Lecture 9. English unemphatic intonation.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 22

THEORETICAL PHONETICS Lecture 9: English Unemphatic Intonation

THEORETICAL PHONETICS Lecture 9: English Unemphatic Intonation

(2) Melody q English unemphatic intonation is characterized by the following features: melody, sentence-stress, tamber, tempo and rhythm. Melody 1. The tones used in English unemphatic sentence are the so-called simple falling tone, the rising tone, and, sometimes, the level tone. 2. The starting pitch-level of the falling tone: (a) If there is only one stressed syllable in the sense-group, the fall starts at a pitch-level somewhat higher than the mid level and usually reaches the lowest level, e. g. Yes. [↘jes] (b) If there are two or more stressed syllables in the sense-group the fall in the last stressed syllable starts at a pitch-level somewhat lower than that of the preceding stressed or unstressed syllable and usually reaches the lowest level, e. g. Sit down. [‘sit ↘daun]. Let’s begin. [‘lets bi↘gin]. ( c ) The rise in the final stressed syllable or in the final unstressed ones begins at the lowest level and does not usually reach the pitch-level of the first stressed syllable, e. g. Shall I begin? [‘ʃæl ai bi↗gin] Shall I begin reading now? [‘ʃæl ai bi’gin ↗ri: diŋ nau] 3. The scale used in English unemphatic intonation is a gradually descending one. Its first stressed syllable is pronounced either on a level pitch or with a slight rise within it, e. g. (p. 146) Find page 29. [‘faind ‘peiʤ ‘twenti ↘nain] • Each stressed syllable that follows the first stressed one is pronounced on a slightly lower pitch than the preceding syllable, until the last stressed syllable is reached. The pitch intervals between the stressed syllables are more or less equal. Too many cooks spoil the broth. [‘tu: meni ‘kuks ‘spoil ðә ↘broθ] • The pitch-level of the first stressed syllable of the descending scale is not deliberately raised or lowered. It is somewhat higher than the mid pitch-level, e. g. Come in. [‘kʌm ↗in] • The initial unstressed syllables preceding the descending scale are pronounced either on a low-level pitch, or on a mid-level pitch, or each successive syllable a little higher than the preceding one, e. g. (p. 147) It was an important speech. [it wәz әn im’pͻ: tәnt ↘spi: tʃ]

(2) Melody q English unemphatic intonation is characterized by the following features: melody, sentence-stress, tamber, tempo and rhythm. Melody 1. The tones used in English unemphatic sentence are the so-called simple falling tone, the rising tone, and, sometimes, the level tone. 2. The starting pitch-level of the falling tone: (a) If there is only one stressed syllable in the sense-group, the fall starts at a pitch-level somewhat higher than the mid level and usually reaches the lowest level, e. g. Yes. [↘jes] (b) If there are two or more stressed syllables in the sense-group the fall in the last stressed syllable starts at a pitch-level somewhat lower than that of the preceding stressed or unstressed syllable and usually reaches the lowest level, e. g. Sit down. [‘sit ↘daun]. Let’s begin. [‘lets bi↘gin]. ( c ) The rise in the final stressed syllable or in the final unstressed ones begins at the lowest level and does not usually reach the pitch-level of the first stressed syllable, e. g. Shall I begin? [‘ʃæl ai bi↗gin] Shall I begin reading now? [‘ʃæl ai bi’gin ↗ri: diŋ nau] 3. The scale used in English unemphatic intonation is a gradually descending one. Its first stressed syllable is pronounced either on a level pitch or with a slight rise within it, e. g. (p. 146) Find page 29. [‘faind ‘peiʤ ‘twenti ↘nain] • Each stressed syllable that follows the first stressed one is pronounced on a slightly lower pitch than the preceding syllable, until the last stressed syllable is reached. The pitch intervals between the stressed syllables are more or less equal. Too many cooks spoil the broth. [‘tu: meni ‘kuks ‘spoil ðә ↘broθ] • The pitch-level of the first stressed syllable of the descending scale is not deliberately raised or lowered. It is somewhat higher than the mid pitch-level, e. g. Come in. [‘kʌm ↗in] • The initial unstressed syllables preceding the descending scale are pronounced either on a low-level pitch, or on a mid-level pitch, or each successive syllable a little higher than the preceding one, e. g. (p. 147) It was an important speech. [it wәz әn im’pͻ: tәnt ↘spi: tʃ]

(3) continuation • The final unstressed syllables that follow the terminal fall are usually pronounced on the lowest level pitch, or may sometimes continue the fall which takes place within the last stressed syllable and does not reach, in this case, the lowest level, e. g. Read the first paragraph. [‘ri: d ðә ‘fә: st ↘pærәgrɑ: f] Besides the gradually descending scale, there is the so-called broken descending scale, which forms a kind of link between unemphatic and emphatic intonation: it is when one of the syllables in the middle of a sentence is pronounced on a higher pitch than the preceding one, and then another descending scale follows. § The broken descending scale is used when the meaning of the sentence requires that one word should be singled out for some reason. A special rise is indicated by an upward-pointing arrow (↑) before the syllable in which it takes place, e. g. (p. 148) (p. 147) My friend knows lots of interesting men. [mai ‘frend ‘nәuz ↑lͻts әv ‘intristiŋ ↘men] • A special rise is made sometimes on a word which is rather important, e. g. , numerals.

