6f8b8a8d886bdbecd92fd32de242ef6f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 22

Today’s Topics • Bayes’ Rule – so you can start on HW 3’s code, we will put “full joint prob tables” on hold until after this lecture Thomas Bayes • Naïve Bayes (NB) 1701 -1761 • Nannon and NB 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 1

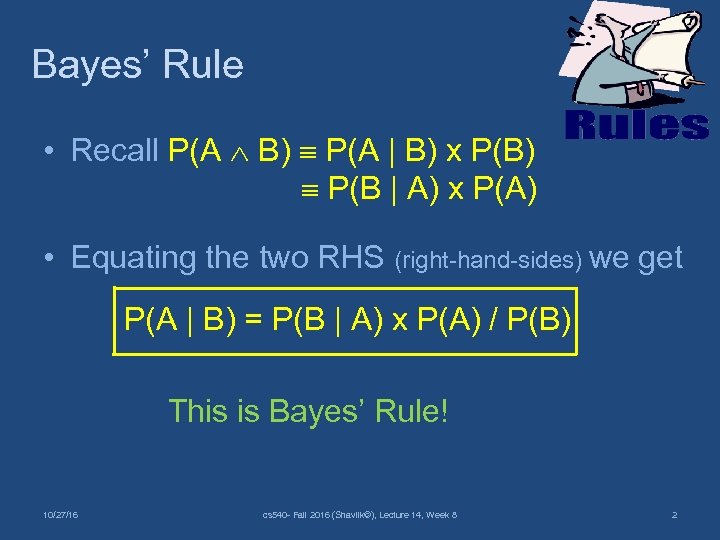

Bayes’ Rule • Recall P(A B) P(A | B) x P(B) P(B | A) x P(A) • Equating the two RHS (right-hand-sides) we get P(A | B) = P(B | A) x P(A) / P(B) This is Bayes’ Rule! 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 2

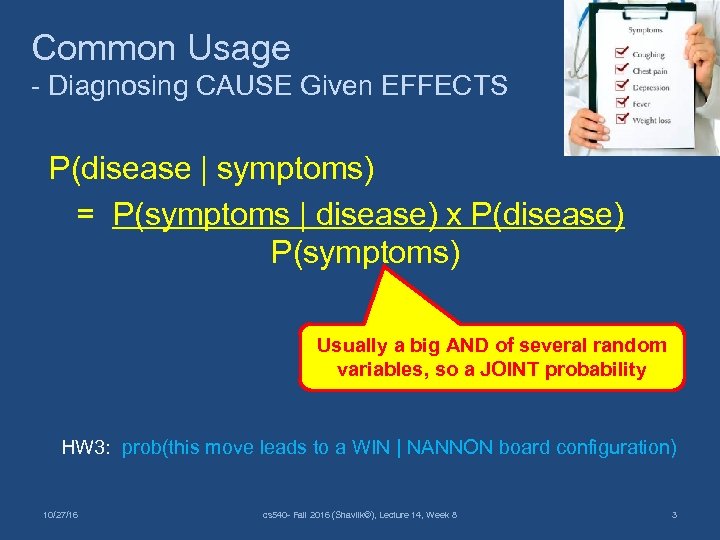

Common Usage - Diagnosing CAUSE Given EFFECTS P(disease | symptoms) = P(symptoms | disease) x P(disease) P(symptoms) Usually a big AND of several random variables, so a JOINT probability HW 3: prob(this move leads to a WIN | NANNON board configuration) 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 3

