TRANSLATION STUDIES Lecture 2 Lecture outline 1. What

8572-translation_studies.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 22

TRANSLATION STUDIES Lecture 2

TRANSLATION STUDIES Lecture 2

Lecture outline 1. What is translation theory? What is translation studies? 2. Issues of free and literal translation in the history of translation studies. 3. Translation studies in the second half of 20th century. 4. Holmes’ framework of translation studies. 5. New tendencies and trends.

Lecture outline 1. What is translation theory? What is translation studies? 2. Issues of free and literal translation in the history of translation studies. 3. Translation studies in the second half of 20th century. 4. Holmes’ framework of translation studies. 5. New tendencies and trends.

Vilen Komissarov (1990): “As any observable phenomenon, translation can be the object of scientific study aimed at understanding its nature, its components and their interaction as well as various factors influencing it or linked with it in a meaningful way. The science of translation or translatology is concerned both with theoretical and applied aspects of translation studies. A theoretical description of the translation phenomenon is the task of the theory of translation.”

Vilen Komissarov (1990): “As any observable phenomenon, translation can be the object of scientific study aimed at understanding its nature, its components and their interaction as well as various factors influencing it or linked with it in a meaningful way. The science of translation or translatology is concerned both with theoretical and applied aspects of translation studies. A theoretical description of the translation phenomenon is the task of the theory of translation.”

DEFINITIONS: TRANSLATION STUDIES Wikipedia: translation studies is an interdiscipline containing elements of social science and the humanities, dealing with the systematic study of the theory, the description and the application of translation. As an interdisciplinary discipline, translation studies borrows much from the different fields of study that support translation. These include disciplines such as linguistics (especially semantics, pragmatics, applied and contrastive linguistics, cognitive linguistics), modern languages and language studies, comparative literature, cultural studies (including gender studies and postcolonial studies), philosophy (of language and meaning), computer science and, in recent years, sociology and history.

DEFINITIONS: TRANSLATION STUDIES Wikipedia: translation studies is an interdiscipline containing elements of social science and the humanities, dealing with the systematic study of the theory, the description and the application of translation. As an interdisciplinary discipline, translation studies borrows much from the different fields of study that support translation. These include disciplines such as linguistics (especially semantics, pragmatics, applied and contrastive linguistics, cognitive linguistics), modern languages and language studies, comparative literature, cultural studies (including gender studies and postcolonial studies), philosophy (of language and meaning), computer science and, in recent years, sociology and history.

Translation studies (TS): an emerging discipline The last 60 years: TS emerged as a new academic field, at once international and interdisciplinary. A worldwide proliferation of translator training programs offering a variety of certificates and degrees, undergraduate and graduate. This growth has been accompanied by diverse forms of translation research. A flood of academic publishing: training manuals, encyclopedias, journals, conference proceedings, collections of research articles, monographs, primers of theory, and readers.

Translation studies (TS): an emerging discipline The last 60 years: TS emerged as a new academic field, at once international and interdisciplinary. A worldwide proliferation of translator training programs offering a variety of certificates and degrees, undergraduate and graduate. This growth has been accompanied by diverse forms of translation research. A flood of academic publishing: training manuals, encyclopedias, journals, conference proceedings, collections of research articles, monographs, primers of theory, and readers.

