Teaching speaking.pptx

- Количество слайдов: 55

Teaching speaking: communicative approach

Teaching speaking: communicative approach

Speaking mechanisms Research (and the common sense) suggests that there is a lot more to speaking than the ability to form grammatically correct sentences and then to pronounce them. It typically takes place in real time, with little time for detailed planning. What mechanisms allow us to speak? Spoken fluency requires the capacity to arrange a store of memorised lexical chunks.

Speaking mechanisms Research (and the common sense) suggests that there is a lot more to speaking than the ability to form grammatically correct sentences and then to pronounce them. It typically takes place in real time, with little time for detailed planning. What mechanisms allow us to speak? Spoken fluency requires the capacity to arrange a store of memorised lexical chunks.

Moreover, since the grammar of spoken language differs from the grammar of written language, the study of written grammar may not be the most efficient preparation for speaking. Speaking is a skill and as such it needs to be developed independently.

Moreover, since the grammar of spoken language differs from the grammar of written language, the study of written grammar may not be the most efficient preparation for speaking. Speaking is a skill and as such it needs to be developed independently.

In order to achieve any degree of fluency, some degree of automaticity is necessary. Automaticity allows speakers to focus their attention on the aspect of the speaking task that immediately requires it, whether t is planning or articulation. Automaticity is partly achieved through the use of prefabricated chunks.

In order to achieve any degree of fluency, some degree of automaticity is necessary. Automaticity allows speakers to focus their attention on the aspect of the speaking task that immediately requires it, whether t is planning or articulation. Automaticity is partly achieved through the use of prefabricated chunks.

In this sense speaking is like any other skill such as driving or playing a musical instrument: the more practice you get, the more likely it is you will be able to chunk small units into larger ones.

In this sense speaking is like any other skill such as driving or playing a musical instrument: the more practice you get, the more likely it is you will be able to chunk small units into larger ones.

Speaking skills require more than just that: Turn taking: speakers should take turns to hold the floor The skills by means of which it becomes possible are as follows: - recognising the appropriate moment to get a turn - signalling the fact that you want to speak - holding the floor while you have your turn - recognising when other speakers are signalling their wish to speak - yielding the turn - signalling the fact that you are listening

Speaking skills require more than just that: Turn taking: speakers should take turns to hold the floor The skills by means of which it becomes possible are as follows: - recognising the appropriate moment to get a turn - signalling the fact that you want to speak - holding the floor while you have your turn - recognising when other speakers are signalling their wish to speak - yielding the turn - signalling the fact that you are listening

Different types of speech events Service encounters, such as buying goods, getting information, or requesting a service, are transactional speech events that follow a predictable script. Typically, the exchange begins with a greeting, followed by an offer, followed by a request and so on: - Good morning - What would you like? - A dozen eggs, please. - Anything else?

Different types of speech events Service encounters, such as buying goods, getting information, or requesting a service, are transactional speech events that follow a predictable script. Typically, the exchange begins with a greeting, followed by an offer, followed by a request and so on: - Good morning - What would you like? - A dozen eggs, please. - Anything else?

An important factor that determines the character of a speech event is whether it is interactive or non-interactive. A casual conversation between friends is a typical example of an interactive speech event. Monologues such as a television journalist’s live report or a university lecture are non-interactive.

An important factor that determines the character of a speech event is whether it is interactive or non-interactive. A casual conversation between friends is a typical example of an interactive speech event. Monologues such as a television journalist’s live report or a university lecture are non-interactive.

A distinctions is also to be made between planned and unplanned speech. Certain speech genres such as public speeches and business presentations are typically planned, to the point that they might be completely scripted in advance. A phone conversation to ask about timetable information, while following a predictable sequence, is normally not planned in advance.

A distinctions is also to be made between planned and unplanned speech. Certain speech genres such as public speeches and business presentations are typically planned, to the point that they might be completely scripted in advance. A phone conversation to ask about timetable information, while following a predictable sequence, is normally not planned in advance.

Discourse markers Researchers of transcribed speech have demonstrated that the 50 most frequent words in spoken English make up nearly 50% of all talk. The word well occurs about nine times more often in speech than in writing!!! Well is an example of a discourse marker which is very common in interaction. Spoken language also has a high proportion of words and expressions that express the speaker’s attitude to what is being said: probably, maybe, really, actually etc.

Discourse markers Researchers of transcribed speech have demonstrated that the 50 most frequent words in spoken English make up nearly 50% of all talk. The word well occurs about nine times more often in speech than in writing!!! Well is an example of a discourse marker which is very common in interaction. Spoken language also has a high proportion of words and expressions that express the speaker’s attitude to what is being said: probably, maybe, really, actually etc.

