1549a3a2660c48c4151a13b2d6455cc6.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 44

The ‘look’ of the document: the colonial subject in transit, British India, 1882 -1921. • This talk compares the ‘look’ of the international form of the British Indian passport with that of the pilgrim passport, the document issued to Muslims when they set off to perform the Hajj in Arabia. It reviews debates about the indexical value of the photograph, as against the thumbprint and concludes with a discussion about space as a consideration in the ‘look’ of a travel document. The British Indian passport as it was recast over 1914 -21 marked the potential entry of India as a distinct actor in an international state system. Yet a ‘local and regressive’ practice left its mark on the document, in the reluctant permission given to pardah women, those who observed norms of female seclusion to submit a thumbprint in place of a photograph. ‘Lesser standards’ were even more marked in the ‘look’ of the pilgrim passport , yet this document gave substance to the assertion, such as that made by Viceroy Hardinge in 1916, that the British empire ought to be visualized as the ‘biggest Mohammedan power in the world. ’

The documentary pile • 1840 s: The Foreign Department Passport: “the protection of the British Crown” • • 1840 s: The coolie agreement, for “natives of a different class”. The Emigration Pass authorizing departure for the coolie. These are 2 levels of official certification to demonstrate the consent of the worker. • 1882 : The pilgrim passport: “freedom to travel to fulfill a religious obligation” Muslim travellers going on the Hajj to Arabia • 1880 s: the certificate of identity, keeping travelling students ‘in view’ the certificate of identity was often accepted as a passport. . • 1904 -05 The Australian passport ( by special arrangement)

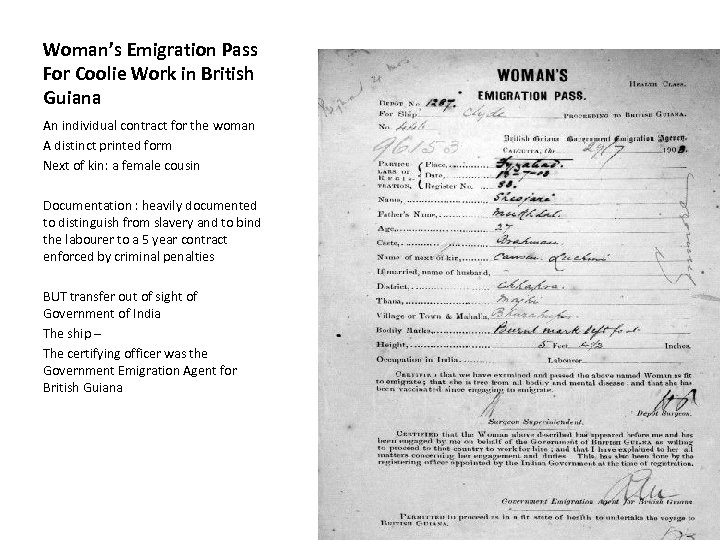

Woman’s Emigration Pass For Coolie Work in British Guiana An individual contract for the woman A distinct printed form Next of kin: a female cousin Documentation : heavily documented to distinguish from slavery and to bind the labourer to a 5 year contract enforced by criminal penalties BUT transfer out of sight of Government of India The ship – The certifying officer was the Government Emigration Agent for British Guiana

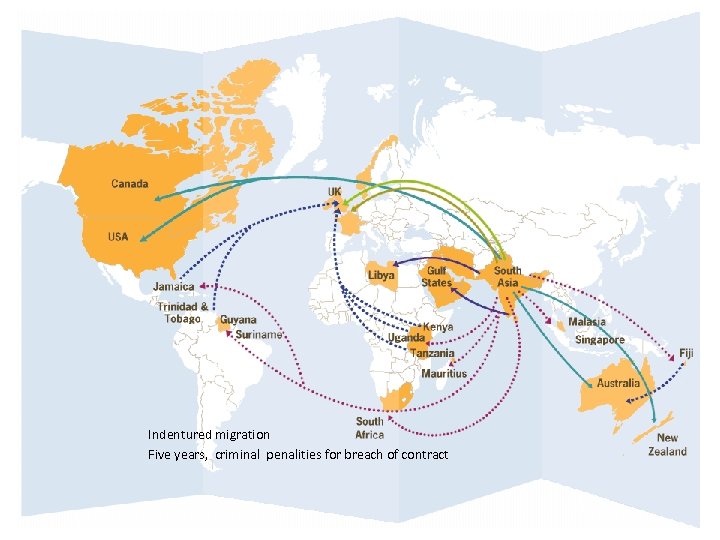

Indentured migration Five years, criminal penalities for breach of contract

The much more dense undocumented flow • ‘free’ migration around the Bay of Bengal – to Ceylon, Burma, the Straits, Malaya • Cast as part-time, seasonal, temporary

