The origins of five philosophical movements in the.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 31

The origins of five philosophical movements in the twentieth century Yesmakhan D. Kadyr S. Tursynbai B.

The origins of five philosophical movements in the twentieth century Yesmakhan D. Kadyr S. Tursynbai B.

The advent of Pragmatism G. E. Moore’s “Common Sense Analysis” as the precursor of the methodology of “Ordinary Language Analysis” in philosophy. Bertrand Russell and the origins of Logical Positivism: the logistic thesis of Principia Mathematica. Henri Bergson as a forerunner of the Existentialist movement in philosophy. Edmund Husserl and the foundations of the phenomenological movement

The advent of Pragmatism G. E. Moore’s “Common Sense Analysis” as the precursor of the methodology of “Ordinary Language Analysis” in philosophy. Bertrand Russell and the origins of Logical Positivism: the logistic thesis of Principia Mathematica. Henri Bergson as a forerunner of the Existentialist movement in philosophy. Edmund Husserl and the foundations of the phenomenological movement

The advent of Pragmatism

The advent of Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that began in the United States around 1870. Pragmatism rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. Instead, pragmatists consider thought an instrument or tool for prediction, problem solving and action. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are all best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes.

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that began in the United States around 1870. Pragmatism rejects the idea that the function of thought is to describe, represent, or mirror reality. Instead, pragmatists consider thought an instrument or tool for prediction, problem solving and action. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics—such as the nature of knowledge, language, concepts, meaning, belief, and science—are all best viewed in terms of their practical uses and successes.

Pragmatism as a philosophical movement began in the United States in the 1870 s. Its direction was determined by The Metaphysical Club members Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and Chauncey Wright, as well as John Dewey and George Herbert Mead. The first use in print of the name pragmatism was in 1898 by James, who credited Peirce with coining the term during the early 1870 s. James regarded Peirce's 1877– 8 "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series (including "The Fixation of Belief", 1877 and especially "How to Make Our Ideas Clear", 1878) as the foundation of pragmatism. Peirce in turn wrote in 1906 that Nicholas St. John Green had been instrumental by emphasizing the importance of applying Alexander Bain's definition of belief, which was "that upon which a man is prepared to act. " Peirce wrote that "from this definition, pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary; so that I am disposed to think of him as the grandfather of pragmatism. " John Shook has said, "Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricismas an alternative to rationalistic speculation. "

Pragmatism as a philosophical movement began in the United States in the 1870 s. Its direction was determined by The Metaphysical Club members Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and Chauncey Wright, as well as John Dewey and George Herbert Mead. The first use in print of the name pragmatism was in 1898 by James, who credited Peirce with coining the term during the early 1870 s. James regarded Peirce's 1877– 8 "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" series (including "The Fixation of Belief", 1877 and especially "How to Make Our Ideas Clear", 1878) as the foundation of pragmatism. Peirce in turn wrote in 1906 that Nicholas St. John Green had been instrumental by emphasizing the importance of applying Alexander Bain's definition of belief, which was "that upon which a man is prepared to act. " Peirce wrote that "from this definition, pragmatism is scarce more than a corollary; so that I am disposed to think of him as the grandfather of pragmatism. " John Shook has said, "Chauncey Wright also deserves considerable credit, for as both Peirce and James recall, it was Wright who demanded a phenomenalist and fallibilist empiricismas an alternative to rationalistic speculation. "

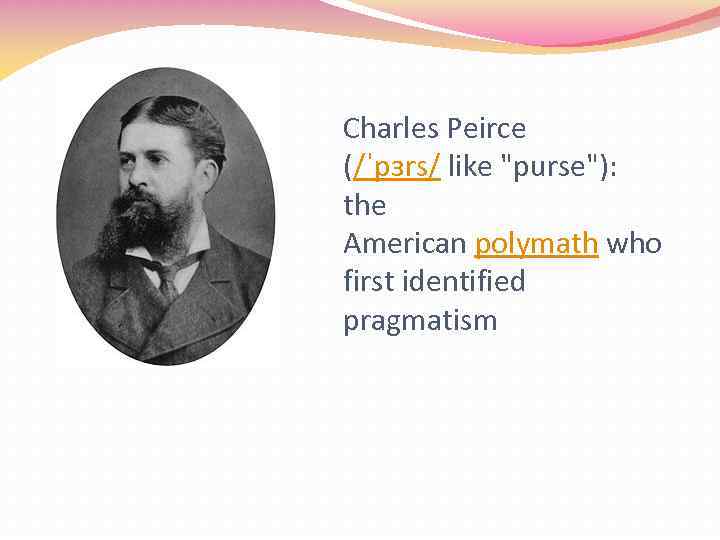

Charles Peirce (/ˈpɜrs/ like "purse"): the American polymath who first identified pragmatism

