collocability and phraseology.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 34

THE PROBLEMS OF COLLOCABILITY AND PHRASEOLOGY

The vocabulary of any language consists not only of words but also of different word-groups and expressions. Word groups can have different character: free word-combinations (collocations) (a nice cat) and set-expressions (to rain cats and dogs).

A word group may be defined as the largest two facet lexical unit comprising more than one word. The two main linguistic factors that unite words in groups are: the lexical valency and grammatical valency of words.

Lexical Valency Lexical valency (or collocability) is the aptness of a word to appear in various combinations. E. g. , problem (n) + (adj. ) serious, major, financial, personal Problem can be used in word combinations: to cause a problem, to sort out a problem, to tackle / address a problem, a problem occurs. Words habitually collocated in speech tend to constitute a cliché: no problem, a problem child, that’s not my (your) problem

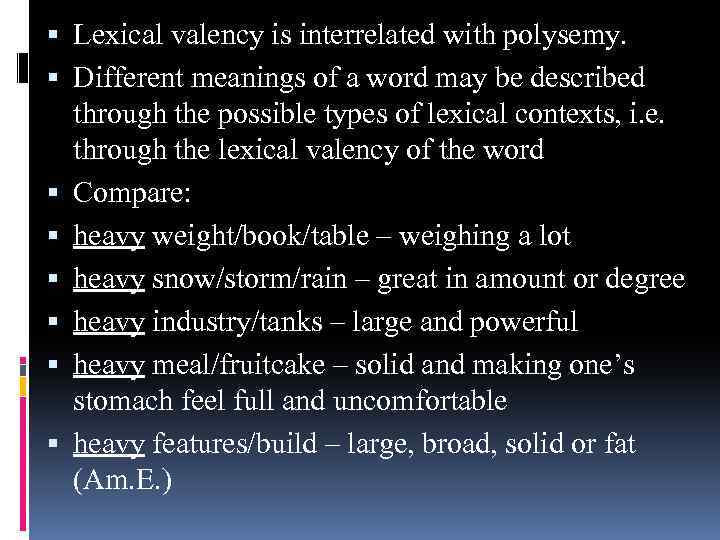

Lexical valency is interrelated with polysemy. Different meanings of a word may be described through the possible types of lexical contexts, i. e. through the lexical valency of the word Compare: heavy weight/book/table – weighing a lot heavy snow/storm/rain – great in amount or degree heavy industry/tanks – large and powerful heavy meal/fruitcake – solid and making one’s stomach feel full and uncomfortable heavy features/build – large, broad, solid or fat (Am. E. )

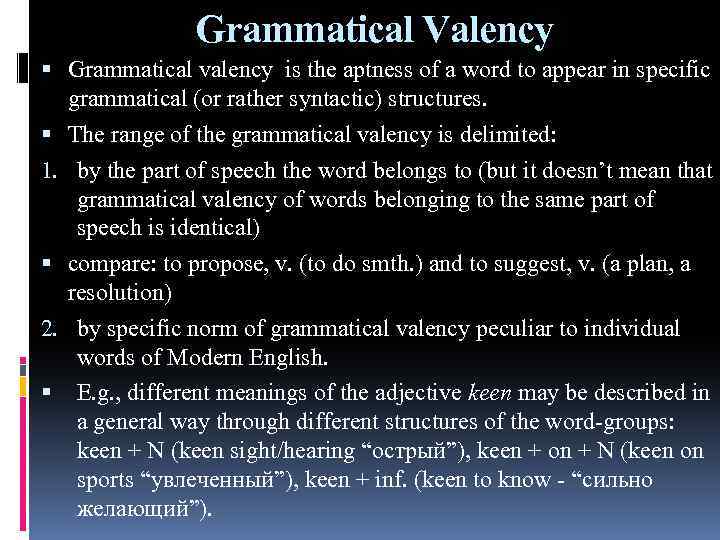

Grammatical Valency Grammatical valency is the aptness of a word to appear in specific grammatical (or rather syntactic) structures. The range of the grammatical valency is delimited: 1. by the part of speech the word belongs to (but it doesn’t mean that grammatical valency of words belonging to the same part of speech is identical) compare: to propose, v. (to do smth. ) and to suggest, v. (a plan, a resolution) 2. by specific norm of grammatical valency peculiar to individual words of Modern English. E. g. , different meanings of the adjective keen may be described in a general way through different structures of the word-groups: keen + N (keen sight/hearing “острый”), keen + on + N (keen on sports “увлеченный”), keen + inf. (keen to know - “сильно желающий”).