(3) continuation • The final unstressed syllables that follow the terminal fall are usually pronounced on the lowest level pitch, or may sometimes continue the fall which takes place within the last stressed syllable and does not reach, in this case, the lowest level, e. g. Read the first paragraph. [‘ri: d ðә ‘fә: st ↘pærәgrɑ: f] Besides the gradually descending scale, there is the so-called broken descending scale, which forms a kind of link between unemphatic and emphatic intonation: it is when one of the syllables in the middle of a sentence is pronounced on a higher pitch than the preceding one, and then another descending scale follows. § The broken descending scale is used when the meaning of the sentence requires that one word should be singled out for some reason. A special rise is indicated by an upward-pointing arrow (↑) before the syllable in which it takes place, e. g. (p. 148) (p. 147) My friend knows lots of interesting men. [mai ‘frend ‘nәuz ↑lͻts әv ‘intristiŋ ↘men] • A special rise is made sometimes on a word which is rather important, e. g. , numerals.

(4) Sentence-stress, tamber, tempo and rhythm • Sentence-stress: no words in unemphatic sentence are pronounced with deliberately increased stress. • Tamber: unemphatic sentences are pronounced with a tamber which does not express any particular emotions. • Tempo and rhythm: unemphatic sentences are pronounced with a tempo which is not deliberately quickened or slowed down to express any particular emotions. • Any alteration of the tempo is determined by the semantic importance, presence or absence of stress on this or that word, the number, degree and position of stresses. Compare the sentence with three and two stresses: (p. 150) I don’t think she knows. [ai ‘dәunt ‘θiŋk ∫i: ↘nәuz] or: [ai ‘dәunt θiŋk ∫i: ↘nәuz] The tempo in the second variant is noticeably quicker. The rhythm of an unemphatic sentence is characterized by the recurrence of stressed syllables at more or less equal intervals of time.

(4) Sentence-stress, tamber, tempo and rhythm • Sentence-stress: no words in unemphatic sentence are pronounced with deliberately increased stress. • Tamber: unemphatic sentences are pronounced with a tamber which does not express any particular emotions. • Tempo and rhythm: unemphatic sentences are pronounced with a tempo which is not deliberately quickened or slowed down to express any particular emotions. • Any alteration of the tempo is determined by the semantic importance, presence or absence of stress on this or that word, the number, degree and position of stresses. Compare the sentence with three and two stresses: (p. 150) I don’t think she knows. [ai ‘dәunt ‘θiŋk ∫i: ↘nәuz] or: [ai ‘dәunt θiŋk ∫i: ↘nәuz] The tempo in the second variant is noticeably quicker. The rhythm of an unemphatic sentence is characterized by the recurrence of stressed syllables at more or less equal intervals of time.

(5) The use of tones in sentences containing a single sense-group • The use of the two fundamental tones of English speech (the falling and the rising tones) is determined by their general semantic characteristics. • The falling tone expresses finality and is definite and categoric in character. • The rising tone expresses non-finality and is indefinite and non-categorical in character. • The third tone in English is the level tone which is more indefinite and non-categorical than the rising tone. Its function is rather limited. This tone is used rather rarely in colloquial speech. It is used in reciting poems.

(5) The use of tones in sentences containing a single sense-group • The use of the two fundamental tones of English speech (the falling and the rising tones) is determined by their general semantic characteristics. • The falling tone expresses finality and is definite and categoric in character. • The rising tone expresses non-finality and is indefinite and non-categorical in character. • The third tone in English is the level tone which is more indefinite and non-categorical than the rising tone. Its function is rather limited. This tone is used rather rarely in colloquial speech. It is used in reciting poems.

(6) The use of the falling tone The falling tone is used in the following communicative types of sentences: (1) In categoric statements, or assertions (2) In special questions (3) In commands (4) In exclamations (or statement-like exclamations) (5) In sentences expressing offers to do something or suggestions that something should be done.

(6) The use of the falling tone The falling tone is used in the following communicative types of sentences: (1) In categoric statements, or assertions (2) In special questions (3) In commands (4) In exclamations (or statement-like exclamations) (5) In sentences expressing offers to do something or suggestions that something should be done.

(7) Examples of the falling tone (1) Categoric statements: (p. 151) It’s time to get up. [its ‘taim tә ‘get ↘ʌp] It wasn’t ready. [it ‘wͻznt ↘redi] (2) Special questions: Who is on duty today? [‘hu: iz ͻn ↘dju: ti tәdei] (3) Commands: (p. 152) Stand up! [‘stænd ↘ʌp] Open your books at page five! [‘әupn jͻ: ‘buks әt ‘peiʤ↘faiv] (4) Exclamations: What a cold day! [wͻt ә ‘kәuld ↘dei] How late you are! [‘hau ↘leit ju: ɑ: ] (5) Offers to do something or suggestions that something should be done. (p. 153) Let’s go home! [‘lets gәu↘hәum]

(7) Examples of the falling tone (1) Categoric statements: (p. 151) It’s time to get up. [its ‘taim tә ‘get ↘ʌp] It wasn’t ready. [it ‘wͻznt ↘redi] (2) Special questions: Who is on duty today? [‘hu: iz ͻn ↘dju: ti tәdei] (3) Commands: (p. 152) Stand up! [‘stænd ↘ʌp] Open your books at page five! [‘әupn jͻ: ‘buks әt ‘peiʤ↘faiv] (4) Exclamations: What a cold day! [wͻt ә ‘kәuld ↘dei] How late you are! [‘hau ↘leit ju: ɑ: ] (5) Offers to do something or suggestions that something should be done. (p. 153) Let’s go home! [‘lets gәu↘hәum]

(8) The use of the rising tone The rising tone is used in the following communicative types of sentences: (1) In general questions (2) In requests (3) In non-categoric statements, or in sentences in which something is implied (4) In greetings pronounced on parting (5) In special questions expressing a friendly interest in the hearer or forming a series as if in a questionnaire, or implying a mild approach (6) In questions expressing a request to repeat a previously made statement (7) In echoing questions.

