Colonic functions.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 42

The Physiology of Human Defecation S. Palit • P. J. Lunniss • S. M. Scott The Physiology of Human Defecation // Dig Dis Sci (2012) 57: 1445– 1464

The Physiology of Human Defecation S. Palit • P. J. Lunniss • S. M. Scott The Physiology of Human Defecation // Dig Dis Sci (2012) 57: 1445– 1464

Colonic functions • Colonic functions relevant to normal defecation include: • absorption of water from intraluminal contents, net antegrade • propulsion of colonic contents at an adequate rate, • and temporary storage of feces until convenient to expel them.

Colonic functions • Colonic functions relevant to normal defecation include: • absorption of water from intraluminal contents, net antegrade • propulsion of colonic contents at an adequate rate, • and temporary storage of feces until convenient to expel them.

The Phases of Defecation • (1) the basal phase, • (2) a pre-defecatory phase, leading to generation of a defecatory urge, • (3) the expulsive phase, during which • evacuation occurs, and finally, • (4) termination of defecation

The Phases of Defecation • (1) the basal phase, • (2) a pre-defecatory phase, leading to generation of a defecatory urge, • (3) the expulsive phase, during which • evacuation occurs, and finally, • (4) termination of defecation

The basal phase

The basal phase

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic motor activity shows a circadian pattern, it increases after awakening [117] and is higher during the day compared to the night [117– 120]. • Colonic activity also increases after meals [117, 120, 121].

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic motor activity shows a circadian pattern, it increases after awakening [117] and is higher during the day compared to the night [117– 120]. • Colonic activity also increases after meals [117, 120, 121].

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic motor activity is characterized by brief (phasic) • contractions and also sustained (tonic) contractions (best measured with a barostat) [127].

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic motor activity is characterized by brief (phasic) • contractions and also sustained (tonic) contractions (best measured with a barostat) [127].

Phasic contractions • Phasic contractions are further classified as propagating • non-propagating contractions: • They have a frequency of between 2 and 4 cycles per minute [141] and an amplitude of between 5 and 50 mm Hg) • The duration of these contractions caneither be short (15 s) or long (15– 60 s)

Phasic contractions • Phasic contractions are further classified as propagating • non-propagating contractions: • They have a frequency of between 2 and 4 cycles per minute [141] and an amplitude of between 5 and 50 mm Hg) • The duration of these contractions caneither be short (15 s) or long (15– 60 s)

Role of non-propagated activity • Although the role of non-propagated activity in luminal transport is not fully understood [141], • it is thought to aid mixing of intraluminal contents by local propulsion [145, 146] and retropulsion [147] of the fecal bolus.

Role of non-propagated activity • Although the role of non-propagated activity in luminal transport is not fully understood [141], • it is thought to aid mixing of intraluminal contents by local propulsion [145, 146] and retropulsion [147] of the fecal bolus.

Non-propagating contractions • Non-propagating contractions: • They have a frequency of between 2 and 4 • cycles per minute [141] and an amplitude of between 5 and 50 mm Hg) • The duration of these contractions can either be short (15 s) or long (15– 60 s) • These contractions can either be rhythmic (occurring at frequencies of 2– 3 cycles/min or 6– 8 cycles/min) or arrhythmic

Non-propagating contractions • Non-propagating contractions: • They have a frequency of between 2 and 4 • cycles per minute [141] and an amplitude of between 5 and 50 mm Hg) • The duration of these contractions can either be short (15 s) or long (15– 60 s) • These contractions can either be rhythmic (occurring at frequencies of 2– 3 cycles/min or 6– 8 cycles/min) or arrhythmic

Propagated colonic activity • Propagated colonic activity can be retrograde (oralpropagation) • or antegrade (aboral propagation). • These waves, known as high amplitude propagated sequences (HAPSs; or contractions: HAPCs) • have been widely and variously defined [116, 148], but • typically have amplitudes[100 mm. Hg [147, 149, 150]. • In • adults, HAPCs occur, on average, 5– 6 times a day (range 2– 24) [116],

