0f826dd3b76f935962af2aa96036342f.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 84

The crucial role of physical activity in the prevention and management of overweight and obesity Dunedin, New Zealand February 1, 2010 Steven N. Blair sblair@mailbox. sc. edu Departments of Exercise Science & Epidemiology/Biostatistics University of South Carolina

The crucial role of physical activity in the prevention and management of overweight and obesity Dunedin, New Zealand February 1, 2010 Steven N. Blair sblair@mailbox. sc. edu Departments of Exercise Science & Epidemiology/Biostatistics University of South Carolina

• Fewer • Pressure meals at to be home sedentary • Society of spectators instead of participant • Pressure to consume • Eating as g on recreation the run • Powerful and constant advertising Social Environment Building design Urban sprawl Absence of Pollutants sidewalks Population Automobile density dependency Energy Intake Genetic Predisposition Calorie- Maternal. Behavior dense fetal foods nutrition Smoking cessation More sedentarism Less physical activity Corn fructose syrup Lactation High fat Larger portions diets Certain medications Physical Environment Nutrient / Energy Obesity Partitioning Overweig ht Energy Expenditur Adipogenesis e Thermogenesis n-6/n-3 PUFAs Genetic CNS regulators of appetite: NPY, hypotheses a-MSH, CART, Orexins, Agouti, Lipid ox Viruses RMR MC 4 R, MCH, AGRP, etc. Epigenetics Regulators of adipogenesis: Peripheral regulators of RAR, RXR, PPARg, C/EBP, appetite: PYY, insulin, leptin, SREBP-1 c, PGC-1, etc. ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, etc. Biology

• Fewer • Pressure meals at to be home sedentary • Society of spectators instead of participant • Pressure to consume • Eating as g on recreation the run • Powerful and constant advertising Social Environment Building design Urban sprawl Absence of Pollutants sidewalks Population Automobile density dependency Energy Intake Genetic Predisposition Calorie- Maternal. Behavior dense fetal foods nutrition Smoking cessation More sedentarism Less physical activity Corn fructose syrup Lactation High fat Larger portions diets Certain medications Physical Environment Nutrient / Energy Obesity Partitioning Overweig ht Energy Expenditur Adipogenesis e Thermogenesis n-6/n-3 PUFAs Genetic CNS regulators of appetite: NPY, hypotheses a-MSH, CART, Orexins, Agouti, Lipid ox Viruses RMR MC 4 R, MCH, AGRP, etc. Epigenetics Regulators of adipogenesis: Peripheral regulators of RAR, RXR, PPARg, C/EBP, appetite: PYY, insulin, leptin, SREBP-1 c, PGC-1, etc. ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, etc. Biology

Overview of Lecture • Crucial role of physical activity and fitness to health outcome • Physical activity and weight management – Physical activity and prevention of weight gain – Physical activity and weight loss – Physical activity and the prevention of weight regain

Overview of Lecture • Crucial role of physical activity and fitness to health outcome • Physical activity and weight management – Physical activity and prevention of weight gain – Physical activity and weight loss – Physical activity and the prevention of weight regain

Leading Causes of Death in the World Risk Factor Deaths (millions) % of total deaths Hypertension 7. 5 12. 8 Tobacco use 5. 1 8. 7 High blood glucose 3. 4 5. 8 Physical inactivity 3. 2 5. 5 Overweight/obesity 2. 8 4. 8 WHO. Global Health Risks. 2009.

Leading Causes of Death in the World Risk Factor Deaths (millions) % of total deaths Hypertension 7. 5 12. 8 Tobacco use 5. 1 8. 7 High blood glucose 3. 4 5. 8 Physical inactivity 3. 2 5. 5 Overweight/obesity 2. 8 4. 8 WHO. Global Health Risks. 2009.

Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study

Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study

Design of the ACLS 1970 More than 80, 000 patients 2005 Cooper Clinic examinations--including history and physical exam, clinical tests, body composition, EBT, and CRF Mortality surveillance to 2003 More than 4000 deaths 1982 ‘ 86 ‘ 90 ‘ 95 ’ 99 ‘ 04 Mail-back surveys for case finding and monitoring habits and other characteristics

Design of the ACLS 1970 More than 80, 000 patients 2005 Cooper Clinic examinations--including history and physical exam, clinical tests, body composition, EBT, and CRF Mortality surveillance to 2003 More than 4000 deaths 1982 ‘ 86 ‘ 90 ‘ 95 ’ 99 ‘ 04 Mail-back surveys for case finding and monitoring habits and other characteristics

All-Cause Death Rates by CRF Categories— 3120 Women and 10 224 Men—ACLS Blair SN. JAMA 1989

All-Cause Death Rates by CRF Categories— 3120 Women and 10 224 Men—ACLS Blair SN. JAMA 1989

Amount of Specific Physical Activities for Moderately Fit Women and Men • Detailed physical activity assessments Mean Min/week in women and men who also completed a maximal exercise test • Average min/week for the moderately fit who only reported each specific activity Stofan JR et al. AJPH 1998; 88: 1807 N=3, 972 13, 444

Amount of Specific Physical Activities for Moderately Fit Women and Men • Detailed physical activity assessments Mean Min/week in women and men who also completed a maximal exercise test • Average min/week for the moderately fit who only reported each specific activity Stofan JR et al. AJPH 1998; 88: 1807 N=3, 972 13, 444

Death Rates and RR for Selected Mortality Predictors, Men, ACLS Death rates and relative risks are adjusted for age and examination year Relative risks are for risk categories shown here compared with those not at risk on that predictor Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

Death Rates and RR for Selected Mortality Predictors, Men, ACLS Death rates and relative risks are adjusted for age and examination year Relative risks are for risk categories shown here compared with those not at risk on that predictor Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

Death Rates and RR for Selected Mortality Predictors, Women, ACLS Death rates and relative risks are adjusted for age and examination year Relative risks are for risk categories shown here compared with those not at risk on that predictor Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

Death Rates and RR for Selected Mortality Predictors, Women, ACLS Death rates and relative risks are adjusted for age and examination year Relative risks are for risk categories shown here compared with those not at risk on that predictor Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

