c2c0d862ccaf37415a93926cf8547961.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 28

® The Open Economy Revisited: The Mundell-Fleming Model and the Exchange-Rate Regime A Power. Point Tutorial To Accompany MACROECONOMICS, 8 th Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Tutorial written by: Mannig J. Simidian B. A. in Economics with Distinction, Duke University 1 M. P. A. , Harvard University Kennedy School of Government M. B. A. , Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management Chapter Twelve

® The Open Economy Revisited: The Mundell-Fleming Model and the Exchange-Rate Regime A Power. Point Tutorial To Accompany MACROECONOMICS, 8 th Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Tutorial written by: Mannig J. Simidian B. A. in Economics with Distinction, Duke University 1 M. P. A. , Harvard University Kennedy School of Government M. B. A. , Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Sloan School of Management Chapter Twelve

The issues of open-economy macroeconomics have been very much in the news in recent years. At various European nations, most notably Greece, experienced severe financial difficulties, many observers wondered whether it was wise for much of the continent to adopt a common currency—the most extreme form of a fixedexchange rate. If each nation had its own currency, monetary policy and the exchange rate could have more easily adjusted to the needs of each nation. Many American policy makers were objecting that China did not allow the value of its currency to float freely against the U. S. dollar. they agreed that China kept its currency artificially cheap, making its goods more competitive on world markets. The Mundell-Fleming model a useful starting point for understanding and evaluating these often heated international policy debates. Chapter Twelve 2

The issues of open-economy macroeconomics have been very much in the news in recent years. At various European nations, most notably Greece, experienced severe financial difficulties, many observers wondered whether it was wise for much of the continent to adopt a common currency—the most extreme form of a fixedexchange rate. If each nation had its own currency, monetary policy and the exchange rate could have more easily adjusted to the needs of each nation. Many American policy makers were objecting that China did not allow the value of its currency to float freely against the U. S. dollar. they agreed that China kept its currency artificially cheap, making its goods more competitive on world markets. The Mundell-Fleming model a useful starting point for understanding and evaluating these often heated international policy debates. Chapter Twelve 2

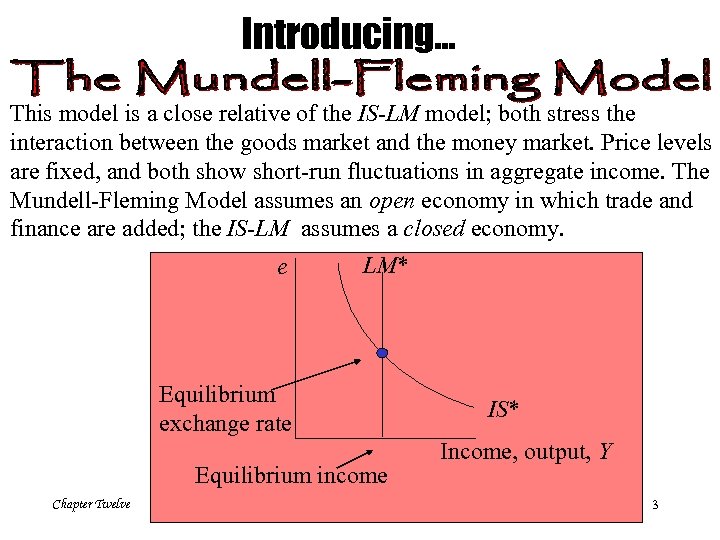

Introducing… This model is a close relative of the IS-LM model; both stress the interaction between the goods market and the money market. Price levels are fixed, and both show short-run fluctuations in aggregate income. The Mundell-Fleming Model assumes an open economy in which trade and finance are added; the IS-LM assumes a closed economy. e LM* Equilibrium exchange rate Equilibrium income Chapter Twelve IS* Income, output, Y 3

Introducing… This model is a close relative of the IS-LM model; both stress the interaction between the goods market and the money market. Price levels are fixed, and both show short-run fluctuations in aggregate income. The Mundell-Fleming Model assumes an open economy in which trade and finance are added; the IS-LM assumes a closed economy. e LM* Equilibrium exchange rate Equilibrium income Chapter Twelve IS* Income, output, Y 3

This model, often described as “the dominant policy paradigm for studying open-economy monetary and fiscal policy, ” makes one important and extreme assumption: the economy being studied is a small open economy and there is perfect capital mobility, meaning that it can borrow or lend as much as it wants in world financial markets, and therefore, the economy’s interest rate is controlled by the world interest rate, mathematically denoted as r = r*. One key lesson about this model is that the behavior of an economy depends on the exchange rate regime it adopts—floating or fixed. This model will help answer the question of which exchange rate regime should a nation adopt? Chapter Twelve 4

This model, often described as “the dominant policy paradigm for studying open-economy monetary and fiscal policy, ” makes one important and extreme assumption: the economy being studied is a small open economy and there is perfect capital mobility, meaning that it can borrow or lend as much as it wants in world financial markets, and therefore, the economy’s interest rate is controlled by the world interest rate, mathematically denoted as r = r*. One key lesson about this model is that the behavior of an economy depends on the exchange rate regime it adopts—floating or fixed. This model will help answer the question of which exchange rate regime should a nation adopt? Chapter Twelve 4

Under a system of floating exchange rates, the exchange rate is set by market forces and is allowed to fluctuate in response to changing economic conditions. The exchange rate e, adjusts to achieve simultaneous equilibrium in the goods market and the money market. When something changes that equilibrium, the exchange rate is allowed to adjust to a new rate. Chapter Twelve 5

Under a system of floating exchange rates, the exchange rate is set by market forces and is allowed to fluctuate in response to changing economic conditions. The exchange rate e, adjusts to achieve simultaneous equilibrium in the goods market and the money market. When something changes that equilibrium, the exchange rate is allowed to adjust to a new rate. Chapter Twelve 5

