1a61d5d45d9482e606be42f541f93dc9.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 96

The Transit Method: Results from the Ground I. Results from individual transit search programs II. The Mass-Radius relationships (internal structure) Global Properties III. The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect (Spectroscopic Transits)

The Transit Method: Results from the Ground I. Results from individual transit search programs II. The Mass-Radius relationships (internal structure) Global Properties III. The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect (Spectroscopic Transits)

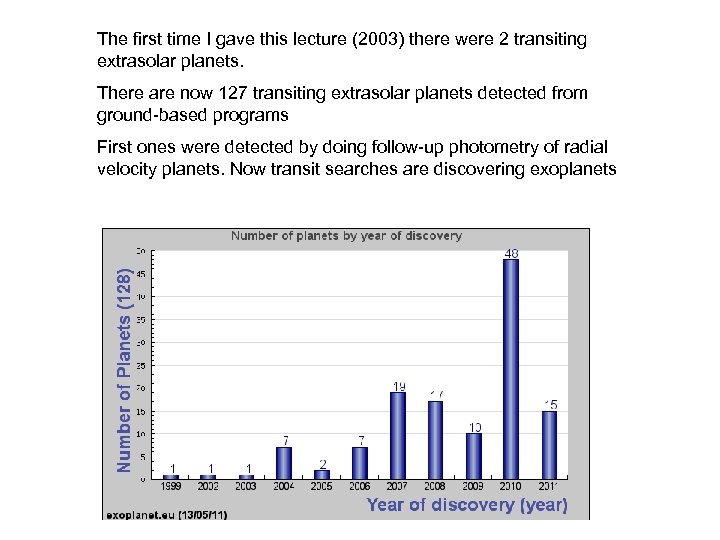

The first time I gave this lecture (2003) there were 2 transiting extrasolar planets. There are now 127 transiting extrasolar planets detected from ground-based programs First ones were detected by doing follow-up photometry of radial velocity planets. Now transit searches are discovering exoplanets

The first time I gave this lecture (2003) there were 2 transiting extrasolar planets. There are now 127 transiting extrasolar planets detected from ground-based programs First ones were detected by doing follow-up photometry of radial velocity planets. Now transit searches are discovering exoplanets

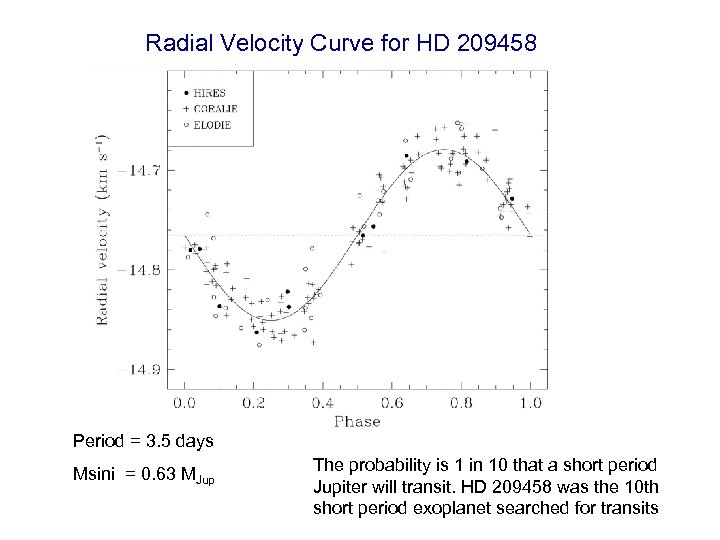

Radial Velocity Curve for HD 209458 Period = 3. 5 days Msini = 0. 63 MJup The probability is 1 in 10 that a short period Jupiter will transit. HD 209458 was the 10 th short period exoplanet searched for transits

Radial Velocity Curve for HD 209458 Period = 3. 5 days Msini = 0. 63 MJup The probability is 1 in 10 that a short period Jupiter will transit. HD 209458 was the 10 th short period exoplanet searched for transits

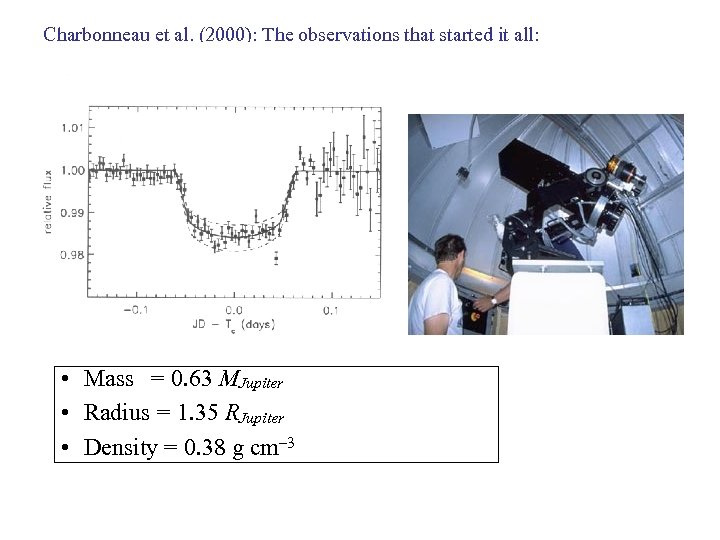

Charbonneau et al. (2000): The observations that started it all: • Mass = 0. 63 MJupiter • Radius = 1. 35 RJupiter • Density = 0. 38 g cm– 3

Charbonneau et al. (2000): The observations that started it all: • Mass = 0. 63 MJupiter • Radius = 1. 35 RJupiter • Density = 0. 38 g cm– 3

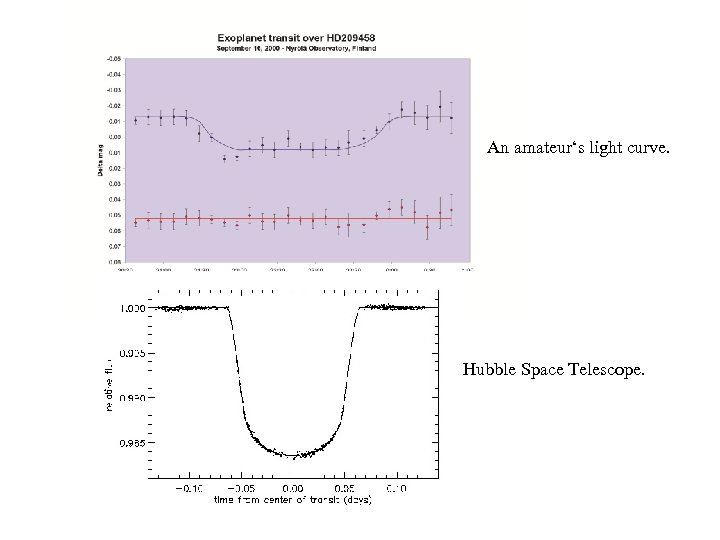

An amateur‘s light curve. Hubble Space Telescope.

An amateur‘s light curve. Hubble Space Telescope.

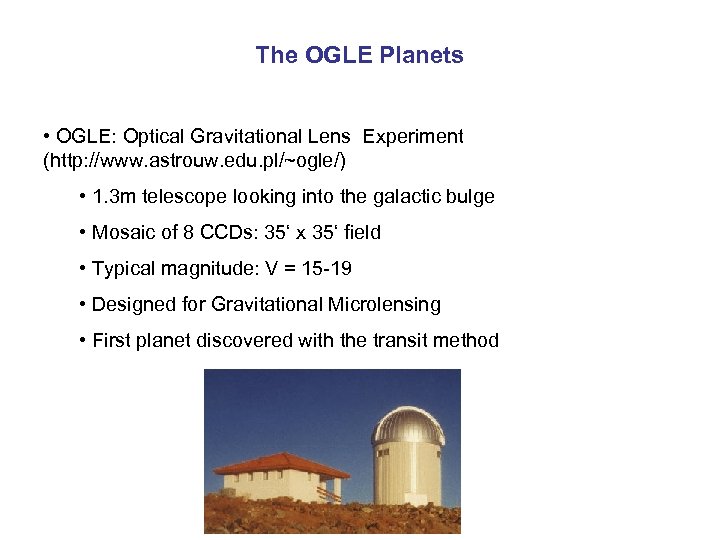

The OGLE Planets • OGLE: Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment (http: //www. astrouw. edu. pl/~ogle/) • 1. 3 m telescope looking into the galactic bulge • Mosaic of 8 CCDs: 35‘ x 35‘ field • Typical magnitude: V = 15 -19 • Designed for Gravitational Microlensing • First planet discovered with the transit method

The OGLE Planets • OGLE: Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment (http: //www. astrouw. edu. pl/~ogle/) • 1. 3 m telescope looking into the galactic bulge • Mosaic of 8 CCDs: 35‘ x 35‘ field • Typical magnitude: V = 15 -19 • Designed for Gravitational Microlensing • First planet discovered with the transit method

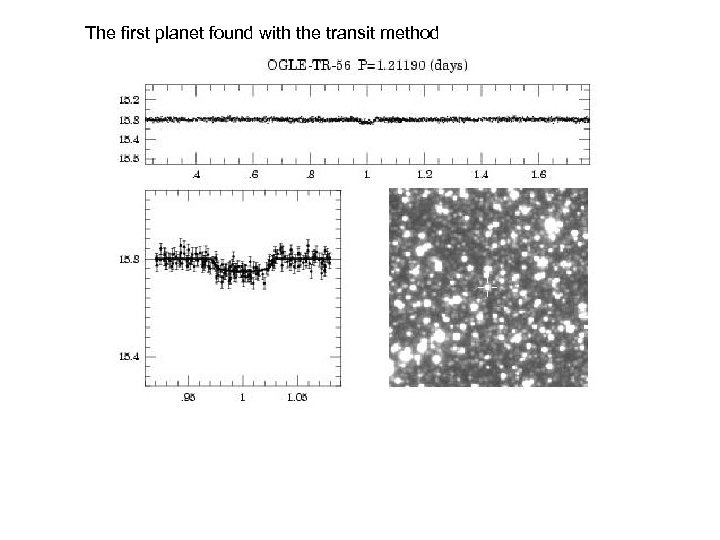

The first planet found with the transit method

The first planet found with the transit method

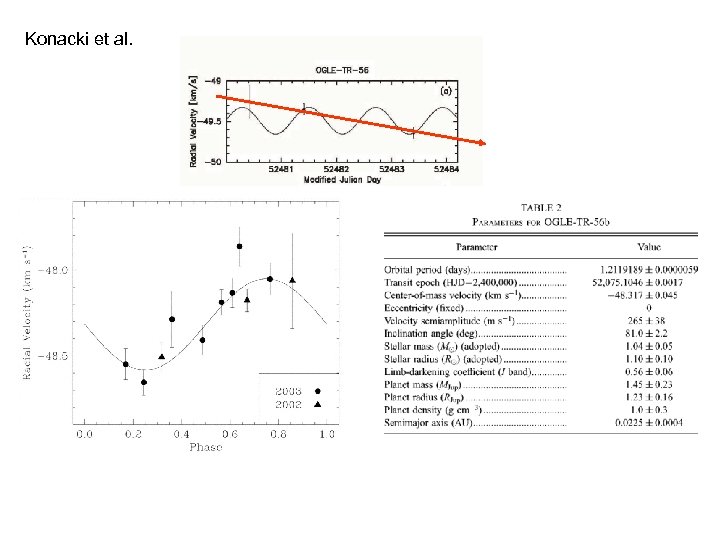

Konacki et al.

Konacki et al.

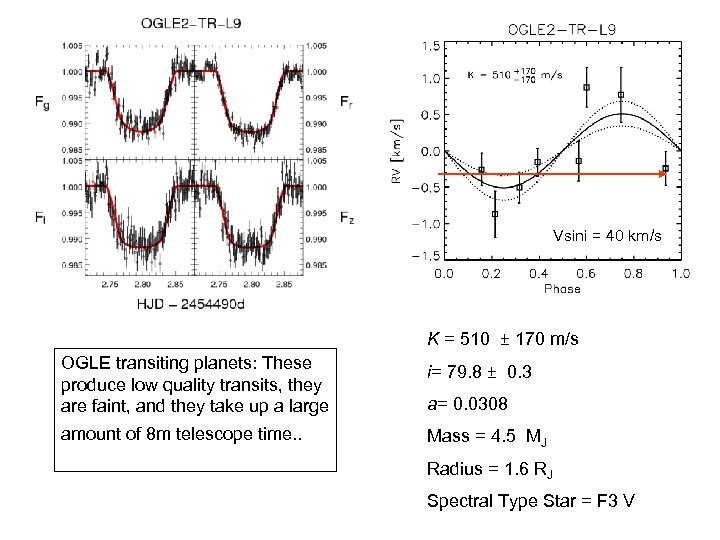

Vsini = 40 km/s K = 510 ± 170 m/s OGLE transiting planets: These produce low quality transits, they are faint, and they take up a large i= 79. 8 ± 0. 3 amount of 8 m telescope time. . Mass = 4. 5 MJ a= 0. 0308 Radius = 1. 6 RJ Spectral Type Star = F 3 V

Vsini = 40 km/s K = 510 ± 170 m/s OGLE transiting planets: These produce low quality transits, they are faint, and they take up a large i= 79. 8 ± 0. 3 amount of 8 m telescope time. . Mass = 4. 5 MJ a= 0. 0308 Radius = 1. 6 RJ Spectral Type Star = F 3 V

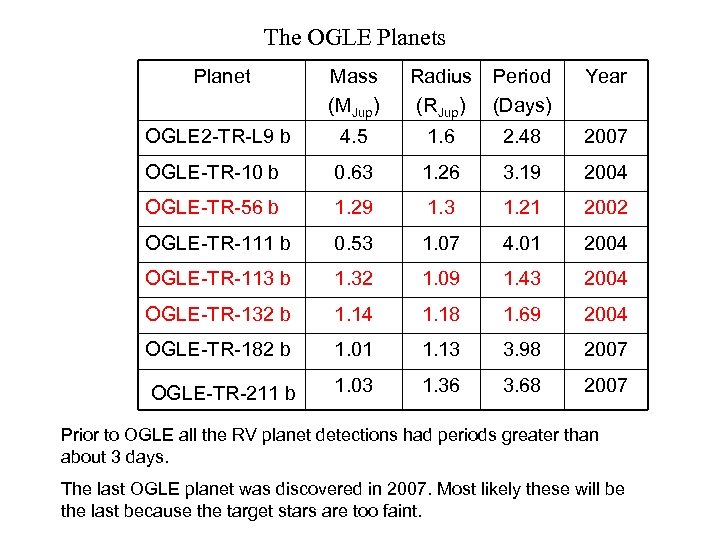

The OGLE Planets Planet Mass (MJup) Radius (RJup) Period (Days) Year OGLE 2 -TR-L 9 b 4. 5 1. 6 2. 48 2007 OGLE-TR-10 b 0. 63 1. 26 3. 19 2004 OGLE-TR-56 b 1. 29 1. 3 1. 21 2002 OGLE-TR-111 b 0. 53 1. 07 4. 01 2004 OGLE-TR-113 b 1. 32 1. 09 1. 43 2004 OGLE-TR-132 b 1. 14 1. 18 1. 69 2004 OGLE-TR-182 b 1. 01 1. 13 3. 98 2007 OGLE-TR-211 b 1. 03 1. 36 3. 68 2007 Prior to OGLE all the RV planet detections had periods greater than about 3 days. The last OGLE planet was discovered in 2007. Most likely these will be the last because the target stars are too faint.

The OGLE Planets Planet Mass (MJup) Radius (RJup) Period (Days) Year OGLE 2 -TR-L 9 b 4. 5 1. 6 2. 48 2007 OGLE-TR-10 b 0. 63 1. 26 3. 19 2004 OGLE-TR-56 b 1. 29 1. 3 1. 21 2002 OGLE-TR-111 b 0. 53 1. 07 4. 01 2004 OGLE-TR-113 b 1. 32 1. 09 1. 43 2004 OGLE-TR-132 b 1. 14 1. 18 1. 69 2004 OGLE-TR-182 b 1. 01 1. 13 3. 98 2007 OGLE-TR-211 b 1. 03 1. 36 3. 68 2007 Prior to OGLE all the RV planet detections had periods greater than about 3 days. The last OGLE planet was discovered in 2007. Most likely these will be the last because the target stars are too faint.