Propagated colonic activity • Propagated colonic activity can be retrograde (oralpropagation) • or antegrade (aboral propagation). • These waves, known as high amplitude propagated sequences (HAPSs; or contractions: HAPCs) • have been widely and variously defined [116, 148], but • typically have amplitudes[100 mm. Hg [147, 149, 150]. • In • adults, HAPCs occur, on average, 5– 6 times a day (range 2– 24) [116],

The distance of propagation • The distance of propagation correlates with the proximity of the site of origin to the caecum [120, 121, 147]. • One study found that only a third of the HAPSs reached the anus, the remainder terminating at the rectosigmoid region [117]. • HAPSs are often temporally associated with defecation [117, 148, 151] or passing flatus [117]. • They help in propulsion of the fecal bolus [147] and are the manometric equivalent of ‘‘mass movements’’ noted radiologically (i. e. a rapid shift of a considerable volume of intraluminal content) [152, 153].

The distance of propagation • The distance of propagation correlates with the proximity of the site of origin to the caecum [120, 121, 147]. • One study found that only a third of the HAPSs reached the anus, the remainder terminating at the rectosigmoid region [117]. • HAPSs are often temporally associated with defecation [117, 148, 151] or passing flatus [117]. • They help in propulsion of the fecal bolus [147] and are the manometric equivalent of ‘‘mass movements’’ noted radiologically (i. e. a rapid shift of a considerable volume of intraluminal content) [152, 153].

Propagated colonic activity • The majority of the colonic propagated activity is • characterized by low amplitude propagated sequences (PSs; or low amplitude propagated contractions: LAPCs). • These typically have amplitude 50 mm. Hg [156], occur 40– 120 times in a 24 h period [117, 147, 157], and propagate for distances22. 5 cm [121].

Propagated colonic activity • The majority of the colonic propagated activity is • characterized by low amplitude propagated sequences (PSs; or low amplitude propagated contractions: LAPCs). • These typically have amplitude 50 mm. Hg [156], occur 40– 120 times in a 24 h period [117, 147, 157], and propagate for distances22. 5 cm [121].

The sigmoid colon • The sigmoid colon primarily exhibits cyclical bursts of contractions (though they occur throughout the rest of the colon also), called motor complexes (MC) or ‘‘periodic colonic motor activity’’; • These may be important in modulating the delivery of fecal material into the rectum. • These MCs typically have amplitudes of 15– 60 mm Hg, last 3– 30 min, and recur at 80– 90 min intervals [159].

The sigmoid colon • The sigmoid colon primarily exhibits cyclical bursts of contractions (though they occur throughout the rest of the colon also), called motor complexes (MC) or ‘‘periodic colonic motor activity’’; • These may be important in modulating the delivery of fecal material into the rectum. • These MCs typically have amplitudes of 15– 60 mm Hg, last 3– 30 min, and recur at 80– 90 min intervals [159].

Rectal Motor Activity • Rectal motor activity, like the sigmoid, is characterized by recurrent motor complexes. • The frequency of rectal MCs appears unaffected by meal intake [117]. • The role of these motor activities is not fully understood [141]. • However, rectal MCs are seen to propagate in a retrograde direction [167]; it has thus been postulated they help to keep the rectum empty by acting as a ‘‘braking mechanism’’ to untimely flow of colonic contents [167].

Rectal Motor Activity • Rectal motor activity, like the sigmoid, is characterized by recurrent motor complexes. • The frequency of rectal MCs appears unaffected by meal intake [117]. • The role of these motor activities is not fully understood [141]. • However, rectal MCs are seen to propagate in a retrograde direction [167]; it has thus been postulated they help to keep the rectum empty by acting as a ‘‘braking mechanism’’ to untimely flow of colonic contents [167].

Pelvic Floor and Puborectalis Activity • At rest, the levator ani, the puborectalis, and the external anal sphincter remain in a state of continuous contraction. • This reflex is known as the postural reflex [171] and it helps to support the weight of the pelvic viscera. • The reflex is maintained through the lower lumbar and sacral spinal cord [171].