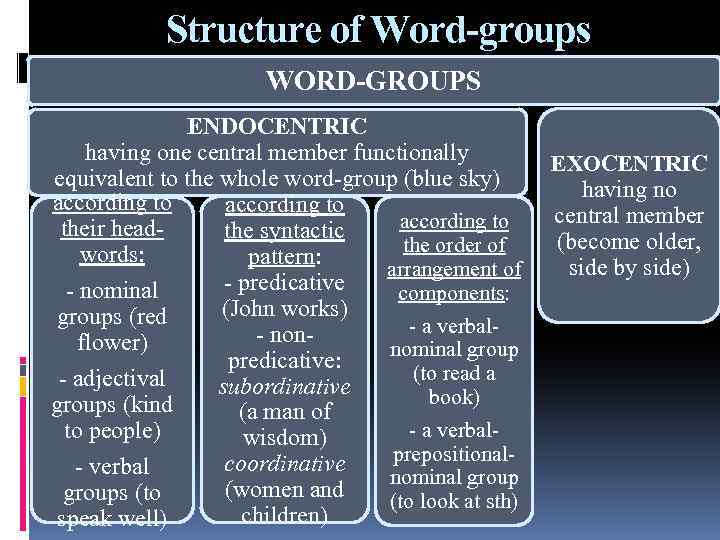

Structure of Word-groups WORD-GROUPS ENDOCENTRIC having one central member functionally equivalent to the whole word-group (blue sky) according to their headthe syntactic the order of words: pattern: arrangement of - predicative - nominal components: (John works) groups (red - a verbal- nonflower) nominal group predicative: (to read a - adjectival subordinative book) groups (kind (a man of - a verbalto people) wisdom) prepositionalcoordinative - verbal nominal group (women and groups (to look at sth) children) speak well) EXOCENTRIC having no central member (become older, side by side)

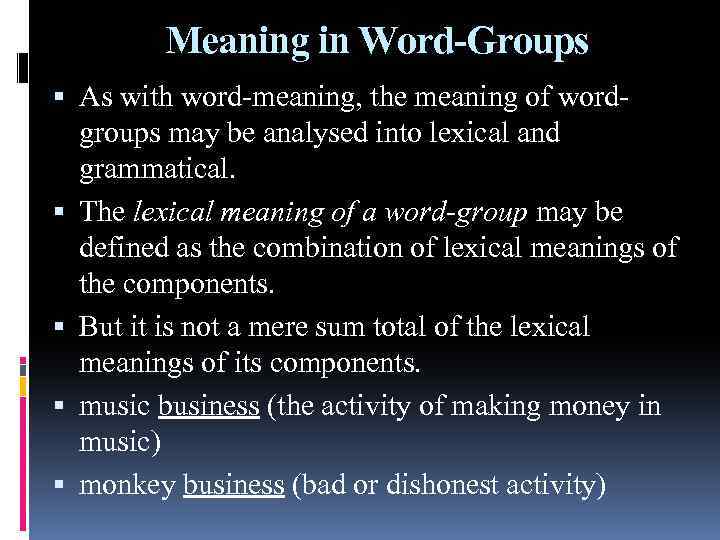

Meaning in Word-Groups As with word-meaning, the meaning of wordgroups may be analysed into lexical and grammatical. The lexical meaning of a word-group may be defined as the combination of lexical meanings of the components. But it is not a mere sum total of the lexical meanings of its components. music business (the activity of making money in music) monkey business (bad or dishonest activity)

