yes and No. No: Using the Truth Value Judgment Task, children distinguish between pronouns with quantified NP antecedents and referential NP antecedents, permitting local coreference in with referential NPs as antecedents. Yes: The pattern is obtained for children at least one year younger. Thornton and Wexler (1999) Subjects: 19 children aged 4; 0 to 5; 1 (mean age = 4; 8) Every reindeer brushed him Bert brushed him 08% acceptance 58% acceptance

Parameter Setting: Null Subjects

Parameter Setting: Null Subjects

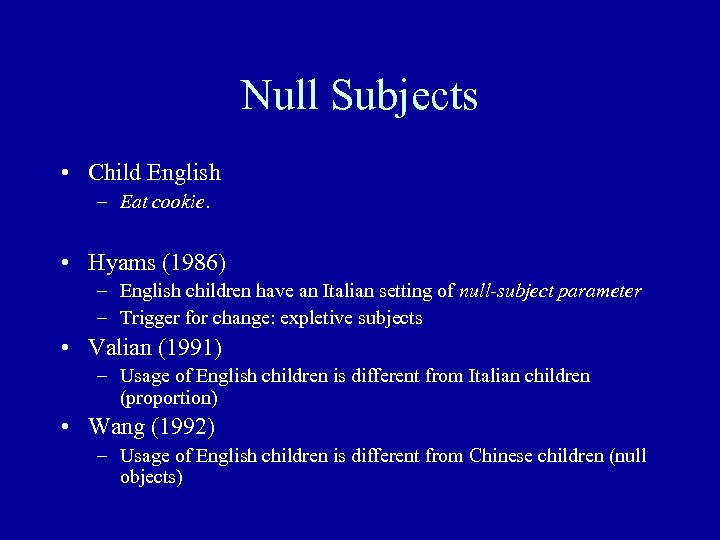

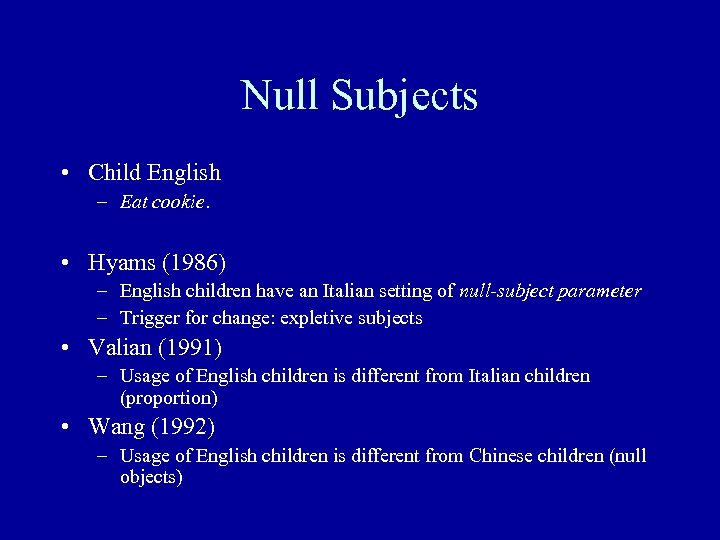

Null Subjects • Child English – Eat cookie. • Hyams (1986) – English children have an Italian setting of null-subject parameter – Trigger for change: expletive subjects • Valian (1991) – Usage of English children is different from Italian children (proportion) • Wang (1992) – Usage of English children is different from Chinese children (null objects)

Null Subjects • Child English – Eat cookie. • Hyams (1986) – English children have an Italian setting of null-subject parameter – Trigger for change: expletive subjects • Valian (1991) – Usage of English children is different from Italian children (proportion) • Wang (1992) – Usage of English children is different from Chinese children (null objects)

Parameter Setting: Complex Predicates (Snyder 2001)

Parameter Setting: Complex Predicates (Snyder 2001)

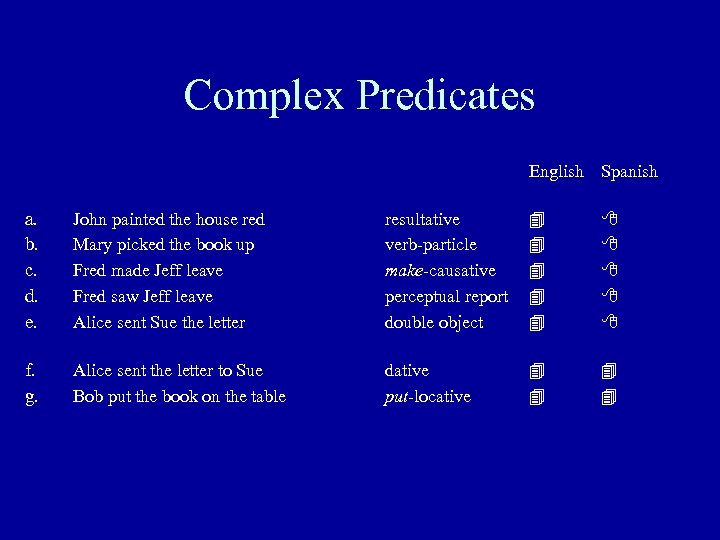

Complex Predicates English Spanish a. b. c. d. e. John painted the house red Mary picked the book up Fred made Jeff leave Fred saw Jeff leave Alice sent Sue the letter resultative verb-particle make-causative perceptual report double object f. g. Alice sent the letter to Sue Bob put the book on the table dative put-locative

Complex Predicates English Spanish a. b. c. d. e. John painted the house red Mary picked the book up Fred made Jeff leave Fred saw Jeff leave Alice sent Sue the letter resultative verb-particle make-causative perceptual report double object f. g. Alice sent the letter to Sue Bob put the book on the table dative put-locative

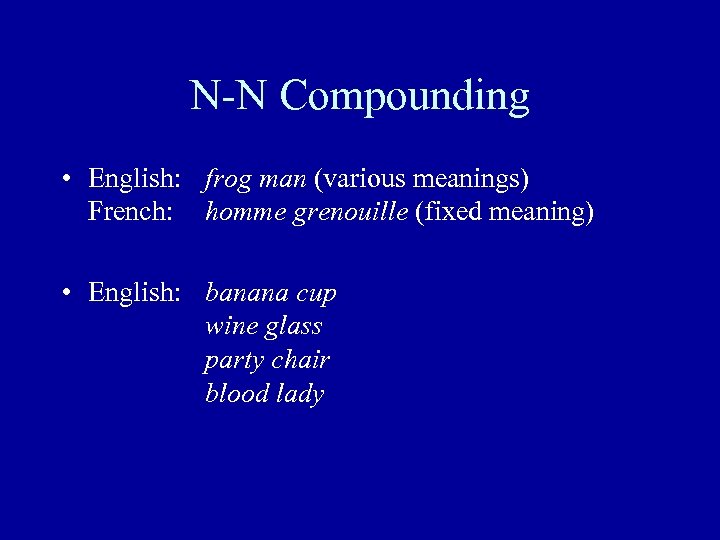

N-N Compounding • English: frog man (various meanings) French: homme grenouille (fixed meaning) • English: banana cup wine glass party chair blood lady

N-N Compounding • English: frog man (various meanings) French: homme grenouille (fixed meaning) • English: banana cup wine glass party chair blood lady

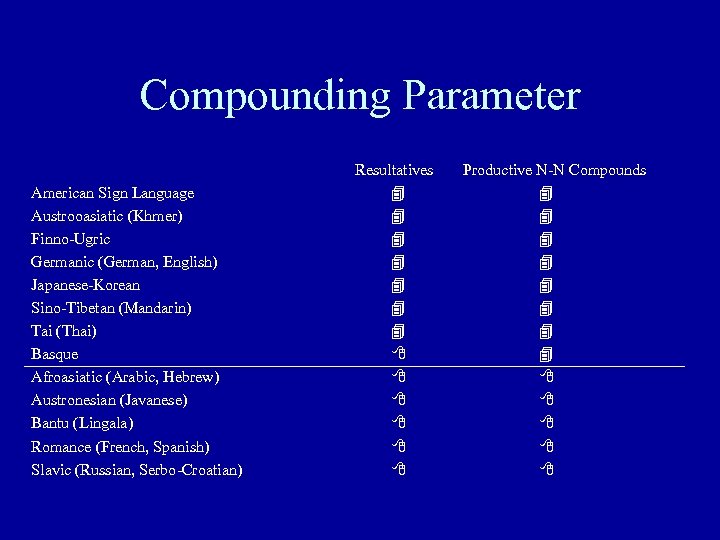

Compounding Parameter American Sign Language Austrooasiatic (Khmer) Finno-Ugric Germanic (German, English) Japanese-Korean Sino-Tibetan (Mandarin) Tai (Thai) Basque Afroasiatic (Arabic, Hebrew) Austronesian (Javanese) Bantu (Lingala) Romance (French, Spanish) Slavic (Russian, Serbo-Croatian) Resultatives Productive N-N Compounds

Compounding Parameter American Sign Language Austrooasiatic (Khmer) Finno-Ugric Germanic (German, English) Japanese-Korean Sino-Tibetan (Mandarin) Tai (Thai) Basque Afroasiatic (Arabic, Hebrew) Austronesian (Javanese) Bantu (Lingala) Romance (French, Spanish) Slavic (Russian, Serbo-Croatian) Resultatives Productive N-N Compounds

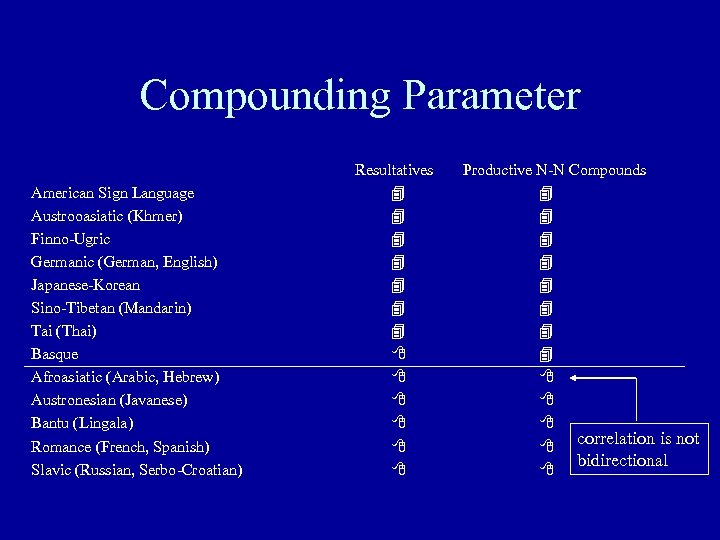

Compounding Parameter American Sign Language Austrooasiatic (Khmer) Finno-Ugric Germanic (German, English) Japanese-Korean Sino-Tibetan (Mandarin) Tai (Thai) Basque Afroasiatic (Arabic, Hebrew) Austronesian (Javanese) Bantu (Lingala) Romance (French, Spanish) Slavic (Russian, Serbo-Croatian) Resultatives Productive N-N Compounds correlation is not bidirectional

