2f92734e661689f05f4834e0836d51f0.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 58

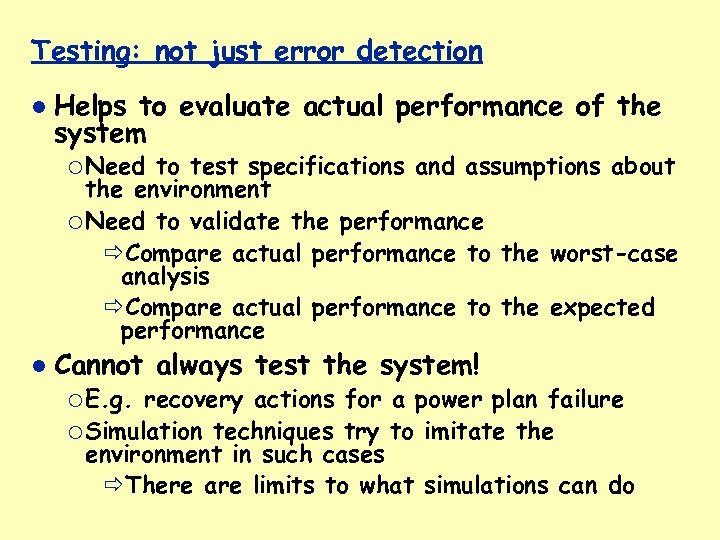

Testing: not just error detection Helps to evaluate actual performance of the system ¡ Need to test specifications and assumptions about the environment ¡ Need to validate the performance Compare actual performance to the worst-case analysis Compare actual performance to the expected performance Cannot always test the system! ¡ E. g. recovery actions for a power plan failure ¡ Simulation techniques try to imitate the environment in such cases There are limits to what simulations can do

Testing: not just error detection Helps to evaluate actual performance of the system ¡ Need to test specifications and assumptions about the environment ¡ Need to validate the performance Compare actual performance to the worst-case analysis Compare actual performance to the expected performance Cannot always test the system! ¡ E. g. recovery actions for a power plan failure ¡ Simulation techniques try to imitate the environment in such cases There are limits to what simulations can do

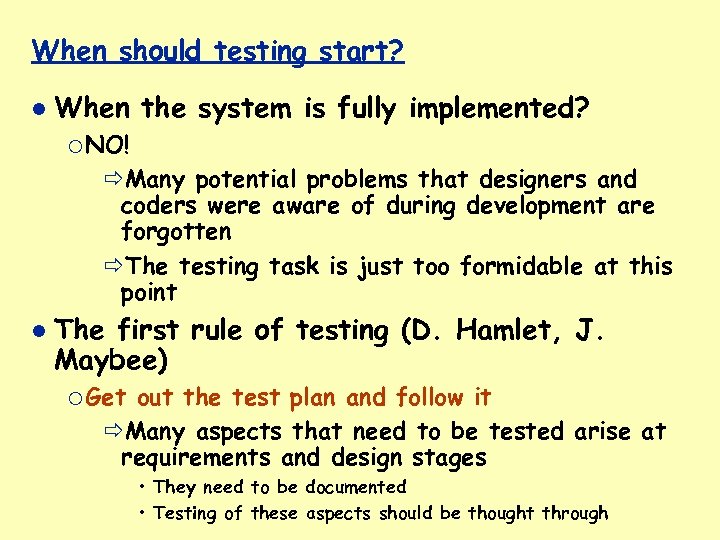

When should testing start? When the system is fully implemented? ¡ NO! Many potential problems that designers and coders were aware of during development are forgotten The testing task is just too formidable at this point The first rule of testing (D. Hamlet, J. Maybee) ¡ Get out the test plan and follow it Many aspects that need to be tested arise at requirements and design stages • They need to be documented • Testing of these aspects should be thought through

When should testing start? When the system is fully implemented? ¡ NO! Many potential problems that designers and coders were aware of during development are forgotten The testing task is just too formidable at this point The first rule of testing (D. Hamlet, J. Maybee) ¡ Get out the test plan and follow it Many aspects that need to be tested arise at requirements and design stages • They need to be documented • Testing of these aspects should be thought through

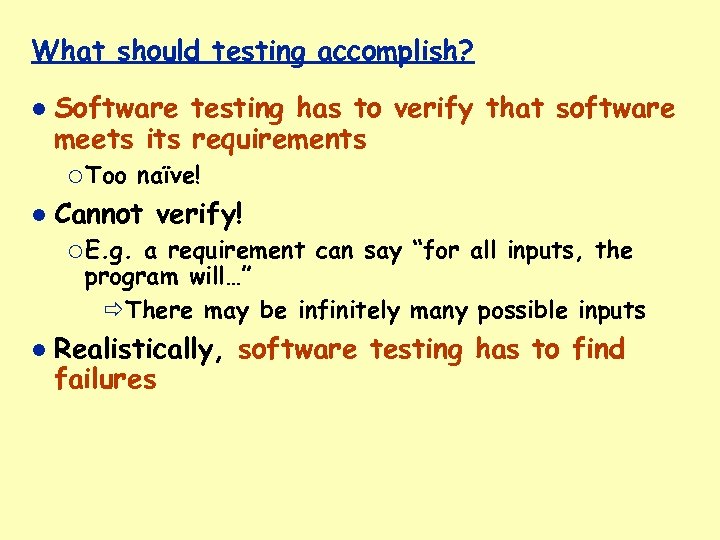

What should testing accomplish? Software testing has to verify that software meets its requirements ¡ Too naïve! Cannot verify! ¡ E. g. a requirement can say “for all inputs, the program will…” There may be infinitely many possible inputs Realistically, software testing has to find failures

What should testing accomplish? Software testing has to verify that software meets its requirements ¡ Too naïve! Cannot verify! ¡ E. g. a requirement can say “for all inputs, the program will…” There may be infinitely many possible inputs Realistically, software testing has to find failures

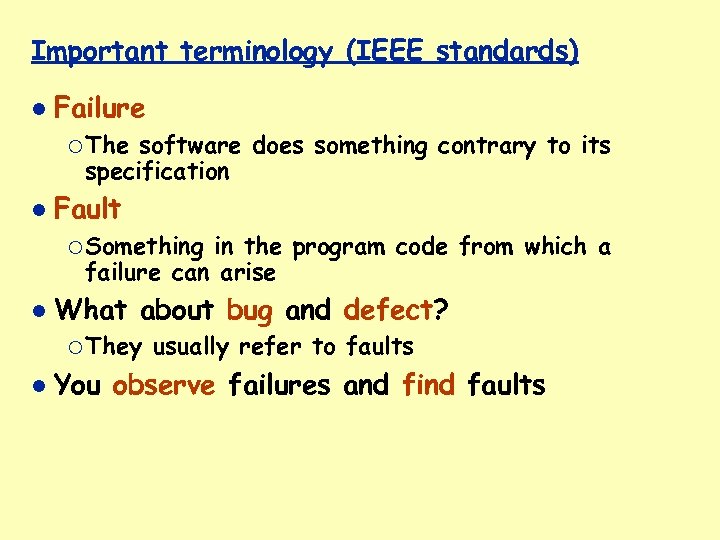

Important terminology (IEEE standards) Failure ¡ The software does something contrary to its specification Fault ¡ Something in the program code from which a failure can arise What about bug and defect? ¡ They usually refer to faults You observe failures and find faults

Important terminology (IEEE standards) Failure ¡ The software does something contrary to its specification Fault ¡ Something in the program code from which a failure can arise What about bug and defect? ¡ They usually refer to faults You observe failures and find faults

How does testing work? It’s not a simple question. The answer depends on many parameters ¡ The nature of the module being tested E. g. scientific computations vs. UI components ¡ What type of validation we are looking for Functionality • Behaves correctly • Looks correctly Performance Interoperability ¡ The way that testing is performed Viewing the module being tested as a black or white box ¡ The goals of testing Looking for bugs Proving to the users that the system “works” ¡…

How does testing work? It’s not a simple question. The answer depends on many parameters ¡ The nature of the module being tested E. g. scientific computations vs. UI components ¡ What type of validation we are looking for Functionality • Behaves correctly • Looks correctly Performance Interoperability ¡ The way that testing is performed Viewing the module being tested as a black or white box ¡ The goals of testing Looking for bugs Proving to the users that the system “works” ¡…

