Biligual mind.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 38

THE BILINGUAL MIND

Outline • How successful can you be if you start learning a second language as an adult? • What are the differences between “early” bilingualism in childhood and “late” bilingualism in adulthood? • What happens to your first language after you have been speaking a second language for many years?

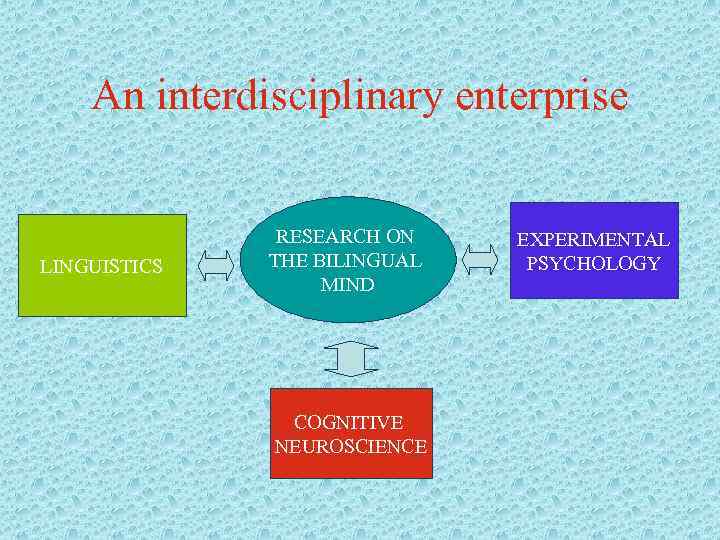

An interdisciplinary enterprise LINGUISTICS RESEARCH ON THE BILINGUAL MIND COGNITIVE NEUROSCIENCE EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY

A “critical period” for language? • In many animal species, failure to learn various skills before a certain age makes it difficult or even impossible to learn those skills later. E. g. : • In ducklings: ability to identify and follow the mother • In kittens: ability to perceive visual images. • In sparrows: ability to learn the father’s song.

Early exposure to language is necessary • Children raised in conditions of extreme isolation and deprivation do not develop normal grammatical abilities. • Deaf children of hearing parents who are diagnosed as deaf when they are 2 or 3 are impaired in their development of sign language.

Why a critical period for language? • A biological mechanism innately geared to the acquisition of language in our species. • Evolutionary advantages of having the mechanism early in life.

But what about SECOND language? • Does this mean that second language learning is compromised even if first language development was normal? • Does the fact of already knowing a language help?

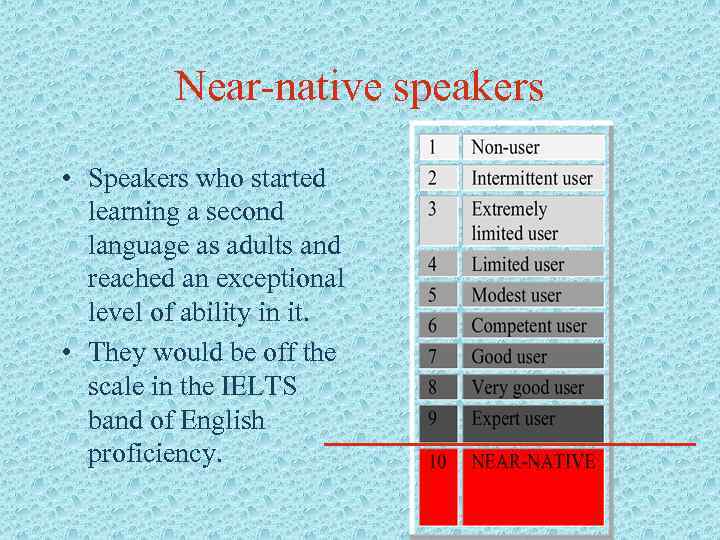

Near-native speakers • Speakers who started learning a second language as adults and reached an exceptional level of ability in it. • They would be off the scale in the IELTS band of English proficiency.

