e7c194e1b7216f2a460a3f7fb7ca346d.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 34

The New Dyninst Code Parser: Binary Code Isn't as Simple as it Used to Be Nathan Rosenblum University of Wisconsin nater@cs. wisc. edu © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum March 2006 Unconventional Code Constructs

Binary Analysis § Processing of the binary code to extract syntactic and symbolic information from many sources: • Symbol tables (if present) • Decode (disassemble) instructions • Control-flow information: basic blocks, loops, functions • Data-flow information: from basic register information to highly sophisticated (and expensive) analyses. © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 2– Unconventional Code Constructs

Products of Binary Analysis § High-level organization and characteristics • Function entry/exit points • Intra-procedural call graph • Inter-procedural control-flow graph • Exception handlers • Jump tables • Virtual function tables § Abstract assembly representation § Data-flow characteristics • Register liveness (for instrumentation, modification) © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 3– Unconventional Code Constructs

Uses of Binary Analysis § Debugging § Testing § Performance profiling § Performance modeling § Behavior Modeling § Dynamic Modification § Binary Rewriting § Reverse engineering © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 4– Unconventional Code Constructs

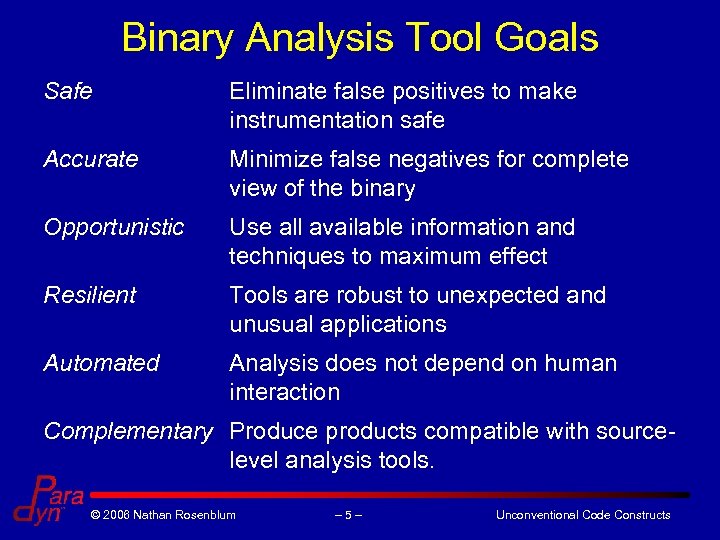

Binary Analysis Tool Goals Safe Eliminate false positives to make instrumentation safe Accurate Minimize false negatives for complete view of the binary Opportunistic Use all available information and techniques to maximum effect Resilient Tools are robust to unexpected and unusual applications Automated Analysis does not depend on human interaction Complementary Produce products compatible with sourcelevel analysis tools. © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 5– Unconventional Code Constructs

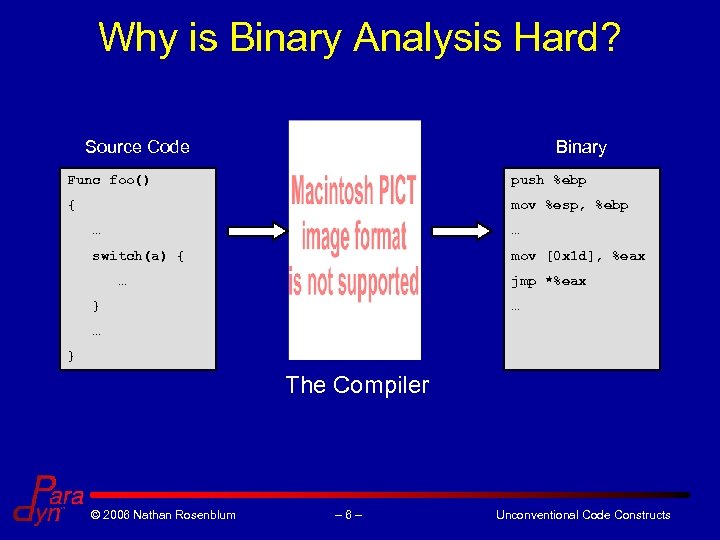

Why is Binary Analysis Hard? Source Code Binary Func foo() push %ebp { mov %esp, %ebp … … switch(a) { mov [0 x 1 d], %eax … jmp *%eax } … … } The Compiler © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 6– Unconventional Code Constructs

