0384b41bf9578e9f116578c657f8a17e.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 53

The Perceptions of International Doctoral Students within the Context of a Continuum Model of Research Group Microclimate Elaine Walsh Senior Lecturer, Graduate Schools Imperial College London

The Perceptions of International Doctoral Students within the Context of a Continuum Model of Research Group Microclimate Elaine Walsh Senior Lecturer, Graduate Schools Imperial College London

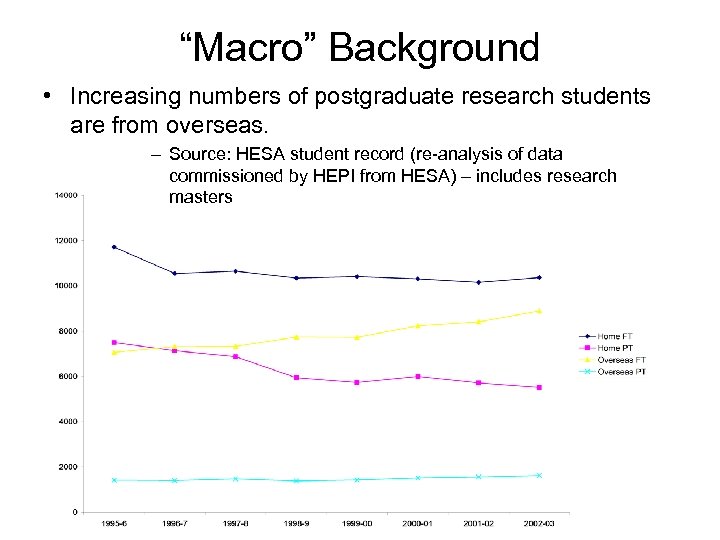

“Macro” Background • Increasing numbers of postgraduate research students are from overseas. – Source: HESA student record (re-analysis of data commissioned by HEPI from HESA) – includes research masters

“Macro” Background • Increasing numbers of postgraduate research students are from overseas. – Source: HESA student record (re-analysis of data commissioned by HEPI from HESA) – includes research masters

UKCOSA findings • International students with UK friends were more likely to be satisfied overall with their stay in the UK • 93% vs 86% – “Broadening Our Horizons, 2004 • More likely to have UK friends: – Women, younger, no dependants, undergraduates, studying science or medicine

UKCOSA findings • International students with UK friends were more likely to be satisfied overall with their stay in the UK • 93% vs 86% – “Broadening Our Horizons, 2004 • More likely to have UK friends: – Women, younger, no dependants, undergraduates, studying science or medicine

Doctoral students • Very little formal curriculum • The “myth” of the research group in science and technology • Relatively little research done from the student perspective – Leonard et al, Lit review for HEA (2006)

Doctoral students • Very little formal curriculum • The “myth” of the research group in science and technology • Relatively little research done from the student perspective – Leonard et al, Lit review for HEA (2006)

“Micro” Background • New developments following “Roberts’” funding – A 3 -day residential course for new Ph. D students attended by roughly 60% of cohort – “Developing Cultural Awareness” workshops • 29% of Ph. D student body from non-EU • 4 -year submission rates slightly lower for overseas Ph. Ds

“Micro” Background • New developments following “Roberts’” funding – A 3 -day residential course for new Ph. D students attended by roughly 60% of cohort – “Developing Cultural Awareness” workshops • 29% of Ph. D student body from non-EU • 4 -year submission rates slightly lower for overseas Ph. Ds

Method • Part of a broader, qualitative study • What do overseas Ph. D students perceive as the biggest problems and barriers to overcome when undertaking their doctoral study? • Levels of interactions with home students emerged as one issue

Method • Part of a broader, qualitative study • What do overseas Ph. D students perceive as the biggest problems and barriers to overcome when undertaking their doctoral study? • Levels of interactions with home students emerged as one issue

Phase 1: Letters • Written as if to a friend or family member about to begin a Ph. D at the same institution • Using their experience to advise about difficulties and problems and how to deal with them • 18 were received • Analysis to identify the main issues

Phase 1: Letters • Written as if to a friend or family member about to begin a Ph. D at the same institution • Using their experience to advise about difficulties and problems and how to deal with them • 18 were received • Analysis to identify the main issues

Phase 2: • 9 follow up interviews – 8 from letter writers and 1 invited participant • Asked about their workplace interactions, social interactions, supervision, motivation during their Ph. D, biggest difficulties encountered, etc.

Phase 2: • 9 follow up interviews – 8 from letter writers and 1 invited participant • Asked about their workplace interactions, social interactions, supervision, motivation during their Ph. D, biggest difficulties encountered, etc.

Bias in the sample • Bias towards those who feel confident in writing English (one exception) • Bias towards those with more problems or difficulties • More outgoing than the norm, since (with one exception) they volunteered for the study • But: All were expecting to submit within 4 years

Bias in the sample • Bias towards those who feel confident in writing English (one exception) • Bias towards those with more problems or difficulties • More outgoing than the norm, since (with one exception) they volunteered for the study • But: All were expecting to submit within 4 years

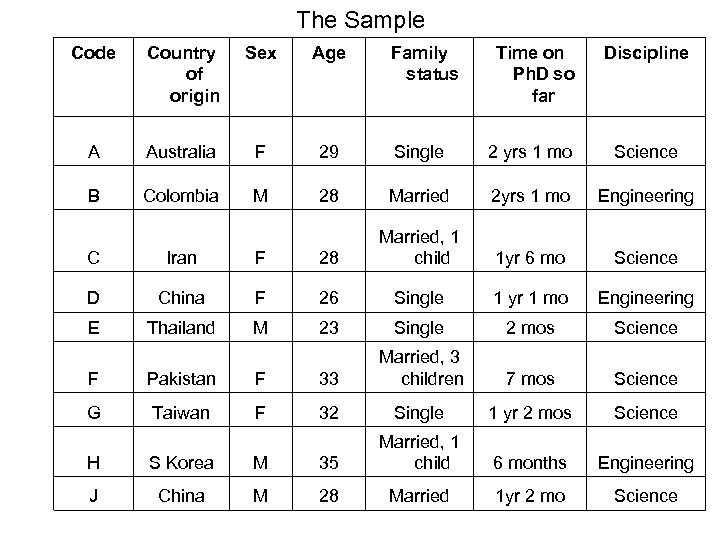

The Sample Code Country of origin Sex Age A Australia F 29 B Colombia M Family status Time on Ph. D so far Discipline Single 2 yrs 1 mo Science 28 Married 2 yrs 1 mo Engineering 1 yr 6 mo Science C Iran F 28 Married, 1 child D China F 26 Single 1 yr 1 mo Engineering E Thailand M 23 Single 2 mos Science 7 mos Science F Pakistan F 33 Married, 3 children G Taiwan F 32 Single 1 yr 2 mos Science 6 months Engineering 1 yr 2 mo Science H S Korea M 35 Married, 1 child J China M 28 Married