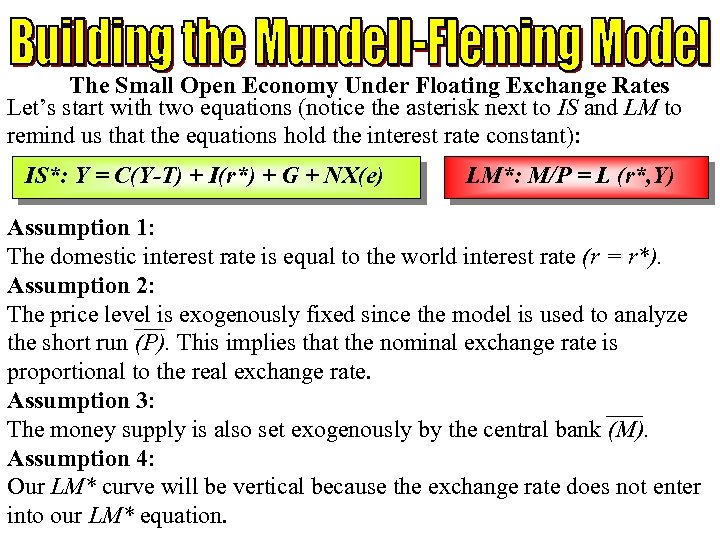

The Small Open Economy Under Floating Exchange Rates Let’s start with two equations (notice the asterisk next to IS and LM to remind us that the equations hold the interest rate constant): IS*: Y = C(Y-T) + I(r*) + G + NX(e) LM*: M/P = L (r*, Y) Assumption 1: The domestic interest rate is equal to the world interest rate (r = r*). Assumption 2: The price level is exogenously fixed since the model is used to analyze the short run (P). This implies that the nominal exchange rate is proportional to the real exchange rate. Assumption 3: The money supply is also set exogenously by the central bank (M). Assumption 4: Our LM* curve will be vertical because the exchange rate does not enter Chapter Twelve 6 into our LM* equation.

The Small Open Economy Under Floating Exchange Rates Let’s start with two equations (notice the asterisk next to IS and LM to remind us that the equations hold the interest rate constant): IS*: Y = C(Y-T) + I(r*) + G + NX(e) LM*: M/P = L (r*, Y) Assumption 1: The domestic interest rate is equal to the world interest rate (r = r*). Assumption 2: The price level is exogenously fixed since the model is used to analyze the short run (P). This implies that the nominal exchange rate is proportional to the real exchange rate. Assumption 3: The money supply is also set exogenously by the central bank (M). Assumption 4: Our LM* curve will be vertical because the exchange rate does not enter Chapter Twelve 6 into our LM* equation.

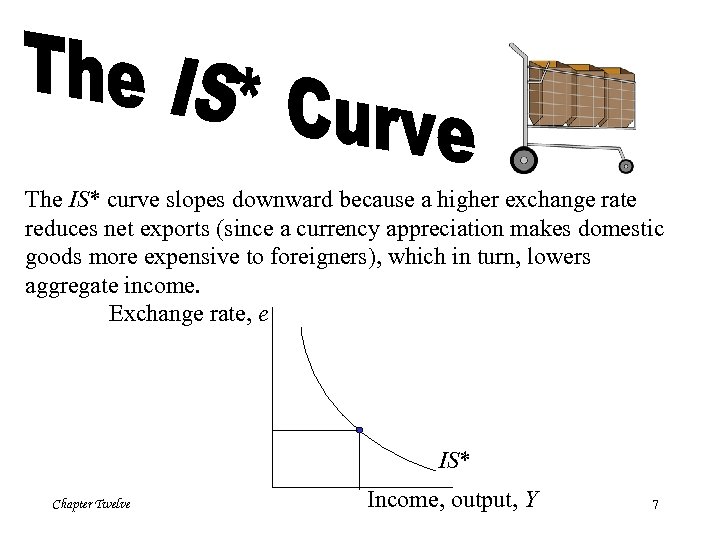

The IS* curve slopes downward because a higher exchange rate reduces net exports (since a currency appreciation makes domestic goods more expensive to foreigners), which in turn, lowers aggregate income. Exchange rate, e IS* Chapter Twelve Income, output, Y 7

The IS* curve slopes downward because a higher exchange rate reduces net exports (since a currency appreciation makes domestic goods more expensive to foreigners), which in turn, lowers aggregate income. Exchange rate, e IS* Chapter Twelve Income, output, Y 7

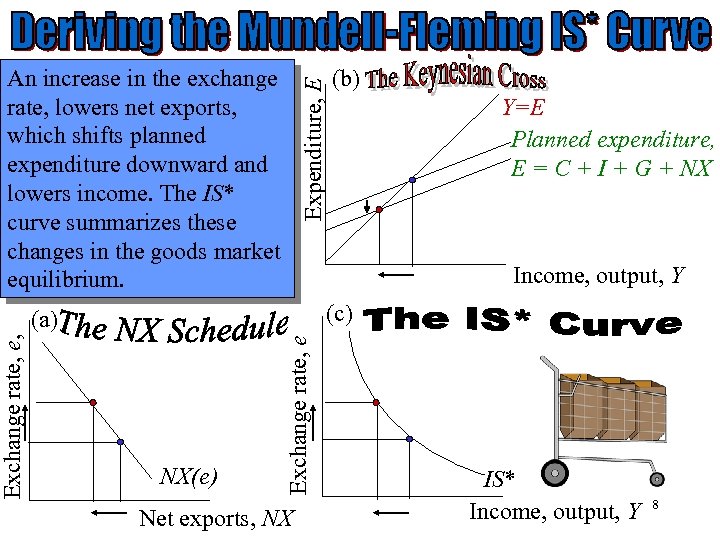

Expenditure, E Y=E Planned expenditure, E = C + I + G + NX (c) (a) NX(e) Chapter Twelve (b) Income, output, Y Exchange rate, e, An increase in the exchange rate, lowers net exports, which shifts planned expenditure downward and lowers income. The IS* curve summarizes these changes in the goods market equilibrium. Net exports, NX IS* Income, output, Y 8

