8fe2e573d7a7966aa61897f9a3d9ced4.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 58

The Copula Cycle and semantic features Elly van Gelderen 13 -14 March 2014 Bologna, Copula Workshop

The Copula Cycle and semantic features Elly van Gelderen 13 -14 March 2014 Bologna, Copula Workshop

Outline A. B. C. D. A little on generative historical syntax Examples of Grammaticalization and Linguistic Cycles Copula Cycles D, V, and P/A are the sources Explanations in terms of features and some challenges.

Outline A. B. C. D. A little on generative historical syntax Examples of Grammaticalization and Linguistic Cycles Copula Cycles D, V, and P/A are the sources Explanations in terms of features and some challenges.

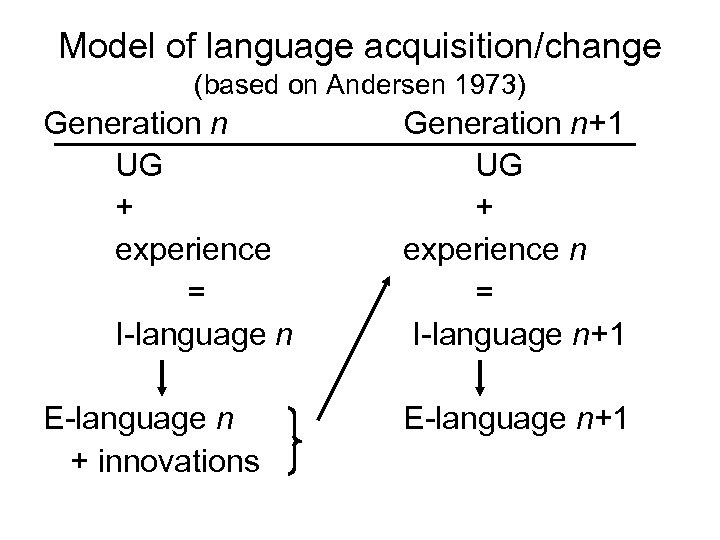

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Model of language acquisition/change (based on Andersen 1973) Generation n UG + experience = I-language n E-language n + innovations Generation n+1 UG + experience n = I-language n+1 E-language n+1

Internal Grammar

Internal Grammar

Reanalysis is crucial (1) Paul said, "Starting would be a good thing to do. How would you like to begin? “ (COCA 2010 Fiction) (cartoon is on Handout)

Reanalysis is crucial (1) Paul said, "Starting would be a good thing to do. How would you like to begin? “ (COCA 2010 Fiction) (cartoon is on Handout)

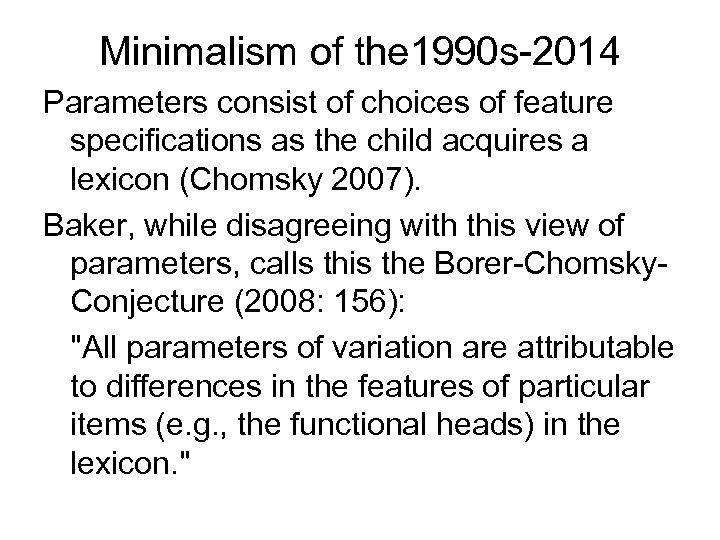

Minimalism of the 1990 s-2014 Parameters consist of choices of feature specifications as the child acquires a lexicon (Chomsky 2007). Baker, while disagreeing with this view of parameters, calls this the Borer-Chomsky. Conjecture (2008: 156): "All parameters of variation are attributable to differences in the features of particular items (e. g. , the functional heads) in the lexicon. "

Minimalism of the 1990 s-2014 Parameters consist of choices of feature specifications as the child acquires a lexicon (Chomsky 2007). Baker, while disagreeing with this view of parameters, calls this the Borer-Chomsky. Conjecture (2008: 156): "All parameters of variation are attributable to differences in the features of particular items (e. g. , the functional heads) in the lexicon. "

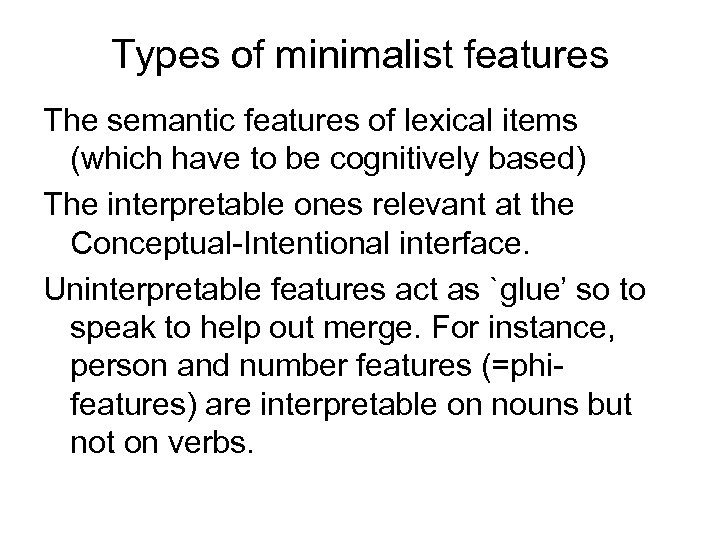

Types of minimalist features The semantic features of lexical items (which have to be cognitively based) The interpretable ones relevant at the Conceptual-Intentional interface. Uninterpretable features act as `glue’ so to speak to help out merge. For instance, person and number features (=phifeatures) are interpretable on nouns but not on verbs.

Types of minimalist features The semantic features of lexical items (which have to be cognitively based) The interpretable ones relevant at the Conceptual-Intentional interface. Uninterpretable features act as `glue’ so to speak to help out merge. For instance, person and number features (=phifeatures) are interpretable on nouns but not on verbs.

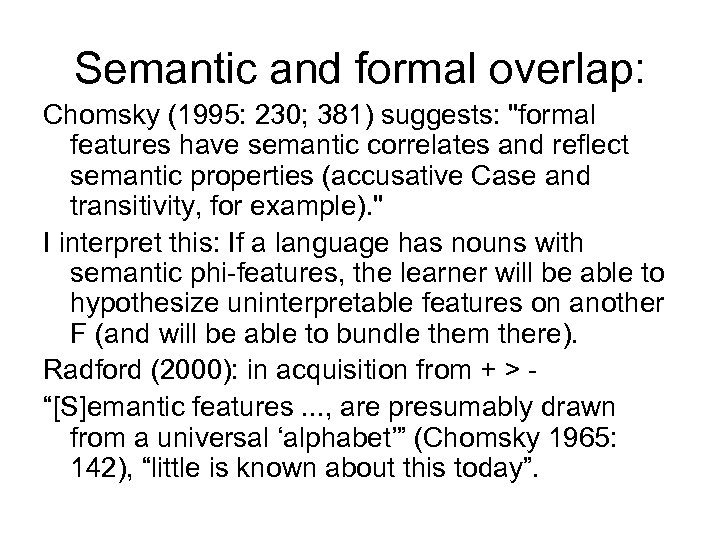

Semantic and formal overlap: Chomsky (1995: 230; 381) suggests: "formal features have semantic correlates and reflect semantic properties (accusative Case and transitivity, for example). " I interpret this: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there). Radford (2000): in acquisition from + > “[S]emantic features. . . , are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’” (Chomsky 1965: 142), “little is known about this today”.

Semantic and formal overlap: Chomsky (1995: 230; 381) suggests: "formal features have semantic correlates and reflect semantic properties (accusative Case and transitivity, for example). " I interpret this: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there). Radford (2000): in acquisition from + > “[S]emantic features. . . , are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’” (Chomsky 1965: 142), “little is known about this today”.

If semantic features are innate, we need: Feature Economy (a) Utilize semantic features: use them as for functional categories, i. e. as formal features (van Gelderen 2008; 2011). (b) If a specific feature appears more than once, one of these is interpretable and the others are uninterpretable (Muysken 2008).

If semantic features are innate, we need: Feature Economy (a) Utilize semantic features: use them as for functional categories, i. e. as formal features (van Gelderen 2008; 2011). (b) If a specific feature appears more than once, one of these is interpretable and the others are uninterpretable (Muysken 2008).

Three factors are relevant to the Fac of Lg, e. g. Chomsky 2007 (1) genetic endowment, which sets limits on the attainable languages, thereby making language acquisition possible; (2) external data, converted to the experience that selects one or another language within a narrow range; (3) principles not specific to the Faculty of Language. Some of the third factor principles have the flavor of the constraints that enter into all facets of growth and evolution, [. . . ] Among these are principles of efficient computation"

Three factors are relevant to the Fac of Lg, e. g. Chomsky 2007 (1) genetic endowment, which sets limits on the attainable languages, thereby making language acquisition possible; (2) external data, converted to the experience that selects one or another language within a narrow range; (3) principles not specific to the Faculty of Language. Some of the third factor principles have the flavor of the constraints that enter into all facets of growth and evolution, [. . . ] Among these are principles of efficient computation"

Economy Locality = Minimize computational burden (Ross 1967; Chomsky 1973) Use a head = Minimize Structure (Head Preference Principle, van Gelderen 2004) Late Merge = Minimize computational burden (van Gelderen 2004, and others) The latter two can be seen in terms of Feature Economy

Economy Locality = Minimize computational burden (Ross 1967; Chomsky 1973) Use a head = Minimize Structure (Head Preference Principle, van Gelderen 2004) Late Merge = Minimize computational burden (van Gelderen 2004, and others) The latter two can be seen in terms of Feature Economy

Grammaticalization is a unidirectional change from semantic to formal (=grammatical) features. For instance, a verb with semantic features, such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical feature [future]. And a pronoun can be reanalyzed as agreement on the verb.

Grammaticalization is a unidirectional change from semantic to formal (=grammatical) features. For instance, a verb with semantic features, such as Old English will with [volition, expectation, future], can be reanalyzed as having only the grammatical feature [future]. And a pronoun can be reanalyzed as agreement on the verb.

![Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] copula Dem C article [u-phi] [i-phi] Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] copula Dem C article [u-phi] [i-phi]](https://present5.com/presentation/8fe2e573d7a7966aa61897f9a3d9ced4/image-13.jpg) Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] copula Dem C article [u-phi] [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree adverb and tense marker (Tibeto. Burman) and noun class marker.

Greenberg’s Demonstrative Cycle and additions Demonstrative [i-phi]/ [loc] copula Dem C article [u-phi] [i-phi] [u/i-T] [u-phi] [loc] Also: degree adverb and tense marker (Tibeto. Burman) and noun class marker.

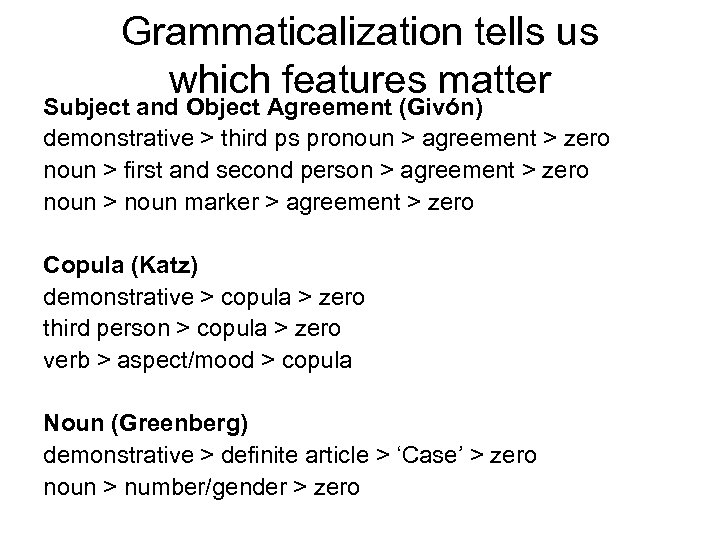

Grammaticalization tells us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero noun > noun marker > agreement > zero Copula (Katz) demonstrative > copula > zero third person > copula > zero verb > aspect/mood > copula Noun (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

Grammaticalization tells us which features matter Subject and Object Agreement (Givón) demonstrative > third ps pronoun > agreement > zero noun > first and second person > agreement > zero noun > noun marker > agreement > zero Copula (Katz) demonstrative > copula > zero third person > copula > zero verb > aspect/mood > copula Noun (Greenberg) demonstrative > definite article > ‘Case’ > zero noun > number/gender > zero

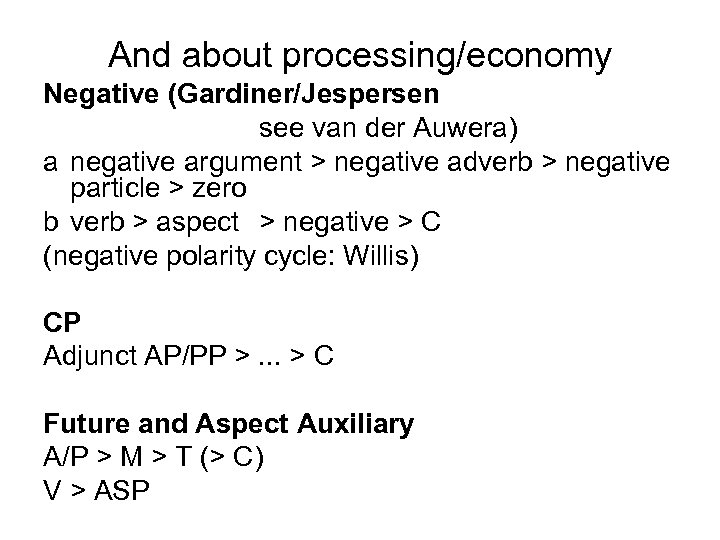

And about processing/economy Negative (Gardiner/Jespersen see van der Auwera) a negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero b verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

And about processing/economy Negative (Gardiner/Jespersen see van der Auwera) a negative argument > negative adverb > negative particle > zero b verb > aspect > negative > C (negative polarity cycle: Willis) CP Adjunct AP/PP >. . . > C Future and Aspect Auxiliary A/P > M > T (> C) V > ASP

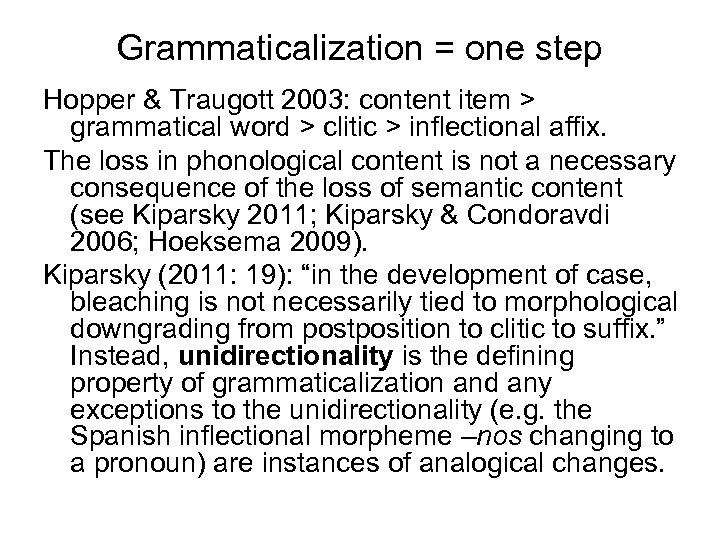

Grammaticalization = one step Hopper & Traugott 2003: content item > grammatical word > clitic > inflectional affix. The loss in phonological content is not a necessary consequence of the loss of semantic content (see Kiparsky 2011; Kiparsky & Condoravdi 2006; Hoeksema 2009). Kiparsky (2011: 19): “in the development of case, bleaching is not necessarily tied to morphological downgrading from postposition to clitic to suffix. ” Instead, unidirectionality is the defining property of grammaticalization and any exceptions to the unidirectionality (e. g. the Spanish inflectional morpheme –nos changing to a pronoun) are instances of analogical changes.

Grammaticalization = one step Hopper & Traugott 2003: content item > grammatical word > clitic > inflectional affix. The loss in phonological content is not a necessary consequence of the loss of semantic content (see Kiparsky 2011; Kiparsky & Condoravdi 2006; Hoeksema 2009). Kiparsky (2011: 19): “in the development of case, bleaching is not necessarily tied to morphological downgrading from postposition to clitic to suffix. ” Instead, unidirectionality is the defining property of grammaticalization and any exceptions to the unidirectionality (e. g. the Spanish inflectional morpheme –nos changing to a pronoun) are instances of analogical changes.

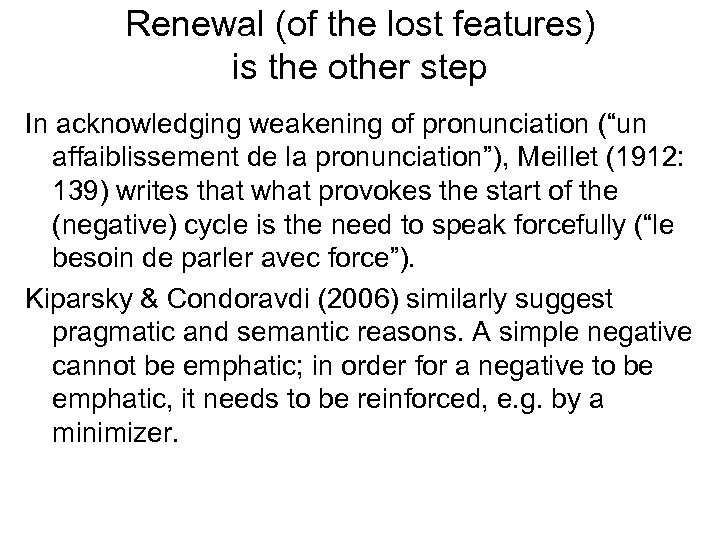

Renewal (of the lost features) is the other step In acknowledging weakening of pronunciation (“un affaiblissement de la pronunciation”), Meillet (1912: 139) writes that what provokes the start of the (negative) cycle is the need to speak forcefully (“le besoin de parler avec force”). Kiparsky & Condoravdi (2006) similarly suggest pragmatic and semantic reasons. A simple negative cannot be emphatic; in order for a negative to be emphatic, it needs to be reinforced, e. g. by a minimizer.

Renewal (of the lost features) is the other step In acknowledging weakening of pronunciation (“un affaiblissement de la pronunciation”), Meillet (1912: 139) writes that what provokes the start of the (negative) cycle is the need to speak forcefully (“le besoin de parler avec force”). Kiparsky & Condoravdi (2006) similarly suggest pragmatic and semantic reasons. A simple negative cannot be emphatic; in order for a negative to be emphatic, it needs to be reinforced, e. g. by a minimizer.

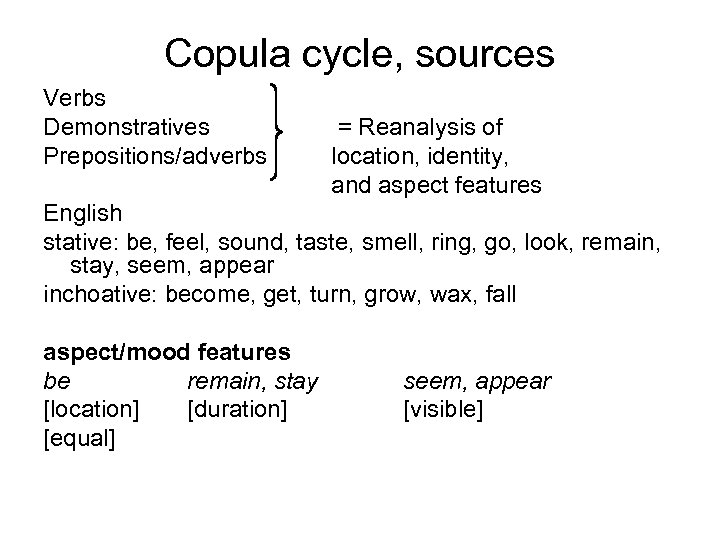

Copula cycle, sources Verbs Demonstratives Prepositions/adverbs = Reanalysis of location, identity, and aspect features English stative: be, feel, sound, taste, smell, ring, go, look, remain, stay, seem, appear inchoative: become, get, turn, grow, wax, fall aspect/mood features be remain, stay [location] [duration] [equal] seem, appear [visible]

Copula cycle, sources Verbs Demonstratives Prepositions/adverbs = Reanalysis of location, identity, and aspect features English stative: be, feel, sound, taste, smell, ring, go, look, remain, stay, seem, appear inchoative: become, get, turn, grow, wax, fall aspect/mood features be remain, stay [location] [duration] [equal] seem, appear [visible]

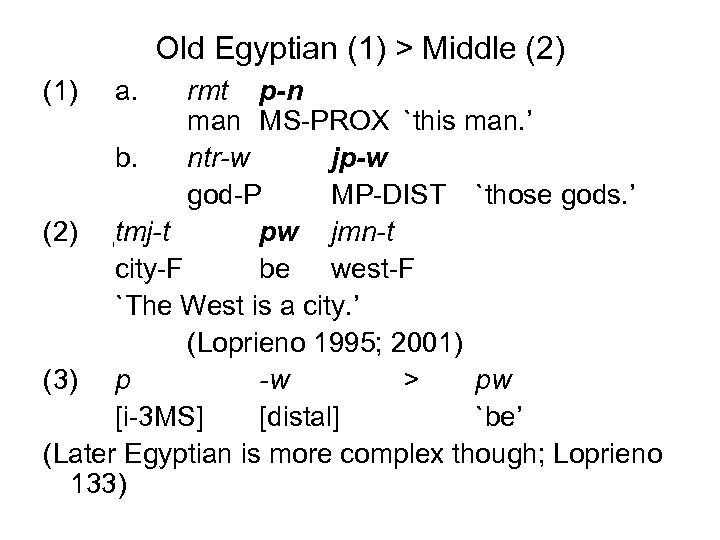

Old Egyptian (1) > Middle (2) (1) a. rmt p-n man MS-PROX `this man. ’ b. ntr-w jp-w god-P MP-DIST `those gods. ’ (2) tmj-t pw jmn-t city-F be west-F `The West is a city. ’ (Loprieno 1995; 2001) (3) p -w > pw [i-3 MS] [distal] `be’ (Later Egyptian is more complex though; Loprieno 133)

Old Egyptian (1) > Middle (2) (1) a. rmt p-n man MS-PROX `this man. ’ b. ntr-w jp-w god-P MP-DIST `those gods. ’ (2) tmj-t pw jmn-t city-F be west-F `The West is a city. ’ (Loprieno 1995; 2001) (3) p -w > pw [i-3 MS] [distal] `be’ (Later Egyptian is more complex though; Loprieno 133)

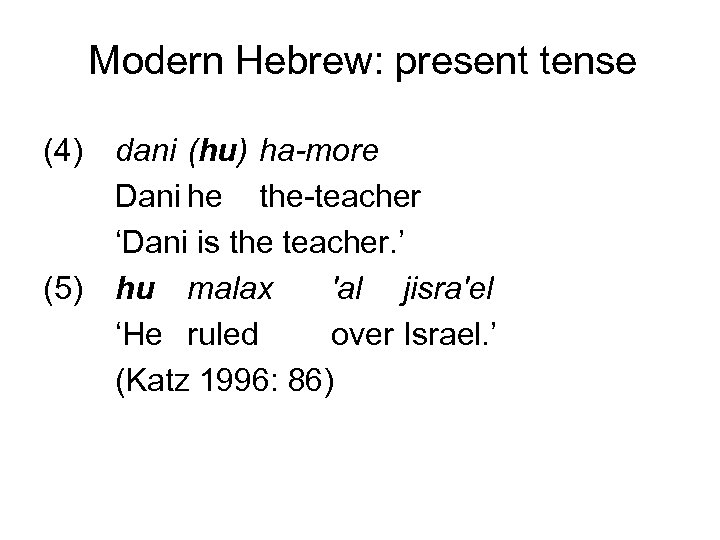

Modern Hebrew: present tense (4) (5) dani (hu) ha-more Dani he the-teacher ‘Dani is the teacher. ’ hu malax 'al jisra'el ‘He ruled over Israel. ’ (Katz 1996: 86)

Modern Hebrew: present tense (4) (5) dani (hu) ha-more Dani he the-teacher ‘Dani is the teacher. ’ hu malax 'al jisra'el ‘He ruled over Israel. ’ (Katz 1996: 86)

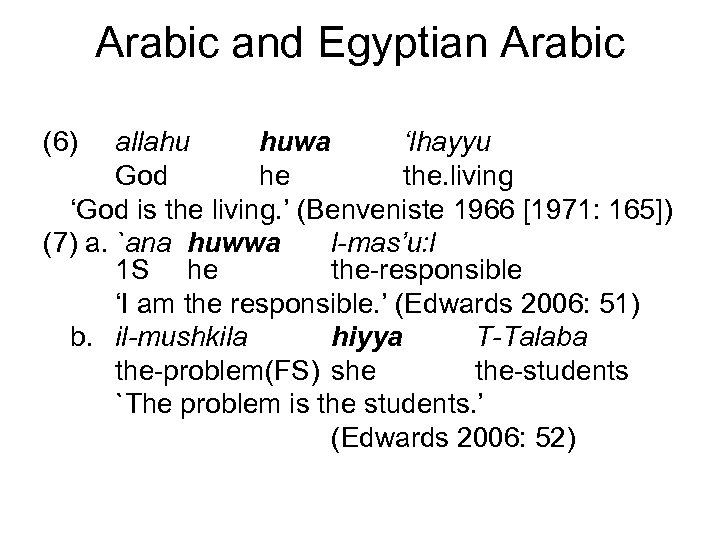

Arabic and Egyptian Arabic (6) allahu huwa ‘lhayyu God he the. living ‘God is the living. ’ (Benveniste 1966 [1971: 165]) (7) a. `ana huwwa l-mas’u: l 1 S he the-responsible ‘I am the responsible. ’ (Edwards 2006: 51) b. il-mushkila hiyya T-Talaba the-problem(FS) she the-students `The problem is the students. ’ (Edwards 2006: 52)

Arabic and Egyptian Arabic (6) allahu huwa ‘lhayyu God he the. living ‘God is the living. ’ (Benveniste 1966 [1971: 165]) (7) a. `ana huwwa l-mas’u: l 1 S he the-responsible ‘I am the responsible. ’ (Edwards 2006: 51) b. il-mushkila hiyya T-Talaba the-problem(FS) she the-students `The problem is the students. ’ (Edwards 2006: 52)

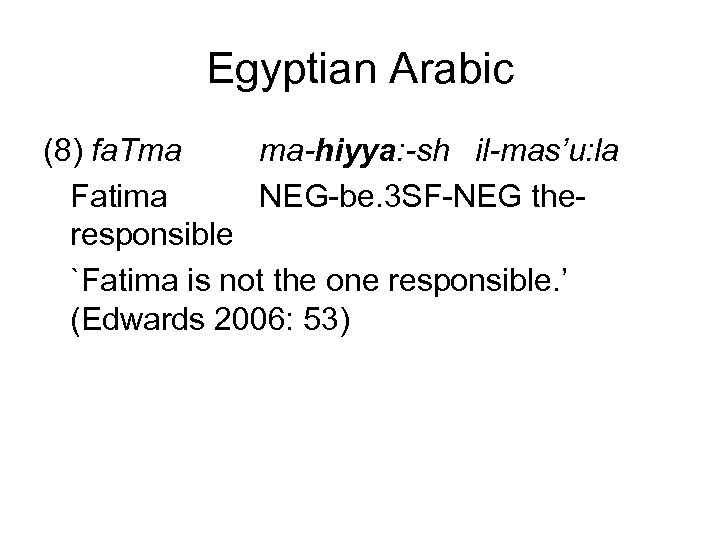

Egyptian Arabic (8) fa. Tma ma-hiyya: -sh il-mas’u: la Fatima NEG-be. 3 SF-NEG theresponsible `Fatima is not the one responsible. ’ (Edwards 2006: 53)

Egyptian Arabic (8) fa. Tma ma-hiyya: -sh il-mas’u: la Fatima NEG-be. 3 SF-NEG theresponsible `Fatima is not the one responsible. ’ (Edwards 2006: 53)

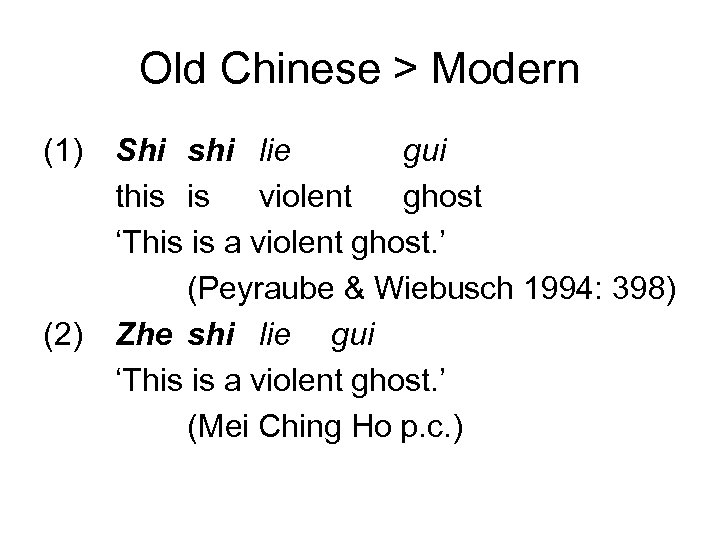

Old Chinese > Modern (1) (2) Shi shi lie gui this is violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 398) Zhe shi lie gui ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Mei Ching Ho p. c. )

Old Chinese > Modern (1) (2) Shi shi lie gui this is violent ghost ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Peyraube & Wiebusch 1994: 398) Zhe shi lie gui ‘This is a violent ghost. ’ (Mei Ching Ho p. c. )

![equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai](https://present5.com/presentation/8fe2e573d7a7966aa61897f9a3d9ced4/image-24.jpg) equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai semantic [place] V shi [identity] V zai [location]

equation and location D > shi semantic [proximate] formal [i-3 S] P > zai semantic [place] V shi [identity] V zai [location]

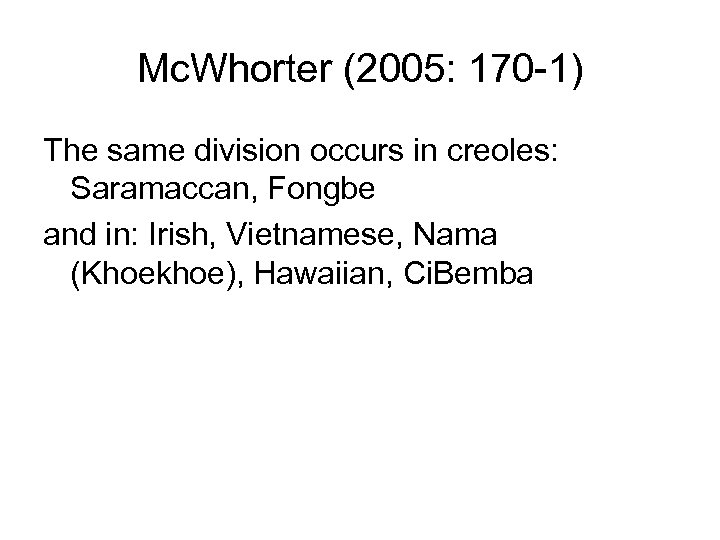

Mc. Whorter (2005: 170 -1) The same division occurs in creoles: Saramaccan, Fongbe and in: Irish, Vietnamese, Nama (Khoekhoe), Hawaiian, Ci. Bemba

Mc. Whorter (2005: 170 -1) The same division occurs in creoles: Saramaccan, Fongbe and in: Irish, Vietnamese, Nama (Khoekhoe), Hawaiian, Ci. Bemba

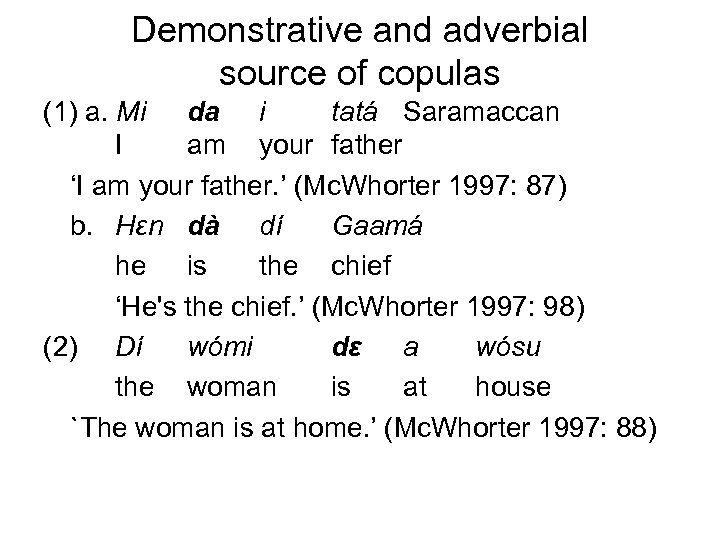

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

Demonstrative and adverbial source of copulas (1) a. Mi da i tatá Saramaccan I am your father ‘I am your father. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 87) b. Hεn dà dí Gaamá he is the chief ‘He's the chief. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 98) (2) Dí wómi dε a wósu the woman is at house `The woman is at home. ’ (Mc. Whorter 1997: 88)

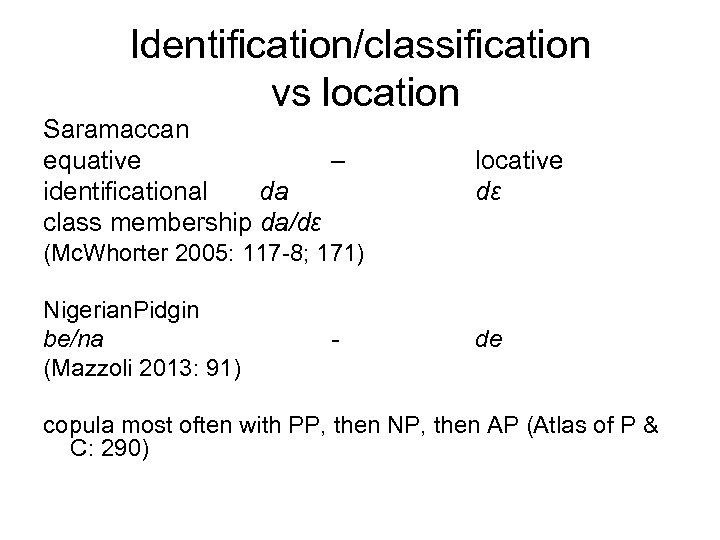

Identification/classification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013: 91) - de copula most often with PP, then NP, then AP (Atlas of P & C: 290)

Identification/classification vs location Saramaccan equative – identificational da class membership da/dɛ locative dɛ (Mc. Whorter 2005: 117 -8; 171) Nigerian. Pidgin be/na (Mazzoli 2013: 91) - de copula most often with PP, then NP, then AP (Atlas of P & C: 290)

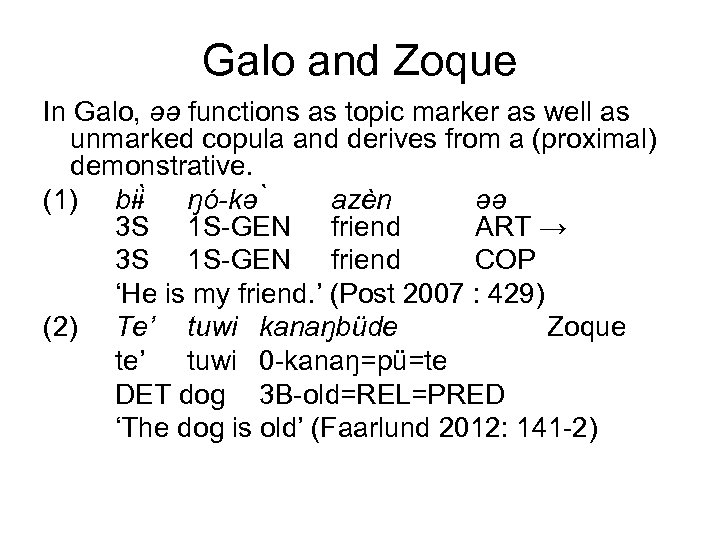

Galo and Zoque In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative. (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007 : 429) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde Zoque te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’ (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2)

Galo and Zoque In Galo, əə functions as topic marker as well as unmarked copula and derives from a (proximal) demonstrative. (1) bɨɨ ŋó-kə azèn əə 3 S 1 S-GEN friend ART → 3 S 1 S-GEN friend COP ‘He is my friend. ’ (Post 2007 : 429) (2) Te’ tuwi kanaŋbüde Zoque te’ tuwi 0 -kanaŋ=pü=te DET dog 3 B-old=REL=PRED ‘The dog is old’ (Faarlund 2012: 141 -2)

![Structurally (see HO): TP T’ T [u-phi] DP DP D that [i-3 S] Structurally (see HO): TP T’ T [u-phi] DP DP D that [i-3 S]](https://present5.com/presentation/8fe2e573d7a7966aa61897f9a3d9ced4/image-29.jpg) Structurally (see HO): TP T’ T [u-phi] DP DP D that [i-3 S]

Structurally (see HO): TP T’ T [u-phi] DP DP D that [i-3 S]

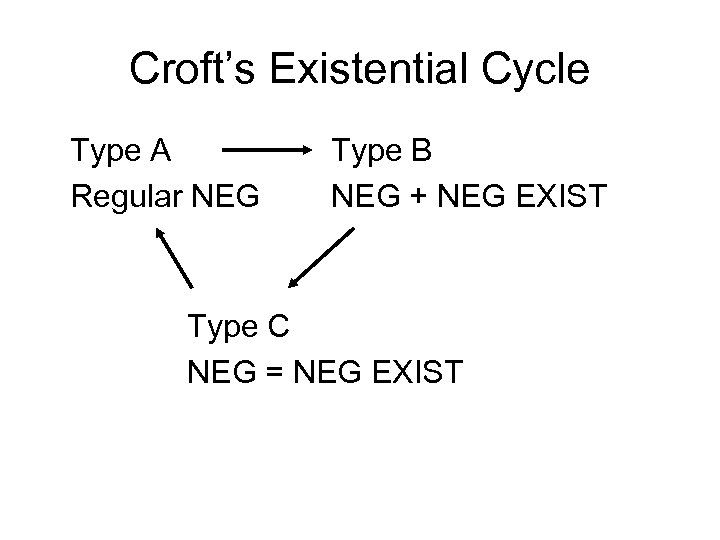

Croft’s Existential Cycle Type A Regular NEG Type B NEG + NEG EXIST Type C NEG = NEG EXIST

Croft’s Existential Cycle Type A Regular NEG Type B NEG + NEG EXIST Type C NEG = NEG EXIST

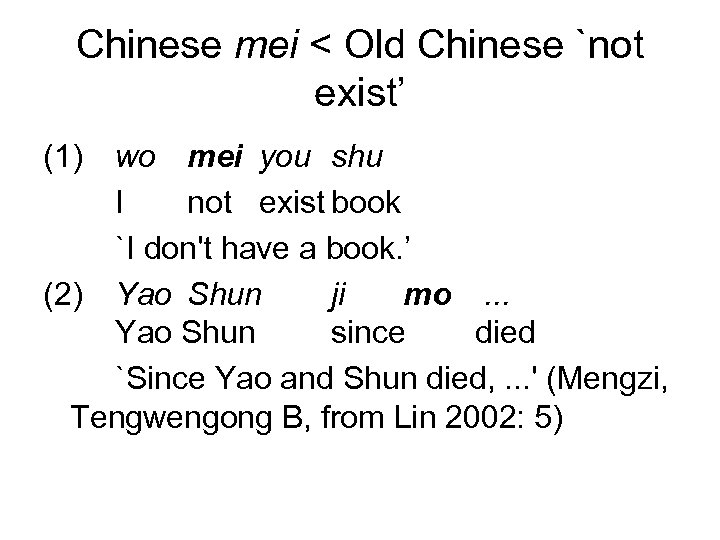

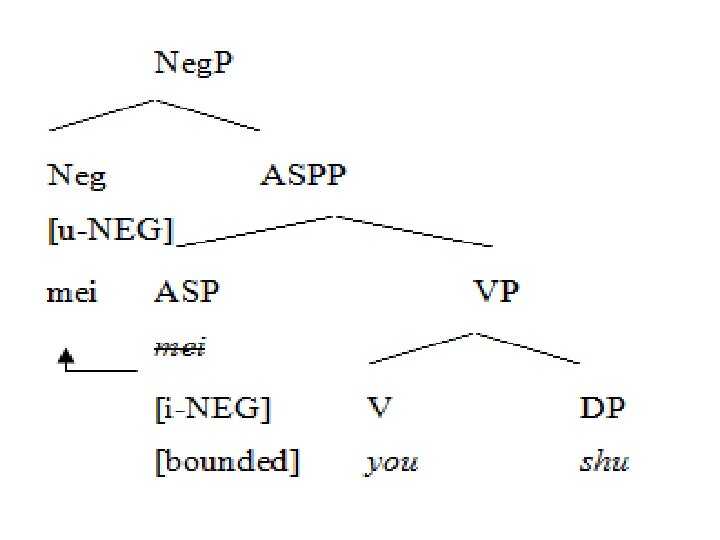

Chinese mei < Old Chinese `not exist’ (1) wo mei you shu I not exist book `I don't have a book. ’ (2) Yao Shun ji mo. . . Yao Shun since died `Since Yao and Shun died, . . . ' (Mengzi, Tengwengong B, from Lin 2002: 5)

Chinese mei < Old Chinese `not exist’ (1) wo mei you shu I not exist book `I don't have a book. ’ (2) Yao Shun ji mo. . . Yao Shun since died `Since Yao and Shun died, . . . ' (Mengzi, Tengwengong B, from Lin 2002: 5)

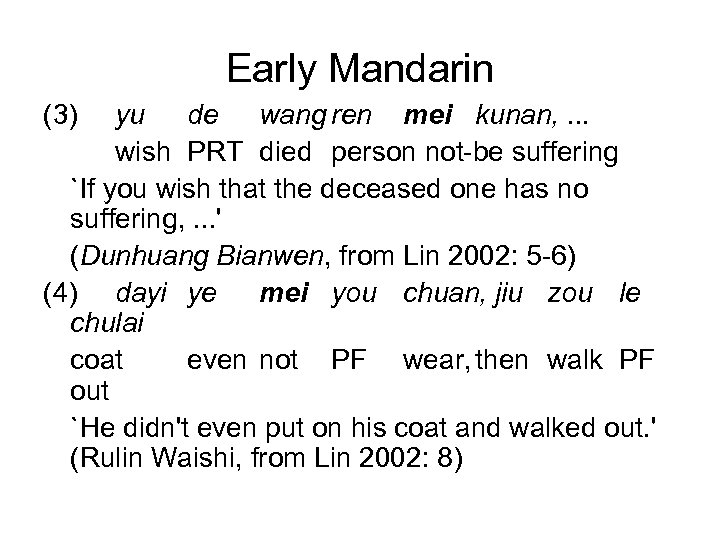

Early Mandarin (3) yu de wang ren mei kunan, . . . wish PRT died person not-be suffering `If you wish that the deceased one has no suffering, . . . ' (Dunhuang Bianwen, from Lin 2002: 5 -6) (4) dayi ye mei you chuan, jiu zou le chulai coat even not PF wear, then walk PF out `He didn't even put on his coat and walked out. ' (Rulin Waishi, from Lin 2002: 8)

Early Mandarin (3) yu de wang ren mei kunan, . . . wish PRT died person not-be suffering `If you wish that the deceased one has no suffering, . . . ' (Dunhuang Bianwen, from Lin 2002: 5 -6) (4) dayi ye mei you chuan, jiu zou le chulai coat even not PF wear, then walk PF out `He didn't even put on his coat and walked out. ' (Rulin Waishi, from Lin 2002: 8)

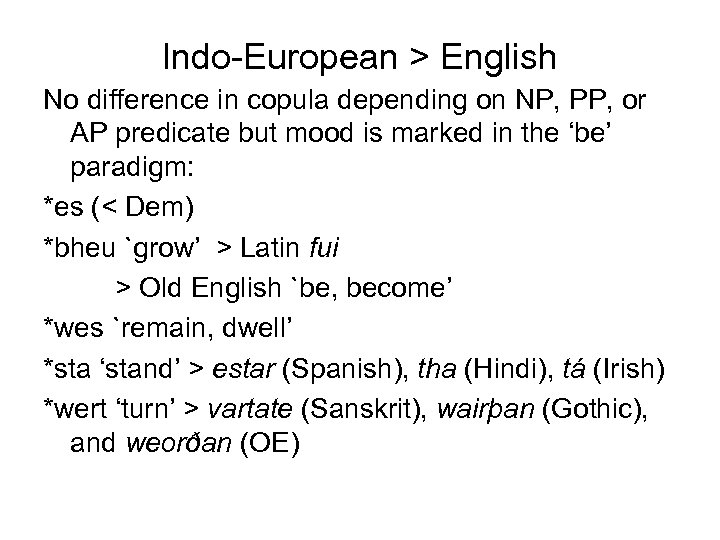

Indo-European > English No difference in copula depending on NP, PP, or AP predicate but mood is marked in the ‘be’ paradigm: *es (< Dem) *bheu `grow’ > Latin fui > Old English `be, become’ *wes `remain, dwell’ *sta ‘stand’ > estar (Spanish), tha (Hindi), tá (Irish) *wert ‘turn’ > vartate (Sanskrit), wairþan (Gothic), and weorðan (OE)

Indo-European > English No difference in copula depending on NP, PP, or AP predicate but mood is marked in the ‘be’ paradigm: *es (< Dem) *bheu `grow’ > Latin fui > Old English `be, become’ *wes `remain, dwell’ *sta ‘stand’ > estar (Spanish), tha (Hindi), tá (Irish) *wert ‘turn’ > vartate (Sanskrit), wairþan (Gothic), and weorðan (OE)

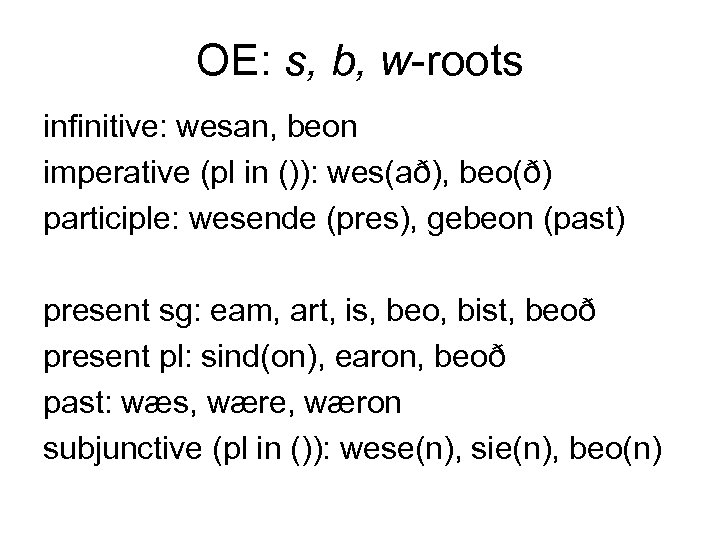

OE: s, b, w-roots infinitive: wesan, beon imperative (pl in ()): wes(að), beo(ð) participle: wesende (pres), gebeon (past) present sg: eam, art, is, beo, bist, beoð present pl: sind(on), earon, beoð past: wæs, wære, wæron subjunctive (pl in ()): wese(n), sie(n), beo(n)

OE: s, b, w-roots infinitive: wesan, beon imperative (pl in ()): wes(að), beo(ð) participle: wesende (pres), gebeon (past) present sg: eam, art, is, beo, bist, beoð present pl: sind(on), earon, beoð past: wæs, wære, wæron subjunctive (pl in ()): wese(n), sie(n), beo(n)

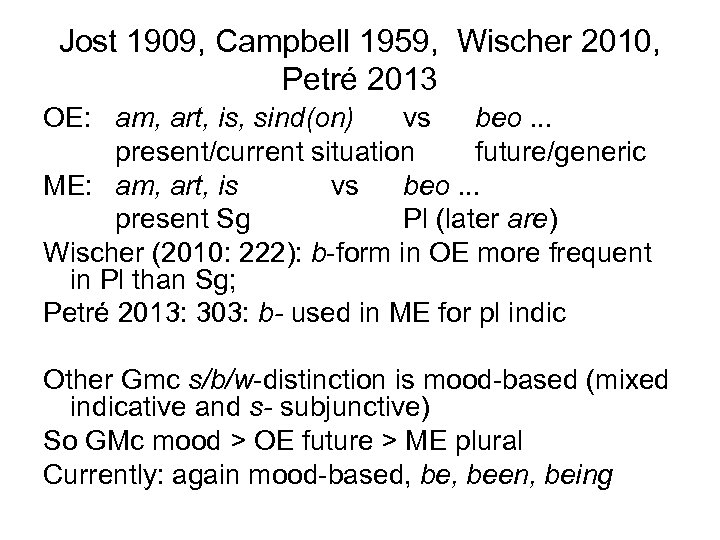

Jost 1909, Campbell 1959, Wischer 2010, Petré 2013 OE: am, art, is, sind(on) vs beo. . . present/current situation future/generic ME: am, art, is vs beo. . . present Sg Pl (later are) Wischer (2010: 222): b-form in OE more frequent in Pl than Sg; Petré 2013: 303: b- used in ME for pl indic Other Gmc s/b/w-distinction is mood-based (mixed indicative and s- subjunctive) So GMc mood > OE future > ME plural Currently: again mood-based, been, being

Jost 1909, Campbell 1959, Wischer 2010, Petré 2013 OE: am, art, is, sind(on) vs beo. . . present/current situation future/generic ME: am, art, is vs beo. . . present Sg Pl (later are) Wischer (2010: 222): b-form in OE more frequent in Pl than Sg; Petré 2013: 303: b- used in ME for pl indic Other Gmc s/b/w-distinction is mood-based (mixed indicative and s- subjunctive) So GMc mood > OE future > ME plural Currently: again mood-based, been, being

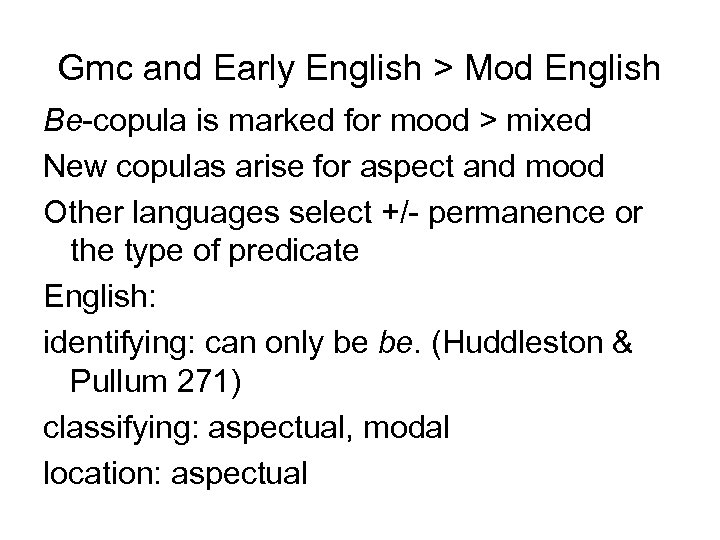

Gmc and Early English > Mod English Be-copula is marked for mood > mixed New copulas arise for aspect and mood Other languages select +/- permanence or the type of predicate English: identifying: can only be be. (Huddleston & Pullum 271) classifying: aspectual, modal location: aspectual

Gmc and Early English > Mod English Be-copula is marked for mood > mixed New copulas arise for aspect and mood Other languages select +/- permanence or the type of predicate English: identifying: can only be be. (Huddleston & Pullum 271) classifying: aspectual, modal location: aspectual

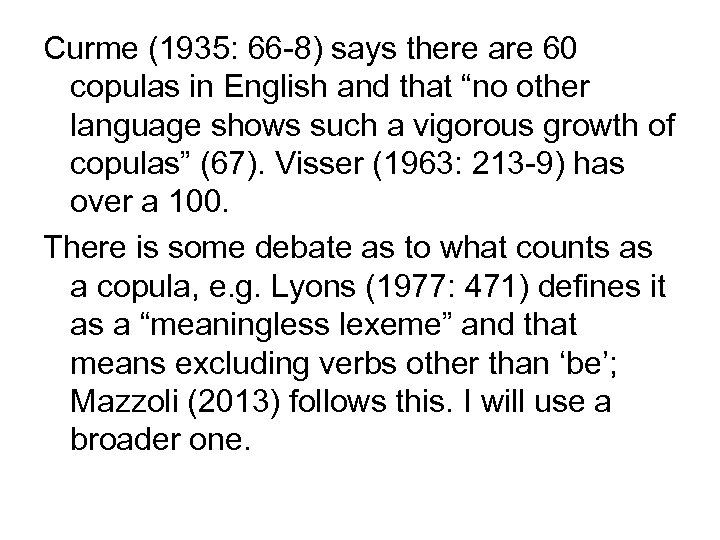

Curme (1935: 66 -8) says there are 60 copulas in English and that “no other language shows such a vigorous growth of copulas” (67). Visser (1963: 213 -9) has over a 100. There is some debate as to what counts as a copula, e. g. Lyons (1977: 471) defines it as a “meaningless lexeme” and that means excluding verbs other than ‘be’; Mazzoli (2013) follows this. I will use a broader one.

Curme (1935: 66 -8) says there are 60 copulas in English and that “no other language shows such a vigorous growth of copulas” (67). Visser (1963: 213 -9) has over a 100. There is some debate as to what counts as a copula, e. g. Lyons (1977: 471) defines it as a “meaningless lexeme” and that means excluding verbs other than ‘be’; Mazzoli (2013) follows this. I will use a broader one.

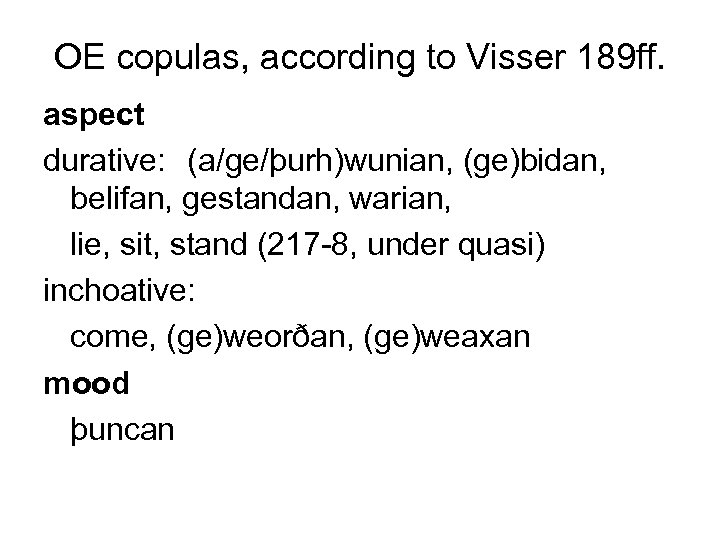

OE copulas, according to Visser 189 ff. aspect durative: (a/ge/þurh)wunian, (ge)bidan, belifan, gestandan, warian, lie, sit, stand (217 -8, under quasi) inchoative: come, (ge)weorðan, (ge)weaxan mood þuncan

OE copulas, according to Visser 189 ff. aspect durative: (a/ge/þurh)wunian, (ge)bidan, belifan, gestandan, warian, lie, sit, stand (217 -8, under quasi) inchoative: come, (ge)weorðan, (ge)weaxan mood þuncan

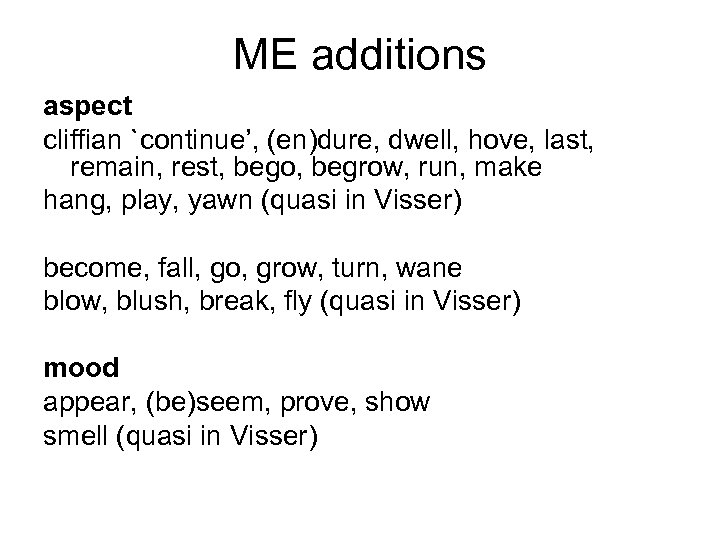

ME additions aspect cliffian `continue’, (en)dure, dwell, hove, last, remain, rest, bego, begrow, run, make hang, play, yawn (quasi in Visser) become, fall, go, grow, turn, wane blow, blush, break, fly (quasi in Visser) mood appear, (be)seem, prove, show smell (quasi in Visser)

ME additions aspect cliffian `continue’, (en)dure, dwell, hove, last, remain, rest, bego, begrow, run, make hang, play, yawn (quasi in Visser) become, fall, go, grow, turn, wane blow, blush, break, fly (quasi in Visser) mood appear, (be)seem, prove, show smell (quasi in Visser)

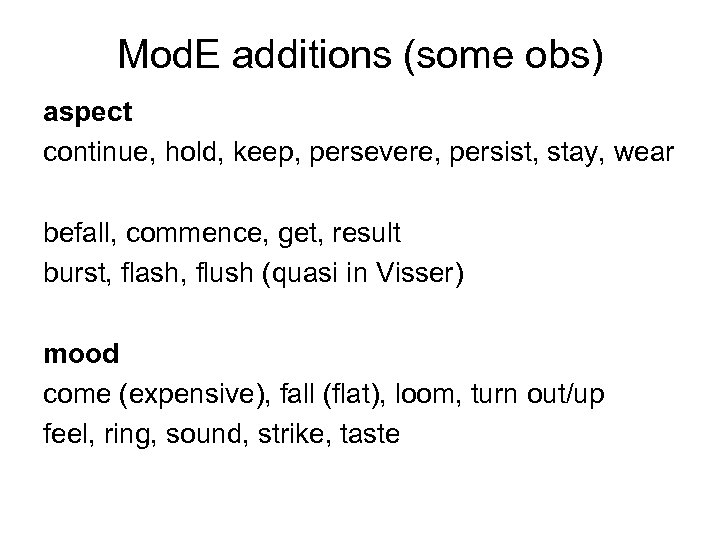

Mod. E additions (some obs) aspect continue, hold, keep, persevere, persist, stay, wear befall, commence, get, result burst, flash, flush (quasi in Visser) mood come (expensive), fall (flat), loom, turn out/up feel, ring, sound, strike, taste

Mod. E additions (some obs) aspect continue, hold, keep, persevere, persist, stay, wear befall, commence, get, result burst, flash, flush (quasi in Visser) mood come (expensive), fall (flat), loom, turn out/up feel, ring, sound, strike, taste

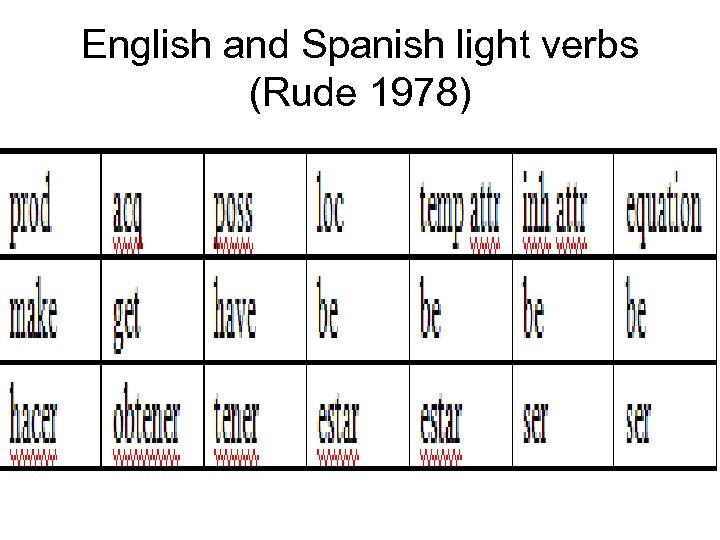

English and Spanish light verbs (Rude 1978)

English and Spanish light verbs (Rude 1978)

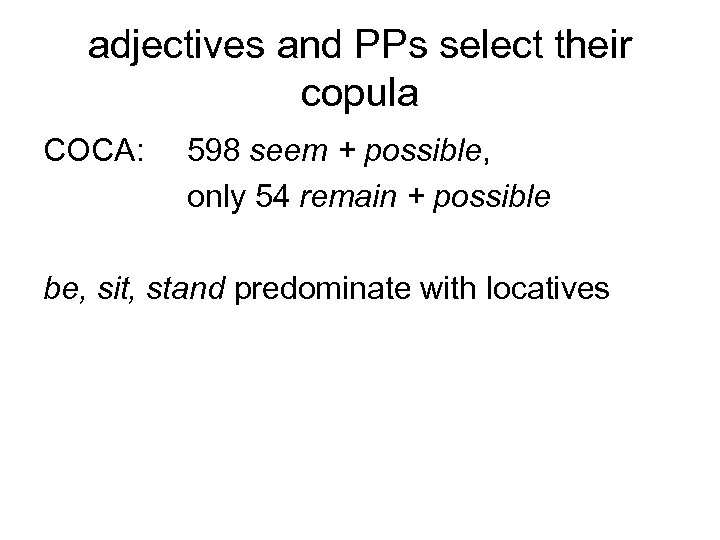

adjectives and PPs select their copula COCA: 598 seem + possible, only 54 remain + possible be, sit, stand predominate with locatives

adjectives and PPs select their copula COCA: 598 seem + possible, only 54 remain + possible be, sit, stand predominate with locatives

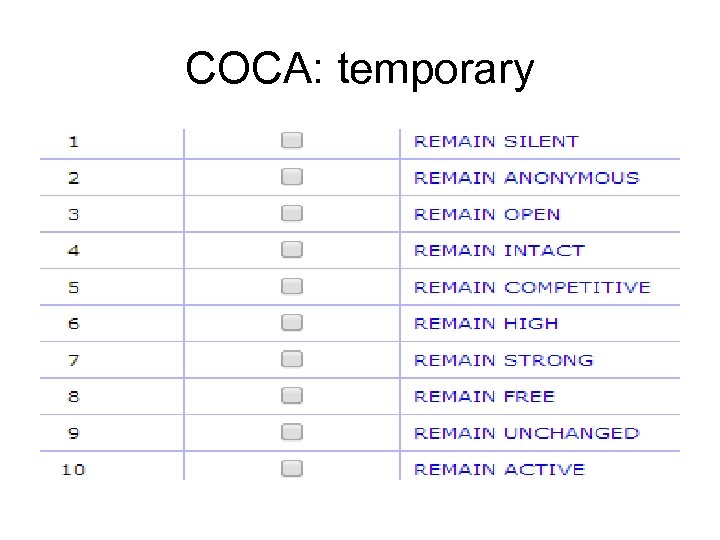

COCA: temporary

COCA: temporary

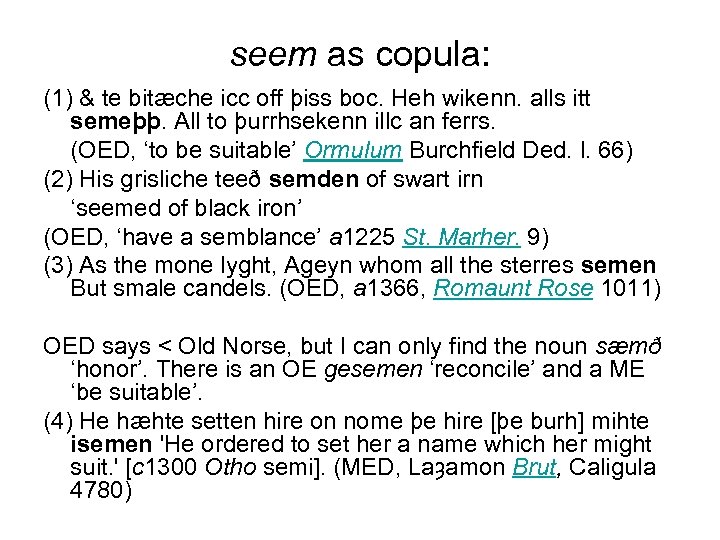

seem as copula: (1) & te bitæche icc off þiss boc. Heh wikenn. alls itt semeþþ. All to þurrhsekenn illc an ferrs. (OED, ‘to be suitable’ Ormulum Burchfield Ded. l. 66) (2) His grisliche teeð semden of swart irn ‘seemed of black iron’ (OED, ‘have a semblance’ a 1225 St. Marher. 9) (3) As the mone lyght, Ageyn whom all the sterres semen But smale candels. (OED, a 1366, Romaunt Rose 1011) OED says < Old Norse, but I can only find the noun sæmð ‘honor’. There is an OE gesemen ‘reconcile’ and a ME ‘be suitable’. (4) He hæhte setten hire on nome þe hire [þe burh] mihte isemen 'He ordered to set her a name which her might suit. ' [c 1300 Otho semi]. (MED, Laȝamon Brut, Caligula 4780)

seem as copula: (1) & te bitæche icc off þiss boc. Heh wikenn. alls itt semeþþ. All to þurrhsekenn illc an ferrs. (OED, ‘to be suitable’ Ormulum Burchfield Ded. l. 66) (2) His grisliche teeð semden of swart irn ‘seemed of black iron’ (OED, ‘have a semblance’ a 1225 St. Marher. 9) (3) As the mone lyght, Ageyn whom all the sterres semen But smale candels. (OED, a 1366, Romaunt Rose 1011) OED says < Old Norse, but I can only find the noun sæmð ‘honor’. There is an OE gesemen ‘reconcile’ and a ME ‘be suitable’. (4) He hæhte setten hire on nome þe hire [þe burh] mihte isemen 'He ordered to set her a name which her might suit. ' [c 1300 Otho semi]. (MED, Laȝamon Brut, Caligula 4780)

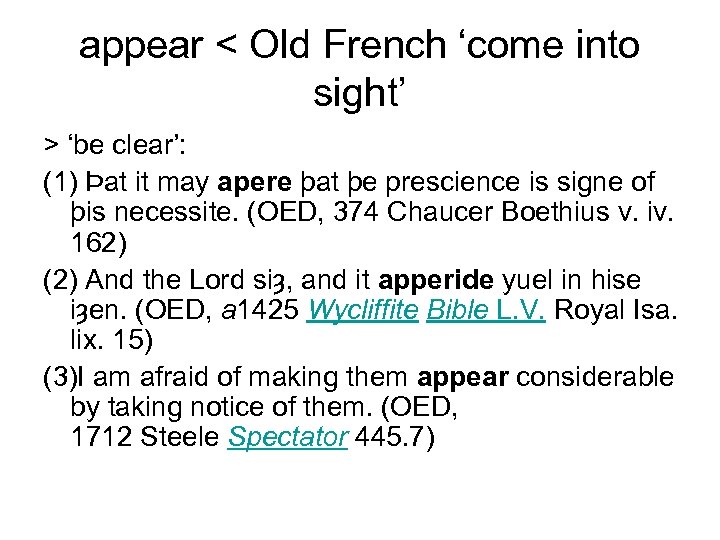

appear < Old French ‘come into sight’ > ‘be clear’: (1) Þat it may apere þat þe prescience is signe of þis necessite. (OED, 374 Chaucer Boethius v. iv. 162) (2) And the Lord siȝ, and it apperide yuel in hise iȝen. (OED, a 1425 Wycliffite Bible L. V. Royal Isa. lix. 15) (3)I am afraid of making them appear considerable by taking notice of them. (OED, 1712 Steele Spectator 445. 7)

appear < Old French ‘come into sight’ > ‘be clear’: (1) Þat it may apere þat þe prescience is signe of þis necessite. (OED, 374 Chaucer Boethius v. iv. 162) (2) And the Lord siȝ, and it apperide yuel in hise iȝen. (OED, a 1425 Wycliffite Bible L. V. Royal Isa. lix. 15) (3)I am afraid of making them appear considerable by taking notice of them. (OED, 1712 Steele Spectator 445. 7)

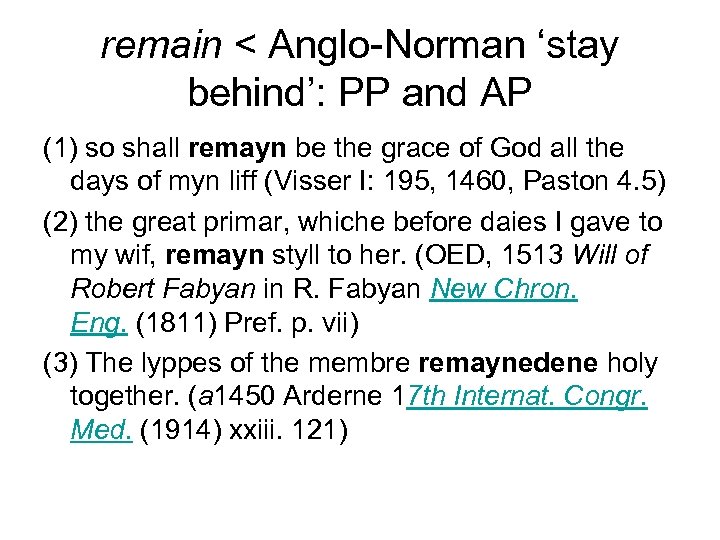

remain < Anglo-Norman ‘stay behind’: PP and AP (1) so shall remayn be the grace of God all the days of myn liff (Visser I: 195, 1460, Paston 4. 5) (2) the great primar, whiche before daies I gave to my wif, remayn styll to her. (OED, 1513 Will of Robert Fabyan in R. Fabyan New Chron. Eng. (1811) Pref. p. vii) (3) The lyppes of the membre remaynedene holy together. (a 1450 Arderne 17 th Internat. Congr. Med. (1914) xxiii. 121)

remain < Anglo-Norman ‘stay behind’: PP and AP (1) so shall remayn be the grace of God all the days of myn liff (Visser I: 195, 1460, Paston 4. 5) (2) the great primar, whiche before daies I gave to my wif, remayn styll to her. (OED, 1513 Will of Robert Fabyan in R. Fabyan New Chron. Eng. (1811) Pref. p. vii) (3) The lyppes of the membre remaynedene holy together. (a 1450 Arderne 17 th Internat. Congr. Med. (1914) xxiii. 121)

![PP V to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar PP V to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar](https://present5.com/presentation/8fe2e573d7a7966aa61897f9a3d9ced4/image-48.jpg) PP V to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar to her [location] [i-3 S] [duration] [Th] [u. Th]

PP V to her remayn V DP [loc] DP PP remayn primar [dur] primar to her [location] [i-3 S] [duration] [Th] [u. Th]

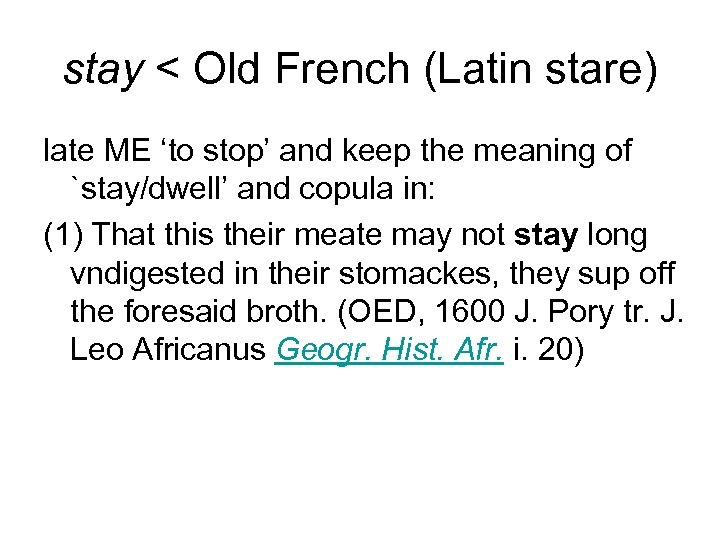

stay < Old French (Latin stare) late ME ‘to stop’ and keep the meaning of `stay/dwell’ and copula in: (1) That this their meate may not stay long vndigested in their stomackes, they sup off the foresaid broth. (OED, 1600 J. Pory tr. J. Leo Africanus Geogr. Hist. Afr. i. 20)

stay < Old French (Latin stare) late ME ‘to stop’ and keep the meaning of `stay/dwell’ and copula in: (1) That this their meate may not stay long vndigested in their stomackes, they sup off the foresaid broth. (OED, 1600 J. Pory tr. J. Leo Africanus Geogr. Hist. Afr. i. 20)

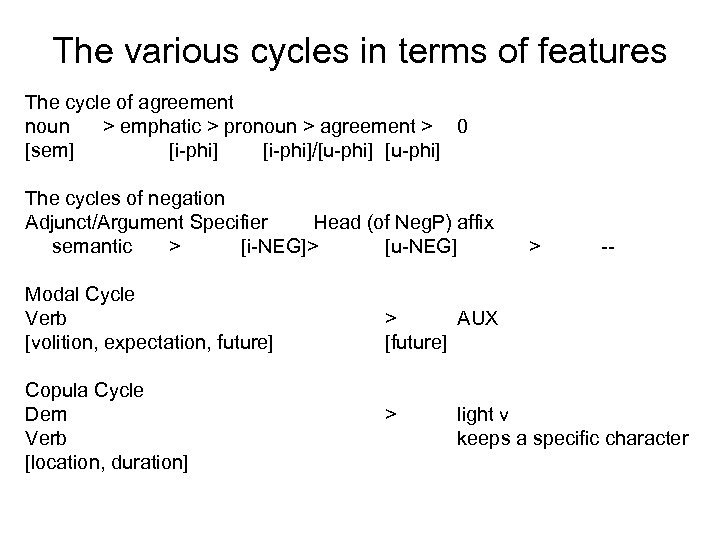

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier Head (of Neg. P) affix semantic > [i-NEG]> [u-NEG] Modal Cycle Verb [volition, expectation, future] Copula Cycle Dem Verb [location, duration] > -- > AUX [future] > light v keeps a specific character

The various cycles in terms of features The cycle of agreement noun > emphatic > pronoun > agreement > 0 [sem] [i-phi]/[u-phi] The cycles of negation Adjunct/Argument Specifier Head (of Neg. P) affix semantic > [i-NEG]> [u-NEG] Modal Cycle Verb [volition, expectation, future] Copula Cycle Dem Verb [location, duration] > -- > AUX [future] > light v keeps a specific character

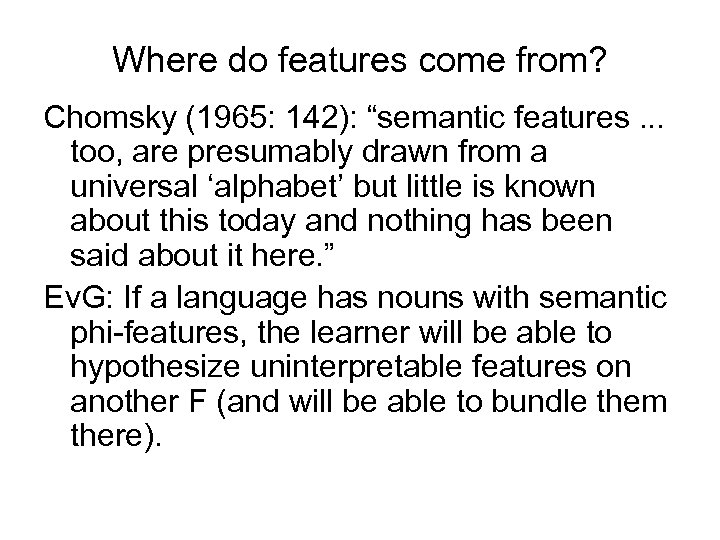

Where do features come from? Chomsky (1965: 142): “semantic features. . . too, are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’ but little is known about this today and nothing has been said about it here. ” Ev. G: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

Where do features come from? Chomsky (1965: 142): “semantic features. . . too, are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’ but little is known about this today and nothing has been said about it here. ” Ev. G: If a language has nouns with semantic phi-features, the learner will be able to hypothesize uninterpretable features on another F (and will be able to bundle them there).

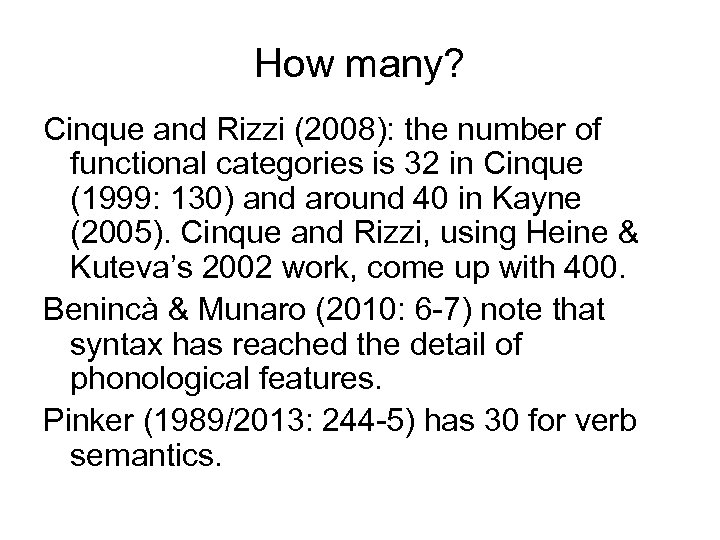

How many? Cinque and Rizzi (2008): the number of functional categories is 32 in Cinque (1999: 130) and around 40 in Kayne (2005). Cinque and Rizzi, using Heine & Kuteva’s 2002 work, come up with 400. Benincà & Munaro (2010: 6 -7) note that syntax has reached the detail of phonological features. Pinker (1989/2013: 244 -5) has 30 for verb semantics.

How many? Cinque and Rizzi (2008): the number of functional categories is 32 in Cinque (1999: 130) and around 40 in Kayne (2005). Cinque and Rizzi, using Heine & Kuteva’s 2002 work, come up with 400. Benincà & Munaro (2010: 6 -7) note that syntax has reached the detail of phonological features. Pinker (1989/2013: 244 -5) has 30 for verb semantics.

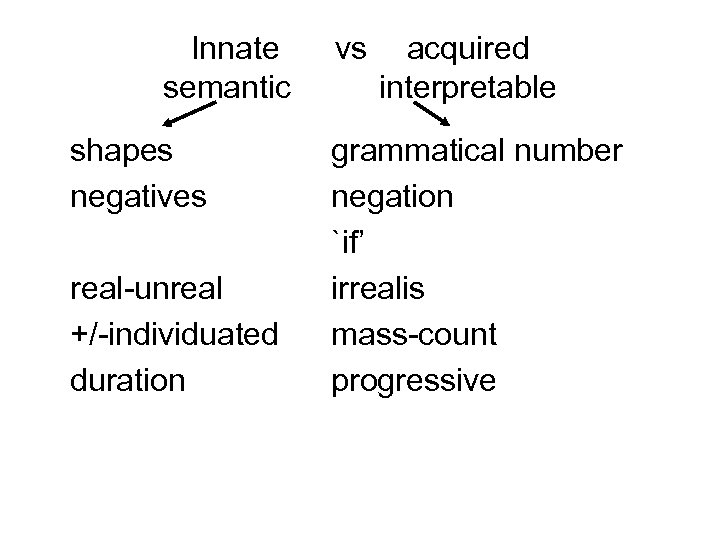

Innate semantic shapes negatives real-unreal +/-individuated duration vs acquired interpretable grammatical number negation `if’ irrealis mass-count progressive

Innate semantic shapes negatives real-unreal +/-individuated duration vs acquired interpretable grammatical number negation `if’ irrealis mass-count progressive

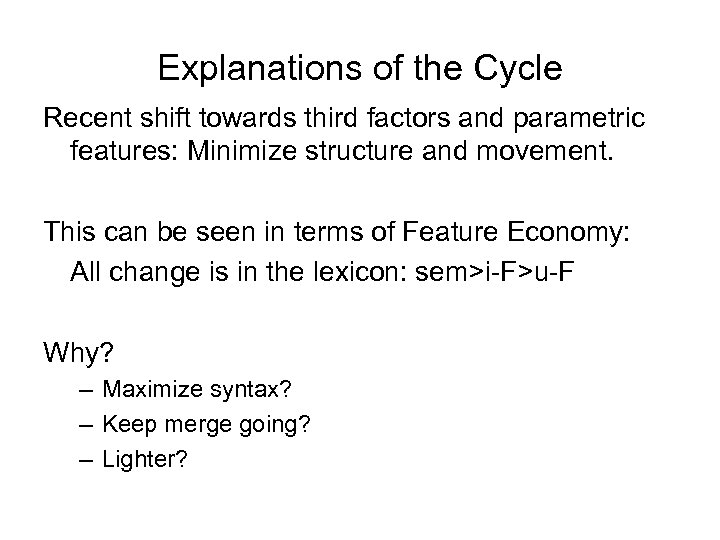

Explanations of the Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: Minimize structure and movement. This can be seen in terms of Feature Economy: All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Why? – Maximize syntax? – Keep merge going? – Lighter?

Explanations of the Cycle Recent shift towards third factors and parametric features: Minimize structure and movement. This can be seen in terms of Feature Economy: All change is in the lexicon: sem>i-F>u-F Why? – Maximize syntax? – Keep merge going? – Lighter?

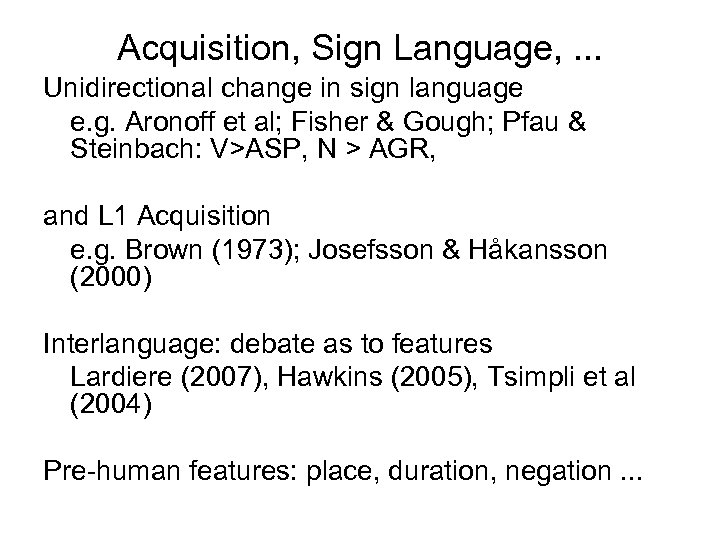

Acquisition, Sign Language, . . . Unidirectional change in sign language e. g. Aronoff et al; Fisher & Gough; Pfau & Steinbach: V>ASP, N > AGR, and L 1 Acquisition e. g. Brown (1973); Josefsson & Håkansson (2000) Interlanguage: debate as to features Lardiere (2007), Hawkins (2005), Tsimpli et al (2004) Pre-human features: place, duration, negation. . .

Acquisition, Sign Language, . . . Unidirectional change in sign language e. g. Aronoff et al; Fisher & Gough; Pfau & Steinbach: V>ASP, N > AGR, and L 1 Acquisition e. g. Brown (1973); Josefsson & Håkansson (2000) Interlanguage: debate as to features Lardiere (2007), Hawkins (2005), Tsimpli et al (2004) Pre-human features: place, duration, negation. . .

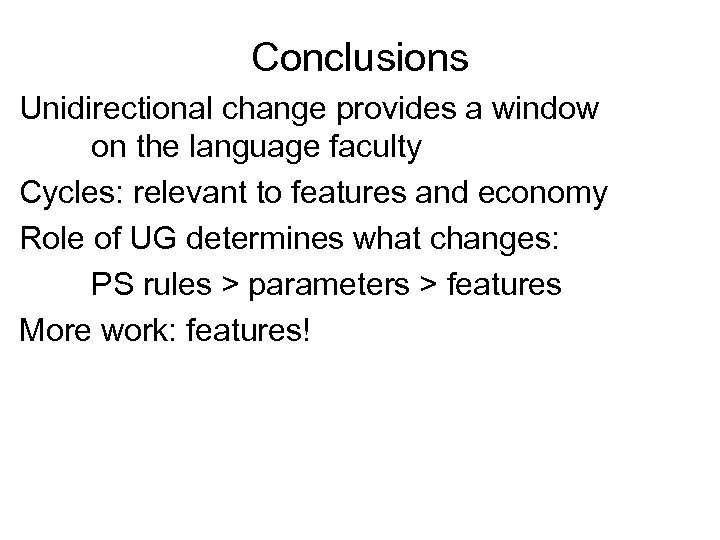

Conclusions Unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty Cycles: relevant to features and economy Role of UG determines what changes: PS rules > parameters > features More work: features!

Conclusions Unidirectional change provides a window on the language faculty Cycles: relevant to features and economy Role of UG determines what changes: PS rules > parameters > features More work: features!

References Benveniste, Emile 1960. The linguistic functions of to be and to have. In Problems in General Linguistics. Biese, Y. 1952. Notes on the use of the ingressive auxiliary in the Works of William Shakespeare. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 53: 918. Chvany, Catherine 1995. The paradigm as partitioned grammatical space. In The Language and Verse of Russia. . . Curme, George 1935. Faarlund, Jan Terje 2012. A Grammar of Chiapas Zoque. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences: 13: 17. Katz, Aya 1996. Cyclical Grammaticalization and the Cognitive Link between Pronoun and Copula. Rice Dissertation. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford University Press.

References Benveniste, Emile 1960. The linguistic functions of to be and to have. In Problems in General Linguistics. Biese, Y. 1952. Notes on the use of the ingressive auxiliary in the Works of William Shakespeare. Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 53: 918. Chvany, Catherine 1995. The paradigm as partitioned grammatical space. In The Language and Verse of Russia. . . Curme, George 1935. Faarlund, Jan Terje 2012. A Grammar of Chiapas Zoque. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hodge, Carleton 1970. The Linguistic Cycle. Linguistic Sciences: 13: 17. Katz, Aya 1996. Cyclical Grammaticalization and the Cognitive Link between Pronoun and Copula. Rice Dissertation. Gelderen, Elly van 2011. The Linguistic Cycle. Oxford University Press.

Lyons, John 1977. Semantics II. CUP. Mazzoli, Maria 2013. Copulas in Nigerian Pidgin. Padova dissertation. Mc. Whorter, John 2005. Defining Creole. OUP. Petré, Peter 2010. On the interaction between constructional and lexical change. Leuven dissertation. Post, Mark 2007. A Grammar of Galo. La Trobe Dissertation. Pustet, Regina. 2003. Copulas: Universals in the Categorization of the Lexicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rude, Noel 1978. A Continuum of Meaning in the Copula. Proceedings of the 4 th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 202 -210. Stassen, Leon 1997. Intransitive Predication. OUP.

Lyons, John 1977. Semantics II. CUP. Mazzoli, Maria 2013. Copulas in Nigerian Pidgin. Padova dissertation. Mc. Whorter, John 2005. Defining Creole. OUP. Petré, Peter 2010. On the interaction between constructional and lexical change. Leuven dissertation. Post, Mark 2007. A Grammar of Galo. La Trobe Dissertation. Pustet, Regina. 2003. Copulas: Universals in the Categorization of the Lexicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rude, Noel 1978. A Continuum of Meaning in the Copula. Proceedings of the 4 th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 202 -210. Stassen, Leon 1997. Intransitive Predication. OUP.