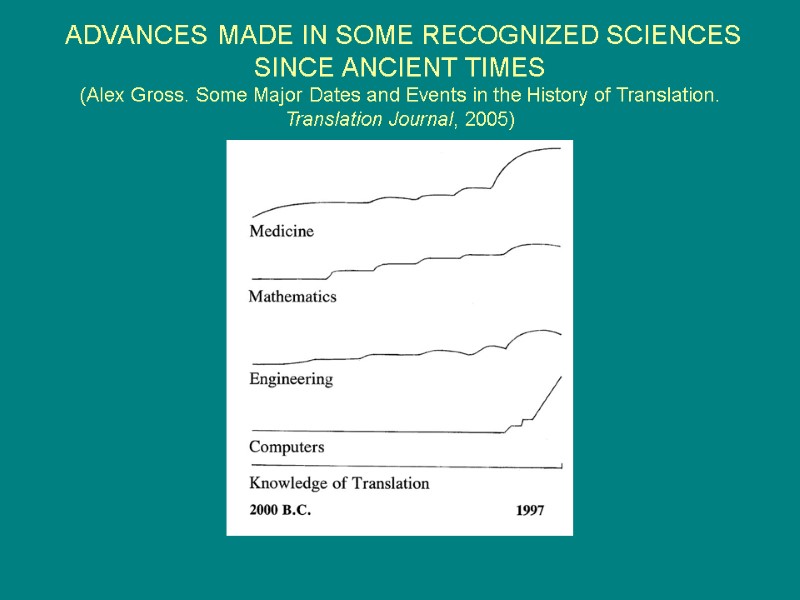

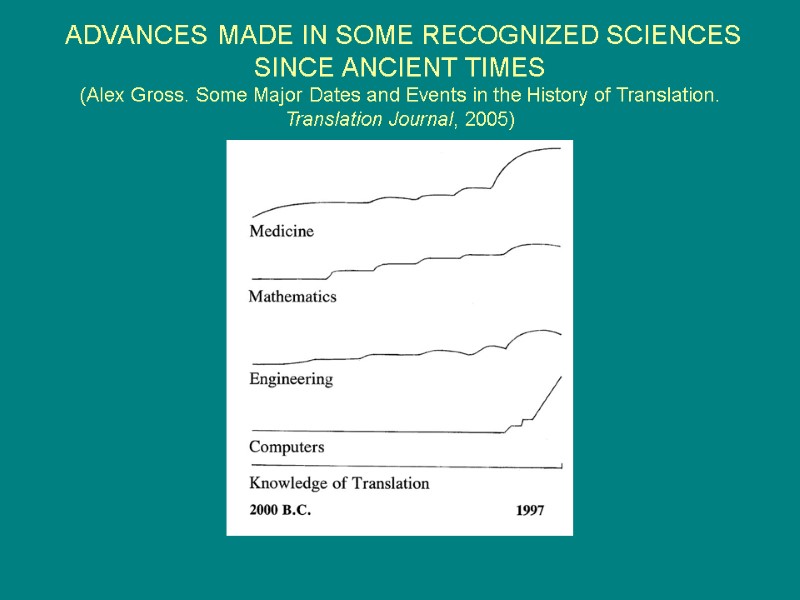

ADVANCES MADE IN SOME RECOGNIZED SCIENCES SINCE ANCIENT TIMES (Alex Gross. Some Major Dates and Events in the History of Translation. Translation Journal, 2005)

ADVANCES MADE IN SOME RECOGNIZED SCIENCES SINCE ANCIENT TIMES (Alex Gross. Some Major Dates and Events in the History of Translation. Translation Journal, 2005)

Why wouldn’t knowledge about translation have developed at a rate comparable to those other sciences? The problems of translation and translatability were known and described thousands of years ago: 1. Was Eve created from Adam’s rib? Genesis in the Old Testament is a Hebrew translation of the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh: "rib" is a pun in the Sumerian original where the word ti means both "rib" and "life-giving.“ When the Sumerian Adam was ill, he was given a goddess meaning both "Rib-Lady" and "Life-Giving Lady." 2. Iamblichus of Chalcis, On the Egyptian Mysteries (ca. 330 A.D.) worked with ancient Egyptian religious texts and attempted to convey their meaning to a more rational Hellenic world. He wrote: “Terms when translated do not always preserve the same meaning; and every nation has certain idioms impossible to express intelligently to others. You may possibly translate them, but they no longer preserve the same force."

Why wouldn’t knowledge about translation have developed at a rate comparable to those other sciences? The problems of translation and translatability were known and described thousands of years ago: 1. Was Eve created from Adam’s rib? Genesis in the Old Testament is a Hebrew translation of the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh: "rib" is a pun in the Sumerian original where the word ti means both "rib" and "life-giving.“ When the Sumerian Adam was ill, he was given a goddess meaning both "Rib-Lady" and "Life-Giving Lady." 2. Iamblichus of Chalcis, On the Egyptian Mysteries (ca. 330 A.D.) worked with ancient Egyptian religious texts and attempted to convey their meaning to a more rational Hellenic world. He wrote: “Terms when translated do not always preserve the same meaning; and every nation has certain idioms impossible to express intelligently to others. You may possibly translate them, but they no longer preserve the same force."

‘WORD-FOR-WORD' OR 'SENSE-FOR-SENSE'? 1st century BCE - the second half of the 20th century: debate over the ‘triad’ of ‘literal’, ‘free’ and ‘faithful’ translation. The distinction between ‘word-for-word’ (i.e. ‘literal’) and ‘sense-for-sense’ (i.e. ‘free’) translation goes back to Cicero, Horace and St Jerome and forms the basis of key writings on translation in centuries nearer to our own. St Jerome, the most famous of all translators, in a work that was to become known as the Latin Vulgate, revised and corrected earlier Latin translations of the New Testament. In 395 CE, St Jerome, defending himself against criticisms of ‘incorrect’ translation, describes his translation strategy in the following terms: “Now I not only admit but freely announce that in translating from the Greek – except of course in the case of the Holy Scripture, where even the syntax contains a mystery – I render not word-for-word, but sense-for-sense.”

‘WORD-FOR-WORD' OR 'SENSE-FOR-SENSE'? 1st century BCE - the second half of the 20th century: debate over the ‘triad’ of ‘literal’, ‘free’ and ‘faithful’ translation. The distinction between ‘word-for-word’ (i.e. ‘literal’) and ‘sense-for-sense’ (i.e. ‘free’) translation goes back to Cicero, Horace and St Jerome and forms the basis of key writings on translation in centuries nearer to our own. St Jerome, the most famous of all translators, in a work that was to become known as the Latin Vulgate, revised and corrected earlier Latin translations of the New Testament. In 395 CE, St Jerome, defending himself against criticisms of ‘incorrect’ translation, describes his translation strategy in the following terms: “Now I not only admit but freely announce that in translating from the Greek – except of course in the case of the Holy Scripture, where even the syntax contains a mystery – I render not word-for-word, but sense-for-sense.”

