efc243fb9fc3d40f4875ec7d3f63ea60.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 58

Teaching Individual Words: One Size Does Not Fit All! Michael F. Graves University of Minnesota, Emeritus mgraves@umn. edu m lishmentarianis antidisestab IRA Annual Convention Atlanta, Georgia ungo May, 2008 us kitty unre al apath y timid t u rel tan c F hum nnoy a RANT LAG fi e d the cid undi gni a pla sco wl mommy

Teaching Individual Words: One Size Does Not Fit All! Michael F. Graves University of Minnesota, Emeritus mgraves@umn. edu m lishmentarianis antidisestab IRA Annual Convention Atlanta, Georgia ungo May, 2008 us kitty unre al apath y timid t u rel tan c F hum nnoy a RANT LAG fi e d the cid undi gni a pla sco wl mommy

bonnie_graves@msn. com Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

bonnie_graves@msn. com Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words One Size Does Not Fit All Michael F. Graves Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words One Size Does Not Fit All Michael F. Graves Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

The Importance of Vocabulary knowledge is one of the best indicators of verbal ability. Vocabulary knowledge in kindergarten and first grade is a significant predictor or reading comprehension in the middle and secondary grades. Vocabulary difficulty strongly influences the readability of text. In fact, vocabulary is far and away the most significant factor influencing text difficulty. Teaching vocabulary can improve reading comprehension for both native English speakers and English learners. (Graves, 2006, 2007) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

The Importance of Vocabulary knowledge is one of the best indicators of verbal ability. Vocabulary knowledge in kindergarten and first grade is a significant predictor or reading comprehension in the middle and secondary grades. Vocabulary difficulty strongly influences the readability of text. In fact, vocabulary is far and away the most significant factor influencing text difficulty. Teaching vocabulary can improve reading comprehension for both native English speakers and English learners. (Graves, 2006, 2007) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

The Vocabulary Learning Task The vocabulary learning task is huge. The average fourth grader probably knows 5, 000 -10, 000 words. The average high school graduate probably knows 50, 000 words. To acquire this extensive vocabulary, he or she has learned something like 3, 500 words a year. This translates to learning 10 words a day. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

The Vocabulary Learning Task The vocabulary learning task is huge. The average fourth grader probably knows 5, 000 -10, 000 words. The average high school graduate probably knows 50, 000 words. To acquire this extensive vocabulary, he or she has learned something like 3, 500 words a year. This translates to learning 10 words a day. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Vocabulary Deficits Some students face debilitating vocabulary deficits. Many children of poverty enter school with vocabularies have the size of their middle-class counterparts (Hart & Risley, 1995, 2003). Once in school, they continue to learn words at about half the rate of their peers. In the intermediate grades and high school, their vocabularies are still half the size of those of their peers, possibly less. The same is true of many English learners. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Vocabulary Deficits Some students face debilitating vocabulary deficits. Many children of poverty enter school with vocabularies have the size of their middle-class counterparts (Hart & Risley, 1995, 2003). Once in school, they continue to learn words at about half the rate of their peers. In the intermediate grades and high school, their vocabularies are still half the size of those of their peers, possibly less. The same is true of many English learners. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Assisting Students in Building Strong Vocabularies Helping average students achieve vocabularies of 50, 000 words is a very substantial task. Helping students with small vocabularies catch up with their peers is an even more substantial task. Only a rich and multifaceted vocabulary program is likely to help students accomplish these tasks (Baumann & Kaméenui, 2004; Blachowicz, Fisher, Ogle, & Watts-Taffe, 2006; Graves, 2006; Stahl & Nagy, 2006). Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Assisting Students in Building Strong Vocabularies Helping average students achieve vocabularies of 50, 000 words is a very substantial task. Helping students with small vocabularies catch up with their peers is an even more substantial task. Only a rich and multifaceted vocabulary program is likely to help students accomplish these tasks (Baumann & Kaméenui, 2004; Blachowicz, Fisher, Ogle, & Watts-Taffe, 2006; Graves, 2006; Stahl & Nagy, 2006). Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

A Four-Pronged Vocabulary Program Frequent, varied, and extensive language experiences Teaching individual words Teaching word-learning strategies Fostering word consciousness See Baumann, Ware, and Edwards (2007) for a study validating this program. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

A Four-Pronged Vocabulary Program Frequent, varied, and extensive language experiences Teaching individual words Teaching word-learning strategies Fostering word consciousness See Baumann, Ware, and Edwards (2007) for a study validating this program. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words Is Just One Part of a Comprehensive and Multifaceted Vocabulary Program With something like 3, 500 words to learn each year, teaching individual words is just one part of the comprehensive and multipart program such as that outlined below and needs to recognized as a part of that whole. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words Is Just One Part of a Comprehensive and Multifaceted Vocabulary Program With something like 3, 500 words to learn each year, teaching individual words is just one part of the comprehensive and multipart program such as that outlined below and needs to recognized as a part of that whole. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Frequent, Varied, and Extensive Language Experiences · Reading, writing, discussion, and listening · The emphasis on these four modalities and the teaching/learning approaches used will vary over time. · With younger and less proficient readers, there is more discussion and listening and more teacher-led work. · With older and more proficient readers, there is more reading and writing and more independent work. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Frequent, Varied, and Extensive Language Experiences · Reading, writing, discussion, and listening · The emphasis on these four modalities and the teaching/learning approaches used will vary over time. · With younger and less proficient readers, there is more discussion and listening and more teacher-led work. · With older and more proficient readers, there is more reading and writing and more independent work. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Word-Learning Strategies • Using context • Learning and using word parts • Using glossaries and the dictionary • Recognizing and using cognates (for Spanish speakers) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Word-Learning Strategies • Using context • Learning and using word parts • Using glossaries and the dictionary • Recognizing and using cognates (for Spanish speakers) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Types of Word Consciousness Activities • Creating a Word-Rich Environment • Recognizing and Promoting Adept Diction • Promoting Word Play • Fostering Word Consciousness Through Writing • Involving Students in Original Investigations • Teaching Students about Words (Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2002, 2007) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Types of Word Consciousness Activities • Creating a Word-Rich Environment • Recognizing and Promoting Adept Diction • Promoting Word Play • Fostering Word Consciousness Through Writing • Involving Students in Original Investigations • Teaching Students about Words (Graves & Watts-Taffe, 2002, 2007) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words: The Word-Learning Tasks Students Face • Building a basic oral vocabulary • Learning to read known words • Learning to read new words representing known concepts • Learning to read new words representing new and challenging concepts • Learning new meanings for known words • Clarifying and enriching the meanings of known words • Moving words into students’ expressive vocabularies • Building English learners’ vocabularies • Teaching vocabulary to improve comprehension

Teaching Individual Words: The Word-Learning Tasks Students Face • Building a basic oral vocabulary • Learning to read known words • Learning to read new words representing known concepts • Learning to read new words representing new and challenging concepts • Learning new meanings for known words • Clarifying and enriching the meanings of known words • Moving words into students’ expressive vocabularies • Building English learners’ vocabularies • Teaching vocabulary to improve comprehension

Teaching Individual Words: Levels of Word Knowledge • No knowledge • Very general sense • Narrow, context-bound knowledge • Having a basic knowledge of a word and being able to use it in many appropriate situations. • Rich, decontextualized knowledge Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002 [slightly modified] Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words: Levels of Word Knowledge • No knowledge • Very general sense • Narrow, context-bound knowledge • Having a basic knowledge of a word and being able to use it in many appropriate situations. • Rich, decontextualized knowledge Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002 [slightly modified] Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words: Identifying Words To Teach — 1 • Word lists (Biemiller, in press; Chall & Dale, 1995, Coxhead, 2000; Fry, 2006; Hiebert, 2005) • Testing or asking students (Anderson & Freebody, 1983; White, Slater, & Graves, 1989) • Selecting tier two words (Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002) • Considering five questions (Graves, 2006, in press) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Teaching Individual Words: Identifying Words To Teach — 1 • Word lists (Biemiller, in press; Chall & Dale, 1995, Coxhead, 2000; Fry, 2006; Hiebert, 2005) • Testing or asking students (Anderson & Freebody, 1983; White, Slater, & Graves, 1989) • Selecting tier two words (Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002) • Considering five questions (Graves, 2006, in press) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Identifying Words to Teach— 2 Fry’s 1, 000 Instant Words (Fry & Kress, 2007). The 1, 000 most frequent words Dale’s list of 3, 000 Words (Chall & Dale, 1995). 3, 000 words that most 4 th graders know Hiebert's Word Zones: 5, 586/3, 913 Words grouped into set of ~300, ~500, ~1000, and ~2000 words. The 4, 000 most frequent word families http: //www. textproject. org/library/resources Biemiller's Words Worth Teaching in Kindergarten-Grade Two and in Grades Three-Six (Biemiller, in press). One list of about 2, 000 words and one of about 4, 000 words. Coxhead's Academic Word (Coxhead, 2000): 570 word families that occur reasonably frequently over a range of academic texts. http: //language. massey. ac. nz/staff/awl/corpus. shtml