Pelvic Floor and Puborectalis Activity • At rest, the levator ani, the puborectalis, and the external anal sphincter remain in a state of continuous contraction. • This reflex is known as the postural reflex [171] and it helps to support the weight of the pelvic viscera. • The reflex is maintained through the lower lumbar and sacral spinal cord [171].

Pelvic Floor and Puborectalis Activity • At rest, the contractile traction of puborectalis maintains the anorectal angle (angle between the long axis of the rectum and the long axis of the anal canal) at approximately 90 [175]. • While this angulation helps in preservation of continence [176], increased acuity has been related to obstructed defecation [177, 178].

Pelvic Floor and Puborectalis Activity • At rest, the contractile traction of puborectalis maintains the anorectal angle (angle between the long axis of the rectum and the long axis of the anal canal) at approximately 90 [175]. • While this angulation helps in preservation of continence [176], increased acuity has been related to obstructed defecation [177, 178].

Anal Canal Activity • At rest, the anal canal remains closed to preserve continence. • The anal sphincter complex is extremely dynamic • and is influenced by a variety of reflexes and modulation by higher centers in such a way that rather than acting as a passive barrier, it provides an airtight seal at all times except when the subject wants to pass flatus or defecate [179].

Anal Canal Activity • At rest, the anal canal remains closed to preserve continence. • The anal sphincter complex is extremely dynamic • and is influenced by a variety of reflexes and modulation by higher centers in such a way that rather than acting as a passive barrier, it provides an airtight seal at all times except when the subject wants to pass flatus or defecate [179].

Anal Canal Activity • The anal canal is normally closed by the tonic activity of the internal and external anal sphincters, together with the anal cushions. • The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is chiefly responsible for continence at rest [180], and is predominantly composed of slow-twitch, fatigueresistant smooth muscles. • Electromyographic study of the IAS demonstrates a constant activity at rest [181– 183], which is unaffected by respiration or administration of a general anaesthesia [184].

Anal Canal Activity • The anal canal is normally closed by the tonic activity of the internal and external anal sphincters, together with the anal cushions. • The internal anal sphincter (IAS) is chiefly responsible for continence at rest [180], and is predominantly composed of slow-twitch, fatigueresistant smooth muscles. • Electromyographic study of the IAS demonstrates a constant activity at rest [181– 183], which is unaffected by respiration or administration of a general anaesthesia [184].

Anal Canal Activity • The anal canal epithelium is lined by highly sensitive nerve endings derived from sensory, motor and autonomic nerves, in addition to the enteric nervous system [63]. • The anal sensory area contains specialized sensory end organs, including Krause end bulbs, Golgi Mazzoni bodies, genital corpuscles, Meisnner’s corpuscles, and Pacinian corpuscles

Anal Canal Activity • The anal canal epithelium is lined by highly sensitive nerve endings derived from sensory, motor and autonomic nerves, in addition to the enteric nervous system [63]. • The anal sensory area contains specialized sensory end organs, including Krause end bulbs, Golgi Mazzoni bodies, genital corpuscles, Meisnner’s corpuscles, and Pacinian corpuscles

The Pre-Expulsive Phase

The Pre-Expulsive Phase

The Pre-Expulsive Phase • During this phase, specific motor events occur, which culminate in an awareness by the subject of an urge to defecate, the ‘‘call to stool. ’’

The Pre-Expulsive Phase • During this phase, specific motor events occur, which culminate in an awareness by the subject of an urge to defecate, the ‘‘call to stool. ’’

Origin of the Defecatory Urge • • ‘‘call to stool. ’: It is likely that the colon, rectum, anus, extra-rectal tissue, and the puborectalis may all contribute to varying degrees (see below).

Origin of the Defecatory Urge • • ‘‘call to stool. ’: It is likely that the colon, rectum, anus, extra-rectal tissue, and the puborectalis may all contribute to varying degrees (see below).

Role of the Colon • In healthy subjects, there is a close relationship between HAPSs and urge to evacuate, • A relationship that is often absent in patients with constipation [197].

Role of the Colon • In healthy subjects, there is a close relationship between HAPSs and urge to evacuate, • A relationship that is often absent in patients with constipation [197].