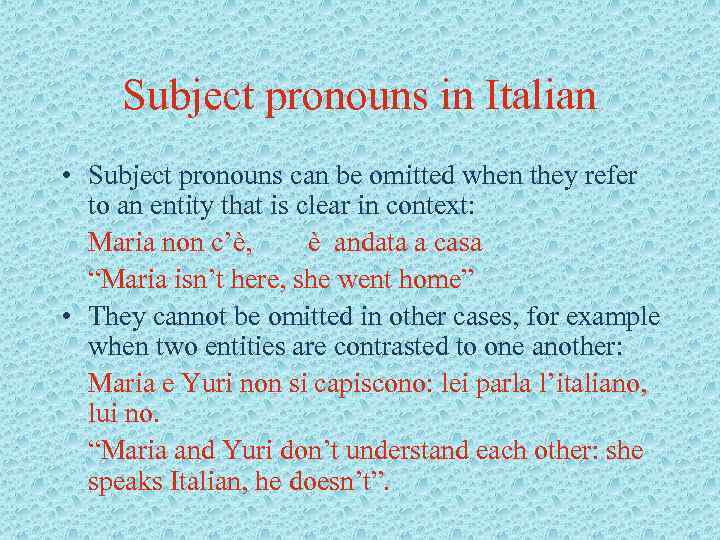

Subject pronouns in Italian • Subject pronouns can be omitted when they refer to an entity that is clear in context: Maria non c’è, è andata a casa “Maria isn’t here, she went home” • They cannot be omitted in other cases, for example when two entities are contrasted to one another: Maria e Yuri non si capiscono: lei parla l’italiano, lui no. “Maria and Yuri don’t understand each other: she speaks Italian, he doesn’t”.

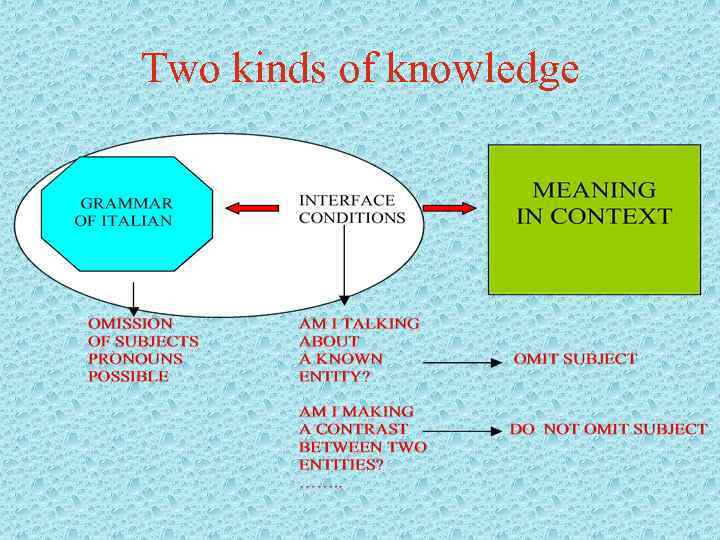

Two kinds of knowledge

Near-native speakers’ errors • Near-native speakers of Italian and Spanish may say: Maria non c’è, LEI è andata a casa. Maria isn’t here, she went home. • Is this due to interference from English?

Can’t be (only) interference from English • English and Spanish non-native speakers of Italian make the same mistake. • They know that in Italian subject pronouns can be omitted; they know what the contextual conditions are. • In most cases, they use subject pronouns correctly.

