2cd8eddb80ba7dc0713bce6ff2061765.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 101

Transfer-based MT

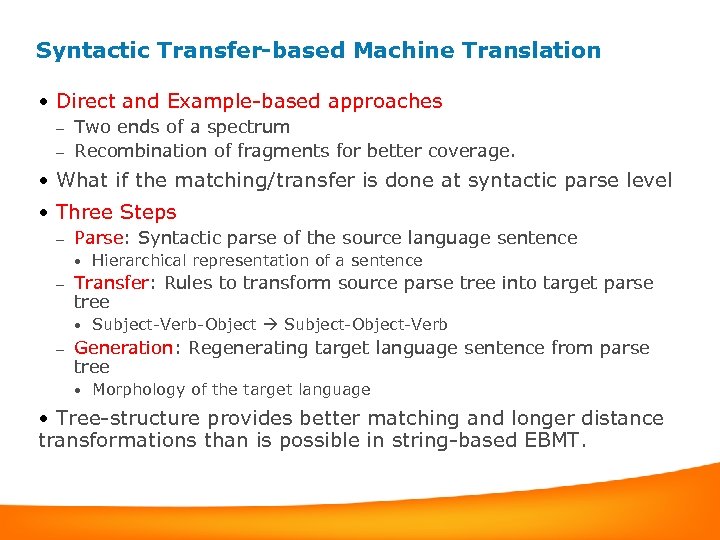

Syntactic Transfer-based Machine Translation • Direct and Example-based approaches Two ends of a spectrum – Recombination of fragments for better coverage. – • What if the matching/transfer is done at syntactic parse level • Three Steps – Parse: Syntactic parse of the source language sentence • – Transfer: Rules to transform source parse tree into target parse tree • – Hierarchical representation of a sentence Subject-Verb-Object Subject-Object-Verb Generation: Regenerating target language sentence from parse tree • Morphology of the target language • Tree-structure provides better matching and longer distance transformations than is possible in string-based EBMT.

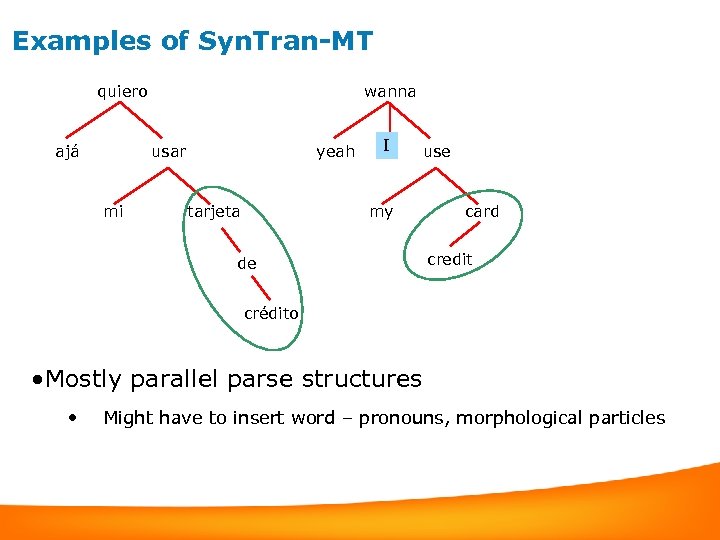

Examples of Syn. Tran-MT quiero ajá wanna usar mi yeah tarjeta I use my de card credit crédito • Mostly parallel parse structures • Might have to insert word – pronouns, morphological particles

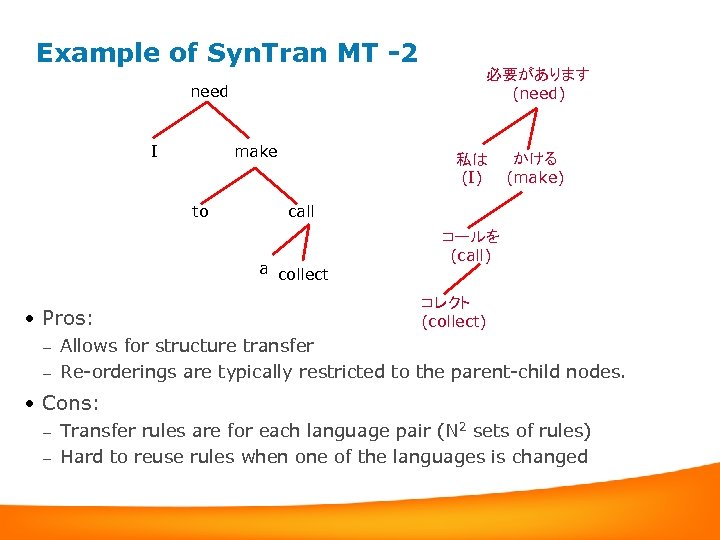

Example of Syn. Tran MT -2 need I make to 私は (I) かける (make) call a collect • Pros: 必要があります (need) コールを (call) コレクト (collect) Allows for structure transfer – Re-orderings are typically restricted to the parent-child nodes. – • Cons: Transfer rules are for each language pair (N 2 sets of rules) – Hard to reuse rules when one of the languages is changed –

Lexical-semantic Divergences Linguistic Divergences • Structural differences between languages – Categorical Divergence • Translation of words in one language into words that have different parts of speech in another language – To be jealous – Tener celos (To have jealousy)

Issues Linguistic Divergences – Conflational Divergence • Translation of two or more words in one language into one word in another language – To kick – Dar una patada (Give a kick)

Issues Linguistic Divergences – Structural Divergence • Realization of verb arguments in different syntactic configurations in different languages – To enter the house – Entrar en la casa (Enter in the house)

Issues Linguistic Divergences – Head-Swapping Divergence • Inversion of a structural-dominance relation between two semantically equivalent words – To run in – Entrar corriendo (Enter running)

Issues Linguistic Divergences – Thematic Divergence • Realization of verb arguments that reflect different thematic to syntactic mapping orders – I like grapes – Me gustan uvas (To-me please grapes)

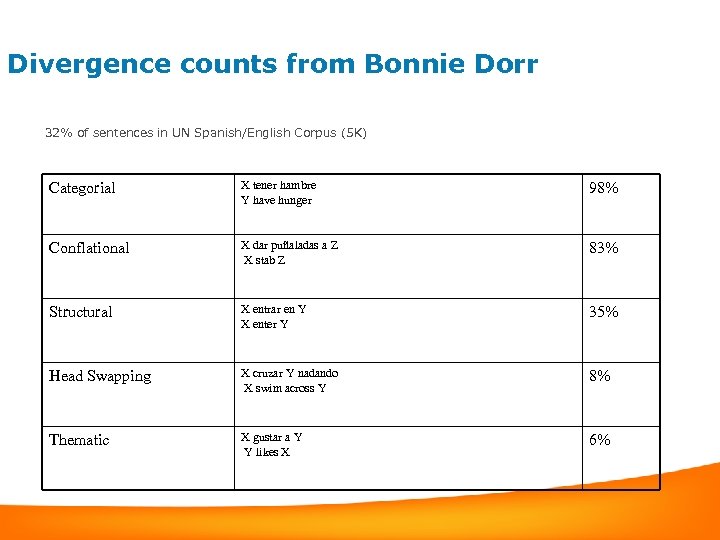

Divergence counts from Bonnie Dorr 32% of sentences in UN Spanish/English Corpus (5 K) Categorial X tener hambre Y have hunger 98% Conflational X dar puñaladas a Z X stab Z 83% Structural X entrar en Y X enter Y 35% Head Swapping X cruzar Y nadando X swim across Y 8% Thematic X gustar a Y Y likes X 6%

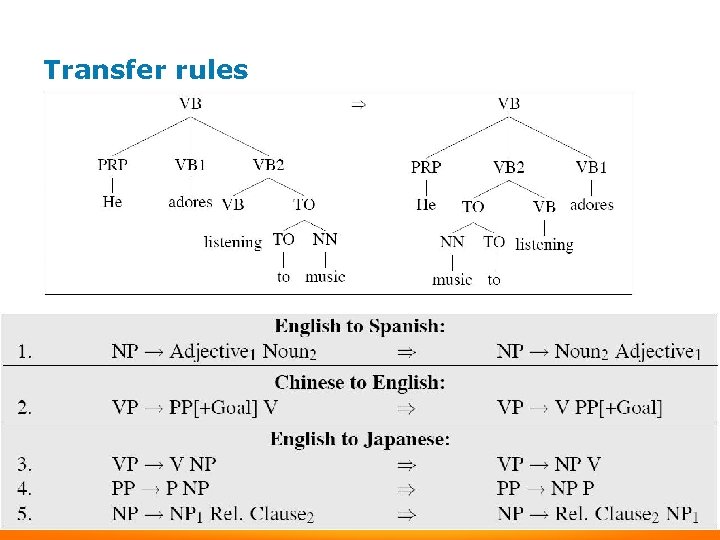

Transfer rules

Syntax-driven statistical machine translation Slides from Devi Xiong, CAS, Beijing

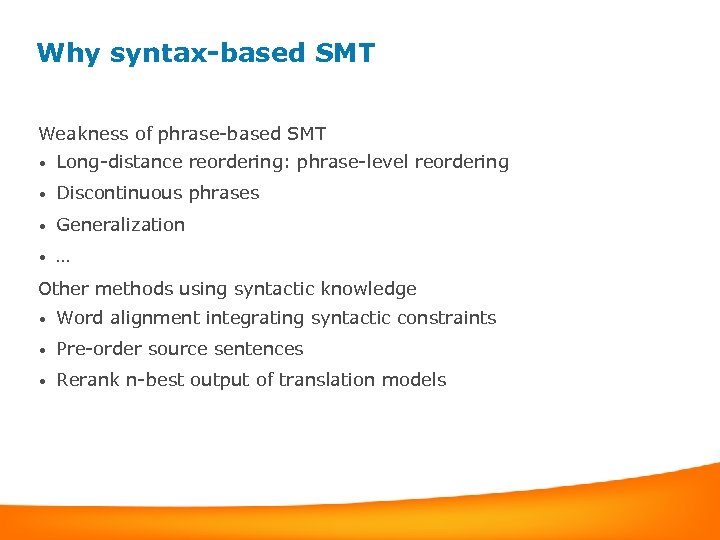

Why syntax-based SMT Weakness of phrase-based SMT • Long-distance reordering: phrase-level reordering • Discontinuous phrases • Generalization • … Other methods using syntactic knowledge • Word alignment integrating syntactic constraints • Pre-order source sentences • Rerank n-best output of translation models

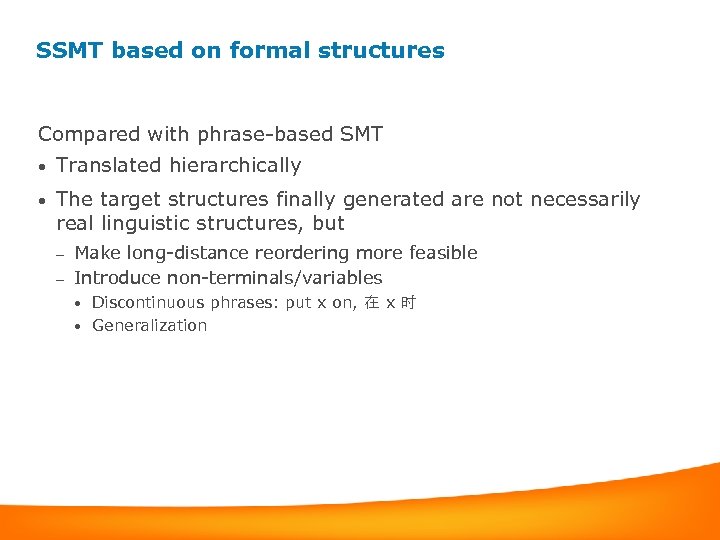

SSMT based on formal structures Compared with phrase-based SMT • Translated hierarchically • The target structures finally generated are not necessarily real linguistic structures, but Make long-distance reordering more feasible – Introduce non-terminals/variables – Discontinuous phrases: put x on, 在 x 时 • Generalization •

