f704c36e5fbdacfb2da2f1e1221c8e04.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 31

Tone in Cushitic Maarten Mous Leiden University

Tone in Cushitic Maarten Mous Leiden University

![Stress languages • [-tone, +stress] • Highland East Cushitic: K’abeena, Sidamo Stress languages • [-tone, +stress] • Highland East Cushitic: K’abeena, Sidamo](https://present5.com/presentation/f704c36e5fbdacfb2da2f1e1221c8e04/image-2.jpg) Stress languages • [-tone, +stress] • Highland East Cushitic: K’abeena, Sidamo

Stress languages • [-tone, +stress] • Highland East Cushitic: K’abeena, Sidamo

K’abeena • ultimate or penultimate syllable has stress (depending on final vowel whispered or not) • correlation between stress/whispered final vowel and word class • linked to case, converb vs imperative, polar questions • no distinctive function at lexical level

K’abeena • ultimate or penultimate syllable has stress (depending on final vowel whispered or not) • correlation between stress/whispered final vowel and word class • linked to case, converb vs imperative, polar questions • no distinctive function at lexical level

Somali Underlying accent system with tonal realisation Banti (1988) Absolutive on the ultimate or penultimate mora: underlying accent. Genitive: accentual pattern of ultimate accent Nominative allomorphs involving adding an (empty) mora to the end.

Somali Underlying accent system with tonal realisation Banti (1988) Absolutive on the ultimate or penultimate mora: underlying accent. Genitive: accentual pattern of ultimate accent Nominative allomorphs involving adding an (empty) mora to the end.

Rendille Accent language underlyingly Realised as tone with downdrift (Pillinger 1989)

Rendille Accent language underlyingly Realised as tone with downdrift (Pillinger 1989)

`Afar Domain of high tone is phrase. High tone on one syllable in first word of NP High tone on one last 3 syllables of that word. H on accented syllable of that word (only minority of words have an accent); if there is no accented syllable H on final (default) Hayward (1991).

`Afar Domain of high tone is phrase. High tone on one syllable in first word of NP High tone on one last 3 syllables of that word. H on accented syllable of that word (only minority of words have an accent); if there is no accented syllable H on final (default) Hayward (1991).

Awngi • Joswig, Andreas. The phonology of Awngi. Ms • Awngi Phonology. pdf

Awngi • Joswig, Andreas. The phonology of Awngi. Ms • Awngi Phonology. pdf

Oromo Banti Two Cushitic systems. pdf

Oromo Banti Two Cushitic systems. pdf

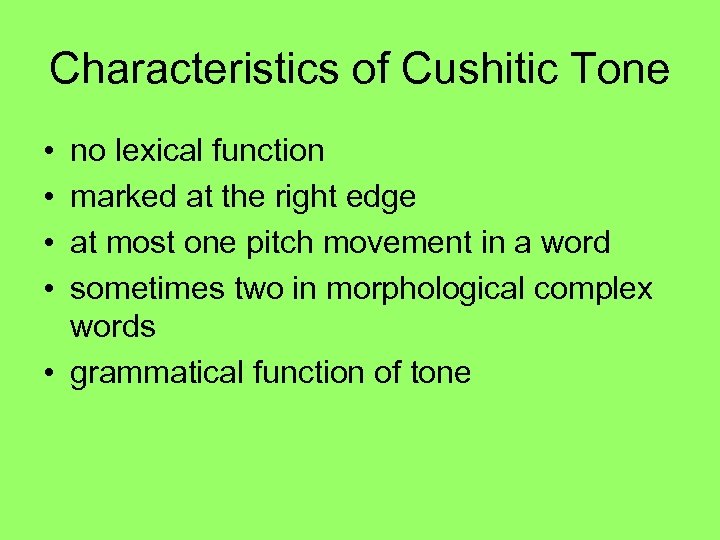

Characteristics of Cushitic Tone • • no lexical function marked at the right edge at most one pitch movement in a word sometimes two in morphological complex words • grammatical function of tone

Characteristics of Cushitic Tone • • no lexical function marked at the right edge at most one pitch movement in a word sometimes two in morphological complex words • grammatical function of tone

