20d5b5d8ee50f8581e2e84a9aa1d427f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 23

The Unified Process Harry R. Erwin, Ph. D CSE 301 University of Sunderland

The Unified Process Harry R. Erwin, Ph. D CSE 301 University of Sunderland

Resources • Key text: Lethbridge and Laganiere. • Much of this lecture is based on Chapter 7 of Graham, Object. Oriented Methods, 3 rd edition, Addison-Wesley, an excellent MSc-level text. • Alhir, 1998, UML in a Nutshell, O’Reilly is useful but uneven. • Eriksson, Penker, Lyons & Fado, 2004, UML 2 Toolkit, OMG Press, discusses the recent changes to the standard. • The UML tutorials (Martin) should be studied. • Some of this lecture is based on Dr. Erwin’s experiences as a software architect. If his American idiom is difficult to follow, stop him and ask for an explanation.

Resources • Key text: Lethbridge and Laganiere. • Much of this lecture is based on Chapter 7 of Graham, Object. Oriented Methods, 3 rd edition, Addison-Wesley, an excellent MSc-level text. • Alhir, 1998, UML in a Nutshell, O’Reilly is useful but uneven. • Eriksson, Penker, Lyons & Fado, 2004, UML 2 Toolkit, OMG Press, discusses the recent changes to the standard. • The UML tutorials (Martin) should be studied. • Some of this lecture is based on Dr. Erwin’s experiences as a software architect. If his American idiom is difficult to follow, stop him and ask for an explanation.

Software Architecture • Fred Brooks (1975) indicates the first use of the term was in Blaauw (1970). • At TRW in 1972, we called it ‘Process Design’. Charlie Vick has an early ACM paper on the topic. • Perry and Wolf (1992) define software architecture as consisting of elements, form, and rationale. • Boehm (TRW, various dates) added constraints to rationale. • My 1977 process designs for two ballistic missile defense systems may have been by influenced Boehm’s definition. I developed a formal approach as part of SYSREM, an early CASE methodology developed at TRW. • About 1977, we estimated there worldwide no more than a half dozen process designers with experience in large systems.

Software Architecture • Fred Brooks (1975) indicates the first use of the term was in Blaauw (1970). • At TRW in 1972, we called it ‘Process Design’. Charlie Vick has an early ACM paper on the topic. • Perry and Wolf (1992) define software architecture as consisting of elements, form, and rationale. • Boehm (TRW, various dates) added constraints to rationale. • My 1977 process designs for two ballistic missile defense systems may have been by influenced Boehm’s definition. I developed a formal approach as part of SYSREM, an early CASE methodology developed at TRW. • About 1977, we estimated there worldwide no more than a half dozen process designers with experience in large systems.

Software Architecture Definition • Shaw and Garlan (1996) characterize the software architecture as the high-level structure of a system. • Bass (1998) defines “the software architecture of a program or computing system is the structure or structures of the system, which comprise software components, the externally visible properties of those components and the relationships among them. ”

Software Architecture Definition • Shaw and Garlan (1996) characterize the software architecture as the high-level structure of a system. • Bass (1998) defines “the software architecture of a program or computing system is the structure or structures of the system, which comprise software components, the externally visible properties of those components and the relationships among them. ”

Architecture and Design • Architecture is neither requirements nor design but falls between. • Requirements are frequently written in the form of a logical machine to perform a function. • The system design describes in detail how a physical machine to perform those requirements is built. • The architecture is a high-level description of the physical machine. • Defining an architecture is a creative act, and good software architects are rare (and expensive, about $150, 000 per year salary in the USA).

Architecture and Design • Architecture is neither requirements nor design but falls between. • Requirements are frequently written in the form of a logical machine to perform a function. • The system design describes in detail how a physical machine to perform those requirements is built. • The architecture is a high-level description of the physical machine. • Defining an architecture is a creative act, and good software architects are rare (and expensive, about $150, 000 per year salary in the USA).

