969d79bbcbaa6fc5449465bf7575d329.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 43

“The house proposes that we believe that we have sufficient knowledge to prevent a substantial number of people from developing dementia with the right public health interventions Carol Brayne, Director Cambridge Institute of Public Health

Structure • • • Phraseology Concepts Assumptions Evidence Final view

Content of the statement • • • Believe Knowledge Sufficient Substantial Dementia Right public health intervention

We know we can prevent most dementia…

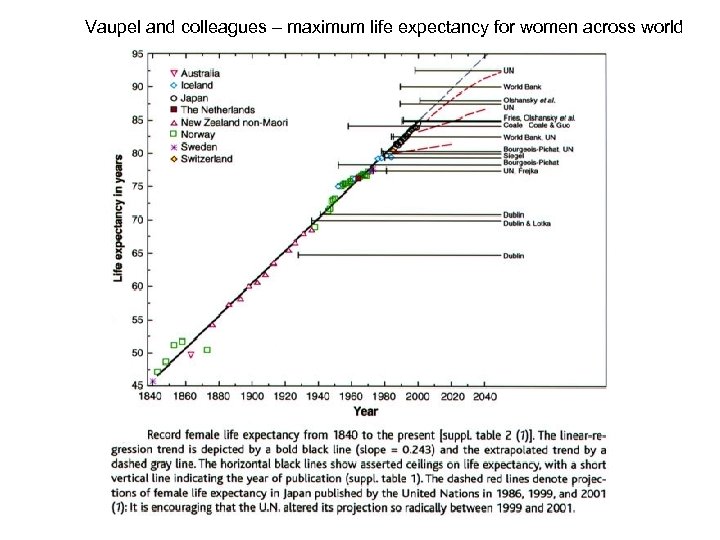

Vaupel and colleagues – maximum life expectancy for women across world

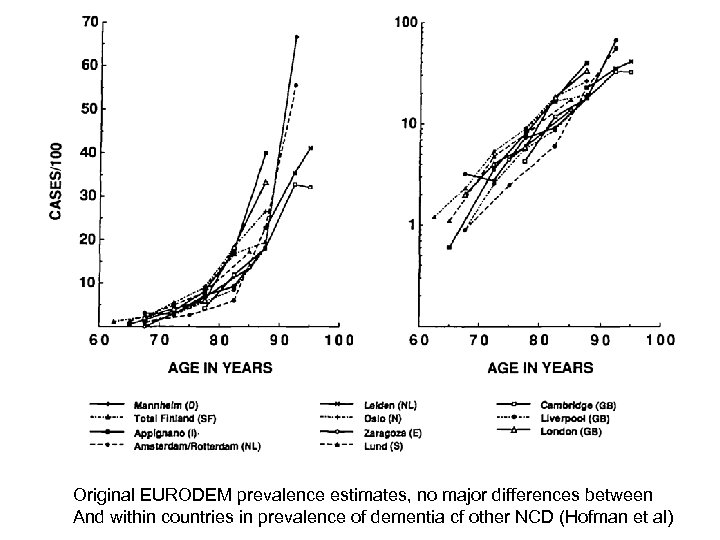

Original EURODEM prevalence estimates, no major differences between And within countries in prevalence of dementia cf other NCD (Hofman et al)

