ec488a2aacfdf0f0d15266ba7811d035.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 38

The Stability and Fragility of Walrasian General Equilibrium Herbert Gintis Santa Fe Institute Central European University Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET) January 2014

What is General Equilibrium? There is one generally accepted model of the large-scale behavior of the market economy, known as Walrasian general equilibrium. The Swiss economist Léon Walras created this theory in 1874 -1877 in his Elements of Pure Economics Léon Walras, 1834 -1910

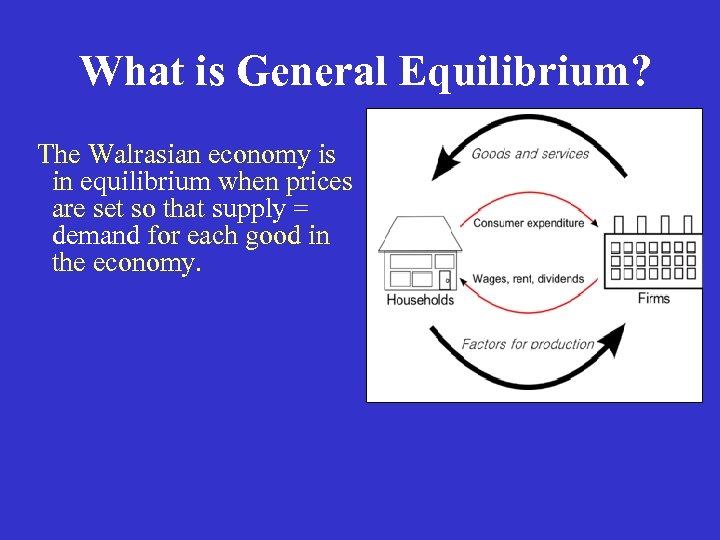

What is General Equilibrium? The Walrasian economy consists of households and firms. Firms buy or rent the services of inputs at given market prices, combine them to produce outputs which they sell at given market prices to the households.

What is General Equilibrium? Inputs include labor, capital goods (rented), raw materials, and the outputs of other firms (purchased). Inputs, as well as shares in the net profit of the firms, are owned by the households, and form their wealth. In each period, households buy the output of the various firms, some of which they consume, and some of which they add to their stock of wealth.

What is General Equilibrium? The Walrasian economy is in equilibrium when prices are set so that supply = demand for each good in the economy.

What is General Equilibrium? In the period 1952 -1954, Kenneth Arrow and Gerard Debreu showed that with plausible assumptions, there exists a set of equilibrium (market clearing) prices. Gerard Debreu, 1921 -2004 Kenneth Arrow, 1921 -

The Quest for Stability The question of stability of the Walrasian economy was a central research focus in the years immediately following the existence proofs. The models of Arrow et al. assumed that out of equilibrium, there is a system of common prices shared by all agents, the time rate of change of prices being a function of aggregate excess demand. So when a good is in excess demand, its price increases, and when it is in excess supply, its price decreases. The problem is that this must happen in all markets simultaneously.

The Quest for Stability But who changes the prices? It cannot be individual agents, because there is one price for each good in the whole economy! Arrow et al. assumed that the price system was controlled by a mythical “auctioneer” (commisaire-priseur in French) acting outside the economy to update prices in the current period on the basis of the current pattern of excess demand, using a process of “tâtonnement, ” as was first suggested by Walras himself.

Walras’ Auctioneer The auctioneer, before any buying and selling takes place, 1. calls out a set of prices, 2. asks firms and households say how much they want to buy and sell at these prices, 3. calculates the excess demand or excess supply for each sector, 4. adjusts the prices to bring the markets closer to equilibrium, 5. Then back to 1, until all markets are in equilibrium. 6. Only then is production and trade permitted, at the specified market-clearing prices.

The Quest for Stability Even if this project had been successful, the result would have been of doubtful value, as the tâtonnement process is purely fanciful. However, it was not successful. The quest for a general stability theorem was derailed by Herbert Scarf''s (1960) simple examples of unstable Walrasian equilibria.

