1a51e256b469031e5e81e53dea281cd1.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 56

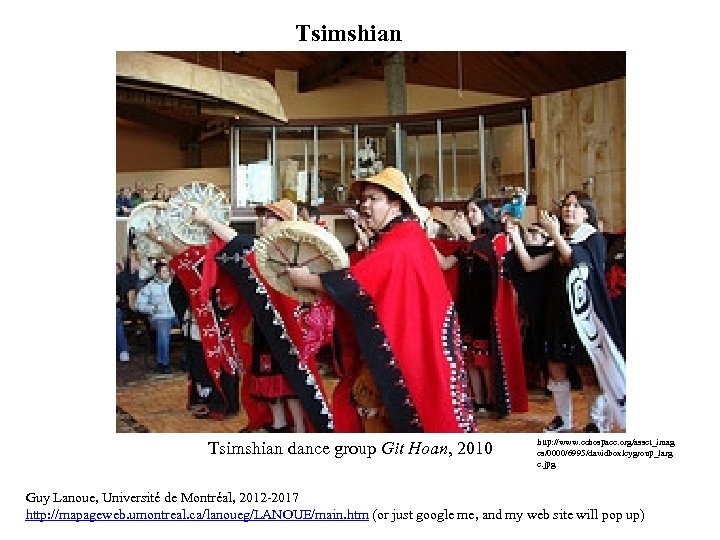

Tsimshian dance group Git Hoan, 2010 http: //www. echospace. org/asset_imag es/0000/6995/davidboxleygroup_larg e. jpg Guy Lanoue, Université de Montréal, 2012 -2017 http: //mapageweb. umontreal. ca/lanoueg/LANOUE/main. htm (or just google me, and my web site will pop up)

Tsimshian dance group Git Hoan, 2010 http: //www. echospace. org/asset_imag es/0000/6995/davidboxleygroup_larg e. jpg Guy Lanoue, Université de Montréal, 2012 -2017 http: //mapageweb. umontreal. ca/lanoueg/LANOUE/main. htm (or just google me, and my web site will pop up)

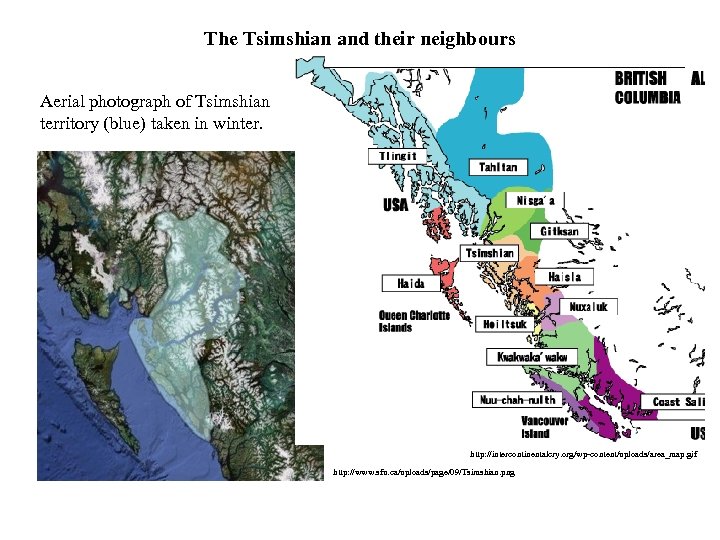

The Tsimshian and their neighbours Aerial photograph of Tsimshian territory (blue) taken in winter. http: //intercontinentalcry. org/wp-content/uploads/area_map. gif http: //www. sfu. ca/uploads/page/09/Tsimshian. png

The Tsimshian and their neighbours Aerial photograph of Tsimshian territory (blue) taken in winter. http: //intercontinentalcry. org/wp-content/uploads/area_map. gif http: //www. sfu. ca/uploads/page/09/Tsimshian. png

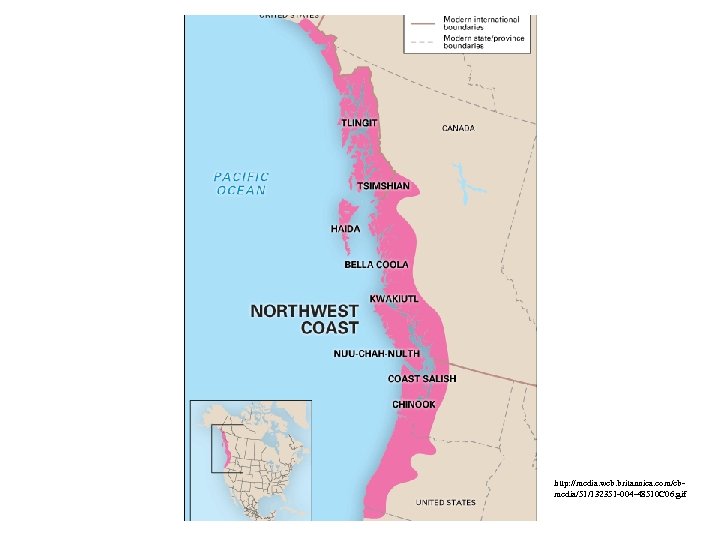

http: //media. web. britannica. com/ebmedia/51/132351 -004 -48510 C 06. gif

http: //media. web. britannica. com/ebmedia/51/132351 -004 -48510 C 06. gif

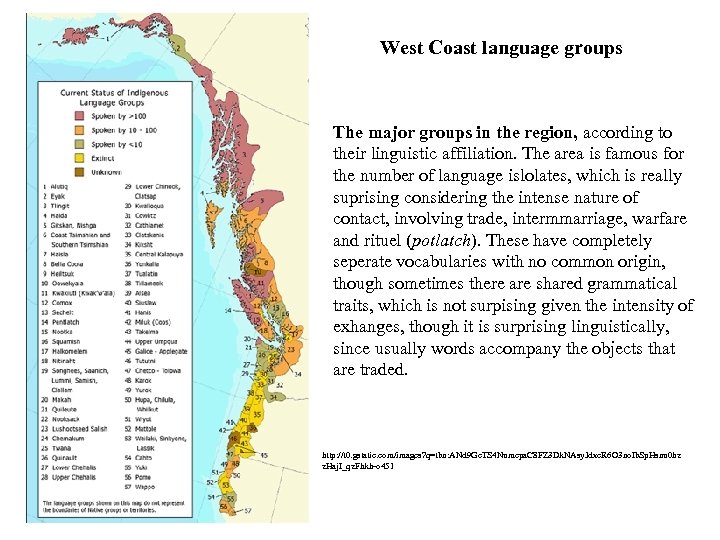

West Coast language groups The major groups in the region, according to their linguistic affiliation. The area is famous for the number of language islolates, which is really suprising considering the intense nature of contact, involving trade, intermmarriage, warfare and rituel (potlatch). These have completely seperate vocabularies with no common origin, though sometimes there are shared grammatical traits, which is not surpising given the intensity of exhanges, though it is surprising linguistically, since usually words accompany the objects that are traded. http: //t 0. gstatic. com/images? q=tbn: ANd 9 Gc. TS 4 Numepa. C 8 FZ 3 Dk. NAsy. Jdxe. R 6 O 3 no. Ib. Sp. Hsnu 0 hz z. Haj. I_qz. Fhkh-o 451

West Coast language groups The major groups in the region, according to their linguistic affiliation. The area is famous for the number of language islolates, which is really suprising considering the intense nature of contact, involving trade, intermmarriage, warfare and rituel (potlatch). These have completely seperate vocabularies with no common origin, though sometimes there are shared grammatical traits, which is not surpising given the intensity of exhanges, though it is surprising linguistically, since usually words accompany the objects that are traded. http: //t 0. gstatic. com/images? q=tbn: ANd 9 Gc. TS 4 Numepa. C 8 FZ 3 Dk. NAsy. Jdxe. R 6 O 3 no. Ib. Sp. Hsnu 0 hz z. Haj. I_qz. Fhkh-o 451

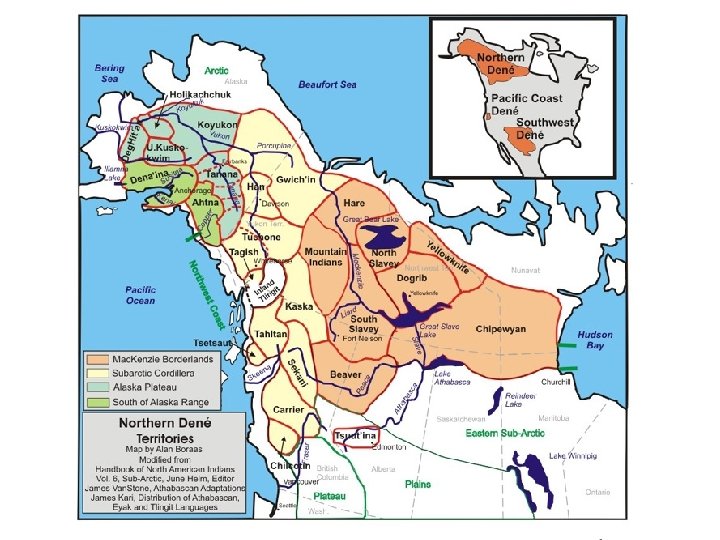

West Coast peoples are known for their woven blankets, sculptures (masks), paintings, canoes, warlike attitudes and matrilineal societies Ces couvertures étaient tissées du poil d’une espèce de chien élevé spécifiquement pour cette fin, mélangé avec du poil obtenu du chèvre de montagne. Leur fonction était de démontrer le pouvoir du groupe qui pouvait obtenir la matière première rare pour les tisser. Elles n’étaient pas utilisées pour tenir chaud les personnes, mais portées pendant les cérémonies. Au 19 e siècle, la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson a commencé à offrir ses fameuses couvertures, qui étaient convoitées par les peuples de cette région. Elles étaient des objets-clés dans le potlatch. http: //www. canadiandesignresource. ca/officialgallery/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/hudsons-bay-blanket. jpg

West Coast peoples are known for their woven blankets, sculptures (masks), paintings, canoes, warlike attitudes and matrilineal societies Ces couvertures étaient tissées du poil d’une espèce de chien élevé spécifiquement pour cette fin, mélangé avec du poil obtenu du chèvre de montagne. Leur fonction était de démontrer le pouvoir du groupe qui pouvait obtenir la matière première rare pour les tisser. Elles n’étaient pas utilisées pour tenir chaud les personnes, mais portées pendant les cérémonies. Au 19 e siècle, la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson a commencé à offrir ses fameuses couvertures, qui étaient convoitées par les peuples de cette région. Elles étaient des objets-clés dans le potlatch. http: //www. canadiandesignresource. ca/officialgallery/wp-content/uploads/2008/07/hudsons-bay-blanket. jpg

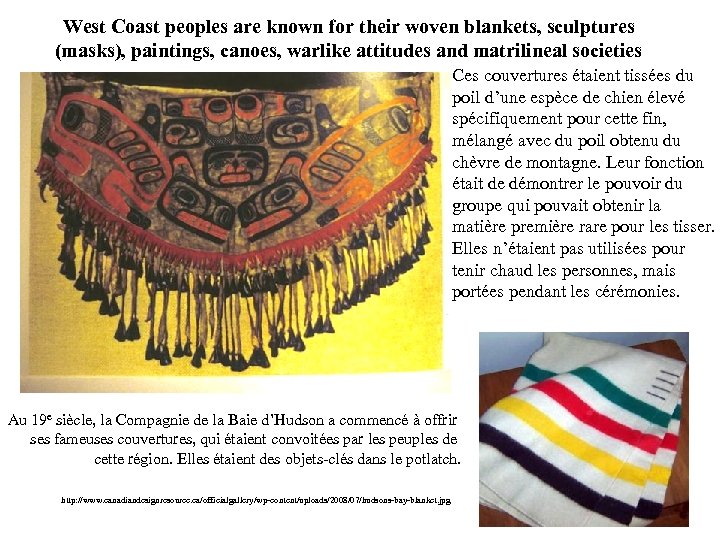

Canoes were used in warfare and carved from a single cedar tree trunk http: //www. ecologyandsociety. org/vol 14/iss 2/art 43/figure 2. jpg

Canoes were used in warfare and carved from a single cedar tree trunk http: //www. ecologyandsociety. org/vol 14/iss 2/art 43/figure 2. jpg

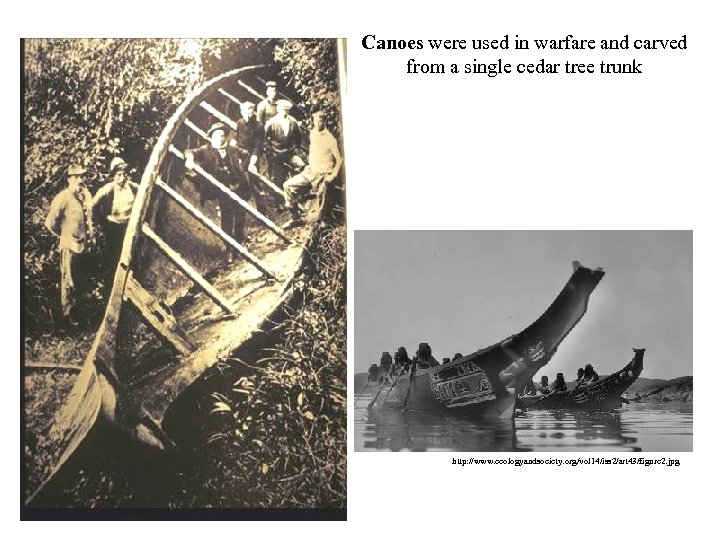

House facade, Kwakiutl The open mouth is in fact the door

House facade, Kwakiutl The open mouth is in fact the door

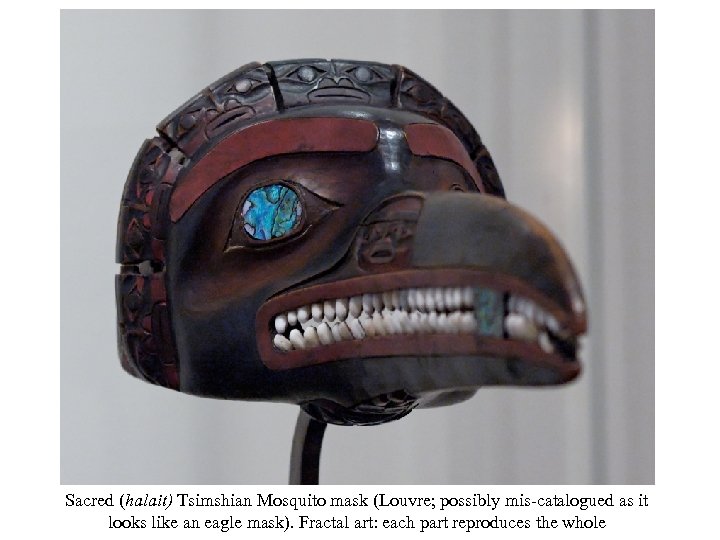

Sacred (halait) Tsimshian Mosquito mask (Louvre; possibly mis-catalogued as it looks like an eagle mask). Fractal art: each part reproduces the whole

Sacred (halait) Tsimshian Mosquito mask (Louvre; possibly mis-catalogued as it looks like an eagle mask). Fractal art: each part reproduces the whole

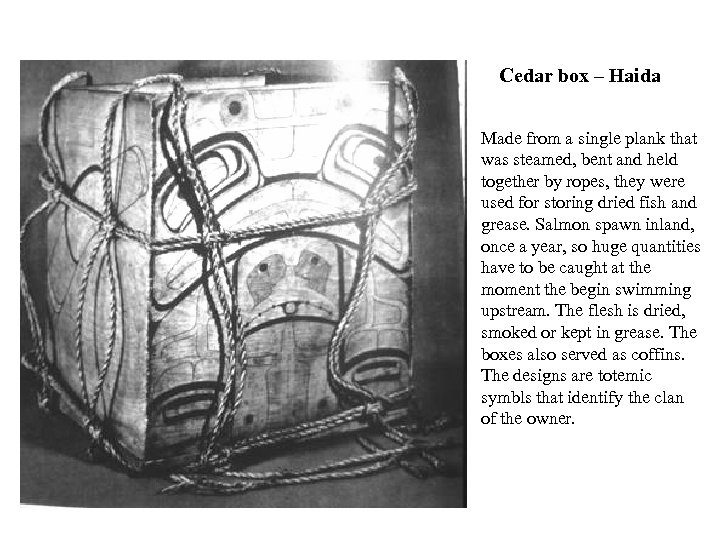

Cedar box – Haida Made from a single plank that was steamed, bent and held together by ropes, they were used for storing dried fish and grease. Salmon spawn inland, once a year, so huge quantities have to be caught at the moment the begin swimming upstream. The flesh is dried, smoked or kept in grease. The boxes also served as coffins. The designs are totemic symbls that identify the clan of the owner.