Life expectancy and inequality

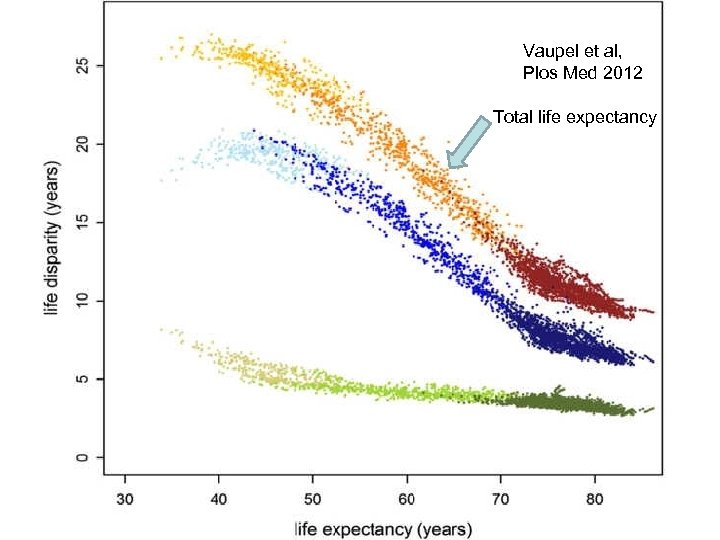

Vaupel et al, Plos Med 2012 Total life expectancy

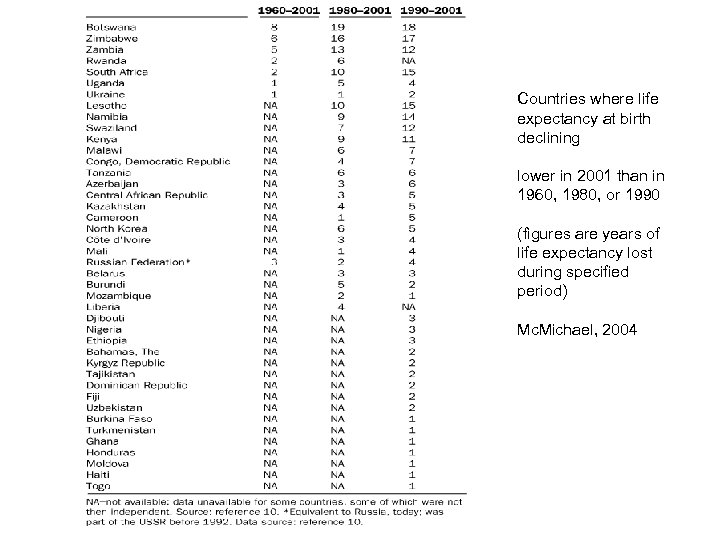

Countries where life expectancy at birth declining lower in 2001 than in 1960, 1980, or 1990 (figures are years of life expectancy lost during specified period) Mc. Michael, 2004

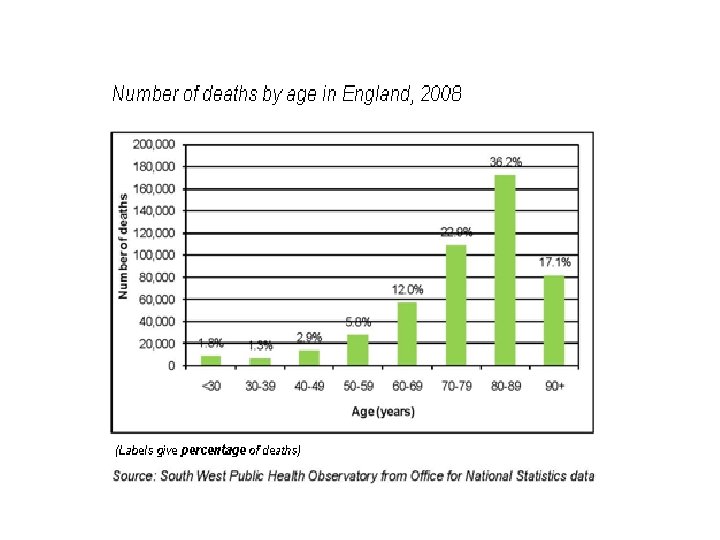

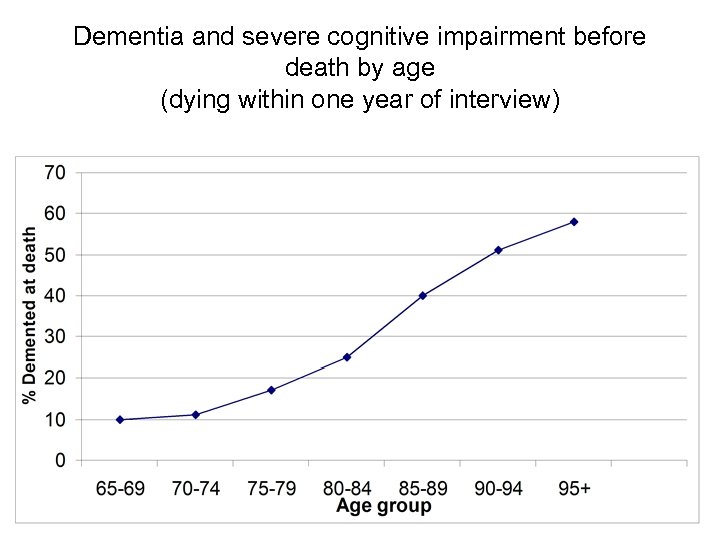

Risk at particular age or risk over a lifetime? • What is it that most older people fear? • Dementia occurring during their life • What is the age profile of deaths in western countries • What is the prevalence of dementia at death?