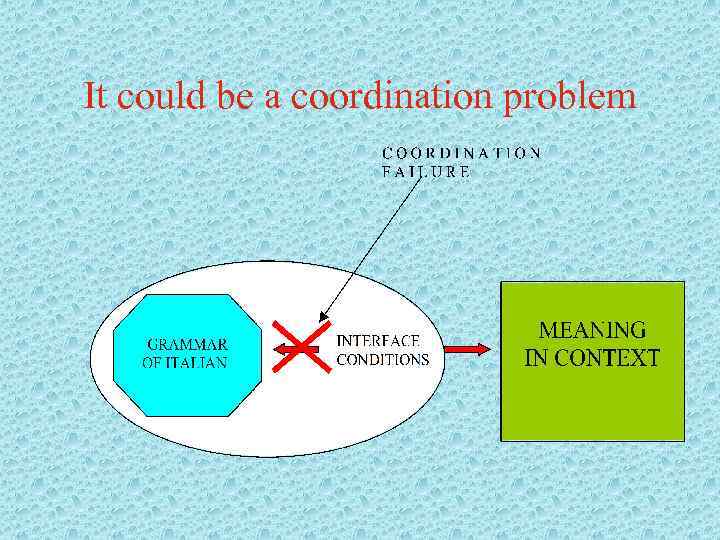

It could be a coordination problem

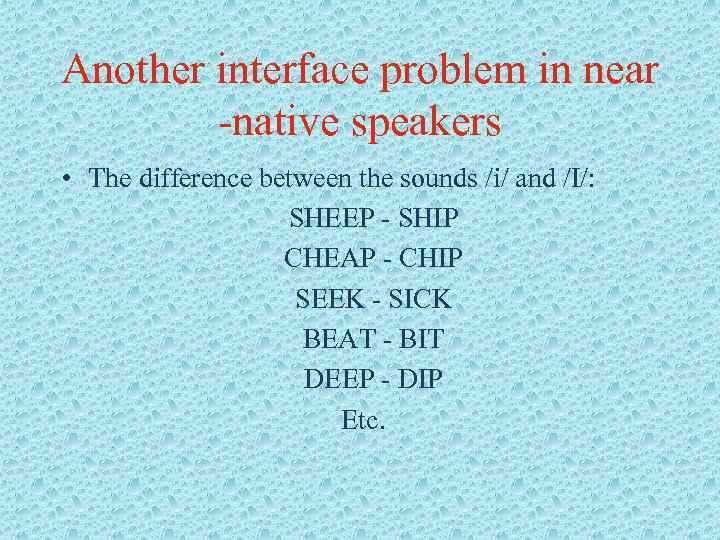

Another interface problem in near -native speakers • The difference between the sounds /i/ and /I/: SHEEP - SHIP CHEAP - CHIP SEEK - SICK BEAT - BIT DEEP - DIP Etc.

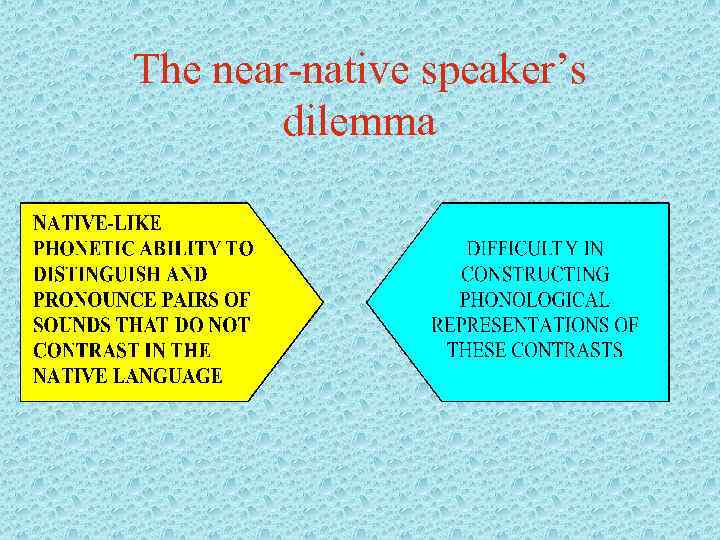

The near-native speaker’s dilemma

The ‘snickers vs. sneakers’ problem THIS…. . OR THIS?

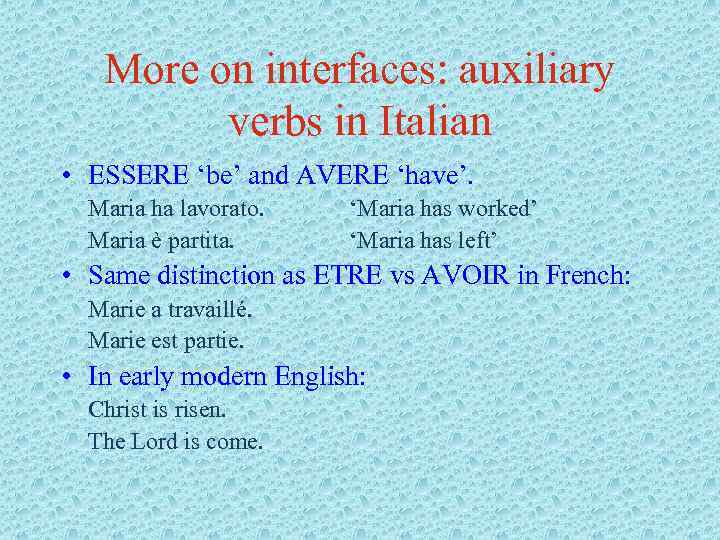

More on interfaces: auxiliary verbs in Italian • ESSERE ‘be’ and AVERE ‘have’. Maria ha lavorato. Maria è partita. ‘Maria has worked’ ‘Maria has left’ • Same distinction as ETRE vs AVOIR in French: Marie a travaillé. Marie est partie. • In early modern English: Christ is risen. The Lord is come.