Compounding Parameter American Sign Language Austrooasiatic (Khmer) Finno-Ugric Germanic (German, English) Japanese-Korean Sino-Tibetan (Mandarin) Tai (Thai) Basque Afroasiatic (Arabic, Hebrew) Austronesian (Javanese) Bantu (Lingala) Romance (French, Spanish) Slavic (Russian, Serbo-Croatian) Resultatives Productive N-N Compounds correlation is not bidirectional

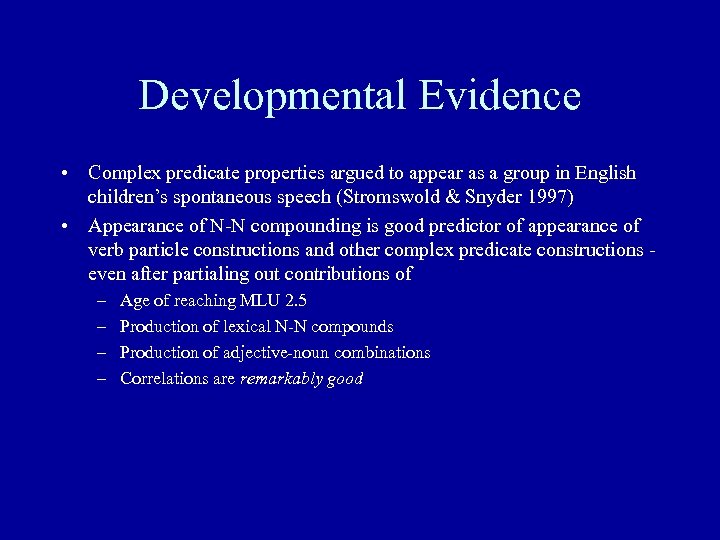

Developmental Evidence • Complex predicate properties argued to appear as a group in English children’s spontaneous speech (Stromswold & Snyder 1997) • Appearance of N-N compounding is good predictor of appearance of verb particle constructions and other complex predicate constructions even after partialing out contributions of – – Age of reaching MLU 2. 5 Production of lexical N-N compounds Production of adjective-noun combinations Correlations are remarkably good

Developmental Evidence • Complex predicate properties argued to appear as a group in English children’s spontaneous speech (Stromswold & Snyder 1997) • Appearance of N-N compounding is good predictor of appearance of verb particle constructions and other complex predicate constructions even after partialing out contributions of – – Age of reaching MLU 2. 5 Production of lexical N-N compounds Production of adjective-noun combinations Correlations are remarkably good

Language Change: Learning about Verbs

Language Change: Learning about Verbs

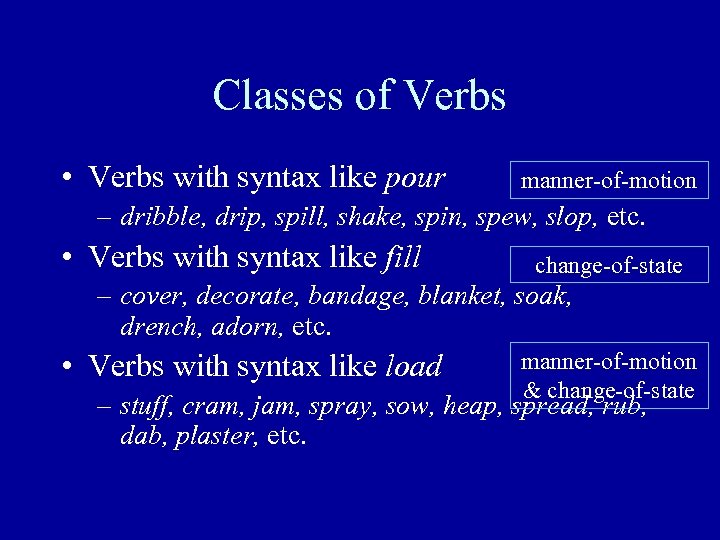

Classes of Verbs • Verbs with syntax like pour manner-of-motion – dribble, drip, spill, shake, spin, spew, slop, etc. • Verbs with syntax like fill change-of-state – cover, decorate, bandage, blanket, soak, drench, adorn, etc. • Verbs with syntax like load manner-of-motion & change-of-state – stuff, cram, jam, spray, sow, heap, spread, rub, dab, plaster, etc.

Classes of Verbs • Verbs with syntax like pour manner-of-motion – dribble, drip, spill, shake, spin, spew, slop, etc. • Verbs with syntax like fill change-of-state – cover, decorate, bandage, blanket, soak, drench, adorn, etc. • Verbs with syntax like load manner-of-motion & change-of-state – stuff, cram, jam, spray, sow, heap, spread, rub, dab, plaster, etc.

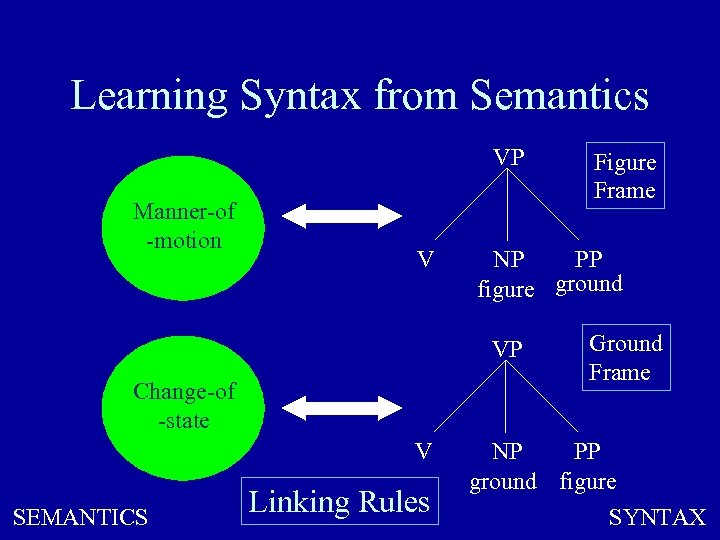

Learning Syntax from Semantics VP Manner-of -motion V NP PP figure ground VP Change-of -state V SEMANTICS Linking Rules Figure Frame Ground Frame NP PP ground figure SYNTAX

Learning Syntax from Semantics VP Manner-of -motion V NP PP figure ground VP Change-of -state V SEMANTICS Linking Rules Figure Frame Ground Frame NP PP ground figure SYNTAX

• Assumption: linking generalizations are universal • Shared by competing accounts of learning verb syntax & semantics

• Assumption: linking generalizations are universal • Shared by competing accounts of learning verb syntax & semantics

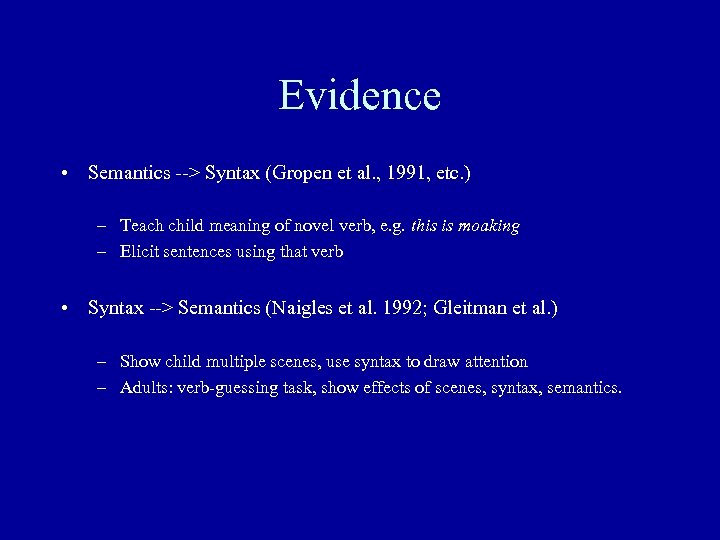

Evidence • Semantics --> Syntax (Gropen et al. , 1991, etc. ) – Teach child meaning of novel verb, e. g. this is moaking – Elicit sentences using that verb • Syntax --> Semantics (Naigles et al. 1992; Gleitman et al. ) – Show child multiple scenes, use syntax to draw attention – Adults: verb-guessing task, show effects of scenes, syntax, semantics.

Evidence • Semantics --> Syntax (Gropen et al. , 1991, etc. ) – Teach child meaning of novel verb, e. g. this is moaking – Elicit sentences using that verb • Syntax --> Semantics (Naigles et al. 1992; Gleitman et al. ) – Show child multiple scenes, use syntax to draw attention – Adults: verb-guessing task, show effects of scenes, syntax, semantics.

Language Change Theoretical Approaches

Language Change Theoretical Approaches

Language Change • How to take input and reach a new grammar – Error signal • Failure to analyze input • Failure to predict input – Cues • Syntactic • Non-syntactic • How do any of these deal with problem of overgeneralization?

Language Change • How to take input and reach a new grammar – Error signal • Failure to analyze input • Failure to predict input – Cues • Syntactic • Non-syntactic • How do any of these deal with problem of overgeneralization?

Triggers

Triggers

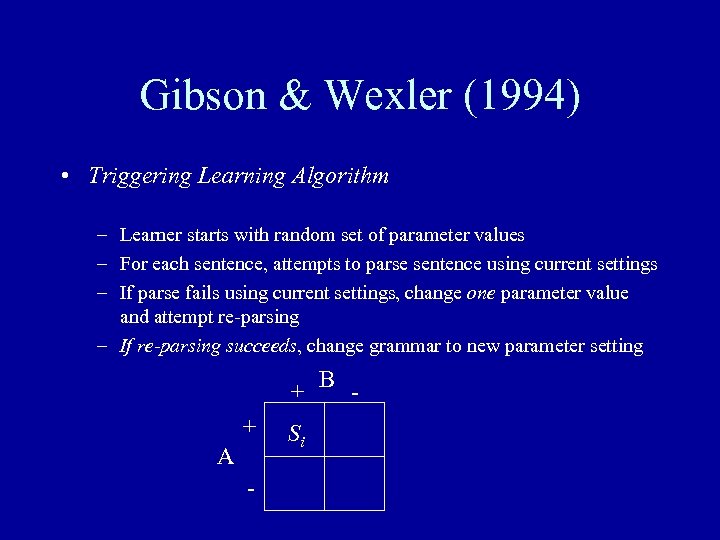

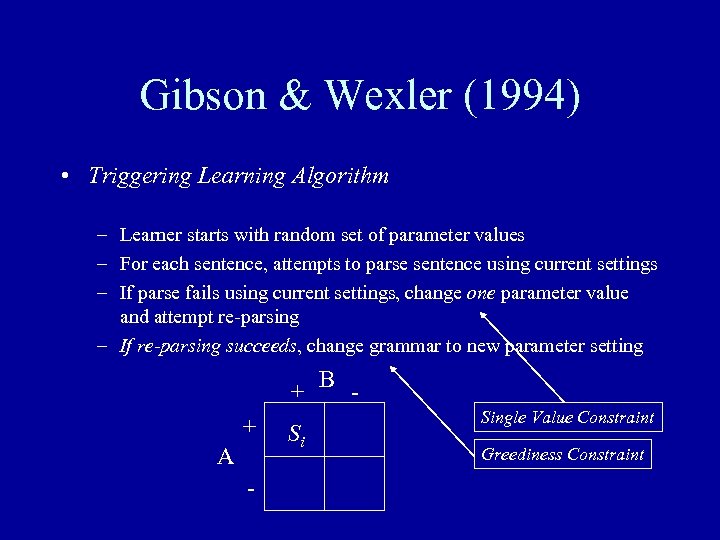

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Triggering Learning Algorithm – Learner starts with random set of parameter values – For each sentence, attempts to parse sentence using current settings – If parse fails using current settings, change one parameter value and attempt re-parsing – If re-parsing succeeds, change grammar to new parameter setting + B + A - Si

