a3c75e19e9ba88e8801378f83b087737.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 92

The phasing of heterozygous traits: Algorithms and Complexity Giuseppe Lancia University of Udine

The phasing of heterozygous traits: Algorithms and Complexity Giuseppe Lancia University of Udine

-The genomic age has allowed to look at ourselves in a detailed, comparative way -All humans are >99% identical at genome level -Small changes in a genome can make a big difference in how we look and who we are

-The genomic age has allowed to look at ourselves in a detailed, comparative way -All humans are >99% identical at genome level -Small changes in a genome can make a big difference in how we look and who we are

What makes us different from each other? The answer is ISMS POLYMORPH

What makes us different from each other? The answer is ISMS POLYMORPH

This is true for humans as well as for other species

This is true for humans as well as for other species

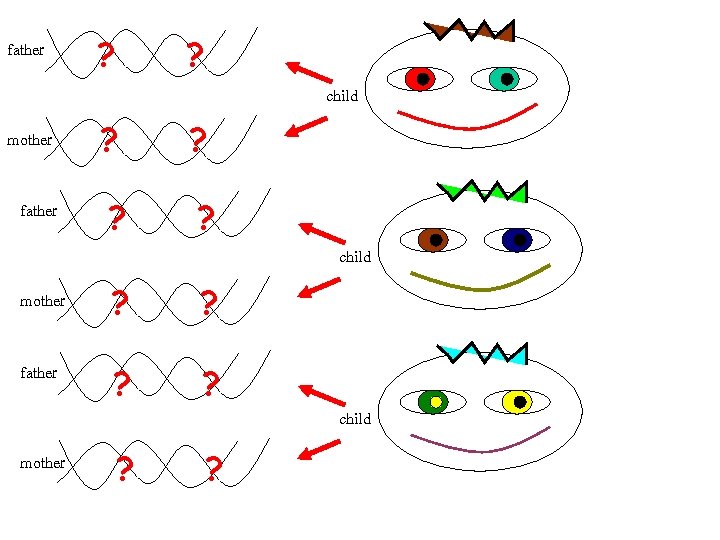

Polymorphisms are features existing in different “flavours”, that make us all look (and be) different Examples can be eye-color, blood type, hair, etc… In fact, polymorphisms in the way we look (phenotyes) are determined by polymorphisms in our genome

Polymorphisms are features existing in different “flavours”, that make us all look (and be) different Examples can be eye-color, blood type, hair, etc… In fact, polymorphisms in the way we look (phenotyes) are determined by polymorphisms in our genome

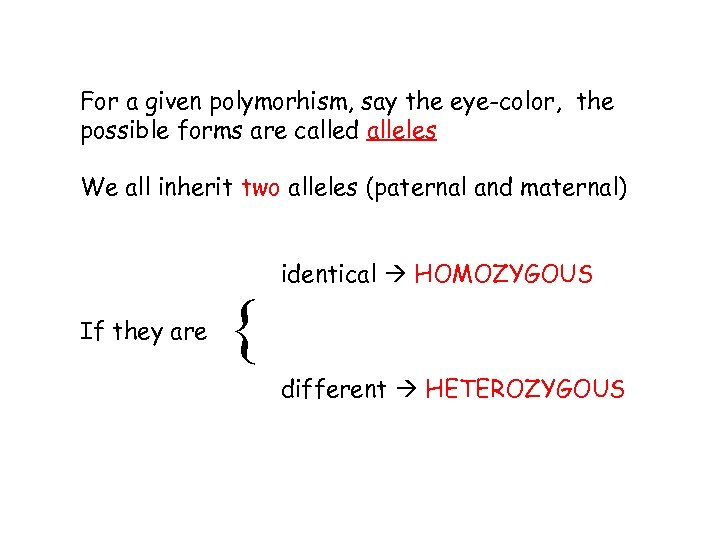

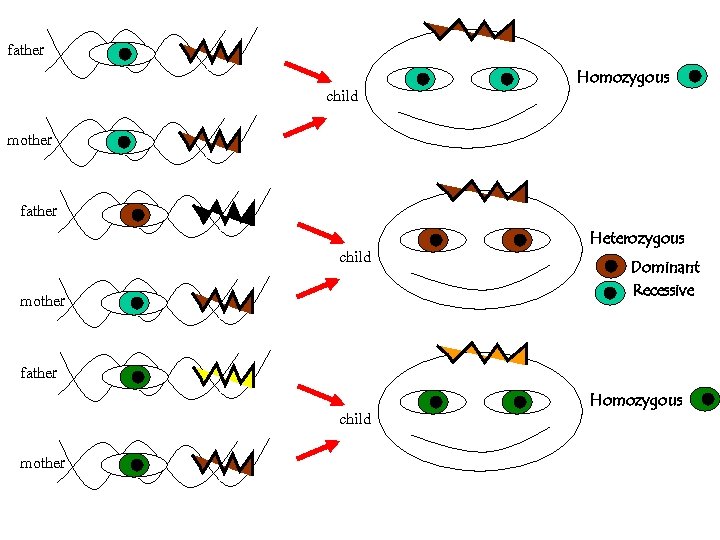

For a given polymorhism, say the eye-color, the possible forms are called alleles We all inherit two alleles (paternal and maternal) If they are { identical HOMOZYGOUS different HETEROZYGOUS

For a given polymorhism, say the eye-color, the possible forms are called alleles We all inherit two alleles (paternal and maternal) If they are { identical HOMOZYGOUS different HETEROZYGOUS

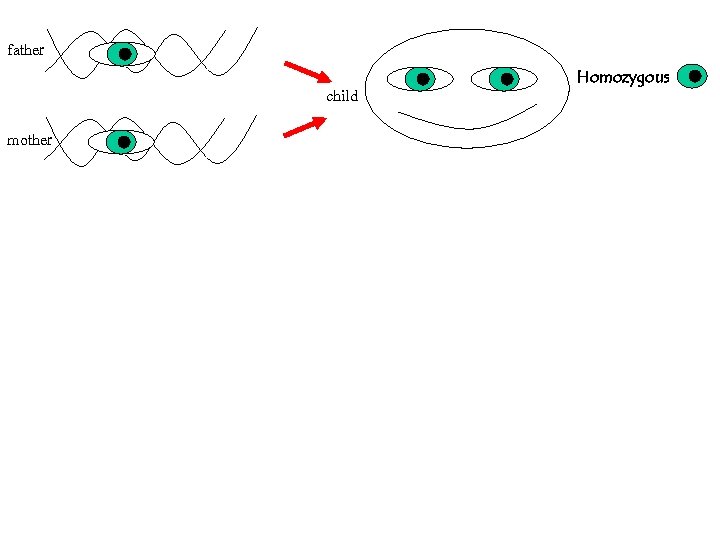

father child mother Homozygous

father child mother Homozygous

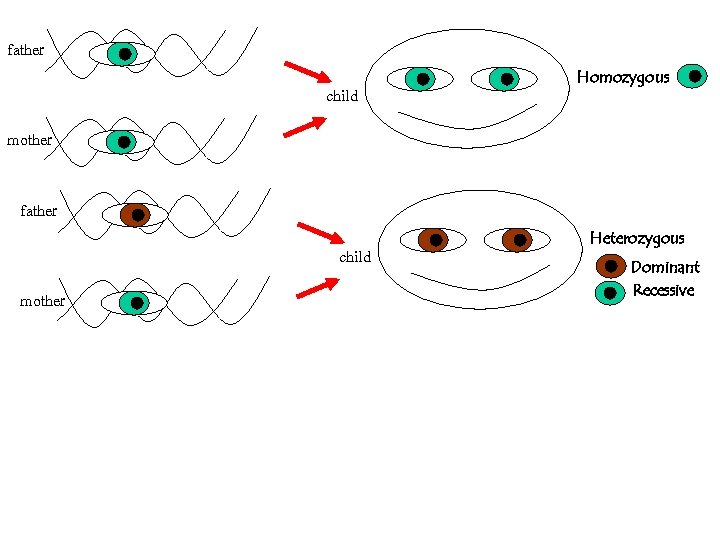

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive

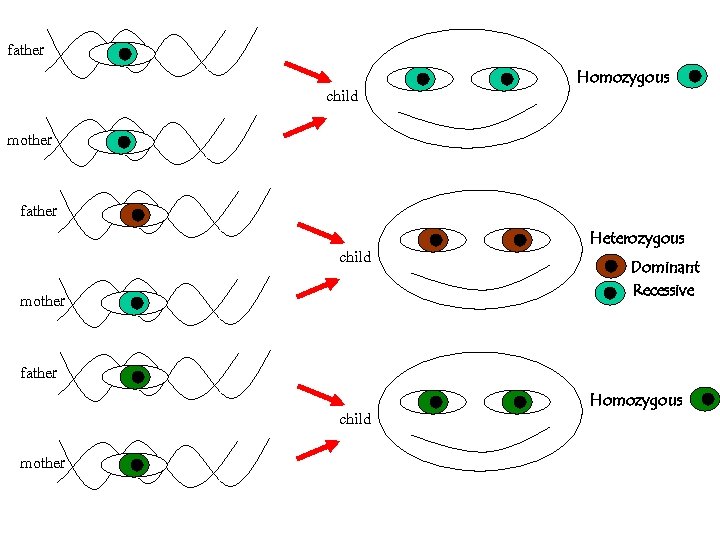

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive father child mother Homozygous

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive father child mother Homozygous

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive father child mother Homozygous

father child Homozygous mother father child mother Heterozygous Dominant Recessive father child mother Homozygous

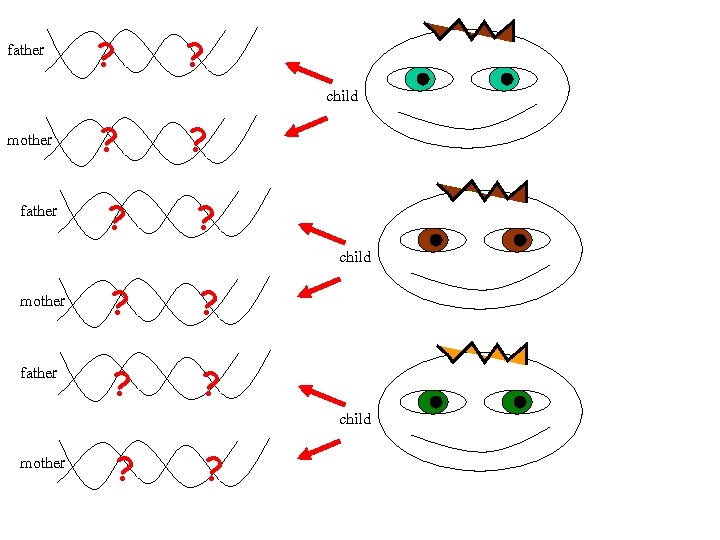

father ? ? child mother father ? ? child mother ? ?

father ? ? child mother father ? ? child mother ? ?

father ? ? child mother father ? ? child mother ? ?

father ? ? child mother father ? ? child mother ? ?

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

At DNA level, a polymorphism is a sequence of nucleotides varying in a population. The shortest possible sequence has only 1 nucleotide, hence Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)

At DNA level, a polymorphism is a sequence of nucleotides varying in a population. The shortest possible sequence has only 1 nucleotide, hence Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP)

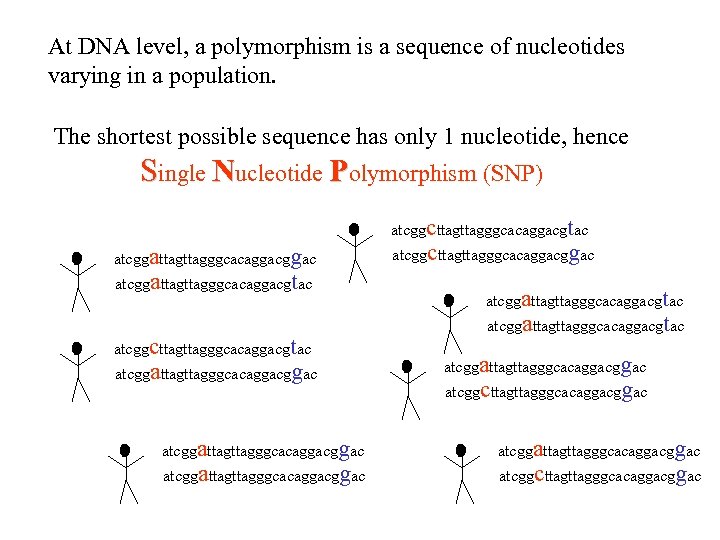

At DNA level, a polymorphism is a sequence of nucleotides varying in a population. The shortest possible sequence has only 1 nucleotide, hence Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

At DNA level, a polymorphism is a sequence of nucleotides varying in a population. The shortest possible sequence has only 1 nucleotide, hence Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