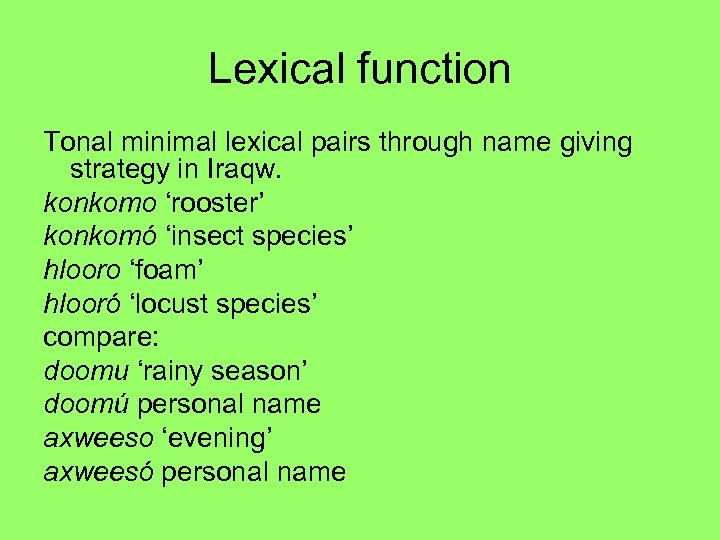

Lexical function Tonal minimal lexical pairs through name giving strategy in Iraqw. konkomo ‘rooster’ konkomó ‘insect species’ hlooro ‘foam’ hlooró ‘locust species’ compare: doomu ‘rainy season’ doomú personal name axweeso ‘evening’ axweesó personal name

Lexical function Tonal minimal lexical pairs through name giving strategy in Iraqw. konkomo ‘rooster’ konkomó ‘insect species’ hlooro ‘foam’ hlooró ‘locust species’ compare: doomu ‘rainy season’ doomú personal name axweeso ‘evening’ axweesó personal name

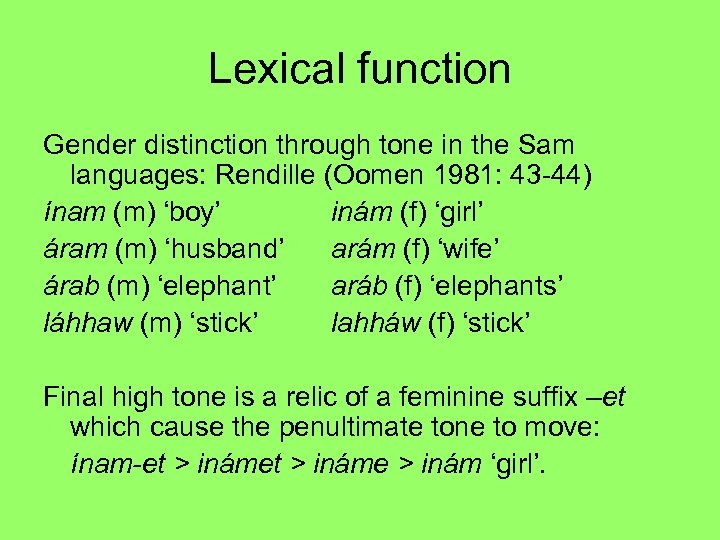

Lexical function Gender distinction through tone in the Sam languages: Rendille (Oomen 1981: 43 -44) ínam (m) ‘boy’ inám (f) ‘girl’ áram (m) ‘husband’ arám (f) ‘wife’ árab (m) ‘elephant’ aráb (f) ‘elephants’ láhhaw (m) ‘stick’ lahháw (f) ‘stick’ Final high tone is a relic of a feminine suffix –et which cause the penultimate tone to move: ínam-et > ináme > inám ‘girl’.

Lexical function Gender distinction through tone in the Sam languages: Rendille (Oomen 1981: 43 -44) ínam (m) ‘boy’ inám (f) ‘girl’ áram (m) ‘husband’ arám (f) ‘wife’ árab (m) ‘elephant’ aráb (f) ‘elephants’ láhhaw (m) ‘stick’ lahháw (f) ‘stick’ Final high tone is a relic of a feminine suffix –et which cause the penultimate tone to move: ínam-et > ináme > inám ‘girl’.