The Quest for Stability General equilibrium theorists in the early 1970's harbored some expectation that plausible restrictions on the shape of the excess demand functions might entail stability, but Sonnenschein (1973), Mantel (1974, 1976), and Debreu (1974) showed that aggregate excess demand functions can have virtually any shape at all. It follows that the tâtonnement process cannot generally be stable.

The Quest for Stability Surveying the state of the art some quarter century after Arrow and Debreu's seminal existence theorems, Franklin Fisher (1983) concluded that little progress had been made towards a plausible model of Walrasian market dynamics.

The Quest for Stability It is now more than thirty years since Fisher's remarks, but it remains the case that the current literature offers us nothing systematic about the dynamics of decentralized competitive market economies. Given this situation, it is hardly surprising that economic theory has had difficulty in shedding light on the causes of financial crisis, and offers no advice on how to prevent future occurrences without reducing the effectiveness of the financial system.

The Quest for Stability Modern macroeconomics is simply smoke and mirrors, in which the ‘representative agent’ and the ‘representative firm’ replaces decentralized exchange, and in which it is assumed that equilibrium is instantaneously achieved. In fact, without dynamics, nothing cogent can be said about the roots of economic instability.

Rethinking Macroeconomics My work, together with my INET colleague Antoine Mandel (University of Paris, La Sorbonne), returns to a study of the fully decentralized Walrasian model, but this time with the understanding that the market economy is a complex, dynamic, nonlinear system that must be modeled using novel analytical tools. The goal is a model of market dynamics that analytically specifies the conditions under which the system is robust, thus suggesting regulations that promote robustness without compromising efficiency and capacity to innovate.

Private Prices We drop the auctioneer and replace public prices (one price per good, public information) with private prices. Each agent in the economy has a personal price vector ranging over all goods in the economy, indicating the price ratios at which the agent is willing to trade. These price vectors are private information, but with positive probability an agent learns the price vector of another agent, as well as that agent’s level of trading success. When this information is revealed, the newly-informed agent can adopt the other agent’s price vector, and will do so if the other agent has been more successful in past trades.

Private Prices Thus the process of price change is a form of social learning, in which the practices of the successful are copied by the less successful. This process also gives rise to a replicator dynamic, which governs the dynamics of the Walrasian economy. The resulting economic system is a population game in which each production sector is one population. and individual strategies are private price vectors. Each Nash equilibrium of this population game is a Walrasian (market-clearing) equilibrium.

The Stability of Walrasian General Equilibrium The standard properties of population games can be exploited to show that all Nash equilibria are pure strategy equilibria and are stable in the replicator dynamic (Gintis and Mandel, 2013). This theorem does not reveal the dynamics of decentralized market systems because the proof implicitly uses fixed point theorems and hence is not constructive. We explore the dynamics constructively through the use of Markov models.