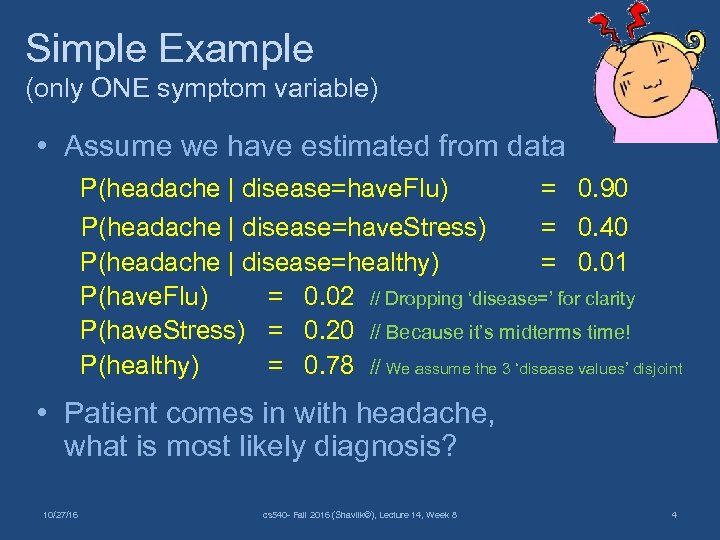

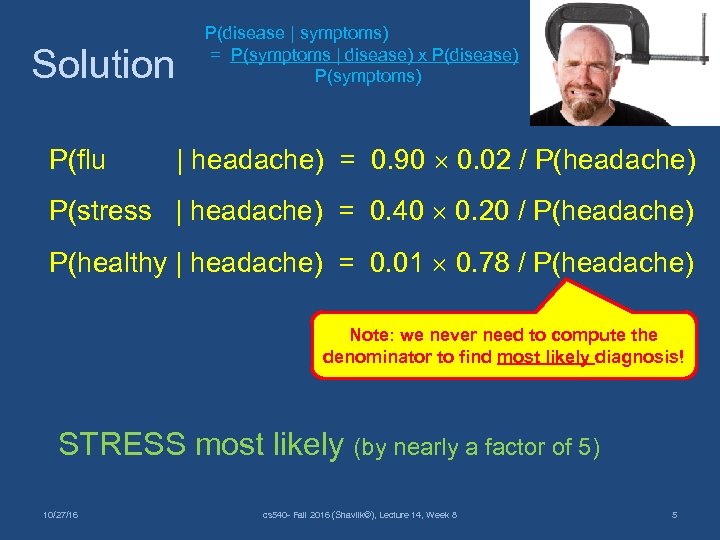

Simple Example (only ONE symptom variable) • Assume we have estimated from data P(headache | disease=have. Flu) = 0. 90 P(headache | disease=have. Stress) = 0. 40 P(headache | disease=healthy) = 0. 01 P(have. Flu) = 0. 02 // Dropping ‘disease=’ for clarity P(have. Stress) = 0. 20 // Because it’s midterms time! P(healthy) = 0. 78 // We assume the 3 ‘disease values’ disjoint • Patient comes in with headache, what is most likely diagnosis? 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 4

Solution P(flu P(disease | symptoms) = P(symptoms | disease) x P(disease) P(symptoms) | headache) = 0. 90 0. 02 / P(headache) P(stress | headache) = 0. 40 0. 20 / P(headache) P(healthy | headache) = 0. 01 0. 78 / P(headache) Note: we never need to compute the denominator to find most likely diagnosis! STRESS most likely (by nearly a factor of 5) 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 5

