e5b199218a8b095deb76d709f0017821.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 48

The Linguistic Cycle: Background, common cycles, and an account Elly van Gelderen 14 November 2014 High desert Linguistics Conference

Outline • Views on the cycle • Micro and macrocyles • The Subject and Copula Cycles • Explanations for the loss and renewal

The Cycle: a definition A linguistic cycle describes a regular pattern of language change, a round of linguistic changes taking place in a systematic manner and direction. For instance, negation may at some stage involve one negative and then an optional second negative may be added after which the first one disappears. This new negative may be reinforced by yet another negative and may then itself disappear.

Heine, Claudi, & Hünnemeyer’s types 1. “isolated instances of grammaticalization”, as when a lexical item grammaticalizes and is then replaced by a new lexeme. For instance, the lexical verb go (or want) being used as a future marker. 2. “subparts of language, for example, when the tense-aspect-mood system of a given language develops from a periphrastic into an inflexional pattern and back to a new periphrastic one” or when negatives change.

and 3. “entire languages and language types” but there is “more justification to apply the notion of a linguistic cycle to individual linguistic developments”, e. g. the development of future markers, of negatives, and of tense, rather than to changes in typological character, as in from analytic to synthetic and back to analytic.

Caution about the third kind Heine et al’s reasons for caution about the third type of change, i. e. a cyclical change in language typology, is that we don’t know enough about older stages of languages. Most linguists are comfortable with cycles of the first and second kind but they are not with cycles of the third kind, e. g. Jespersen (1922; chapter 21. 9).

Microcycle: the future cycle (1)a. I’m gonna leave for the summer. b. *I’m gonna to Flagstaff for the summer. Nesselhauf (2012) provides a very precise account of the changes in the various future markers (shall, will, ‘ll, be going to, be to, and the progressive) in the last 250 years. She identifies three crucial features, intention, prediction, and arrangement, and argues that as the sense of intention is lost and is replaced by the sense of prediction, new markers of intention will appear: want has intention in (2 a) and it is starting to gain the sense of prediction, as in (2 b). (2) a. The final injury I want to talk about is brain damage. . . (Nesselhauf 2012: 114). b. We have an overcast day today that looks like it wants to rain. (Nesselhauf 2012: 115).

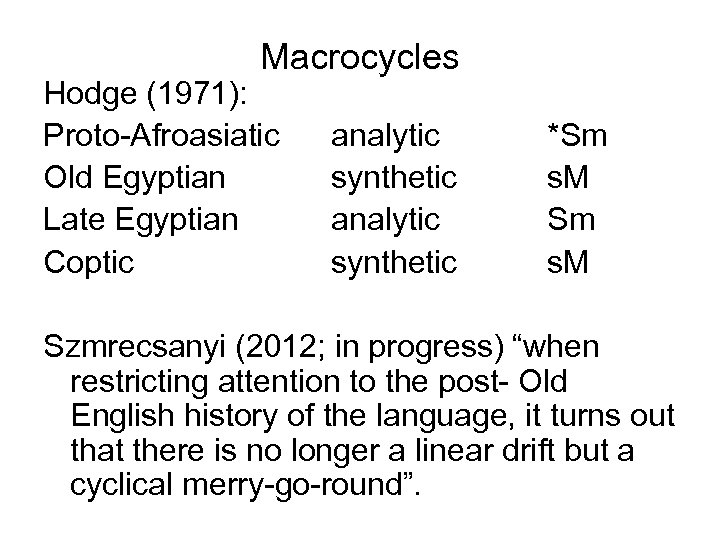

Macrocycles Hodge (1971): Proto-Afroasiatic Old Egyptian Late Egyptian Coptic analytic synthetic *Sm s. M Szmrecsanyi (2012; in progress) “when restricting attention to the post- Old English history of the language, it turns out that there is no longer a linear drift but a cyclical merry-go-round”.

von der Gabelentz 1901: 256 The history of language moves in the diagonal of two forces: the impulse toward comfort, which leads to the wearing down of sounds, and that toward clarity, which disallows the wearing down to destroy the language. The affixes grind themselves down, disappear without a trace; their functions or similar ones, however, require new expression.

ctd They acquire this expression, by the method of isolating languages, through word order or clarifying words. The latter, in the course of time, undergo agglutination, erosion, and in the mean time renewal is prepared: periphrastic expressions are preferred. . . always the same: the development curves back towards isolation, not in the old way, but in a parallel fashion. That's why I compare them to spirals“ Cf. also Meillet (1912: 140): “une sorte de développement en spirale”

Comfort + Clarity = Grammaticalization + Renewal Von der Gabelentz’ examples of comfort: the unclear pronunciation of everyday expressions, the use of a few words instead of a full sentence, i. e. ellipsis (p. 182 -184), “syntaktische Nachlässigkeiten aller Art” (`syntactic carelessness of all kinds’, p. 184), and loss of gender. Examples of clarity: special exertion of the speech organs (p. 183), “Wiederholung” (`repetition’, p. 239), periphrastic expressions (p. 239), replacing words like sehr `very’ by more powerful and specific words such as riesig `gigantic’ and schrecklich `frightful’ (243), using a rhetorical question instead of a regular proposition, and also replacing case with prepositions (p. 183).

Robins (1967: 150 -159) provides a useful overview: de Condillac (1746) and Tooke (1786; 1805) think that abstract, grammatical vocabulary develops from earlier concrete vocabulary. Bopp (1816) similarly argues that affixes arise from earlier independent words.

Why look at this? For generative grammar: if change is in the same direction, the child is ‘reanalyzing’ it one way and this gives insight into the language faculty. What are the features that are renewed? How is the structure changed? Not everyone agrees, e. g. Bybee (1985), Bybee, Perkins, Pagliuca (1994): “no gramtype is universal”

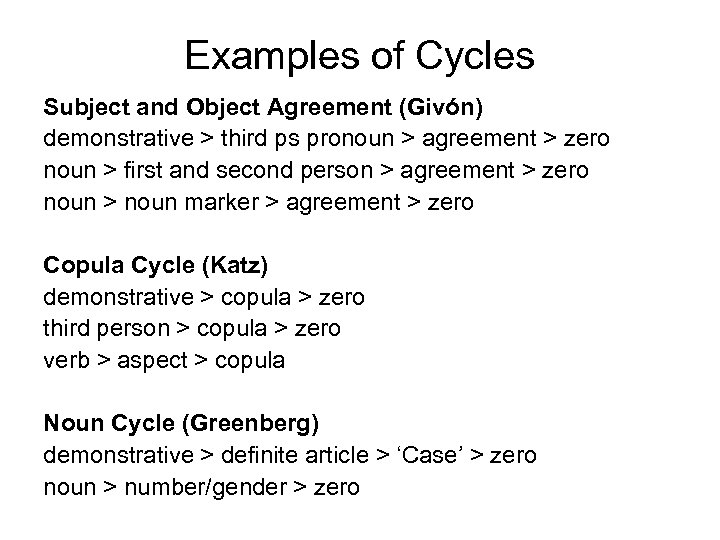

Examples of Cycles Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero noun > noun marker > agreement > zero Copula Cycle (Katz) demonstrative > copula > zero third person > copula > zero verb > aspect > copula Noun Cycle (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