Dementia and severe cognitive impairment before death by age (dying within one year of interview)

On whom and where most of our dementia research conducted?

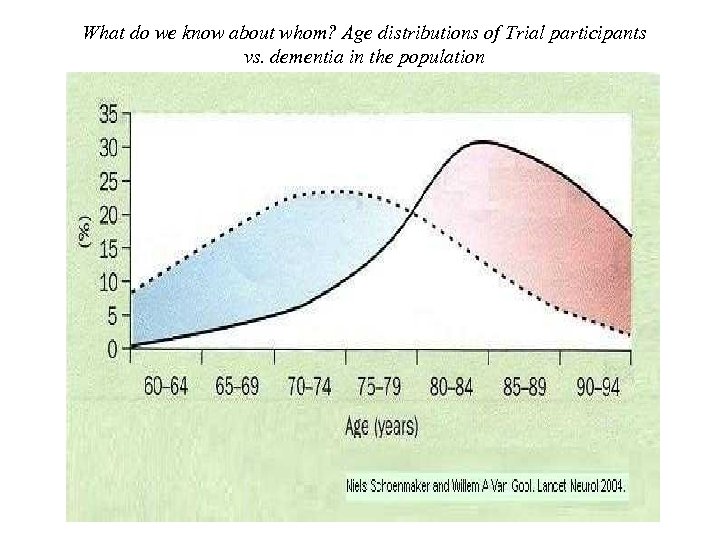

What do we know about whom? Age distributions of Trial participants vs. dementia in the population

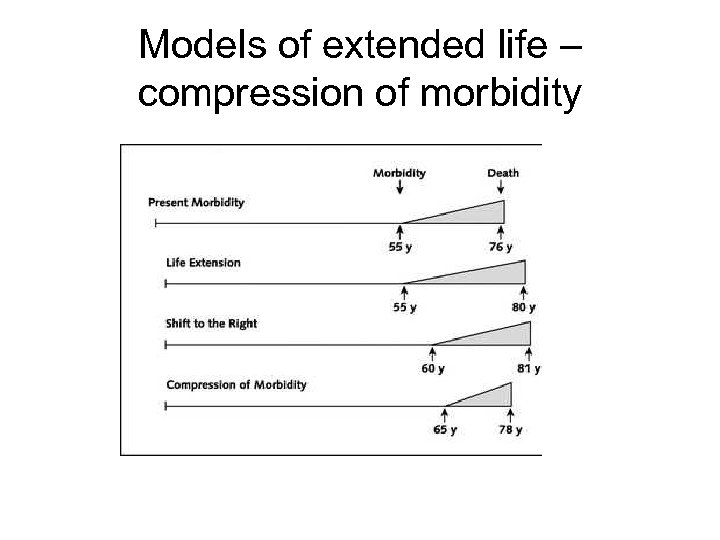

Models of extended life – compression of morbidity

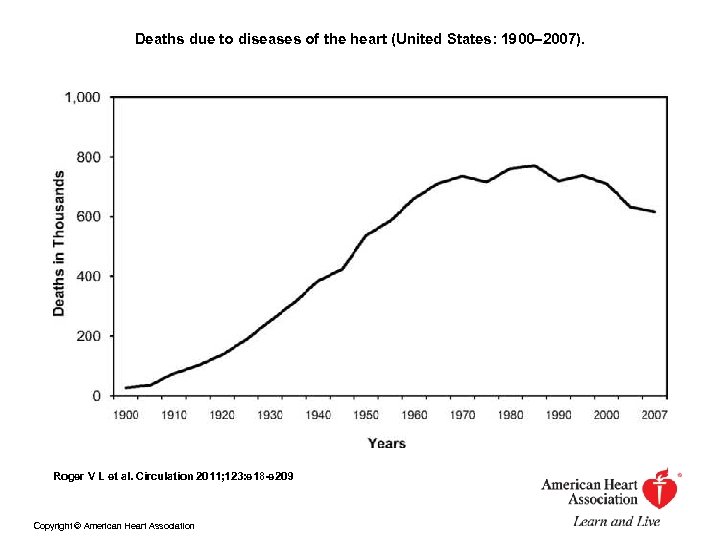

How has life expectancy been extended? • Early due to public health interventions • Latterly to do with reductions in mortality from chronic disease. . • Example of cardiovascular disease

