b57474f947f9e9675e780ceeb469e7f7.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 29

This online version does not include the movies. Please e-mail dcr@astro. umd. edu if you want them. Rubble Piles & Monoliths Derek C. Richardson (U Maryland) Preshattered Rubble CD-VI Cannes

This online version does not include the movies. Please e-mail dcr@astro. umd. edu if you want them. Rubble Piles & Monoliths Derek C. Richardson (U Maryland) Preshattered Rubble CD-VI Cannes

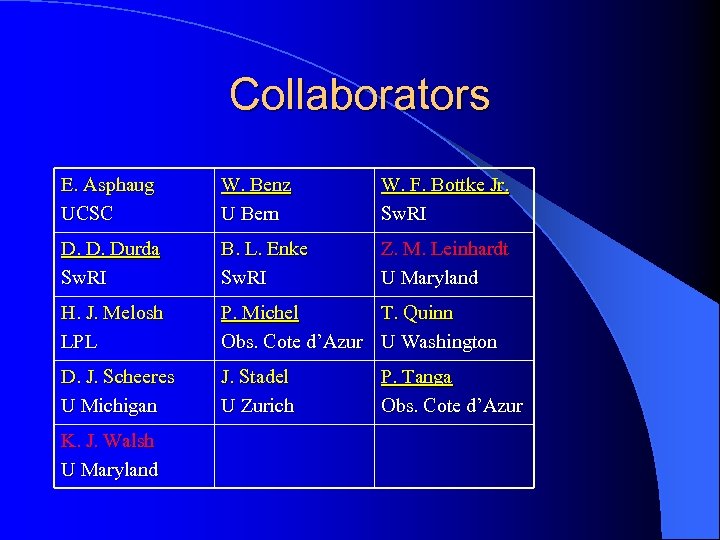

Collaborators E. Asphaug UCSC W. Benz U Bern W. F. Bottke Jr. Sw. RI D. D. Durda Sw. RI B. L. Enke Sw. RI Z. M. Leinhardt U Maryland H. J. Melosh LPL P. Michel T. Quinn Obs. Cote d’Azur U Washington D. J. Scheeres U Michigan J. Stadel U Zurich K. J. Walsh U Maryland P. Tanga Obs. Cote d’Azur

Collaborators E. Asphaug UCSC W. Benz U Bern W. F. Bottke Jr. Sw. RI D. D. Durda Sw. RI B. L. Enke Sw. RI Z. M. Leinhardt U Maryland H. J. Melosh LPL P. Michel T. Quinn Obs. Cote d’Azur U Washington D. J. Scheeres U Michigan J. Stadel U Zurich K. J. Walsh U Maryland P. Tanga Obs. Cote d’Azur

Overview l Gravitational Aggregates – What are they? Do they exist? l Numerical Simulations – How do they work? l Gravitational Reaccumulation (Rubble Piles) – Families & Binaries, Collisions & Tidal Disruption l Pushing the Envelope (Monoliths!) – More realism without sacrificing too much speed. Cf. Richardson et al. 2003: Asteroids III

Overview l Gravitational Aggregates – What are they? Do they exist? l Numerical Simulations – How do they work? l Gravitational Reaccumulation (Rubble Piles) – Families & Binaries, Collisions & Tidal Disruption l Pushing the Envelope (Monoliths!) – More realism without sacrificing too much speed. Cf. Richardson et al. 2003: Asteroids III

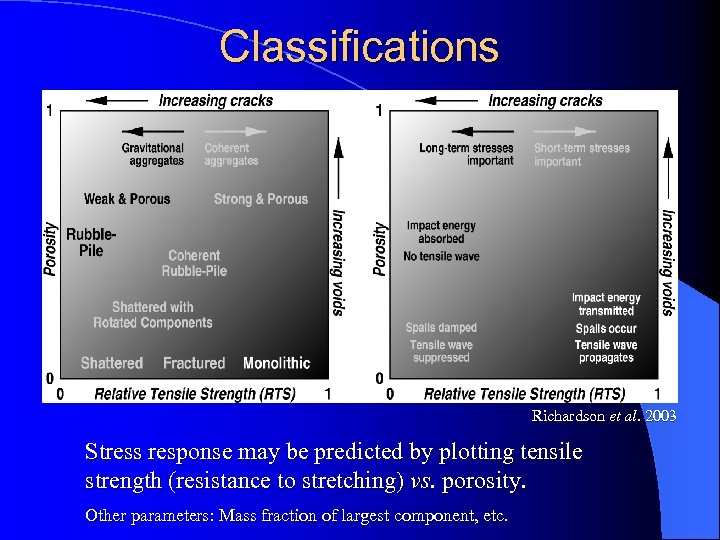

Classifications Richardson et al. 2003 Stress response may be predicted by plotting tensile strength (resistance to stretching) vs. porosity. Other parameters: Mass fraction of largest component, etc.

