dfb7cbe1a228a2886804137a055df634.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 56

TRADING WITH THE WORLD 17 CHAPTER

Objectives After studying this chapter, you will able to § Describe the trends and patterns in international trade § Explain comparative advantage and explain why all countries can gain from international trade § Explain why international trade restrictions reduce the volume of imports and exports and reduce our consumption possibilities § Explain the arguments that are used to justify international trade restrictions and show they are flawed § Explain why we have international trade restrictions

Silk Routes and Sucking Sounds Since ancient times, people have expanded trading as far as technology allowed—Marco Polo’s silk route between Europe and China is an example. Many people fear free trade and some predicted a “giant sucking sound” as jobs left the United States for Mexico under the NAFTA. Why do we trade with other nations? Do tariffs that restrict trade bring any benefits?

Patterns and Trends in International Trade Imports are the good and services that we buy from people in other countries. Exports are the goods and services we sell to people in other countries.

Patterns and Trends in International Trade in Goods Manufactured goods represent 55 percent of U. S. imports and 68 percent of exports. Raw materials and semi-manufactured materials represent 14 percent of U. S. exports and 15 percent of imports. The largest export item from the United States is capital goods and the largest import item is automobiles.

Patterns and Trends in International Trade in Services International trade in services such as travel, transportation, and insurance is large and growing. Geographical Patterns of International Trade The United States trades with countries all over the world, but its biggest trading partner is Canada with 20 percent of U. S. exports and 17 percent of U. S. imports. Japan is our second largest trading partner with 8 percent of our exports and 9 percent of our imports.

Patterns and Trends in International Trade Trends in the Volume of Trade In 1960, the United States exported 3. 5 percent of its total output and imported 4 percent of the total amount that American spent on goods and services. In 2003, the United States exported 10 percent of its total output and imported 15 percent of the total amount that American spent on goods and services.

Patterns and Trends in International Trade Net Exports and International Borrowing The value of exports minus imports is called net exports. In 2003, imports exceeded exports in the United States, so net exports were negative $500 billion. When a country imports more than it exports, it must borrow from foreigners or sell some of its assets. When a country exports more than it imports, it must make loans to foreigners or buy some of their assets.

The Gains from International Trade Comparative advantage is the fundamental force that generates trade between nations. The basis for comparative trade is divergent opportunity costs between countries. Nations can increase the consumption of goods and services when they allocate resources to the production of those goods and services for which they have a comparative advantage.