Deaths due to diseases of the heart (United States: 1900– 2007). Roger V L et al. Circulation 2011; 123: e 18 -e 209 Copyright © American Heart Association

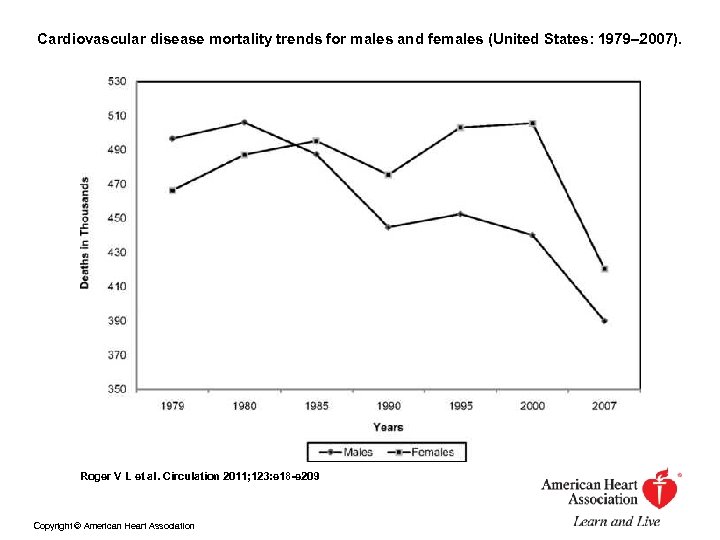

Cardiovascular disease mortality trends for males and females (United States: 1979– 2007). Roger V L et al. Circulation 2011; 123: e 18 -e 209 Copyright © American Heart Association

But not eradicated, but shifted. .

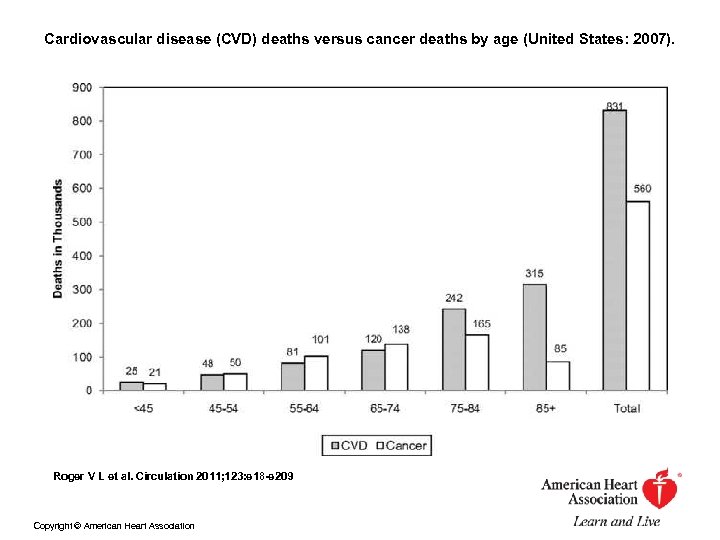

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths versus cancer deaths by age (United States: 2007). Roger V L et al. Circulation 2011; 123: e 18 -e 209 Copyright © American Heart Association