The Tr. ES Planets • Tr. ES: Trans-atlantic Exoplanet Survey (STARE is a member of the network http: //www. hao. ucar. edu/public/research/stare/) • Three 10 cm telescopes located at Lowell Observtory, Mount Palomar and the Canary Islands • 6. 9 square degrees • 5 Planets discovered

The Tr. ES Planets • Tr. ES: Trans-atlantic Exoplanet Survey (STARE is a member of the network http: //www. hao. ucar. edu/public/research/stare/) • Three 10 cm telescopes located at Lowell Observtory, Mount Palomar and the Canary Islands • 6. 9 square degrees • 5 Planets discovered

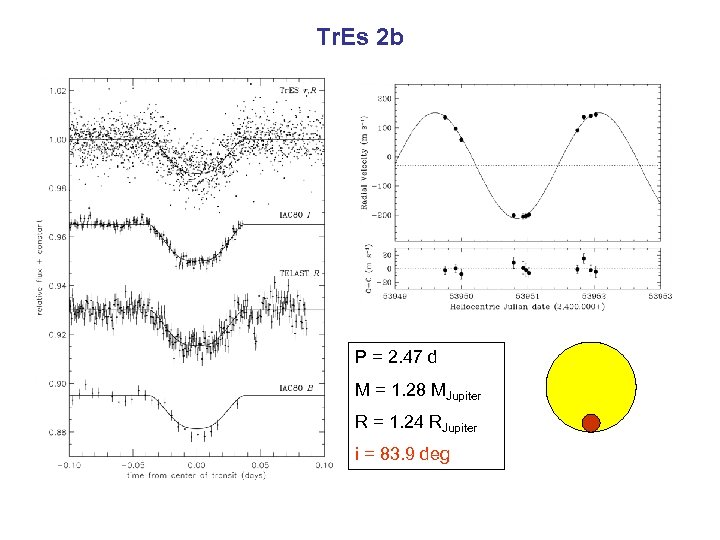

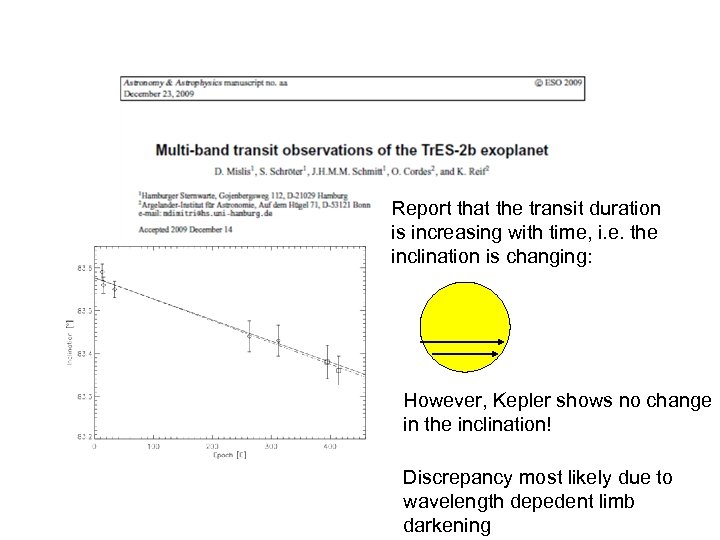

Tr. Es 2 b P = 2. 47 d M = 1. 28 MJupiter R = 1. 24 RJupiter i = 83. 9 deg

Tr. Es 2 b P = 2. 47 d M = 1. 28 MJupiter R = 1. 24 RJupiter i = 83. 9 deg

Report that the transit duration is increasing with time, i. e. the inclination is changing: However, Kepler shows no change in the inclination! Discrepancy most likely due to wavelength depedent limb darkening

Report that the transit duration is increasing with time, i. e. the inclination is changing: However, Kepler shows no change in the inclination! Discrepancy most likely due to wavelength depedent limb darkening

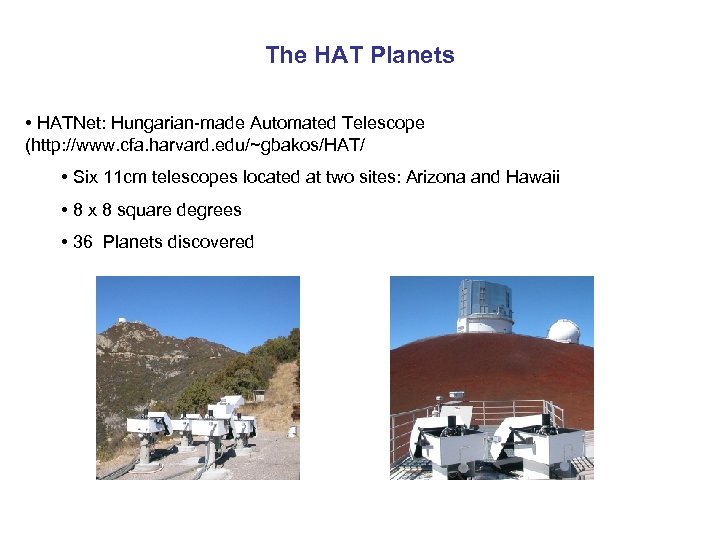

The HAT Planets • HATNet: Hungarian-made Automated Telescope (http: //www. cfa. harvard. edu/~gbakos/HAT/ • Six 11 cm telescopes located at two sites: Arizona and Hawaii • 8 x 8 square degrees • 36 Planets discovered

The HAT Planets • HATNet: Hungarian-made Automated Telescope (http: //www. cfa. harvard. edu/~gbakos/HAT/ • Six 11 cm telescopes located at two sites: Arizona and Hawaii • 8 x 8 square degrees • 36 Planets discovered

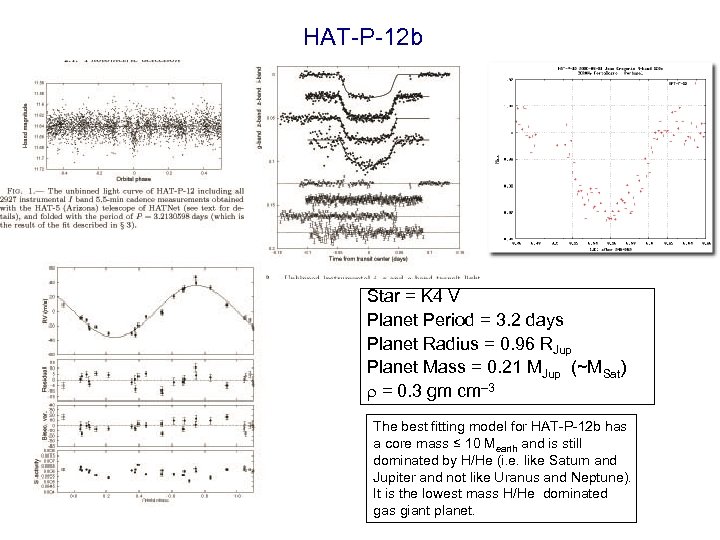

HAT-P-12 b Star = K 4 V Planet Period = 3. 2 days Planet Radius = 0. 96 RJup Planet Mass = 0. 21 MJup (~MSat) r = 0. 3 gm cm– 3 The best fitting model for HAT-P-12 b has a core mass ≤ 10 Mearth and is still dominated by H/He (i. e. like Saturn and Jupiter and not like Uranus and Neptune). It is the lowest mass H/He dominated gas giant planet.

HAT-P-12 b Star = K 4 V Planet Period = 3. 2 days Planet Radius = 0. 96 RJup Planet Mass = 0. 21 MJup (~MSat) r = 0. 3 gm cm– 3 The best fitting model for HAT-P-12 b has a core mass ≤ 10 Mearth and is still dominated by H/He (i. e. like Saturn and Jupiter and not like Uranus and Neptune). It is the lowest mass H/He dominated gas giant planet.

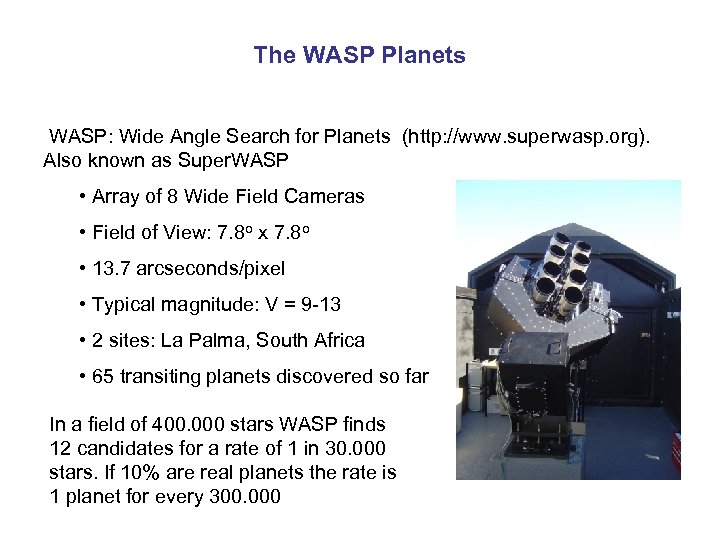

The WASP Planets WASP: Wide Angle Search for Planets (http: //www. superwasp. org). Also known as Super. WASP • Array of 8 Wide Field Cameras • Field of View: 7. 8 o x 7. 8 o • 13. 7 arcseconds/pixel • Typical magnitude: V = 9 -13 • 2 sites: La Palma, South Africa • 65 transiting planets discovered so far In a field of 400. 000 stars WASP finds 12 candidates for a rate of 1 in 30. 000 stars. If 10% are real planets the rate is 1 planet for every 300. 000

The WASP Planets WASP: Wide Angle Search for Planets (http: //www. superwasp. org). Also known as Super. WASP • Array of 8 Wide Field Cameras • Field of View: 7. 8 o x 7. 8 o • 13. 7 arcseconds/pixel • Typical magnitude: V = 9 -13 • 2 sites: La Palma, South Africa • 65 transiting planets discovered so far In a field of 400. 000 stars WASP finds 12 candidates for a rate of 1 in 30. 000 stars. If 10% are real planets the rate is 1 planet for every 300. 000

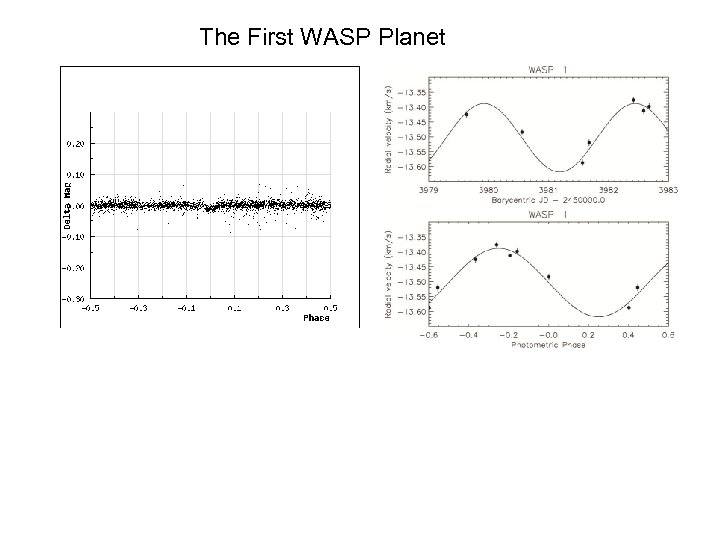

The First WASP Planet

The First WASP Planet

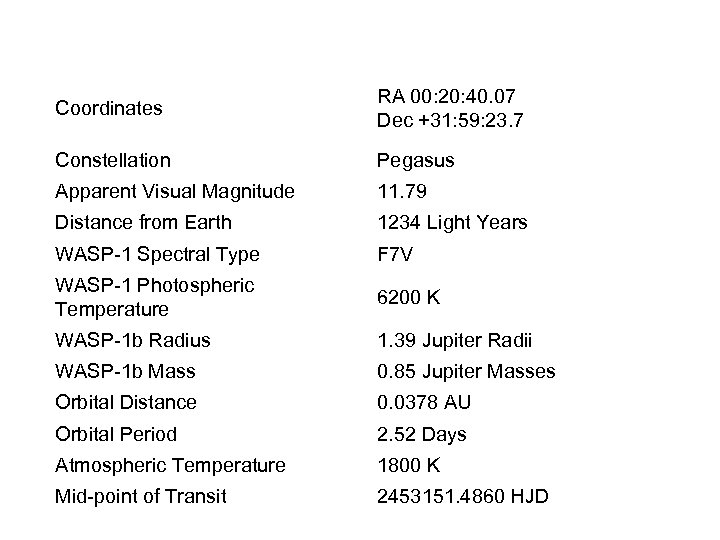

Coordinates RA 00: 20: 40. 07 Dec +31: 59: 23. 7 Constellation Pegasus Apparent Visual Magnitude 11. 79 Distance from Earth 1234 Light Years WASP-1 Spectral Type F 7 V WASP-1 Photospheric Temperature 6200 K WASP-1 b Radius 1. 39 Jupiter Radii WASP-1 b Mass 0. 85 Jupiter Masses Orbital Distance 0. 0378 AU Orbital Period 2. 52 Days Atmospheric Temperature 1800 K Mid-point of Transit 2453151. 4860 HJD

Coordinates RA 00: 20: 40. 07 Dec +31: 59: 23. 7 Constellation Pegasus Apparent Visual Magnitude 11. 79 Distance from Earth 1234 Light Years WASP-1 Spectral Type F 7 V WASP-1 Photospheric Temperature 6200 K WASP-1 b Radius 1. 39 Jupiter Radii WASP-1 b Mass 0. 85 Jupiter Masses Orbital Distance 0. 0378 AU Orbital Period 2. 52 Days Atmospheric Temperature 1800 K Mid-point of Transit 2453151. 4860 HJD

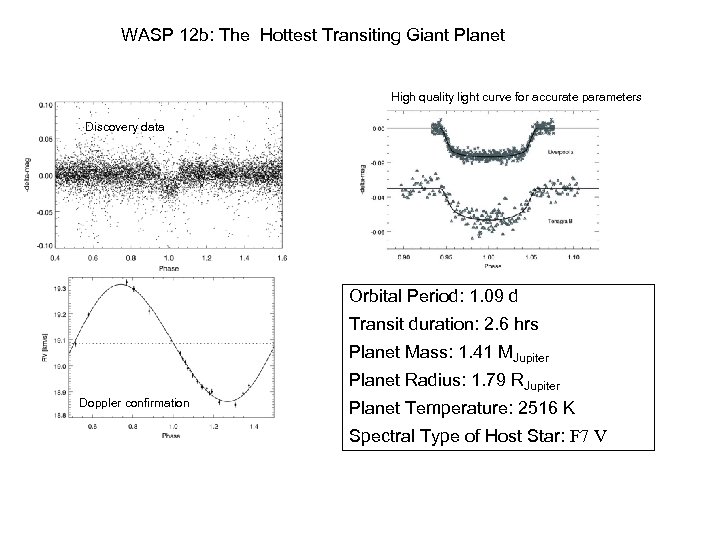

WASP 12 b: The Hottest Transiting Giant Planet High quality light curve for accurate parameters Discovery data Orbital Period: 1. 09 d Transit duration: 2. 6 hrs Planet Mass: 1. 41 MJupiter Planet Radius: 1. 79 RJupiter Doppler confirmation Planet Temperature: 2516 K Spectral Type of Host Star: F 7 V

WASP 12 b: The Hottest Transiting Giant Planet High quality light curve for accurate parameters Discovery data Orbital Period: 1. 09 d Transit duration: 2. 6 hrs Planet Mass: 1. 41 MJupiter Planet Radius: 1. 79 RJupiter Doppler confirmation Planet Temperature: 2516 K Spectral Type of Host Star: F 7 V

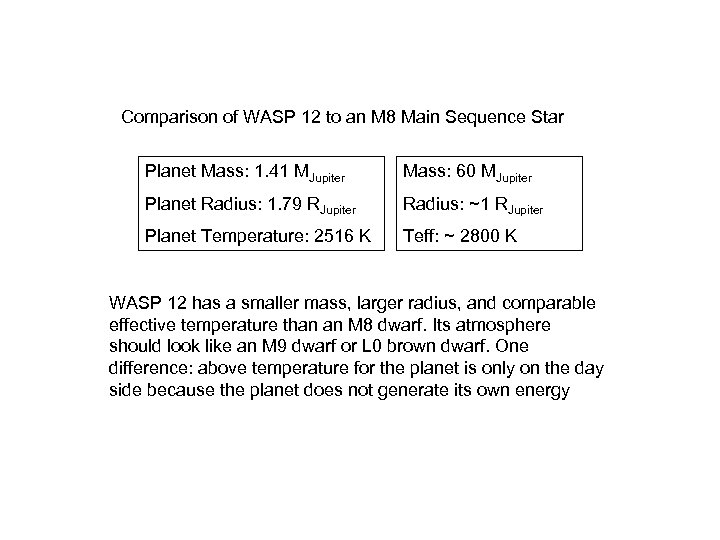

Comparison of WASP 12 to an M 8 Main Sequence Star Planet Mass: 1. 41 MJupiter Mass: 60 MJupiter Planet Radius: 1. 79 RJupiter Radius: ~1 RJupiter Planet Temperature: 2516 K Teff: ~ 2800 K WASP 12 has a smaller mass, larger radius, and comparable effective temperature than an M 8 dwarf. Its atmosphere should look like an M 9 dwarf or L 0 brown dwarf. One difference: above temperature for the planet is only on the day side because the planet does not generate its own energy

Comparison of WASP 12 to an M 8 Main Sequence Star Planet Mass: 1. 41 MJupiter Mass: 60 MJupiter Planet Radius: 1. 79 RJupiter Radius: ~1 RJupiter Planet Temperature: 2516 K Teff: ~ 2800 K WASP 12 has a smaller mass, larger radius, and comparable effective temperature than an M 8 dwarf. Its atmosphere should look like an M 9 dwarf or L 0 brown dwarf. One difference: above temperature for the planet is only on the day side because the planet does not generate its own energy

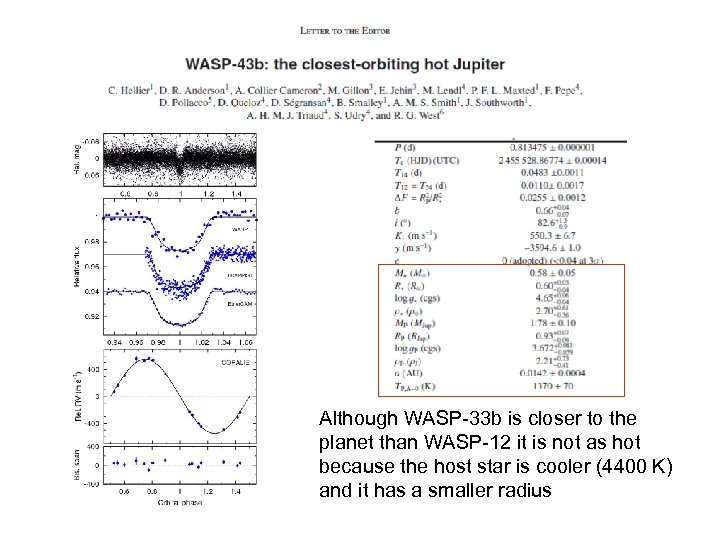

Although WASP-33 b is closer to the planet than WASP-12 it is not as hot because the host star is cooler (4400 K) and it has a smaller radius

Although WASP-33 b is closer to the planet than WASP-12 it is not as hot because the host star is cooler (4400 K) and it has a smaller radius

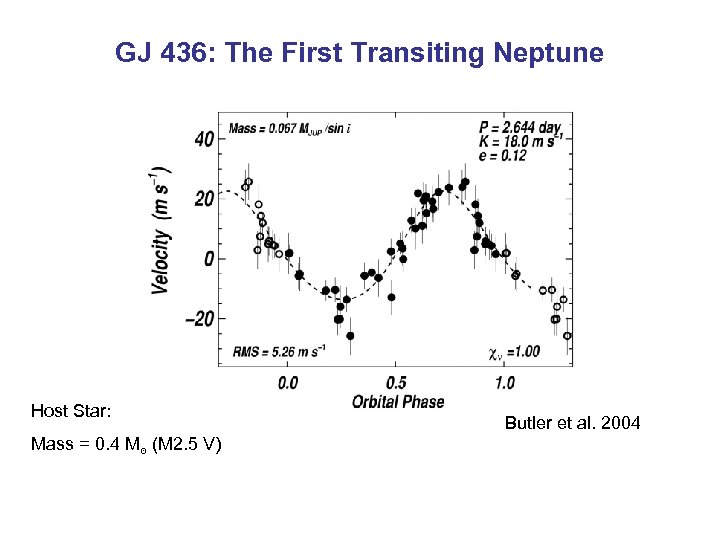

GJ 436: The First Transiting Neptune Host Star: Mass = 0. 4 M ( סּ M 2. 5 V) Butler et al. 2004