Cedar box – Haida Made from a single plank that was steamed, bent and held together by ropes, they were used for storing dried fish and grease. Salmon spawn inland, once a year, so huge quantities have to be caught at the moment the begin swimming upstream. The flesh is dried, smoked or kept in grease. The boxes also served as coffins. The designs are totemic symbls that identify the clan of the owner.

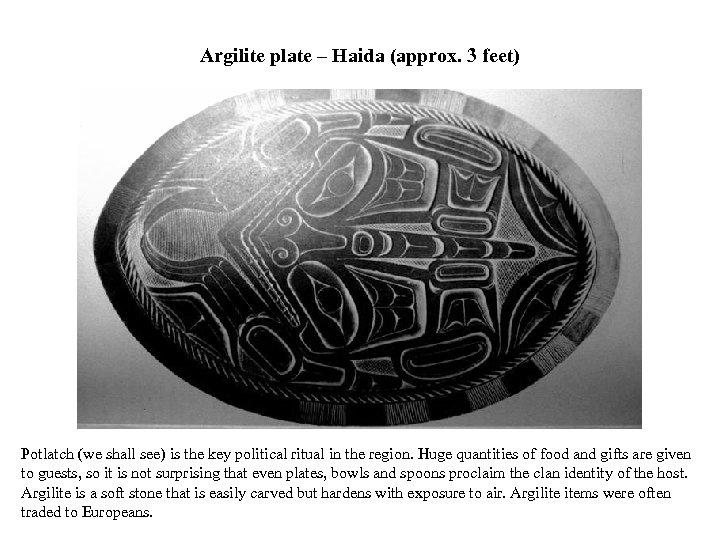

Argilite plate – Haida (approx. 3 feet) Potlatch (we shall see) is the key political ritual in the region. Huge quantities of food and gifts are given to guests, so it is not surprising that even plates, bowls and spoons proclaim the clan identity of the host. Argilite is a soft stone that is easily carved but hardens with exposure to air. Argilite items were often traded to Europeans.

Argilite plate – Haida (approx. 3 feet) Potlatch (we shall see) is the key political ritual in the region. Huge quantities of food and gifts are given to guests, so it is not surprising that even plates, bowls and spoons proclaim the clan identity of the host. Argilite is a soft stone that is easily carved but hardens with exposure to air. Argilite items were often traded to Europeans.

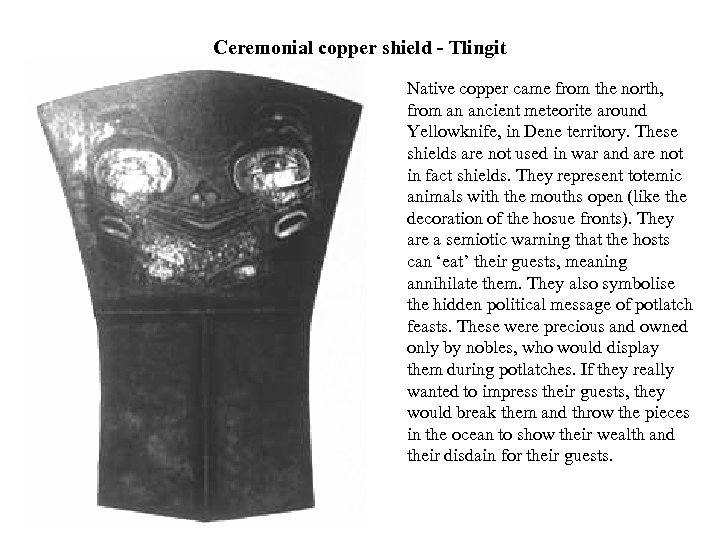

Ceremonial copper shield - Tlingit Native copper came from the north, from an ancient meteorite around Yellowknife, in Dene territory. These shields are not used in war and are not in fact shields. They represent totemic animals with the mouths open (like the decoration of the hosue fronts). They are a semiotic warning that the hosts can ‘eat’ their guests, meaning annihilate them. They also symbolise the hidden political message of potlatch feasts. These were precious and owned only by nobles, who would display them during potlatches. If they really wanted to impress their guests, they would break them and throw the pieces in the ocean to show their wealth and their disdain for their guests.

Ceremonial copper shield - Tlingit Native copper came from the north, from an ancient meteorite around Yellowknife, in Dene territory. These shields are not used in war and are not in fact shields. They represent totemic animals with the mouths open (like the decoration of the hosue fronts). They are a semiotic warning that the hosts can ‘eat’ their guests, meaning annihilate them. They also symbolise the hidden political message of potlatch feasts. These were precious and owned only by nobles, who would display them during potlatches. If they really wanted to impress their guests, they would break them and throw the pieces in the ocean to show their wealth and their disdain for their guests.

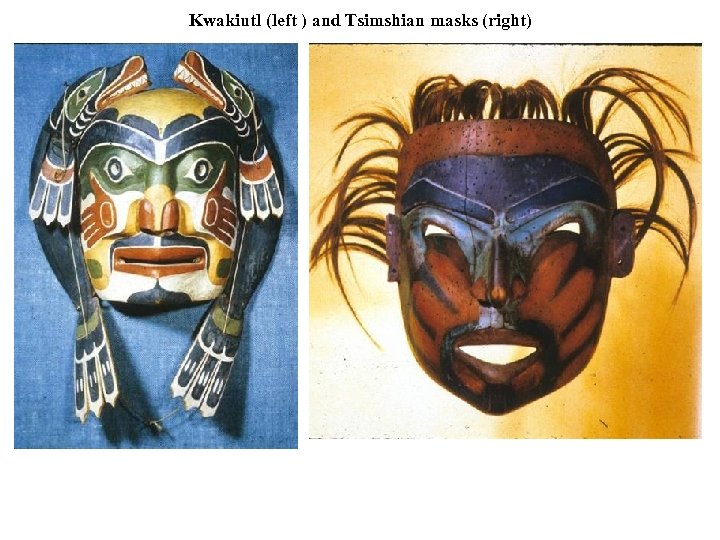

Kwakiutl (left ) and Tsimshian masks (right)

Kwakiutl (left ) and Tsimshian masks (right)

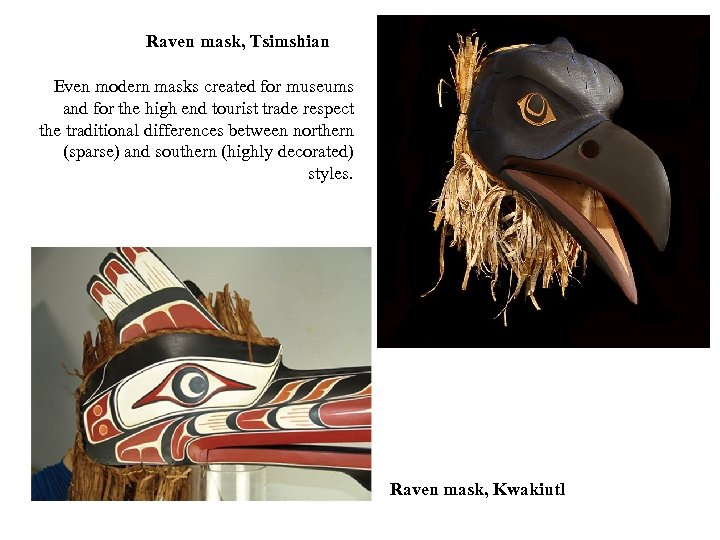

Raven mask, Tsimshian Even modern masks created for museums and for the high end tourist trade respect the traditional differences between northern (sparse) and southern (highly decorated) styles. Raven mask, Kwakiutl

Raven mask, Tsimshian Even modern masks created for museums and for the high end tourist trade respect the traditional differences between northern (sparse) and southern (highly decorated) styles. Raven mask, Kwakiutl

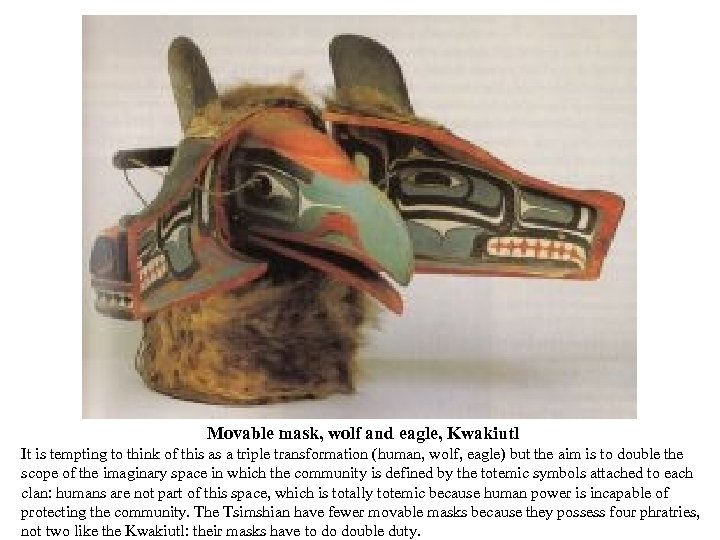

Movable mask, wolf and eagle, Kwakiutl It is tempting to think of this as a triple transformation (human, wolf, eagle) but the aim is to double the scope of the imaginary space in which the community is defined by the totemic symbols attached to each clan: humans are not part of this space, which is totally totemic because human power is incapable of protecting the community. The Tsimshian have fewer movable masks because they possess four phratries, not two like the Kwakiutl: their masks have to do double duty.

Movable mask, wolf and eagle, Kwakiutl It is tempting to think of this as a triple transformation (human, wolf, eagle) but the aim is to double the scope of the imaginary space in which the community is defined by the totemic symbols attached to each clan: humans are not part of this space, which is totally totemic because human power is incapable of protecting the community. The Tsimshian have fewer movable masks because they possess four phratries, not two like the Kwakiutl: their masks have to do double duty.

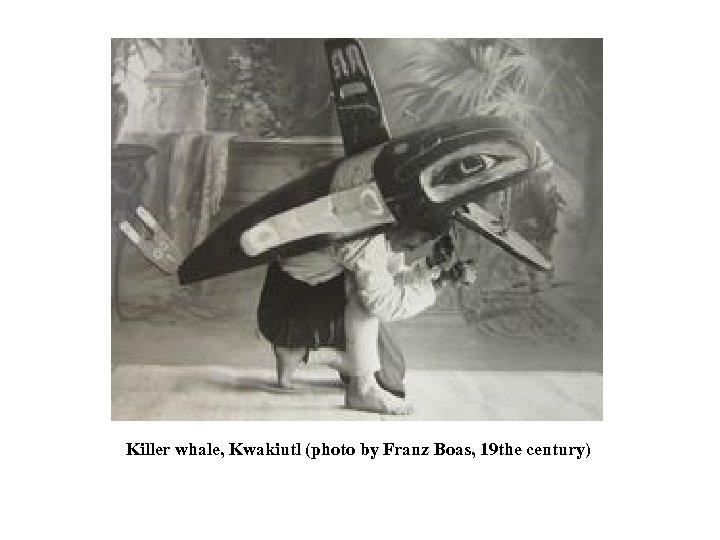

Killer whale, Kwakiutl (photo by Franz Boas, 19 the century)

Killer whale, Kwakiutl (photo by Franz Boas, 19 the century)

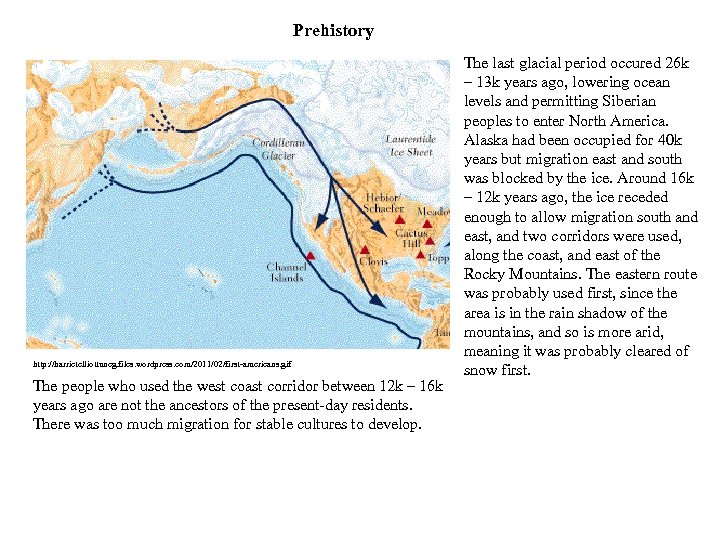

Prehistory http: //harrietelliottuncg. files. wordpress. com/2011/02/first-americans. gif The people who used the west coast corridor between 12 k – 16 k years ago are not the ancestors of the present-day residents. There was too much migration for stable cultures to develop. The last glacial period occured 26 k – 13 k years ago, lowering ocean levels and permitting Siberian peoples to enter North America. Alaska had been occupied for 40 k years but migration east and south was blocked by the ice. Around 16 k – 12 k years ago, the ice receded enough to allow migration south and east, and two corridors were used, along the coast, and east of the Rocky Mountains. The eastern route was probably used first, since the area is in the rain shadow of the mountains, and so is more arid, meaning it was probably cleared of snow first.

Prehistory http: //harrietelliottuncg. files. wordpress. com/2011/02/first-americans. gif The people who used the west coast corridor between 12 k – 16 k years ago are not the ancestors of the present-day residents. There was too much migration for stable cultures to develop. The last glacial period occured 26 k – 13 k years ago, lowering ocean levels and permitting Siberian peoples to enter North America. Alaska had been occupied for 40 k years but migration east and south was blocked by the ice. Around 16 k – 12 k years ago, the ice receded enough to allow migration south and east, and two corridors were used, along the coast, and east of the Rocky Mountains. The eastern route was probably used first, since the area is in the rain shadow of the mountains, and so is more arid, meaning it was probably cleared of snow first.

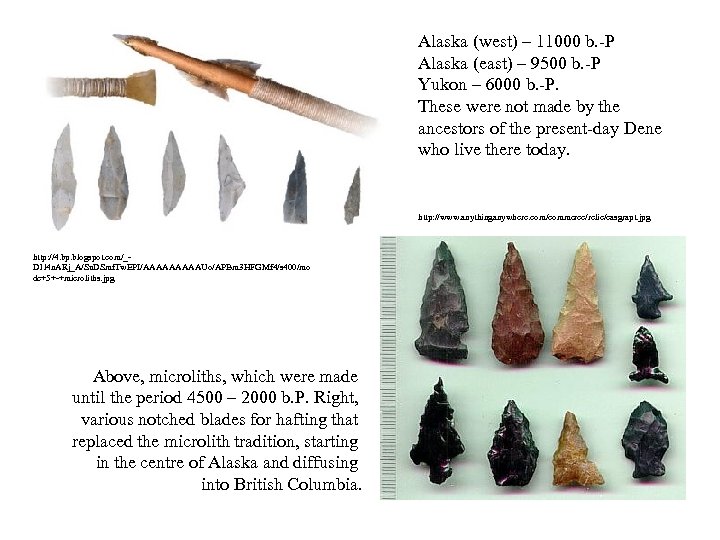

Alaska (west) – 11000 b. -P Alaska (east) – 9500 b. -P Yukon – 6000 b. -P. These were not made by the ancestors of the present-day Dene who live there today. http: //www. anythinganywhere. com/commerce/relic/casgrapt. jpg http: //4. bp. blogspot. com/_D 1 l 4 n. ARj_A/Su. DSmf. Tw. EPI/AAAAAUo/APBm 3 HFGMf 4/s 400/mo de+5+-+microliths. jpg Above, microliths, which were made until the period 4500 – 2000 b. P. Right, various notched blades for hafting that replaced the microlith tradition, starting in the centre of Alaska and diffusing into British Columbia.