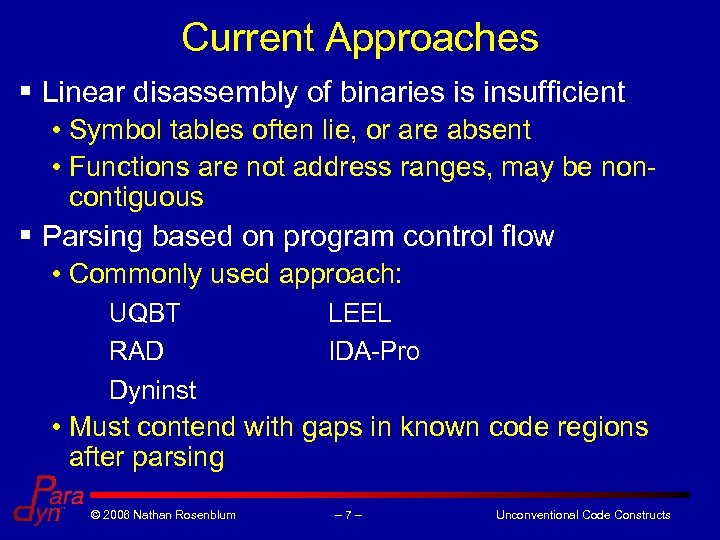

Current Approaches § Linear disassembly of binaries is insufficient • Symbol tables often lie, or are absent • Functions are not address ranges, may be noncontiguous § Parsing based on program control flow • Commonly used approach: UQBT RAD Dyninst LEEL IDA-Pro • Must contend with gaps in known code regions after parsing © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 7– Unconventional Code Constructs

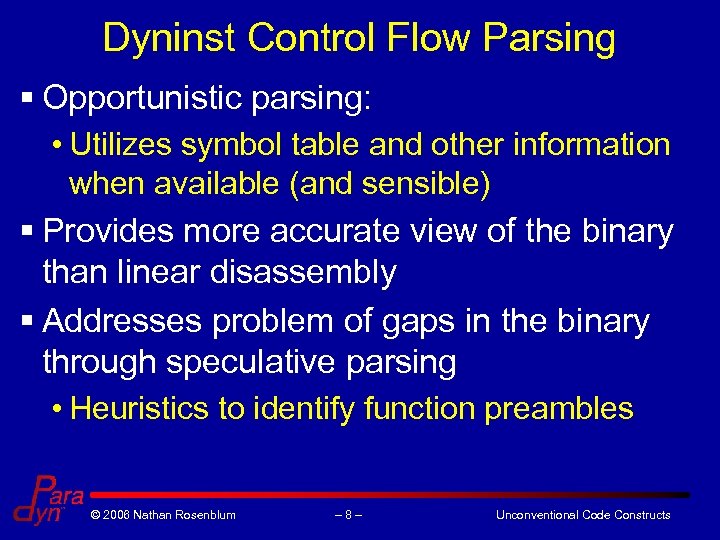

Dyninst Control Flow Parsing § Opportunistic parsing: • Utilizes symbol table and other information when available (and sensible) § Provides more accurate view of the binary than linear disassembly § Addresses problem of gaps in the binary through speculative parsing • Heuristics to identify function preambles © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 8– Unconventional Code Constructs

![Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov](https://present5.com/presentation/e7c194e1b7216f2a460a3f7fb7ca346d/image-9.jpg)

Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov [ac], r 2 08: add r 1, r 2, r 3 0 c: cmp r 3, 0 10: bne 24 14: call <bar> 18: add r 3, 8, r 3 1 c: call <baz> 20: jmp 28 24: mul r 2, 2, r 3 28: sub r 1, r 3, r 1. . . © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum • Parsing follows control flow • Control transfers are edges in the CFG • Target blocks can parsed in any order – 9– 00 24 14 28 Unconventional Code Constructs

![Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov](https://present5.com/presentation/e7c194e1b7216f2a460a3f7fb7ca346d/image-10.jpg)

Control Flow Traversal Illustrated <func foo>: 00: mov [a 8], r 1 04: mov [ac], r 2 08: add r 1, r 2, r 3 0 c: cmp r 3, 0 10: bne 24 14: call <bar> 18: add r 3, 8, r 3 1 c: call <baz> 20: jmp 28 24: mul r 2, 2, r 3 28: sub r 1, r 3, r 1. . . © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum • Call sites determine location of functions • Targets of calls are added to the function parsing work list – 10 – Known Functions foo quux quuux bar baz Unconventional Code Constructs