Charles Peirce (/ˈpɜrs/ like "purse"): the American polymath who first identified pragmatism

Inspiration for the various pragmatists included: Francis Bacon who coined the saying ipsa scientia potestas est ("knowledge itself is power") David Hume for his naturalistic account of knowledge and action Thomas Reid, for his direct realism Immanuel Kant, for his idealism and from whom Peirce derives the name "pragmatism" G. W. F. Hegel who introduced temporality into philosophy (Pinkard in Misak 2007) J. S. Mill for his nominalism and empiricism George Berkeley for his project to eliminate all unclear concepts from philosophy (Peirce 8: 33) Henri Bergson who influenced William James to renounce intellectualism and logical methods

Inspiration for the various pragmatists included: Francis Bacon who coined the saying ipsa scientia potestas est ("knowledge itself is power") David Hume for his naturalistic account of knowledge and action Thomas Reid, for his direct realism Immanuel Kant, for his idealism and from whom Peirce derives the name "pragmatism" G. W. F. Hegel who introduced temporality into philosophy (Pinkard in Misak 2007) J. S. Mill for his nominalism and empiricism George Berkeley for his project to eliminate all unclear concepts from philosophy (Peirce 8: 33) Henri Bergson who influenced William James to renounce intellectualism and logical methods

G. E. Moore’s “Common Sense Analysis” as the precursor of the methodology of “Ordinary Language Analysis” in philosophy.

G. E. Moore’s “Common Sense Analysis” as the precursor of the methodology of “Ordinary Language Analysis” in philosophy.

A Defence of Common Sense is an influential 1925 essay by philosopher G. E. Moore. In it, he attempts to refute absolute skepticism (or nihilism) by arguing that at least some of our established beliefs - facts - about the world are absolutely certain. Moore argues that these beliefs are common sense. In section one, he argues that he has certain knowledge of a number of truisms, such as "My body has existed continuously on or near the earth, at various distances from or in contact with other existing things, including other living human beings", "I am a human being", and "My body existed yesterday".

A Defence of Common Sense is an influential 1925 essay by philosopher G. E. Moore. In it, he attempts to refute absolute skepticism (or nihilism) by arguing that at least some of our established beliefs - facts - about the world are absolutely certain. Moore argues that these beliefs are common sense. In section one, he argues that he has certain knowledge of a number of truisms, such as "My body has existed continuously on or near the earth, at various distances from or in contact with other existing things, including other living human beings", "I am a human being", and "My body existed yesterday".

In section two, he argues that there is a distinction between mental facts and physical facts. He says there is no good reason to hold, as many philosophers of his time did, that every physical fact is logically dependent on mental facts, or that every physical fact is causally dependent on mental facts. An example of a physical fact is "The mantelpiece is at present nearer to this body than that bookcase is. " Mental facts include "I am conscious now" and "I am seeing something now. "

In section two, he argues that there is a distinction between mental facts and physical facts. He says there is no good reason to hold, as many philosophers of his time did, that every physical fact is logically dependent on mental facts, or that every physical fact is causally dependent on mental facts. An example of a physical fact is "The mantelpiece is at present nearer to this body than that bookcase is. " Mental facts include "I am conscious now" and "I am seeing something now. "

In section three, he affirms that not only does he not think there are good reasons for believing that all material objects were created by God, but neither does common sense give reasons to think that God exists at all or that there is an afterlife.

In section three, he affirms that not only does he not think there are good reasons for believing that all material objects were created by God, but neither does common sense give reasons to think that God exists at all or that there is an afterlife.

The fourth section considers how common sense propositions like "Here is my hand" are to be analysed. Moore considers three possibilities that occur to him for how what we know in these cases is related to what we know about our sense-data, i. e. what he sees when looking at his hand. Moore concludes that we are absolutely certain about the common sense belief, but that no analysis of the propositions has been offered that is even close to being certain.

The fourth section considers how common sense propositions like "Here is my hand" are to be analysed. Moore considers three possibilities that occur to him for how what we know in these cases is related to what we know about our sense-data, i. e. what he sees when looking at his hand. Moore concludes that we are absolutely certain about the common sense belief, but that no analysis of the propositions has been offered that is even close to being certain.