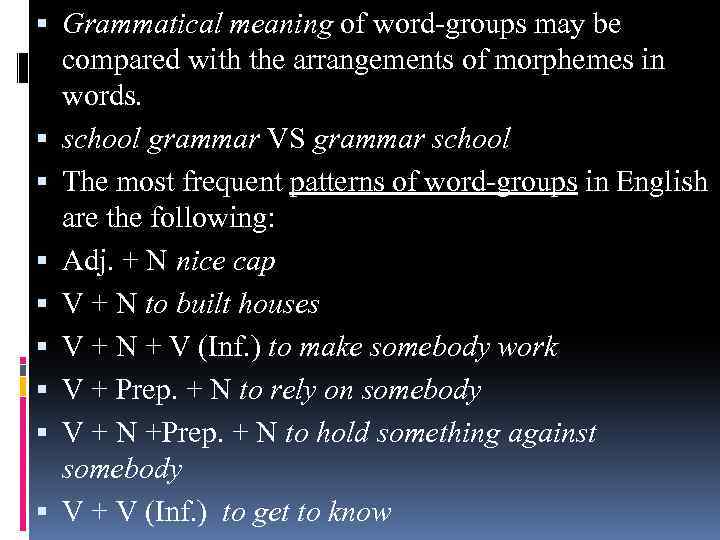

Grammatical meaning of word-groups may be compared with the arrangements of morphemes in words. school grammar VS grammar school The most frequent patterns of word-groups in English are the following: Adj. + N nice cap V + N to built houses V + N + V (Inf. ) to make somebody work V + Prep. + N to rely on somebody V + N +Prep. + N to hold something against somebody V + V (Inf. ) to get to know

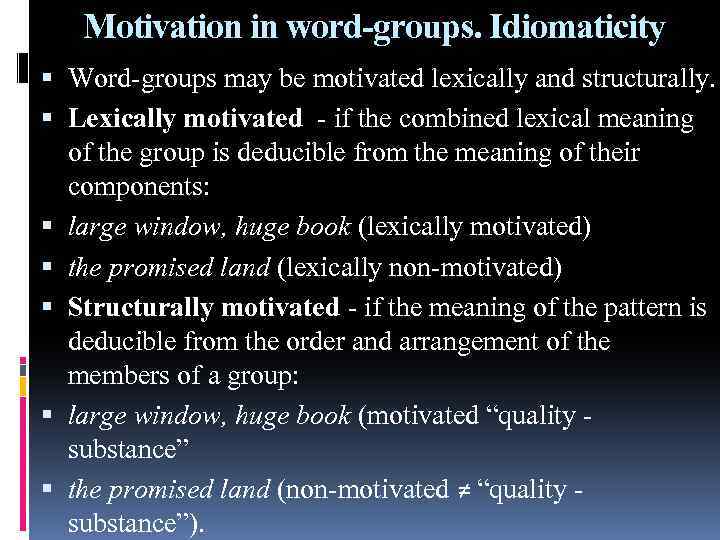

Motivation in word-groups. Idiomaticity Word-groups may be motivated lexically and structurally. Lexically motivated - if the combined lexical meaning of the group is deducible from the meaning of their components: large window, huge book (lexically motivated) the promised land (lexically non-motivated) Structurally motivated - if the meaning of the pattern is deducible from the order and arrangement of the members of a group: large window, huge book (motivated “quality substance” the promised land (non-motivated ≠ “quality substance”).