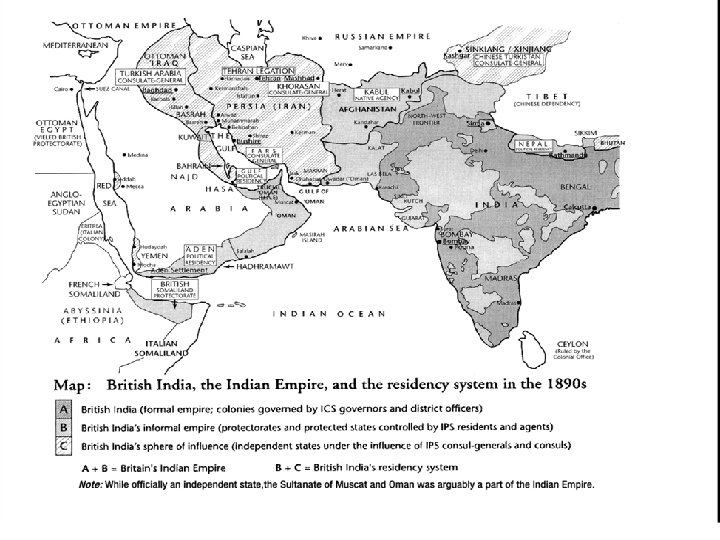

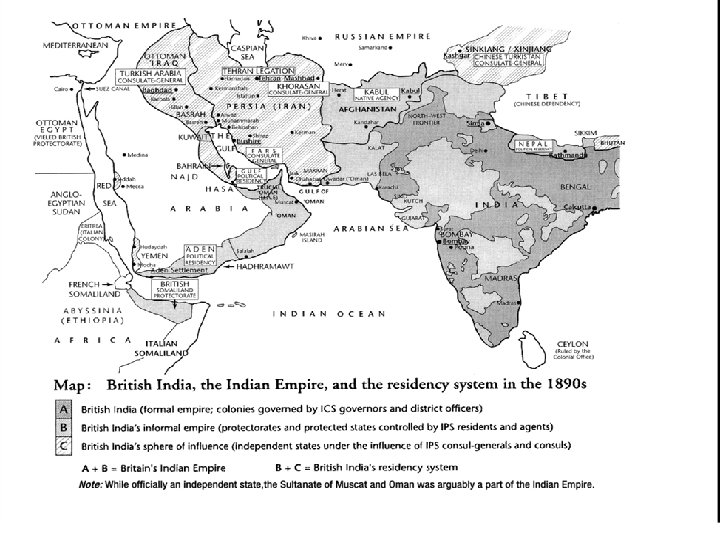

The extra-territorial value of the British Indian passport • Extra-territoriality : Ottoman Arabia, Persia, Siam, Oman, Chinese and Russian Central Asia • For labour migration to British Columbia, Australia, Argentina –Forged passports, impersonation, ‘touts’ , ‘disguised’ labour recruiters • But with white dominions such as Australia and Canada and South Africa, the colour bar

• Acknowledgements, James Onley, ‘The Raj Reconsidered: British India’s informal empire and spheres of influence in Asia and Africa’ Asian Affairs, Vol. XL, No. 1, March 2009.

Passport as indicator of sufficient identity • Special passport for Australia 1904 exempted from literacy test in a European language if they were `bonafide’ tourists, merchants and students’ • Entry and temporary residence if there were SUFFICIENT identity which meant the signalling of an identity, a location, to which the traveller could be returned • a very complete return address

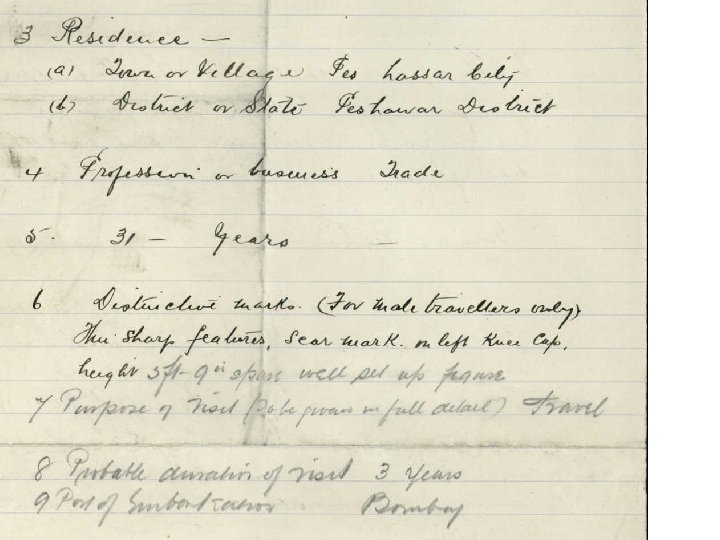

Details entered into an Australian passport for Sher Ghulam and accompanying servant: predocumentary document