Classifications Richardson et al. 2003 Stress response may be predicted by plotting tensile strength (resistance to stretching) vs. porosity. Other parameters: Mass fraction of largest component, etc.

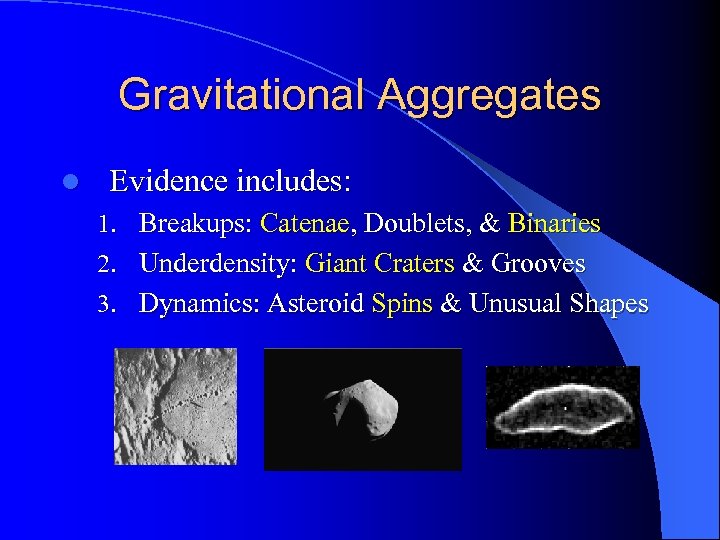

Gravitational Aggregates l Evidence includes: 1. Breakups: Catenae, Doublets, & Binaries 2. Underdensity: Giant Craters & Grooves 3. Dynamics: Asteroid Spins & Unusual Shapes

Gravitational Aggregates l Evidence includes: 1. Breakups: Catenae, Doublets, & Binaries 2. Underdensity: Giant Craters & Grooves 3. Dynamics: Asteroid Spins & Unusual Shapes

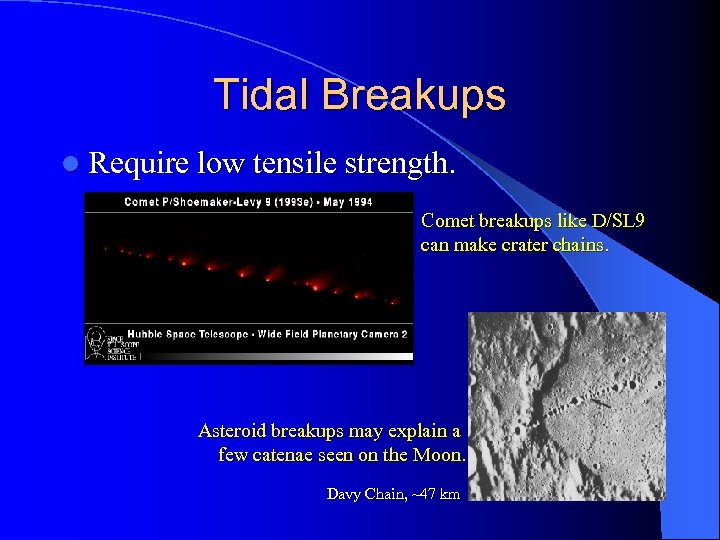

Tidal Breakups l Require low tensile strength. Comet breakups like D/SL 9 can make crater chains. Asteroid breakups may explain a few catenae seen on the Moon. Davy Chain, ~47 km

Tidal Breakups l Require low tensile strength. Comet breakups like D/SL 9 can make crater chains. Asteroid breakups may explain a few catenae seen on the Moon. Davy Chain, ~47 km