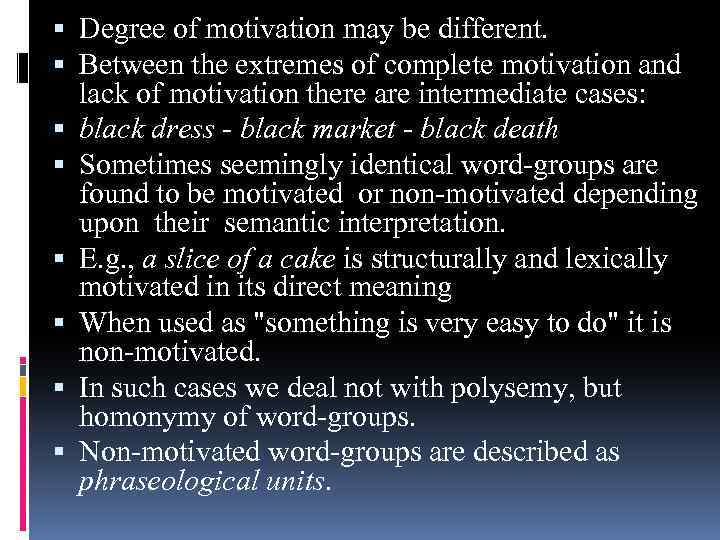

Degree of motivation may be different. Between the extremes of complete motivation and lack of motivation there are intermediate cases: black dress - black market - black death Sometimes seemingly identical word-groups are found to be motivated or non-motivated depending upon their semantic interpretation. E. g. , a slice of a cake is structurally and lexically motivated in its direct meaning When used as "something is very easy to do" it is non-motivated. In such cases we deal not with polysemy, but homonymy of word-groups. Non-motivated word-groups are described as phraseological units.

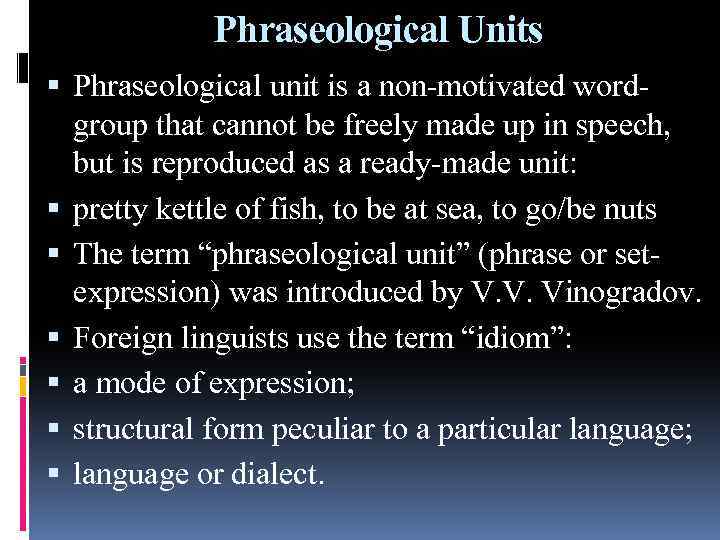

Phraseological Units Phraseological unit is a non-motivated wordgroup that cannot be freely made up in speech, but is reproduced as a ready-made unit: pretty kettle of fish, to be at sea, to go/be nuts The term “phraseological unit” (phrase or setexpression) was introduced by V. V. Vinogradov. Foreign linguists use the term “idiom”: a mode of expression; structural form peculiar to a particular language; language or dialect.

Semantic Approach to Phraseology The essential features of Ph. U are stability of lexical components and lack of motivation. Member-words of Ph. U are always reproduced as single unchangeable collocations, unlike components of free word-groups which may vary according to the needs of communication (red/yellow/blue/white flower : : red-tape “bureaucratic methods”). The meaning of a Ph. U exists as a ready-made unit, grammatical structure being stable to a certain extent as well (red tape “bureaucratic methods” > red tapes “tapes of red colour”).

According to the degree of idiomaticity Ph. U are classified into: Phraseological fusions -completely non-motivated word-groups (kick the bucket - “die”). Phraseological unities - are partly non-motivated as their meaning can usually be perceived through the metaphoric meaning of the whole Ph. U (to show one’s teeth, to wash one’s dirty linen in the public). Phraseological collocations - are motivated but they are made up of words possessing specific lexical valency (> stability in such word-groups). Variability of member-words is strictly limited (take a liking or take fancy but not take hatred).

But the criterion of idiomaticity is criticized because it cannot always help to single out phraseological units from other word-groups and in borderline cases within phraseological units themselves (between unities and collocations, collocations and free word-groups). E. g. have in mind, make up one's mind in some dictionaries are marked as idioms, in others as free phrases. The criterion of stability is also criticized as there can be substitutions: hit below the belt > strike below the belt go to hell > go to the devil /pot /pigs and whistles Besides, stability of lexical components presupposes lack of motivation, but such word groups as shrug one's shoulders do not allow any substitution, though the meaning is motivated.