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Triggering Learning Algorithm – Learner starts with random set of parameter values – For each sentence, attempts to parse sentence using current settings – If parse fails using current settings, change one parameter value and attempt re-parsing – If re-parsing succeeds, change grammar to new parameter setting + B + A - Si

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Triggering Learning Algorithm – Learner starts with random set of parameter values – For each sentence, attempts to parse sentence using current settings – If parse fails using current settings, change one parameter value and attempt re-parsing – If re-parsing succeeds, change grammar to new parameter setting + B + A - Si Single Value Constraint Greediness Constraint

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Triggering Learning Algorithm – Learner starts with random set of parameter values – For each sentence, attempts to parse sentence using current settings – If parse fails using current settings, change one parameter value and attempt re-parsing – If re-parsing succeeds, change grammar to new parameter setting + B + A - Si Single Value Constraint Greediness Constraint

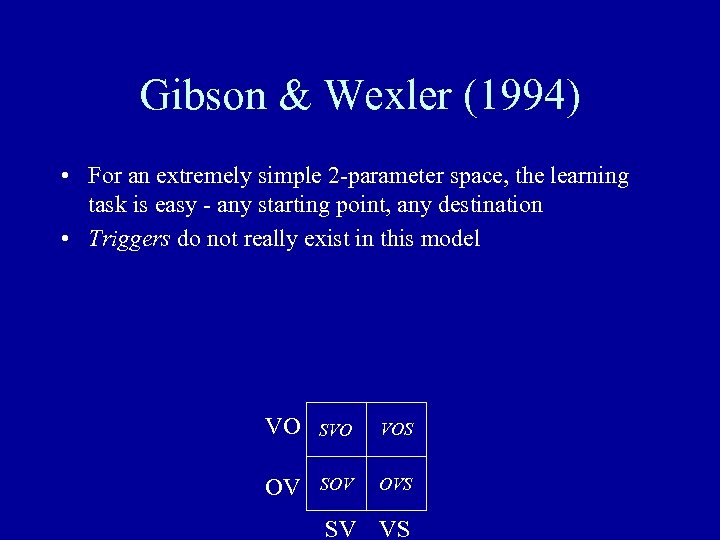

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • For an extremely simple 2 -parameter space, the learning task is easy - any starting point, any destination • Triggers do not really exist in this model VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • For an extremely simple 2 -parameter space, the learning task is easy - any starting point, any destination • Triggers do not really exist in this model VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS

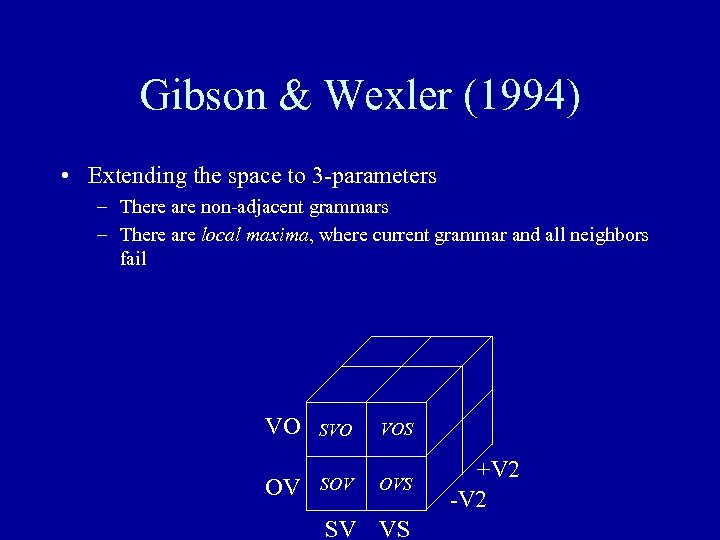

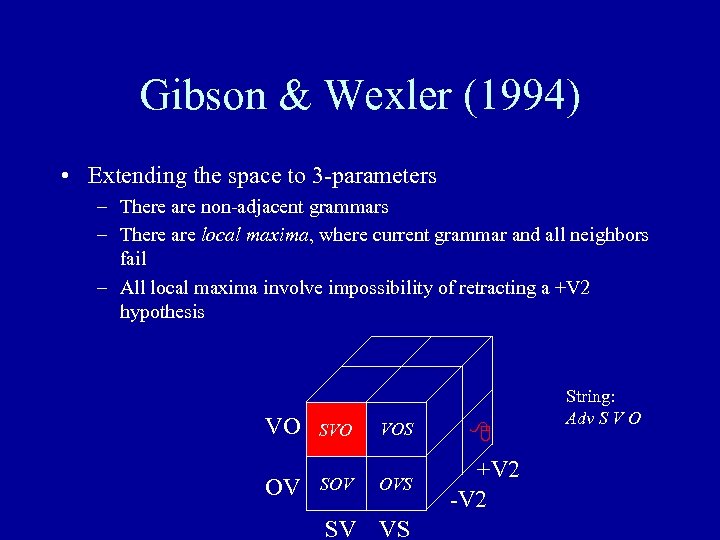

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2

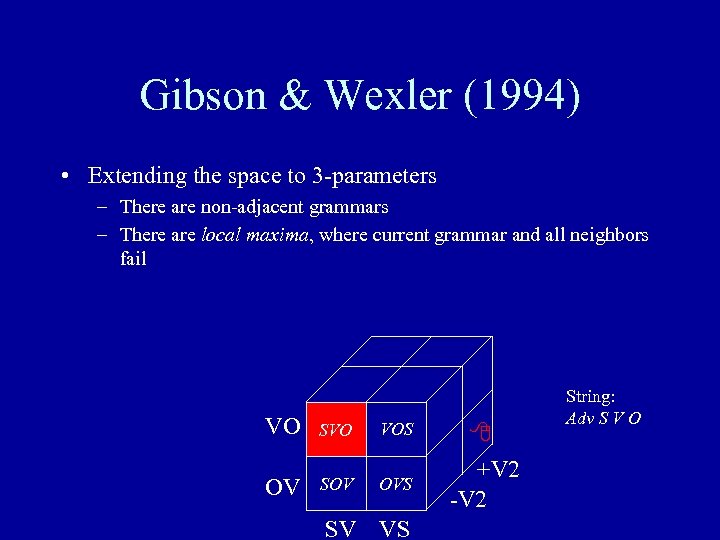

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail – All local maxima involve impossibility of retracting a +V 2 hypothesis VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Extending the space to 3 -parameters – There are non-adjacent grammars – There are local maxima, where current grammar and all neighbors fail – All local maxima involve impossibility of retracting a +V 2 hypothesis VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

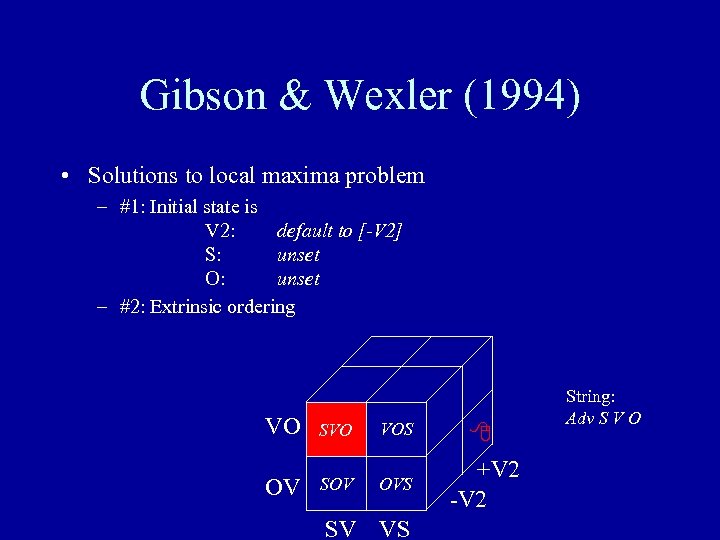

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Solutions to local maxima problem – #1: Initial state is V 2: default to [-V 2] S: unset O: unset – #2: Extrinsic ordering VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

Gibson & Wexler (1994) • Solutions to local maxima problem – #1: Initial state is V 2: default to [-V 2] S: unset O: unset – #2: Extrinsic ordering VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS SV VS +V 2 -V 2 String: Adv S V O

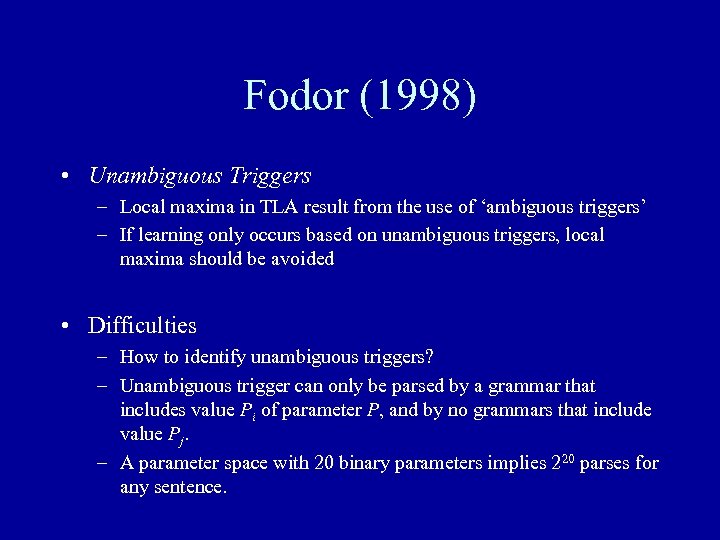

Fodor (1998) • Unambiguous Triggers – Local maxima in TLA result from the use of ‘ambiguous triggers’ – If learning only occurs based on unambiguous triggers, local maxima should be avoided • Difficulties – How to identify unambiguous triggers? – Unambiguous trigger can only be parsed by a grammar that includes value Pi of parameter P, and by no grammars that include value Pj. – A parameter space with 20 binary parameters implies 220 parses for any sentence.

Fodor (1998) • Unambiguous Triggers – Local maxima in TLA result from the use of ‘ambiguous triggers’ – If learning only occurs based on unambiguous triggers, local maxima should be avoided • Difficulties – How to identify unambiguous triggers? – Unambiguous trigger can only be parsed by a grammar that includes value Pi of parameter P, and by no grammars that include value Pj. – A parameter space with 20 binary parameters implies 220 parses for any sentence.