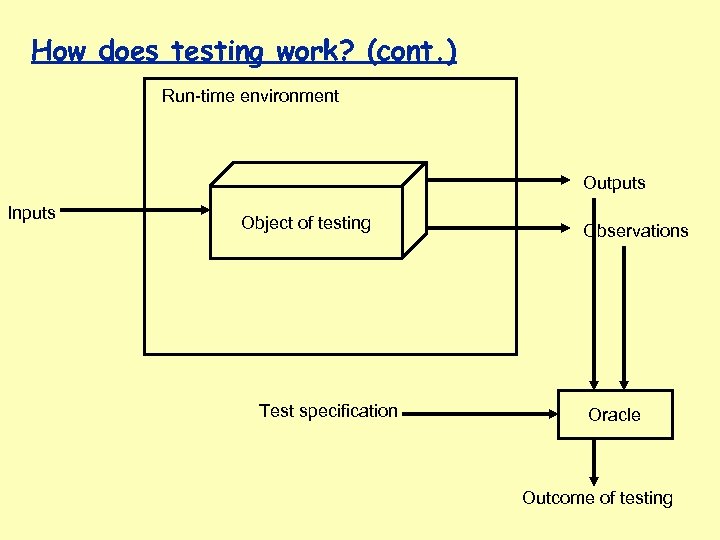

How does testing work? (cont. ) Run-time environment Outputs Inputs Object of testing Test specification Observations Oracle Outcome of testing

How does testing work? (cont. ) Run-time environment Outputs Inputs Object of testing Test specification Observations Oracle Outcome of testing

Types of testing, depending on purpose of testing Unit (or module) testing ¡ Individual components are tested independently E. g. class testing E. g. module testing Integration testing ¡ Testing interfaces between several subsystems the complete system System testing Acceptance testing ¡ Testing with the data supplied by the users May be done in the presence of users Regression testing ¡ Testing an incremental version of the system

Types of testing, depending on purpose of testing Unit (or module) testing ¡ Individual components are tested independently E. g. class testing E. g. module testing Integration testing ¡ Testing interfaces between several subsystems the complete system System testing Acceptance testing ¡ Testing with the data supplied by the users May be done in the presence of users Regression testing ¡ Testing an incremental version of the system

How do we select test cases By the number of test cases ¡ E. g. N random test cases Based on some properties of the system By their ability to detect faults

How do we select test cases By the number of test cases ¡ E. g. N random test cases Based on some properties of the system By their ability to detect faults

Test selection criteria There is an abstract domain D of all possible test cases (all possible inputs to the program or module) Let T be a subset of D A test selection criterion is a predicate that specifies whether test set T is in some sense “enough” to test the program or module Two uses for testing criteria: ¡ Stopping rule - know when the system has been tested enough ¡ Test data evaluation rule - evaluates quality of selected test cases Several testing criteria may be used at the same time

Test selection criteria There is an abstract domain D of all possible test cases (all possible inputs to the program or module) Let T be a subset of D A test selection criterion is a predicate that specifies whether test set T is in some sense “enough” to test the program or module Two uses for testing criteria: ¡ Stopping rule - know when the system has been tested enough ¡ Test data evaluation rule - evaluates quality of selected test cases Several testing criteria may be used at the same time

Ideal test selection criterion A test selection criterion is ideal if for any test set T that satisfies this criterion, T detects all errors, if any, in the program/module Of course, it is desirable that T is manageable in size, so that testing does not take forever In general, only the test criterion that requires running all tests in D is ideal

Ideal test selection criterion A test selection criterion is ideal if for any test set T that satisfies this criterion, T detects all errors, if any, in the program/module Of course, it is desirable that T is manageable in size, so that testing does not take forever In general, only the test criterion that requires running all tests in D is ideal

A test selection criterion can be useful even if not ideal A test criterion is useful if for any T that satisfies this criterion, if no errors are found by running tests from T then the program/model is highly reliable At present, no particularly good testing criteria exist ¡ Or at least, none of the existing ones have been proved particularly good

A test selection criterion can be useful even if not ideal A test criterion is useful if for any T that satisfies this criterion, if no errors are found by running tests from T then the program/model is highly reliable At present, no particularly good testing criteria exist ¡ Or at least, none of the existing ones have been proved particularly good

Test data selection techniques Random Interface based Fault based ¡ Error seeding (mutation testing) ¡ Fault constraints Error based ¡ Domain and computation based Coverage based ¡ Control flow ¡ Data flow

Test data selection techniques Random Interface based Fault based ¡ Error seeding (mutation testing) ¡ Fault constraints Error based ¡ Domain and computation based Coverage based ¡ Control flow ¡ Data flow

Random testing Based on a description of the test data, randomly select test cases Provides a statistical model of the reliability of the system ¡ If the system fails on one test case out of 100, expect it to perform correctly about 99% of the time ¡ Confidence in prediction increases as the number of test cases increases Practically, proved a reasonable testing strategy, especially if the results can be evaluated automatically Alternative testing techniques should be compared to random testing

Random testing Based on a description of the test data, randomly select test cases Provides a statistical model of the reliability of the system ¡ If the system fails on one test case out of 100, expect it to perform correctly about 99% of the time ¡ Confidence in prediction increases as the number of test cases increases Practically, proved a reasonable testing strategy, especially if the results can be evaluated automatically Alternative testing techniques should be compared to random testing

Black box vs. white box testing Black box testing ¡ Test case selection does not take the structure of the system into account ¡ Usually test cases are selected based on the types of inputs White box testing ¡ Test case selection is done by analyzing the structure/composition of the system

Black box vs. white box testing Black box testing ¡ Test case selection does not take the structure of the system into account ¡ Usually test cases are selected based on the types of inputs White box testing ¡ Test case selection is done by analyzing the structure/composition of the system

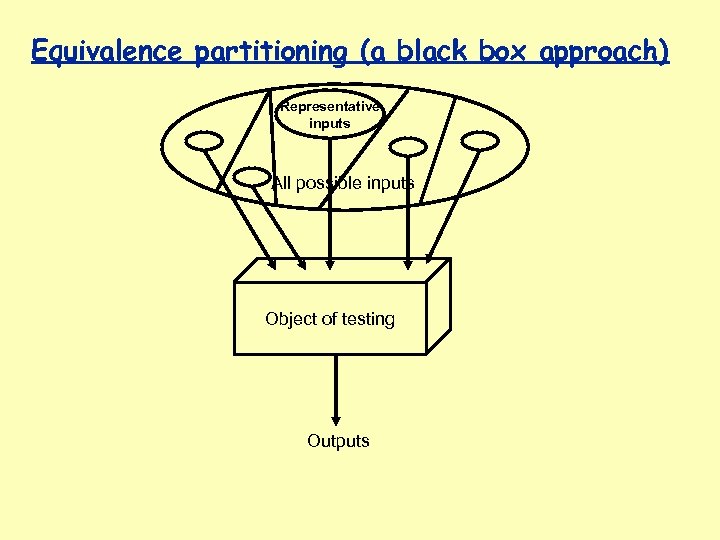

Equivalence partitioning (a black box approach) Representative inputs All possible inputs Object of testing Outputs

Equivalence partitioning (a black box approach) Representative inputs All possible inputs Object of testing Outputs

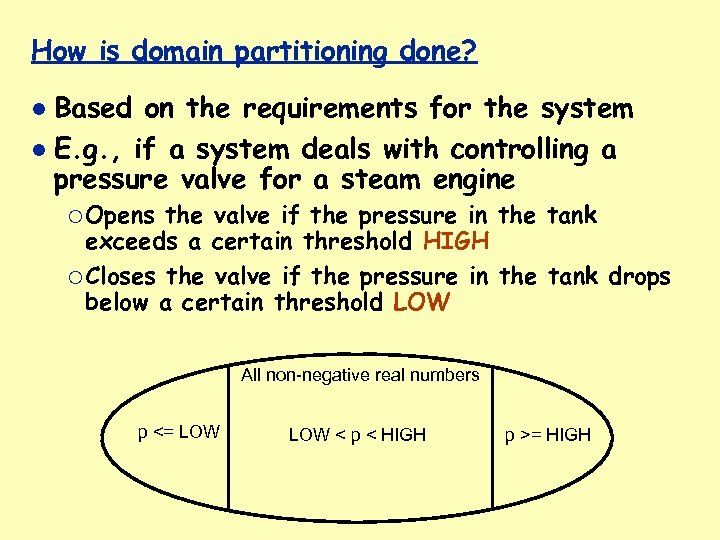

How is domain partitioning done? Based on the requirements for the system E. g. , if a system deals with controlling a pressure valve for a steam engine ¡ Opens the valve if the pressure in the tank exceeds a certain threshold HIGH ¡ Closes the valve if the pressure in the tank drops below a certain threshold LOW All non-negative real numbers p <= LOW < p < HIGH p >= HIGH

How is domain partitioning done? Based on the requirements for the system E. g. , if a system deals with controlling a pressure valve for a steam engine ¡ Opens the valve if the pressure in the tank exceeds a certain threshold HIGH ¡ Closes the valve if the pressure in the tank drops below a certain threshold LOW All non-negative real numbers p <= LOW < p < HIGH p >= HIGH