Chunks Speakers achieve fluency through the use of prefabricated chunks: These are sequences of speech that are not assembled word by word but have been preassembled through repeated use and are now retrievable as single units. Chunks are also known as lexical phrases, holophrases, formulaic language and prefabs. Of the different types of chunks the following are the most common: collocations: densely populated, set the table phrasal verbs: run out of, go on about idioms, catchphrases and sayings: make ends meet, as cool as a cucumber sentence frames: what really puzzles me is… social formulas: have a nice day, mind your head discourse markers: if you ask me, by the way

Chunks Speakers achieve fluency through the use of prefabricated chunks: These are sequences of speech that are not assembled word by word but have been preassembled through repeated use and are now retrievable as single units. Chunks are also known as lexical phrases, holophrases, formulaic language and prefabs. Of the different types of chunks the following are the most common: collocations: densely populated, set the table phrasal verbs: run out of, go on about idioms, catchphrases and sayings: make ends meet, as cool as a cucumber sentence frames: what really puzzles me is… social formulas: have a nice day, mind your head discourse markers: if you ask me, by the way

Vocabulary Native speakers employ over 2, 500 words to cover 95% of their communicative needs. Learners can probably get by half that number, especially for the purposes of casual conversation. Even the top 200 most common words will provide the learner with a lot of conversational mileage, since they include:

Vocabulary Native speakers employ over 2, 500 words to cover 95% of their communicative needs. Learners can probably get by half that number, especially for the purposes of casual conversation. Even the top 200 most common words will provide the learner with a lot of conversational mileage, since they include:

How to teach speaking?

How to teach speaking?

Using listening as a tool for teaching speaking Materials: -Authentic and non-authentic recordings - Scripted recording incorporated features of natural speech - Soap operas, documentaries, extracts from the films, radio and TV programmes, game shows

Using listening as a tool for teaching speaking Materials: -Authentic and non-authentic recordings - Scripted recording incorporated features of natural speech - Soap operas, documentaries, extracts from the films, radio and TV programmes, game shows

The procedure - Activating background knowledge It may help to establish the topic or the content of the event, brainstorming vocabulary, the teacher can introduce new items - Checking gist Playing the extract and asking general gist questions like: Who is talking to whom about what and why? Repeated listening may be necessary - Checking details The learners may be set further tasks e. g. a grid to fill, a mutliple choice questions to answer

The procedure - Activating background knowledge It may help to establish the topic or the content of the event, brainstorming vocabulary, the teacher can introduce new items - Checking gist Playing the extract and asking general gist questions like: Who is talking to whom about what and why? Repeated listening may be necessary - Checking details The learners may be set further tasks e. g. a grid to fill, a mutliple choice questions to answer

- Listen and read stage hand out the transcript, replay the recording while the students listen silently - resolving doubts the students are given the opportunity to ask about any doubts or problems they have about the text - focus on language features filling in the gaps exercises, spot the difference exercises - Focus on speech acts, focus on discourse markers, focus on sociocultiral rules, on features of spoken grammar, on vocabulary, on the use of lexical chunks, stress and intonation

- Listen and read stage hand out the transcript, replay the recording while the students listen silently - resolving doubts the students are given the opportunity to ask about any doubts or problems they have about the text - focus on language features filling in the gaps exercises, spot the difference exercises - Focus on speech acts, focus on discourse markers, focus on sociocultiral rules, on features of spoken grammar, on vocabulary, on the use of lexical chunks, stress and intonation

Live listening – listening to the teacher or guest speaker The main advantage is a possibility to adjust the speech and interactive character The teacher introduced the topic e. g. of his brother by showing a family photograph. Then he told the story using natural but uncomplicated language and occasionally stopped to check understanding (e. g. to explain a term). During the story he used a number of time and sequencing expressions (eventually, all of a sudden, to cut a long story short etc. ) At the end of the story the students are invited to ask questions.

Live listening – listening to the teacher or guest speaker The main advantage is a possibility to adjust the speech and interactive character The teacher introduced the topic e. g. of his brother by showing a family photograph. Then he told the story using natural but uncomplicated language and occasionally stopped to check understanding (e. g. to explain a term). During the story he used a number of time and sequencing expressions (eventually, all of a sudden, to cut a long story short etc. ) At the end of the story the students are invited to ask questions.

Noticing-the-gap-activities The teacher sets up the context for a speech event – e. g. two people fixing a date to meet or someone returning a faulty item to a shop. 1) Learners are paired off and attempt to perform a task, using the linguistic means they have. 2) Then they listen to the recording – or watch a video – or two experts performing the same task.