Alaska (west) – 11000 b. -P Alaska (east) – 9500 b. -P Yukon – 6000 b. -P. These were not made by the ancestors of the present-day Dene who live there today. http: //www. anythinganywhere. com/commerce/relic/casgrapt. jpg http: //4. bp. blogspot. com/_D 1 l 4 n. ARj_A/Su. DSmf. Tw. EPI/AAAAAUo/APBm 3 HFGMf 4/s 400/mo de+5+-+microliths. jpg Above, microliths, which were made until the period 4500 – 2000 b. P. Right, various notched blades for hafting that replaced the microlith tradition, starting in the centre of Alaska and diffusing into British Columbia.

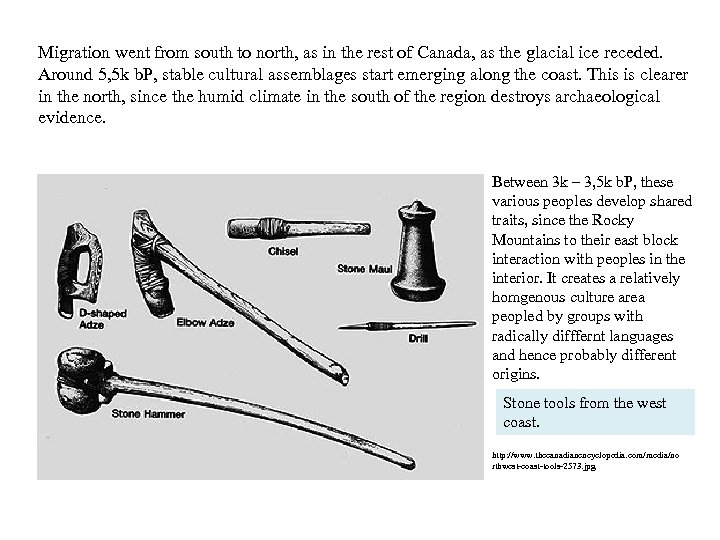

Migration went from south to north, as in the rest of Canada, as the glacial ice receded. Around 5, 5 k b. P, stable cultural assemblages start emerging along the coast. This is clearer in the north, since the humid climate in the south of the region destroys archaeological evidence. Between 3 k – 3, 5 k b. P, these various peoples develop shared traits, since the Rocky Mountains to their east block interaction with peoples in the interior. It creates a relatively homgenous culture area peopled by groups with radically difffernt languages and hence probably different origins. Stone tools from the west coast. http: //www. thecanadianencyclopedia. com/media/no rthwest-coast-tools-2573. jpg

Migration went from south to north, as in the rest of Canada, as the glacial ice receded. Around 5, 5 k b. P, stable cultural assemblages start emerging along the coast. This is clearer in the north, since the humid climate in the south of the region destroys archaeological evidence. Between 3 k – 3, 5 k b. P, these various peoples develop shared traits, since the Rocky Mountains to their east block interaction with peoples in the interior. It creates a relatively homgenous culture area peopled by groups with radically difffernt languages and hence probably different origins. Stone tools from the west coast. http: //www. thecanadianencyclopedia. com/media/no rthwest-coast-tools-2573. jpg

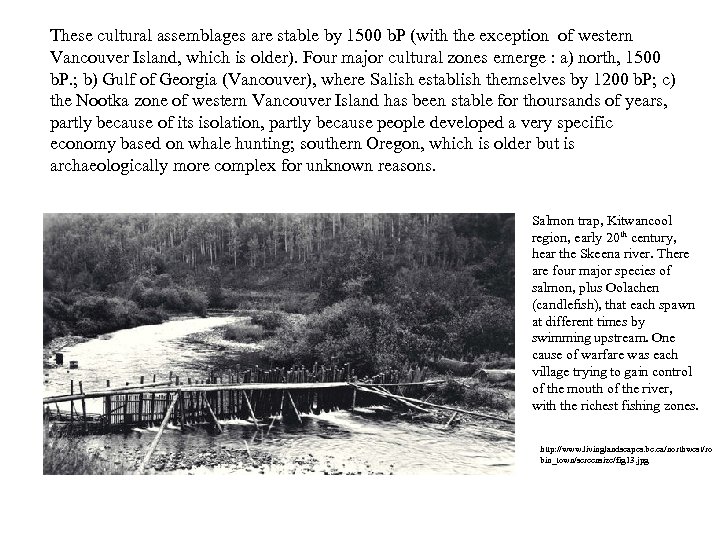

These cultural assemblages are stable by 1500 b. P (with the exception of western Vancouver Island, which is older). Four major cultural zones emerge : a) north, 1500 b. P. ; b) Gulf of Georgia (Vancouver), where Salish establish themselves by 1200 b. P; c) the Nootka zone of western Vancouver Island has been stable for thoursands of years, partly because of its isolation, partly because people developed a very specific economy based on whale hunting; southern Oregon, which is older but is archaeologically more complex for unknown reasons. Salmon trap, Kitwancool region, early 20 th century, hear the Skeena river. There are four major species of salmon, plus Oolachen (candlefish), that each spawn at different times by swimming upstream. One cause of warfare was each village trying to gain control of the mouth of the river, with the richest fishing zones. http: //www. livinglandscapes. bc. ca/northwest/ro bin_town/screensize/fig 13. jpg

These cultural assemblages are stable by 1500 b. P (with the exception of western Vancouver Island, which is older). Four major cultural zones emerge : a) north, 1500 b. P. ; b) Gulf of Georgia (Vancouver), where Salish establish themselves by 1200 b. P; c) the Nootka zone of western Vancouver Island has been stable for thoursands of years, partly because of its isolation, partly because people developed a very specific economy based on whale hunting; southern Oregon, which is older but is archaeologically more complex for unknown reasons. Salmon trap, Kitwancool region, early 20 th century, hear the Skeena river. There are four major species of salmon, plus Oolachen (candlefish), that each spawn at different times by swimming upstream. One cause of warfare was each village trying to gain control of the mouth of the river, with the richest fishing zones. http: //www. livinglandscapes. bc. ca/northwest/ro bin_town/screensize/fig 13. jpg

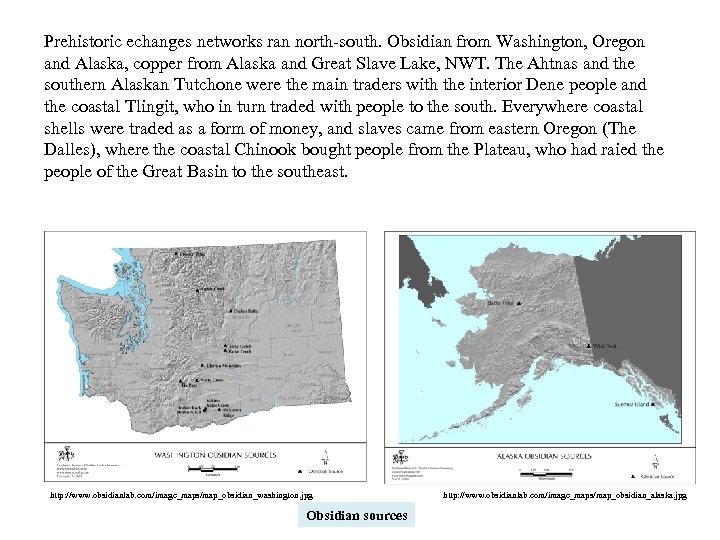

Prehistoric echanges networks ran north-south. Obsidian from Washington, Oregon and Alaska, copper from Alaska and Great Slave Lake, NWT. The Ahtnas and the southern Alaskan Tutchone were the main traders with the interior Dene people and the coastal Tlingit, who in turn traded with people to the south. Everywhere coastal shells were traded as a form of money, and slaves came from eastern Oregon (The Dalles), where the coastal Chinook bought people from the Plateau, who had raied the people of the Great Basin to the southeast. http: //www. obsidianlab. com/image_maps/map_obsidian_washington. jpg Obsidian sources http: //www. obsidianlab. com/image_maps/map_obsidian_alaska. jpg

Prehistoric echanges networks ran north-south. Obsidian from Washington, Oregon and Alaska, copper from Alaska and Great Slave Lake, NWT. The Ahtnas and the southern Alaskan Tutchone were the main traders with the interior Dene people and the coastal Tlingit, who in turn traded with people to the south. Everywhere coastal shells were traded as a form of money, and slaves came from eastern Oregon (The Dalles), where the coastal Chinook bought people from the Plateau, who had raied the people of the Great Basin to the southeast. http: //www. obsidianlab. com/image_maps/map_obsidian_washington. jpg Obsidian sources http: //www. obsidianlab. com/image_maps/map_obsidian_alaska. jpg

History of Contact 1774 – Spaniards from California visit Vancouver but do not establish a colony. 1778 – The James Cook expedition notices the abundance of high quality sea otter furs that can serve the trade in China. He notes that Indians already have iron tools, probably of Japanese origin. 1789 – Alaskan Russians move south to Kodiak Island to establish a tradiing post to prevent Americans and British traders from controlling the fur trade. . All sources mention that all Indian groups demande iron tools and modern weapons as trade items; a sign that their societies were already militarised. Competition among British, Americans, and Russians leads to inflated prices and creates favorable trade conditions for Indians. The American trade is typical: leaving Boston with iron tools, go around South America, trade iron for furs with Coastal Indians, go to Hawaii for sandalwood, then to China where they trade the sandalwood and furs for spices. The profits are so high that one three-year trip was often enough to make a trader rich for life. This meant they had no intention of returning, and wanted the best trade terms possible from the Indians, which meant they were ruthless. Unfortunately for them, Coastal Indians were used to warfare, so trade is at best hostile and at worst dangerous. Whites are often killed or cpatured, especially armourers and smiths. Indians also blame the Whites (with reason) for epidemics that break out as a result of contact. This destablises local political arrangements and leads to increased warfare on the Coast. The British and Russians have better rapport with the Indians because they are not inolved in this lucrative Chinese trade. http: //1. bp. blogspot. com/_48 GDFNNbs 3 E/S 8 a. Qsb WXb. DI/AAAAAEQ/f. TW_Wk. C 96 Mk/s 320/ A Chinese court official with an otter fur coat , earlyy 19 th century; Washington State Museum

History of Contact 1774 – Spaniards from California visit Vancouver but do not establish a colony. 1778 – The James Cook expedition notices the abundance of high quality sea otter furs that can serve the trade in China. He notes that Indians already have iron tools, probably of Japanese origin. 1789 – Alaskan Russians move south to Kodiak Island to establish a tradiing post to prevent Americans and British traders from controlling the fur trade. . All sources mention that all Indian groups demande iron tools and modern weapons as trade items; a sign that their societies were already militarised. Competition among British, Americans, and Russians leads to inflated prices and creates favorable trade conditions for Indians. The American trade is typical: leaving Boston with iron tools, go around South America, trade iron for furs with Coastal Indians, go to Hawaii for sandalwood, then to China where they trade the sandalwood and furs for spices. The profits are so high that one three-year trip was often enough to make a trader rich for life. This meant they had no intention of returning, and wanted the best trade terms possible from the Indians, which meant they were ruthless. Unfortunately for them, Coastal Indians were used to warfare, so trade is at best hostile and at worst dangerous. Whites are often killed or cpatured, especially armourers and smiths. Indians also blame the Whites (with reason) for epidemics that break out as a result of contact. This destablises local political arrangements and leads to increased warfare on the Coast. The British and Russians have better rapport with the Indians because they are not inolved in this lucrative Chinese trade. http: //1. bp. blogspot. com/_48 GDFNNbs 3 E/S 8 a. Qsb WXb. DI/AAAAAEQ/f. TW_Wk. C 96 Mk/s 320/ A Chinese court official with an otter fur coat , earlyy 19 th century; Washington State Museum

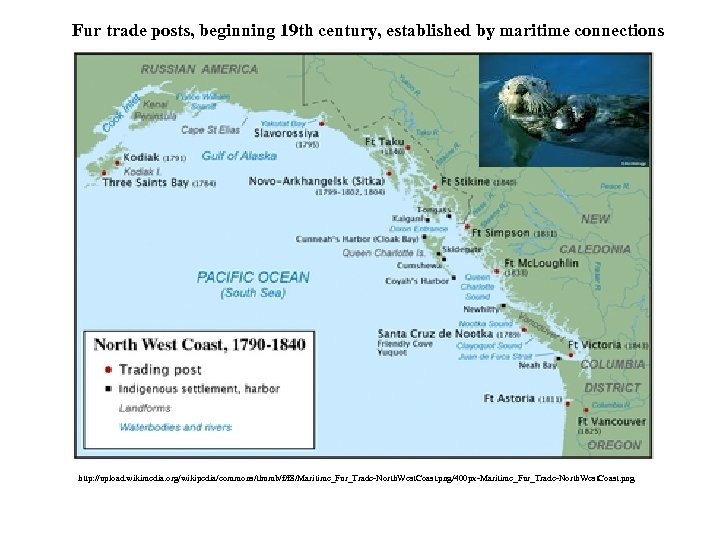

Fur trade posts, beginning 19 th century, established by maritime connections http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f 8/Maritime_Fur_Trade-North. West. Coast. png/400 px-Maritime_Fur_Trade-North. West. Coast. png

Fur trade posts, beginning 19 th century, established by maritime connections http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f 8/Maritime_Fur_Trade-North. West. Coast. png/400 px-Maritime_Fur_Trade-North. West. Coast. png

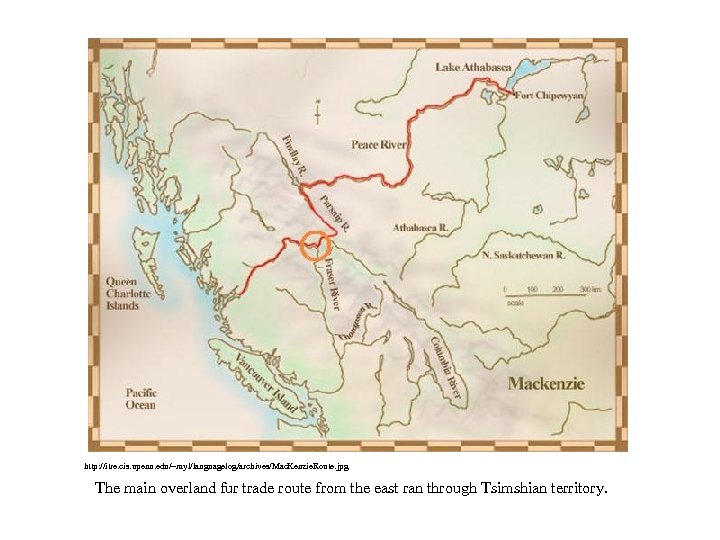

http: //itre. cis. upenn. edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/Mac. Kenzie. Route. jpg The main overland fur trade route from the east ran through Tsimshian territory.

http: //itre. cis. upenn. edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/Mac. Kenzie. Route. jpg The main overland fur trade route from the east ran through Tsimshian territory.