Identifying Words to Teach— 2 Fry’s 1, 000 Instant Words (Fry & Kress, 2007). The 1, 000 most frequent words Dale’s list of 3, 000 Words (Chall & Dale, 1995). 3, 000 words that most 4 th graders know Hiebert's Word Zones: 5, 586/3, 913 Words grouped into set of ~300, ~500, ~1000, and ~2000 words. The 4, 000 most frequent word families http: //www. textproject. org/library/resources Biemiller's Words Worth Teaching in Kindergarten-Grade Two and in Grades Three-Six (Biemiller, in press). One list of about 2, 000 words and one of about 4, 000 words. Coxhead's Academic Word (Coxhead, 2000): 570 word families that occur reasonably frequently over a range of academic texts. http: //language. massey. ac. nz/staff/awl/corpus. shtml

Identifying Words To Teach— 3: Considering five questions • Is understanding the word important to understanding the selection? • Does this word represent a specific concept students definitely need to know? • Are students able to use context or structural-analysis skills to discover the word's meaning? • Can working with this word be useful in furthering students’ context, structural analysis, or dictionary skills? • How useful is this word outside of the reading selection currently being taught? Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Identifying Words To Teach— 3: Considering five questions • Is understanding the word important to understanding the selection? • Does this word represent a specific concept students definitely need to know? • Are students able to use context or structural-analysis skills to discover the word's meaning? • Can working with this word be useful in furthering students’ context, structural analysis, or dictionary skills? • How useful is this word outside of the reading selection currently being taught? Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Characteristics of Effective Instruction for Individual Words • Instruction that involves both definitional information and contextual information is markedly stronger than instruction that involves only one of these. • Instruction that involves activating prior knowledge and comparing and contrasting meanings is stronger still. • More lengthy and more robust instruction that involves students in actively manipulating meanings, making inferences, searching for applications, using prior knowledge, and frequent encounters is still stronger. • Stronger vocabulary instruction takes more time, and with the number of words to be learned we very often do not have more time. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Characteristics of Effective Instruction for Individual Words • Instruction that involves both definitional information and contextual information is markedly stronger than instruction that involves only one of these. • Instruction that involves activating prior knowledge and comparing and contrasting meanings is stronger still. • More lengthy and more robust instruction that involves students in actively manipulating meanings, making inferences, searching for applications, using prior knowledge, and frequent encounters is still stronger. • Stronger vocabulary instruction takes more time, and with the number of words to be learned we very often do not have more time. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Three Levels of Effective Instruction for Individual Words • Level One. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, and (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence. • Level Two. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence, and (4) provide an activity that requires students to activate prior knowledge or compare and contrast meanings. • Level Three. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence, (4) provide an activity that requires students to activate prior knowledge or compare and contrast meanings, and (5) and involve students in actively manipulating meanings, making inferences, and/or searching for applications. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Three Levels of Effective Instruction for Individual Words • Level One. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, and (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence. • Level Two. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence, and (4) provide an activity that requires students to activate prior knowledge or compare and contrast meanings. • Level Three. (1) Pronounce the word, (2) provide a student friendly definition, (3) use the word in a contextually rich sentence, (4) provide an activity that requires students to activate prior knowledge or compare and contrast meanings, and (5) and involve students in actively manipulating meanings, making inferences, and/or searching for applications. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Things Not to Do in Teaching Individual Words Merely mentioning word meanings and assuming that you have therefore taught them Giving students words out of context and asking them to look up the words in the dictionary Asking students to use context before teaching them how to do so Doing speeded trials with individual words Giving students only a definition or only the word in context Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Things Not to Do in Teaching Individual Words Merely mentioning word meanings and assuming that you have therefore taught them Giving students words out of context and asking them to look up the words in the dictionary Asking students to use context before teaching them how to do so Doing speeded trials with individual words Giving students only a definition or only the word in context Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

PROVIDING STUDENT-FRIENDLY DEFINITIONS—A KEY TO ANY METHOD OF INSTRUCTION Providing student-friendly definitions—ones that are accurate and that students will understand—is no mean task. Below are a definition of dazzling from the dictionary on my computer and a student-friendly definition from Beck, Mc. Keown, and Kucan (2003). “bright enough to deprive someone of sight temporarily” “If something is dazzling, that means that it’s so bright that you can hardly look at it. ” The Collins COBUILD New Student’s Dictionary (Harper-Collins, 2006) and the Longman Study Dictionary of American English (2006) provide many excellent examples of student-friendly definitions.

PROVIDING STUDENT-FRIENDLY DEFINITIONS—A KEY TO ANY METHOD OF INSTRUCTION Providing student-friendly definitions—ones that are accurate and that students will understand—is no mean task. Below are a definition of dazzling from the dictionary on my computer and a student-friendly definition from Beck, Mc. Keown, and Kucan (2003). “bright enough to deprive someone of sight temporarily” “If something is dazzling, that means that it’s so bright that you can hardly look at it. ” The Collins COBUILD New Student’s Dictionary (Harper-Collins, 2006) and the Longman Study Dictionary of American English (2006) provide many excellent examples of student-friendly definitions.

BUILDING A BASIC ORAL VOCABULARY: SHARED BOOK READING Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

BUILDING A BASIC ORAL VOCABULARY: SHARED BOOK READING Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Characteristics of Effective Shared Book Reading · Both the adult readers and children are active participants. · Involves several readings · Focuses attention on words · The reading is fluent, engaging, and lively. · Deliberately stretches students and scaffolds their efforts · Employs carefully selected words and books Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Characteristics of Effective Shared Book Reading · Both the adult readers and children are active participants. · Involves several readings · Focuses attention on words · The reading is fluent, engaging, and lively. · Deliberately stretches students and scaffolds their efforts · Employs carefully selected words and books Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

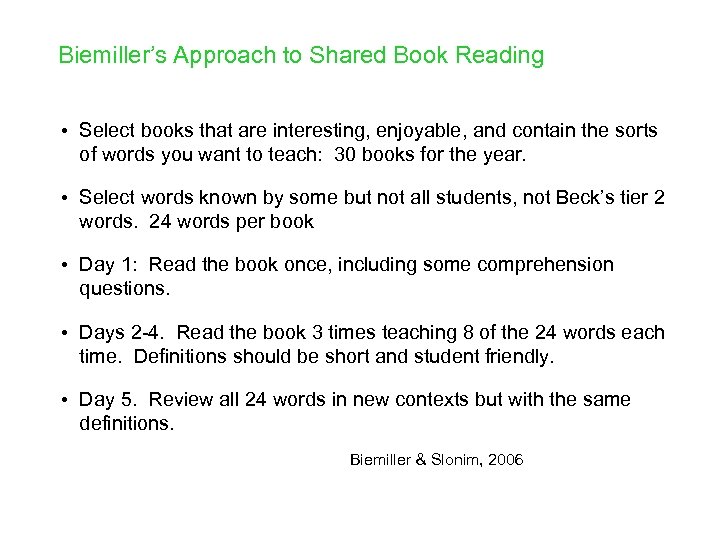

Biemiller’s Approach to Shared Book Reading • Select books that are interesting, enjoyable, and contain the sorts of words you want to teach: 30 books for the year. • Select words known by some but not all students, not Beck’s tier 2 words. 24 words per book • Day 1: Read the book once, including some comprehension questions. • Days 2 -4. Read the book 3 times teaching 8 of the 24 words each time. Definitions should be short and student friendly. • Day 5. Review all 24 words in new contexts but with the same definitions. Biemiller & Slonim, 2006

Biemiller’s Approach to Shared Book Reading • Select books that are interesting, enjoyable, and contain the sorts of words you want to teach: 30 books for the year. • Select words known by some but not all students, not Beck’s tier 2 words. 24 words per book • Day 1: Read the book once, including some comprehension questions. • Days 2 -4. Read the book 3 times teaching 8 of the 24 words each time. Definitions should be short and student friendly. • Day 5. Review all 24 words in new contexts but with the same definitions. Biemiller & Slonim, 2006

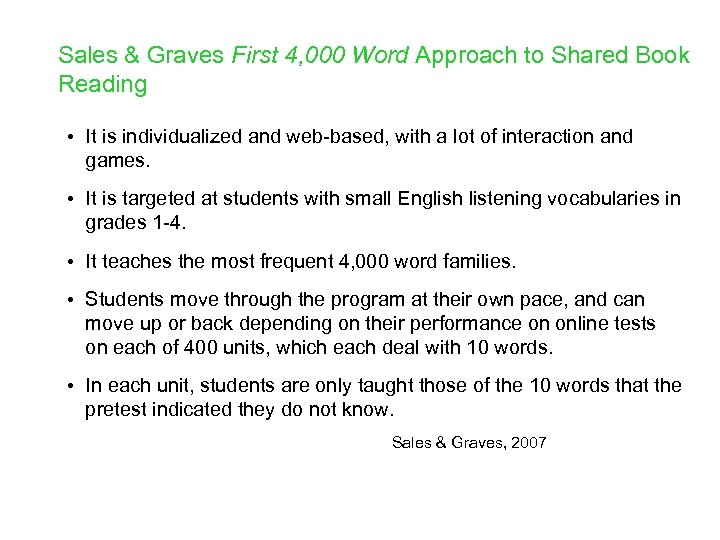

Sales & Graves First 4, 000 Word Approach to Shared Book Reading • It is individualized and web-based, with a lot of interaction and games. • It is targeted at students with small English listening vocabularies in grades 1 -4. • It teaches the most frequent 4, 000 word families. • Students move through the program at their own pace, and can move up or back depending on their performance on online tests on each of 400 units, which each deal with 10 words. • In each unit, students are only taught those of the 10 words that the pretest indicated they do not know. Sales & Graves, 2007