White-box (program-based) Test Data Selection structural ¡ coverage fault-based ¡ e. g. , based mutation testing, RELAY error-based ¡ domain and computation based ¡ use representations created by symbolic execution

White-box (program-based) Test Data Selection structural ¡ coverage fault-based ¡ e. g. , based mutation testing, RELAY error-based ¡ domain and computation based ¡ use representations created by symbolic execution

Coverage Criteria control-flow adequacy criteria G = (N, E, S, T) where ¡ the nodes N represent executable instructions (statement or statement fragment); ¡ the edges E represent the potential transfer of control; ¡ S is a designated start node; ¡ T is a designated final node ¡ E = { (ni, nj) | syntactically, the execution of nj follows the execution of ni}

Coverage Criteria control-flow adequacy criteria G = (N, E, S, T) where ¡ the nodes N represent executable instructions (statement or statement fragment); ¡ the edges E represent the potential transfer of control; ¡ S is a designated start node; ¡ T is a designated final node ¡ E = { (ni, nj) | syntactically, the execution of nj follows the execution of ni}

Control-Flow-Graph-Based Coverage Criteria Statement Coverage Path Coverage Branch Coverage Hidden Paths Loop Guidelines Boundary - Interior

Control-Flow-Graph-Based Coverage Criteria Statement Coverage Path Coverage Branch Coverage Hidden Paths Loop Guidelines Boundary - Interior

Selecting paths that satisfy the criteria static selection ¡ some of the associated paths may be infeasible dynamic selection ¡ monitors coverage and displays areas that have not been satisfactorily covered

Selecting paths that satisfy the criteria static selection ¡ some of the associated paths may be infeasible dynamic selection ¡ monitors coverage and displays areas that have not been satisfactorily covered

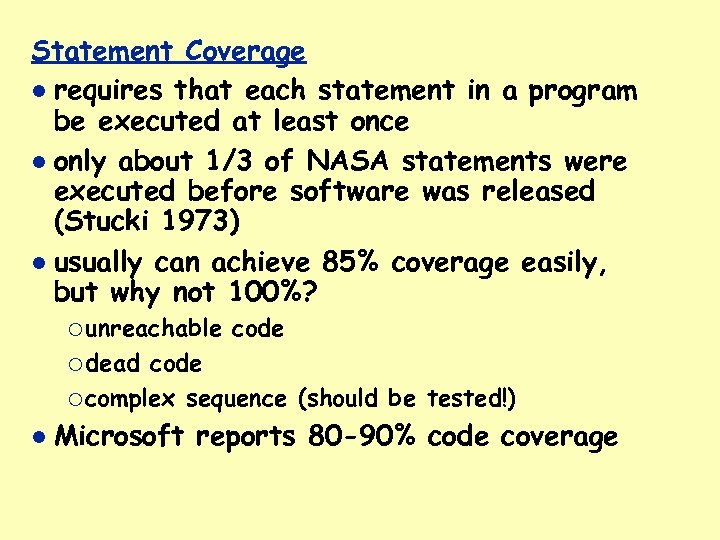

Statement Coverage requires that each statement in a program be executed at least once only about 1/3 of NASA statements were executed before software was released (Stucki 1973) usually can achieve 85% coverage easily, but why not 100%? ¡ unreachable code ¡ dead code ¡ complex sequence (should be tested!) Microsoft reports 80 -90% code coverage

Statement Coverage requires that each statement in a program be executed at least once only about 1/3 of NASA statements were executed before software was released (Stucki 1973) usually can achieve 85% coverage easily, but why not 100%? ¡ unreachable code ¡ dead code ¡ complex sequence (should be tested!) Microsoft reports 80 -90% code coverage

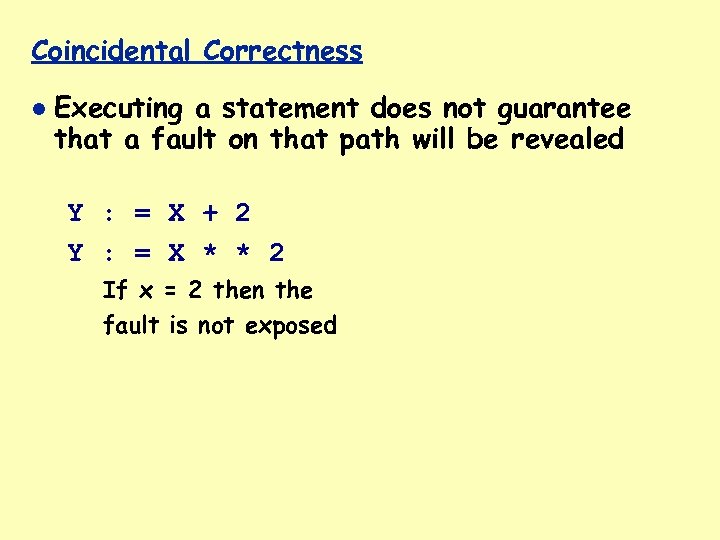

Coincidental Correctness Executing a statement does not guarantee that a fault on that path will be revealed Y : = X + 2 Y : = X * * 2 If x = 2 then the fault is not exposed

Coincidental Correctness Executing a statement does not guarantee that a fault on that path will be revealed Y : = X + 2 Y : = X * * 2 If x = 2 then the fault is not exposed

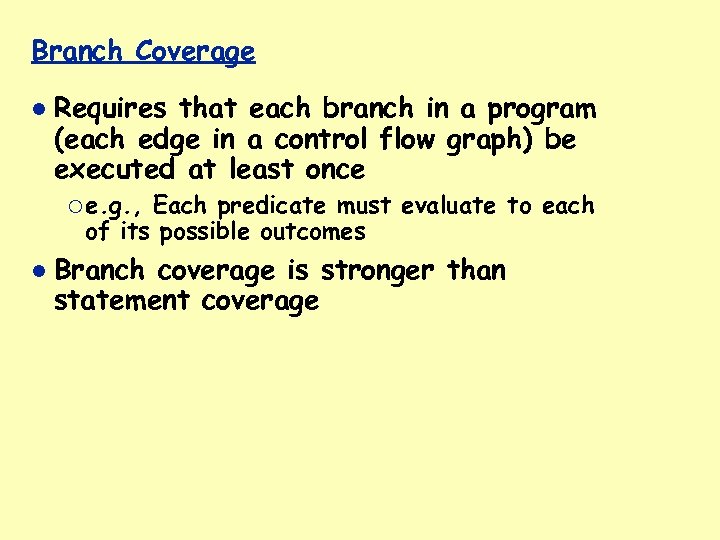

Branch Coverage Requires that each branch in a program (each edge in a control flow graph) be executed at least once ¡ e. g. , Each predicate must evaluate to each of its possible outcomes Branch coverage is stronger than statement coverage

Branch Coverage Requires that each branch in a program (each edge in a control flow graph) be executed at least once ¡ e. g. , Each predicate must evaluate to each of its possible outcomes Branch coverage is stronger than statement coverage

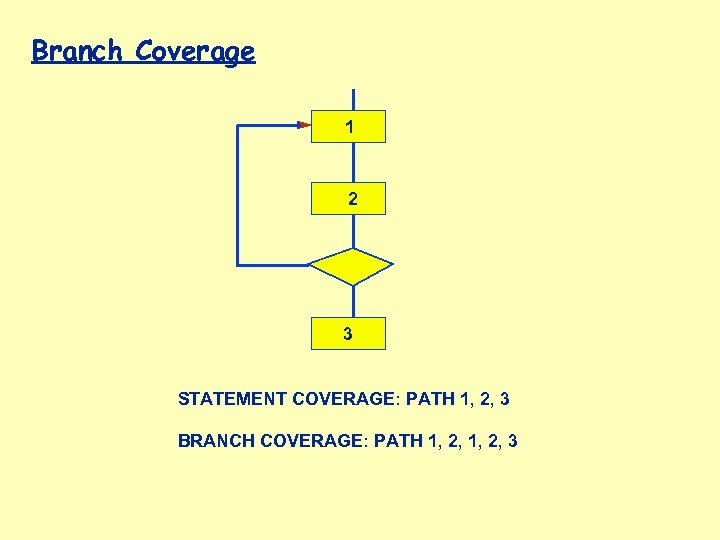

Branch Coverage 1 2 3 STATEMENT COVERAGE: PATH 1, 2, 3 BRANCH COVERAGE: PATH 1, 2, 3

Branch Coverage 1 2 3 STATEMENT COVERAGE: PATH 1, 2, 3 BRANCH COVERAGE: PATH 1, 2, 3