GJ 436: The First Transiting Neptune Host Star: Mass = 0. 4 M ( סּ M 2. 5 V) Butler et al. 2004

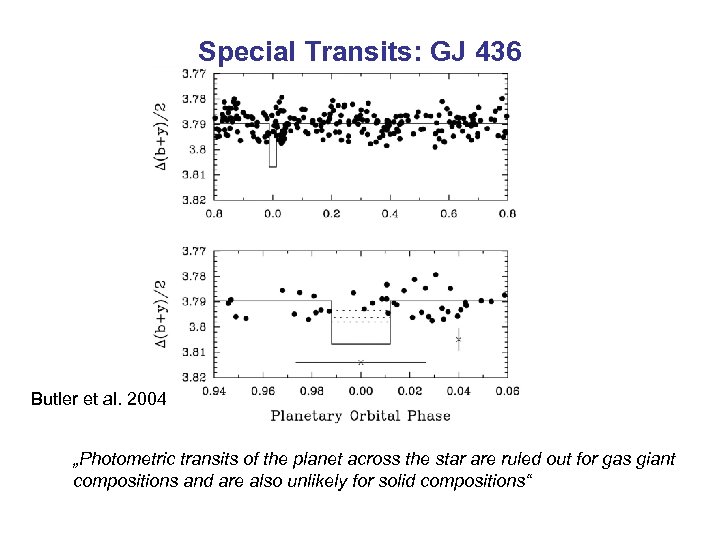

Special Transits: GJ 436 Butler et al. 2004 „Photometric transits of the planet across the star are ruled out for gas giant compositions and are also unlikely for solid compositions“

Special Transits: GJ 436 Butler et al. 2004 „Photometric transits of the planet across the star are ruled out for gas giant compositions and are also unlikely for solid compositions“

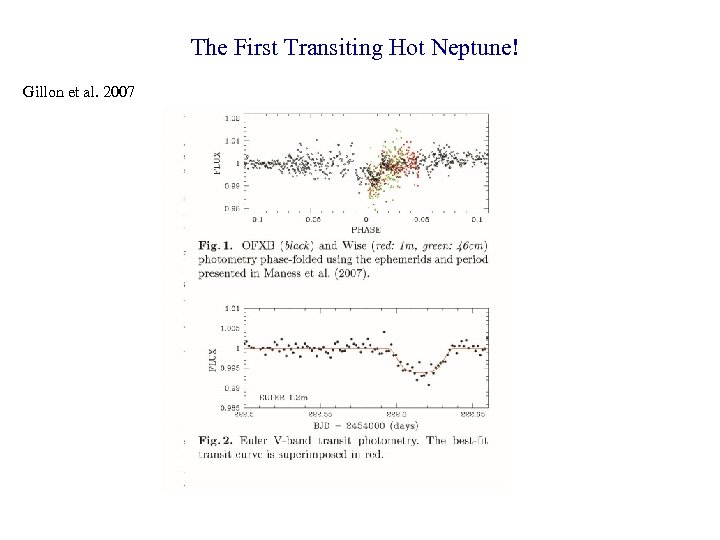

The First Transiting Hot Neptune! Gillon et al. 2007

The First Transiting Hot Neptune! Gillon et al. 2007

![GJ 436 Star Stellar mass [ M ] סּ 0. 44 ( ± 0. GJ 436 Star Stellar mass [ M ] סּ 0. 44 ( ± 0.](https://present5.com/presentation/1a61d5d45d9482e606be42f541f93dc9/image-25.jpg) GJ 436 Star Stellar mass [ M ] סּ 0. 44 ( ± 0. 04) Planet Period [days] 2. 64385 ± 0. 00009 Eccentricity 0. 16 ± 0. 02 Orbital inclination 86. 5 0. 2 Planet mass [ ME ] 22. 6 ± 1. 9 Planet radius [ RE ] 3. 95 +0. 41 -0. 28 Mean density = 1. 95 gm cm– 3, slightly higher than Neptune (1. 64)

GJ 436 Star Stellar mass [ M ] סּ 0. 44 ( ± 0. 04) Planet Period [days] 2. 64385 ± 0. 00009 Eccentricity 0. 16 ± 0. 02 Orbital inclination 86. 5 0. 2 Planet mass [ ME ] 22. 6 ± 1. 9 Planet radius [ RE ] 3. 95 +0. 41 -0. 28 Mean density = 1. 95 gm cm– 3, slightly higher than Neptune (1. 64)

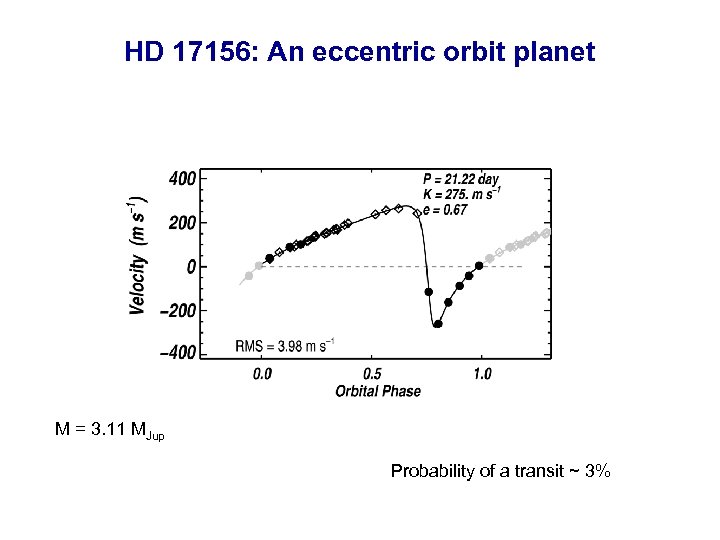

HD 17156: An eccentric orbit planet M = 3. 11 MJup Probability of a transit ~ 3%

HD 17156: An eccentric orbit planet M = 3. 11 MJup Probability of a transit ~ 3%

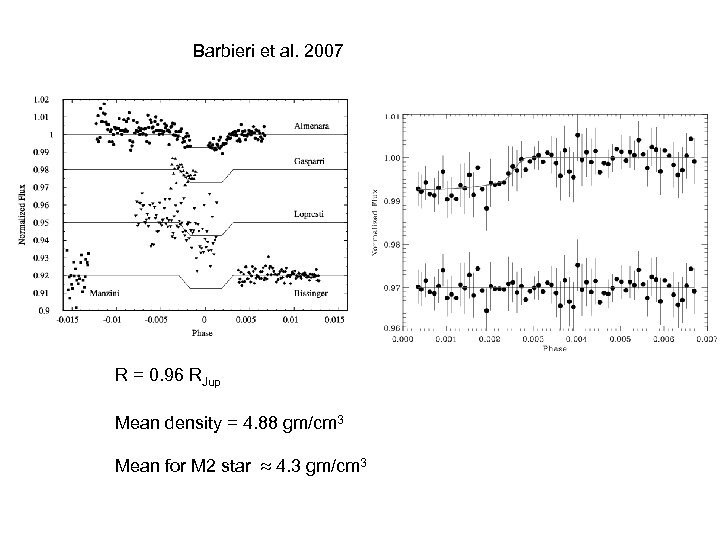

Barbieri et al. 2007 R = 0. 96 RJup Mean density = 4. 88 gm/cm 3 Mean for M 2 star ≈ 4. 3 gm/cm 3

Barbieri et al. 2007 R = 0. 96 RJup Mean density = 4. 88 gm/cm 3 Mean for M 2 star ≈ 4. 3 gm/cm 3

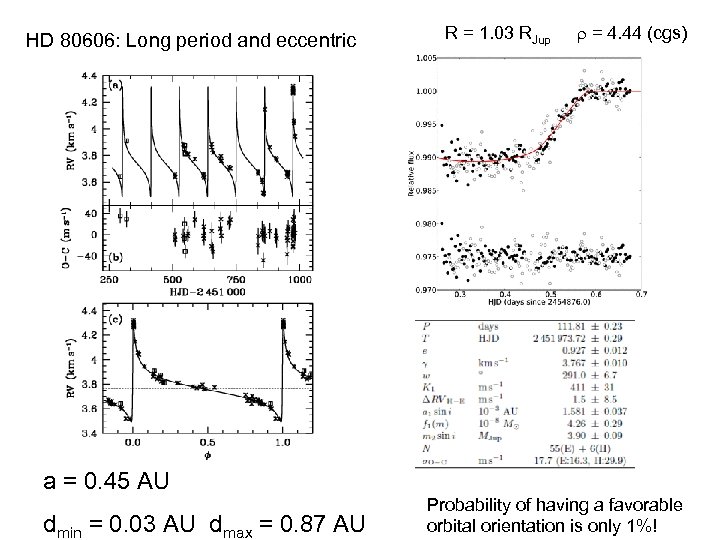

HD 80606: Long period and eccentric R = 1. 03 RJup r = 4. 44 (cgs) a = 0. 45 AU dmin = 0. 03 AU dmax = 0. 87 AU Probability of having a favorable orbital orientation is only 1%!

HD 80606: Long period and eccentric R = 1. 03 RJup r = 4. 44 (cgs) a = 0. 45 AU dmin = 0. 03 AU dmax = 0. 87 AU Probability of having a favorable orbital orientation is only 1%!

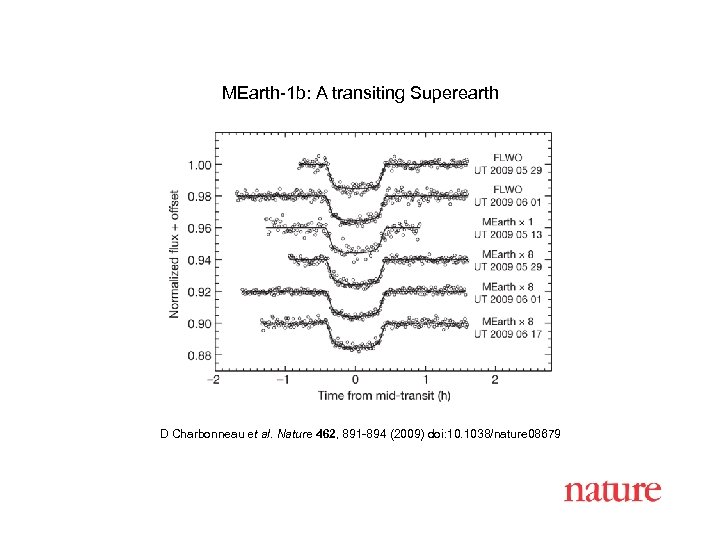

MEarth-1 b: A transiting Superearth D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679

MEarth-1 b: A transiting Superearth D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679

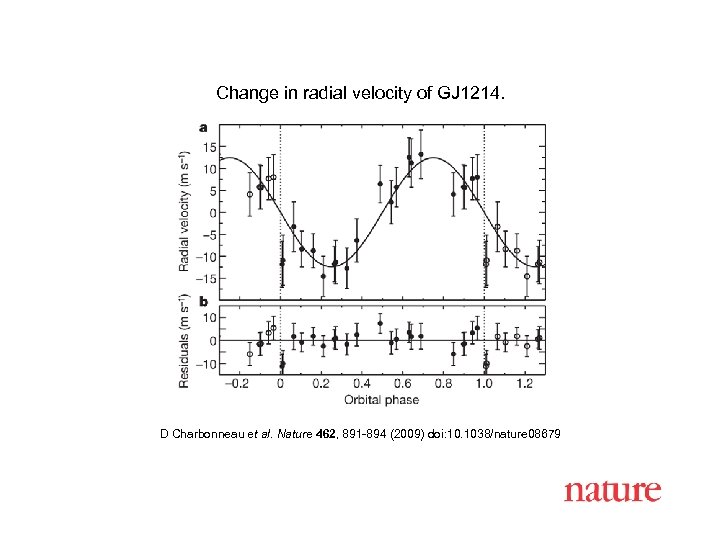

Change in radial velocity of GJ 1214. D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679

Change in radial velocity of GJ 1214. D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679

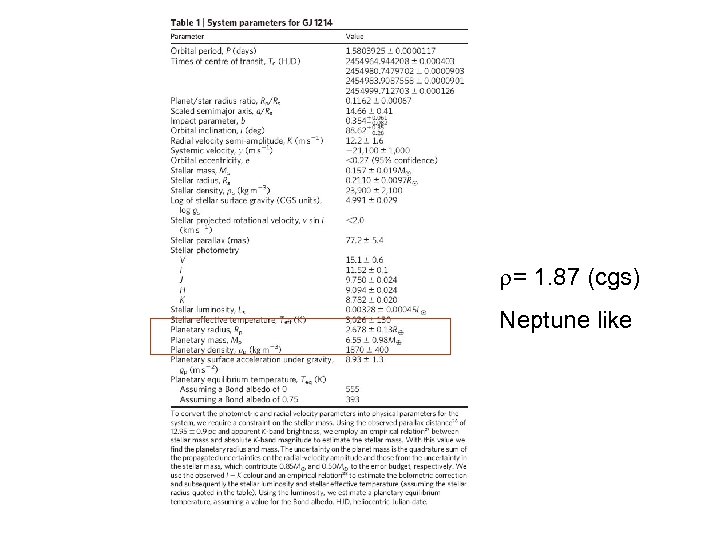

r= 1. 87 (cgs) Neptune like

r= 1. 87 (cgs) Neptune like

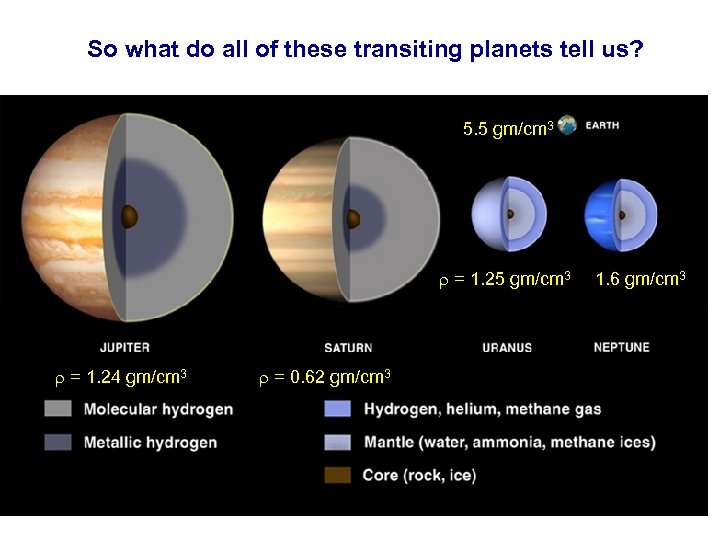

So what do all of these transiting planets tell us? 5. 5 gm/cm 3 r = 1. 24 gm/cm 3 r = 0. 62 gm/cm 3 1. 6 gm/cm 3

So what do all of these transiting planets tell us? 5. 5 gm/cm 3 r = 1. 24 gm/cm 3 r = 0. 62 gm/cm 3 1. 6 gm/cm 3

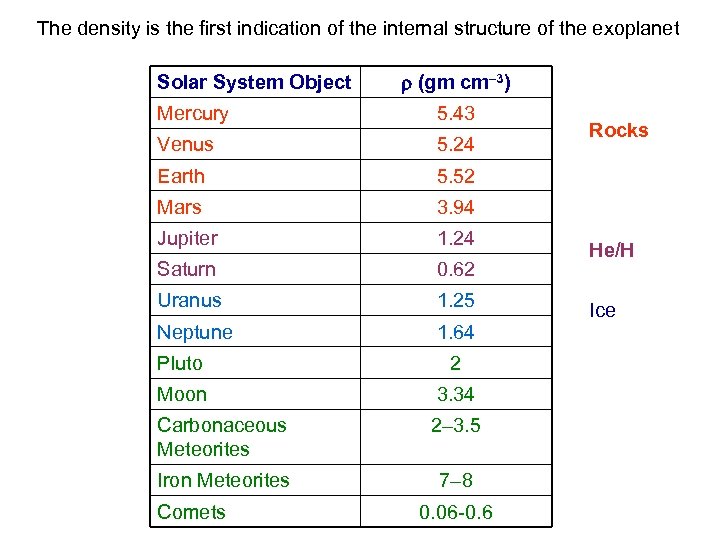

The density is the first indication of the internal structure of the exoplanet Solar System Object r (gm cm– 3) Mercury 5. 43 Venus 5. 24 Earth 5. 52 Mars 3. 94 Jupiter 1. 24 Saturn 0. 62 Uranus 1. 25 Neptune 1. 64 Pluto 2 Moon 3. 34 Carbonaceous Meteorites 2– 3. 5 Iron Meteorites 7– 8 Comets 0. 06 -0. 6 Rocks He/H Ice

The density is the first indication of the internal structure of the exoplanet Solar System Object r (gm cm– 3) Mercury 5. 43 Venus 5. 24 Earth 5. 52 Mars 3. 94 Jupiter 1. 24 Saturn 0. 62 Uranus 1. 25 Neptune 1. 64 Pluto 2 Moon 3. 34 Carbonaceous Meteorites 2– 3. 5 Iron Meteorites 7– 8 Comets 0. 06 -0. 6 Rocks He/H Ice

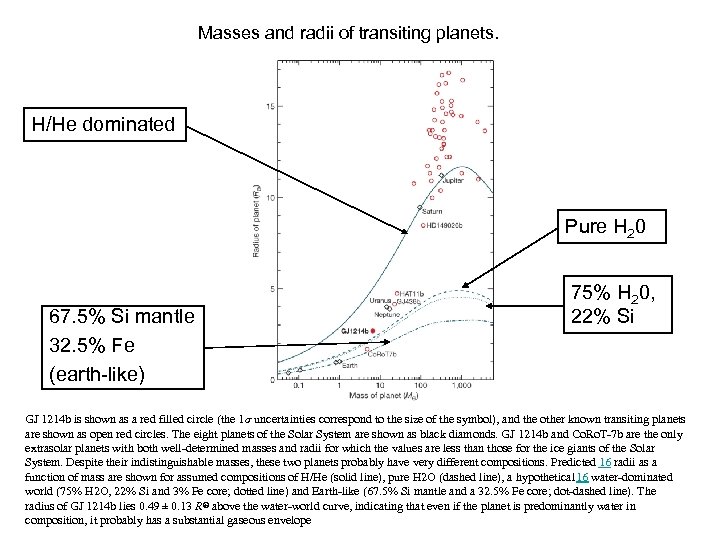

Masses and radii of transiting planets. H/He dominated Pure H 20 67. 5% Si mantle 32. 5% Fe (earth-like) 75% H 20, 22% Si GJ 1214 b is shown as a red filled circle (the 1σ uncertainties correspond to the size of the symbol), and the other known transiting planets are shown as open red circles. The eight planets of the Solar System are shown as black diamonds. GJ 1214 b and Co. Ro. T-7 b are the only extrasolar planets with both well-determined masses and radii for which the values are less than those for the ice giants of the Solar System. Despite their indistinguishable masses, these two planets probably have very different compositions. Predicted 16 radii as a function of mass are shown for assumed compositions of H/He (solid line), pure H 2 O (dashed line), a hypothetical 16 water-dominated world (75% H 2 O, 22% Si and 3% Fe core; dotted line) and Earth-like (67. 5% Si mantle and a 32. 5% Fe core; dot-dashed line). The radius of GJ 1214 b lies 0. 49 ± 0. 13 R⊕ above the water-world curve, indicating that even if the planet is predominantly water in D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679 composition, it probably has a substantial gaseous envelope