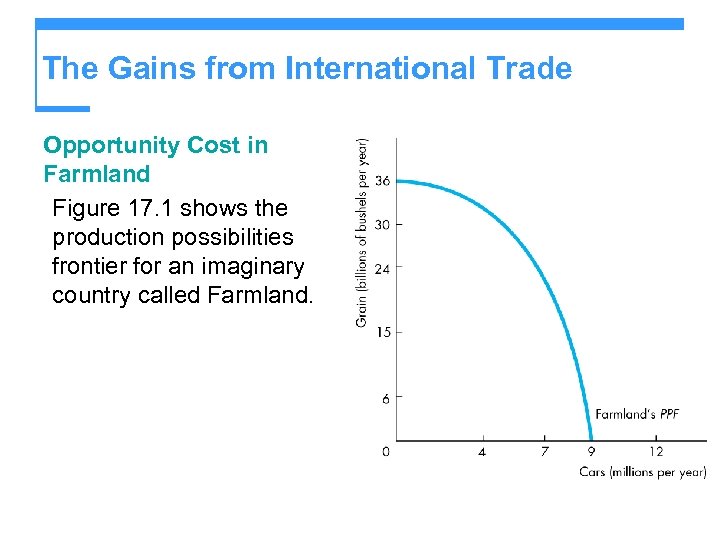

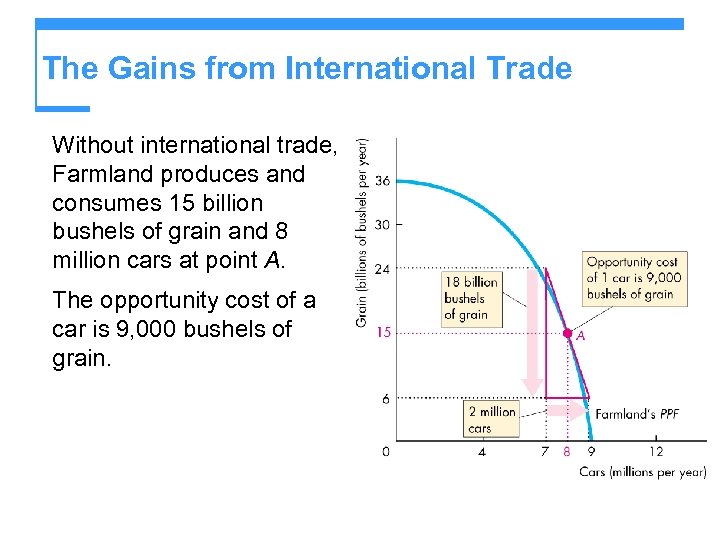

The Gains from International Trade Opportunity Cost in Farmland Figure 17. 1 shows the production possibilities frontier for an imaginary country called Farmland.

The Gains from International Trade Without international trade, Farmland produces and consumes 15 billion bushels of grain and 8 million cars at point A. The opportunity cost of a car is 9, 000 bushels of grain.

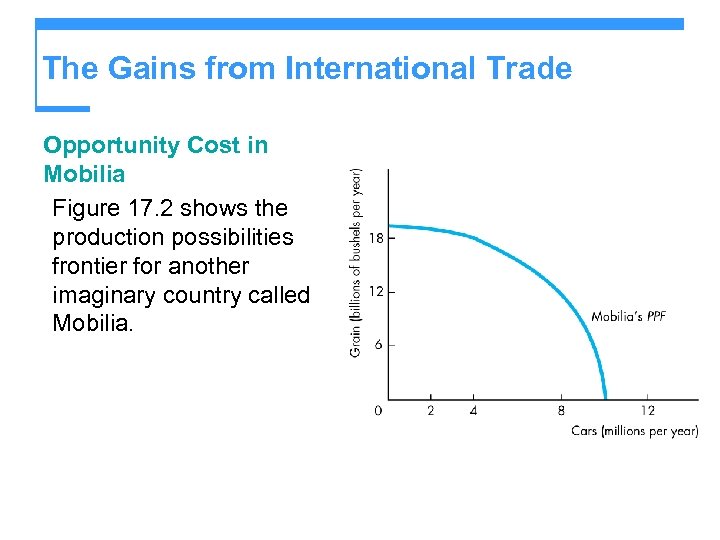

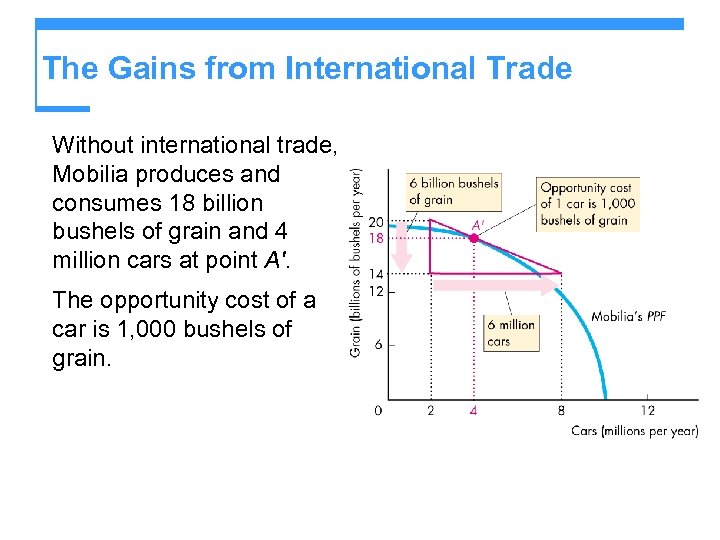

The Gains from International Trade Opportunity Cost in Mobilia Figure 17. 2 shows the production possibilities frontier for another imaginary country called Mobilia.

The Gains from International Trade Without international trade, Mobilia produces and consumes 18 billion bushels of grain and 4 million cars at point A'. The opportunity cost of a car is 1, 000 bushels of grain.

The Gains from International Trade Comparative Advantage Cars are cheaper for Mobilia to produce than for Farmland, because less grain is given up to produce each car. Grain is cheaper for Farmland to produce than for Mobilia because fewer cars are given up to produce each bushel. A country has a comparative advantage in producing a good if it can produce that good at a lower opportunity cost than any other country. Farmland has a comparative advantage in producing grain, and Mobilia has a comparative advantage in producing cars.