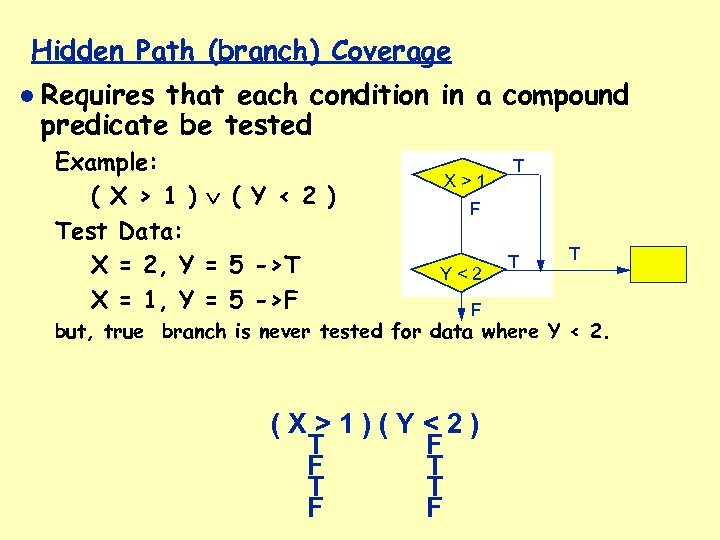

Hidden Path (branch) Coverage Requires that each condition in a compound predicate be tested Example: ( X > 1 ) ( Y < 2 ) Test Data: X = 2, Y = 5 ->T X = 1, Y = 5 ->F X>1 T F Y<2 F T T but, true branch is never tested for data where Y < 2. (X>1)(Y<2) T F F T T T F F

Hidden Path (branch) Coverage Requires that each condition in a compound predicate be tested Example: ( X > 1 ) ( Y < 2 ) Test Data: X = 2, Y = 5 ->T X = 1, Y = 5 ->F X>1 T F Y<2 F T T but, true branch is never tested for data where Y < 2. (X>1)(Y<2) T F F T T T F F

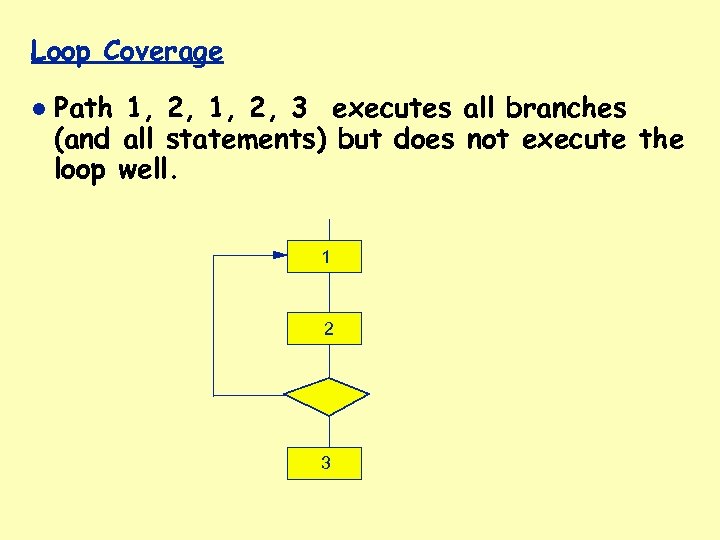

Loop Coverage Path 1, 2, 3 executes all branches (and all statements) but does not execute the loop well. 1 2 3

Loop Coverage Path 1, 2, 3 executes all branches (and all statements) but does not execute the loop well. 1 2 3

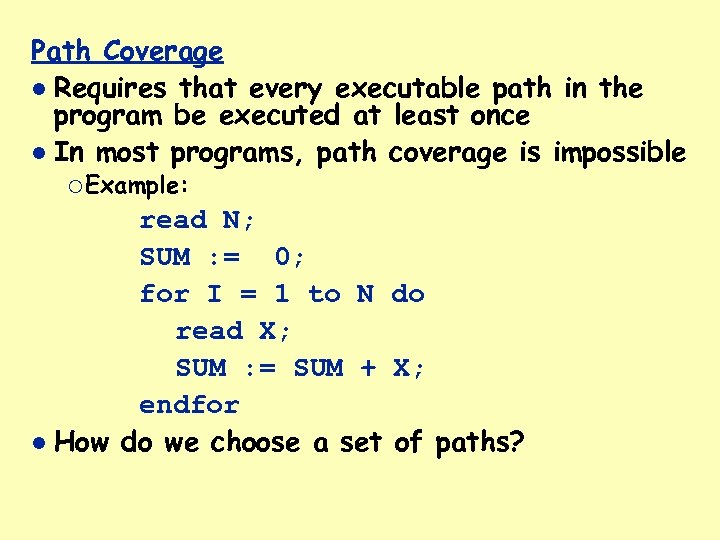

Path Coverage Requires that every executable path in the program be executed at least once In most programs, path coverage is impossible ¡ Example: read N; SUM : = 0; for I = 1 to N do read X; SUM : = SUM + X; endfor How do we choose a set of paths?

Path Coverage Requires that every executable path in the program be executed at least once In most programs, path coverage is impossible ¡ Example: read N; SUM : = 0; for I = 1 to N do read X; SUM : = SUM + X; endfor How do we choose a set of paths?

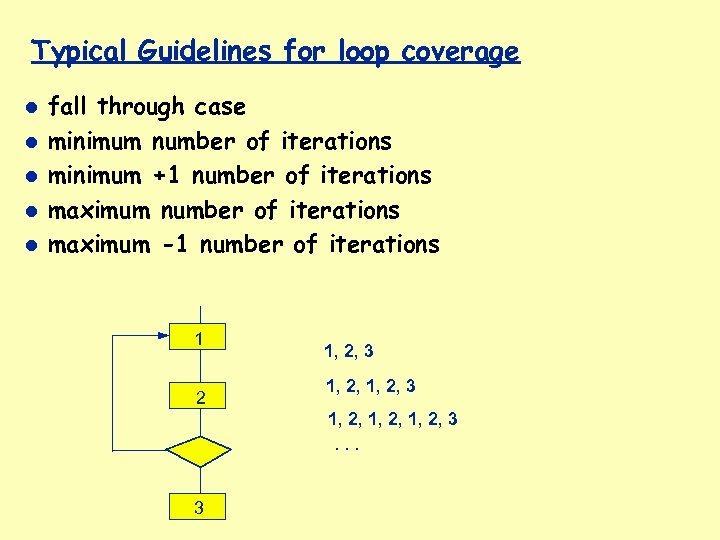

Typical Guidelines for loop coverage fall through case minimum number of iterations minimum +1 number of iterations maximum -1 number of iterations 1 2 1, 2, 3 1, 2, 3. . . 3

Typical Guidelines for loop coverage fall through case minimum number of iterations minimum +1 number of iterations maximum -1 number of iterations 1 2 1, 2, 3 1, 2, 3. . . 3

Boundary - Interior Criteria boundary test of a loop causes the loop to be entered but not iterated interior test of a loop causes a loop to be entered and then iterated at least once both boundary and interior tests are to be selected for each unique path through the loop

Boundary - Interior Criteria boundary test of a loop causes the loop to be entered but not iterated interior test of a loop causes a loop to be entered and then iterated at least once both boundary and interior tests are to be selected for each unique path through the loop

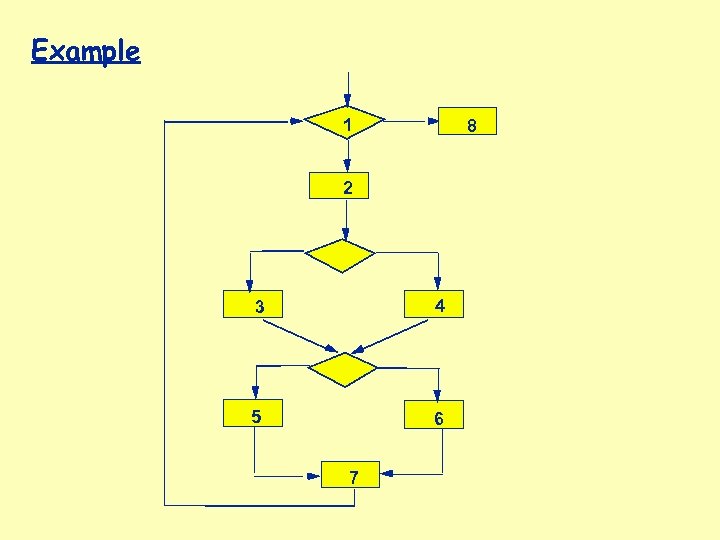

Example 1 8 2 3 4 5 6 7

Example 1 8 2 3 4 5 6 7

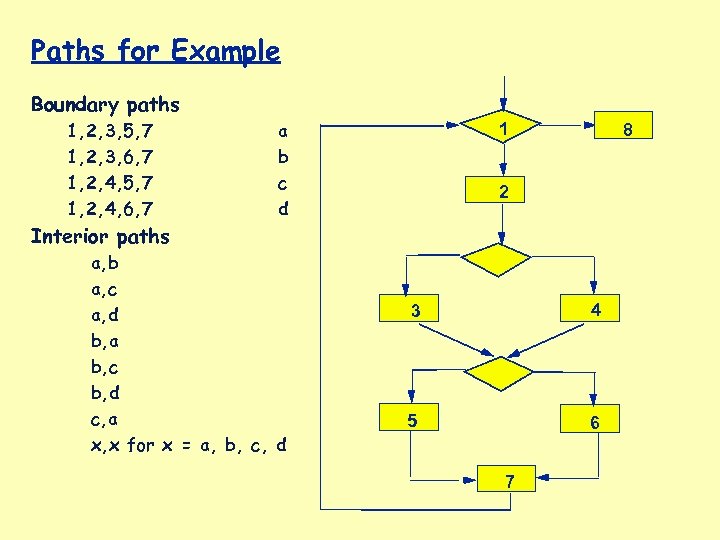

Paths for Example Boundary paths 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 1, 2, 4, 6, 7 a b c d 1 8 2 Interior paths a, b a, c a, d b, a b, c b, d c, a x, x for x = a, b, c, d 3 4 5 6 7