Masses and radii of transiting planets. H/He dominated Pure H 20 67. 5% Si mantle 32. 5% Fe (earth-like) 75% H 20, 22% Si GJ 1214 b is shown as a red filled circle (the 1σ uncertainties correspond to the size of the symbol), and the other known transiting planets are shown as open red circles. The eight planets of the Solar System are shown as black diamonds. GJ 1214 b and Co. Ro. T-7 b are the only extrasolar planets with both well-determined masses and radii for which the values are less than those for the ice giants of the Solar System. Despite their indistinguishable masses, these two planets probably have very different compositions. Predicted 16 radii as a function of mass are shown for assumed compositions of H/He (solid line), pure H 2 O (dashed line), a hypothetical 16 water-dominated world (75% H 2 O, 22% Si and 3% Fe core; dotted line) and Earth-like (67. 5% Si mantle and a 32. 5% Fe core; dot-dashed line). The radius of GJ 1214 b lies 0. 49 ± 0. 13 R⊕ above the water-world curve, indicating that even if the planet is predominantly water in D Charbonneau et al. Nature 462, 891 -894 (2009) doi: 10. 1038/nature 08679 composition, it probably has a substantial gaseous envelope

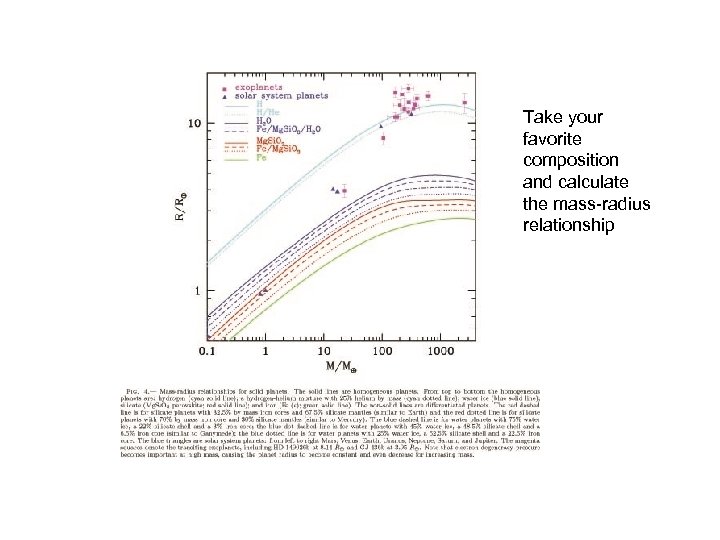

Take your favorite composition and calculate the mass-radius relationship

Take your favorite composition and calculate the mass-radius relationship

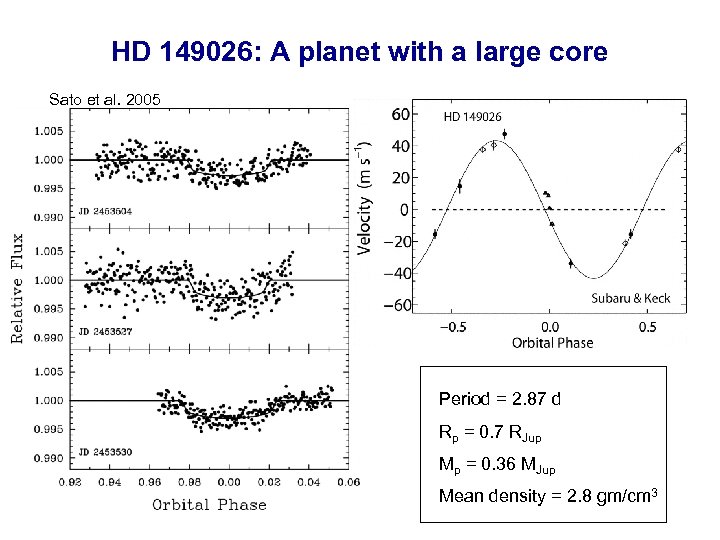

HD 149026: A planet with a large core Sato et al. 2005 Period = 2. 87 d Rp = 0. 7 RJup Mp = 0. 36 MJup Mean density = 2. 8 gm/cm 3

HD 149026: A planet with a large core Sato et al. 2005 Period = 2. 87 d Rp = 0. 7 RJup Mp = 0. 36 MJup Mean density = 2. 8 gm/cm 3

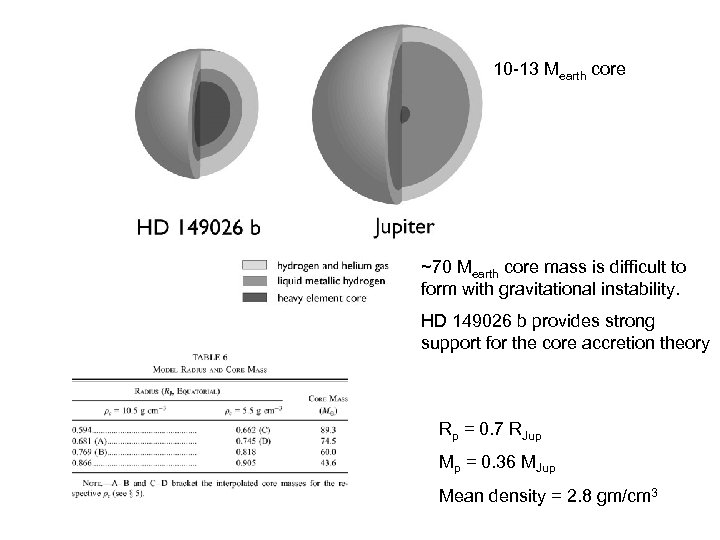

10 -13 Mearth core ~70 Mearth core mass is difficult to form with gravitational instability. HD 149026 b provides strong support for the core accretion theory Rp = 0. 7 RJup Mp = 0. 36 MJup Mean density = 2. 8 gm/cm 3

10 -13 Mearth core ~70 Mearth core mass is difficult to form with gravitational instability. HD 149026 b provides strong support for the core accretion theory Rp = 0. 7 RJup Mp = 0. 36 MJup Mean density = 2. 8 gm/cm 3

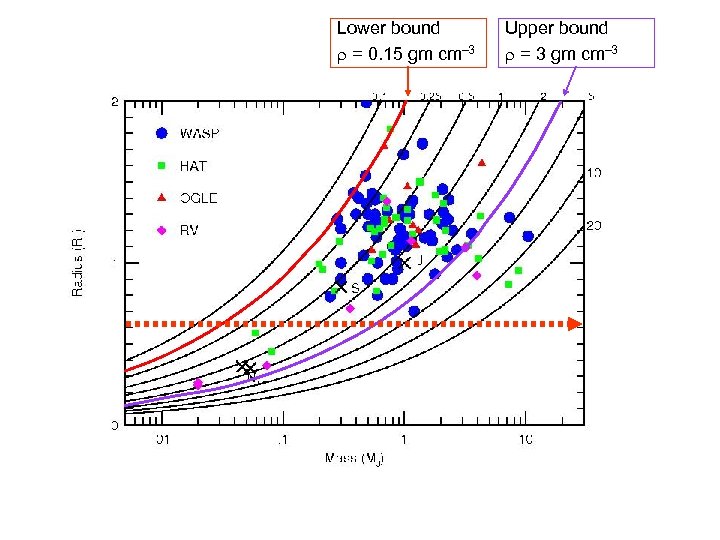

Lower bound r = 0. 15 gm cm– 3 Upper bound r = 3 gm cm– 3

Lower bound r = 0. 15 gm cm– 3 Upper bound r = 3 gm cm– 3

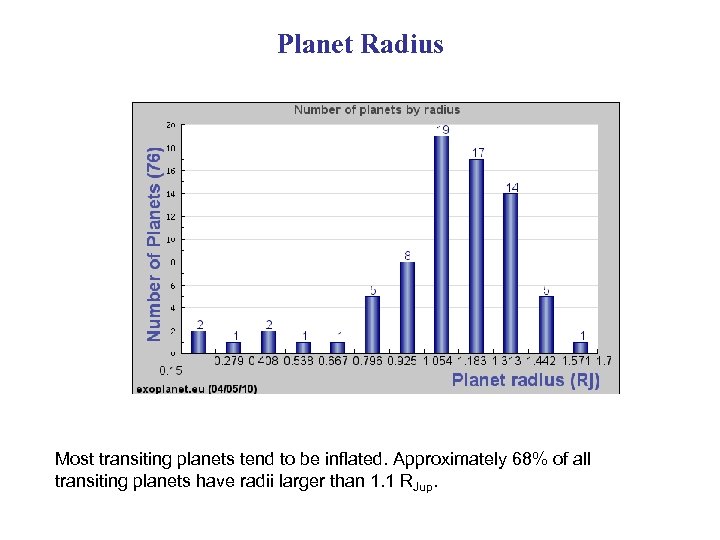

Planet Radius Most transiting planets tend to be inflated. Approximately 68% of all transiting planets have radii larger than 1. 1 RJup.

Planet Radius Most transiting planets tend to be inflated. Approximately 68% of all transiting planets have radii larger than 1. 1 RJup.

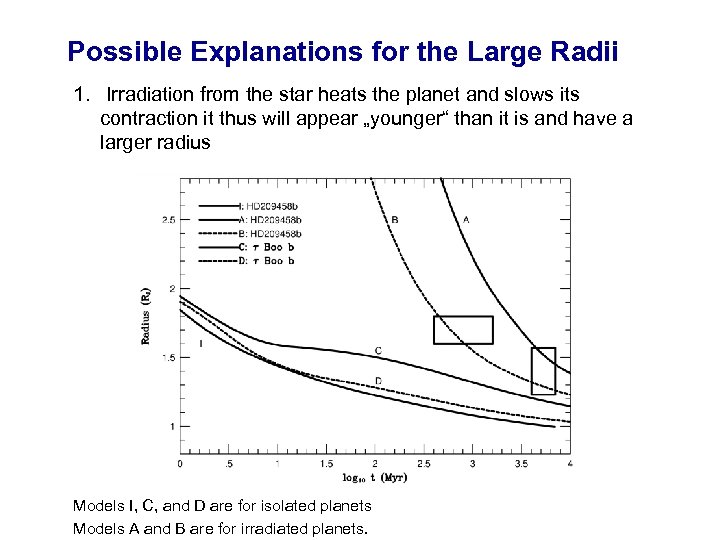

Possible Explanations for the Large Radii 1. Irradiation from the star heats the planet and slows its contraction it thus will appear „younger“ than it is and have a larger radius Models I, C, and D are for isolated planets Models A and B are for irradiated planets.

Possible Explanations for the Large Radii 1. Irradiation from the star heats the planet and slows its contraction it thus will appear „younger“ than it is and have a larger radius Models I, C, and D are for isolated planets Models A and B are for irradiated planets.

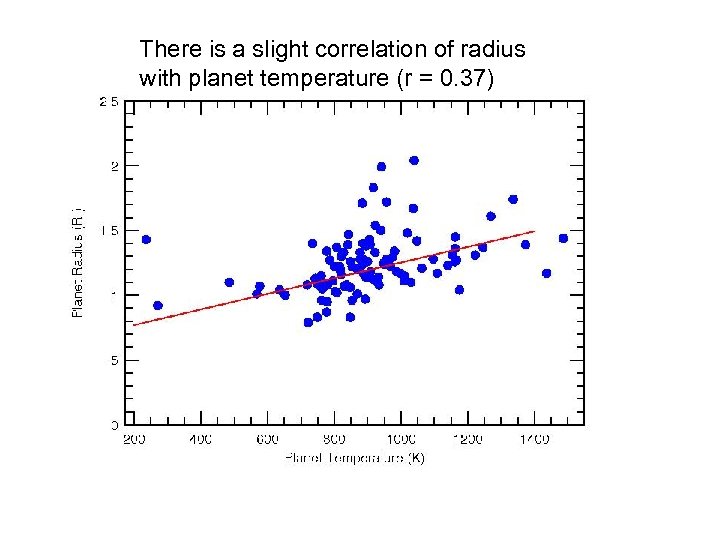

There is a slight correlation of radius with planet temperature (r = 0. 37)

There is a slight correlation of radius with planet temperature (r = 0. 37)

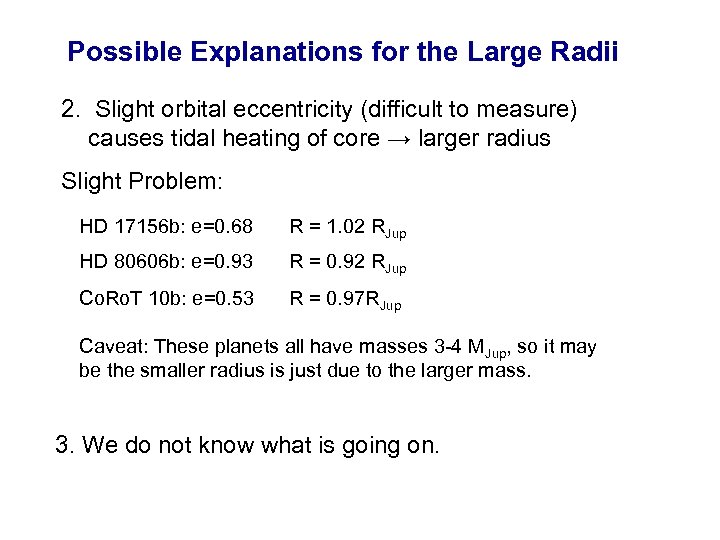

Possible Explanations for the Large Radii 2. Slight orbital eccentricity (difficult to measure) causes tidal heating of core → larger radius Slight Problem: HD 17156 b: e=0. 68 R = 1. 02 RJup HD 80606 b: e=0. 93 R = 0. 92 RJup Co. Ro. T 10 b: e=0. 53 R = 0. 97 RJup Caveat: These planets all have masses 3 -4 MJup, so it may be the smaller radius is just due to the larger mass. 3. We do not know what is going on.

Possible Explanations for the Large Radii 2. Slight orbital eccentricity (difficult to measure) causes tidal heating of core → larger radius Slight Problem: HD 17156 b: e=0. 68 R = 1. 02 RJup HD 80606 b: e=0. 93 R = 0. 92 RJup Co. Ro. T 10 b: e=0. 53 R = 0. 97 RJup Caveat: These planets all have masses 3 -4 MJup, so it may be the smaller radius is just due to the larger mass. 3. We do not know what is going on.

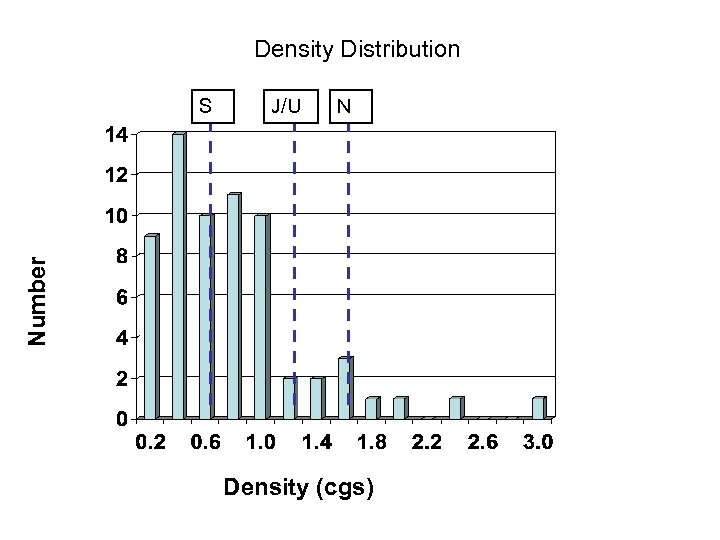

Density Distribution J/U N Number S Density (cgs)

Density Distribution J/U N Number S Density (cgs)

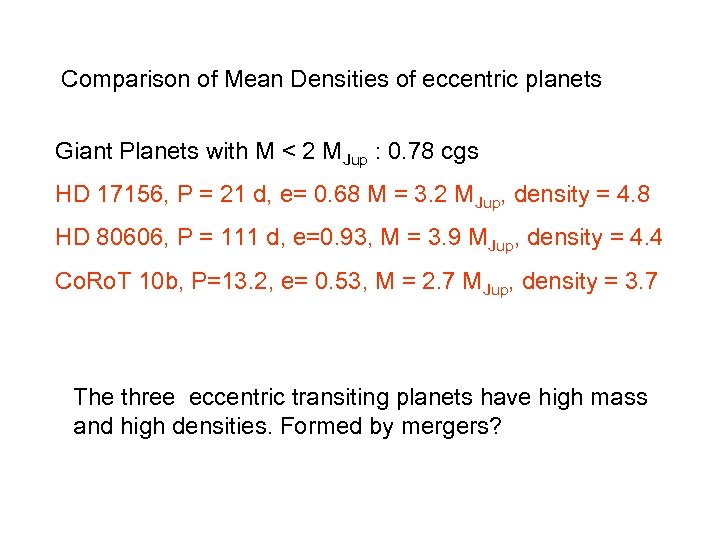

Comparison of Mean Densities of eccentric planets Giant Planets with M < 2 MJup : 0. 78 cgs HD 17156, P = 21 d, e= 0. 68 M = 3. 2 MJup, density = 4. 8 HD 80606, P = 111 d, e=0. 93, M = 3. 9 MJup, density = 4. 4 Co. Ro. T 10 b, P=13. 2, e= 0. 53, M = 2. 7 MJup, density = 3. 7 The three eccentric transiting planets have high mass and high densities. Formed by mergers?

Comparison of Mean Densities of eccentric planets Giant Planets with M < 2 MJup : 0. 78 cgs HD 17156, P = 21 d, e= 0. 68 M = 3. 2 MJup, density = 4. 8 HD 80606, P = 111 d, e=0. 93, M = 3. 9 MJup, density = 4. 4 Co. Ro. T 10 b, P=13. 2, e= 0. 53, M = 2. 7 MJup, density = 3. 7 The three eccentric transiting planets have high mass and high densities. Formed by mergers?