Noticing-the-gap-activities The teacher sets up the context for a speech event – e. g. two people fixing a date to meet or someone returning a faulty item to a shop. 1) Learners are paired off and attempt to perform a task, using the linguistic means they have. 2) Then they listen to the recording – or watch a video – or two experts performing the same task.

Recordings of skilled speakers performing the task are played -Introduce the speakers on the cassette; - Make sure the students realise the speakers are doing a similar task to the one they will do or have done; -Make sure they know that you don’t expect them to understand everything. Tell them it might sound difficult to start with, but you will play several times.

Recordings of skilled speakers performing the task are played -Introduce the speakers on the cassette; - Make sure the students realise the speakers are doing a similar task to the one they will do or have done; -Make sure they know that you don’t expect them to understand everything. Tell them it might sound difficult to start with, but you will play several times.

Having listened to the task being performed learners should then have the chance of studying the transcript of the recording. They can be asked to note any features such as useful expressions that they would like to incorporate into their performance.

Having listened to the task being performed learners should then have the chance of studying the transcript of the recording. They can be asked to note any features such as useful expressions that they would like to incorporate into their performance.

Variant of the notice-the-gap activity: We allow the learner to perform the task in the L 1 and then reformulate it in the target language allowing the student to see the difference.

Variant of the notice-the-gap activity: We allow the learner to perform the task in the L 1 and then reformulate it in the target language allowing the student to see the difference.

Minuting the lesson The learners can be asked to reflect on the lesson and recall anything that they consciously noted. The students are asked to write down a personal note in the form of “something someone said that surprised me” or “a word or expression I particularly liked” tec.

Minuting the lesson The learners can be asked to reflect on the lesson and recall anything that they consciously noted. The students are asked to write down a personal note in the form of “something someone said that surprised me” or “a word or expression I particularly liked” tec.

Controlled practice Drilling The notion of practised control need not rule out the value of some mechanical and repetitive activities of the type traditionally associated with drilling.

Controlled practice Drilling The notion of practised control need not rule out the value of some mechanical and repetitive activities of the type traditionally associated with drilling.

Drilling – imitating and repeating words, phrases, and even whole utterances After the students have listened to a taped dialogue they may be asked to repeat some isolated specific phrases or utterances. If all the dialogue were drilled the benefit would be lost! Drilling may help in the storing and retrieving of the chunks and catchphrases etc.

Drilling – imitating and repeating words, phrases, and even whole utterances After the students have listened to a taped dialogue they may be asked to repeat some isolated specific phrases or utterances. If all the dialogue were drilled the benefit would be lost! Drilling may help in the storing and retrieving of the chunks and catchphrases etc.

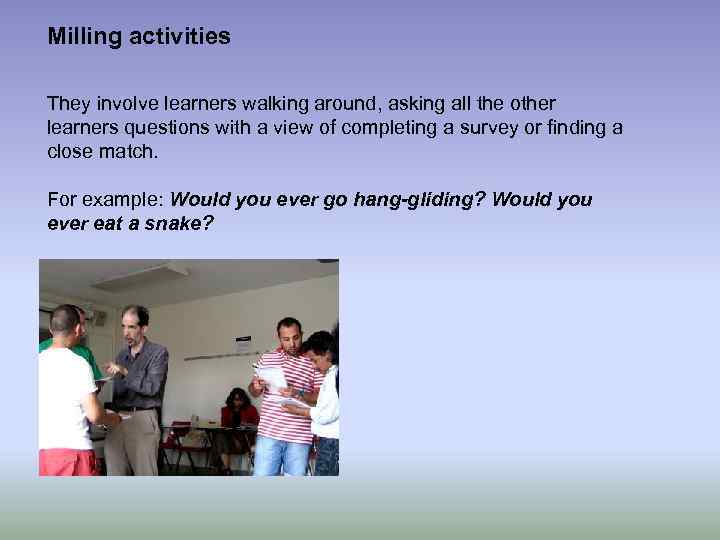

Milling activities They involve learners walking around, asking all the other learners questions with a view of completing a survey or finding a close match. For example: Would you ever go hang-gliding? Would you ever eat a snake?

Milling activities They involve learners walking around, asking all the other learners questions with a view of completing a survey or finding a close match. For example: Would you ever go hang-gliding? Would you ever eat a snake?

It will involve the repeated asking of the question but in a context that requires some re-allocating some attention away from grammatical processing and on to some mental and physical tasks. Then the students report to the class the results of the milling activity.

It will involve the repeated asking of the question but in a context that requires some re-allocating some attention away from grammatical processing and on to some mental and physical tasks. Then the students report to the class the results of the milling activity.