The Sample Code Country of origin Sex Age A Australia F 29 B Colombia M Family status Time on Ph. D so far Discipline Single 2 yrs 1 mo Science 28 Married 2 yrs 1 mo Engineering 1 yr 6 mo Science C Iran F 28 Married, 1 child D China F 26 Single 1 yr 1 mo Engineering E Thailand M 23 Single 2 mos Science 7 mos Science F Pakistan F 33 Married, 3 children G Taiwan F 32 Single 1 yr 2 mos Science 6 months Engineering 1 yr 2 mo Science H S Korea M 35 Married, 1 child J China M 28 Married

The Ph. D Experience • • Widely varying sample Ages 23 – 35 From single to married with 3 children Circumstances and motivations very considerably

The Ph. D Experience • • Widely varying sample Ages 23 – 35 From single to married with 3 children Circumstances and motivations very considerably

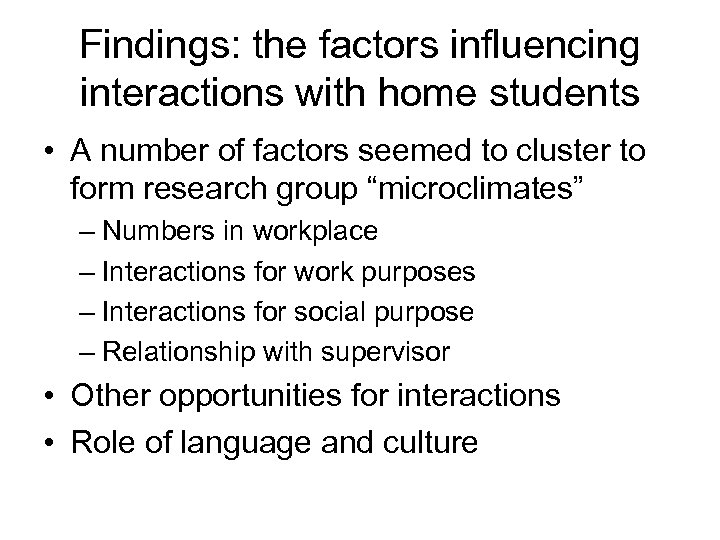

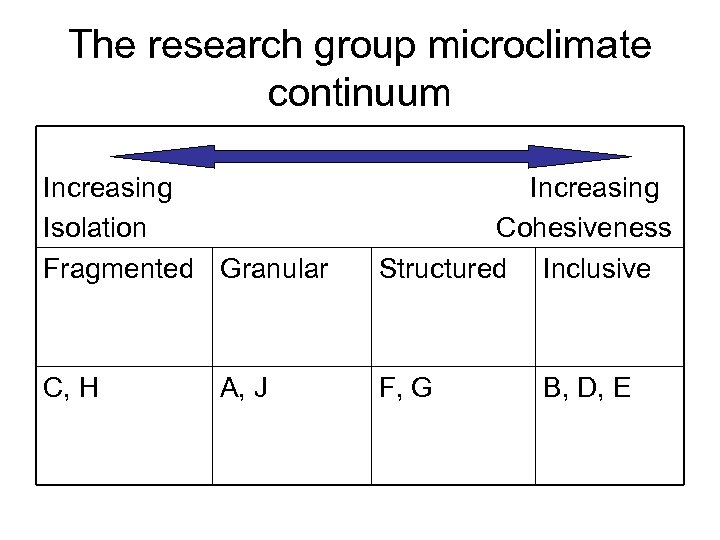

Findings: the factors influencing interactions with home students • A number of factors seemed to cluster to form research group “microclimates” – Numbers in workplace – Interactions for work purposes – Interactions for social purpose – Relationship with supervisor • Other opportunities for interactions • Role of language and culture

Findings: the factors influencing interactions with home students • A number of factors seemed to cluster to form research group “microclimates” – Numbers in workplace – Interactions for work purposes – Interactions for social purpose – Relationship with supervisor • Other opportunities for interactions • Role of language and culture

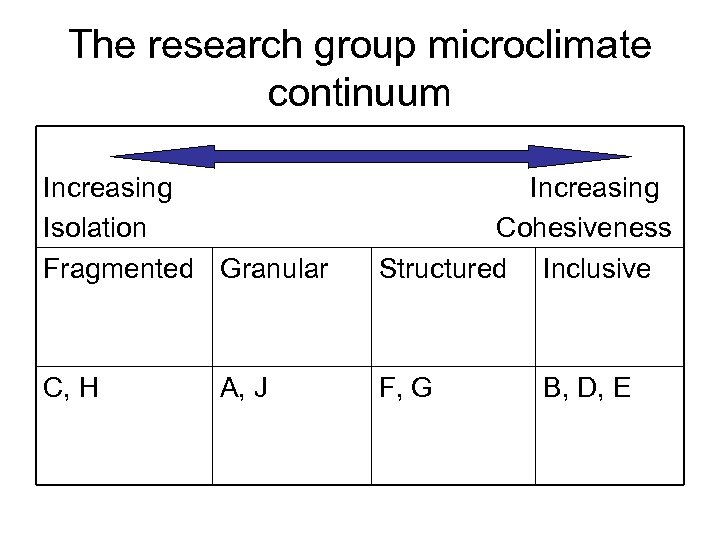

The research group microclimate continuum Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive C, H F, G A, J B, D, E

The research group microclimate continuum Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive C, H F, G A, J B, D, E

Inclusive groups • The ideal • Overseas students participate fully in the life of the research group • Good relationships regardless of nationality • “like a family” – Relaxed, uninhibited, frank • The “myth” frequently written about

Inclusive groups • The ideal • Overseas students participate fully in the life of the research group • Good relationships regardless of nationality • “like a family” – Relaxed, uninhibited, frank • The “myth” frequently written about

Structured groups • More hierarchy • Social and work interactions are less natural • Like a different sort of family – More power, less frankness

Structured groups • More hierarchy • Social and work interactions are less natural • Like a different sort of family – More power, less frankness

Granular groups • “. . it is too difficult to communicate, and I think what we lose in the group is a good connector, to connect each other together, nobody’s in the role of this, and that’s why a group is like a group of loose sand. ” • Much less interaction amongst the group

Granular groups • “. . it is too difficult to communicate, and I think what we lose in the group is a good connector, to connect each other together, nobody’s in the role of this, and that’s why a group is like a group of loose sand. ” • Much less interaction amongst the group

Fragmented groups • Most isolating situation • A problem factor inhibits “normal” interactions – E. g. absent supervisor, unhelpful or obstructive colleagues, physical isolation of students.