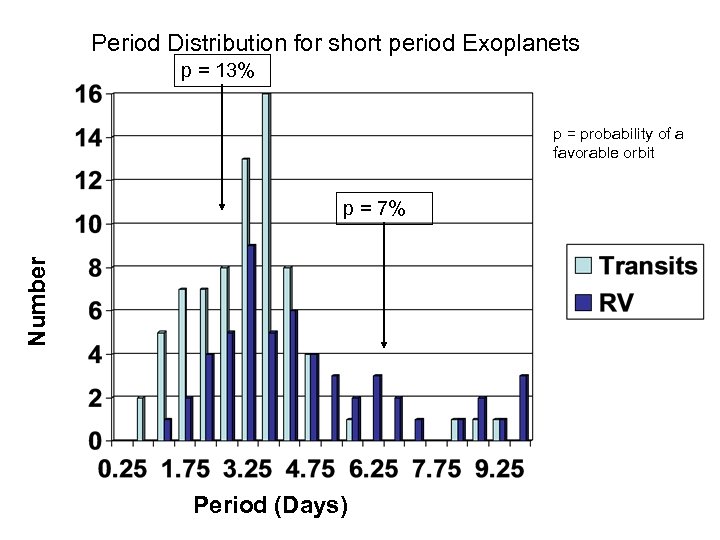

Period Distribution for short period Exoplanets p = 13% p = probability of a favorable orbit Number p = 7% Period (Days)

Period Distribution for short period Exoplanets p = 13% p = probability of a favorable orbit Number p = 7% Period (Days)

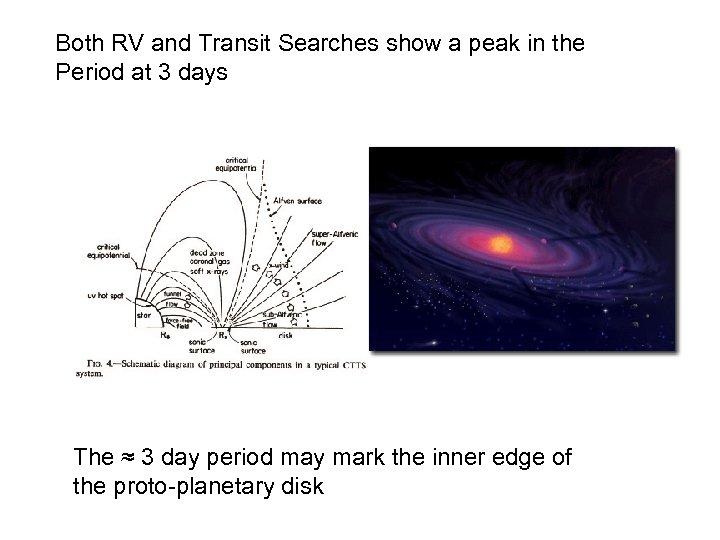

Both RV and Transit Searches show a peak in the Period at 3 days The ≈ 3 day period may mark the inner edge of the proto-planetary disk

Both RV and Transit Searches show a peak in the Period at 3 days The ≈ 3 day period may mark the inner edge of the proto-planetary disk

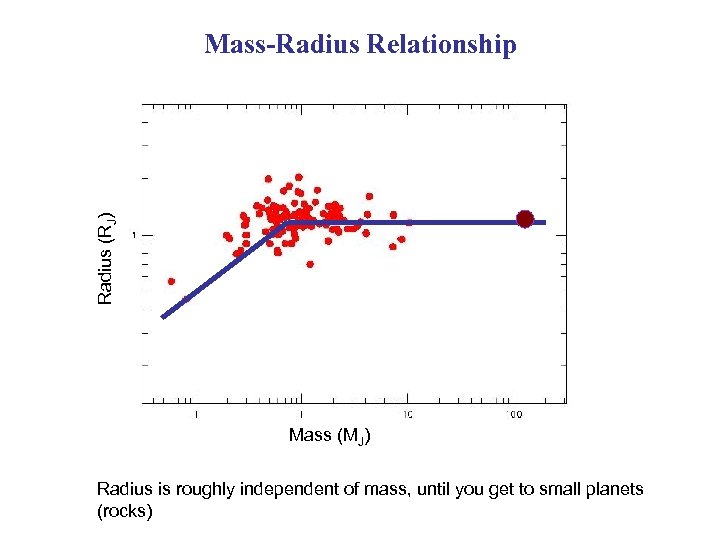

Radius (RJ) Mass-Radius Relationship Mass (MJ) Radius is roughly independent of mass, until you get to small planets (rocks)

Radius (RJ) Mass-Radius Relationship Mass (MJ) Radius is roughly independent of mass, until you get to small planets (rocks)

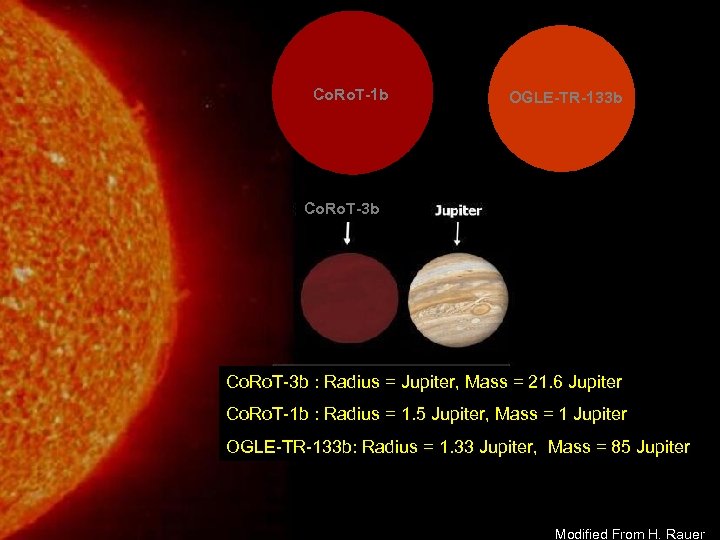

Co. Ro. T-1 b OGLE-TR-133 b Co. Ro. T-3 b : Radius = Jupiter, Mass = 21. 6 Jupiter Co. Ro. T-1 b : Radius = 1. 5 Jupiter, Mass = 1 Jupiter OGLE-TR-133 b: Radius = 1. 33 Jupiter, Mass = 85 Jupiter Modified From H. Rauer

Co. Ro. T-1 b OGLE-TR-133 b Co. Ro. T-3 b : Radius = Jupiter, Mass = 21. 6 Jupiter Co. Ro. T-1 b : Radius = 1. 5 Jupiter, Mass = 1 Jupiter OGLE-TR-133 b: Radius = 1. 33 Jupiter, Mass = 85 Jupiter Modified From H. Rauer

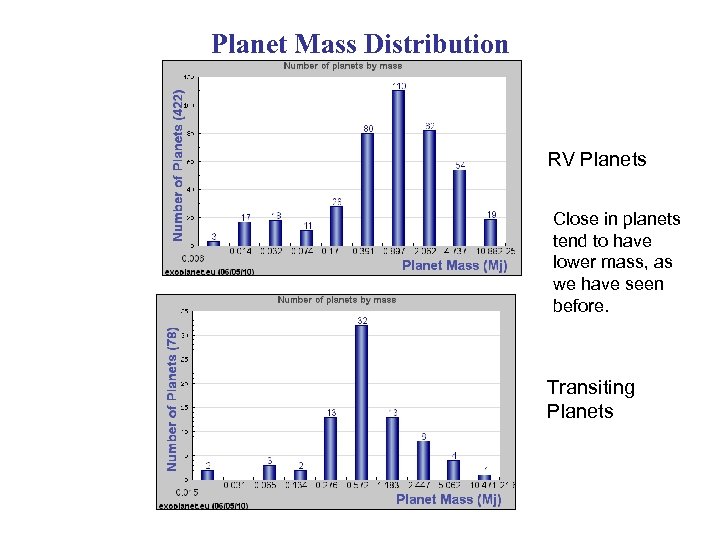

Planet Mass Distribution RV Planets Close in planets tend to have lower mass, as we have seen before. Transiting Planets

Planet Mass Distribution RV Planets Close in planets tend to have lower mass, as we have seen before. Transiting Planets

![Number Metallicity Distribution [Fe/H] Doppler result: Recall that stars with higher metal content seem Number Metallicity Distribution [Fe/H] Doppler result: Recall that stars with higher metal content seem](https://present5.com/presentation/1a61d5d45d9482e606be42f541f93dc9/image-50.jpg) Number Metallicity Distribution [Fe/H] Doppler result: Recall that stars with higher metal content seem to have a higher frequency of planets. This is not seen in transiting planets.

Number Metallicity Distribution [Fe/H] Doppler result: Recall that stars with higher metal content seem to have a higher frequency of planets. This is not seen in transiting planets.

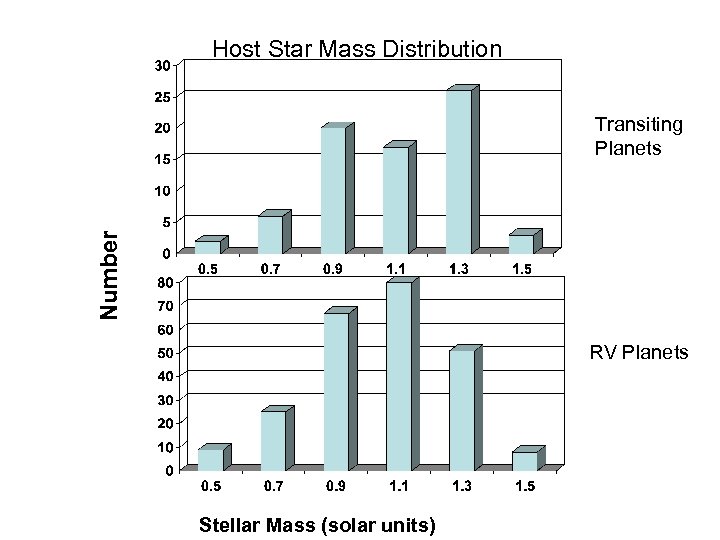

Host Star Mass Distribution Number Transiting Planets RV Planets Stellar Mass (solar units)

Host Star Mass Distribution Number Transiting Planets RV Planets Stellar Mass (solar units)

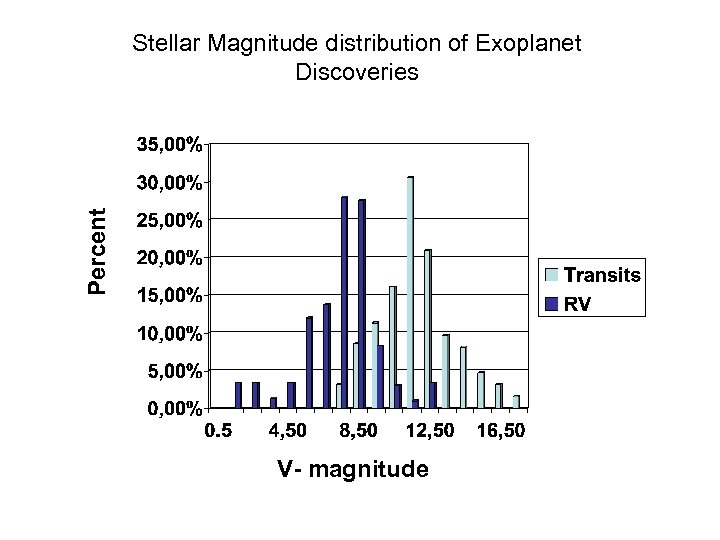

Percent Stellar Magnitude distribution of Exoplanet Discoveries V- magnitude

Percent Stellar Magnitude distribution of Exoplanet Discoveries V- magnitude

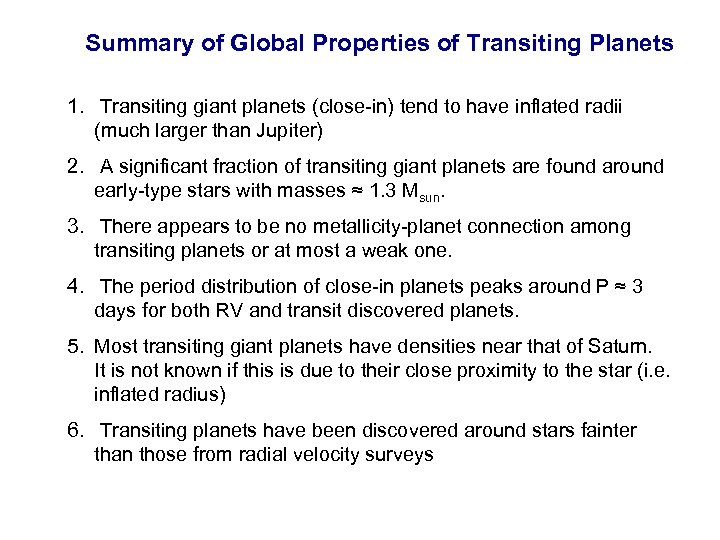

Summary of Global Properties of Transiting Planets 1. Transiting giant planets (close-in) tend to have inflated radii (much larger than Jupiter) 2. A significant fraction of transiting giant planets are found around early-type stars with masses ≈ 1. 3 Msun. 3. There appears to be no metallicity-planet connection among transiting planets or at most a weak one. 4. The period distribution of close-in planets peaks around P ≈ 3 days for both RV and transit discovered planets. 5. Most transiting giant planets have densities near that of Saturn. It is not known if this is due to their close proximity to the star (i. e. inflated radius) 6. Transiting planets have been discovered around stars fainter than those from radial velocity surveys

Summary of Global Properties of Transiting Planets 1. Transiting giant planets (close-in) tend to have inflated radii (much larger than Jupiter) 2. A significant fraction of transiting giant planets are found around early-type stars with masses ≈ 1. 3 Msun. 3. There appears to be no metallicity-planet connection among transiting planets or at most a weak one. 4. The period distribution of close-in planets peaks around P ≈ 3 days for both RV and transit discovered planets. 5. Most transiting giant planets have densities near that of Saturn. It is not known if this is due to their close proximity to the star (i. e. inflated radius) 6. Transiting planets have been discovered around stars fainter than those from radial velocity surveys

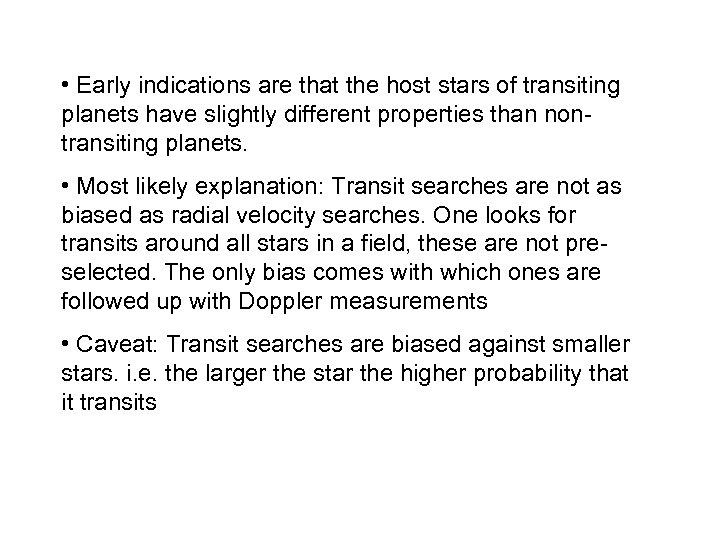

• Early indications are that the host stars of transiting planets have slightly different properties than nontransiting planets. • Most likely explanation: Transit searches are not as biased as radial velocity searches. One looks for transits around all stars in a field, these are not preselected. The only bias comes with which ones are followed up with Doppler measurements • Caveat: Transit searches are biased against smaller stars. i. e. the larger the star the higher probability that it transits

• Early indications are that the host stars of transiting planets have slightly different properties than nontransiting planets. • Most likely explanation: Transit searches are not as biased as radial velocity searches. One looks for transits around all stars in a field, these are not preselected. The only bias comes with which ones are followed up with Doppler measurements • Caveat: Transit searches are biased against smaller stars. i. e. the larger the star the higher probability that it transits

Spectroscopic Transits: The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect

Spectroscopic Transits: The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect

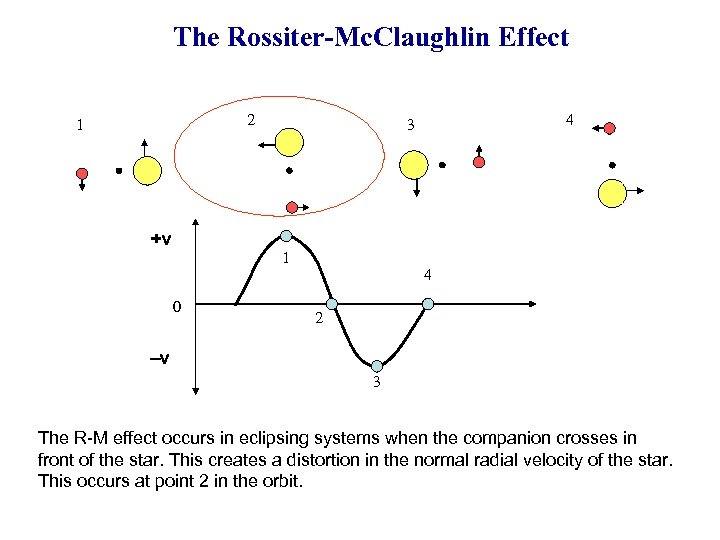

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2 1 +v 1 0 4 3 4 2 –v 3 The R-M effect occurs in eclipsing systems when the companion crosses in front of the star. This creates a distortion in the normal radial velocity of the star. This occurs at point 2 in the orbit.

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2 1 +v 1 0 4 3 4 2 –v 3 The R-M effect occurs in eclipsing systems when the companion crosses in front of the star. This creates a distortion in the normal radial velocity of the star. This occurs at point 2 in the orbit.