The Gains from International Trade The Gains from Trade: Cheaper to Buy Than to Produce If Mobilia bought grain for the price that Farmland produces it, Mobilia could buy 9, 000 bushels of grain for 1 car—a much lower price than the opportunity cost of producing grain in Mobilia. If Farmland bought cars for what Mobilia pays for them, Farmland could buy 1 car for 1, 000 bushels of grain—a much lower price than the opportunity cost of producing cars in Farmland.

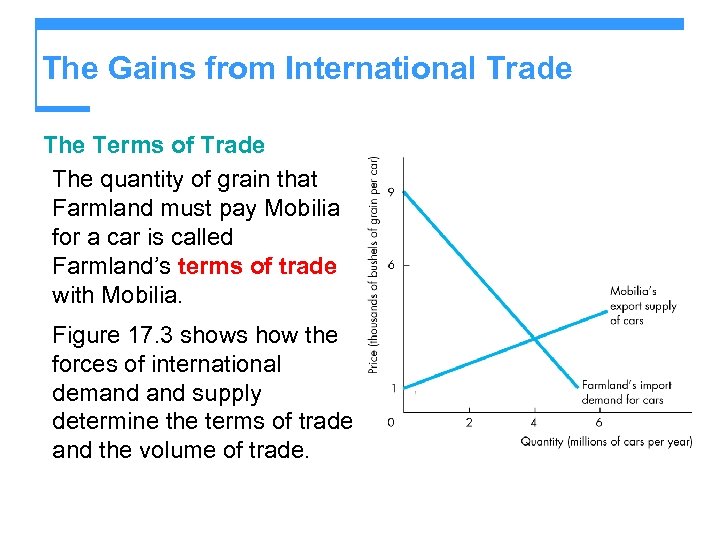

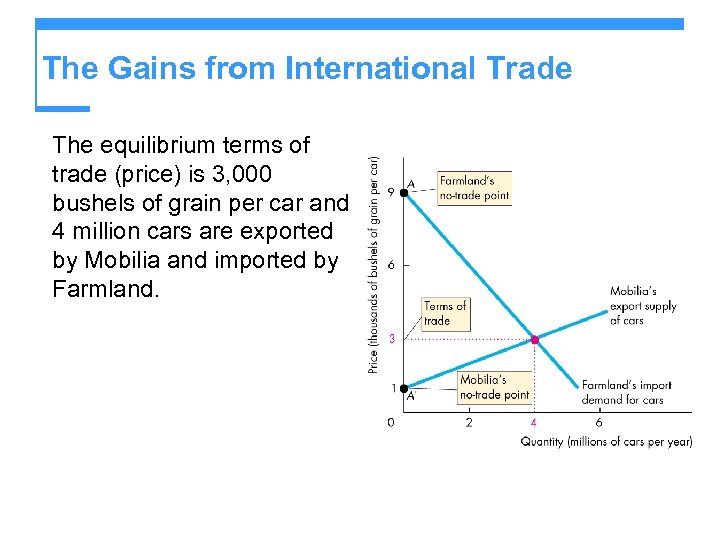

The Gains from International Trade The Terms of Trade The quantity of grain that Farmland must pay Mobilia for a car is called Farmland’s terms of trade with Mobilia. Figure 17. 3 shows how the forces of international demand supply determine the terms of trade and the volume of trade.

