88a2ed6b6ee59be7f26b8a3e8486f00f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 50

Thermal Burns Todd Ring Nov. 27/03

You will know… l Types, severity, and extent of thermal burns l Pre-hospital management goals l Smoke inhalation injury and treatment l Evidence behind the Parkland formula and fluid resuscitation goals l Treatment of major and minor burn wounds l Issues regarding burns in the pediatric and pregnant patient

Case 1: Mr. Crispy A 55 yo. male is brought into the ED after lighting himself on fire. He has sustained burns to his face, anterior thorax and anterior aspect of his right arm and leg. The burns on his face are red with blisters while those on his trunk and extremities are white. l What features distinguish the depth of the burn? l What percentage of his body has been burned? l Does this patient require admission to a burn unit?

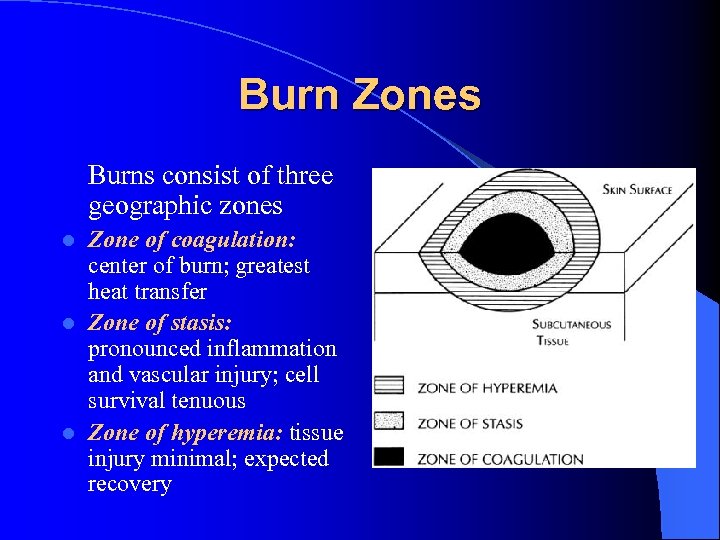

Burn Zones Burns consist of three geographic zones Zone of coagulation: center of burn; greatest heat transfer l Zone of stasis: pronounced inflammation and vascular injury; cell survival tenuous l Zone of hyperemia: tissue injury minimal; expected recovery l

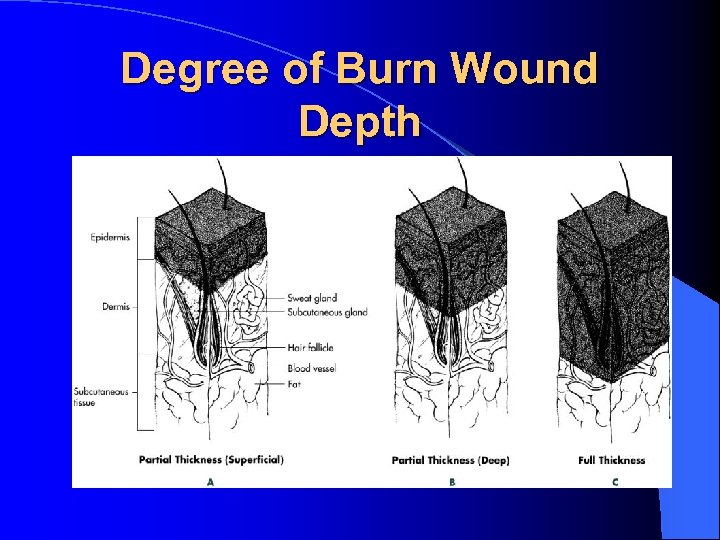

Burn Classification Assessment should include an assessment of depth and total body surface area (TBSA) burned l First degree burn: involves epidermal layer of the skin but not dermis; characterized by pain, erythema and lack blisters; generally heals without scar; not considered in TBSA l Second degree burn: divided into superficial and deep partial thickness Superficial partial thickness burn involves the papillary dermis; painful; blisters are present or may develop; heal over 2 -3 weeks with no scar l