Paths for Example Boundary paths 1, 2, 3, 5, 7 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 1, 2, 4, 6, 7 a b c d 1 8 2 Interior paths a, b a, c a, d b, a b, c b, d c, a x, x for x = a, b, c, d 3 4 5 6 7

Validating Object Oriented Systems Do OO systems make validation harder or easier? ¡ Does code reuse lead to validation reuse? Do we need to change existing techniques? Do we need to develop new techniques?

Validating Object Oriented Systems Do OO systems make validation harder or easier? ¡ Does code reuse lead to validation reuse? Do we need to change existing techniques? Do we need to develop new techniques?

Issues in O-O testing basic unit for unit testing implications of encapsulation implications of inheritance implications of genericity implications of polymorphism/dynamic binding implications for integration testing

Issues in O-O testing basic unit for unit testing implications of encapsulation implications of inheritance implications of genericity implications of polymorphism/dynamic binding implications for integration testing

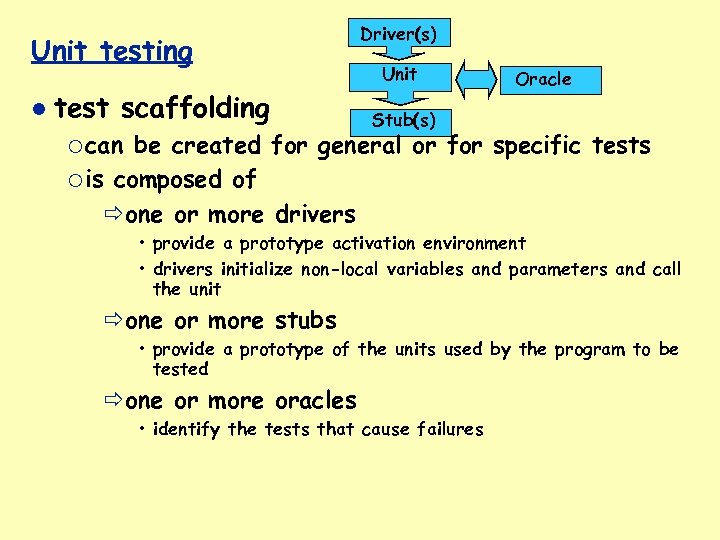

Unit testing test scaffolding ¡ can Driver(s) Unit Oracle Stub(s) be created for general or for specific tests ¡ is composed of one or more drivers • provide a prototype activation environment • drivers initialize non-local variables and parameters and call the unit one or more stubs • provide a prototype of the units used by the program to be tested one or more oracles • identify the tests that cause failures

Unit testing test scaffolding ¡ can Driver(s) Unit Oracle Stub(s) be created for general or for specific tests ¡ is composed of one or more drivers • provide a prototype activation environment • drivers initialize non-local variables and parameters and call the unit one or more stubs • provide a prototype of the units used by the program to be tested one or more oracles • identify the tests that cause failures

Unit Testing Object-Oriented systems procedural programming ¡ basic component: subroutine ¡ testing method: subroutine input/ output based object-oriented programming ¡ basic component: class = data structure + set of operations ¡ objects are instances of classes ¡ data structure defines the state of the object, thus correctness is not based only on output, but also on the state ¡ data structure is not directly accessible, but can only be accessed using the access methods (encapsulation)

Unit Testing Object-Oriented systems procedural programming ¡ basic component: subroutine ¡ testing method: subroutine input/ output based object-oriented programming ¡ basic component: class = data structure + set of operations ¡ objects are instances of classes ¡ data structure defines the state of the object, thus correctness is not based only on output, but also on the state ¡ data structure is not directly accessible, but can only be accessed using the access methods (encapsulation)

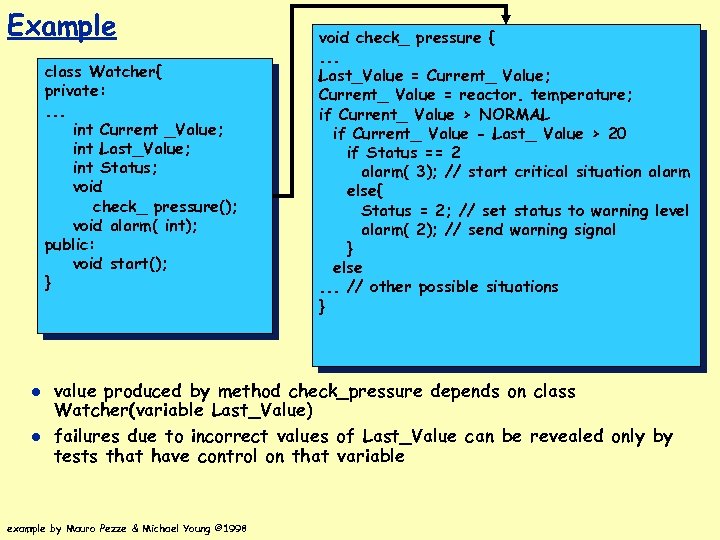

Example class Watcher{ private: . . . int Current _Value; int Last_Value; int Status; void check_ pressure(); void alarm( int); public: void start(); } void check_ pressure {. . . Last_Value = Current_ Value; Current_ Value = reactor. temperature; if Current_ Value > NORMAL if Current_ Value - Last_ Value > 20 if Status == 2 alarm( 3); // start critical situation alarm else{ Status = 2; // set status to warning level alarm( 2); // send warning signal } else. . . // other possible situations } value produced by method check_pressure depends on class Watcher(variable Last_Value) failures due to incorrect values of Last_Value can be revealed only by tests that have control on that variable example by Mauro Pezze & Michael Young © 1998

Example class Watcher{ private: . . . int Current _Value; int Last_Value; int Status; void check_ pressure(); void alarm( int); public: void start(); } void check_ pressure {. . . Last_Value = Current_ Value; Current_ Value = reactor. temperature; if Current_ Value > NORMAL if Current_ Value - Last_ Value > 20 if Status == 2 alarm( 3); // start critical situation alarm else{ Status = 2; // set status to warning level alarm( 2); // send warning signal } else. . . // other possible situations } value produced by method check_pressure depends on class Watcher(variable Last_Value) failures due to incorrect values of Last_Value can be revealed only by tests that have control on that variable example by Mauro Pezze & Michael Young © 1998

Basic Unit for Testing the class is the natural unit for unit test case design methods are meaningless apart from their class testing a class instance (an object) can verify a class in isolation when individually verified classes are used to create more complex classes in an application system, the entire subsystem must be tested as a whole before it can be considered to be verified (integration testing)

Basic Unit for Testing the class is the natural unit for unit test case design methods are meaningless apart from their class testing a class instance (an object) can verify a class in isolation when individually verified classes are used to create more complex classes in an application system, the entire subsystem must be tested as a whole before it can be considered to be verified (integration testing)

Encapsulation not a source of errors but may be an obstacle to testing how to get at the concrete state of an object? ¡ break the encapsulation using features of the languages • C++ • Ada 95 friend Child Unit use low level probes or debug tools to manually inspect

Encapsulation not a source of errors but may be an obstacle to testing how to get at the concrete state of an object? ¡ break the encapsulation using features of the languages • C++ • Ada 95 friend Child Unit use low level probes or debug tools to manually inspect

How to get at the concrete state of an object? Use the abstraction ¡ Scenarios--examine sequences of events ¡ State is implicitly inspected via access methods Use or provide hidden functions to examine the state ¡ Useful for debugging throughout the life of the system But modified code, may alter the behavior Especially true for languages that do not support strong typing