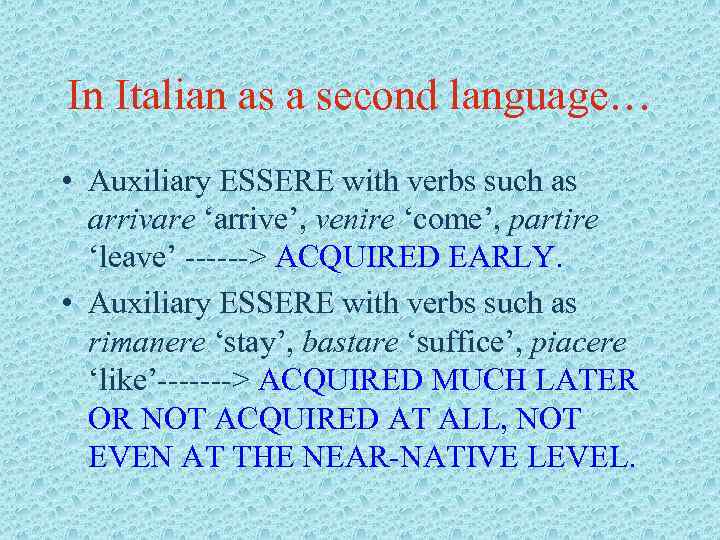

In Italian as a second language… • Auxiliary ESSERE with verbs such as arrivare ‘arrive’, venire ‘come’, partire ‘leave’ ------> ACQUIRED EARLY. • Auxiliary ESSERE with verbs such as rimanere ‘stay’, bastare ‘suffice’, piacere ‘like’-------> ACQUIRED MUCH LATER OR NOT ACQUIRED AT ALL, NOT EVEN AT THE NEAR-NATIVE LEVEL.

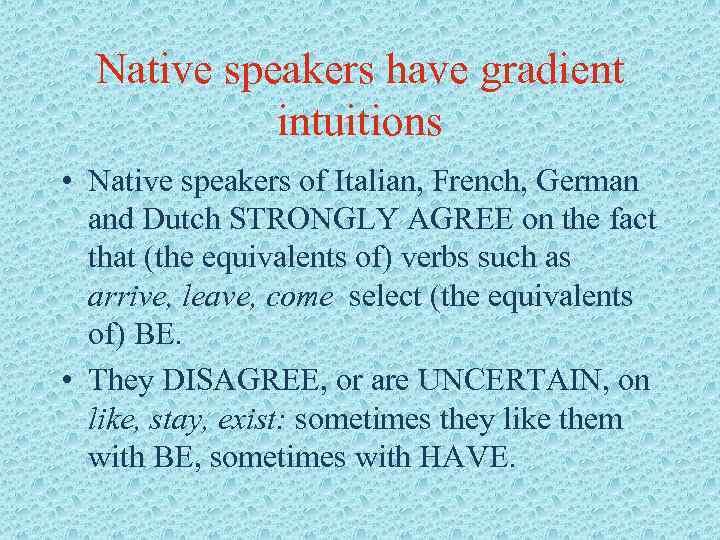

Native speakers have gradient intuitions • Native speakers of Italian, French, German and Dutch STRONGLY AGREE on the fact that (the equivalents of) verbs such as arrive, leave, come select (the equivalents of) BE. • They DISAGREE, or are UNCERTAIN, on like, stay, exist: sometimes they like them with BE, sometimes with HAVE.