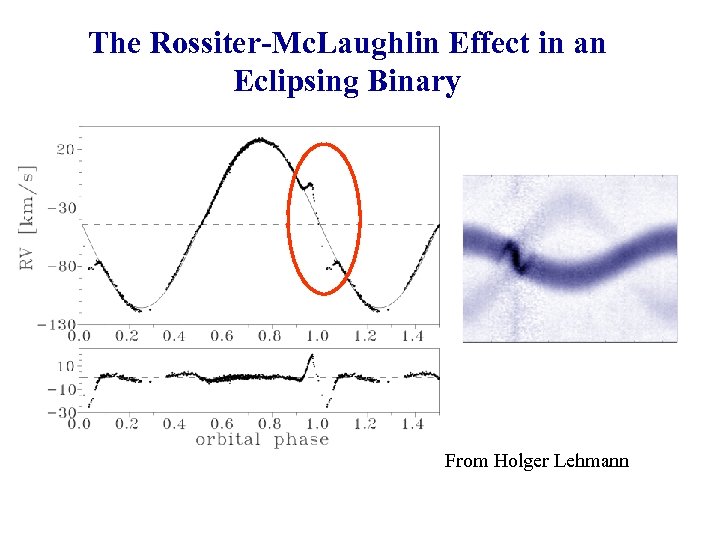

The Rossiter-Mc. Laughlin Effect in an Eclipsing Binary From Holger Lehmann

The Rossiter-Mc. Laughlin Effect in an Eclipsing Binary From Holger Lehmann

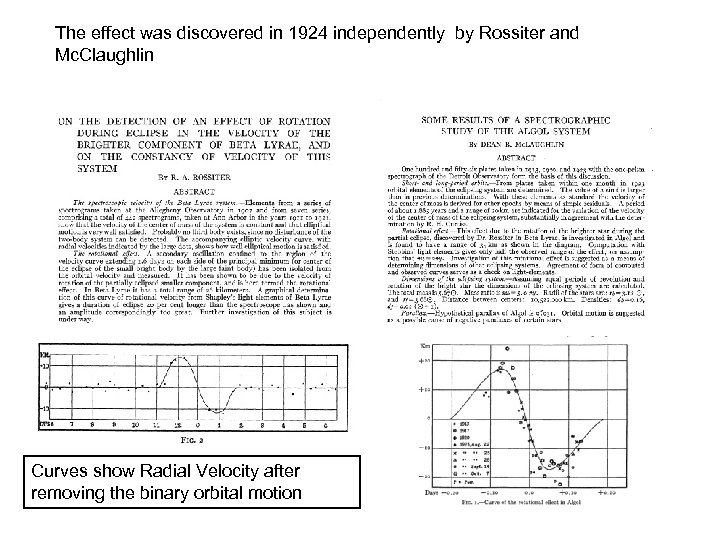

The effect was discovered in 1924 independently by Rossiter and Mc. Claughlin Curves show Radial Velocity after removing the binary orbital motion

The effect was discovered in 1924 independently by Rossiter and Mc. Claughlin Curves show Radial Velocity after removing the binary orbital motion

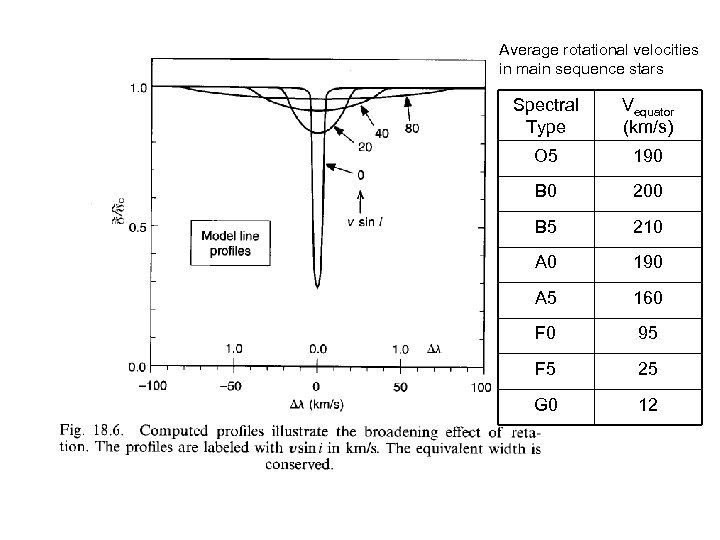

Average rotational velocities in main sequence stars Spectral Type Vequator (km/s) O 5 190 B 0 200 B 5 210 A 0 190 A 5 160 F 0 95 F 5 25 G 0 12

Average rotational velocities in main sequence stars Spectral Type Vequator (km/s) O 5 190 B 0 200 B 5 210 A 0 190 A 5 160 F 0 95 F 5 25 G 0 12

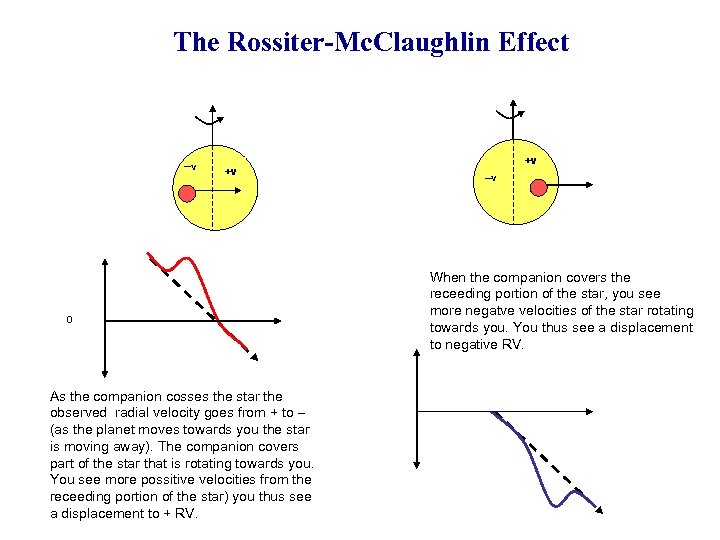

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect –v +v 0 As the companion cosses the star the observed radial velocity goes from + to – (as the planet moves towards you the star is moving away). The companion covers part of the star that is rotating towards you. You see more possitive velocities from the receeding portion of the star) you thus see a displacement to + RV. +v –v When the companion covers the receeding portion of the star, you see more negatve velocities of the star rotating towards you. You thus see a displacement to negative RV.

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect –v +v 0 As the companion cosses the star the observed radial velocity goes from + to – (as the planet moves towards you the star is moving away). The companion covers part of the star that is rotating towards you. You see more possitive velocities from the receeding portion of the star) you thus see a displacement to + RV. +v –v When the companion covers the receeding portion of the star, you see more negatve velocities of the star rotating towards you. You thus see a displacement to negative RV.

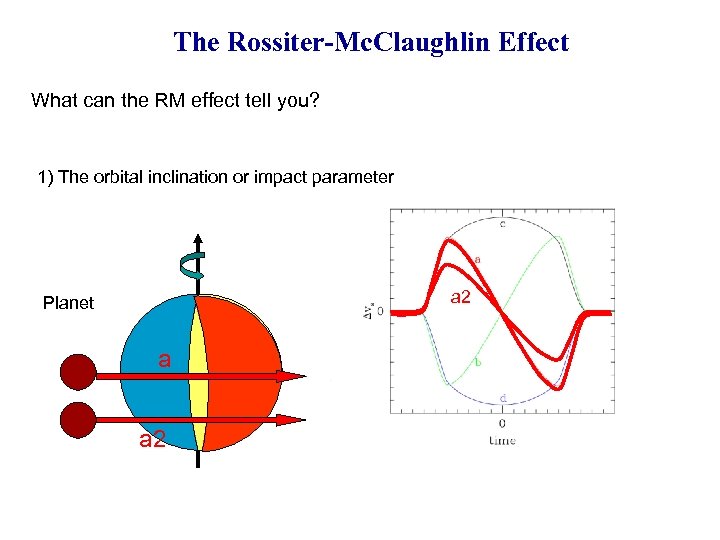

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect What can the RM effect tell you? 1) The orbital inclination or impact parameter a 2 Planet a a 2

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect What can the RM effect tell you? 1) The orbital inclination or impact parameter a 2 Planet a a 2

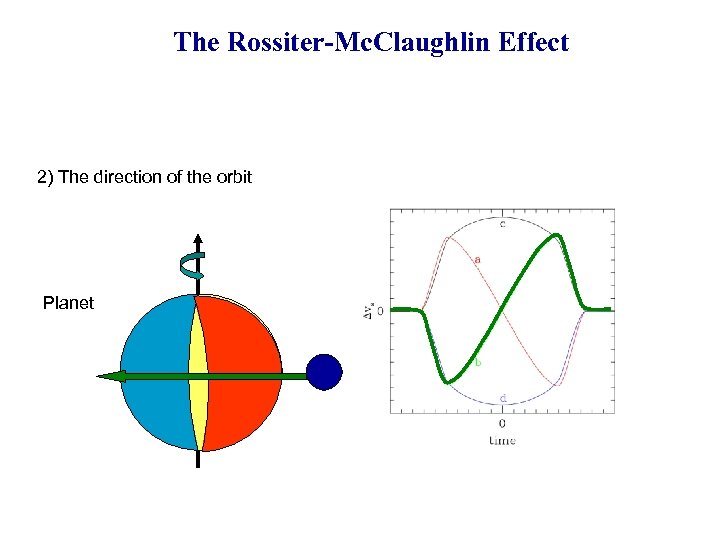

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2) The direction of the orbit Planet b

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2) The direction of the orbit Planet b

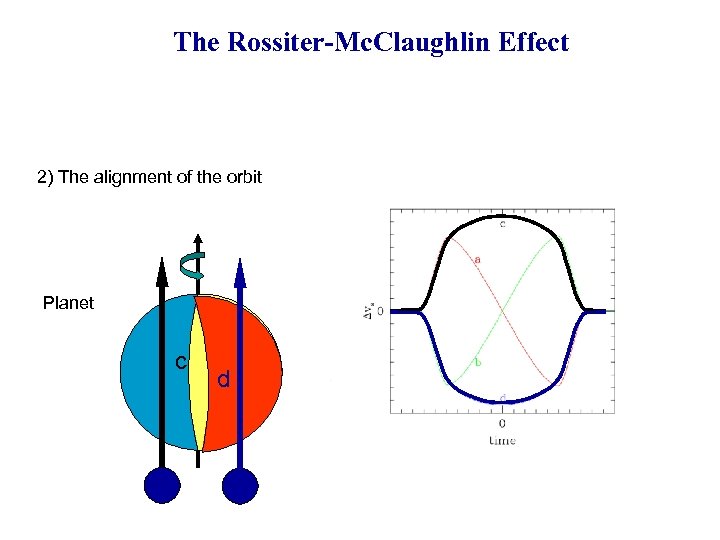

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2) The alignment of the orbit Planet c d

The Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin Effect 2) The alignment of the orbit Planet c d

l What can the RM effect tell you? 3. Are the spin axes aligned? Orbital plane

l What can the RM effect tell you? 3. Are the spin axes aligned? Orbital plane

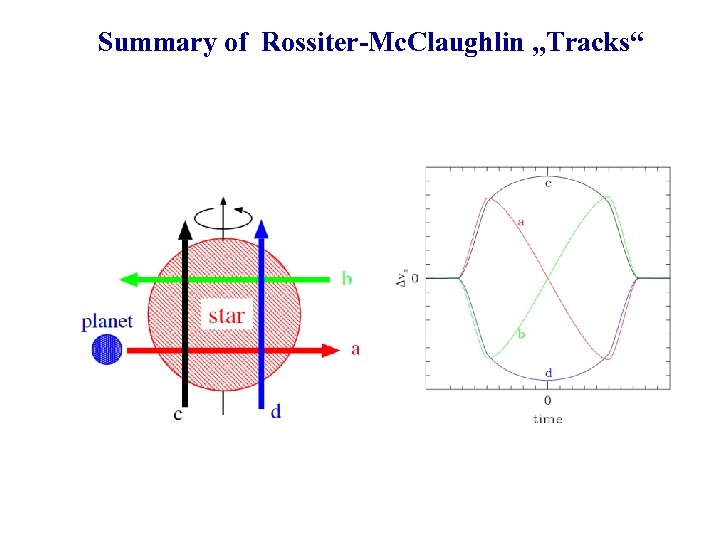

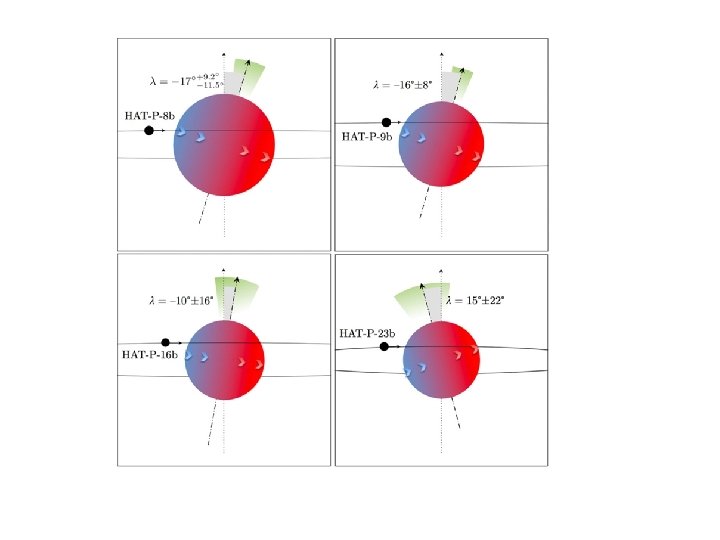

Summary of Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin „Tracks“

Summary of Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin „Tracks“

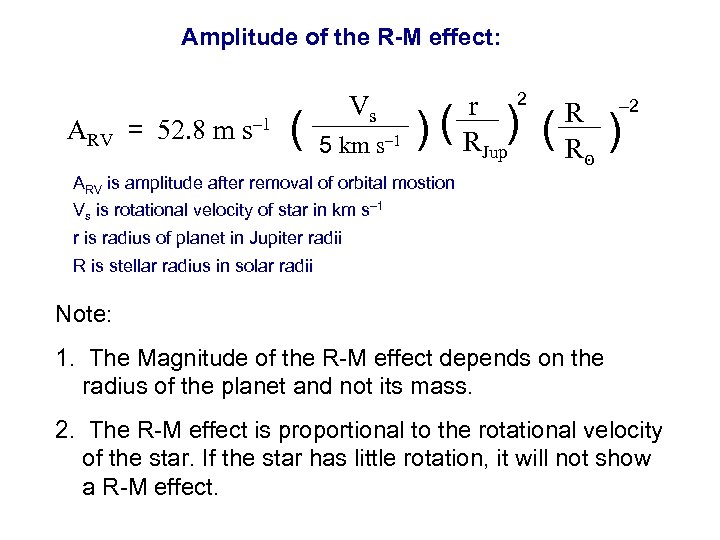

Amplitude of the R-M effect: ARV = 52. 8 m s– 1 ( Vs 5 km s– 1 )( r 2 ) RJup ( R R סּ – 2 ) ARV is amplitude after removal of orbital mostion Vs is rotational velocity of star in km s– 1 r is radius of planet in Jupiter radii R is stellar radius in solar radii Note: 1. The Magnitude of the R-M effect depends on the radius of the planet and not its mass. 2. The R-M effect is proportional to the rotational velocity of the star. If the star has little rotation, it will not show a R-M effect.

Amplitude of the R-M effect: ARV = 52. 8 m s– 1 ( Vs 5 km s– 1 )( r 2 ) RJup ( R R סּ – 2 ) ARV is amplitude after removal of orbital mostion Vs is rotational velocity of star in km s– 1 r is radius of planet in Jupiter radii R is stellar radius in solar radii Note: 1. The Magnitude of the R-M effect depends on the radius of the planet and not its mass. 2. The R-M effect is proportional to the rotational velocity of the star. If the star has little rotation, it will not show a R-M effect.

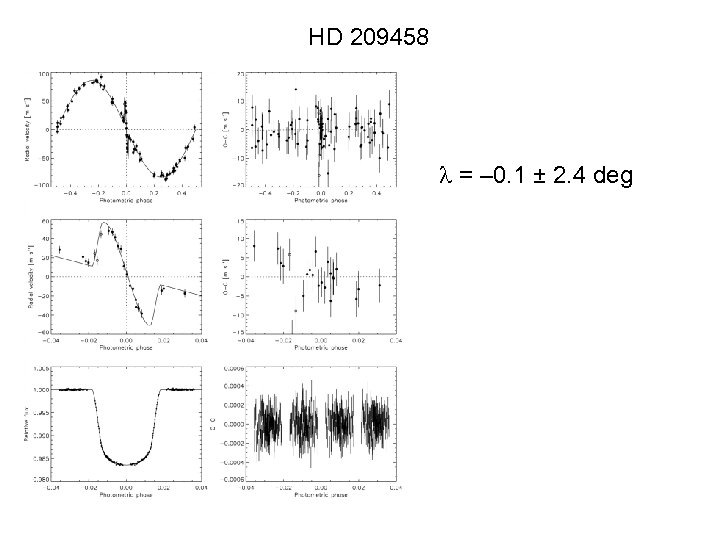

HD 209458 l = – 0. 1 ± 2. 4 deg

HD 209458 l = – 0. 1 ± 2. 4 deg

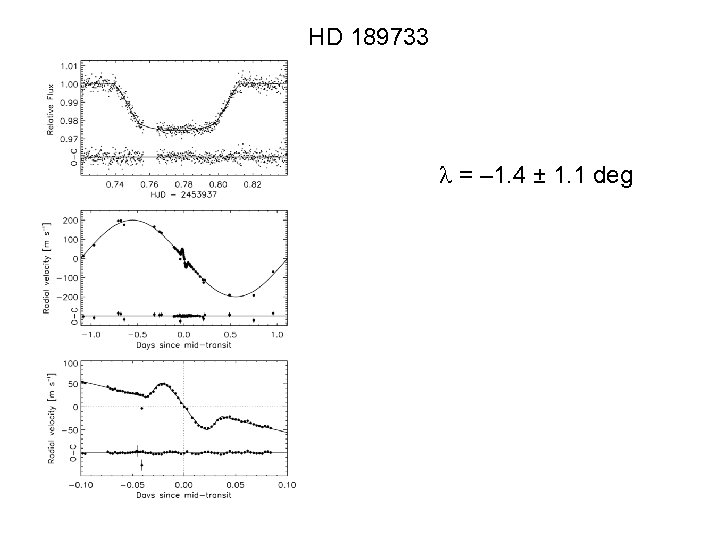

HD 189733 l = – 1. 4 ± 1. 1 deg

HD 189733 l = – 1. 4 ± 1. 1 deg

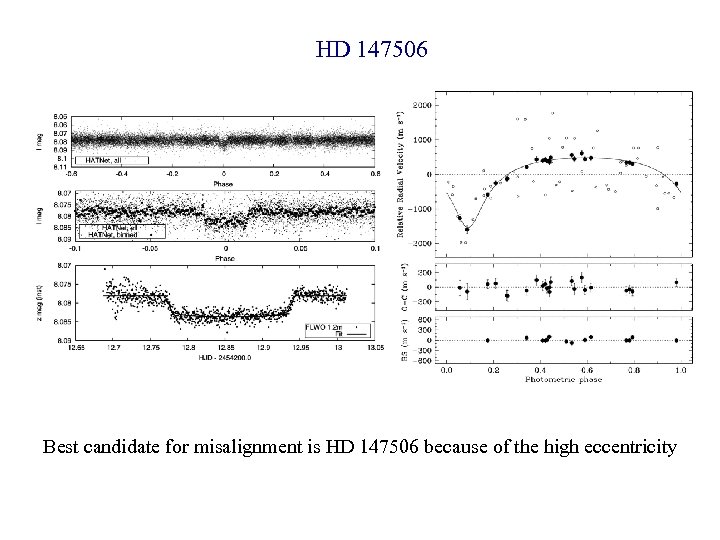

HD 147506 Best candidate for misalignment is HD 147506 because of the high eccentricity