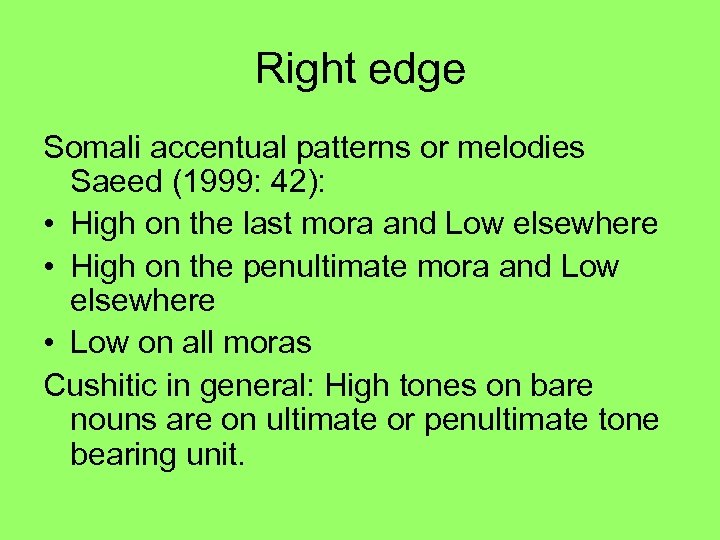

Right edge Somali accentual patterns or melodies Saeed (1999: 42): • High on the last mora and Low elsewhere • High on the penultimate mora and Low elsewhere • Low on all moras Cushitic in general: High tones on bare nouns are on ultimate or penultimate tone bearing unit.

Right edge Somali accentual patterns or melodies Saeed (1999: 42): • High on the last mora and Low elsewhere • High on the penultimate mora and Low elsewhere • Low on all moras Cushitic in general: High tones on bare nouns are on ultimate or penultimate tone bearing unit.

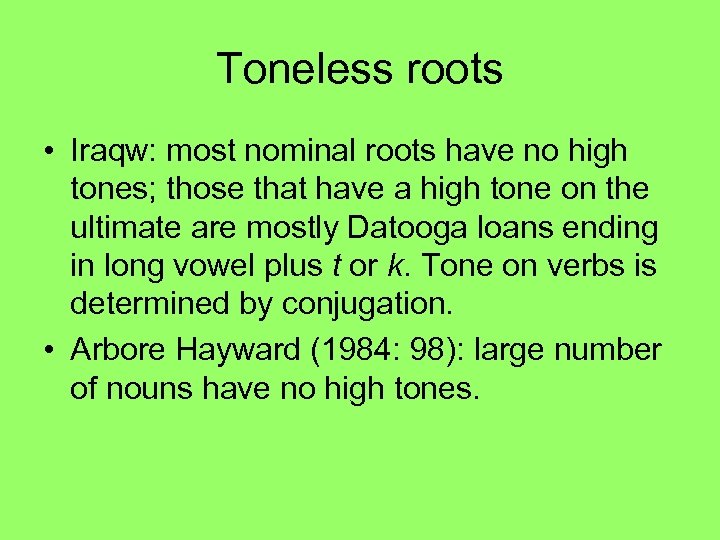

Toneless roots • Iraqw: most nominal roots have no high tones; those that have a high tone on the ultimate are mostly Datooga loans ending in long vowel plus t or k. Tone on verbs is determined by conjugation. • Arbore Hayward (1984: 98): large number of nouns have no high tones.

Toneless roots • Iraqw: most nominal roots have no high tones; those that have a high tone on the ultimate are mostly Datooga loans ending in long vowel plus t or k. Tone on verbs is determined by conjugation. • Arbore Hayward (1984: 98): large number of nouns have no high tones.

Tone in function words Oromo: hín focus marker hin negation marker Somali: Adpositional particles have high tone: lá ‘with’, kú ‘in’ but adverbial clitics are toneless: wada ‘together’ and kala ‘apart’

Tone in function words Oromo: hín focus marker hin negation marker Somali: Adpositional particles have high tone: lá ‘with’, kú ‘in’ but adverbial clitics are toneless: wada ‘together’ and kala ‘apart’

Tone on suffixes Iraqw demonstrative and possessive suffixes are high; specific indefinite suffixes toneless; personal pronouns high. Series of high tones: gajéér-’éé-dá-r ‘isa work-my-that-of yesterday ‘that work of mine of yesterday’.