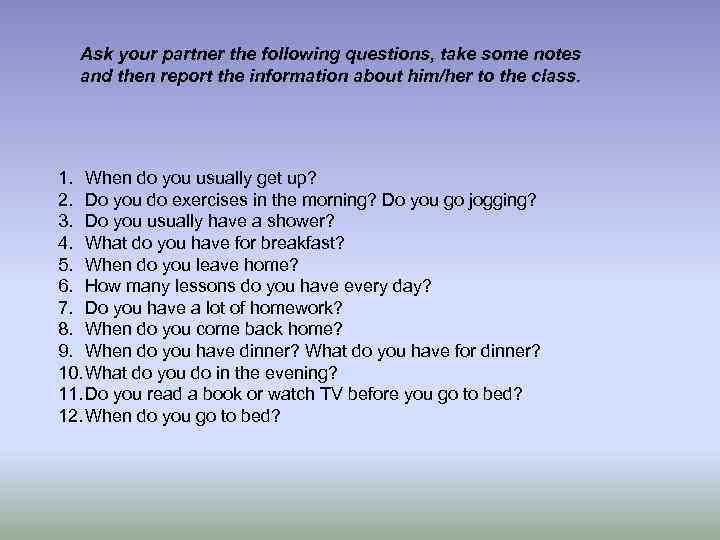

Ask your partner the following questions, take some notes and then report the information about him/her to the class. 1. When do you usually get up? 2. Do you do exercises in the morning? Do you go jogging? 3. Do you usually have a shower? 4. What do you have for breakfast? 5. When do you leave home? 6. How many lessons do you have every day? 7. Do you have a lot of homework? 8. When do you come back home? 9. When do you have dinner? What do you have for dinner? 10. What do you do in the evening? 11. Do you read a book or watch TV before you go to bed? 12. When do you go to bed?

Ask your partner the following questions, take some notes and then report the information about him/her to the class. 1. When do you usually get up? 2. Do you do exercises in the morning? Do you go jogging? 3. Do you usually have a shower? 4. What do you have for breakfast? 5. When do you leave home? 6. How many lessons do you have every day? 7. Do you have a lot of homework? 8. When do you come back home? 9. When do you have dinner? What do you have for dinner? 10. What do you do in the evening? 11. Do you read a book or watch TV before you go to bed? 12. When do you go to bed?

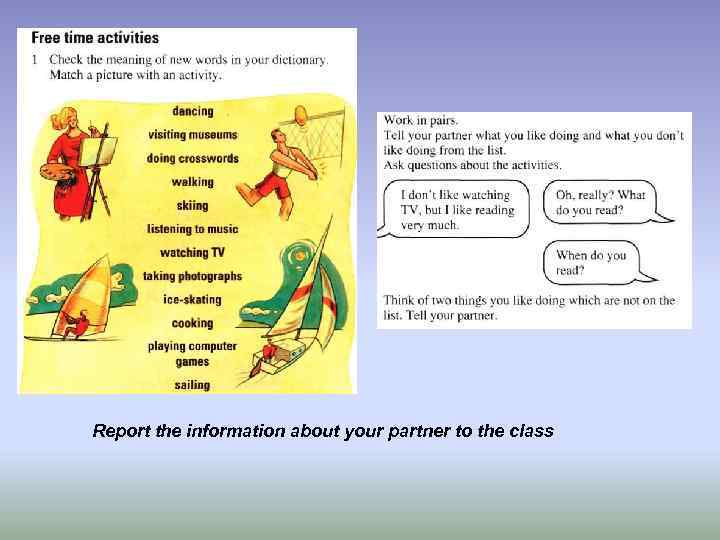

Report the information about your partner to the class

Report the information about your partner to the class

Writing activities Paper conversations Learners have the conversations with their classmates but instead of speaking, they write the conversation on a shared sheet of paper. While the students take part in this small talk, the teacher can make improvements more easily than when students are actually speaking.

Writing activities Paper conversations Learners have the conversations with their classmates but instead of speaking, they write the conversation on a shared sheet of paper. While the students take part in this small talk, the teacher can make improvements more easily than when students are actually speaking.