Functional Approach to Phraseology Prof. A. I. Smirnitsky: word-equivalent. The approach assumes that Ph. Us may be defined as specific word-groups functioning as word equivalents. They are characterized by the following features: The denotational meaning of a Ph. U belongs to the word -group as a single semantically inseparable unit. E. g. , the meanings of the member-words dog’s and breakfast taken in isolation are in no way connected with the meaning of the phrase a dog’s breakfast “халтура, неумело или небрежно сделанная работа”: The whole business was a complete dog’s breakfast.

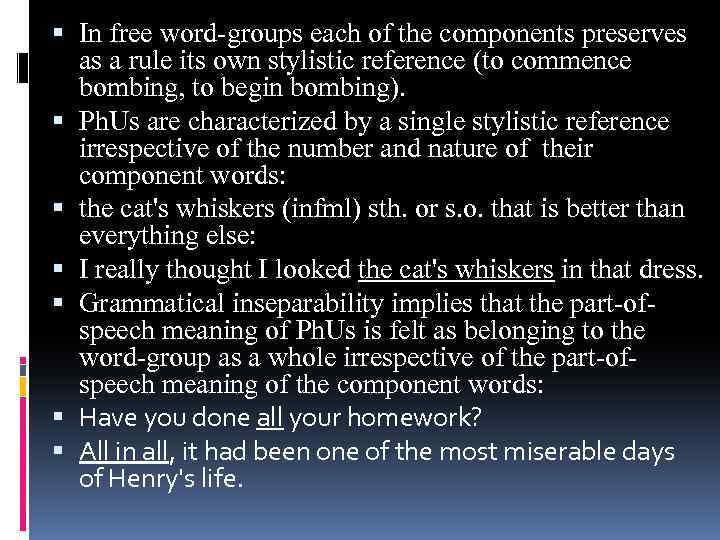

In free word-groups each of the components preserves as a rule its own stylistic reference (to commence bombing, to begin bombing). Ph. Us are characterized by a single stylistic reference irrespective of the number and nature of their component words: the cat's whiskers (infml) sth. or s. o. that is better than everything else: I really thought I looked the cat's whiskers in that dress. Grammatical inseparability implies that the part-ofspeech meaning of Ph. Us is felt as belonging to the word-group as a whole irrespective of the part-ofspeech meaning of the component words: Have you done all your homework? All in all, it had been one of the most miserable days of Henry's life.

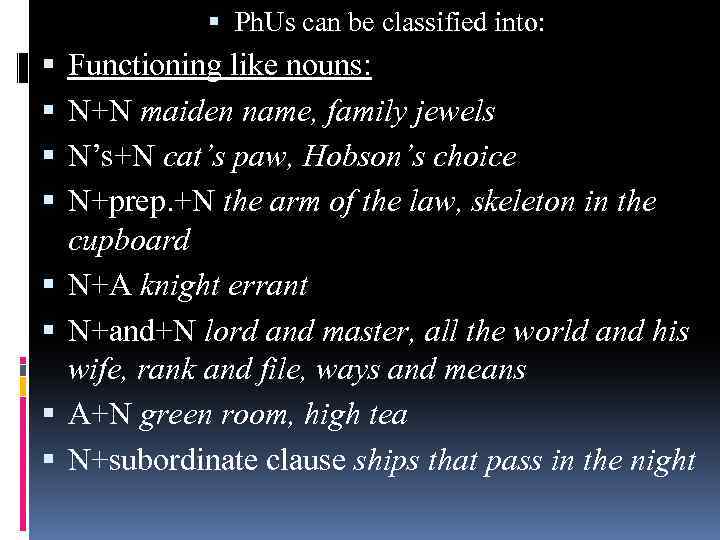

Ph. Us can be classified into: Functioning like nouns: N+N maiden name, family jewels N’s+N cat’s paw, Hobson’s choice N+prep. +N the arm of the law, skeleton in the cupboard N+A knight errant N+and+N lord and master, all the world and his wife, rank and file, ways and means A+N green room, high tea N+subordinate clause ships that pass in the night