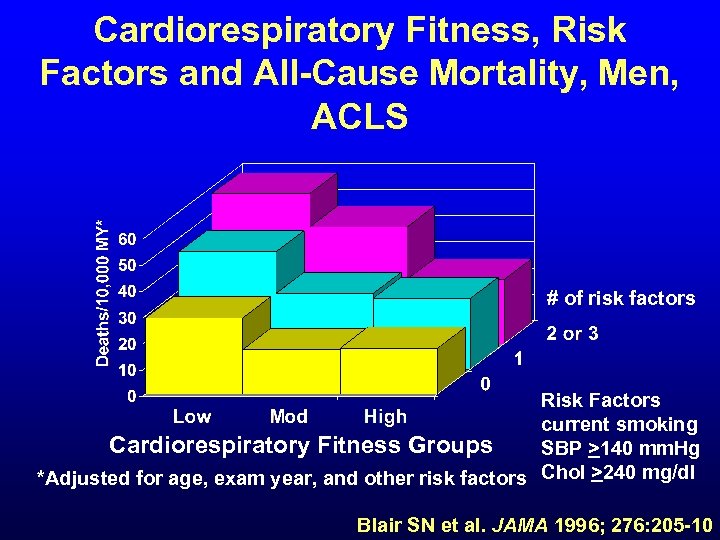

Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Risk Factors and All-Cause Mortality, Men, ACLS # of risk factors Risk Factors current smoking Cardiorespiratory Fitness Groups SBP >140 mm. Hg *Adjusted for age, exam year, and other risk factors Chol >240 mg/dl Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

Cardiorespiratory Fitness, Risk Factors and All-Cause Mortality, Men, ACLS # of risk factors Risk Factors current smoking Cardiorespiratory Fitness Groups SBP >140 mm. Hg *Adjusted for age, exam year, and other risk factors Chol >240 mg/dl Blair SN et al. JAMA 1996; 276: 205 -10

CRF and Digestive System Cancer Mortality • 38, 801 men, ages 20 -88 years • 283 digestive system cancer deaths in 17 years of followup CRF was inversely associated with death after adjustment for age, examination year, body mass index, smoking, drinking, family history of cancer, personal history of diabetes • Fit men had lower risk of colon, colorectal, and liver cancer deaths High Fit Moderately Fit Low Fit Peel JB et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 1111

CRF and Digestive System Cancer Mortality • 38, 801 men, ages 20 -88 years • 283 digestive system cancer deaths in 17 years of followup CRF was inversely associated with death after adjustment for age, examination year, body mass index, smoking, drinking, family history of cancer, personal history of diabetes • Fit men had lower risk of colon, colorectal, and liver cancer deaths High Fit Moderately Fit Low Fit Peel JB et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 1111

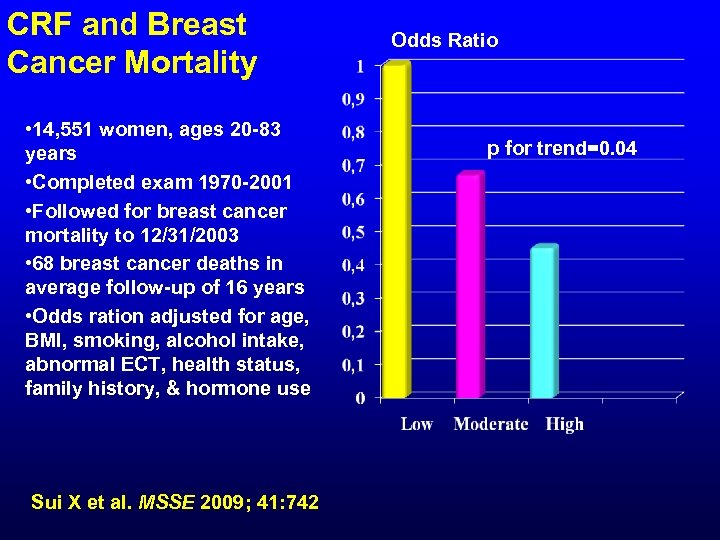

CRF and Breast Cancer Mortality • 14, 551 women, ages 20 -83 years • Completed exam 1970 -2001 • Followed for breast cancer mortality to 12/31/2003 • 68 breast cancer deaths in average follow-up of 16 years • Odds ration adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, abnormal ECT, health status, family history, & hormone use Sui X et al. MSSE 2009; 41: 742 Odds Ratio p for trend=0. 04

CRF and Breast Cancer Mortality • 14, 551 women, ages 20 -83 years • Completed exam 1970 -2001 • Followed for breast cancer mortality to 12/31/2003 • 68 breast cancer deaths in average follow-up of 16 years • Odds ration adjusted for age, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, abnormal ECT, health status, family history, & hormone use Sui X et al. MSSE 2009; 41: 742 Odds Ratio p for trend=0. 04

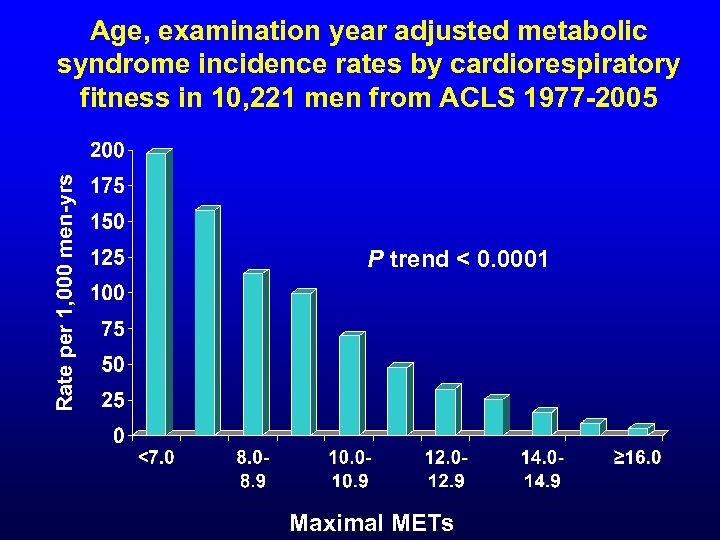

Age, examination year adjusted metabolic syndrome incidence rates by cardiorespiratory fitness in 10, 221 men from ACLS 1977 -2005 P trend < 0. 0001 Maximal METs

Age, examination year adjusted metabolic syndrome incidence rates by cardiorespiratory fitness in 10, 221 men from ACLS 1977 -2005 P trend < 0. 0001 Maximal METs

Activity, Fitness, and Mortality in Older Adults

Activity, Fitness, and Mortality in Older Adults

Cardiorespiratory Fitness and All-Cause Mortality, Women and Men ≥ 60 Years of Age • 4060 women and men ≤ 60 years • 989 died during ~14 years of follow-up • ~25% were women • Death rates adjusted for age, sex, and exam year All-Cause death rates/1, 000 PY Age Groups Sui M et al. JAGS 2007.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness and All-Cause Mortality, Women and Men ≥ 60 Years of Age • 4060 women and men ≤ 60 years • 989 died during ~14 years of follow-up • ~25% were women • Death rates adjusted for age, sex, and exam year All-Cause death rates/1, 000 PY Age Groups Sui M et al. JAGS 2007.

We will all die eventually, but Who wants to spend their last years in a nursing home?

We will all die eventually, but Who wants to spend their last years in a nursing home?