Fragmented groups • Most isolating situation • A problem factor inhibits “normal” interactions – E. g. absent supervisor, unhelpful or obstructive colleagues, physical isolation of students.

The research group microclimate continuum Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive C, H F, G A, J B, D, E

The research group microclimate continuum Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive C, H F, G A, J B, D, E

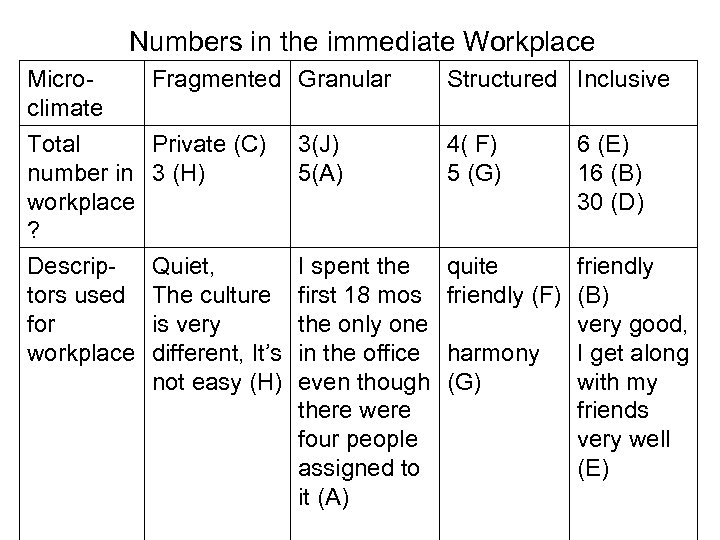

Numbers in the immediate Workplace Micro. Fragmented Granular climate Total Private (C) 3(J) number in 3 (H) 5(A) workplace ? Structured Inclusive Descriptors used for workplace quite friendly (F) (B) very good, harmony I get along (G) with my friends very well (E) Quiet, The culture is very different, It’s not easy (H) I spent the first 18 mos the only one in the office even though there were four people assigned to it (A) 4( F) 5 (G) 6 (E) 16 (B) 30 (D)

Numbers in the immediate Workplace Micro. Fragmented Granular climate Total Private (C) 3(J) number in 3 (H) 5(A) workplace ? Structured Inclusive Descriptors used for workplace quite friendly (F) (B) very good, harmony I get along (G) with my friends very well (E) Quiet, The culture is very different, It’s not easy (H) I spent the first 18 mos the only one in the office even though there were four people assigned to it (A) 4( F) 5 (G) 6 (E) 16 (B) 30 (D)

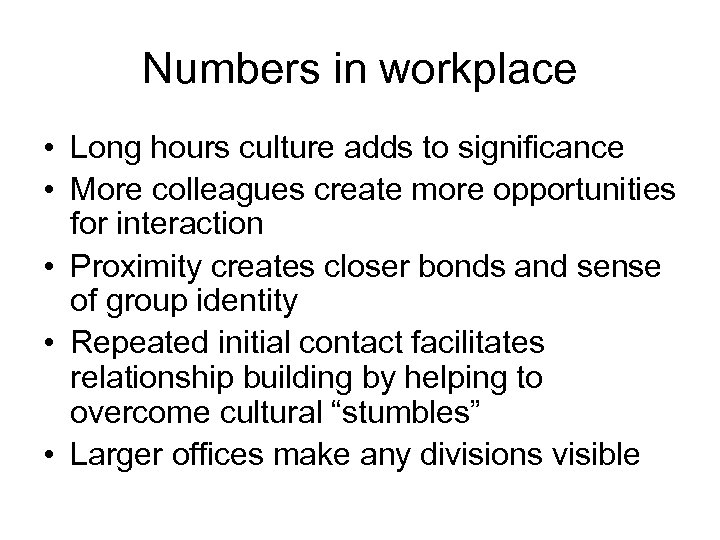

Numbers in workplace • Long hours culture adds to significance • More colleagues create more opportunities for interaction • Proximity creates closer bonds and sense of group identity • Repeated initial contact facilitates relationship building by helping to overcome cultural “stumbles” • Larger offices make any divisions visible

Numbers in workplace • Long hours culture adds to significance • More colleagues create more opportunities for interaction • Proximity creates closer bonds and sense of group identity • Repeated initial contact facilitates relationship building by helping to overcome cultural “stumbles” • Larger offices make any divisions visible

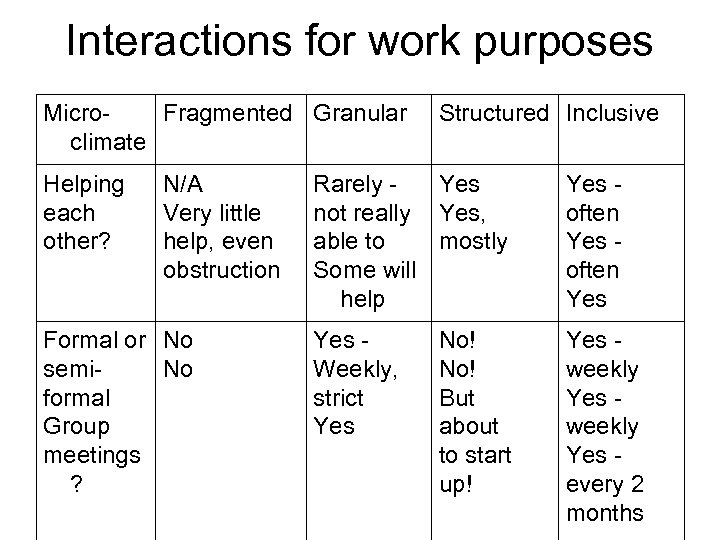

Interactions for work purposes Micro. Fragmented Granular climate Helping each other? N/A Very little help, even obstruction Formal or No semi. No formal Group meetings ? Structured Inclusive Rarely Yes not really Yes, able to mostly Some will help Yes often Yes Weekly, strict Yes weekly Yes every 2 months No! But about to start up!

Interactions for work purposes Micro. Fragmented Granular climate Helping each other? N/A Very little help, even obstruction Formal or No semi. No formal Group meetings ? Structured Inclusive Rarely Yes not really Yes, able to mostly Some will help Yes often Yes Weekly, strict Yes weekly Yes every 2 months No! But about to start up!

Work interactions • Clear progression regarding the giving and receiving of help – Normal and common to help each other vs. “read the manual!” approach • Group meetings in inclusive groups were frequent and often had a social aspect • Fragmented groups had no group meetings • Granular groups had strict, stressful meetings for work purposes only.

Work interactions • Clear progression regarding the giving and receiving of help – Normal and common to help each other vs. “read the manual!” approach • Group meetings in inclusive groups were frequent and often had a social aspect • Fragmented groups had no group meetings • Granular groups had strict, stressful meetings for work purposes only.