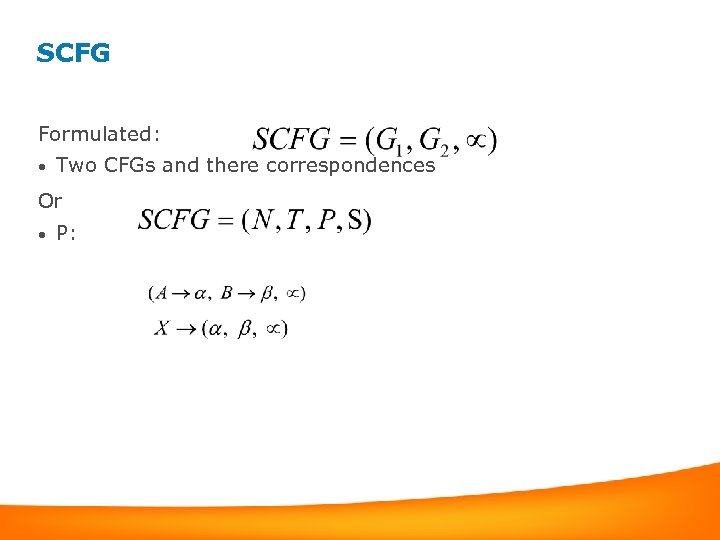

SCFG Formulated: • Two CFGs and there correspondences Or • P:

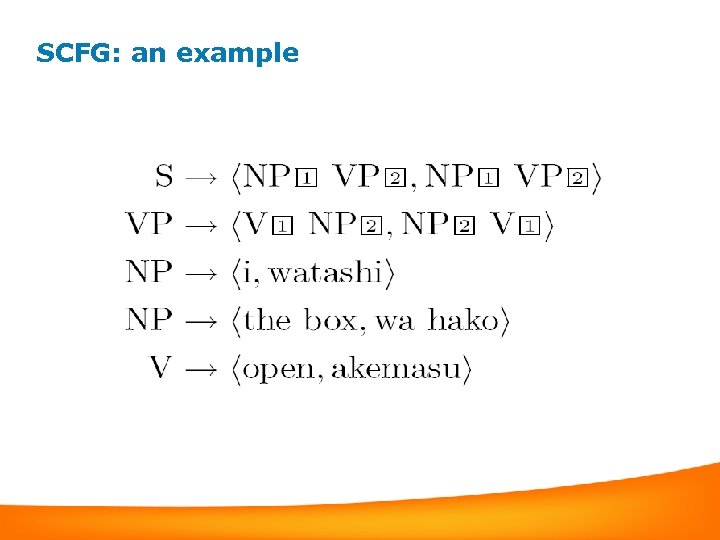

SCFG: an example

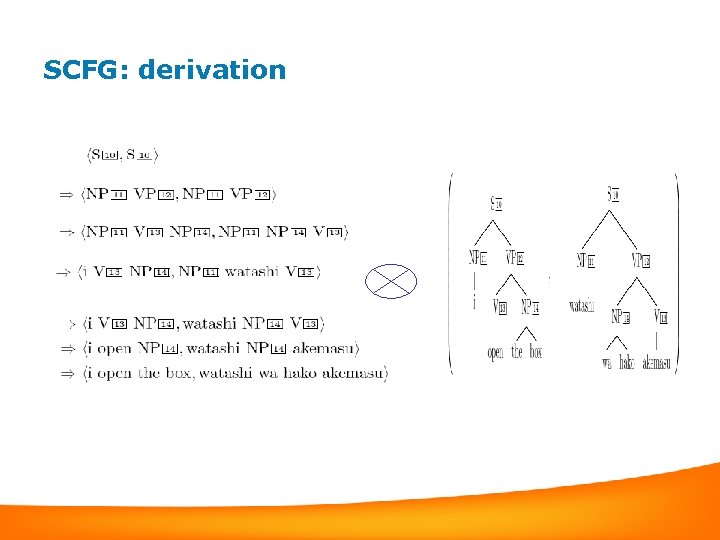

SCFG: derivation

ITG as reordering constraint Two kinds of reordering • Inverted • straight Coverage • Wu(1997): “been unable to find real examples” of cases where alignments would fail under this constraint, at least in “lightly inflected languages, such as English and Chinese. ” • Wellington(2006): “we found examples”, “at least 5% of the Chinese/English sentence pairs”. Weakness • No strong mechanism determining which order is better, inverted or straight.

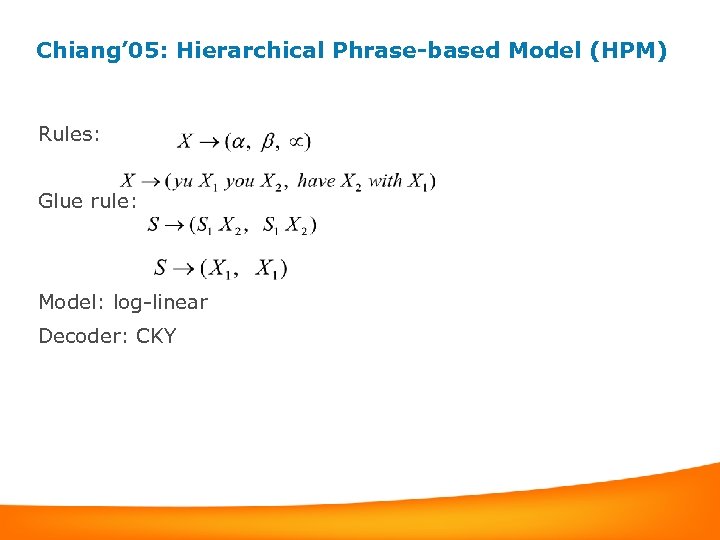

Chiang’ 05: Hierarchical Phrase-based Model (HPM) Rules: Glue rule: Model: log-linear Decoder: CKY

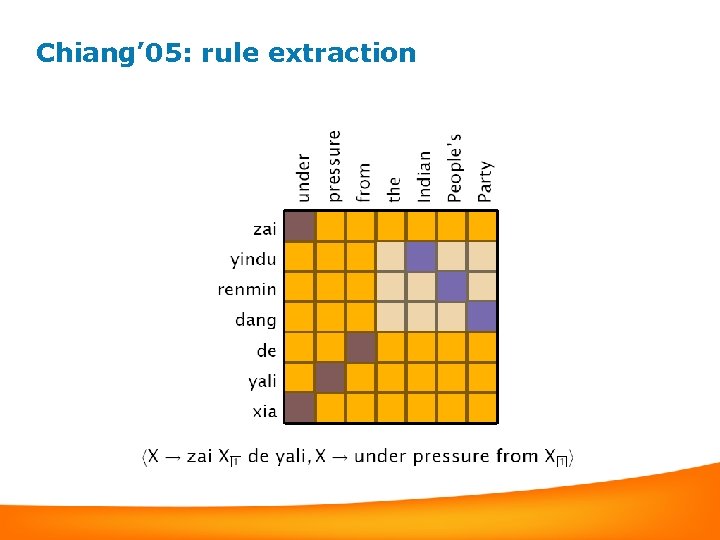

Chiang’ 05: rule extraction

Chiang’ 05: rule extraction restrictions Initial base rule at most 15 on French side Final rule at most 5 on French side At most two non-terminals on each side, nonadjacent At least one aligned terminal pair

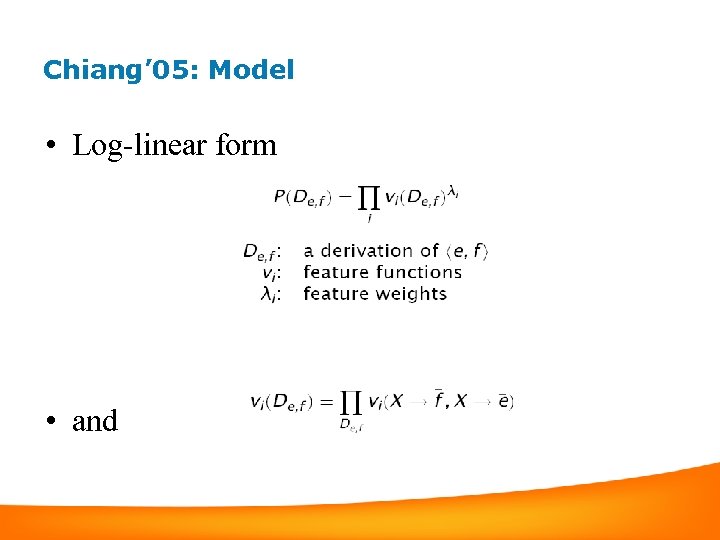

Chiang’ 05: Model • Log-linear form • and

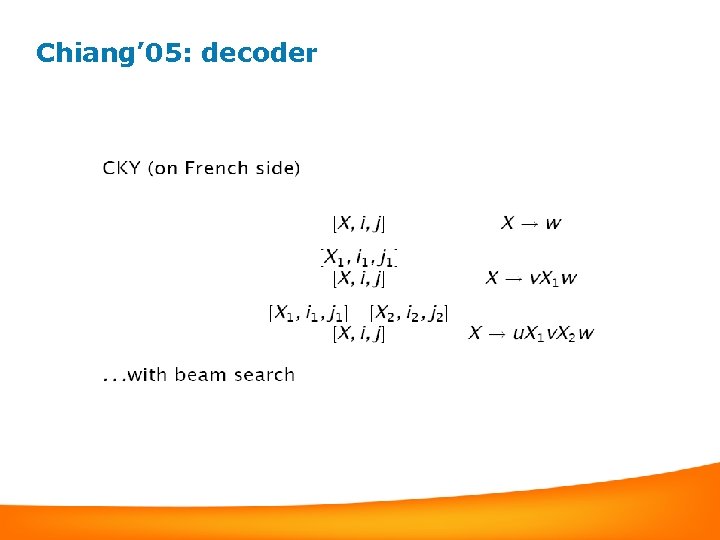

Chiang’ 05: decoder

SSMT based on phrase structures Using grammars with linguistic knowledge • The grammars are based on SCFG Two categories: • Tree-string Tree-to-string – String-to-tree – • Tree-tree

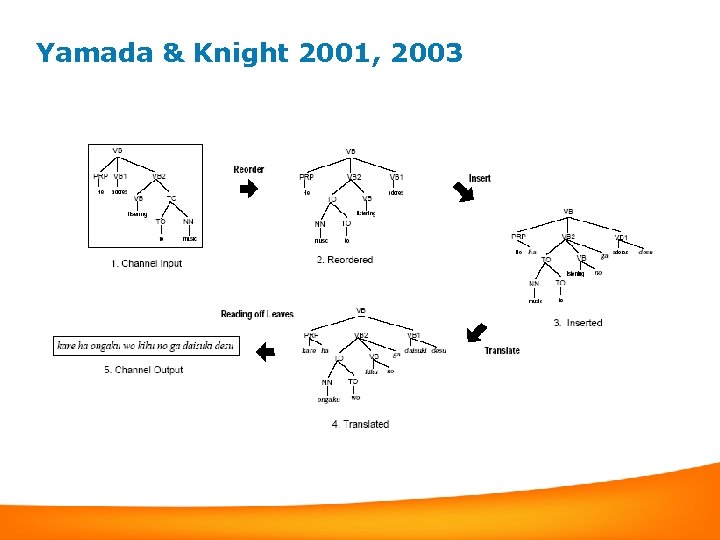

Yamada & Knight 2001, 2003

Yamada’s work vs. SCFG Insertion operation: • A (w. A 1, A 1) Reordering operation • A (A 1 A 2 A 3, A 1 A 3 A 2) Translating operation • A (x, y)

Yamada: weakness Single-level mapping • Multi-level reordering – Yamada: flatten Word-based • Yamada: phrasal leaf

Galley et al. 2004, 2006 translation model incorporates syntactic structure on the target language side • trained by learning “translation rules” from bilingual data the decoder uses a parser-like method to create syntactic trees as output hypotheses

Translation rules • Target: multi-level subtrees • Source: continuous or discontinuous phrases Types of translation rules • Translating source phrases into target chunks NPB(PRP/I) ↔我 – NP-C(NPB(DT/this NN/address)) ↔这个 地址 –

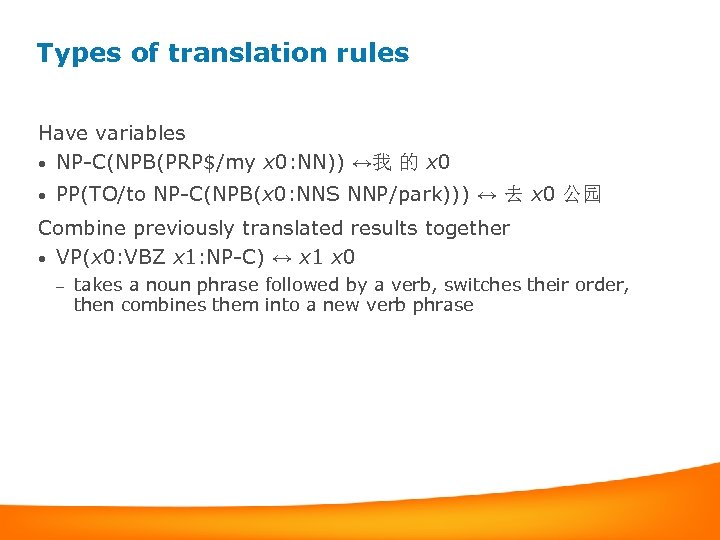

Types of translation rules Have variables • NP-C(NPB(PRP$/my x 0: NN)) ↔我 的 x 0 • PP(TO/to NP-C(NPB(x 0: NNS NNP/park))) ↔ 去 x 0 公园 Combine previously translated results together • VP(x 0: VBZ x 1: NP-C) ↔ x 1 x 0 – takes a noun phrase followed by a verb, switches their order, then combines them into a new verb phrase