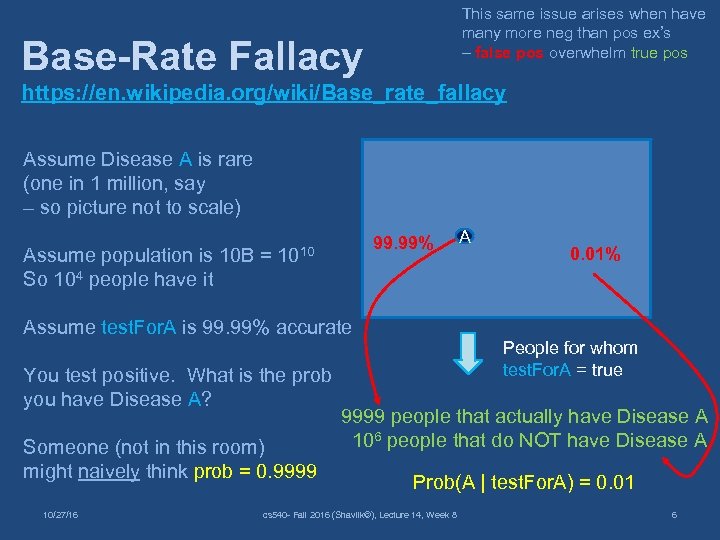

This same issue arises when have many more neg than pos ex’s – false pos overwhelm true pos Base-Rate Fallacy https: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Base_rate_fallacy Assume Disease A is rare (one in 1 million, say – so picture not to scale) 99. 99% Assume population is 10 B = 1010 So 104 people have it Assume test. For. A is 99. 99% accurate You test positive. What is the prob you have Disease A? Someone (not in this room) might naively think prob = 0. 9999 10/27/16 A 0. 01% People for whom test. For. A = true 9999 people that actually have Disease A 106 people that do NOT have Disease A Prob(A | test. For. A) = 0. 01 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 6

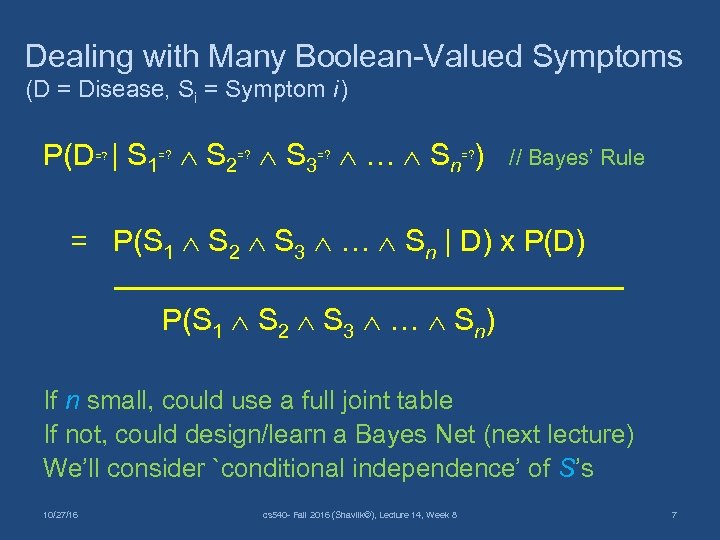

Dealing with Many Boolean-Valued Symptoms (D = Disease, Si = Symptom i ) P(D | S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn ) =? =? =? // Bayes’ Rule = P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn | D) x P(D) P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) If n small, could use a full joint table If not, could design/learn a Bayes Net (next lecture) We’ll consider `conditional independence’ of S’s 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 7

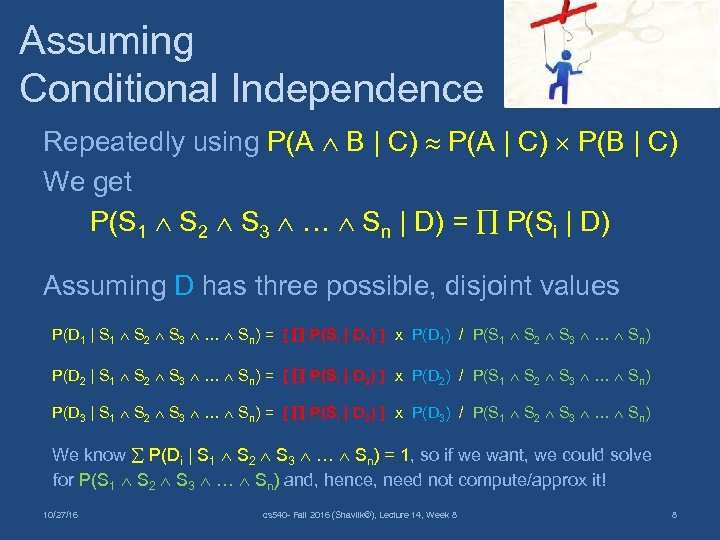

Assuming Conditional Independence Repeatedly using P(A B | C) P(A | C) P(B | C) We get P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn | D) = P(Si | D) Assuming D has three possible, disjoint values P(D 1 | S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) = [ P(Si | D 1) ] x P(D 1) / P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) P(D 2 | S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) = [ P(Si | D 2) ] x P(D 2) / P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) P(D 3 | S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) = [ P(Si | D 3) ] x P(D 3) / P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) We know P(Di | S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) = 1, so if we want, we could solve for P(S 1 S 2 S 3 … Sn) and, hence, need not compute/approx it! 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 8