Rewriting dialogues Asking learners to rewrite, improve or modify written dialogues. -Changing the register -Making it more interactive (incorporating comments) -Including positive appraisal language -Adding pause fillers and false starts -Extend the length of the turns -Incorporating discourse markers: so, well, right, oh -Incorporating ellipses: What’s your name? – Juan -Making the talk more idiomatic -Making the talk less direct, using vague language (sort of, kind of)

Rewriting dialogues Asking learners to rewrite, improve or modify written dialogues. -Changing the register -Making it more interactive (incorporating comments) -Including positive appraisal language -Adding pause fillers and false starts -Extend the length of the turns -Incorporating discourse markers: so, well, right, oh -Incorporating ellipses: What’s your name? – Juan -Making the talk more idiomatic -Making the talk less direct, using vague language (sort of, kind of)

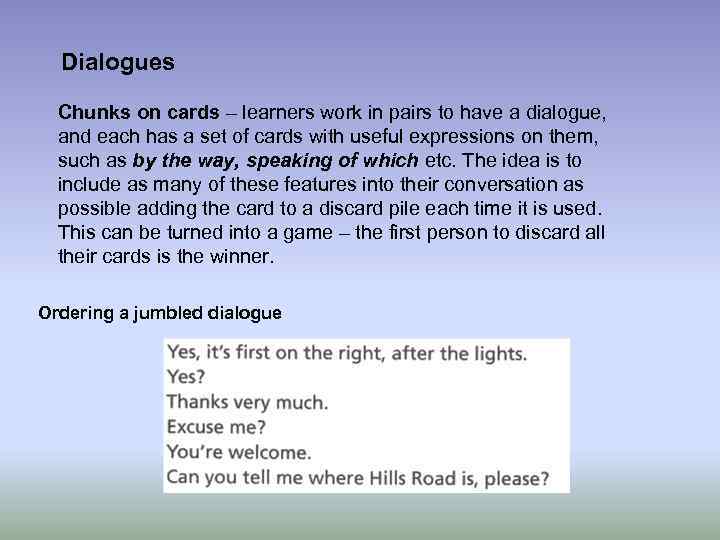

Dialogues Chunks on cards – learners work in pairs to have a dialogue, and each has a set of cards with useful expressions on them, such as by the way, speaking of which etc. The idea is to include as many of these features into their conversation as possible adding the card to a discard pile each time it is used. This can be turned into a game – the first person to discard all their cards is the winner. Ordering a jumbled dialogue

Dialogues Chunks on cards – learners work in pairs to have a dialogue, and each has a set of cards with useful expressions on them, such as by the way, speaking of which etc. The idea is to include as many of these features into their conversation as possible adding the card to a discard pile each time it is used. This can be turned into a game – the first person to discard all their cards is the winner. Ordering a jumbled dialogue

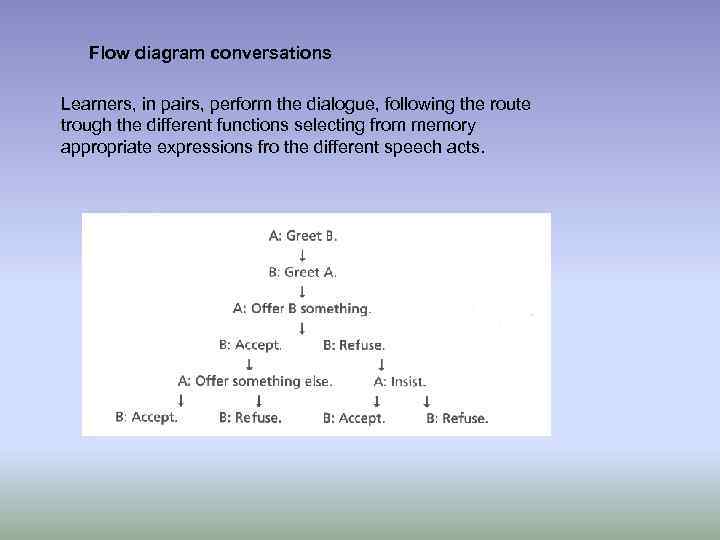

Flow diagram conversations Learners, in pairs, perform the dialogue, following the route trough the different functions selecting from memory appropriate expressions fro the different speech acts.

Flow diagram conversations Learners, in pairs, perform the dialogue, following the route trough the different functions selecting from memory appropriate expressions fro the different speech acts.

Conversation tennis A: What did you do yesterday? B: I worked all day. Then I went to the gym. A: Did you? B: What did you do? Set the learners the task of having a conversation in which they try to “bat” the conversational ball back and forth as much as possible without letting it drop. It is a good warm-up exercise at the beginning of every lesson.

Conversation tennis A: What did you do yesterday? B: I worked all day. Then I went to the gym. A: Did you? B: What did you do? Set the learners the task of having a conversation in which they try to “bat” the conversational ball back and forth as much as possible without letting it drop. It is a good warm-up exercise at the beginning of every lesson.

Disappearing dialogue The text of the dialogue is written on the board, learners practice reading it aloud in pairs and then the teacher starts removing sections of it. First these could be single words, then the whole lines could be removed. A. What did you do yesterday? B: I worked all day. Then I went to the gym. A: Did you? B: What did you do?