The fifth section is an examination of the problem of other minds. Moore argues that "there are other 'selves'", but explains why this question has baffled philosophers. In other words, the sense data that he perceives through his senses are facts about the interaction of the external world and himself, but he (and other philosophers) do not know how to analyze these interactions.

The fifth section is an examination of the problem of other minds. Moore argues that "there are other 'selves'", but explains why this question has baffled philosophers. In other words, the sense data that he perceives through his senses are facts about the interaction of the external world and himself, but he (and other philosophers) do not know how to analyze these interactions.

Ordinary language philosophy is a method of doing philosophy, rather than a set of doctrines. It is diverse in its methods and attitudes. It belongs to the general category of analytic philosophy, which has as its principal goal the analysis of concepts rather than the construction of a metaphysical system or the articulation of insights about the human condition. The method is to use features of certain words in ordinary or non-philosophical contexts as an aid to doing philosophy. The uses in non-philosophical contexts are taken to be paradigmatic; it is in them that meaning lives and moves and has its being. All ordinary language philosophers agree that classical philosophy suffered from an inadequate methodology that accounts for the lack of progress. But proponents of the method do not agree about whether philosophical problems are solved or dissolved; that is, they do not agree about whether philosophical problems are genuine problems for which there are solutions or whether they are merely pseudo-problems, which can at best be diagnosed.

Ordinary language philosophy is a method of doing philosophy, rather than a set of doctrines. It is diverse in its methods and attitudes. It belongs to the general category of analytic philosophy, which has as its principal goal the analysis of concepts rather than the construction of a metaphysical system or the articulation of insights about the human condition. The method is to use features of certain words in ordinary or non-philosophical contexts as an aid to doing philosophy. The uses in non-philosophical contexts are taken to be paradigmatic; it is in them that meaning lives and moves and has its being. All ordinary language philosophers agree that classical philosophy suffered from an inadequate methodology that accounts for the lack of progress. But proponents of the method do not agree about whether philosophical problems are solved or dissolved; that is, they do not agree about whether philosophical problems are genuine problems for which there are solutions or whether they are merely pseudo-problems, which can at best be diagnosed.

Bertrand Russell and the origins of Logical Positivism: the logistic thesis of Principia Mathematica.

Bertrand Russell and the origins of Logical Positivism: the logistic thesis of Principia Mathematica.

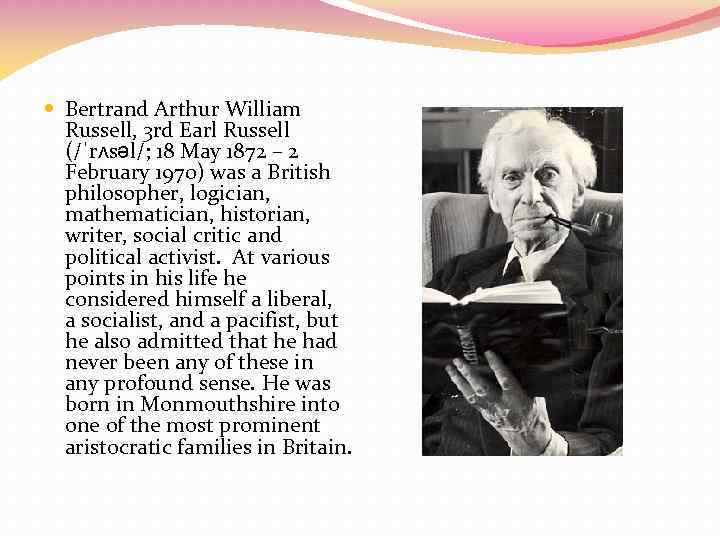

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3 rd Earl Russell (/ˈrʌsəl/; 18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, social critic and political activist. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these in any profound sense. He was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in Britain.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3 rd Earl Russell (/ˈrʌsəl/; 18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, social critic and political activist. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these in any profound sense. He was born in Monmouthshire into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in Britain.

In the early 20 th century, Russell led the British "revolt against idealism". He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob. Frege, colleague G. E. Moore, and his protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20 th century's premier logicians. With A. N. Whitehead he wrote Principia Mathematica, an attempt to create a logical basis for mathematics. His philosophical essay "On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy". His work has had a considerable influence on logic, mathematics, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science (see type theory and type system), and philosophy, especially the philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics.