Burn Classification Deep partial thickness burn damages both papillary and reticular dermis plus deeper sweat glands and follicles; may or may not be painful; 3 or more weeks to heal and often will scar l Third degree or full thickness: involve all layers and may destroy subcutaneous tissue; white or charred; insensate; require skin grafting l Fourth degree: involve structures below the subcutaneous fat including muscle and bone

Degree of Burn Wound Depth

Burn Shock l Severe burn injury results in a physiologic response throughout the body to increase capillary permeability third spacing of fluid in tissues surrounding burn l Damaged skin also no longer able to retain H 2 O and consequently large evaporative losses l Combination results in hypovolumeic shock

Metabolic Complications l Directly related to extent of burn l Initial ebb phase with decreased CO and metabolic rate (MR) l Followed by flow phase with increased MR and core temp reset to 38. 5 C

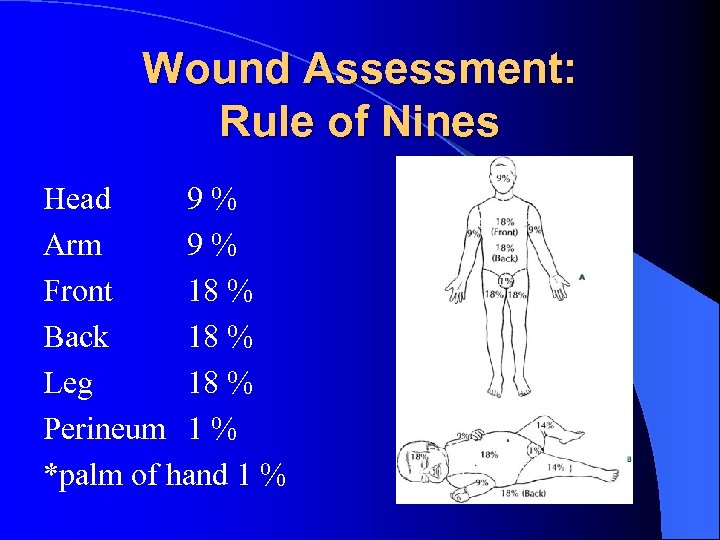

Wound Assessment: Rule of Nines Head 9% Arm 9% Front 18 % Back 18 % Leg 18 % Perineum 1 % *palm of hand 1 %

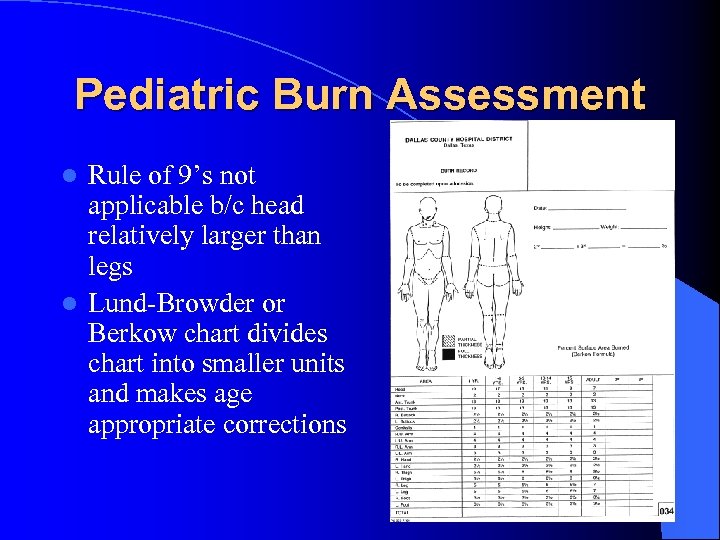

Pediatric Burn Assessment Rule of 9’s not applicable b/c head relatively larger than legs l Lund-Browder or Berkow chart divides chart into smaller units and makes age appropriate corrections l