Granular group meeting • “No we are not allowed, we are not permitted, or we are not expected to chat with coffee, we have to take our notes, report what we have done, that is it, maybe lasting one or one and a half hours each week, and we don’t have personal chat, personal communications. ”

Granular group meeting • “No we are not allowed, we are not permitted, or we are not expected to chat with coffee, we have to take our notes, report what we have done, that is it, maybe lasting one or one and a half hours each week, and we don’t have personal chat, personal communications. ”

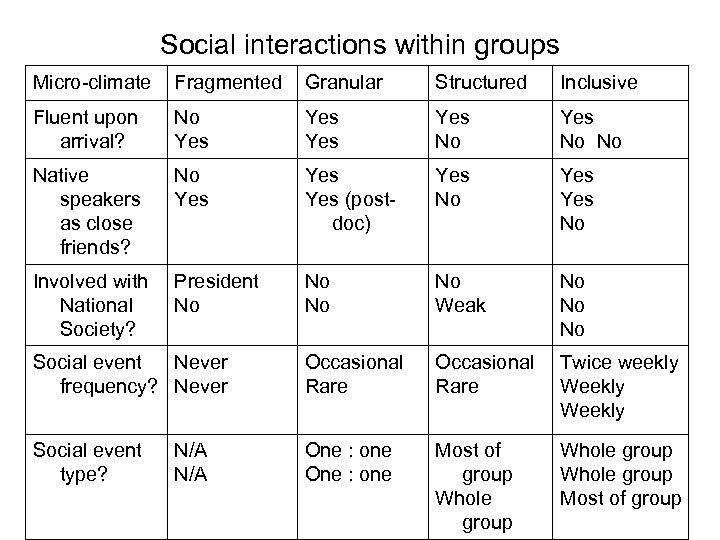

Social interactions within groups Micro-climate Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive Fluent upon arrival? No Yes Yes No No Native speakers as close friends? No Yes Yes (postdoc) Yes No Involved with National Society? President No No Weak No No No Social event Never frequency? Never Occasional Rare Twice weekly Weekly Social event type? One : one Most of group Whole group Most of group N/A

Social interactions within groups Micro-climate Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive Fluent upon arrival? No Yes Yes No No Native speakers as close friends? No Yes Yes (postdoc) Yes No Involved with National Society? President No No Weak No No No Social event Never frequency? Never Occasional Rare Twice weekly Weekly Social event type? One : one Most of group Whole group Most of group N/A

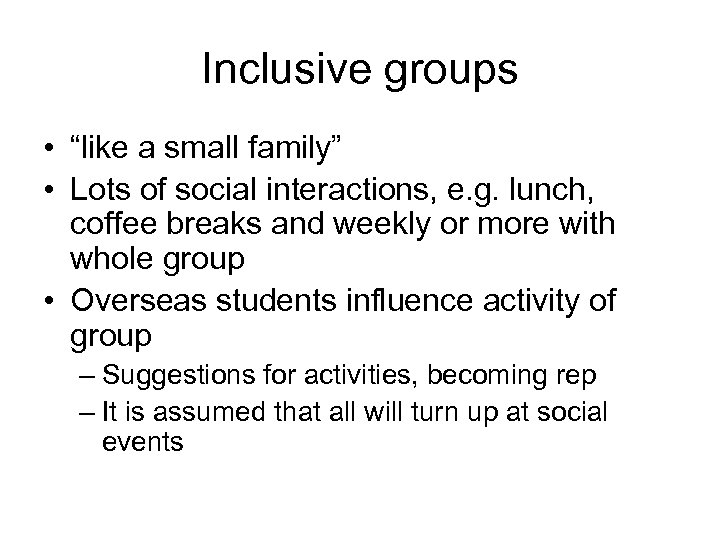

Inclusive groups • “like a small family” • Lots of social interactions, e. g. lunch, coffee breaks and weekly or more with whole group • Overseas students influence activity of group – Suggestions for activities, becoming rep – It is assumed that all will turn up at social events

Inclusive groups • “like a small family” • Lots of social interactions, e. g. lunch, coffee breaks and weekly or more with whole group • Overseas students influence activity of group – Suggestions for activities, becoming rep – It is assumed that all will turn up at social events

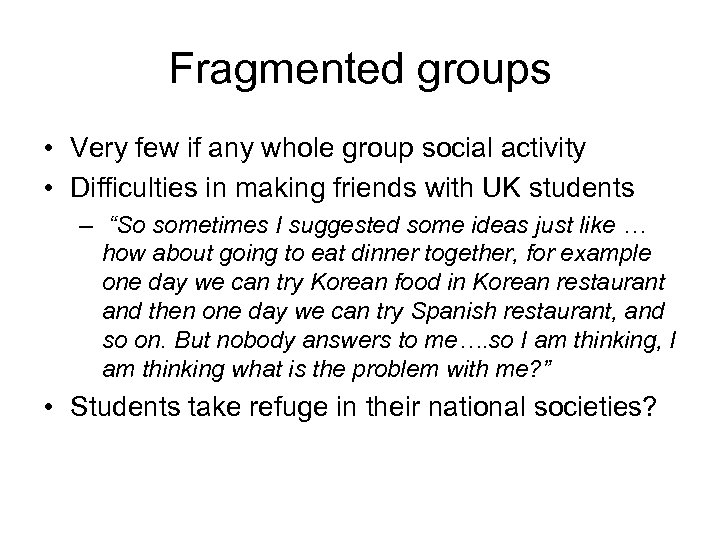

Fragmented groups • Very few if any whole group social activity • Difficulties in making friends with UK students – “So sometimes I suggested some ideas just like … how about going to eat dinner together, for example one day we can try Korean food in Korean restaurant and then one day we can try Spanish restaurant, and so on. But nobody answers to me…. so I am thinking, I am thinking what is the problem with me? ” • Students take refuge in their national societies?

Fragmented groups • Very few if any whole group social activity • Difficulties in making friends with UK students – “So sometimes I suggested some ideas just like … how about going to eat dinner together, for example one day we can try Korean food in Korean restaurant and then one day we can try Spanish restaurant, and so on. But nobody answers to me…. so I am thinking, I am thinking what is the problem with me? ” • Students take refuge in their national societies?