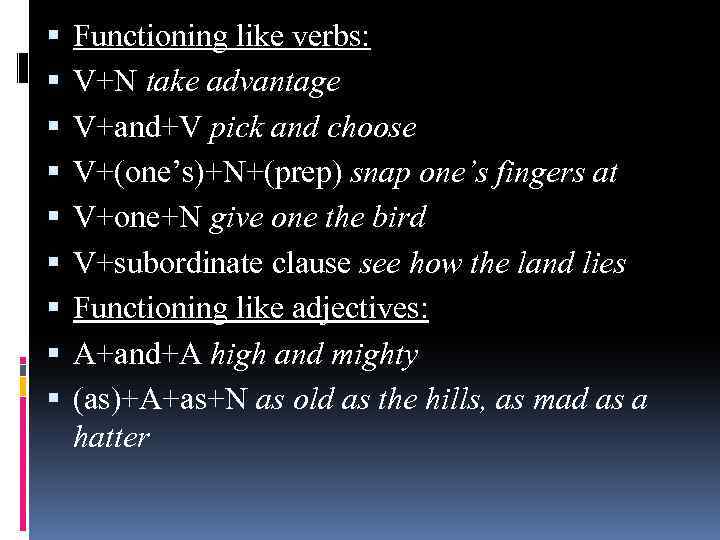

Functioning like verbs: V+N take advantage V+and+V pick and choose V+(one’s)+N+(prep) snap one’s fingers at V+one+N give one the bird V+subordinate clause see how the land lies Functioning like adjectives: A+and+A high and mighty (as)+A+as+N as old as the hills, as mad as a hatter

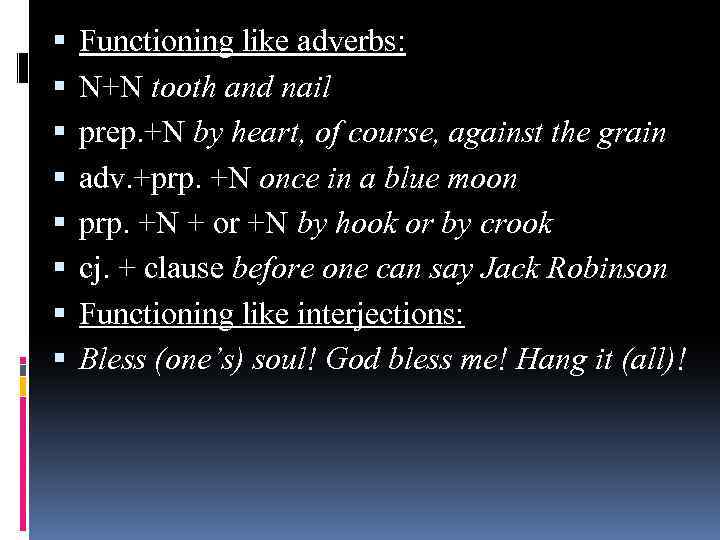

Functioning like adverbs: N+N tooth and nail prep. +N by heart, of course, against the grain adv. +prp. +N once in a blue moon prp. +N + or +N by hook or by crook cj. + clause before one can say Jack Robinson Functioning like interjections: Bless (one’s) soul! God bless me! Hang it (all)!

The debatable points of the approach are: the criterion of function is not reliable when used with a view to singling out Ph. U from among other more or less idiomatic word-groups as the same word-group may function in some utterances as an inseparable group and in others as a separable (She took care of everything. Great care was taken to keep the children happy); it doesn’t provide an objective criterion for the bulk of word-groups occupying an intermediate position between free word-groups and highly idiomatic Ph. Us.

Contextual Approach to Phraseology The term used is idiom which implies that the essential feature of the linguistic units under consideration is idiomaticity or lack of motivation. This approach is suggested by Prof. N. N. Amosova. While free word-groups make up variable contexts (small town/room/audience), Ph. Us are to be defined through a non-variable, fixed context (a girl Friday “помощница, “правая рука”, надёжный работник”, give and take “взаимные уступки, компромисс”, to hold water “быть последовательным, логичным, звучать убедительно”).