• Similar changes in stroke • BUT increased survival…. models of prevention

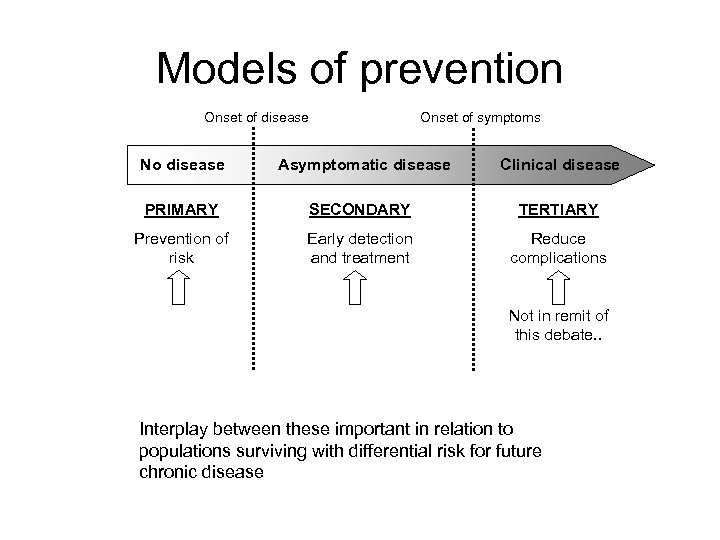

Models of prevention Onset of disease Onset of symptoms No disease Asymptomatic disease Clinical disease PRIMARY SECONDARY TERTIARY Prevention of risk Early detection and treatment Reduce complications Not in remit of this debate. . Interplay between these important in relation to populations surviving with differential risk for future chronic disease

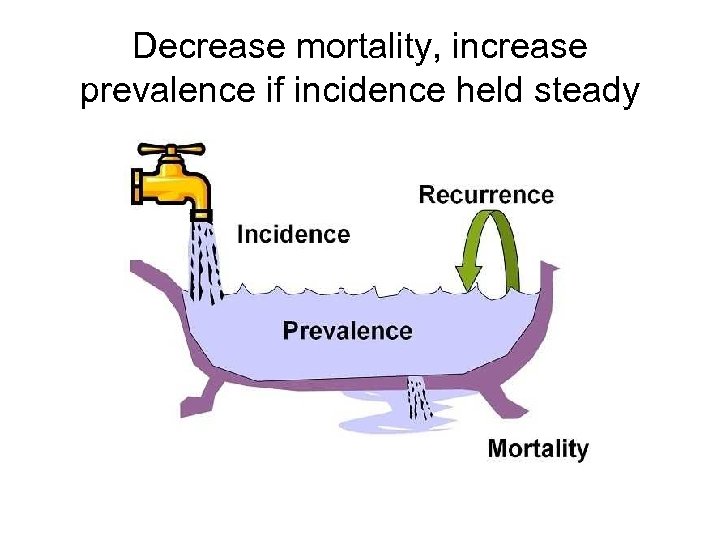

Decrease mortality, increase prevalence if incidence held steady

What about screening as a model for prevention?

The ‘Great Prostate Mistake’. . lack of understanding of ageing and prostate cancer, and the application of a poor screening test has led, believe many, to over-treatment, harm and great expense… Ablin RA. The Great Prostate Mistake. The New York Times. 10 March 2010

So back to primary prevention

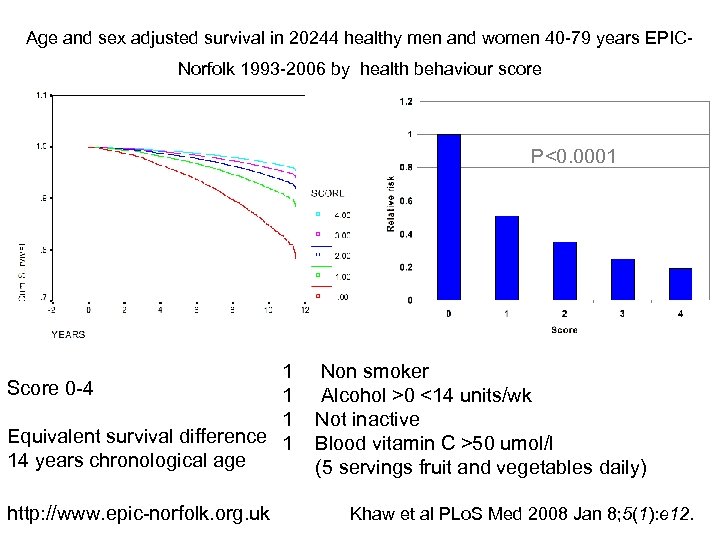

Age and sex adjusted survival in 20244 healthy men and women 40 -79 years EPICNorfolk 1993 -2006 by health behaviour score P<0. 0001 1 Score 0 -4 1 1 Equivalent survival difference 1 14 years chronological age http: //www. epic-norfolk. org. uk Non smoker Alcohol >0 <14 units/wk Not inactive Blood vitamin C >50 umol/l (5 servings fruit and vegetables daily) Khaw et al PLo. S Med 2008 Jan 8; 5(1): e 12.