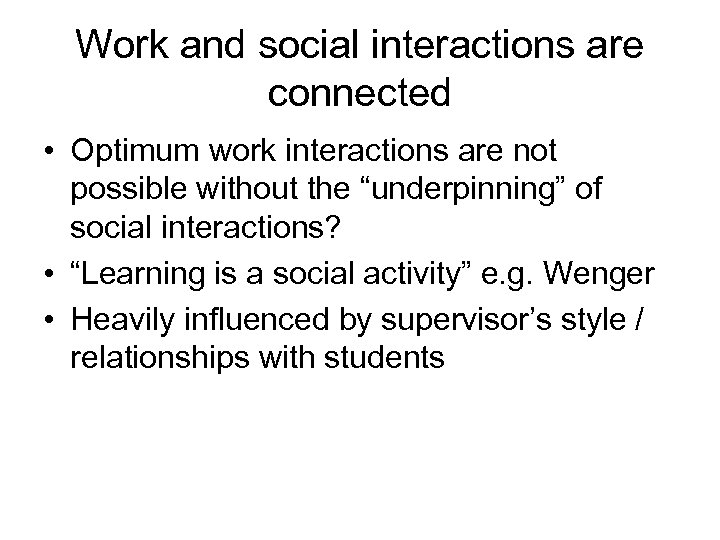

Work and social interactions are connected • Optimum work interactions are not possible without the “underpinning” of social interactions? • “Learning is a social activity” e. g. Wenger • Heavily influenced by supervisor’s style / relationships with students

Work and social interactions are connected • Optimum work interactions are not possible without the “underpinning” of social interactions? • “Learning is a social activity” e. g. Wenger • Heavily influenced by supervisor’s style / relationships with students

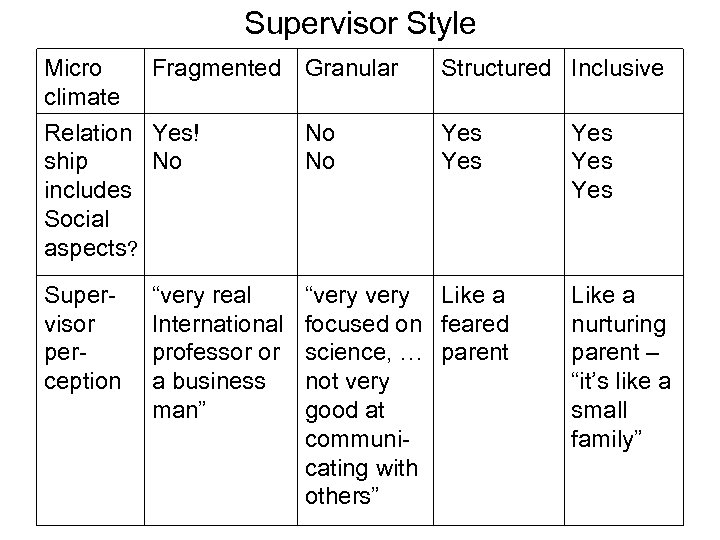

Supervisor Style Micro Fragmented Granular climate Relation Yes! No ship No No includes Social aspects? Supervisor perception “very real International professor or a business man” Structured Inclusive Yes “very Like a focused on feared science, … parent not very good at communicating with others” Yes Yes Like a nurturing parent – “it’s like a small family”

Supervisor Style Micro Fragmented Granular climate Relation Yes! No ship No No includes Social aspects? Supervisor perception “very real International professor or a business man” Structured Inclusive Yes “very Like a focused on feared science, … parent not very good at communicating with others” Yes Yes Like a nurturing parent – “it’s like a small family”

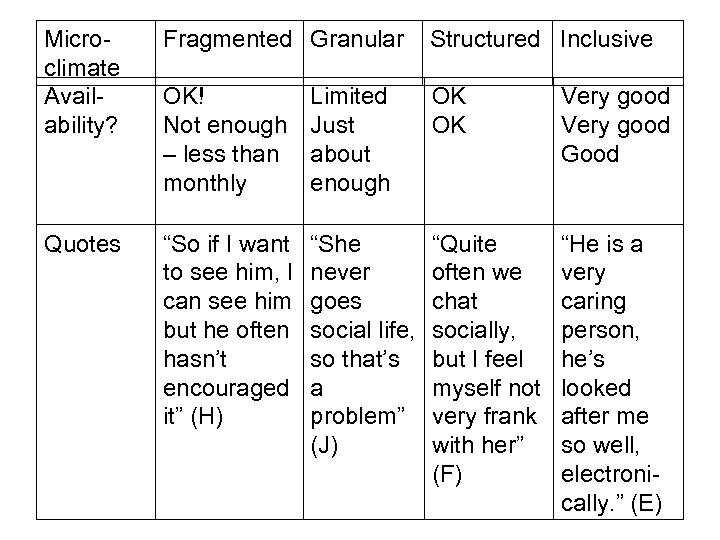

Microclimate Availability? Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive OK! Not enough – less than monthly Limited Just about enough OK OK Very good Good Quotes “So if I want to see him, I can see him but he often hasn’t encouraged it” (H) “She never goes social life, so that’s a problem” (J) “Quite often we chat socially, but I feel myself not very frank with her” (F) “He is a very caring person, he’s looked after me so well, electronically. ” (E)

Microclimate Availability? Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive OK! Not enough – less than monthly Limited Just about enough OK OK Very good Good Quotes “So if I want to see him, I can see him but he often hasn’t encouraged it” (H) “She never goes social life, so that’s a problem” (J) “Quite often we chat socially, but I feel myself not very frank with her” (F) “He is a very caring person, he’s looked after me so well, electronically. ” (E)

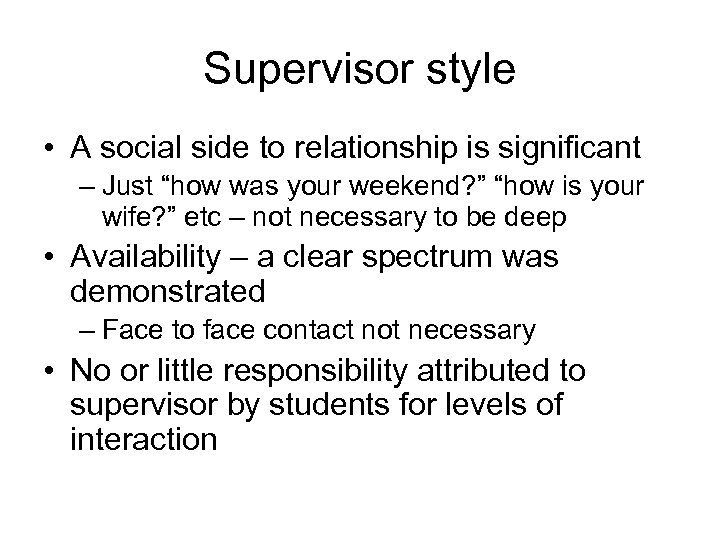

Supervisor style • A social side to relationship is significant – Just “how was your weekend? ” “how is your wife? ” etc – not necessary to be deep • Availability – a clear spectrum was demonstrated – Face to face contact not necessary • No or little responsibility attributed to supervisor by students for levels of interaction