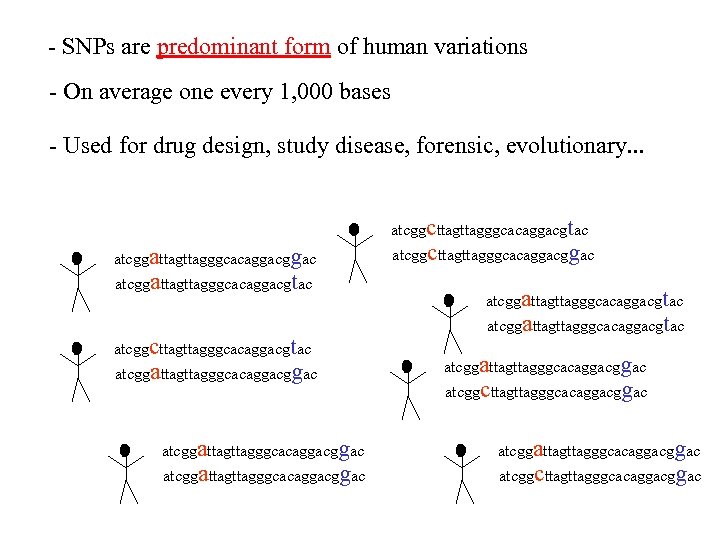

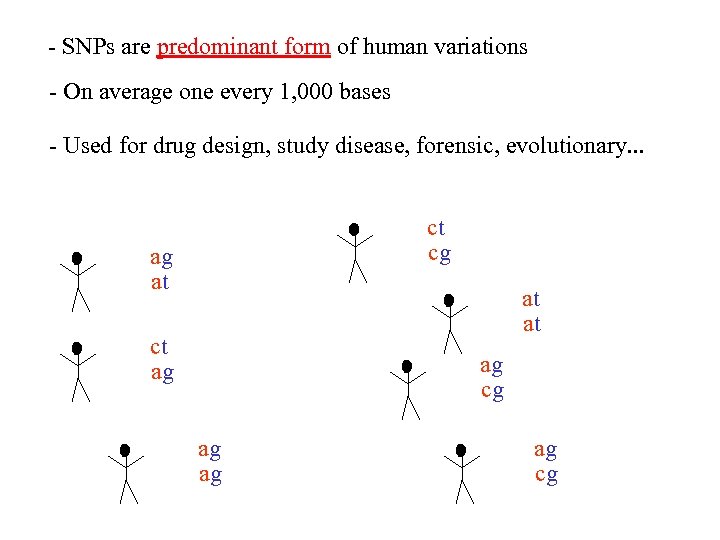

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgt atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggcttagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggattagggcacaggac atcggcttagggcacaggac atcggattagggcacaggacgtac atcggattagggcacaggacgt atcggattagttagggcacaggacggac atcggcttagttagggcacaggacggac

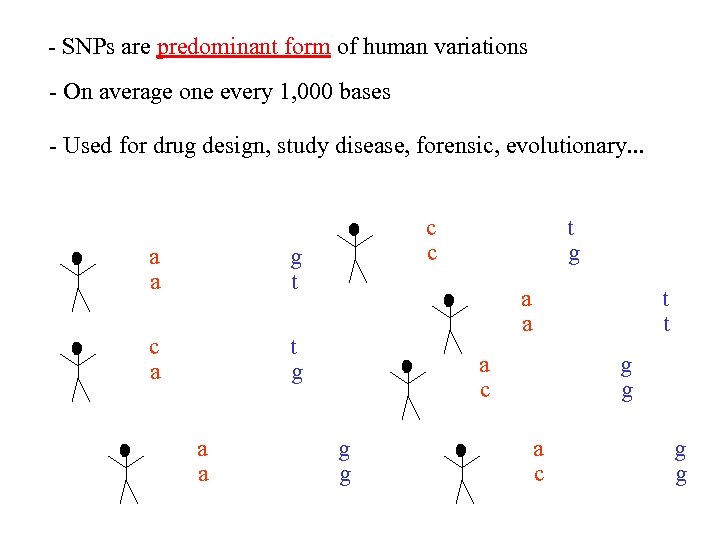

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . ct cg ag at at at ct ag ag cg ag ag ag cg

- SNPs are predominant form of human variations - On average one every 1, 000 bases - Used for drug design, study disease, forensic, evolutionary. . . ct cg ag at at at ct ag ag cg ag ag ag cg

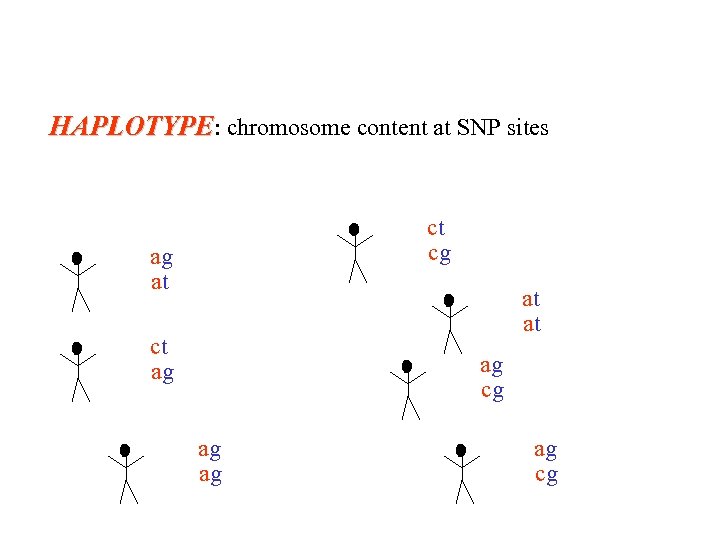

HAPLOTYPE: chromosome content at SNP sites ct cg ag at at at ct ag ag cg ag ag ag cg

HAPLOTYPE: chromosome content at SNP sites ct cg ag at at at ct ag ag cg ag ag ag cg

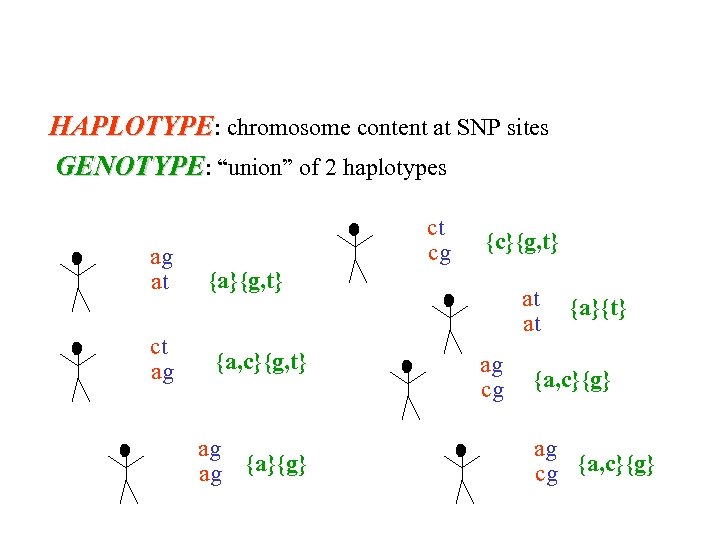

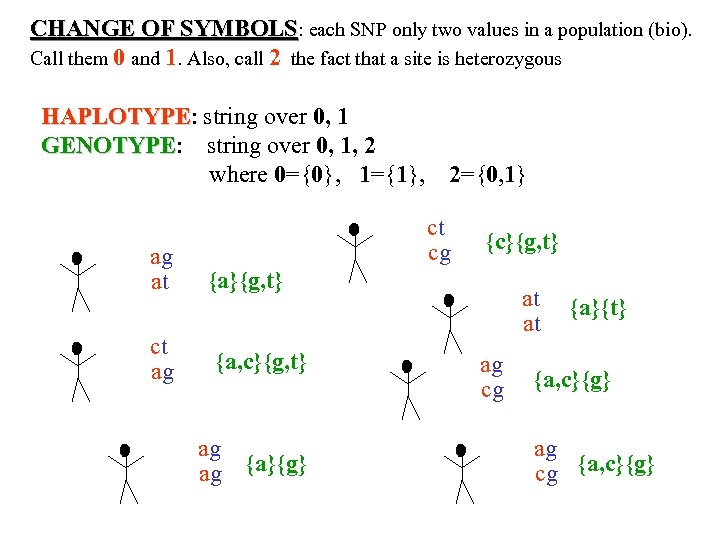

HAPLOTYPE: chromosome content at SNP sites GENOTYPE: “union” of 2 haplotypes ag at ct ag ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

HAPLOTYPE: chromosome content at SNP sites GENOTYPE: “union” of 2 haplotypes ag at ct ag ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

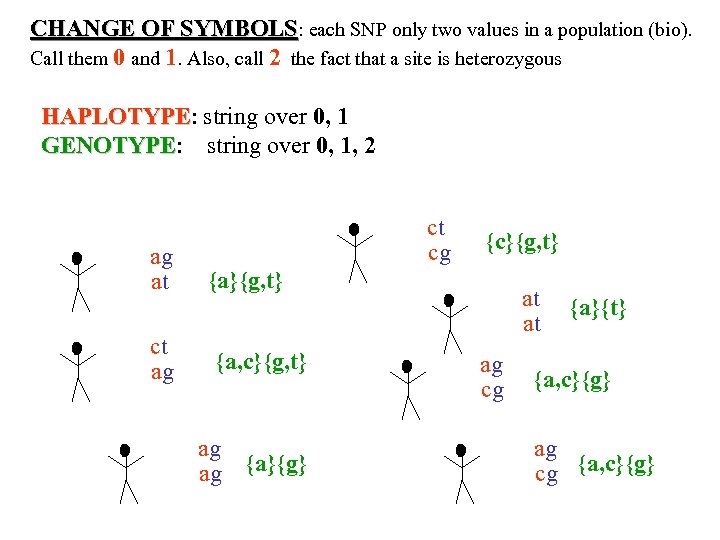

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE ag at ct ag ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE ag at ct ag ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE where 0={0}, 1={1}, ag at ct ag 2={0, 1} ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE where 0={0}, 1={1}, ag at ct ag 2={0, 1} ct cg {c}{g, t} {a, c}{g, t} ag ag {a}{g} at at ag cg {a}{t} {a, c}{g} ag cg {a, c}{g}

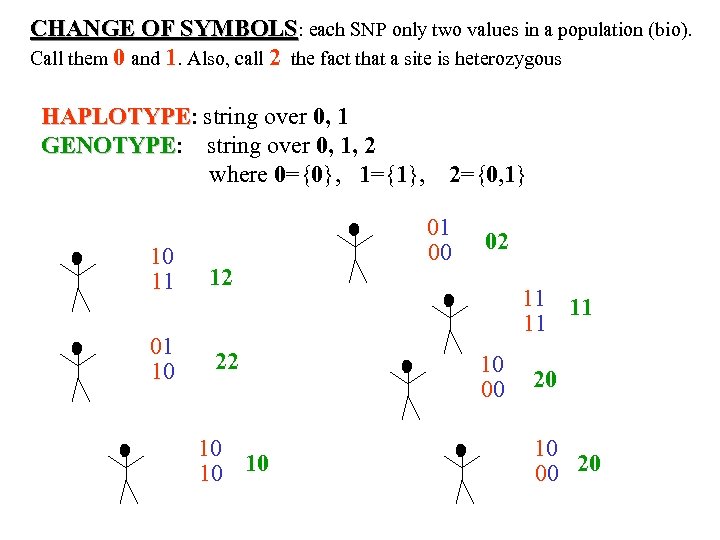

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE where 0={0}, 1={1}, 10 11 12 01 10 22 10 10 10 2={0, 1} 01 00 02 11 11 11 10 00 20

CHANGE OF SYMBOLS: each SNP only two values in a population (bio). Call them 0 and 1. Also, call 2 the fact that a site is heterozygous HAPLOTYPE: string over 0, 1 HAPLOTYPE GENOTYPE: string over 0, 1, 2 GENOTYPE where 0={0}, 1={1}, 10 11 12 01 10 22 10 10 10 2={0, 1} 01 00 02 11 11 11 10 00 20

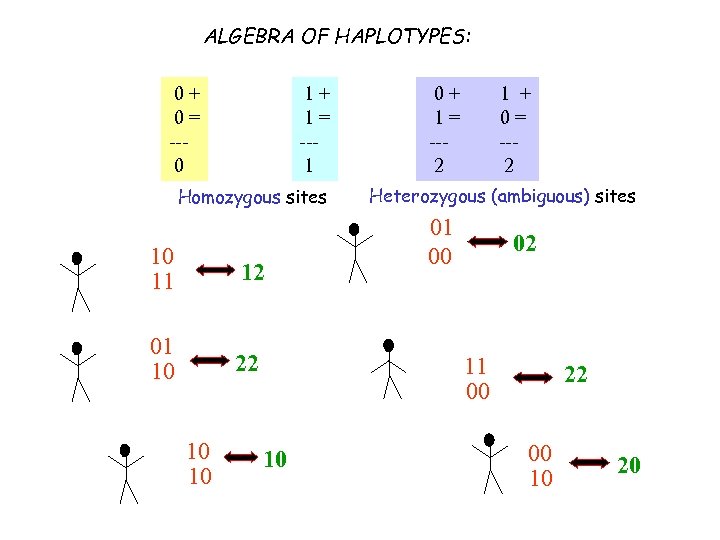

ALGEBRA OF HAPLOTYPES: 0+ 0= --0 1+ 1= --1 Homozygous sites 10 11 12 01 10 22 10 10 0+ 1= --2 1 + 0= --2 Heterozygous (ambiguous) sites 01 00 02 11 00 10 22 00 10 20