Expenditure, E Y=E Planned expenditure, E = C + I + G + NX (c) (a) NX(e) Chapter Twelve (b) Income, output, Y Exchange rate, e, An increase in the exchange rate, lowers net exports, which shifts planned expenditure downward and lowers income. The IS* curve summarizes these changes in the goods market equilibrium. Net exports, NX IS* Income, output, Y 8

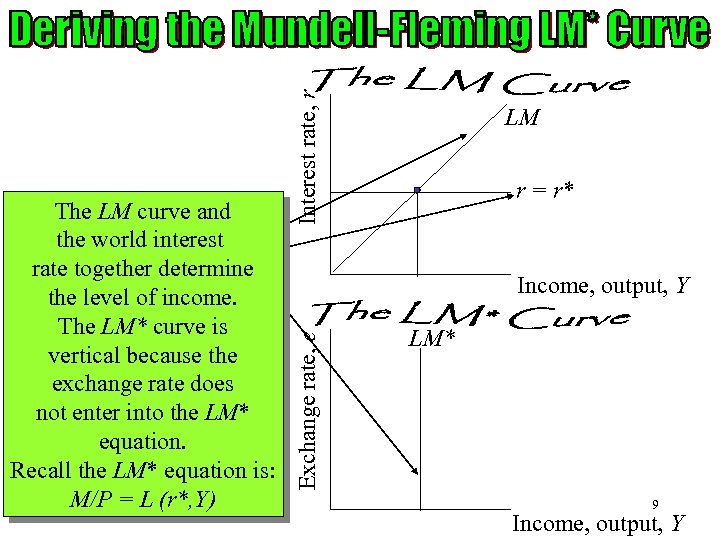

Interest rate, r r = r* Income, output, Y Exchange rate, e The LM curve and the world interest rate together determine the level of income. The LM* curve is vertical because the exchange rate does not enter into the LM* equation. Recall the LM* equation is: M/P = Chapter Twelve L (r*, Y) LM LM* 9 Income, output, Y

Interest rate, r r = r* Income, output, Y Exchange rate, e The LM curve and the world interest rate together determine the level of income. The LM* curve is vertical because the exchange rate does not enter into the LM* equation. Recall the LM* equation is: M/P = Chapter Twelve L (r*, Y) LM LM* 9 Income, output, Y

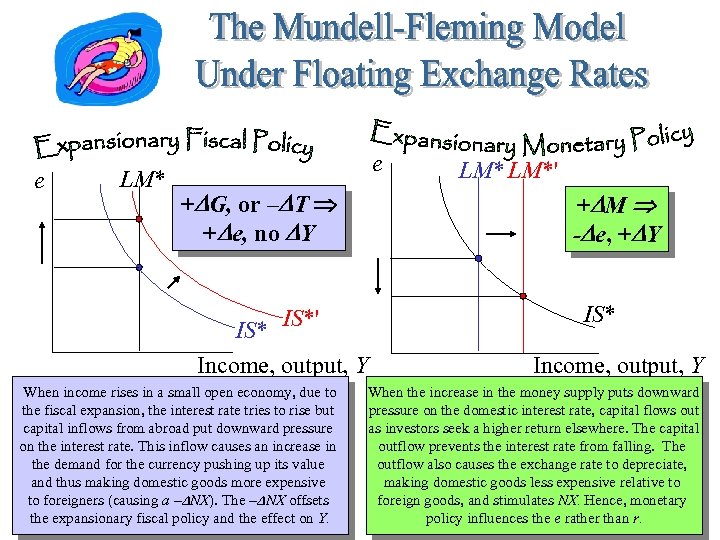

e LM* e +DG, or –DT +De, no DY +DM -De, +DY IS*' Income, output, Y When income rises in a small open economy, due to the fiscal expansion, the interest rate tries to rise but capital inflows from abroad put downward pressure on the interest rate. This inflow causes an increase in the demand for the currency pushing up its value and thus making domestic goods more expensive to foreigners (causing a –DNX). The –DNX offsets Chapter Twelve the expansionary fiscal policy and the effect on Y. LM*' IS* Income, output, Y When the increase in the money supply puts downward pressure on the domestic interest rate, capital flows out as investors seek a higher return elsewhere. The capital outflow prevents the interest rate from falling. The outflow also causes the exchange rate to depreciate, making domestic goods less expensive relative to foreign goods, and stimulates NX. Hence, monetary 10 policy influences the e rather than r.

e LM* e +DG, or –DT +De, no DY +DM -De, +DY IS*' Income, output, Y When income rises in a small open economy, due to the fiscal expansion, the interest rate tries to rise but capital inflows from abroad put downward pressure on the interest rate. This inflow causes an increase in the demand for the currency pushing up its value and thus making domestic goods more expensive to foreigners (causing a –DNX). The –DNX offsets Chapter Twelve the expansionary fiscal policy and the effect on Y. LM*' IS* Income, output, Y When the increase in the money supply puts downward pressure on the domestic interest rate, capital flows out as investors seek a higher return elsewhere. The capital outflow prevents the interest rate from falling. The outflow also causes the exchange rate to depreciate, making domestic goods less expensive relative to foreign goods, and stimulates NX. Hence, monetary 10 policy influences the e rather than r.