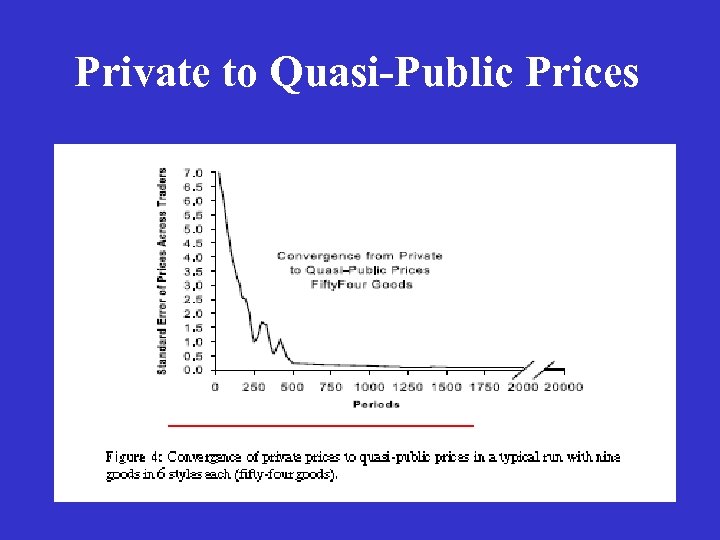

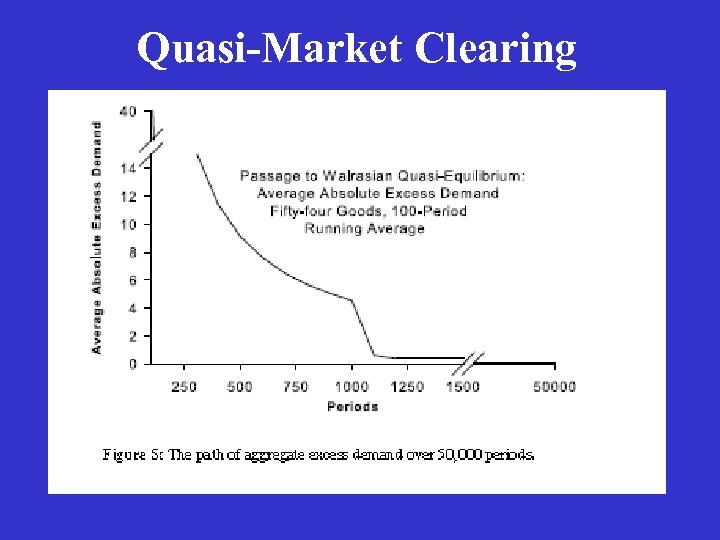

A Decentralized Market System with Individual Production I have explored decentralized market economies in several publications (e. g. , Gintis, Economic Journal 2007, ACM -Transactions in Intelligent Systems, 2013). Starting the Markov economy with a random assignment of prices to each agent, the economy moves quickly to what I term quasi-public prices, i. e. , private prices with low relative standard error across agents. In the long run, quasi-public prices move to what I term general Walrasian quasi-equilibrium, i. e. , a stationary distribution of the Markov process with nearmarket-clearing prices in almost all periods.

Private to Quasi-Public Prices

Quasi-Market Clearing

Adaptive vs. Rational Expectations Standard macroeconomic theory (dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models) assume “rational expectations. ” Social learning models assume “adaptive expectations. ” The two concepts coincide when the agents have no information concerning the underlying tendencies of the market exchange system. Rational expectations means individuals do not consistently make the same mistakes. Adaptive expectations, together with random mutations in play strategies, ensures rational expectations.