Disappearing dialogue The text of the dialogue is written on the board, learners practice reading it aloud in pairs and then the teacher starts removing sections of it. First these could be single words, then the whole lines could be removed. A. What did you do yesterday? B: I worked all day. Then I went to the gym. A: Did you? B: What did you do?

Dialogue building The dialogue is not presented to the learners but elicited from them line by line. 1. Establishing the situation, the context and the purpose (at the hotel) 2. The teacher starts to elicit the conversation. The ideas for the 1 -st, 2 -d and 3 -d line of the conversation. 3. The complete dialogue is built and drilled.

Dialogue building The dialogue is not presented to the learners but elicited from them line by line. 1. Establishing the situation, the context and the purpose (at the hotel) 2. The teacher starts to elicit the conversation. The ideas for the 1 -st, 2 -d and 3 -d line of the conversation. 3. The complete dialogue is built and drilled.

Communicative activities §The motivation of the activity is to achieve some outcome using language §The activity takes place in real time §Achieving the outcome requires the participants to interact – listen and speak §Because of the spontaneous interaction the outcome is not predictable §There is no restriction to the language used

Communicative activities §The motivation of the activity is to achieve some outcome using language §The activity takes place in real time §Achieving the outcome requires the participants to interact – listen and speak §Because of the spontaneous interaction the outcome is not predictable §There is no restriction to the language used

1. Jigsaw activities 2. Surveys (more elaborate versions of milling activities) 3. Blocking games – bringing in the element of unpredictability into a standard conversation 4. Guessing games 5. “The Onion” - the chairs are arranged in circles – the inner circle is facing the outer circle, the students of the outer circle move round one chair so that they have a new partner 6. Reconstructing a story behind a headline. 7. 4 -3 -2 activity: the students are allowed less time with each attempt to do a task (to retell a story) 8. Role-plays 9. Dramatising activities 10. Discussions and debates

1. Jigsaw activities 2. Surveys (more elaborate versions of milling activities) 3. Blocking games – bringing in the element of unpredictability into a standard conversation 4. Guessing games 5. “The Onion” - the chairs are arranged in circles – the inner circle is facing the outer circle, the students of the outer circle move round one chair so that they have a new partner 6. Reconstructing a story behind a headline. 7. 4 -3 -2 activity: the students are allowed less time with each attempt to do a task (to retell a story) 8. Role-plays 9. Dramatising activities 10. Discussions and debates

Story-telling activities Guess the lie: Learners tell each other three short personal anecdotes, two of which are true in every particular, and the third of which is totally untrue (but plausible). The listeners have to guess the lie – and give reasons for their guesses. They can be allowed to ask a limited number of questions after the story. Chain story: in groups the learners take turns to tell a story, each one taking over from, and building on, the contribution of their classmates, at a given signal from a teacher.

Story-telling activities Guess the lie: Learners tell each other three short personal anecdotes, two of which are true in every particular, and the third of which is totally untrue (but plausible). The listeners have to guess the lie – and give reasons for their guesses. They can be allowed to ask a limited number of questions after the story. Chain story: in groups the learners take turns to tell a story, each one taking over from, and building on, the contribution of their classmates, at a given signal from a teacher.

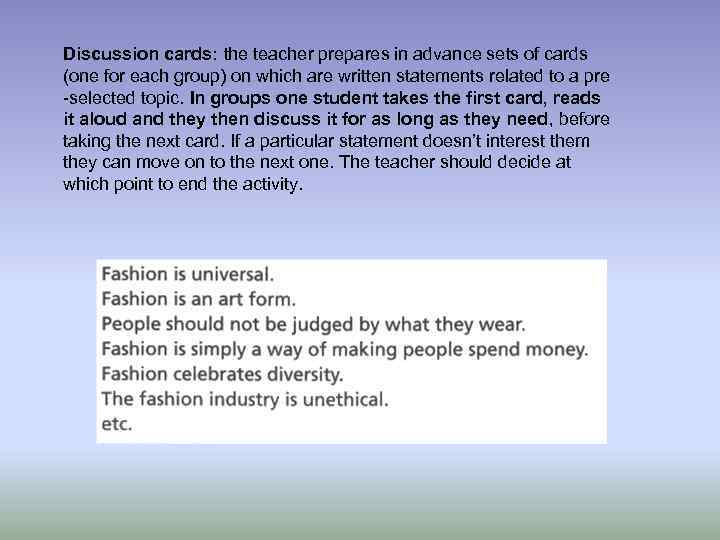

Discussion cards: the teacher prepares in advance sets of cards (one for each group) on which are written statements related to a pre -selected topic. In groups one student takes the first card, reads it aloud and they then discuss it for as long as they need, before taking the next card. If a particular statement doesn’t interest them they can move on to the next one. The teacher should decide at which point to end the activity.