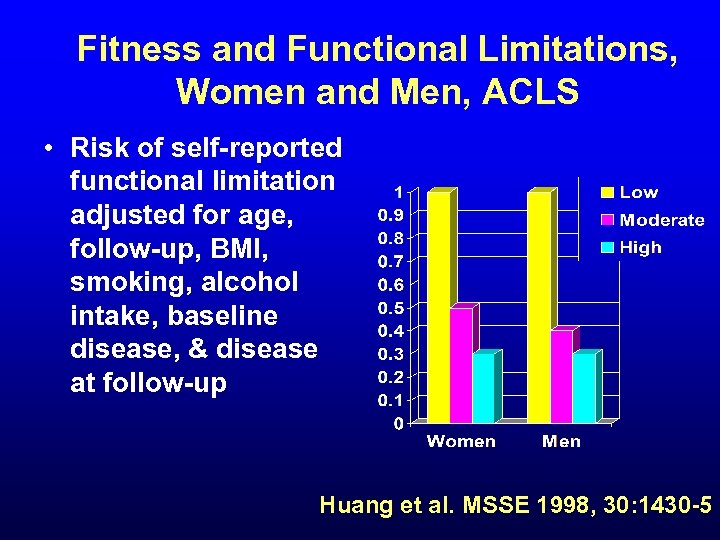

Fitness and Functional Limitations, Women and Men, ACLS • Risk of self-reported functional limitation adjusted for age, follow-up, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, baseline disease, & disease at follow-up Huang et al. MSSE 1998, 30: 1430 -5

Fitness and Functional Limitations, Women and Men, ACLS • Risk of self-reported functional limitation adjusted for age, follow-up, BMI, smoking, alcohol intake, baseline disease, & disease at follow-up Huang et al. MSSE 1998, 30: 1430 -5

Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Risk of Dementia, ACLS • 59, 960 women and men • Followed for 16. 9 years after clinic exam • 4, 108 individuals died Hazard Ratio P for trend=0. 002 – 161 with dementia listed on the death certificate • Hazard ratio adjusted for age, sex, exam yr, BMI, smoking, alcohol, abnormal ECG, history of hypertension, diabetes, abnormal lipids, and health status Fitness Categories Lui R et al. In review

Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Risk of Dementia, ACLS • 59, 960 women and men • Followed for 16. 9 years after clinic exam • 4, 108 individuals died Hazard Ratio P for trend=0. 002 – 161 with dementia listed on the death certificate • Hazard ratio adjusted for age, sex, exam yr, BMI, smoking, alcohol, abnormal ECG, history of hypertension, diabetes, abnormal lipids, and health status Fitness Categories Lui R et al. In review

Exercise Is Medicine

Exercise Is Medicine

Physical Activity as Treatment for Chronic Disease

Physical Activity as Treatment for Chronic Disease

Age and exam year adjusted rates of total CVD events by levels of CRF and severity of HTN in 8147 hypertensive men CVD incidence/1000 man-years P <. 001 P =. 048 CRF: Controlled HTN Stage 1 HTN Severity of HTN Stage 2 HTN Sui X et al. Am J Hyptertension. 2007

Age and exam year adjusted rates of total CVD events by levels of CRF and severity of HTN in 8147 hypertensive men CVD incidence/1000 man-years P <. 001 P =. 048 CRF: Controlled HTN Stage 1 HTN Severity of HTN Stage 2 HTN Sui X et al. Am J Hyptertension. 2007

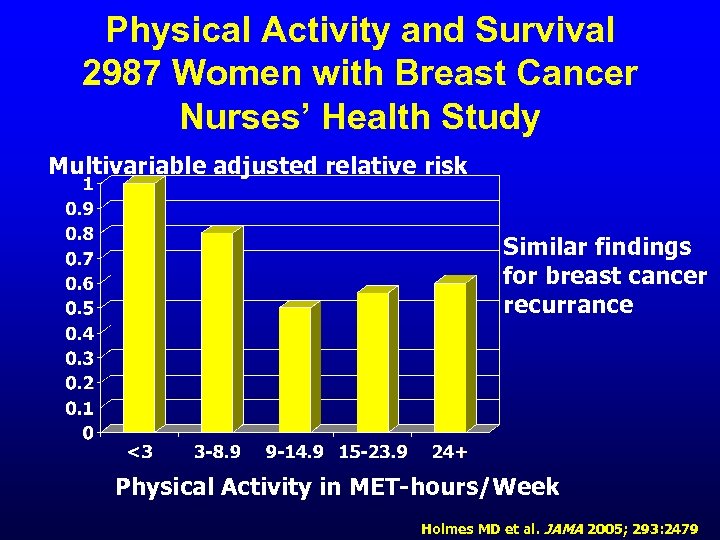

Physical Activity and Survival 2987 Women with Breast Cancer Nurses’ Health Study Multivariable adjusted relative risk Similar findings for breast cancer recurrance Physical Activity in MET-hours/Week Holmes MD et al. JAMA 2005; 293: 2479

Physical Activity and Survival 2987 Women with Breast Cancer Nurses’ Health Study Multivariable adjusted relative risk Similar findings for breast cancer recurrance Physical Activity in MET-hours/Week Holmes MD et al. JAMA 2005; 293: 2479

Yes, But Those Are Observational Studies, and We Require Randomized Clinical Trial Evidence

Yes, But Those Are Observational Studies, and We Require Randomized Clinical Trial Evidence

Exercise Is As Good As Other Treatments for Clinical Depression % of Patients with Remission of Depression Amount of Brisk Walking Drug therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy produce remission in approximately 40% of clinically depressed individuals Dunn A et al. Am J Prev Med 2005

Exercise Is As Good As Other Treatments for Clinical Depression % of Patients with Remission of Depression Amount of Brisk Walking Drug therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy produce remission in approximately 40% of clinically depressed individuals Dunn A et al. Am J Prev Med 2005

Exercise Training and Angioplasty, 101 Men with Stable CAD Event-free survival (%) Per unit change in angina-CCS Exercise was 20 minutes/day Hambrecht R et al. Circulation 2004; 109: 1371 on a cycle ergometer

Exercise Training and Angioplasty, 101 Men with Stable CAD Event-free survival (%) Per unit change in angina-CCS Exercise was 20 minutes/day Hambrecht R et al. Circulation 2004; 109: 1371 on a cycle ergometer

Reduction in Risk of Developing Diabetes in Comparison with Controls, DPP Risk reduction (%) 100 *Moderate intensity exercise 80 of 150 min/week; low calorie, low fat diet 58% 60 40 31% 20 0 Lifestyle Intervention* DPP Research Group. NEJM 2002; 346: 393 -403 Metformi n