(8) The use of the rising tone The rising tone is used in the following communicative types of sentences: (1) In general questions (2) In requests (3) In non-categoric statements, or in sentences in which something is implied (4) In greetings pronounced on parting (5) In special questions expressing a friendly interest in the hearer or forming a series as if in a questionnaire, or implying a mild approach (6) In questions expressing a request to repeat a previously made statement (7) In echoing questions.

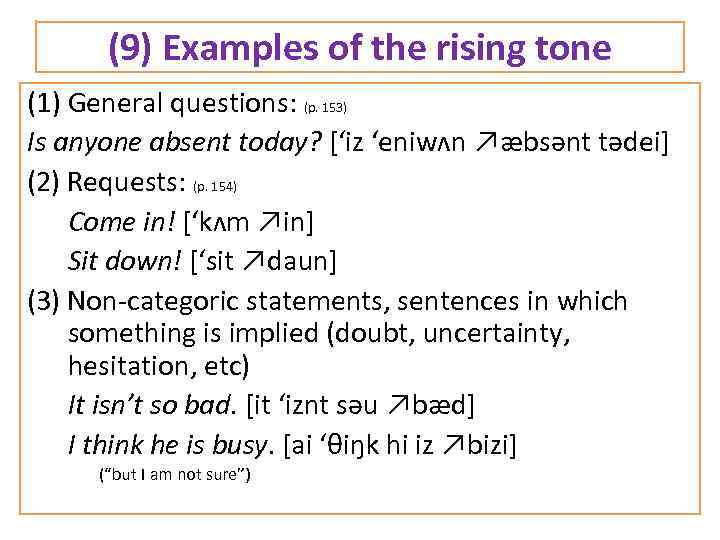

(9) Examples of the rising tone (1) General questions: (p. 153) Is anyone absent today? [‘iz ‘eniwʌn ↗æbsәnt tәdei] (2) Requests: (p. 154) Come in! [‘kʌm ↗in] Sit down! [‘sit ↗daun] (3) Non-categoric statements, sentences in which something is implied (doubt, uncertainty, hesitation, etc) It isn’t so bad. [it ‘iznt sәu ↗bæd] I think he is busy. [ai ‘θiŋk hi iz ↗bizi] (“but I am not sure”)

(9) Examples of the rising tone (1) General questions: (p. 153) Is anyone absent today? [‘iz ‘eniwʌn ↗æbsәnt tәdei] (2) Requests: (p. 154) Come in! [‘kʌm ↗in] Sit down! [‘sit ↗daun] (3) Non-categoric statements, sentences in which something is implied (doubt, uncertainty, hesitation, etc) It isn’t so bad. [it ‘iznt sәu ↗bæd] I think he is busy. [ai ‘θiŋk hi iz ↗bizi] (“but I am not sure”)

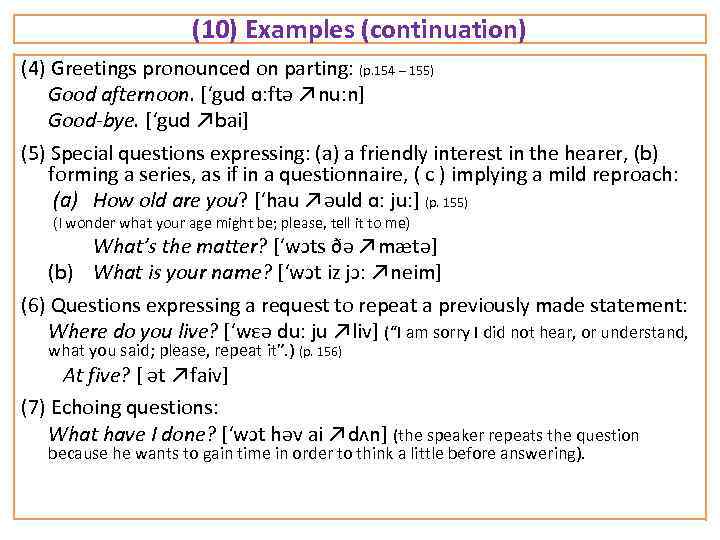

(10) Examples (continuation) (4) Greetings pronounced on parting: (p. 154 – 155) Good afternoon. [‘gud ɑ: ftә ↗nu: n] Good-bye. [‘gud ↗bai] (5) Special questions expressing: (a) a friendly interest in the hearer, (b) forming a series, as if in a questionnaire, ( c ) implying a mild reproach: (a) How old are you? [‘hau ↗әuld ɑ: ju: ] (p. 155) (I wonder what your age might be; please, tell it to me) What’s the matter? [‘wͻts ðә ↗mætә] (b) What is your name? [‘wͻt iz jͻ: ↗neim] (6) Questions expressing a request to repeat a previously made statement: Where do you live? [‘wεә du: ju ↗liv] (“I am sorry I did not hear, or understand, what you said; please, repeat it”. ) (p. 156) At five? [ әt ↗faiv] (7) Echoing questions: What have I done? [‘wͻt hәv ai ↗dʌn] (the speaker repeats the question because he wants to gain time in order to think a little before answering).

(10) Examples (continuation) (4) Greetings pronounced on parting: (p. 154 – 155) Good afternoon. [‘gud ɑ: ftә ↗nu: n] Good-bye. [‘gud ↗bai] (5) Special questions expressing: (a) a friendly interest in the hearer, (b) forming a series, as if in a questionnaire, ( c ) implying a mild reproach: (a) How old are you? [‘hau ↗әuld ɑ: ju: ] (p. 155) (I wonder what your age might be; please, tell it to me) What’s the matter? [‘wͻts ðә ↗mætә] (b) What is your name? [‘wͻt iz jͻ: ↗neim] (6) Questions expressing a request to repeat a previously made statement: Where do you live? [‘wεә du: ju ↗liv] (“I am sorry I did not hear, or understand, what you said; please, repeat it”. ) (p. 156) At five? [ әt ↗faiv] (7) Echoing questions: What have I done? [‘wͻt hәv ai ↗dʌn] (the speaker repeats the question because he wants to gain time in order to think a little before answering).