Discussion cards: the teacher prepares in advance sets of cards (one for each group) on which are written statements related to a pre -selected topic. In groups one student takes the first card, reads it aloud and they then discuss it for as long as they need, before taking the next card. If a particular statement doesn’t interest them they can move on to the next one. The teacher should decide at which point to end the activity.

Guessing games In the games such as “What’s my line? ”one learner thinks of a job and the others have to ask yes/no questions to guess what it is. It provides ideal conditions fro automating knowledge (Do you work indoors or outdoors? Do you work with your hands? Do you wear a uniform? ). The game takes place in real time, so there is an element of spontaneity and the focus is on the outcome (not the language being used to get there). Other games: What sort of animal am I? Who am I? (One player thinks of a famous person, alive or dead) The basic format of this game can be applied to almost any topic.

Guessing games In the games such as “What’s my line? ”one learner thinks of a job and the others have to ask yes/no questions to guess what it is. It provides ideal conditions fro automating knowledge (Do you work indoors or outdoors? Do you work with your hands? Do you wear a uniform? ). The game takes place in real time, so there is an element of spontaneity and the focus is on the outcome (not the language being used to get there). Other games: What sort of animal am I? Who am I? (One player thinks of a famous person, alive or dead) The basic format of this game can be applied to almost any topic.

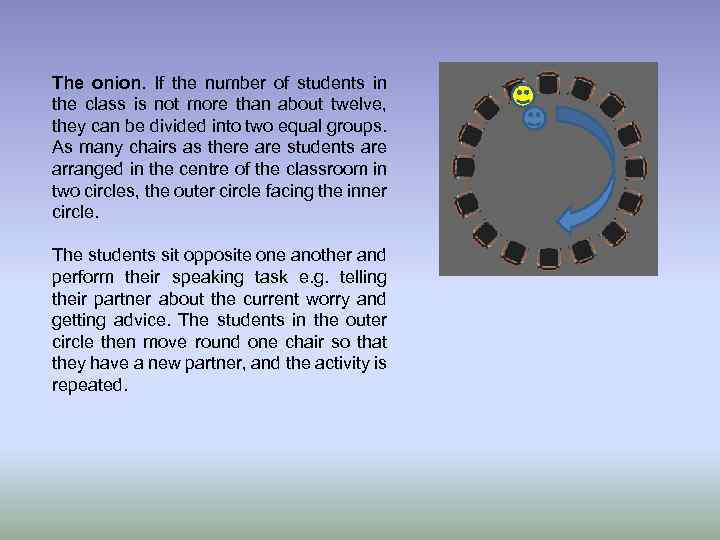

The onion. If the number of students in the class is not more than about twelve, they can be divided into two equal groups. As many chairs as there are students are arranged in the centre of the classroom in two circles, the outer circle facing the inner circle. The students sit opposite one another and perform their speaking task e. g. telling their partner about the current worry and getting advice. The students in the outer circle then move round one chair so that they have a new partner, and the activity is repeated.

The onion. If the number of students in the class is not more than about twelve, they can be divided into two equal groups. As many chairs as there are students are arranged in the centre of the classroom in two circles, the outer circle facing the inner circle. The students sit opposite one another and perform their speaking task e. g. telling their partner about the current worry and getting advice. The students in the outer circle then move round one chair so that they have a new partner, and the activity is repeated.

4 -3 -2 – in this pairwork format, the objective is to retell a story or monologue within a time limit that decreases at each retelling, thereby encouraging greater automaticity. Students are paired and take it in turns to do a monologic speaking task, e. g. recounting a story or explaining the process, based on picture prompts, or summarising the text they have just read. For the first telling the speaker is allowed four minutes, the second time they have to achieve the same degree of detail only in three minutes etc.

4 -3 -2 – in this pairwork format, the objective is to retell a story or monologue within a time limit that decreases at each retelling, thereby encouraging greater automaticity. Students are paired and take it in turns to do a monologic speaking task, e. g. recounting a story or explaining the process, based on picture prompts, or summarising the text they have just read. For the first telling the speaker is allowed four minutes, the second time they have to achieve the same degree of detail only in three minutes etc.

Presentations and talks Show-and- tell. Asking students to talk and answer questions about an object or image of special significance to them. The talk need to be more than 2 or 3 minutes and should be unscripted. The use of notes could be allowed. Did you read about…? It can be done in small groups rather than the whole class. The stimulus is “something I read in the paper or heard on the news’ rather than an object. The most interesting story in each group can then be told to the class as a whole.