Fixed Exchange Rates Under a fixed exchange rate, the central bank announces a value for the exchange rate and stands ready to buy and sell the domestic currency at a predetermined price to keep the exchange rate at its announced level. Fixed exchange rates require a commitment of a central bank to allow the money supply to adjust to whatever level will ensure that the equilibrium exchange rate in the market foreigncurrency exchange equals the announced exchange rate. Most recently, China fixed the value of its currency against the U. S. dollar, which has resulted in a lot of tension between the two nations. It is important to realize that this exchange-rate system fixes the nominal exchange rate. Whether it fixes the real exchange rate depends on the time horizon. Chapter Twelve 11

Fixed Exchange Rates Under a fixed exchange rate, the central bank announces a value for the exchange rate and stands ready to buy and sell the domestic currency at a predetermined price to keep the exchange rate at its announced level. Fixed exchange rates require a commitment of a central bank to allow the money supply to adjust to whatever level will ensure that the equilibrium exchange rate in the market foreigncurrency exchange equals the announced exchange rate. Most recently, China fixed the value of its currency against the U. S. dollar, which has resulted in a lot of tension between the two nations. It is important to realize that this exchange-rate system fixes the nominal exchange rate. Whether it fixes the real exchange rate depends on the time horizon. Chapter Twelve 11

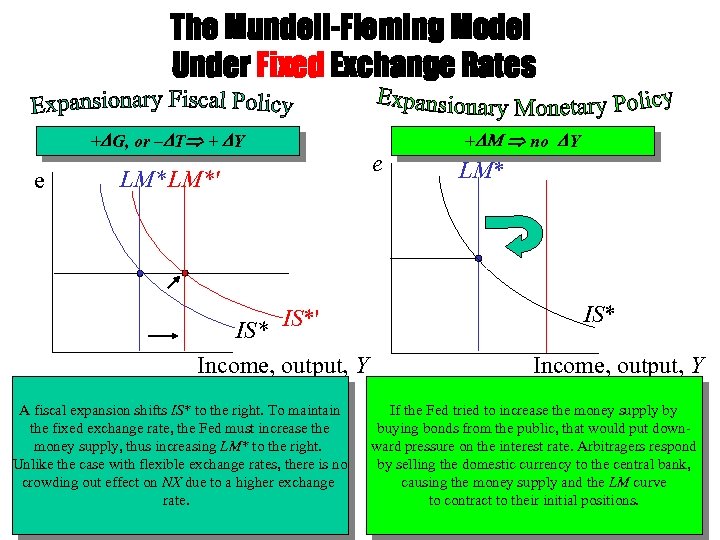

The Mundell-Fleming Model Under Fixed Exchange Rates +DG, or –DT + DY e LM*' IS*' Income, output, Y A fiscal expansion shifts IS* to the right. To maintain the fixed exchange rate, the Fed must increase the money supply, thus increasing LM* to the right. Unlike the case with flexible exchange rates, there is no crowding out effect on NX due to a higher exchange rate. Chapter Twelve e +DM no DY LM* IS* Income, output, Y If the Fed tried to increase the money supply by buying bonds from the public, that would put downward pressure on the interest rate. Arbitragers respond by selling the domestic currency to the central bank, causing the money supply and the LM curve to contract to their initial positions. 12

The Mundell-Fleming Model Under Fixed Exchange Rates +DG, or –DT + DY e LM*' IS*' Income, output, Y A fiscal expansion shifts IS* to the right. To maintain the fixed exchange rate, the Fed must increase the money supply, thus increasing LM* to the right. Unlike the case with flexible exchange rates, there is no crowding out effect on NX due to a higher exchange rate. Chapter Twelve e +DM no DY LM* IS* Income, output, Y If the Fed tried to increase the money supply by buying bonds from the public, that would put downward pressure on the interest rate. Arbitragers respond by selling the domestic currency to the central bank, causing the money supply and the LM curve to contract to their initial positions. 12

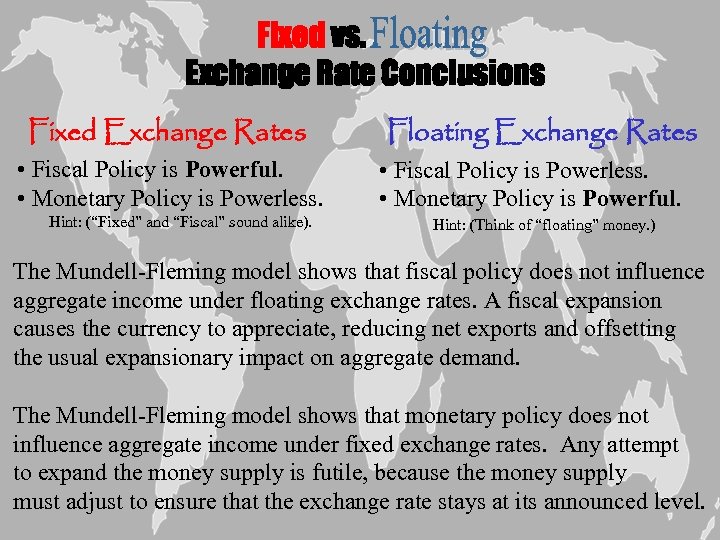

Fixed vs. Exchange Rate Conclusions Fixed Exchange Rates • Fiscal Policy is Powerful. • Monetary Policy is Powerless. Hint: (“Fixed” and “Fiscal” sound alike). Floating Exchange Rates • Fiscal Policy is Powerless. • Monetary Policy is Powerful. Hint: (Think of “floating” money. ) The Mundell-Fleming model shows that fiscal policy does not influence aggregate income under floating exchange rates. A fiscal expansion causes the currency to appreciate, reducing net exports and offsetting the usual expansionary impact on aggregate demand. The Mundell-Fleming model shows that monetary policy does not influence aggregate income under fixed exchange rates. Any attempt to expand the money supply is futile, because the money supply Chapter Twelve must adjust to ensure that the exchange rate stays at its announced 13 level.

Fixed vs. Exchange Rate Conclusions Fixed Exchange Rates • Fiscal Policy is Powerful. • Monetary Policy is Powerless. Hint: (“Fixed” and “Fiscal” sound alike). Floating Exchange Rates • Fiscal Policy is Powerless. • Monetary Policy is Powerful. Hint: (Think of “floating” money. ) The Mundell-Fleming model shows that fiscal policy does not influence aggregate income under floating exchange rates. A fiscal expansion causes the currency to appreciate, reducing net exports and offsetting the usual expansionary impact on aggregate demand. The Mundell-Fleming model shows that monetary policy does not influence aggregate income under fixed exchange rates. Any attempt to expand the money supply is futile, because the money supply Chapter Twelve must adjust to ensure that the exchange rate stays at its announced 13 level.