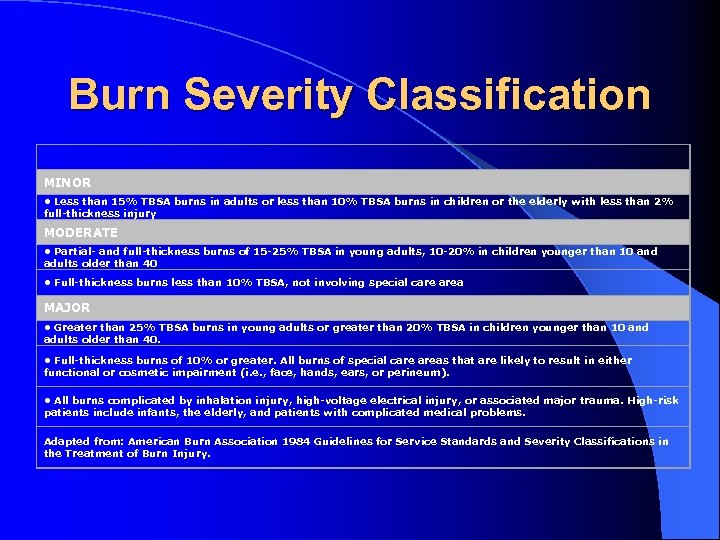

Burn Severity Classification MINOR • Less than 15% TBSA burns in adults or less than 10% TBSA burns in children or the elderly with less than 2% full-thickness injury MODERATE • Partial- and full-thickness burns of 15 -25% TBSA in young adults, 10 -20% in children younger than 10 and adults older than 40 • Full-thickness burns less than 10% TBSA, not involving special care area MAJOR • Greater than 25% TBSA burns in young adults or greater than 20% TBSA in children younger than 10 and adults older than 40. • Full-thickness burns of 10% or greater. All burns of special care areas that are likely to result in either functional or cosmetic impairment (i. e. , face, hands, ears, or perineum). • All burns complicated by inhalation injury, high-voltage electrical injury, or associated major trauma. High-risk patients include infants, the elderly, and patients with complicated medical problems. Adapted from: American Burn Association 1984 Guidelines for Service Standards and Severity Classifications in the Treatment of Burn Injury.

Pre-hospital Management Typical measures including primary and secondary survey, initial stabilization (i. e. . c-spine, splinting other injuries) l High flow O 2 or intubation if inhalation injury suspected l Removal of burned clothing and jewelry l Small burns should be covered with wet dressing as decrease pain and thermal injury if initiated in 1 st 40 min l

Pre-hospital Management Large burns (> 20 %TBSA) should be covered with clean dry dressings b/c risk of hypothermia l IV should be initiated if it doesn’t delay transport l – Adult and adolescent 500 cc/hr RL – Child (5 – 15) 250 cc/hr – < 5 yrs do not attempt IV as may prevent transport delay (as per burn life support protocol)

Case 2: Mr. C. O. A 33 yo male is involved in a confined gas plant explosion. EMS patches in that the patient has extensive burns on his face and neck and is stridourous. His O 2 sat is 98 %. l What features on history and physical exam suggest an inhalational injury l How would you manage this patients airway? l Why may the O 2 sat be unreliable?

Inhalation Injury Smoke inhalation accounts for more than 50% of fire-related deaths l Most injuries occur from inhalation of smoke but rarely superheated air produces direct thermal injury (especially steam) l Three phases of acute smoke inhalation: l – 1 st 36 hours: acute pulmonary insufficiency – 2 – 5 days: post resuscitation – > 5 days: post injury period l Smoke inhalation is a combination of direct pulmonary injury and systemic and metabolic toxicity