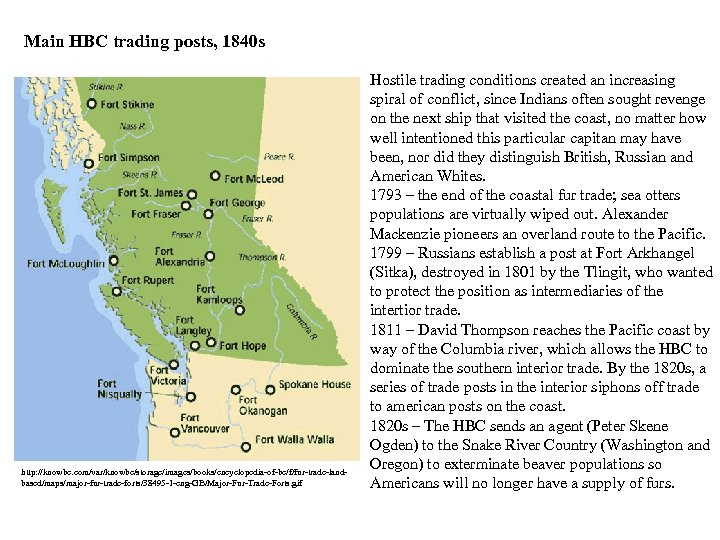

Main HBC trading posts, 1840 s http: //knowbc. com/var/knowbc/storage/images/books/encyclopedia-of-bc/f/fur-trade-landbased/maps/major-fur-trade-forts/38495 -1 -eng-GB/Major-Fur-Trade-Forts. gif Hostile trading conditions created an increasing spiral of conflict, since Indians often sought revenge on the next ship that visited the coast, no matter how well intentioned this particular capitan may have been, nor did they distinguish British, Russian and American Whites. 1793 – the end of the coastal fur trade; sea otters populations are virtually wiped out. Alexander Mackenzie pioneers an overland route to the Pacific. 1799 – Russians establish a post at Fort Arkhangel (Sitka), destroyed in 1801 by the Tlingit, who wanted to protect the position as intermediaries of the intertior trade. 1811 – David Thompson reaches the Pacific coast by way of the Columbia river, which allows the HBC to dominate the southern interior trade. By the 1820 s, a series of trade posts in the interior siphons off trade to american posts on the coast. 1820 s – The HBC sends an agent (Peter Skene Ogden) to the Snake River Country (Washington and Oregon) to exterminate beaver populations so Americans will no longer have a supply of furs.

Main HBC trading posts, 1840 s http: //knowbc. com/var/knowbc/storage/images/books/encyclopedia-of-bc/f/fur-trade-landbased/maps/major-fur-trade-forts/38495 -1 -eng-GB/Major-Fur-Trade-Forts. gif Hostile trading conditions created an increasing spiral of conflict, since Indians often sought revenge on the next ship that visited the coast, no matter how well intentioned this particular capitan may have been, nor did they distinguish British, Russian and American Whites. 1793 – the end of the coastal fur trade; sea otters populations are virtually wiped out. Alexander Mackenzie pioneers an overland route to the Pacific. 1799 – Russians establish a post at Fort Arkhangel (Sitka), destroyed in 1801 by the Tlingit, who wanted to protect the position as intermediaries of the intertior trade. 1811 – David Thompson reaches the Pacific coast by way of the Columbia river, which allows the HBC to dominate the southern interior trade. By the 1820 s, a series of trade posts in the interior siphons off trade to american posts on the coast. 1820 s – The HBC sends an agent (Peter Skene Ogden) to the Snake River Country (Washington and Oregon) to exterminate beaver populations so Americans will no longer have a supply of furs.

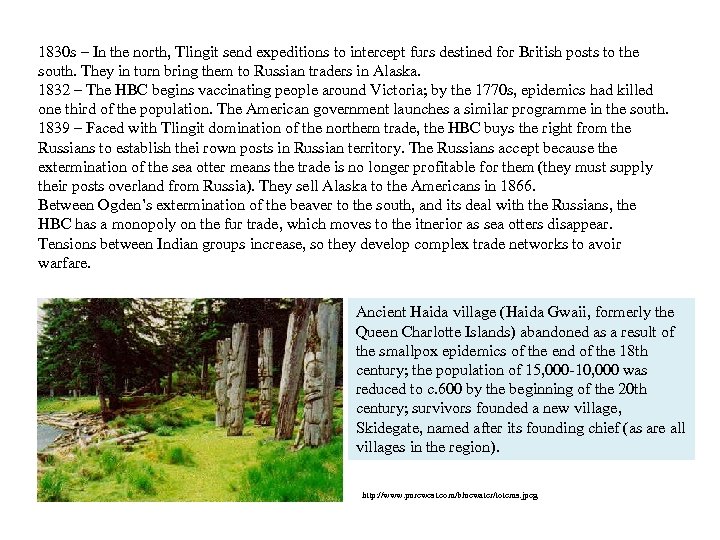

1830 s – In the north, Tlingit send expeditions to intercept furs destined for British posts to the south. They in turn bring them to Russian traders in Alaska. 1832 – The HBC begins vaccinating people around Victoria; by the 1770 s, epidemics had killed one third of the population. The American government launches a similar programme in the south. 1839 – Faced with Tlingit domination of the northern trade, the HBC buys the right from the Russians to establish thei rown posts in Russian territory. The Russians accept because the extermination of the sea otter means the trade is no longer profitable for them (they must supply their posts overland from Russia). They sell Alaska to the Americans in 1866. Between Ogden’s extermination of the beaver to the south, and its deal with the Russians, the HBC has a monopoly on the fur trade, which moves to the itnerior as sea otters disappear. Tensions between Indian groups increase, so they develop complex trade networks to avoir warfare. Ancient Haida village (Haida Gwaii, formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) abandoned as a result of the smallpox epidemics of the end of the 18 th century; the population of 15, 000 -10, 000 was reduced to c. 600 by the beginning of the 20 th century; survivors founded a new village, Skidegate, named after its founding chief (as are all villages in the region). http: //www. purewest. com/bluewater/totems. jpeg

1830 s – In the north, Tlingit send expeditions to intercept furs destined for British posts to the south. They in turn bring them to Russian traders in Alaska. 1832 – The HBC begins vaccinating people around Victoria; by the 1770 s, epidemics had killed one third of the population. The American government launches a similar programme in the south. 1839 – Faced with Tlingit domination of the northern trade, the HBC buys the right from the Russians to establish thei rown posts in Russian territory. The Russians accept because the extermination of the sea otter means the trade is no longer profitable for them (they must supply their posts overland from Russia). They sell Alaska to the Americans in 1866. Between Ogden’s extermination of the beaver to the south, and its deal with the Russians, the HBC has a monopoly on the fur trade, which moves to the itnerior as sea otters disappear. Tensions between Indian groups increase, so they develop complex trade networks to avoir warfare. Ancient Haida village (Haida Gwaii, formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) abandoned as a result of the smallpox epidemics of the end of the 18 th century; the population of 15, 000 -10, 000 was reduced to c. 600 by the beginning of the 20 th century; survivors founded a new village, Skidegate, named after its founding chief (as are all villages in the region). http: //www. purewest. com/bluewater/totems. jpeg

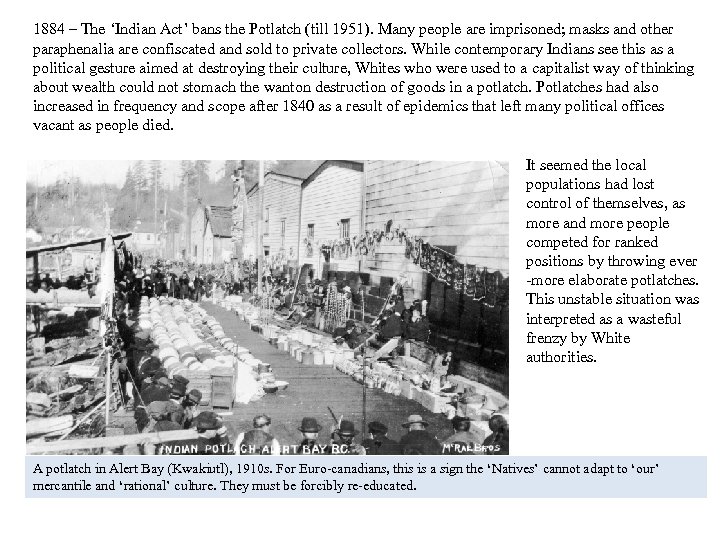

1884 – The ‘Indian Act’ bans the Potlatch (till 1951). Many people are imprisoned; masks and other paraphenalia are confiscated and sold to private collectors. While contemporary Indians see this as a political gesture aimed at destroying their culture, Whites who were used to a capitalist way of thinking about wealth could not stomach the wanton destruction of goods in a potlatch. Potlatches had also increased in frequency and scope after 1840 as a result of epidemics that left many political offices vacant as people died. It seemed the local populations had lost control of themselves, as more and more people competed for ranked positions by throwing ever -more elaborate potlatches. This unstable situation was interpreted as a wasteful frenzy by White authorities. A potlatch in Alert Bay (Kwakiutl), 1910 s. For Euro-canadians, this is a sign the ‘Natives’ cannot adapt to ‘our’ mercantile and ‘rational’ culture. They must be forcibly re-educated.

1884 – The ‘Indian Act’ bans the Potlatch (till 1951). Many people are imprisoned; masks and other paraphenalia are confiscated and sold to private collectors. While contemporary Indians see this as a political gesture aimed at destroying their culture, Whites who were used to a capitalist way of thinking about wealth could not stomach the wanton destruction of goods in a potlatch. Potlatches had also increased in frequency and scope after 1840 as a result of epidemics that left many political offices vacant as people died. It seemed the local populations had lost control of themselves, as more and more people competed for ranked positions by throwing ever -more elaborate potlatches. This unstable situation was interpreted as a wasteful frenzy by White authorities. A potlatch in Alert Bay (Kwakiutl), 1910 s. For Euro-canadians, this is a sign the ‘Natives’ cannot adapt to ‘our’ mercantile and ‘rational’ culture. They must be forcibly re-educated.

Epidemics Even the most conservative estimates put the death total from European diseases in the millions. Plagues and Peoples (William Mc. Neill, Anchor Books Doubleday, 1976) and The Burdens of Disease (J. N. Hays, Rutgers U. Press, 2009) are the most important references. Diseases overturned entire civilisations and forced massive migrations that only helded spread the diseases. Still, European colonisation could not e stopped, judging from Mexico and Peru where the shock of contact with European technology caused the collapse of Aztecs and Incas before mahor diseases could have any impact. Europeans in any one region usually came from one country and were politically united, whereas Native groups were usually divided by culture, language and economics. http: //marinebio. org/upload/_im gs/65/smallpox. gif http: //timelines. tv/sm. Pox/ more/assets/2 -5. jpg

Epidemics Even the most conservative estimates put the death total from European diseases in the millions. Plagues and Peoples (William Mc. Neill, Anchor Books Doubleday, 1976) and The Burdens of Disease (J. N. Hays, Rutgers U. Press, 2009) are the most important references. Diseases overturned entire civilisations and forced massive migrations that only helded spread the diseases. Still, European colonisation could not e stopped, judging from Mexico and Peru where the shock of contact with European technology caused the collapse of Aztecs and Incas before mahor diseases could have any impact. Europeans in any one region usually came from one country and were politically united, whereas Native groups were usually divided by culture, language and economics. http: //marinebio. org/upload/_im gs/65/smallpox. gif http: //timelines. tv/sm. Pox/ more/assets/2 -5. jpg

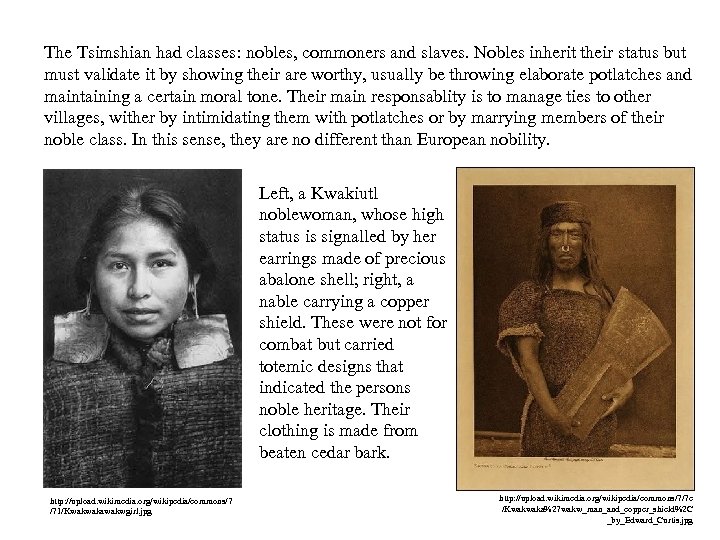

The Tsimshian had classes: nobles, commoners and slaves. Nobles inherit their status but must validate it by showing their are worthy, usually be throwing elaborate potlatches and maintaining a certain moral tone. Their main responsablity is to manage ties to other villages, wither by intimidating them with potlatches or by marrying members of their noble class. In this sense, they are no different than European nobility. Left, a Kwakiutl noblewoman, whose high status is signalled by her earrings made of precious abalone shell; right, a nable carrying a copper shield. These were not for combat but carried totemic designs that indicated the persons noble heritage. Their clothing is made from beaten cedar bark. http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/7 /71/Kwakwakawakwgirl. jpg http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/7/7 c /Kwakwaka%27 wakw_man_and_copper_shield%2 C _by_Edward_Curtis. jpg

The Tsimshian had classes: nobles, commoners and slaves. Nobles inherit their status but must validate it by showing their are worthy, usually be throwing elaborate potlatches and maintaining a certain moral tone. Their main responsablity is to manage ties to other villages, wither by intimidating them with potlatches or by marrying members of their noble class. In this sense, they are no different than European nobility. Left, a Kwakiutl noblewoman, whose high status is signalled by her earrings made of precious abalone shell; right, a nable carrying a copper shield. These were not for combat but carried totemic designs that indicated the persons noble heritage. Their clothing is made from beaten cedar bark. http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/7 /71/Kwakwakawakwgirl. jpg http: //upload. wikimedia. org/wikipedia/commons/7/7 c /Kwakwaka%27 wakw_man_and_copper_shield%2 C _by_Edward_Curtis. jpg

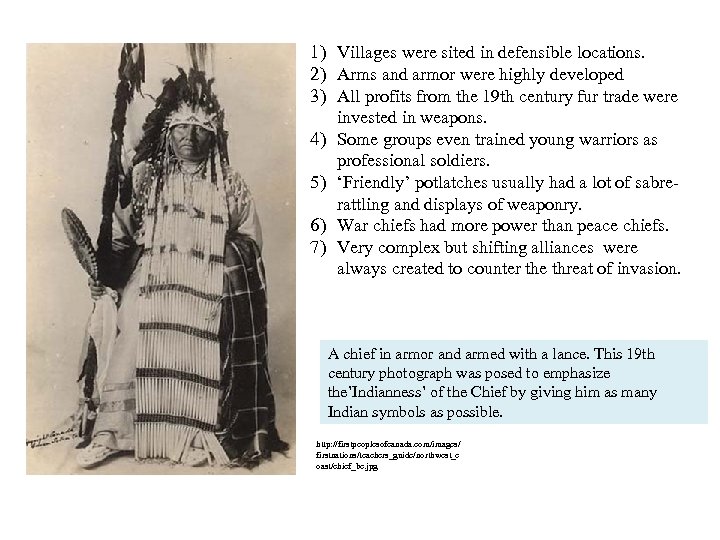

1) Villages were sited in defensible locations. 2) Arms and armor were highly developed 3) All profits from the 19 th century fur trade were invested in weapons. 4) Some groups even trained young warriors as professional soldiers. 5) ‘Friendly’ potlatches usually had a lot of sabrerattling and displays of weaponry. 6) War chiefs had more power than peace chiefs. 7) Very complex but shifting alliances were always created to counter the threat of invasion. A chief in armor and armed with a lance. This 19 th century photograph was posed to emphasize the’Indianness’ of the Chief by giving him as many Indian symbols as possible. http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/ firstnations/teachers_guide/northwest_c oast/chief_bc. jpg