Policy in the Mundell-Fleming Model: A Summary The Mundell-Fleming model shows that the effect of almost any economic policy on a small open economy depends on whether the exchange rate is floating or fixed. The Mundell-Fleming model shows that the power of monetary and fiscal policy to influence aggregate demand depends on the exchange rate regime. Chapter Twelve 14

Policy in the Mundell-Fleming Model: A Summary The Mundell-Fleming model shows that the effect of almost any economic policy on a small open economy depends on whether the exchange rate is floating or fixed. The Mundell-Fleming model shows that the power of monetary and fiscal policy to influence aggregate demand depends on the exchange rate regime. Chapter Twelve 14

A country with fixed exchange rates can, however, conduct a type of monetary policy by deciding to change the level at which the exchange rate is fixed. A reduction in the official value of the currency is called a devaluation, and an increase in the value is called a revaluation. Chapter Twelve 15

A country with fixed exchange rates can, however, conduct a type of monetary policy by deciding to change the level at which the exchange rate is fixed. A reduction in the official value of the currency is called a devaluation, and an increase in the value is called a revaluation. Chapter Twelve 15

What if the domestic interest rate were above the world interest rate? The higher return will attract funds from the rest of the world, driving the domestic interest rate back down. And, if the domestic interest rate were below the world interest rate, r*, domestic residents would lend abroad to earn a higher return, driving the domestic interest rate back up. In the end, the domestic interest rate would equal the world interest rate. Chapter Twelve 16

What if the domestic interest rate were above the world interest rate? The higher return will attract funds from the rest of the world, driving the domestic interest rate back down. And, if the domestic interest rate were below the world interest rate, r*, domestic residents would lend abroad to earn a higher return, driving the domestic interest rate back up. In the end, the domestic interest rate would equal the world interest rate. Chapter Twelve 16

Why doesn’t this logic always apply? There are two reasons why interest rates differ across countries: 1) Country Risk: when investors buy U. S. government bonds, or make loans to U. S. corporations, they are fairly confident that they will be repaid with interest. By contrast, in some less developed countries, it is plausible to fear that political upheaval may lead to a default on loan repayments. Borrowers in such countries often have to pay higher interest rates to compensate lenders for this risk. 2) Exchange Rate Expectations: suppose that people expect the French franc to fall in value relative to the U. S. dollar. Then loans made in francs will be repaid in a less valuable currency than loans made in dollars. To compensate for the expected fall in the French currency, the interest rate Chapter will in France. Twelve be higher than the interest rate in the United States. 17

Why doesn’t this logic always apply? There are two reasons why interest rates differ across countries: 1) Country Risk: when investors buy U. S. government bonds, or make loans to U. S. corporations, they are fairly confident that they will be repaid with interest. By contrast, in some less developed countries, it is plausible to fear that political upheaval may lead to a default on loan repayments. Borrowers in such countries often have to pay higher interest rates to compensate lenders for this risk. 2) Exchange Rate Expectations: suppose that people expect the French franc to fall in value relative to the U. S. dollar. Then loans made in francs will be repaid in a less valuable currency than loans made in dollars. To compensate for the expected fall in the French currency, the interest rate Chapter will in France. Twelve be higher than the interest rate in the United States. 17

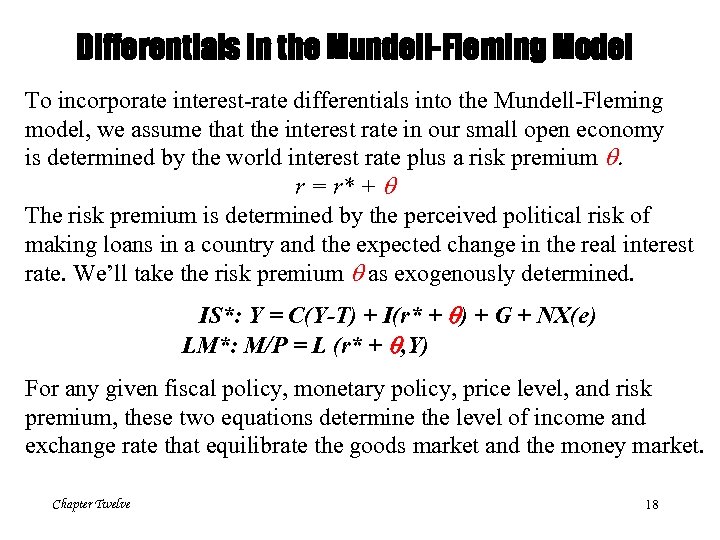

Differentials in the Mundell-Fleming Model To incorporate interest-rate differentials into the Mundell-Fleming model, we assume that the interest rate in our small open economy is determined by the world interest rate plus a risk premium q. r = r* + q The risk premium is determined by the perceived political risk of making loans in a country and the expected change in the real interest rate. We’ll take the risk premium q as exogenously determined. IS*: Y = C(Y-T) + I(r* + q) + G + NX(e) LM*: M/P = L (r* + q, Y) For any given fiscal policy, monetary policy, price level, and risk premium, these two equations determine the level of income and exchange rate that equilibrate the goods market and the money market. Chapter Twelve 18

Differentials in the Mundell-Fleming Model To incorporate interest-rate differentials into the Mundell-Fleming model, we assume that the interest rate in our small open economy is determined by the world interest rate plus a risk premium q. r = r* + q The risk premium is determined by the perceived political risk of making loans in a country and the expected change in the real interest rate. We’ll take the risk premium q as exogenously determined. IS*: Y = C(Y-T) + I(r* + q) + G + NX(e) LM*: M/P = L (r* + q, Y) For any given fiscal policy, monetary policy, price level, and risk premium, these two equations determine the level of income and exchange rate that equilibrate the goods market and the money market. Chapter Twelve 18