OVER A MILLENNIUM AFTER St JEROME Within western society, issues of free and literal translation were bound up with the translation of the Bible and other religious and philosophical texts: any translation diverging from the accepted interpretation was likely to be deemed heretical and to be censured or banned. The most famous examples of the tragic deaths of translators who were executed for “translation errors”: the English theologian-translator William Tyndale and the French humanist Etienne Dolet, both burnt at the stake. Dolet was condemned by the theological faculty of Sorbonne in 1546, apparently for adding, in his translation of one of Plato’s dialogues, the phrase rien du tout (‘nothing at all’) in a passage about what existed after death. The addition led to the charge of blasphemy, the assertion being that Dolet did not believe in immortality.

OVER A MILLENNIUM AFTER St JEROME Within western society, issues of free and literal translation were bound up with the translation of the Bible and other religious and philosophical texts: any translation diverging from the accepted interpretation was likely to be deemed heretical and to be censured or banned. The most famous examples of the tragic deaths of translators who were executed for “translation errors”: the English theologian-translator William Tyndale and the French humanist Etienne Dolet, both burnt at the stake. Dolet was condemned by the theological faculty of Sorbonne in 1546, apparently for adding, in his translation of one of Plato’s dialogues, the phrase rien du tout (‘nothing at all’) in a passage about what existed after death. The addition led to the charge of blasphemy, the assertion being that Dolet did not believe in immortality.

MARTIN LUTHER AS A TRANSLATOR A revolution in Bible translation practice: Martin Luther’s translation into East Central German of the New Testament (1522) and later the Old Testament (1534). Luther follows St Jerome in rejecting a word-for-word translation strategy since it would be unable to convey the same meaning as the ST and would sometimes be incomprehensible. His infusion of the Bible with the language of ordinary people and his consideration of translation in terms focusing on the TL and the TT reader were crucial. Luther’s famous quote extols the language of the people: “You must ask the mother at home, the children in the street, the ordinary man in the market and look at their mouths, how they speak, and translate that way; then they’ll understand and see that you’re speaking to them in German.”

MARTIN LUTHER AS A TRANSLATOR A revolution in Bible translation practice: Martin Luther’s translation into East Central German of the New Testament (1522) and later the Old Testament (1534). Luther follows St Jerome in rejecting a word-for-word translation strategy since it would be unable to convey the same meaning as the ST and would sometimes be incomprehensible. His infusion of the Bible with the language of ordinary people and his consideration of translation in terms focusing on the TL and the TT reader were crucial. Luther’s famous quote extols the language of the people: “You must ask the mother at home, the children in the street, the ordinary man in the market and look at their mouths, how they speak, and translate that way; then they’ll understand and see that you’re speaking to them in German.”

EARLY ATTEMPTS AT SYSTEMATIC TRANSLATION THEORY: DRYDEN An English poet and translator, John Dryden (1680), reduces all translation to three categories: (1) ‘metaphrase’: ‘word by word and line by line’ translation, which corresponds to literal translation; (2) ‘paraphrase’: ‘translation with latitude, where the author is kept in view by the translator, so as never to be lost, but his words are not so strictly followed as his sense’; this involves changing whole phrases and more or less corresponds to faithful or sense-for-sense translation; (3) ‘imitation’: ‘forsaking’ both words and sense; this corresponds to very free translation and is more or less adaptation. Dryden criticizes metaphrase: ‘’Tis much like dancing on ropes with fettered legs – a foolish task.’ Imitation, in Dryden’s view, does ‘the greatest wrong . . . to the memory and reputation of the dead’. Dryden thus prefers paraphrase.

EARLY ATTEMPTS AT SYSTEMATIC TRANSLATION THEORY: DRYDEN An English poet and translator, John Dryden (1680), reduces all translation to three categories: (1) ‘metaphrase’: ‘word by word and line by line’ translation, which corresponds to literal translation; (2) ‘paraphrase’: ‘translation with latitude, where the author is kept in view by the translator, so as never to be lost, but his words are not so strictly followed as his sense’; this involves changing whole phrases and more or less corresponds to faithful or sense-for-sense translation; (3) ‘imitation’: ‘forsaking’ both words and sense; this corresponds to very free translation and is more or less adaptation. Dryden criticizes metaphrase: ‘’Tis much like dancing on ropes with fettered legs – a foolish task.’ Imitation, in Dryden’s view, does ‘the greatest wrong . . . to the memory and reputation of the dead’. Dryden thus prefers paraphrase.