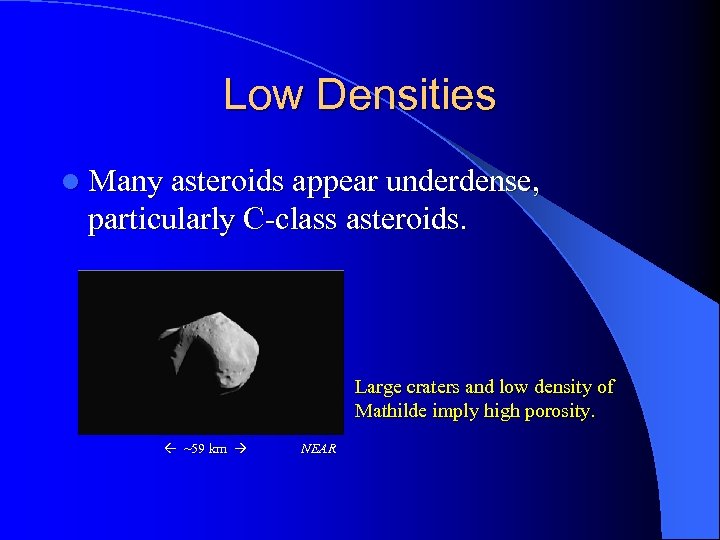

Low Densities l Many asteroids appear underdense, particularly C-class asteroids. Large craters and low density of Mathilde imply high porosity. ~59 km NEAR

Low Densities l Many asteroids appear underdense, particularly C-class asteroids. Large craters and low density of Mathilde imply high porosity. ~59 km NEAR

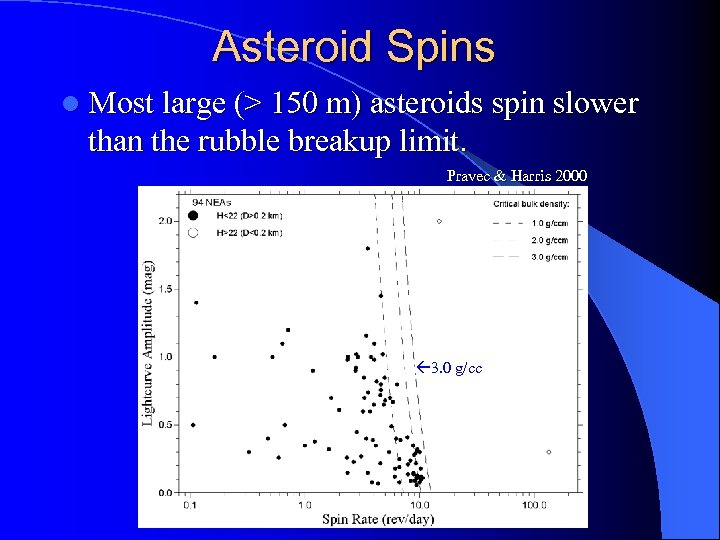

Asteroid Spins l Most large (> 150 m) asteroids spin slower than the rubble breakup limit. Pravec & Harris 2000 3. 0 g/cc

Asteroid Spins l Most large (> 150 m) asteroids spin slower than the rubble breakup limit. Pravec & Harris 2000 3. 0 g/cc

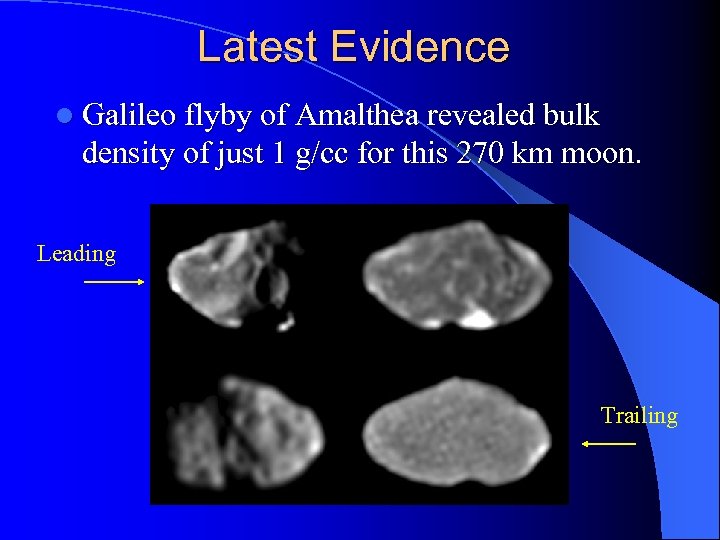

Latest Evidence l Galileo flyby of Amalthea revealed bulk density of just 1 g/cc for this 270 km moon. Leading Trailing