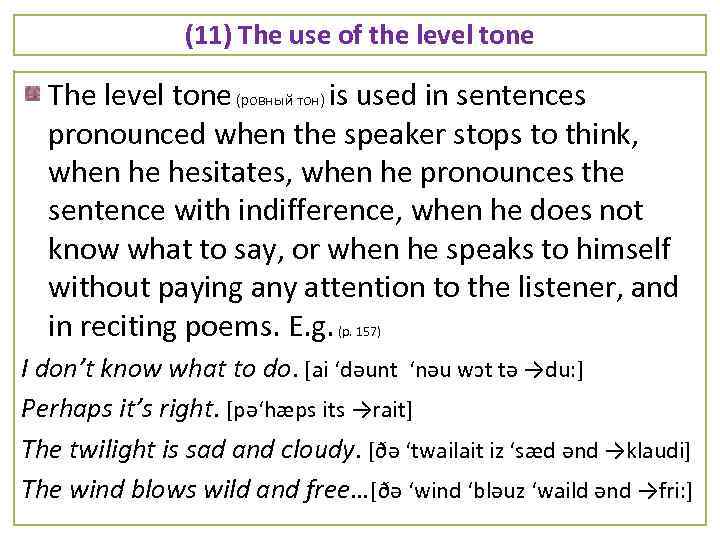

(11) The use of the level tone The level tone (ровный тон) is used in sentences pronounced when the speaker stops to think, when he hesitates, when he pronounces the sentence with indifference, when he does not know what to say, or when he speaks to himself without paying any attention to the listener, and in reciting poems. E. g. (p. 157) I don’t know what to do. [ai ‘dәunt ‘nәu wͻt tә →du: ] Perhaps it’s right. [pә‘hæps its →rait] The twilight is sad and cloudy. [ðә ‘twailait iz ‘sæd әnd →klaudi] The wind blows wild and free…[ðә ‘wind ‘blәuz ‘waild әnd →fri: ]

(11) The use of the level tone The level tone (ровный тон) is used in sentences pronounced when the speaker stops to think, when he hesitates, when he pronounces the sentence with indifference, when he does not know what to say, or when he speaks to himself without paying any attention to the listener, and in reciting poems. E. g. (p. 157) I don’t know what to do. [ai ‘dәunt ‘nәu wͻt tә →du: ] Perhaps it’s right. [pә‘hæps its →rait] The twilight is sad and cloudy. [ðә ‘twailait iz ‘sæd әnd →klaudi] The wind blows wild and free…[ðә ‘wind ‘blәuz ‘waild әnd →fri: ]

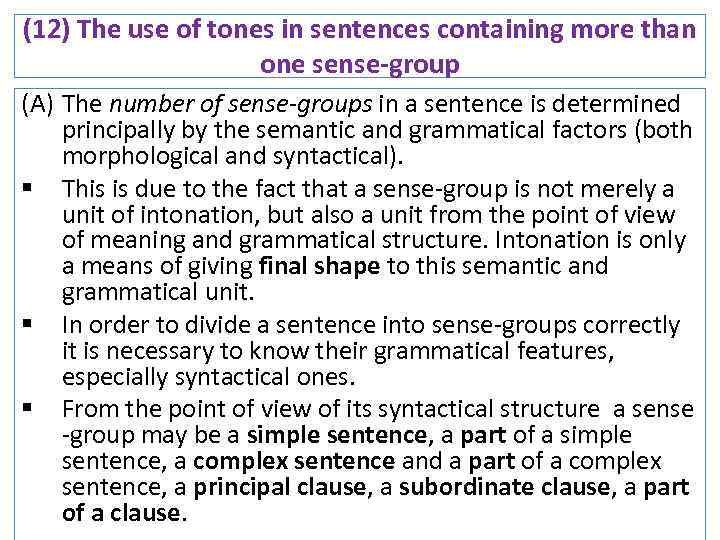

(12) The use of tones in sentences containing more than one sense-group (A) The number of sense-groups in a sentence is determined principally by the semantic and grammatical factors (both morphological and syntactical). § This is due to the fact that a sense-group is not merely a unit of intonation, but also a unit from the point of view of meaning and grammatical structure. Intonation is only a means of giving final shape to this semantic and grammatical unit. § In order to divide a sentence into sense-groups correctly it is necessary to know their grammatical features, especially syntactical ones. § From the point of view of its syntactical structure a sense -group may be a simple sentence, a part of a simple sentence, a complex sentence and a part of a complex sentence, a principal clause, a subordinate clause, a part of a clause.

(12) The use of tones in sentences containing more than one sense-group (A) The number of sense-groups in a sentence is determined principally by the semantic and grammatical factors (both morphological and syntactical). § This is due to the fact that a sense-group is not merely a unit of intonation, but also a unit from the point of view of meaning and grammatical structure. Intonation is only a means of giving final shape to this semantic and grammatical unit. § In order to divide a sentence into sense-groups correctly it is necessary to know their grammatical features, especially syntactical ones. § From the point of view of its syntactical structure a sense -group may be a simple sentence, a part of a simple sentence, a complex sentence and a part of a complex sentence, a principal clause, a subordinate clause, a part of a clause.