Reduction in Risk of Developing Diabetes in Comparison with Controls, DPP Risk reduction (%) 100 *Moderate intensity exercise 80 of 150 min/week; low calorie, low fat diet 58% 60 40 31% 20 0 Lifestyle Intervention* DPP Research Group. NEJM 2002; 346: 393 -403 Metformi n

Cost Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention-DPP • The lifestyle and metformin groups cost $2, 250 more/year than placebo • As implemented in the DPP and from a societal perspective, lifestyle was more cost effective than metformin DPP Res Group. Diab Care 2003; 26: 2518

Cost Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention-DPP • The lifestyle and metformin groups cost $2, 250 more/year than placebo • As implemented in the DPP and from a societal perspective, lifestyle was more cost effective than metformin DPP Res Group. Diab Care 2003; 26: 2518

Do We Have an Obesity Epidemic? • Yes, and I am not going to show you the obesity maps to prove it! • What is the cause of the obesity epidemic? – No one knows, other than there have been too many people in a positive caloric balance on too many days • But there is a lot of passion on the topic

Do We Have an Obesity Epidemic? • Yes, and I am not going to show you the obesity maps to prove it! • What is the cause of the obesity epidemic? – No one knows, other than there have been too many people in a positive caloric balance on too many days • But there is a lot of passion on the topic

It’s calories that count Energy In Portion size High-fat foods Energy dense Low-fiber Soft drinks Energy Out Media (TV, PC) Cars No heavy labour

It’s calories that count Energy In Portion size High-fat foods Energy dense Low-fiber Soft drinks Energy Out Media (TV, PC) Cars No heavy labour

However, Energy Balance Is Poorly Understood

However, Energy Balance Is Poorly Understood

Donald Kennedy & Philip Abelson. The Obesity Epidemic. Science 2004; 304: 1413 • “…Americans continued to consume an average of 3800 calories person per day, or about twice the daily requirement. ”

Donald Kennedy & Philip Abelson. The Obesity Epidemic. Science 2004; 304: 1413 • “…Americans continued to consume an average of 3800 calories person per day, or about twice the daily requirement. ”

What Is Wrong with the Statement? • “…Americans continued to consume an average of 3800 calories person per day, or about twice the daily requirement. ” • 3800/2=1900 extra calories/day • ~7700 calories to lay down 1 kg of fat • ~1 kg every 4 days • ~90 kg/year Kennedy & Abelson. The Obesity Epidemic. Science 2004; 304: 1413

What Is Wrong with the Statement? • “…Americans continued to consume an average of 3800 calories person per day, or about twice the daily requirement. ” • 3800/2=1900 extra calories/day • ~7700 calories to lay down 1 kg of fat • ~1 kg every 4 days • ~90 kg/year Kennedy & Abelson. The Obesity Epidemic. Science 2004; 304: 1413

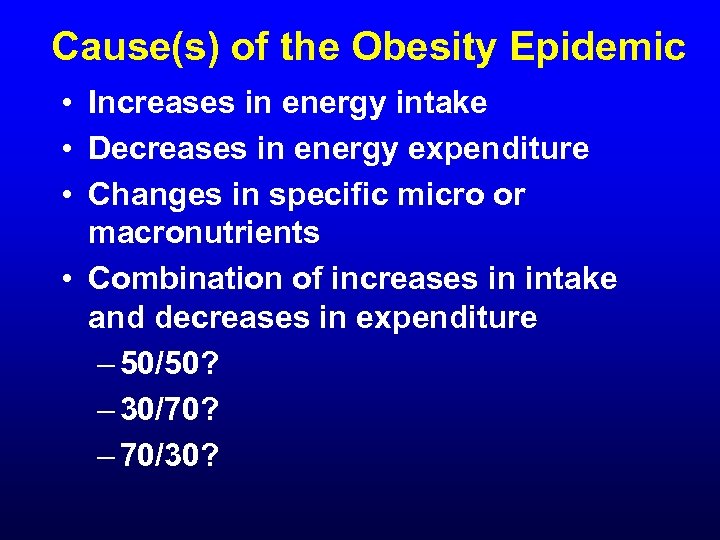

Cause(s) of the Obesity Epidemic • Increases in energy intake • Decreases in energy expenditure • Changes in specific micro or macronutrients • Combination of increases in intake and decreases in expenditure – 50/50? – 30/70? – 70/30?

Cause(s) of the Obesity Epidemic • Increases in energy intake • Decreases in energy expenditure • Changes in specific micro or macronutrients • Combination of increases in intake and decreases in expenditure – 50/50? – 30/70? – 70/30?

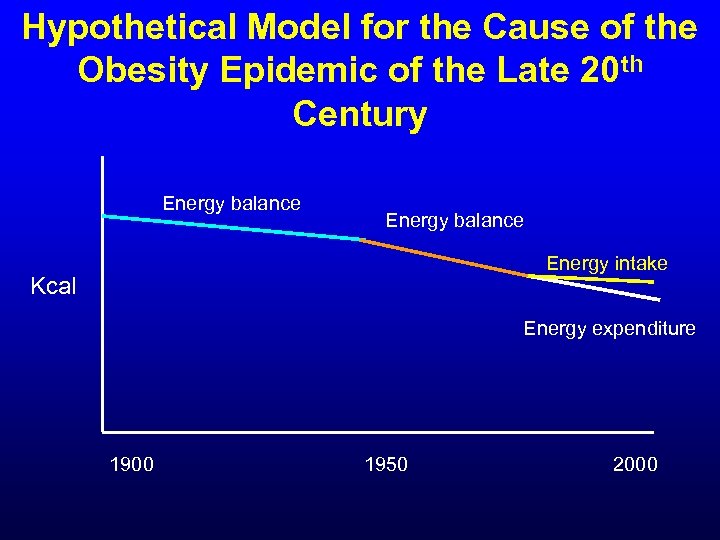

Hypothetical Model for the Cause of the Obesity Epidemic of the Late 20 th Century Energy balance Energy intake Kcal Energy expenditure 1900 1950 2000

Hypothetical Model for the Cause of the Obesity Epidemic of the Late 20 th Century Energy balance Energy intake Kcal Energy expenditure 1900 1950 2000

Is the Average Total Daily Caloric Intake Increasing?

Is the Average Total Daily Caloric Intake Increasing?