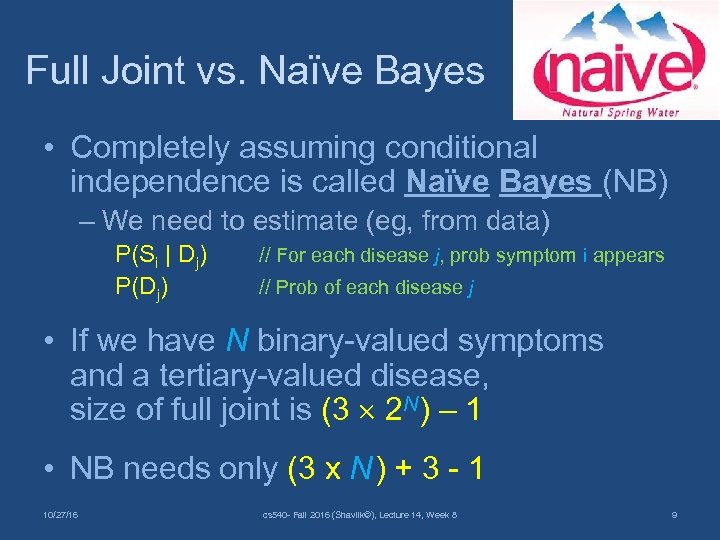

Full Joint vs. Naïve Bayes • Completely assuming conditional independence is called Naïve Bayes (NB) – We need to estimate (eg, from data) P(Si | Dj) P(Dj) // For each disease j, prob symptom i appears // Prob of each disease j • If we have N binary-valued symptoms and a tertiary-valued disease, size of full joint is (3 2 N ) – 1 • NB needs only (3 x N ) + 3 - 1 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 9

![Naïve Bayes Example (for simplicity, ignore m-estimates [later] here) Dataset S 1 S 2 Naïve Bayes Example (for simplicity, ignore m-estimates [later] here) Dataset S 1 S 2](https://present5.com/presentation/6f8b8a8d886bdbecd92fd32de242ef6f/image-10.jpg)

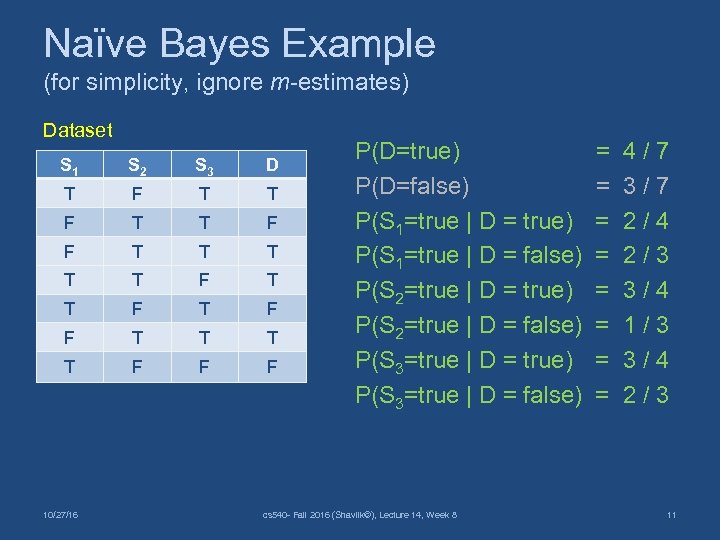

Naïve Bayes Example (for simplicity, ignore m-estimates [later] here) Dataset S 1 S 2 S 3 D T F T T F F T T T F T F F T T F F F P(D=true) P(D=false) P(S 1=true | D = true) P(S 1=true | D = false) P(S 2=true | D = true) P(S 2=true | D = false) P(S 3=true | D = true) P(S 3=true | D = false) = = = = ‘Law of Excluded Middle’ P(S 3=true | D=false) + P(S 3=false | D=false) = 1 so no need for the P(Si=false | D=? ) estimates 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 10