• Paperised travel bore the marks both of social hierarchy and the networks, official and commercial, through which mobility was channelised • Control of documentation gave control over the traveller to the employer, the pilgrim guide, the husband • On all these documents, until World War I, the employer vouched for the servant ( pilgrim passport, Australian passport, British Indian passport) • Male relatives vouched for wives and children • The group character of the pilgrim passport –. the pilgrim band led by a guide, mutawwif with links to the brokers for the shipping company

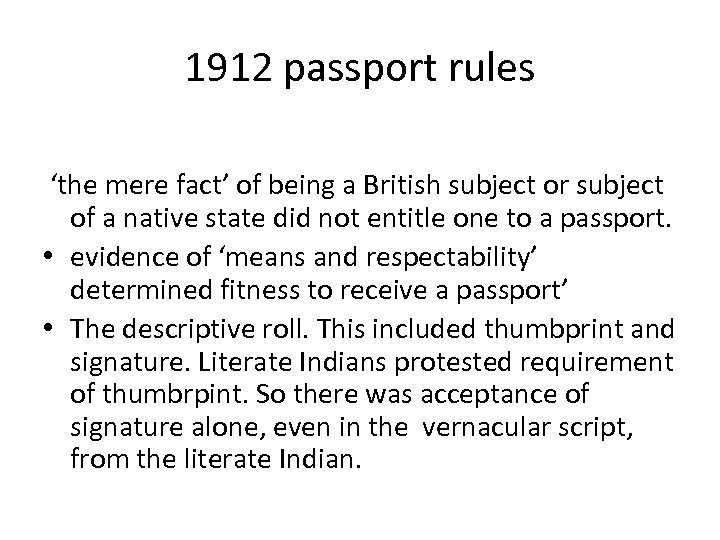

1912 passport rules ‘the mere fact’ of being a British subject or subject of a native state did not entitle one to a passport. • evidence of ‘means and respectability’ determined fitness to receive a passport’ • The descriptive roll. This included thumbprint and signature. Literate Indians protested requirement of thumbrpint. So there was acceptance of signature alone, even in the vernacular script, from the literate Indian.

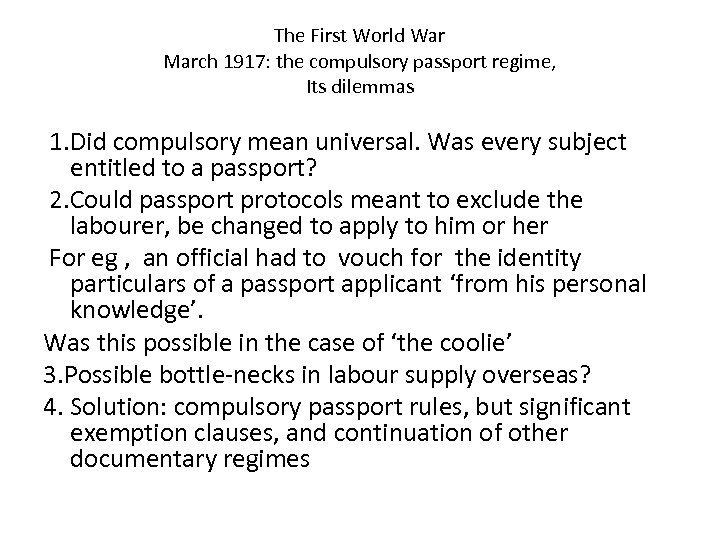

The First World War March 1917: the compulsory passport regime, Its dilemmas 1. Did compulsory mean universal. Was every subject entitled to a passport? 2. Could passport protocols meant to exclude the labourer, be changed to apply to him or her For eg , an official had to vouch for the identity particulars of a passport applicant ‘from his personal knowledge’. Was this possible in the case of ‘the coolie’ 3. Possible bottle-necks in labour supply overseas? 4. Solution: compulsory passport rules, but significant exemption clauses, and continuation of other documentary regimes