Trends in Energy Intake NHANES 1971 -2000 • Data sources – NHANES I— 1971 -1974 – NHANES II— 1976 -1980 – NHANES III— 1988 -1994 – NHANES— 1999 -2000 • Surveys were representative samples of noninstitutionalized U. S. women and men aged 20 to 74 years Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

Trends in Energy Intake NHANES 1971 -2000 • Data sources – NHANES I— 1971 -1974 – NHANES II— 1976 -1980 – NHANES III— 1988 -1994 – NHANES— 1999 -2000 • Surveys were representative samples of noninstitutionalized U. S. women and men aged 20 to 74 years Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

Trends in Energy Intake 1971 to 2000, Men, NHANES Kcal/day Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

Trends in Energy Intake 1971 to 2000, Men, NHANES Kcal/day Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

Trends in Energy Intake 1971 to 2000, Women, NHANES Kcal/day Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

Trends in Energy Intake 1971 to 2000, Women, NHANES Kcal/day Source: MMWR Feb 6, 2004

NHANES Survey Methods 1971 -2000 • NHANES I and NHANES II – 24 -hour dietary recall, Monday-Friday • NHANES III and NHANES – 24 -hour dietary recall, Monday-Sunday • Other changes in methodology included better probing techniques and better training of interviewers • Other changes in dietary behavior included more meals eaten away from home and increasing portion sizes

NHANES Survey Methods 1971 -2000 • NHANES I and NHANES II – 24 -hour dietary recall, Monday-Friday • NHANES III and NHANES – 24 -hour dietary recall, Monday-Sunday • Other changes in methodology included better probing techniques and better training of interviewers • Other changes in dietary behavior included more meals eaten away from home and increasing portion sizes

Physical Activity or Total Energy Expenditure? • Physical activity assessments in free-living individuals are problematic and often lead to substantial misclassification (although these problems are at least as common for dietary assessment) • Most epidemiological studies have assessed physical activity habits by self-reported questionnaires • Physical activity reports are not the same as energy expenditure

Physical Activity or Total Energy Expenditure? • Physical activity assessments in free-living individuals are problematic and often lead to substantial misclassification (although these problems are at least as common for dietary assessment) • Most epidemiological studies have assessed physical activity habits by self-reported questionnaires • Physical activity reports are not the same as energy expenditure

BRFSS Trend Data, Women and Men

BRFSS Trend Data, Women and Men

Hypothesis Regarding Energy Intake, Expenditure, and Balance Energy balance kcal intake Normal distribution of susceptibility to dysregulation kcal expenditure Jim Hill & Russ Pate contributed to the concept

Hypothesis Regarding Energy Intake, Expenditure, and Balance Energy balance kcal intake Normal distribution of susceptibility to dysregulation kcal expenditure Jim Hill & Russ Pate contributed to the concept

How Much Physical Activity Is Required? • To prevent initial weight gain • To lose weight • To prevent weight regain • No One Knows! • However, many people think they know

How Much Physical Activity Is Required? • To prevent initial weight gain • To lose weight • To prevent weight regain • No One Knows! • However, many people think they know

Prevention of Unhealthful Weight Gain: What Is Required? • ACSM/CDC recommendation— 30 min of moderate intensity on most days • IOM recommendation— 60 min per day • WHO recommendation—“In order to avoid obesity, populations should remain physically active throughout life at a PAL of 1. 75 or more”

Prevention of Unhealthful Weight Gain: What Is Required? • ACSM/CDC recommendation— 30 min of moderate intensity on most days • IOM recommendation— 60 min per day • WHO recommendation—“In order to avoid obesity, populations should remain physically active throughout life at a PAL of 1. 75 or more”

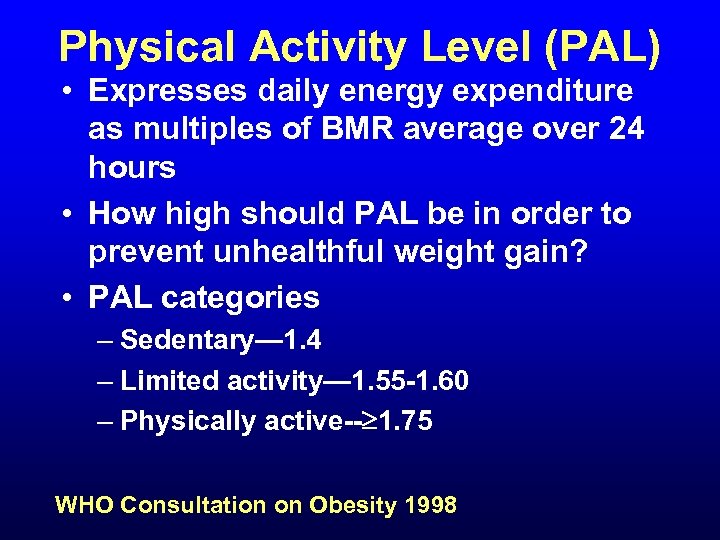

Physical Activity Level (PAL) • Expresses daily energy expenditure as multiples of BMR average over 24 hours • How high should PAL be in order to prevent unhealthful weight gain? • PAL categories – Sedentary— 1. 4 – Limited activity— 1. 55 -1. 60 – Physically active-- 1. 75 WHO Consultation on Obesity 1998

Physical Activity Level (PAL) • Expresses daily energy expenditure as multiples of BMR average over 24 hours • How high should PAL be in order to prevent unhealthful weight gain? • PAL categories – Sedentary— 1. 4 – Limited activity— 1. 55 -1. 60 – Physically active-- 1. 75 WHO Consultation on Obesity 1998

Energy Requirement for Subsistence Farming In bed at 1 MET 8 hours Occupational activities at 2. 7 7 hours METs Household tasks at 3. 0 METs 2 hours Exercise -- Residual time at 1. 4 METs 7 hours Total energy expenditure (PAL)=1. 78 FAO/WHO Joint Consultation. Energy & Protein Requirements. WHO Technical Report Series #724

Energy Requirement for Subsistence Farming In bed at 1 MET 8 hours Occupational activities at 2. 7 7 hours METs Household tasks at 3. 0 METs 2 hours Exercise -- Residual time at 1. 4 METs 7 hours Total energy expenditure (PAL)=1. 78 FAO/WHO Joint Consultation. Energy & Protein Requirements. WHO Technical Report Series #724

Is a PAL of 1. 75 or the IOM 60 Minutes/Day Required to Prevent Weight Gain? • Prevalence of obesity in U. S. adults was constant 10% for several decades prior to 1985 • Prevalence has increased rapidly to one third at present • If a PAL of 1. 75 is required to prevent unhealthful weight gain, 90% of U. S. adults must have had a PAL of 1. 75 prior to 1985 • Does this assumption seem likely?

Is a PAL of 1. 75 or the IOM 60 Minutes/Day Required to Prevent Weight Gain? • Prevalence of obesity in U. S. adults was constant 10% for several decades prior to 1985 • Prevalence has increased rapidly to one third at present • If a PAL of 1. 75 is required to prevent unhealthful weight gain, 90% of U. S. adults must have had a PAL of 1. 75 prior to 1985 • Does this assumption seem likely?