Smoke Lung Injury Depends on fuels, intensity, duration, confinement l Unless steam, direct heat injury to airway is supraglottic l – Obvious concern re: obstructive edema, thermal trachetitis, hemorrhagic edema of bronchi Gas phase constituents of smoke include CO, cyanide, acid and aldehyde gases, oxidants l Direct damage to muco-ciliary elevator, bronchial vessel permeability, alveolar destruction and secondary mucous and edema l

Clinical Assessment l History of explosion or trapped in building l Physical examination demonstrates facial burns, singed eyebrows or nasal hair, pharyngeal burn, carbonaceous sputum or impaired mentation l Changes in voice, stridour or wheeze alarming

Management l Natural history of upper airway burn is edema that narrows the airway over 12 – 24 h – Intubation recommended in patients with stridour, wheeze, voice changes Serial bronchoscopy option in stable patient or to assist in intubation l Burns to the neck can result in tight eschar formation that combined with pharyngeal edema pulmonary insuff. l Neck escharotomy: vertical incision from sternal notch to chin l

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning l l l CO much higher affinity for Hgb than O 2 Pulse oximetry overestimates hemoglobin O 2 saturation ABG measurement for carboxyhemoglobin value Patients exposed to CO should receive 100% O 2 by nonrebreather (CO ½ life decreased from 240 – 60 minutes HBO therapy if CO level >25 %, myocardial ischemia, dysrhythmia; CO level > 15 % in pregnant women or young child

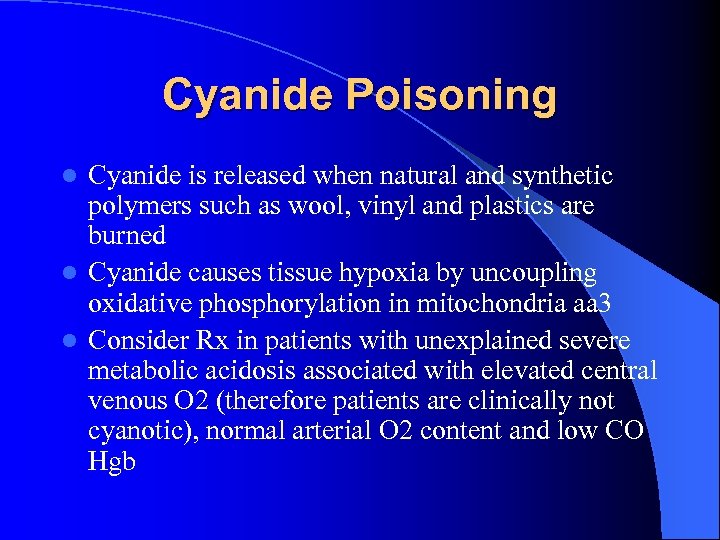

Cyanide Poisoning Cyanide is released when natural and synthetic polymers such as wool, vinyl and plastics are burned l Cyanide causes tissue hypoxia by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria aa 3 l Consider Rx in patients with unexplained severe metabolic acidosis associated with elevated central venous O 2 (therefore patients are clinically not cyanotic), normal arterial O 2 content and low CO Hgb l