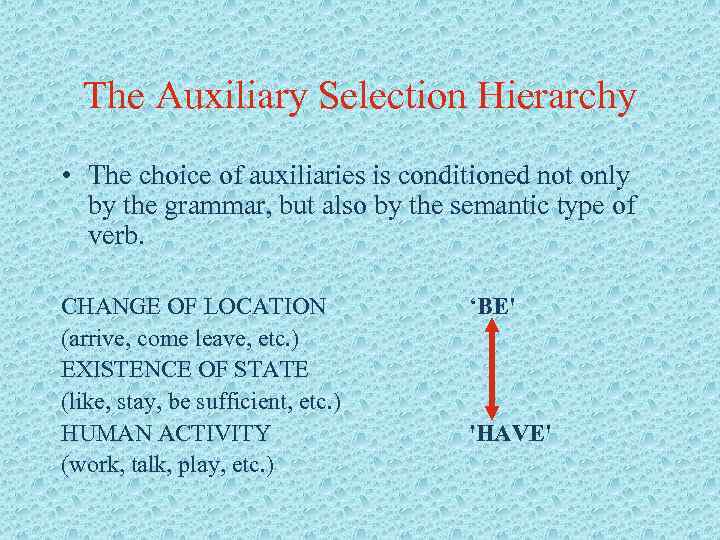

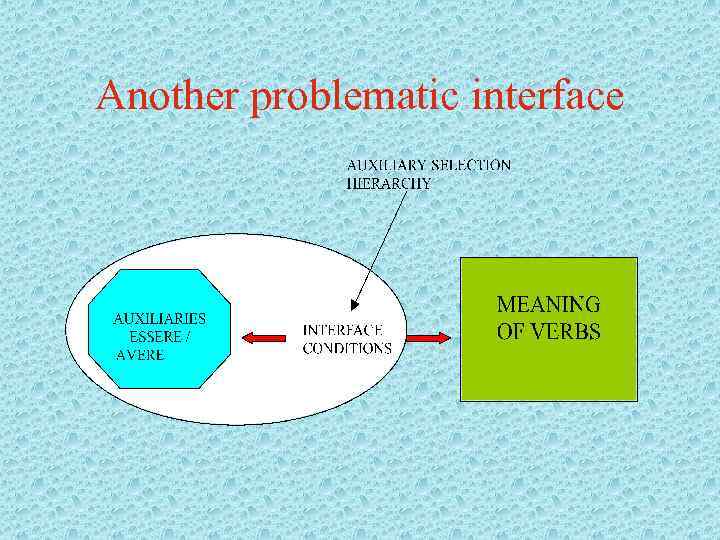

The Auxiliary Selection Hierarchy • The choice of auxiliaries is conditioned not only by the grammar, but also by the semantic type of verb. CHANGE OF LOCATION (arrive, come leave, etc. ) EXISTENCE OF STATE (like, stay, be sufficient, etc. ) HUMAN ACTIVITY (work, talk, play, etc. ) ‘BE' 'HAVE'

Another problematic interface

A methodological spin-off: how to detect gradience • If developmental data are gradient, we need a method that can detect gradience. • Magnitude estimation, a method borrowed from psychophysics, allows researchers to capture fine ‘shades of gray’ in judgments of linguistic acceptability. • See http: //www. webexp. info for a webbased application of Magnitude Estimation developed by Frank Kellet and Martin Corley.

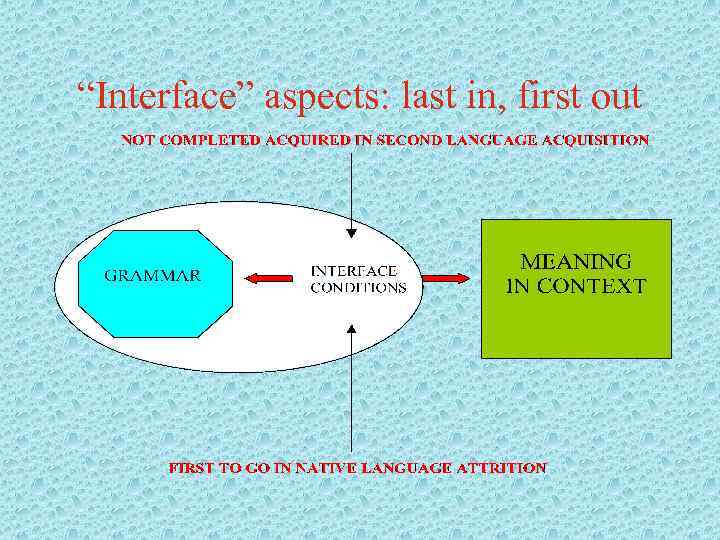

The story so far • Many properties of grammar can be successfully acquired in a second language, but properties that involve interfaces between different aspects of language may remain non-native even at the highest level of attainment.

