35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 59

The Copula Cycle: Features and Principles of Projection Elly van Gelderen 17 June 2015 University of Greenwich

The Copula Cycle: Features and Principles of Projection Elly van Gelderen 17 June 2015 University of Greenwich

Outline A little on generative historical syntax: ambiguity/reanalysis – features are crucial English copulas: renewal + reanalysis Examples of Grammaticalization and Linguistic Cycles: features + structure The Demonstrative to Copula Cycle Explanations and some challenges: Principles of Projection.

Outline A little on generative historical syntax: ambiguity/reanalysis – features are crucial English copulas: renewal + reanalysis Examples of Grammaticalization and Linguistic Cycles: features + structure The Demonstrative to Copula Cycle Explanations and some challenges: Principles of Projection.

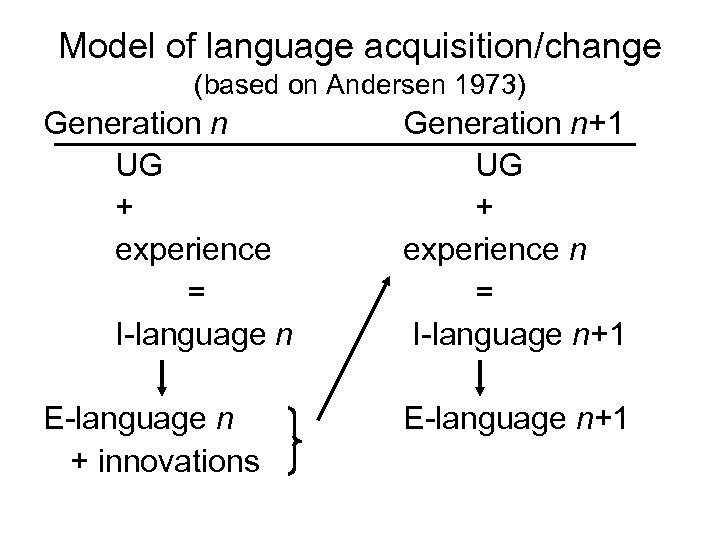

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Internal Grammar

Internal Grammar

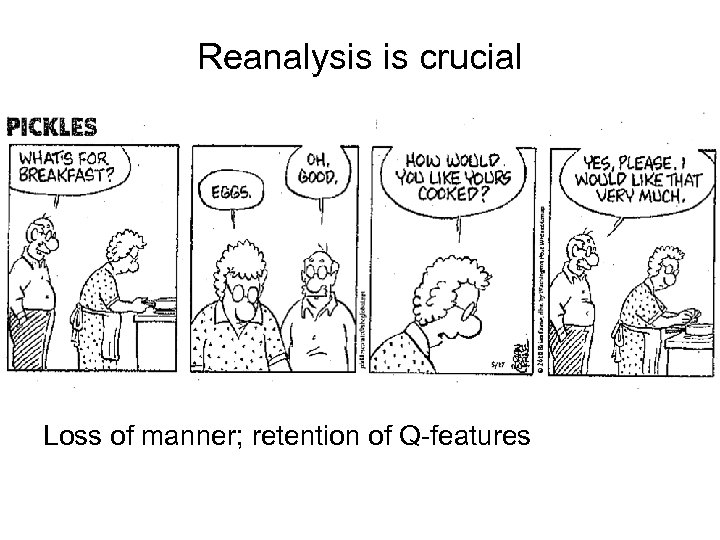

Reanalysis is crucial L Loss of manner; retention of Q-features

Reanalysis is crucial L Loss of manner; retention of Q-features

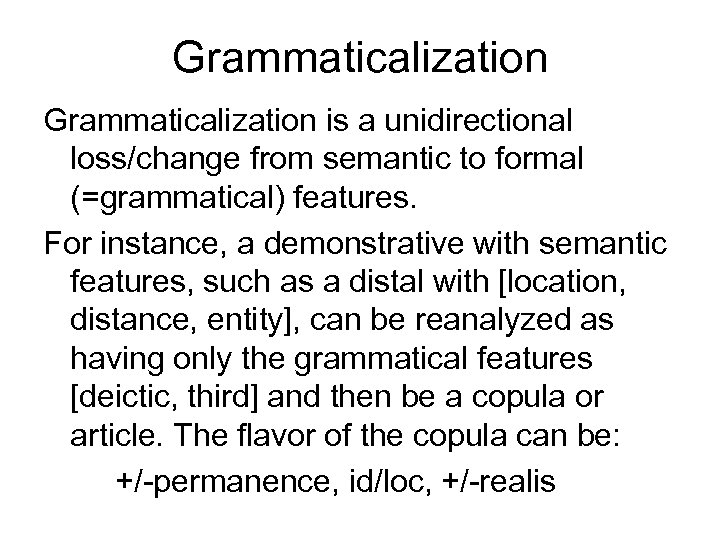

Grammaticalization is a unidirectional loss/change from semantic to formal (=grammatical) features. For instance, a demonstrative with semantic features, such as a distal with [location, distance, entity], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical features [deictic, third] and then be a copula or article. The flavor of the copula can be: +/-permanence, id/loc, +/-realis

Grammaticalization is a unidirectional loss/change from semantic to formal (=grammatical) features. For instance, a demonstrative with semantic features, such as a distal with [location, distance, entity], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical features [deictic, third] and then be a copula or article. The flavor of the copula can be: +/-permanence, id/loc, +/-realis

![Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi]](https://present5.com/presentation/35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05/image-7.jpg) Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc/id] (Diessel 1999 gives 17 grammaticalization channels)

Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] article [u-phi] Dem C copula [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc/id] (Diessel 1999 gives 17 grammaticalization channels)

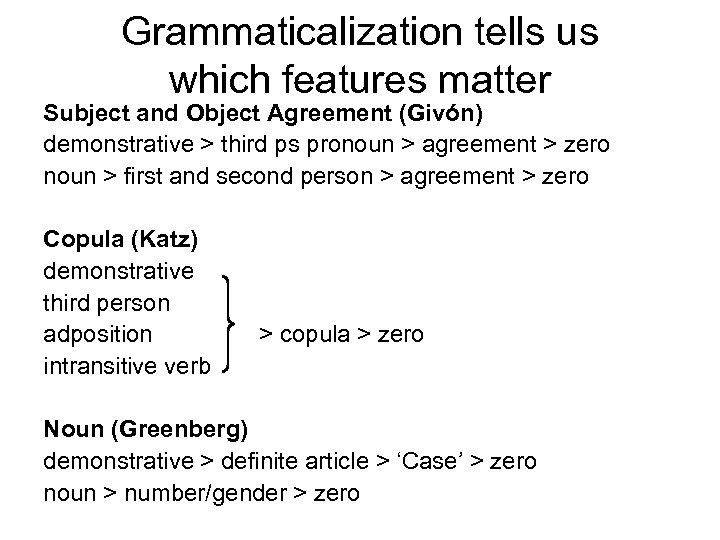

Grammaticalization tells us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero Copula (Katz) demonstrative third person adposition intransitive verb > copula > zero Noun (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

Grammaticalization tells us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero Copula (Katz) demonstrative third person adposition intransitive verb > copula > zero Noun (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

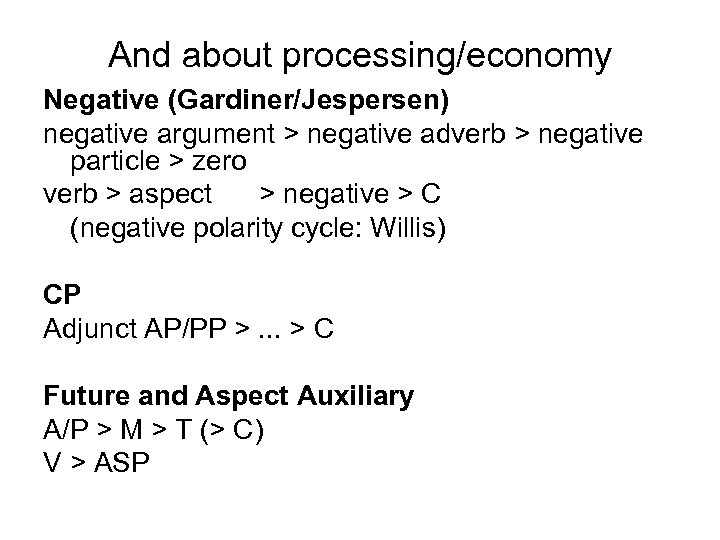

And about processing/economy Negative (Gardiner/Jespersen) negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

And about processing/economy Negative (Gardiner/Jespersen) negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

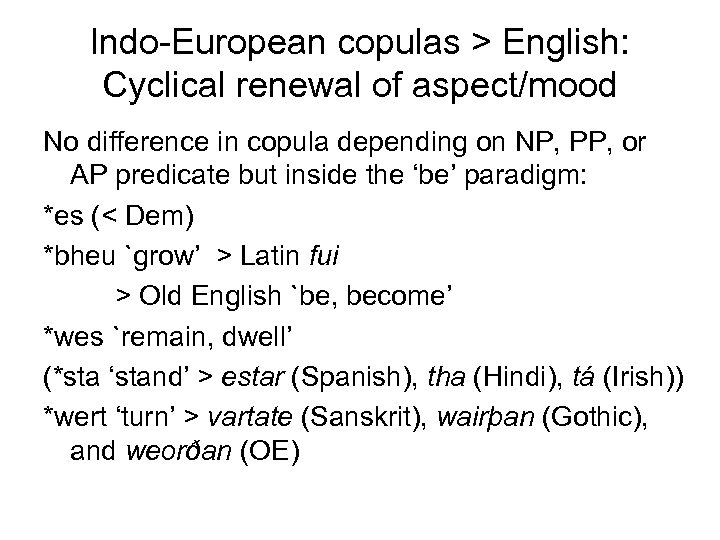

Indo-European copulas > English: Cyclical renewal of aspect/mood No difference in copula depending on NP, PP, or AP predicate but inside the ‘be’ paradigm: *es (< Dem) *bheu `grow’ > Latin fui > Old English `be, become’ *wes `remain, dwell’ (*sta ‘stand’ > estar (Spanish), tha (Hindi), tá (Irish)) *wert ‘turn’ > vartate (Sanskrit), wairþan (Gothic), and weorðan (OE)

Indo-European copulas > English: Cyclical renewal of aspect/mood No difference in copula depending on NP, PP, or AP predicate but inside the ‘be’ paradigm: *es (< Dem) *bheu `grow’ > Latin fui > Old English `be, become’ *wes `remain, dwell’ (*sta ‘stand’ > estar (Spanish), tha (Hindi), tá (Irish)) *wert ‘turn’ > vartate (Sanskrit), wairþan (Gothic), and weorðan (OE)

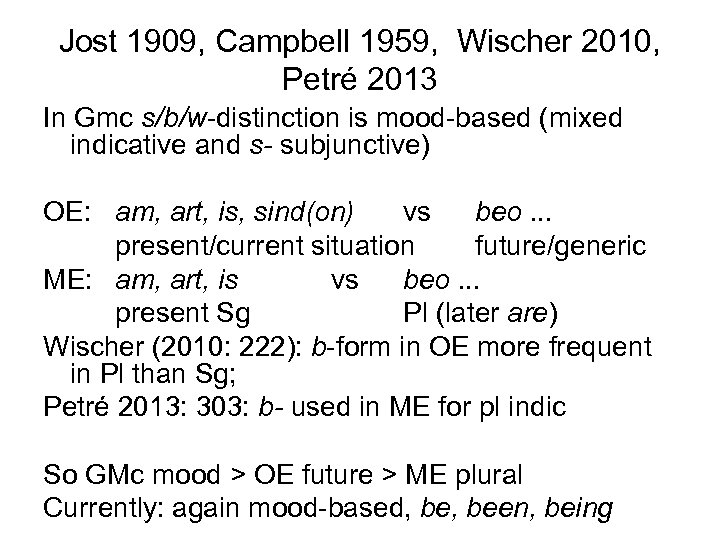

Jost 1909, Campbell 1959, Wischer 2010, Petré 2013 In Gmc s/b/w-distinction is mood-based (mixed indicative and s- subjunctive) OE: am, art, is, sind(on) vs beo. . . present/current situation future/generic ME: am, art, is vs beo. . . present Sg Pl (later are) Wischer (2010: 222): b-form in OE more frequent in Pl than Sg; Petré 2013: 303: b- used in ME for pl indic So GMc mood > OE future > ME plural Currently: again mood-based, been, being