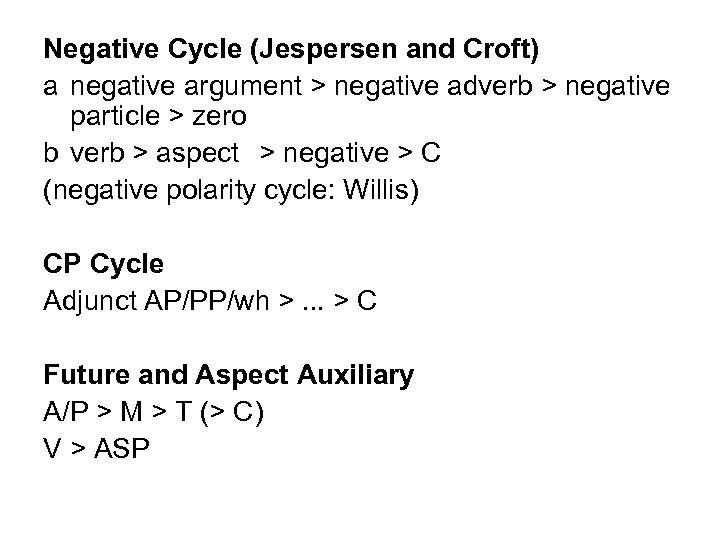

Negative Cycle (Jespersen and Croft) a negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero b verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Cycle Adjunct AP/PP/wh >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

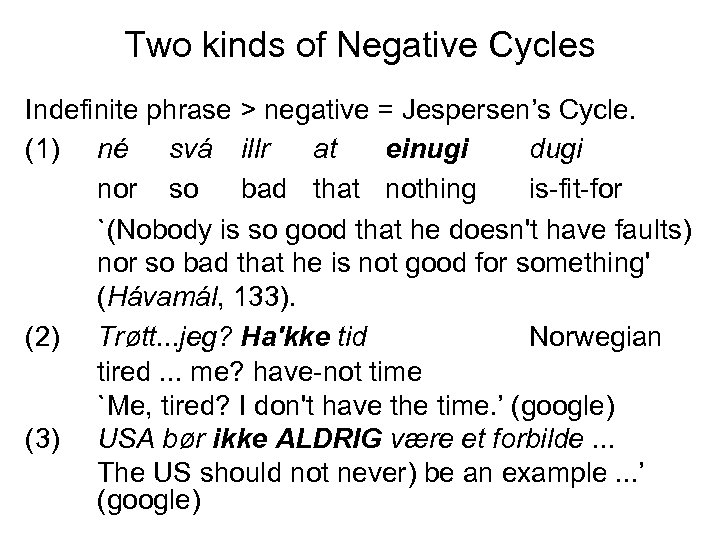

Two kinds of Negative Cycles Indefinite phrase > negative = Jespersen’s Cycle. (1) né svá illr at einugi dugi nor so bad that nothing is-fit-for `(Nobody is so good that he doesn't have faults) nor so bad that he is not good for something' (Hávamál, 133). (2) Trøtt. . . jeg? Ha'kke tid Norwegian tired. . . me? have-not time `Me, tired? I don't have the time. ’ (google) (3) USA bør ikke ALDRIG være et forbilde. . . The US should not never) be an example. . . ’ (google)

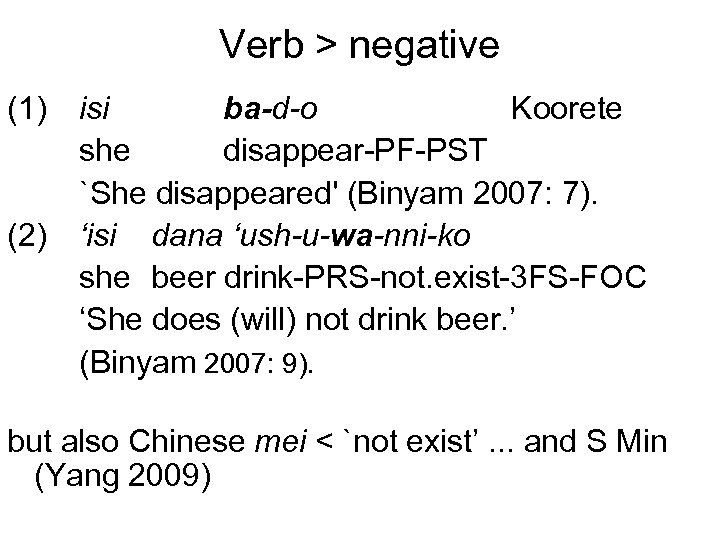

Verb > negative (1) isi ba-d-o Koorete she disappear-PF-PST `She disappeared' (Binyam 2007: 7). (2) ‘isi dana ‘ush-u-wa-nni-ko she beer drink-PRS-not. exist-3 FS-FOC ‘She does (will) not drink beer. ’ (Binyam 2007: 9). but also Chinese mei < `not exist’. . . and S Min (Yang 2009)

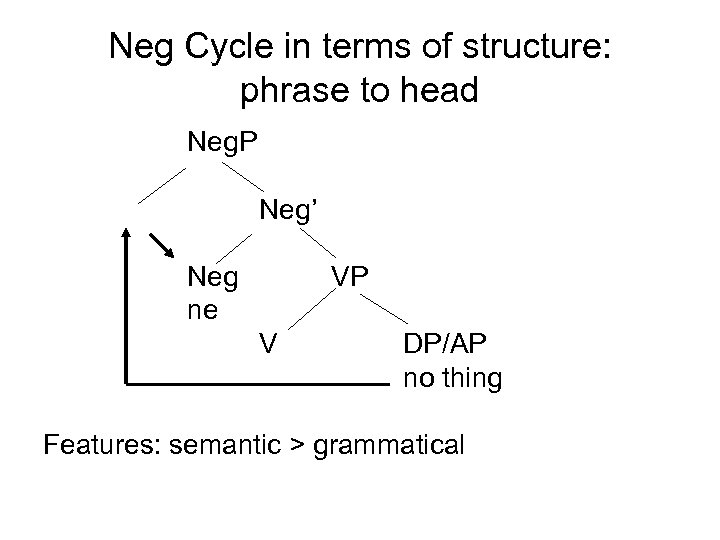

Neg Cycle in terms of structure: phrase to head Neg. P Neg’ Neg ne VP V DP/AP no thing Features: semantic > grammatical