Latest Evidence l Galileo flyby of Amalthea revealed bulk density of just 1 g/cc for this 270 km moon. Leading Trailing

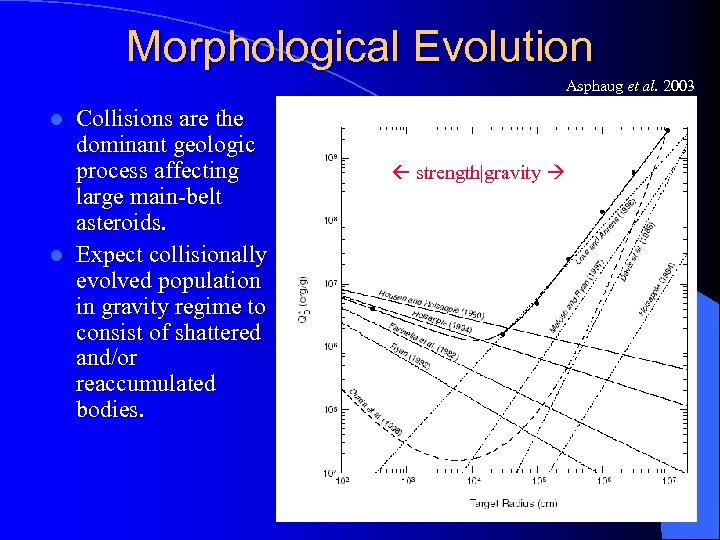

Morphological Evolution Asphaug et al. 2003 Collisions are the dominant geologic process affecting large main-belt asteroids. l Expect collisionally evolved population in gravity regime to consist of shattered and/or reaccumulated bodies. l strength|gravity

Morphological Evolution Asphaug et al. 2003 Collisions are the dominant geologic process affecting large main-belt asteroids. l Expect collisionally evolved population in gravity regime to consist of shattered and/or reaccumulated bodies. l strength|gravity

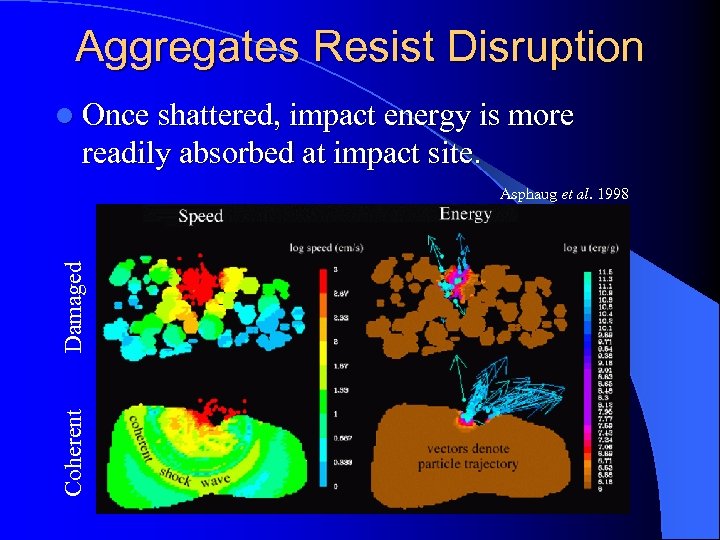

Aggregates Resist Disruption l Once shattered, impact energy is more readily absorbed at impact site. Coherent Damaged Asphaug et al. 1998

Aggregates Resist Disruption l Once shattered, impact energy is more readily absorbed at impact site. Coherent Damaged Asphaug et al. 1998