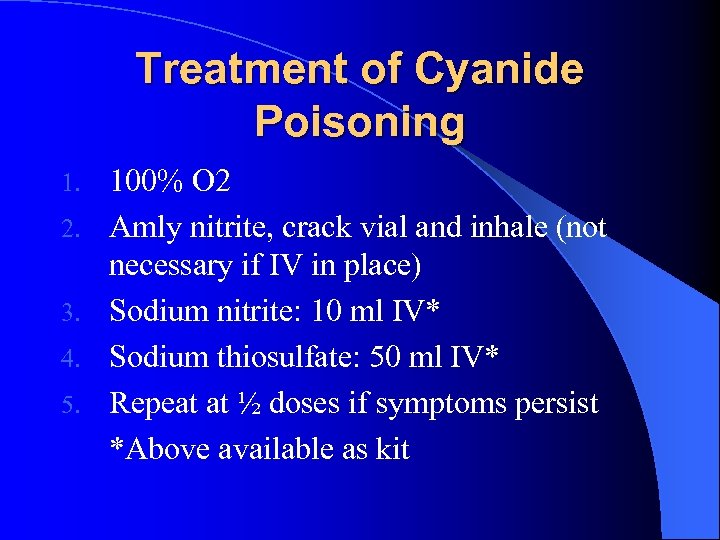

Treatment of Cyanide Poisoning 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 100% O 2 Amly nitrite, crack vial and inhale (not necessary if IV in place) Sodium nitrite: 10 ml IV* Sodium thiosulfate: 50 ml IV* Repeat at ½ doses if symptoms persist *Above available as kit

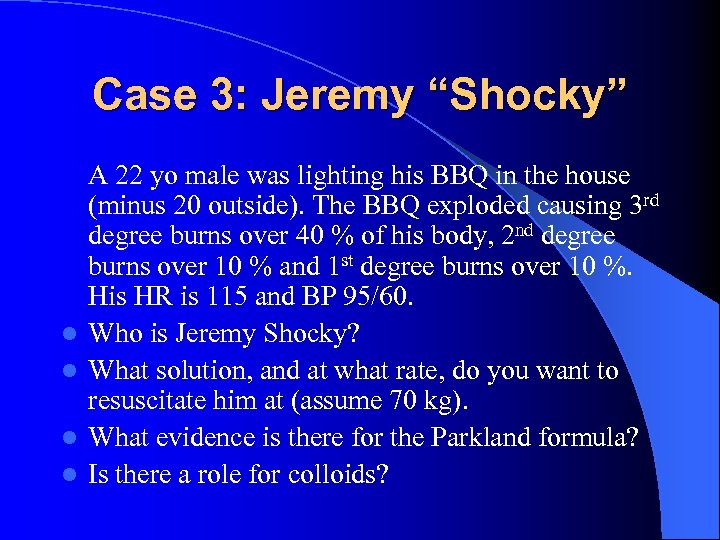

Case 3: Jeremy “Shocky” l l A 22 yo male was lighting his BBQ in the house (minus 20 outside). The BBQ exploded causing 3 rd degree burns over 40 % of his body, 2 nd degree burns over 10 % and 1 st degree burns over 10 %. His HR is 115 and BP 95/60. Who is Jeremy Shocky? What solution, and at what rate, do you want to resuscitate him at (assume 70 kg). What evidence is there for the Parkland formula? Is there a role for colloids?

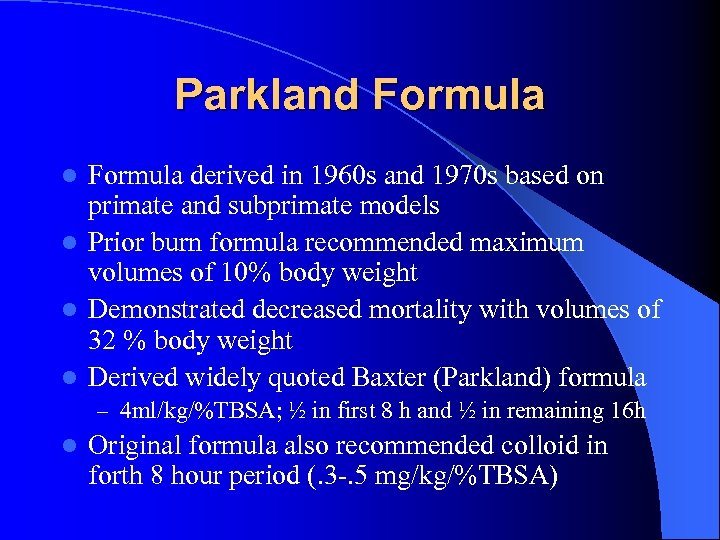

Parkland Formula derived in 1960 s and 1970 s based on primate and subprimate models l Prior burn formula recommended maximum volumes of 10% body weight l Demonstrated decreased mortality with volumes of 32 % body weight l Derived widely quoted Baxter (Parkland) formula l – 4 ml/kg/%TBSA; ½ in first 8 h and ½ in remaining 16 h l Original formula also recommended colloid in forth 8 hour period (. 3 -. 5 mg/kg/%TBSA)