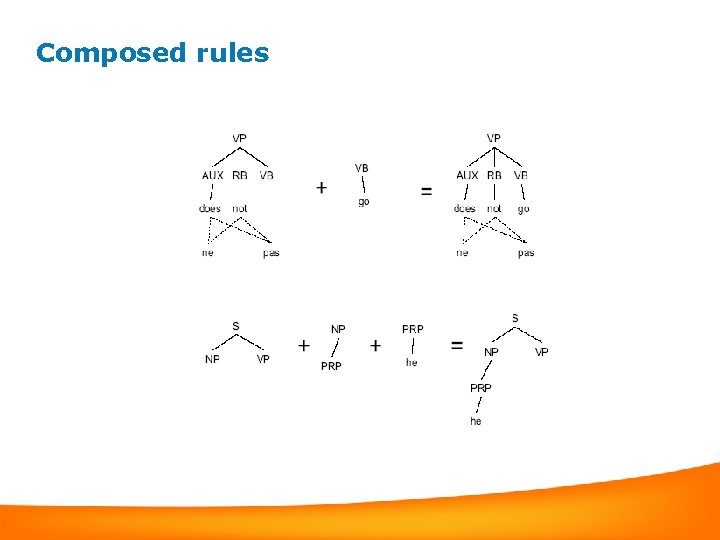

Rules extraction Word-align a parallel corpus Parse the target side Extract translation rules • Minimal rules: can not be decomposed • Composed rules: composed by minimal rules Estimate probalities

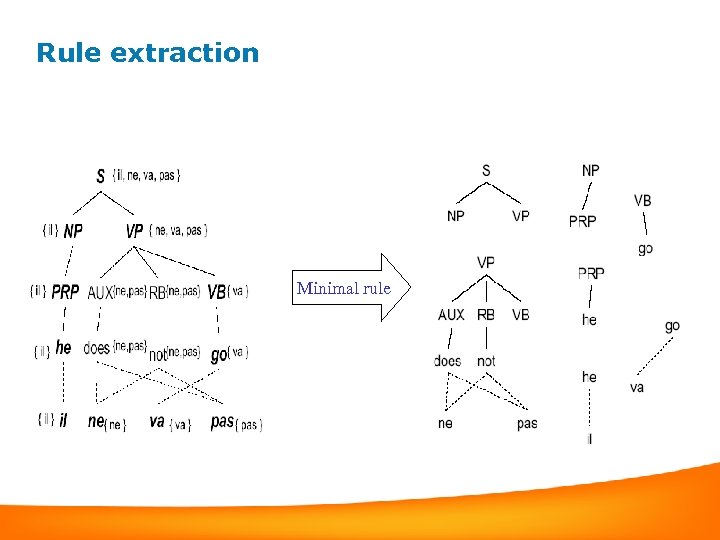

Rule extraction Minimal rule

Composed rules

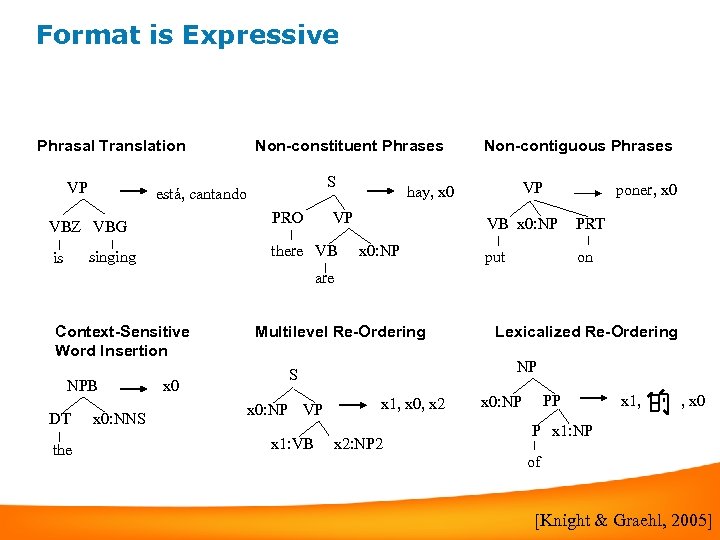

Format is Expressive Phrasal Translation VP S está, cantando PRO VBZ VBG Non-contiguous Phrases VP hay, x 0 VP there VB singing is Non-constituent Phrases poner, x 0 VB x 0: NP PRT put on are Context-Sensitive Word Insertion NPB DT the x 0: NNS x 0 Multilevel Re-Ordering NP S x 0: NP VP x 1: VB Lexicalized Re-Ordering x 1, x 0, x 2: NP 2 PP x 0: NP x 1, , x 0 P x 1: NP of [Knight & Graehl, 2005]

decoder probabilistic CYK-style parsing algorithm with beams results in an English syntax tree corresponding to the Chinese sentence guarantees the output to have some kind of globally coherent syntactic structure

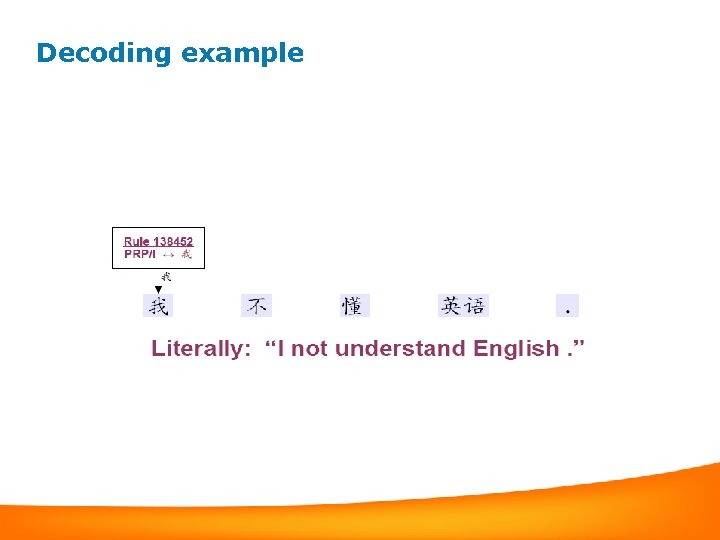

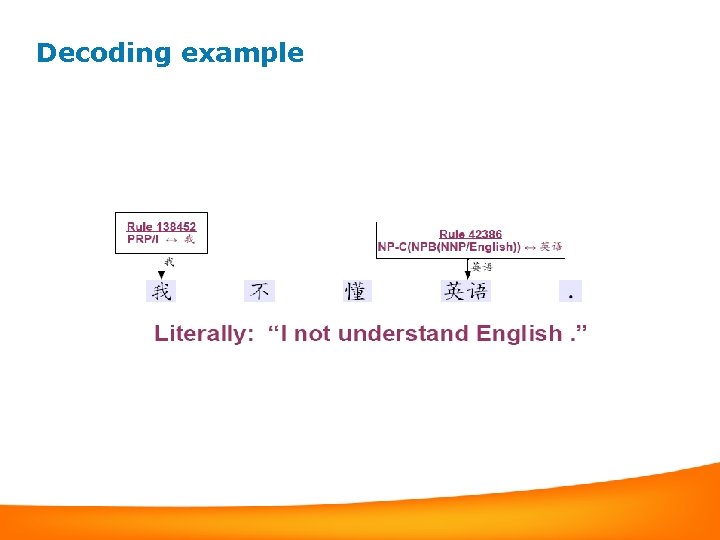

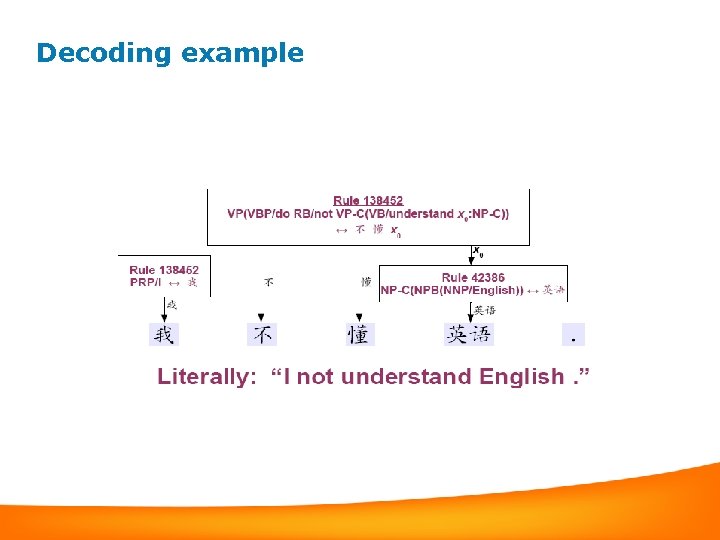

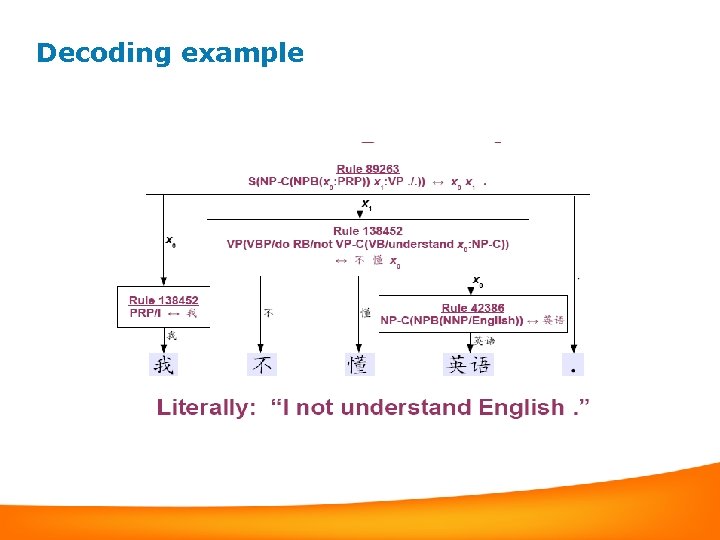

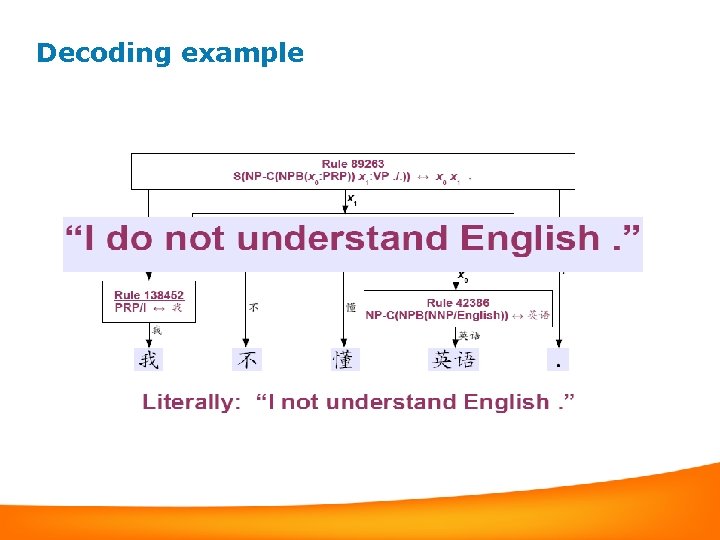

Decoding example

Decoding example

Decoding example

Decoding example

Decoding example

Marcu et al. 2006 SPMT • Integrating non-syntactifiable phrases • Multiple features for each rule • Decoding with multiple models

SSMT based on phrase structures Two categories: • Tree-string String-to-tree – Tree-to-string – • Tree-tree