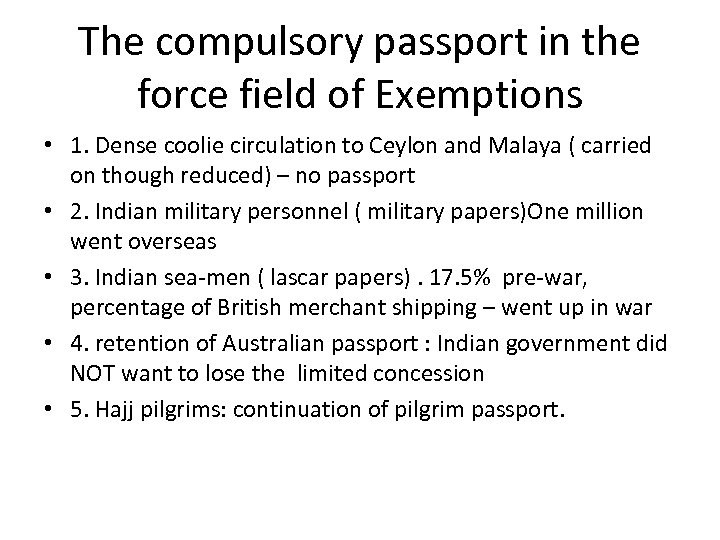

The compulsory passport in the force field of Exemptions • 1. Dense coolie circulation to Ceylon and Malaya ( carried on though reduced) – no passport • 2. Indian military personnel ( military papers)One million went overseas • 3. Indian sea-men ( lascar papers). 17. 5% pre-war, percentage of British merchant shipping – went up in war • 4. retention of Australian passport : Indian government did NOT want to lose the limited concession • 5. Hajj pilgrims: continuation of pilgrim passport.

Seeking legibility in empire and internationally “the final result would be a standardised Indian passport, differing only in minor detail from the standardised form the whole Empire and valid all the world over. ”Note, Foreign and Political Department, Government of India 7 April 1917

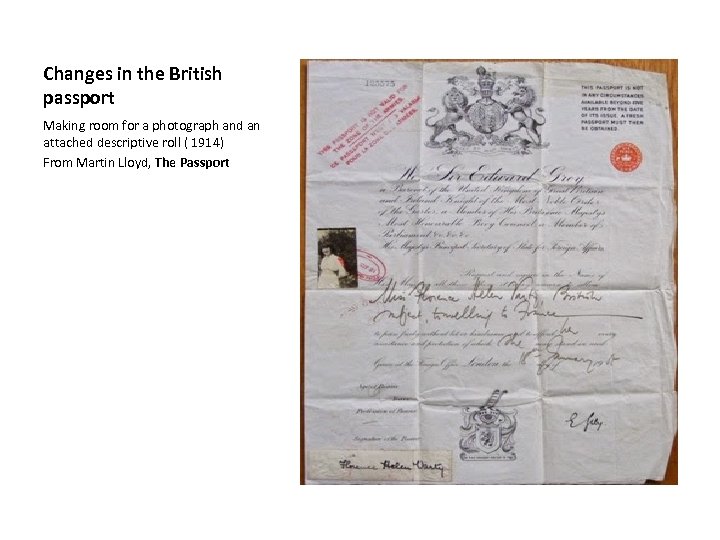

Changes in the British passport Making room for a photograph and an attached descriptive roll ( 1914) From Martin Lloyd, The Passport