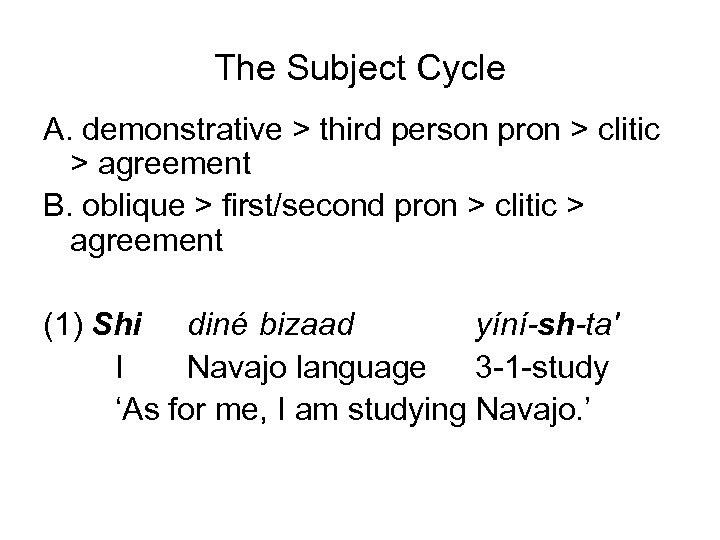

The Subject Cycle A. demonstrative > third person pron > clitic > agreement B. oblique > first/second pron > clitic > agreement (1) Shi diné bizaad yíní-sh-ta' I Navajo language 3 -1 -study ‘As for me, I am studying Navajo. ’

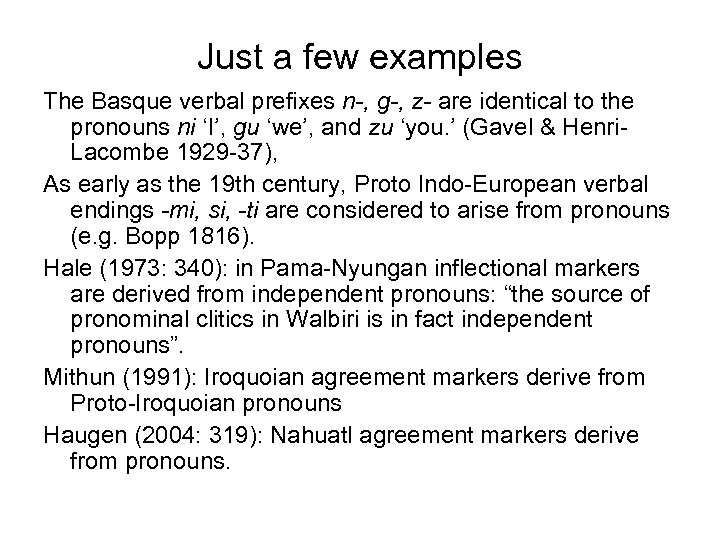

Just a few examples The Basque verbal prefixes n-, g-, z- are identical to the pronouns ni ‘I’, gu ‘we’, and zu ‘you. ’ (Gavel & Henri. Lacombe 1929 -37), As early as the 19 th century, Proto Indo-European verbal endings -mi, si, -ti are considered to arise from pronouns (e. g. Bopp 1816). Hale (1973: 340): in Pama-Nyungan inflectional markers are derived from independent pronouns: “the source of pronominal clitics in Walbiri is in fact independent pronouns”. Mithun (1991): Iroquoian agreement markers derive from Proto-Iroquoian pronouns Haugen (2004: 319): Nahuatl agreement markers derive from pronouns.

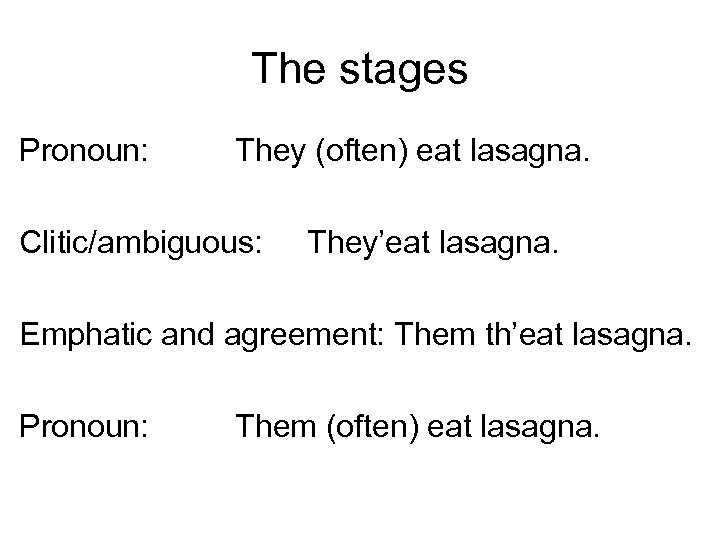

The stages Pronoun: They (often) eat lasagna. Clitic/ambiguous: They’eat lasagna. Emphatic and agreement: Them th’eat lasagna. Pronoun: Them (often) eat lasagna.

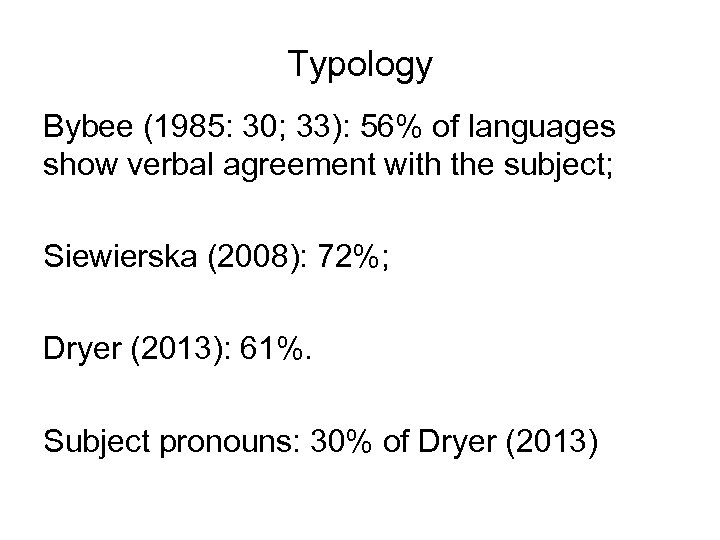

Typology Bybee (1985: 30; 33): 56% of languages show verbal agreement with the subject; Siewierska (2008): 72%; Dryer (2013): 61%. Subject pronouns: 30% of Dryer (2013)