Schleiermacher and the valorization of the foreign 1813, Friedrich Schleiermacher wrote a treatise on translation, Ǘber die verschiedenen Methoden des Ǘbersetzens . Schleiermacher distinguishes two different types of translator working on two different types of text. These are: (1) the ‘Dolmetscher’, who translates commercial texts; (2) the ‘Ubersetzer’, who works on scholarly and artistic texts. The real question is how to bring the ST writer and the TT reader together. There are only two paths open for the ‘true’ translator: “Either the translator leaves the writer in peace as much as possible and moves the reader toward him, or he leaves the reader in peace as much as possible and moves the writer toward him. Schleiermacher’s preferred strategy is the first, moving the reader towards the writer, ‘giving the reader, through the translation, the impression he would have received as a German reading the work in the original language’. To achieve this, the translators must adopt an ‘alienating’ (as opposed to ‘naturalizing’) method of translation, orienting themselves by the language and content of the ST. He or she must valorize the foreign and transfer that into the TL. Schleiermacher and Humboldt treated translation as a creative force in which specific translation strategies might serve a variety of cultural and social functions, building languages, literatures, and nations.

Schleiermacher and the valorization of the foreign 1813, Friedrich Schleiermacher wrote a treatise on translation, Ǘber die verschiedenen Methoden des Ǘbersetzens . Schleiermacher distinguishes two different types of translator working on two different types of text. These are: (1) the ‘Dolmetscher’, who translates commercial texts; (2) the ‘Ubersetzer’, who works on scholarly and artistic texts. The real question is how to bring the ST writer and the TT reader together. There are only two paths open for the ‘true’ translator: “Either the translator leaves the writer in peace as much as possible and moves the reader toward him, or he leaves the reader in peace as much as possible and moves the writer toward him. Schleiermacher’s preferred strategy is the first, moving the reader towards the writer, ‘giving the reader, through the translation, the impression he would have received as a German reading the work in the original language’. To achieve this, the translators must adopt an ‘alienating’ (as opposed to ‘naturalizing’) method of translation, orienting themselves by the language and content of the ST. He or she must valorize the foreign and transfer that into the TL. Schleiermacher and Humboldt treated translation as a creative force in which specific translation strategies might serve a variety of cultural and social functions, building languages, literatures, and nations.

TOWARDS CONTEMPORARY TRANSLATION THEORY Translation theory in the second half of the 20th century made various attempts to redefine the concepts ‘literal’ and ‘free’ in operational terms, to describe ‘meaning’ in scientific terms, and to put together systematic taxonomies of translation phenomena. Roman Jakobson (1959) introduces a semiotic reflection on translatability. Jakobson treats meaning not as a reference to reality, but as a relation to a potentially endless chain of signs. He describes translation as a process of receding which “involves two equivalent messages in two different codes.” The Canadian linguists Jean-Paul Vinay and Jean Darbelnet (1958) provide a theoretical basis for a variety of translation methods currently in use. They produce a textbook that has been a staple in translator training programs for over four decades. “Equivalence of messages,” they write, “ultimately relies upon an identity of situations.” They encourage the translator to think of meaning as a cultural construction and to see a close connection between linguistic procedures and “metalinguistic information,” namely “the current state of literature, science, politics etc. of both language communities”.

TOWARDS CONTEMPORARY TRANSLATION THEORY Translation theory in the second half of the 20th century made various attempts to redefine the concepts ‘literal’ and ‘free’ in operational terms, to describe ‘meaning’ in scientific terms, and to put together systematic taxonomies of translation phenomena. Roman Jakobson (1959) introduces a semiotic reflection on translatability. Jakobson treats meaning not as a reference to reality, but as a relation to a potentially endless chain of signs. He describes translation as a process of receding which “involves two equivalent messages in two different codes.” The Canadian linguists Jean-Paul Vinay and Jean Darbelnet (1958) provide a theoretical basis for a variety of translation methods currently in use. They produce a textbook that has been a staple in translator training programs for over four decades. “Equivalence of messages,” they write, “ultimately relies upon an identity of situations.” They encourage the translator to think of meaning as a cultural construction and to see a close connection between linguistic procedures and “metalinguistic information,” namely “the current state of literature, science, politics etc. of both language communities”.