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005* Physical activity recommendations • To help manage body weight and prevent gradual, unhealthy body weight gain in adulthood: Engage in approximately 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity on most days of the week while not exceeding caloric intake requirements *www. health. gov/dietaryguidelines/dga 2005/document/

Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005* Physical activity recommendations • To help manage body weight and prevent gradual, unhealthy body weight gain in adulthood: Engage in approximately 60 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity on most days of the week while not exceeding caloric intake requirements *www. health. gov/dietaryguidelines/dga 2005/document/

Prevention of Weight Gain with Physical Activity Observational Studies

Prevention of Weight Gain with Physical Activity Observational Studies

Kg Weight Change over Time by PAL Change Groups Green lines are significantly different from the reference category (Low-Low) Low-Mod Estimates adjusted for baseline weight, age, sex, height, & change in weight Years Di. Pietro et al. IJO 2004; 28: 1541 Low-High

Kg Weight Change over Time by PAL Change Groups Green lines are significantly different from the reference category (Low-Low) Low-Mod Estimates adjusted for baseline weight, age, sex, height, & change in weight Years Di. Pietro et al. IJO 2004; 28: 1541 Low-High

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass • Representative cohort of 19 -63 year old Finnish women (n=2695) and men (n=2564) • Physical activity assessed at baseline and follow-up – Which of the following categories best describes your physical activity during the past 12 months? • Vigorous activity 2 times/week • Vigorous activity once/week and some light activity • Some activity each week • No regular weekly activity Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass • Representative cohort of 19 -63 year old Finnish women (n=2695) and men (n=2564) • Physical activity assessed at baseline and follow-up – Which of the following categories best describes your physical activity during the past 12 months? • Vigorous activity 2 times/week • Vigorous activity once/week and some light activity • Some activity each week • No regular weekly activity Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass • Change in activity from 1980 to 1990 – Physically active all the time (vigorous activity 1 time/week in both 1980 & 1990 – Physically activated (no vigorous activity in 1980 but at least 1 time/week in 1990) – Physically inactivated (vigorous activity 1 time or more/week in 1980 but not 1990) – Physically inactive all the time (no vigorous activity in either 1980 or 1990) Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass • Change in activity from 1980 to 1990 – Physically active all the time (vigorous activity 1 time/week in both 1980 & 1990 – Physically activated (no vigorous activity in 1980 but at least 1 time/week in 1990) – Physically inactivated (vigorous activity 1 time or more/week in 1980 but not 1990) – Physically inactive all the time (no vigorous activity in either 1980 or 1990) Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

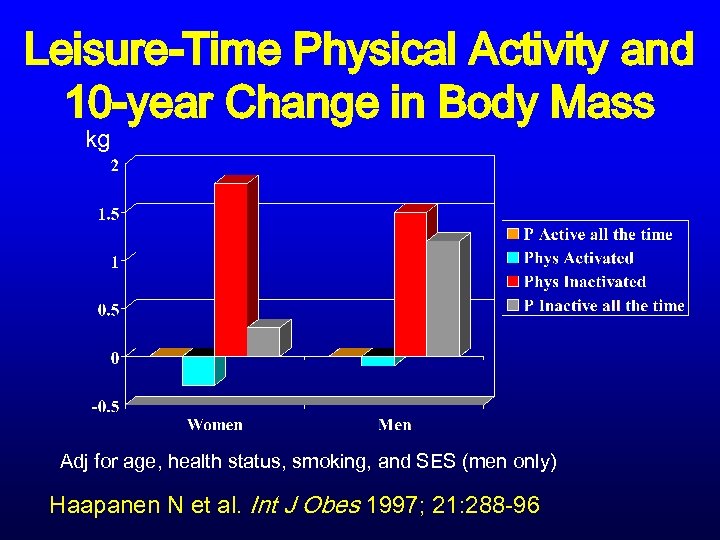

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass kg Adj for age, health status, smoking, and SES (men only) Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

Leisure-Time Physical Activity and 10 -year Change in Body Mass kg Adj for age, health status, smoking, and SES (men only) Haapanen N et al. Int J Obes 1997; 21: 288 -96

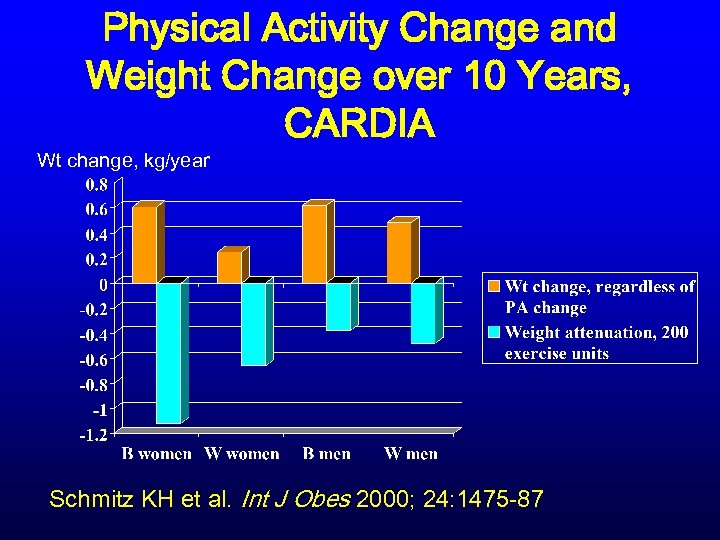

Physical Activity Change and Weight Change over 10 Years, CARDIA Wt change, kg/year Schmitz KH et al. Int J Obes 2000; 24: 1475 -87

Physical Activity Change and Weight Change over 10 Years, CARDIA Wt change, kg/year Schmitz KH et al. Int J Obes 2000; 24: 1475 -87

Prevention of Weight Gain or Weight Loss with Physical Activity Experimental Studies

Prevention of Weight Gain or Weight Loss with Physical Activity Experimental Studies

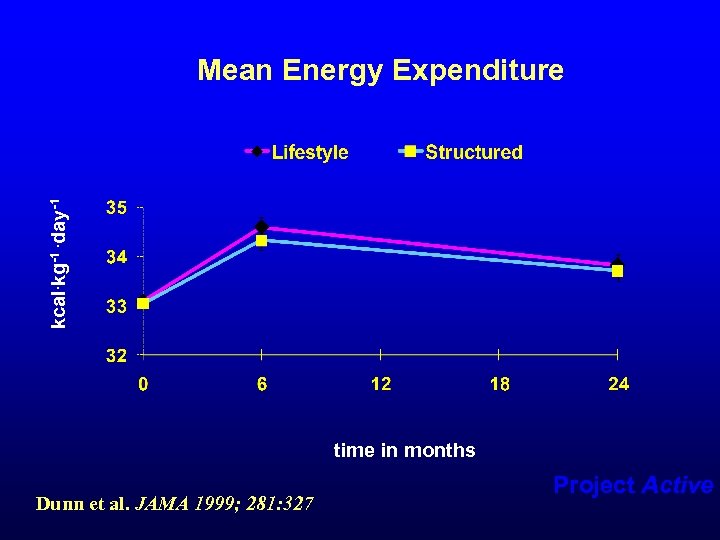

kcal. kg-1. day-1 Mean Energy Expenditure time in months Dunn et al. JAMA 1999; 281: 327 Project Active

kcal. kg-1. day-1 Mean Energy Expenditure time in months Dunn et al. JAMA 1999; 281: 327 Project Active