ALGEBRA OF HAPLOTYPES: 0+ 0= --0 1+ 1= --1 Homozygous sites 10 11 12 01 10 22 10 10 0+ 1= --2 1 + 0= --2 Heterozygous (ambiguous) sites 01 00 02 11 00 10 22 00 10 20

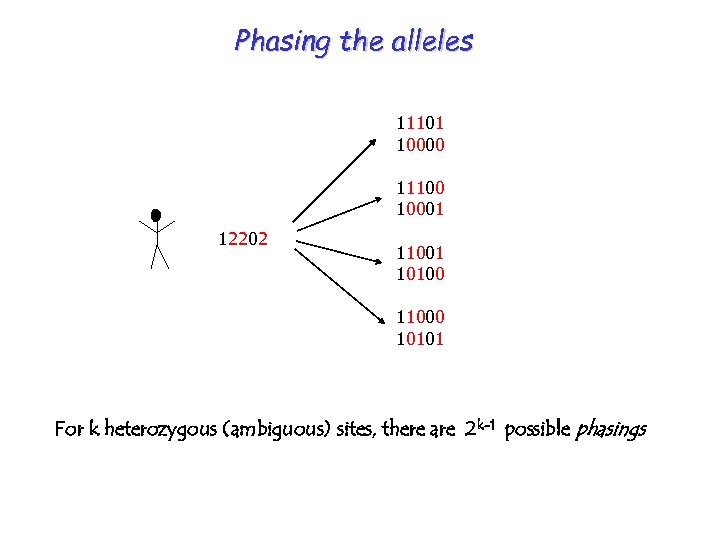

Phasing the alleles 11101 10000 11100 10001 12202 11001 10100 11000 10101 For k heterozygous (ambiguous) sites, there are 2 k-1 possible phasings

Phasing the alleles 11101 10000 11100 10001 12202 11001 10100 11000 10101 For k heterozygous (ambiguous) sites, there are 2 k-1 possible phasings

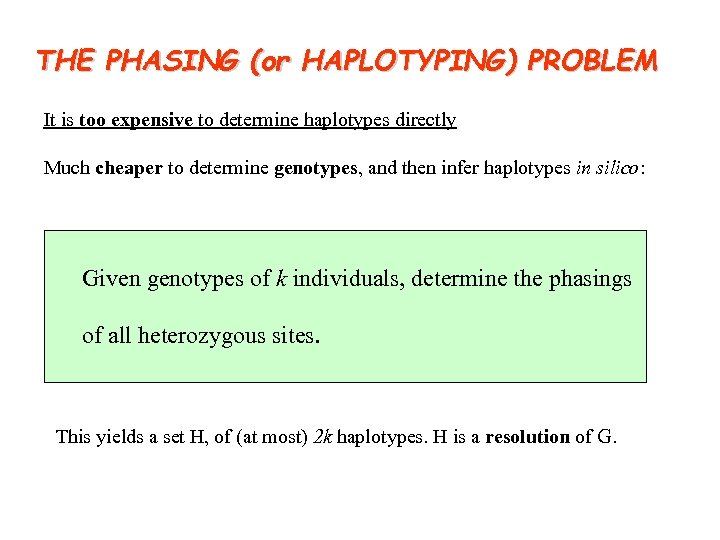

THE PHASING (or HAPLOTYPING) PROBLEM It is too expensive to determine haplotypes directly Much cheaper to determine genotypes, and then infer haplotypes in silico: Given genotypes of k individuals, determine the phasings of all heterozygous sites. This yields a set H, of (at most) 2 k haplotypes. H is a resolution of G.

THE PHASING (or HAPLOTYPING) PROBLEM It is too expensive to determine haplotypes directly Much cheaper to determine genotypes, and then infer haplotypes in silico: Given genotypes of k individuals, determine the phasings of all heterozygous sites. This yields a set H, of (at most) 2 k haplotypes. H is a resolution of G.

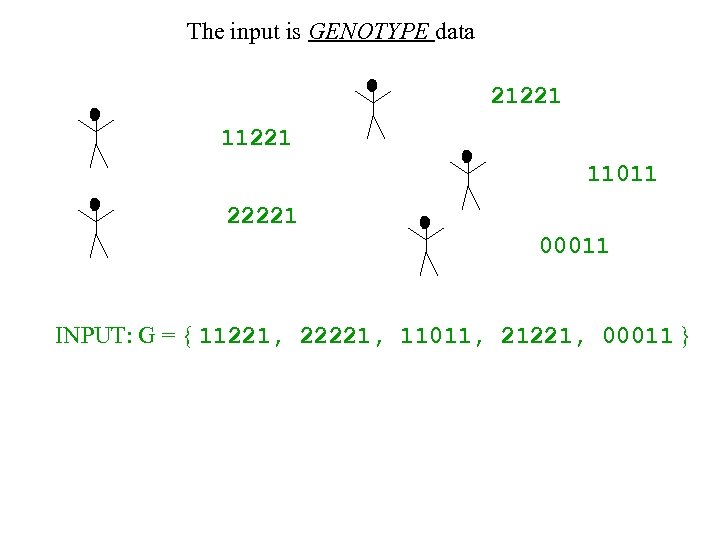

The input is GENOTYPE data 21221 11011 22221 00011 INPUT: G = { 11221, 22221, 11011, 21221, 00011 }

The input is GENOTYPE data 21221 11011 22221 00011 INPUT: G = { 11221, 22221, 11011, 21221, 00011 }

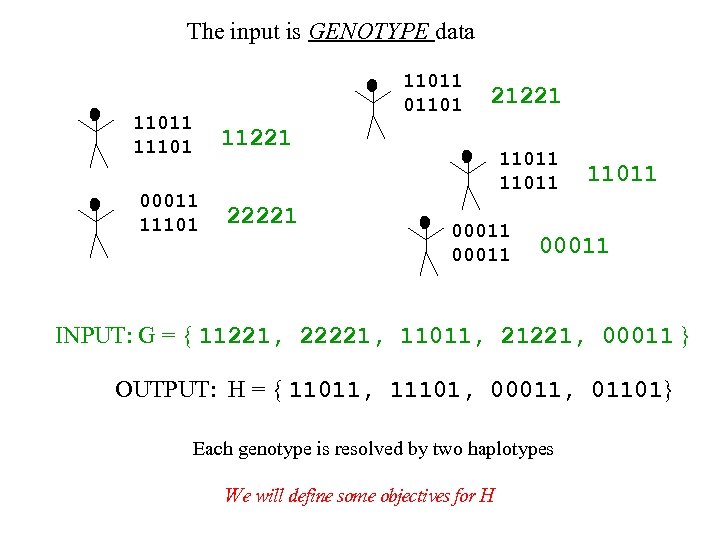

The input is GENOTYPE data 11011 011011 11101 21221 11221 00011 11101 22221 11011 00011 INPUT: G = { 11221, 22221, 11011, 21221, 00011 } OUTPUT: H = { 11011, 11101, 00011, 01101} Each genotype is resolved by two haplotypes We will define some objectives for H

The input is GENOTYPE data 11011 011011 11101 21221 11221 00011 11101 22221 11011 00011 INPUT: G = { 11221, 22221, 11011, 21221, 00011 } OUTPUT: H = { 11011, 11101, 00011, 01101} Each genotype is resolved by two haplotypes We will define some objectives for H

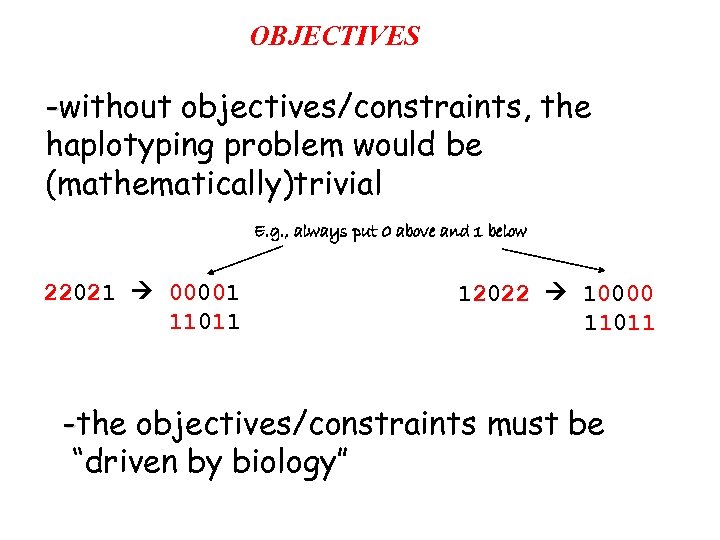

OBJECTIVES -without objectives/constraints, the haplotyping problem would be (mathematically)trivial E. g. , always put 0 above and 1 below 22021 00001 11011 12022 10000 11011 -the objectives/constraints must be “driven by biology”

OBJECTIVES -without objectives/constraints, the haplotyping problem would be (mathematically)trivial E. g. , always put 0 above and 1 below 22021 00001 11011 12022 10000 11011 -the objectives/constraints must be “driven by biology”

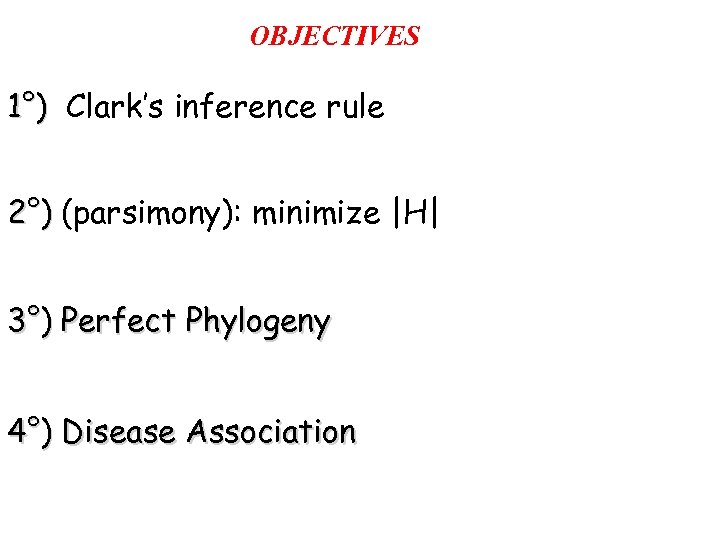

OBJECTIVES 1°) Clark’s inference rule 2°) (parsimony): minimize |H| 3°) Perfect Phylogeny 4°) Disease Association

OBJECTIVES 1°) Clark’s inference rule 2°) (parsimony): minimize |H| 3°) Perfect Phylogeny 4°) Disease Association

1 st Obj: Clark’s rule

1 st Obj: Clark’s rule

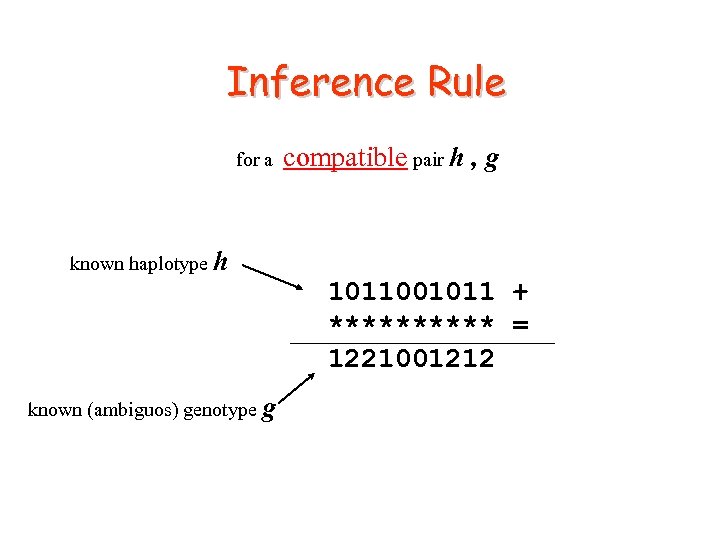

Inference Rule for a compatible pair h , g known haplotype h 1011001011 + ***** = 1221001212 known (ambiguos) genotype g

Inference Rule for a compatible pair h , g known haplotype h 1011001011 + ***** = 1221001212 known (ambiguos) genotype g