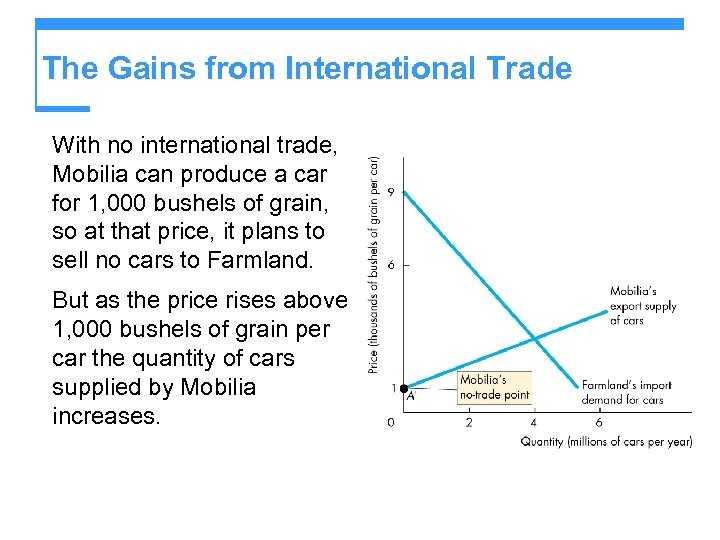

The Gains from International Trade With no international trade, Mobilia can produce a car for 1, 000 bushels of grain, so at that price, it plans to sell no cars to Farmland. But as the price rises above 1, 000 bushels of grain per car the quantity of cars supplied by Mobilia increases.

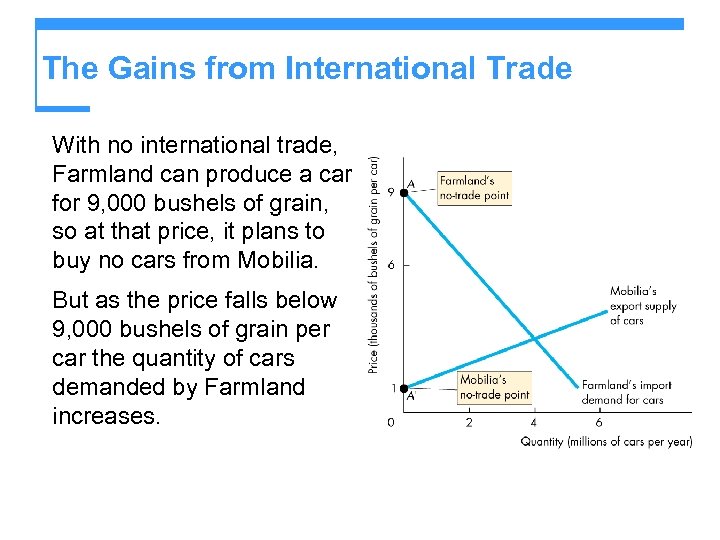

The Gains from International Trade With no international trade, Farmland can produce a car for 9, 000 bushels of grain, so at that price, it plans to buy no cars from Mobilia. But as the price falls below 9, 000 bushels of grain per car the quantity of cars demanded by Farmland increases.

The Gains from International Trade The equilibrium terms of trade (price) is 3, 000 bushels of grain per car and 4 million cars are exported by Mobilia and imported by Farmland.

The Gains from International Trade Balanced Trade The number of cars exported by Mobilia equals the number of cars imported by Farmland pays Mobilia with 12 billion bushels of grain (four million cars multiplied by 3, 000 bushels for each car)—Mobilia imports and Farmland exports 12 billion bushels of grain. Trade is balanced. For each country, the value of exports equals the value of imports— 4 million cars are worth the same as 12 billion bushels of grain.

The Gains from International Trade Changes in Production and Consumption Farmland buys cars at a lower price than it would pay if it made them itself, and sells its grain at a higher price. Mobilia buys grain at a lower price than it would pay if it grew the grain itself, and sells its cars at a higher price. Everyone gains from trade. The production possibilities frontier illustrates the production possibilities of a country, but it does not show the consumption possibilities of a country that engages in international trade.

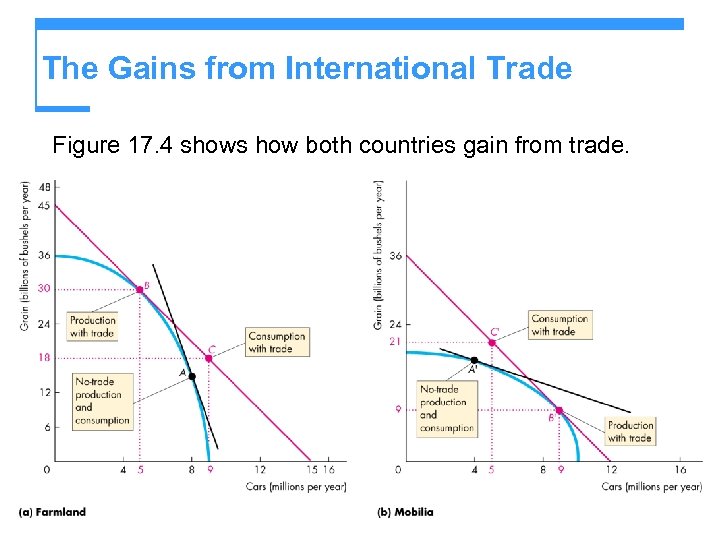

The Gains from International Trade Figure 17. 4 shows how both countries gain from trade.