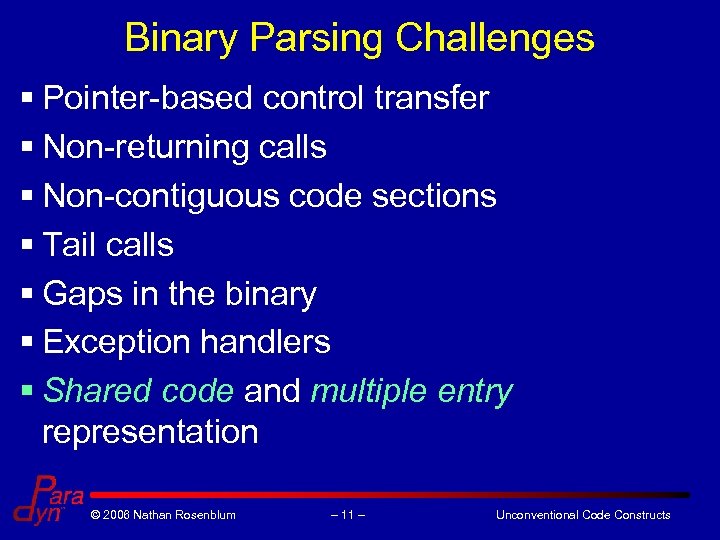

Binary Parsing Challenges § Pointer-based control transfer § Non-returning calls § Non-contiguous code sections § Tail calls § Gaps in the binary § Exception handlers § Shared code and multiple entry representation © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 11 – Unconventional Code Constructs

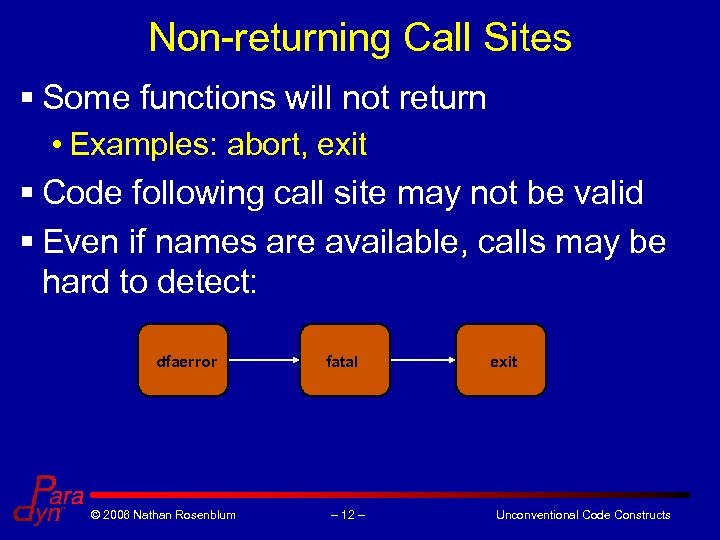

Non-returning Call Sites § Some functions will not return • Examples: abort, exit § Code following call site may not be valid § Even if names are available, calls may be hard to detect: dfaerror © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum fatal – 12 – exit Unconventional Code Constructs

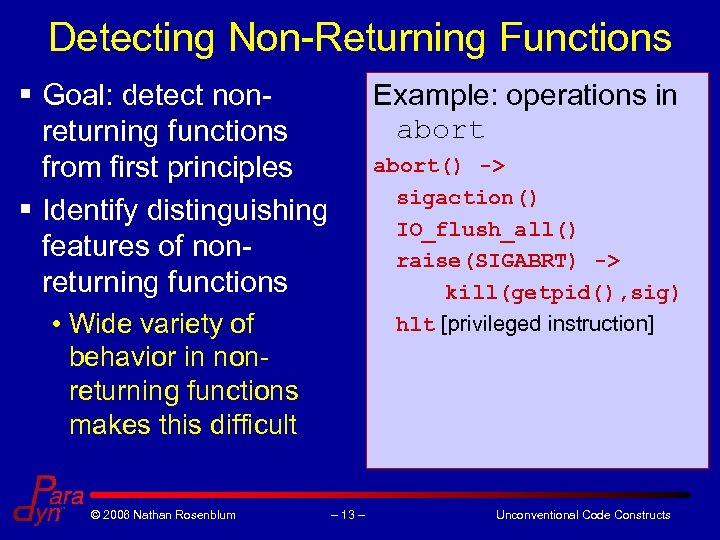

Detecting Non-Returning Functions § Goal: detect nonreturning functions from first principles § Identify distinguishing features of nonreturning functions Example: operations in abort() -> sigaction() IO_flush_all() raise(SIGABRT) -> kill(getpid(), sig) hlt [privileged instruction] • Wide variety of behavior in nonreturning functions makes this difficult © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 13 – Unconventional Code Constructs