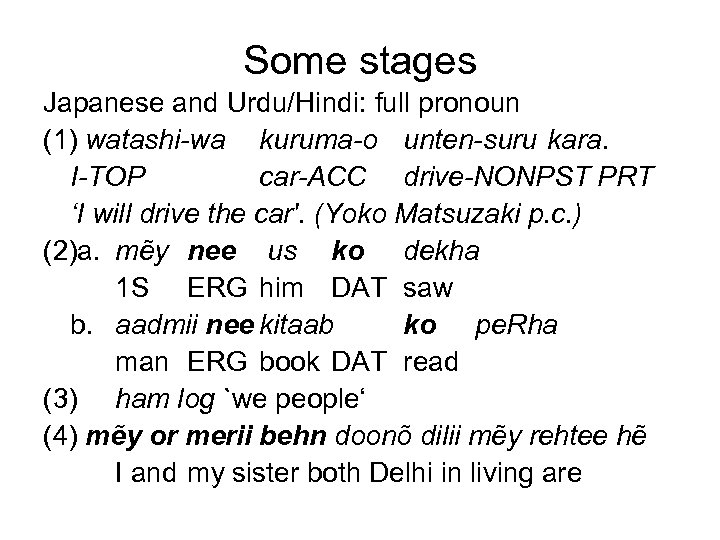

Some stages Japanese and Urdu/Hindi: full pronoun (1) watashi-wa kuruma-o unten-suru kara. I-TOP car-ACC drive-NONPST PRT ‘I will drive the car'. (Yoko Matsuzaki p. c. ) (2)a. mẽy nee us ko dekha 1 S ERG him DAT saw b. aadmii nee kitaab ko pe. Rha man ERG book DAT read (3) ham log `we people‘ (4) mẽy or merii behn doonõ dilii mẽy rehtee hẽ I and my sister both Delhi in living are

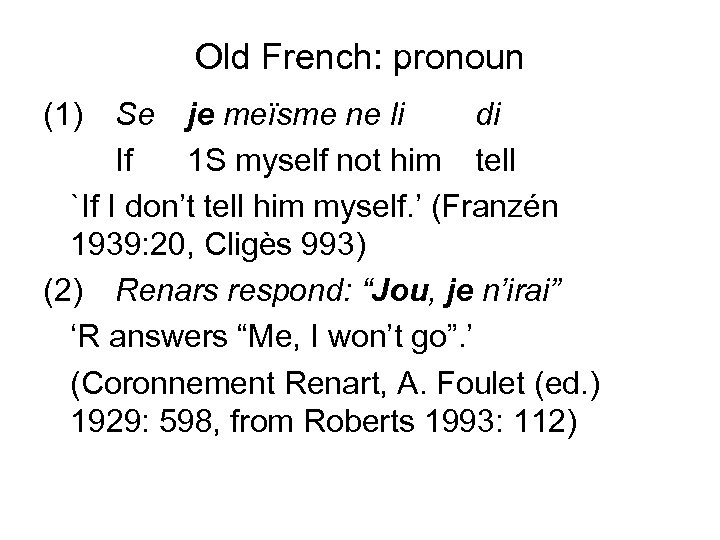

Old French: pronoun (1) Se je meïsme ne li di If 1 S myself not him tell `If I don’t tell him myself. ’ (Franzén 1939: 20, Cligès 993) (2) Renars respond: “Jou, je n’irai” ‘R answers “Me, I won’t go”. ’ (Coronnement Renart, A. Foulet (ed. ) 1929: 598, from Roberts 1993: 112)

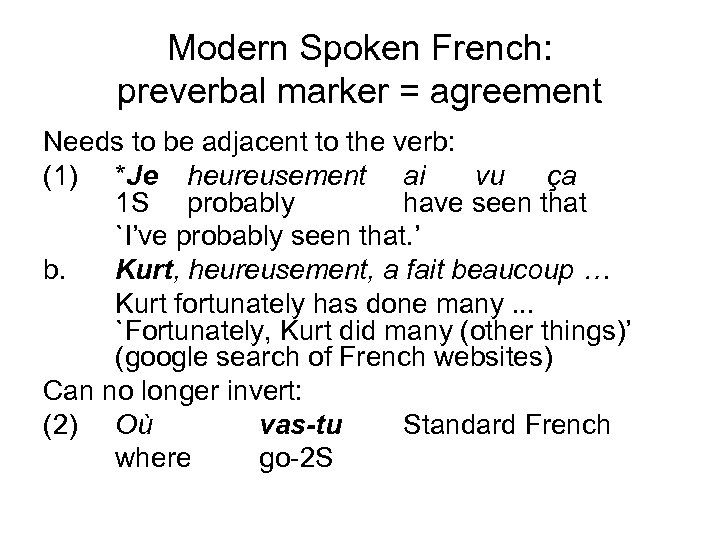

Modern Spoken French: preverbal marker = agreement Needs to be adjacent to the verb: (1) *Je heureusement ai vu ça 1 S probably have seen that `I’ve probably seen that. ’ b. Kurt, heureusement, a fait beaucoup … Kurt fortunately has done many. . . `Fortunately, Kurt did many (other things)’ (google search of French websites) Can no longer invert: (2) Où vas-tu Standard French where go-2 S

More evidence for agreement No inversion: (3) tu vas où Colloquial French 2 S go where ‘Where are you going? ‘ Needs to appear before the verb/aux: (4) Je parle et je mange/*Je parle et mange 1 S speak and 1 S eat

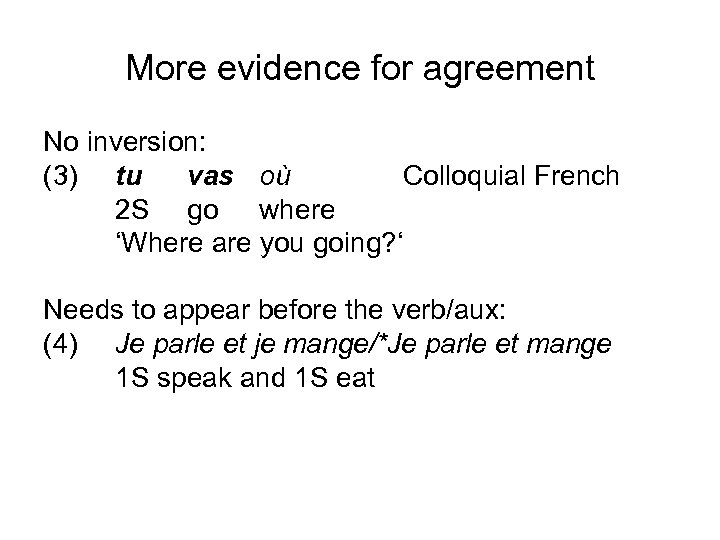

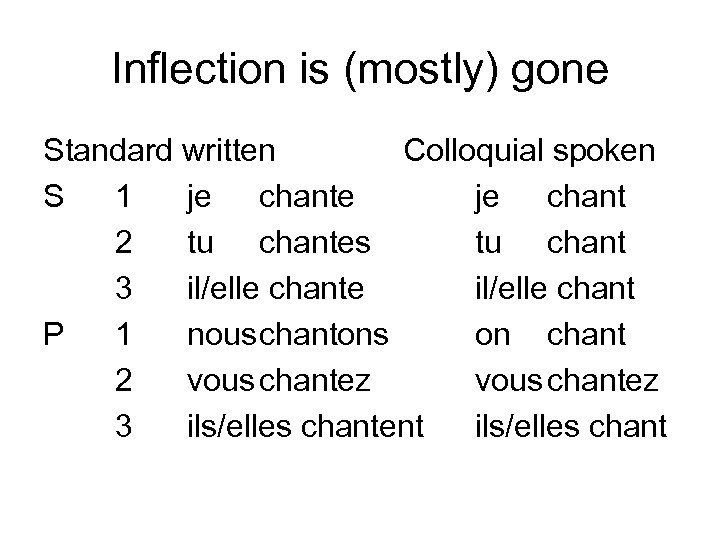

Inflection is (mostly) gone Standard written Colloquial spoken S 1 je chante je chant 2 tu chantes tu chant 3 il/elle chante il/elle chant P 1 nouschantons on chant 2 vous chantez 3 ils/elles chantent ils/elles chant