Tone on suffixes Iraqw demonstrative and possessive suffixes are high; specific indefinite suffixes toneless; personal pronouns high. Series of high tones: gajéér-’éé-dá-r ‘isa work-my-that-of yesterday ‘that work of mine of yesterday’.

not more than 1 pitch movement if more than 1 high than in morphological complex word Occasionally two movements: Somali: gúrigíi ‘the house (remote)’ (Saeed 1999: 43). Penultimate high plus high tones definite suffix. Arbore: Arbore lúkku-t-ásut ‘his hens’ (Hayward 1984: 99). Penultimate high plus high tone possessive suffix.

not more than 1 pitch movement if more than 1 high than in morphological complex word Occasionally two movements: Somali: gúrigíi ‘the house (remote)’ (Saeed 1999: 43). Penultimate high plus high tones definite suffix. Arbore: Arbore lúkku-t-ásut ‘his hens’ (Hayward 1984: 99). Penultimate high plus high tone possessive suffix.

Grammatical function of tone • • • high toned word classes high toned suffixes double high tone suffixes high tone in verb conjugation tone as grammatical morpheme right tone shift as grammatical morpheme

Grammatical function of tone • • • high toned word classes high toned suffixes double high tone suffixes high tone in verb conjugation tone as grammatical morpheme right tone shift as grammatical morpheme

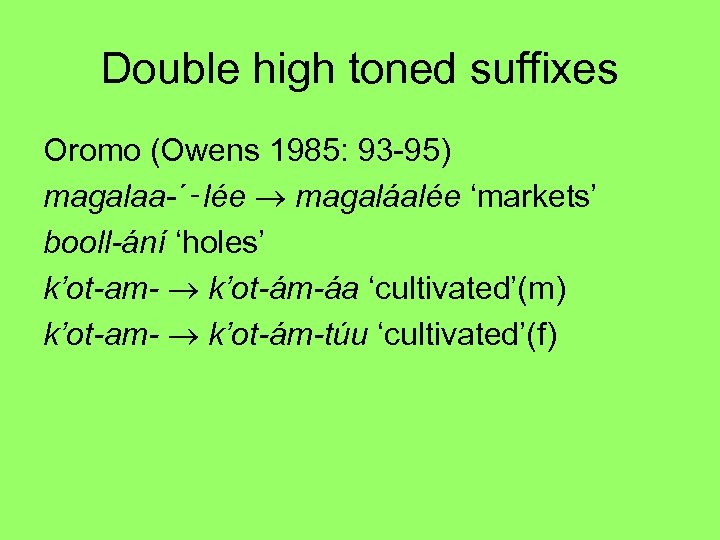

Double high toned suffixes Oromo (Owens 1985: 93 -95) magalaa-´‑lée magaláalée ‘markets’ booll-ání ‘holes’ k’ot-am- k’ot-ám-áa ‘cultivated’(m) k’ot-am- k’ot-ám-túu ‘cultivated’(f)

Double high toned suffixes Oromo (Owens 1985: 93 -95) magalaa-´‑lée magaláalée ‘markets’ booll-ání ‘holes’ k’ot-am- k’ot-ám-áa ‘cultivated’(m) k’ot-am- k’ot-ám-túu ‘cultivated’(f)

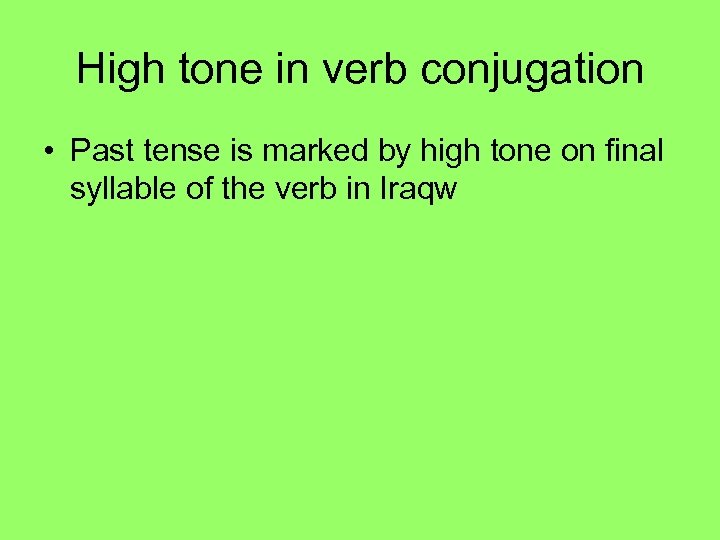

High tone in verb conjugation • Past tense is marked by high tone on final syllable of the verb in Iraqw