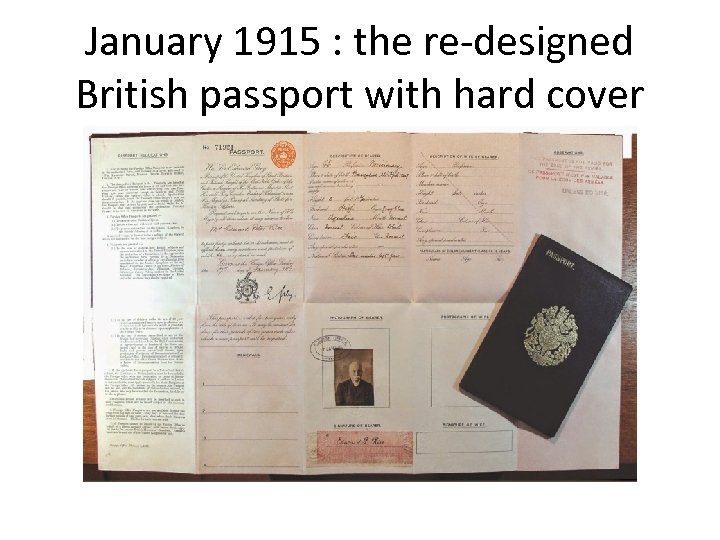

January 1915 : the re-designed British passport with hard cover

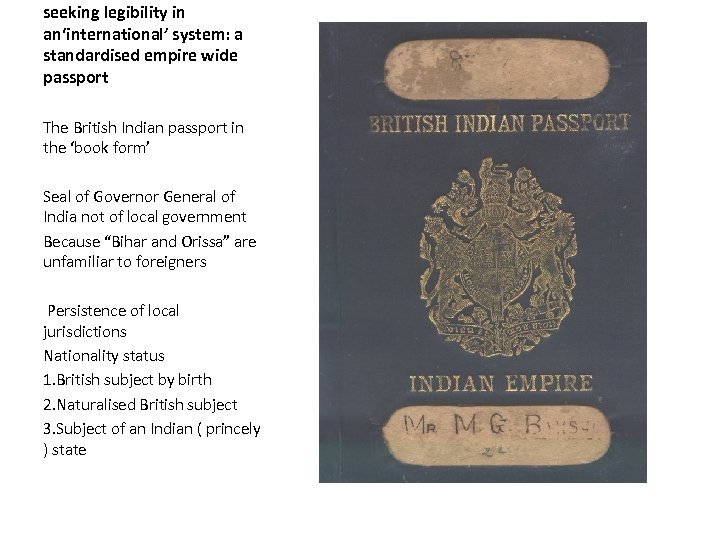

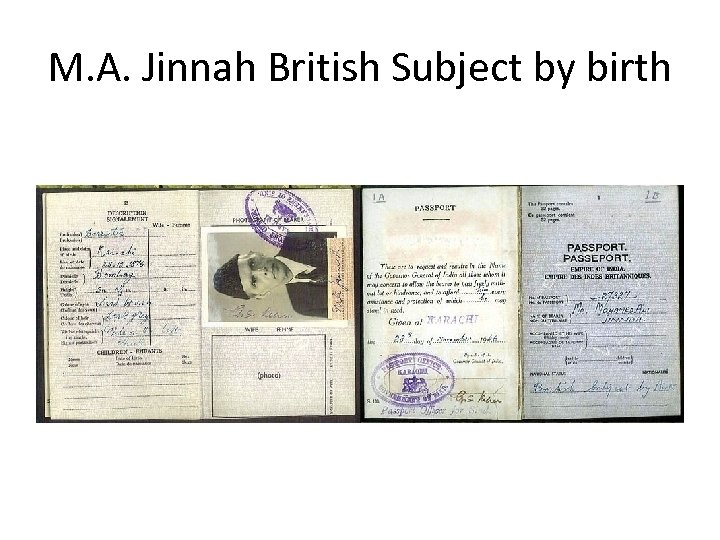

seeking legibility in an‘international’ system: a standardised empire wide passport The British Indian passport in the ‘book form’ Seal of Governor General of India not of local government Because “Bihar and Orissa” are unfamiliar to foreigners Persistence of local jurisdictions Nationality status 1. British subject by birth 2. Naturalised British subject 3. Subject of an Indian ( princely ) state

M. A. Jinnah British Subject by birth

The passport photograph: ‘scientific’ identification? • Mediations between the portrait photograph and its bureaucratic recomposition: traveller provided the photograph • Attestation and attachment to passport by seal and signature • Just enough resemblance for the border official. • Thumb-print ‘infallible’ – but required time and expertise and was associated with criminals, unwanted immigrants and colonised races

The ‘unveiling’ photograph • Petitions of protest from Hindu and Muslim merchants in trading networks with Zanzibar, East Africa, Uganda, Nyaasaland, The Straits and Malaya • Demand that women observing pardah and gosha (veiling) be exempted from the photograph • Argument: use thumb print instead or male family members could vouch for female travellers • There was also anxiety about immigration rules relating to the definition of family arising from demands for proof of marriage

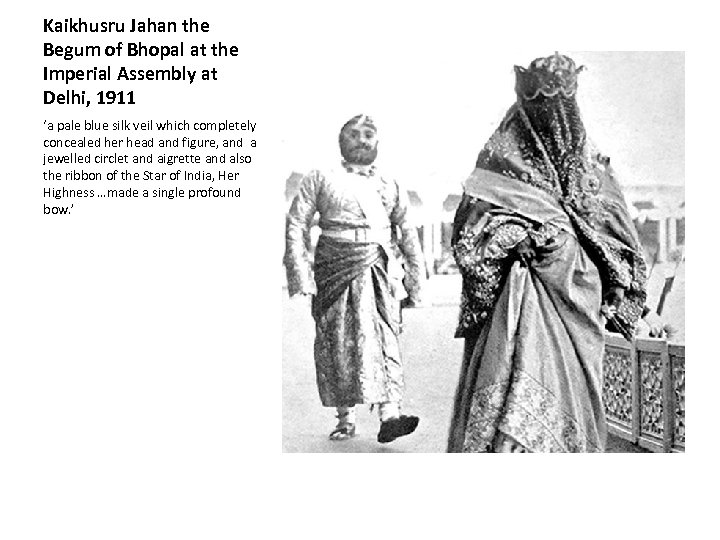

The search for precedents: photographs of pardah women • Her Highness the Nawab Begum of Bhopal, GCSI, GCIE, CI