Naïve Bayes Example (for simplicity, ignore m-estimates) Dataset S 1 S 2 S 3 D T F T T F F T T T F T F F T T F F F 10/27/16 P(D=true) P(D=false) P(S 1=true | D = true) P(S 1=true | D = false) P(S 2=true | D = true) P(S 2=true | D = false) P(S 3=true | D = true) P(S 3=true | D = false) cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 = = = = 4/7 3/7 2/4 2/3 3/4 1/3 3/4 2/3 11

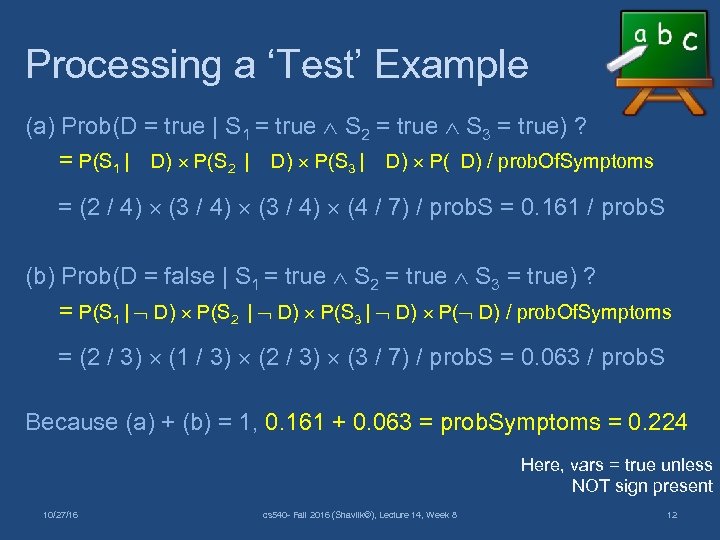

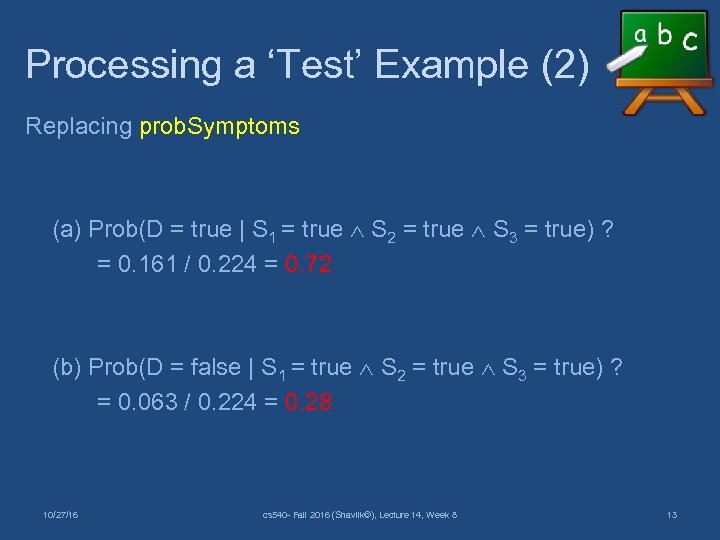

Processing a ‘Test’ Example (a) Prob(D = true | S 1 = true S 2 = true S 3 = true) ? = P(S 1 | D) P(S 2 | D) P(S 3 | D) P( D) / prob. Of. Symptoms = (2 / 4) (3 / 4) (4 / 7) / prob. S = 0. 161 / prob. S (b) Prob(D = false | S 1 = true S 2 = true S 3 = true) ? = P(S 1 | D) P(S 2 | D) P(S 3 | D) P( D) / prob. Of. Symptoms = (2 / 3) (1 / 3) (2 / 3) (3 / 7) / prob. S = 0. 063 / prob. S Because (a) + (b) = 1, 0. 161 + 0. 063 = prob. Symptoms = 0. 224 Here, vars = true unless NOT sign present 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 12