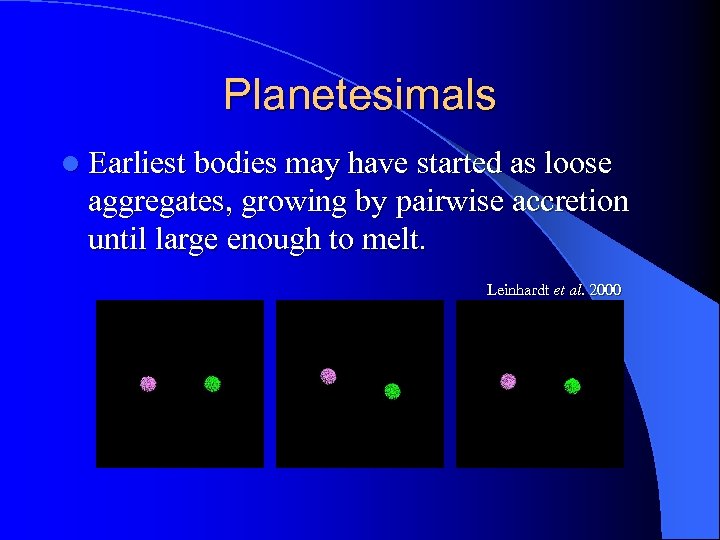

Planetesimals l Earliest bodies may have started as loose aggregates, growing by pairwise accretion until large enough to melt. Leinhardt et al. 2000

Planetesimals l Earliest bodies may have started as loose aggregates, growing by pairwise accretion until large enough to melt. Leinhardt et al. 2000

Numerical Simulations l Gravitational aggregate dynamics can be explored with fast N-body code: pkdgrav. – Model bodies as rubble piles: collections of indestructible spherical particles. – Particle motions evolve via collisions and gravity. – Collisions may be dissipative and may alter particle spins via surface friction. – Gravity may include external perturbations.

Numerical Simulations l Gravitational aggregate dynamics can be explored with fast N-body code: pkdgrav. – Model bodies as rubble piles: collections of indestructible spherical particles. – Particle motions evolve via collisions and gravity. – Collisions may be dissipative and may alter particle spins via surface friction. – Gravity may include external perturbations.

Numerical Method l Use hierarchical treecode and highly parallelized algorithms to improve speed. l Solve Newton’s laws using leapfrog integrator (multistepping optional). – Timestep small fraction of dynamical time. l Predict collisions during drift interval and resolve using restitution model. l Repeat for many dynamical times.

Numerical Method l Use hierarchical treecode and highly parallelized algorithms to improve speed. l Solve Newton’s laws using leapfrog integrator (multistepping optional). – Timestep small fraction of dynamical time. l Predict collisions during drift interval and resolve using restitution model. l Repeat for many dynamical times.

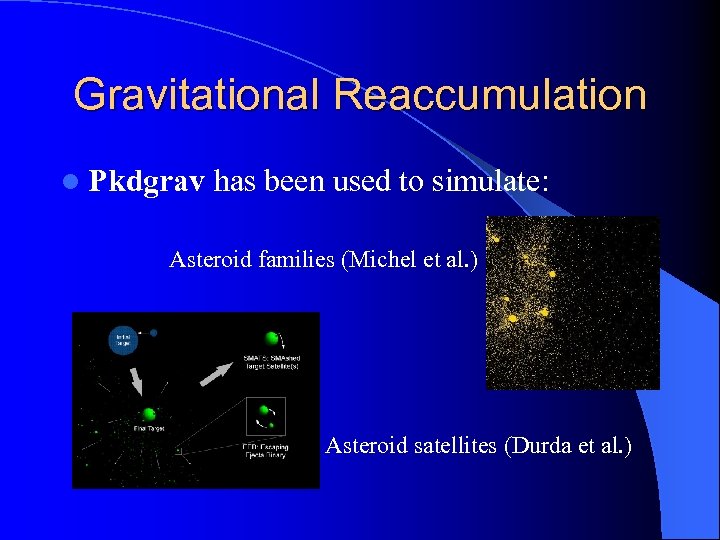

Gravitational Reaccumulation l Pkdgrav has been used to simulate: Asteroid families (Michel et al. ) Asteroid satellites (Durda et al. )

Gravitational Reaccumulation l Pkdgrav has been used to simulate: Asteroid families (Michel et al. ) Asteroid satellites (Durda et al. )

NEA Binaries l High frequency of occurrence, fast rotating primaries, and terrestrial doublet crater population suggest tidal disruption may be an important mechanism forming NEA binaries.

NEA Binaries l High frequency of occurrence, fast rotating primaries, and terrestrial doublet crater population suggest tidal disruption may be an important mechanism forming NEA binaries.