Role of the Colon • During the pre-expulsive phase, propagated sequences often start as unperceived colonic contractions in the proximal colon, and migrate distally while increasing in amplitude to become a ‘‘full blown’’ HAPS, that is then associated with an urge to defecate [148]. • It is feasible that increased colonic activity seen during the preexpulsive phase leads to movement of colonic contents distally, which in turn stimulates distal colonic afferents (or indeed perhaps rectal) [148], possibly by distension, • resulting in sensory perception.

Role of the Colon • During the pre-expulsive phase, propagated sequences often start as unperceived colonic contractions in the proximal colon, and migrate distally while increasing in amplitude to become a ‘‘full blown’’ HAPS, that is then associated with an urge to defecate [148]. • It is feasible that increased colonic activity seen during the preexpulsive phase leads to movement of colonic contents distally, which in turn stimulates distal colonic afferents (or indeed perhaps rectal) [148], possibly by distension, • resulting in sensory perception.

Role of the Rectum, the Pelvic Floor, and the Extra -Rectal Tissues • The rectum is regarded as the primary site of origin of the defecatory urge. • Gradual distension of the rectum produces a graded sensory response starting with an initial awareness of filling [200]. • Rectal-type sensation similar to a desire to defecate can be elicited by distension of the bowel up to 15 cm from the anal verge, whereas distension above this level typically leads to a colonic-type sensation similar to wind pain or suprapubic pain [199].

Role of the Rectum, the Pelvic Floor, and the Extra -Rectal Tissues • The rectum is regarded as the primary site of origin of the defecatory urge. • Gradual distension of the rectum produces a graded sensory response starting with an initial awareness of filling [200]. • Rectal-type sensation similar to a desire to defecate can be elicited by distension of the bowel up to 15 cm from the anal verge, whereas distension above this level typically leads to a colonic-type sensation similar to wind pain or suprapubic pain [199].

Role of the Rectum, the Pelvic Floor, and the Extra -Rectal Tissues • In support of an extra-rectal origin of urge sensation, it has been shown that defecatory desire can be provoked by stimulating nerve endings and stretch receptors in pelvic floor muscles including the puborectalis, and from structures adjacent to the rectum [205]. • In summary, based on these observations, it can be concluded that both the rectum and the pelvic floor have a role in the generation of normal filling sensation, and also in the urge to defecate.

Role of the Rectum, the Pelvic Floor, and the Extra -Rectal Tissues • In support of an extra-rectal origin of urge sensation, it has been shown that defecatory desire can be provoked by stimulating nerve endings and stretch receptors in pelvic floor muscles including the puborectalis, and from structures adjacent to the rectum [205]. • In summary, based on these observations, it can be concluded that both the rectum and the pelvic floor have a role in the generation of normal filling sensation, and also in the urge to defecate.

Role of the Anal Canal • Thus the anus informs the subject in a direct somatic way of the contents impinging upon it.

Role of the Anal Canal • Thus the anus informs the subject in a direct somatic way of the contents impinging upon it.

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic Motor Activity (Up to 1 h Before Defecation)

Colonic Motor Activity • Colonic Motor Activity (Up to 1 h Before Defecation)

The Expulsive Phase

The Expulsive Phase

The Expulsive Phase • Facilitated by the sampling reflex, and in the presence of a defecatory urge, if a conscious decision to evacuate is made, rectal contents and a variable quantity of colonic contents are evacuated during this phase. • Efficacy of expulsion may be influenced by additional voluntary straining and assumption of an appropriate posture. • The final common path is effected by an elevation in intrarectal pressure and relaxation of the pelvic floor and anal canal.

The Expulsive Phase • Facilitated by the sampling reflex, and in the presence of a defecatory urge, if a conscious decision to evacuate is made, rectal contents and a variable quantity of colonic contents are evacuated during this phase. • Efficacy of expulsion may be influenced by additional voluntary straining and assumption of an appropriate posture. • The final common path is effected by an elevation in intrarectal pressure and relaxation of the pelvic floor and anal canal.