Processing a ‘Test’ Example (2) Replacing prob. Symptoms (a) Prob(D = true | S 1 = true S 2 = true S 3 = true) ? = 0. 161 / 0. 224 = 0. 72 (b) Prob(D = false | S 1 = true S 2 = true S 3 = true) ? = 0. 063 / 0. 224 = 0. 28 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 13

Is NB Naïve? Surprisingly, the assumption of independence, while most likely violated, is not too harmful! • Naïve Bayes works quite well – Very successful in text categorization (‘bag-o- words’ rep) – Used in printer diagnosis in Windows, spam filtering, etc • Prob’s not accurate (‘uncalibrated’) due to double counting, but good at seeing if prob > 0. 5 or prob < 0. 5 • Resurgence of research activity in Naïve Bayes – Many ‘dead’ ML algo’s resuscitated by availability of large datasets (KISS Principle) 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 14

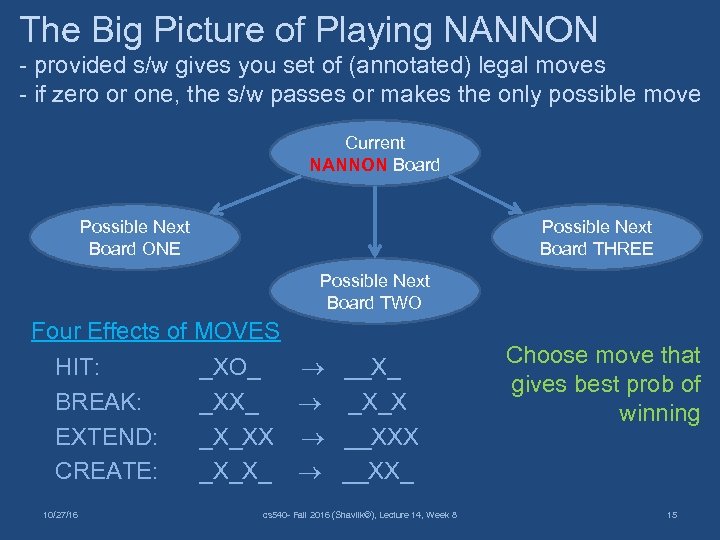

The Big Picture of Playing NANNON - provided s/w gives you set of (annotated) legal moves - if zero or one, the s/w passes or makes the only possible move Current NANNON Board Possible Next Board ONE Possible Next Board THREE Possible Next Board TWO Four Effects of MOVES HIT: _XO_ BREAK: _XX_ EXTEND: _X_XX CREATE: _X_X_ 10/27/16 __X_ _X_X __XX_ cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 Choose move that gives best prob of winning 15

Reinforcement Learning (RL) vs. Supervised Learning • Nannon is Really an RL Task • We’ll Treat as a SUPERVISED ML Task – All moves in winning games considered GOOD – All moves in losing games considered BAD • Noisy Data, but Good Play Still Results • ‘Random Move’ & Hand-Coded Players Provided • Provided Code can make 106 Moves/Sec 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 16

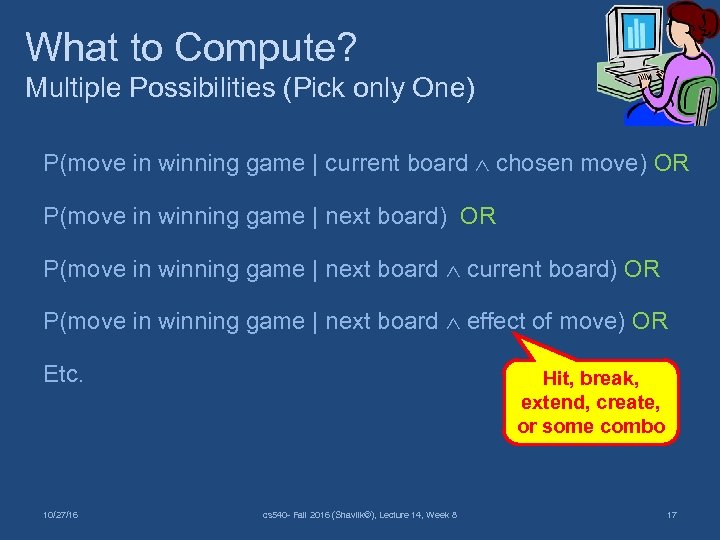

What to Compute? Multiple Possibilities (Pick only One) P(move in winning game | current board chosen move) OR P(move in winning game | next board current board) OR P(move in winning game | next board effect of move) OR Etc. 10/27/16 Hit, break, extend, create, or some combo cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 17