Sales & Graves First 4, 000 Word Approach to Shared Book Reading • It is individualized and web-based, with a lot of interaction and games. • It is targeted at students with small English listening vocabularies in grades 1 -4. • It teaches the most frequent 4, 000 word families. • Students move through the program at their own pace, and can move up or back depending on their performance on online tests on each of 400 units, which each deal with 10 words. • In each unit, students are only taught those of the 10 words that the pretest indicated they do not know. Sales & Graves, 2007

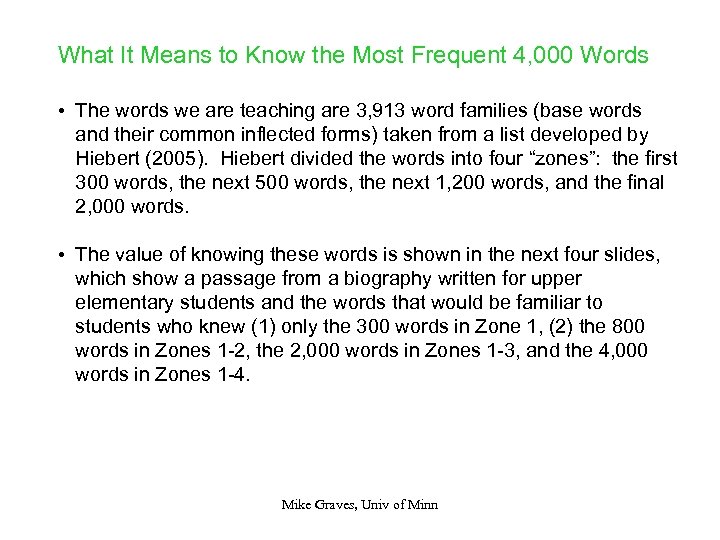

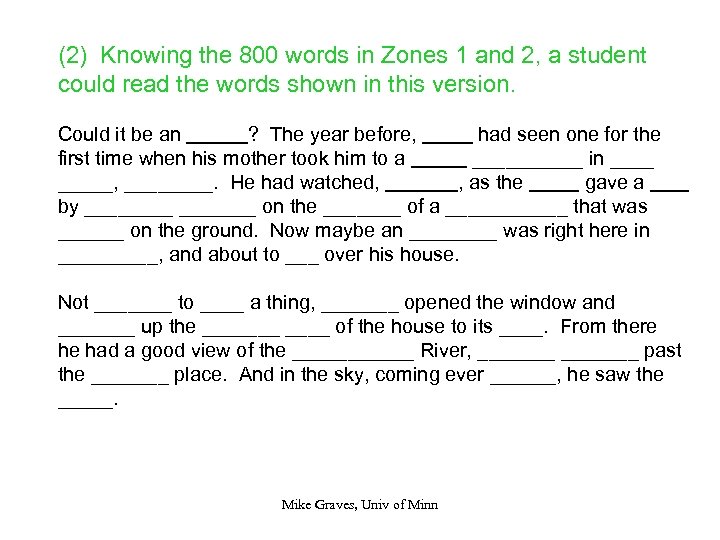

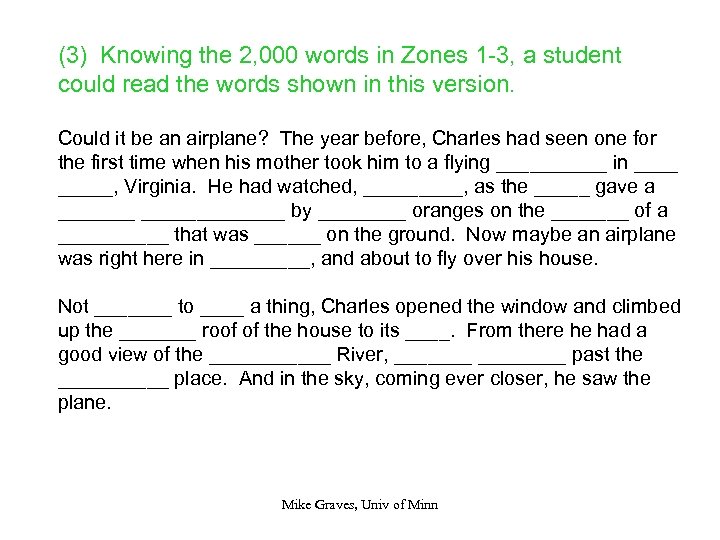

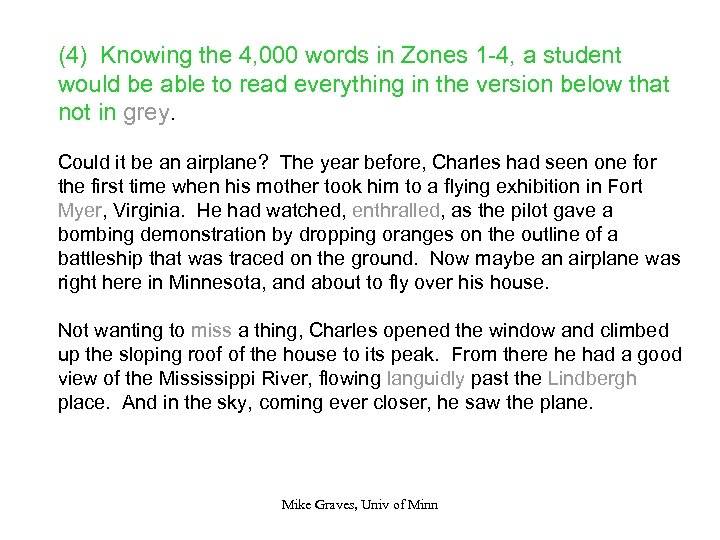

What It Means to Know the Most Frequent 4, 000 Words • The words we are teaching are 3, 913 word families (base words and their common inflected forms) taken from a list developed by Hiebert (2005). Hiebert divided the words into four “zones”: the first 300 words, the next 500 words, the next 1, 200 words, and the final 2, 000 words. • The value of knowing these words is shown in the next four slides, which show a passage from a biography written for upper elementary students and the words that would be familiar to students who knew (1) only the 300 words in Zone 1, (2) the 800 words in Zones 1 -2, the 2, 000 words in Zones 1 -3, and the 4, 000 words in Zones 1 -4. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

What It Means to Know the Most Frequent 4, 000 Words • The words we are teaching are 3, 913 word families (base words and their common inflected forms) taken from a list developed by Hiebert (2005). Hiebert divided the words into four “zones”: the first 300 words, the next 500 words, the next 1, 200 words, and the final 2, 000 words. • The value of knowing these words is shown in the next four slides, which show a passage from a biography written for upper elementary students and the words that would be familiar to students who knew (1) only the 300 words in Zone 1, (2) the 800 words in Zones 1 -2, the 2, 000 words in Zones 1 -3, and the 4, 000 words in Zones 1 -4. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