Supervisor style • A social side to relationship is significant – Just “how was your weekend? ” “how is your wife? ” etc – not necessary to be deep • Availability – a clear spectrum was demonstrated – Face to face contact not necessary • No or little responsibility attributed to supervisor by students for levels of interaction

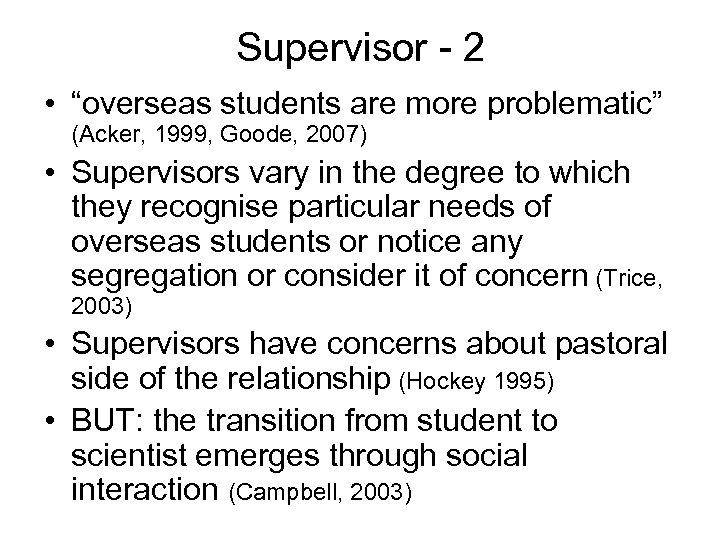

Supervisor - 2 • “overseas students are more problematic” (Acker, 1999, Goode, 2007) • Supervisors vary in the degree to which they recognise particular needs of overseas students or notice any segregation or consider it of concern (Trice, 2003) • Supervisors have concerns about pastoral side of the relationship (Hockey 1995) • BUT: the transition from student to scientist emerges through social interaction (Campbell, 2003)

Supervisor - 2 • “overseas students are more problematic” (Acker, 1999, Goode, 2007) • Supervisors vary in the degree to which they recognise particular needs of overseas students or notice any segregation or consider it of concern (Trice, 2003) • Supervisors have concerns about pastoral side of the relationship (Hockey 1995) • BUT: the transition from student to scientist emerges through social interaction (Campbell, 2003)

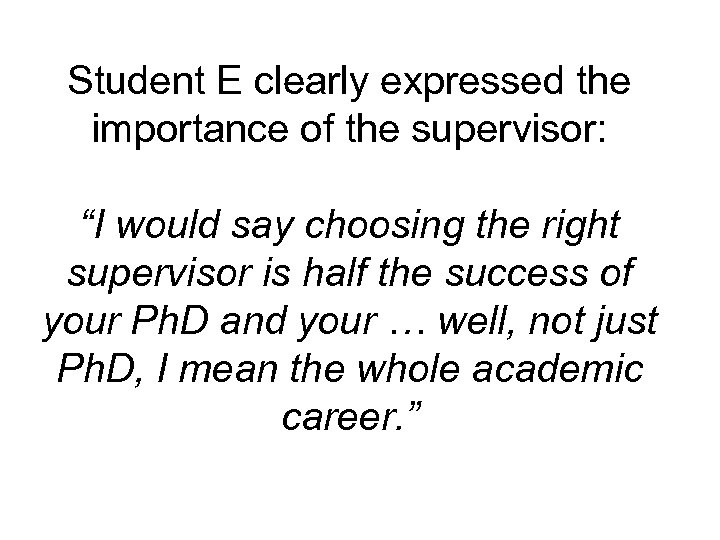

Student E clearly expressed the importance of the supervisor: “I would say choosing the right supervisor is half the success of your Ph. D and your … well, not just Ph. D, I mean the whole academic career. ”

Student E clearly expressed the importance of the supervisor: “I would say choosing the right supervisor is half the success of your Ph. D and your … well, not just Ph. D, I mean the whole academic career. ”

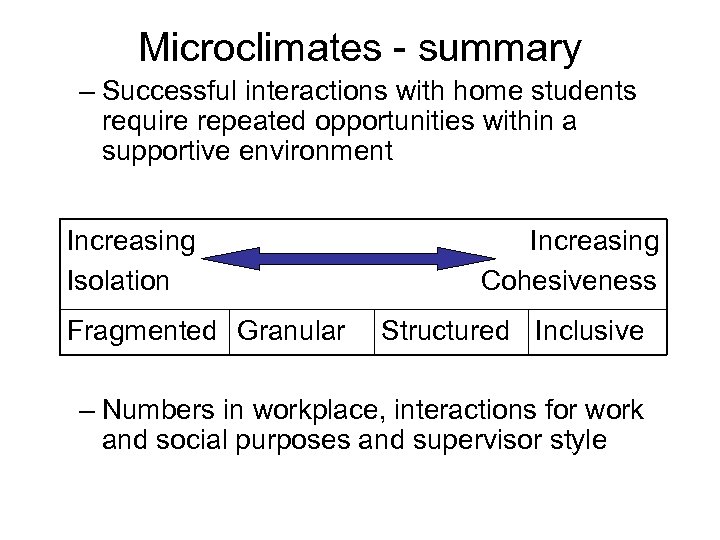

Microclimates - summary – Successful interactions with home students require repeated opportunities within a supportive environment Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive – Numbers in workplace, interactions for work and social purposes and supervisor style

Microclimates - summary – Successful interactions with home students require repeated opportunities within a supportive environment Increasing Isolation Fragmented Granular Increasing Cohesiveness Structured Inclusive – Numbers in workplace, interactions for work and social purposes and supervisor style

Other opportunities for interactions with UK nationals beyond the research group • Students felt that opportunity was the limiting factor • The residential course for new Ph. D students was an important enabling factor for those in fragmented and granular groups.

Other opportunities for interactions with UK nationals beyond the research group • Students felt that opportunity was the limiting factor • The residential course for new Ph. D students was an important enabling factor for those in fragmented and granular groups.