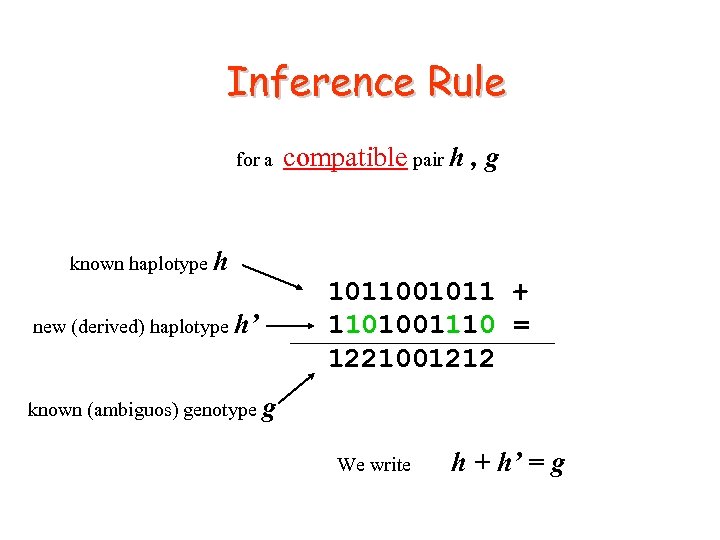

Inference Rule for a compatible pair h , g known haplotype h new (derived) haplotype h’ 1011001011 + 1101001110 = 1221001212 known (ambiguos) genotype g We write h + h’ = g

Inference Rule for a compatible pair h , g known haplotype h new (derived) haplotype h’ 1011001011 + 1101001110 = 1221001212 known (ambiguos) genotype g We write h + h’ = g

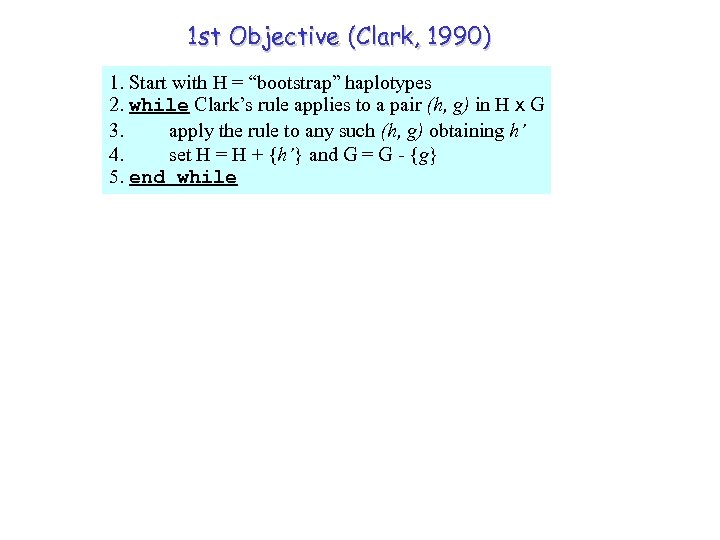

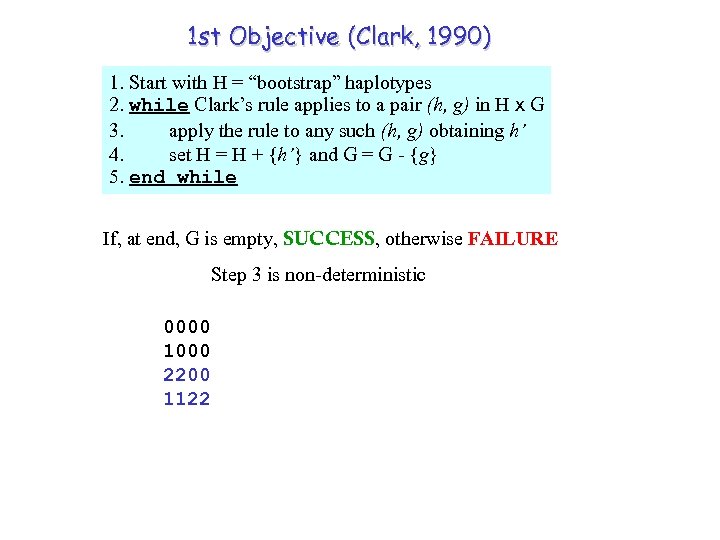

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic

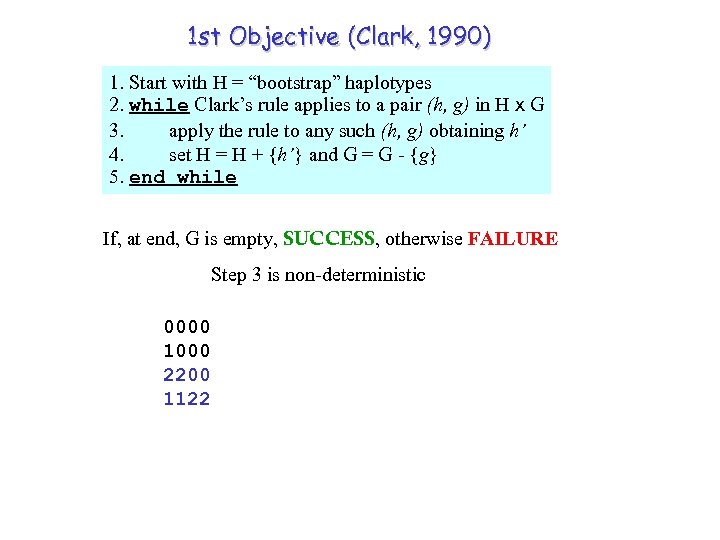

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122

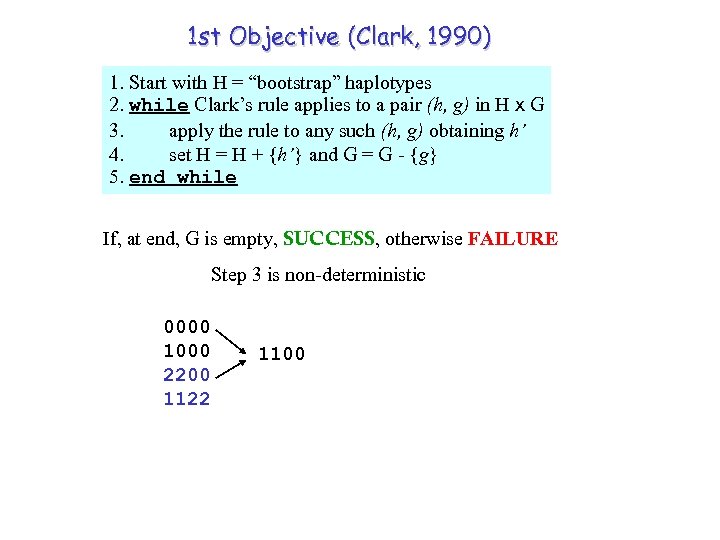

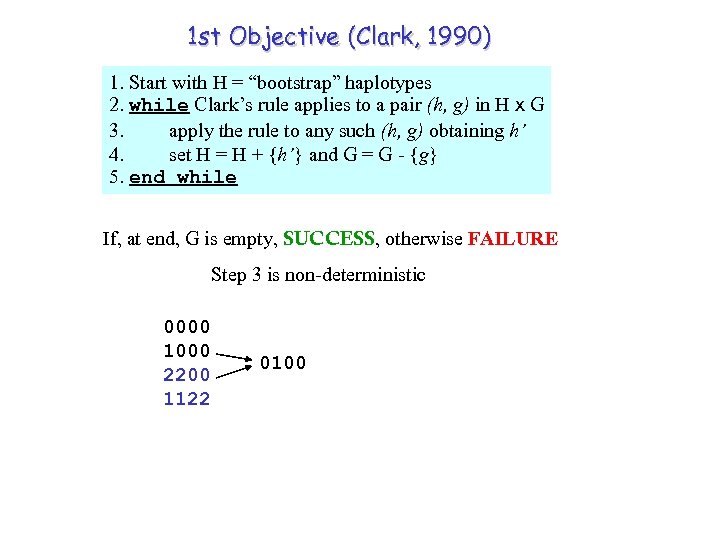

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 1100

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 1100

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 1100 1111 SUCCESS

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 1100 1111 SUCCESS

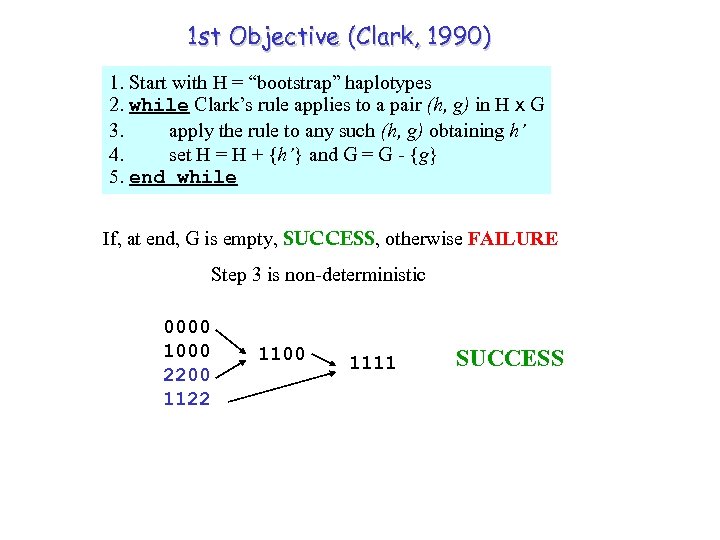

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122

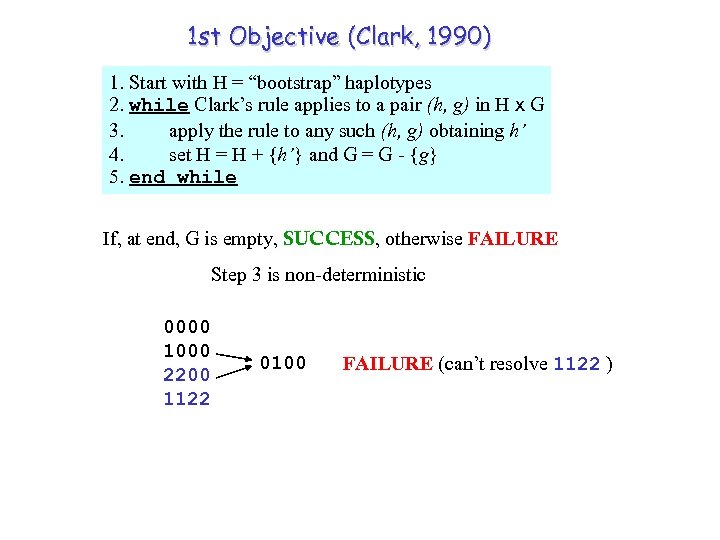

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 0100

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 0100

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 0100 FAILURE (can’t resolve 1122 )

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic 0000 1000 2200 1122 0100 FAILURE (can’t resolve 1122 )

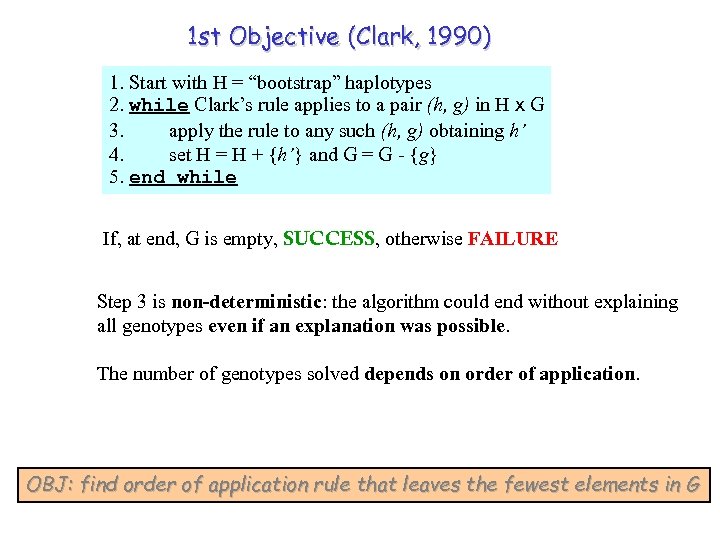

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic: the algorithm could end without explaining all genotypes even if an explanation was possible. The number of genotypes solved depends on order of application. OBJ: find order of application rule that leaves the fewest elements in G

1 st Objective (Clark, 1990) 1. Start with H = “bootstrap” haplotypes 2. while Clark’s rule applies to a pair (h, g) in H x G 3. apply the rule to any such (h, g) obtaining h’ 4. set H = H + {h’} and G = G - {g} 5. end while If, at end, G is empty, SUCCESS, otherwise FAILURE Step 3 is non-deterministic: the algorithm could end without explaining all genotypes even if an explanation was possible. The number of genotypes solved depends on order of application. OBJ: find order of application rule that leaves the fewest elements in G

The problem was studied by Gusfield (ISMB 2000, and Journal of Comp. Biol. , 2001) - problem is APX-hard - it corresponds to finding largest forest in a graph with haplotypes as nodes and arcs for possible derivations -solved via ILP of exponential-size (practical for small real instances)

The problem was studied by Gusfield (ISMB 2000, and Journal of Comp. Biol. , 2001) - problem is APX-hard - it corresponds to finding largest forest in a graph with haplotypes as nodes and arcs for possible derivations -solved via ILP of exponential-size (practical for small real instances)