(13) continuation • The correct division of a sentence into sense-groups is of great importance because it is very difficult or sometimes impossible to understand the meaning of a sentence when it is wrongly divided into sense-groups. (B) The choice of the tone to be used in the final and nonfinal sense-groups of a sentence is determined by the communicative type of the sentence. • A non-final sense-group may be pronounced either with the falling tone or with the rising tone; it may also be pronounced with the level tone. The choice of he tone to be used in a final sense-group is determined by its semantic importance, completeness and degree of its connection with the following sense-group.

(13) continuation • The correct division of a sentence into sense-groups is of great importance because it is very difficult or sometimes impossible to understand the meaning of a sentence when it is wrongly divided into sense-groups. (B) The choice of the tone to be used in the final and nonfinal sense-groups of a sentence is determined by the communicative type of the sentence. • A non-final sense-group may be pronounced either with the falling tone or with the rising tone; it may also be pronounced with the level tone. The choice of he tone to be used in a final sense-group is determined by its semantic importance, completeness and degree of its connection with the following sense-group.

(14) Sentence-stress • Sentence-stress is a greater prominence with which one or more words in a sentence are pronounced as compared with the other words of the same sentence. • Sentence-stress has two main functions. (1) Its first function is to single out words in the sentence according to their relative semantic importance. The more important the word is, the stronger is the stress. (2) The second function of sentence-stress is to serve as the basis for the rhythmical structure of the sentence. Due to the peculiarity of the rhythm semantically important words which are usually stressed may be pronounced without sentence-stress. Cf. Very good. [‘veri ↘gud]. Not very good. [‘not veri ↘gud] In the first sentence both words are stressed because they both express the meaning of the sentence. In the second sentence the word very loses its stress under the influence of the rhythm, i. e. in order not to pronounce two stressed syllables in succession.

(14) Sentence-stress • Sentence-stress is a greater prominence with which one or more words in a sentence are pronounced as compared with the other words of the same sentence. • Sentence-stress has two main functions. (1) Its first function is to single out words in the sentence according to their relative semantic importance. The more important the word is, the stronger is the stress. (2) The second function of sentence-stress is to serve as the basis for the rhythmical structure of the sentence. Due to the peculiarity of the rhythm semantically important words which are usually stressed may be pronounced without sentence-stress. Cf. Very good. [‘veri ↘gud]. Not very good. [‘not veri ↘gud] In the first sentence both words are stressed because they both express the meaning of the sentence. In the second sentence the word very loses its stress under the influence of the rhythm, i. e. in order not to pronounce two stressed syllables in succession.

(15) Words to be stressed • Words which are usually stressed in English unemphatic speech belong to notional parts of speech, namely: • Nouns • Adjectives • Numerals • Notional verbs • Adverbs • Demonstrative pronouns (this, that, etc) • Interrogative pronouns (who, which, etc) • Emphasizing pronouns (himself, herself, etc) • Absolute form of possessive pronouns (hers, ours, etc)

(15) Words to be stressed • Words which are usually stressed in English unemphatic speech belong to notional parts of speech, namely: • Nouns • Adjectives • Numerals • Notional verbs • Adverbs • Demonstrative pronouns (this, that, etc) • Interrogative pronouns (who, which, etc) • Emphasizing pronouns (himself, herself, etc) • Absolute form of possessive pronouns (hers, ours, etc)

(16) Words which usually are not stressed q • • However, the following words which also belong to the notional parts of speech, are usually not stressed: personal pronouns possessive pronouns reflexive pronouns and relative pronouns q The other class of words which are usually not stressed in English unemphatic speech are form-words, i. e. words which express grammatical relationship of words in the sentence. These are: • auxiliary verbs • modal verbs • the verb to be • prepositions • conjunctions • articles • particles However, it is necessary to point out that any word in a sentence may be logically stressed, e. g. ‘Where ↘have you been? ‘Where have ↘you been? A word which is made prominent by logical stress may stand at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of a sense-group, and it is usually the last stressed word in it. Sentence-stress on words following logical stress either disappears or becomes weak.

(16) Words which usually are not stressed q • • However, the following words which also belong to the notional parts of speech, are usually not stressed: personal pronouns possessive pronouns reflexive pronouns and relative pronouns q The other class of words which are usually not stressed in English unemphatic speech are form-words, i. e. words which express grammatical relationship of words in the sentence. These are: • auxiliary verbs • modal verbs • the verb to be • prepositions • conjunctions • articles • particles However, it is necessary to point out that any word in a sentence may be logically stressed, e. g. ‘Where ↘have you been? ‘Where have ↘you been? A word which is made prominent by logical stress may stand at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of a sense-group, and it is usually the last stressed word in it. Sentence-stress on words following logical stress either disappears or becomes weak.

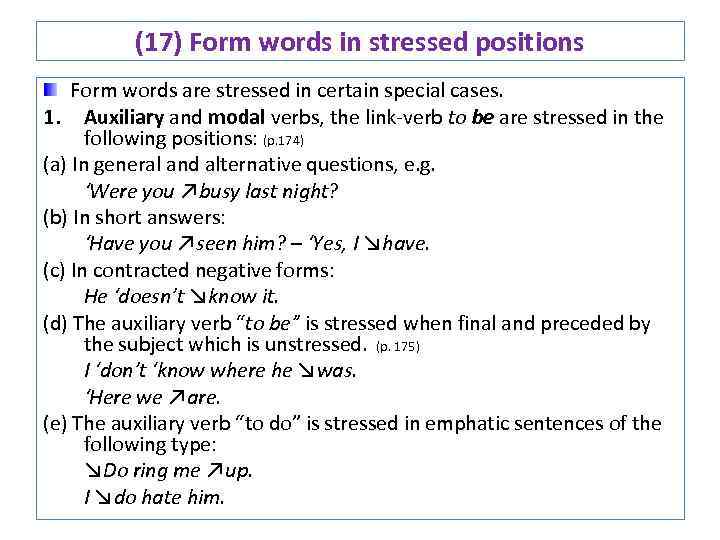

(17) Form words in stressed positions Form words are stressed in certain special cases. 1. Auxiliary and modal verbs, the link-verb to be are stressed in the following positions: (p. 174) (a) In general and alternative questions, e. g. ‘Were you ↗busy last night? (b) In short answers: ‘Have you ↗seen him? – ‘Yes, I ↘have. (c) In contracted negative forms: He ‘doesn’t ↘know it. (d) The auxiliary verb “to be” is stressed when final and preceded by the subject which is unstressed. (p. 175) I ‘don’t ‘know where he ↘was. ‘Here we ↗are. (e) The auxiliary verb “to do” is stressed in emphatic sentences of the following type: ↘Do ring me ↗up. I ↘do hate him.