The Expulsive Phase • Colonic Activity: • During defecation, a variable portion of the colon, as well as the rectum, empties [266]. • A scintigraphic study of defecation in 11 healthy volunteers showed that the mean percentage of segmental evacuation was: right colon 20%, left colon 32%, and rectum 66% [266]. • In healthy adults, 35– 40% of all HAPSs in a day occur during or immediately preceding defecation [117, 126], and virtually all episodes of defecation are associated with HAPSs [121, 267]; this is compatible with the radiological concept of mass movement [152, 153].

The Expulsive Phase • Colonic Activity: • During defecation, a variable portion of the colon, as well as the rectum, empties [266]. • A scintigraphic study of defecation in 11 healthy volunteers showed that the mean percentage of segmental evacuation was: right colon 20%, left colon 32%, and rectum 66% [266]. • In healthy adults, 35– 40% of all HAPSs in a day occur during or immediately preceding defecation [117, 126], and virtually all episodes of defecation are associated with HAPSs [121, 267]; this is compatible with the radiological concept of mass movement [152, 153].

Rectal Activity • Normal defecation is thus associated with an increase in intra-rectal pressure [269, 270] and a necessary relaxation of the anal canal resulting in decreased anal pressure.

Rectal Activity • Normal defecation is thus associated with an increase in intra-rectal pressure [269, 270] and a necessary relaxation of the anal canal resulting in decreased anal pressure.

Pelvic Floor Activity • During this phase, there is reflex inhibition of pelvic floor tonic activity [274].

Pelvic Floor Activity • During this phase, there is reflex inhibition of pelvic floor tonic activity [274].

Anal Canal Activity • During the expulsive phase, anal canal relaxation occurs. • Internal anal sphincter relaxation occurs involuntarily in response to rectal distension and the relaxation is proportional to the intra-rectal pressure [180, 182]. • After assuming a posture convenient for defecation, the subject strains by contracting the abdominal muscles and diaphragm against a closed glottis (Valsalva maneuver). • This is associated with relaxation of the external anal sphincter.

Anal Canal Activity • During the expulsive phase, anal canal relaxation occurs. • Internal anal sphincter relaxation occurs involuntarily in response to rectal distension and the relaxation is proportional to the intra-rectal pressure [180, 182]. • After assuming a posture convenient for defecation, the subject strains by contracting the abdominal muscles and diaphragm against a closed glottis (Valsalva maneuver). • This is associated with relaxation of the external anal sphincter.

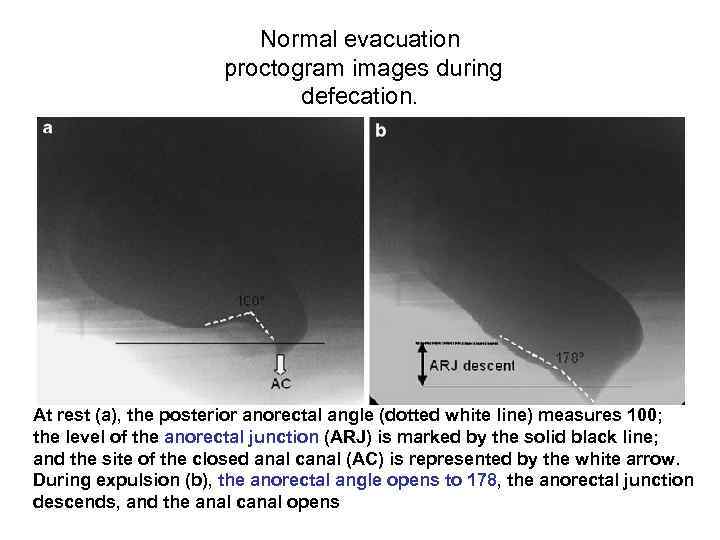

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. At rest (a), the posterior anorectal angle (dotted white line) measures 100; the level of the anorectal junction (ARJ) is marked by the solid black line; and the site of the closed anal canal (AC) is represented by the white arrow. During expulsion (b), the anorectal angle opens to 178, the anorectal junction descends, and the anal canal opens