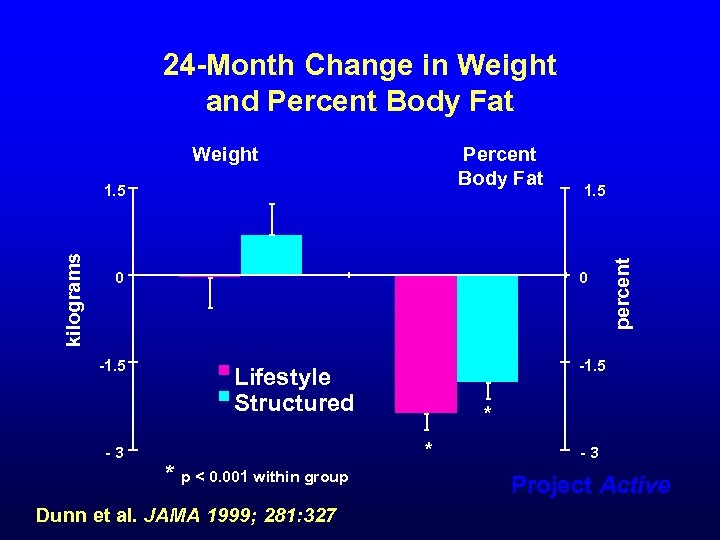

24 -Month Change in Weight and Percent Body Fat kilograms 1. 5 0 -1. 5 -3 1. 5 0 -1. 5 Lifestyle Structured * p < 0. 001 within group Dunn et al. JAMA 1999; 281: 327 percent Weight * * -3 Project Active

24 -Month Change in Weight and Percent Body Fat kilograms 1. 5 0 -1. 5 -3 1. 5 0 -1. 5 Lifestyle Structured * p < 0. 001 within group Dunn et al. JAMA 1999; 281: 327 percent Weight * * -3 Project Active

Dose-Response to Exercise in Post-Menopausal Women (DREW)

Dose-Response to Exercise in Post-Menopausal Women (DREW)

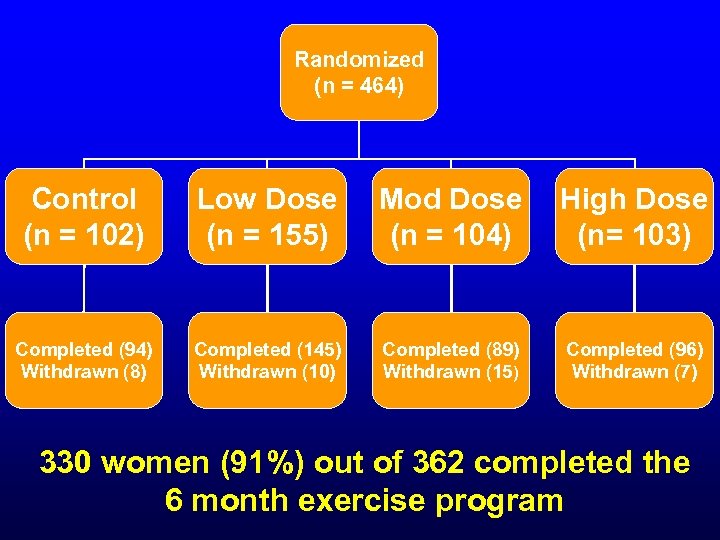

Randomized (n = 464) Control (n = 102) Low Dose (n = 155) Mod Dose (n = 104) High Dose (n= 103) Completed (94) Withdrawn (8) Completed (145) Withdrawn (10) Completed (89) Withdrawn (15) Completed (96) Withdrawn (7) 330 women (91%) out of 362 completed the 6 month exercise program

Randomized (n = 464) Control (n = 102) Low Dose (n = 155) Mod Dose (n = 104) High Dose (n= 103) Completed (94) Withdrawn (8) Completed (145) Withdrawn (10) Completed (89) Withdrawn (15) Completed (96) Withdrawn (7) 330 women (91%) out of 362 completed the 6 month exercise program

Total Adherence 227 had 100% adherence 269 had >99% adherence *Does not include participants who withdrew.

Total Adherence 227 had 100% adherence 269 had >99% adherence *Does not include participants who withdrew.

Change in Fitness Church TS et al. JAMA, 2007; 297: 2081 -2091

Change in Fitness Church TS et al. JAMA, 2007; 297: 2081 -2091

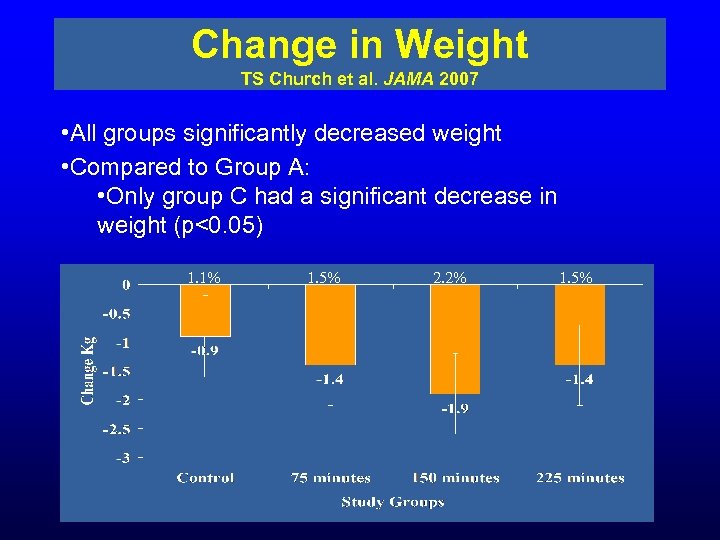

Change in Weight TS Church et al. JAMA 2007 • All groups significantly decreased weight • Compared to Group A: • Only group C had a significant decrease in weight (p<0. 05) 1. 1% 1. 5% 2. 2% 1. 5%

Change in Weight TS Church et al. JAMA 2007 • All groups significantly decreased weight • Compared to Group A: • Only group C had a significant decrease in weight (p<0. 05) 1. 1% 1. 5% 2. 2% 1. 5%

Change in Waist Circumference TS Church et al. JAMA 2007 • Significant decrease in WC occurred in all exercise groups (p<0. 01 all groups) All significant versus control