Ph. Us are subdivided into: Phrasemes - two-member word-groups in which one of the members has specialized meaning dependent on the second component (small hours - “the early hours of the morning from about 1 a. m. to 4 a. m. ”, the component hours serves as the only clue to this particular meaning of the 1 st component). Idioms - are characterized by the idiomaticity of the whole word-group and the impossibility of attaching meaning to the members of the group taken in isolation (mare’s nest - “a discovery which proves false or worthless”). The debatable points are: 1) non-variability of context does not necessarily imply specialized meaning of the component or components of the word-group; 2) Some word-groups possessing a certain degree of idiomaticity are referred to traditional collocations.

All the three approaches are sufficient to single out the extreme cases: highly idiomatic Ph. Us and free word-groups. The bulk of word-groups possessing different degrees of idiomaticity cannot be decided upon with certainty by applying the criteria available in linguistic science.

Prof. Kunin’s Approach The main features of the approach are: 1. Phraseology is regarded as a self-contained branch of linguistics and not as a part of lexicology. 2. Phraseology deals with a phraseological subsystem of language and not with isolated phraseological units. 3. Phraseology is concerned with all types of setexpressions.

4. Set-expressions are divided into three classes: phraseological units (e. g. red tape, mare's nest, etc. ), phraseomatic units (e. g. win a victory, launch a campaign, etc. ) and border-line cases belonging to the mixed class. The main distinction between the first and the second classes is semantic: phraseological units have fully or partially transferred meanings while components of phraseomatic units are used in their literal meanings.

5. Phraseological and phraseomatic units are not regarded as word-equivalents but some of them are treated as word correlates. 6. Phraseological and phraseomatic units are set-expressions and their phraseological stability distinguishes them from free phrases and compound words.

7. Phraseological and phraseomatic units are made up of words of different degree of wordness depending on the type of setexpressions they are used in. (Cf. small hours and my goodness) Their structural separateness, an important factor of their stability, distinguishes them from compound words (Cf. blackbird and black market). Other aspects of their stability are: stability of use, lexical stability and semantic stability.

8. Stability of use means that set-expressions are reproduced ready-made and not created in speech. 9. Lexical stability means that the components of set expressions are either irreplaceable (e. g. red tape, mare's nest) or partly replaceable within the bounds of phraseological or phraseomatic variance: lexical: a skeleton in the cupboard - a skeleton in the closet grammatical: to be in deep water - to be in deep waters positional: head over ears - over head and ears quantitative: to lead smb. a dance - to lead smb. a pretty dance mixed variants: raise (stir up) a hornets' nest - arouse (stir up) the nest of hornets.

10. Semantic stability is based on the lexical stability of set-expressions. Even when occasional changes are introduced the meaning of a set-expression is preserved. So, in spite of all occasional changes phraseological and phraseomatic units (as distinguished from free phrases) remain semantically invariant or are destroyed: to raise the question (free phrase) - to pop the question (set-expression – to ask somebody to marry you (humorous)).

Features Enhancing Unity and Stability of Set-Expressions Why do we remember set-expressions so easily? Factors: rhythm: far and wide, heart and soul reiteration: more and more, on and on, one by one alliteration: part and parcel, rack and ruin rhyme: fair and square, by hook or by crook semantic stylistic features (simile, contrast, metaphor, synonymy): as like as two peas; from beginning to end; a lame duck, to swallow a pill; by leaps and bounds, proud and haughty.

Are Proverbs Set-Expressions? Proverb - is a short familiar epigrammatic saying expressing popular wisdom, a truth or a moral lesson in a concise and imaginative way. Arguments “for”: Proverbs have much in common with setexpressions: Their lexical components are constant, their meaning is traditional and mostly figurative, they are introduced in speech ready-made, they often form the basis of set-expressions the last straw breaks the camel’s back : : the last straw

Both set-expressions and proverbs are sometimes split and changed for humorous purposes: All is not gold that glitters : : It will be an age not perhaps of gold, but at least of glitter : : golden age Arguments “against”: 1) (Morozova) set-expressions in contrast to proverbs correlate with some concept, but not with the whole situation; 2) (Amosova) proverbs are the units of communication (sentences) and can’t be used regularly as parts of sentences.

СПАСИБО ЗА ВНИМАНИЕ!

collocability and phraseology.pptx