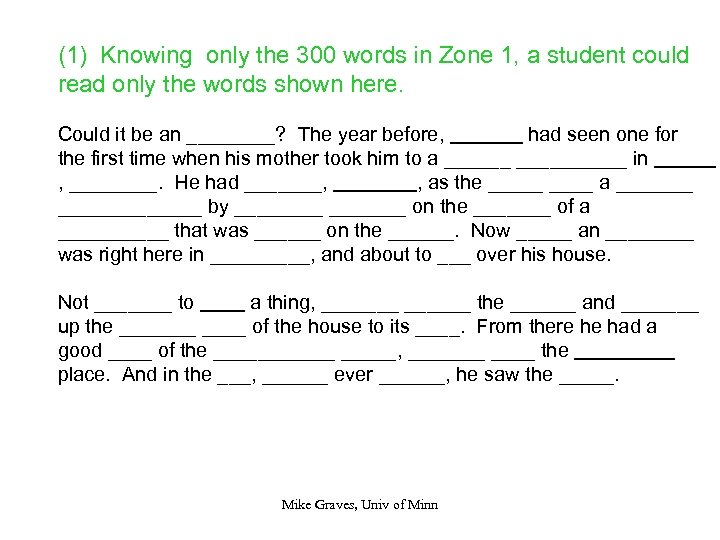

(1) Knowing only the 300 words in Zone 1, a student could read only the words shown here. Could it be an ____? The year before, had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a __________ in , ____. He had _______, , as the _____ a _____________ by _______ on the _______ of a _____ that was ______ on the ______. Now _____ an ____ was right here in _____, and about to ___ over his house. Not _______ to a thing, _______ the ______ and _______ up the _______ of the house to its ____. From there he had a good ____ of the ______, _______ the place. And in the ___, ______ ever ______, he saw the _____. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(1) Knowing only the 300 words in Zone 1, a student could read only the words shown here. Could it be an ____? The year before, had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a __________ in , ____. He had _______, , as the _____ a _____________ by _______ on the _______ of a _____ that was ______ on the ______. Now _____ an ____ was right here in _____, and about to ___ over his house. Not _______ to a thing, _______ the ______ and _______ up the _______ of the house to its ____. From there he had a good ____ of the ______, _______ the place. And in the ___, ______ ever ______, he saw the _____. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(2) Knowing the 800 words in Zones 1 and 2, a student could read the words shown in this version. Could it be an ? The year before, had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a _____ in _____, ____. He had watched, , as the gave a by _______ on the _______ of a ______ that was ______ on the ground. Now maybe an ____ was right here in _____, and about to ___ over his house. Not _______ to ____ a thing, _______ opened the window and _______ up the _______ of the house to its ____. From there he had a good view of the ______ River, _______ past the _______ place. And in the sky, coming ever ______, he saw the _____. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(2) Knowing the 800 words in Zones 1 and 2, a student could read the words shown in this version. Could it be an ? The year before, had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a _____ in _____, ____. He had watched, , as the gave a by _______ on the _______ of a ______ that was ______ on the ground. Now maybe an ____ was right here in _____, and about to ___ over his house. Not _______ to ____ a thing, _______ opened the window and _______ up the _______ of the house to its ____. From there he had a good view of the ______ River, _______ past the _______ place. And in the sky, coming ever ______, he saw the _____. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(3) Knowing the 2, 000 words in Zones 1 -3, a student could read the words shown in this version. Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying _____ in _____, Virginia. He had watched, _____, as the _____ gave a _____________ by ____ oranges on the _______ of a _____ that was ______ on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in _____, and about to fly over his house. Not _______ to ____ a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the _______ roof of the house to its ____. From there he had a good view of the ______ River, ________ past the _____ place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(3) Knowing the 2, 000 words in Zones 1 -3, a student could read the words shown in this version. Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying _____ in _____, Virginia. He had watched, _____, as the _____ gave a _____________ by ____ oranges on the _______ of a _____ that was ______ on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in _____, and about to fly over his house. Not _______ to ____ a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the _______ roof of the house to its ____. From there he had a good view of the ______ River, ________ past the _____ place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(4) Knowing the 4, 000 words in Zones 1 -4, a student would be able to read everything in the version below that not in grey. Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying exhibition in Fort Myer, Virginia. He had watched, enthralled, as the pilot gave a bombing demonstration by dropping oranges on the outline of a battleship that was traced on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in Minnesota, and about to fly over his house. Not wanting to miss a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the sloping roof of the house to its peak. From there he had a good view of the Mississippi River, flowing languidly past the Lindbergh place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

(4) Knowing the 4, 000 words in Zones 1 -4, a student would be able to read everything in the version below that not in grey. Could it be an airplane? The year before, Charles had seen one for the first time when his mother took him to a flying exhibition in Fort Myer, Virginia. He had watched, enthralled, as the pilot gave a bombing demonstration by dropping oranges on the outline of a battleship that was traced on the ground. Now maybe an airplane was right here in Minnesota, and about to fly over his house. Not wanting to miss a thing, Charles opened the window and climbed up the sloping roof of the house to its peak. From there he had a good view of the Mississippi River, flowing languidly past the Lindbergh place. And in the sky, coming ever closer, he saw the plane. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

First 4, 000 Words Opening Screen Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

First 4, 000 Words Opening Screen Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

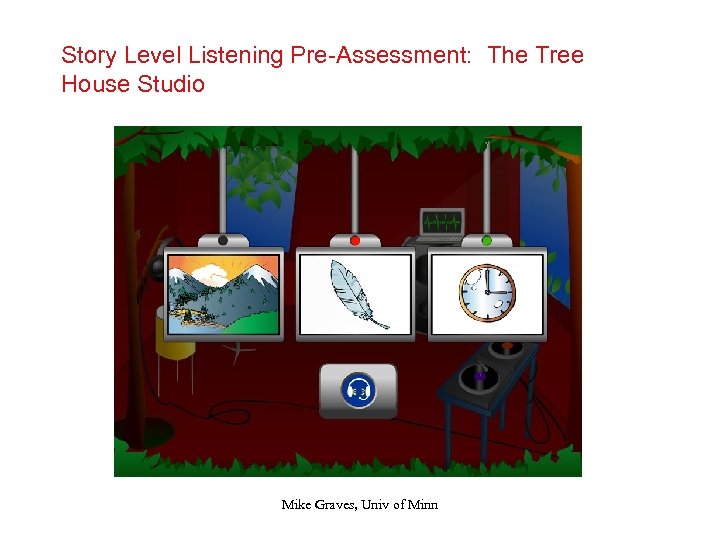

Story Level Listening Pre-Assessment: The Tree House Studio Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Story Level Listening Pre-Assessment: The Tree House Studio Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

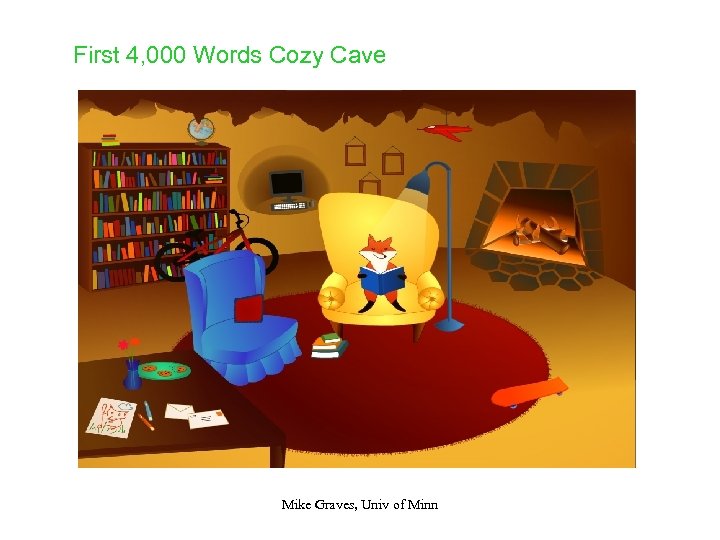

First 4, 000 Words Cozy Cave Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

First 4, 000 Words Cozy Cave Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

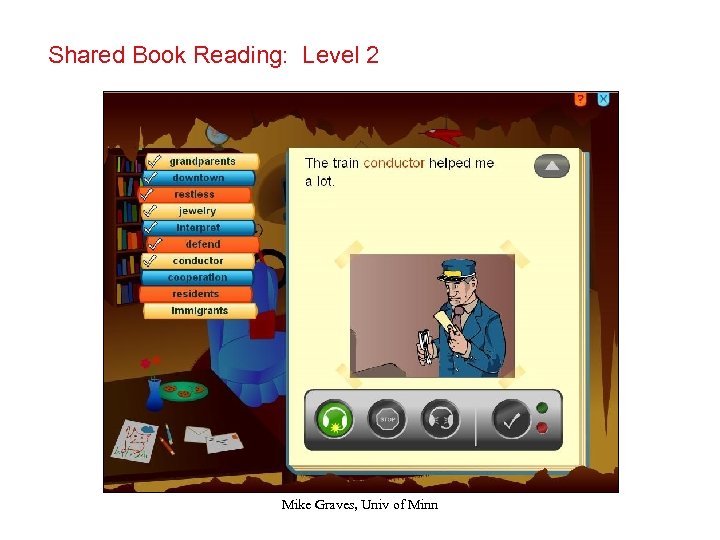

Shared Book Reading: Level 2 Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Shared Book Reading: Level 2 Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

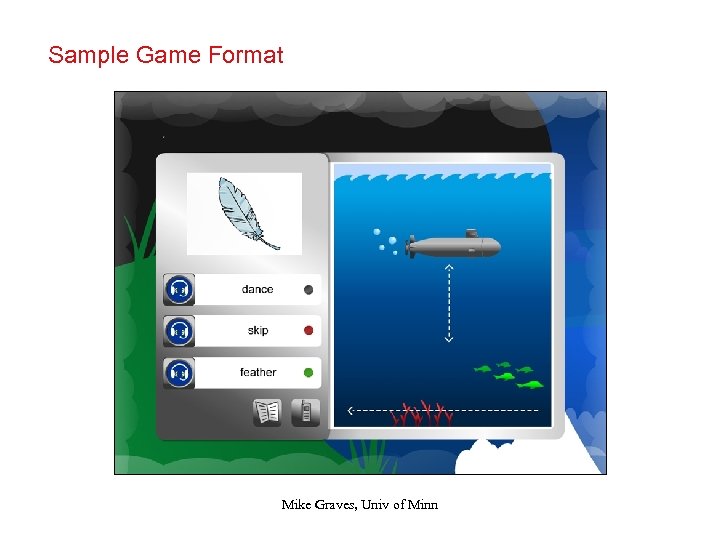

Sample Game Format Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Sample Game Format Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