How to get at the concrete state of an object? Use the abstraction ¡ Scenarios--examine sequences of events ¡ State is implicitly inspected via access methods Use or provide hidden functions to examine the state ¡ Useful for debugging throughout the life of the system But modified code, may alter the behavior Especially true for languages that do not support strong typing

Implications of Inheritance inherited features often require re-testing ¡ because a new context of usage results when features are inherited multiple inheritance increases the number of contexts to test ¡ specialization relationships implementation specialization should correspond to problem domain specialization reusability of superclass test cases depends on this

Implications of Inheritance inherited features often require re-testing ¡ because a new context of usage results when features are inherited multiple inheritance increases the number of contexts to test ¡ specialization relationships implementation specialization should correspond to problem domain specialization reusability of superclass test cases depends on this

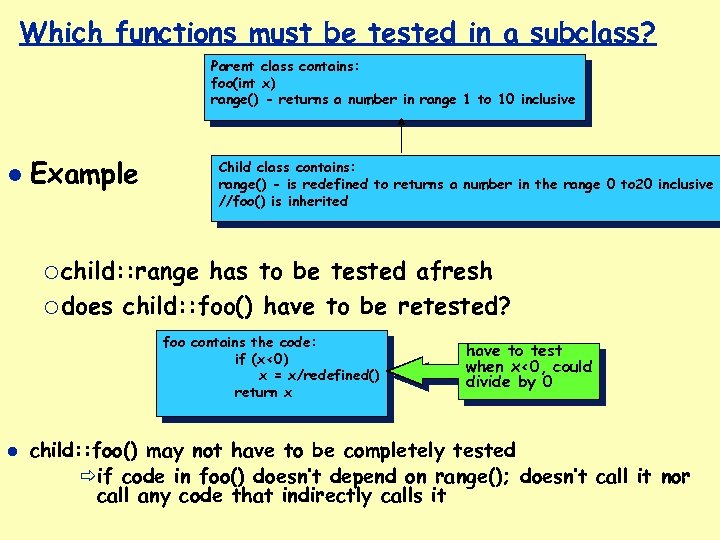

Which functions must be tested in a subclass? Parent class contains: foo(int x) range() - returns a number in range 1 to 10 inclusive Example Child class contains: range() - is redefined to returns a number in the range 0 to 20 inclusive //foo() is inherited ¡ child: : range has to be tested afresh ¡ does child: : foo() have to be retested? foo contains the code: if (x<0) x = x/redefined() return x have to test when x<0, could divide by 0 child: : foo() may not have to be completely tested if code in foo() doesn’t depend on range(); doesn’t call it nor call any code that indirectly calls it

Which functions must be tested in a subclass? Parent class contains: foo(int x) range() - returns a number in range 1 to 10 inclusive Example Child class contains: range() - is redefined to returns a number in the range 0 to 20 inclusive //foo() is inherited ¡ child: : range has to be tested afresh ¡ does child: : foo() have to be retested? foo contains the code: if (x<0) x = x/redefined() return x have to test when x<0, could divide by 0 child: : foo() may not have to be completely tested if code in foo() doesn’t depend on range(); doesn’t call it nor call any code that indirectly calls it

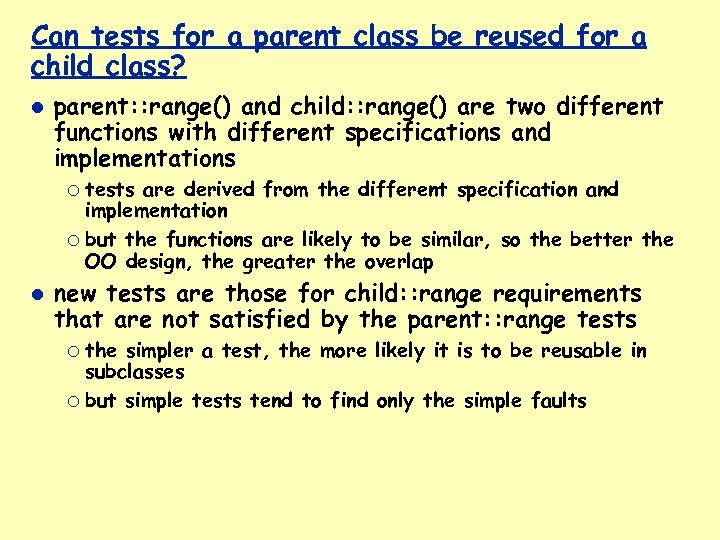

Can tests for a parent class be reused for a child class? parent: : range() and child: : range() are two different functions with different specifications and implementations ¡ tests are derived from the different specification and implementation ¡ but the functions are likely to be similar, so the better the OO design, the greater the overlap new tests are those for child: : range requirements that are not satisfied by the parent: : range tests ¡ the simpler a test, the more likely it is to be reusable in subclasses ¡ but simple tests tend to find only the simple faults

Can tests for a parent class be reused for a child class? parent: : range() and child: : range() are two different functions with different specifications and implementations ¡ tests are derived from the different specification and implementation ¡ but the functions are likely to be similar, so the better the OO design, the greater the overlap new tests are those for child: : range requirements that are not satisfied by the parent: : range tests ¡ the simpler a test, the more likely it is to be reusable in subclasses ¡ but simple tests tend to find only the simple faults

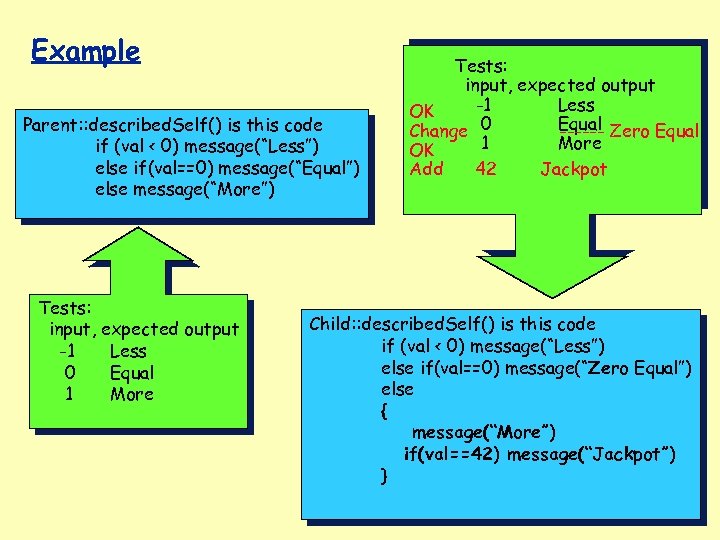

Example Parent: : described. Self() is this code if (val < 0) message(“Less”) else if(val==0) message(“Equal”) else message(“More”) Tests: input, expected output -1 Less 0 Equal 1 More Tests: input, expected output -1 Less OK Equal Zero Equal Change 0 -----1 More OK Add 42 Jackpot Child: : described. Self() is this code if (val < 0) message(“Less”) else if(val==0) message(“Zero Equal”) else { message(“More”) if(val==42) message(“Jackpot”) }

Example Parent: : described. Self() is this code if (val < 0) message(“Less”) else if(val==0) message(“Equal”) else message(“More”) Tests: input, expected output -1 Less 0 Equal 1 More Tests: input, expected output -1 Less OK Equal Zero Equal Change 0 -----1 More OK Add 42 Jackpot Child: : described. Self() is this code if (val < 0) message(“Less”) else if(val==0) message(“Zero Equal”) else { message(“More”) if(val==42) message(“Jackpot”) }

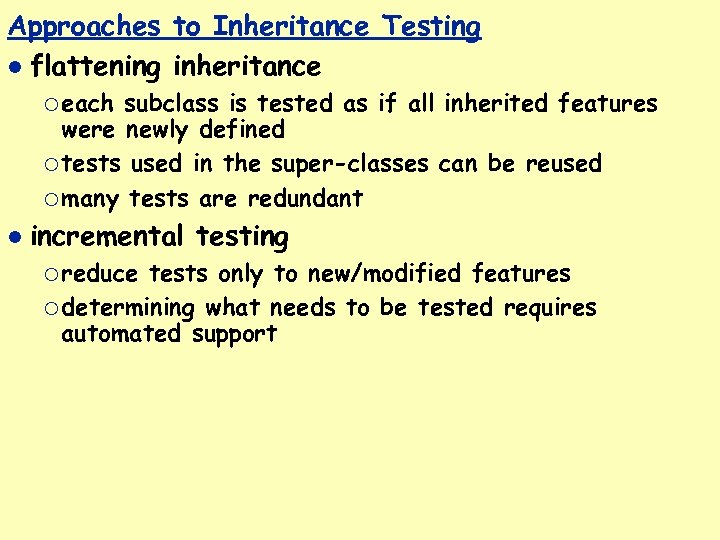

Approaches to Inheritance Testing flattening inheritance ¡ each subclass is tested as if all inherited features were newly defined ¡ tests used in the super-classes can be reused ¡ many tests are redundant incremental testing ¡ reduce tests only to new/modified features ¡ determining what needs to be tested requires automated support