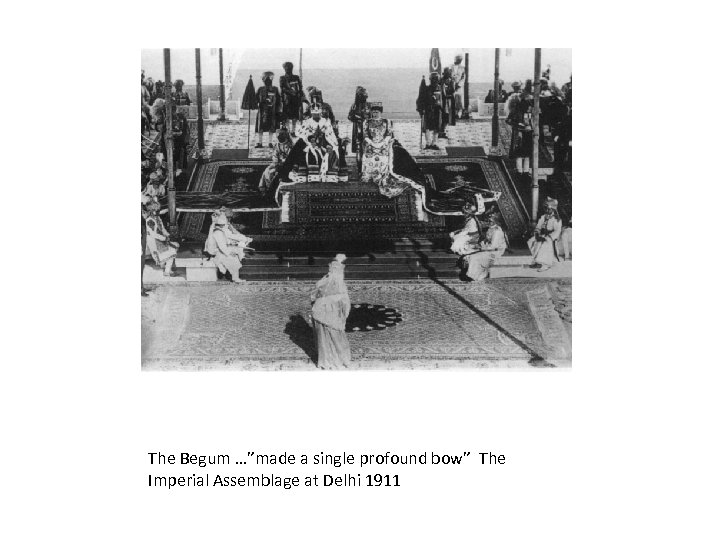

The Historical Record of the Imperial Visit to Delhi, 1911, facing p 136 The search for a precedent: photographs of pardah women The Begum of Bhopal : the ‘only Muslim woman ruler’ in India (

Kaikhusru Jahan the Begum of Bhopal at the Imperial Assembly at Delhi, 1911 ‘a pale blue silk veil which completely concealed her head and figure, and a jewelled circlet and aigrette and also the ribbon of the Star of India, Her Highness …made a single profound bow. ’

The Begum …”made a single profound bow” The Imperial Assemblage at Delhi 1911

International relations ‘from below’: the transnational purchase of pardah norms • Expansion of territory and spheres of influence in Muslim majority areas of Ottoman empire (Egypt, 1914, Arabia, 1916, occupation of Iraq, British Mandate) • 1919 Khilafat movement, India, protesting French and British militarism in Muslim majority areas of Ottoman empire and control over Islamic sacred sites • The British empire as ‘the largest Muhammadan power in the world’

Exemption for purdah women • October 1918 : exemption for passport photographs for pardah women entering from the Straits, Malaya, Mauritius, Nyaasaland, East Africa, Uganda, Zanzibar • April 1919 : Persian Gulf Ports and Iraq

The pilgrim passport: the necessity of a lower standard • No photograph required, even for men • No thumbprint as substitute for photograph • Only descriptive roll

The “problem of the pauper” pilgrim: Images of destitute, diseased and dying pilgrims • “professional mendicant”? – or a “bonafide pilgrim” • A victim to be protected? • A danger to others ? contagious disease – cholera and the plague • Fiscal burden of repatriation (exaggerated by government; first outlay in 1912 due to Balkan wars)

Should ‘beggars’ cross borders? • • • Discussion of Means test Security deposits Compulsory passport Vs Right of access to a sacred geography

Geo-politics and a niche for the poor pilgrim • Poor pilgrims were not just a problem for empire. They were a resource • Liberty to travel to fulfill a religious obligation: invoked on behalf of British commerce and shipping • And in inter-imperial competition for legitimacy of rule over Muslim subjects : the Ottomans, France, Russia, the Dutch. • trans-frontier Hajjis from Afghanistan, Russian Central Asia , Chinese Turkestan – routed through Bombay • Rivalry for territory and influence along the Arabian frontiers of the Ottoman empire and the Indian Empire