The Gains from International Trade Calculating the Gains from Trade Farmland increase its consumption of both cars and grain by decreasing car production and increasing grain production until its own opportunity cost of producing cars equals that of the world terms of trade and exchanging grain for cars at those terms of trade. Mobilia increases its consumption of both cars and grain by increasing car production and decreasing grain production until its own opportunity cost of producing cars equals that of the world terms of trade and exchanging cars for grain at those terms of trade.

The Gains from International Trade Gains for All Both countries gain by consuming output combinations outside their respective production possibilities frontier. Trade does not create winners and losers. It creates only winners. Farmers selling grain and Mobilians selling cars face increased demand higher prices. Farmers buying cars and Mobilians buying grain face increased supply and lower prices.

The Gains from International Trade Gains from Trade in Reality Gains from trade occur in the real global economy. The United States buys TVs and VCRs from Korea, machinery from Europe, and fashion goods from Hong Kong and in exchange for machinery, grain, lumber, airplanes, computers, and financial services. Everyone gains from this trade. The combination of diverse preferences and economies of scale create comparative advantages that generate a large volume of international trade in similar but differentiated products.

International Trade Restrictions Governments restrict international trade to protect domestic producers from competition by using two main tools § Tariffs § Nontariff barriers A tariff is a tax that is imposed by the importing country when an imported good crosses its international boundary. A nontariff barrier is any action other than a tariff that restricts international trade.

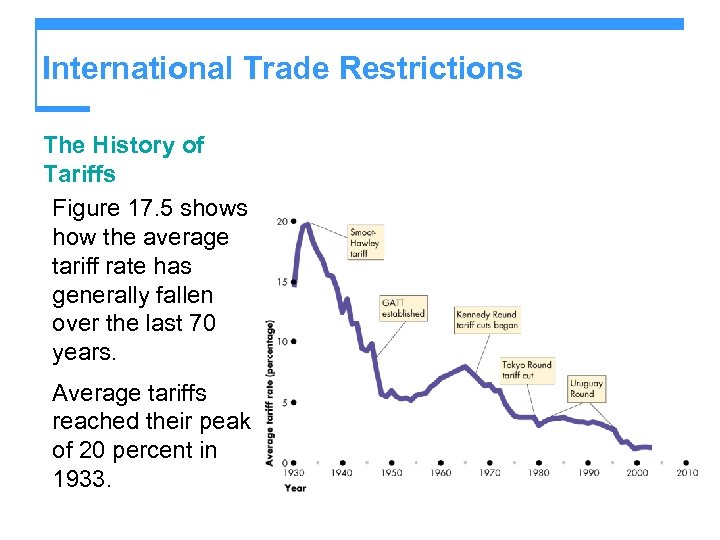

International Trade Restrictions The History of Tariffs Figure 17. 5 shows how the average tariff rate has generally fallen over the last 70 years. Average tariffs reached their peak of 20 percent in 1933.

International Trade Restrictions The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is an agreement between nations to have a series of trade negotiations, or “rounds, ” to reduce tariffs on international trade. The United States joined GATT in 1947. Subsequent rounds of the GATT occurred in the 1960 s, late 1970 s and 1980 s, resulting in gradual decline in the average tariff rate in the United States

International Trade Restrictions The Uruguay round was the most ambitious and lead to the creation of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The United States became a WTO member in 1994. WTO membership brings greater obligations to follow the GATT rules governing trade.

International Trade Restrictions In 1994, the United States became party to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), under which trade barriers between Canada, Mexico and the United States are being lowered. The European Union (EU) is an organization of European countries that have agreed to eliminate trade barriers among them. The Asia-Pacific Economic group (APEC) is another agreement to reduce trade barriers among East Asian countries, including China.