Diet Usual suspects for NCDs: diet, physical activity, vascular risk. .

But risk is more complicated. . • • Lifecourse profiles Blood pressure consistently related to dementia At what age does risk need to be changed? Lack of compelling evidence from prevention trials addressing risk at later ages so far • Even encouraging results sometimes result of publication bias (see Clarke et al, Plo. S Medicine 2012)

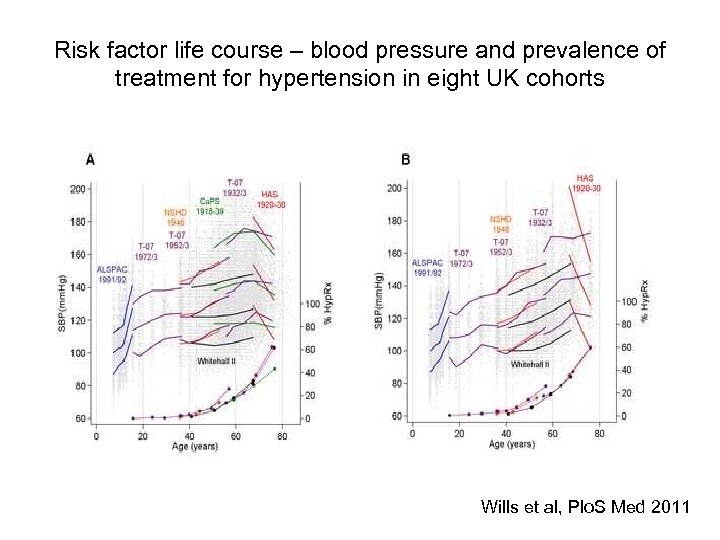

Risk factor life course – blood pressure and prevalence of treatment for hypertension in eight UK cohorts Wills et al, Plo. S Med 2011

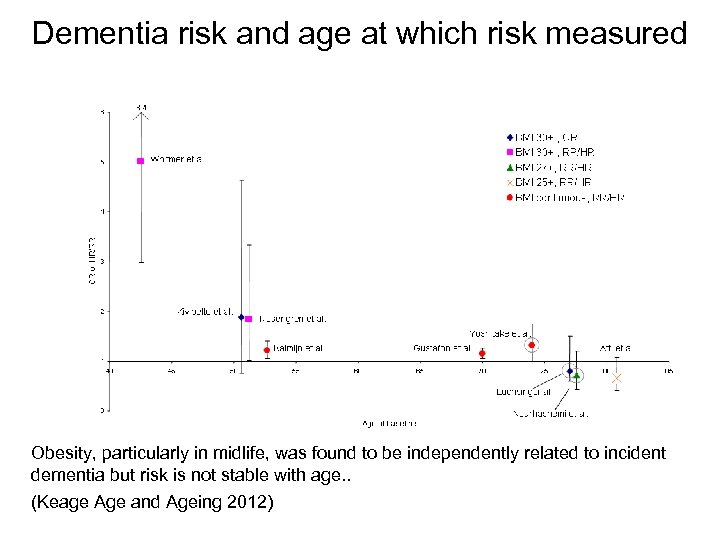

Dementia risk and age at which risk measured Obesity, particularly in midlife, was found to be independently related to incident dementia but risk is not stable with age. . (Keage Age and Ageing 2012)