Approaches to Inheritance Testing flattening inheritance ¡ each subclass is tested as if all inherited features were newly defined ¡ tests used in the super-classes can be reused ¡ many tests are redundant incremental testing ¡ reduce tests only to new/modified features ¡ determining what needs to be tested requires automated support

Polymorphism in procedural programming, procedure calls are statically bound each possible binding of a polymorphic component requires a separate set of test cases may be hard to find all such bindings may also complicate integration planning

Polymorphism in procedural programming, procedure calls are statically bound each possible binding of a polymorphic component requires a separate set of test cases may be hard to find all such bindings may also complicate integration planning

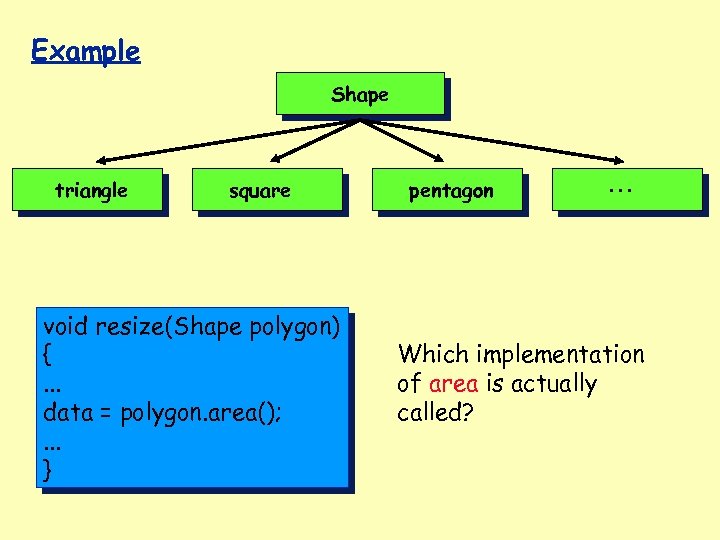

Example Shape triangle square void resize(Shape polygon) {. . . data = polygon. area(); . . . } pentagon . . . Which implementation of area is actually called?

Example Shape triangle square void resize(Shape polygon) {. . . data = polygon. area(); . . . } pentagon . . . Which implementation of area is actually called?

Approaches to the Dynamic Binding Problem reduce combinatorial explosion in the number of test cases that cover all possible combinations of polymorphic calls ¡ Use static analysis (data flow analysis) to determine possible bindings In most systems, the average number of “possible” bindings is 2

Approaches to the Dynamic Binding Problem reduce combinatorial explosion in the number of test cases that cover all possible combinations of polymorphic calls ¡ Use static analysis (data flow analysis) to determine possible bindings In most systems, the average number of “possible” bindings is 2

White-box vs. Black-box Testing of O-O object-oriented specification described functional behavior implementation describes how that is achieved Unique. Table example ¡ White box testing creates test cases that focus on how the table is implemented “Jackpot” in previous example shows need for white-box testing

White-box vs. Black-box Testing of O-O object-oriented specification described functional behavior implementation describes how that is achieved Unique. Table example ¡ White box testing creates test cases that focus on how the table is implemented “Jackpot” in previous example shows need for white-box testing

White box O-O Testing these techniques can be adapted to method testing, but are not sufficient for class testing conventional flow-graph approaches ¡ What about flow between methods? ¡ Do methods in a class have a special relationship that deserves special consideration or are interprocedural techniques adequate?

White box O-O Testing these techniques can be adapted to method testing, but are not sufficient for class testing conventional flow-graph approaches ¡ What about flow between methods? ¡ Do methods in a class have a special relationship that deserves special consideration or are interprocedural techniques adequate?

Black-box O-O Testing conventional black-box methods are useful for object-oriented systems Additional proposals ¡ utilize specification integrated with the implementation as dynamic assertions C++ assertions or Eiffel pre/post-conditions offer similar self-checking

Black-box O-O Testing conventional black-box methods are useful for object-oriented systems Additional proposals ¡ utilize specification integrated with the implementation as dynamic assertions C++ assertions or Eiffel pre/post-conditions offer similar self-checking

State-based Testing derives test cases by modeling a class as a state machine methods result in state transitions state model defines allowable transition sequences ¡ e. g. , an instance must be created before it can be updated or deleted test cases are devised to exercise each transition

State-based Testing derives test cases by modeling a class as a state machine methods result in state transitions state model defines allowable transition sequences ¡ e. g. , an instance must be created before it can be updated or deleted test cases are devised to exercise each transition

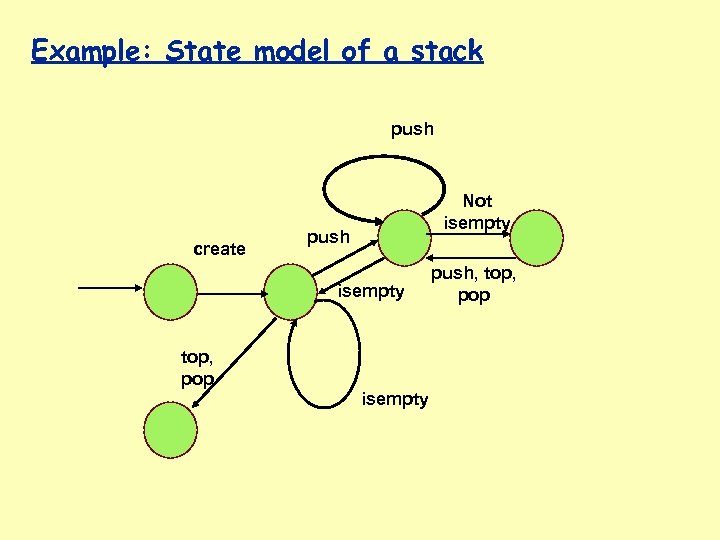

Example: State model of a stack push create Not isempty push isempty top, pop isempty push, top, pop

Example: State model of a stack push create Not isempty push isempty top, pop isempty push, top, pop

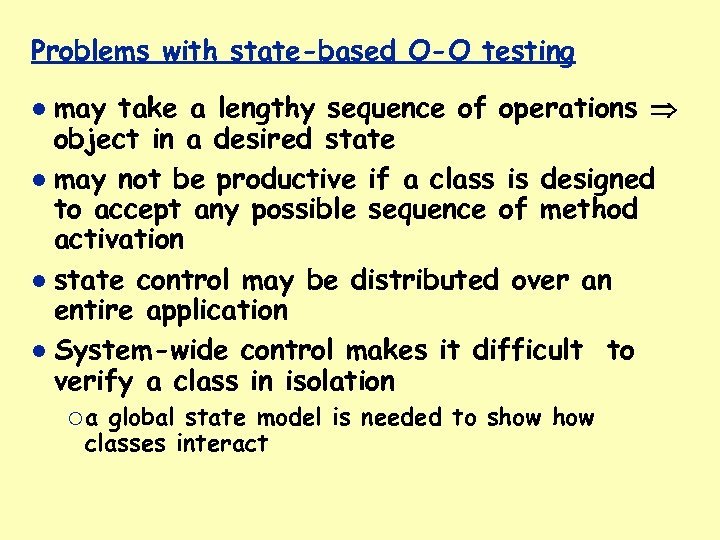

Problems with state-based O-O testing may take a lengthy sequence of operations object in a desired state may not be productive if a class is designed to accept any possible sequence of method activation state control may be distributed over an entire application System-wide control makes it difficult to verify a class in isolation ¡a global state model is needed to show classes interact

Problems with state-based O-O testing may take a lengthy sequence of operations object in a desired state may not be productive if a class is designed to accept any possible sequence of method activation state control may be distributed over an entire application System-wide control makes it difficult to verify a class in isolation ¡a global state model is needed to show classes interact