Tree-to-string Liu et al. 2006 • Tree-to-string alignment template model

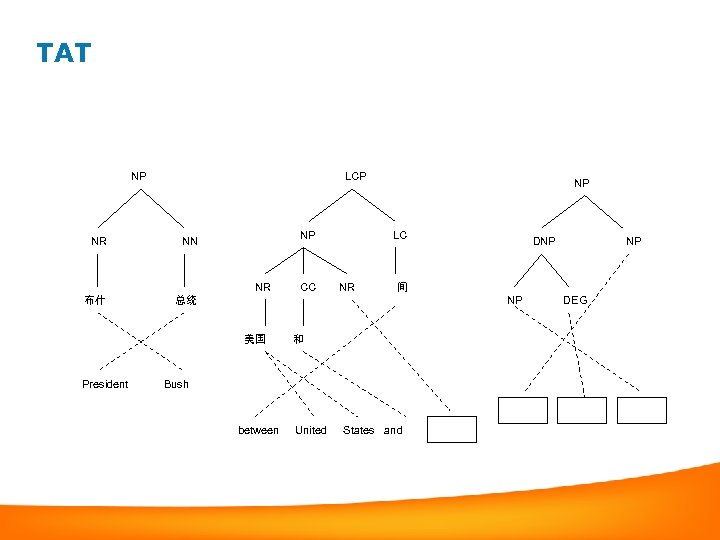

TAT NP NR LCP NP NN NR 布什 LC NR DNP NP 和 Bush between United NP 间 总统 美国 President CC NP States and DEG

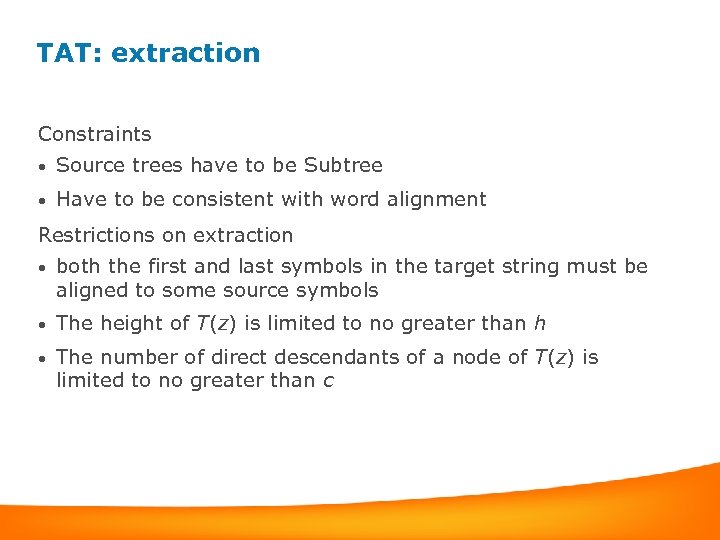

TAT: extraction Constraints • Source trees have to be Subtree • Have to be consistent with word alignment Restrictions on extraction • both the first and last symbols in the target string must be aligned to some source symbols • The height of T(z) is limited to no greater than h • The number of direct descendants of a node of T(z) is limited to no greater than c

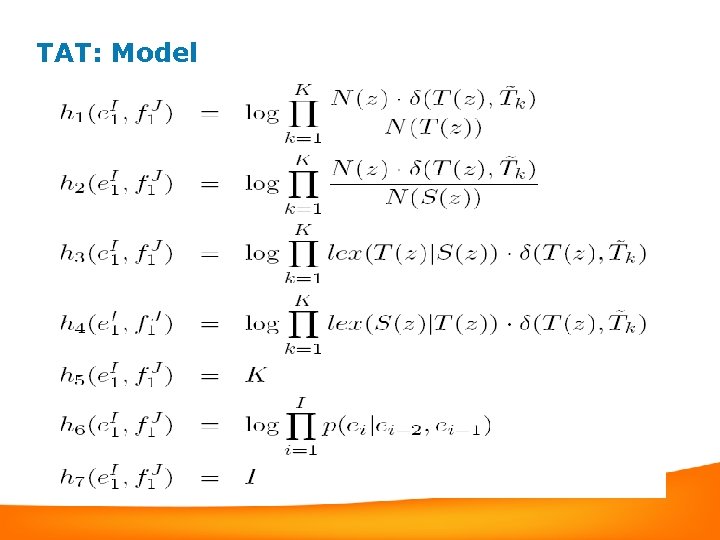

TAT: Model

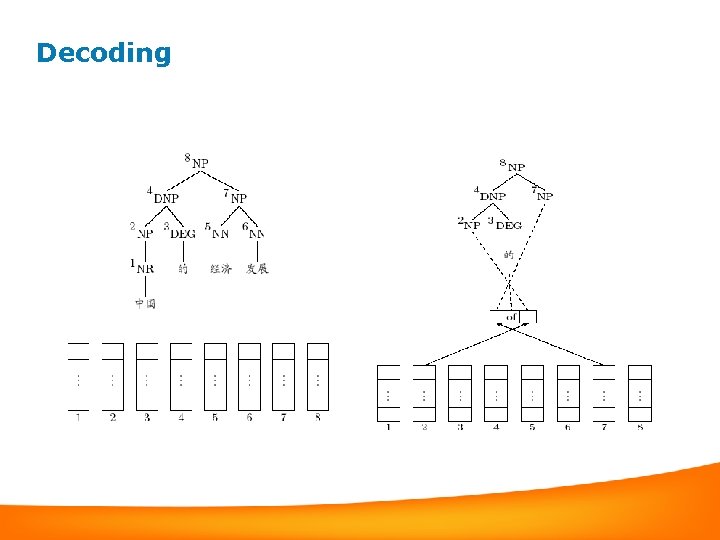

Decoding

Tree-to-string vs. string-to-tree Tree-to-string • Integrating source structures into translation and reordering • The output can not be grammatical string-to-tree • guarantees the output to have some kind of globally coherent syntactic structure • Can not use any knowledge from source structures

SSMT based on phrase structures Two categories: • Tree-string String-to-tree – Tree-to-string – • Tree-tree

Tree-Tree Synchronous tree-adjoining grammar (STAG) Synchronous tree substitution grammar (STSG)

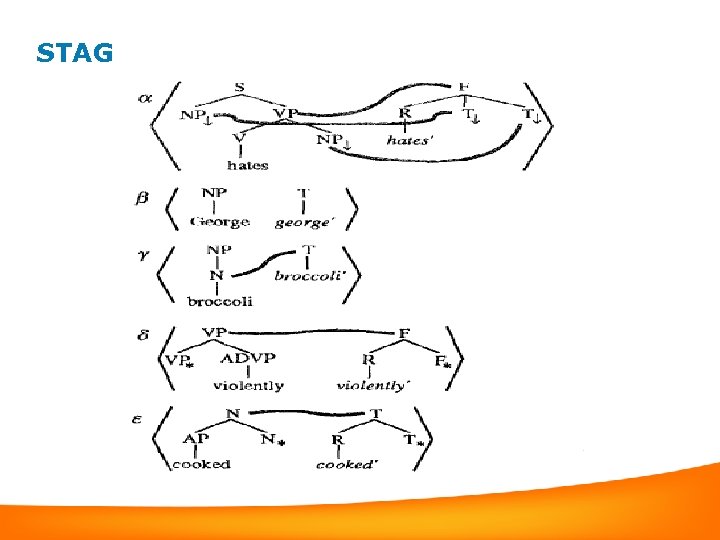

STAG

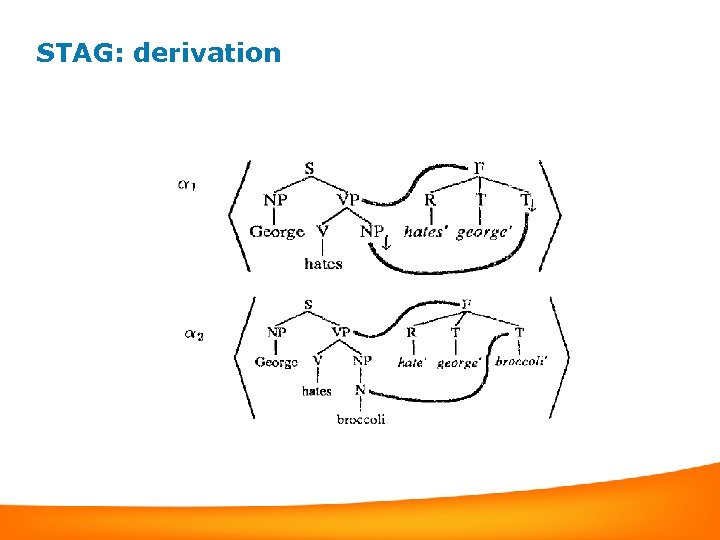

STAG: derivation

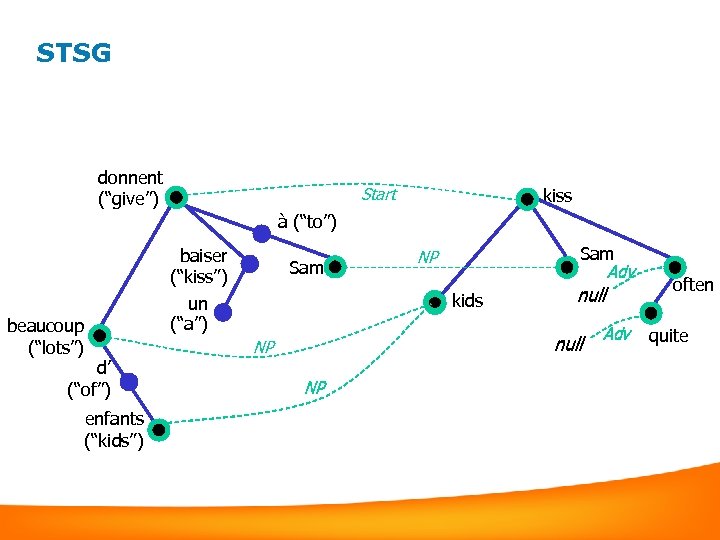

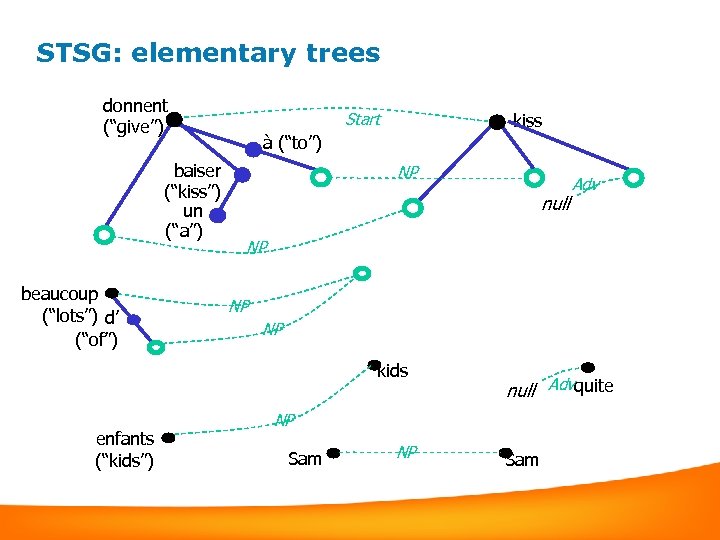

STSG donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) enfants (“kids”) Sam NP Adv kids null NP NP Adv often quite

STSG: elementary trees donnent (“give”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) Start kiss à (“to”) NP null NP NP NP kids enfants (“kids”) Adv null Advquite NP Sam

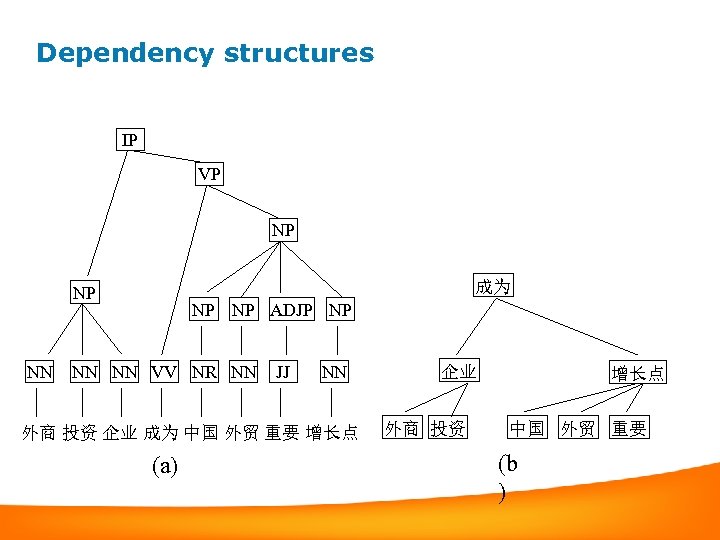

Dependency structures IP VP NP 成为 NP NN NP NP ADJP NP NN NN VV NR NN JJ NN 外商 投资 企业 成为 中国 外贸 重要 增长点 (a) 企业 外商 投资 增长点 中国 外贸 重要 (b )

For MT: dependency structures vs. phrase structures Advantages of dependency structures over phrase structures for machine translation • Inherent lexicalization • Meaning-relative • Better representation of divergences across languages