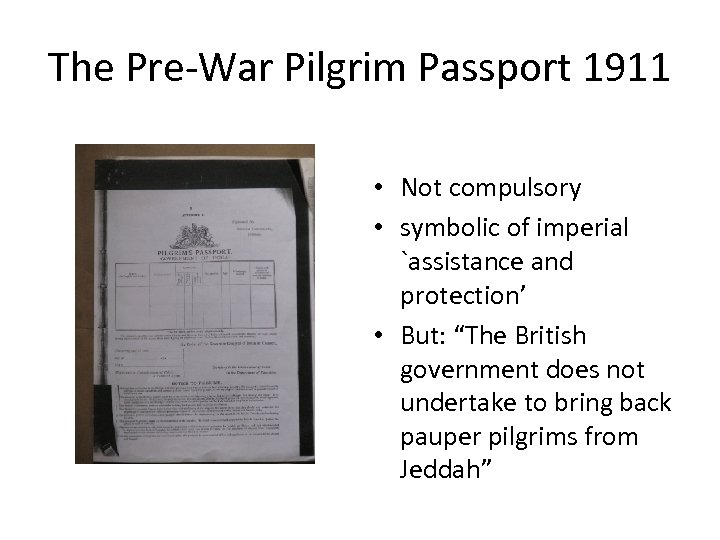

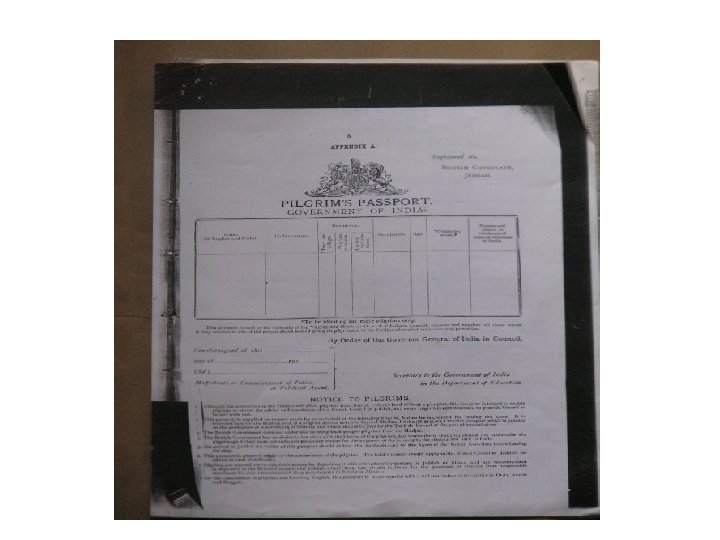

The Pre-War Pilgrim Passport 1911 • Not compulsory • symbolic of imperial `assistance and protection’ • But: “The British government does not undertake to bring back pauper pilgrims from Jeddah”

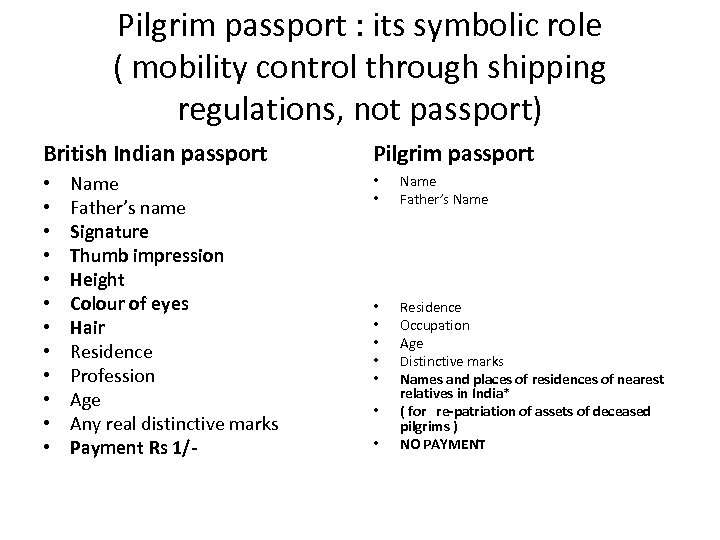

Pilgrim passport : its symbolic role ( mobility control through shipping regulations, not passport) British Indian passport • • • Name Father’s name Signature Thumb impression Height Colour of eyes Hair Residence Profession Age Any real distinctive marks Payment Rs 1/- Pilgrim passport • • Name Father’s Name • • • Residence Occupation Age Distinctive marks Names and places of residences of nearest relatives in India* ( for re-patriation of assets of deceased pilgrims ) NO PAYMENT • •

World war one: the compulsory pre-paid return ticket • No longer just symbolic, the identity particulars of the pilgrim passport were now used to link the pilgrim to a compulsory return ticket subsidized by government for some years. • Objective was to prevent sale and transfer of this ticket • The pilgrim passport , linked to the pre-paid ship ticket, was now a composite artefact designed to loop the pilgrim back mostly at his own expense.