Resuscitation Volume l Situations in which more fluid required – Inhalation injury, associated mechanical or electrical trauma, large burns with delay in initiating treatment Baxter recommended monitoring MAP (>70) and u/o (. 5 -1 ml/kg/hr) l Invasive monitoring (PA cath) rarely used in burn patients l – 8 % of burn units with burns >30% TBSA from 250 burn units used PA caths in > 50% of patients – Only few centers use data from PA cath to direct Rx Mansfield et al. Burns. 1996; 22: 549 -51

Resuscitation Volume l Well known that BP, HR, and u/o have poor correlation with invasive measurements – Compensated shock can give relatively normal parameter but ongoing tissue damage l Majority of studies using invasive monitoring have reported significantly higher volumes (4. 5 – 9. 2 ml/kg/TBSA/24 h) Holm et. al. Resuscitation 2000; 44: 157 -64 l No RTC’s comparing Baxter formula to invasive monitoring

Resuscitation Volume l Schriller et al. in a non-prospective, nonrandomized study compared survival rate using standard vitals vs. invasive monitoring – Survival rate 48% PA cath vs. 32% standard l It seems that many burn centers which are using MAP and u. o as goals are already exceeding Baxter formula – Kemalyan et al. demonstrated rates 40 – 80 % more at 7 burn centers using u/o to direct resuscitation l No evidence to support claim that aggressive resuscitation results in cardiopulmonary overload

Colloid vs. Crystalloid Theoretical advantage of colloid administration keeping fluid intravascualar l Baxter recommended delayed (>12 – 24 h post injury) administration because of increased pulmonary permeability early on however recent studies do not support this claim l Cochrane collaboration conducted a review on the use of albumin in burns l – 1419 patients; 30 RTCs – Increased mortality in albumin group (NNH 17) – ? Secondary to coagulation effect of albumin l Despite Cochrane findings many burn centers still advocate use of colloid

Conclusion on Fluid Resuscitation l l l Fluid Resuscitation is essential Immediate resuscitation advocated Despite 3 decades since Baxter developed original formula still no conclusive evidence re: what kind of fluid; when to give; and how much Parkland formula tends to underestimate resuscitation volumes Some evidence to support invasive monitoring

Pain Control Pain requirements inversely proportional to depth of burn l Full thickness burns are painless because sensory nerves damaged l Partial thickness burns have intact nerves and are extremely painful l Morphine advocated for pain management l – Low protein binding – Metabolized by liver and excreted in urine l Rapid elimination may result in doses > 50 mg/h

GI/GU Complications l Foley catheter should be placed to monitor fluid resuscitation l Perineal burns should also have foley placed to decrease urinary soilage l Gastric ileus is common involving burns more than 20 %; NG tube should be placed l Gastric ulcers may occur in patients with severe burns; GI prophylaxis necessary