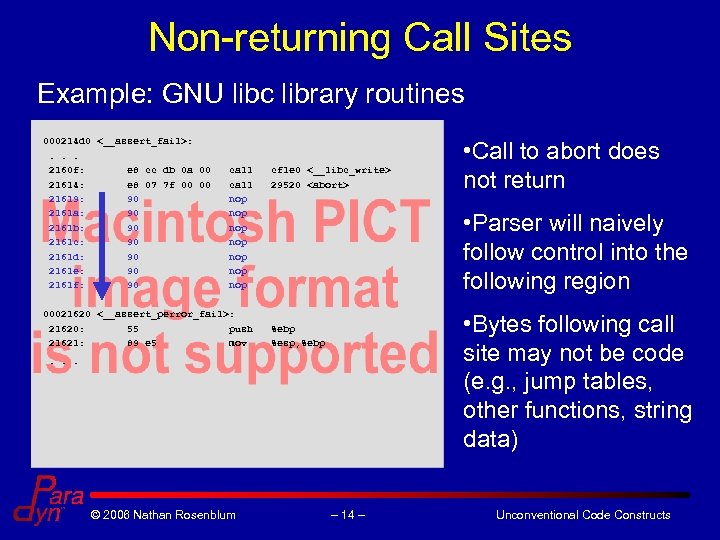

Non-returning Call Sites Example: GNU libc library routines 000214 d 0 <__assert_fail>: . . . 2160 f: e 8 cc db 0 a 00 call cf 1 e 0 <__libc_write> 21614: e 8 07 7 f 00 00 call 29520 <abort> 21619: 90 nop 2161 a: 90 nop 2161 b: 90 nop 2161 c: 90 nop 2161 d: 90 nop 2161 e: 90 nop 2161 f: 90 nop • Call to abort does not return 00021620 <__assert_perror_fail>: 21620: 55 push %ebp 21621: 89 e 5 mov %esp, %ebp • Bytes following call site may not be code (e. g. , jump tables, other functions, string data) . . . © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 14 – • Parser will naively follow control into the following region Unconventional Code Constructs

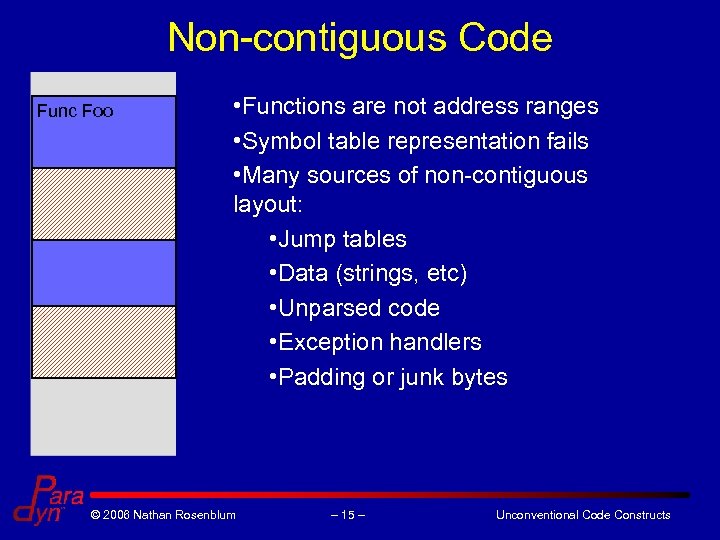

Non-contiguous Code Func Foo • Functions are not address ranges • Symbol table representation fails • Many sources of non-contiguous layout: • Jump tables • Data (strings, etc) • Unparsed code • Exception handlers • Padding or junk bytes © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 15 – Unconventional Code Constructs