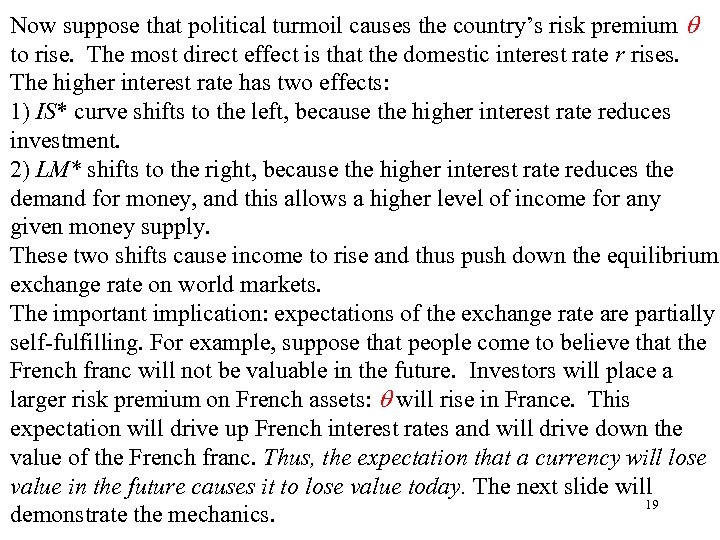

Now suppose that political turmoil causes the country’s risk premium q to rise. The most direct effect is that the domestic interest rate r rises. The higher interest rate has two effects: 1) IS* curve shifts to the left, because the higher interest rate reduces investment. 2) LM* shifts to the right, because the higher interest rate reduces the demand for money, and this allows a higher level of income for any given money supply. These two shifts cause income to rise and thus push down the equilibrium exchange rate on world markets. The important implication: expectations of the exchange rate are partially self-fulfilling. For example, suppose that people come to believe that the French franc will not be valuable in the future. Investors will place a larger risk premium on French assets: q will rise in France. This expectation will drive up French interest rates and will drive down the value of the French franc. Thus, the expectation that a currency will lose value in the future causes it to lose value today. The next slide will Chapter Twelve 19 demonstrate the mechanics.

Now suppose that political turmoil causes the country’s risk premium q to rise. The most direct effect is that the domestic interest rate r rises. The higher interest rate has two effects: 1) IS* curve shifts to the left, because the higher interest rate reduces investment. 2) LM* shifts to the right, because the higher interest rate reduces the demand for money, and this allows a higher level of income for any given money supply. These two shifts cause income to rise and thus push down the equilibrium exchange rate on world markets. The important implication: expectations of the exchange rate are partially self-fulfilling. For example, suppose that people come to believe that the French franc will not be valuable in the future. Investors will place a larger risk premium on French assets: q will rise in France. This expectation will drive up French interest rates and will drive down the value of the French franc. Thus, the expectation that a currency will lose value in the future causes it to lose value today. The next slide will Chapter Twelve 19 demonstrate the mechanics.

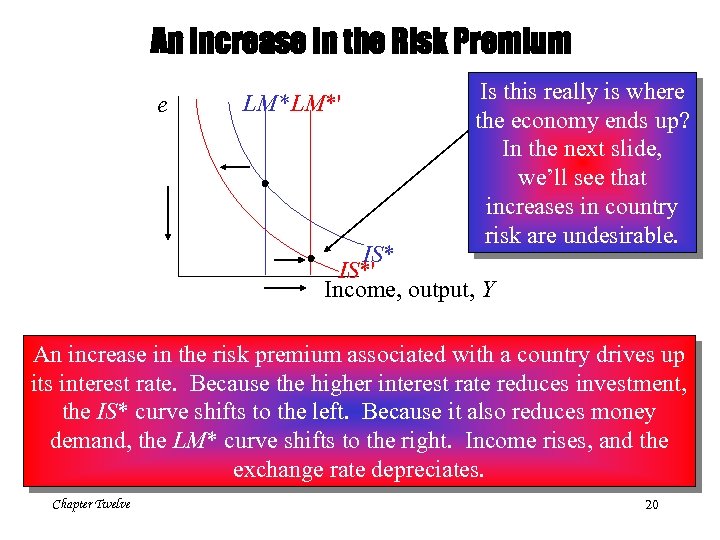

An Increase in the Risk Premium e LM*' Is this really is where the economy ends up? In the next slide, we’ll see that increases in country risk are undesirable. IS*' Income, output, Y An increase in the risk premium associated with a country drives up its interest rate. Because the higher interest rate reduces investment, the IS* curve shifts to the left. Because it also reduces money demand, the LM* curve shifts to the right. Income rises, and the exchange rate depreciates. Chapter Twelve 20

An Increase in the Risk Premium e LM*' Is this really is where the economy ends up? In the next slide, we’ll see that increases in country risk are undesirable. IS*' Income, output, Y An increase in the risk premium associated with a country drives up its interest rate. Because the higher interest rate reduces investment, the IS* curve shifts to the left. Because it also reduces money demand, the LM* curve shifts to the right. Income rises, and the exchange rate depreciates. Chapter Twelve 20