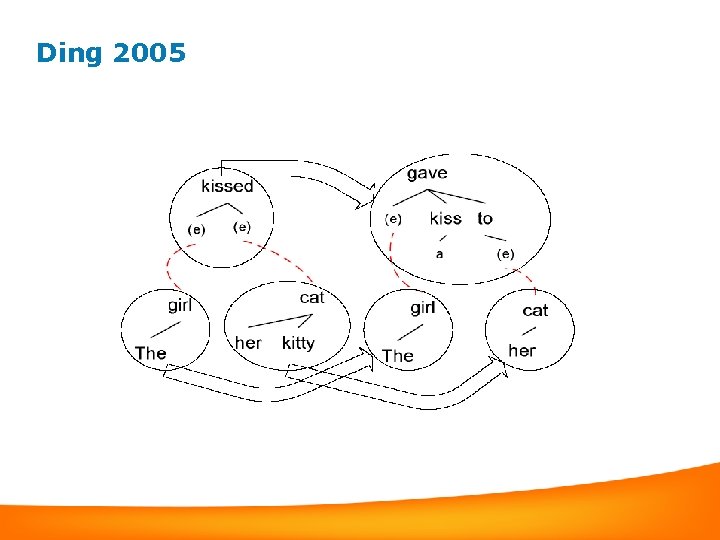

SSMT based on dependency structures Lin 2004 • A Path-based Transfer Model for Machine Translation Quirk et al. 2005 • Dependency Treelet Translation: Syntactically Informed Phrasal SMT Ding et al. 2005 • Machine Translation Using Probabilistic Synchronous Dependency Insertion Grammars

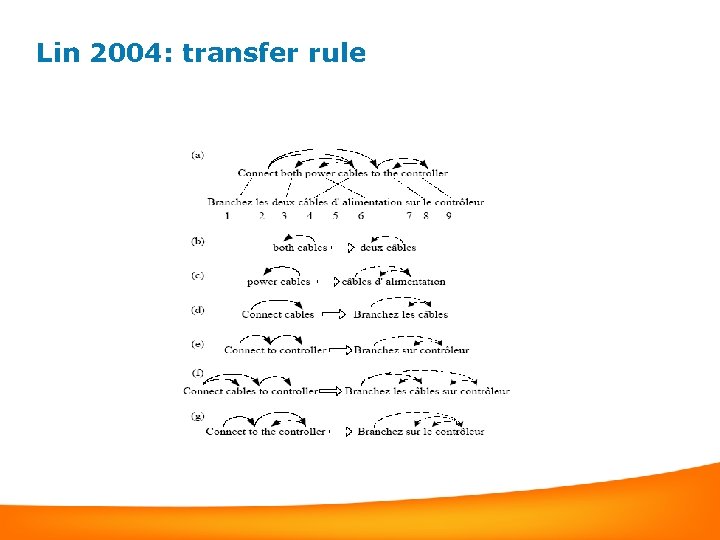

Lin 2004 Translation model trained by learning transfer rules from bilingual corpus where the source language sentences are parsed. decoding: finding the minimum path covering of the source language dependency tree

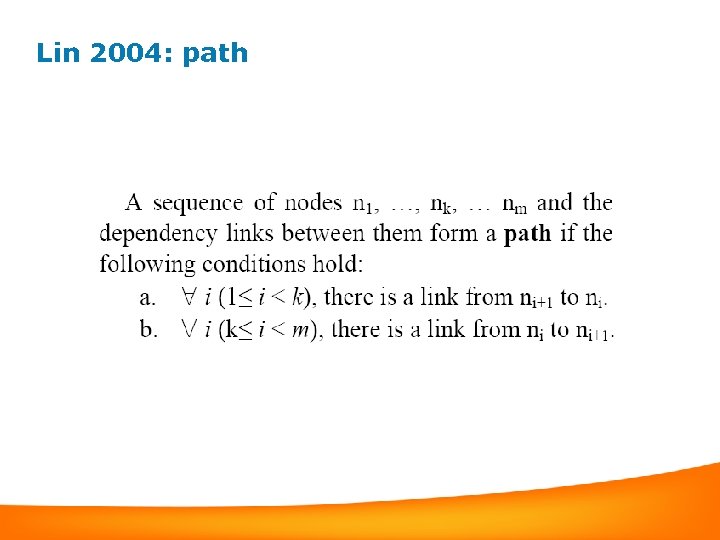

Lin 2004: path

Lin 2004: transfer rule

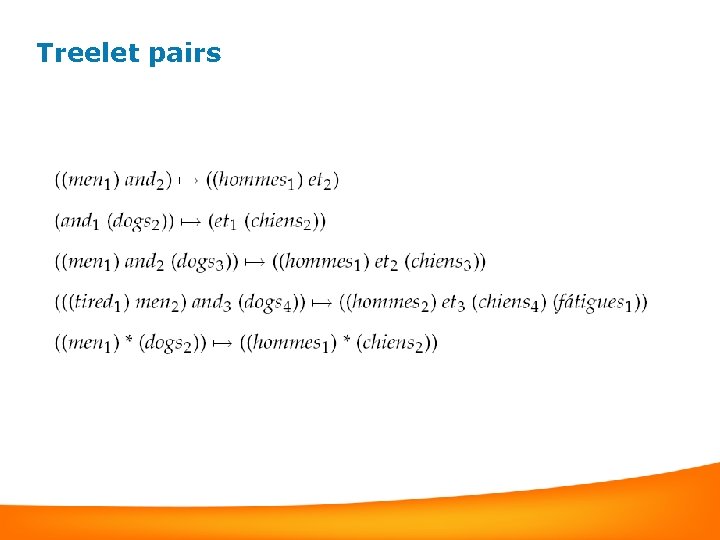

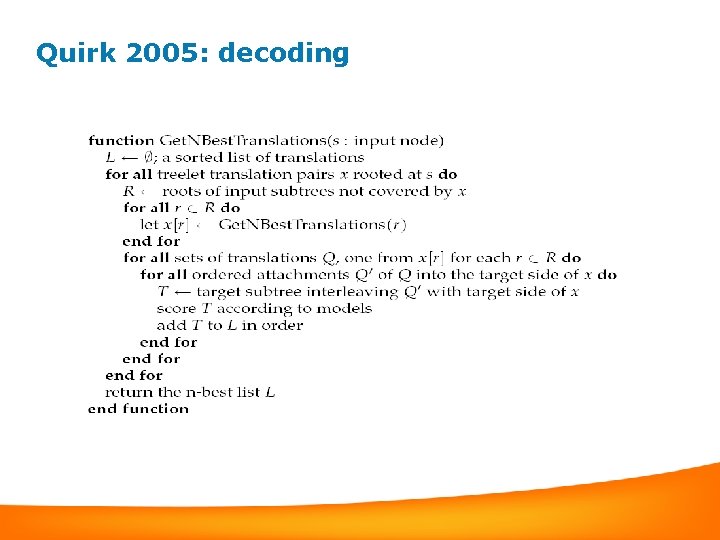

Quirk et al. 2005 Translation model trained by learning treelet pairs from bilingual corpus where the source language sentences are parsed. Decoding: CKY-style

Treelet pairs

Quirk 2005: decoding

Ding 2005

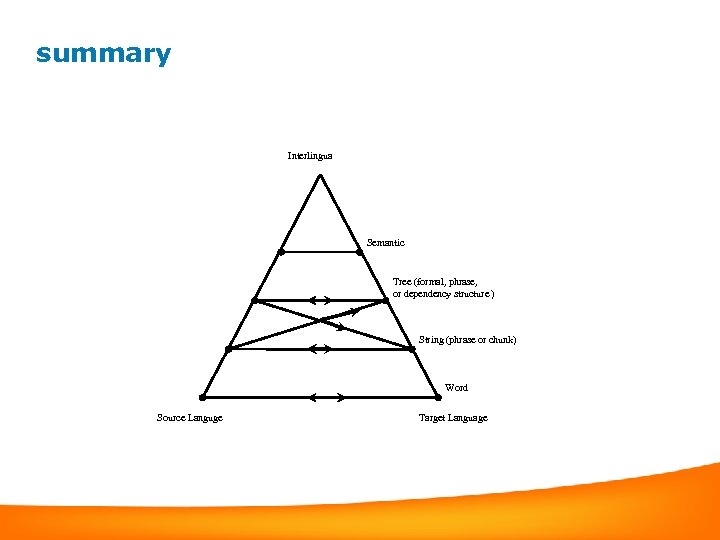

summary Interlingua Semantic Tree (formal, phrase, or dependency structure ) String (phrase or chunk) Word Source Languge Target Language

Introduction State of the art machine translation systems based on statistical models rooted in theory of formal grammars/automata Translation models based on finite state devices cannot easily model translations between languages with strong differences in word ordering Recently, several models based on context-free grammars have been investigated, borrowing from theory of compilers the idea of synchronous rewriting Slides from G. Satta

Introduction Translation models based on synchronous rewriting: Inversion Transduction Grammars (Wu, 1997) Head Transducer Grammars (Alshawi et al. , 2000) Tree-to-string models (Yamada & Knight, 2001; Galley et al, 2004) “Loosely tree-based” model (Gildea, 2003) Multi-Text Grammars (Melamed, 2003) Hierarchical phrase-based model (Chiang, 2005) We use synchronous CFGs to study formal properties of all these

Synchronous CFG A synchronous context-free grammar (SCFG) is based on three components: Context free grammar (CFG) for source language CFG for target language Pairing relation on the productions of the two grammars and on the nonterminals in their right-hand sides

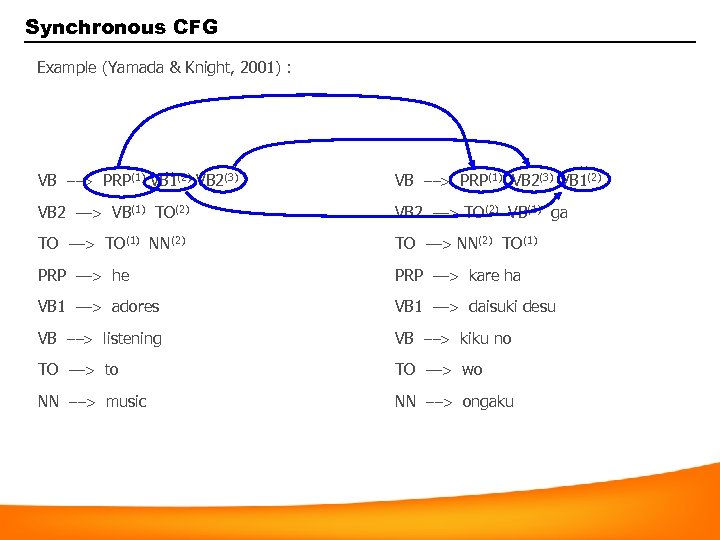

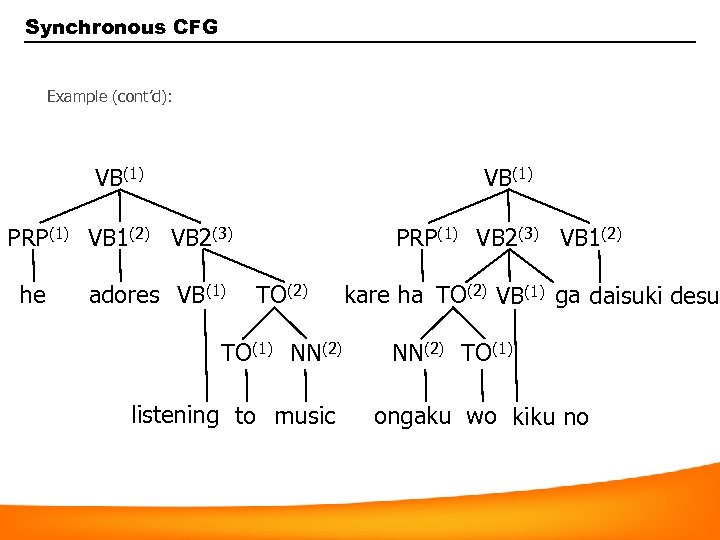

Synchronous CFG Example (Yamada & Knight, 2001) : VB --> PRP(1) VB 1(2) VB 2(3) VB --> PRP(1) VB 2(3) VB 1(2) VB 2 --> VB(1) TO(2) VB 2 --> TO(2) VB(1) ga TO --> TO(1) NN(2) TO --> NN(2) TO(1) PRP --> he PRP --> kare ha VB 1 --> adores VB 1 --> daisuki desu VB --> listening VB --> kiku no TO --> to TO --> wo NN --> music NN --> ongaku