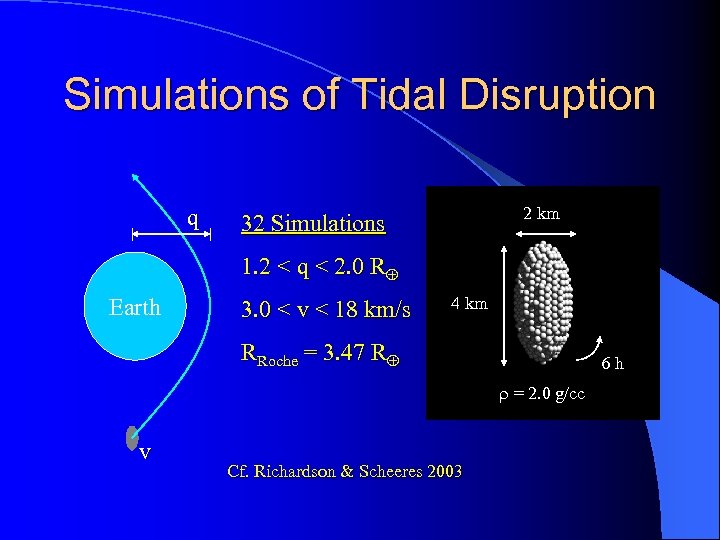

Simulations of Tidal Disruption q 2 km 32 Simulations 1. 2 < q < 2. 0 R Earth 3. 0 < v < 18 km/s 4 km RRoche = 3. 47 R 6 h = 2. 0 g/cc v Cf. Richardson & Scheeres 2003

Simulations of Tidal Disruption q 2 km 32 Simulations 1. 2 < q < 2. 0 R Earth 3. 0 < v < 18 km/s 4 km RRoche = 3. 47 R 6 h = 2. 0 g/cc v Cf. Richardson & Scheeres 2003

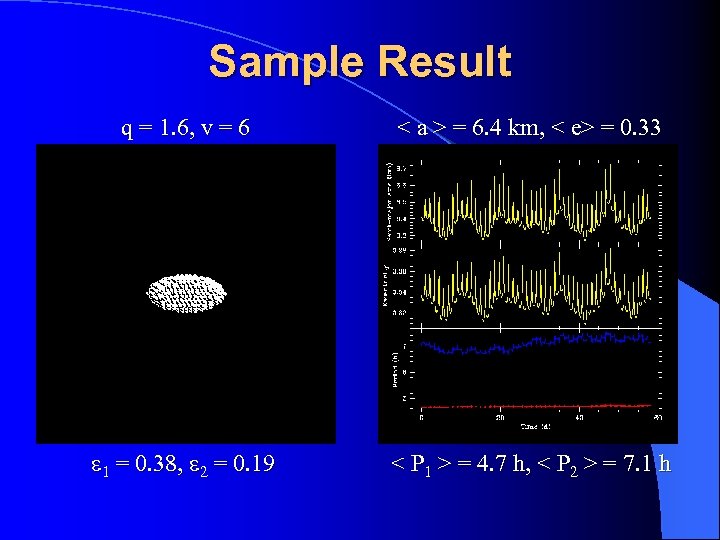

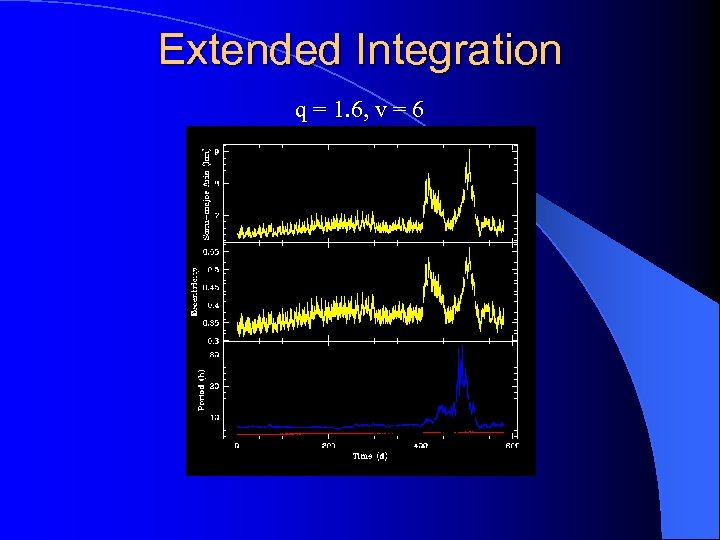

Sample Result q = 1. 6, v = 6 < a > = 6. 4 km, < e> = 0. 33 1 = 0. 38, 2 = 0. 19 < P 1 > = 4. 7 h, < P 2 > = 7. 1 h