Change in Waist Circumference TS Church et al. JAMA 2007 • Significant decrease in WC occurred in all exercise groups (p<0. 01 all groups) All significant versus control

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 4 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 4 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 8 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 8 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 12 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Actual vs Predicted Weight Loss, DREW— 12 KKW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Percent of Expected Weight Loss, DREW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Percent of Expected Weight Loss, DREW Church TS et al. PLOS One 2009; 4: 4515

Summary • Some form of compensation is taking place in the 12 KKW but not 4 or 8 KKW groups

Summary • Some form of compensation is taking place in the 12 KKW but not 4 or 8 KKW groups

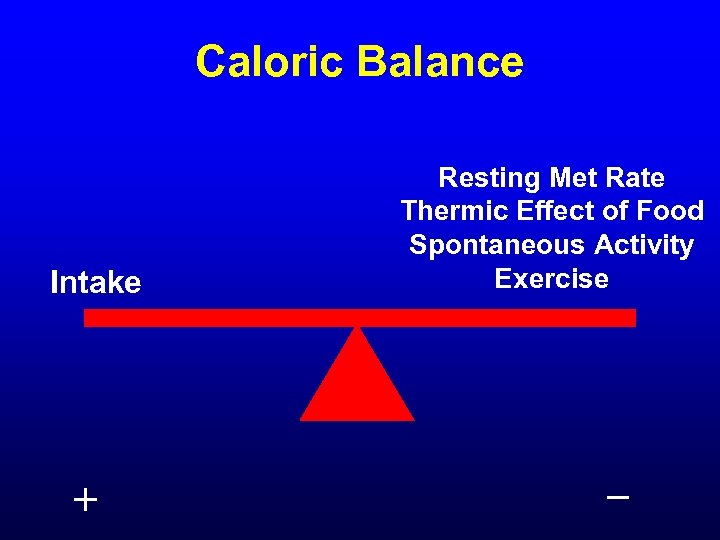

Caloric Balance Intake + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Caloric Balance Intake + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Caloric Balance Intake + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Caloric Balance Intake + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Spontaneous Activity

Spontaneous Activity

Caloric Balance Intake ? ? + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Caloric Balance Intake ? ? + Resting Met Rate Thermic Effect of Food Spontaneous Activity Exercise _

Intake via Food Frequency Questionaire

Intake via Food Frequency Questionaire

Summary • There were no significant differences between groups B, C, and D on either WC or weight. • 6 months of aerobic exercise training decreases central adiposity in sedentary postmenopausal women • Similar reductions in WC across exercise groups suggest a threshold effect versus a dose response relationship between exercise and WC

Summary • There were no significant differences between groups B, C, and D on either WC or weight. • 6 months of aerobic exercise training decreases central adiposity in sedentary postmenopausal women • Similar reductions in WC across exercise groups suggest a threshold effect versus a dose response relationship between exercise and WC

Conclusions • There appears to some form of caloric compensation with higher doses of exercise • At this point we can only hypothesize about the source(s) of compensation • Emphasizes the importance of addressing intake when prescribing exercise for weight loss • Next Steps: – Confirm our findings – Explore reasons • Gender Effects • Better Quantify non-exercise activity • Psychology of eating – Triggers? • Energy storage issue • Amount versus composition of intake

Conclusions • There appears to some form of caloric compensation with higher doses of exercise • At this point we can only hypothesize about the source(s) of compensation • Emphasizes the importance of addressing intake when prescribing exercise for weight loss • Next Steps: – Confirm our findings – Explore reasons • Gender Effects • Better Quantify non-exercise activity • Psychology of eating – Triggers? • Energy storage issue • Amount versus composition of intake

How Much Activity Is Required to Prevent Weight Regain after Weight Loss?

How Much Activity Is Required to Prevent Weight Regain after Weight Loss?

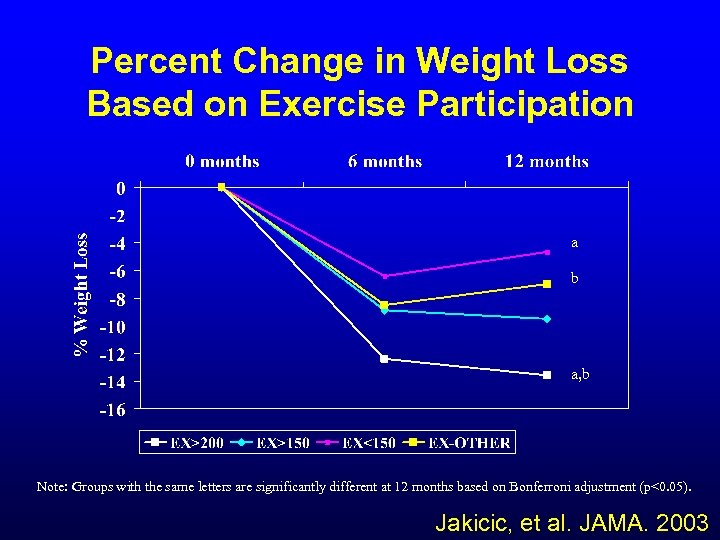

Percent Change in Weight Loss Based on Exercise Participation a b a, b Note: Groups with the same letters are significantly different at 12 months based on Bonferroni adjustment (p<0. 05). Jakicic, et al. JAMA. 2003

Percent Change in Weight Loss Based on Exercise Participation a b a, b Note: Groups with the same letters are significantly different at 12 months based on Bonferroni adjustment (p<0. 05). Jakicic, et al. JAMA. 2003

Average Energy Expended In Physical Activity In The NWCR Klem et al, AJCN 1997; 66: 239 -46.

Average Energy Expended In Physical Activity In The NWCR Klem et al, AJCN 1997; 66: 239 -46.

Summary

Summary

Attributable Fractions of Health Outcomes For Low Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Other Predictors, ACLS • Attributable fraction (%) is the estimated number of deaths due to a specific characteristic • Based on strength of association • Prevalence of the condition

Attributable Fractions of Health Outcomes For Low Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Other Predictors, ACLS • Attributable fraction (%) is the estimated number of deaths due to a specific characteristic • Based on strength of association • Prevalence of the condition

Attributable Fractions (%) for All-Cause Deaths 40, 842 Men & 12, 943 Women, ACLS Blair SN. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43: 1 -2.

Attributable Fractions (%) for All-Cause Deaths 40, 842 Men & 12, 943 Women, ACLS Blair SN. Br J Sports Med 2009; 43: 1 -2.

Final Message • Focus on – Healthful eating habits • Fruits and vegetables • Whole grain – Regular physical activity • Three 10 minute walks/day

Final Message • Focus on – Healthful eating habits • Fruits and vegetables • Whole grain – Regular physical activity • Three 10 minute walks/day

Thank you Questions?

Thank you Questions?