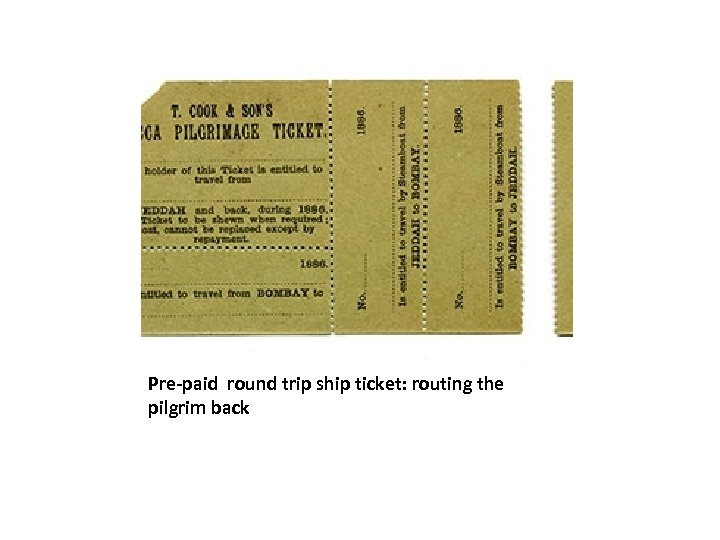

Pre-paid round trip ship ticket: routing the pilgrim back

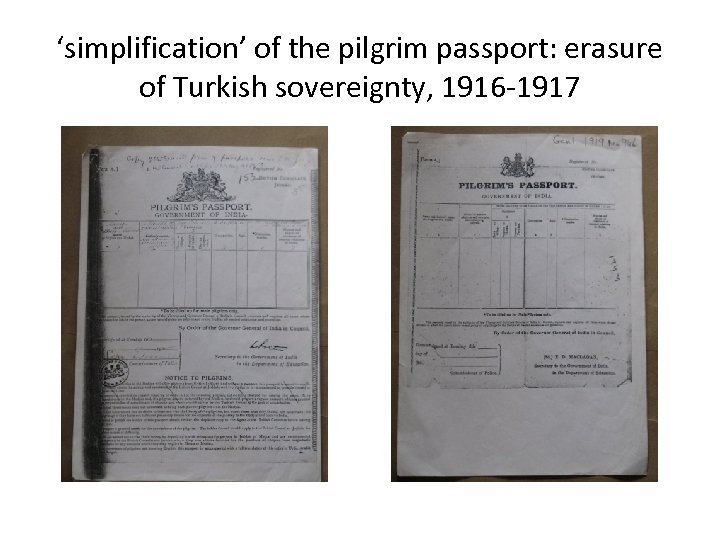

‘simplification’ of the pilgrim passport: erasure of Turkish sovereignty, 1916 -1917

The pilgrim passport : antiquated and obsolete? • Photograph –objection to representation of human form on a religious journey • Thumb – print? Treating Hajjis like convicts? • Signature? Illiteracy assumed, not even a designated space

Post-War: sharper national boundaries between alien and Indian pilgrims. • Afghanistan, Persia insisted on national passports for their pilgrims • Discussion by GOI about removing writ of “assistance and protection”, making the pilgrim passport merely a travel pass • Insistence on retaining ‘quasi-passport’ invocation of sovereignty and care for its own pilgrims.

The landscapes of pilgrim movement • International relations from below • Commerce, shipping, pilgrimage • Balkan wars: mobilisation of trans-national Muslim public opinion for defence of the sacred spaces of Islam • The British empire as ‘the largest Muhammadan empire in the world’ • ‘naturalisation’ of acquisitions of territory and influence from Ottoman empire • The mobility of the poor pilgrim could be curtailed not cut off.

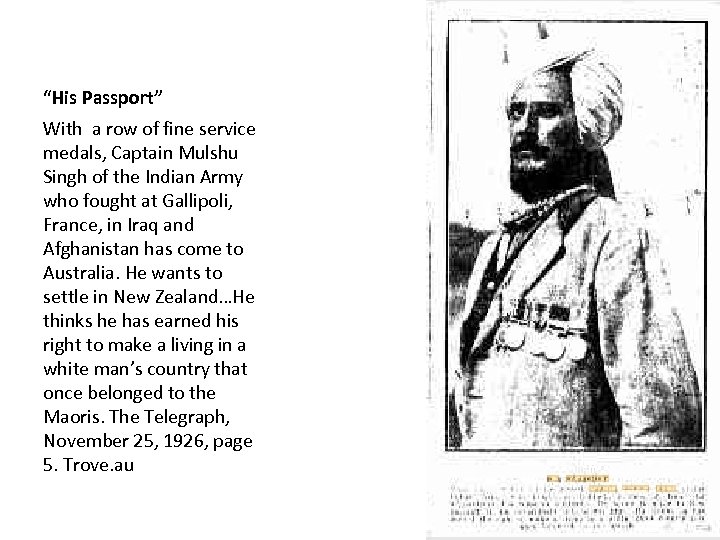

“His Passport” With a row of fine service medals, Captain Mulshu Singh of the Indian Army who fought at Gallipoli, France, in Iraq and Afghanistan has come to Australia. He wants to settle in New Zealand…He thinks he has earned his right to make a living in a white man’s country that once belonged to the Maoris. The Telegraph, November 25, 1926, page 5. Trove. au

1549a3a2660c48c4151a13b2d6455cc6.ppt