Moving from risk to protection and compensation - evidence

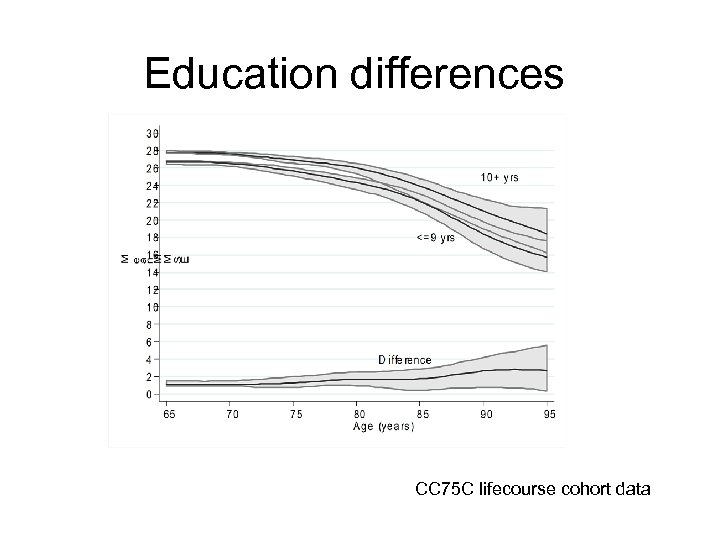

Education differences CC 75 C lifecourse cohort data

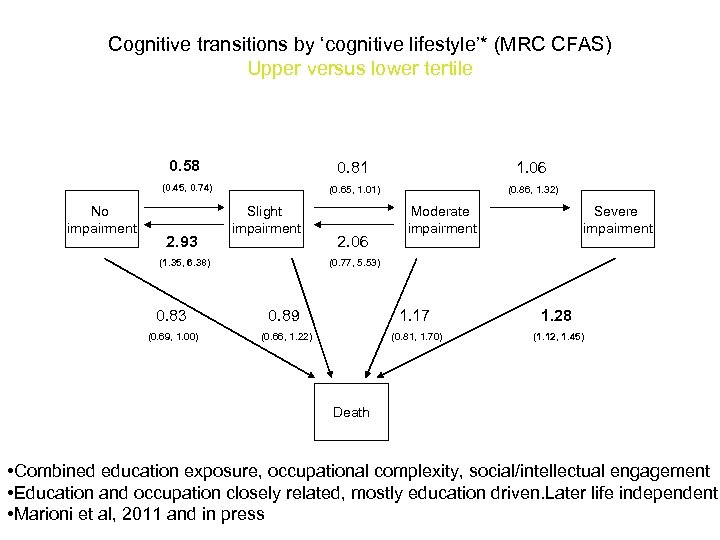

Cognitive transitions by ‘cognitive lifestyle’* (MRC CFAS) Upper versus lower tertile 0. 58 1. 06 (0. 45, 0. 74) No impairment 0. 81 (0. 65, 1. 01) (0. 86, 1. 32) 2. 93 Slight impairment (1. 35, 6. 38) 2. 06 Moderate impairment Severe impairment (0. 77, 5. 53) 0. 83 0. 89 1. 17 1. 28 (0. 69, 1. 00) (0. 66, 1. 22) (0. 81, 1. 70) (1. 12, 1. 45) Death • Combined education exposure, occupational complexity, social/intellectual engagement • Education and occupation closely related, mostly education driven. Later life independent • Marioni et al, 2011 and in press

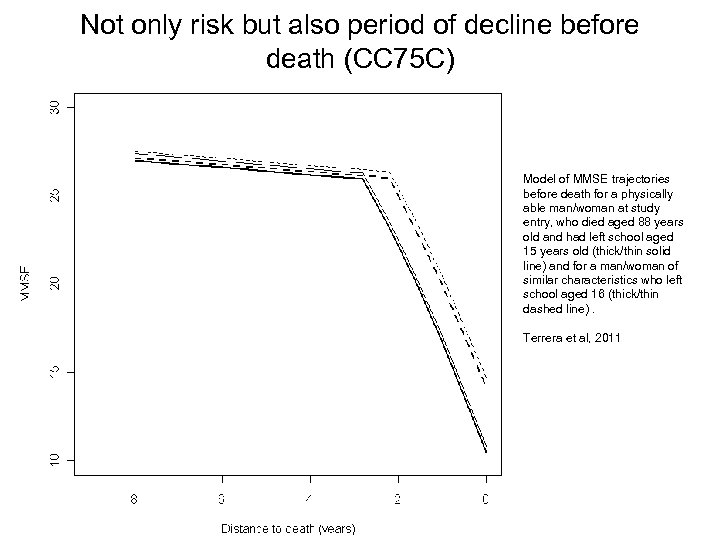

Not only risk but also period of decline before death (CC 75 C) Model of MMSE trajectories before death for a physically able man/woman at study entry, who died aged 88 years old and had left school aged 15 years old (thick/thin solid line) and for a man/woman of similar characteristics who left school aged 16 (thick/thin dashed line). Terrera et al, 2011