Kruchten’s ‘ 4+1 View Model’ of Software Architecture (1995) • Based on Boehm’s definition. • Applies specifically to object-oriented development. • Underlies the Unified Process (the methodology that uses UML). • Deals with abstraction, composition and decomposition, and style and aesthetics.

Kruchten’s ‘ 4+1 View Model’ of Software Architecture (1995) • Based on Boehm’s definition. • Applies specifically to object-oriented development. • Underlies the Unified Process (the methodology that uses UML). • Deals with abstraction, composition and decomposition, and style and aesthetics.

Kruchten’s Generic Model • Consists of five different views: – Logical or Structural (an object model of the design) – Process or Behavioral (addresses concurrency and synchronization) – Physical (mapping of software onto the hardware) – Development (how the software is organized by the development organization) – Scenarios (usage scenarios) • Note that this is missing an important view of the system—as a collection of algorithms interacting with data structures.

Kruchten’s Generic Model • Consists of five different views: – Logical or Structural (an object model of the design) – Process or Behavioral (addresses concurrency and synchronization) – Physical (mapping of software onto the hardware) – Development (how the software is organized by the development organization) – Scenarios (usage scenarios) • Note that this is missing an important view of the system—as a collection of algorithms interacting with data structures.

Logical (Structural) View • You present this in class and object diagrams. • You must produce written documentation as well. • Should stay at the architectural level— interfaces, collections of classes, and relationships. Try to avoid a complexity explosion in your class and object architecture. • Most classes should be defined during detailed design and be only documented in writing. • If you can paper your office with your class and object diagrams, you’ve gone too far.

Logical (Structural) View • You present this in class and object diagrams. • You must produce written documentation as well. • Should stay at the architectural level— interfaces, collections of classes, and relationships. Try to avoid a complexity explosion in your class and object architecture. • Most classes should be defined during detailed design and be only documented in writing. • If you can paper your office with your class and object diagrams, you’ve gone too far.

Process (Behavioral) View • The most important view, as it defines the system behavior. • Documented in a written overview and in the following diagrams: – – Sequence diagrams Collaboration diagrams Statechart diagrams Activity diagrams • Try to maintain a level of abstraction. That is, if you can paper your office with your diagrams, you’ve gone too far.

Process (Behavioral) View • The most important view, as it defines the system behavior. • Documented in a written overview and in the following diagrams: – – Sequence diagrams Collaboration diagrams Statechart diagrams Activity diagrams • Try to maintain a level of abstraction. That is, if you can paper your office with your diagrams, you’ve gone too far.

Physical (Environmental) View • Describes what software runs on what hardware. • Uses deployment diagrams • Relatively unimportant—basically a management tool. • Often documented without diagrams • Not required for your projects.

Physical (Environmental) View • Describes what software runs on what hardware. • Uses deployment diagrams • Relatively unimportant—basically a management tool. • Often documented without diagrams • Not required for your projects.

Development (Implementation) View • Static organization of the software in its development environment. • Uses component diagrams • Again a management tool • Usually handled using other notations: – For example, GANTT and PERT charts • Not required for your projects

Development (Implementation) View • Static organization of the software in its development environment. • Uses component diagrams • Again a management tool • Usually handled using other notations: – For example, GANTT and PERT charts • Not required for your projects

Scenarios (User) View • Describes how the system is used and how it is validated. • Can be diagrammed using Use Case Diagrams, but only if the system is driven by its user interface requirements. • Usually maintained as a textual list of scenarios. Often referred to as ‘threads’ or ‘strings’. • Treat as a summary of the functional requirements. • This view should be provided in some form for your projects.

Scenarios (User) View • Describes how the system is used and how it is validated. • Can be diagrammed using Use Case Diagrams, but only if the system is driven by its user interface requirements. • Usually maintained as a textual list of scenarios. Often referred to as ‘threads’ or ‘strings’. • Treat as a summary of the functional requirements. • This view should be provided in some form for your projects.