(17) Form words in stressed positions Form words are stressed in certain special cases. 1. Auxiliary and modal verbs, the link-verb to be are stressed in the following positions: (p. 174) (a) In general and alternative questions, e. g. ‘Were you ↗busy last night? (b) In short answers: ‘Have you ↗seen him? – ‘Yes, I ↘have. (c) In contracted negative forms: He ‘doesn’t ↘know it. (d) The auxiliary verb “to be” is stressed when final and preceded by the subject which is unstressed. (p. 175) I ‘don’t ‘know where he ↘was. ‘Here we ↗are. (e) The auxiliary verb “to do” is stressed in emphatic sentences of the following type: ↘Do ring me ↗up. I ↘do hate him.

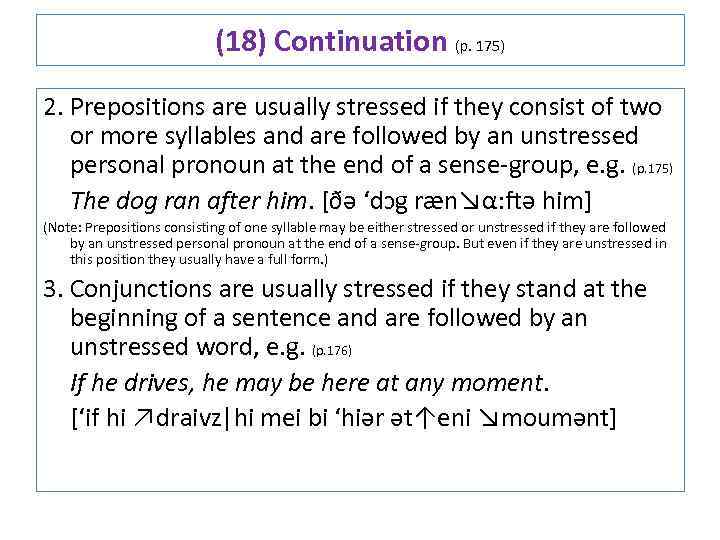

(18) Continuation (p. 175) 2. Prepositions are usually stressed if they consist of two or more syllables and are followed by an unstressed personal pronoun at the end of a sense-group, e. g. (p. 175) The dog ran after him. [ðә ‘dͻg ræn↘α: ftә him] (Note: Prepositions consisting of one syllable may be either stressed or unstressed if they are followed by an unstressed personal pronoun at the end of a sense-group. But even if they are unstressed in this position they usually have a full form. ) 3. Conjunctions are usually stressed if they stand at the beginning of a sentence and are followed by an unstressed word, e. g. (p. 176) If he drives, he may be here at any moment. [‘if hi ↗draivz|hi mei bi ‘hiәr әt↑eni ↘moumәnt]

(18) Continuation (p. 175) 2. Prepositions are usually stressed if they consist of two or more syllables and are followed by an unstressed personal pronoun at the end of a sense-group, e. g. (p. 175) The dog ran after him. [ðә ‘dͻg ræn↘α: ftә him] (Note: Prepositions consisting of one syllable may be either stressed or unstressed if they are followed by an unstressed personal pronoun at the end of a sense-group. But even if they are unstressed in this position they usually have a full form. ) 3. Conjunctions are usually stressed if they stand at the beginning of a sentence and are followed by an unstressed word, e. g. (p. 176) If he drives, he may be here at any moment. [‘if hi ↗draivz|hi mei bi ‘hiәr әt↑eni ↘moumәnt]

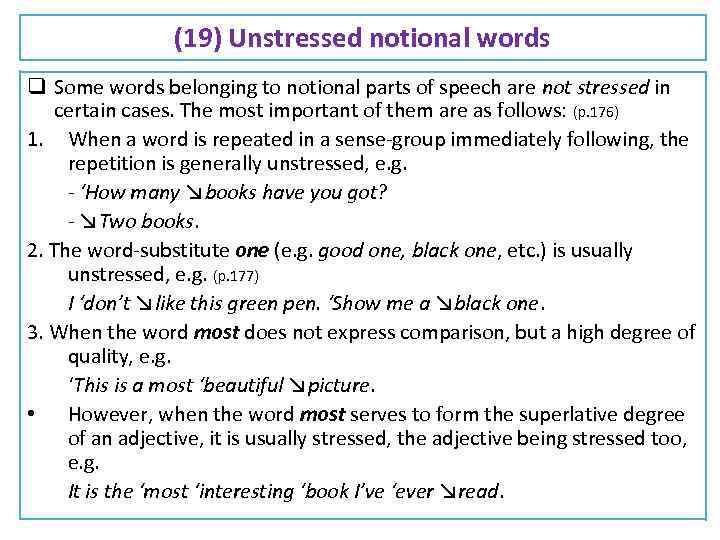

(19) Unstressed notional words q Some words belonging to notional parts of speech are not stressed in certain cases. The most important of them are as follows: (p. 176) 1. When a word is repeated in a sense-group immediately following, the repetition is generally unstressed, e. g. - ‘How many ↘books have you got? - ↘Two books. 2. The word-substitute one (e. g. good one, black one, etc. ) is usually unstressed, e. g. (p. 177) I ‘don’t ↘like this green pen. ‘Show me a ↘black one. 3. When the word most does not express comparison, but a high degree of quality, e. g. ‘This is a most ‘beautiful ↘picture. • However, when the word most serves to form the superlative degree of an adjective, it is usually stressed, the adjective being stressed too, e. g. It is the ‘most ‘interesting ‘book I’ve ‘ever ↘read.