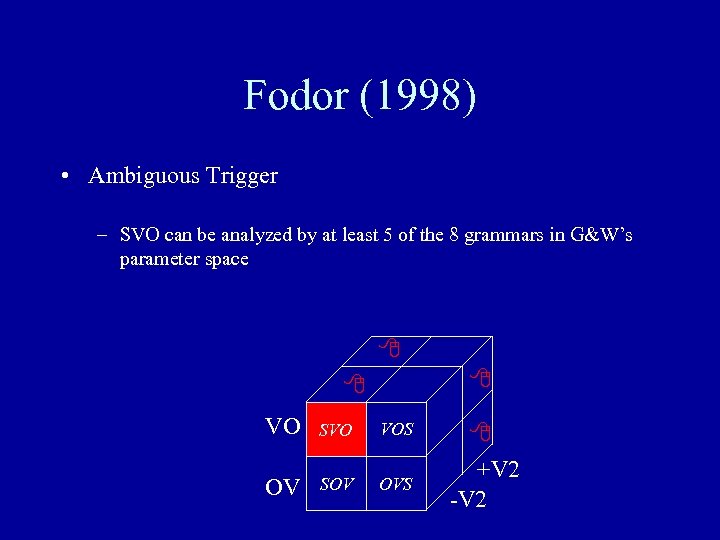

Fodor (1998) • Ambiguous Trigger – SVO can be analyzed by at least 5 of the 8 grammars in G&W’s parameter space VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS +V 2 -V 2

Fodor (1998) • Ambiguous Trigger – SVO can be analyzed by at least 5 of the 8 grammars in G&W’s parameter space VO SVO VOS OV SOV OVS +V 2 -V 2

Fodor (1998) • Structural Triggers Learner (STL) – Parameters are treelets – Learner attempts to parse input sentences using supergrammar, that contains treelets for all values of all unset parameters, e. g. , 40 treelets for 20 unset binary parameters. – Algorithm • #1: Adopt a parameter value/trigger structure if and only if it occurs as a part of every complete well-formed phrase marker assigned to an input sentence by the parser using the supergrammar. • #2: Adopt a parameter value/trigger structure if and only if it occurs as a part of a unique complete well-formed phrase marker assigned to the input by the parser using the supergrammar.

Fodor (1998) • Structural Triggers Learner (STL) – Parameters are treelets – Learner attempts to parse input sentences using supergrammar, that contains treelets for all values of all unset parameters, e. g. , 40 treelets for 20 unset binary parameters. – Algorithm • #1: Adopt a parameter value/trigger structure if and only if it occurs as a part of every complete well-formed phrase marker assigned to an input sentence by the parser using the supergrammar. • #2: Adopt a parameter value/trigger structure if and only if it occurs as a part of a unique complete well-formed phrase marker assigned to the input by the parser using the supergrammar.

Fodor (1998) • Structural Triggers Learner – If a sentence is structurally ambiguous, it is taken to be uninformative (slightly wasteful, but conservative) – Unable to take advantage of collectively unambiguous sets of sentences, e. g. SVO and OVS, which entail [+V 2] – Still unclear (to me) how it manages its parsing task

Fodor (1998) • Structural Triggers Learner – If a sentence is structurally ambiguous, it is taken to be uninformative (slightly wasteful, but conservative) – Unable to take advantage of collectively unambiguous sets of sentences, e. g. SVO and OVS, which entail [+V 2] – Still unclear (to me) how it manages its parsing task

Competition Model • 2 grammars - start with even strength, both get credit for success, one gets punished for failure • Each grammar is chosen for parsing/production as a function of its current strength • Must be that increasing Pi for one grammar decreases Pj for other grammars • Is it the case that the presence of some punishment will guarantee that a grammar will, over time, always fail to survive?

Competition Model • 2 grammars - start with even strength, both get credit for success, one gets punished for failure • Each grammar is chosen for parsing/production as a function of its current strength • Must be that increasing Pi for one grammar decreases Pj for other grammars • Is it the case that the presence of some punishment will guarantee that a grammar will, over time, always fail to survive?

Competition Model • Upon the presence of an input datum s, the child – Selects a grammar Gi with the probability pi. – Analyzes s with Gi. – Updates competition • If successful, reward Gi by increasing pi. • Otherwise, punish Gi by decreasing pi. • This implies that change only occurs when a selected grammar succeeds or fails

Competition Model • Upon the presence of an input datum s, the child – Selects a grammar Gi with the probability pi. – Analyzes s with Gi. – Updates competition • If successful, reward Gi by increasing pi. • Otherwise, punish Gi by decreasing pi. • This implies that change only occurs when a selected grammar succeeds or fails

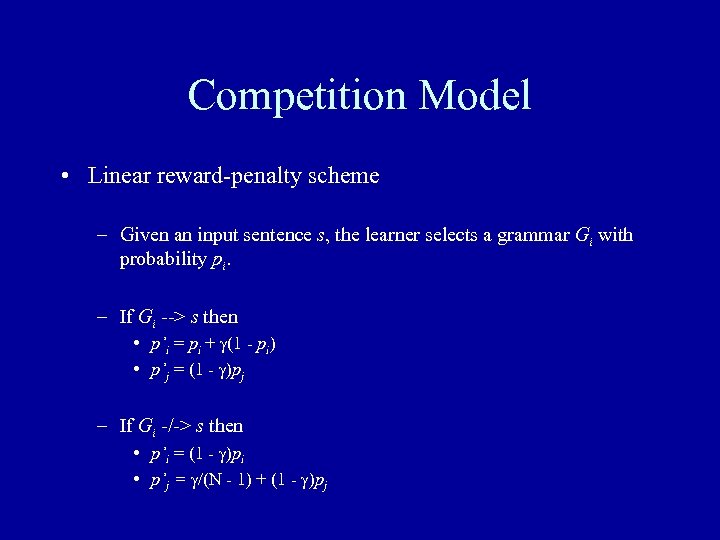

Competition Model • Linear reward-penalty scheme – Given an input sentence s, the learner selects a grammar Gi with probability pi. – If Gi --> s then • p’i = pi + (1 - pi) • p’j = (1 - )pj – If Gi -/-> s then • p’i = (1 - )pi • p’j = /(N - 1) + (1 - )pj

Competition Model • Linear reward-penalty scheme – Given an input sentence s, the learner selects a grammar Gi with probability pi. – If Gi --> s then • p’i = pi + (1 - pi) • p’j = (1 - )pj – If Gi -/-> s then • p’i = (1 - )pi • p’j = /(N - 1) + (1 - )pj

From Grammars to Parameters • Number of Grammars problem – Space with n parameters implies at least 2 n grammars (e. g. 240 is ~1 trillion) – Only one grammar is used at a time, so implies very slow convergence • Competition among Parameter Values – How does this work? – Naïve Parameter Learning model (NPL) may reward incorrect parameter values as hitchhikers, or punish correct parameter values as accomplices.

From Grammars to Parameters • Number of Grammars problem – Space with n parameters implies at least 2 n grammars (e. g. 240 is ~1 trillion) – Only one grammar is used at a time, so implies very slow convergence • Competition among Parameter Values – How does this work? – Naïve Parameter Learning model (NPL) may reward incorrect parameter values as hitchhikers, or punish correct parameter values as accomplices.

Empirical Predictions • Hypothesis Time to settle upon target grammar is a function of the frequency of sentences that punish the competitor grammars • First-pass assumptions – Learning rate set low, so many occurrences needed to lead to decisive changes – Similar amount of input needed to eliminate all competitors

Empirical Predictions • Hypothesis Time to settle upon target grammar is a function of the frequency of sentences that punish the competitor grammars • First-pass assumptions – Learning rate set low, so many occurrences needed to lead to decisive changes – Similar amount of input needed to eliminate all competitors

![Empirical Predictions • ±wh-movement – Any occurrence of overt wh-movement punishes a [-wh-mvt] grammar Empirical Predictions • ±wh-movement – Any occurrence of overt wh-movement punishes a [-wh-mvt] grammar](https://present5.com/presentation/7d1758032f4eac3cc934b30f12afef73/image-63.jpg) Empirical Predictions • ±wh-movement – Any occurrence of overt wh-movement punishes a [-wh-mvt] grammar – Wh-questions are highly frequent in input to English-speaking children (~30% estimate!) – [±wh-mvt] parameter should be set very early – This applies to clear-cut contrast between English and Chinese • French: [+wh-movement] and lots of wh-in-situ • Japanese: [-wh-movement] plus scrambling

Empirical Predictions • ±wh-movement – Any occurrence of overt wh-movement punishes a [-wh-mvt] grammar – Wh-questions are highly frequent in input to English-speaking children (~30% estimate!) – [±wh-mvt] parameter should be set very early – This applies to clear-cut contrast between English and Chinese • French: [+wh-movement] and lots of wh-in-situ • Japanese: [-wh-movement] plus scrambling

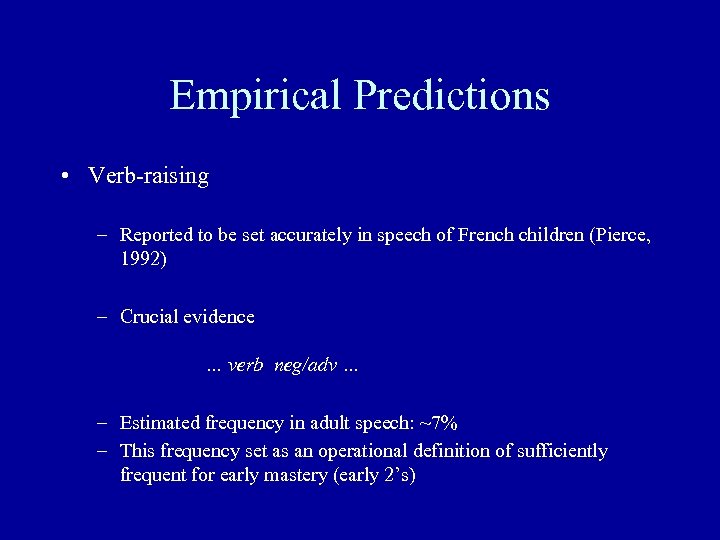

Empirical Predictions • Verb-raising – Reported to be set accurately in speech of French children (Pierce, 1992)

Empirical Predictions • Verb-raising – Reported to be set accurately in speech of French children (Pierce, 1992)