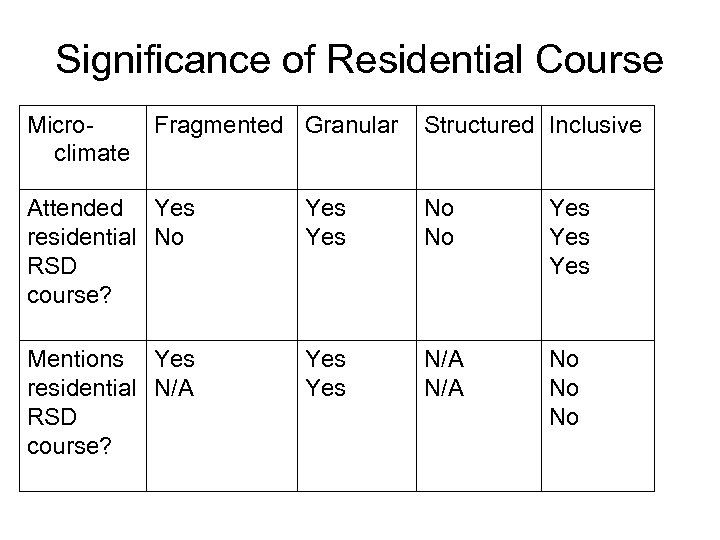

Significance of Residential Course Microclimate Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive Attended Yes residential No RSD course? Yes No No Yes Yes Mentions Yes residential N/A RSD course? Yes N/A No No No

Significance of Residential Course Microclimate Fragmented Granular Structured Inclusive Attended Yes residential No RSD course? Yes No No Yes Yes Mentions Yes residential N/A RSD course? Yes N/A No No No

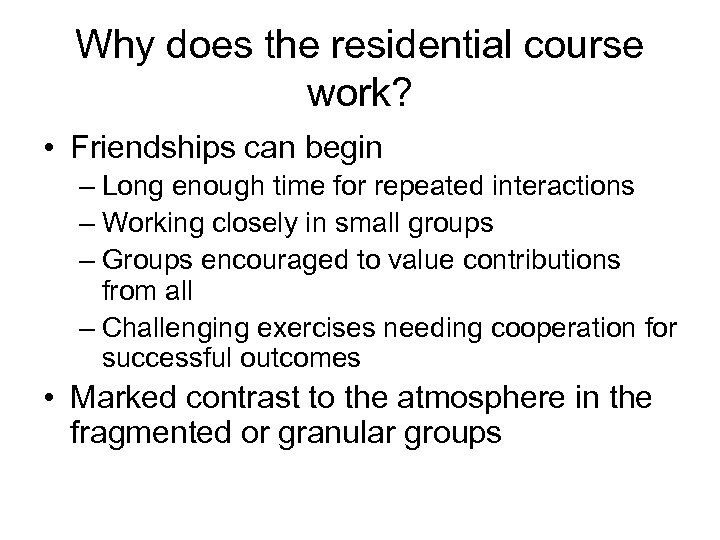

Why does the residential course work? • Friendships can begin – Long enough time for repeated interactions – Working closely in small groups – Groups encouraged to value contributions from all – Challenging exercises needing cooperation for successful outcomes • Marked contrast to the atmosphere in the fragmented or granular groups

Why does the residential course work? • Friendships can begin – Long enough time for repeated interactions – Working closely in small groups – Groups encouraged to value contributions from all – Challenging exercises needing cooperation for successful outcomes • Marked contrast to the atmosphere in the fragmented or granular groups

The role of language and culture • 8/9 were non-native speakers • Began Ph. Ds with varying levels of language ability from basic to fluent • When speaking with UK nationals they reported as difficulties: – Vocabulary (technical or general) – Accent – Cultural complications

The role of language and culture • 8/9 were non-native speakers • Began Ph. Ds with varying levels of language ability from basic to fluent • When speaking with UK nationals they reported as difficulties: – Vocabulary (technical or general) – Accent – Cultural complications

“in my first year I took an undergraduate course in our department, and I thought that was quite helpful to, you know, help me to catch up the words, to catch up the knowledge because. . in my mind, all the knowledge was in Chinese, so I had to find a bridge to connect or to translate it [into] English. ” • What was the principle value of taking this class?

“in my first year I took an undergraduate course in our department, and I thought that was quite helpful to, you know, help me to catch up the words, to catch up the knowledge because. . in my mind, all the knowledge was in Chinese, so I had to find a bridge to connect or to translate it [into] English. ” • What was the principle value of taking this class?

Interactions with other NNES • Some commented that it was easier to speak with other non-native speakers – Simpler vocabulary – Accent easier in the beginning – More patience in other person – Slower paced delivery – Fewer opaque cultural references

Interactions with other NNES • Some commented that it was easier to speak with other non-native speakers – Simpler vocabulary – Accent easier in the beginning – More patience in other person – Slower paced delivery – Fewer opaque cultural references

Cultural issues • British are hard to know – “British reserve” • Problems cited include alcohol, humour, not knowing about TV etc • Individual students show limited awareness of cultural differences • Pragmatic competence is an issue, i. e. meaning within a cultural context

Cultural issues • British are hard to know – “British reserve” • Problems cited include alcohol, humour, not knowing about TV etc • Individual students show limited awareness of cultural differences • Pragmatic competence is an issue, i. e. meaning within a cultural context

Pragmatic Competence – I sometimes suggested ‘how about, today is Friday, how about going to a pub to drink? ’ but the English guy refused to join, yes. Yes I can understand, if I talk with English people the conversation sometimes stops and it’s not comfortable for each other and they can, ‘yes he’s not interesting’, so yes.

Pragmatic Competence – I sometimes suggested ‘how about, today is Friday, how about going to a pub to drink? ’ but the English guy refused to join, yes. Yes I can understand, if I talk with English people the conversation sometimes stops and it’s not comfortable for each other and they can, ‘yes he’s not interesting’, so yes.

Cultural barriers • First few encounters may not go well – “How are you? ” “Tell me about it? ” (“Is the pope a Catholic? ”) • Can reinforce the desire to seek “refuge” with co-nationals • A unrecognised, unmet need exists for cultural awareness training – For example….

Cultural barriers • First few encounters may not go well – “How are you? ” “Tell me about it? ” (“Is the pope a Catholic? ”) • Can reinforce the desire to seek “refuge” with co-nationals • A unrecognised, unmet need exists for cultural awareness training – For example….

…in one of the inclusive groups, student D told of a quiz. She had gone along but had only been able to score one point. • “Yeah, because there are like four sections and then the first three sections are all about the American or English history and European history and I don’t know anything, and then the last session is about the techniques in the department, like the equipment like, the material. ”

…in one of the inclusive groups, student D told of a quiz. She had gone along but had only been able to score one point. • “Yeah, because there are like four sections and then the first three sections are all about the American or English history and European history and I don’t know anything, and then the last session is about the techniques in the department, like the equipment like, the material. ”

Risk of marginalisation (e. g. Wenger, 1998) • All new research students may experience peripherality – Not necessarily problematic – Depends on trajectory • A higher risk in fragmented or granular groups that overseas students will be defined by their non-participation and become marginalised

Risk of marginalisation (e. g. Wenger, 1998) • All new research students may experience peripherality – Not necessarily problematic – Depends on trajectory • A higher risk in fragmented or granular groups that overseas students will be defined by their non-participation and become marginalised

Closing thoughts • How can a potential overseas Ph. D student accurately assess the microclimate of groups? (Wu, 2002) • The presence of repeated opportunities for interactions and the encouragement of a supervisor are key • When a microclimate is less “healthy” international students are the first to suffer (Canaries in the coalmine – Carroll & Ryan, 2005)

Closing thoughts • How can a potential overseas Ph. D student accurately assess the microclimate of groups? (Wu, 2002) • The presence of repeated opportunities for interactions and the encouragement of a supervisor are key • When a microclimate is less “healthy” international students are the first to suffer (Canaries in the coalmine – Carroll & Ryan, 2005)

Some recommendations for action: Universities • Addressing marginalisation of overseas students as a institutional responsibility (Stone, 2006) • Induction should not be a one-off activity • Raise awareness of cultural differences and offer support workshops, etc.