2 nd Obj: Max Parsimony

2 nd Obj: Max Parsimony

- Clark conjectured solution (when found) uses min # of haplotypes - this is clearly false - solution with few haplotypes is biologically relevant (as we all descend from a small set of ancestors)

- Clark conjectured solution (when found) uses min # of haplotypes - this is clearly false - solution with few haplotypes is biologically relevant (as we all descend from a small set of ancestors)

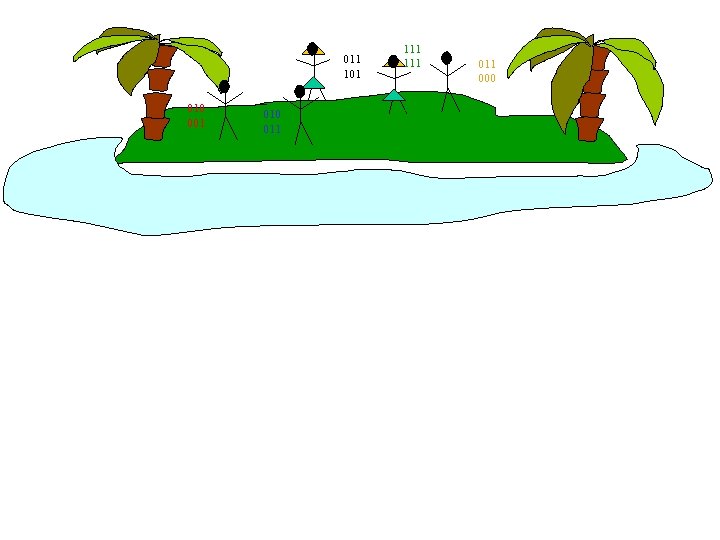

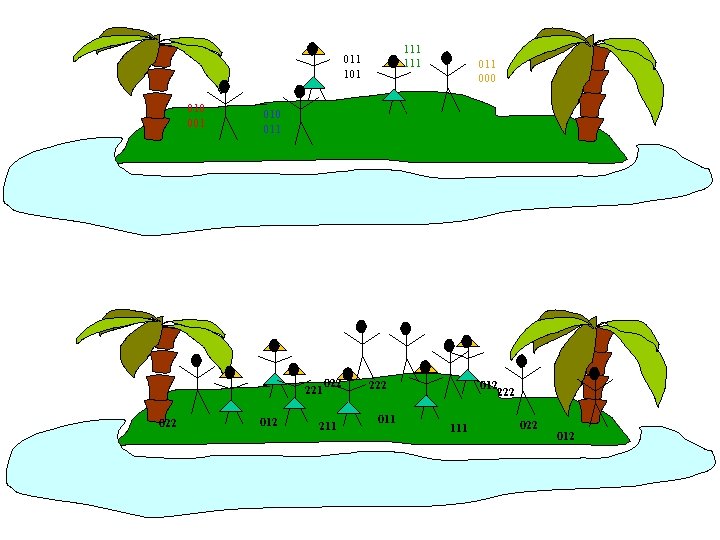

011 101 010 011 111 111 000

011 101 010 011 111 111 000

111 011 101 010 001 111 010 011 221 022 011 000 022 211 222 011 012 222 111 022 012

111 011 101 010 001 111 010 011 221 022 011 000 022 211 222 011 012 222 111 022 012