In the early 20 th century, Russell led the British "revolt against idealism". He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob. Frege, colleague G. E. Moore, and his protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20 th century's premier logicians. With A. N. Whitehead he wrote Principia Mathematica, an attempt to create a logical basis for mathematics. His philosophical essay "On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy". His work has had a considerable influence on logic, mathematics, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science (see type theory and type system), and philosophy, especially the philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Russell was a prominent anti-war activist; he championed anti-imperialismand went to prison for his pacifism during World War I. Later, he campaigned against Adolf Hitler, thencriticised Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War, and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament. In 1950 Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought".

Russell was a prominent anti-war activist; he championed anti-imperialismand went to prison for his pacifism during World War I. Later, he campaigned against Adolf Hitler, thencriticised Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the involvement of the United States in the Vietnam War, and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament. In 1950 Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought".

Logical positivism (later referred to as logical empiricism, rational empiricism, or neo-positivism) is a school of philosophy that combines positivism— which states that the only authentic knowledge is scientific knowledge—with some king of logical analysis, which is similar, but not the same as logicism.

Logical positivism (later referred to as logical empiricism, rational empiricism, or neo-positivism) is a school of philosophy that combines positivism— which states that the only authentic knowledge is scientific knowledge—with some king of logical analysis, which is similar, but not the same as logicism.

Origins of logical positivism The logical positivists were very much influenced by and were great admirers of the early work of Wittgenstein (from the period of the Tractatus. Logico-Philosophicus). Wittgenstein himself was not a logical positivist, although he was on friendly terms with many members of the Vienna Circle while in Vienna, especially fellow aristocrat Moritz Schlick. Wittgenstein's influence is evident in the formulation of the verifiability principle. See for example Proposition 4. 024 of the Tractatus, where Wittgenstein asserts that we understand a proposition when we know what happens if it is true, and compare it with Schlick's assertion that "The definition of the circumstances under which a statement is true is perfectly 'equivalent' to the definition of its meaning". Wittgenstein also influenced the logical positivists' interpretation of probability.

Origins of logical positivism The logical positivists were very much influenced by and were great admirers of the early work of Wittgenstein (from the period of the Tractatus. Logico-Philosophicus). Wittgenstein himself was not a logical positivist, although he was on friendly terms with many members of the Vienna Circle while in Vienna, especially fellow aristocrat Moritz Schlick. Wittgenstein's influence is evident in the formulation of the verifiability principle. See for example Proposition 4. 024 of the Tractatus, where Wittgenstein asserts that we understand a proposition when we know what happens if it is true, and compare it with Schlick's assertion that "The definition of the circumstances under which a statement is true is perfectly 'equivalent' to the definition of its meaning". Wittgenstein also influenced the logical positivists' interpretation of probability.

Carnap was highly influenced by Bertrand Russell, with whom he had correspondence. The Aufbau is inspired by the Principia Mathematica.

Carnap was highly influenced by Bertrand Russell, with whom he had correspondence. The Aufbau is inspired by the Principia Mathematica.

The Principia Mathematica is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics, written by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. In 1927, it appeared in a second edition with an important Introduction To the Second Edition, an Appendix A that replaced ✸ 9 and an all-new Appendix C.

The Principia Mathematica is a three-volume work on the foundations of mathematics, written by Alfred North Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and published in 1910, 1912, and 1913. In 1927, it appeared in a second edition with an important Introduction To the Second Edition, an Appendix A that replaced ✸ 9 and an all-new Appendix C.

Henri Bergson as a forerunner of the Existentialist movement in philosophy.

Henri Bergson as a forerunner of the Existentialist movement in philosophy.

Existentialism is a philosophical movement that developed in continental Europe during the 1800’s and 1900’s. Most of the members are interested in the nature of existence or being, by which they usually mean human existence. Although the philosophers generally considered to be existentialists often disagree with each other and sometimes even resent being classified together, they have been grouped together because they share many problems, interests, and ideas. The most prominent existentialist thinkers of the 1900’s include the French writers Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sarte, and Gabriel Marcel and German philosophers Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger. The Russian religious and political thinker Nicolas Berdyaev and the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber were also famous existentialists. Existentialism is largely a revolt against traditional European philosophy which reached its climax during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s.