(19) Unstressed notional words q Some words belonging to notional parts of speech are not stressed in certain cases. The most important of them are as follows: (p. 176) 1. When a word is repeated in a sense-group immediately following, the repetition is generally unstressed, e. g. - ‘How many ↘books have you got? - ↘Two books. 2. The word-substitute one (e. g. good one, black one, etc. ) is usually unstressed, e. g. (p. 177) I ‘don’t ↘like this green pen. ‘Show me a ↘black one. 3. When the word most does not express comparison, but a high degree of quality, e. g. ‘This is a most ‘beautiful ↘picture. • However, when the word most serves to form the superlative degree of an adjective, it is usually stressed, the adjective being stressed too, e. g. It is the ‘most ‘interesting ‘book I’ve ‘ever ↘read.

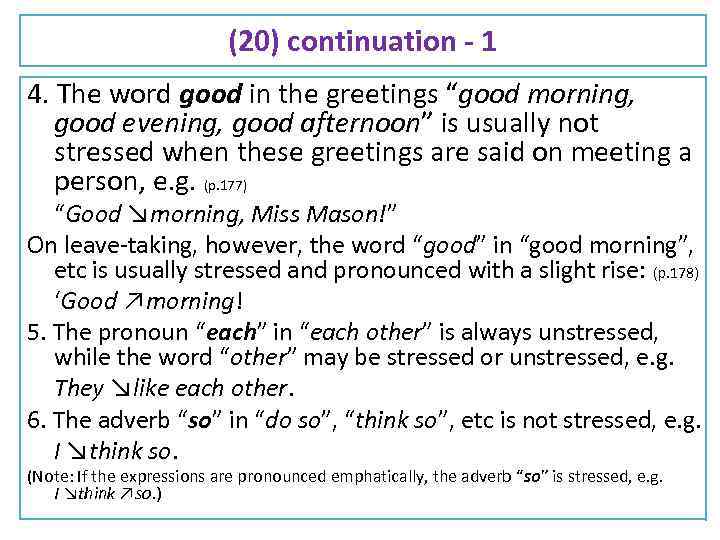

(20) continuation - 1 4. The word good in the greetings “good morning, good evening, good afternoon” is usually not stressed when these greetings are said on meeting a person, e. g. (p. 177) “Good ↘morning, Miss Mason!” On leave-taking, however, the word “good” in “good morning”, etc is usually stressed and pronounced with a slight rise: (p. 178) ‘Good ↗morning! 5. The pronoun “each” in “each other” is always unstressed, while the word “other” may be stressed or unstressed, e. g. They ↘like each other. 6. The adverb “so” in “do so”, “think so”, etc is not stressed, e. g. I ↘think so. (Note: If the expressions are pronounced emphatically, the adverb “so” is stressed, e. g. I ↘think ↗so. )

(20) continuation - 1 4. The word good in the greetings “good morning, good evening, good afternoon” is usually not stressed when these greetings are said on meeting a person, e. g. (p. 177) “Good ↘morning, Miss Mason!” On leave-taking, however, the word “good” in “good morning”, etc is usually stressed and pronounced with a slight rise: (p. 178) ‘Good ↗morning! 5. The pronoun “each” in “each other” is always unstressed, while the word “other” may be stressed or unstressed, e. g. They ↘like each other. 6. The adverb “so” in “do so”, “think so”, etc is not stressed, e. g. I ↘think so. (Note: If the expressions are pronounced emphatically, the adverb “so” is stressed, e. g. I ↘think ↗so. )