Sample Result q = 1. 6, v = 6 < a > = 6. 4 km, < e> = 0. 33 1 = 0. 38, 2 = 0. 19 < P 1 > = 4. 7 h, < P 2 > = 7. 1 h

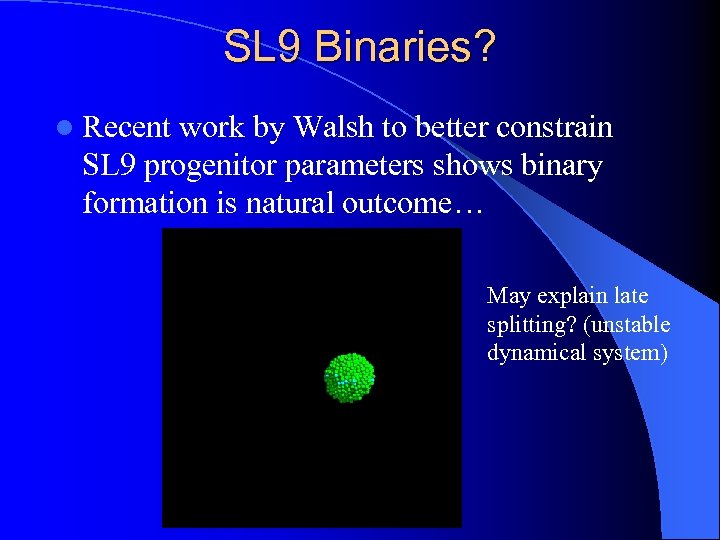

SL 9 Binaries? l Recent work by Walsh to better constrain SL 9 progenitor parameters shows binary formation is natural outcome… May explain late splitting? (unstable dynamical system)

SL 9 Binaries? l Recent work by Walsh to better constrain SL 9 progenitor parameters shows binary formation is natural outcome… May explain late splitting? (unstable dynamical system)

Pushing the Envelope l Current large-scale simulations by Michel & Durda oversimplify reaccumulation process by assuming perfect merging. – Reduces cost of particle collision computation in rubble piles. – BUT: spins, shapes, and gravity fields of reaccumulated bodies unrealistic.

Pushing the Envelope l Current large-scale simulations by Michel & Durda oversimplify reaccumulation process by assuming perfect merging. – Reduces cost of particle collision computation in rubble piles. – BUT: spins, shapes, and gravity fields of reaccumulated bodies unrealistic.

New Strategy l Reduce computation cost by freezing the rubble pile particles into coherent (rigid) aggregates, i. e. (porous) monoliths! – Requires diagonalization of inertia tensors and computation of gravitational & collisional torques, but still much cheaper! – Also need speed-dependent sticking/breaking criteria new model parameters to be tuned.

New Strategy l Reduce computation cost by freezing the rubble pile particles into coherent (rigid) aggregates, i. e. (porous) monoliths! – Requires diagonalization of inertia tensors and computation of gravitational & collisional torques, but still much cheaper! – Also need speed-dependent sticking/breaking criteria new model parameters to be tuned.