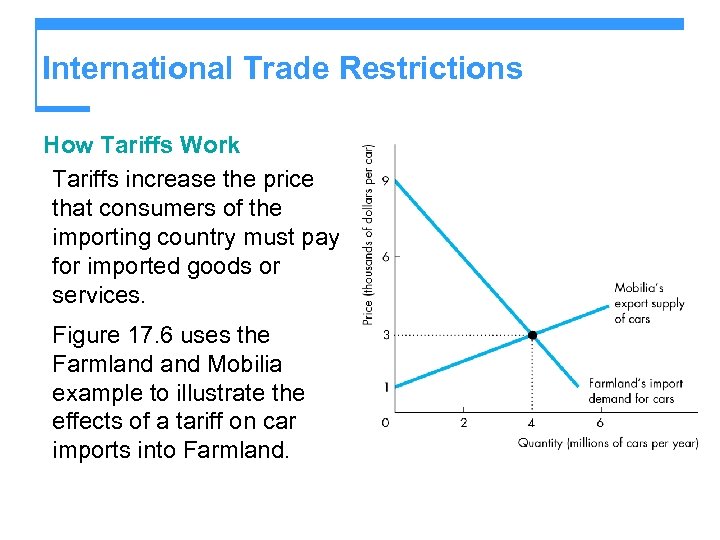

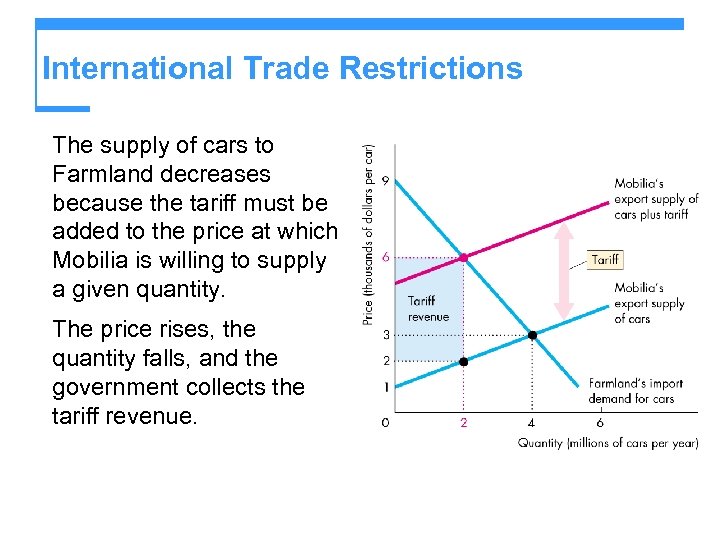

International Trade Restrictions How Tariffs Work Tariffs increase the price that consumers of the importing country must pay for imported goods or services. Figure 17. 6 uses the Farmland Mobilia example to illustrate the effects of a tariff on car imports into Farmland.

International Trade Restrictions The supply of cars to Farmland decreases because the tariff must be added to the price at which Mobilia is willing to supply a given quantity. The price rises, the quantity falls, and the government collects the tariff revenue.

International Trade Restrictions The supply curve shifts leftward and the vertical distance between the free-trade supply curve and the new supply curve equals the amount of the tariff. The price of a car in Farmland rises. The quantity of cars imported by Farmland decreases. The Farmland government collects tariff revenue. Resources use is inefficient. The value of exports changes by the same amount as the value of imports and trade remains balanced.

International Trade Restrictions Nontariff Barriers There are two main types of non-tariff barriers to trade. A quota is a quantitative restriction on the import of a particular good, which specifies the maximum amount of the good that may be imported in a given period of time. A voluntary export restraint (VER) is an agreement between two governments in which the government of the exporting country agrees to restrain the volume of its own exports.