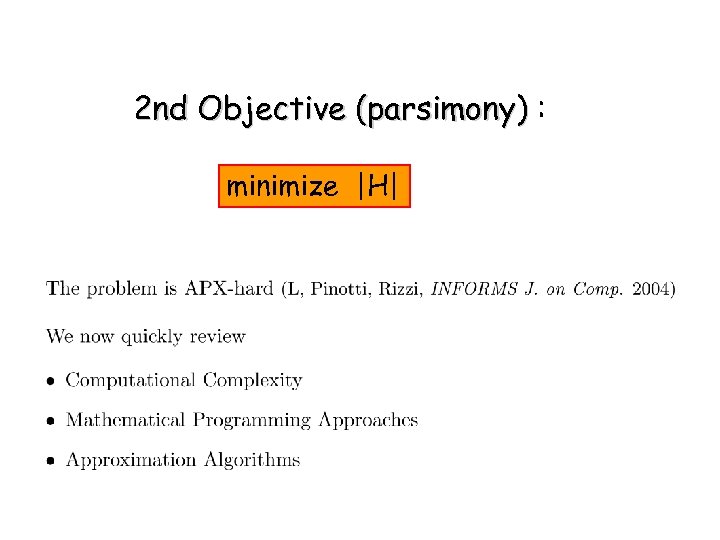

2 nd Objective (parsimony) : minimize |H|

2 nd Objective (parsimony) : minimize |H|

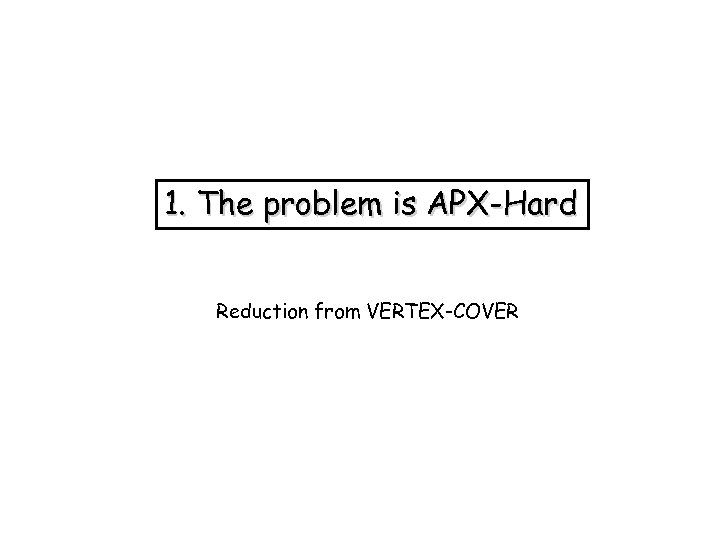

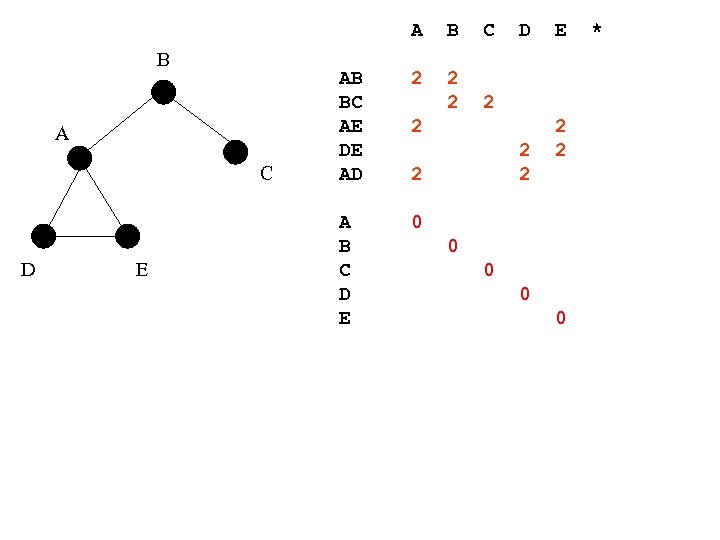

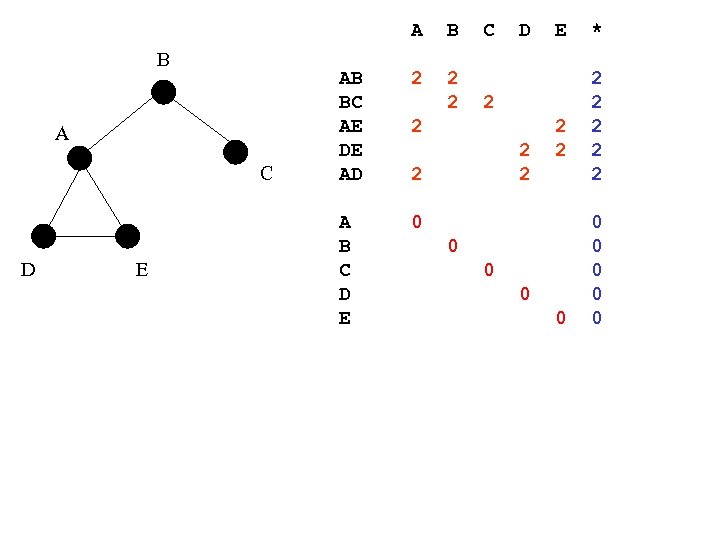

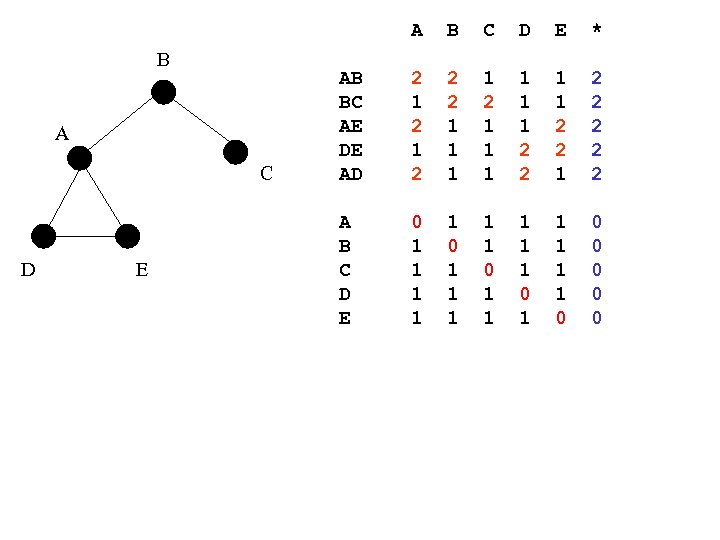

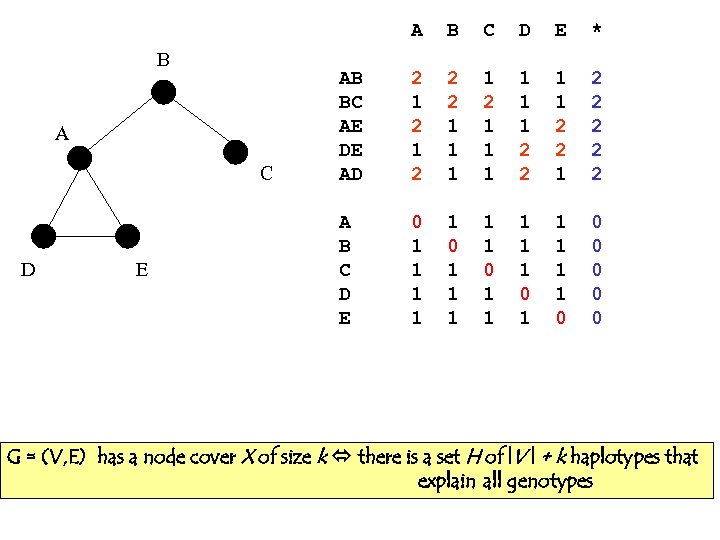

1. The problem is APX-Hard Reduction from VERTEX-COVER

1. The problem is APX-Hard Reduction from VERTEX-COVER

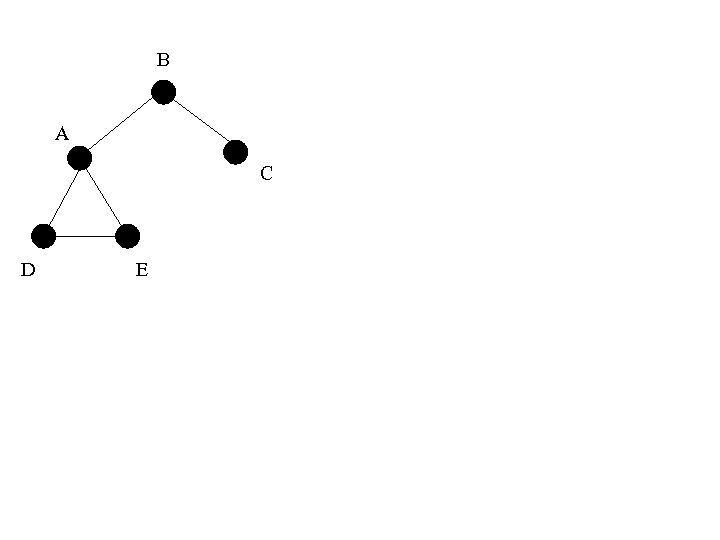

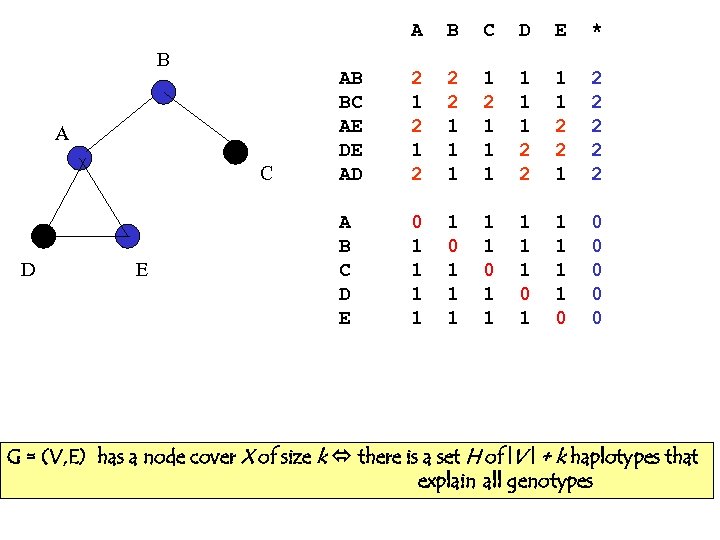

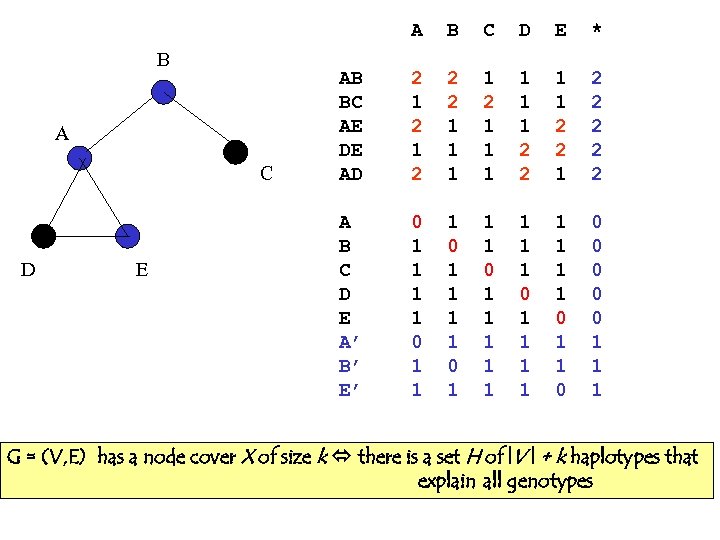

B A C D E

B A C D E

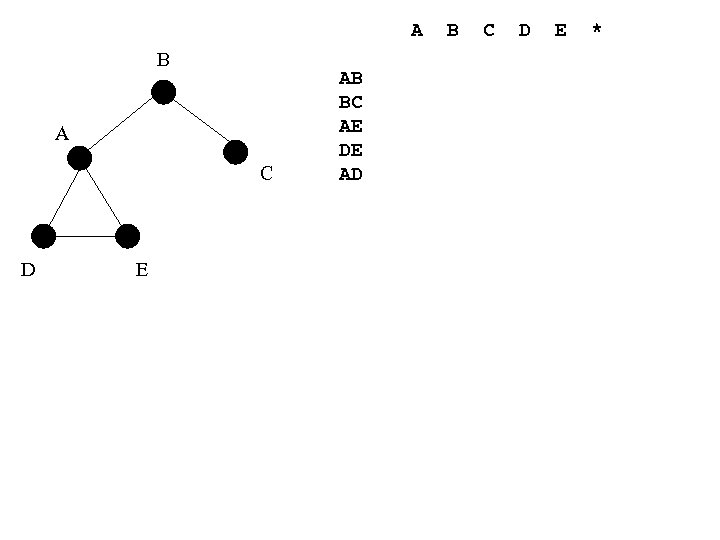

A B A C D E B C D E *

A B A C D E B C D E *

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD B C D E *

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD B C D E *

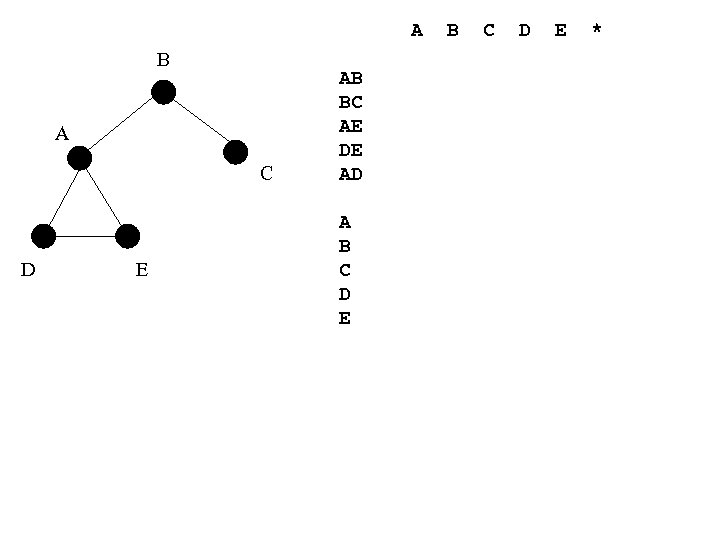

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD A B C D E *

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD A B C D E *

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD A B C D E B C 2 2 2 D 2 2 2 E 2 2 *

A B A C D E AB BC AE DE AD A B C D E B C 2 2 2 D 2 2 2 E 2 2 *

A B A C D E B C AB BC AE DE AD 2 2 A B C D E D 0 2 2 E 2 2 0 0 *

A B A C D E B C AB BC AE DE AD 2 2 A B C D E D 0 2 2 E 2 2 0 0 *

A B A C D E B AB BC AE DE AD 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 2 2 2 2 0 0 * 2 2 2 0 0 0

A B A C D E B AB BC AE DE AD 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 2 2 2 2 0 0 * 2 2 2 0 0 0

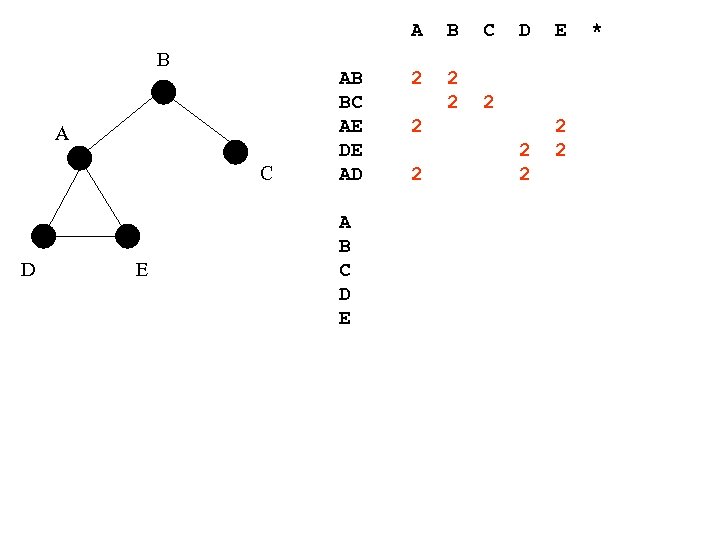

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E A’ B’ E’ 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

A B A C D E B C D E * AB BC AE DE AD 2 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 2 A B C D E A’ B’ E’ 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 G = (V, E) has a node cover X of size k there is a set H of |V | + k haplotypes that explain all genotypes

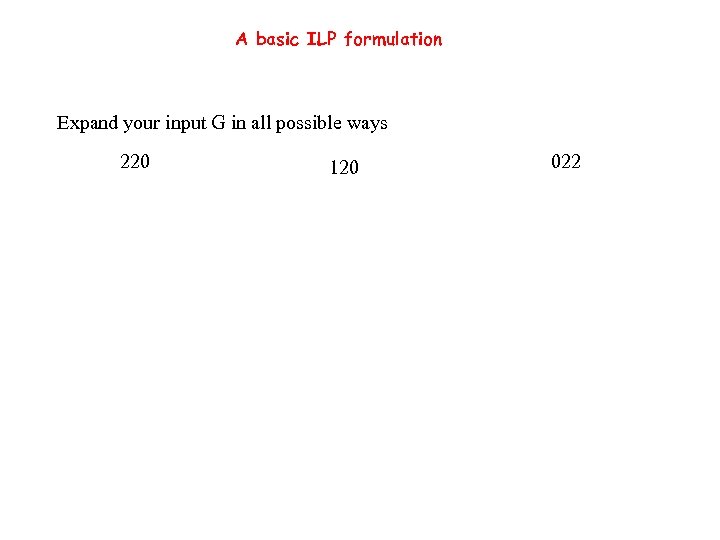

A basic ILP formulation

A basic ILP formulation

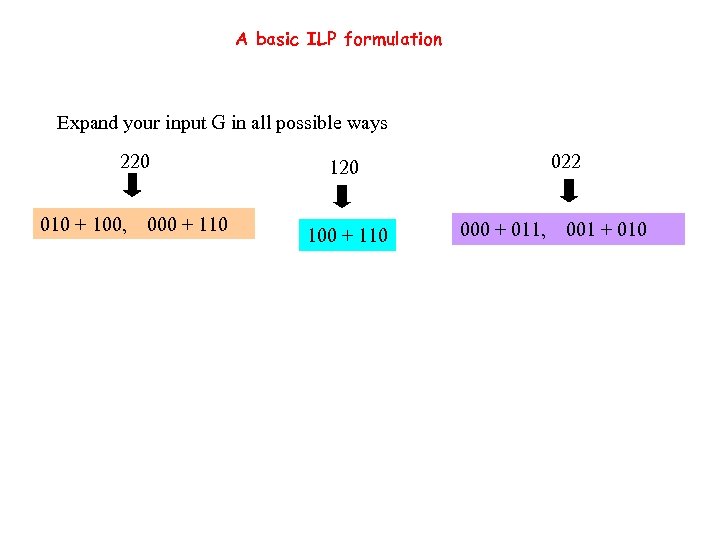

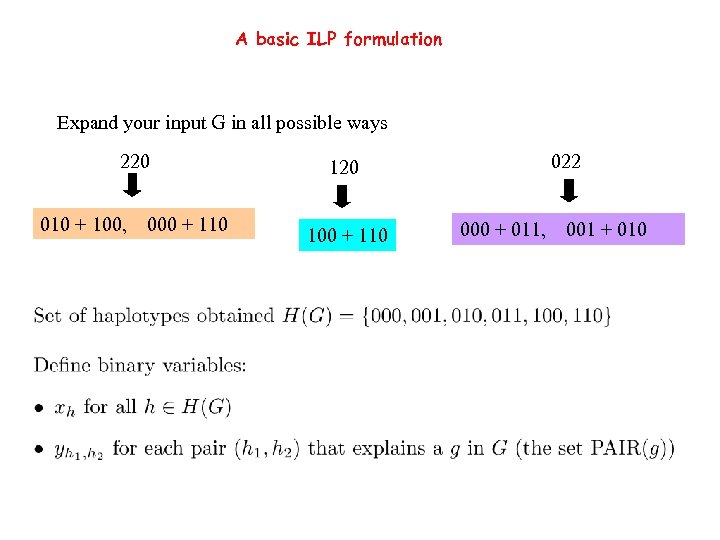

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 120 022

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 120 022

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 010 + 100, 000 + 110 022 120 100 + 110 000 + 011, 001 + 010

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 010 + 100, 000 + 110 022 120 100 + 110 000 + 011, 001 + 010

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 010 + 100, 000 + 110 022 120 100 + 110 000 + 011, 001 + 010

A basic ILP formulation Expand your input G in all possible ways 220 010 + 100, 000 + 110 022 120 100 + 110 000 + 011, 001 + 010

The resulting Integer Program (IP 1):

The resulting Integer Program (IP 1):

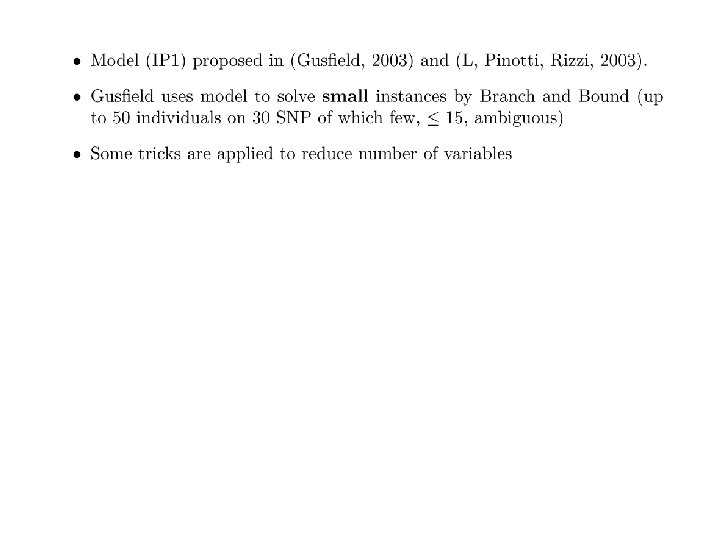

Other ILP formulation are possible. E. g. POLY-SIZE ILP formulations

Other ILP formulation are possible. E. g. POLY-SIZE ILP formulations

3 rd Obj: Perfect Phylogeny

3 rd Obj: Perfect Phylogeny

- Parsimony does not take into account mutations/evolution of haplotypes - parsimony is very relialable on “small” haplotype blocks - when haplotypes are large (span several SNPs, we should consider evolutionionary events and recombination) - the cleanest model for evolution is the perfect phylogeny