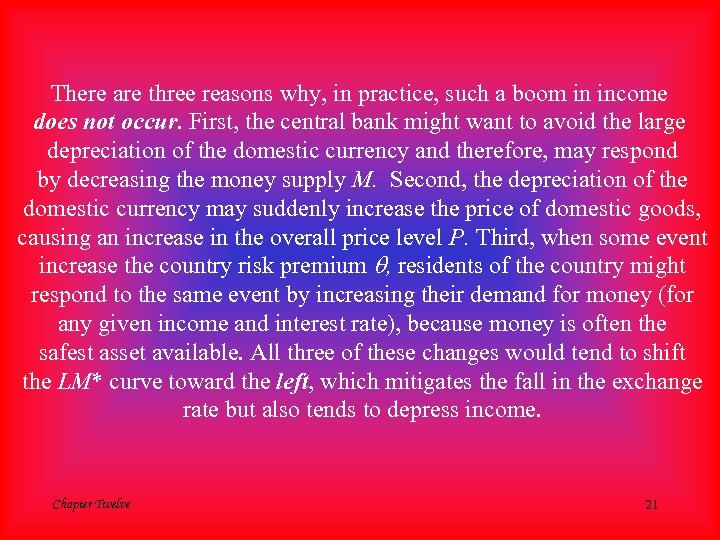

There are three reasons why, in practice, such a boom in income does not occur. First, the central bank might want to avoid the large depreciation of the domestic currency and therefore, may respond by decreasing the money supply M. Second, the depreciation of the domestic currency may suddenly increase the price of domestic goods, causing an increase in the overall price level P. Third, when some event increase the country risk premium q, residents of the country might respond to the same event by increasing their demand for money (for any given income and interest rate), because money is often the safest asset available. All three of these changes would tend to shift the LM* curve toward the left, which mitigates the fall in the exchange rate but also tends to depress income. Chapter Twelve 21

There are three reasons why, in practice, such a boom in income does not occur. First, the central bank might want to avoid the large depreciation of the domestic currency and therefore, may respond by decreasing the money supply M. Second, the depreciation of the domestic currency may suddenly increase the price of domestic goods, causing an increase in the overall price level P. Third, when some event increase the country risk premium q, residents of the country might respond to the same event by increasing their demand for money (for any given income and interest rate), because money is often the safest asset available. All three of these changes would tend to shift the LM* curve toward the left, which mitigates the fall in the exchange rate but also tends to depress income. Chapter Twelve 21

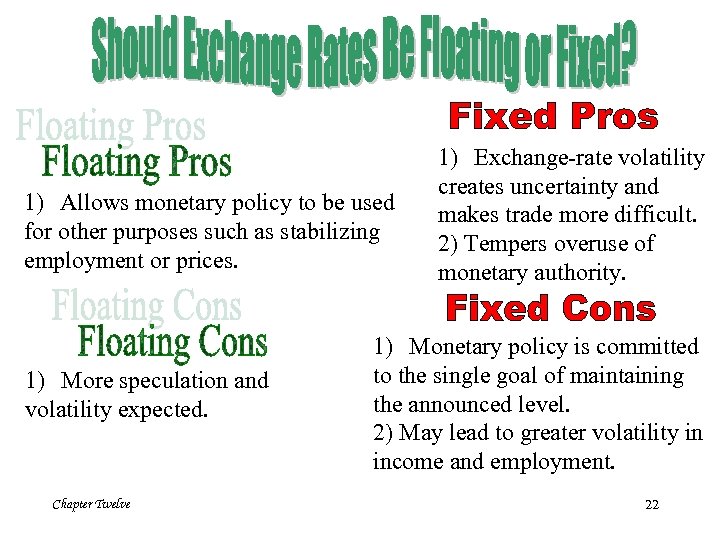

1) Allows monetary policy to be used for other purposes such as stabilizing employment or prices. 1) More speculation and volatility expected. Chapter Twelve 1) Exchange-rate volatility creates uncertainty and makes trade more difficult. 2) Tempers overuse of monetary authority. 1) Monetary policy is committed to the single goal of maintaining the announced level. 2) May lead to greater volatility in income and employment. 22

1) Allows monetary policy to be used for other purposes such as stabilizing employment or prices. 1) More speculation and volatility expected. Chapter Twelve 1) Exchange-rate volatility creates uncertainty and makes trade more difficult. 2) Tempers overuse of monetary authority. 1) Monetary policy is committed to the single goal of maintaining the announced level. 2) May lead to greater volatility in income and employment. 22

A speculative attack is a case where a change in investors’ perceptions makes a fixed rate untenable. To avoid these kinds of attacks, some economists suggest the use of a currency board, an arrangement by which the central bank holds enough foreign currency to back each unit of the domestic currency. The next for a nation is to consider dollarization, a plan in which the domestic currency is abandoned and the U. S. dollar is used instead. Chapter Twelve 23

A speculative attack is a case where a change in investors’ perceptions makes a fixed rate untenable. To avoid these kinds of attacks, some economists suggest the use of a currency board, an arrangement by which the central bank holds enough foreign currency to back each unit of the domestic currency. The next for a nation is to consider dollarization, a plan in which the domestic currency is abandoned and the U. S. dollar is used instead. Chapter Twelve 23

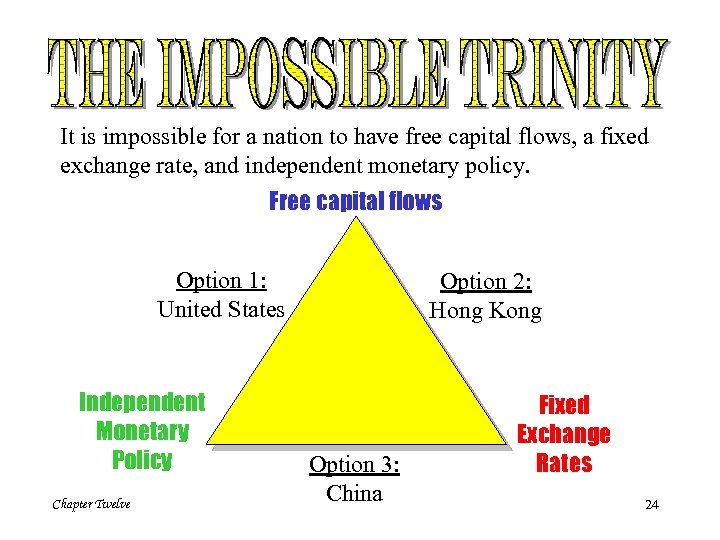

It is impossible for a nation to have free capital flows, a fixed exchange rate, and independent monetary policy. Free capital flows Option 1: United States Independent Monetary Policy Chapter Twelve Option 2: Hong Kong Option 3: China Fixed Exchange Rates 24