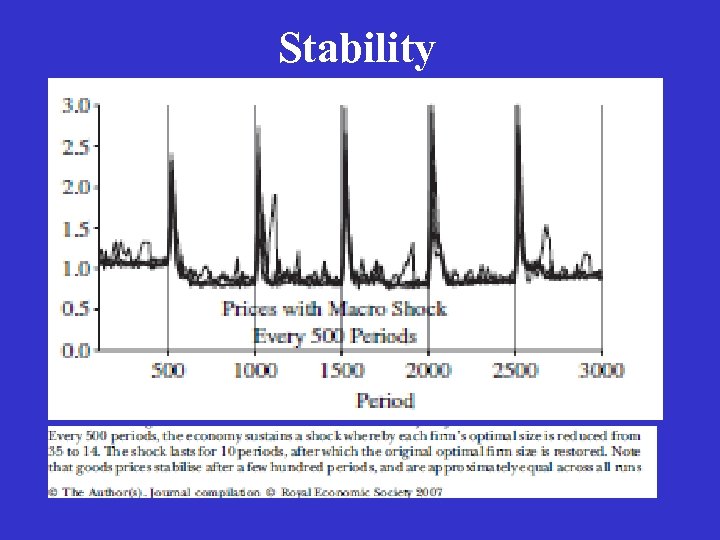

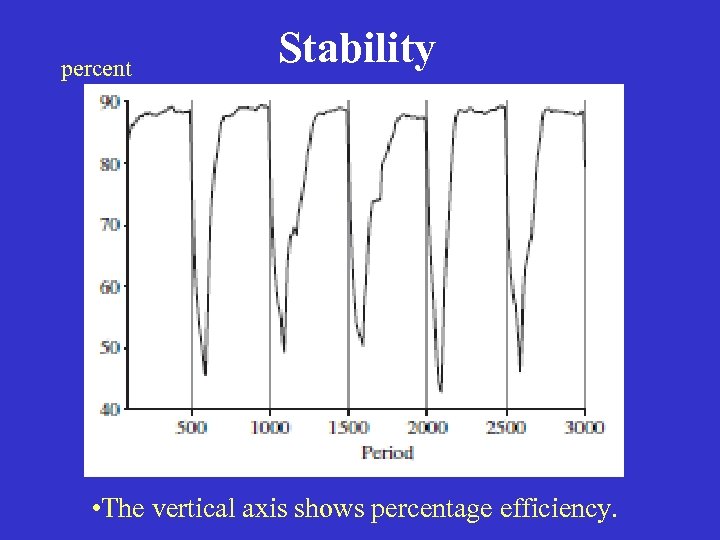

Fragility vs. Stability There is little doubt but that the above stability properties will extend to more complex decentralized market economies. However a system can be stable, yet extremely robust or, by contrast, extremely fragile in reaction to shocks. I find that in a fairly realistic model of a contemporary advanced economy, price bubbles occur rather frequently, although in the absence of a sophisticated financial sector, they do not produce large aggregate dislocations in labor and product markets.

Basic Assumptions My more realistic agent-based model (The Economic Journal, 2007) assumes that consumers must engage in price searches in each period; workers have a subjective reservation wage that they use to determine whether to accept a job offer; firms know their production costs, but not their demand curves, and hence must experiment and learn. There is a central bank and a tax-collecting authority, as well as a government sector that services unemployment insurance.

Basic Assumptions Workers periodically search for alternative job opportunities; firms maximize profits by experimentally varying their operating characteristics and copying the behavior of other firms that are more successful than themselves; both prices and quantities respond to conditions of excess supply or demand; all adjustment parameters are agent- and firm-specific, and evolve endogenously.

Adjustment Processes In each period: For each firm inventory growth leads to lowering of price a small amount, and excess demand leads to raising price a small amount. average sector profits > 0 leads to a single firm entering the sector, and average profits < 0 leads to a single firm going bankrupt. firms make limited searches for alternative employees, and workers make limited searches for alternative employers. agents revise their consumption, production, employment, and trading strategies by sampling the population, and imitating the strategies of others who appear to be relatively successful. all adjustment rates are endogenous

Adjustment Processes Because all players (firms and workers) adjust their behavior by imitating the successful, the economic dynamic is an evolutionary dynamic imitation leads to correlated errors, so the statistical independence of errors assumptions that plague traditional macroeconomic models are absent here: “fat tails” are the rule, and there are large excursions from equilibrium in the absence of macro-level shocks.