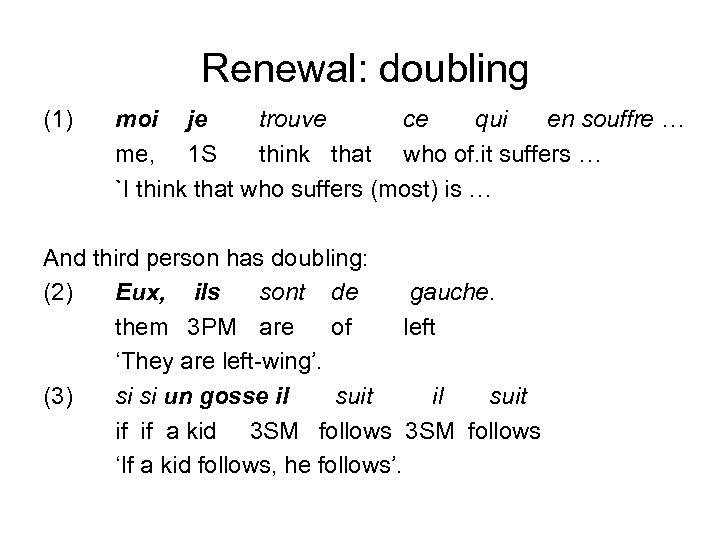

Renewal: doubling (1) moi je trouve ce qui en souffre … me, 1 S think that who of. it suffers … `I think that who suffers (most) is … And third person has doubling: (2) Eux, ils sont de gauche. them 3 PM are of left ‘They are left-wing’. (3) si si un gosse il suit if if a kid 3 SM follows 3 SM follows ‘If a kid follows, he follows’.

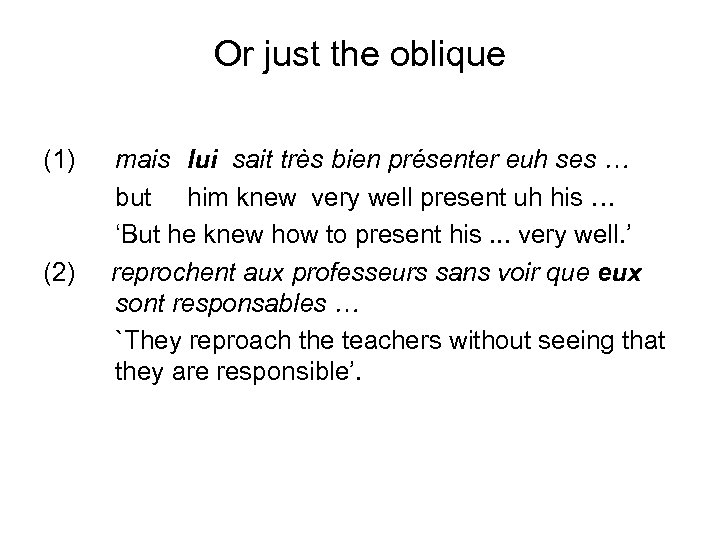

Or just the oblique (1) mais lui sait très bien présenter euh ses … but him knew very well present uh his … ‘But he knew how to present his. . . very well. ’ (2) reprochent aux professeurs sans voir que eux sont responsables … `They reproach the teachers without seeing that they are responsible’.

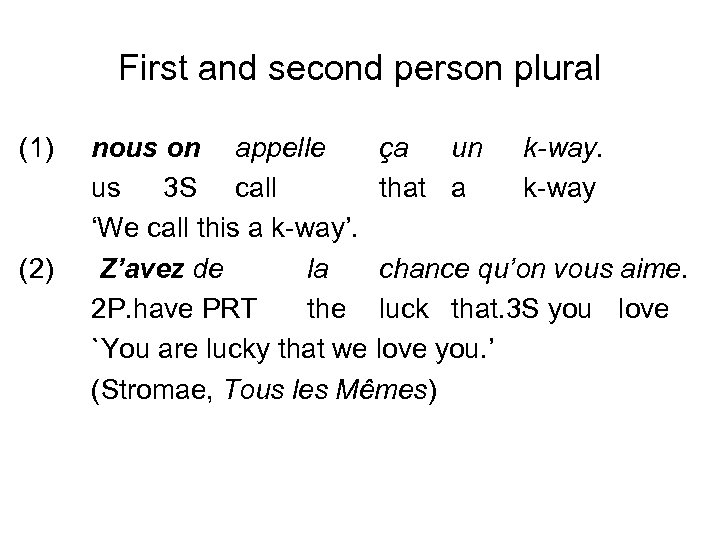

First and second person plural (1) (2) nous on appelle ça un k-way. us 3 S call that a k-way ‘We call this a k-way’. Z’avez de la chance qu’on vous aime. 2 P. have PRT the luck that. 3 S you love `You are lucky that we love you. ’ (Stromae, Tous les Mêmes)

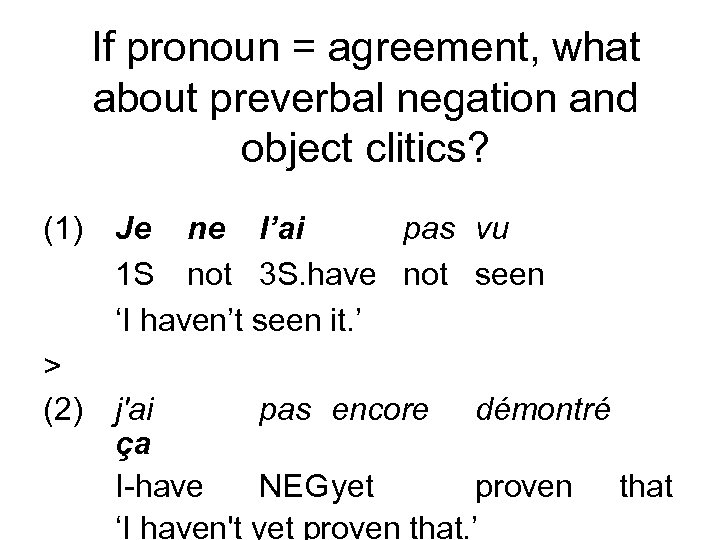

If pronoun = agreement, what about preverbal negation and object clitics? (1) Je ne l’ai pas vu 1 S not 3 S. have not seen ‘I haven’t seen it. ’ > (2) j'ai pas encore démontré ça I-have NEGyet proven that ‘I haven't yet proven that. ’