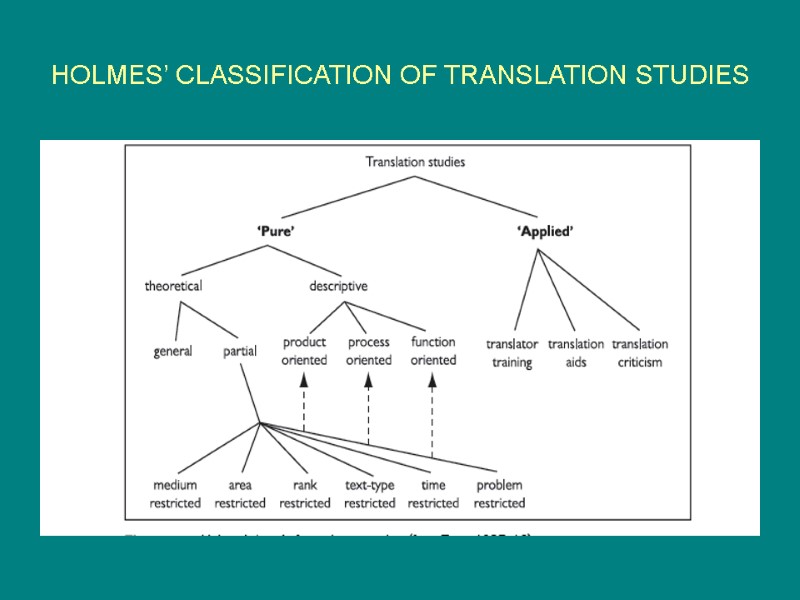

1960s-1970s During the 1960s-1970s the controlling concept for translation theory is equivalence. In 1963 Georges Mounin argues that equivalence is based on “universals” of language and culture. Studying equivalence, translation theorists discover the existence of “shifts” between the foreign and translated texts, deviations that can occur in several linguistic levels and categories. J.C.Catford (1965) оffers a precise description of grammatical and lexical shifts, as well as “departures from formal correspondence.”. The expansion of translation research in the 1960s and 1970s coincides with an increased awareness that it represents an emerging academic discipline. Eugene Nida calls these new theoretical works a “science” of translation. A seminal paper in the development of the field as a distinct discipline was James S. Holmes’s ‘The name and nature of translation studies’ (1972). Holmes draws attention to the limitations imposed at the time by the fact that translation research was dispersed across older disciplines. Crucially, Holmes puts forward an overall framework, describing what translation studies covers. This framework has subsequently been presented by the leading Israeli translation scholar Gideon Toury in the following way:

1960s-1970s During the 1960s-1970s the controlling concept for translation theory is equivalence. In 1963 Georges Mounin argues that equivalence is based on “universals” of language and culture. Studying equivalence, translation theorists discover the existence of “shifts” between the foreign and translated texts, deviations that can occur in several linguistic levels and categories. J.C.Catford (1965) оffers a precise description of grammatical and lexical shifts, as well as “departures from formal correspondence.”. The expansion of translation research in the 1960s and 1970s coincides with an increased awareness that it represents an emerging academic discipline. Eugene Nida calls these new theoretical works a “science” of translation. A seminal paper in the development of the field as a distinct discipline was James S. Holmes’s ‘The name and nature of translation studies’ (1972). Holmes draws attention to the limitations imposed at the time by the fact that translation research was dispersed across older disciplines. Crucially, Holmes puts forward an overall framework, describing what translation studies covers. This framework has subsequently been presented by the leading Israeli translation scholar Gideon Toury in the following way:

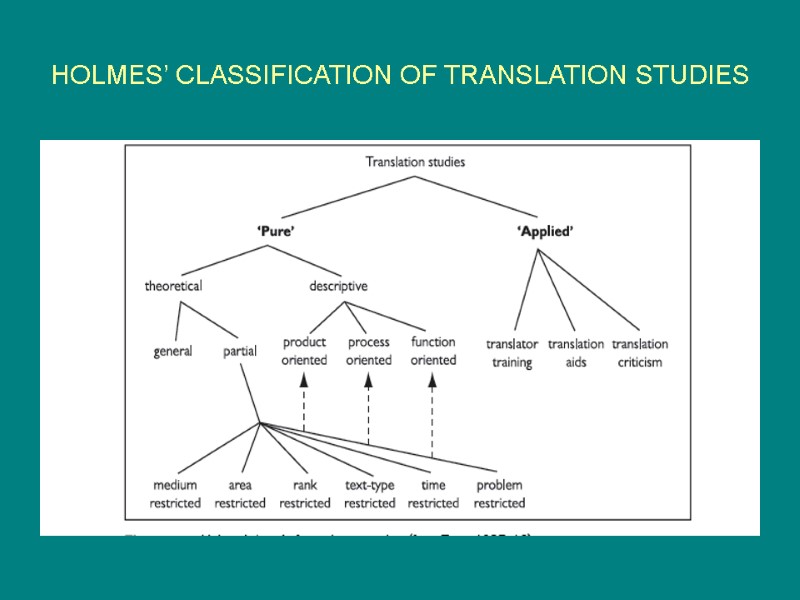

HOLMES’ CLASSIFICATION OF TRANSLATION STUDIES

HOLMES’ CLASSIFICATION OF TRANSLATION STUDIES

In Holmes’s explanations of this framework, the objectives of the ‘pure’ areas of research are: (1) the establishment of general principles to explain and predict the phenomena of translation (translation theory); The ‘theoretical’ branch is divided into general and partial theories. By ‘general’, Holmes is referring to those writings that seek to describe or account for every type of translation and to make generalizations that will be relevant for translation as a whole. ‘Partial’ theoretical studies are restricted according to certain parameters. Medium-restricted theories subdivide according to translation by machine and humans, with further subdivisions according to whether the machine/computer is working alone or as an aid to the human translator, to whether the human translation is written or spoken and to whether spoken translation (interpreting) is consecutive or simultaneous. Area-restricted theories are restricted to specific languages or groups of languages and/or cultures. Holmes notes that language-restricted theories are closely related to work in contrastive linguistics and stylistics. Rank-restricted theories are linguistic theories that have been restricted to a specific level of (normally) the word or sentence. At the time Holmes was writing, there was already a trend towards text linguistics, i.e. text-rank analysis, which has since become far more popular. Text-type restricted theories look at specific discourse types or genres; e.g. literary, business and technical translation. Text-type approaches came to prominence with the work of Reiss and Vermeer, amongst others, in the 1970s. The term time-restricted refers to theories and translations limited according to specific time frames and periods. The history of translation falls into this category. Problem-restricted theories can refer to specific problems such as equivalence – a key issue of the 1960s and 1970s – or to a wider question of whether universals of translated language exist.

In Holmes’s explanations of this framework, the objectives of the ‘pure’ areas of research are: (1) the establishment of general principles to explain and predict the phenomena of translation (translation theory); The ‘theoretical’ branch is divided into general and partial theories. By ‘general’, Holmes is referring to those writings that seek to describe or account for every type of translation and to make generalizations that will be relevant for translation as a whole. ‘Partial’ theoretical studies are restricted according to certain parameters. Medium-restricted theories subdivide according to translation by machine and humans, with further subdivisions according to whether the machine/computer is working alone or as an aid to the human translator, to whether the human translation is written or spoken and to whether spoken translation (interpreting) is consecutive or simultaneous. Area-restricted theories are restricted to specific languages or groups of languages and/or cultures. Holmes notes that language-restricted theories are closely related to work in contrastive linguistics and stylistics. Rank-restricted theories are linguistic theories that have been restricted to a specific level of (normally) the word or sentence. At the time Holmes was writing, there was already a trend towards text linguistics, i.e. text-rank analysis, which has since become far more popular. Text-type restricted theories look at specific discourse types or genres; e.g. literary, business and technical translation. Text-type approaches came to prominence with the work of Reiss and Vermeer, amongst others, in the 1970s. The term time-restricted refers to theories and translations limited according to specific time frames and periods. The history of translation falls into this category. Problem-restricted theories can refer to specific problems such as equivalence – a key issue of the 1960s and 1970s – or to a wider question of whether universals of translated language exist.

(2) The other branch of ‘pure’ research in Holmes’s map is descriptive. Descriptive translation studies (DTS) has three possible foci: examination of (A) the product, (B) the process and (C) the function: (A) Product-oriented DTS examines existing translations. This can involve the description or analysis of a single ST–TT pair or a comparative analysis of several TTs of the same ST (into one or more TLs). These smaller-scale studies can build up into a larger body of translation analysis looking at a specific period, language or text/discourse type. Larger-scale studies can be either diachronic (following development over time) or synchronic (at a single point or period in time) and, as Holmes foresees, ‘one of the eventual goals of product-oriented DTS might possibly be a general history of translations – however ambitious such a goal might sound at this time’. (B) Process-oriented DTS in Holmes’s framework is concerned with the psychology of translation, i.e. with trying to find out what happens in the mind of a translator. Despite later work from a cognitive perspective including think-aloud protocols (where recordings are made of translators’ verbalization of the translation process as they translate), this is an area of research which is only now being systematically analysed. (C) Function-oriented DTS describes the function of translations in the recipient sociocultural situation. Issues that may be researched include which books were translated when and where, and what influences they exerted. This area of cultural-studies-oriented translation – was less researched at the time of Holmes’s paper but is more popular in current work on translation studies.

(2) The other branch of ‘pure’ research in Holmes’s map is descriptive. Descriptive translation studies (DTS) has three possible foci: examination of (A) the product, (B) the process and (C) the function: (A) Product-oriented DTS examines existing translations. This can involve the description or analysis of a single ST–TT pair or a comparative analysis of several TTs of the same ST (into one or more TLs). These smaller-scale studies can build up into a larger body of translation analysis looking at a specific period, language or text/discourse type. Larger-scale studies can be either diachronic (following development over time) or synchronic (at a single point or period in time) and, as Holmes foresees, ‘one of the eventual goals of product-oriented DTS might possibly be a general history of translations – however ambitious such a goal might sound at this time’. (B) Process-oriented DTS in Holmes’s framework is concerned with the psychology of translation, i.e. with trying to find out what happens in the mind of a translator. Despite later work from a cognitive perspective including think-aloud protocols (where recordings are made of translators’ verbalization of the translation process as they translate), this is an area of research which is only now being systematically analysed. (C) Function-oriented DTS describes the function of translations in the recipient sociocultural situation. Issues that may be researched include which books were translated when and where, and what influences they exerted. This area of cultural-studies-oriented translation – was less researched at the time of Holmes’s paper but is more popular in current work on translation studies.