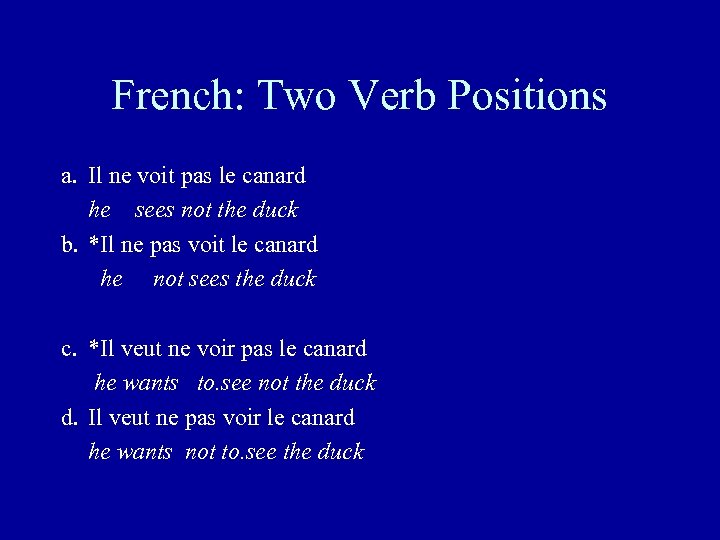

French: Two Verb Positions a. Il ne voit pas le canard he sees not the duck b. *Il ne pas voit le canard he not sees the duck c. *Il veut ne voir pas le canard he wants to. see not the duck d. Il veut ne pas voir le canard he wants not to. see the duck

French: Two Verb Positions a. Il ne voit pas le canard he sees not the duck b. *Il ne pas voit le canard he not sees the duck c. *Il veut ne voir pas le canard he wants to. see not the duck d. Il veut ne pas voir le canard he wants not to. see the duck

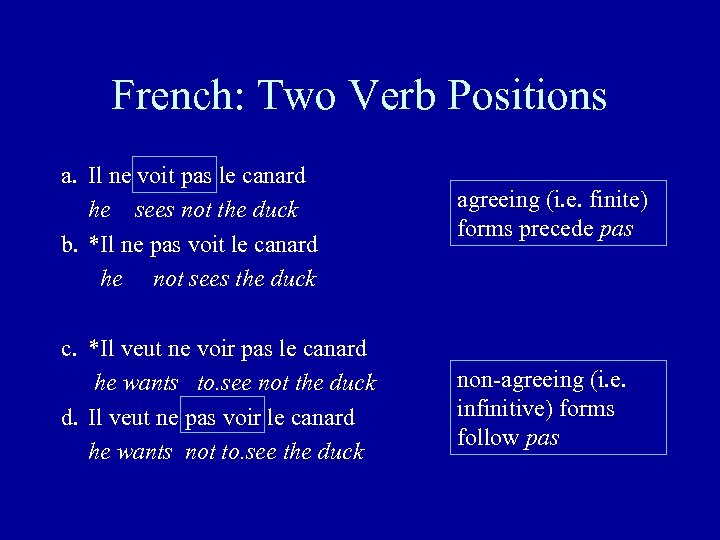

French: Two Verb Positions a. Il ne voit pas le canard he sees not the duck b. *Il ne pas voit le canard he not sees the duck c. *Il veut ne voir pas le canard he wants to. see not the duck d. Il veut ne pas voir le canard he wants not to. see the duck agreeing (i. e. finite) forms precede pas non-agreeing (i. e. infinitive) forms follow pas

French: Two Verb Positions a. Il ne voit pas le canard he sees not the duck b. *Il ne pas voit le canard he not sees the duck c. *Il veut ne voir pas le canard he wants to. see not the duck d. Il veut ne pas voir le canard he wants not to. see the duck agreeing (i. e. finite) forms precede pas non-agreeing (i. e. infinitive) forms follow pas

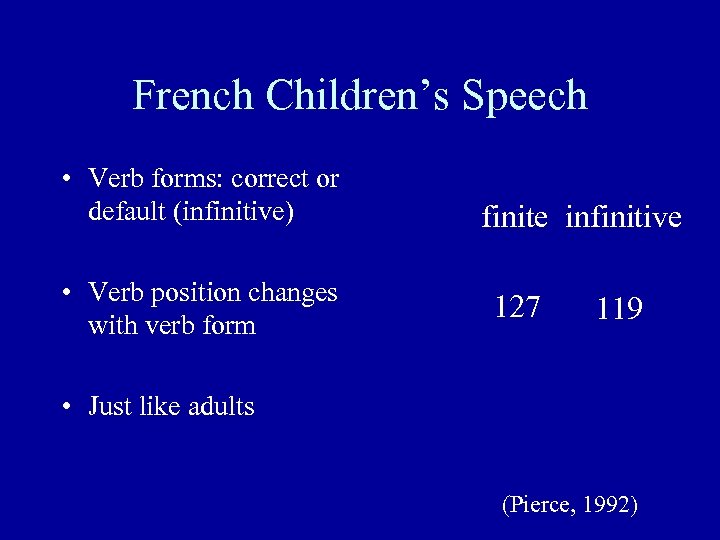

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive 127 119 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive 127 119 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

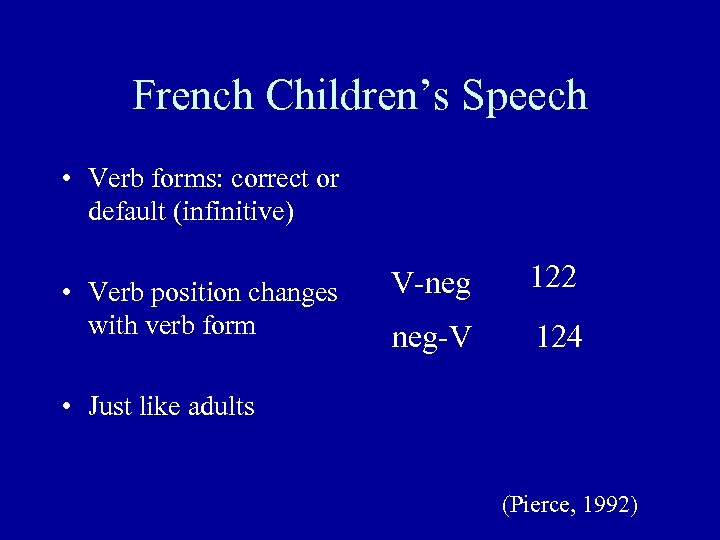

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form V-neg 122 neg-V 124 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form V-neg 122 neg-V 124 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

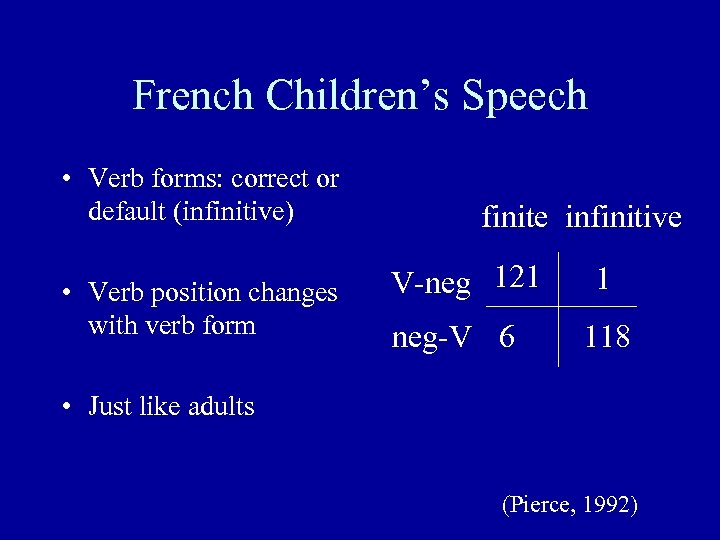

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive V-neg 121 neg-V 6 1 118 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

French Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive V-neg 121 neg-V 6 1 118 • Just like adults (Pierce, 1992)

Empirical Predictions • Verb-raising – Reported to be set accurately in speech of French children (Pierce, 1992) – Crucial evidence … verb neg/adv … – Estimated frequency in adult speech: ~7% – This frequency set as an operational definition of sufficiently frequent for early mastery (early 2’s)

Empirical Predictions • Verb-raising – Reported to be set accurately in speech of French children (Pierce, 1992) – Crucial evidence … verb neg/adv … – Estimated frequency in adult speech: ~7% – This frequency set as an operational definition of sufficiently frequent for early mastery (early 2’s)

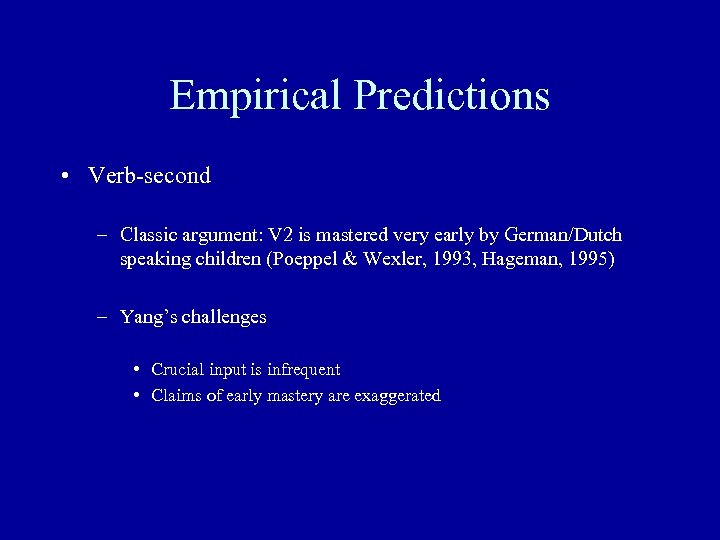

Empirical Predictions • Verb-second – Classic argument: V 2 is mastered very early by German/Dutch speaking children (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993, Hageman, 1995) – Yang’s challenges • Crucial input is infrequent • Claims of early mastery are exaggerated

Empirical Predictions • Verb-second – Classic argument: V 2 is mastered very early by German/Dutch speaking children (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993, Hageman, 1995) – Yang’s challenges • Crucial input is infrequent • Claims of early mastery are exaggerated

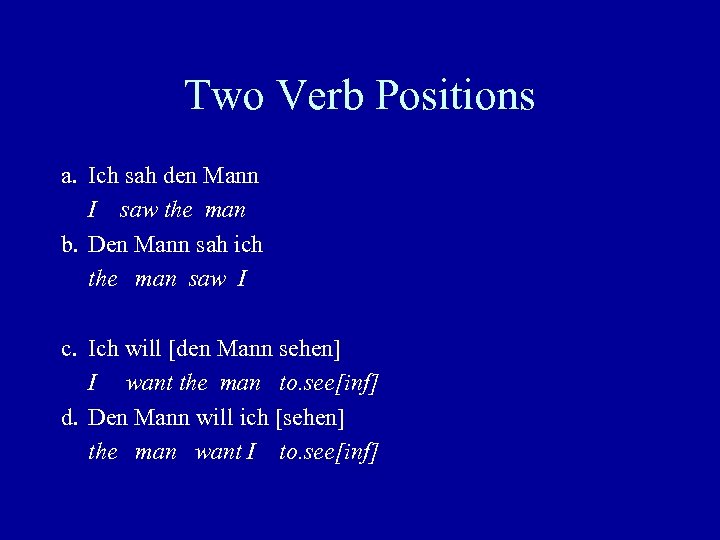

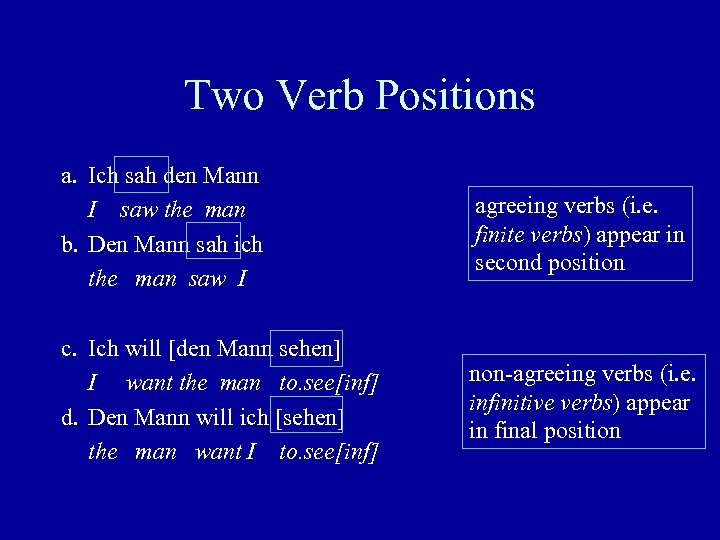

Two Verb Positions a. Ich sah den Mann I saw the man b. Den Mann sah ich the man saw I c. Ich will [den Mann sehen] I want the man to. see[inf] d. Den Mann will ich [sehen] the man want I to. see[inf]