Some recommendations for action: Universities • Addressing marginalisation of overseas students as a institutional responsibility (Stone, 2006) • Induction should not be a one-off activity • Raise awareness of cultural differences and offer support workshops, etc.

Some recommendations for action: Departments • Recognise the value of attendance at classes and create more opportunities to attend • Named member of staff with pastoral responsibility for overseas Ph. D students • Plan office / lab space to avoid isolation • Assist with technical vocabulary, e. g. create photo-dictionaries of kit etc.

Some recommendations for action: Departments • Recognise the value of attendance at classes and create more opportunities to attend • Named member of staff with pastoral responsibility for overseas Ph. D students • Plan office / lab space to avoid isolation • Assist with technical vocabulary, e. g. create photo-dictionaries of kit etc.

Some recommendations for action: Supervisors • Have regular group meetings with a social element • Get to know Ph. D students in a simple, friendly way • Be aware of the types and levels of interaction in the group and take action to improve things where necessary

Some recommendations for action: Supervisors • Have regular group meetings with a social element • Get to know Ph. D students in a simple, friendly way • Be aware of the types and levels of interaction in the group and take action to improve things where necessary

Some recommendations for action: International offices • Showcase examples of successful interaction via national societies, induction events, “facebook” etc.

Some recommendations for action: International offices • Showcase examples of successful interaction via national societies, induction events, “facebook” etc.

Some recommendations for action All • Create more opportunities for language learning focussing on pragmatic competence (fluency vs correctness) • Consider how electronic communications can be employed to reduce isolation / marginalisation (Wisker, 2007)

Some recommendations for action All • Create more opportunities for language learning focussing on pragmatic competence (fluency vs correctness) • Consider how electronic communications can be employed to reduce isolation / marginalisation (Wisker, 2007)

References 1 • • • Acker, S. (1999). Students and Supervisors: The Ambiguous Relationship. Perspectives on the supervisory process in Britain and Canada. Review of Australian Research in Education, 5, 75 -94. Alpay, E. , & Walsh, E. (2008). A skills perception inventory for evaluating postgraduate transferable skills development. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. Campbell, R. A. (2003). Preparing the Next Generation of Scientists: The Social Process of Managing Students. Social Studies of Science, 33(6), 897 -928. • • • Carroll, J. , & Ryan, J. (2005). Teaching International Students: Improving learning for all. London: Routledge. Goode, J. (2007). Empowering or disempowering the international Ph. D. student? Constructions of the dependent and independent learner. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(5), 589 -603. Hockey, J. (1995). Getting too close: A problem and possible solution in social science Ph. D supervision. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(2), 199 - 210.

References 1 • • • Acker, S. (1999). Students and Supervisors: The Ambiguous Relationship. Perspectives on the supervisory process in Britain and Canada. Review of Australian Research in Education, 5, 75 -94. Alpay, E. , & Walsh, E. (2008). A skills perception inventory for evaluating postgraduate transferable skills development. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. Campbell, R. A. (2003). Preparing the Next Generation of Scientists: The Social Process of Managing Students. Social Studies of Science, 33(6), 897 -928. • • • Carroll, J. , & Ryan, J. (2005). Teaching International Students: Improving learning for all. London: Routledge. Goode, J. (2007). Empowering or disempowering the international Ph. D. student? Constructions of the dependent and independent learner. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(5), 589 -603. Hockey, J. (1995). Getting too close: A problem and possible solution in social science Ph. D supervision. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23(2), 199 - 210.

References 2 • • • Leonard, D. , Metcalfe, J. , Becker, R. , & Evans, J. (2006). Review of literature on the doctoral experience for the Higher Education Academy. Salter-Dvorak. 'Academic Tourism' or 'a truly multicultural community? ' Why international students need pragmatic training for British H. E. . Roberts, G. (2002). SET for success: Final Report of Sir Gareth Roberts' Review. HM treasury. Sastry, T. (2004). Postgraduate Education in the United Kingdom: Higher Education Policy Unit. Stone, N. (2006). Internationalising the Student Learning Experience: Possible Indicators. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10, 409 -413. • Trice, A. G. (2003). Faculty Perceptions of Graduate International Students: The Benefits and Challenges. Journal of Studies in International Education, 7(4), 379 -403. • Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • UKCOSA (2004): Broadening our horizons: International students in UK universities and colleges: Executive summary. http: //www. ukcosa. org. uk/abou t/pubs_research. php accessed June 08.

References 2 • • • Leonard, D. , Metcalfe, J. , Becker, R. , & Evans, J. (2006). Review of literature on the doctoral experience for the Higher Education Academy. Salter-Dvorak. 'Academic Tourism' or 'a truly multicultural community? ' Why international students need pragmatic training for British H. E. . Roberts, G. (2002). SET for success: Final Report of Sir Gareth Roberts' Review. HM treasury. Sastry, T. (2004). Postgraduate Education in the United Kingdom: Higher Education Policy Unit. Stone, N. (2006). Internationalising the Student Learning Experience: Possible Indicators. Journal of Studies in International Education, 10, 409 -413. • Trice, A. G. (2003). Faculty Perceptions of Graduate International Students: The Benefits and Challenges. Journal of Studies in International Education, 7(4), 379 -403. • Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. • UKCOSA (2004): Broadening our horizons: International students in UK universities and colleges: Executive summary. http: //www. ukcosa. org. uk/abou t/pubs_research. php accessed June 08.

References 3 • Wisker, G. , Robinson, G. , & Shacham, M. (2007) Postgraduate research success: communities of practice involving cohorts, guardian supervisors and online communities. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(3) • Wu, S. (2002). Filling the Pot or Lighting the Fire? Cultural Variations in Conceptions of Pedagogy. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(4), 387 -396.

References 3 • Wisker, G. , Robinson, G. , & Shacham, M. (2007) Postgraduate research success: communities of practice involving cohorts, guardian supervisors and online communities. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(3) • Wu, S. (2002). Filling the Pot or Lighting the Fire? Cultural Variations in Conceptions of Pedagogy. Teaching in Higher Education, 7(4), 387 -396.