Prevalence of dementia at death by educational level (MRC CFAS) Brayne et al, PLo. S Med 2006

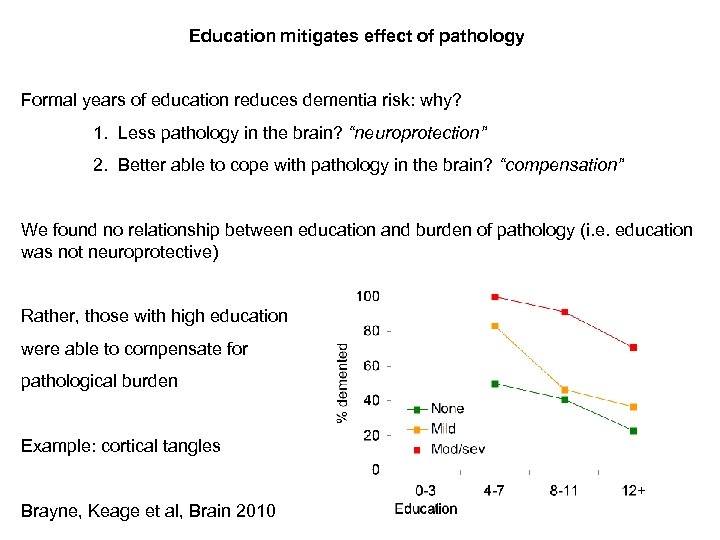

Education mitigates effect of pathology Formal years of education reduces dementia risk: why? 1. Less pathology in the brain? “neuroprotection” 2. Better able to cope with pathology in the brain? “compensation” We found no relationship between education and burden of pathology (i. e. education was not neuroprotective) Rather, those with high education were able to compensate for pathological burden Example: cortical tangles Brayne, Keage et al, Brain 2010

Future scenarios (UK) – cog impaired population where to invest our limited resources? A micro-simulation approach? Percent increase over current levels with different approaches to prevention Jagger et al Age & Ageing 2009

Disconnection between actual evidence and the ‘message’ • Public health is about whole populations, whole lifespan, lessons from past, present situation and likely future • How robust is the evidence? • Research findings often overhyped, and publication bias not taken into account • The gaps in evidence should identified and lead to well designed and sufficiently powerful research • Action should be based on robust evidence or, if not, acknowledge it is based on belief at this stage (as by Burns, 2012) • Change in paradigm – optimise quality of life accepting ageing over lifecourse, reduce risk where we can and have evidence how to • Recognise that resources spent on ineffective practices will reduce resource for other areas including those living with dementia • Accept we are all going to die and most of those who die at older ages will have some terminal decline with some degree of cognitive impairment at the end of life

Public health evidence • Population level action is more cost effective than individually based interventions • This can be societal or legislative • Nudge has limited evidence despite its popularity (Marteau et al, BMJ 2011) • Individually based evidence emerging for small effects from trials, largely on cognition not dementia and over fixed time periods • There IS compelling evidence for prevention of the upstream NCDs for which action is largely clear and already happening • That brain health may benefit is already included in much health messaging • Given limited resources investment in individually based prevention before compelling trial evidence not warranted • Any such resources would be better targetted upstream for lifelong, proven, beneficial effects and to care • But also critical to test whether it is possible • Expand on current trial work

…. . “almost half a billion children are at risk of permanent damage over the next 15 years”. (Save the Children’s 2012 report) • 1 in 3 of the world’s children are stunted • Body and brain will have failed to develop properly because of malnutrition. • There have to be priorities, • National and International policy makers have to decide for whole populations • They need us to give dispassionate robust and unbiased evidence, not belief • Why – because not to do so will divert resources away from proven need and proven benefit

“The house proposes that we believe that we have sufficient knowledge to prevent a substantial number of people from developing dementia with the right public health interventions Carol Brayne, Director Cambridge Institute of Public Health

Thanks • To you for your attention • To colleagues, research contributors, participants and families for all the studies I have drawn on for this presentation

969d79bbcbaa6fc5449465bf7575d329.ppt