RICH AND POWERFUL INSTRUCTION • Semantic mapping (Heimlich & Pittleman, 1986) • Semantic feature analysis (Pittleman et al. , 1991) • Vocabulary visits (Blachowicz & Obrochta, 2005) • Robust instruction (Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002) • Frayer method (Frayer, Frederick, & Klausmeier, 1969) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

RICH AND POWERFUL INSTRUCTION • Semantic mapping (Heimlich & Pittleman, 1986) • Semantic feature analysis (Pittleman et al. , 1991) • Vocabulary visits (Blachowicz & Obrochta, 2005) • Robust instruction (Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan, 2002) • Frayer method (Frayer, Frederick, & Klausmeier, 1969) Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

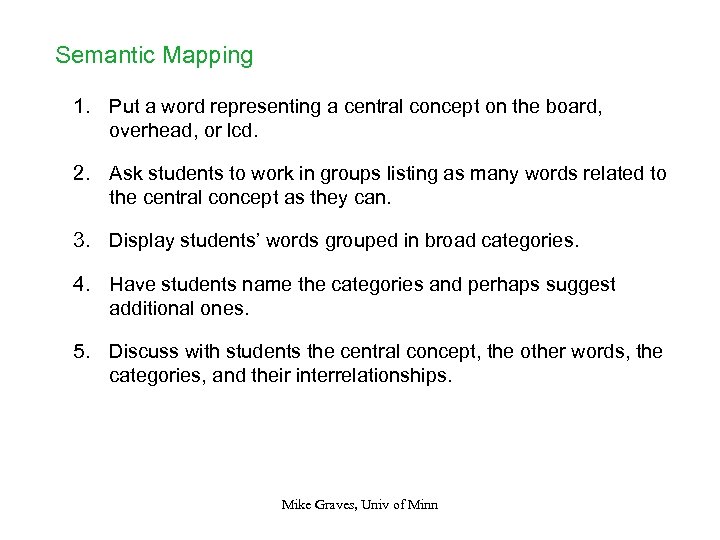

Semantic Mapping 1. Put a word representing a central concept on the board, overhead, or lcd. 2. Ask students to work in groups listing as many words related to the central concept as they can. 3. Display students’ words grouped in broad categories. 4. Have students name the categories and perhaps suggest additional ones. 5. Discuss with students the central concept, the other words, the categories, and their interrelationships. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Semantic Mapping 1. Put a word representing a central concept on the board, overhead, or lcd. 2. Ask students to work in groups listing as many words related to the central concept as they can. 3. Display students’ words grouped in broad categories. 4. Have students name the categories and perhaps suggest additional ones. 5. Discuss with students the central concept, the other words, the categories, and their interrelationships. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

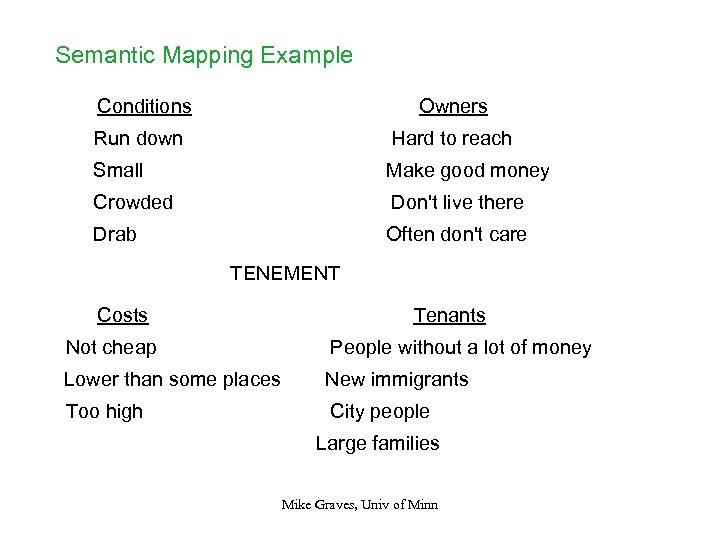

Semantic Mapping Example Conditions Owners Run down Hard to reach Small Make good money Crowded Don't live there Drab Often don't care TENEMENT Costs Tenants Not cheap People without a lot of money Lower than some places New immigrants Too high City people Large families Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Semantic Mapping Example Conditions Owners Run down Hard to reach Small Make good money Crowded Don't live there Drab Often don't care TENEMENT Costs Tenants Not cheap People without a lot of money Lower than some places New immigrants Too high City people Large families Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

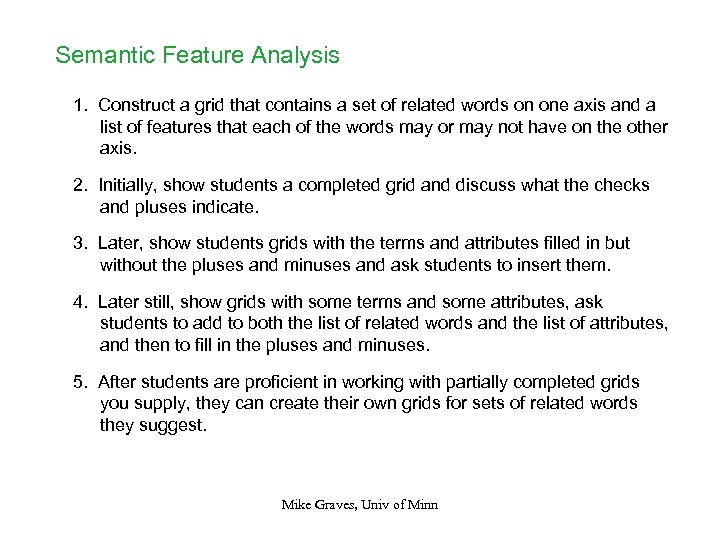

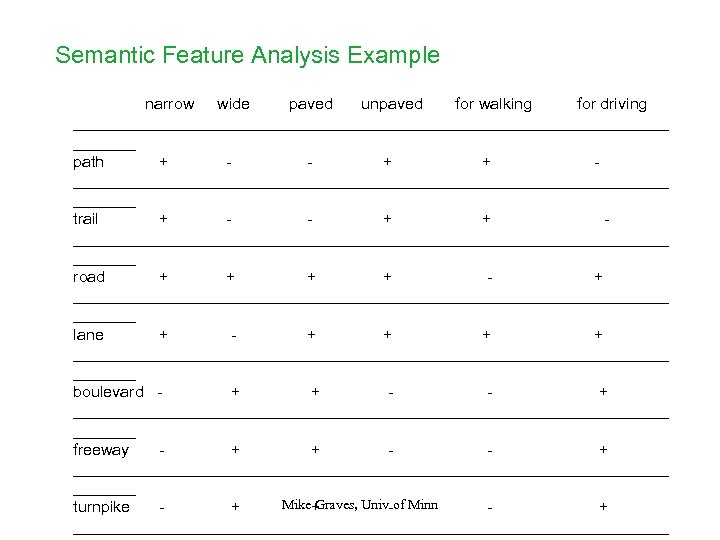

Semantic Feature Analysis 1. Construct a grid that contains a set of related words on one axis and a list of features that each of the words may or may not have on the other axis. 2. Initially, show students a completed grid and discuss what the checks and pluses indicate. 3. Later, show students grids with the terms and attributes filled in but without the pluses and minuses and ask students to insert them. 4. Later still, show grids with some terms and some attributes, ask students to add to both the list of related words and the list of attributes, and then to fill in the pluses and minuses. 5. After students are proficient in working with partially completed grids you supply, they can create their own grids for sets of related words they suggest. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Semantic Feature Analysis 1. Construct a grid that contains a set of related words on one axis and a list of features that each of the words may or may not have on the other axis. 2. Initially, show students a completed grid and discuss what the checks and pluses indicate. 3. Later, show students grids with the terms and attributes filled in but without the pluses and minuses and ask students to insert them. 4. Later still, show grids with some terms and some attributes, ask students to add to both the list of related words and the list of attributes, and then to fill in the pluses and minuses. 5. After students are proficient in working with partially completed grids you supply, they can create their own grids for sets of related words they suggest. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Semantic Feature Analysis Example narrow wide paved unpaved for walking for driving __________________________________ path + + + __________________________________ trail + + + __________________________________ road + + + __________________________________ lane + + + __________________________________ boulevard + + + __________________________________ freeway + + + __________________________________ Mike+ Graves, Univ-of Minn turnpike + + __________________________________

Semantic Feature Analysis Example narrow wide paved unpaved for walking for driving __________________________________ path + + + __________________________________ trail + + + __________________________________ road + + + __________________________________ lane + + + __________________________________ boulevard + + + __________________________________ freeway + + + __________________________________ Mike+ Graves, Univ-of Minn turnpike + + __________________________________