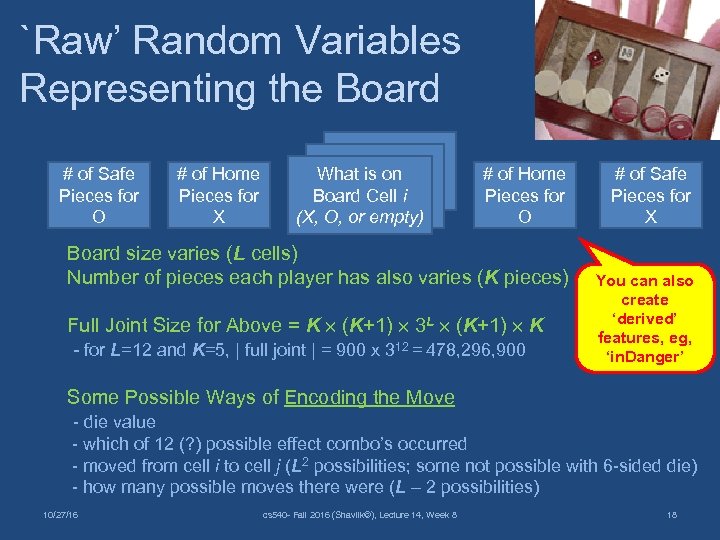

`Raw’ Random Variables Representing the Board # of Safe Pieces for O # of Home Pieces for X What is on Board Cell i (X, O, or empty) # of Home Pieces for O Board size varies (L cells) Number of pieces each player has also varies (K pieces) Full Joint Size for Above = K (K+1) 3 L (K+1) K - for L=12 and K=5, | full joint | = 900 x 312 = 478, 296, 900 # of Safe Pieces for X You can also create ‘derived’ features, eg, ‘in. Danger’ Some Possible Ways of Encoding the Move - die value - which of 12 (? ) possible effect combo’s occurred - moved from cell i to cell j (L 2 possibilities; some not possible with 6 -sided die) - how many possible moves there were (L – 2 possibilities) 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 18

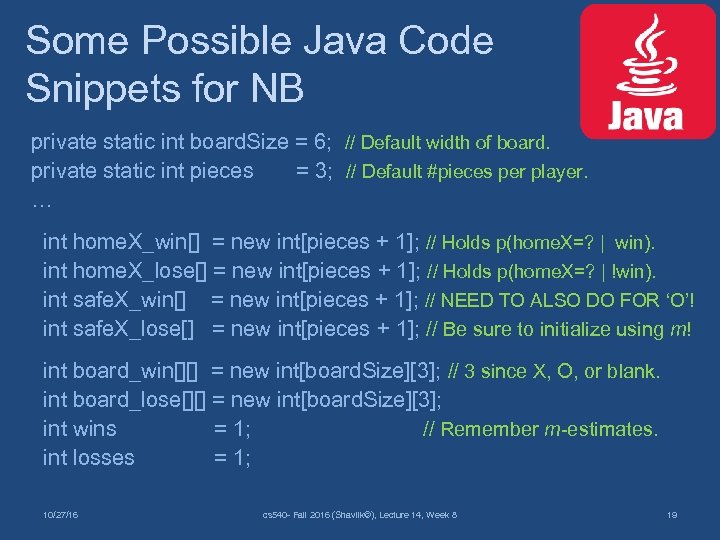

Some Possible Java Code Snippets for NB private static int board. Size = 6; // Default width of board. private static int pieces = 3; // Default #pieces per player. … int home. X_win[] = new int[pieces + 1]; // Holds p(home. X=? | win). int home. X_lose[] = new int[pieces + 1]; // Holds p(home. X=? | !win). int safe. X_win[] = new int[pieces + 1]; // NEED TO ALSO DO FOR ‘O’! int safe. X_lose[] = new int[pieces + 1]; // Be sure to initialize using m! int board_win[][] = new int[board. Size][3]; // 3 since X, O, or blank. int board_lose[][] = new int[board. Size][3]; int wins = 1; // Remember m-estimates. int losses = 1; 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 19