It is impossible for a nation to have free capital flows, a fixed exchange rate, and independent monetary policy. Free capital flows Option 1: United States Independent Monetary Policy Chapter Twelve Option 2: Hong Kong Option 3: China Fixed Exchange Rates 24

China’s Currency Situation By January 2009, the exchange rate had moved to 6. 84 yuan per dollar– a 21% appreciation of the yuan. Despite this large change in the exchange rate, China’s critics continued to complain about that nation’s intervention in foreign-exchange markets. In January 2009, the new Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said, “President Obama– backed by the conclusions of a broad range of economists—believes that China is manipulating its currency. So, President Obama had pledged to use aggressively all diplomatic avenues open to him to seek change in China’s currency practices. Currently, China no longer uses a completely fixed exchange rate. Chapter Twelve 25

China’s Currency Situation By January 2009, the exchange rate had moved to 6. 84 yuan per dollar– a 21% appreciation of the yuan. Despite this large change in the exchange rate, China’s critics continued to complain about that nation’s intervention in foreign-exchange markets. In January 2009, the new Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said, “President Obama– backed by the conclusions of a broad range of economists—believes that China is manipulating its currency. So, President Obama had pledged to use aggressively all diplomatic avenues open to him to seek change in China’s currency practices. Currently, China no longer uses a completely fixed exchange rate. Chapter Twelve 25

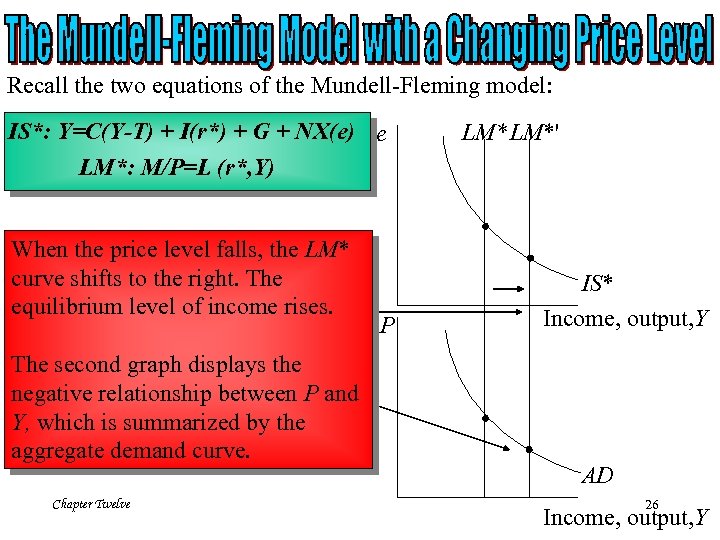

Recall the two equations of the Mundell-Fleming model: IS*: Y=C(Y-T) + I(r*) + G + NX(e) e LM*: M/P=L (r*, Y) When the price level falls, the LM* curve shifts to the right. The equilibrium level of income rises. The second graph displays the negative relationship between P and Y, which is summarized by the aggregate demand curve. Chapter Twelve P LM*' IS* Income, output, Y AD 26 Income, output, Y

Recall the two equations of the Mundell-Fleming model: IS*: Y=C(Y-T) + I(r*) + G + NX(e) e LM*: M/P=L (r*, Y) When the price level falls, the LM* curve shifts to the right. The equilibrium level of income rises. The second graph displays the negative relationship between P and Y, which is summarized by the aggregate demand curve. Chapter Twelve P LM*' IS* Income, output, Y AD 26 Income, output, Y

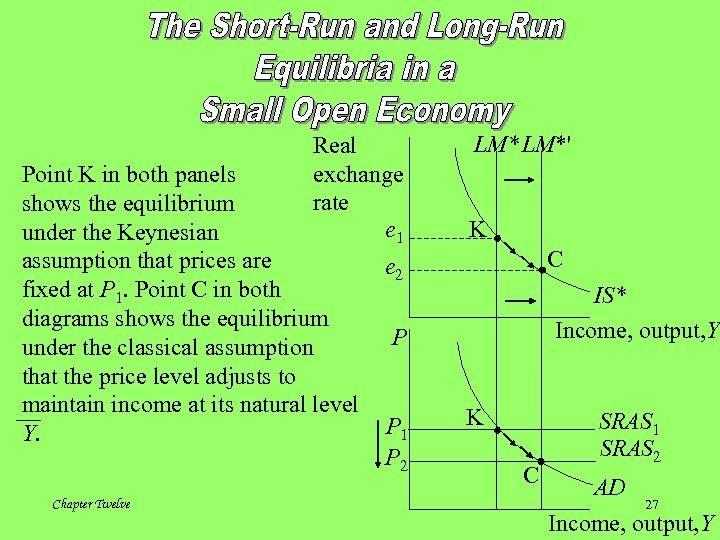

Real exchange rate e 1 Point K in both panels shows the equilibrium under the Keynesian assumption that prices are fixed at P 1. Point C in both diagrams shows the equilibrium under the classical assumption that the price level adjusts to maintain income at its natural level Y. Chapter Twelve LM*' K C e 2 IS* Income, output, Y P P 1 P 2 K C SRAS 1 SRAS 2 AD 27 Income, output, Y

Real exchange rate e 1 Point K in both panels shows the equilibrium under the Keynesian assumption that prices are fixed at P 1. Point C in both diagrams shows the equilibrium under the classical assumption that the price level adjusts to maintain income at its natural level Y. Chapter Twelve LM*' K C e 2 IS* Income, output, Y P P 1 P 2 K C SRAS 1 SRAS 2 AD 27 Income, output, Y

Mundell-Fleming Model Floating exchange rates Fixed exchange rates Devaluation Revaluation The Impossible Trinity Chapter Twelve 28

Mundell-Fleming Model Floating exchange rates Fixed exchange rates Devaluation Revaluation The Impossible Trinity Chapter Twelve 28