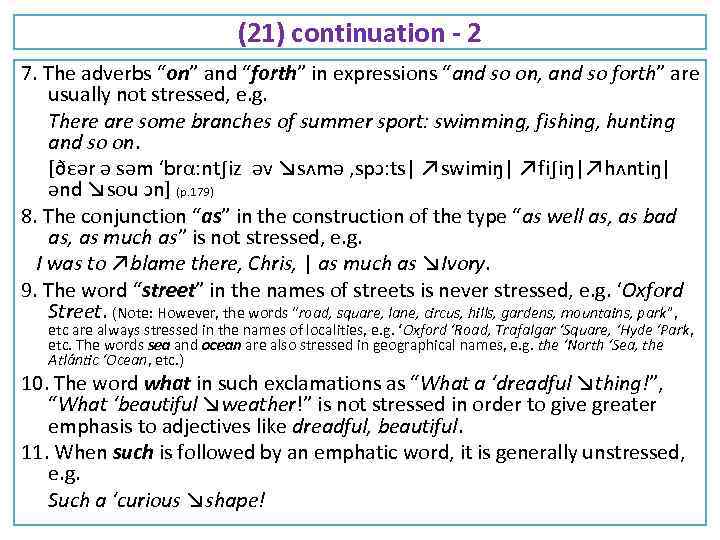

(21) continuation - 2 7. The adverbs “on” and “forth” in expressions “and so on, and so forth” are usually not stressed, e. g. There are some branches of summer sport: swimming, fishing, hunting and so on. [ðεәr ә sәm ‘brα: nt∫iz әv ↘sʌmә , spͻ: ts| ↗swimiŋ| ↗fi∫iŋ|↗hʌntiŋ| әnd ↘sou ͻn] (p. 179) 8. The conjunction “as” in the construction of the type “as well as, as bad as, as much as” is not stressed, e. g. I was to ↗blame there, Chris, | as much as ↘Ivory. 9. The word “street” in the names of streets is never stressed, e. g. ‘Oxford Street. (Note: However, the words “road, square, lane, circus, hills, gardens, mountains, park”, etc are always stressed in the names of localities, e. g. ‘Oxford ‘Road, Trafalgar ‘Square, ‘Hyde ‘Park, etc. The words sea and ocean are also stressed in geographical names, e. g. the ‘North ‘Sea, the Atlántic ‘Ocean, etc. ) 10. The word what in such exclamations as “What a ‘dreadful ↘thing!”, “What ‘beautiful ↘weather!” is not stressed in order to give greater emphasis to adjectives like dreadful, beautiful. 11. When such is followed by an emphatic word, it is generally unstressed, e. g. Such a ‘curious ↘shape!

(21) continuation - 2 7. The adverbs “on” and “forth” in expressions “and so on, and so forth” are usually not stressed, e. g. There are some branches of summer sport: swimming, fishing, hunting and so on. [ðεәr ә sәm ‘brα: nt∫iz әv ↘sʌmә , spͻ: ts| ↗swimiŋ| ↗fi∫iŋ|↗hʌntiŋ| әnd ↘sou ͻn] (p. 179) 8. The conjunction “as” in the construction of the type “as well as, as bad as, as much as” is not stressed, e. g. I was to ↗blame there, Chris, | as much as ↘Ivory. 9. The word “street” in the names of streets is never stressed, e. g. ‘Oxford Street. (Note: However, the words “road, square, lane, circus, hills, gardens, mountains, park”, etc are always stressed in the names of localities, e. g. ‘Oxford ‘Road, Trafalgar ‘Square, ‘Hyde ‘Park, etc. The words sea and ocean are also stressed in geographical names, e. g. the ‘North ‘Sea, the Atlántic ‘Ocean, etc. ) 10. The word what in such exclamations as “What a ‘dreadful ↘thing!”, “What ‘beautiful ↘weather!” is not stressed in order to give greater emphasis to adjectives like dreadful, beautiful. 11. When such is followed by an emphatic word, it is generally unstressed, e. g. Such a ‘curious ↘shape!

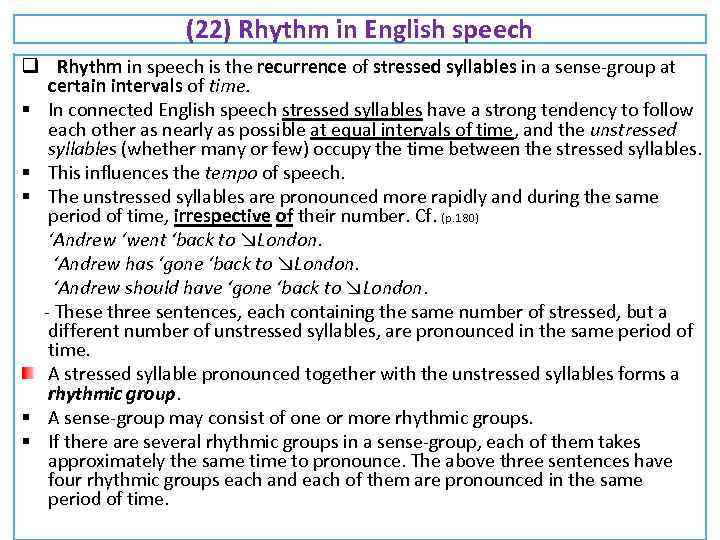

(22) Rhythm in English speech q Rhythm in speech is the recurrence of stressed syllables in a sense-group at certain intervals of time. § In connected English speech stressed syllables have a strong tendency to follow each other as nearly as possible at equal intervals of time, and the unstressed syllables (whether many or few) occupy the time between the stressed syllables. § This influences the tempo of speech. § The unstressed syllables are pronounced more rapidly and during the same period of time, irrespective of their number. Cf. (p. 180) ‘Andrew ‘went ‘back to ↘London. ‘Andrew has ‘gone ‘back to ↘London. ‘Andrew should have ‘gone ‘back to ↘London. - These three sentences, each containing the same number of stressed, but a different number of unstressed syllables, are pronounced in the same period of time. A stressed syllable pronounced together with the unstressed syllables forms a rhythmic group. § A sense-group may consist of one or more rhythmic groups. § If there are several rhythmic groups in a sense-group, each of them takes approximately the same time to pronounce. The above three sentences have four rhythmic groups each and each of them are pronounced in the same period of time.

(22) Rhythm in English speech q Rhythm in speech is the recurrence of stressed syllables in a sense-group at certain intervals of time. § In connected English speech stressed syllables have a strong tendency to follow each other as nearly as possible at equal intervals of time, and the unstressed syllables (whether many or few) occupy the time between the stressed syllables. § This influences the tempo of speech. § The unstressed syllables are pronounced more rapidly and during the same period of time, irrespective of their number. Cf. (p. 180) ‘Andrew ‘went ‘back to ↘London. ‘Andrew has ‘gone ‘back to ↘London. ‘Andrew should have ‘gone ‘back to ↘London. - These three sentences, each containing the same number of stressed, but a different number of unstressed syllables, are pronounced in the same period of time. A stressed syllable pronounced together with the unstressed syllables forms a rhythmic group. § A sense-group may consist of one or more rhythmic groups. § If there are several rhythmic groups in a sense-group, each of them takes approximately the same time to pronounce. The above three sentences have four rhythmic groups each and each of them are pronounced in the same period of time.