- Parsimony does not take into account mutations/evolution of haplotypes - parsimony is very relialable on “small” haplotype blocks - when haplotypes are large (span several SNPs, we should consider evolutionionary events and recombination) - the cleanest model for evolution is the perfect phylogeny

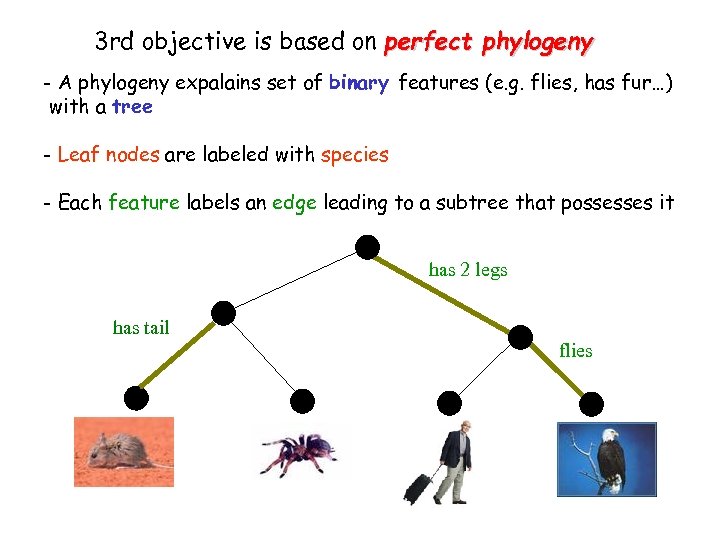

3 rd objective is based on perfect phylogeny - A phylogeny expalains set of binary features (e. g. flies, has fur…) with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it

3 rd objective is based on perfect phylogeny - A phylogeny expalains set of binary features (e. g. flies, has fur…) with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it

3 rd objective is based on perfect phylogeny - A phylogeny expalains set of binary features (e. g. flies, has fur…) with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it has 2 legs has tail flies

3 rd objective is based on perfect phylogeny - A phylogeny expalains set of binary features (e. g. flies, has fur…) with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it has 2 legs has tail flies

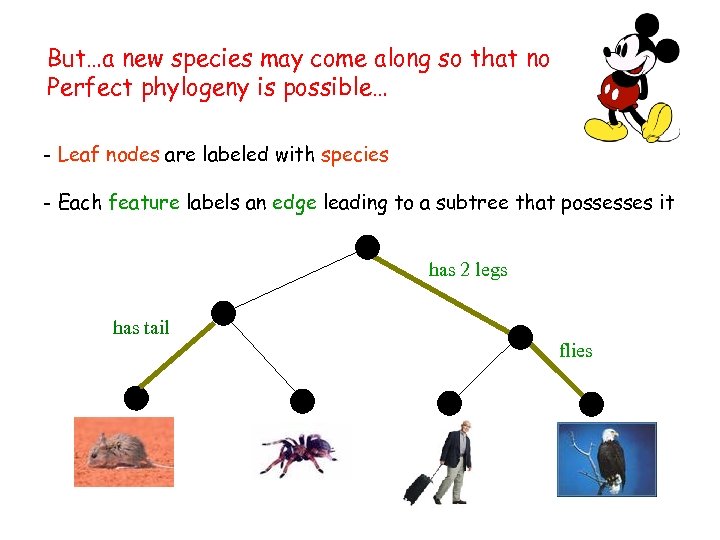

But…a new species may come along so that no - A phylogeny expalainsis possible… features (e. g. flies, has fur…) Perfect phylogeny set of binary with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it has 2 legs has tail flies

But…a new species may come along so that no - A phylogeny expalainsis possible… features (e. g. flies, has fur…) Perfect phylogeny set of binary with a tree - Leaf nodes are labeled with species - Each feature labels an edge leading to a subtree that possesses it has 2 legs has tail flies

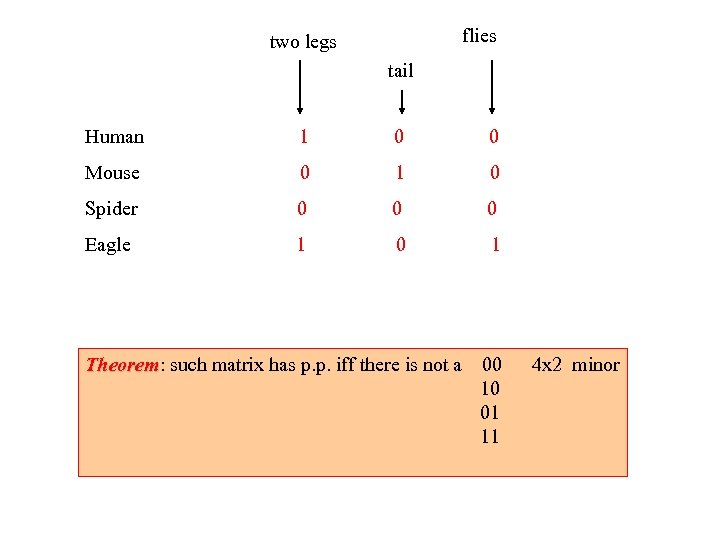

flies two legs tail Human 1 0 0 Mouse 0 1 0 Spider 0 0 0 Eagle 1 0 1 Theorem: such matrix has p. p. iff there is not a Theorem 00 10 01 11 4 x 2 minor

flies two legs tail Human 1 0 0 Mouse 0 1 0 Spider 0 0 0 Eagle 1 0 1 Theorem: such matrix has p. p. iff there is not a Theorem 00 10 01 11 4 x 2 minor

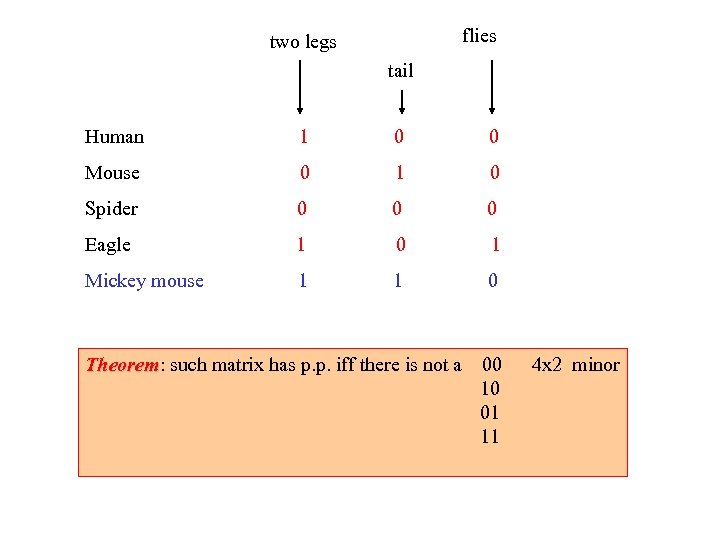

flies two legs tail Human 1 0 0 Mouse 0 1 0 Spider 0 0 0 Eagle 1 0 1 Mickey mouse 1 1 0 Theorem: such matrix has p. p. iff there is not a Theorem 00 10 01 11 4 x 2 minor

flies two legs tail Human 1 0 0 Mouse 0 1 0 Spider 0 0 0 Eagle 1 0 1 Mickey mouse 1 1 0 Theorem: such matrix has p. p. iff there is not a Theorem 00 10 01 11 4 x 2 minor

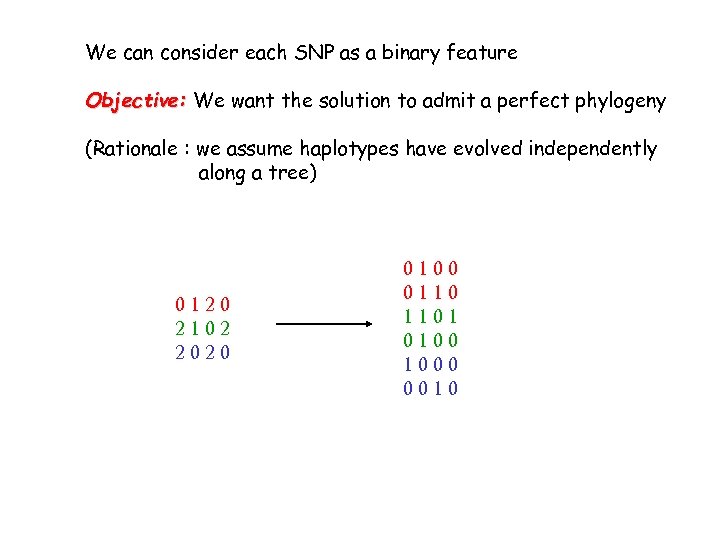

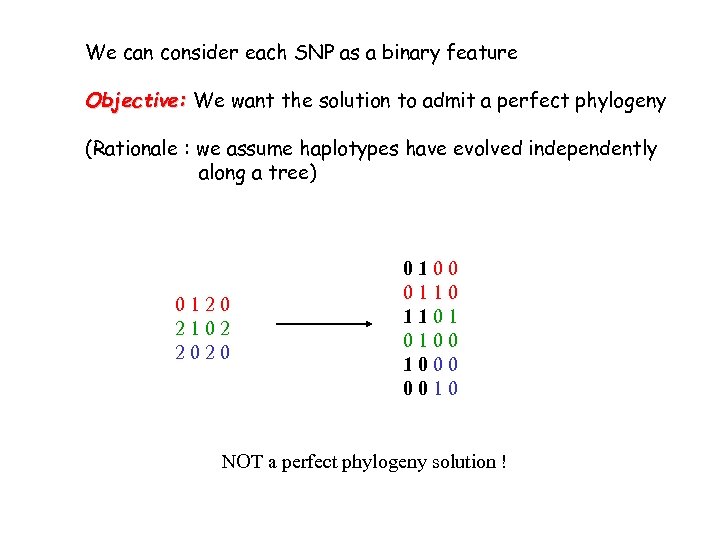

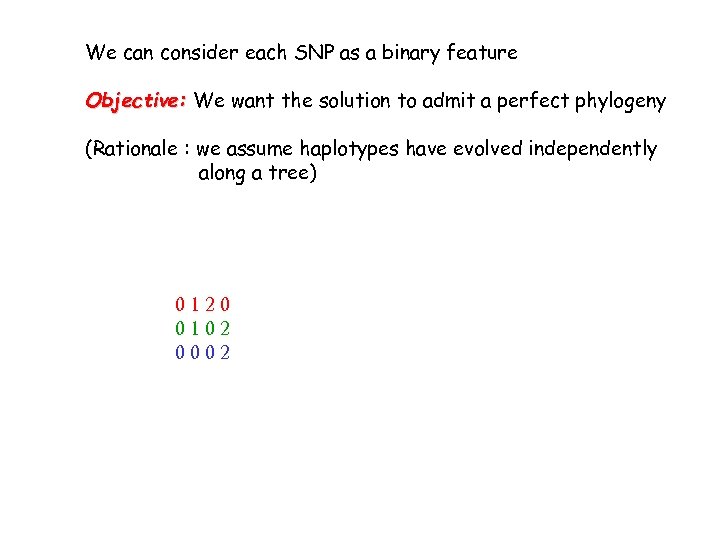

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree)

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree)

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020

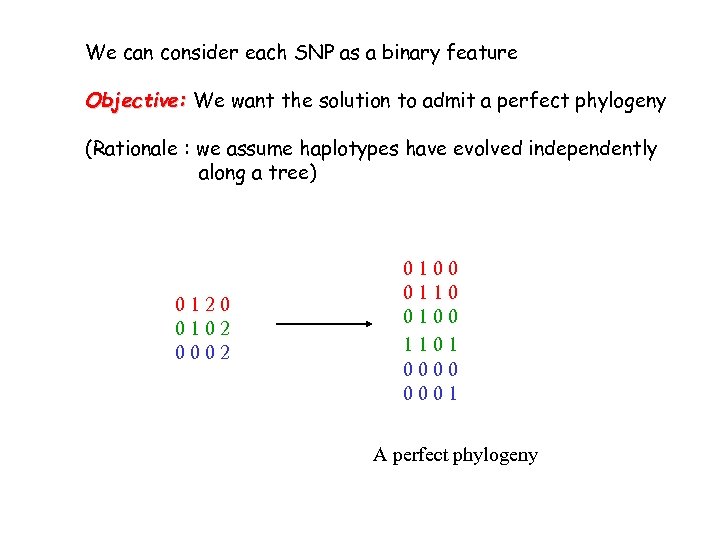

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020 0100 0110 1101 0100 1000 0010

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020 0100 0110 1101 0100 1000 0010

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020 0100 0110 1101 0100 1000 0010 NOT a perfect phylogeny solution !

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 2102 2020 0100 0110 1101 0100 1000 0010 NOT a perfect phylogeny solution !