Existentialism is a philosophical movement that developed in continental Europe during the 1800’s and 1900’s. Most of the members are interested in the nature of existence or being, by which they usually mean human existence. Although the philosophers generally considered to be existentialists often disagree with each other and sometimes even resent being classified together, they have been grouped together because they share many problems, interests, and ideas. The most prominent existentialist thinkers of the 1900’s include the French writers Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sarte, and Gabriel Marcel and German philosophers Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger. The Russian religious and political thinker Nicolas Berdyaev and the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber were also famous existentialists. Existentialism is largely a revolt against traditional European philosophy which reached its climax during the late 1700’s and early 1800’s.

Bergson was born in the Rue Lamartine in Paris, not far from the Palais. Garnier (the old Paris opera house) in 1859. His father, the pianist Michał Bergson, was of a Polish Jewish family background (originally bearing the name Bereksohn). His mother, Katherine Levison, daughter of a Yorkshire doctor, was from an English and Irish Jewish background. The Bereksohns were a famous Jewish entrepreneurial family[3] of Polish descent. Henri Bergson's great-great -grandfather, Szmul. Jakubowicz. Sonnenberg, called Zbytkower, was a prominent banker and a protégé of Stanisław August Poniatowski, [4][5] King of Poland from 1764 to 1795.

Bergson was born in the Rue Lamartine in Paris, not far from the Palais. Garnier (the old Paris opera house) in 1859. His father, the pianist Michał Bergson, was of a Polish Jewish family background (originally bearing the name Bereksohn). His mother, Katherine Levison, daughter of a Yorkshire doctor, was from an English and Irish Jewish background. The Bereksohns were a famous Jewish entrepreneurial family[3] of Polish descent. Henri Bergson's great-great -grandfather, Szmul. Jakubowicz. Sonnenberg, called Zbytkower, was a prominent banker and a protégé of Stanisław August Poniatowski, [4][5] King of Poland from 1764 to 1795.

Henri Bergson's family lived in London for a few years after his birth, and he obtained an early familiarity with the English language from his mother. Before he was nine, his parents settled in France, Henri becoming a naturalized French citizen. Henri Bergson married Louise Neuberger, a cousin of Marcel Proust (1871– 1922), in 1891. (The novelist served as best man at Bergson's wedding. )[6] Henri and Louise Bergson had a daughter, Jeanne, born deaf in 1896. Bergson's sister, Mina Bergson (also known as Moina Mathers), married the English occult author Samuel Liddell Mac. Gregor Mathers, a founder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and the couple later relocated to Paris as well.

Henri Bergson's family lived in London for a few years after his birth, and he obtained an early familiarity with the English language from his mother. Before he was nine, his parents settled in France, Henri becoming a naturalized French citizen. Henri Bergson married Louise Neuberger, a cousin of Marcel Proust (1871– 1922), in 1891. (The novelist served as best man at Bergson's wedding. )[6] Henri and Louise Bergson had a daughter, Jeanne, born deaf in 1896. Bergson's sister, Mina Bergson (also known as Moina Mathers), married the English occult author Samuel Liddell Mac. Gregor Mathers, a founder of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and the couple later relocated to Paris as well.

Bergson lived the quiet life of a French professor, marked by the publication of his four principal works: in 1889, Time and Free Will (Essai sur les donnéesimmédiates de la conscience) in 1896, Matter and Memory (Matière et mémoire) in 1907, Creative Evolution (L'Evolutioncréatrice) in 1932, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion) In 1900 the College of France selected Bergson to a Chair of Greek and Latin Philosophy, which he held until 1904. He then replaced Gabriel Tarde in the Chair of Modern Philosophy, which he held until 1920. The public attended his open courses in large numbers.

Bergson lived the quiet life of a French professor, marked by the publication of his four principal works: in 1889, Time and Free Will (Essai sur les donnéesimmédiates de la conscience) in 1896, Matter and Memory (Matière et mémoire) in 1907, Creative Evolution (L'Evolutioncréatrice) in 1932, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (Les deux sources de la morale et de la religion) In 1900 the College of France selected Bergson to a Chair of Greek and Latin Philosophy, which he held until 1904. He then replaced Gabriel Tarde in the Chair of Modern Philosophy, which he held until 1920. The public attended his open courses in large numbers.