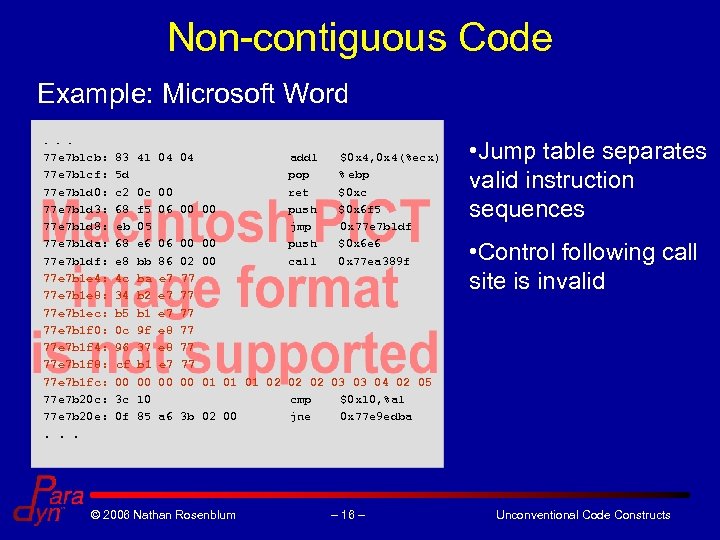

Non-contiguous Code Example: Microsoft Word. . . 77 e 7 b 1 cb: 83 41 04 04 addl $0 x 4, 0 x 4(%ecx) 77 e 7 b 1 cf: 5 d pop % ebp 77 e 7 b 1 d 0: c 2 0 c 00 ret $0 xc 77 e 7 b 1 d 3: 68 f 5 06 00 00 push $0 x 6 f 5 77 e 7 b 1 d 8: eb 05 jmp 0 x 77 e 7 b 1 df 77 e 7 b 1 da: 68 e 6 06 00 00 push $0 x 6 e 6 77 e 7 b 1 df: e 8 bb 86 02 00 call 0 x 77 ea 389 f 77 e 7 b 1 e 4: 4 c ba e 7 77 77 e 7 b 1 e 8: 34 b 2 e 7 77 77 e 7 b 1 ec: b 5 b 1 e 7 77 77 e 7 b 1 f 0: 0 c 9 f e 8 77 77 e 7 b 1 f 4: 96 37 e 8 77 77 e 7 b 1 f 8: cf b 1 e 7 77 77 e 7 b 1 fc: 00 00 01 01 01 02 02 02 03 03 04 02 05 77 e 7 b 20 c: 3 c 10 cmp $0 x 10, %al 77 e 7 b 20 e: 0 f 85 a 6 3 b 02 00 jne 0 x 77 e 9 edba. . . © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 16 – • Jump table separates valid instruction sequences • Control following call site is invalid Unconventional Code Constructs

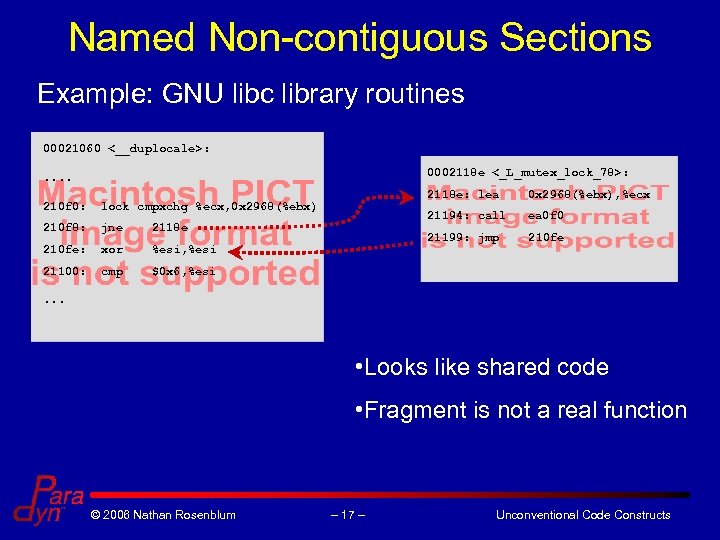

Named Non-contiguous Sections Example: GNU libc library routines 00021060 <__duplocale>: 0002118 e <_L_mutex_lock_78>: . . 2118 e: lea 0 x 2968(%ebx), %ecx 210 f 0: lock cmpxchg %ecx, 0 x 2968(%ebx) 21194: call ea 0 f 0 210 f 8: jne 2118 e 21199: jmp 210 fe: xor %esi, %esi 21100: cmp $0 x 6, %esi. . . • Looks like shared code • Fragment is not a real function © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 17 – Unconventional Code Constructs

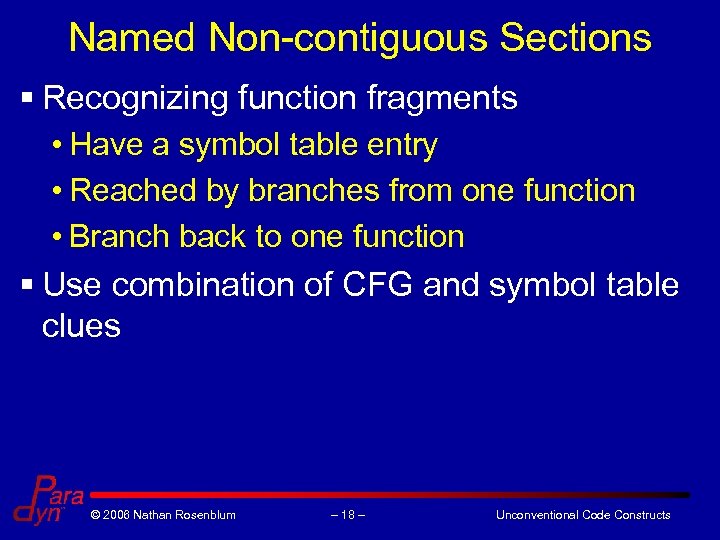

Named Non-contiguous Sections § Recognizing function fragments • Have a symbol table entry • Reached by branches from one function • Branch back to one function § Use combination of CFG and symbol table clues © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 18 – Unconventional Code Constructs