Synchronous CFG Example (cont’d): VB(1) PRP(1) VB 1(2) VB 2(3) PRP(1) VB 2(3) VB 1(2) he adores VB(1) TO(2) TO(1) NN(2) listening to music kare ha TO(2) VB(1) ga daisuki desu NN(2) TO(1) ongaku wo kiku no

Synchronous CFG A pair of CFG productions in a SCFG is called a synchronous production A SCFG generates pairs of trees/strings, where each component is a translation of the other A SCFG can be extended with probabilities: Each pair of productions is assigned a probability Probability of a pair of trees is the product of probabilities of synchronous productions involved

Membership The membership problem (Wu, 1997) for SCFGs is defined as follows: Input: SCFG and pair of strings [w 1, w 2 ] Output: Yes/No depending on whether w 1 translates into w 2 under the SCFG Applications in segmentation, word alignment and bracketing of parallel corpora Assumption that SCFG is part of the input is made here to investigate the dependency of problem complexity on grammar size

Membership Result: Membership problem for SCFGs is NP-complete Proof uses SCFG derivations to explore space of consistent truth assignments that satisfy source 3 SAT instance Remarks: Result transfers to (Yamada & Knight, 2001), (Gildea, 2003), (Melamed, 2003), which are at least as powerful as SCFG

Membership Remarks (cont’d): Problem can be solved in polynomial time if: • input grammar is fixed or production length is bounded (Melamed, 2004) • Inversion Transduction Grammars (Wu, 1997) • Head Transducer Grammars (Alshawi et al. , 2000) For NLP applications, it is more realistic to assume a fixed grammar and varying input string

Chart parsing Providing an exponential time lower bound for the membership problem would amount to showing P ≠ NP But we can show such a lower bound if we make some assumptions on the class of algorithms and data structures that we use to solve the problem Result: If chart parsing techniques are used to solve the membership problem for SCFG, a number of partial analyses is obtained that grows exponentially with the production length of the input grammar

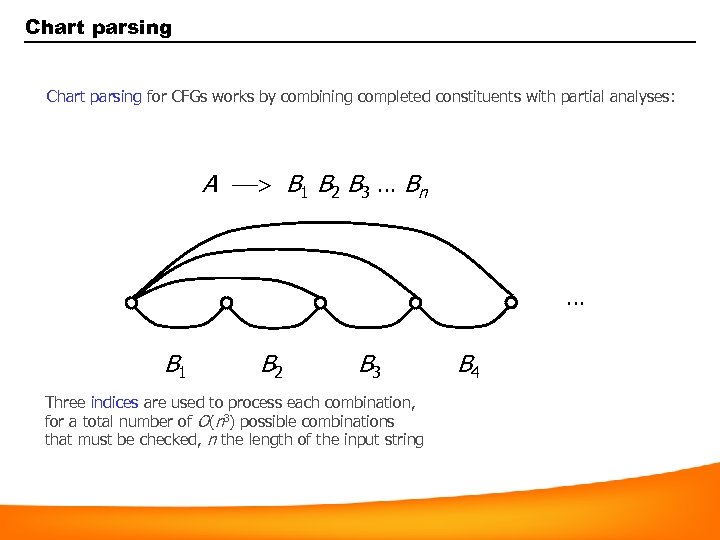

Chart parsing for CFGs works by combining completed constituents with partial analyses: A --> B 1 B 2 B 3 … Bn … B 1 B 2 B 3 Three indices are used to process each combination, for a total number of O(n 3) possible combinations that must be checked, n the length of the input string B 4

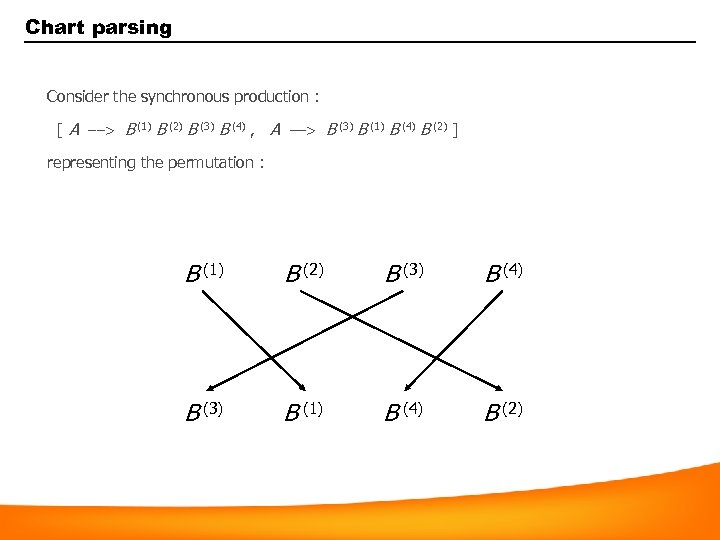

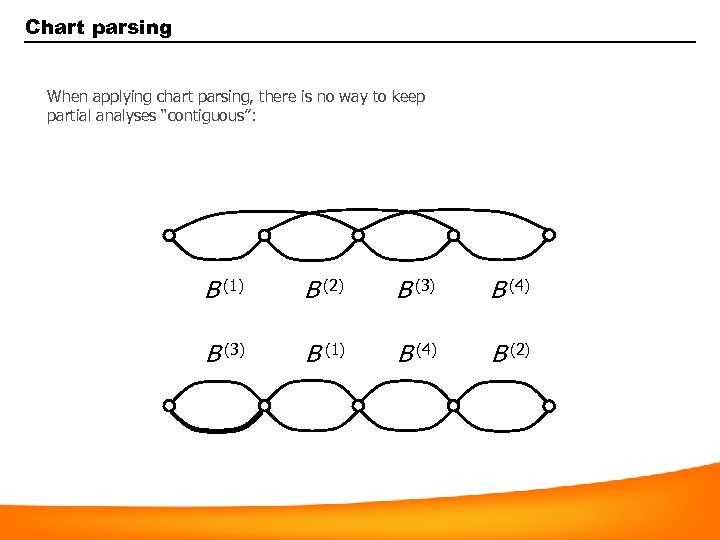

Chart parsing Consider the synchronous production : [ A --> B (1) B (2) B (3) B (4) , A --> B (3) B (1) B (4) B (2) ] representing the permutation : B (1) B (2) B (3) B (4) B (3) B (1) B (4) B (2)

Chart parsing When applying chart parsing, there is no way to keep partial analyses “contiguous”: B (1) B (2) B (3) B (4) B (3) B (1) B (4) B (2)

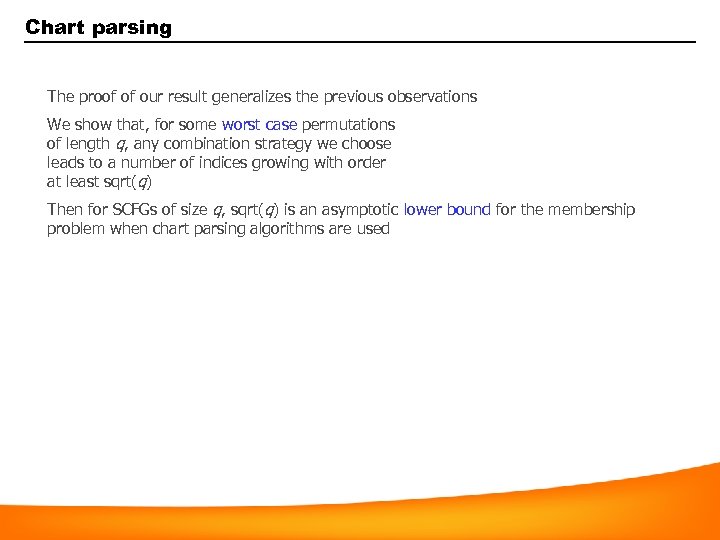

Chart parsing The proof of our result generalizes the previous observations We show that, for some worst case permutations of length q, any combination strategy we choose leads to a number of indices growing with order at least sqrt(q) Then for SCFGs of size q, sqrt(q) is an asymptotic lower bound for the membership problem when chart parsing algorithms are used

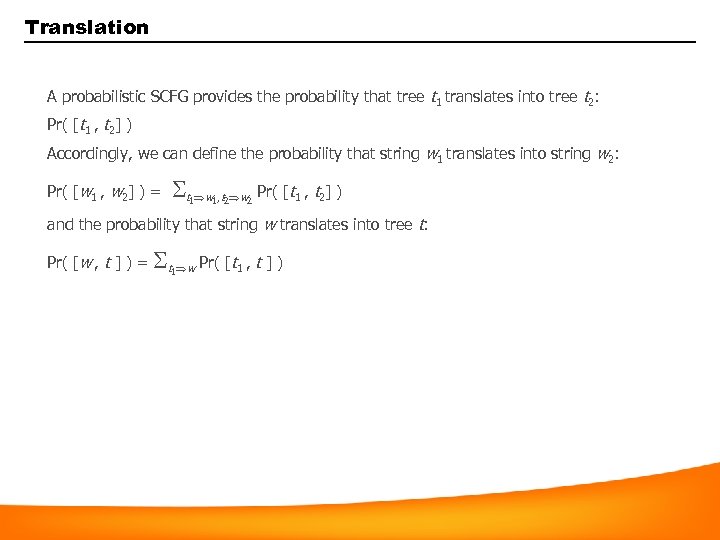

Translation A probabilistic SCFG provides the probability that tree t 1 translates into tree t 2: Pr( [t 1 , t 2] ) Accordingly, we can define the probability that string w 1 translates into string w 2: Pr( [w 1 , w 2] ) = t w , t w 1 1 2 2 Pr( [t 1 , t 2] ) and the probability that string w translates into tree t: Pr( [w , t ] ) = t w Pr( [t 1 , t ] ) 1

Translation The string-to-tree translation problem for probabilistic SCFGs is defined as follows: Input: Probabilistic SCFG and string w Output: tree t such that Pr([w, t ]) is maximized Application in machine translation Again, assumption that SCFG is part of the input is made to investigate the dependency of problem complexity on grammar size

Translation Result: string-to-tree translation problem for probabilistic SCFGs (summing over possible source trees) is NP-hard Proof reduces from consensus problem: Strings generated by probabilistic finite automaton or hidden Markov model have probabilities defined as sum of probabilities of several paths Maximizing such summation is NP-hard (Casacuberta & Higuera, 2000) (Lyngso & Pedersen, 2002)

Translation Remarks: Source of complexity of the problem comes from the fact that several source trees can be translated into the same target tree Result persists if there is a constant bound on length of synchronous productions Open: can the problem be solved in polynomial time if probabilistic SCFG is fixed?

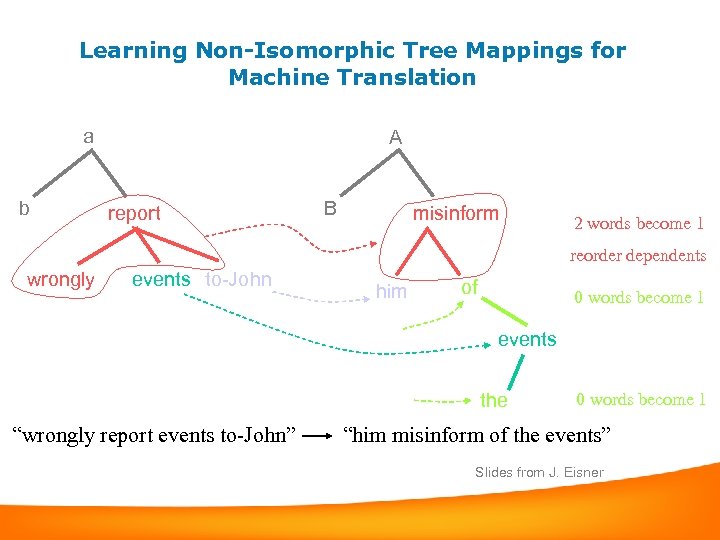

Learning Non-Isomorphic Tree Mappings for Machine Translation a b A report B misinform 2 words become 1 reorder dependents wrongly events to-John him of 0 words become 1 events the “wrongly report events to-John” 0 words become 1 “him misinform of the events” Slides from J. Eisner