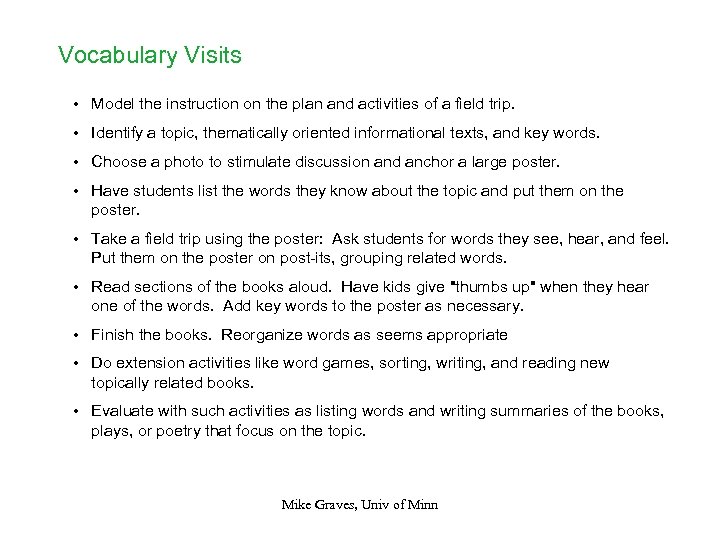

Vocabulary Visits • Model the instruction on the plan and activities of a field trip. • Identify a topic, thematically oriented informational texts, and key words. • Choose a photo to stimulate discussion and anchor a large poster. • Have students list the words they know about the topic and put them on the poster. • Take a field trip using the poster: Ask students for words they see, hear, and feel. Put them on the poster on post-its, grouping related words. • Read sections of the books aloud. Have kids give "thumbs up" when they hear one of the words. Add key words to the poster as necessary. • Finish the books. Reorganize words as seems appropriate • Do extension activities like word games, sorting, writing, and reading new topically related books. • Evaluate with such activities as listing words and writing summaries of the books, plays, or poetry that focus on the topic. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Vocabulary Visits • Model the instruction on the plan and activities of a field trip. • Identify a topic, thematically oriented informational texts, and key words. • Choose a photo to stimulate discussion and anchor a large poster. • Have students list the words they know about the topic and put them on the poster. • Take a field trip using the poster: Ask students for words they see, hear, and feel. Put them on the poster on post-its, grouping related words. • Read sections of the books aloud. Have kids give "thumbs up" when they hear one of the words. Add key words to the poster as necessary. • Finish the books. Reorganize words as seems appropriate • Do extension activities like word games, sorting, writing, and reading new topically related books. • Evaluate with such activities as listing words and writing summaries of the books, plays, or poetry that focus on the topic. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

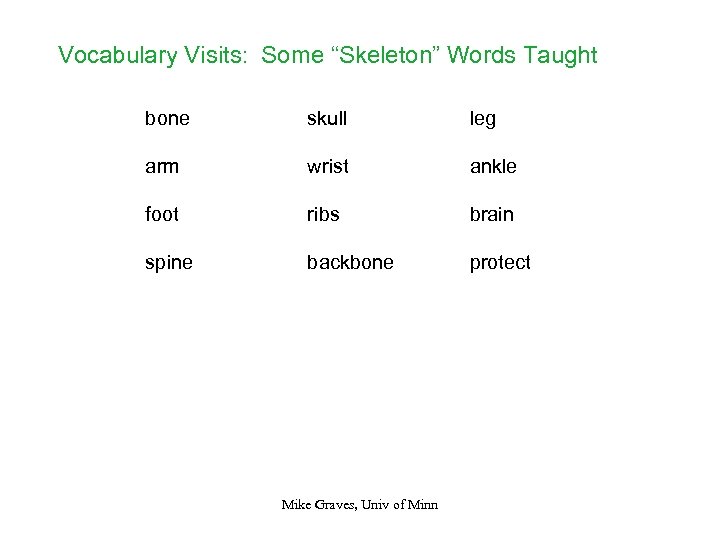

Vocabulary Visits: Some “Skeleton” Words Taught bone skull leg arm wrist ankle foot ribs brain spine backbone protect Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Vocabulary Visits: Some “Skeleton” Words Taught bone skull leg arm wrist ankle foot ribs brain spine backbone protect Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

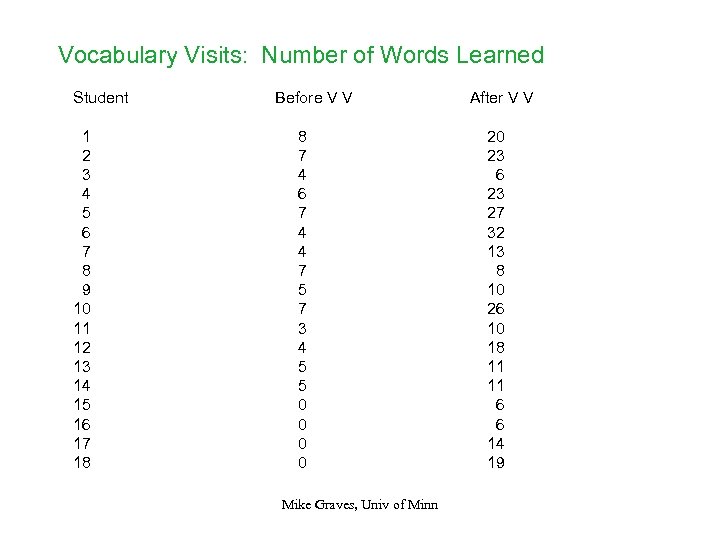

Vocabulary Visits: Number of Words Learned Student 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Before V V 8 7 4 6 7 4 4 7 5 7 3 4 5 5 0 0 Mike Graves, Univ of Minn After V V 20 23 6 23 27 32 13 8 10 26 10 18 11 11 6 6 14 19

Vocabulary Visits: Number of Words Learned Student 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Before V V 8 7 4 6 7 4 4 7 5 7 3 4 5 5 0 0 Mike Graves, Univ of Minn After V V 20 23 6 23 27 32 13 8 10 26 10 18 11 11 6 6 14 19

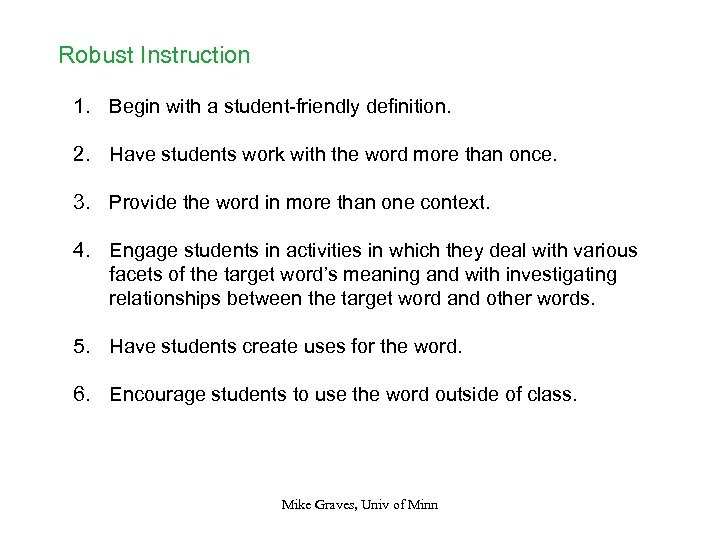

Robust Instruction 1. Begin with a student-friendly definition. 2. Have students work with the word more than once. 3. Provide the word in more than one context. 4. Engage students in activities in which they deal with various facets of the target word’s meaning and with investigating relationships between the target word and other words. 5. Have students create uses for the word. 6. Encourage students to use the word outside of class. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Robust Instruction 1. Begin with a student-friendly definition. 2. Have students work with the word more than once. 3. Provide the word in more than one context. 4. Engage students in activities in which they deal with various facets of the target word’s meaning and with investigating relationships between the target word and other words. 5. Have students create uses for the word. 6. Encourage students to use the word outside of class. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