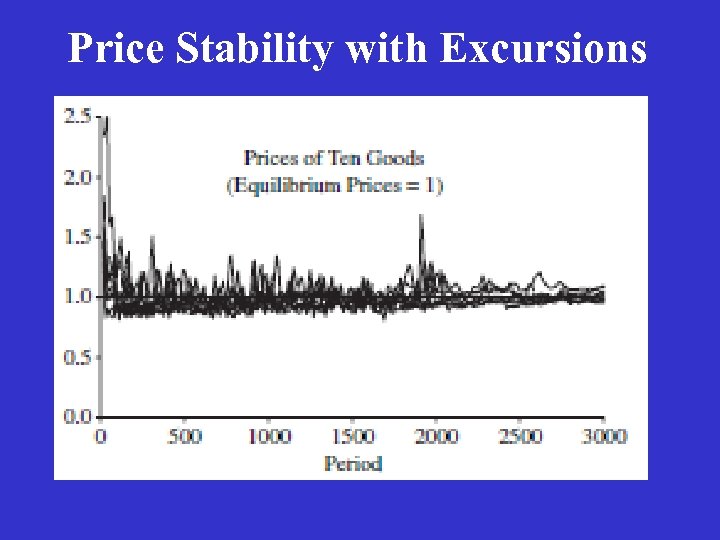

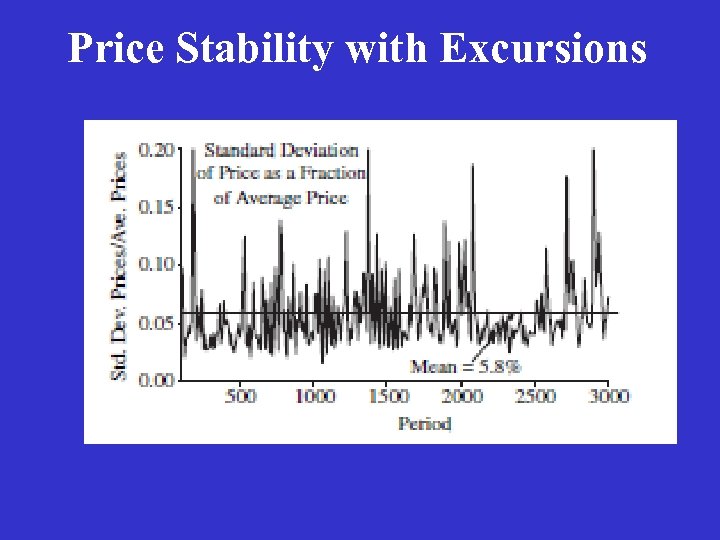

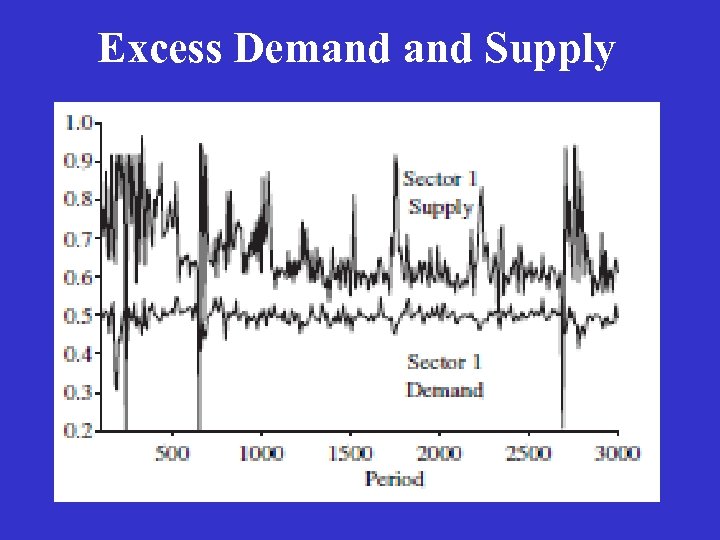

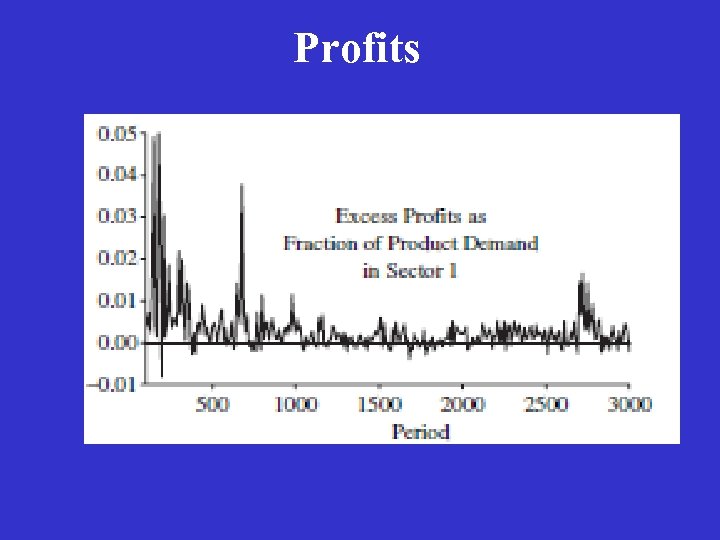

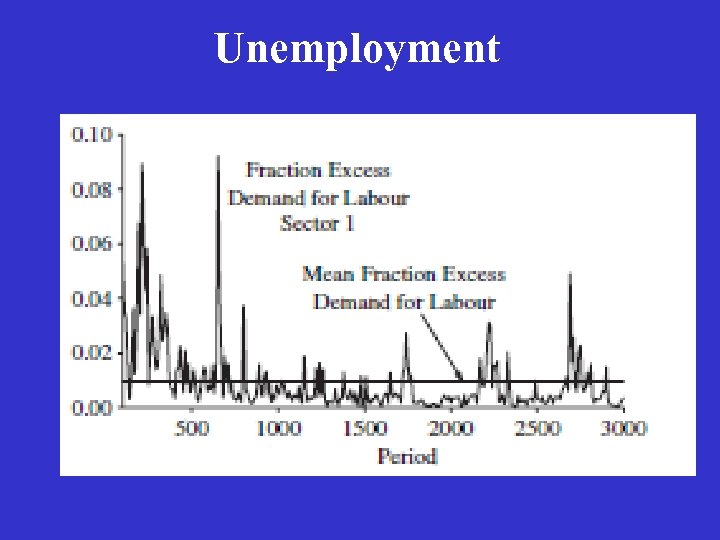

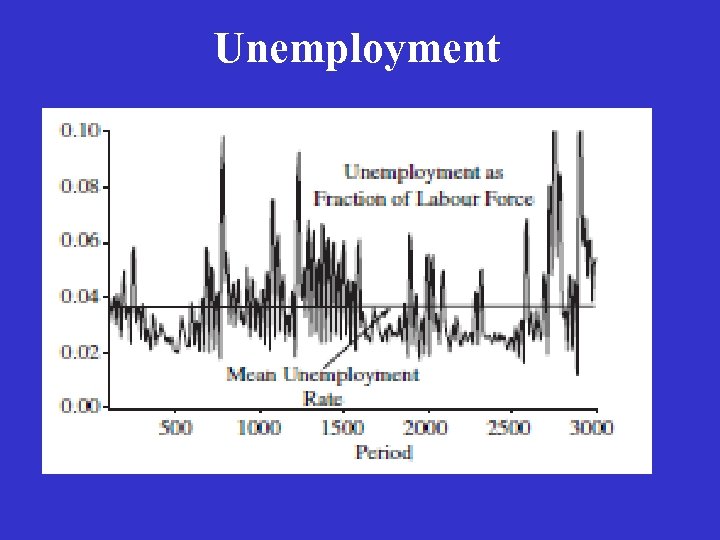

Main Results The dynamical system satisfies the complex systems counterpart to stability and uniqueness: excess supply in each sector; excess labor demand, as well as excess labor supply in each period; labor demand differs from labor supply by only a few percent; Prices are approximately equal to production costs; The wage rate in each sector is fairly stable, and wages are approximately equal across sectors. There is a considerable level of fluctuation in price and quantity series, even though there are no aggregate stochastic shocks to the system.