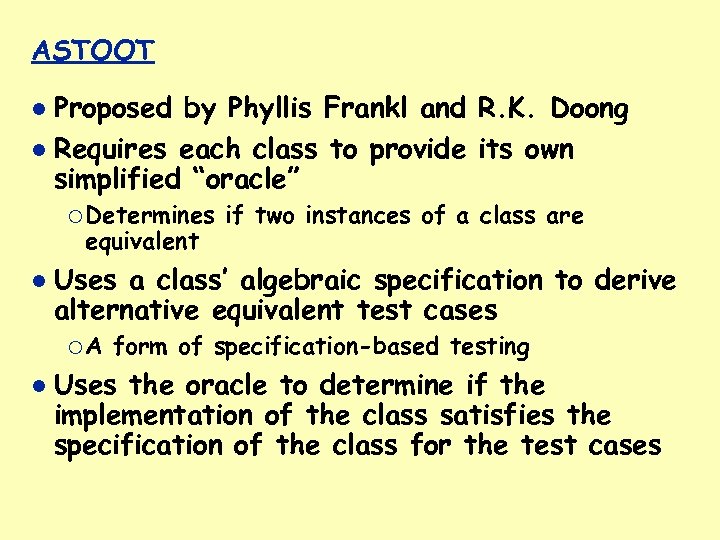

ASTOOT Proposed by Phyllis Frankl and R. K. Doong Requires each class to provide its own simplified “oracle” ¡ Determines equivalent Uses a class’ algebraic specification to derive alternative equivalent test cases ¡A if two instances of a class are form of specification-based testing Uses the oracle to determine if the implementation of the class satisfies the specification of the class for the test cases

ASTOOT Proposed by Phyllis Frankl and R. K. Doong Requires each class to provide its own simplified “oracle” ¡ Determines equivalent Uses a class’ algebraic specification to derive alternative equivalent test cases ¡A if two instances of a class are form of specification-based testing Uses the oracle to determine if the implementation of the class satisfies the specification of the class for the test cases

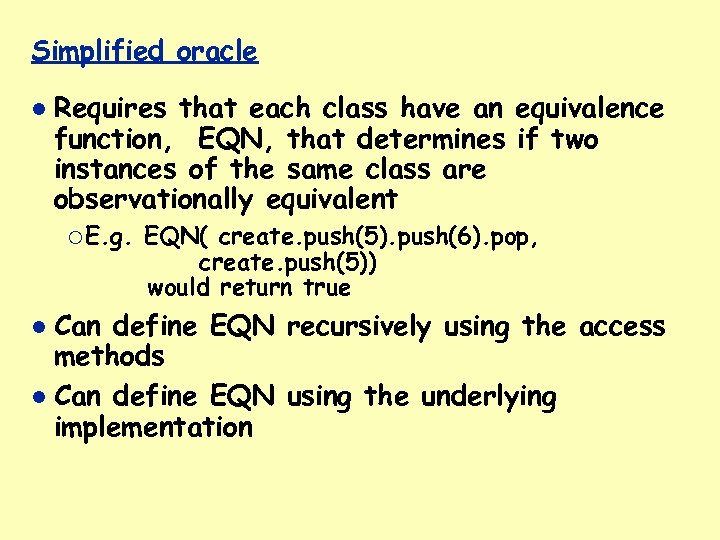

Simplified oracle Requires that each class have an equivalence function, EQN, that determines if two instances of the same class are observationally equivalent ¡ E. g. EQN( create. push(5). push(6). pop, create. push(5)) would return true Can define EQN recursively using the access methods Can define EQN using the underlying implementation

Simplified oracle Requires that each class have an equivalence function, EQN, that determines if two instances of the same class are observationally equivalent ¡ E. g. EQN( create. push(5). push(6). pop, create. push(5)) would return true Can define EQN recursively using the access methods Can define EQN using the underlying implementation

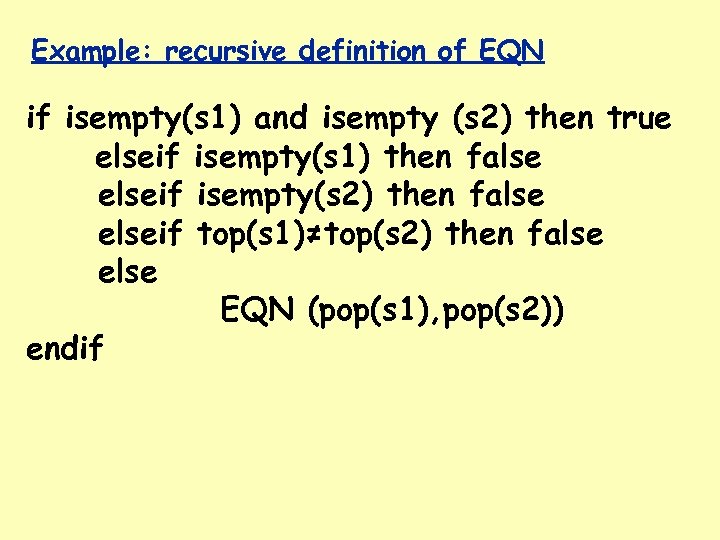

Example: recursive definition of EQN if isempty(s 1) and isempty (s 2) then true elseif isempty(s 1) then false elseif isempty(s 2) then false elseif top(s 1)≠top(s 2) then false else EQN (pop(s 1), pop(s 2)) endif

Example: recursive definition of EQN if isempty(s 1) and isempty (s 2) then true elseif isempty(s 1) then false elseif isempty(s 2) then false elseif top(s 1)≠top(s 2) then false else EQN (pop(s 1), pop(s 2)) endif

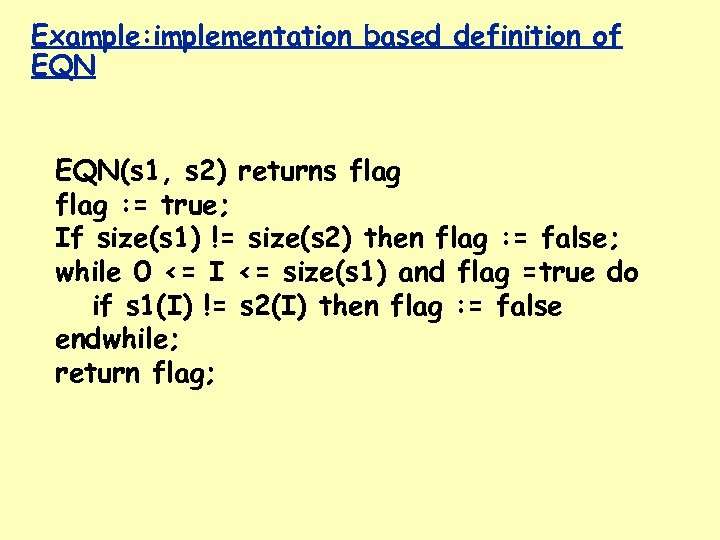

Example: implementation based definition of EQN(s 1, s 2) returns flag : = true; If size(s 1) != size(s 2) then flag : = false; while 0 <= I <= size(s 1) and flag =true do if s 1(I) != s 2(I) then flag : = false endwhile; return flag;

Example: implementation based definition of EQN(s 1, s 2) returns flag : = true; If size(s 1) != size(s 2) then flag : = false; while 0 <= I <= size(s 1) and flag =true do if s 1(I) != s 2(I) then flag : = false endwhile; return flag;

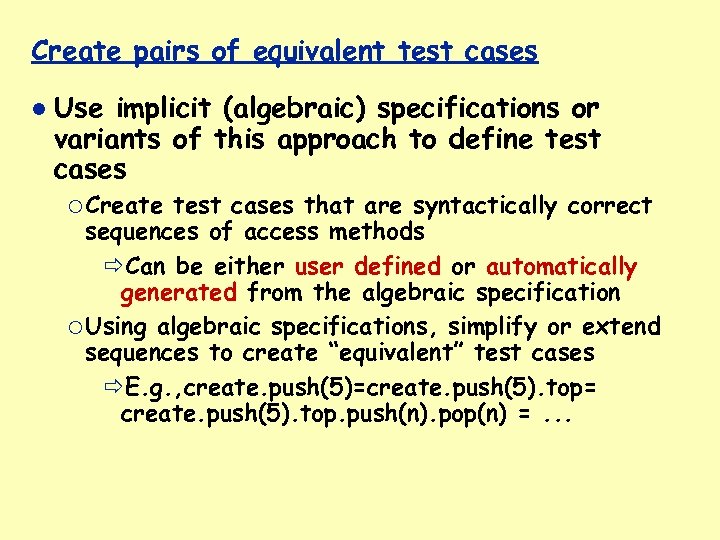

Create pairs of equivalent test cases Use implicit (algebraic) specifications or variants of this approach to define test cases ¡ Create test cases that are syntactically correct sequences of access methods Can be either user defined or automatically generated from the algebraic specification ¡ Using algebraic specifications, simplify or extend sequences to create “equivalent” test cases E. g. , create. push(5)=create. push(5). top= create. push(5). top. push(n). pop(n) =. . .

Create pairs of equivalent test cases Use implicit (algebraic) specifications or variants of this approach to define test cases ¡ Create test cases that are syntactically correct sequences of access methods Can be either user defined or automatically generated from the algebraic specification ¡ Using algebraic specifications, simplify or extend sequences to create “equivalent” test cases E. g. , create. push(5)=create. push(5). top= create. push(5). top. push(n). pop(n) =. . .