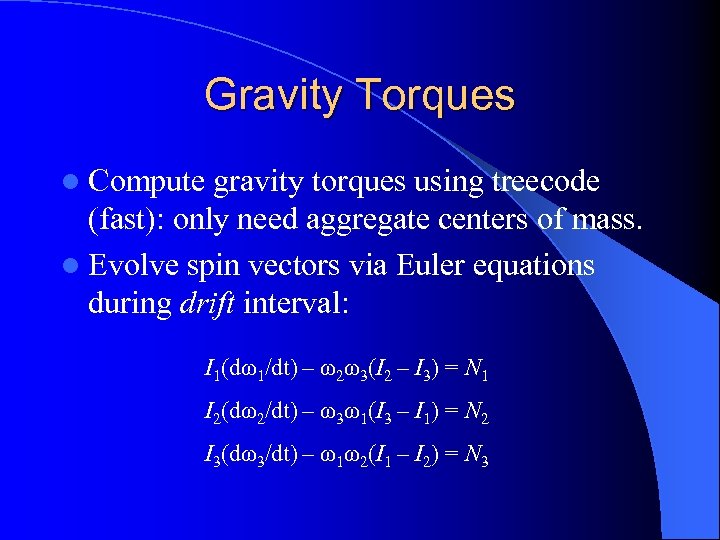

Gravity Torques l Compute gravity torques using treecode (fast): only need aggregate centers of mass. l Evolve spin vectors via Euler equations during drift interval: I 1(dω1/dt) – ω2ω3(I 2 – I 3) = N 1 I 2(dω2/dt) – ω3ω1(I 3 – I 1) = N 2 I 3(dω3/dt) – ω1ω2(I 1 – I 2) = N 3

Gravity Torques l Compute gravity torques using treecode (fast): only need aggregate centers of mass. l Evolve spin vectors via Euler equations during drift interval: I 1(dω1/dt) – ω2ω3(I 2 – I 3) = N 1 I 2(dω2/dt) – ω3ω1(I 3 – I 1) = N 2 I 3(dω3/dt) – ω1ω2(I 1 – I 2) = N 3

Collision Torques l Collisions now oblique (non-central), requiring more sophisticated approach. l Case of point-contact, instantaneous impacts with no surface friction has been solved: see Richardson 1995 for equations. – Straightforward to compute since constituent particles still just spheres.

Collision Torques l Collisions now oblique (non-central), requiring more sophisticated approach. l Case of point-contact, instantaneous impacts with no surface friction has been solved: see Richardson 1995 for equations. – Straightforward to compute since constituent particles still just spheres.

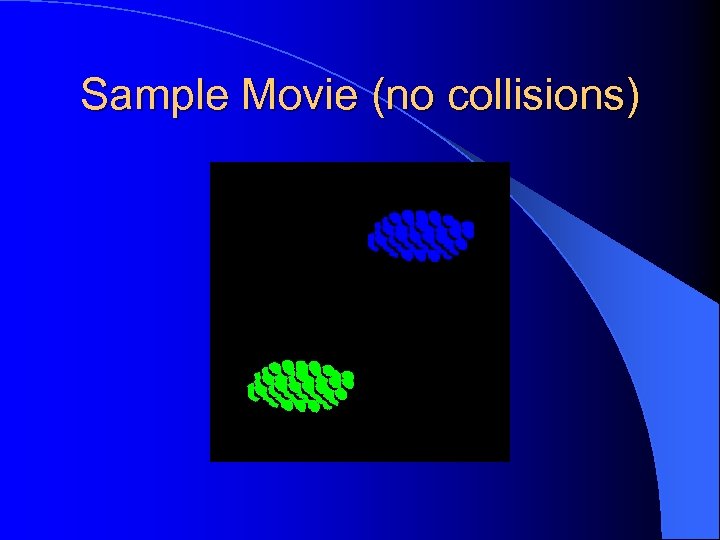

Sample Movie (no collisions)

Sample Movie (no collisions)

Extended Integration q = 1. 6, v = 6

Extended Integration q = 1. 6, v = 6

Sample Movie (sticking only)

Sample Movie (sticking only)

Summary l Many (most? ) small bodies in the Solar System may be gravitational aggregates. l Asteroid families and clusters can be explained by gravitational reaccumulation of debris after a high-speed impact. l Collisions and tidal disruption play a key role in forming asteroid binaries.

Summary l Many (most? ) small bodies in the Solar System may be gravitational aggregates. l Asteroid families and clusters can be explained by gravitational reaccumulation of debris after a high-speed impact. l Collisions and tidal disruption play a key role in forming asteroid binaries.

Future Work l Add bouncing to rigid body treatment to enable compaction (next week!). l Trace evolution of individual particles from breakup to reaccumulation. l Study binary formation via YORP spinup. l Consider application to slow and tumbling rotators.

Future Work l Add bouncing to rigid body treatment to enable compaction (next week!). l Trace evolution of individual particles from breakup to reaccumulation. l Study binary formation via YORP spinup. l Consider application to slow and tumbling rotators.

THE END

THE END