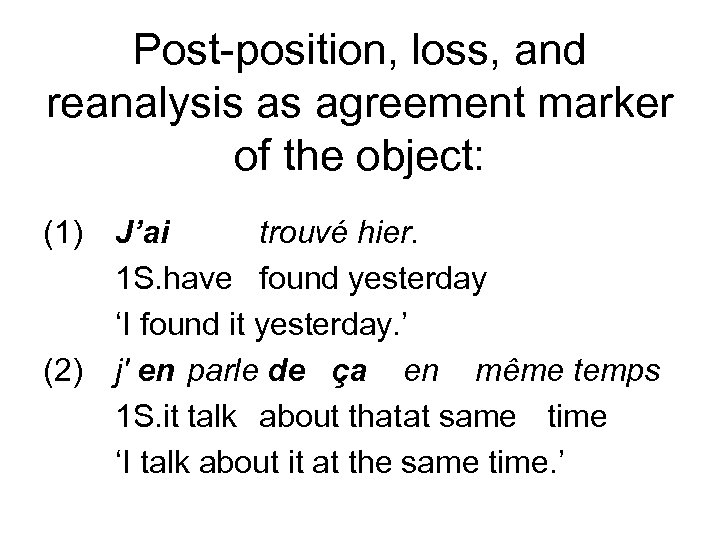

Post-position, loss, and reanalysis as agreement marker of the object: (1) (2) J’ai trouvé hier. 1 S. have found yesterday ‘I found it yesterday. ’ j' en parle de ça en même temps 1 S. it talk about thatat same time ‘I talk about it at the same time. ’

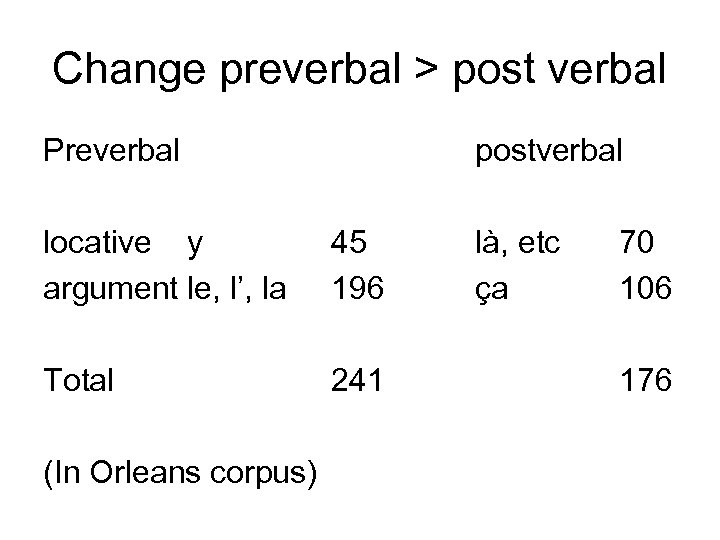

Change preverbal > post verbal Preverbal postverbal locative y argument le, l’, la 45 196 Total 241 (In Orleans corpus) là, etc ça 70 106 176

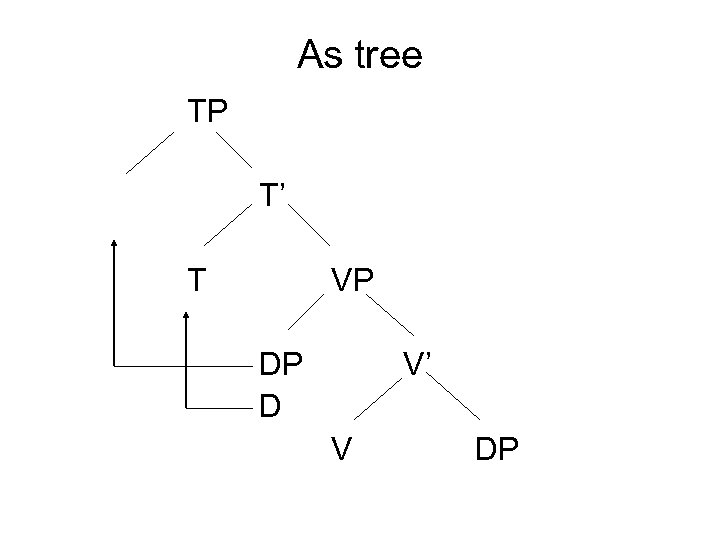

As tree TP T’ T VP DP D V’ V DP

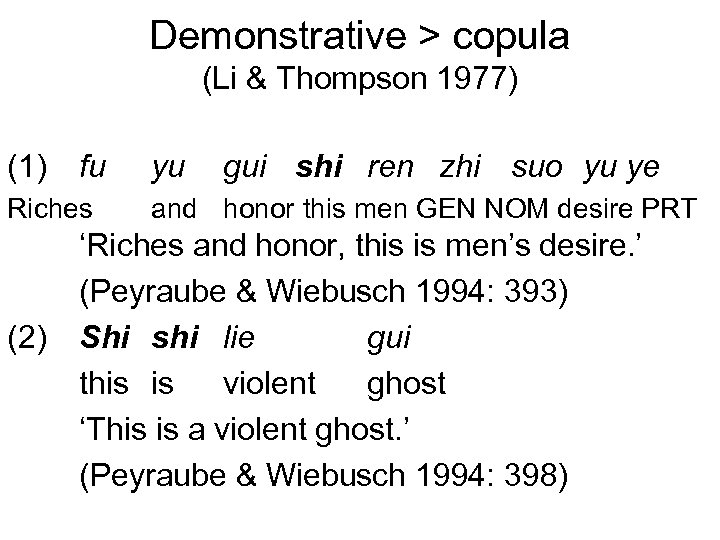

Demonstrative > copula (Li & Thompson 1977) (1) fu yu Riches and honor this men GEN NOM desire PRT (2) gui shi ren zhi suo yu ye ‘Riches and honor, this is men’s desire. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 393) Shi shi lie gui this is violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 398)

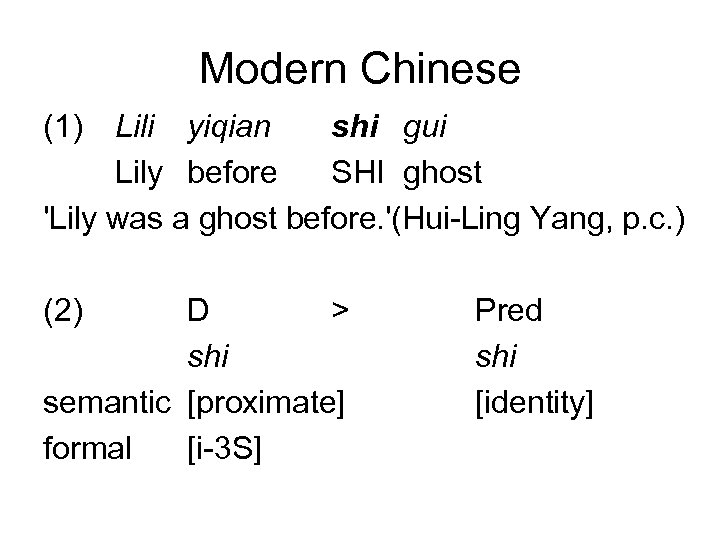

Modern Chinese (1) Lili yiqian shi gui Lily before SHI ghost 'Lily was a ghost before. '(Hui-Ling Yang, p. c. ) (2) D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] Pred shi [identity]