1) Villages were sited in defensible locations. 2) Arms and armor were highly developed 3) All profits from the 19 th century fur trade were invested in weapons. 4) Some groups even trained young warriors as professional soldiers. 5) ‘Friendly’ potlatches usually had a lot of sabrerattling and displays of weaponry. 6) War chiefs had more power than peace chiefs. 7) Very complex but shifting alliances were always created to counter the threat of invasion. A chief in armor and armed with a lance. This 19 th century photograph was posed to emphasize the’Indianness’ of the Chief by giving him as many Indian symbols as possible. http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/ firstnations/teachers_guide/northwest_c oast/chief_bc. jpg

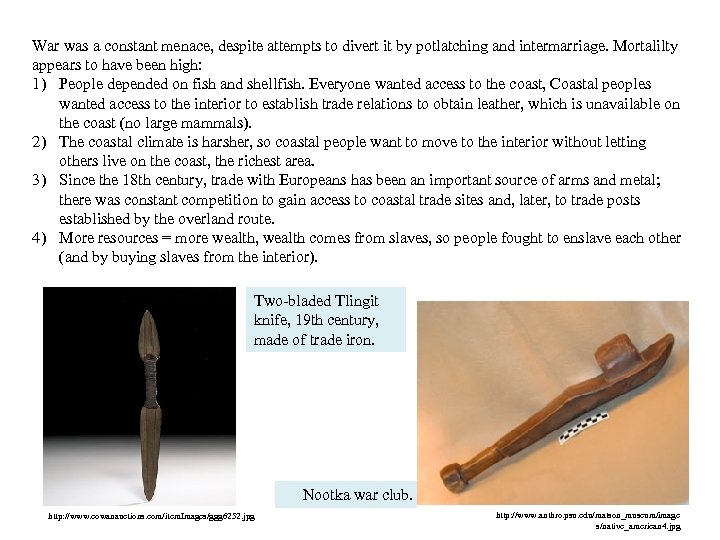

War was a constant menace, despite attempts to divert it by potlatching and intermarriage. Mortalilty appears to have been high: 1) People depended on fish and shellfish. Everyone wanted access to the coast, Coastal peoples wanted access to the interior to establish trade relations to obtain leather, which is unavailable on the coast (no large mammals). 2) The coastal climate is harsher, so coastal people want to move to the interior without letting others live on the coast, the richest area. 3) Since the 18 th century, trade with Europeans has been an important source of arms and metal; there was constant competition to gain access to coastal trade sites and, later, to trade posts established by the overland route. 4) More resources = more wealth, wealth comes from slaves, so people fought to enslave each other (and by buying slaves from the interior). Two-bladed Tlingit knife, 19 th century, made of trade iron. Nootka war club. http: //www. cowanauctions. com/item. Images/ggg 6252. jpg http: //www. anthro. psu. edu/matson_museum/image s/native_american 4. jpg

War was a constant menace, despite attempts to divert it by potlatching and intermarriage. Mortalilty appears to have been high: 1) People depended on fish and shellfish. Everyone wanted access to the coast, Coastal peoples wanted access to the interior to establish trade relations to obtain leather, which is unavailable on the coast (no large mammals). 2) The coastal climate is harsher, so coastal people want to move to the interior without letting others live on the coast, the richest area. 3) Since the 18 th century, trade with Europeans has been an important source of arms and metal; there was constant competition to gain access to coastal trade sites and, later, to trade posts established by the overland route. 4) More resources = more wealth, wealth comes from slaves, so people fought to enslave each other (and by buying slaves from the interior). Two-bladed Tlingit knife, 19 th century, made of trade iron. Nootka war club. http: //www. cowanauctions. com/item. Images/ggg 6252. jpg http: //www. anthro. psu. edu/matson_museum/image s/native_american 4. jpg

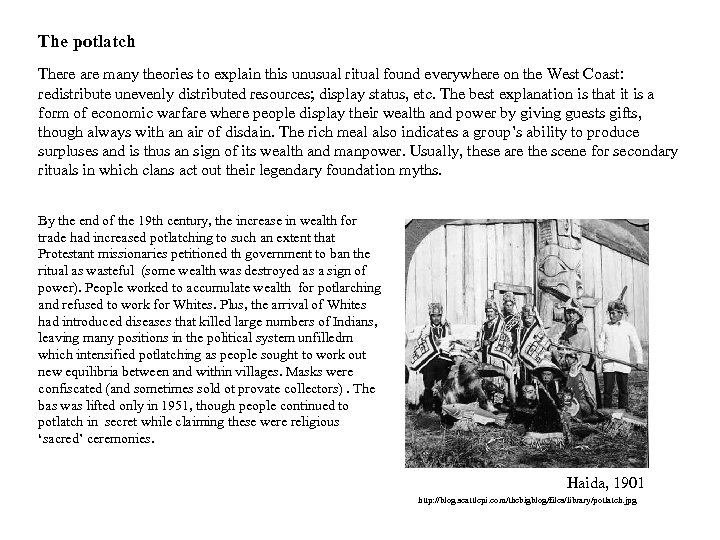

The potlatch There are many theories to explain this unusual ritual found everywhere on the West Coast: redistribute unevenly distributed resources; display status, etc. The best explanation is that it is a form of economic warfare where people display their wealth and power by giving guests gifts, though always with an air of disdain. The rich meal also indicates a group’s ability to produce surpluses and is thus an sign of its wealth and manpower. Usually, these are the scene for secondary rituals in which clans act out their legendary foundation myths. By the end of the 19 th century, the increase in wealth for trade had increased potlatching to such an extent that Protestant missionaries petitioned th government to ban the ritual as wasteful (some wealth was destroyed as a sign of power). People worked to accumulate wealth for potlarching and refused to work for Whites. Plus, the arrival of Whites had introduced diseases that killed large numbers of Indians, leaving many positions in the political system unfilledm which intensified potlatching as people sought to work out new equilibria between and within villages. Masks were confiscated (and sometimes sold ot provate collectors). The bas was lifted only in 1951, though people continued to potlatch in secret while claiming these were religious ‘sacred’ ceremonies. Haida, 1901 http: //blog. seattlepi. com/thebigblog/files/library/potlatch. jpg

The potlatch There are many theories to explain this unusual ritual found everywhere on the West Coast: redistribute unevenly distributed resources; display status, etc. The best explanation is that it is a form of economic warfare where people display their wealth and power by giving guests gifts, though always with an air of disdain. The rich meal also indicates a group’s ability to produce surpluses and is thus an sign of its wealth and manpower. Usually, these are the scene for secondary rituals in which clans act out their legendary foundation myths. By the end of the 19 th century, the increase in wealth for trade had increased potlatching to such an extent that Protestant missionaries petitioned th government to ban the ritual as wasteful (some wealth was destroyed as a sign of power). People worked to accumulate wealth for potlarching and refused to work for Whites. Plus, the arrival of Whites had introduced diseases that killed large numbers of Indians, leaving many positions in the political system unfilledm which intensified potlatching as people sought to work out new equilibria between and within villages. Masks were confiscated (and sometimes sold ot provate collectors). The bas was lifted only in 1951, though people continued to potlatch in secret while claiming these were religious ‘sacred’ ceremonies. Haida, 1901 http: //blog. seattlepi. com/thebigblog/files/library/potlatch. jpg

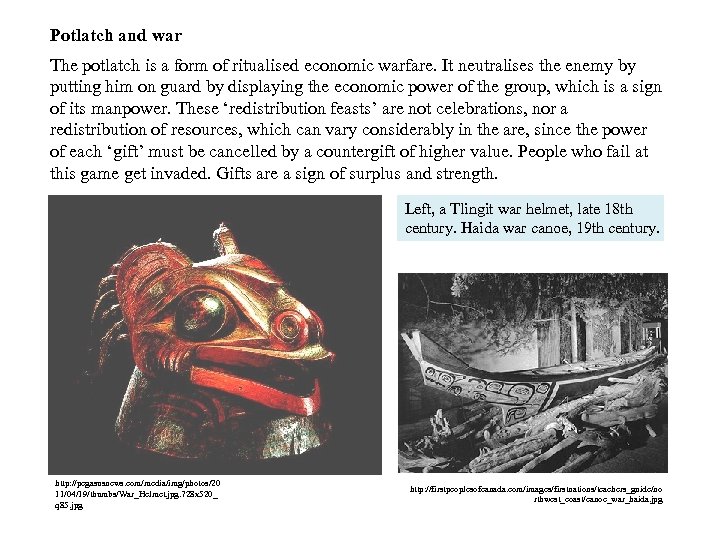

Potlatch and war The potlatch is a form of ritualised economic warfare. It neutralises the enemy by putting him on guard by displaying the economic power of the group, which is a sign of its manpower. These ‘redistribution feasts’ are not celebrations, nor a redistribution of resources, which can vary considerably in the are, since the power of each ‘gift’ must be cancelled by a countergift of higher value. People who fail at this game get invaded. Gifts are a sign of surplus and strength. Left, a Tlingit war helmet, late 18 th century. Haida war canoe, 19 th century. http: //pegasusnews. com/media/img/photos/20 11/04/19/thumbs/War_Helmet. jpg. 728 x 520_ q 85. jpg http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/firstnations/teachers_guide/no rthwest_coast/canoe_war_haida. jpg

Potlatch and war The potlatch is a form of ritualised economic warfare. It neutralises the enemy by putting him on guard by displaying the economic power of the group, which is a sign of its manpower. These ‘redistribution feasts’ are not celebrations, nor a redistribution of resources, which can vary considerably in the are, since the power of each ‘gift’ must be cancelled by a countergift of higher value. People who fail at this game get invaded. Gifts are a sign of surplus and strength. Left, a Tlingit war helmet, late 18 th century. Haida war canoe, 19 th century. http: //pegasusnews. com/media/img/photos/20 11/04/19/thumbs/War_Helmet. jpg. 728 x 520_ q 85. jpg http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/firstnations/teachers_guide/no rthwest_coast/canoe_war_haida. jpg

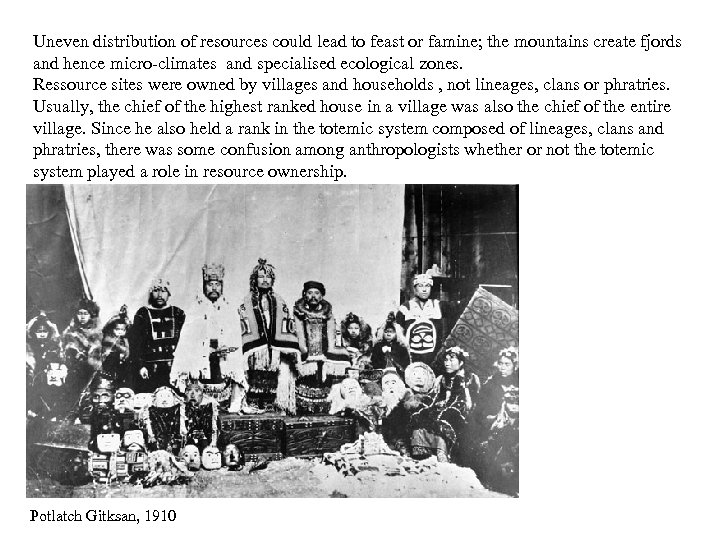

Uneven distribution of resources could lead to feast or famine; the mountains create fjords and hence micro-climates and specialised ecological zones. Ressource sites were owned by villages and households , not lineages, clans or phratries. Usually, the chief of the highest ranked house in a village was also the chief of the entire village. Since he also held a rank in the totemic system composed of lineages, clans and phratries, there was some confusion among anthropologists whether or not the totemic system played a role in resource ownership. Potlatch Gitksan, 1910

Uneven distribution of resources could lead to feast or famine; the mountains create fjords and hence micro-climates and specialised ecological zones. Ressource sites were owned by villages and households , not lineages, clans or phratries. Usually, the chief of the highest ranked house in a village was also the chief of the entire village. Since he also held a rank in the totemic system composed of lineages, clans and phratries, there was some confusion among anthropologists whether or not the totemic system played a role in resource ownership. Potlatch Gitksan, 1910

A contemporary Potlatch

A contemporary Potlatch

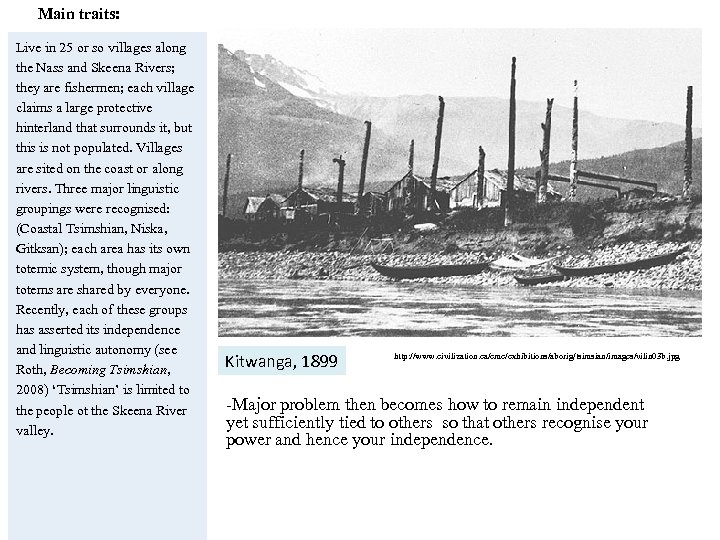

Main traits: Live in 25 or so villages along the Nass and Skeena Rivers; they are fishermen; each village claims a large protective hinterland that surrounds it, but this is not populated. Villages are sited on the coast or along rivers. Three major linguistic groupings were recognised: (Coastal Tsimshian, Niska, Gitksan); each area has its own totemic system, though major totems are shared by everyone. Recently, each of these groups has asserted its independence and linguistic autonomy (see Roth, Becoming Tsimshian, 2008) ‘Tsimshian’ is limited to the people ot the Skeena River valley. Kitwanga, 1899 http: //www. civilization. ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/tsimsian/images/vilin 03 b. jpg -Major problem then becomes how to remain independent yet sufficiently tied to others so that others recognise your power and hence your independence.

Main traits: Live in 25 or so villages along the Nass and Skeena Rivers; they are fishermen; each village claims a large protective hinterland that surrounds it, but this is not populated. Villages are sited on the coast or along rivers. Three major linguistic groupings were recognised: (Coastal Tsimshian, Niska, Gitksan); each area has its own totemic system, though major totems are shared by everyone. Recently, each of these groups has asserted its independence and linguistic autonomy (see Roth, Becoming Tsimshian, 2008) ‘Tsimshian’ is limited to the people ot the Skeena River valley. Kitwanga, 1899 http: //www. civilization. ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/tsimsian/images/vilin 03 b. jpg -Major problem then becomes how to remain independent yet sufficiently tied to others so that others recognise your power and hence your independence.