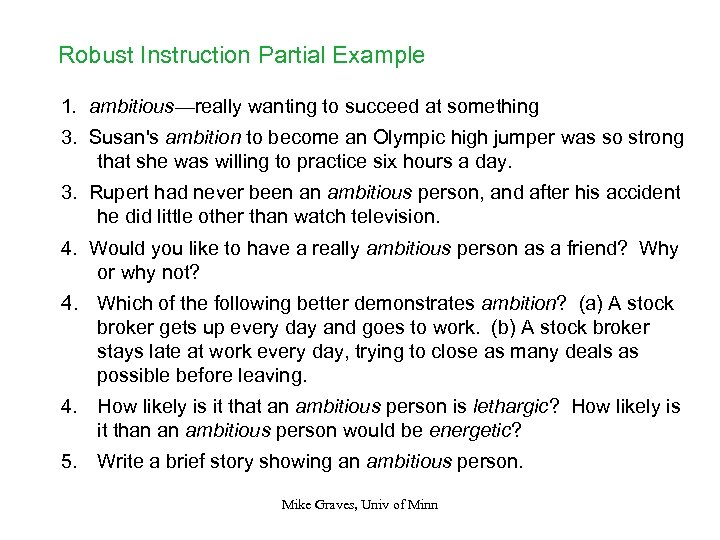

Robust Instruction Partial Example 1. ambitious—really wanting to succeed at something 3. Susan's ambition to become an Olympic high jumper was so strong that she was willing to practice six hours a day. 3. Rupert had never been an ambitious person, and after his accident he did little other than watch television. 4. Would you like to have a really ambitious person as a friend? Why or why not? 4. Which of the following better demonstrates ambition? (a) A stock broker gets up every day and goes to work. (b) A stock broker stays late at work every day, trying to close as many deals as possible before leaving. 4. How likely is it that an ambitious person is lethargic? How likely is it than an ambitious person would be energetic? 5. Write a brief story showing an ambitious person. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Robust Instruction Partial Example 1. ambitious—really wanting to succeed at something 3. Susan's ambition to become an Olympic high jumper was so strong that she was willing to practice six hours a day. 3. Rupert had never been an ambitious person, and after his accident he did little other than watch television. 4. Would you like to have a really ambitious person as a friend? Why or why not? 4. Which of the following better demonstrates ambition? (a) A stock broker gets up every day and goes to work. (b) A stock broker stays late at work every day, trying to close as many deals as possible before leaving. 4. How likely is it that an ambitious person is lethargic? How likely is it than an ambitious person would be energetic? 5. Write a brief story showing an ambitious person. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

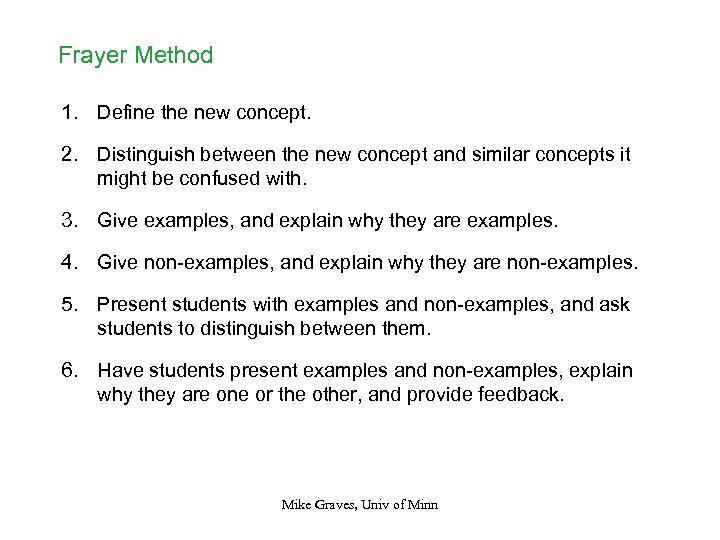

Frayer Method 1. Define the new concept. 2. Distinguish between the new concept and similar concepts it might be confused with. 3. Give examples, and explain why they are examples. 4. Give non-examples, and explain why they are non-examples. 5. Present students with examples and non-examples, and ask students to distinguish between them. 6. Have students present examples and non-examples, explain why they are one or the other, and provide feedback. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Frayer Method 1. Define the new concept. 2. Distinguish between the new concept and similar concepts it might be confused with. 3. Give examples, and explain why they are examples. 4. Give non-examples, and explain why they are non-examples. 5. Present students with examples and non-examples, and ask students to distinguish between them. 6. Have students present examples and non-examples, explain why they are one or the other, and provide feedback. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

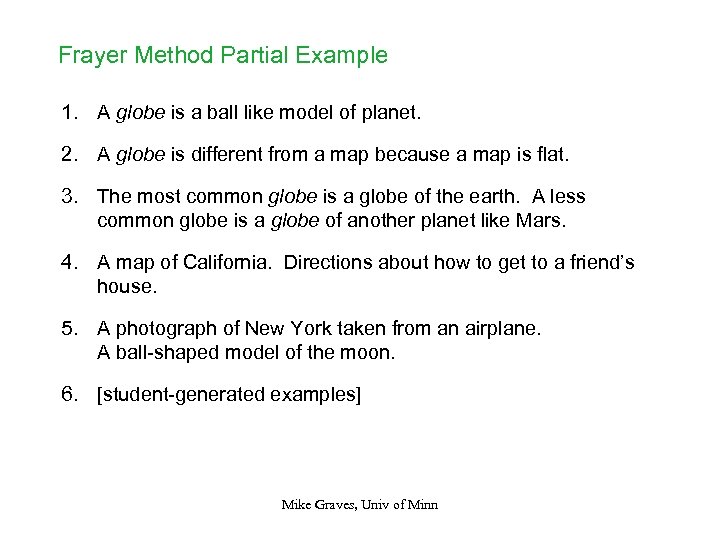

Frayer Method Partial Example 1. A globe is a ball like model of planet. 2. A globe is different from a map because a map is flat. 3. The most common globe is a globe of the earth. A less common globe is a globe of another planet like Mars. 4. A map of California. Directions about how to get to a friend’s house. 5. A photograph of New York taken from an airplane. A ball-shaped model of the moon. 6. [student-generated examples] Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Frayer Method Partial Example 1. A globe is a ball like model of planet. 2. A globe is different from a map because a map is flat. 3. The most common globe is a globe of the earth. A less common globe is a globe of another planet like Mars. 4. A map of California. Directions about how to get to a friend’s house. 5. A photograph of New York taken from an airplane. A ball-shaped model of the moon. 6. [student-generated examples] Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

INTRODUCTORY INSTRUCTION • Providing glossaries • Using pictures • Context/dictionary/discussion • Context/relationship Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

INTRODUCTORY INSTRUCTION • Providing glossaries • Using pictures • Context/dictionary/discussion • Context/relationship Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Providing glossaries Probably the least time-consuming and least intrusive thing you can do to assist students with the vocabulary of selections they are reading is to provide glossaries of important terms. tsu-na-mi. A large wave that can occur after an underwater earthquake Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Providing glossaries Probably the least time-consuming and least intrusive thing you can do to assist students with the vocabulary of selections they are reading is to provide glossaries of important terms. tsu-na-mi. A large wave that can occur after an underwater earthquake Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Using Pictures Solar system. The nine planets that revolve around our sun make up our solar system. Someday it may be possible for humans to explore all the planets in our solar system, but that will not be soon. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Using Pictures Solar system. The nine planets that revolve around our sun make up our solar system. Someday it may be possible for humans to explore all the planets in our solar system, but that will not be soon. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Context/Dictionary/Discussion Procedure • Give students the word in a fairly rich context. • For example, admire “We admire the paintings of great artists at the museum. ” • Ask them to look it up in the dictionary. • Discuss the definitions they come up with. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Context/Dictionary/Discussion Procedure • Give students the word in a fairly rich context. • For example, admire “We admire the paintings of great artists at the museum. ” • Ask them to look it up in the dictionary. • Discuss the definitions they come up with. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

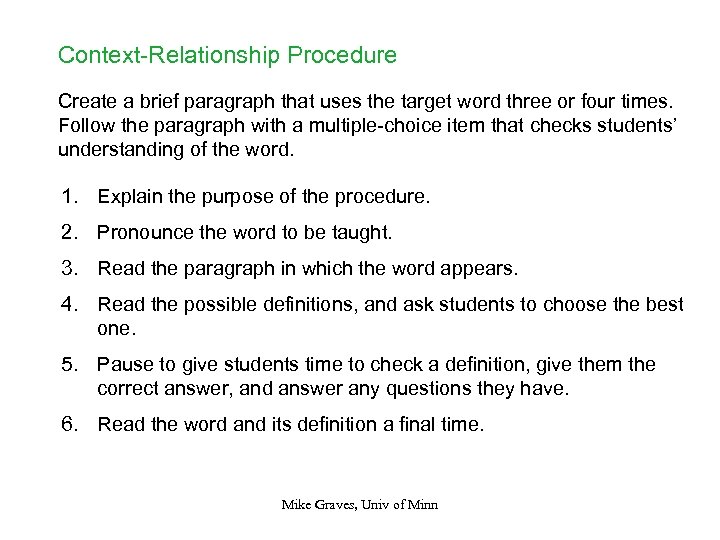

Context-Relationship Procedure Create a brief paragraph that uses the target word three or four times. Follow the paragraph with a multiple-choice item that checks students’ understanding of the word. 1. Explain the purpose of the procedure. 2. Pronounce the word to be taught. 3. Read the paragraph in which the word appears. 4. Read the possible definitions, and ask students to choose the best one. 5. Pause to give students time to check a definition, give them the correct answer, and answer any questions they have. 6. Read the word and its definition a final time. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Context-Relationship Procedure Create a brief paragraph that uses the target word three or four times. Follow the paragraph with a multiple-choice item that checks students’ understanding of the word. 1. Explain the purpose of the procedure. 2. Pronounce the word to be taught. 3. Read the paragraph in which the word appears. 4. Read the possible definitions, and ask students to choose the best one. 5. Pause to give students time to check a definition, give them the correct answer, and answer any questions they have. 6. Read the word and its definition a final time. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