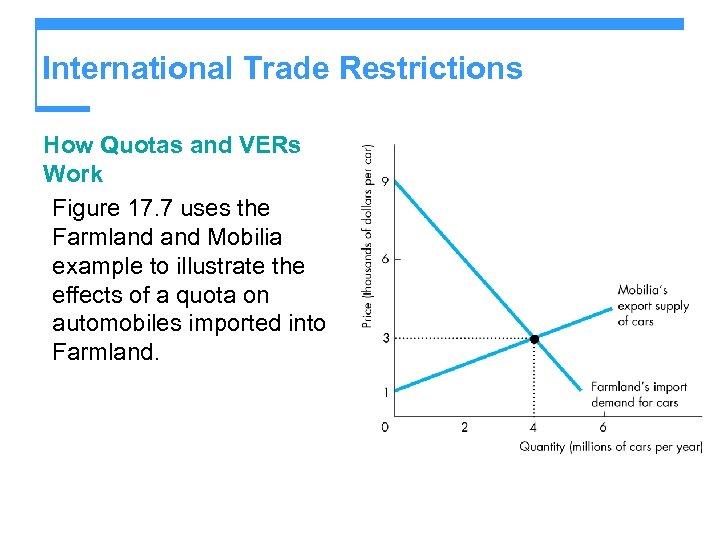

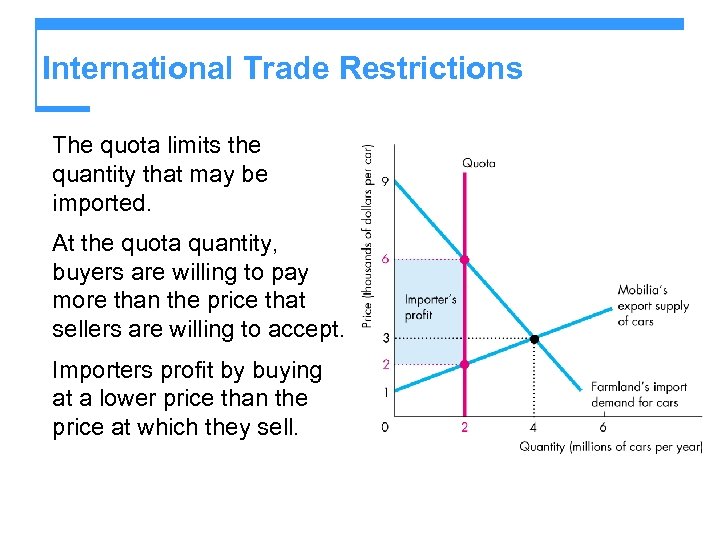

International Trade Restrictions How Quotas and VERs Work Figure 17. 7 uses the Farmland Mobilia example to illustrate the effects of a quota on automobiles imported into Farmland.

International Trade Restrictions The quota limits the quantity that may be imported. At the quota quantity, buyers are willing to pay more than the price that sellers are willing to accept. Importers profit by buying at a lower price than the price at which they sell.

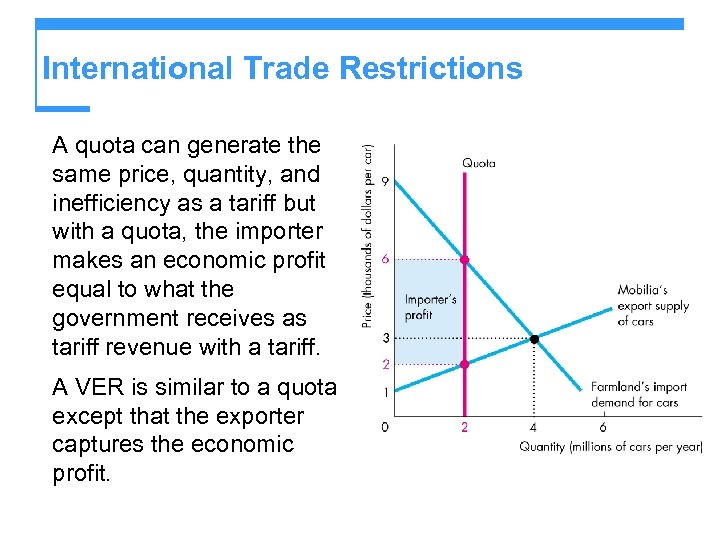

International Trade Restrictions A quota can generate the same price, quantity, and inefficiency as a tariff but with a quota, the importer makes an economic profit equal to what the government receives as tariff revenue with a tariff. A VER is similar to a quota except that the exporter captures the economic profit.

The Case Against Protection Despite the fact that free trade promotes prosperity for all, trade is restricted. It is often argued that international trade should be restricted to § Protect national security § Protect infant industries § Punish dumping None of these arguments bear scrutiny.