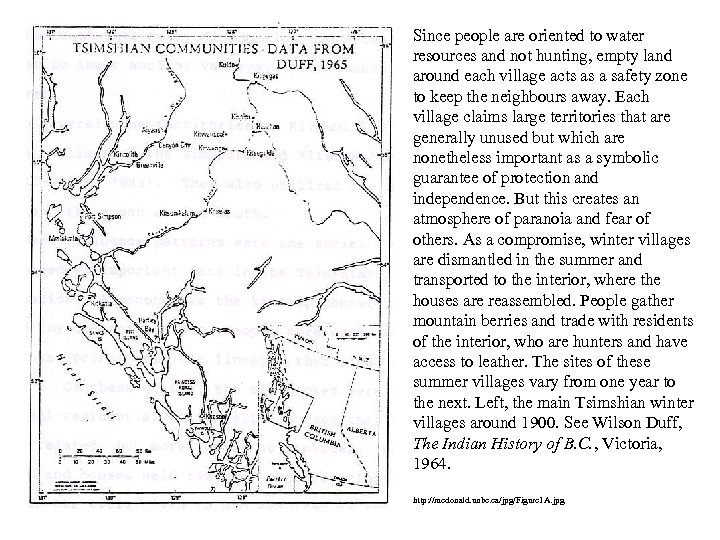

Since people are oriented to water resources and not hunting, empty land around each village acts as a safety zone to keep the neighbours away. Each village claims large territories that are generally unused but which are nonetheless important as a symbolic guarantee of protection and independence. But this creates an atmosphere of paranoia and fear of others. As a compromise, winter villages are dismantled in the summer and transported to the interior, where the houses are reassembled. People gather mountain berries and trade with residents of the interior, who are hunters and have access to leather. The sites of these summer villages vary from one year to the next. Left, the main Tsimshian winter villages around 1900. See Wilson Duff, The Indian History of B. C. , Victoria, 1964. http: //mcdonald. unbc. ca/jpg/Figure 1 A. jpg

Since people are oriented to water resources and not hunting, empty land around each village acts as a safety zone to keep the neighbours away. Each village claims large territories that are generally unused but which are nonetheless important as a symbolic guarantee of protection and independence. But this creates an atmosphere of paranoia and fear of others. As a compromise, winter villages are dismantled in the summer and transported to the interior, where the houses are reassembled. People gather mountain berries and trade with residents of the interior, who are hunters and have access to leather. The sites of these summer villages vary from one year to the next. Left, the main Tsimshian winter villages around 1900. See Wilson Duff, The Indian History of B. C. , Victoria, 1964. http: //mcdonald. unbc. ca/jpg/Figure 1 A. jpg

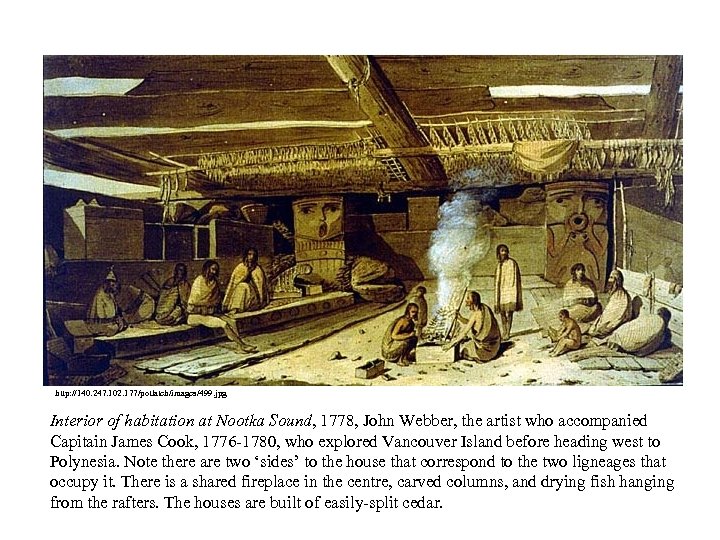

http: //140. 247. 102. 177/potlatch/images/499. jpg Interior of habitation at Nootka Sound, 1778, John Webber, the artist who accompanied Capitain James Cook, 1776 -1780, who explored Vancouver Island before heading west to Polynesia. Note there are two ‘sides’ to the house that correspond to the two ligneages that occupy it. There is a shared fireplace in the centre, carved columns, and drying fish hanging from the rafters. The houses are built of easily-split cedar.

http: //140. 247. 102. 177/potlatch/images/499. jpg Interior of habitation at Nootka Sound, 1778, John Webber, the artist who accompanied Capitain James Cook, 1776 -1780, who explored Vancouver Island before heading west to Polynesia. Note there are two ‘sides’ to the house that correspond to the two ligneages that occupy it. There is a shared fireplace in the centre, carved columns, and drying fish hanging from the rafters. The houses are built of easily-split cedar.

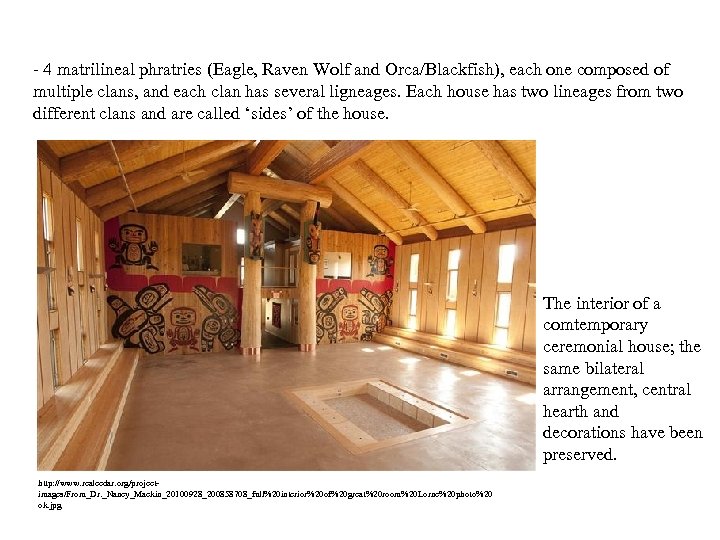

- 4 matrilineal phratries (Eagle, Raven Wolf and Orca/Blackfish), each one composed of multiple clans, and each clan has several ligneages. Each house has two lineages from two different clans and are called ‘sides’ of the house. The interior of a comtemporary ceremonial house; the same bilateral arrangement, central hearth and decorations have been preserved. http: //www. realcedar. org/projectimages/From_Dr. _Nancy_Mackin_20100928_200858708_full%20 interior%20 of%20 great%20 room%20 Lorne%20 photo%20 ok. jpg

- 4 matrilineal phratries (Eagle, Raven Wolf and Orca/Blackfish), each one composed of multiple clans, and each clan has several ligneages. Each house has two lineages from two different clans and are called ‘sides’ of the house. The interior of a comtemporary ceremonial house; the same bilateral arrangement, central hearth and decorations have been preserved. http: //www. realcedar. org/projectimages/From_Dr. _Nancy_Mackin_20100928_200858708_full%20 interior%20 of%20 great%20 room%20 Lorne%20 photo%20 ok. jpg

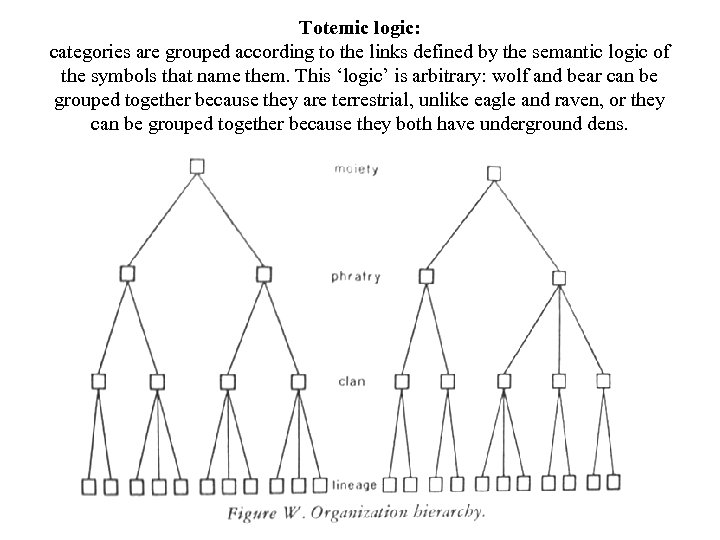

Definitions - a lineage is a group of people descended from a known ancesot, usually three generations (Fr. Fa, Son); can be matrilineal, patrilineal, or bilineal/bilateral/cognatic - a clan is a grouping of lineages or people who claim common descent but who don’t know or don’t bother identifying the founding father or mother. - a phratry is a group of clans united by a shared totemic marker: all ‘bird’ clans are united into a single overarching ‘bird’ phratry - a moiety is when lineages, clans and phratries are united into two categories in a single community or village. - a household is a social category based on a group of people who live together; it is not only demographic: among the Tsimshian, houselholds are named - kindred is a network of people who acknolwedge they are related, but who usually don’t live together nor own or control resources together. - a cognatic clan is a network of people descended from a named couple, who may be several generations removed from the present.

Definitions - a lineage is a group of people descended from a known ancesot, usually three generations (Fr. Fa, Son); can be matrilineal, patrilineal, or bilineal/bilateral/cognatic - a clan is a grouping of lineages or people who claim common descent but who don’t know or don’t bother identifying the founding father or mother. - a phratry is a group of clans united by a shared totemic marker: all ‘bird’ clans are united into a single overarching ‘bird’ phratry - a moiety is when lineages, clans and phratries are united into two categories in a single community or village. - a household is a social category based on a group of people who live together; it is not only demographic: among the Tsimshian, houselholds are named - kindred is a network of people who acknolwedge they are related, but who usually don’t live together nor own or control resources together. - a cognatic clan is a network of people descended from a named couple, who may be several generations removed from the present.

Totemic logic: categories are grouped according to the links defined by the semantic logic of the symbols that name them. This ‘logic’ is arbitrary: wolf and bear can be grouped together because they are terrestrial, unlike eagle and raven, or they can be grouped together because they both have underground dens.

Totemic logic: categories are grouped according to the links defined by the semantic logic of the symbols that name them. This ‘logic’ is arbitrary: wolf and bear can be grouped together because they are terrestrial, unlike eagle and raven, or they can be grouped together because they both have underground dens.

The two dimensions of the Tsimshian community: a) Networks of matrilineal clans, each containing several lineages, assembled into phratries. Each house has two ‘sides’, two lineages belonging to different clans. Clans and phratries are dispersed and are in charge of the totemic symbols (masks, totem poles). The same clans and phratries can be found in several villages, but this does not mean they are politically significant. Villages are the significant poluitical unit. b) A territorial and residential principle: villages, households, and sides of the household. These units own property. Villages and houses are named, and people see other members as allies (unlike clans).

The two dimensions of the Tsimshian community: a) Networks of matrilineal clans, each containing several lineages, assembled into phratries. Each house has two ‘sides’, two lineages belonging to different clans. Clans and phratries are dispersed and are in charge of the totemic symbols (masks, totem poles). The same clans and phratries can be found in several villages, but this does not mean they are politically significant. Villages are the significant poluitical unit. b) A territorial and residential principle: villages, households, and sides of the household. These units own property. Villages and houses are named, and people see other members as allies (unlike clans).

Reasons purporting to explain matrilineal systems: Resources are too concentrated : “… migrating herds of caribou and anadromous fish in the subarctic at times favor as exploitative units large groups of people from different territories, and that uterine, principles are most effective in producing such groups and in ensuring intergroup cooperation and political cohesion. In contrast, scarce, scattered, and isolated resources favor self-sufficient, territorial, agnatic groups. . . p. 20, M. K. Martin, The Foraging Adaptation - Uniformity or Diversity? Addison-Wesley Module in Anthropology 56, 1974. Resources are too dispersed : “… the ethnographic data appear to support the proposal that the aboriginal social organization of the Pacific Drainage Athapaskans had as its basis a matrilineal complex…. This was functionally related to an adaptive strategy emphasizing extensive big-game hunting supplemented by fishing in an environment which required high mobility …” p. 15, E. H. Hosley, “The Aboriginal Social Organization of the Pacific Drainage Dene: The Matrilineal Basis”, Arctic Anthropology 17(2): 12 -16, 1980. Resources are too variable : “We would argue that the most important environmental (viewed broadly so as to include ecological and sociocultural as well as gross environmental factors) variable conducive to the emergence of matriorganization is the general lack of competition and conflict over basic resources. The fact that matriorganization occurs in groups varying widely in subsistence strategies points to its importance under a range of ecological conditions. ” p. 40, C. A. Bishop and S. Krech, III, “Matriorganization: The Basis of Aboriginal Subarctic Social Organization”, Arctic Anthropology 17(2): 34 -45, 1980.

Reasons purporting to explain matrilineal systems: Resources are too concentrated : “… migrating herds of caribou and anadromous fish in the subarctic at times favor as exploitative units large groups of people from different territories, and that uterine, principles are most effective in producing such groups and in ensuring intergroup cooperation and political cohesion. In contrast, scarce, scattered, and isolated resources favor self-sufficient, territorial, agnatic groups. . . p. 20, M. K. Martin, The Foraging Adaptation - Uniformity or Diversity? Addison-Wesley Module in Anthropology 56, 1974. Resources are too dispersed : “… the ethnographic data appear to support the proposal that the aboriginal social organization of the Pacific Drainage Athapaskans had as its basis a matrilineal complex…. This was functionally related to an adaptive strategy emphasizing extensive big-game hunting supplemented by fishing in an environment which required high mobility …” p. 15, E. H. Hosley, “The Aboriginal Social Organization of the Pacific Drainage Dene: The Matrilineal Basis”, Arctic Anthropology 17(2): 12 -16, 1980. Resources are too variable : “We would argue that the most important environmental (viewed broadly so as to include ecological and sociocultural as well as gross environmental factors) variable conducive to the emergence of matriorganization is the general lack of competition and conflict over basic resources. The fact that matriorganization occurs in groups varying widely in subsistence strategies points to its importance under a range of ecological conditions. ” p. 40, C. A. Bishop and S. Krech, III, “Matriorganization: The Basis of Aboriginal Subarctic Social Organization”, Arctic Anthropology 17(2): 34 -45, 1980.

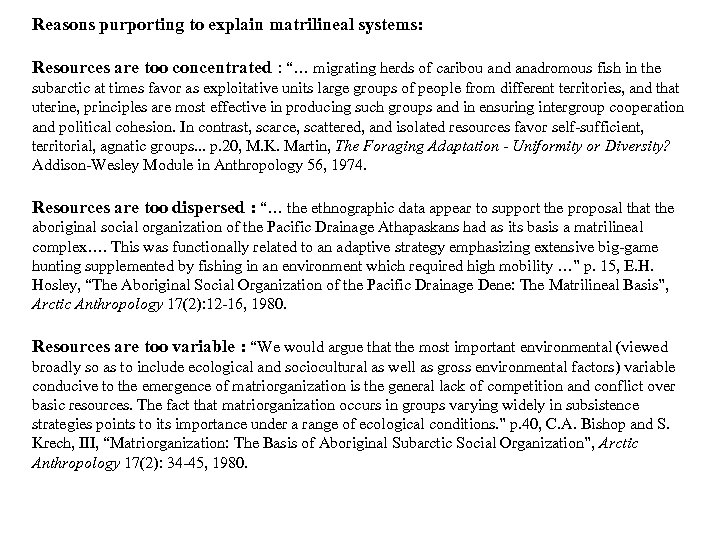

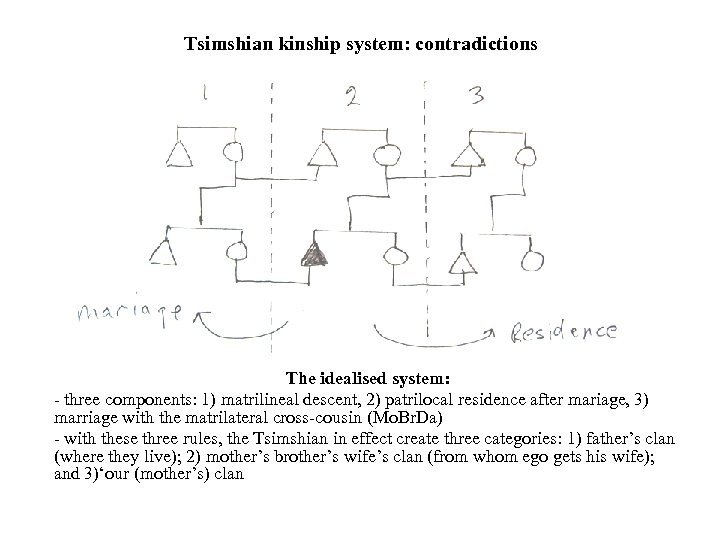

Tsimshian kinship system: contradictions The idealised system: - three components: 1) matrilineal descent, 2) patrilocal residence after mariage, 3) marriage with the matrilateral cross-cousin (Mo. Br. Da) - with these three rules, the Tsimshian in effect create three categories: 1) father’s clan (where they live); 2) mother’s brother’s wife’s clan (from whom ego gets his wife); and 3)‘our (mother’s) clan

Tsimshian kinship system: contradictions The idealised system: - three components: 1) matrilineal descent, 2) patrilocal residence after mariage, 3) marriage with the matrilateral cross-cousin (Mo. Br. Da) - with these three rules, the Tsimshian in effect create three categories: 1) father’s clan (where they live); 2) mother’s brother’s wife’s clan (from whom ego gets his wife); and 3)‘our (mother’s) clan

- Three is the maximum number of categories that emerge from this particular combination of rules: Us, ‘Them 1’ and ‘Them 2’. Any variation in the rules produces a model of the social universe with only two categories, Us and Them. - The Tsimshian create a model of the social universe using closed units, clans, yet each clan is linked to two others, the greatest number possible. http: //www. yukoninfo. com/images/fishinhtools. gif Fishing tools In other words, in ‘real’ life, the Tsimshian are extremely worried about the relations to others, about protecting their hinterland; they alternate between being entirely closed off and javing too much intimacy with others. They create a model of this contradictory reality with the same characteristics: closed and hermitic clans are arranged in such a way (by manipulating the rules) that they are connected to as many others as is mathematically possible. The model is a statement in which all the ambiguities of ‘real’ life are allegedly fixed: villages are permeable but clans are not; nobles marry strangers, so villages are ‘contaminated’, but the rules regularise and limit contact with others. The model is not a guide to the rules of life, but an expression of a complex and contradictory political system.