Two Verb Positions a. Ich sah den Mann I saw the man b. Den Mann sah ich the man saw I c. Ich will [den Mann sehen] I want the man to. see[inf] d. Den Mann will ich [sehen] the man want I to. see[inf]

Two Verb Positions a. Ich sah den Mann I saw the man b. Den Mann sah ich the man saw I agreeing verbs (i. e. finite verbs) appear in second position c. Ich will [den Mann sehen] I want the man to. see[inf] d. Den Mann will ich [sehen] the man want I to. see[inf] non-agreeing verbs (i. e. infinitive verbs) appear in final position

Two Verb Positions a. Ich sah den Mann I saw the man b. Den Mann sah ich the man saw I agreeing verbs (i. e. finite verbs) appear in second position c. Ich will [den Mann sehen] I want the man to. see[inf] d. Den Mann will ich [sehen] the man want I to. see[inf] non-agreeing verbs (i. e. infinitive verbs) appear in final position

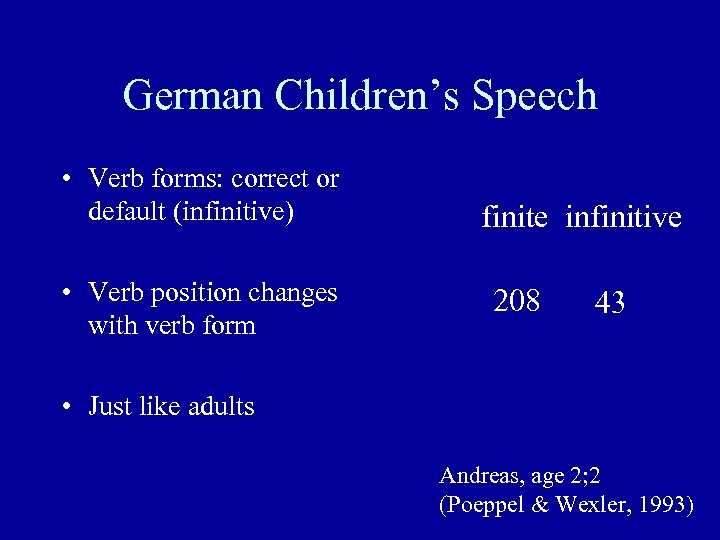

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive 208 43 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive 208 43 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

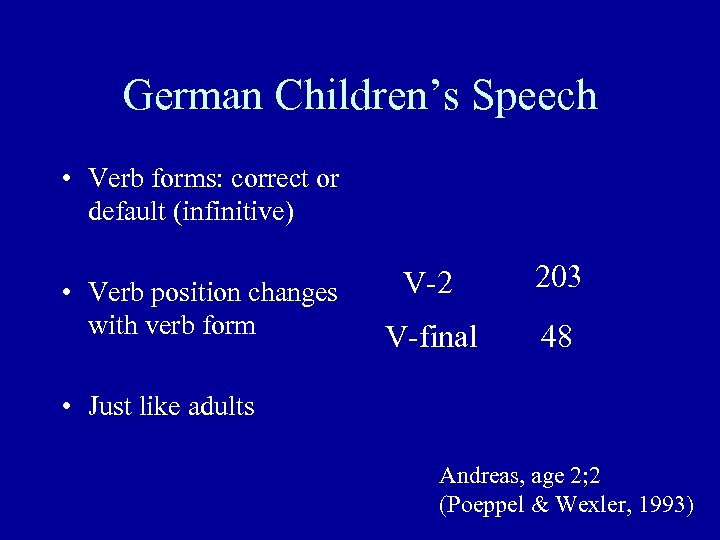

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form V-2 203 V-final 48 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form V-2 203 V-final 48 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

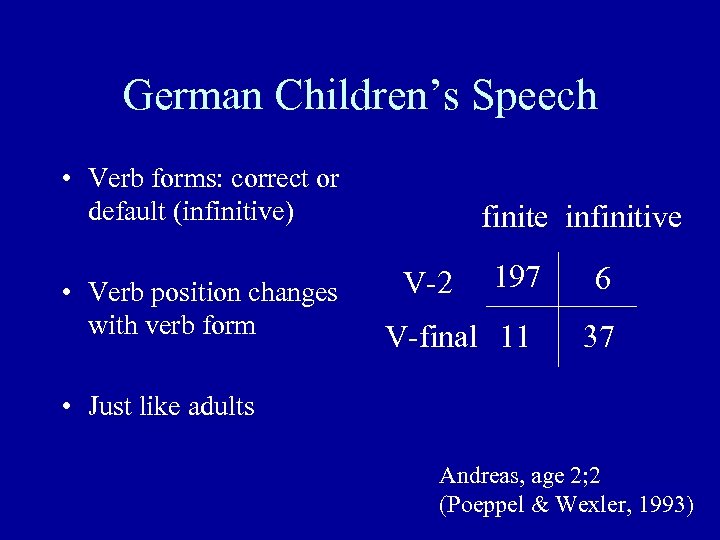

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive V-2 197 V-final 11 6 37 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

German Children’s Speech • Verb forms: correct or default (infinitive) • Verb position changes with verb form finite infinitive V-2 197 V-final 11 6 37 • Just like adults Andreas, age 2; 2 (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993)

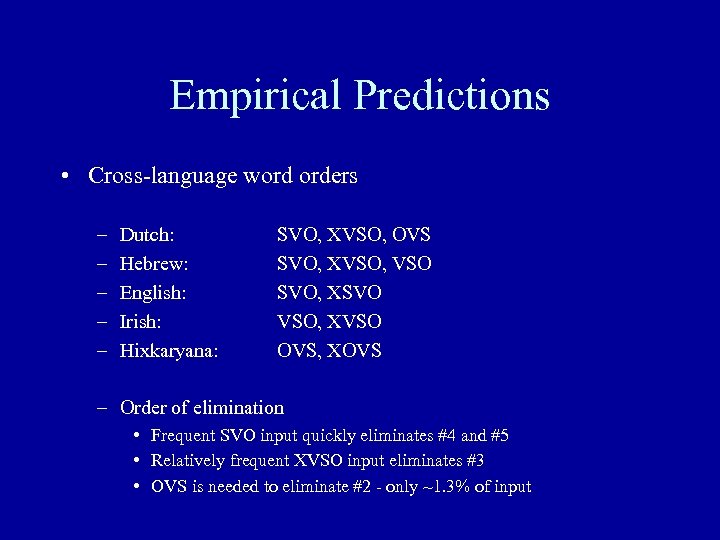

Empirical Predictions • Cross-language word orders – – – Dutch: Hebrew: English: Irish: Hixkaryana: SVO, XVSO, OVS SVO, XVSO, VSO SVO, XSVO VSO, XVSO OVS, XOVS – Order of elimination • Frequent SVO input quickly eliminates #4 and #5 • Relatively frequent XVSO input eliminates #3 • OVS is needed to eliminate #2 - only ~1. 3% of input

Empirical Predictions • Cross-language word orders – – – Dutch: Hebrew: English: Irish: Hixkaryana: SVO, XVSO, OVS SVO, XVSO, VSO SVO, XSVO VSO, XVSO OVS, XOVS – Order of elimination • Frequent SVO input quickly eliminates #4 and #5 • Relatively frequent XVSO input eliminates #3 • OVS is needed to eliminate #2 - only ~1. 3% of input

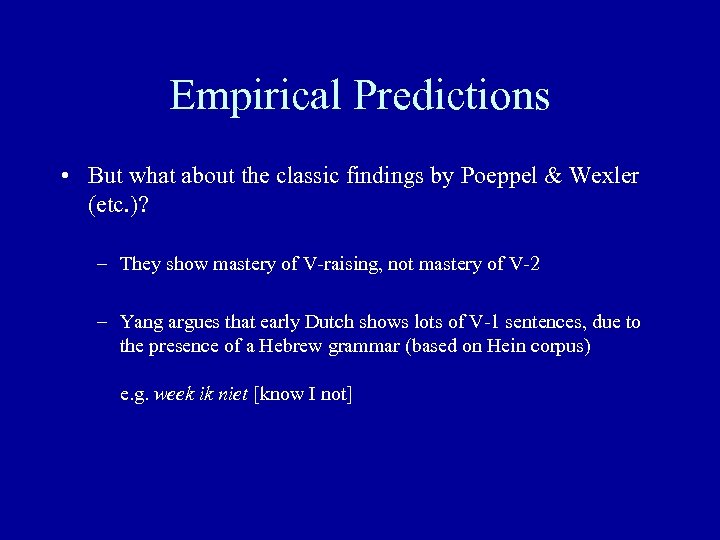

Empirical Predictions • But what about the classic findings by Poeppel & Wexler (etc. )? – They show mastery of V-raising, not mastery of V-2 – Yang argues that early Dutch shows lots of V-1 sentences, due to the presence of a Hebrew grammar (based on Hein corpus) e. g. week ik niet [know I not]

Empirical Predictions • But what about the classic findings by Poeppel & Wexler (etc. )? – They show mastery of V-raising, not mastery of V-2 – Yang argues that early Dutch shows lots of V-1 sentences, due to the presence of a Hebrew grammar (based on Hein corpus) e. g. week ik niet [know I not]