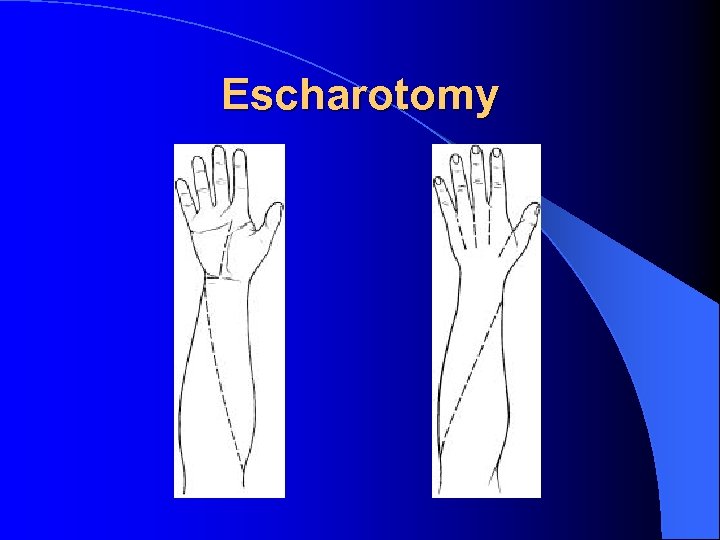

Burn Wound Care: Major Burns l Full thickness circumferential burns can result in vascular compromise necessitating escharotomy – Performed on medial and lateral aspect of extremity and extend length of constricting eschar – Can use scalpel or electo-cautery l Following escharotomy tissue edema can result in compartment syndrome necessitating fasciotomy

Escharotomy

Major Wound Dressing Gentle cleansing with saline or commercial product (Shur-Clens) l Debridement of devitalized tissue and blisters (except those on palms and soles) l Application of topical antimicrobials (flamazine) or bacitracin/polysporin l – Polysporin less bactericidal than flamazine but also less toxic to skin l Transfer to burn center

Burn Wound Care: Minor Burns Proper patient selection and appropriate follow-up l Care with burns involving critical areas of the body (i. e. face, hands, perineum) l Minor burns are not associated with immunosuppression, hypermetabolism or susceptibility to infection l Adequate pain control essential l – NSAIDs mainstay of treatment

Minor Burn Care l General Care. Clean with soap and water. Leave hair intact. Debride devitalized tissue and ruptured blisters. Tetanus booster. l Blisters. Management controversial. Poor evidence either way. Generally leave intact. If large or tense decompress with needle aspiration.

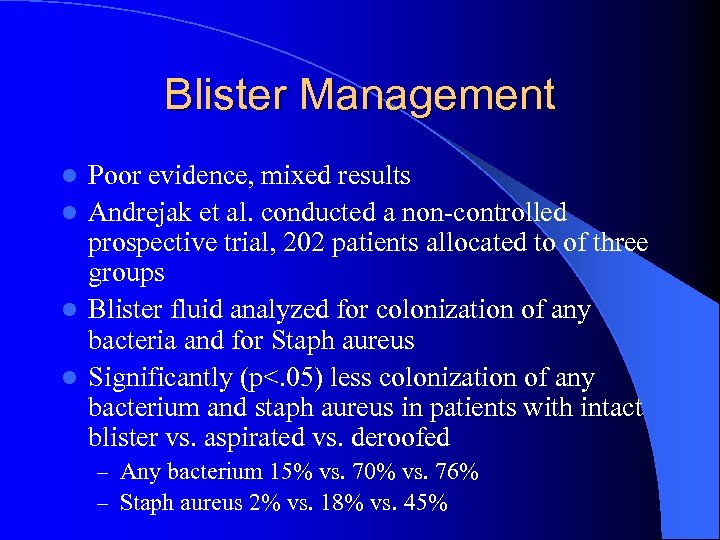

Blister Management Poor evidence, mixed results l Andrejak et al. conducted a non-controlled prospective trial, 202 patients allocated to of three groups l Blister fluid analyzed for colonization of any bacteria and for Staph aureus l Significantly (p<. 05) less colonization of any bacterium and staph aureus in patients with intact blister vs. aspirated vs. deroofed l – Any bacterium 15% vs. 70% vs. 76% – Staph aureus 2% vs. 18% vs. 45%

Minor Burn Care l Dressings. Some minor burns can be left open (i. e. face neck). Wash twice daily with soap. Care in sun b/c of hyperpigmentation. Most minor burns are dressed. Dressing should be changed daily or every other day. Burn should be cleaned with soap and water with dressing changes.