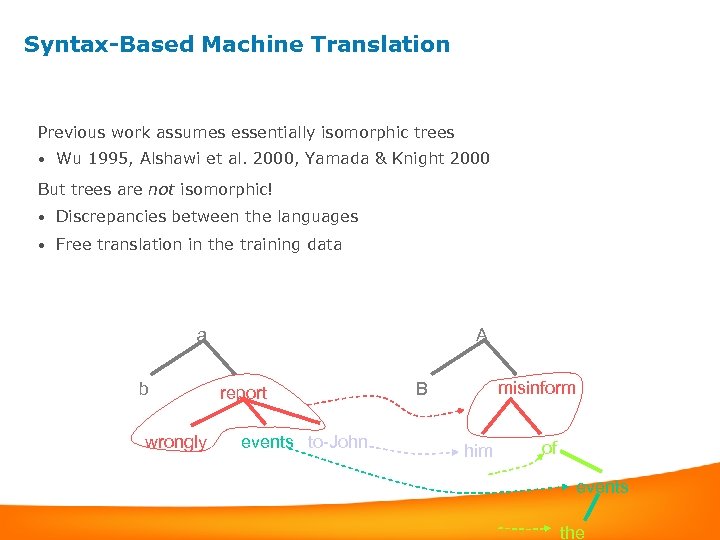

Syntax-Based Machine Translation Previous work assumes essentially isomorphic trees • Wu 1995, Alshawi et al. 2000, Yamada & Knight 2000 But trees are not isomorphic! • Discrepancies between the languages • Free translation in the training data a b wrongly A report events to-John misinform B him of events the

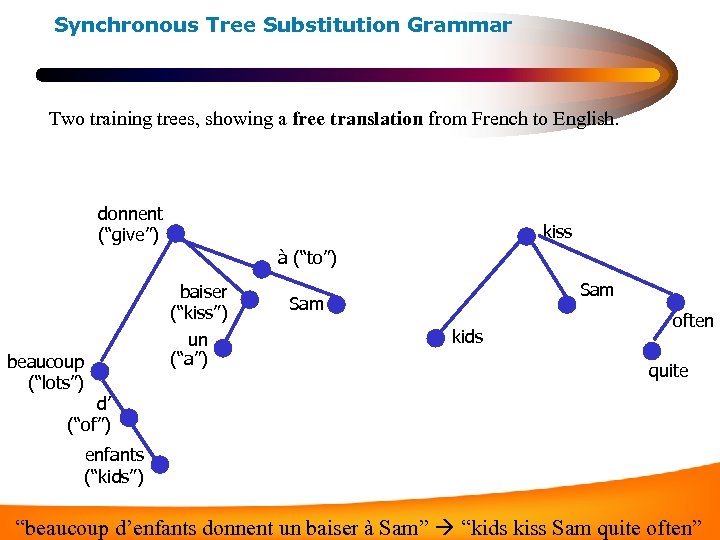

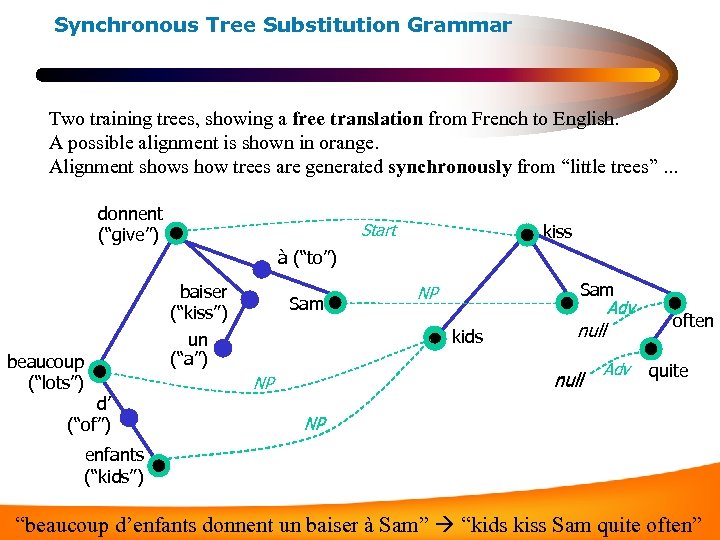

Synchronous Tree Substitution Grammar Two training trees, showing a free translation from French to English. donnent (“give”) kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) Sam kids often quite d’ (“of”) enfants (“kids”) “beaucoup d’enfants donnent un baiser à Sam” “kids kiss Sam quite often”

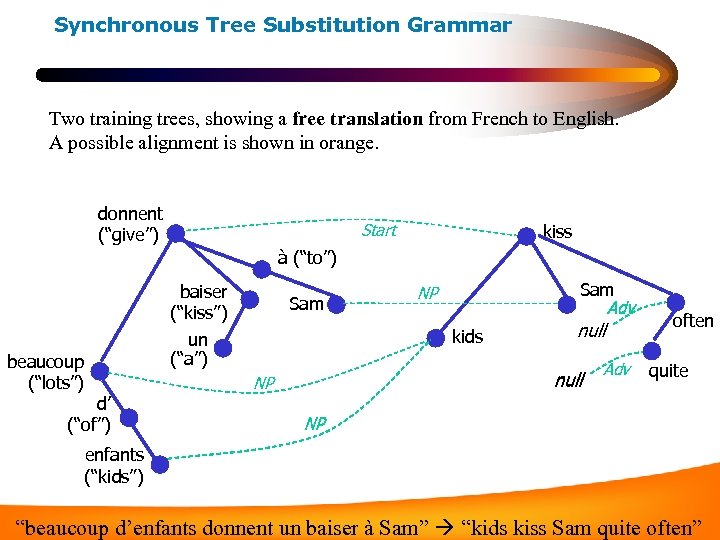

Synchronous Tree Substitution Grammar Two training trees, showing a free translation from French to English. A possible alignment is shown in orange. donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) Sam NP Adv kids null NP Adv often quite NP enfants (“kids”) “beaucoup d’enfants donnent un baiser à Sam” “kids kiss Sam quite often”

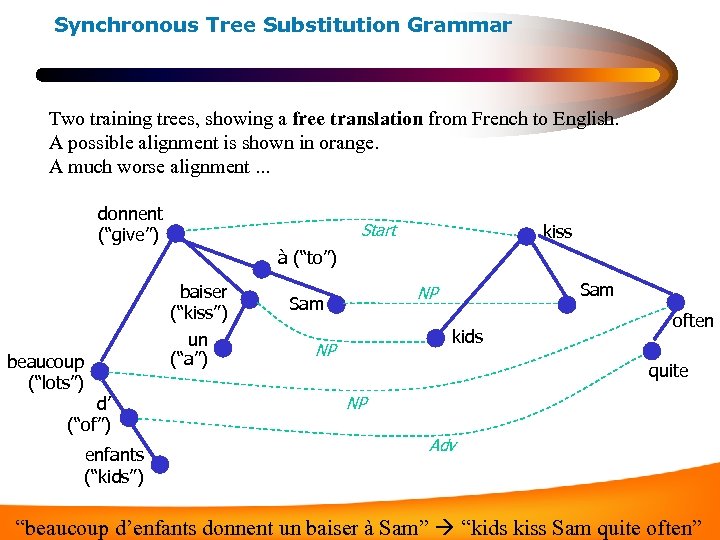

Synchronous Tree Substitution Grammar Two training trees, showing a free translation from French to English. A possible alignment is shown in orange. A much worse alignment. . . donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) enfants (“kids”) Sam NP Sam kids NP often quite NP Adv “beaucoup d’enfants donnent un baiser à Sam” “kids kiss Sam quite often”

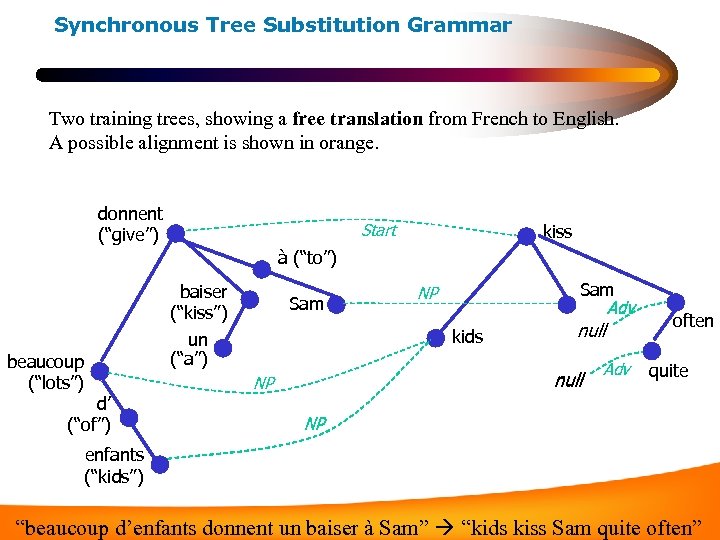

Synchronous Tree Substitution Grammar Two training trees, showing a free translation from French to English. A possible alignment is shown in orange. donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) Sam NP Adv kids null NP Adv often quite NP enfants (“kids”) “beaucoup d’enfants donnent un baiser à Sam” “kids kiss Sam quite often”

Synchronous Tree Substitution Grammar Two training trees, showing a free translation from French to English. A possible alignment is shown in orange. Alignment shows how trees are generated synchronously from “little trees”. . . donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) Sam NP Adv kids null NP Adv often quite NP enfants (“kids”) “beaucoup d’enfants donnent un baiser à Sam” “kids kiss Sam quite often”

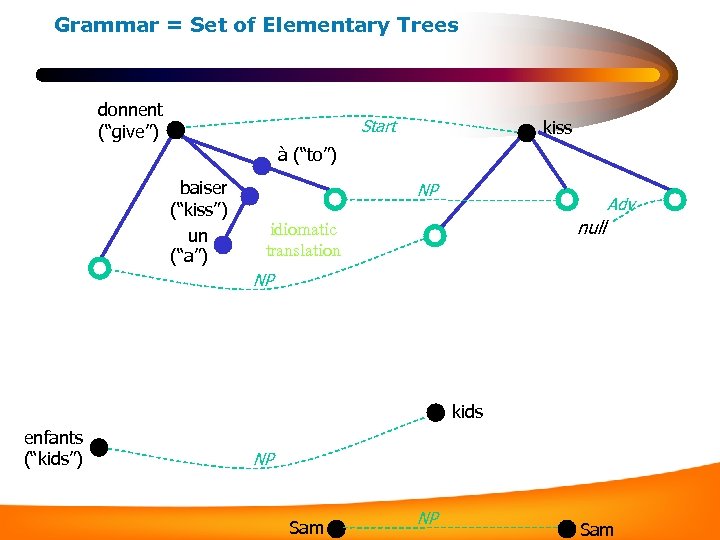

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) NP Adv null idiomatic translation NP kids enfants (“kids”) NP Sam

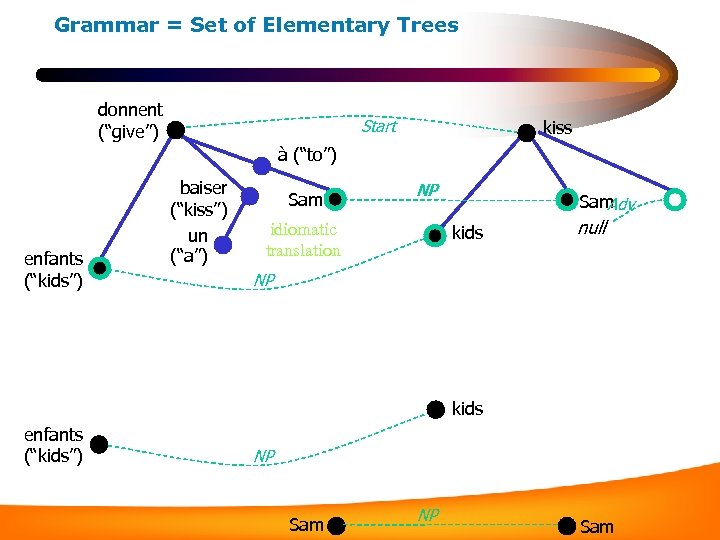

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) enfants (“kids”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) Sam NP idiomatic translation Sam Adv kids null NP kids enfants (“kids”) NP Sam