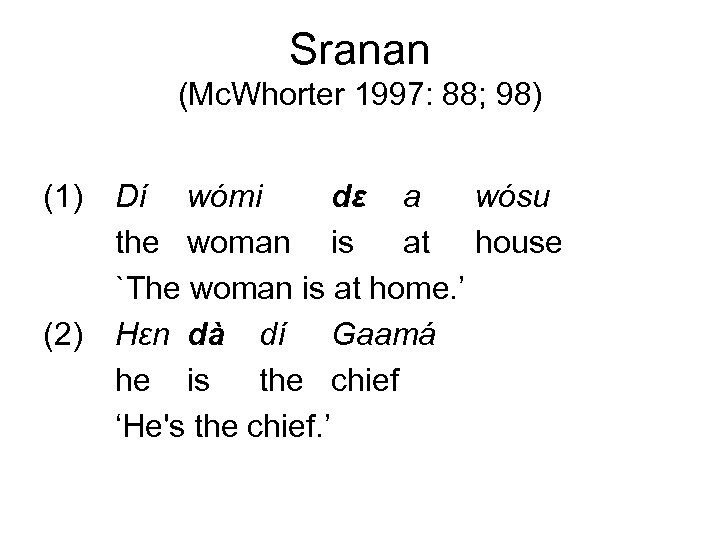

Sranan (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88; 98) (1) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’

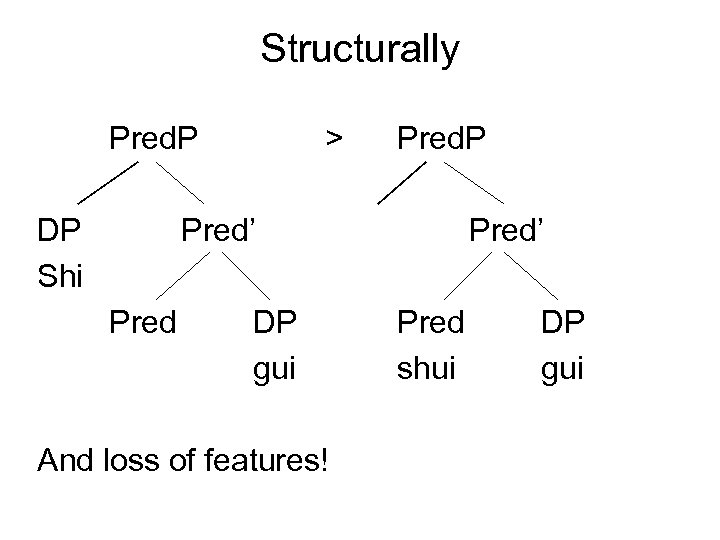

Structurally Pred. P DP Shi > Pred. P Pred’ Pred DP gui And loss of features! Pred’ Pred shui DP gui

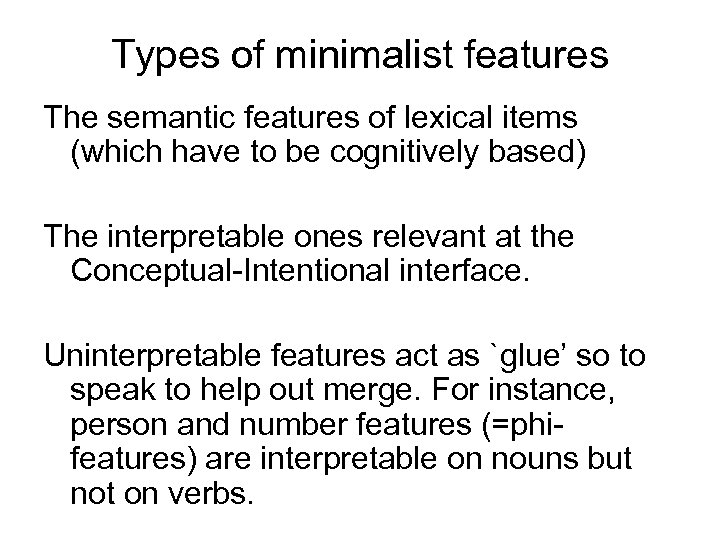

Types of minimalist features The semantic features of lexical items (which have to be cognitively based) The interpretable ones relevant at the Conceptual-Intentional interface. Uninterpretable features act as `glue’ so to speak to help out merge. For instance, person and number features (=phifeatures) are interpretable on nouns but not on verbs.

![with features Emphatic/oblique > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > affix agreement [u-phi] [u-#] Specifier > with features Emphatic/oblique > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > affix agreement [u-phi] [u-#] Specifier >](https://present5.com/presentation/e5b199218a8b095deb76d709f0017821/image-40.jpg)

with features Emphatic/oblique > emphatic/noun [semantic] > > affix agreement [u-phi] [u-#] Specifier > full pronoun [i-phi] Head weak/clitic [u-1/2] [i-3]

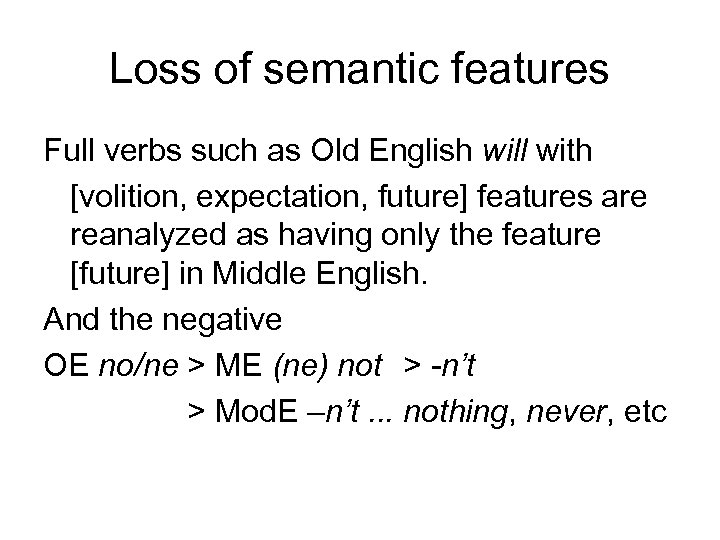

Loss of semantic features Full verbs such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future] features are reanalyzed as having only the feature [future] in Middle English. And the negative OE no/ne > ME (ne) not > -n’t > Mod. E –n’t. . . nothing, never, etc