- Three is the maximum number of categories that emerge from this particular combination of rules: Us, ‘Them 1’ and ‘Them 2’. Any variation in the rules produces a model of the social universe with only two categories, Us and Them. - The Tsimshian create a model of the social universe using closed units, clans, yet each clan is linked to two others, the greatest number possible. http: //www. yukoninfo. com/images/fishinhtools. gif Fishing tools In other words, in ‘real’ life, the Tsimshian are extremely worried about the relations to others, about protecting their hinterland; they alternate between being entirely closed off and javing too much intimacy with others. They create a model of this contradictory reality with the same characteristics: closed and hermitic clans are arranged in such a way (by manipulating the rules) that they are connected to as many others as is mathematically possible. The model is a statement in which all the ambiguities of ‘real’ life are allegedly fixed: villages are permeable but clans are not; nobles marry strangers, so villages are ‘contaminated’, but the rules regularise and limit contact with others. The model is not a guide to the rules of life, but an expression of a complex and contradictory political system.

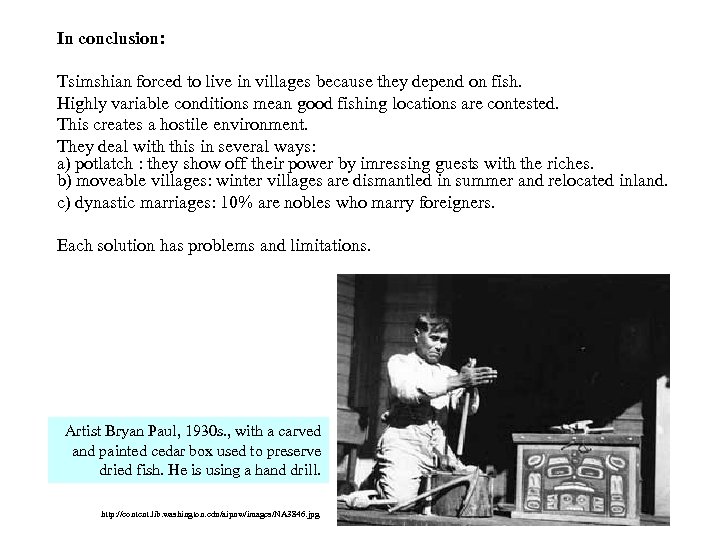

In conclusion: Tsimshian forced to live in villages because they depend on fish. Highly variable conditions mean good fishing locations are contested. This creates a hostile environment. They deal with this in several ways: a) potlatch : they show off their power by imressing guests with the riches. b) moveable villages: winter villages are dismantled in summer and relocated inland. c) dynastic marriages: 10% are nobles who marry foreigners. Each solution has problems and limitations. Artist Bryan Paul, 1930 s. , with a carved and painted cedar box used to preserve dried fish. He is using a hand drill. http: //content. lib. washington. edu/aipnw/images/NA 3846. jpg

In conclusion: Tsimshian forced to live in villages because they depend on fish. Highly variable conditions mean good fishing locations are contested. This creates a hostile environment. They deal with this in several ways: a) potlatch : they show off their power by imressing guests with the riches. b) moveable villages: winter villages are dismantled in summer and relocated inland. c) dynastic marriages: 10% are nobles who marry foreigners. Each solution has problems and limitations. Artist Bryan Paul, 1930 s. , with a carved and painted cedar box used to preserve dried fish. He is using a hand drill. http: //content. lib. washington. edu/aipnw/images/NA 3846. jpg

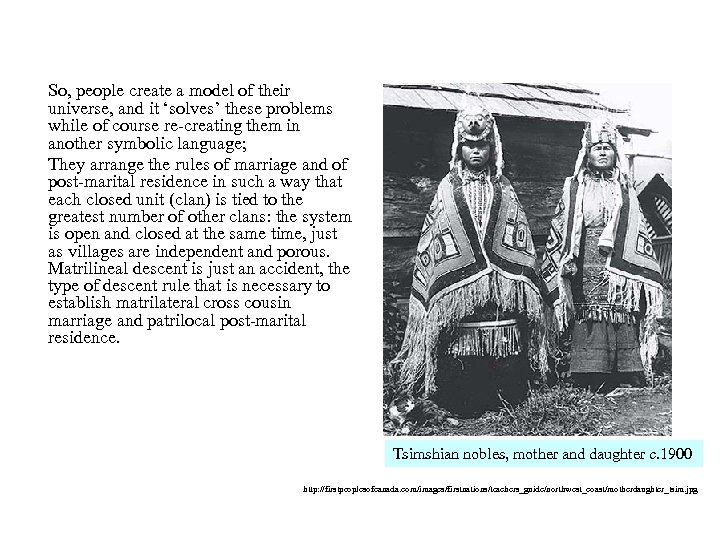

So, people create a model of their universe, and it ‘solves’ these problems while of course re-creating them in another symbolic language; They arrange the rules of marriage and of post-marital residence in such a way that each closed unit (clan) is tied to the greatest number of other clans: the system is open and closed at the same time, just as villages are independent and porous. Matrilineal descent is just an accident, the type of descent rule that is necessary to establish matrilateral cross cousin marriage and patrilocal post-marital residence. Tsimshian nobles, mother and daughter c. 1900 http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/firstnations/teachers_guide/northwest_coast/motherdaughter_tsim. jpg

So, people create a model of their universe, and it ‘solves’ these problems while of course re-creating them in another symbolic language; They arrange the rules of marriage and of post-marital residence in such a way that each closed unit (clan) is tied to the greatest number of other clans: the system is open and closed at the same time, just as villages are independent and porous. Matrilineal descent is just an accident, the type of descent rule that is necessary to establish matrilateral cross cousin marriage and patrilocal post-marital residence. Tsimshian nobles, mother and daughter c. 1900 http: //firstpeoplesofcanada. com/images/firstnations/teachers_guide/northwest_coast/motherdaughter_tsim. jpg

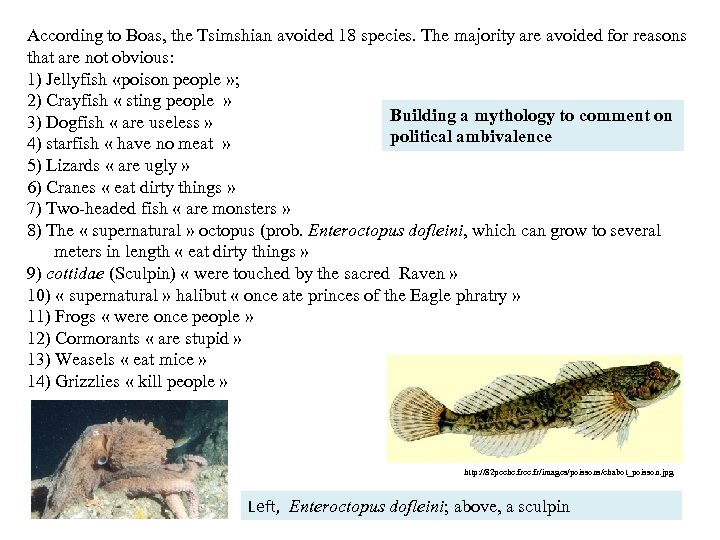

According to Boas, the Tsimshian avoided 18 species. The majority are avoided for reasons that are not obvious: 1) Jellyfish «poison people » ; 2) Crayfish « sting people » Building a mythology to comment on 3) Dogfish « are useless » political ambivalence 4) starfish « have no meat » 5) Lizards « are ugly » 6) Cranes « eat dirty things » 7) Two-headed fish « are monsters » 8) The « supernatural » octopus (prob. Enteroctopus dofleini, which can grow to several meters in length « eat dirty things » 9) cottidae (Sculpin) « were touched by the sacred Raven » 10) « supernatural » halibut « once ate princes of the Eagle phratry » 11) Frogs « were once people » 12) Cormorants « are stupid » 13) Weasels « eat mice » 14) Grizzlies « kill people » http: //82 peche. free. fr/images/poissons/chabot_poisson. jpg Left, Enteroctopus dofleini; above, a sculpin

According to Boas, the Tsimshian avoided 18 species. The majority are avoided for reasons that are not obvious: 1) Jellyfish «poison people » ; 2) Crayfish « sting people » Building a mythology to comment on 3) Dogfish « are useless » political ambivalence 4) starfish « have no meat » 5) Lizards « are ugly » 6) Cranes « eat dirty things » 7) Two-headed fish « are monsters » 8) The « supernatural » octopus (prob. Enteroctopus dofleini, which can grow to several meters in length « eat dirty things » 9) cottidae (Sculpin) « were touched by the sacred Raven » 10) « supernatural » halibut « once ate princes of the Eagle phratry » 11) Frogs « were once people » 12) Cormorants « are stupid » 13) Weasels « eat mice » 14) Grizzlies « kill people » http: //82 peche. free. fr/images/poissons/chabot_poisson. jpg Left, Enteroctopus dofleini; above, a sculpin

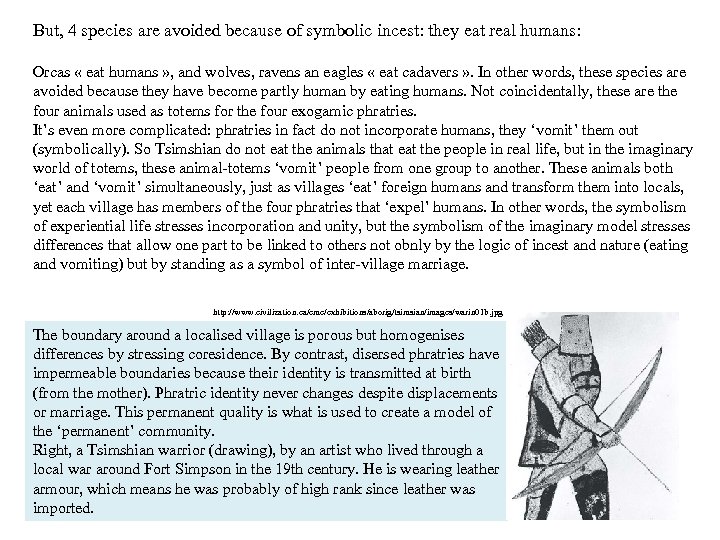

But, 4 species are avoided because of symbolic incest: they eat real humans: Orcas « eat humans » , and wolves, ravens an eagles « eat cadavers » . In other words, these species are avoided because they have become partly human by eating humans. Not coincidentally, these are the four animals used as totems for the four exogamic phratries. It’s even more complicated: phratries in fact do not incorporate humans, they ‘vomit’ them out (symbolically). So Tsimshian do not eat the animals that eat the people in real life, but in the imaginary world of totems, these animal-totems ‘vomit’ people from one group to another. These animals both ‘eat’ and ‘vomit’ simultaneously, just as villages ‘eat’ foreign humans and transform them into locals, yet each village has members of the four phratries that ‘expel’ humans. In other words, the symbolism of experiential life stresses incorporation and unity, but the symbolism of the imaginary model stresses differences that allow one part to be linked to others not obnly by the logic of incest and nature (eating and vomiting) but by standing as a symbol of inter-village marriage. http: //www. civilization. ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/tsimsian/images/warin 01 b. jpg The boundary around a localised village is porous but homogenises differences by stressing coresidence. By contrast, disersed phratries have impermeable boundaries because their identity is transmitted at birth (from the mother). Phratric identity never changes despite displacements or marriage. This permanent quality is what is used to create a model of the ‘permanent’ community. Right, a Tsimshian warrior (drawing), by an artist who lived through a local war around Fort Simpson in the 19 th century. He is wearing leather armour, which means he was probably of high rank since leather was imported.

But, 4 species are avoided because of symbolic incest: they eat real humans: Orcas « eat humans » , and wolves, ravens an eagles « eat cadavers » . In other words, these species are avoided because they have become partly human by eating humans. Not coincidentally, these are the four animals used as totems for the four exogamic phratries. It’s even more complicated: phratries in fact do not incorporate humans, they ‘vomit’ them out (symbolically). So Tsimshian do not eat the animals that eat the people in real life, but in the imaginary world of totems, these animal-totems ‘vomit’ people from one group to another. These animals both ‘eat’ and ‘vomit’ simultaneously, just as villages ‘eat’ foreign humans and transform them into locals, yet each village has members of the four phratries that ‘expel’ humans. In other words, the symbolism of experiential life stresses incorporation and unity, but the symbolism of the imaginary model stresses differences that allow one part to be linked to others not obnly by the logic of incest and nature (eating and vomiting) but by standing as a symbol of inter-village marriage. http: //www. civilization. ca/cmc/exhibitions/aborig/tsimsian/images/warin 01 b. jpg The boundary around a localised village is porous but homogenises differences by stressing coresidence. By contrast, disersed phratries have impermeable boundaries because their identity is transmitted at birth (from the mother). Phratric identity never changes despite displacements or marriage. This permanent quality is what is used to create a model of the ‘permanent’ community. Right, a Tsimshian warrior (drawing), by an artist who lived through a local war around Fort Simpson in the 19 th century. He is wearing leather armour, which means he was probably of high rank since leather was imported.