New in UML 2 • Goals: – To make the modeling language more executable – To provide more robust mechanisms for modeling workflow and actions – To create a standard for communication between tools – To reconcile UML to the standard OMF modeling framework

New in UML 2 • Goals: – To make the modeling language more executable – To provide more robust mechanisms for modeling workflow and actions – To create a standard for communication between tools – To reconcile UML to the standard OMF modeling framework

Specific Changes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Support to component-based development Support fuller modeling of component execution Standard language-specific profiles/extensions. Automated implementation of common patterns. Enhance UML for run-time architecture Improve state machines Improve activity graphs Composition of interaction mechanisms

Specific Changes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Support to component-based development Support fuller modeling of component execution Standard language-specific profiles/extensions. Automated implementation of common patterns. Enhance UML for run-time architecture Improve state machines Improve activity graphs Composition of interaction mechanisms

Use Case Changes • It is now easier to integrate use cases with other elements in the model • Use cases can be implemented by interactions (how the system supports the use case) and scenarios (execution paths through the system). • Interactions are documented by sequence diagrams, communication diagrams, and activity diagrams. • Scenarios are documented by sequence diagrams, composite structures, and activity diagrams.

Use Case Changes • It is now easier to integrate use cases with other elements in the model • Use cases can be implemented by interactions (how the system supports the use case) and scenarios (execution paths through the system). • Interactions are documented by sequence diagrams, communication diagrams, and activity diagrams. • Scenarios are documented by sequence diagrams, composite structures, and activity diagrams.

Class and Object Diagram Changes • Different types of generalizations are now supported. • Ball and socket notation for required interfaces. • Port notation to show environmental dependencies and links to internal behavior. • Composite structure diagrams defined, showing class hierarchies and collaborative patterns. • Templates supported (already in UML 1)

Class and Object Diagram Changes • Different types of generalizations are now supported. • Ball and socket notation for required interfaces. • Port notation to show environmental dependencies and links to internal behavior. • Composite structure diagrams defined, showing class hierarchies and collaborative patterns. • Templates supported (already in UML 1)

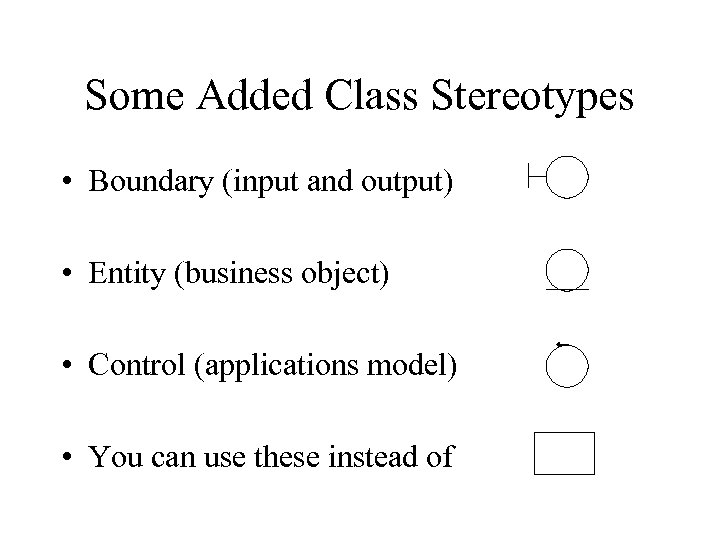

Some Added Class Stereotypes • Boundary (input and output) • Entity (business object) • Control (applications model) • You can use these instead of

Some Added Class Stereotypes • Boundary (input and output) • Entity (business object) • Control (applications model) • You can use these instead of

Behavior Changes • Collaboration diagrams have been renamed as ‘communication’ diagrams. State chart diagrams as ‘state machine diagrams’. • Local pre- and post-conditions on activities. • Activity diagrams now are two-dimensional and provide the features of Petri nets. Can model operations, classes, use cases, and workflows. • More detail in the sequence diagrams that show a set of objects interact. ‘Interaction frames’ allow you to represent software structure. Interaction overviews are like flow charts.