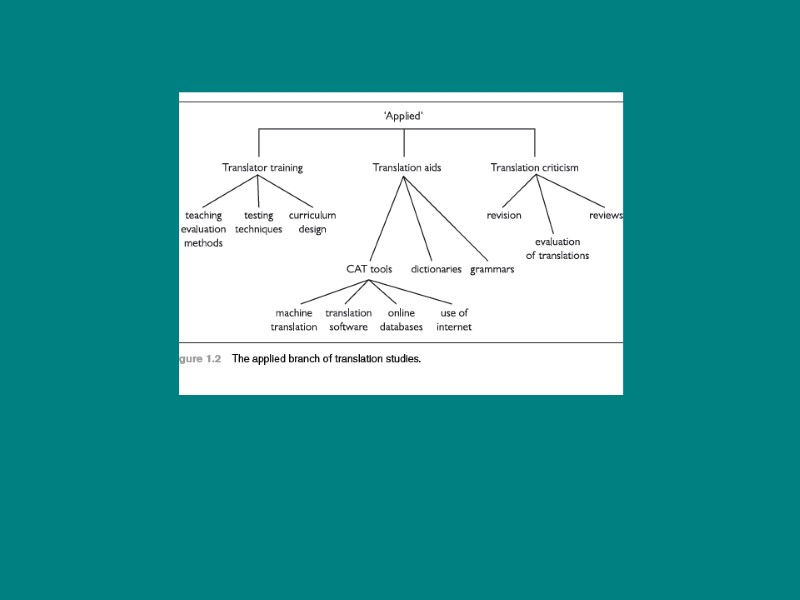

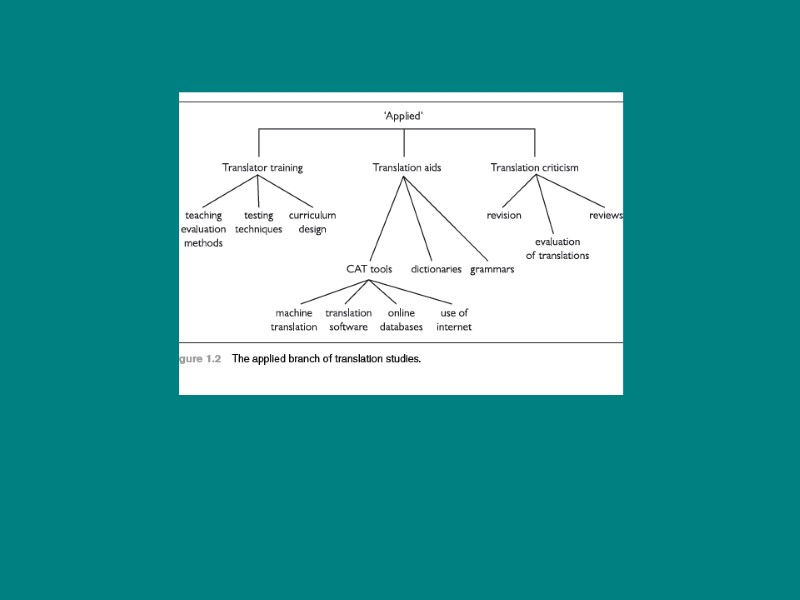

The ‘applied’ branch of Holmes’s framework concerns: - translator training: teaching methods, testing techniques, curriculum design; - translation aids: dictionaries, grammars and information technology; - translation criticism: the evaluation of translations, including the marking of student translations and the reviews of published translations. Another area Holmes mentions is translation policy, where he sees the translation scholar advising on the place of translation in society, including what place, if any, it should occupy in the language teaching and learning curriculum.

The ‘applied’ branch of Holmes’s framework concerns: - translator training: teaching methods, testing techniques, curriculum design; - translation aids: dictionaries, grammars and information technology; - translation criticism: the evaluation of translations, including the marking of student translations and the reviews of published translations. Another area Holmes mentions is translation policy, where he sees the translation scholar advising on the place of translation in society, including what place, if any, it should occupy in the language teaching and learning curriculum.

The crucial role played by Holmes’s paper is in the delineation of the potential of translation studies. The map is still often employed as a point of departure, even if subsequent theoretical discussions have attempted to rewrite parts of it. The theoretical, descriptive and applied areas do influence one another. The main merit of the divisions is that they allow a clarification and a division of labour between the various areas of translation studies which, in the past, have often been confused.

The crucial role played by Holmes’s paper is in the delineation of the potential of translation studies. The map is still often employed as a point of departure, even if subsequent theoretical discussions have attempted to rewrite parts of it. The theoretical, descriptive and applied areas do influence one another. The main merit of the divisions is that they allow a clarification and a division of labour between the various areas of translation studies which, in the past, have often been confused.

DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE 1980s In the 1980s translation studies are regarded as a separate discipline, overlapping with linguistics, literary criticism, and philosophy, but exploring unique problems of cross-cultural communication. Hans Vermeer highlights the translator’s skopos or aim as a decisive factor in a translation рroject. He conceives of the skopos as a complexly defined intention whose textual realization may diverge widely from the source text so as to reach a “set of addressees” in the target culture. Within translation studies, Skopostheorie most resembles the target orientation associated with polysystem theory. Australia and the UK (early 1990s): the view of language as a communicative act in a sociocultural context came to prominence, and was applied to translation in a series of works by scholars such as Bell (1991), Baker (1992) and Hatim and Mason (1990, 1997). Itamar Even-Zohar and Gideon Toury (Israel) have pursued the idea of the literary polysystem in which, amongst other things, different literatures and genres, including translated and nontranslated works, compete for dominance (polysystemic approach). The 1990s saw the incorporation of new schools and concepts, with Canadian-based translation and gender research led by Sherry Simon, the Brazilian cannibalist school promoted by Else Vieira, postcolonial translation theory developed by the Bengali scholars Tejaswini Niranjana and Gayatri Spivak and, in the USA, the cultural studies-oriented analysis of Lawrence Venuti, calling for greater visibility and recognition of the translator. The first decade of the new millennium: special interest devoted to translation, globalization and resistance (Cronin 2003, Baker 2006), the sociology and historiography of translation (e.g. Inghilleri 2005a, Wolf and Fukari 2007) and the interest in new technologies that have given rise to audiovisual translation, localization and corpus-based translation studies.

DEVELOPMENTS SINCE THE 1980s In the 1980s translation studies are regarded as a separate discipline, overlapping with linguistics, literary criticism, and philosophy, but exploring unique problems of cross-cultural communication. Hans Vermeer highlights the translator’s skopos or aim as a decisive factor in a translation рroject. He conceives of the skopos as a complexly defined intention whose textual realization may diverge widely from the source text so as to reach a “set of addressees” in the target culture. Within translation studies, Skopostheorie most resembles the target orientation associated with polysystem theory. Australia and the UK (early 1990s): the view of language as a communicative act in a sociocultural context came to prominence, and was applied to translation in a series of works by scholars such as Bell (1991), Baker (1992) and Hatim and Mason (1990, 1997). Itamar Even-Zohar and Gideon Toury (Israel) have pursued the idea of the literary polysystem in which, amongst other things, different literatures and genres, including translated and nontranslated works, compete for dominance (polysystemic approach). The 1990s saw the incorporation of new schools and concepts, with Canadian-based translation and gender research led by Sherry Simon, the Brazilian cannibalist school promoted by Else Vieira, postcolonial translation theory developed by the Bengali scholars Tejaswini Niranjana and Gayatri Spivak and, in the USA, the cultural studies-oriented analysis of Lawrence Venuti, calling for greater visibility and recognition of the translator. The first decade of the new millennium: special interest devoted to translation, globalization and resistance (Cronin 2003, Baker 2006), the sociology and historiography of translation (e.g. Inghilleri 2005a, Wolf and Fukari 2007) and the interest in new technologies that have given rise to audiovisual translation, localization and corpus-based translation studies.

INTERDISCIPLINARITY OF TRANSLATION STUDIES A notable characteristic has been the interdisciplinarity of recent research. Willard McCarty’s paper ‘Humanities computing as interdiscipline’ (1999) gives the following description of the role of an interdiscipline in academic society: “A true interdiscipline is . . . an entity that exists in the interstices of the existing fields, dealing with some, many or all of them. It is the Phoenician trader among the settled nations. Its existence is enigmatic in such a world; the enigma challenges us to rethink how we organise and institutionalise knowledge”. The relationship of translation studies to other disciplines is not fixed: there are changes from a strong link to contrastive linguistics in the 1960s to the present focus on more cultural studies perspectives and even the recent shift towards areas such as computing and media . Notable are relationships in the area of applied translation studies, such as translator training, as well as an ever-increasing input from information technology to cover issues in computer-assisted translation.

INTERDISCIPLINARITY OF TRANSLATION STUDIES A notable characteristic has been the interdisciplinarity of recent research. Willard McCarty’s paper ‘Humanities computing as interdiscipline’ (1999) gives the following description of the role of an interdiscipline in academic society: “A true interdiscipline is . . . an entity that exists in the interstices of the existing fields, dealing with some, many or all of them. It is the Phoenician trader among the settled nations. Its existence is enigmatic in such a world; the enigma challenges us to rethink how we organise and institutionalise knowledge”. The relationship of translation studies to other disciplines is not fixed: there are changes from a strong link to contrastive linguistics in the 1960s to the present focus on more cultural studies perspectives and even the recent shift towards areas such as computing and media . Notable are relationships in the area of applied translation studies, such as translator training, as well as an ever-increasing input from information technology to cover issues in computer-assisted translation.