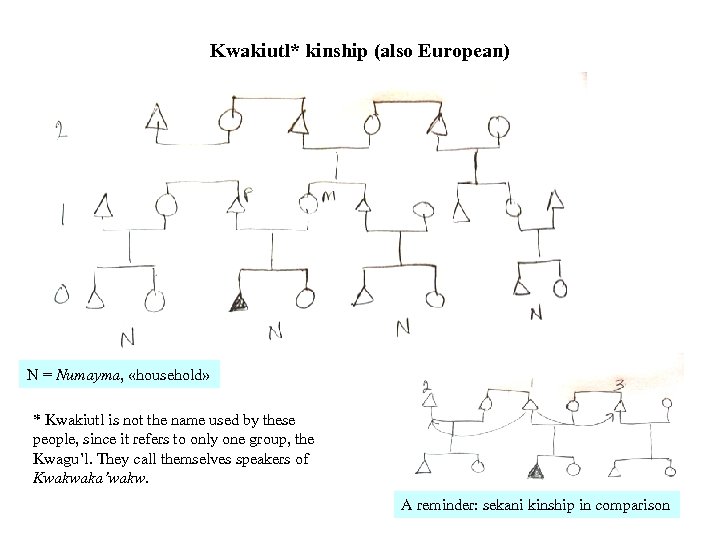

Kwakiutl* kinship (also European) N = Numayma, «household» * Kwakiutl is not the name used by these people, since it refers to only one group, the Kwagu’l. They call themselves speakers of Kwakwaka’wakw. A reminder: sekani kinship in comparison

Kwakiutl* kinship (also European) N = Numayma, «household» * Kwakiutl is not the name used by these people, since it refers to only one group, the Kwagu’l. They call themselves speakers of Kwakwaka’wakw. A reminder: sekani kinship in comparison

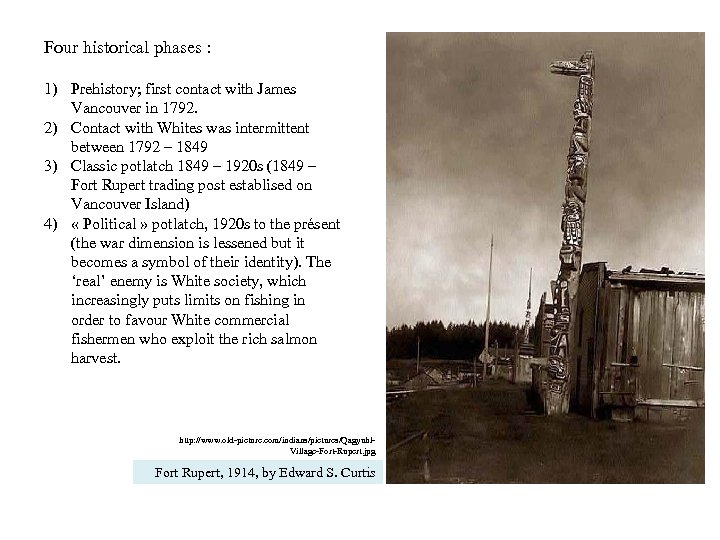

Four historical phases : 1) Prehistory; first contact with James Vancouver in 1792. 2) Contact with Whites was intermittent between 1792 – 1849 3) Classic potlatch 1849 – 1920 s (1849 – Fort Rupert trading post establised on Vancouver Island) 4) « Political » potlatch, 1920 s to the présent (the war dimension is lessened but it becomes a symbol of their identity). The ‘real’ enemy is White society, which increasingly puts limits on fishing in order to favour White commercial fishermen who exploit the rich salmon harvest. http: //www. old-picture. com/indians/pictures/Qagyuhl. Village-Fort-Rupert. jpg Fort Rupert, 1914, by Edward S. Curtis

Four historical phases : 1) Prehistory; first contact with James Vancouver in 1792. 2) Contact with Whites was intermittent between 1792 – 1849 3) Classic potlatch 1849 – 1920 s (1849 – Fort Rupert trading post establised on Vancouver Island) 4) « Political » potlatch, 1920 s to the présent (the war dimension is lessened but it becomes a symbol of their identity). The ‘real’ enemy is White society, which increasingly puts limits on fishing in order to favour White commercial fishermen who exploit the rich salmon harvest. http: //www. old-picture. com/indians/pictures/Qagyuhl. Village-Fort-Rupert. jpg Fort Rupert, 1914, by Edward S. Curtis

![In this system, the numayma (or na’mima, « the [same] type [of person] » In this system, the numayma (or na’mima, « the [same] type [of person] »](https://present5.com/presentation/1a51e256b469031e5e81e53dea281cd1/image-52.jpg) In this system, the numayma (or na’mima, « the [same] type [of person] » , is a cognatic clan composed of the descendents of all four grandparents. The Kwakwaka'wakw are at the northernmost limit of the southern bilateral group, which includes the Nootka [Nuu-chah-nulth], Salish, Bella Coola [Nuxalk], Makah, and Chinooks. To the north of the Kwakwaka'wakw are matrilineal groups: the northern Kwakiutl (Haisla, Wuikinuxv and Heiltsuk; these are three languages linked to Kwakwaka'wakw but are distinct), the Haida, and the Tlingit. http: //www. coastalpeoples. com/media/layout/NWCMap. South. North. Jul 11 FINAL. jpg

In this system, the numayma (or na’mima, « the [same] type [of person] » , is a cognatic clan composed of the descendents of all four grandparents. The Kwakwaka'wakw are at the northernmost limit of the southern bilateral group, which includes the Nootka [Nuu-chah-nulth], Salish, Bella Coola [Nuxalk], Makah, and Chinooks. To the north of the Kwakwaka'wakw are matrilineal groups: the northern Kwakiutl (Haisla, Wuikinuxv and Heiltsuk; these are three languages linked to Kwakwaka'wakw but are distinct), the Haida, and the Tlingit. http: //www. coastalpeoples. com/media/layout/NWCMap. South. North. Jul 11 FINAL. jpg

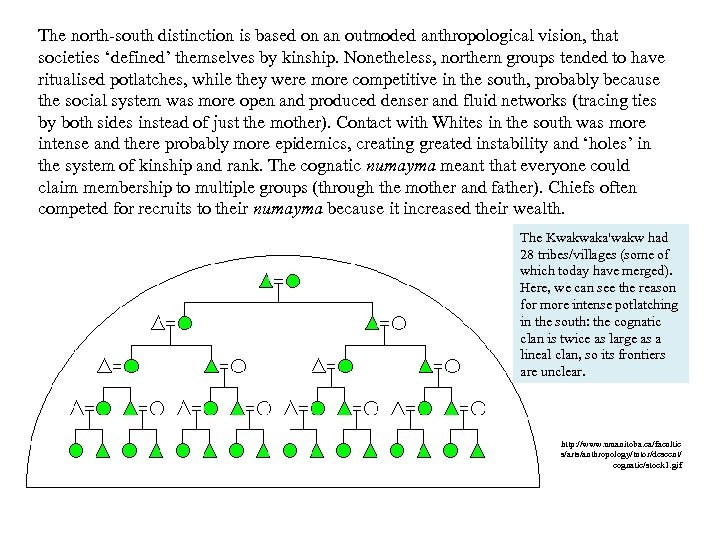

The north-south distinction is based on an outmoded anthropological vision, that societies ‘defined’ themselves by kinship. Nonetheless, northern groups tended to have ritualised potlatches, while they were more competitive in the south, probably because the social system was more open and produced denser and fluid networks (tracing ties by both sides instead of just the mother). Contact with Whites in the south was more intense and there probably more epidemics, creating greated instability and ‘holes’ in the system of kinship and rank. The cognatic numayma meant that everyone could claim membership to multiple groups (through the mother and father). Chiefs often competed for recruits to their numayma because it increased their wealth. The Kwakwaka'wakw had 28 tribes/villages (some of which today have merged). Here, we can see the reason for more intense potlatching in the south: the cognatic clan is twice as large as a lineal clan, so its frontiers are unclear. http: //www. umanitoba. ca/facultie s/arts/anthropology/tutor/descent/ cognatic/stock 1. gif

The north-south distinction is based on an outmoded anthropological vision, that societies ‘defined’ themselves by kinship. Nonetheless, northern groups tended to have ritualised potlatches, while they were more competitive in the south, probably because the social system was more open and produced denser and fluid networks (tracing ties by both sides instead of just the mother). Contact with Whites in the south was more intense and there probably more epidemics, creating greated instability and ‘holes’ in the system of kinship and rank. The cognatic numayma meant that everyone could claim membership to multiple groups (through the mother and father). Chiefs often competed for recruits to their numayma because it increased their wealth. The Kwakwaka'wakw had 28 tribes/villages (some of which today have merged). Here, we can see the reason for more intense potlatching in the south: the cognatic clan is twice as large as a lineal clan, so its frontiers are unclear. http: //www. umanitoba. ca/facultie s/arts/anthropology/tutor/descent/ cognatic/stock 1. gif

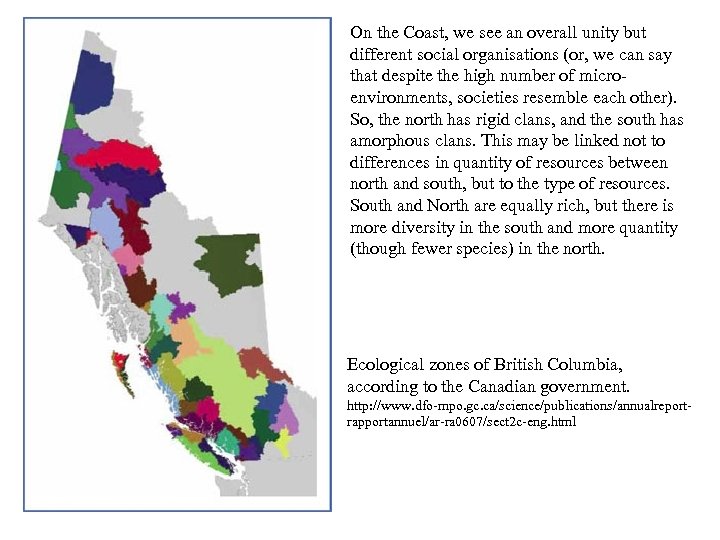

On the Coast, we see an overall unity but different social organisations (or, we can say that despite the high number of microenvironments, societies resemble each other). So, the north has rigid clans, and the south has amorphous clans. This may be linked not to differences in quantity of resources between north and south, but to the type of resources. South and North are equally rich, but there is more diversity in the south and more quantity (though fewer species) in the north. Ecological zones of British Columbia, according to the Canadian government. http: //www. dfo-mpo. gc. ca/science/publications/annualreportrapportannuel/ar-ra 0607/sect 2 c-eng. html

On the Coast, we see an overall unity but different social organisations (or, we can say that despite the high number of microenvironments, societies resemble each other). So, the north has rigid clans, and the south has amorphous clans. This may be linked not to differences in quantity of resources between north and south, but to the type of resources. South and North are equally rich, but there is more diversity in the south and more quantity (though fewer species) in the north. Ecological zones of British Columbia, according to the Canadian government. http: //www. dfo-mpo. gc. ca/science/publications/annualreportrapportannuel/ar-ra 0607/sect 2 c-eng. html

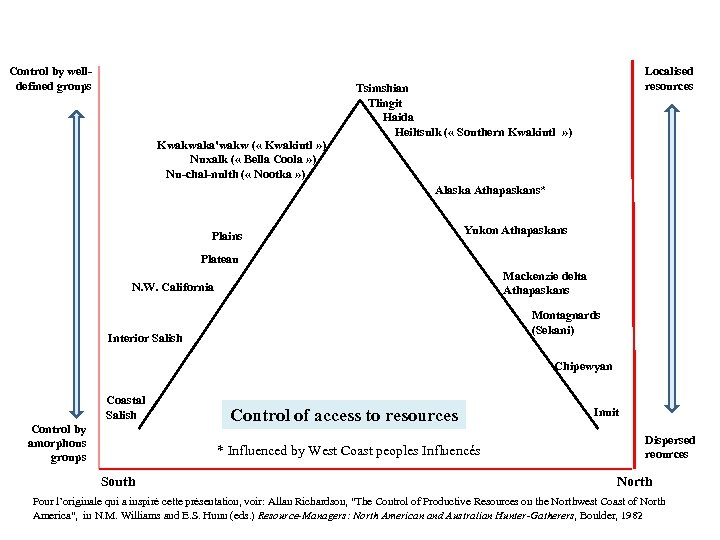

Control by welldefined groups Localised resources Tsimshian Tlingit Haida Heiltsulk ( « Southern Kwakiutl » ) Kwakwaka'wakw ( « Kwakiutl » ) Nuxalk ( « Bella Coola » ) Nu-chal-nulth ( « Nootka » ) Alaska Athapaskans* Plains Yukon Athapaskans Plateau Mackenzie delta Athapaskans N. W. California Montagnards (Sekani) Interior Salish Chipewyan Coastal Salish Control by amorphous groups Control of access to resources * Influenced by West Coast peoples Influencés South Inuit Dispersed reources North Pour l’originale qui a inspiré cette présentation, voir: Allan Richardson, "The Control of Productive Resources on the Northwest Coast of North America", in N. M. Williams and E. S. Hunn (eds. ) Resource-Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers, Boulder, 1982

Control by welldefined groups Localised resources Tsimshian Tlingit Haida Heiltsulk ( « Southern Kwakiutl » ) Kwakwaka'wakw ( « Kwakiutl » ) Nuxalk ( « Bella Coola » ) Nu-chal-nulth ( « Nootka » ) Alaska Athapaskans* Plains Yukon Athapaskans Plateau Mackenzie delta Athapaskans N. W. California Montagnards (Sekani) Interior Salish Chipewyan Coastal Salish Control by amorphous groups Control of access to resources * Influenced by West Coast peoples Influencés South Inuit Dispersed reources North Pour l’originale qui a inspiré cette présentation, voir: Allan Richardson, "The Control of Productive Resources on the Northwest Coast of North America", in N. M. Williams and E. S. Hunn (eds. ) Resource-Managers: North American and Australian Hunter-Gatherers, Boulder, 1982

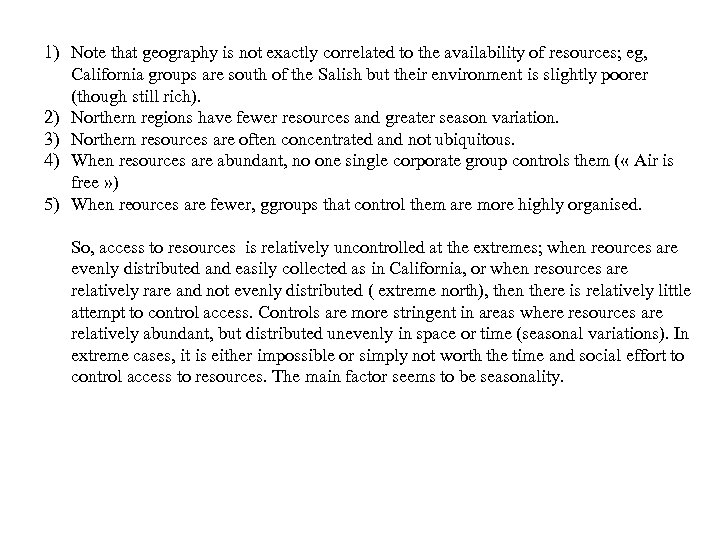

1) Note that geography is not exactly correlated to the availability of resources; eg, California groups are south of the Salish but their environment is slightly poorer (though still rich). 2) Northern regions have fewer resources and greater season variation. 3) Northern resources are often concentrated and not ubiquitous. 4) When resources are abundant, no one single corporate group controls them ( « Air is free » ) 5) When reources are fewer, ggroups that control them are more highly organised. So, access to resources is relatively uncontrolled at the extremes; when reources are evenly distributed and easily collected as in California, or when resources are relatively rare and not evenly distributed ( extreme north), then there is relatively little attempt to control access. Controls are more stringent in areas where resources are relatively abundant, but distributed unevenly in space or time (seasonal variations). In extreme cases, it is either impossible or simply not worth the time and social effort to control access to resources. The main factor seems to be seasonality.

1) Note that geography is not exactly correlated to the availability of resources; eg, California groups are south of the Salish but their environment is slightly poorer (though still rich). 2) Northern regions have fewer resources and greater season variation. 3) Northern resources are often concentrated and not ubiquitous. 4) When resources are abundant, no one single corporate group controls them ( « Air is free » ) 5) When reources are fewer, ggroups that control them are more highly organised. So, access to resources is relatively uncontrolled at the extremes; when reources are evenly distributed and easily collected as in California, or when resources are relatively rare and not evenly distributed ( extreme north), then there is relatively little attempt to control access. Controls are more stringent in areas where resources are relatively abundant, but distributed unevenly in space or time (seasonal variations). In extreme cases, it is either impossible or simply not worth the time and social effort to control access to resources. The main factor seems to be seasonality.