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 0102 0002

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 0102 0002

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 0102 0002 0100 0110 0100 1101 0000 0001 A perfect phylogeny

We can consider each SNP as a binary feature Objective: We want the solution to admit a perfect phylogeny (Rationale : we assume haplotypes have evolved independently along a tree) 0120 0102 0002 0100 0110 0100 1101 0000 0001 A perfect phylogeny

Theorem: The Perfect Phylogeny Haplotyping problem is polynomial

Theorem: The Perfect Phylogeny Haplotyping problem is polynomial

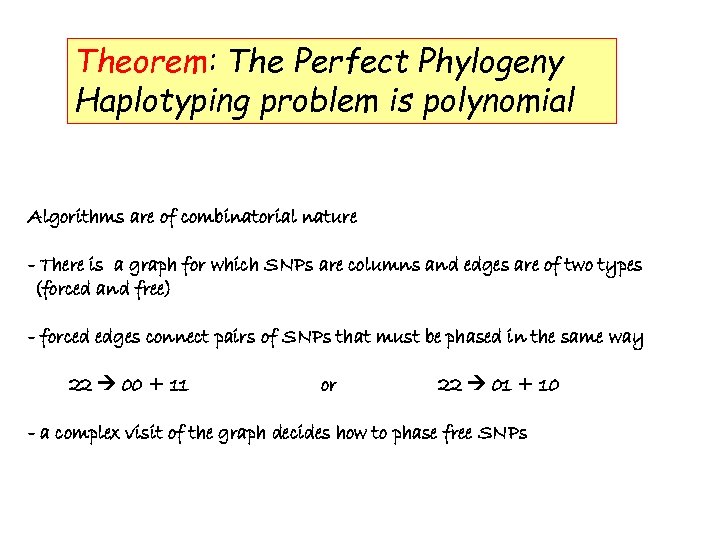

Theorem: The Perfect Phylogeny Haplotyping problem is polynomial Algorithms are of combinatorial nature - There is a graph for which SNPs are columns and edges are of two types (forced and free) - forced edges connect pairs of SNPs that must be phased in the same way 22 00 + 11 or 22 01 + 10 - a complex visit of the graph decides how to phase free SNPs

Theorem: The Perfect Phylogeny Haplotyping problem is polynomial Algorithms are of combinatorial nature - There is a graph for which SNPs are columns and edges are of two types (forced and free) - forced edges connect pairs of SNPs that must be phased in the same way 22 00 + 11 or 22 01 + 10 - a complex visit of the graph decides how to phase free SNPs

4 th Obj: Disease Association

4 th Obj: Disease Association

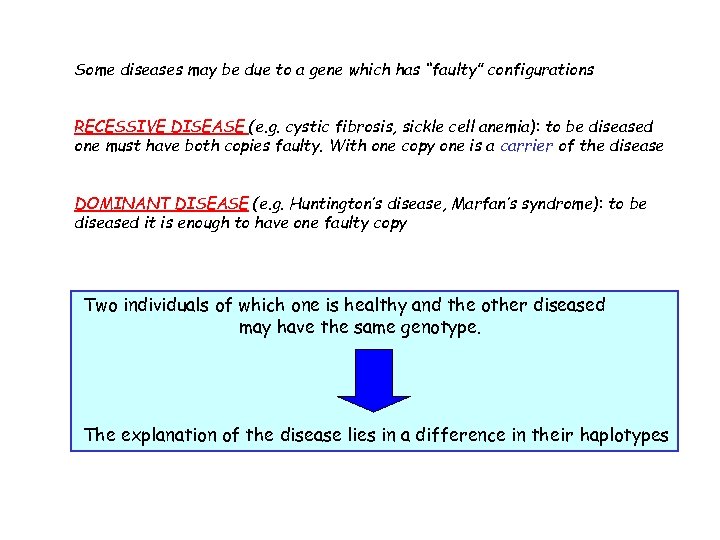

Some diseases may be due to a gene which has “faulty” configurations RECESSIVE DISEASE (e. g. cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia): to be diseased one must have both copies faulty. With one copy one is a carrier of the disease DOMINANT DISEASE (e. g. Huntington’s disease, Marfan’s syndrome): to be diseased it is enough to have one faulty copy Two individuals of which one is healthy and the other diseased may have the same genotype. The explanation of the disease lies in a difference in their haplotypes

Some diseases may be due to a gene which has “faulty” configurations RECESSIVE DISEASE (e. g. cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia): to be diseased one must have both copies faulty. With one copy one is a carrier of the disease DOMINANT DISEASE (e. g. Huntington’s disease, Marfan’s syndrome): to be diseased it is enough to have one faulty copy Two individuals of which one is healthy and the other diseased may have the same genotype. The explanation of the disease lies in a difference in their haplotypes

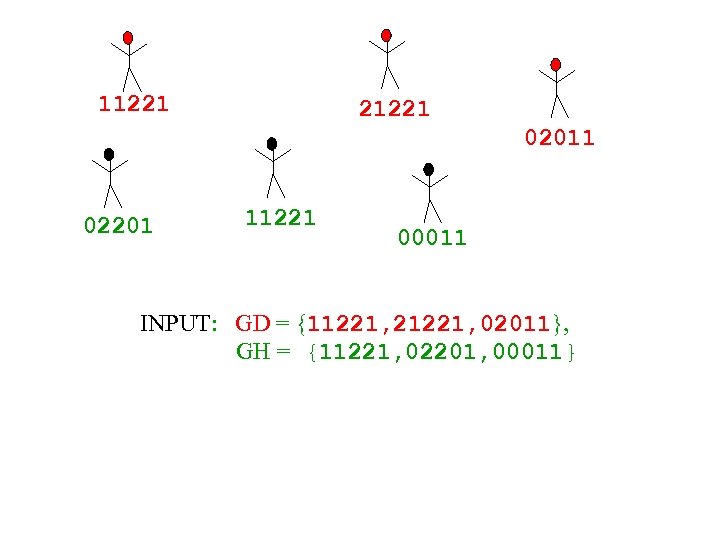

11221 21221 02011 02201 11221 00011 INPUT: GD = {11221, 21221, 02011}, GH = {11221, 02201, 00011}

11221 21221 02011 02201 11221 00011 INPUT: GD = {11221, 21221, 02011}, GH = {11221, 02201, 00011}

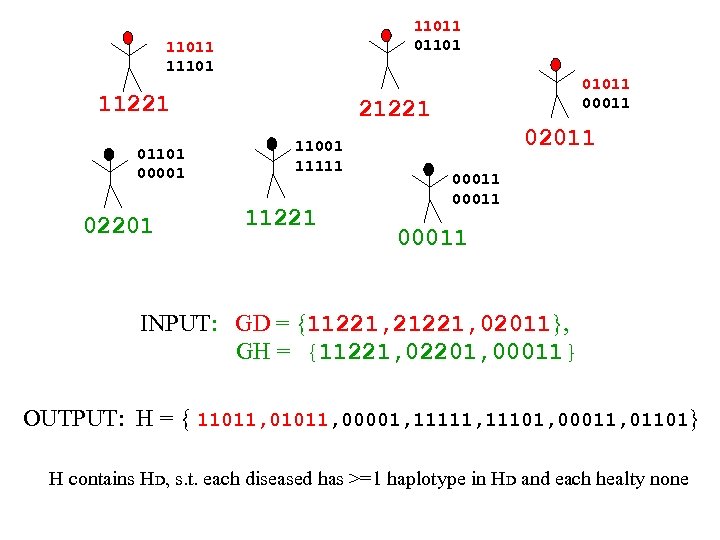

11011 011011 11101 11221 01101 00001 02201 01011 00011 21221 11001 11111 11221 02011 00011 INPUT: GD = {11221, 21221, 02011}, GH = {11221, 02201, 00011} OUTPUT: H = { 11011, 00001, 11111, 11101, 00011, 01101} H contains HD, s. t. each diseased has >=1 haplotype in HD and each healty none

11011 011011 11101 11221 01101 00001 02201 01011 00011 21221 11001 11111 11221 02011 00011 INPUT: GD = {11221, 21221, 02011}, GH = {11221, 02201, 00011} OUTPUT: H = { 11011, 00001, 11111, 11101, 00011, 01101} H contains HD, s. t. each diseased has >=1 haplotype in HD and each healty none

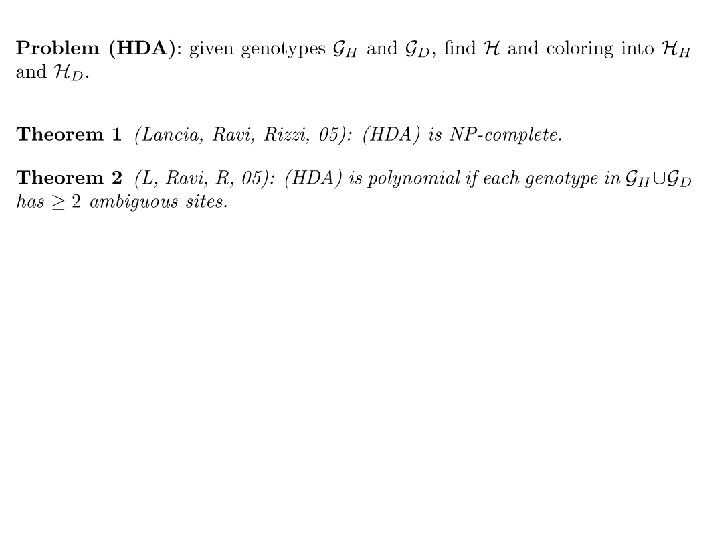

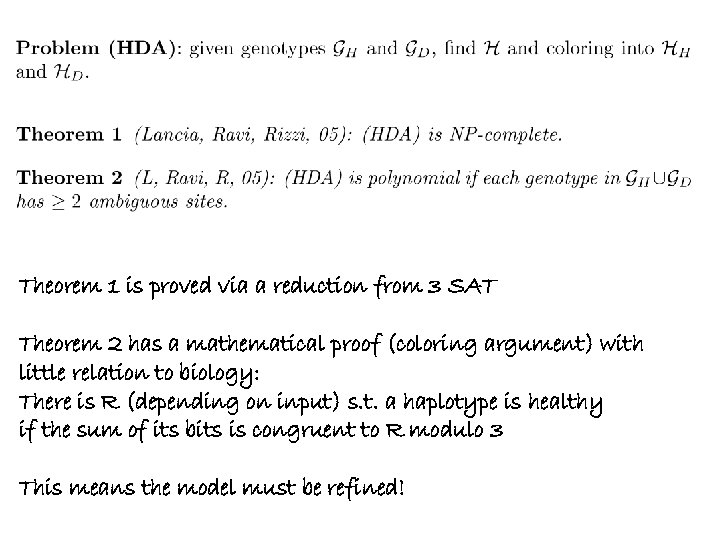

Theorem 1 is proved via a reduction from 3 SAT Theorem 2 has a mathematical proof (coloring argument) with little relation to biology: There is R (depending on input) s. t. a haplotype is healthy if the sum of its bits is congruent to R modulo 3 This means the model must be refined!

Theorem 1 is proved via a reduction from 3 SAT Theorem 2 has a mathematical proof (coloring argument) with little relation to biology: There is R (depending on input) s. t. a haplotype is healthy if the sum of its bits is congruent to R modulo 3 This means the model must be refined!

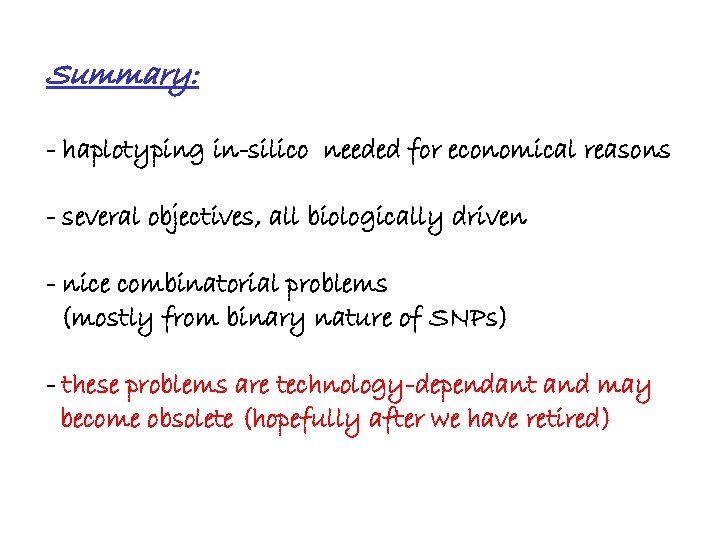

Summary: - haplotyping in-silico needed for economical reasons - several objectives, all biologically driven - nice combinatorial problems (mostly from binary nature of SNPs) - these problems are technology-dependant and may become obsolete (hopefully after we have retired)

Summary: - haplotyping in-silico needed for economical reasons - several objectives, all biologically driven - nice combinatorial problems (mostly from binary nature of SNPs) - these problems are technology-dependant and may become obsolete (hopefully after we have retired)

Thanks

Thanks