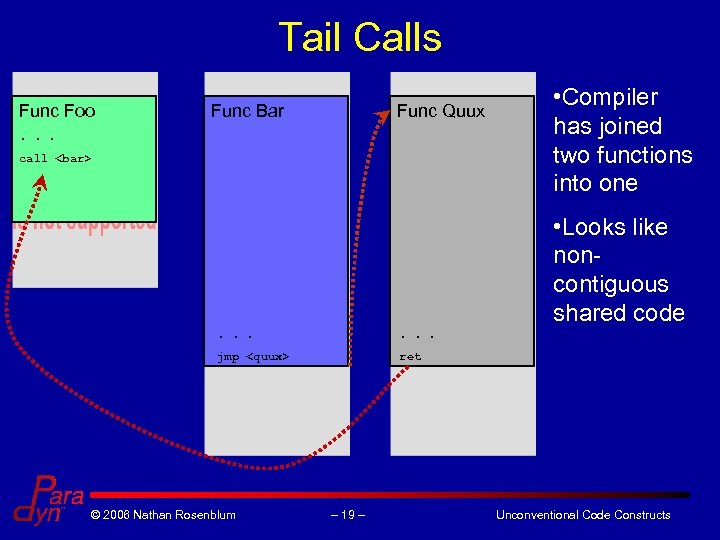

Tail Calls Func Foo Func Bar Func Quux . . . call <bar> • Compiler has joined two functions into one • Looks like noncontiguous shared code . . . jmp <quux> ret © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 19 – Unconventional Code Constructs

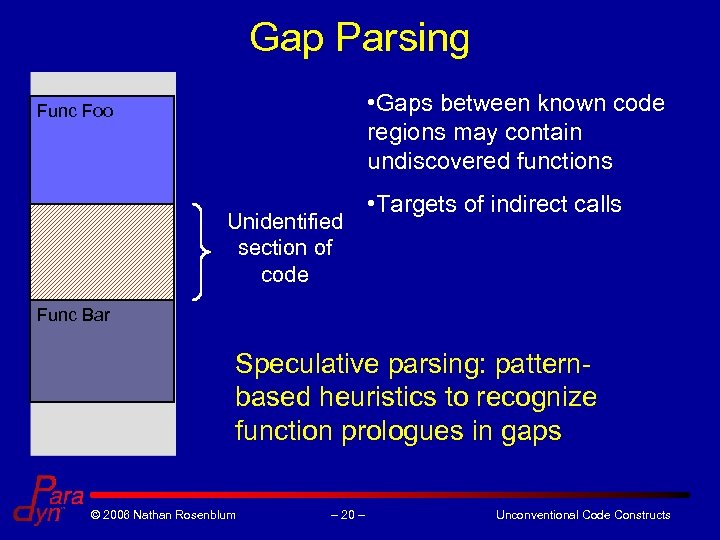

Gap Parsing • Gaps between known code regions may contain undiscovered functions Func Foo Unidentified section of code • Targets of indirect calls Func Bar Speculative parsing: patternbased heuristics to recognize function prologues in gaps © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 20 – Unconventional Code Constructs

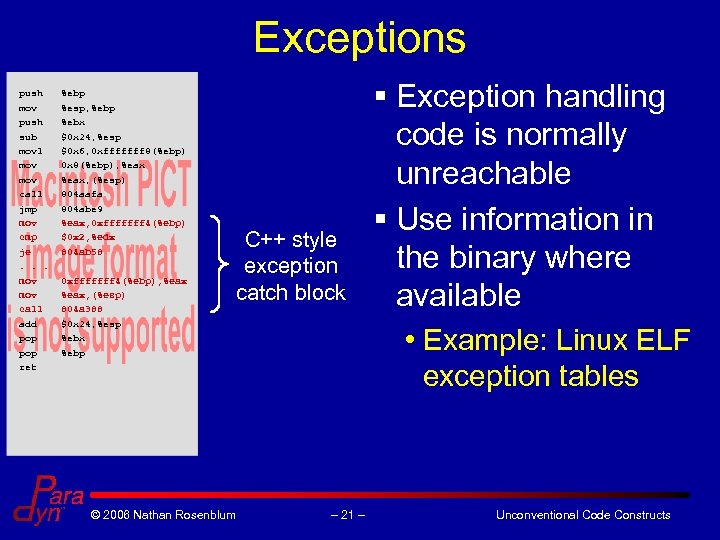

Exceptions push %ebp mov %esp, %ebp push %ebx sub $0 x 24, %esp movl $0 x 6, 0 xfffffff 8(%ebp) mov 0 x 8(%ebp), %eax mov %eax, (%esp) call 804 aafa jmp 804 abe 9 mov %eax, 0 xfffffff 4(%ebp) cmp $0 x 2, %edx je 804 ab 58 . . . mov 0 xfffffff 4(%ebp), %eax mov %eax, (%esp) call 804 a 388 add $0 x 24, %esp pop %ebx pop %ebp ret C++ style exception catch block © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum § Exception handling code is normally unreachable § Use information in the binary where available • Example: Linux ELF exception tables – 21 – Unconventional Code Constructs