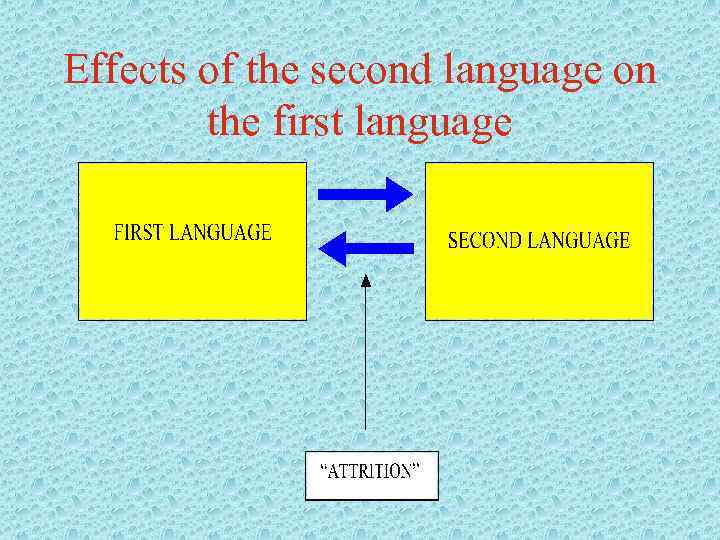

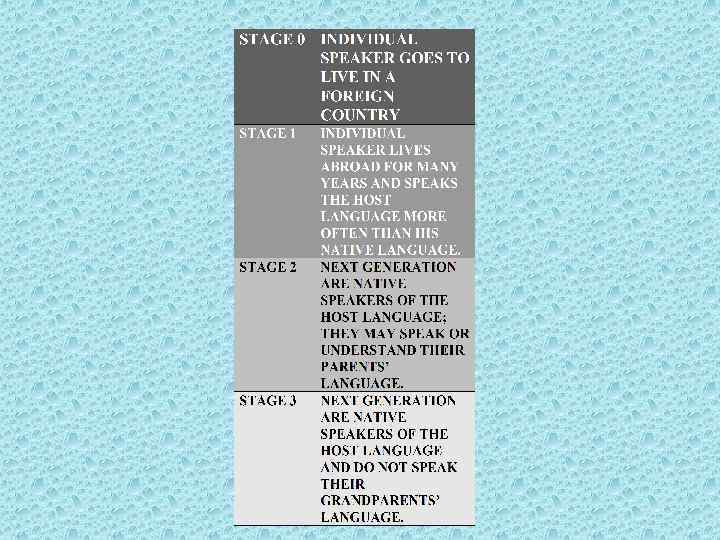

What happens to your first language after you have been speaking a second language for a long time?

Effects of the second language on the first language

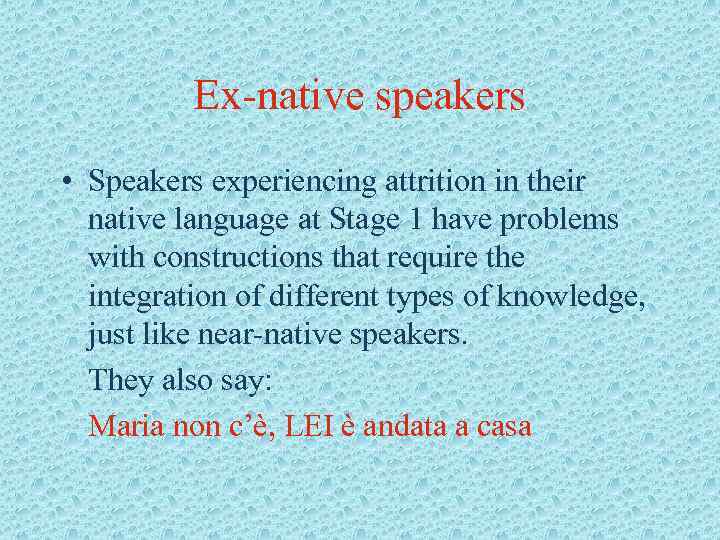

Ex-native speakers • Speakers experiencing attrition in their native language at Stage 1 have problems with constructions that require the integration of different types of knowledge, just like near-native speakers. They also say: Maria non c’è, LEI è andata a casa