HD 147506 Best candidate for misalignment is HD 147506 because of the high eccentricity

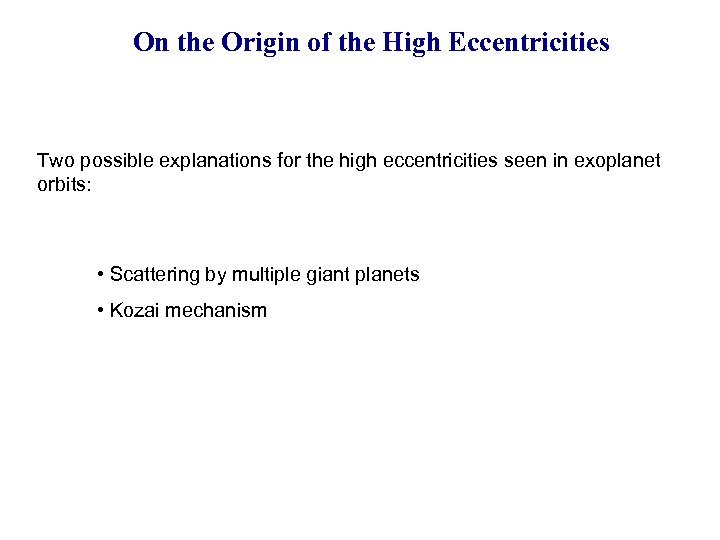

On the Origin of the High Eccentricities Two possible explanations for the high eccentricities seen in exoplanet orbits: • Scattering by multiple giant planets • Kozai mechanism

On the Origin of the High Eccentricities Two possible explanations for the high eccentricities seen in exoplanet orbits: • Scattering by multiple giant planets • Kozai mechanism

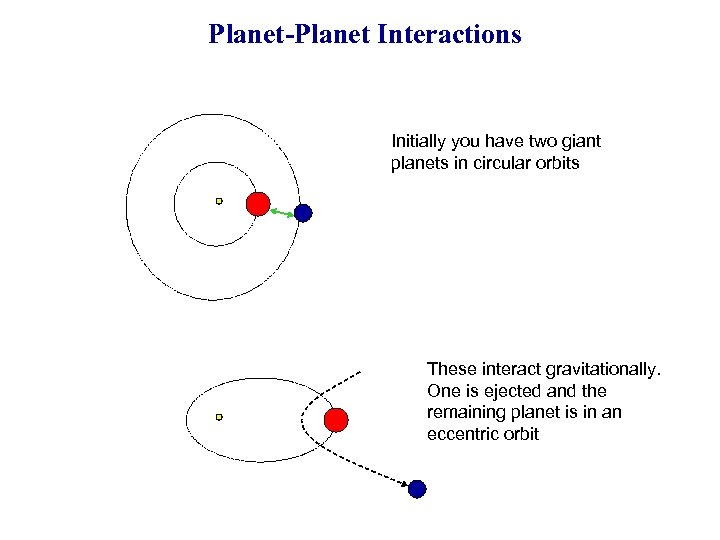

Planet-Planet Interactions Initially you have two giant planets in circular orbits These interact gravitationally. One is ejected and the remaining planet is in an eccentric orbit

Planet-Planet Interactions Initially you have two giant planets in circular orbits These interact gravitationally. One is ejected and the remaining planet is in an eccentric orbit

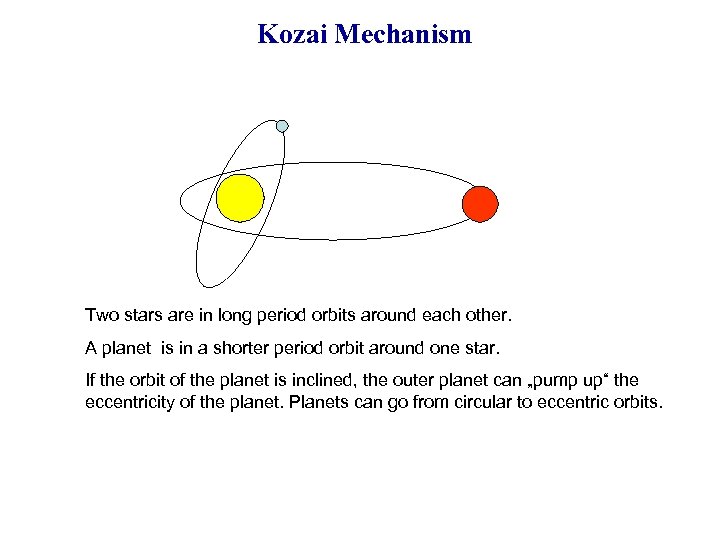

Kozai Mechanism Two stars are in long period orbits around each other. A planet is in a shorter period orbit around one star. If the orbit of the planet is inclined, the outer planet can „pump up“ the eccentricity of the planet. Planets can go from circular to eccentric orbits.

Kozai Mechanism Two stars are in long period orbits around each other. A planet is in a shorter period orbit around one star. If the orbit of the planet is inclined, the outer planet can „pump up“ the eccentricity of the planet. Planets can go from circular to eccentric orbits.

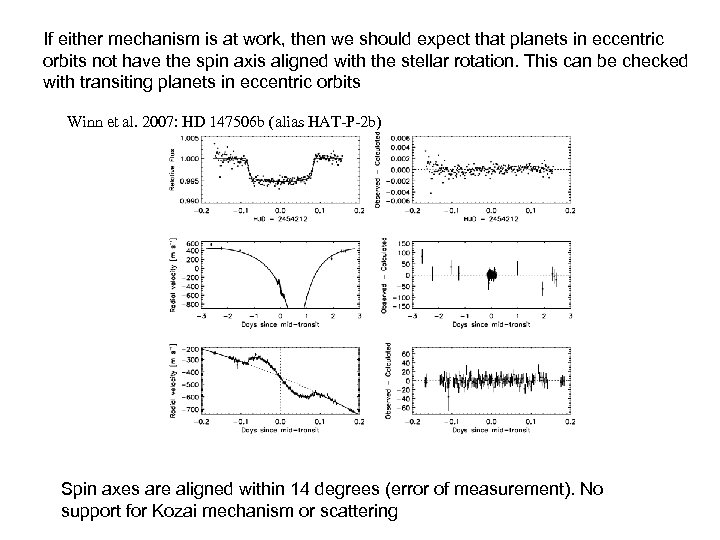

If either mechanism is at work, then we should expect that planets in eccentric orbits not have the spin axis aligned with the stellar rotation. This can be checked with transiting planets in eccentric orbits Winn et al. 2007: HD 147506 b (alias HAT-P-2 b) Spin axes are aligned within 14 degrees (error of measurement). No support for Kozai mechanism or scattering

If either mechanism is at work, then we should expect that planets in eccentric orbits not have the spin axis aligned with the stellar rotation. This can be checked with transiting planets in eccentric orbits Winn et al. 2007: HD 147506 b (alias HAT-P-2 b) Spin axes are aligned within 14 degrees (error of measurement). No support for Kozai mechanism or scattering

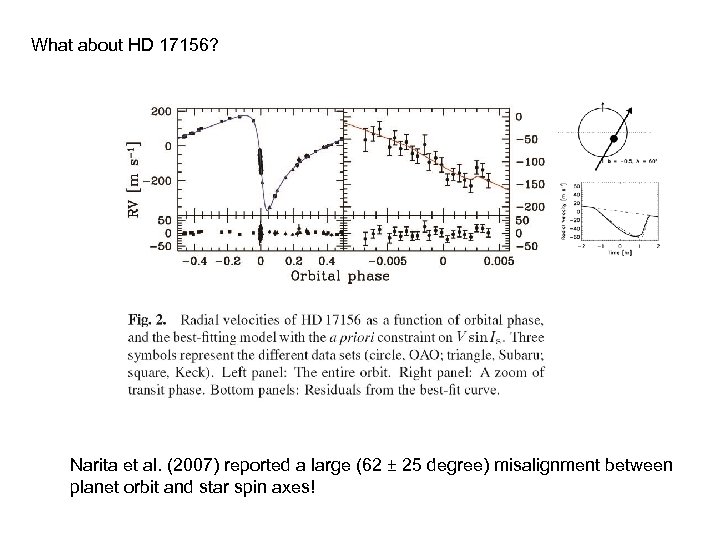

What about HD 17156? Narita et al. (2007) reported a large (62 ± 25 degree) misalignment between planet orbit and star spin axes!

What about HD 17156? Narita et al. (2007) reported a large (62 ± 25 degree) misalignment between planet orbit and star spin axes!

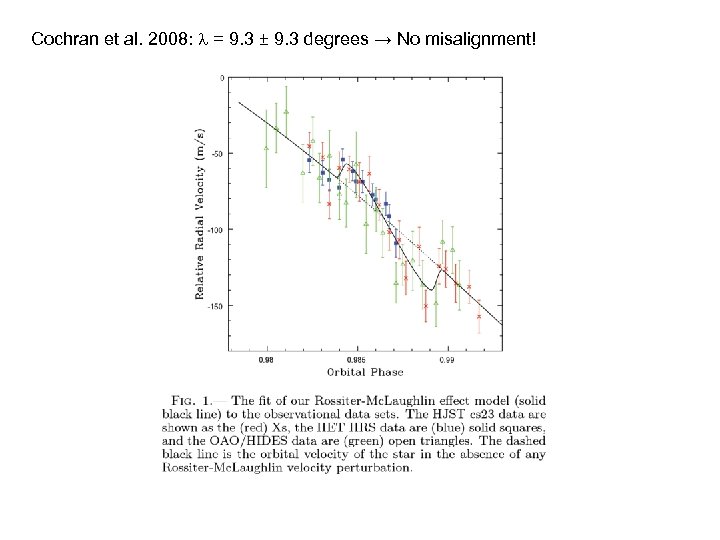

Cochran et al. 2008: l = 9. 3 ± 9. 3 degrees → No misalignment!

Cochran et al. 2008: l = 9. 3 ± 9. 3 degrees → No misalignment!

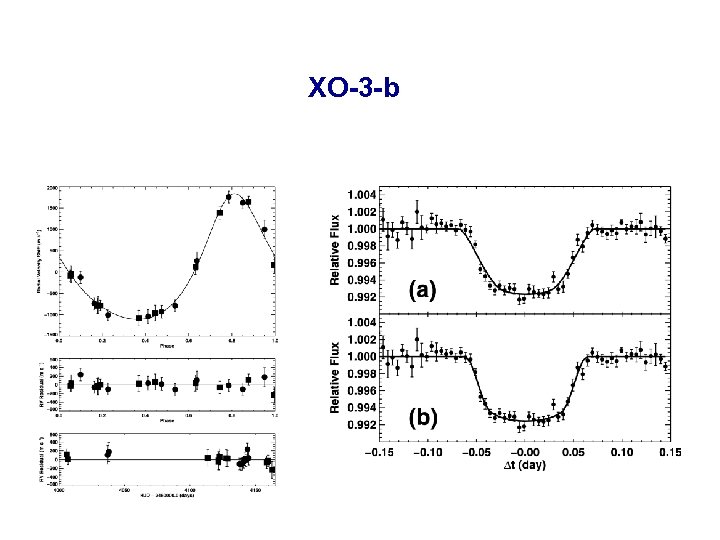

XO-3 -b

XO-3 -b

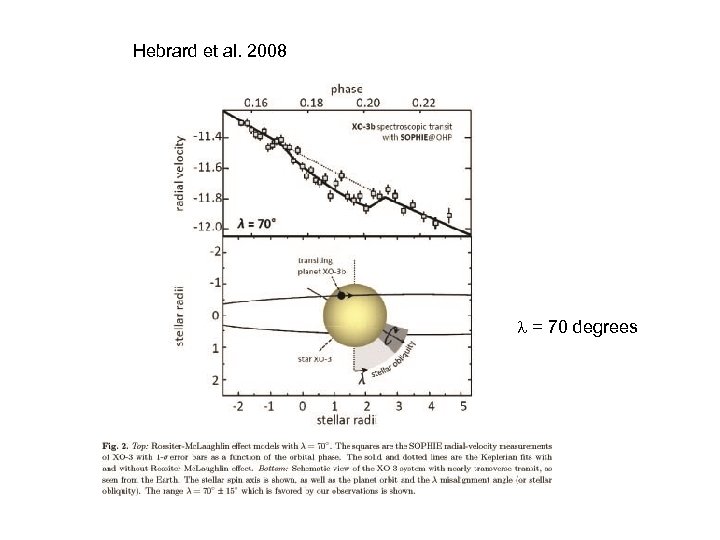

Hebrard et al. 2008 l = 70 degrees

Hebrard et al. 2008 l = 70 degrees

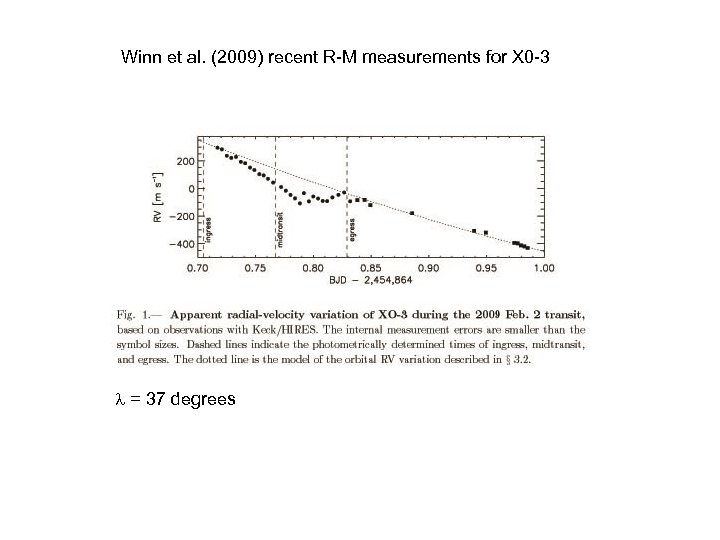

Winn et al. (2009) recent R-M measurements for X 0 -3 l = 37 degrees

Winn et al. (2009) recent R-M measurements for X 0 -3 l = 37 degrees

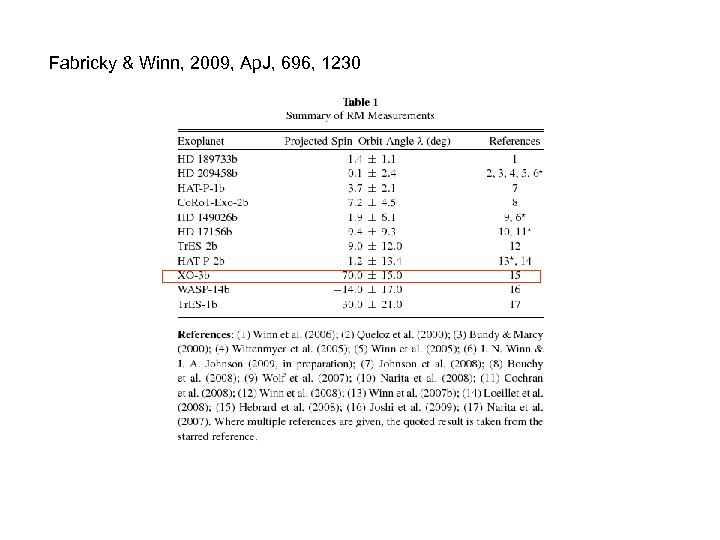

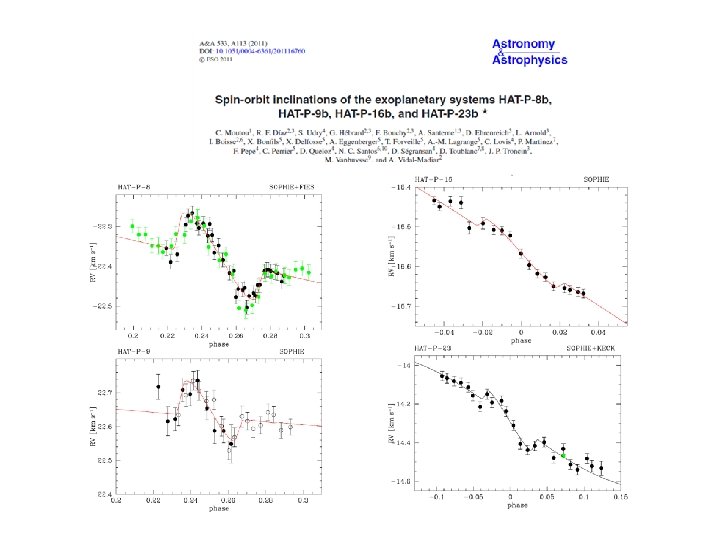

Fabricky & Winn, 2009, Ap. J, 696, 1230

Fabricky & Winn, 2009, Ap. J, 696, 1230

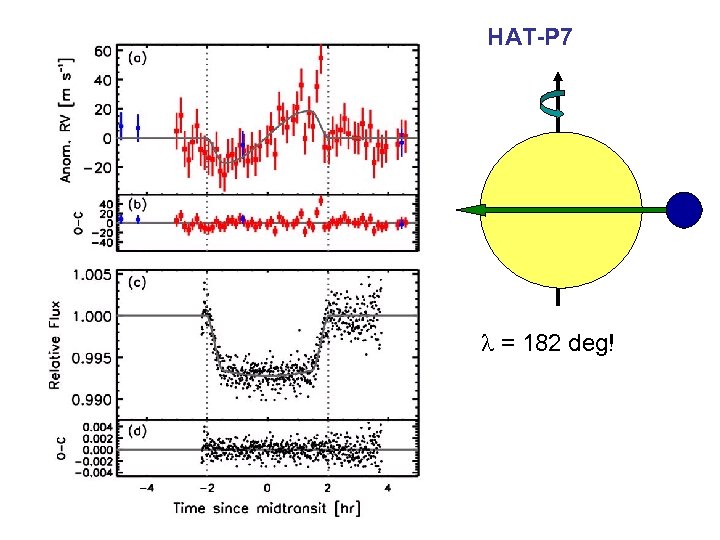

HAT-P 7 l = 182 deg!