Presentations and talks Show-and- tell. Asking students to talk and answer questions about an object or image of special significance to them. The talk need to be more than 2 or 3 minutes and should be unscripted. The use of notes could be allowed. Did you read about…? It can be done in small groups rather than the whole class. The stimulus is “something I read in the paper or heard on the news’ rather than an object. The most interesting story in each group can then be told to the class as a whole.

Academic presentations – students studying English for academic purposes are likely to need preparation in giving academic presentations or conference papers. It may be helpful to discuss the formal features of such genres as well as identifying specific language exponents associated with each stage. These features could be displayed as a poster in the classroom.

Academic presentations – students studying English for academic purposes are likely to need preparation in giving academic presentations or conference papers. It may be helpful to discuss the formal features of such genres as well as identifying specific language exponents associated with each stage. These features could be displayed as a poster in the classroom.

Drama, roleplay and simulation Speaking activities involving a drama element, in which learners take a leap out of the confines of the classroom, provide a useful springboard for real-life language use. Situations that learners are likely to encounter when using English in the real world can be simulated, and a greater range of registers can be practiced than are normally available in classroom talk.

Drama, roleplay and simulation Speaking activities involving a drama element, in which learners take a leap out of the confines of the classroom, provide a useful springboard for real-life language use. Situations that learners are likely to encounter when using English in the real world can be simulated, and a greater range of registers can be practiced than are normally available in classroom talk.

A and B. You are a married couple. B is from another country. Immigration officers are going to interview you and you have five minutes to prepare for the interview. Work together to make sure you give the same information about: - how long B has been in the country - how long you have known each other - where you met - your wedding - your jobs - what do you do in your free time C and D. You are immigration officers. A and B are married. B is from another country and you don’t think it’s a real marriage. You are going to interview the couple and you have 5 minutes to prepare for the interview. Work together to prepare questions to ask them. - how long B has been in the country - how long have they known each other - where they met - their wedding - their jobs - what they do in their free time

A and B. You are a married couple. B is from another country. Immigration officers are going to interview you and you have five minutes to prepare for the interview. Work together to make sure you give the same information about: - how long B has been in the country - how long you have known each other - where you met - your wedding - your jobs - what do you do in your free time C and D. You are immigration officers. A and B are married. B is from another country and you don’t think it’s a real marriage. You are going to interview the couple and you have 5 minutes to prepare for the interview. Work together to prepare questions to ask them. - how long B has been in the country - how long have they known each other - where they met - their wedding - their jobs - what they do in their free time

The Soap – learners plan, rehearse and perform (film) an episode from a soap opera. The soap opera could be based on a well-known local version. Students write detailed profiles of the characters they are going to play and then the story is built up through a series of improvisations and scripted. Work is done on pronunciation as well as using drama techniques to improve performance.

The Soap – learners plan, rehearse and perform (film) an episode from a soap opera. The soap opera could be based on a well-known local version. Students write detailed profiles of the characters they are going to play and then the story is built up through a series of improvisations and scripted. Work is done on pronunciation as well as using drama techniques to improve performance.

Warm-up discussions – when introducing a new topic or preparing learners to read or listen to the text it is common to set a few questions fro pair or group discussions, followed by a report back to the class. Panel discussions – follow the format of a television debate in which people representing various shades of opinion on a topic argue the case usually under the guidance of a chairperson. One way of organizing this is to let students first work in pairs to prepare their arguments, then one of each pair takes their place on the panel, while the others form the audience asking questions

Warm-up discussions – when introducing a new topic or preparing learners to read or listen to the text it is common to set a few questions fro pair or group discussions, followed by a report back to the class. Panel discussions – follow the format of a television debate in which people representing various shades of opinion on a topic argue the case usually under the guidance of a chairperson. One way of organizing this is to let students first work in pairs to prepare their arguments, then one of each pair takes their place on the panel, while the others form the audience asking questions

Audio and video conferencing These are virtual meetings, in which two or more people communicate via a live audio or video link over the Internet. They require microphone, speakers and special software, web camera. Both audio and video conferencing have been used to good effect to bring learners from different parts of the world together to collaborate on tasks and simulations.

Audio and video conferencing These are virtual meetings, in which two or more people communicate via a live audio or video link over the Internet. They require microphone, speakers and special software, web camera. Both audio and video conferencing have been used to good effect to bring learners from different parts of the world together to collaborate on tasks and simulations.

Jigsaw activity Students select one of several journal articles from an approved list, read the article, write a summary, and prepare a short oral presentation. In class students are assigned to small groups with students from each of the other articles. Students then take turns in presenting the main points of their article to the other students in their group.

Jigsaw activity Students select one of several journal articles from an approved list, read the article, write a summary, and prepare a short oral presentation. In class students are assigned to small groups with students from each of the other articles. Students then take turns in presenting the main points of their article to the other students in their group.