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. At rest (a), the posterior anorectal angle (dotted white line) measures 100; the level of the anorectal junction (ARJ) is marked by the solid black line; and the site of the closed anal canal (AC) is represented by the white arrow. During expulsion (b), the anorectal angle opens to 178, the anorectal junction descends, and the anal canal opens

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. Part 1 • This is facilitated by contraction of the pubococcygeus muscle that ‘‘splints’’ the perineal body, effectively tensing the anterior wall of the anal canal, allowing only the posterior wall to move backwards [284]. • Contraction of the conjoint longitudinal muscles of the anus also causes flattening of the anal vascular cushions [285] and shortening of the anal canal [141]. • The incoming fecal bolus possibly further flattens the vascular cushions by direct compression [285].

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. Part 1 • This is facilitated by contraction of the pubococcygeus muscle that ‘‘splints’’ the perineal body, effectively tensing the anterior wall of the anal canal, allowing only the posterior wall to move backwards [284]. • Contraction of the conjoint longitudinal muscles of the anus also causes flattening of the anal vascular cushions [285] and shortening of the anal canal [141]. • The incoming fecal bolus possibly further flattens the vascular cushions by direct compression [285].

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. Part 2 • All these changes, occurring simultaneously, decrease the anal canal pressure to a value lower than the intrarectal pressure resulting in a pressure gradient from the rectum to the outside. • Expulsion occurs and continues due to high intra -rectal pressure, augmented by straining. • It has been postulated that once defecation starts, sensory input from the anus maintains the propulsive activity until the rectum is empty [101, 286].

Normal evacuation proctogram images during defecation. Part 2 • All these changes, occurring simultaneously, decrease the anal canal pressure to a value lower than the intrarectal pressure resulting in a pressure gradient from the rectum to the outside. • Expulsion occurs and continues due to high intra -rectal pressure, augmented by straining. • It has been postulated that once defecation starts, sensory input from the anus maintains the propulsive activity until the rectum is empty [101, 286].

Termination of Defecation • This phase begins under semi-voluntary control • Thence by involuntary contraction of the external anal sphincter and pelvic floor, which closes the anal canal and reverses the pressure gradient towards the rectum.

Termination of Defecation • This phase begins under semi-voluntary control • Thence by involuntary contraction of the external anal sphincter and pelvic floor, which closes the anal canal and reverses the pressure gradient towards the rectum.

Termination of Defecation • When traction is applied to the anus and then released (likened in vivo to passage of stool), the external sphincter shows a momentary increase in activity that tends to close the canal. • This reflex is known as the ‘‘closing reflex’’ [141, 174, 287] and is important at the end of defecation to provide the internal sphincter, which is no longer inhibited by rectal distension, time to recover its tone [287]. • This reflex seems to be cortically modulated since it is impaired in patients with spinal injury [171].

Termination of Defecation • When traction is applied to the anus and then released (likened in vivo to passage of stool), the external sphincter shows a momentary increase in activity that tends to close the canal. • This reflex is known as the ‘‘closing reflex’’ [141, 174, 287] and is important at the end of defecation to provide the internal sphincter, which is no longer inhibited by rectal distension, time to recover its tone [287]. • This reflex seems to be cortically modulated since it is impaired in patients with spinal injury [171].

Termination of Defecation • Once straining ceases and intra-abdominal pressure falls, the postural reflex in the pelvic floor is reactivated [171], resulting in contraction of the puborectalis which increases its traction on the anorectal junction, returning the angle to its basal state. • Simultaneous relaxation of the conjoint longitudinal muscle elongates the anal canal and allows the anal cushions to passively distend, resulting in full closure of the anal canal.

Termination of Defecation • Once straining ceases and intra-abdominal pressure falls, the postural reflex in the pelvic floor is reactivated [171], resulting in contraction of the puborectalis which increases its traction on the anorectal junction, returning the angle to its basal state. • Simultaneous relaxation of the conjoint longitudinal muscle elongates the anal canal and allows the anal cushions to passively distend, resulting in full closure of the anal canal.

The End!

The End!