Price Stability with Excursions

Price Stability with Excursions

Excess Demand Supply

Profits

Unemployment

Unemployment

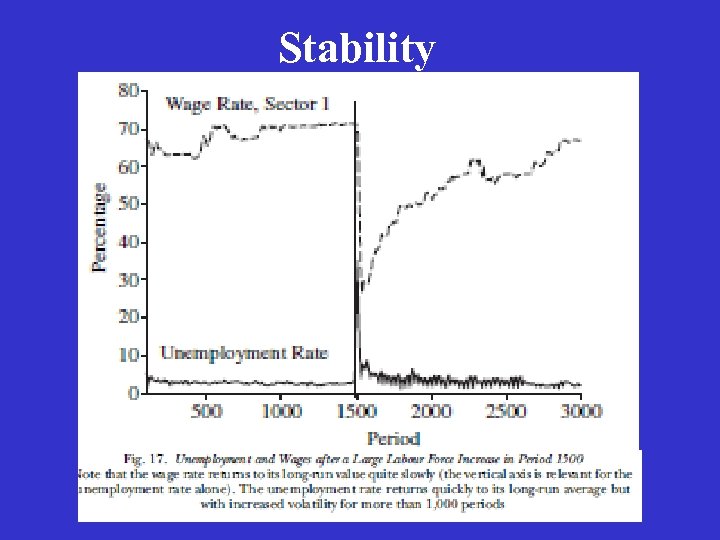

Stability

percent Stability • The vertical axis shows percentage efficiency.

Stability

Conclusion Simple market exchange is robust to shocks, whereas economies with sophisticated institutions can exhibit considerable fragility. The fragility of sophisticated market competition exchange is based on endogenous random shocks and does not require exogenous shocks. Agent-based simulation models provide insights into the dynamic performance of market economies.

ec488a2aacfdf0f0d15266ba7811d035.ppt