Behavior Changes • Collaboration diagrams have been renamed as ‘communication’ diagrams. State chart diagrams as ‘state machine diagrams’. • Local pre- and post-conditions on activities. • Activity diagrams now are two-dimensional and provide the features of Petri nets. Can model operations, classes, use cases, and workflows. • More detail in the sequence diagrams that show a set of objects interact. ‘Interaction frames’ allow you to represent software structure. Interaction overviews are like flow charts.

Advanced Dynamic Modeling • Addresses real-time issues: – – – Timeliness Reactive programming Concurrent processes Very high reliability, fault-tolerance, and performance Non-deterministic sequencing • Activity diagrams are used. Flow through the system is represented by tokens (a la Petri nets). • Goal was to support Model-Driven Architecture (MDA), but hasn’t excited the MDA community.

Advanced Dynamic Modeling • Addresses real-time issues: – – – Timeliness Reactive programming Concurrent processes Very high reliability, fault-tolerance, and performance Non-deterministic sequencing • Activity diagrams are used. Flow through the system is represented by tokens (a la Petri nets). • Goal was to support Model-Driven Architecture (MDA), but hasn’t excited the MDA community.

Subsystems • Replaced by components – <

Subsystems • Replaced by components – <

Some Random Thoughts • Although I teach O-O analysis and design, I find none of the published methods compelling, and I do not use them in my own work. • When I attempt to use them, I find myself in medias res, with a complexity explosion. • I would like to see the improvements listed on the next slide. Hopefully, UML 2 addresses some of these.

Some Random Thoughts • Although I teach O-O analysis and design, I find none of the published methods compelling, and I do not use them in my own work. • When I attempt to use them, I find myself in medias res, with a complexity explosion. • I would like to see the improvements listed on the next slide. Hopefully, UML 2 addresses some of these.

Areas for Improvement • Greater emphasis on algorithms and data structures, • Better compatibility with generic programming, • Better management of complexity through judicious abstraction to the subsystem level, • Provision for policies (i. e. , architectural patterns), • Provision for modeling complex or continuous behavior, and • Greater support for the use of design patterns that may not correspond directly to the structure of the system requirements. • UML 2 still doesn’t address some of these areas—e. g. , data.

Areas for Improvement • Greater emphasis on algorithms and data structures, • Better compatibility with generic programming, • Better management of complexity through judicious abstraction to the subsystem level, • Provision for policies (i. e. , architectural patterns), • Provision for modeling complex or continuous behavior, and • Greater support for the use of design patterns that may not correspond directly to the structure of the system requirements. • UML 2 still doesn’t address some of these areas—e. g. , data.

My Recommended Approach • Start with the use cases, but don’t bother with diagrams. • Base the process view on the use cases. Begin with sequence or activity diagrams. Eventually develop communication diagrams for each scenario. • Use the communication diagrams to work out the logical view of the system. Don’t get over-detailed. • Iterate by doing the following: – – – Impose a common architectural style (top-level solutions) Impose policies (architectural patterns) Impose design patterns Identify algorithms and data structures Translate quality requirements into functionality • ‘Lather, rinse, and repeat’ until done. Drill down as necessary. • You’re done when you know how to build the system.

My Recommended Approach • Start with the use cases, but don’t bother with diagrams. • Base the process view on the use cases. Begin with sequence or activity diagrams. Eventually develop communication diagrams for each scenario. • Use the communication diagrams to work out the logical view of the system. Don’t get over-detailed. • Iterate by doing the following: – – – Impose a common architectural style (top-level solutions) Impose policies (architectural patterns) Impose design patterns Identify algorithms and data structures Translate quality requirements into functionality • ‘Lather, rinse, and repeat’ until done. Drill down as necessary. • You’re done when you know how to build the system.