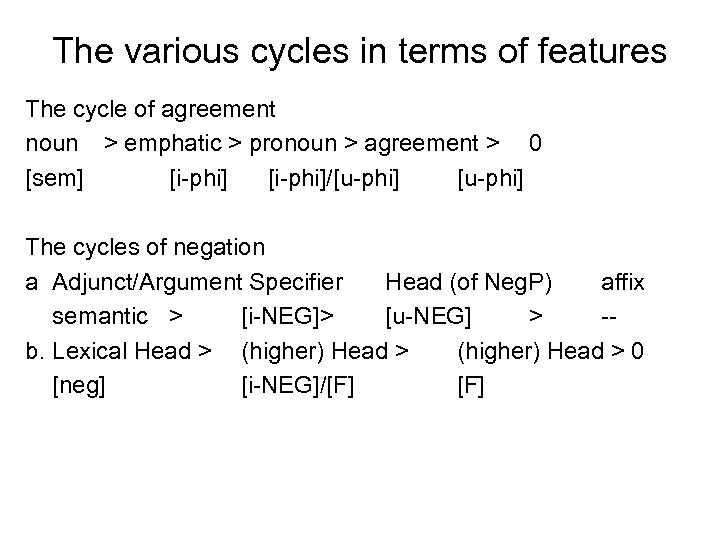

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation a Adjunct/Argument Specifier Head (of Neg. P) affix semantic > [i-NEG]> [u-NEG] > -b. Lexical Head > (higher) Head > 0 [neg] [i-NEG]/[F]

![Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-T] copula [i-loc/id] Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-T] copula [i-loc/id]](https://present5.com/presentation/e5b199218a8b095deb76d709f0017821/image-43.jpg)

Demonstrative [i-phi] [i-loc] article [u-phi] pronoun C [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-T] copula [i-loc/id]

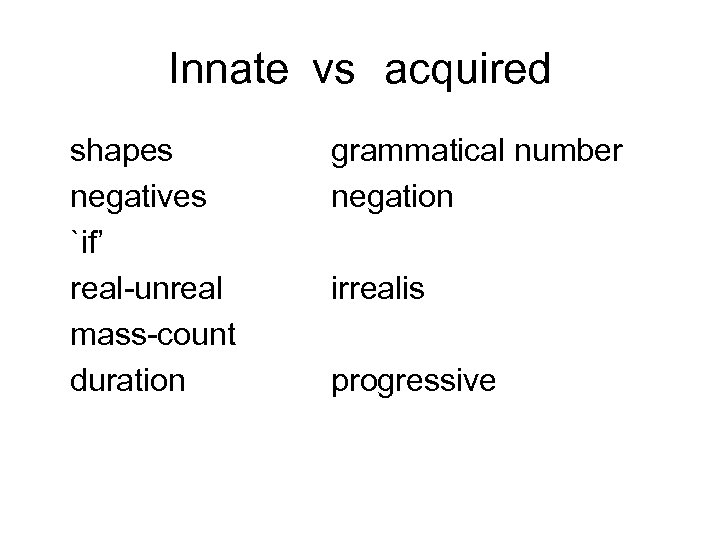

Innate vs acquired shapes negatives `if’ real-unreal mass-count duration grammatical number negation irrealis progressive

Conclusions Cycles is an old idea (Bopp etc). Micro-cycles vs macro-cycles Cycles provide us a window on the language faculty: loss of semantic features and then replacement. They also show structural change.

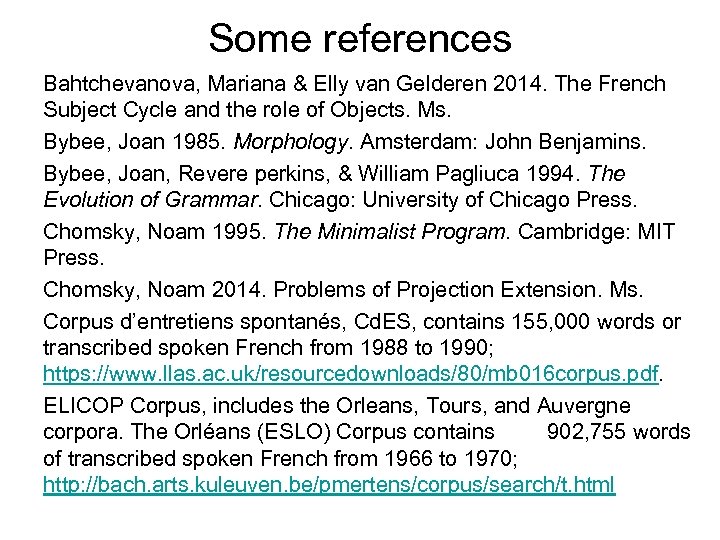

Some references Bahtchevanova, Mariana & Elly van Gelderen 2014. The French Subject Cycle and the role of Objects. Ms. Bybee, Joan 1985. Morphology. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Bybee, Joan, Revere perkins, & William Pagliuca 1994. The Evolution of Grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Chomsky, Noam 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: MIT Press. Chomsky, Noam 2014. Problems of Projection Extension. Ms. Corpus d’entretiens spontanés, Cd. ES, contains 155, 000 words or transcribed spoken French from 1988 to 1990; https: //www. llas. ac. uk/resourcedownloads/80/mb 016 corpus. pdf. ELICOP Corpus, includes the Orleans, Tours, and Auvergne corpora. The Orléans (ESLO) Corpus contains 902, 755 words of transcribed spoken French from 1966 to 1970; http: //bach. arts. kuleuven. be/pmertens/corpus/search/t. html

Fonseca-Greber, Bonnibeth 2000. The Change from Pronoun to Clitic and the Rise of Null Subjects in Spoken Swiss French. University of Arizona Diss. Gabelentz, Georg von der 1891/1901. Die Sprachwissenshaft. Ihre Aufgaben, Methoden und bisherigen Ergebnisse. Leipzig: Weigel. Gelderen, Elly van 2004. Grammaticalization as Economy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Heine, Bernd, Ulrike Claudi, & Friderike Hünnemeyer 1991. Grammaticalization. Chicago. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences: 13: 1 -7. Jespersen, Otto 1922. Language. London: Allen & Unwin. Katz, Aya 1996. Cyclical Grammaticalization and the Cognitive Link between Pronoun and Copula. Rice Dissertation. Lambrecht, Knud 1981. Topic, Antitopic, and Verb Agreement in Non Standard French. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Li, Charles, and Sandra Thompson. (1977). A mechanism for the development of copula morphemes. In Charles Li (ed. ), Mechanisms of syntactic change, 414 -444. Austin: University of Texas Press. Peyraube, Alain & Thekla Wiebusch (1994). Problems relating to the history of different copulas in Ancient Chinese. In Matthew Y. Chen & Ovid J. L. Tseng (eds), In Honor of William S. Y. Wang, 383 -404. Taipei: Pyramid Press. Yang, Hui-Ling 2012. The Grammaticalization of Hakka, Mandarin, Southern Min: The Interaction of Negation with Modality, Aspect and Interrogatives. ASU Diss.

e5b199218a8b095deb76d709f0017821.ppt