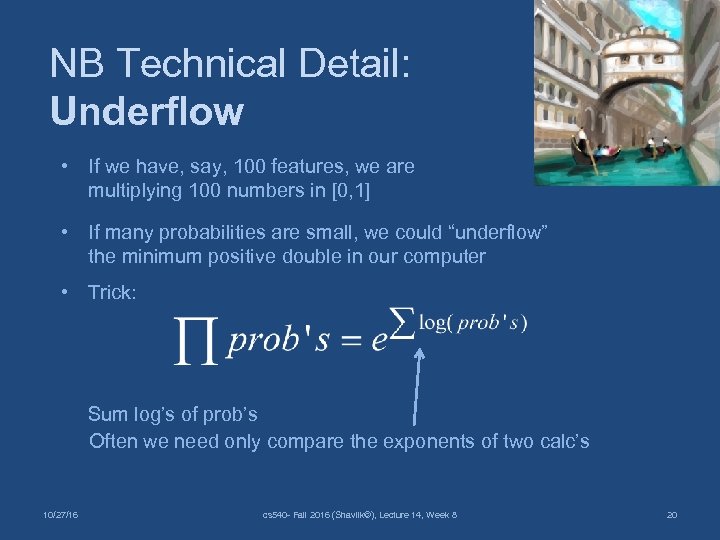

NB Technical Detail: Underflow • If we have, say, 100 features, we are multiplying 100 numbers in [0, 1] • If many probabilities are small, we could “underflow” the minimum positive double in our computer • Trick: Sum log’s of prob’s Often we need only compare the exponents of two calc’s 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 20

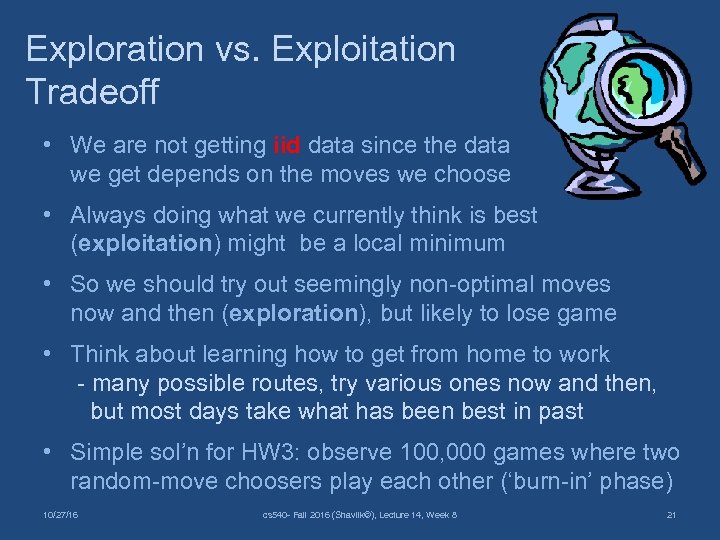

Exploration vs. Exploitation Tradeoff • We are not getting iid data since the data we get depends on the moves we choose • Always doing what we currently think is best (exploitation) might be a local minimum • So we should try out seemingly non-optimal moves now and then (exploration), but likely to lose game • Think about learning how to get from home to work - many possible routes, try various ones now and then, but most days take what has been best in past • Simple sol’n for HW 3: observe 100, 000 games where two random-move choosers play each other (‘burn-in’ phase) 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 21

Stationarity • What About the Fact Opponent also Learns? • That Changes the Probability Distributions We are Trying to Estimate! • However, We’ll Assume that the Prob Distribution Remains Unchanged (ie, is Stationary) While We Learn 10/27/16 cs 540 - Fall 2016 (Shavlik©), Lecture 14, Week 8 22

6f8b8a8d886bdbecd92fd32de242ef6f.ppt