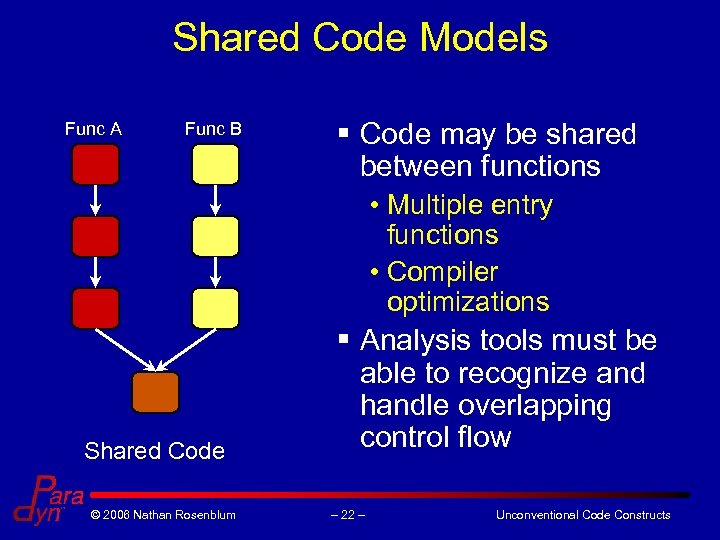

Shared Code Models Func A Func B § Code may be shared between functions • Multiple entry functions • Compiler optimizations Shared Code © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum § Analysis tools must be able to recognize and handle overlapping control flow – 22 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Summary of Binary Analysis Techniques § Control flow traversal is a powerful tool for addressing the challenges of modern binaries • Lying/missing symbol tables • Data/code disambiguation • Jump tables § Speculative parsing techniques can be useful for expanding code coverage • Gaps in code • Indirect calls and branches © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 23 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Incidence of Shared Code in Binaries § Parsed 828 Linux/x 86 binaries • 238 contained shared code § Most binaries contain only a few codesharing functions § Some code sharing may be due to nonreturning call sites © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 24 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Where Do We Go From Here? § Are there good solutions from first principles? • Almost certainly. • We are just starting to explore the limits of such techniques. § Are special case solutions necessary? • Again, almost certainly. • We will try to use these as sparingly as possible. © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 25 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Future Directions in Binary Analysis § Problem: code exists but is unreachable through standard control-flow traversal parsing • Heuristics are a moving target § Existing opportunistic parsing techniques can help, but only to an extent • Exception handlers, virtual function tables may be recoverable from the binary § Given the information we can recover from traditional techniques, can we synthesize additional information that will increase coverage of the binary? © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 26 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Statistical Binary Parsing § Can we utilize known code to find unknown code? • We have a partial parse of the binary • Code unknown regions of the binary will likely share characteristics with previously identified code § Identify code in unknown regions: • Create a probabilistic model of valid code • Identify sections of unknown regions in the binary that are similar to valid code © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 27 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Binary Modeling Techniques § Code idioms are one possibility for validating potential code • Function preambles, jump table bounds tests, system call stubs, case statements § Idioms can be identified manually § Model can be trained to identify new idioms with machine learning techniques • n-gram models, long-distance interaction § Unparsed code can be scored to indicate its statistical similarity to known code © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 28 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Open Questions in Binary Analysis § What learning techniques will yield the best results? § How can we overcome the relative dearth of information in binaries with very little code reachable through control flow analysis? • Incorporate information from analysis of other binaries § What techniques will allow us to accurately identify the range of recognizable code? © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 29 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Questions? © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 30 – Unconventional Code Constructs

Backup Slides © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 31 – Unconventional Code Constructs