HAT-P 7 l = 182 deg!

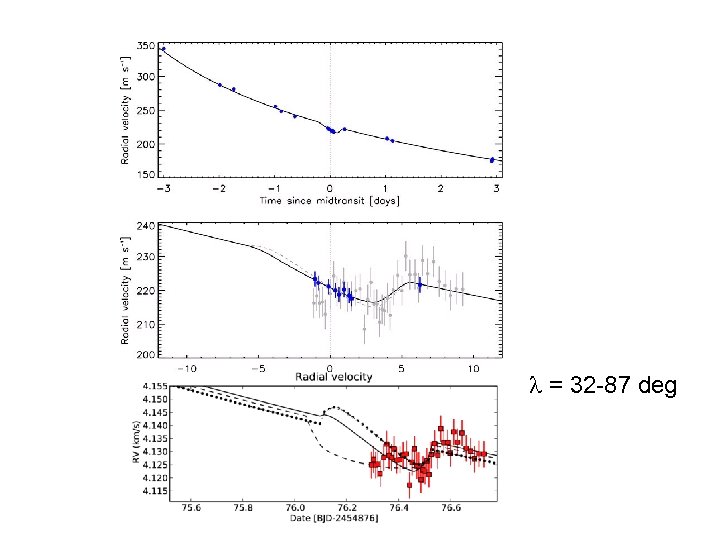

HD 80606

HD 80606

l = 32 -87 deg

l = 32 -87 deg

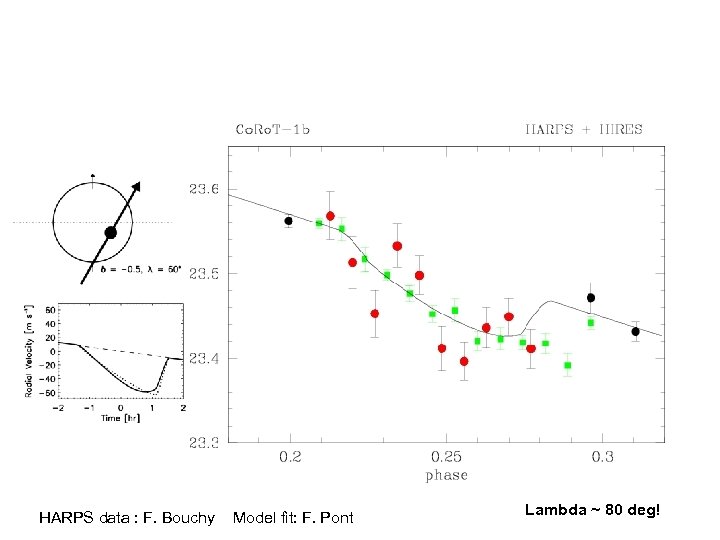

HARPS data : F. Bouchy Model fit: F. Pont Lambda ~ 80 deg!

HARPS data : F. Bouchy Model fit: F. Pont Lambda ~ 80 deg!

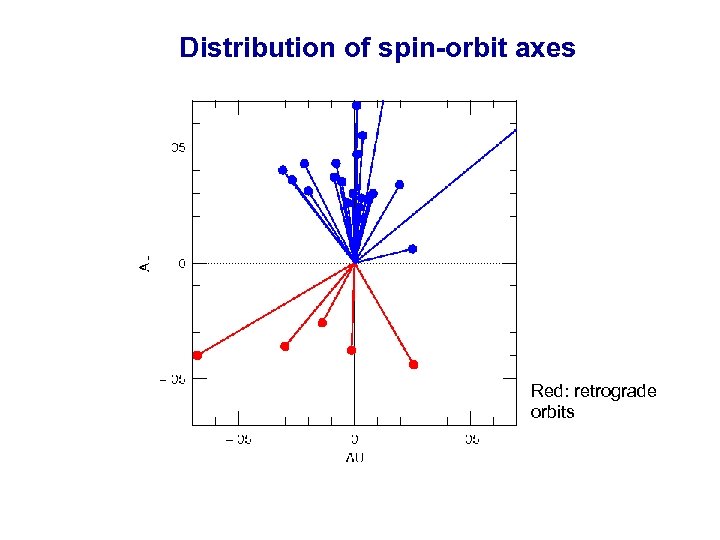

Distribution of spin-orbit axes Red: retrograde orbits

Distribution of spin-orbit axes Red: retrograde orbits

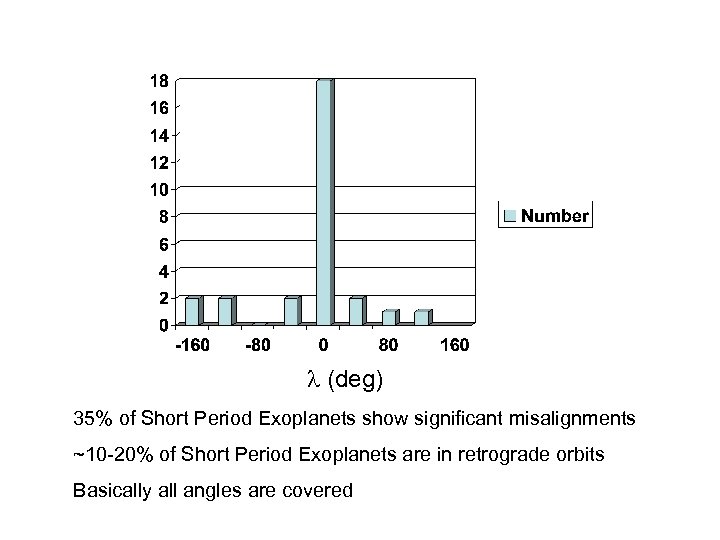

l (deg) 35% of Short Period Exoplanets show significant misalignments ~10 -20% of Short Period Exoplanets are in retrograde orbits Basically all angles are covered

l (deg) 35% of Short Period Exoplanets show significant misalignments ~10 -20% of Short Period Exoplanets are in retrograde orbits Basically all angles are covered

2.

2.

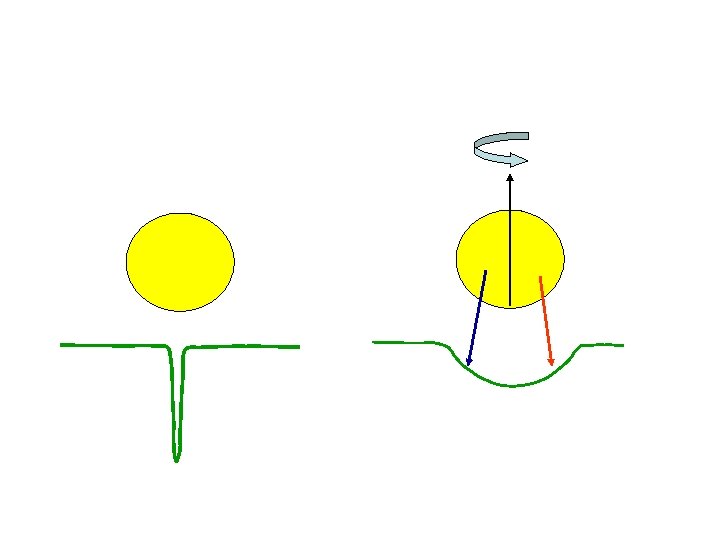

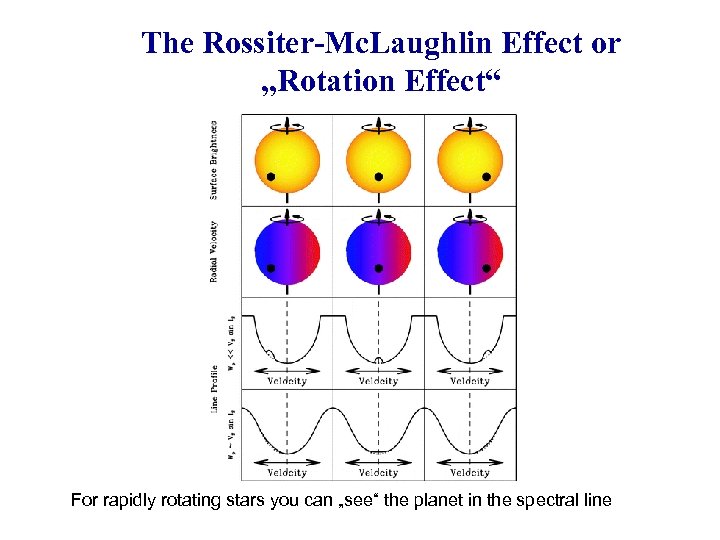

The Rossiter-Mc. Laughlin Effect or „Rotation Effect“ For rapidly rotating stars you can „see“ the planet in the spectral line

The Rossiter-Mc. Laughlin Effect or „Rotation Effect“ For rapidly rotating stars you can „see“ the planet in the spectral line

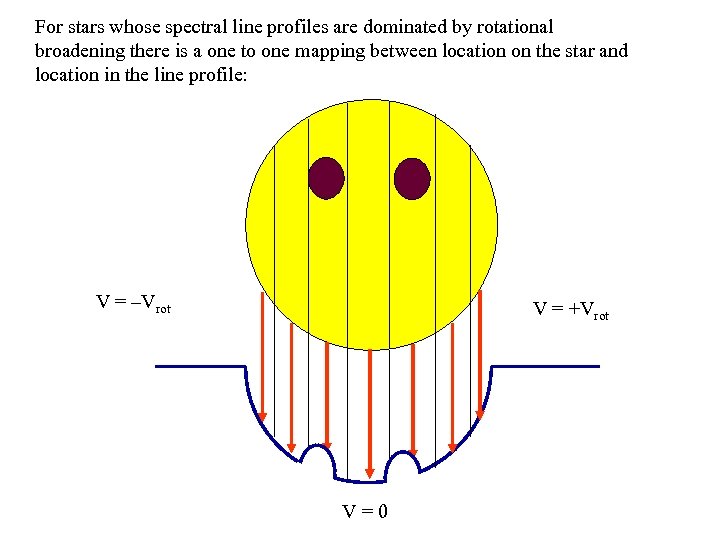

For stars whose spectral line profiles are dominated by rotational broadening there is a one to one mapping between location on the star and location in the line profile: V = –Vrot V = +Vrot V=0

For stars whose spectral line profiles are dominated by rotational broadening there is a one to one mapping between location on the star and location in the line profile: V = –Vrot V = +Vrot V=0

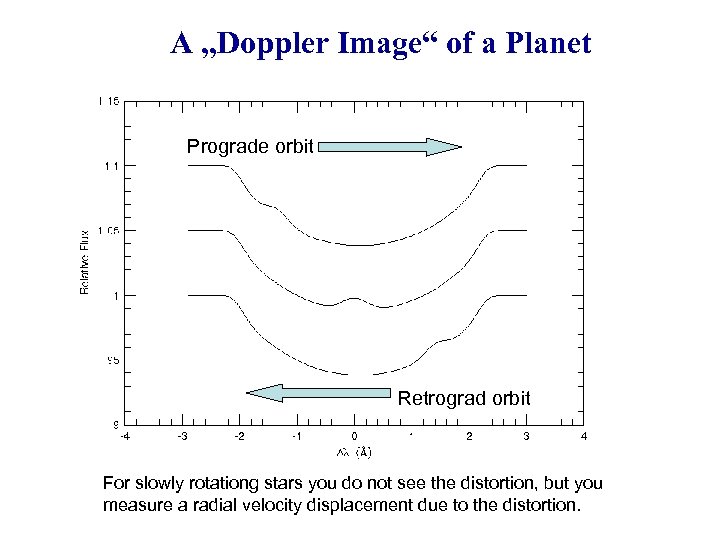

A „Doppler Image“ of a Planet Prograde orbit Retrograd orbit For slowly rotationg stars you do not see the distortion, but you measure a radial velocity displacement due to the distortion.

A „Doppler Image“ of a Planet Prograde orbit Retrograd orbit For slowly rotationg stars you do not see the distortion, but you measure a radial velocity displacement due to the distortion.

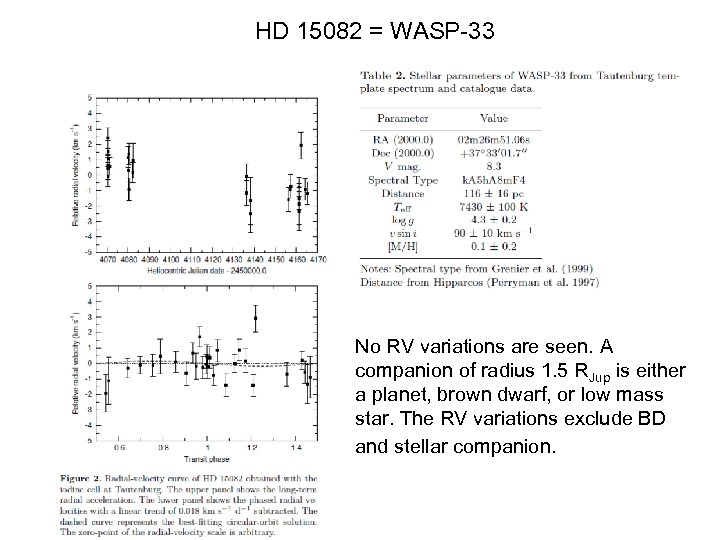

HD 15082 = WASP-33 No RV variations are seen. A companion of radius 1. 5 RJup is either a planet, brown dwarf, or low mass star. The RV variations exclude BD and stellar companion.

HD 15082 = WASP-33 No RV variations are seen. A companion of radius 1. 5 RJup is either a planet, brown dwarf, or low mass star. The RV variations exclude BD and stellar companion.

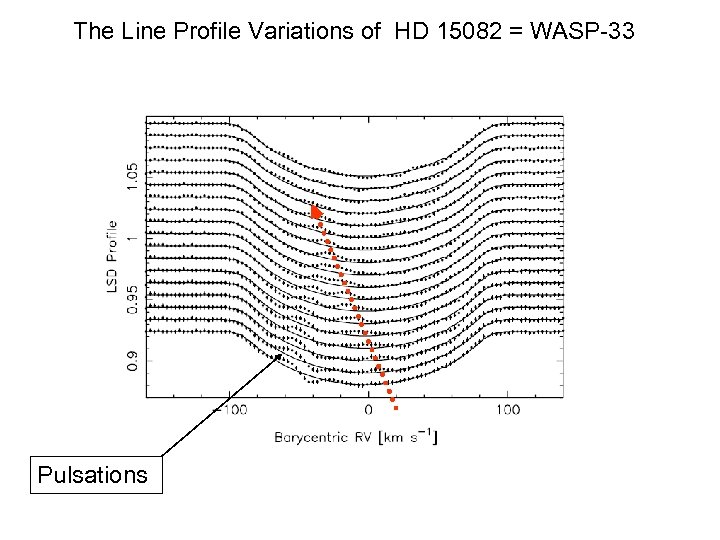

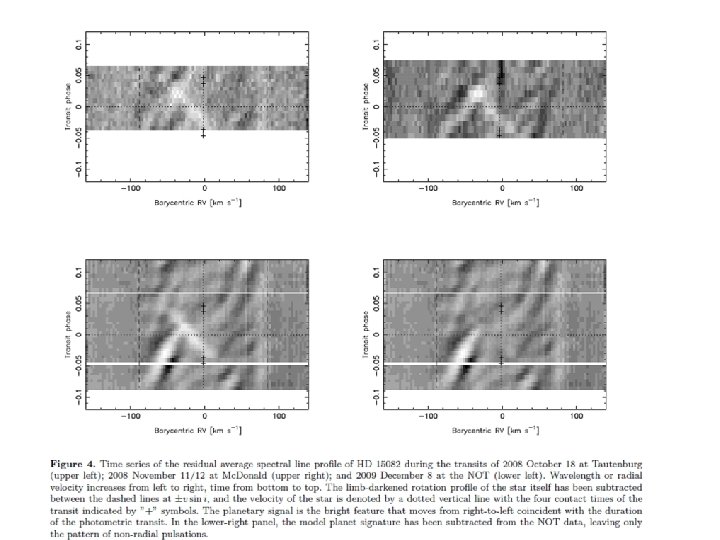

The Line Profile Variations of HD 15082 = WASP-33 Pulsations

The Line Profile Variations of HD 15082 = WASP-33 Pulsations

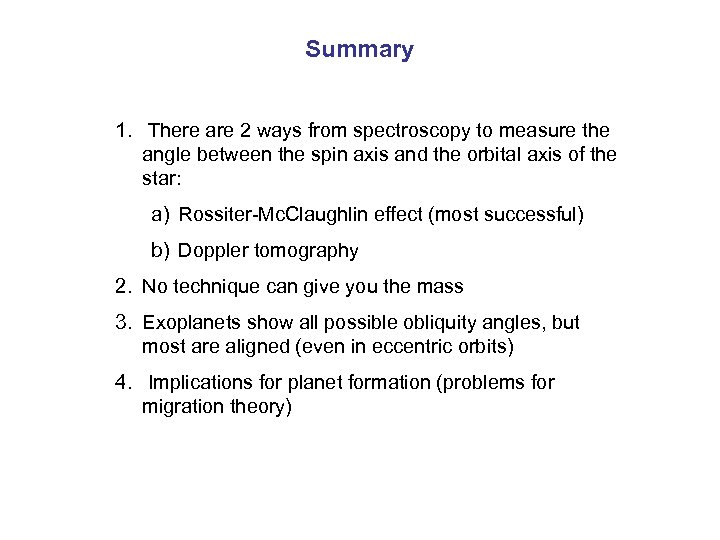

Summary 1. There are 2 ways from spectroscopy to measure the angle between the spin axis and the orbital axis of the star: a) Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin effect (most successful) b) Doppler tomography 2. No technique can give you the mass 3. Exoplanets show all possible obliquity angles, but most are aligned (even in eccentric orbits) 4. Implications for planet formation (problems for migration theory)

Summary 1. There are 2 ways from spectroscopy to measure the angle between the spin axis and the orbital axis of the star: a) Rossiter-Mc. Claughlin effect (most successful) b) Doppler tomography 2. No technique can give you the mass 3. Exoplanets show all possible obliquity angles, but most are aligned (even in eccentric orbits) 4. Implications for planet formation (problems for migration theory)