Edmund Husserl and the foundations of the phenomenological movement

Edmund Husserl and the foundations of the phenomenological movement

![Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (/ˈhʊsɛrl/; German: [ˈhʊsɐl]; 8 April 1859 – 27 April Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (/ˈhʊsɛrl/; German: [ˈhʊsɐl]; 8 April 1859 – 27 April](https://present5.com/presentation/182357951_437055888/image-29.jpg) Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (/ˈhʊsɛrl/; German: [ˈhʊsɐl]; 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938) was a Germanphilosopher who established the school of phenomenology. In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism and of psychologism in logic based on analyses of intentionality. In his mature work, he sought to develop a systematic foundational science based on the socalled phenomenological reduction. Arguing that transcendental consciousness sets the limits of all possible knowledge, Husserl redefined phenomenology as a transcendental-idealist philosophy. Husserl's thought profoundly influenced the landscape of twentieth century philosophy and he remains a notable figure in contemporary philosophy and beyond.

Edmund Gustav Albrecht Husserl (/ˈhʊsɛrl/; German: [ˈhʊsɐl]; 8 April 1859 – 27 April 1938) was a Germanphilosopher who established the school of phenomenology. In his early work, he elaborated critiques of historicism and of psychologism in logic based on analyses of intentionality. In his mature work, he sought to develop a systematic foundational science based on the socalled phenomenological reduction. Arguing that transcendental consciousness sets the limits of all possible knowledge, Husserl redefined phenomenology as a transcendental-idealist philosophy. Husserl's thought profoundly influenced the landscape of twentieth century philosophy and he remains a notable figure in contemporary philosophy and beyond.

Phenomenology (from Greek phainómenon "that which appears" and lógos "study") is the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness. As a philosophical movement it was founded in the early years of the 20 th century by Edmund Husserl and was later expanded upon by a circle of his followers at the universities of Göttingen and Munich in Germany. It then spread to France, the United States, and elsewhere, often in contexts far removed from Husserl's early work. [1] Phenomenology should not be considered as a unitary movement; rather, different authors share a common family resemblance but also with many significant differences. Accordingly, “A unique and final definition of phenomenology is dangerous and perhaps even paradoxical as it lacks a thematic focus. In fact, it is not a doctrine, nor a philosophical school, but rather a style of thought, a method, an open and ever-renewed experience having different results, and this may disorient anyone wishing to define the meaning of phenomenology”.

Phenomenology (from Greek phainómenon "that which appears" and lógos "study") is the philosophical study of the structures of experience and consciousness. As a philosophical movement it was founded in the early years of the 20 th century by Edmund Husserl and was later expanded upon by a circle of his followers at the universities of Göttingen and Munich in Germany. It then spread to France, the United States, and elsewhere, often in contexts far removed from Husserl's early work. [1] Phenomenology should not be considered as a unitary movement; rather, different authors share a common family resemblance but also with many significant differences. Accordingly, “A unique and final definition of phenomenology is dangerous and perhaps even paradoxical as it lacks a thematic focus. In fact, it is not a doctrine, nor a philosophical school, but rather a style of thought, a method, an open and ever-renewed experience having different results, and this may disorient anyone wishing to define the meaning of phenomenology”.

Phenomenology, in Husserl's conception, is primarily concerned with the systematic reflection on and study of the structures of consciousness and the phenomena that appear in acts of consciousness. This ontology (study of reality) can be clearly differentiated from the Cartesian method of analysis which sees the world as objects, sets of objects, and objects acting and reacting upon one another. Husserl's conception of phenomenology has been criticized and developed not only by himself but also by students, such as Edith Stein and Roman Ingarden, by hermeneutic philosophers, such as Martin Heidegger, by existentialists, such as Nicolai Hartmann, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, and by other philosophers, such as Max Scheler, Paul Ricoeur, Jean-Luc Marion, Emmanuel Lévinas, and sociologists Alfred Schütz and Eric Voegelin.

Phenomenology, in Husserl's conception, is primarily concerned with the systematic reflection on and study of the structures of consciousness and the phenomena that appear in acts of consciousness. This ontology (study of reality) can be clearly differentiated from the Cartesian method of analysis which sees the world as objects, sets of objects, and objects acting and reacting upon one another. Husserl's conception of phenomenology has been criticized and developed not only by himself but also by students, such as Edith Stein and Roman Ingarden, by hermeneutic philosophers, such as Martin Heidegger, by existentialists, such as Nicolai Hartmann, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, and by other philosophers, such as Max Scheler, Paul Ricoeur, Jean-Luc Marion, Emmanuel Lévinas, and sociologists Alfred Schütz and Eric Voegelin.