Jost 1909, Campbell 1959, Wischer 2010, Petré 2013 In Gmc s/b/w-distinction is mood-based (mixed indicative and s- subjunctive) OE: am, art, is, sind(on) vs beo. . . present/current situation future/generic ME: am, art, is vs beo. . . present Sg Pl (later are) Wischer (2010: 222): b-form in OE more frequent in Pl than Sg; Petré 2013: 303: b- used in ME for pl indic So GMc mood > OE future > ME plural Currently: again mood-based, been, being

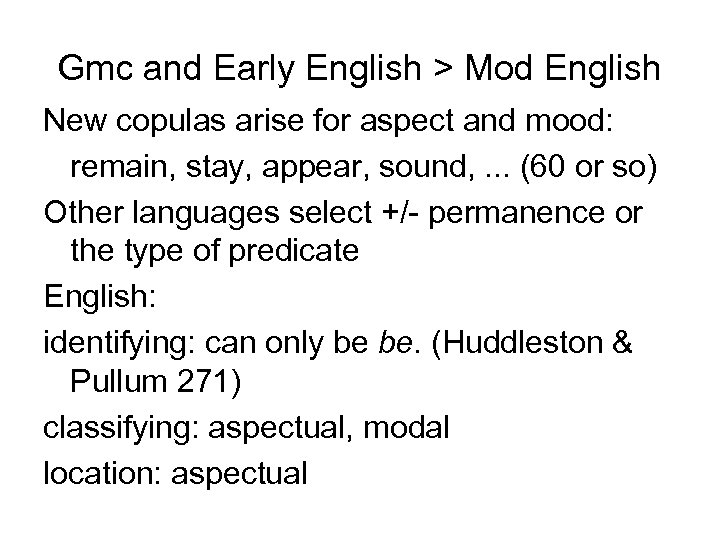

Gmc and Early English > Mod English New copulas arise for aspect and mood: remain, stay, appear, sound, . . . (60 or so) Other languages select +/- permanence or the type of predicate English: identifying: can only be be. (Huddleston & Pullum 271) classifying: aspectual, modal location: aspectual

Gmc and Early English > Mod English New copulas arise for aspect and mood: remain, stay, appear, sound, . . . (60 or so) Other languages select +/- permanence or the type of predicate English: identifying: can only be be. (Huddleston & Pullum 271) classifying: aspectual, modal location: aspectual

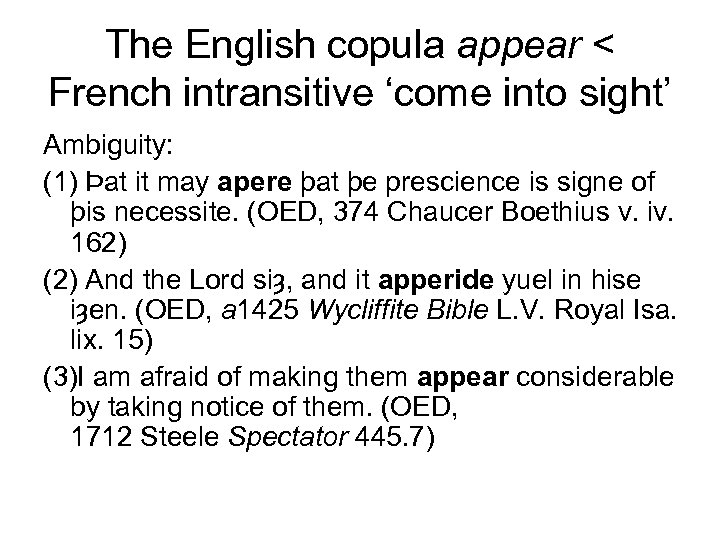

The English copula appear < French intransitive ‘come into sight’ Ambiguity: (1) Þat it may apere þat þe prescience is signe of þis necessite. (OED, 374 Chaucer Boethius v. iv. 162) (2) And the Lord siȝ, and it apperide yuel in hise iȝen. (OED, a 1425 Wycliffite Bible L. V. Royal Isa. lix. 15) (3)I am afraid of making them appear considerable by taking notice of them. (OED, 1712 Steele Spectator 445. 7)

The English copula appear < French intransitive ‘come into sight’ Ambiguity: (1) Þat it may apere þat þe prescience is signe of þis necessite. (OED, 374 Chaucer Boethius v. iv. 162) (2) And the Lord siȝ, and it apperide yuel in hise iȝen. (OED, a 1425 Wycliffite Bible L. V. Royal Isa. lix. 15) (3)I am afraid of making them appear considerable by taking notice of them. (OED, 1712 Steele Spectator 445. 7)

![PP in hise i 3 en V apperide [change] [visual] [u. Th] DP it PP in hise i 3 en V apperide [change] [visual] [u. Th] DP it](https://present5.com/presentation/35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05/image-14.jpg) PP in hise i 3 en V apperide [change] [visual] [u. Th] DP it [i-3 S] [Th] > DP copula PP or DP copula AP

PP in hise i 3 en V apperide [change] [visual] [u. Th] DP it [i-3 S] [Th] > DP copula PP or DP copula AP

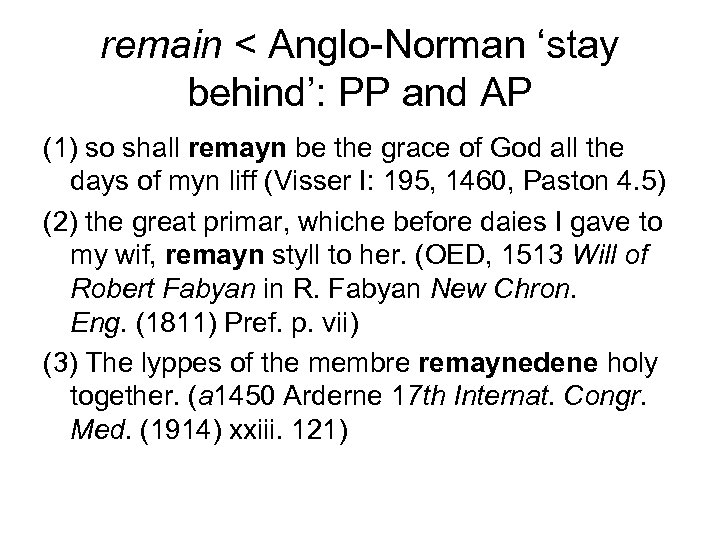

remain < Anglo-Norman ‘stay behind’: PP and AP (1) so shall remayn be the grace of God all the days of myn liff (Visser I: 195, 1460, Paston 4. 5) (2) the great primar, whiche before daies I gave to my wif, remayn styll to her. (OED, 1513 Will of Robert Fabyan in R. Fabyan New Chron. Eng. (1811) Pref. p. vii) (3) The lyppes of the membre remaynedene holy together. (a 1450 Arderne 17 th Internat. Congr. Med. (1914) xxiii. 121)

remain < Anglo-Norman ‘stay behind’: PP and AP (1) so shall remayn be the grace of God all the days of myn liff (Visser I: 195, 1460, Paston 4. 5) (2) the great primar, whiche before daies I gave to my wif, remayn styll to her. (OED, 1513 Will of Robert Fabyan in R. Fabyan New Chron. Eng. (1811) Pref. p. vii) (3) The lyppes of the membre remaynedene holy together. (a 1450 Arderne 17 th Internat. Congr. Med. (1914) xxiii. 121)

![PP Pred to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar PP Pred to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar](https://present5.com/presentation/35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05/image-16.jpg) PP Pred to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar to her [location] [i-3 S] [duration] [Th] [u. Th]

PP Pred to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar to her [location] [i-3 S] [duration] [Th] [u. Th]

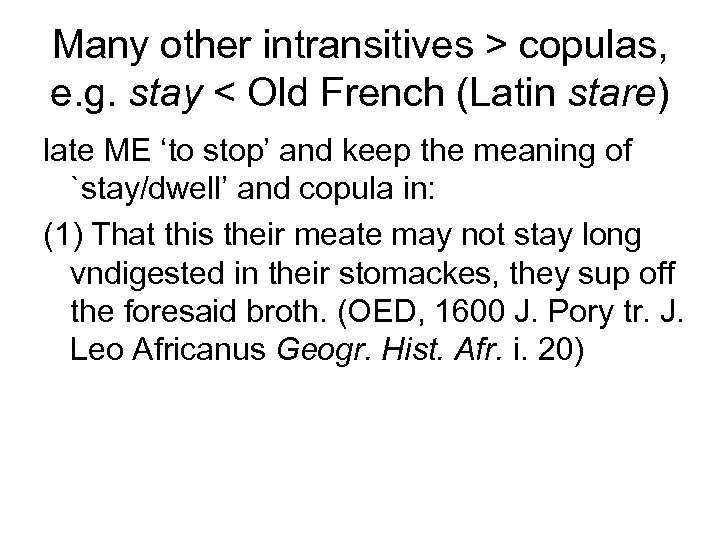

Many other intransitives > copulas, e. g. stay < Old French (Latin stare) late ME ‘to stop’ and keep the meaning of `stay/dwell’ and copula in: (1) That this their meate may not stay long vndigested in their stomackes, they sup off the foresaid broth. (OED, 1600 J. Pory tr. J. Leo Africanus Geogr. Hist. Afr. i. 20)

Many other intransitives > copulas, e. g. stay < Old French (Latin stare) late ME ‘to stop’ and keep the meaning of `stay/dwell’ and copula in: (1) That this their meate may not stay long vndigested in their stomackes, they sup off the foresaid broth. (OED, 1600 J. Pory tr. J. Leo Africanus Geogr. Hist. Afr. i. 20)

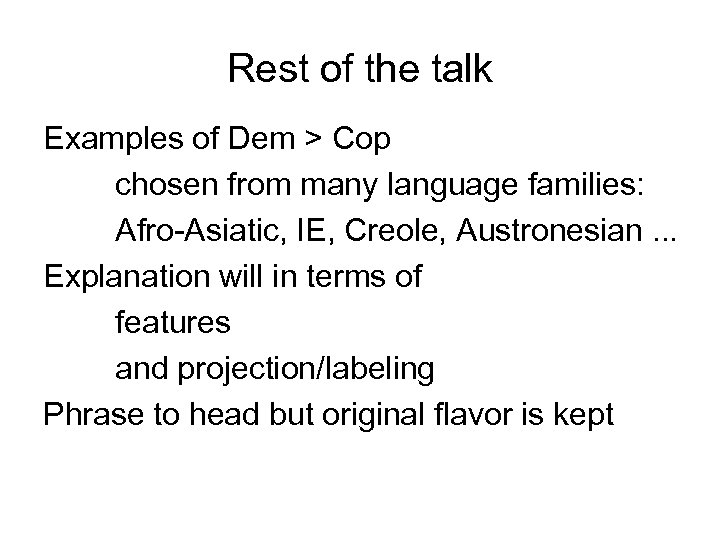

Rest of the talk Examples of Dem > Cop chosen from many language families: Afro-Asiatic, IE, Creole, Austronesian. . . Explanation will in terms of features and projection/labeling Phrase to head but original flavor is kept

Rest of the talk Examples of Dem > Cop chosen from many language families: Afro-Asiatic, IE, Creole, Austronesian. . . Explanation will in terms of features and projection/labeling Phrase to head but original flavor is kept

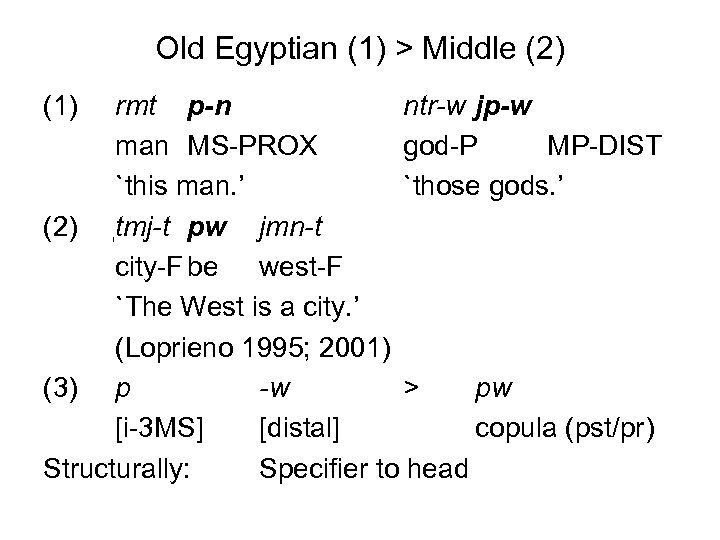

Old Egyptian (1) > Middle (2) (1) rmt p-n ntr-w jp-w man MS-PROX god-P MP-DIST `this man. ’ `those gods. ’ (2) tmj-t pw jmn-t city-F be west-F `The West is a city. ’ (Loprieno 1995; 2001) (3) p -w > pw [i-3 MS] [distal] copula (pst/pr) Structurally: Specifier to head

Old Egyptian (1) > Middle (2) (1) rmt p-n ntr-w jp-w man MS-PROX god-P MP-DIST `this man. ’ `those gods. ’ (2) tmj-t pw jmn-t city-F be west-F `The West is a city. ’ (Loprieno 1995; 2001) (3) p -w > pw [i-3 MS] [distal] copula (pst/pr) Structurally: Specifier to head

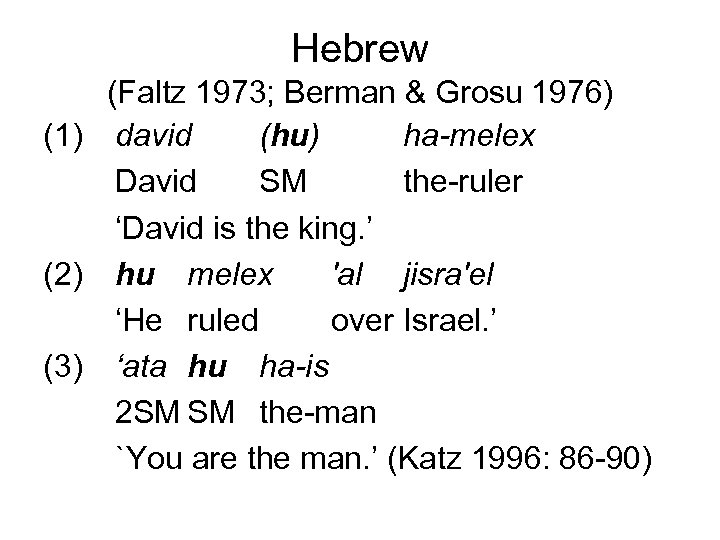

Hebrew (Faltz 1973; Berman & Grosu 1976) (1) david (hu) ha-melex David SM the-ruler ‘David is the king. ’ (2) hu melex 'al jisra'el ‘He ruled over Israel. ’ (3) ‘ata hu ha-is 2 SM SM the-man `You are the man. ’ (Katz 1996: 86 -90)

Hebrew (Faltz 1973; Berman & Grosu 1976) (1) david (hu) ha-melex David SM the-ruler ‘David is the king. ’ (2) hu melex 'al jisra'el ‘He ruled over Israel. ’ (3) ‘ata hu ha-is 2 SM SM the-man `You are the man. ’ (Katz 1996: 86 -90)

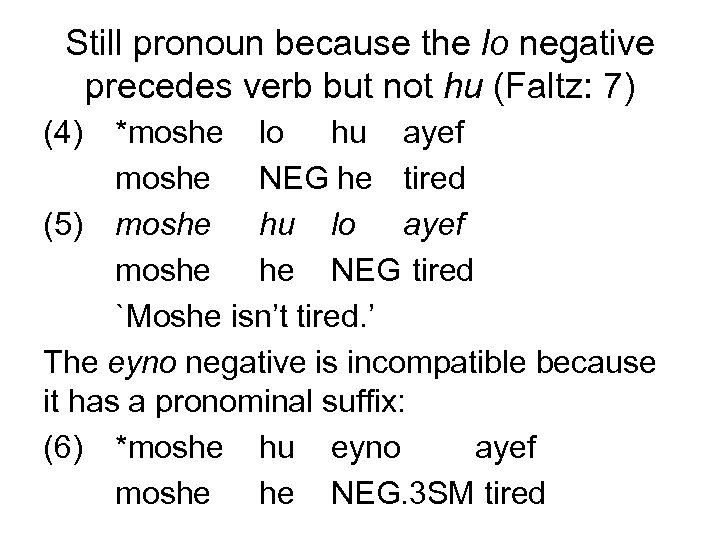

Still pronoun because the lo negative precedes verb but not hu (Faltz: 7) (4) *moshe lo hu ayef moshe NEG he tired (5) moshe hu lo ayef moshe he NEG tired `Moshe isn’t tired. ’ The eyno negative is incompatible because it has a pronominal suffix: (6) *moshe hu eyno ayef moshe he NEG. 3 SM tired

Still pronoun because the lo negative precedes verb but not hu (Faltz: 7) (4) *moshe lo hu ayef moshe NEG he tired (5) moshe hu lo ayef moshe he NEG tired `Moshe isn’t tired. ’ The eyno negative is incompatible because it has a pronominal suffix: (6) *moshe hu eyno ayef moshe he NEG. 3 SM tired

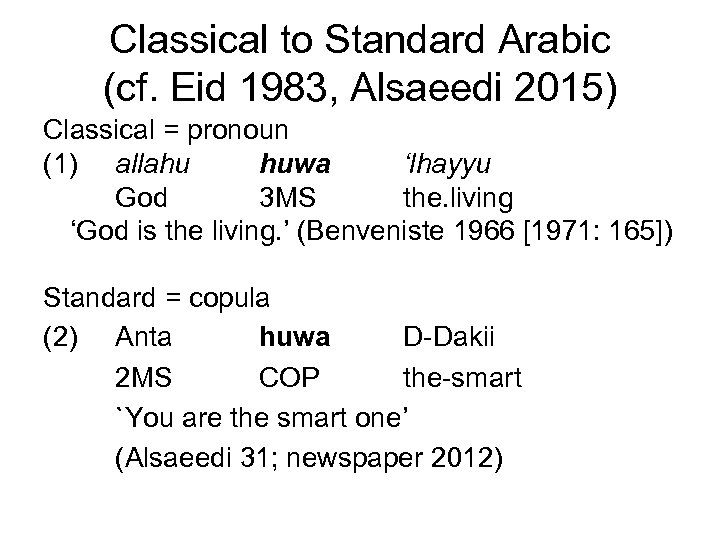

Classical to Standard Arabic (cf. Eid 1983, Alsaeedi 2015) Classical = pronoun (1) allahu huwa ‘lhayyu God 3 MS the. living ‘God is the living. ’ (Benveniste 1966 [1971: 165]) Standard = copula (2) Anta huwa D-Dakii 2 MS COP the-smart `You are the smart one’ (Alsaeedi 31; newspaper 2012)

Classical to Standard Arabic (cf. Eid 1983, Alsaeedi 2015) Classical = pronoun (1) allahu huwa ‘lhayyu God 3 MS the. living ‘God is the living. ’ (Benveniste 1966 [1971: 165]) Standard = copula (2) Anta huwa D-Dakii 2 MS COP the-smart `You are the smart one’ (Alsaeedi 31; newspaper 2012)

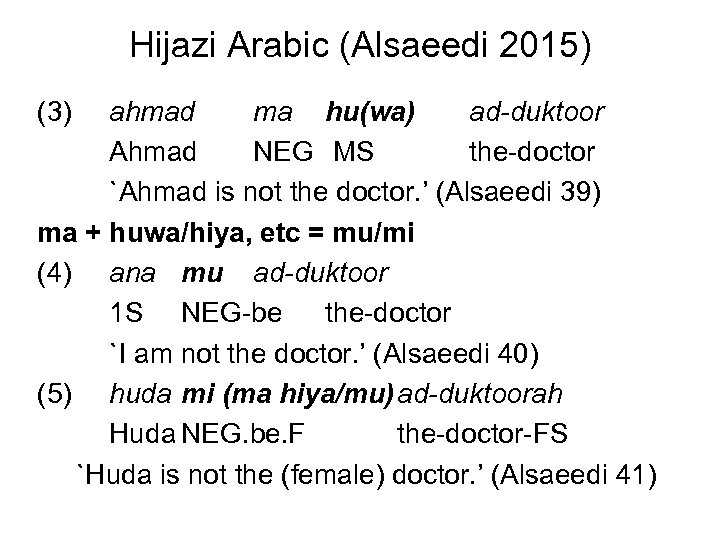

Hijazi Arabic (Alsaeedi 2015) (3) ahmad ma hu(wa) ad-duktoor Ahmad NEG MS the-doctor `Ahmad is not the doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 39) ma + huwa/hiya, etc = mu/mi (4) ana mu ad-duktoor 1 S NEG-be the-doctor `I am not the doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 40) (5) huda mi (ma hiya/mu) ad-duktoorah Huda NEG. be. F the-doctor-FS `Huda is not the (female) doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 41)

Hijazi Arabic (Alsaeedi 2015) (3) ahmad ma hu(wa) ad-duktoor Ahmad NEG MS the-doctor `Ahmad is not the doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 39) ma + huwa/hiya, etc = mu/mi (4) ana mu ad-duktoor 1 S NEG-be the-doctor `I am not the doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 40) (5) huda mi (ma hiya/mu) ad-duktoorah Huda NEG. be. F the-doctor-FS `Huda is not the (female) doctor. ’ (Alsaeedi 41)

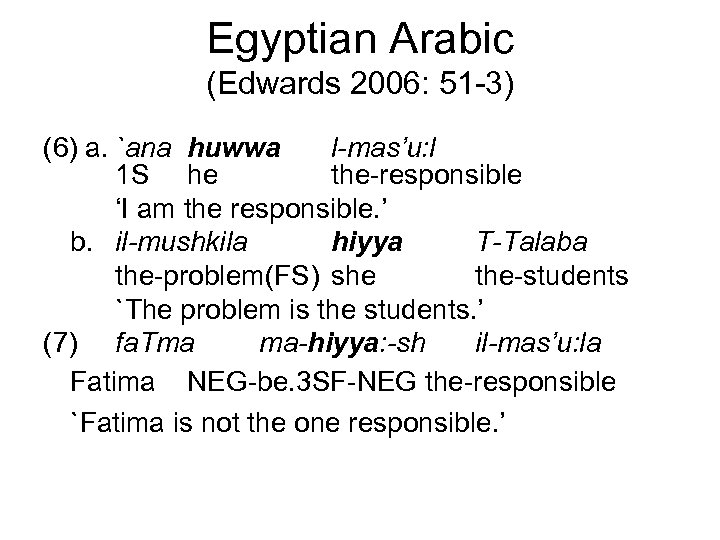

Egyptian Arabic (Edwards 2006: 51 -3) (6) a. `ana huwwa l-mas’u: l 1 S he the-responsible ‘I am the responsible. ’ b. il-mushkila hiyya T-Talaba the-problem(FS) she the-students `The problem is the students. ’ (7) fa. Tma ma-hiyya: -sh il-mas’u: la Fatima NEG-be. 3 SF-NEG the-responsible `Fatima is not the one responsible. ’

Egyptian Arabic (Edwards 2006: 51 -3) (6) a. `ana huwwa l-mas’u: l 1 S he the-responsible ‘I am the responsible. ’ b. il-mushkila hiyya T-Talaba the-problem(FS) she the-students `The problem is the students. ’ (7) fa. Tma ma-hiyya: -sh il-mas’u: la Fatima NEG-be. 3 SF-NEG the-responsible `Fatima is not the one responsible. ’

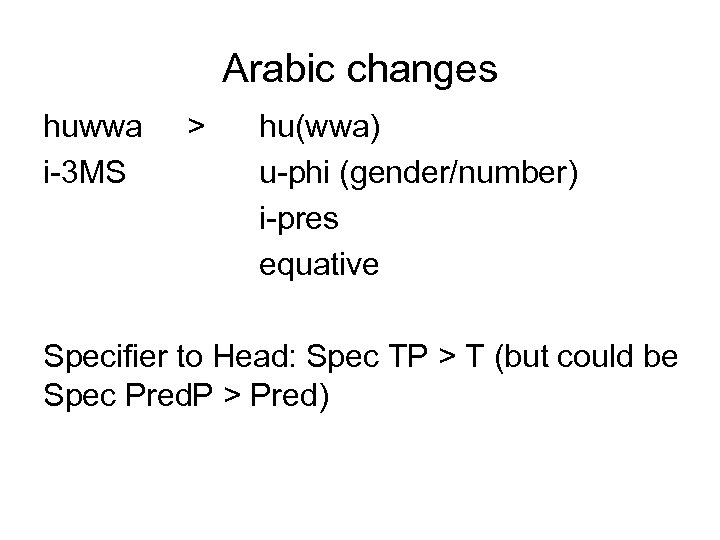

Arabic changes huwwa i-3 MS > hu(wwa) u-phi (gender/number) i-pres equative Specifier to Head: Spec TP > T (but could be Spec Pred. P > Pred)

Arabic changes huwwa i-3 MS > hu(wwa) u-phi (gender/number) i-pres equative Specifier to Head: Spec TP > T (but could be Spec Pred. P > Pred)

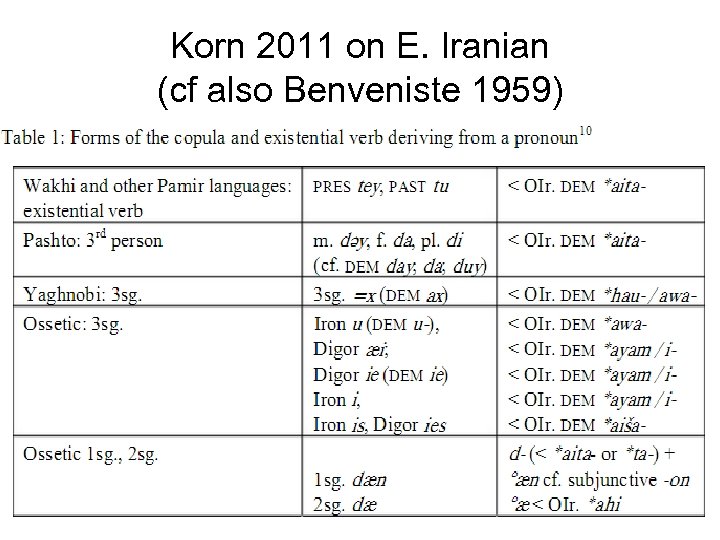

Korn 2011 on E. Iranian (cf also Benveniste 1959)

Korn 2011 on E. Iranian (cf also Benveniste 1959)

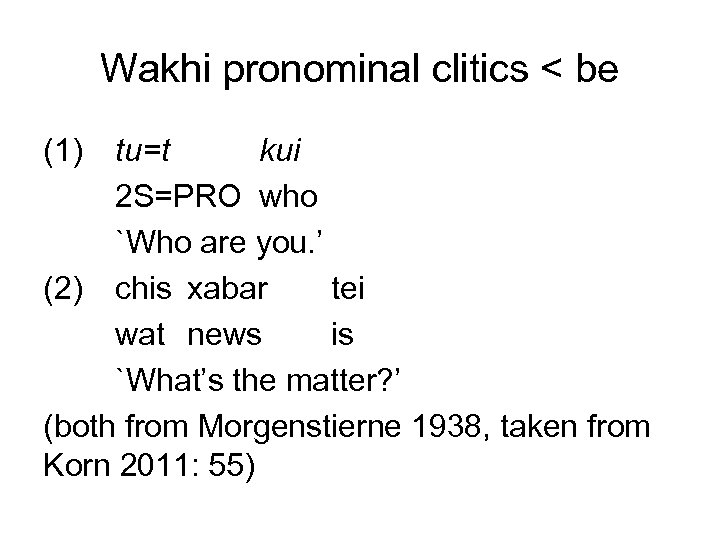

Wakhi pronominal clitics < be (1) tu=t kui 2 S=PRO who `Who are you. ’ (2) chis xabar tei wat news is `What’s the matter? ’ (both from Morgenstierne 1938, taken from Korn 2011: 55)

Wakhi pronominal clitics < be (1) tu=t kui 2 S=PRO who `Who are you. ’ (2) chis xabar tei wat news is `What’s the matter? ’ (both from Morgenstierne 1938, taken from Korn 2011: 55)

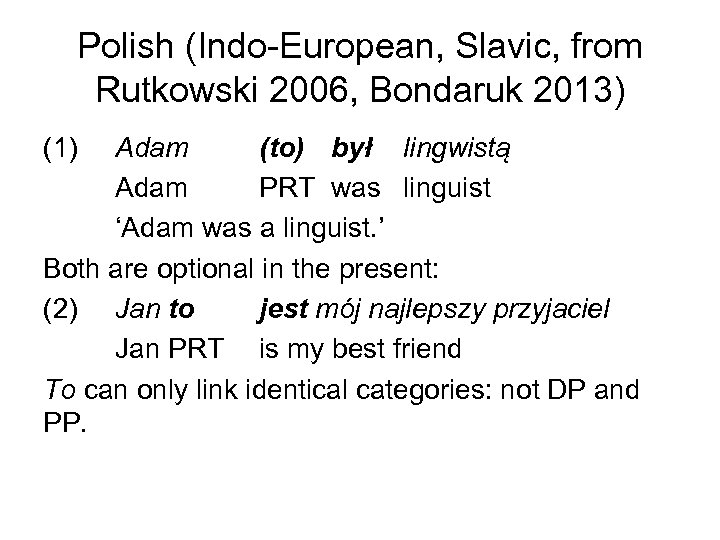

Polish (Indo-European, Slavic, from Rutkowski 2006, Bondaruk 2013) (1) Adam (to) był lingwistą Adam PRT was linguist ‘Adam was a linguist. ’ Both are optional in the present: (2) Jan to jest mój najlepszy przyjaciel Jan PRT is my best friend To can only link identical categories: not DP and PP.

Polish (Indo-European, Slavic, from Rutkowski 2006, Bondaruk 2013) (1) Adam (to) był lingwistą Adam PRT was linguist ‘Adam was a linguist. ’ Both are optional in the present: (2) Jan to jest mój najlepszy przyjaciel Jan PRT is my best friend To can only link identical categories: not DP and PP.

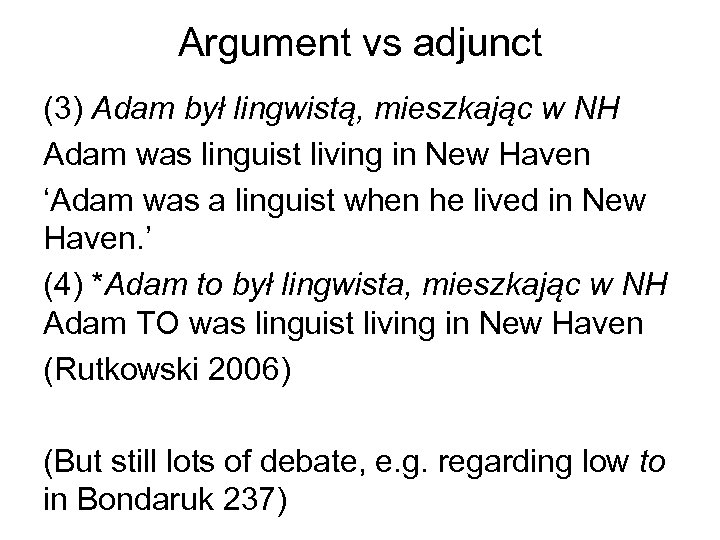

Argument vs adjunct (3) Adam był lingwistą, mieszkając w NH Adam was linguist living in New Haven ‘Adam was a linguist when he lived in New Haven. ’ (4) *Adam to był lingwista, mieszkając w NH Adam TO was linguist living in New Haven (Rutkowski 2006) (But still lots of debate, e. g. regarding low to in Bondaruk 237)

Argument vs adjunct (3) Adam był lingwistą, mieszkając w NH Adam was linguist living in New Haven ‘Adam was a linguist when he lived in New Haven. ’ (4) *Adam to był lingwista, mieszkając w NH Adam TO was linguist living in New Haven (Rutkowski 2006) (But still lots of debate, e. g. regarding low to in Bondaruk 237)

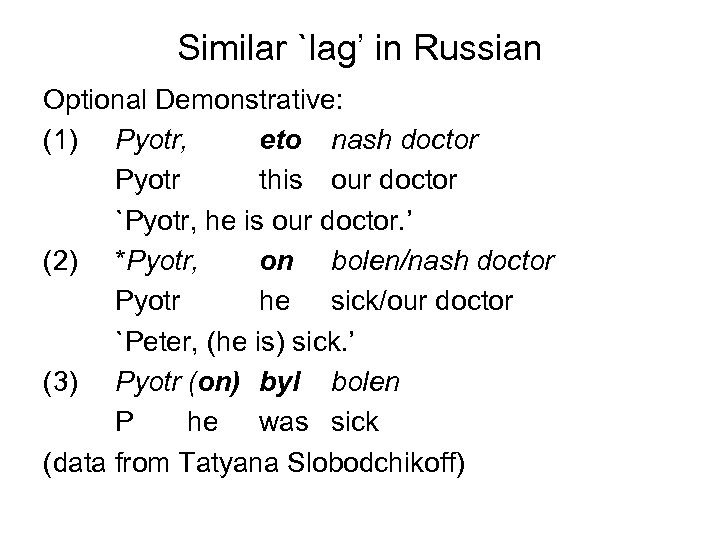

Similar `lag’ in Russian Optional Demonstrative: (1) Pyotr, eto nash doctor Pyotr this our doctor `Pyotr, he is our doctor. ’ (2) *Pyotr, on bolen/nash doctor Pyotr he sick/our doctor `Peter, (he is) sick. ’ (3) Pyotr (on) byl bolen P he was sick (data from Tatyana Slobodchikoff)

Similar `lag’ in Russian Optional Demonstrative: (1) Pyotr, eto nash doctor Pyotr this our doctor `Pyotr, he is our doctor. ’ (2) *Pyotr, on bolen/nash doctor Pyotr he sick/our doctor `Peter, (he is) sick. ’ (3) Pyotr (on) byl bolen P he was sick (data from Tatyana Slobodchikoff)

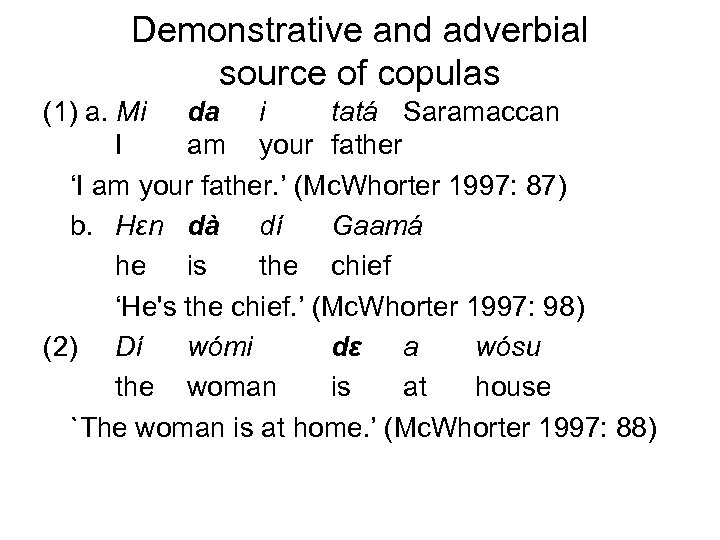

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

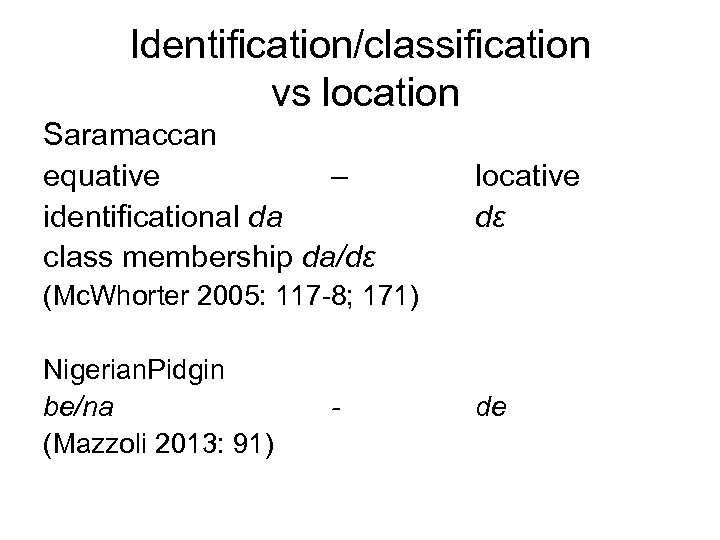

Identification/classification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013: 91) - de

Identification/classification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013: 91) - de

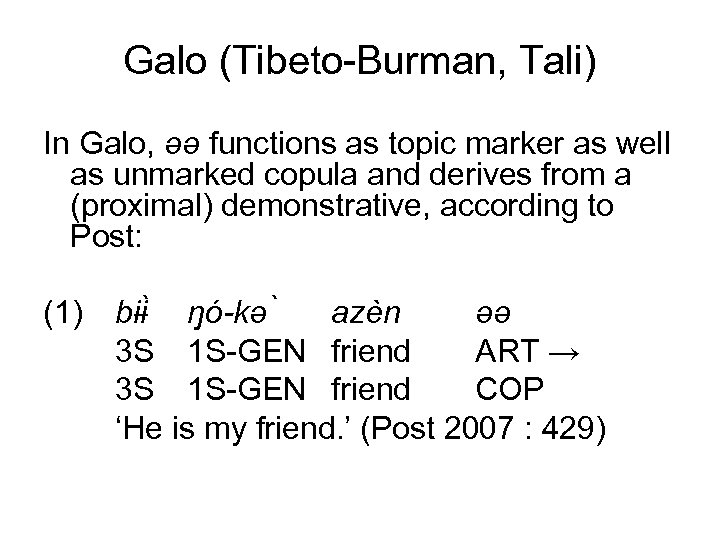

Galo (Tibeto-Burman, Tali) In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative, according to Post: (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007 : 429)

Galo (Tibeto-Burman, Tali) In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative, according to Post: (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007 : 429)

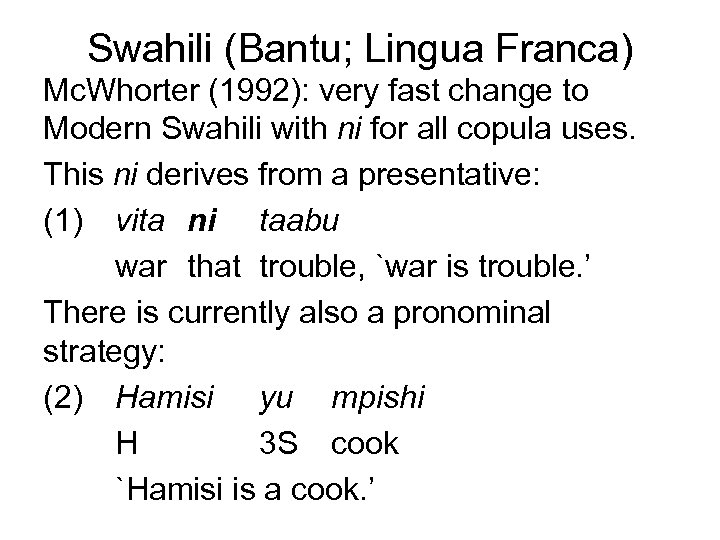

Swahili (Bantu; Lingua Franca) Mc. Whorter (1992): very fast change to Modern Swahili with ni for all copula uses. This ni derives from a presentative: (1) vita ni taabu war that trouble, `war is trouble. ’ There is currently also a pronominal strategy: (2) Hamisi yu mpishi H 3 S cook `Hamisi is a cook. ’

Swahili (Bantu; Lingua Franca) Mc. Whorter (1992): very fast change to Modern Swahili with ni for all copula uses. This ni derives from a presentative: (1) vita ni taabu war that trouble, `war is trouble. ’ There is currently also a pronominal strategy: (2) Hamisi yu mpishi H 3 S cook `Hamisi is a cook. ’

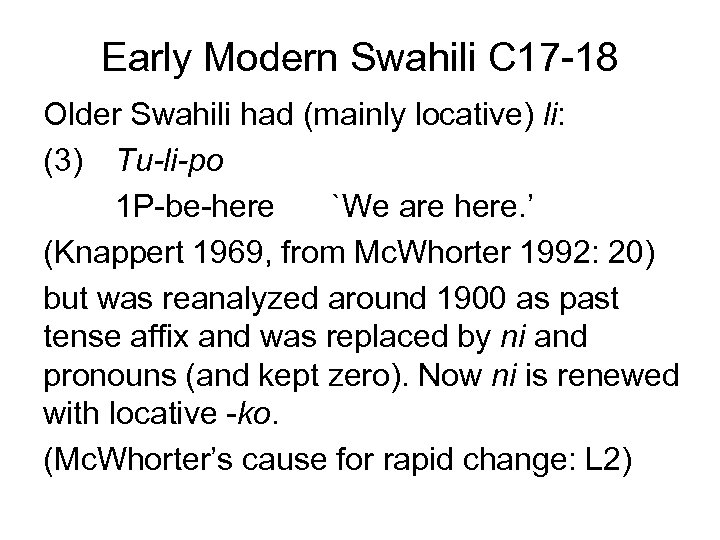

Early Modern Swahili C 17 -18 Older Swahili had (mainly locative) li: (3) Tu-li-po 1 P-be-here `We are here. ’ (Knappert 1969, from Mc. Whorter 1992: 20) but was reanalyzed around 1900 as past tense affix and was replaced by ni and pronouns (and kept zero). Now ni is renewed with locative -ko. (Mc. Whorter’s cause for rapid change: L 2)

Early Modern Swahili C 17 -18 Older Swahili had (mainly locative) li: (3) Tu-li-po 1 P-be-here `We are here. ’ (Knappert 1969, from Mc. Whorter 1992: 20) but was reanalyzed around 1900 as past tense affix and was replaced by ni and pronouns (and kept zero). Now ni is renewed with locative -ko. (Mc. Whorter’s cause for rapid change: L 2)

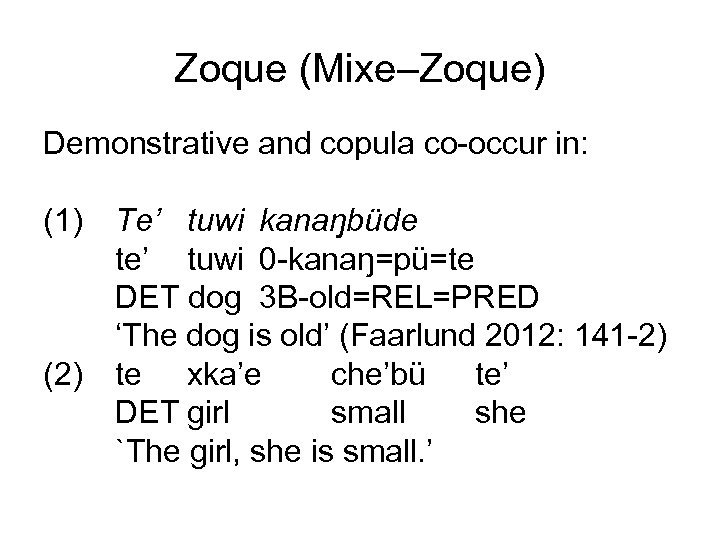

Zoque (Mixe–Zoque) Demonstrative and copula co-occur in: (1) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’ (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2) te xka’e che’bü te’ DET girl small she `The girl, she is small. ’

Zoque (Mixe–Zoque) Demonstrative and copula co-occur in: (1) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’ (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2) te xka’e che’bü te’ DET girl small she `The girl, she is small. ’

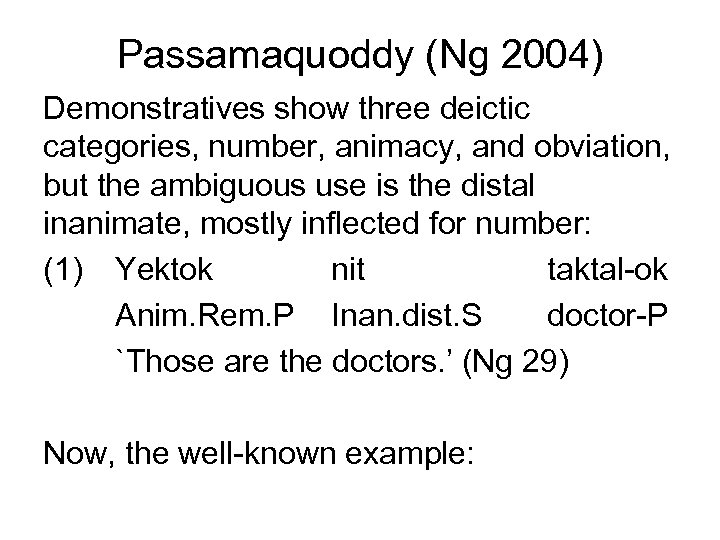

Passamaquoddy (Ng 2004) Demonstratives show three deictic categories, number, animacy, and obviation, but the ambiguous use is the distal inanimate, mostly inflected for number: (1) Yektok nit taktal-ok Anim. Rem. P Inan. dist. S doctor-P `Those are the doctors. ’ (Ng 29) Now, the well-known example:

Passamaquoddy (Ng 2004) Demonstratives show three deictic categories, number, animacy, and obviation, but the ambiguous use is the distal inanimate, mostly inflected for number: (1) Yektok nit taktal-ok Anim. Rem. P Inan. dist. S doctor-P `Those are the doctors. ’ (Ng 29) Now, the well-known example:

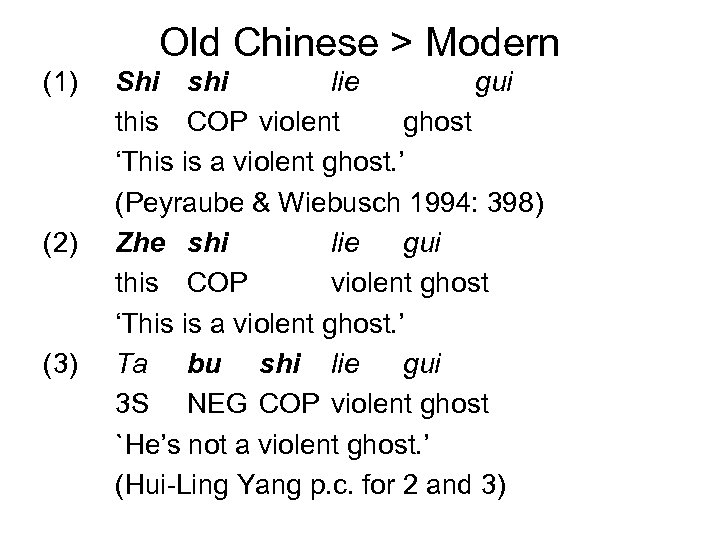

Old Chinese > Modern (1) (2) (3) Shi shi lie gui this COP violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 398) Zhe shi lie gui this COP violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ Ta bu shi lie gui 3 S NEG COP violent ghost `He’s not a violent ghost. ’ (Hui-Ling Yang p. c. for 2 and 3)

Old Chinese > Modern (1) (2) (3) Shi shi lie gui this COP violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 398) Zhe shi lie gui this COP violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ Ta bu shi lie gui 3 S NEG COP violent ghost `He’s not a violent ghost. ’ (Hui-Ling Yang p. c. for 2 and 3)

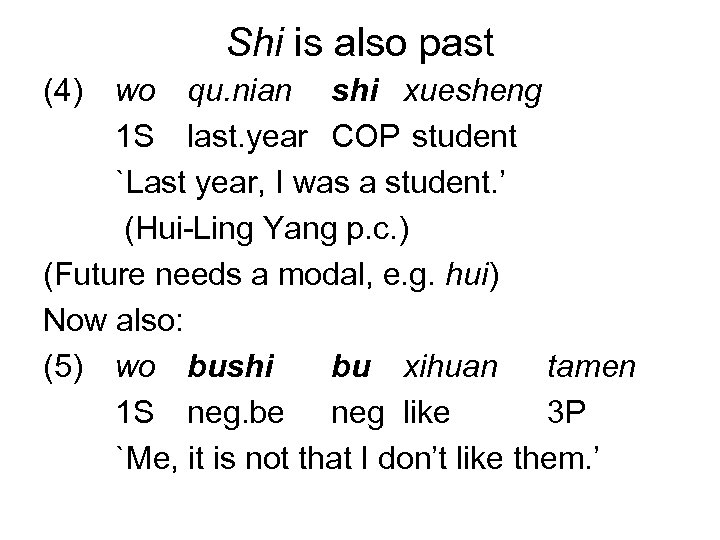

Shi is also past (4) wo qu. nian shi xuesheng 1 S last. year COP student `Last year, I was a student. ’ (Hui-Ling Yang p. c. ) (Future needs a modal, e. g. hui) Now also: (5) wo bushi bu xihuan tamen 1 S neg. be neg like 3 P `Me, it is not that I don’t like them. ’

Shi is also past (4) wo qu. nian shi xuesheng 1 S last. year COP student `Last year, I was a student. ’ (Hui-Ling Yang p. c. ) (Future needs a modal, e. g. hui) Now also: (5) wo bushi bu xihuan tamen 1 S neg. be neg like 3 P `Me, it is not that I don’t like them. ’

![Equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai Equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai](https://present5.com/presentation/35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05/image-40.jpg) Equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai semantic [place] V shi [identity] V zai [location]

Equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai semantic [place] V shi [identity] V zai [location]

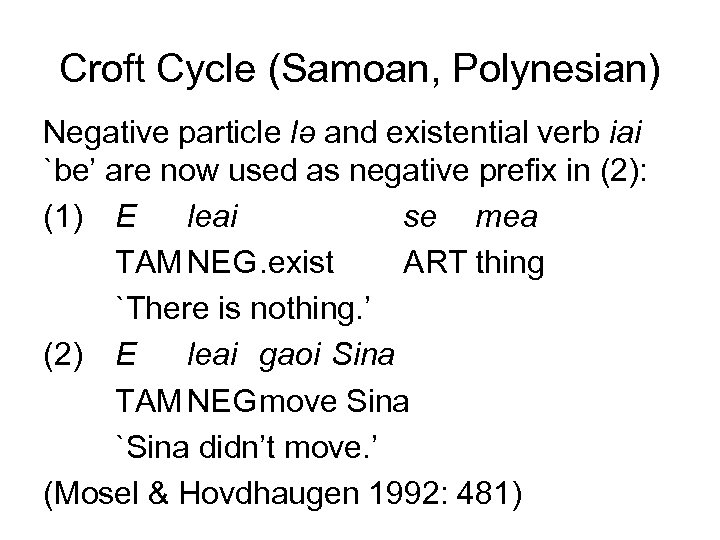

Croft Cycle (Samoan, Polynesian) Negative particle lə and existential verb iai `be’ are now used as negative prefix in (2): (1) E leai se mea TAM NEG. exist ART thing `There is nothing. ’ (2) E leai gaoi Sina TAM NEGmove Sina `Sina didn’t move. ’ (Mosel & Hovdhaugen 1992: 481)

Croft Cycle (Samoan, Polynesian) Negative particle lə and existential verb iai `be’ are now used as negative prefix in (2): (1) E leai se mea TAM NEG. exist ART thing `There is nothing. ’ (2) E leai gaoi Sina TAM NEGmove Sina `Sina didn’t move. ’ (Mosel & Hovdhaugen 1992: 481)

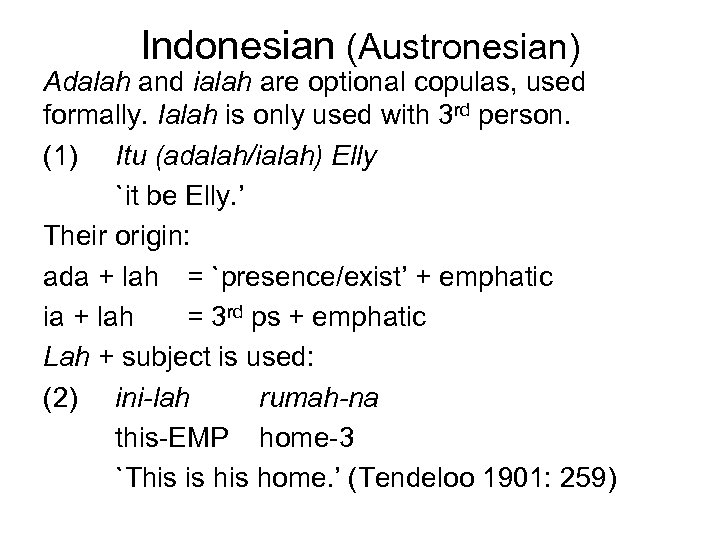

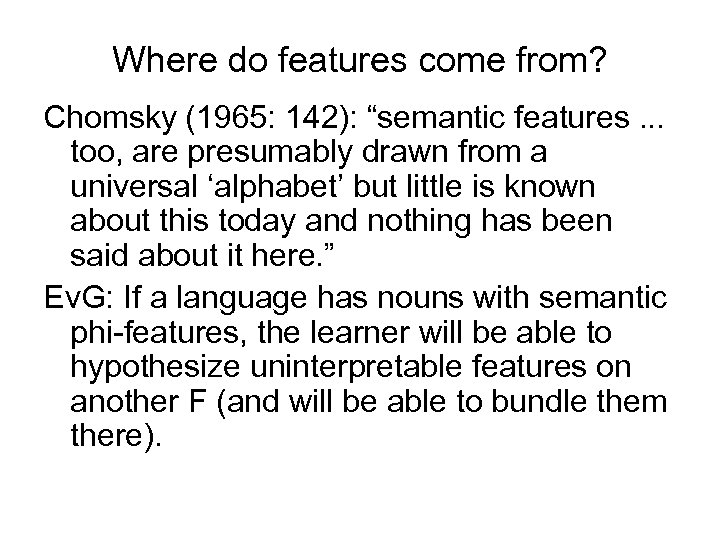

Indonesian (Austronesian) Adalah and ialah are optional copulas, used formally. Ialah is only used with 3 rd person. (1) Itu (adalah/ialah) Elly `it be Elly. ’ Their origin: ada + lah = `presence/exist’ + emphatic ia + lah = 3 rd ps + emphatic Lah + subject is used: (2) ini-lah rumah-na this-EMP home-3 `This is home. ’ (Tendeloo 1901: 259)

Indonesian (Austronesian) Adalah and ialah are optional copulas, used formally. Ialah is only used with 3 rd person. (1) Itu (adalah/ialah) Elly `it be Elly. ’ Their origin: ada + lah = `presence/exist’ + emphatic ia + lah = 3 rd ps + emphatic Lah + subject is used: (2) ini-lah rumah-na this-EMP home-3 `This is home. ’ (Tendeloo 1901: 259)

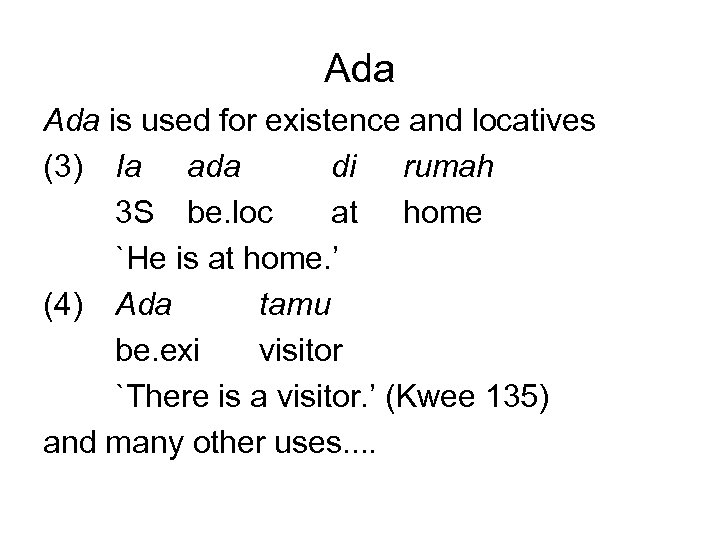

Ada is used for existence and locatives (3) Ia ada di rumah 3 S be. loc at home `He is at home. ’ (4) Ada tamu be. exi visitor `There is a visitor. ’ (Kwee 135) and many other uses. .

Ada is used for existence and locatives (3) Ia ada di rumah 3 S be. loc at home `He is at home. ’ (4) Ada tamu be. exi visitor `There is a visitor. ’ (Kwee 135) and many other uses. .

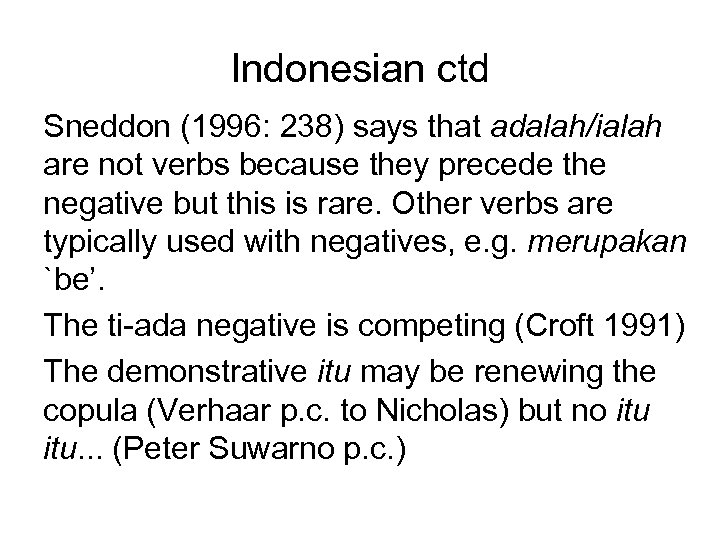

Indonesian ctd Sneddon (1996: 238) says that adalah/ialah are not verbs because they precede the negative but this is rare. Other verbs are typically used with negatives, e. g. merupakan `be’. The ti-ada negative is competing (Croft 1991) The demonstrative itu may be renewing the copula (Verhaar p. c. to Nicholas) but no itu. . . (Peter Suwarno p. c. )

Indonesian ctd Sneddon (1996: 238) says that adalah/ialah are not verbs because they precede the negative but this is rare. Other verbs are typically used with negatives, e. g. merupakan `be’. The ti-ada negative is competing (Croft 1991) The demonstrative itu may be renewing the copula (Verhaar p. c. to Nicholas) but no itu. . . (Peter Suwarno p. c. )

![Indonesian copulas - ia + lah > be [i-3] EMP [i-3] ada (+ lah) Indonesian copulas - ia + lah > be [i-3] EMP [i-3] ada (+ lah)](https://present5.com/presentation/35566660caf6dab64aecb17f9bcc1d05/image-45.jpg) Indonesian copulas - ia + lah > be [i-3] EMP [i-3] ada (+ lah) > be negative `be’ tiada > negative itu > ? merupakan

Indonesian copulas - ia + lah > be [i-3] EMP [i-3] ada (+ lah) > be negative `be’ tiada > negative itu > ? merupakan

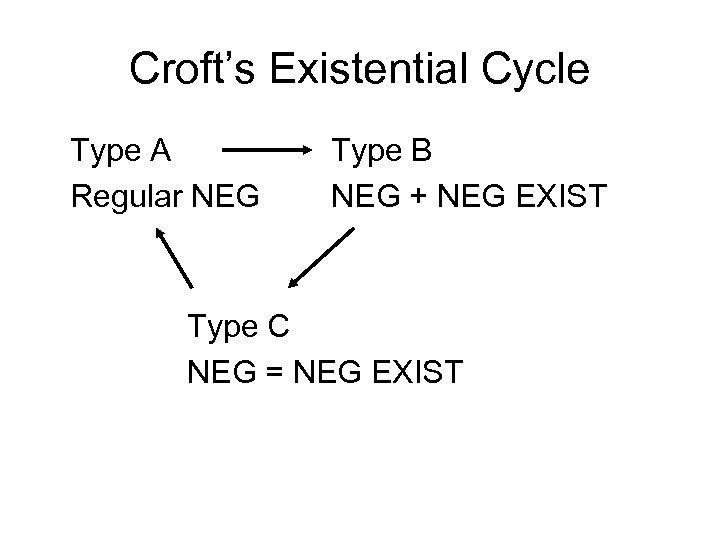

Croft’s Existential Cycle Type A Regular NEG Type B NEG + NEG EXIST Type C NEG = NEG EXIST

Croft’s Existential Cycle Type A Regular NEG Type B NEG + NEG EXIST Type C NEG = NEG EXIST

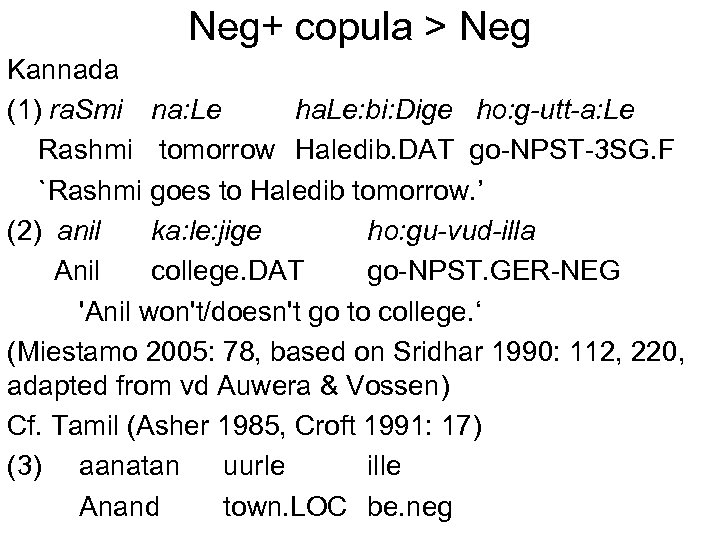

Neg+ copula > Neg Kannada (1) ra. Smi na: Le ha. Le: bi: Dige ho: g-utt-a: Le Rashmi tomorrow Haledib. DAT go-NPST-3 SG. F `Rashmi goes to Haledib tomorrow. ’ (2) anil ka: le: jige ho: gu-vud-illa Anil college. DAT go-NPST. GER-NEG 'Anil won't/doesn't go to college. ‘ (Miestamo 2005: 78, based on Sridhar 1990: 112, 220, adapted from vd Auwera & Vossen) Cf. Tamil (Asher 1985, Croft 1991: 17) (3) aanatan uurle ille Anand town. LOC be. neg

Neg+ copula > Neg Kannada (1) ra. Smi na: Le ha. Le: bi: Dige ho: g-utt-a: Le Rashmi tomorrow Haledib. DAT go-NPST-3 SG. F `Rashmi goes to Haledib tomorrow. ’ (2) anil ka: le: jige ho: gu-vud-illa Anil college. DAT go-NPST. GER-NEG 'Anil won't/doesn't go to college. ‘ (Miestamo 2005: 78, based on Sridhar 1990: 112, 220, adapted from vd Auwera & Vossen) Cf. Tamil (Asher 1985, Croft 1991: 17) (3) aanatan uurle ille Anand town. LOC be. neg

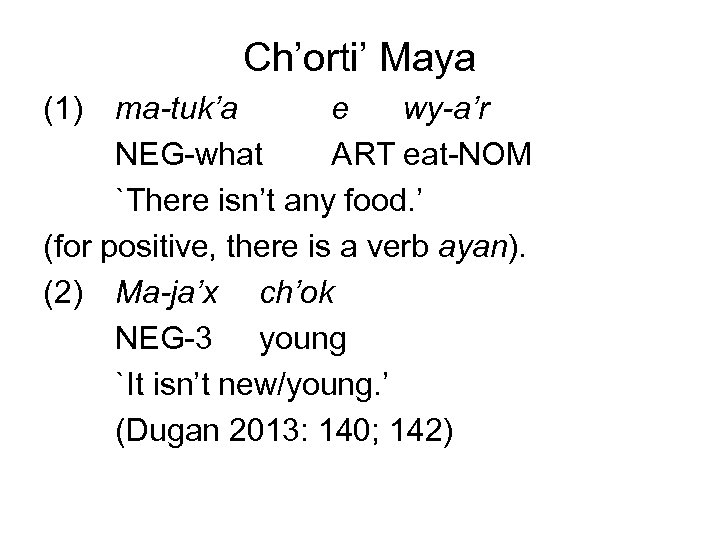

Ch’orti’ Maya (1) ma-tuk’a e wy-a’r NEG-what ART eat-NOM `There isn’t any food. ’ (for positive, there is a verb ayan). (2) Ma-ja’x ch’ok NEG-3 young `It isn’t new/young. ’ (Dugan 2013: 140; 142)

Ch’orti’ Maya (1) ma-tuk’a e wy-a’r NEG-what ART eat-NOM `There isn’t any food. ’ (for positive, there is a verb ayan). (2) Ma-ja’x ch’ok NEG-3 young `It isn’t new/young. ’ (Dugan 2013: 140; 142)

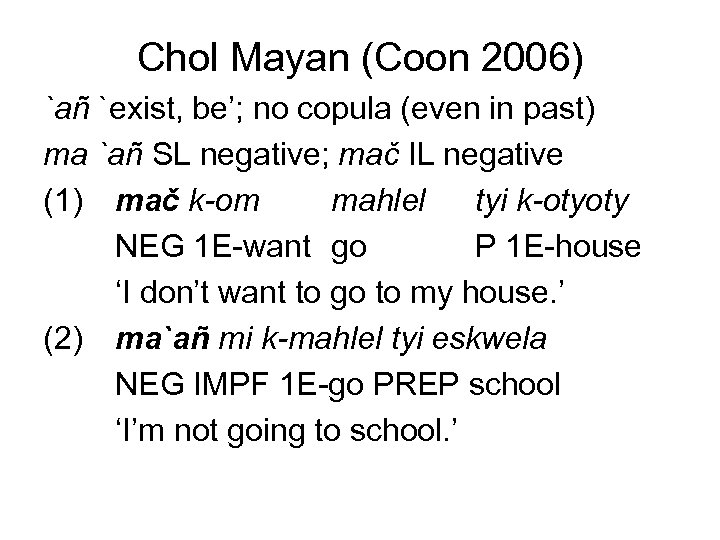

Chol Mayan (Coon 2006) `añ `exist, be’; no copula (even in past) ma `añ SL negative; mač IL negative (1) mač k-om mahlel tyi k-otyoty NEG 1 E-want go P 1 E-house ‘I don’t want to go to my house. ’ (2) ma`añ mi k-mahlel tyi eskwela NEG IMPF 1 E-go PREP school ‘I’m not going to school. ’

Chol Mayan (Coon 2006) `añ `exist, be’; no copula (even in past) ma `añ SL negative; mač IL negative (1) mač k-om mahlel tyi k-otyoty NEG 1 E-want go P 1 E-house ‘I don’t want to go to my house. ’ (2) ma`añ mi k-mahlel tyi eskwela NEG IMPF 1 E-go PREP school ‘I’m not going to school. ’

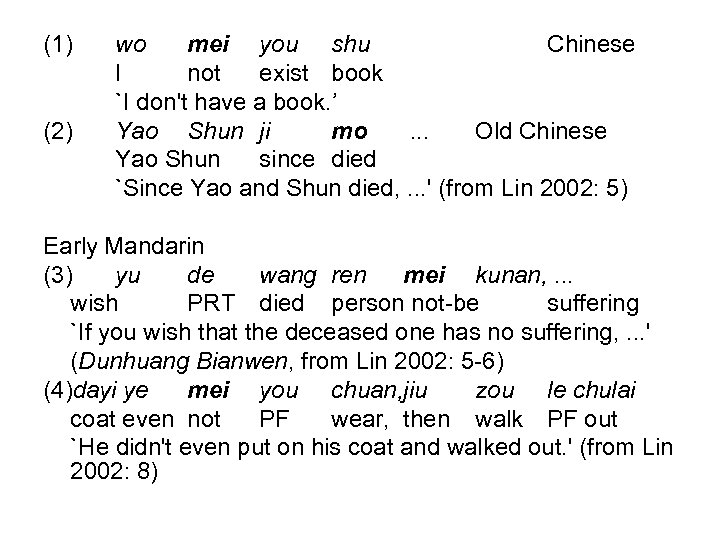

(1) (2) wo mei you shu Chinese I not exist book `I don't have a book. ’ Yao Shun ji mo. . . Old Chinese Yao Shun since died `Since Yao and Shun died, . . . ' (from Lin 2002: 5) Early Mandarin (3) yu de wang ren mei kunan, . . . wish PRT died person not-be suffering `If you wish that the deceased one has no suffering, . . . ' (Dunhuang Bianwen, from Lin 2002: 5 -6) (4)dayi ye mei you chuan, jiu zou le chulai coat even not PF wear, then walk PF out `He didn't even put on his coat and walked out. ' (from Lin 2002: 8)

(1) (2) wo mei you shu Chinese I not exist book `I don't have a book. ’ Yao Shun ji mo. . . Old Chinese Yao Shun since died `Since Yao and Shun died, . . . ' (from Lin 2002: 5) Early Mandarin (3) yu de wang ren mei kunan, . . . wish PRT died person not-be suffering `If you wish that the deceased one has no suffering, . . . ' (Dunhuang Bianwen, from Lin 2002: 5 -6) (4)dayi ye mei you chuan, jiu zou le chulai coat even not PF wear, then walk PF out `He didn't even put on his coat and walked out. ' (from Lin 2002: 8)

Mei < `not be’

Mei < `not be’

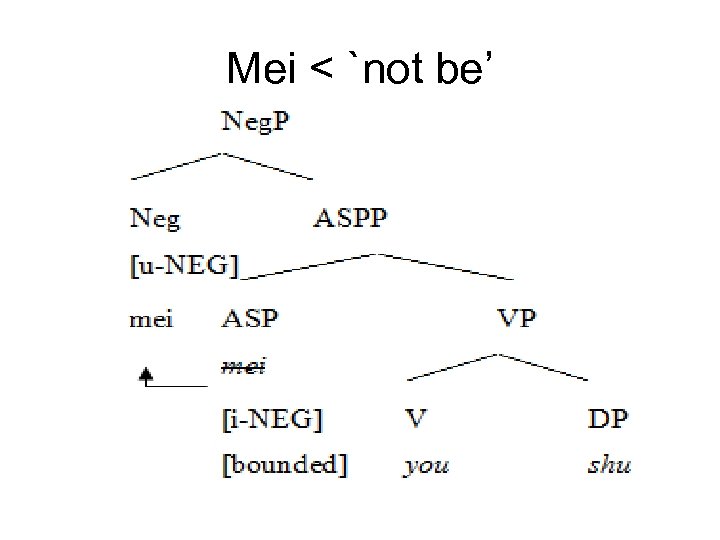

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier Head (of Neg. P) affix semantic > [i-NEG]> [u-NEG] > -Modal Cycle Verb > AUX [volition, expectation, future] [future] Copula Cycle Demonstrative > copula [loc, id, i-phi] [loc, id] or [u-phi]

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier Head (of Neg. P) affix semantic > [i-NEG]> [u-NEG] > -Modal Cycle Verb > AUX [volition, expectation, future] [future] Copula Cycle Demonstrative > copula [loc, id, i-phi] [loc, id] or [u-phi]

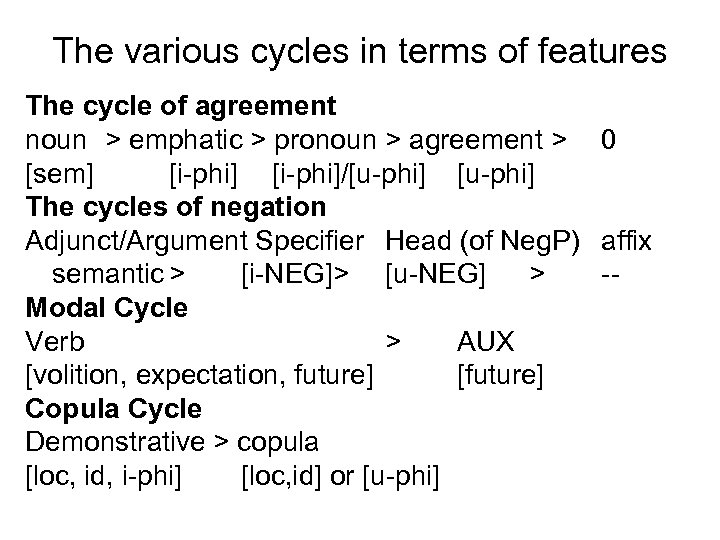

Where do features come from? Chomsky (1965: 142): “semantic features. . . too, are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’ but little is known about this today and nothing has been said about it here. ” Ev. G: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

Where do features come from? Chomsky (1965: 142): “semantic features. . . too, are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’ but little is known about this today and nothing has been said about it here. ” Ev. G: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

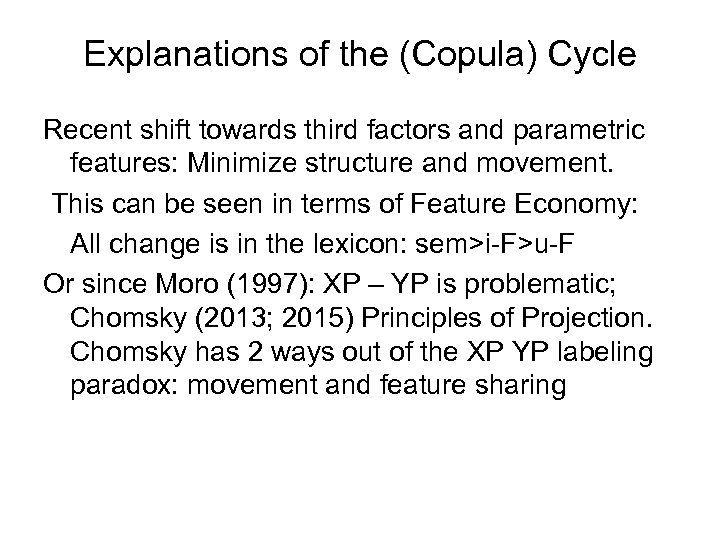

Explanations of the (Copula) Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: Minimize structure and movement. This can be seen in terms of Feature Economy: All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Or since Moro (1997): XP – YP is problematic; Chomsky (2013; 2015) Principles of Projection. Chomsky has 2 ways out of the XP YP labeling paradox: movement and feature sharing

Explanations of the (Copula) Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: Minimize structure and movement. This can be seen in terms of Feature Economy: All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Or since Moro (1997): XP – YP is problematic; Chomsky (2013; 2015) Principles of Projection. Chomsky has 2 ways out of the XP YP labeling paradox: movement and feature sharing

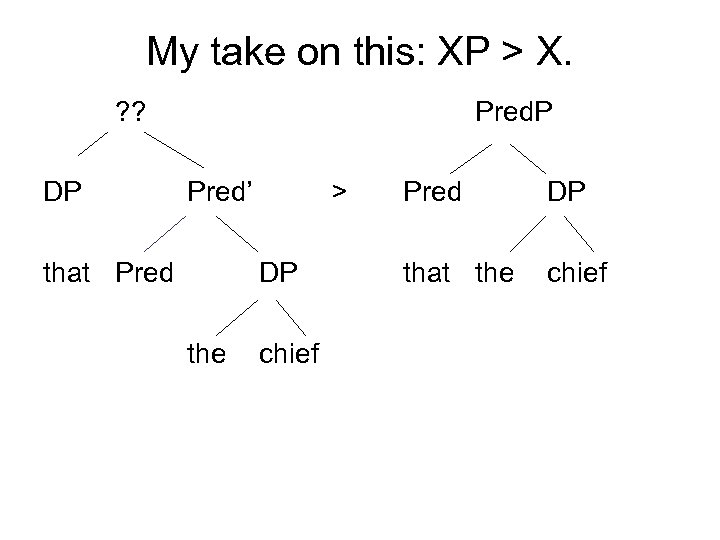

My take on this: XP > X. ? ? DP Pred’ that Pred > DP the chief Pred DP that the chief

My take on this: XP > X. ? ? DP Pred’ that Pred > DP the chief Pred DP that the chief

Conclusions Unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty. Cycles are relevant to gain insight into features and structural economy. Which are the features that need renewal Why is Spec > head so prevalent? Labeling? .

Conclusions Unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty. Cycles are relevant to gain insight into features and structural economy. Which are the features that need renewal Why is Spec > head so prevalent? Labeling? .

Selected References Alsaeedi, Mekhlid 2015. The Rise of New Copulas in Arabic. ASU MA. Benveniste, Emile 1960. The linguistic functions of to be and to have. In Problems in General Linguistics. Bondaruk, Anna 2013. Copular Clauses in English and Polish. Lublin. Chomsky, Noam 2013 Problems of Projection. Lingua. Chomsky, Noam 2014 Problems of Projection: Extensions. Croft, William 1991. The Evolution of negation. Journal of Linguistics 27: 1 -27. Curme, George 1935. Parts of Speech and Accidence. D. C. Heath. Eid, M. 1983. The copula function of pronouns. Lingua 59: 197 -207. Faarlund, Jan Terje 2012. A Grammar of Chiapas Zoque. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Selected References Alsaeedi, Mekhlid 2015. The Rise of New Copulas in Arabic. ASU MA. Benveniste, Emile 1960. The linguistic functions of to be and to have. In Problems in General Linguistics. Bondaruk, Anna 2013. Copular Clauses in English and Polish. Lublin. Chomsky, Noam 2013 Problems of Projection. Lingua. Chomsky, Noam 2014 Problems of Projection: Extensions. Croft, William 1991. The Evolution of negation. Journal of Linguistics 27: 1 -27. Curme, George 1935. Parts of Speech and Accidence. D. C. Heath. Eid, M. 1983. The copula function of pronouns. Lingua 59: 197 -207. Faarlund, Jan Terje 2012. A Grammar of Chiapas Zoque. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Faltz, Aryeh 1973. Surrogate Copulas in Hebrew. ms. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences 13: 1 -7. Katz, Aya 1996. Cyclical Grammaticalization and the Cognitive Link between Pronoun and Copula. Rice Dissertation. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford University Press. Korn, Agnes 2011. Pronouns as Verbs. In Korn et al. Wiesbaden; Reichert. Li, Charles, and Sandra Thompson 1977. A mechanism for the development of copula morphemes. In Charles Li (ed. ), Mechanisms of syntactic change, 414 -444. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Faltz, Aryeh 1973. Surrogate Copulas in Hebrew. ms. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences 13: 1 -7. Katz, Aya 1996. Cyclical Grammaticalization and the Cognitive Link between Pronoun and Copula. Rice Dissertation. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford University Press. Korn, Agnes 2011. Pronouns as Verbs. In Korn et al. Wiesbaden; Reichert. Li, Charles, and Sandra Thompson 1977. A mechanism for the development of copula morphemes. In Charles Li (ed. ), Mechanisms of syntactic change, 414 -444. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Mazzoli, Maria 2013. Copulas in Nigerian Pidgin. Padova dissertation. Mc. Whorter, John 2005. Defining Creole. OUP. Mc. Whorter, John 1994. From Focus Marker to Copula in Swahili. Berkeley Linguistics Society: 57 -66. ion. Berlin: Mouton. Miestamo, Matti 2005. Standard Negat Mosel, Ulrike & Even Hovdhaugen 1992. Samoan Reference Grammar. Oslo. Petré, Peter 2014. Constructions and environments. OUP. Post, Mark 2007. A Grammar of Galo. La Trobe Dissertation. Pustet, Regina. 2003. Copulas: Universals in the Categorization of the Lexicon. Oxford: OUP. Stassen, Leon 1997. Intransitive Predication. OUP. Yang, Hui-Ling 2012.

Mazzoli, Maria 2013. Copulas in Nigerian Pidgin. Padova dissertation. Mc. Whorter, John 2005. Defining Creole. OUP. Mc. Whorter, John 1994. From Focus Marker to Copula in Swahili. Berkeley Linguistics Society: 57 -66. ion. Berlin: Mouton. Miestamo, Matti 2005. Standard Negat Mosel, Ulrike & Even Hovdhaugen 1992. Samoan Reference Grammar. Oslo. Petré, Peter 2014. Constructions and environments. OUP. Post, Mark 2007. A Grammar of Galo. La Trobe Dissertation. Pustet, Regina. 2003. Copulas: Universals in the Categorization of the Lexicon. Oxford: OUP. Stassen, Leon 1997. Intransitive Predication. OUP. Yang, Hui-Ling 2012.