High tone in verb conjugation • Past tense is marked by high tone on final syllable of the verb in Iraqw

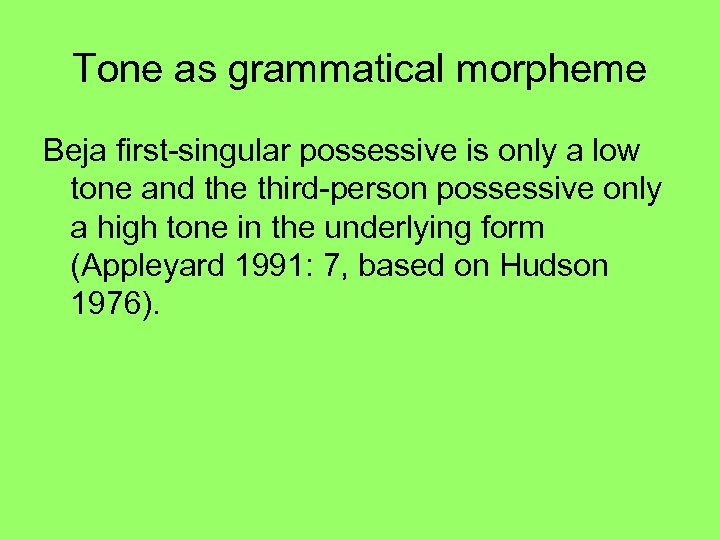

Tone as grammatical morpheme Beja first-singular possessive is only a low tone and the third-person possessive only a high tone in the underlying form (Appleyard 1991: 7, based on Hudson 1976).

Tone as grammatical morpheme Beja first-singular possessive is only a low tone and the third-person possessive only a high tone in the underlying form (Appleyard 1991: 7, based on Hudson 1976).

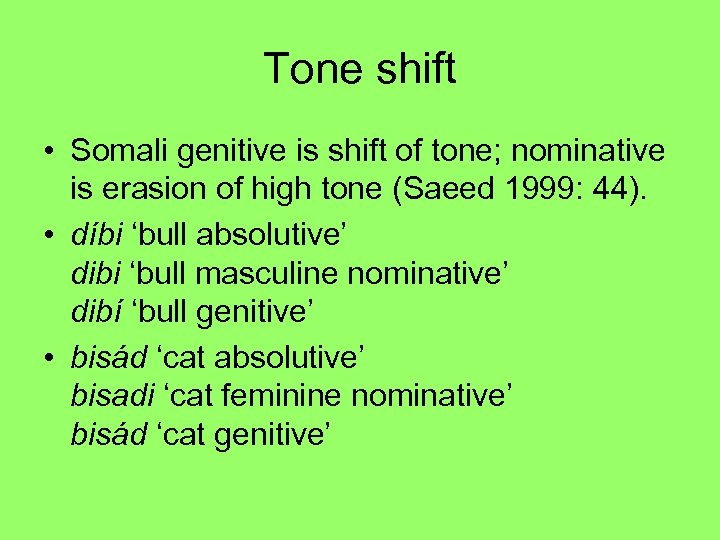

Tone shift • Somali genitive is shift of tone; nominative is erasion of high tone (Saeed 1999: 44). • díbi ‘bull absolutive’ dibi ‘bull masculine nominative’ dibí ‘bull genitive’ • bisád ‘cat absolutive’ bisadi ‘cat feminine nominative’ bisád ‘cat genitive’

Tone shift • Somali genitive is shift of tone; nominative is erasion of high tone (Saeed 1999: 44). • díbi ‘bull absolutive’ dibi ‘bull masculine nominative’ dibí ‘bull genitive’ • bisád ‘cat absolutive’ bisadi ‘cat feminine nominative’ bisád ‘cat genitive’

Culminative behaviour of tone • lowering previous high tones • lowering following high

Culminative behaviour of tone • lowering previous high tones • lowering following high