The Case Against Protection Other fatally flawed arguments for protection are that it § Saves jobs § Allows us to compete with cheap foreign labor § Brings diversity and stability to our economy § Penalizes nations with lax environmental standards § Protects national culture § Prevents rich nations from exploiting poor ones

The Case Against Protection The National Security Argument The national security argument is that a country must protect domestic industries that make defense equipment and armaments, and those industries that provide the raw material necessary for defense production. The argument is flawed for two reasons: (1) In time of war, there is no industry that does not contribute to national defense, so it is a plea for economic isolation. (2) It is less inefficient to subsidize defense than to restrict trade with a tariff.

The Case Against Protection The Infant Industry Argument The infant-industry argument is that it is necessary to protect a new industry from import competition to enable it to grow into a mature industry that can compete in world markets. This argument is based on the concept of dynamic competitive advantage, which can arise from learning-bydoing.

The Case Against Protection Learning-by-doing is a powerful engine of productivity growth, but this fact does not justify protection. Government action is needed to encourage learning-bydoing only when its benefits spill over to other parts of the economy. And even in this case, it is more efficient to subsidize an infant industry than to protect it by restricting trade.

The Case Against Protection The Dumping Argument Dumping occurs when foreign a firm sells its exports at a lower price than its cost of production. Dumping is seen as a justification for a tariff to prevent a foreign firm driving domestic firms out of business and then raising its price. This argument is flawed because: It is virtually impossible to determine a firm’s costs; If there was a natural global monopoly, it would be more efficient to regulate it than to impose a tariff against it.

The Case Against Protection Saves Jobs The idea that buying foreign goods costs domestic jobs is wrong. It destroys some jobs and creates other better jobs. It also increases foreign incomes and enables foreigners to buy more domestic production. Protection to save particular jobs is very costly.

The Case Against Protection Allows us to Compete with Cheap Foreign Labor The idea that a high-wage country cannot compete with a low-wage country is wrong. Low-wage labor is less productive than high-wage labor. And wages and productivity tell us nothing about the source of gains from trade, which is comparative advantage.

The Case Against Protection Brings Diversity and Stability The idea that protection brings diversity of production and greater stability of income is wrong. A nation can achieve diversity and stability through its international investments

The Case Against Protection Penalizes Lax Environmental Standards The idea that protection is good for the environment is wrong. Free trade increases incomes and poor countries have significantly lower environmental standards than rich countries. These countries cannot afford to spend as much on the environment as a rich country can and sometimes they have a comparative advantage at doing “dirty” work, which helps the global environment achieve higher environmental standards.

The Case Against Protection Protects National Culture The idea that trade restrictions protect the national culture is wrong. This argument is not heard in the United States as much as it is heard in Canada and European countries. Many countries are afraid of the “Americanization” of their culture through the prominence of American films, television programs, art, literature, and even cuisine in world markets.

The Case Against Protection Protecting “cultural” industries is a form of rent seeking, using cultural identity to eliminate competition from other culturally related goods and services. The surest way to eliminate a culture is to impoverish a nation.

The Case Against Protection Prevents Rich Countries from Exploiting Poorer Countries The idea that trade restrictions prevent rich countries from exploiting poorer countries is wrong. Free trade is the best way of raising wages and improving working conditions in poor countries.

The Case Against Protection The most compelling argument against protection is that it invites retaliation. We saw retaliation to the Smoot-Hawley Act in the United States during the Great Depression. And we see it today as the world reacts to high U. S. tariffs on steel and agriculture.

Why Is International Trade Restricted? The two key reasons why international trade is restricted are § Tariff revenue § Rent seeking

Why Is International Trade Restricted? Tariff Revenue It is costly for governments to collect taxes on income and domestic sales. It is cheaper for governments to collect taxes on international transactions because international trade is carefully monitored. This source of revenue is especially attractive to governments in developing nations.

Why Is International Trade Restricted? Rent Seeking Rent seeking is lobbying and other political activities that seek to capture the gains from trade. Despite the fact that protection is inefficient, governments respond to the demands of those who gain from protection and ignore the demands of those who gain from free trade because protection brings concentrated gains and diffused losses.

Why Is International Trade Restricted? Compensating Losers The gains from free trade exceed the losses, and sometimes free trade agreements address the issue of the distribution of gains from trade by compensating those who lose from free trade. For example, under NAFTA, a $56 million fund was created to support and retrain workers who lot their jobs from foreign competition resulting from the agreement.

THE END

dfb7cbe1a228a2886804137a055df634.ppt