Minor Burn Care l Topical antibiotics. Continued debate. Decrease infection in serious burns with 50 % mortality reduction. Agents include sulfazidine (flamazine), mafenide acetate, silver nitrate. No evidence that these medications offer any benefit in 1 st degree or partial thickness injury. Most experts agree that topical antimicrobials useful in large, deep partial or full thickness burns. Aloe vera may also be beneficial

Minor Burn Care l Synthetic dressings. Include tegaderm, duoderm, etc. Useful for partial thickness burns promoting healing, decreasing pain and requiring less frequent dressing changes. Not indicated for full thickness burns and should not be applied to infected burns. Blisters and devitalized tissue need to be debrided. Can only be applied on fresh burns 1 -2 cm over burn margin and needs to be changed daily

Hot Tar Burns Tar heated to the liquid form that inadvertently comes in contact with skin transfers sufficient heat to cause burn injury l As the tar cools it solidifies making removal challenging l Two distinct forms of tar: l – Coal pitch – Petroleum-derived asphalts Both used for paving and roofing l Higher temperatures needed for roofing deeper burns l

Hot Tar Burns: Management l H 2 O should be applied immediately at scene to cool tar limiting injury and further damage; continue cooling until tar hardens l Adherent tar should not be removed at scene l Adherent tar should be removed in the ED to prevent underlying bacterial growth converting partial full thickness burn

Hot Tar Burns: Management l l l Asphalts susceptible to aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons (HC’s) Coal tars are susceptible to aromatic HC’s Aromatic HC’s have serious potential systemic side effects Long chain HC’s may also be effective without serious side effects Multiple applications of various agents may be required

Mr. Little An 18 month toddler is brought into the ED after suffering 3 rd degree burns to his right arm and leg following a boiling grease spill. l What special fluid requirements does this toddler need? l What is your goal u/o for resuscitation?

Pediatric Burns l 1/3 of burn unit admissions are children < 15 years l 1/3 burn deaths involve children; 2 nd leading cause of death in children > 1 year l Scalds (50 -60%), flame (30%), hot solids (10%), chemical and electrical (<2%) l Child abuse 10%

Special Considerations in Pediatric Burns l Children < 2 years have high SA/mass ratio, thin skin and lower physiologic reserve – High morbidity and mortality Pre-existing diseases can complicate care l Infants and toddlers require maintenance fluid in addition to Parkland formula l Goal u/o is higher in kids (1 mg/kg/hr) l Infants are susceptible to hypoglycemia l – Frequent monitoring of blood sugar and glucose containing solutions

Burns in Pregnancy l Limited literature from developed countries (primarily case reports) l Special maternal physiological changes l Sydney et al. conducted a case report on 8 patients plus review of literature Sydney et al. Management of burns during pregnancy. Burns 2000. 27: 394 -7.

Burns in Pregnancy l All women should have pregnancy test – Minimize teratogenic meds and imaging l Pregnancy associated with hyperdynamic CV state and expanded blood volume – Timely and aggressive fluid resuscitation essential for placental perfusion – O 2 administrating and upright maternal posture increase fetal oxygenation l Diminished FRC and EEV; increased oxygen requirements – Do not delay ventilatory assistance – Maternal delivery can occur while on MV

Burns in Pregnancy Fetal outcome dependent on fetal age and maternal injury l In second trimester fetal survival is highly dependent on maternal survival l – Consider tocolysis; conservative management unless maternal dictates delivery l In the third trimester if there is significant maternal injury then early delivery recommended – Post delivery maternal physiological changes rapidly reverse and aggressive management can be undertaken l Hypercoaguable states in pregnancy and post burn – Unclear whether anti-coagulation beneficial/required

What you now know… l l l The rule of 9’s in adults, its limitations in pediatrics, comparable tables for pediatrics Burn severity scoring: mild/moderate/severe Smoke lung injury and related inhalational injuries Fluid resuscitation goals and limitation of Parkland formula Treatment of major and minor burn wounds Resuscitation issues in pediatrics and the pregnant patient

88a2ed6b6ee59be7f26b8a3e8486f00f.ppt