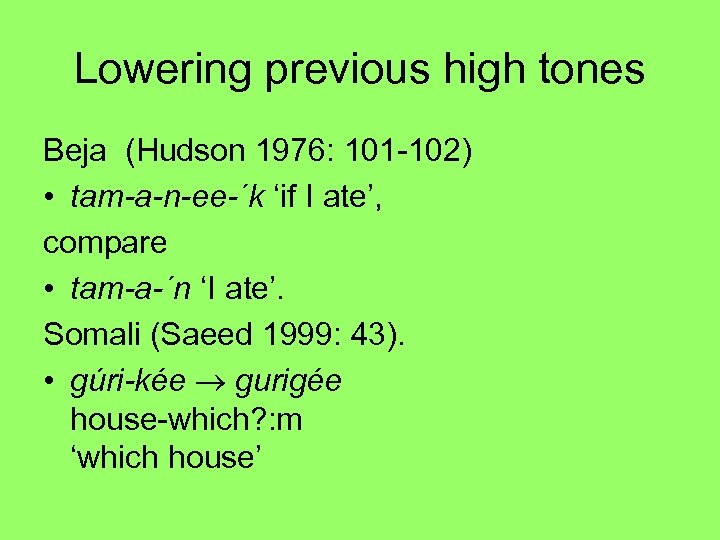

Lowering previous high tones Beja (Hudson 1976: 101 -102) • tam-a-n-ee-´k ‘if I ate’, compare • tam-a-´n ‘I ate’. Somali (Saeed 1999: 43). • gúri-kée gurigée house-which? : m ‘which house’

Lowering previous high tones Beja (Hudson 1976: 101 -102) • tam-a-n-ee-´k ‘if I ate’, compare • tam-a-´n ‘I ate’. Somali (Saeed 1999: 43). • gúri-kée gurigée house-which? : m ‘which house’

Lowering following high tone Beja (Hudson 1976: 101 -102): high tone of the root suppresses the accent of the past tense suffix ‑`a

Lowering following high tone Beja (Hudson 1976: 101 -102): high tone of the root suppresses the accent of the past tense suffix ‑`a

Tonal phonetics • Pillinger’s analysis of Rendille.

Tonal phonetics • Pillinger’s analysis of Rendille.

Absence of common tone rules • • no high tone spread no tone assimilation downdrift but no downstep no final lowering

Absence of common tone rules • • no high tone spread no tone assimilation downdrift but no downstep no final lowering

Tone or Accent • Tone: phonemic function for pitch at word level • Accent: distribution of prominence at word level. At least one stressed syllable. • Cushitic languages: pitch but not all words have a “stressed” syllable. • + tone –stress in Hyman’s (2006) typology.

Tone or Accent • Tone: phonemic function for pitch at word level • Accent: distribution of prominence at word level. At least one stressed syllable. • Cushitic languages: pitch but not all words have a “stressed” syllable. • + tone –stress in Hyman’s (2006) typology.

Tone bearing unit is mora • Somali: (Banti 1988: 13; Saeed 1999: 41) • Dhaasanac: (Tosco 2001: 36) • Rendille: máàr ‘bullock’ vs màár ‘heiffer’ (Pillinger 1989)

Tone bearing unit is mora • Somali: (Banti 1988: 13; Saeed 1999: 41) • Dhaasanac: (Tosco 2001: 36) • Rendille: máàr ‘bullock’ vs màár ‘heiffer’ (Pillinger 1989)

Tone and intonation • Polar question intonation • No general question intonation • Sentence backgrounding by intonation

Tone and intonation • Polar question intonation • No general question intonation • Sentence backgrounding by intonation

Stress ánd tone • Awngi stress independent of tone. • Stress falls on the penultimate and is accompanied by a slight rise in pitch. • Four tones: High, Mid, Low, High-Mid Hetzron (1997: 483). Reanalysed as High & Low by Joswig (2006) • Iraqw has stress realised by length, independent of tone

Stress ánd tone • Awngi stress independent of tone. • Stress falls on the penultimate and is accompanied by a slight rise in pitch. • Four tones: High, Mid, Low, High-Mid Hetzron (1997: 483). Reanalysed as High & Low by Joswig (2006) • Iraqw has stress realised by length, independent of tone

Historical developments • tone > stress in Highland East Cushitic under influence from Semitic according to Tosco. • gender by tone in proto East Cushitic according to Appleyard (1991) but see Oomen’s proposal for Rendille above. • emergence of some tonal oppositions in South Cushitic according to Kiessling (2002)

Historical developments • tone > stress in Highland East Cushitic under influence from Semitic according to Tosco. • gender by tone in proto East Cushitic according to Appleyard (1991) but see Oomen’s proposal for Rendille above. • emergence of some tonal oppositions in South Cushitic according to Kiessling (2002)