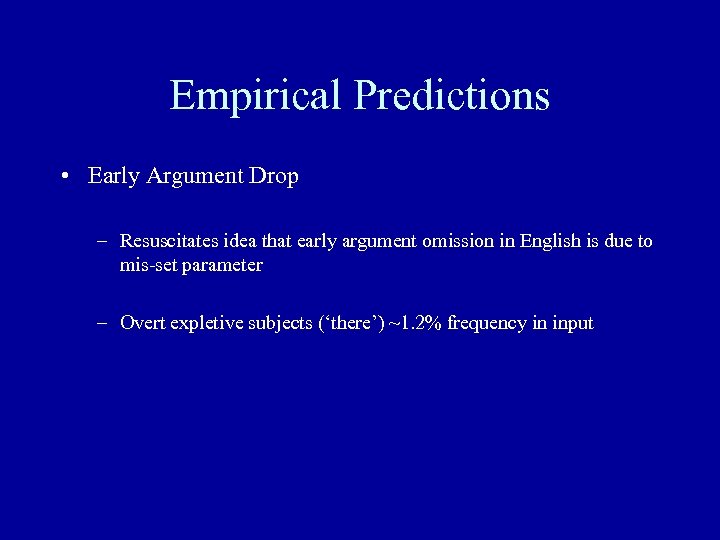

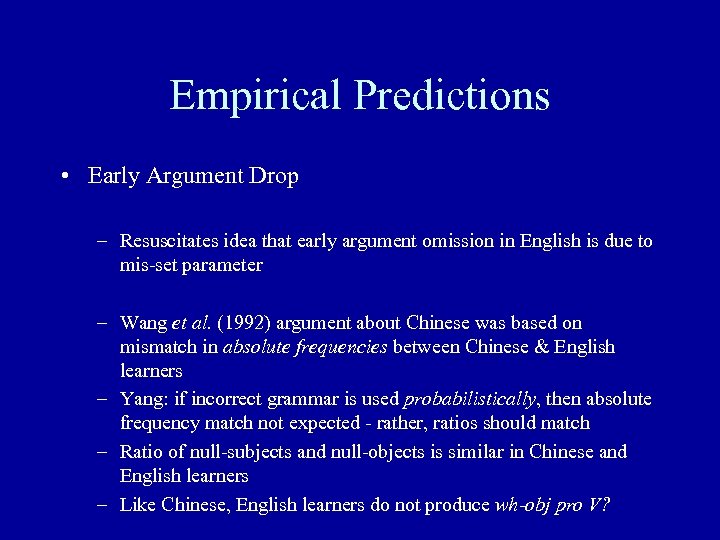

Empirical Predictions • Early Argument Drop – Resuscitates idea that early argument omission in English is due to mis-set parameter – Overt expletive subjects (‘there’) ~1. 2% frequency in input

Empirical Predictions • Early Argument Drop – Resuscitates idea that early argument omission in English is due to mis-set parameter – Overt expletive subjects (‘there’) ~1. 2% frequency in input

Null Subjects • Child English – Eat cookie. • Hyams (1986) – English children have an Italian setting of null-subject parameter – Trigger for change: expletive subjects • Valian (1991) – Usage of English children is different from Italian children (proportion) • Wang (1992) – Usage of English children is different from Chinese children (null objects)

Null Subjects • Child English – Eat cookie. • Hyams (1986) – English children have an Italian setting of null-subject parameter – Trigger for change: expletive subjects • Valian (1991) – Usage of English children is different from Italian children (proportion) • Wang (1992) – Usage of English children is different from Chinese children (null objects)

Empirical Predictions • Early Argument Drop – Resuscitates idea that early argument omission in English is due to mis-set parameter – Wang et al. (1992) argument about Chinese was based on mismatch in absolute frequencies between Chinese & English learners – Yang: if incorrect grammar is used probabilistically, then absolute frequency match not expected - rather, ratios should match – Ratio of null-subjects and null-objects is similar in Chinese and English learners – Like Chinese, English learners do not produce wh-obj pro V?

Empirical Predictions • Early Argument Drop – Resuscitates idea that early argument omission in English is due to mis-set parameter – Wang et al. (1992) argument about Chinese was based on mismatch in absolute frequencies between Chinese & English learners – Yang: if incorrect grammar is used probabilistically, then absolute frequency match not expected - rather, ratios should match – Ratio of null-subjects and null-objects is similar in Chinese and English learners – Like Chinese, English learners do not produce wh-obj pro V?

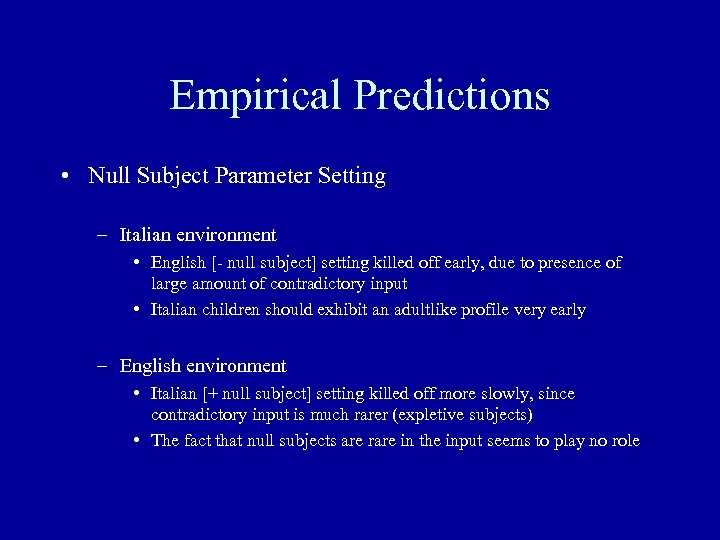

Empirical Predictions • Null Subject Parameter Setting – Italian environment • English [- null subject] setting killed off early, due to presence of large amount of contradictory input • Italian children should exhibit an adultlike profile very early – English environment • Italian [+ null subject] setting killed off more slowly, since contradictory input is much rarer (expletive subjects) • The fact that null subjects are rare in the input seems to play no role

Empirical Predictions • Null Subject Parameter Setting – Italian environment • English [- null subject] setting killed off early, due to presence of large amount of contradictory input • Italian children should exhibit an adultlike profile very early – English environment • Italian [+ null subject] setting killed off more slowly, since contradictory input is much rarer (expletive subjects) • The fact that null subjects are rare in the input seems to play no role

Tuesday 12/9

Tuesday 12/9

Poverty of the Stimulus • Structure-dependent auxiliary fronting – Is [the man who is sleeping] __ going to make it to class? – *Is [the man who __ sleeping] is going to make it to class? • Pullum: relevant positive examples exist (in the Wall Street Journal) • Yang: even if they do exist, they’re not frequent enough to account for mastery by children age 3; 2 in Crain & Nakayama’s experiments (1987)

Poverty of the Stimulus • Structure-dependent auxiliary fronting – Is [the man who is sleeping] __ going to make it to class? – *Is [the man who __ sleeping] is going to make it to class? • Pullum: relevant positive examples exist (in the Wall Street Journal) • Yang: even if they do exist, they’re not frequent enough to account for mastery by children age 3; 2 in Crain & Nakayama’s experiments (1987)

Other Parameters • Noun compounding/complex predicates – English • Novel N-N compounds punish Romance-style grammars • Simple data can lead to elimination of competitors – Spanish • Lack of productive N-N compounds is irrelevant • Lack of complex predicate constructions is irrelevant • How can the English (superset) grammar be excluded? • Subset problem

Other Parameters • Noun compounding/complex predicates – English • Novel N-N compounds punish Romance-style grammars • Simple data can lead to elimination of competitors – Spanish • Lack of productive N-N compounds is irrelevant • Lack of complex predicate constructions is irrelevant • How can the English (superset) grammar be excluded? • Subset problem

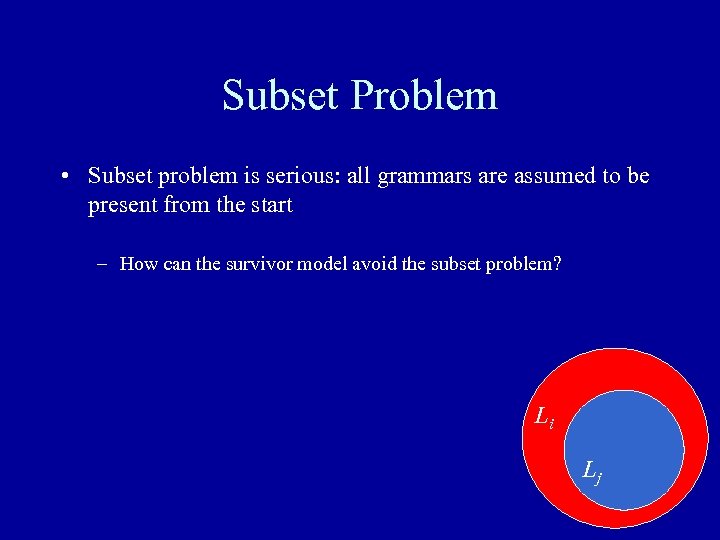

Subset Problem • Subset problem is serious: all grammars are assumed to be present from the start – How can the survivor model avoid the subset problem? Li Lj

Subset Problem • Subset problem is serious: all grammars are assumed to be present from the start – How can the survivor model avoid the subset problem? Li Lj

Other Parameters • P-stranding Parameter – English • Who are you talking with? • Positive examples of P-stranding punish non P-stranding grammars – Spanish • ***Quien hablas con? • Non-occurrence of P-stranding does not punish P-stranding grammars • Could anything be learned from the consistent use of piedpiping, or from the absence of P-stranding?

Other Parameters • P-stranding Parameter – English • Who are you talking with? • Positive examples of P-stranding punish non P-stranding grammars – Spanish • ***Quien hablas con? • Non-occurrence of P-stranding does not punish P-stranding grammars • Could anything be learned from the consistent use of piedpiping, or from the absence of P-stranding?

Other Parameters • Locative verbs & Verb compounding – John poured the water into the glass. *John poured the glass with water. – (*)John filled the water into the glass. <-- ok if [+V compounding] John filled the glass with water. – English • Absence of V-compounding is irrelevant • Simple examples above do not punish Korean grammar (superset) • Korean grammar may be punished by more liberal properties elsewhere, e. g. pile the table with books. – Korean • Occurrence of ground verbs in figure frame punishes English grammar • Occurrence of V-compounds punishes English grammar

Other Parameters • Locative verbs & Verb compounding – John poured the water into the glass. *John poured the glass with water. – (*)John filled the water into the glass. <-- ok if [+V compounding] John filled the glass with water. – English • Absence of V-compounding is irrelevant • Simple examples above do not punish Korean grammar (superset) • Korean grammar may be punished by more liberal properties elsewhere, e. g. pile the table with books. – Korean • Occurrence of ground verbs in figure frame punishes English grammar • Occurrence of V-compounds punishes English grammar

Other Parameters • “Or as PPI” Parameter – John didn’t eat apples or oranges – English • Neither…nor reading punishes Japanese grammar – Japanese • Examples of Japanese reading punish English? ? ?

Other Parameters • “Or as PPI” Parameter – John didn’t eat apples or oranges – English • Neither…nor reading punishes Japanese grammar – Japanese • Examples of Japanese reading punish English? ? ?

Other Parameters • Classic Subjacency Parameter (Rizzi, 1982) – English: *What do you know whether John likes ___? Italian: ok Analysis: Bounding nodes are (i) NP, (ii) CP (It. )/IP (Eng. ) – English • Input regarding subjacency is consistent with Italian grammar – Italian • If wh-island violations occur, this punishes English grammar • Worry: production processes in English give rise to non-trivial numbers of wh-island violations.