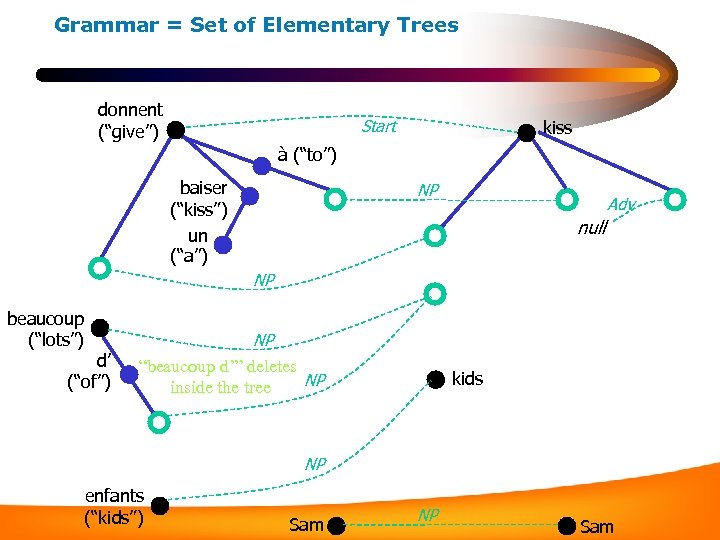

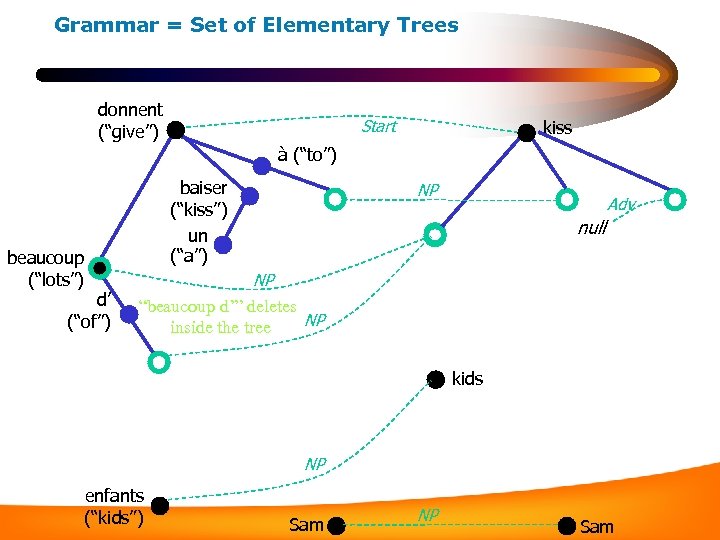

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) NP Adv null NP beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) NP “beaucoup d’” deletes NP inside the tree kids NP enfants (“kids”) Sam NP Sam

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) NP Adv null NP “beaucoup d’” deletes NP inside the tree kids NP enfants (“kids”) Sam NP Sam

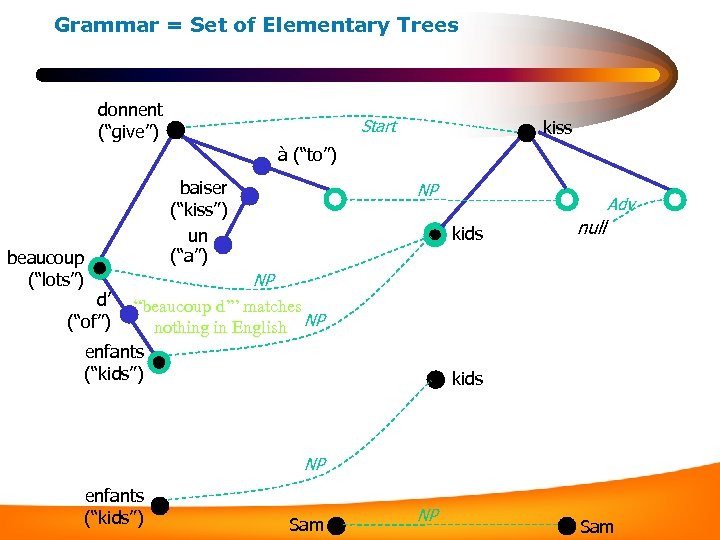

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) NP Adv kids null NP “beaucoup d’” matches nothing in English NP enfants (“kids”) kids NP enfants (“kids”) Sam NP Sam

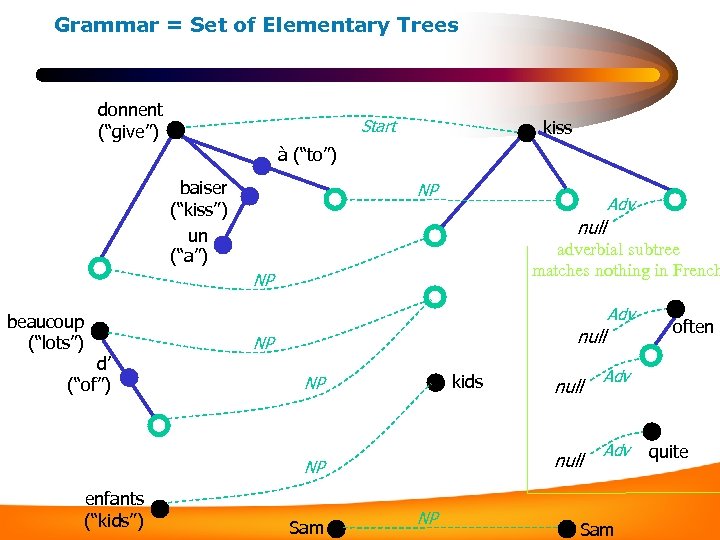

Grammar = Set of Elementary Trees donnent (“give”) Start kiss à (“to”) baiser (“kiss”) un (“a”) NP Adv null adverbial subtree matches nothing in French NP Adv beaucoup (“lots”) d’ (“of”) null NP kids NP null NP enfants (“kids”) Sam null NP often Adv Sam quite

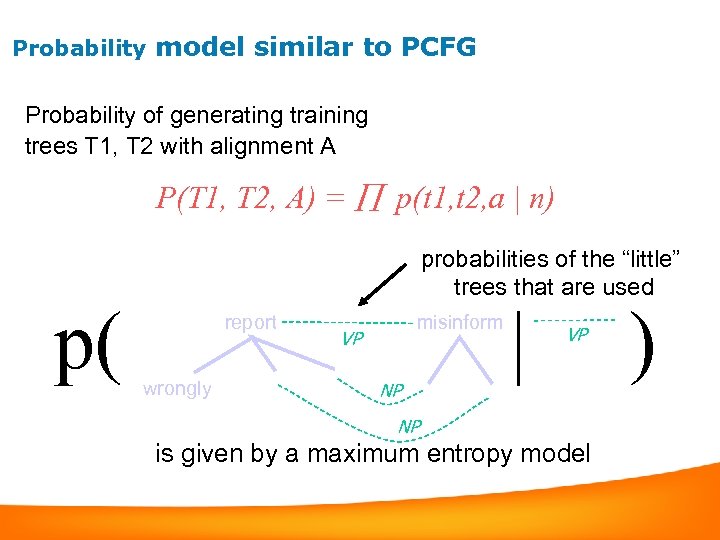

Probability model similar to PCFG Probability of generating training trees T 1, T 2 with alignment A P(T 1, T 2, A) = p(t 1, t 2, a | n) p( probabilities of the “little” trees that are used report wrongly misinform VP NP | VP NP is given by a maximum entropy model )

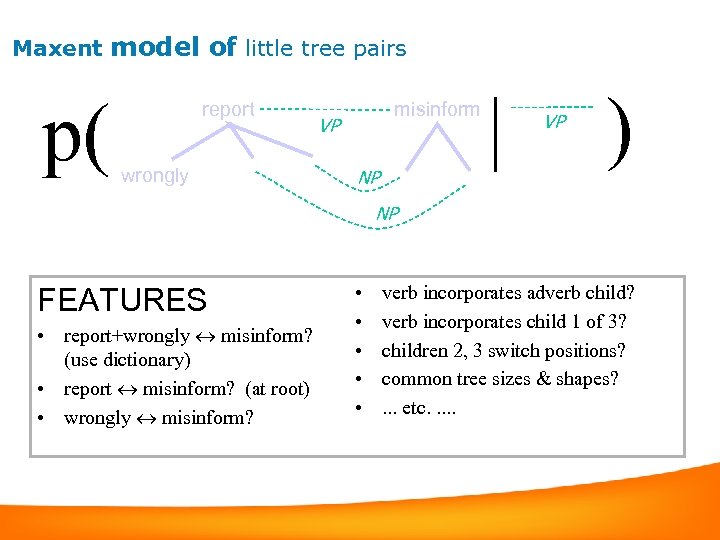

Maxent model of little tree pairs p( report wrongly misinform VP NP | VP ) NP FEATURES • report+wrongly misinform? (use dictionary) • report misinform? (at root) • wrongly misinform? • • • verb incorporates adverb child? verb incorporates child 1 of 3? children 2, 3 switch positions? common tree sizes & shapes? . . . etc. . .

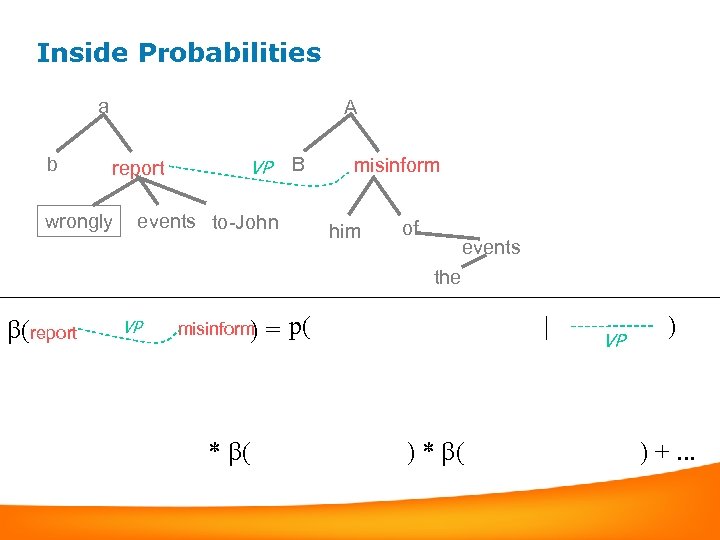

Inside Probabilities a b A report wrongly VP B events to-John misinform him of events the ( report VP misinform ) * ( p( =. . . | ) * ( VP ) ) +. . .

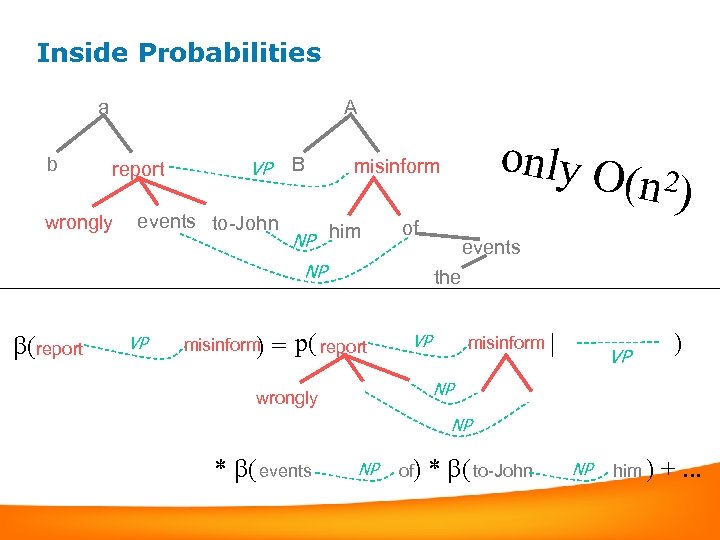

Inside Probabilities a b A report wrongly B VP events to-John NP him VP misinform ) (n 2) of events NP ( report only O misinform the p( =. . . report misinform | VP VP ) NP wrongly NP * ( events NP of) * ( to-John NP him ) +. . .

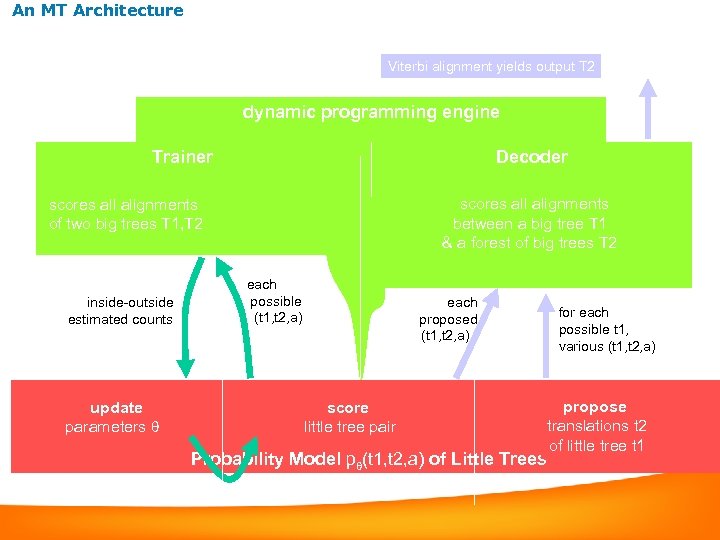

An MT Architecture Viterbi alignment yields output T 2 dynamic programming engine Trainer Decoder scores all alignments between a big tree T 1 & a forest of big trees T 2 scores all alignments of two big trees T 1, T 2 inside-outside estimated counts update parameters each possible (t 1, t 2, a) each proposed (t 1, t 2, a) score little tree pair Probability Model p (t 1, t 2, a) of Little Trees for each possible t 1, various (t 1, t 2, a) propose translations t 2 of little tree t 1

2cd8eddb80ba7dc0713bce6ff2061765.ppt