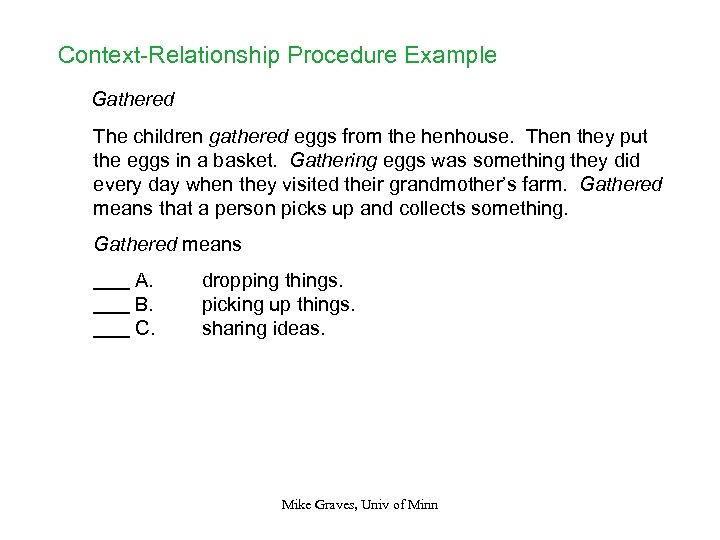

Context-Relationship Procedure Example Gathered The children gathered eggs from the henhouse. Then they put the eggs in a basket. Gathering eggs was something they did every day when they visited their grandmother’s farm. Gathered means that a person picks up and collects something. Gathered means A. B. C. dropping things. picking up things. sharing ideas. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Context-Relationship Procedure Example Gathered The children gathered eggs from the henhouse. Then they put the eggs in a basket. Gathering eggs was something they did every day when they visited their grandmother’s farm. Gathered means that a person picks up and collects something. Gathered means A. B. C. dropping things. picking up things. sharing ideas. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

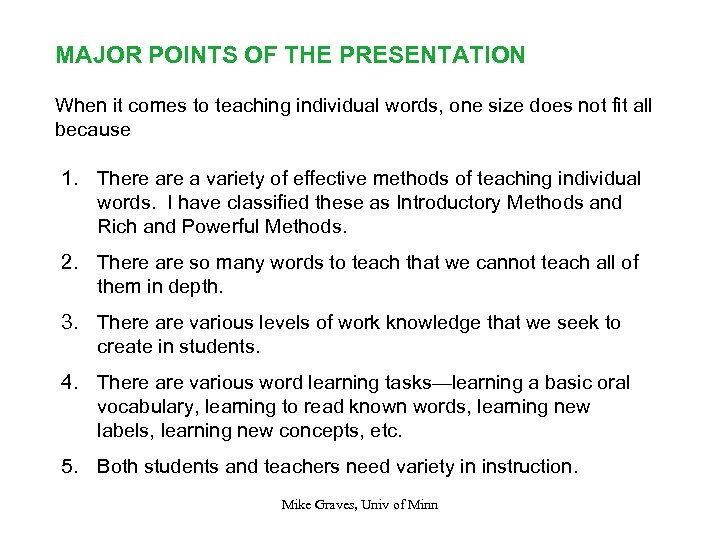

MAJOR POINTS OF THE PRESENTATION When it comes to teaching individual words, one size does not fit all because 1. There a variety of effective methods of teaching individual words. I have classified these as Introductory Methods and Rich and Powerful Methods. 2. There are so many words to teach that we cannot teach all of them in depth. 3. There are various levels of work knowledge that we seek to create in students. 4. There are various word learning tasks—learning a basic oral vocabulary, learning to read known words, learning new labels, learning new concepts, etc. 5. Both students and teachers need variety in instruction. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

MAJOR POINTS OF THE PRESENTATION When it comes to teaching individual words, one size does not fit all because 1. There a variety of effective methods of teaching individual words. I have classified these as Introductory Methods and Rich and Powerful Methods. 2. There are so many words to teach that we cannot teach all of them in depth. 3. There are various levels of work knowledge that we seek to create in students. 4. There are various word learning tasks—learning a basic oral vocabulary, learning to read known words, learning new labels, learning new concepts, etc. 5. Both students and teachers need variety in instruction. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

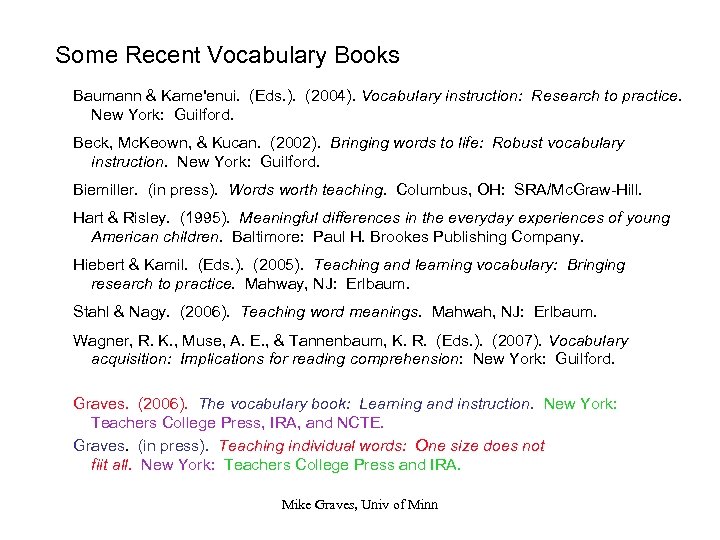

Some Recent Vocabulary Books Baumann & Kame'enui. (Eds. ). (2004). Vocabulary instruction: Research to practice. New York: Guilford. Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford. Biemiller. (in press). Words worth teaching. Columbus, OH: SRA/Mc. Graw-Hill. Hart & Risley. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company. Hiebert & Kamil. (Eds. ). (2005). Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum. Stahl & Nagy. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Wagner, R. K. , Muse, A. E. , & Tannenbaum, K. R. (Eds. ). (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension: New York: Guilford. Graves. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York: Teachers College Press, IRA, and NCTE. Graves. (in press). Teaching individual words: One size does not fiit all. New York: Teachers College Press and IRA. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

Some Recent Vocabulary Books Baumann & Kame'enui. (Eds. ). (2004). Vocabulary instruction: Research to practice. New York: Guilford. Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford. Biemiller. (in press). Words worth teaching. Columbus, OH: SRA/Mc. Graw-Hill. Hart & Risley. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company. Hiebert & Kamil. (Eds. ). (2005). Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum. Stahl & Nagy. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Wagner, R. K. , Muse, A. E. , & Tannenbaum, K. R. (Eds. ). (2007). Vocabulary acquisition: Implications for reading comprehension: New York: Guilford. Graves. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York: Teachers College Press, IRA, and NCTE. Graves. (in press). Teaching individual words: One size does not fiit all. New York: Teachers College Press and IRA. Mike Graves, Univ of Minn

References Anderson, R. C. , & Freebody, P. (1983). Reading comprehension and the assessment and acquisition of word knowledge. In B. Hudson (Ed. ), Advances in reading/language research (pp. 231 -256). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Baumann, J. F. , & Kame'enui, E. J. (Eds. ). (2004). Vocabulary instruction: Research to practice. New York: Guilford. Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford. Blachowicz, C. L. Z. , Fisher, P. J. L, Ogle, D. , & Watts-Taffe, S. (2006). Vocabulary: Questions from the classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 524 -539. Blachowicz, C. L. Z. , & Obrochta, C. (2005). Vocabulary visits: Virtual field trips for content vocabulary development. The Reading Teacher, 59, 262 -268. Biemiller, A. (in press). Words worth teaching. Columbus, OH: SRE/Mc. Graw-Hill. Biemiller, A. & Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 44 – 62. Chall, J. S. , & Dale, E. (1995). Readability revisited: The new Dale-Chall readability formula. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. Collins COBUILD new student’s dictionary (3 rd ed. , 2005). Glasglow, Scotland: Harper. Collins. Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 213 -238. Frayer, D. A. , Frederick, W. D. , & Klausmeier, H. J. (1969). A schema for testing the level of concept mastery (Working Paper No. 16). Madison: Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Cognitive Learning. Fry, E. B. , & Kress, J. E. (2006). The reading teacher's book of lists (5 th ed. ). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York: Teachers College Press, IRA, and NCTE. Graves, M. F. (2007). Conceptual and empirical bases for providing struggling readers with multi-faceted and long-term vocabulary instruction. In B. M. Taylor & J. Ysseldyke (Eds. ), Educational perspectives on struggling readers (pp. 55 -83). New York: Teachers College Press.

References Anderson, R. C. , & Freebody, P. (1983). Reading comprehension and the assessment and acquisition of word knowledge. In B. Hudson (Ed. ), Advances in reading/language research (pp. 231 -256). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Baumann, J. F. , & Kame'enui, E. J. (Eds. ). (2004). Vocabulary instruction: Research to practice. New York: Guilford. Beck, Mc. Keown, & