8ae031b10936d66dfb46f486dc52e878.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 30

The Canadian Immigration System: Policy and Patterns The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

The Canadian Immigration System: Policy and Patterns The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

MAJOR HISTORICAL TRENDS 1. Economic Shift from an “Agricultural” to a “Post. Industrial” base. 2. Policy Shift from a “Closed Policy” to “Open Policy” to “Restricted Policy” 3. Administrative Shift from “Absorptive Capacity” To “Adaptive Capacity. ” 4. Demographic Shift to more “Complex Social Differentiations” in Society. 5. Cognitive Shift from a “White-Settler Colony” to a “Post -Racial Society. ” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

MAJOR HISTORICAL TRENDS 1. Economic Shift from an “Agricultural” to a “Post. Industrial” base. 2. Policy Shift from a “Closed Policy” to “Open Policy” to “Restricted Policy” 3. Administrative Shift from “Absorptive Capacity” To “Adaptive Capacity. ” 4. Demographic Shift to more “Complex Social Differentiations” in Society. 5. Cognitive Shift from a “White-Settler Colony” to a “Post -Racial Society. ” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Outline of Presentation: The Canadian Immigration System n n n History of Canada’s Immigration Policy – Forms and Periods Immigration in Canada Today: A General Picture • Immigration levels • Regions of origin • Types of immigrants • Where immigrants settle Policy Challenge: Immigrant’s skills and credentials are not utilized – The Foreign Credentials Gap The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Outline of Presentation: The Canadian Immigration System n n n History of Canada’s Immigration Policy – Forms and Periods Immigration in Canada Today: A General Picture • Immigration levels • Regions of origin • Types of immigrants • Where immigrants settle Policy Challenge: Immigrant’s skills and credentials are not utilized – The Foreign Credentials Gap The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

History of Immigration Policy: The Three Forms The Forms of Immigration: From a White-Settler Colony to a Post-Racial Society & From an Agricultural to a Post-industrial Society “Closed Policy" – [designated country immigrants] of ‘preferred’ European stock, White-Settler Colony mentality. “Open Policy" – [mapped by a ‘point system’ immigrants], supporting the rise of a Post-Racial Society mentality. “Restrictive Policy“ – [labour market matrix immigrants] characterized by the rise of “Designer immigration. ” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

History of Immigration Policy: The Three Forms The Forms of Immigration: From a White-Settler Colony to a Post-Racial Society & From an Agricultural to a Post-industrial Society “Closed Policy" – [designated country immigrants] of ‘preferred’ European stock, White-Settler Colony mentality. “Open Policy" – [mapped by a ‘point system’ immigrants], supporting the rise of a Post-Racial Society mentality. “Restrictive Policy“ – [labour market matrix immigrants] characterized by the rise of “Designer immigration. ” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

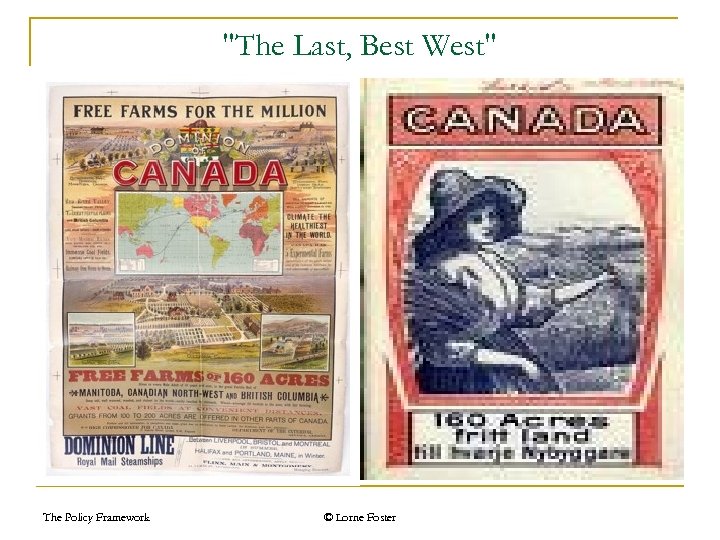

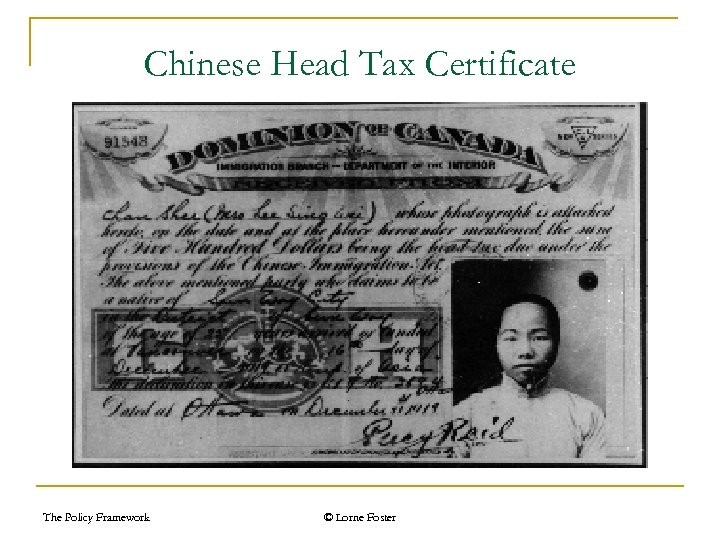

Period One: 1867 – 1913 n Immigration part of a general set of national policies (1868 -1892 Department of Agriculture; 1892 -1917 Department of Interior) n Main goals. securing farmers, farm workers and female domestics. populate, farm and settle the Canadian West. n Search for farmers was concentrated in Britain, the U. S. and Northwestern Europe. n The highest levels ever: 330, 000 in 1911 and 400, 000 in 1913. n Demand for labour high, source countries begin to include Eastern and Central Europe – and give away land to White-settlers. n Head tax on Chinese immigrants in West doubled, to $100 – tax increased again to $500 – then immigration outlawed in 1923. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period One: 1867 – 1913 n Immigration part of a general set of national policies (1868 -1892 Department of Agriculture; 1892 -1917 Department of Interior) n Main goals. securing farmers, farm workers and female domestics. populate, farm and settle the Canadian West. n Search for farmers was concentrated in Britain, the U. S. and Northwestern Europe. n The highest levels ever: 330, 000 in 1911 and 400, 000 in 1913. n Demand for labour high, source countries begin to include Eastern and Central Europe – and give away land to White-settlers. n Head tax on Chinese immigrants in West doubled, to $100 – tax increased again to $500 – then immigration outlawed in 1923. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

History of Canada’s Immigration Policy: The Eight Periods “When I speak of quality, I have in mind something that is quite different from what is in the mind of the average writer or speaker upon the question of immigration. I think of a stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for generations, with a stout wife and half-a-dozen children, is good quality. ” Sir Clifford Sifton, 1922 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

History of Canada’s Immigration Policy: The Eight Periods “When I speak of quality, I have in mind something that is quite different from what is in the mind of the average writer or speaker upon the question of immigration. I think of a stalwart peasant in a sheep-skin coat, born on the soil, whose forefathers have been farmers for generations, with a stout wife and half-a-dozen children, is good quality. ” Sir Clifford Sifton, 1922 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

"The Last, Best West" The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

"The Last, Best West" The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Chinese Head Tax Certificate The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Chinese Head Tax Certificate The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Two: 1919 – 1929 Industrialization and Urbanization n 1919: Immigration Act revised (reflecting growth of classbased cleavage/social stratification) n First official division of source countries into preferred and non-preferred groups n Formal acknowledgement of “short-term absorptive capacity” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Two: 1919 – 1929 Industrialization and Urbanization n 1919: Immigration Act revised (reflecting growth of classbased cleavage/social stratification) n First official division of source countries into preferred and non-preferred groups n Formal acknowledgement of “short-term absorptive capacity” The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Three: 1930 s and 1940 s déjà vu Capitalism n 1931: Canadian unemployment rate over 11% n Financial [déjà vu Capitalism and the ideological distain for market regulation] system crisis comparable to today. n Effectively ended six decades of active immigrant recruitment. n Door closed to most newcomers except those (of European descent) from Britain and the US. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Three: 1930 s and 1940 s déjà vu Capitalism n 1931: Canadian unemployment rate over 11% n Financial [déjà vu Capitalism and the ideological distain for market regulation] system crisis comparable to today. n Effectively ended six decades of active immigrant recruitment. n Door closed to most newcomers except those (of European descent) from Britain and the US. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Four: 1946 – 1962 The Transition to an Advanced Industrial Society n Two main events: large influx of displaced persons from Europe, establishment of clear ethnic and economic goals for immigration policy n 1947: Prime Minister Mackenzie King stated that immigration had purpose of (1) population growth and (2) improved Canadian standard of living. n 1952: New Immigration Act – strict admissions control. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Four: 1946 – 1962 The Transition to an Advanced Industrial Society n Two main events: large influx of displaced persons from Europe, establishment of clear ethnic and economic goals for immigration policy n 1947: Prime Minister Mackenzie King stated that immigration had purpose of (1) population growth and (2) improved Canadian standard of living. n 1952: New Immigration Act – strict admissions control. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

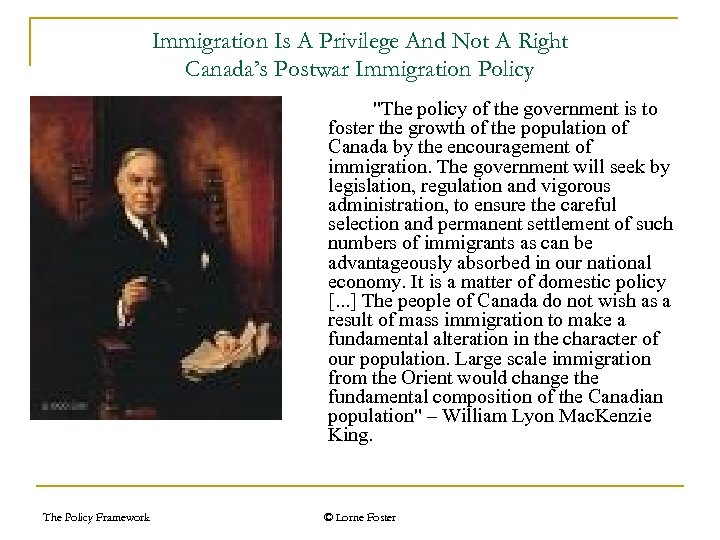

Immigration Is A Privilege And Not A Right Canada’s Postwar Immigration Policy "The policy of the government is to foster the growth of the population of Canada by the encouragement of immigration. The government will seek by legislation, regulation and vigorous administration, to ensure the careful selection and permanent settlement of such numbers of immigrants as can be advantageously absorbed in our national economy. It is a matter of domestic policy [. . . ] The people of Canada do not wish as a result of mass immigration to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population" – William Lyon Mac. Kenzie King. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Immigration Is A Privilege And Not A Right Canada’s Postwar Immigration Policy "The policy of the government is to foster the growth of the population of Canada by the encouragement of immigration. The government will seek by legislation, regulation and vigorous administration, to ensure the careful selection and permanent settlement of such numbers of immigrants as can be advantageously absorbed in our national economy. It is a matter of domestic policy [. . . ] The people of Canada do not wish as a result of mass immigration to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large scale immigration from the Orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population" – William Lyon Mac. Kenzie King. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Five: 1962 – 1973 Liberal Universalism and Difference Blind-ness n 1962: Canada abandoned its all White racist immigration policy. Admission to be based on individual personal characteristics; not nationality n 1966 Immigration under Department of Manpower and Immigration (directly tie immigration and labour market). n 1967: Point system created to facilitate and encourage the flow of skilled migrants n n Family class was still prioritized Additional immigration posts were opened in third world areas; resulting shift in region of immigrant origin The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Five: 1962 – 1973 Liberal Universalism and Difference Blind-ness n 1962: Canada abandoned its all White racist immigration policy. Admission to be based on individual personal characteristics; not nationality n 1966 Immigration under Department of Manpower and Immigration (directly tie immigration and labour market). n 1967: Point system created to facilitate and encourage the flow of skilled migrants n n Family class was still prioritized Additional immigration posts were opened in third world areas; resulting shift in region of immigrant origin The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

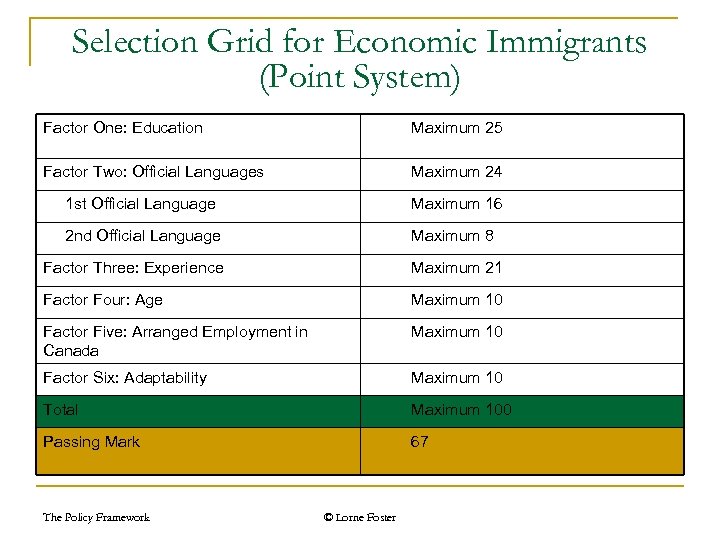

Selection Grid for Economic Immigrants (Point System) Factor One: Education Maximum 25 Factor Two: Official Languages Maximum 24 1 st Official Language Maximum 16 2 nd Official Language Maximum 8 Factor Three: Experience Maximum 21 Factor Four: Age Maximum 10 Factor Five: Arranged Employment in Canada Maximum 10 Factor Six: Adaptability Maximum 10 Total Maximum 100 Passing Mark 67 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Selection Grid for Economic Immigrants (Point System) Factor One: Education Maximum 25 Factor Two: Official Languages Maximum 24 1 st Official Language Maximum 16 2 nd Official Language Maximum 8 Factor Three: Experience Maximum 21 Factor Four: Age Maximum 10 Factor Five: Arranged Employment in Canada Maximum 10 Factor Six: Adaptability Maximum 10 Total Maximum 100 Passing Mark 67 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

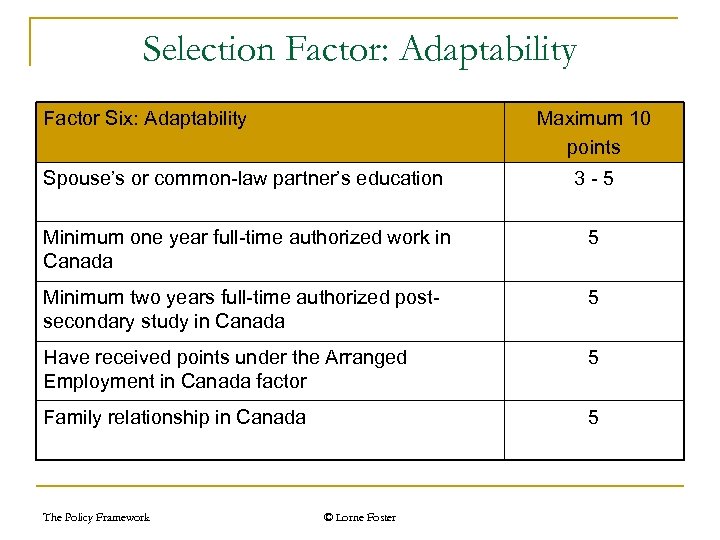

Selection Factor: Adaptability Factor Six: Adaptability Maximum 10 points Spouse’s or common-law partner’s education 3 -5 Minimum one year full-time authorized work in Canada 5 Minimum two years full-time authorized postsecondary study in Canada 5 Have received points under the Arranged Employment in Canada factor 5 Family relationship in Canada 5 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Selection Factor: Adaptability Factor Six: Adaptability Maximum 10 points Spouse’s or common-law partner’s education 3 -5 Minimum one year full-time authorized work in Canada 5 Minimum two years full-time authorized postsecondary study in Canada 5 Have received points under the Arranged Employment in Canada factor 5 Family relationship in Canada 5 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Six: 1974 – 1985 A period of big swings in the business cycle; immigration inflows were adjusted accordingly. n 1976: New Immigration Act defines the 3 main priorities of the immigration policy: . Priority 1: family reunification. Priority 2: humanitarian concerns. Priority 3: promotion of Canada’s economic, social demographic and cultural goals n These goals/priorities still form the core of our immigration policy The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Six: 1974 – 1985 A period of big swings in the business cycle; immigration inflows were adjusted accordingly. n 1976: New Immigration Act defines the 3 main priorities of the immigration policy: . Priority 1: family reunification. Priority 2: humanitarian concerns. Priority 3: promotion of Canada’s economic, social demographic and cultural goals n These goals/priorities still form the core of our immigration policy The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Seven: 1986 – 2002 n 1985: Report to Parliament on future immigration levels . fertility in Canada had fallen below replacement levels. economic component of the inflow should be increased but not at the expense of social and humanitarian streams 1992: Family class was reduced; government committed to stable inflows of about 1% of the current population n 1993: Size of the inflow increased to 250, 000 in spite of poor labour market – a major shift from the absorptive capacity policy to adaptability (labour market indicators) n The switch to long term goals and the desire to increase the numbers of skilled workers continued through the 1990 s (the birth of “designer immigration”) n The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Seven: 1986 – 2002 n 1985: Report to Parliament on future immigration levels . fertility in Canada had fallen below replacement levels. economic component of the inflow should be increased but not at the expense of social and humanitarian streams 1992: Family class was reduced; government committed to stable inflows of about 1% of the current population n 1993: Size of the inflow increased to 250, 000 in spite of poor labour market – a major shift from the absorptive capacity policy to adaptability (labour market indicators) n The switch to long term goals and the desire to increase the numbers of skilled workers continued through the 1990 s (the birth of “designer immigration”) n The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

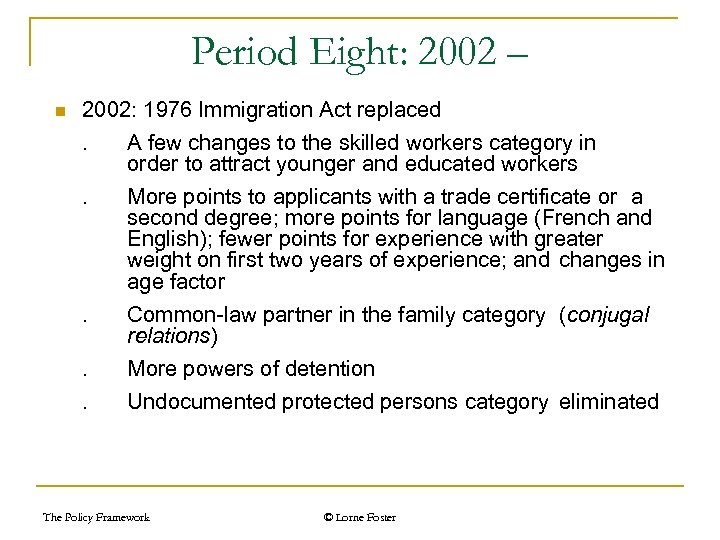

Period Eight: 2002 – n 2002: 1976 Immigration Act replaced. A few changes to the skilled workers category in order to attract younger and educated workers . More points to applicants with a trade certificate or a second degree; more points for language (French and English); fewer points for experience with greater weight on first two years of experience; and changes in age factor . Common-law partner in the family category (conjugal relations) . More powers of detention . Undocumented protected persons category eliminated The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Period Eight: 2002 – n 2002: 1976 Immigration Act replaced. A few changes to the skilled workers category in order to attract younger and educated workers . More points to applicants with a trade certificate or a second degree; more points for language (French and English); fewer points for experience with greater weight on first two years of experience; and changes in age factor . Common-law partner in the family category (conjugal relations) . More powers of detention . Undocumented protected persons category eliminated The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

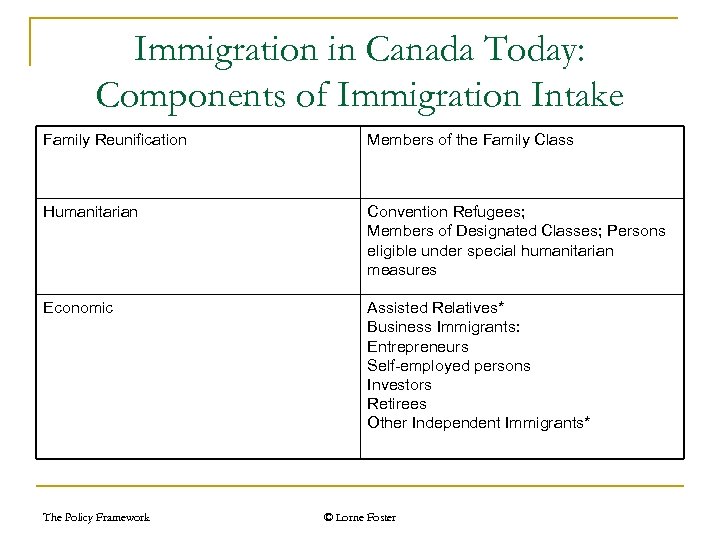

Immigration in Canada Today: Components of Immigration Intake Family Reunification Members of the Family Class Humanitarian Convention Refugees; Members of Designated Classes; Persons eligible under special humanitarian measures Economic Assisted Relatives* Business Immigrants: Entrepreneurs Self-employed persons Investors Retirees Other Independent Immigrants* The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Immigration in Canada Today: Components of Immigration Intake Family Reunification Members of the Family Class Humanitarian Convention Refugees; Members of Designated Classes; Persons eligible under special humanitarian measures Economic Assisted Relatives* Business Immigrants: Entrepreneurs Self-employed persons Investors Retirees Other Independent Immigrants* The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

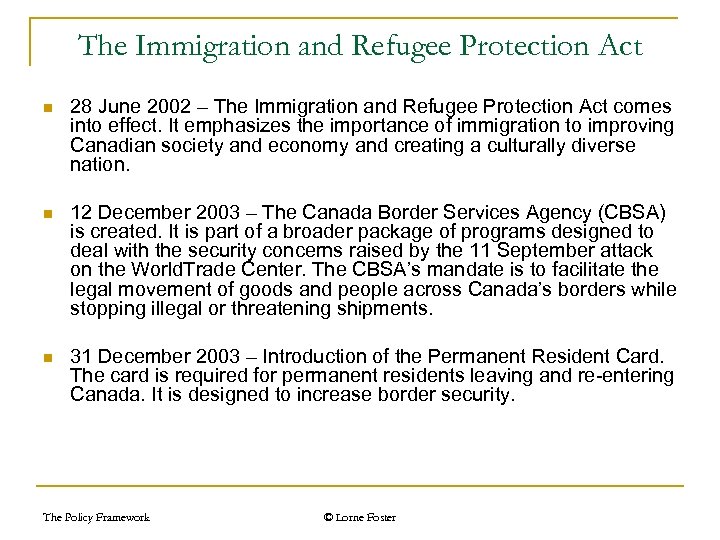

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act n 28 June 2002 – The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act comes into effect. It emphasizes the importance of immigration to improving Canadian society and economy and creating a culturally diverse nation. n 12 December 2003 – The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is created. It is part of a broader package of programs designed to deal with the security concerns raised by the 11 September attack on the World. Trade Center. The CBSA’s mandate is to facilitate the legal movement of goods and people across Canada’s borders while stopping illegal or threatening shipments. n 31 December 2003 – Introduction of the Permanent Resident Card. The card is required for permanent residents leaving and re-entering Canada. It is designed to increase border security. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act n 28 June 2002 – The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act comes into effect. It emphasizes the importance of immigration to improving Canadian society and economy and creating a culturally diverse nation. n 12 December 2003 – The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is created. It is part of a broader package of programs designed to deal with the security concerns raised by the 11 September attack on the World. Trade Center. The CBSA’s mandate is to facilitate the legal movement of goods and people across Canada’s borders while stopping illegal or threatening shipments. n 31 December 2003 – Introduction of the Permanent Resident Card. The card is required for permanent residents leaving and re-entering Canada. It is designed to increase border security. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

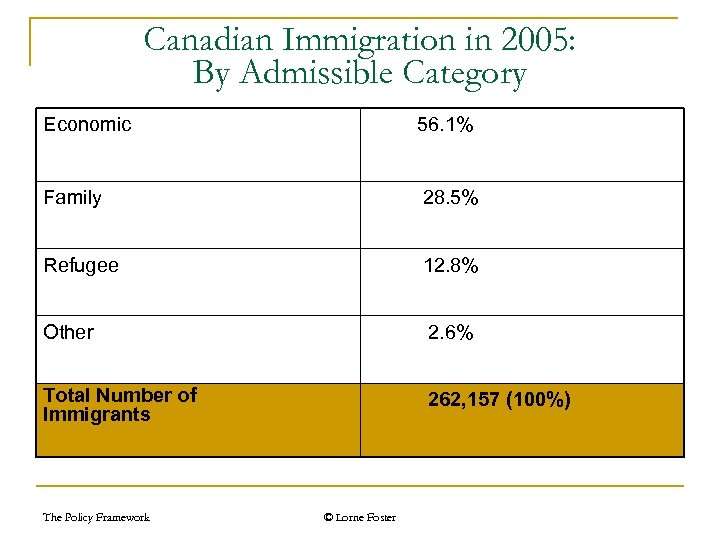

Canadian Immigration in 2005: By Admissible Category Economic 56. 1% Family 28. 5% Refugee 12. 8% Other 2. 6% Total Number of Immigrants 262, 157 (100%) The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Canadian Immigration in 2005: By Admissible Category Economic 56. 1% Family 28. 5% Refugee 12. 8% Other 2. 6% Total Number of Immigrants 262, 157 (100%) The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

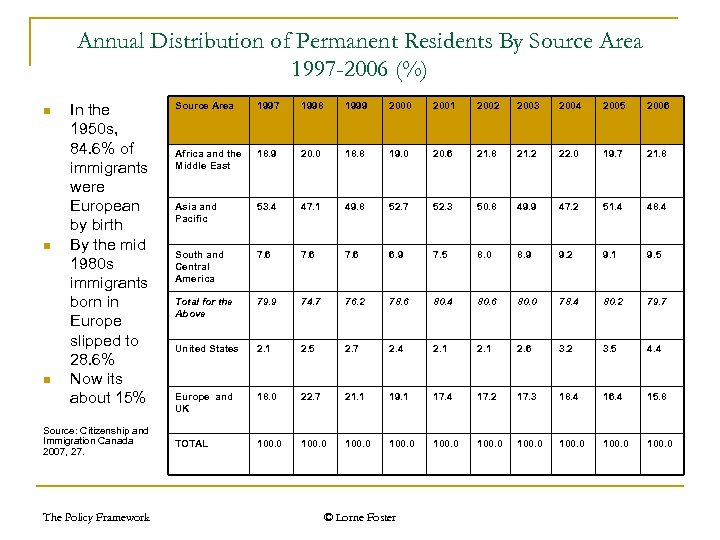

Annual Distribution of Permanent Residents By Source Area 1997 -2006 (%) n n n In the 1950 s, 84. 6% of immigrants were European by birth By the mid 1980 s immigrants born in Europe slipped to 28. 6% Now its about 15% Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2007, 27. The Policy Framework Source Area 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Africa and the Middle East 18. 9 20. 0 18. 8 19. 0 20. 6 21. 8 21. 2 22. 0 19. 7 21. 8 Asia and Pacific 53. 4 47. 1 49. 8 52. 7 52. 3 50. 8 49. 9 47. 2 51. 4 48. 4 South and Central America 7. 6 6. 9 7. 5 8. 0 8. 9 9. 2 9. 1 9. 5 Total for the Above 79. 9 74. 7 76. 2 78. 6 80. 4 80. 6 80. 0 78. 4 80. 2 79. 7 United States 2. 1 2. 5 2. 7 2. 4 2. 1 2. 6 3. 2 3. 5 4. 4 Europe and UK 18. 0 22. 7 21. 1 19. 1 17. 4 17. 2 17. 3 18. 4 16. 4 15. 8 TOTAL 100. 0 100. 0 © Lorne Foster

Annual Distribution of Permanent Residents By Source Area 1997 -2006 (%) n n n In the 1950 s, 84. 6% of immigrants were European by birth By the mid 1980 s immigrants born in Europe slipped to 28. 6% Now its about 15% Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2007, 27. The Policy Framework Source Area 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Africa and the Middle East 18. 9 20. 0 18. 8 19. 0 20. 6 21. 8 21. 2 22. 0 19. 7 21. 8 Asia and Pacific 53. 4 47. 1 49. 8 52. 7 52. 3 50. 8 49. 9 47. 2 51. 4 48. 4 South and Central America 7. 6 6. 9 7. 5 8. 0 8. 9 9. 2 9. 1 9. 5 Total for the Above 79. 9 74. 7 76. 2 78. 6 80. 4 80. 6 80. 0 78. 4 80. 2 79. 7 United States 2. 1 2. 5 2. 7 2. 4 2. 1 2. 6 3. 2 3. 5 4. 4 Europe and UK 18. 0 22. 7 21. 1 19. 1 17. 4 17. 2 17. 3 18. 4 16. 4 15. 8 TOTAL 100. 0 100. 0 © Lorne Foster

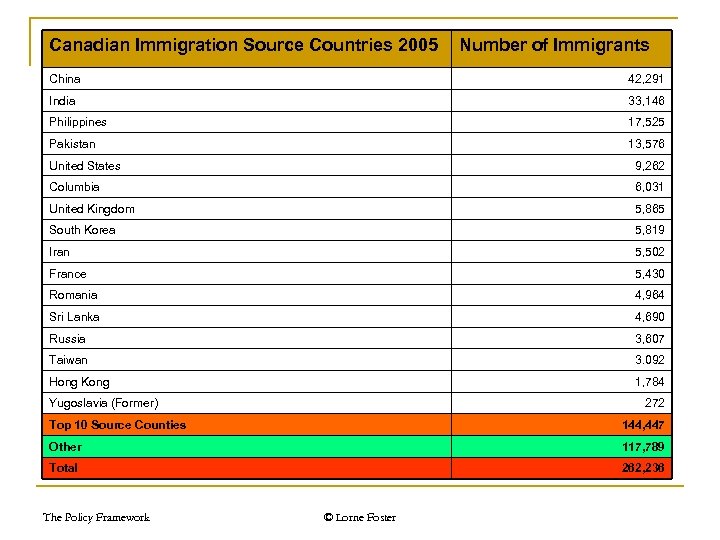

Canadian Immigration Source Countries 2005 Number of Immigrants China 42, 291 India 33, 146 Philippines 17, 525 Pakistan 13, 576 United States 9, 262 Columbia 6, 031 United Kingdom 5, 865 South Korea 5, 819 Iran 5, 502 France 5, 430 Romania 4, 964 Sri Lanka 4, 690 Russia 3, 607 Taiwan 3. 092 Hong Kong 1, 784 Yugoslavia (Former) 272 Top 10 Source Counties 144, 447 Other 117, 789 Total 262, 236 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Canadian Immigration Source Countries 2005 Number of Immigrants China 42, 291 India 33, 146 Philippines 17, 525 Pakistan 13, 576 United States 9, 262 Columbia 6, 031 United Kingdom 5, 865 South Korea 5, 819 Iran 5, 502 France 5, 430 Romania 4, 964 Sri Lanka 4, 690 Russia 3, 607 Taiwan 3. 092 Hong Kong 1, 784 Yugoslavia (Former) 272 Top 10 Source Counties 144, 447 Other 117, 789 Total 262, 236 The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

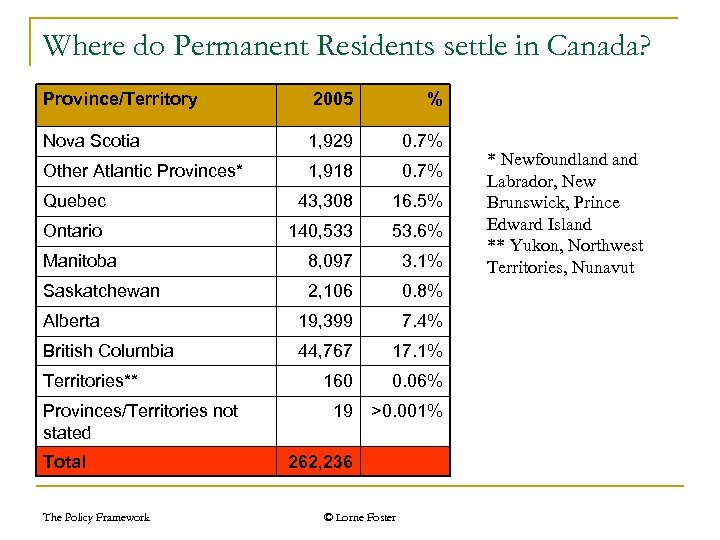

Where do Permanent Residents settle in Canada? Province/Territory 2005 % Nova Scotia 1, 929 0. 7% Other Atlantic Provinces* 1, 918 0. 7% Quebec 43, 308 16. 5% Ontario 140, 533 53. 6% Manitoba 8, 097 3. 1% Saskatchewan 2, 106 0. 8% Alberta 19, 399 7. 4% British Columbia 44, 767 17. 1% 160 0. 06% 19 >0. 001% Territories** Provinces/Territories not stated Total The Policy Framework 262, 236 © Lorne Foster * Newfoundland Labrador, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island ** Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut

Where do Permanent Residents settle in Canada? Province/Territory 2005 % Nova Scotia 1, 929 0. 7% Other Atlantic Provinces* 1, 918 0. 7% Quebec 43, 308 16. 5% Ontario 140, 533 53. 6% Manitoba 8, 097 3. 1% Saskatchewan 2, 106 0. 8% Alberta 19, 399 7. 4% British Columbia 44, 767 17. 1% 160 0. 06% 19 >0. 001% Territories** Provinces/Territories not stated Total The Policy Framework 262, 236 © Lorne Foster * Newfoundland Labrador, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island ** Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut

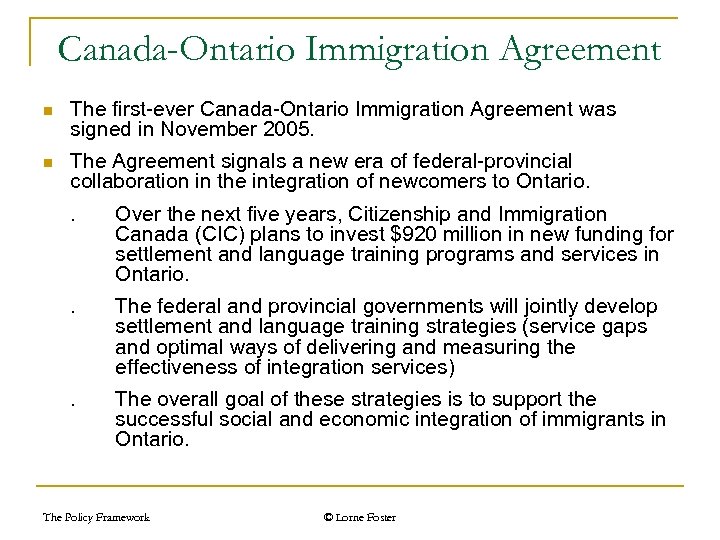

Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement n The first-ever Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement was signed in November 2005. n The Agreement signals a new era of federal-provincial collaboration in the integration of newcomers to Ontario. . Over the next five years, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) plans to invest $920 million in new funding for settlement and language training programs and services in Ontario. . The federal and provincial governments will jointly develop settlement and language training strategies (service gaps and optimal ways of delivering and measuring the effectiveness of integration services) . The overall goal of these strategies is to support the successful social and economic integration of immigrants in Ontario. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement n The first-ever Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement was signed in November 2005. n The Agreement signals a new era of federal-provincial collaboration in the integration of newcomers to Ontario. . Over the next five years, Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) plans to invest $920 million in new funding for settlement and language training programs and services in Ontario. . The federal and provincial governments will jointly develop settlement and language training strategies (service gaps and optimal ways of delivering and measuring the effectiveness of integration services) . The overall goal of these strategies is to support the successful social and economic integration of immigrants in Ontario. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

New Developments n Provincial Nominee Program (PNPs) are also in place with 10 jurisdictions (the Yukon and all provinces except Quebec), either as an annex to a framework agreement or as a stand-alone agreement. Under the PNP, provinces and territories have the authority to nominate individuals as permanent residents to address specific labour market and economic development needs. n Canada Experience Class program will allow temporary workers as well and international students to apply to become permanent residents. . n Aimed at people who want to immigrate to Canada and already have Canadian work experience or Canadian academic credentials. Perhaps as many as 12, 000 – 18, 000. The Immigration Backlog is now report as 900, 000. (This effectively means that newcomers face long processing delays, perhaps as along as five years). The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

New Developments n Provincial Nominee Program (PNPs) are also in place with 10 jurisdictions (the Yukon and all provinces except Quebec), either as an annex to a framework agreement or as a stand-alone agreement. Under the PNP, provinces and territories have the authority to nominate individuals as permanent residents to address specific labour market and economic development needs. n Canada Experience Class program will allow temporary workers as well and international students to apply to become permanent residents. . n Aimed at people who want to immigrate to Canada and already have Canadian work experience or Canadian academic credentials. Perhaps as many as 12, 000 – 18, 000. The Immigration Backlog is now report as 900, 000. (This effectively means that newcomers face long processing delays, perhaps as along as five years). The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Policy Challenge: Immigrants’ Skills Are Underutilized n Immigrants tend to start at a significant earnings disadvantage, . . n In 1980, the income of male immigrants represented 89% of the income of workers born in Canada In 2000, the income of immigrants fell to 77% relative to the income of workers born in Canada Unemployment rate shows the same trend. In 1981, the unemployment rate of immigrants (7. 1%) was lower than the unemployment rate of Canadians (7. 9%) . 20 years later, the unemployment rate of immigrants is 12. 7% compare to 7. 4% for workers born in Canada n The economic condition of newcomers in the country has worsened; the immigrants who are most affected belong to racial minorities n Annual cost of this problem: $2 billion The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Policy Challenge: Immigrants’ Skills Are Underutilized n Immigrants tend to start at a significant earnings disadvantage, . . n In 1980, the income of male immigrants represented 89% of the income of workers born in Canada In 2000, the income of immigrants fell to 77% relative to the income of workers born in Canada Unemployment rate shows the same trend. In 1981, the unemployment rate of immigrants (7. 1%) was lower than the unemployment rate of Canadians (7. 9%) . 20 years later, the unemployment rate of immigrants is 12. 7% compare to 7. 4% for workers born in Canada n The economic condition of newcomers in the country has worsened; the immigrants who are most affected belong to racial minorities n Annual cost of this problem: $2 billion The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

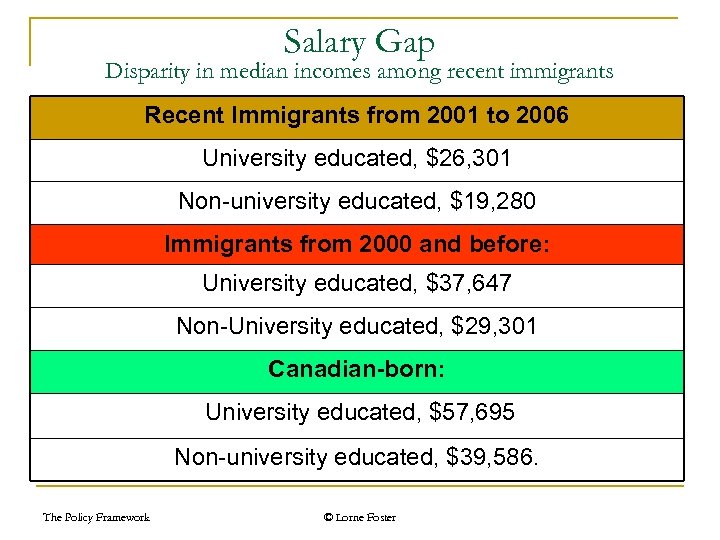

Salary Gap Disparity in median incomes among recent immigrants Recent Immigrants from 2001 to 2006 University educated, $26, 301 Non-university educated, $19, 280 Immigrants from 2000 and before: University educated, $37, 647 Non-University educated, $29, 301 Canadian-born: University educated, $57, 695 Non-university educated, $39, 586. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Salary Gap Disparity in median incomes among recent immigrants Recent Immigrants from 2001 to 2006 University educated, $26, 301 Non-university educated, $19, 280 Immigrants from 2000 and before: University educated, $37, 647 Non-University educated, $29, 301 Canadian-born: University educated, $57, 695 Non-university educated, $39, 586. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Policy Challenge: Immigrants’ Skills Are Underutilized n n Principal Cause: the non-recognition of foreign education and foreign experience • Canadian workers are increasingly educated, employers have access to a qualified workforce and prefer to hire Canadianeducated workers with domestic experience • Professional associations are often accused of placing too many barriers in front of otherwise qualified immigrants • Even with a work authorization given by a professional association, there is still an earnings gap of 15% between newcomers and the Canadian-born – limited access to senior/management positions The earnings gap for workers outside the knowledge economy (mostly regulated by professional association) represents a 30% difference Most newcomers will not be part of the knowledge economy Cultural hegemony is the new head tax to exclude the ‘undesirable, ’ and to perpetuate oppression in Canada. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Policy Challenge: Immigrants’ Skills Are Underutilized n n Principal Cause: the non-recognition of foreign education and foreign experience • Canadian workers are increasingly educated, employers have access to a qualified workforce and prefer to hire Canadianeducated workers with domestic experience • Professional associations are often accused of placing too many barriers in front of otherwise qualified immigrants • Even with a work authorization given by a professional association, there is still an earnings gap of 15% between newcomers and the Canadian-born – limited access to senior/management positions The earnings gap for workers outside the knowledge economy (mostly regulated by professional association) represents a 30% difference Most newcomers will not be part of the knowledge economy Cultural hegemony is the new head tax to exclude the ‘undesirable, ’ and to perpetuate oppression in Canada. The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Potential Solutions n The Canadian government has recently announced that it will increase immigration – yet, most of our newcomers today are visible minorities • To help mitigate possible social tensions, governments (federal, provincial and municipal) have a role to play in establishing coherent policy • Some potential initiatives include: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Better sources of information for immigrants, before and after arrival Bridge-training programs to “top-up” immigrants’ skills or fill in the gaps Subsidized workplace internship and mentoring programs More support for credential assessment services to improve labour market effectiveness Improved public awareness of the problems faced by skilled immigrants in integrating into the Canadian labour market and the consequences for Canadian society The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster

Potential Solutions n The Canadian government has recently announced that it will increase immigration – yet, most of our newcomers today are visible minorities • To help mitigate possible social tensions, governments (federal, provincial and municipal) have a role to play in establishing coherent policy • Some potential initiatives include: 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Better sources of information for immigrants, before and after arrival Bridge-training programs to “top-up” immigrants’ skills or fill in the gaps Subsidized workplace internship and mentoring programs More support for credential assessment services to improve labour market effectiveness Improved public awareness of the problems faced by skilled immigrants in integrating into the Canadian labour market and the consequences for Canadian society The Policy Framework © Lorne Foster