Other Parameters • Classic Subjacency Parameter (Rizzi, 1982) – English: *What do you know whether John likes ___? Italian: ok Analysis: Bounding nodes are (i) NP, (ii) CP (It. )/IP (Eng. ) – English • Input regarding subjacency is consistent with Italian grammar – Italian • If wh-island violations occur, this punishes English grammar • Worry: production processes in English give rise to non-trivial numbers of wh-island violations.

Triggers • Triggers – Unambiguous triggers - if they exist - do not have the role of identifying the winner as much as punishing the losers – Distributed triggers - target grammar is identified by conjunction of two different properties, neither of which is sufficient on its own • Difficult for Fodor and for Gibson/Wexler - no memory • Survivor model: also no memory, but distributed trigger works by never punishing the winner, but separately punishing the losers

Triggers • Triggers – Unambiguous triggers - if they exist - do not have the role of identifying the winner as much as punishing the losers – Distributed triggers - target grammar is identified by conjunction of two different properties, neither of which is sufficient on its own • Difficult for Fodor and for Gibson/Wexler - no memory • Survivor model: also no memory, but distributed trigger works by never punishing the winner, but separately punishing the losers

Questions about Survivor Model • How to address the Subset Problem • Better empirical evidence for multiple grammars

Questions about Survivor Model • How to address the Subset Problem • Better empirical evidence for multiple grammars

Role of Probabilistic Information • Probabilistic information has limited role – It is used to predict the time-course of hypothesis evaluation – It contributes to the ultimate likelihood of success in only a very limited sense – It does not contribute to the generation of hypotheses - these are provided by a pre-given parameter space – By gradually accumulating evidence for or against hypotheses, the model becomes somewhat robust to noise • One-grammar-at-a-time models – Negative evidence (i. e. parse failure) has drastic effect – Hard to track degree of confidence in a given hypothesis – Therefore hard to protect against fragility

Role of Probabilistic Information • Probabilistic information has limited role – It is used to predict the time-course of hypothesis evaluation – It contributes to the ultimate likelihood of success in only a very limited sense – It does not contribute to the generation of hypotheses - these are provided by a pre-given parameter space – By gradually accumulating evidence for or against hypotheses, the model becomes somewhat robust to noise • One-grammar-at-a-time models – Negative evidence (i. e. parse failure) has drastic effect – Hard to track degree of confidence in a given hypothesis – Therefore hard to protect against fragility

Statistics as Evidence or as Hypothesis • Phonological learning – Age 0 -1: developmental change reflects tracking of surface distribution of sounds? – Age 1 -2: [current frontier] developmental change involves abstraction over a growing lexicon, leading to more efficient representations • Neural Networks etc. – Statistical generalizations are the hypotheses • Lexical Access – Context guides selection among multiple lexical candidates • Syntactic Learning – Survivor model: statistics tracks accumuulation of evidence for pre -given hypotheses

Statistics as Evidence or as Hypothesis • Phonological learning – Age 0 -1: developmental change reflects tracking of surface distribution of sounds? – Age 1 -2: [current frontier] developmental change involves abstraction over a growing lexicon, leading to more efficient representations • Neural Networks etc. – Statistical generalizations are the hypotheses • Lexical Access – Context guides selection among multiple lexical candidates • Syntactic Learning – Survivor model: statistics tracks accumuulation of evidence for pre -given hypotheses

Three Benchmarks • Complexity • Consistency • Causality

Three Benchmarks • Complexity • Consistency • Causality

Complexity • Most statistical models have little to say about the kinds of complex linguistic phenomena that linguists spend their time worrying about [Models that focus on percentage success in parsing naturally occurring corpora often don’t even evaluate success on specific constructions]

Complexity • Most statistical models have little to say about the kinds of complex linguistic phenomena that linguists spend their time worrying about [Models that focus on percentage success in parsing naturally occurring corpora often don’t even evaluate success on specific constructions]

Consistency 1: Condition C • Condition C selectively excludes cases of backwards anaphora – Ok – * While he was reading the book, Pooh ate an apple. He ate an apple while Pooh was reading the book. • Evidence for the constraint is probably obscure in the input data, but it’s quite robust in adult speakers

Consistency 1: Condition C • Condition C selectively excludes cases of backwards anaphora – Ok – * While he was reading the book, Pooh ate an apple. He ate an apple while Pooh was reading the book. • Evidence for the constraint is probably obscure in the input data, but it’s quite robust in adult speakers

while Jessica Russell GME at the 2 nd NP in non-Pr. C pair

while Jessica Russell GME at the 2 nd NP in non-Pr. C pair

while Jessica Russell GME at the 2 nd NP in non-Pr. C pair NO GME at the 2 nd NP in Pr. C Principle C – EARLY filter

while Jessica Russell GME at the 2 nd NP in non-Pr. C pair NO GME at the 2 nd NP in Pr. C Principle C – EARLY filter

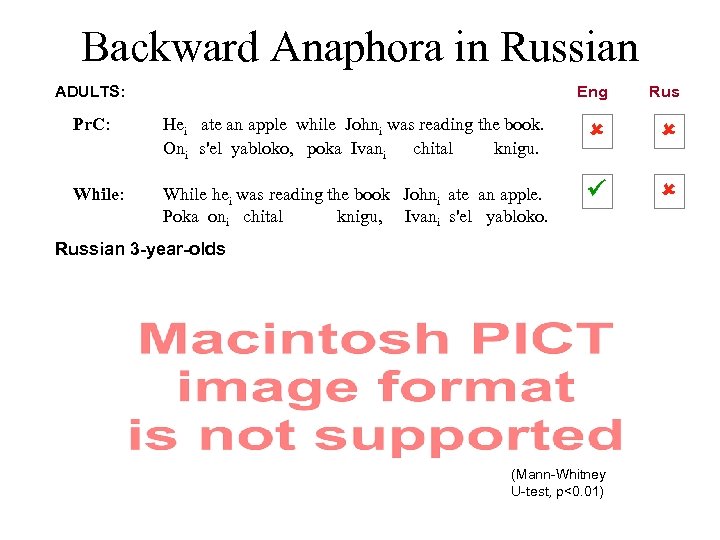

Backward Anaphora in Russian ADULTS: Eng Rus Pr. C: Hei ate an apple while Johni was reading the book. Oni s'el yabloko, poka Ivani chital knigu. While: While hei was reading the book Johni ate an apple. Poka oni chital knigu, Ivani s'el yabloko. Russian 3 -year-olds (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0. 01)

Backward Anaphora in Russian ADULTS: Eng Rus Pr. C: Hei ate an apple while Johni was reading the book. Oni s'el yabloko, poka Ivani chital knigu. While: While hei was reading the book Johni ate an apple. Poka oni chital knigu, Ivani s'el yabloko. Russian 3 -year-olds (Mann-Whitney U-test, p<0. 01)

Consistency 2: Argument Structure • Example from cross-language variation in argument structure of locative verbs • Despite variation across-languages in simple VP structures, cross-language uniformity emerges in rarer constructions – Adjectival passives – Korean serialization – Etc.

Consistency 2: Argument Structure • Example from cross-language variation in argument structure of locative verbs • Despite variation across-languages in simple VP structures, cross-language uniformity emerges in rarer constructions – Adjectival passives – Korean serialization – Etc.

Causality 1: Japanese

Causality 1: Japanese

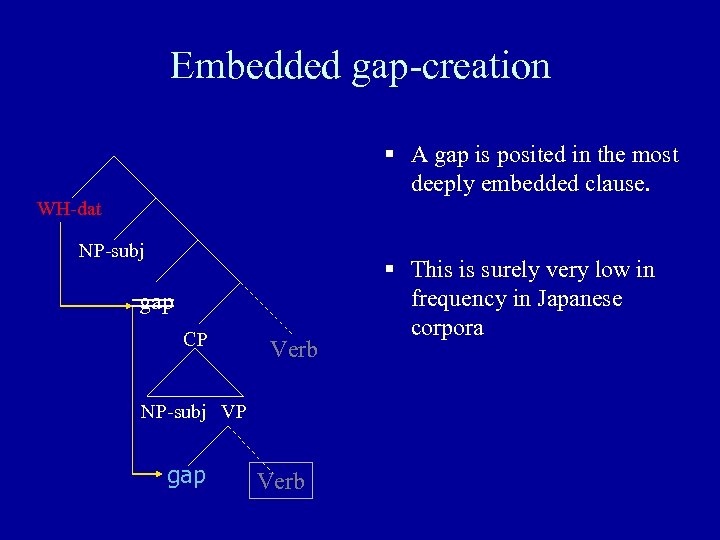

Embedded gap-creation § A gap is posited in the most deeply embedded clause. WH-dat NP-subj gap CP Verb NP-subj VP gap Verb § This is surely very low in frequency in Japanese corpora

Embedded gap-creation § A gap is posited in the most deeply embedded clause. WH-dat NP-subj gap CP Verb NP-subj VP gap Verb § This is surely very low in frequency in Japanese corpora

Causality 2: Hindi

Causality 2: Hindi

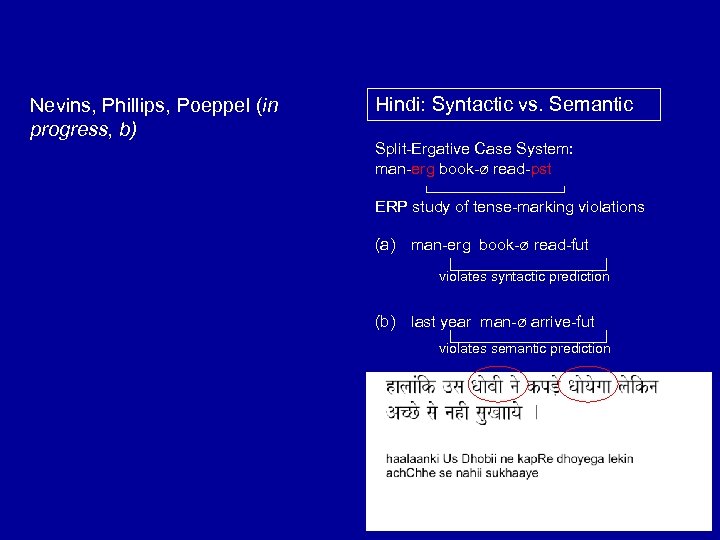

Nevins, Phillips, Poeppel (in progress, b) Hindi: Syntactic vs. Semantic Split-Ergative Case System: man-erg book-ø read-pst ERP study of tense-marking violations (a) man-erg book-ø read-fut violates syntactic prediction (b) last year man-ø arrive-fut violates semantic prediction

Nevins, Phillips, Poeppel (in progress, b) Hindi: Syntactic vs. Semantic Split-Ergative Case System: man-erg book-ø read-pst ERP study of tense-marking violations (a) man-erg book-ø read-fut violates syntactic prediction (b) last year man-ø arrive-fut violates semantic prediction

To be continued…

To be continued…