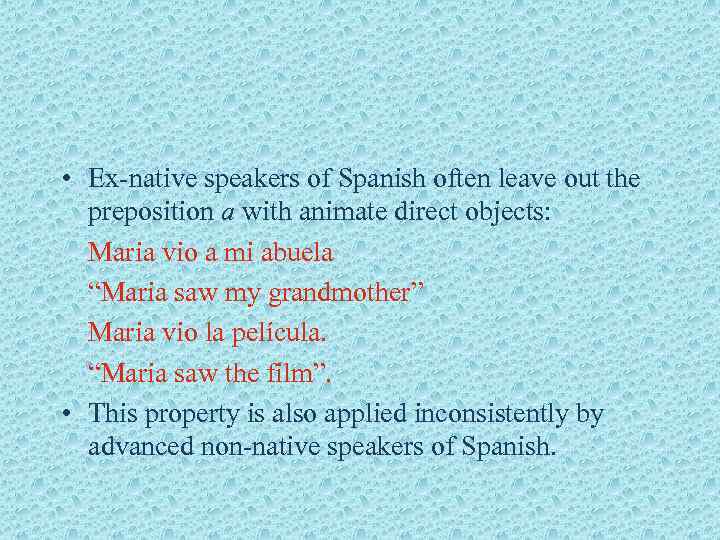

• Ex-native speakers of Spanish often leave out the preposition a with animate direct objects: Maria vio a mi abuela “Maria saw my grandmother” Maria vio la película. “Maria saw the film”. • This property is also applied inconsistently by advanced non-native speakers of Spanish.

“Interface” aspects: last in, first out

The broad view • Research on bilingual processing helps us to understand how human language processing works in general. • Research on bilinguals can inform computational models of natural language processing.

Bilingual first language acquisition (“early bilingualsim”) • Bilingual children develop two native languages, so in general reach higher levels of attainment than adult learners. • They do not normally mix their languages (unless they want to!). • How early do they differentiate the two languages they are acquiring?

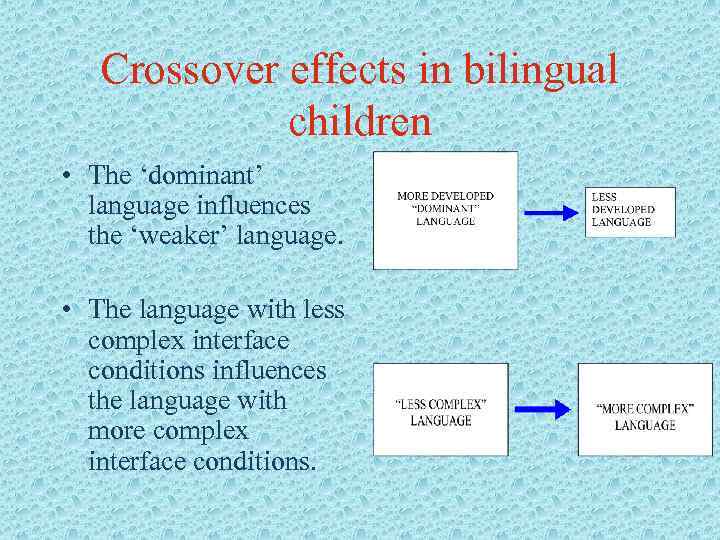

Crossover effects in bilingual children • The ‘dominant’ language influences the ‘weaker’ language. • The language with less complex interface conditions influences the language with more complex interface conditions.

Effects of input Bilingual children often hear: • Less input (in both languages) than monolingual children. • Non-native input in the minority language. • Input resulting from attrition (usually from the parent who is a native speaker of the minority language).

Effects of bilingualism on nonlinguistic tasks • Does the bilingual’s experience of constantly managing two linguistic systems have an effect on coordination in nonlinguistic tasks?

“Cognitive control” involves…. • Paying selective attention to the relevant aspects of a problem • Inhibiting attention to irrelevant information • Switching between competing alternatives.

Future research • Is there a difference between ‘early’ and ‘late’ bilinguals with respect to cognitive control in non-linguistic tasks? • The answer will bring us closer to understanding the relationship between language and other cognitive faculties.

The bilingual brain • Structural vs. functional factors: what are the neural substrates of bilinguals’ behaviour? • Does the bilingual brain have a different neural organization from the monolingual brain? • Does the bilingual brain have different neural substrates for the native and second language(s)?

To conclude: The cognitive study of the bilingual mind is an exciting interdisciplinary enterprise.

Biligual mind.ppt