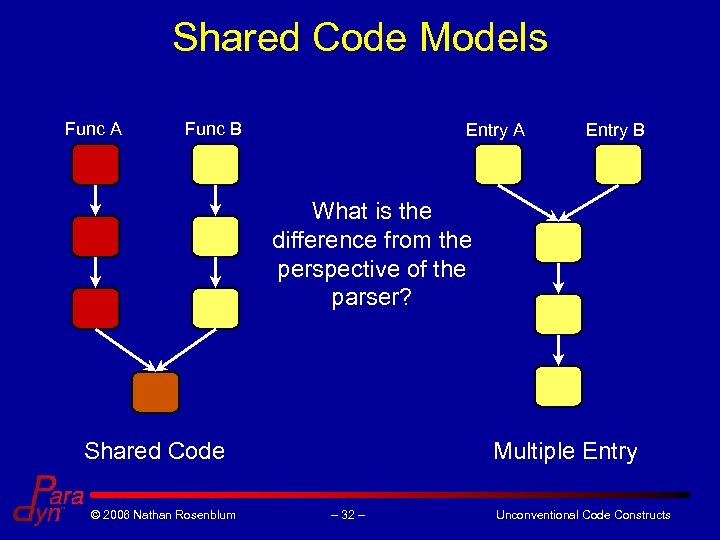

Shared Code Models Func A Func B Entry A Entry B What is the difference from the perspective of the parser? Shared Code © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum Multiple Entry – 32 – Unconventional Code Constructs

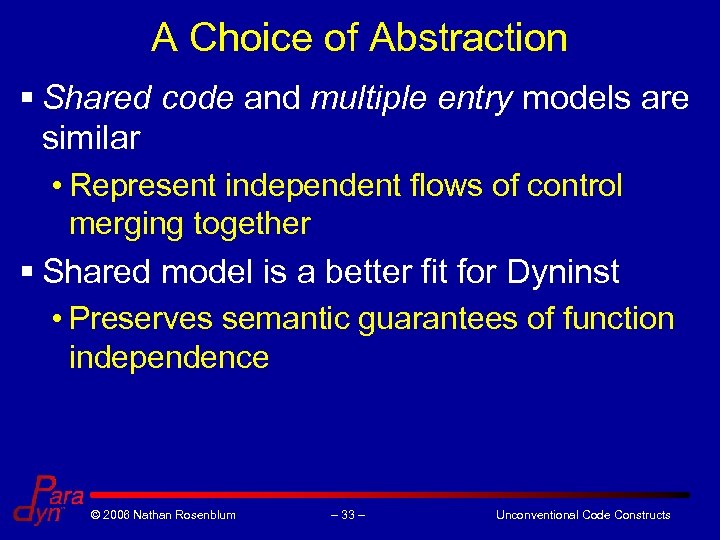

A Choice of Abstraction § Shared code and multiple entry models are similar • Represent independent flows of control merging together § Shared model is a better fit for Dyninst • Preserves semantic guarantees of function independence © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 33 – Unconventional Code Constructs

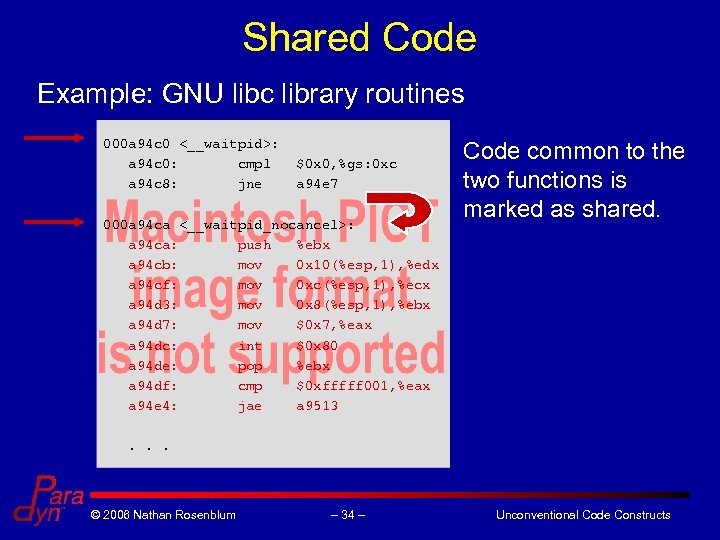

Shared Code Example: GNU libc library routines 000 a 94 c 0 <__waitpid>: a 94 c 0: cmpl a 94 c 8: jne $0 x 0, %gs: 0 xc a 94 e 7 000 a 94 ca <__waitpid_nocancel>: a 94 ca: push %ebx a 94 cb: mov 0 x 10(%esp, 1), %edx a 94 cf: mov 0 xc(%esp, 1), %ecx a 94 d 3: mov 0 x 8(%esp, 1), %ebx a 94 d 7: mov $0 x 7, %eax a 94 dc: int $0 x 80 a 94 de: pop %ebx a 94 df: cmp $0 xfffff 001, %eax a 94 e 4: jae a 9513 Code common to the two functions is marked as shared. . © 2006 Nathan Rosenblum – 34 – Unconventional Code Constructs

e7c194e1b7216f2a460a3f7fb7ca346d.ppt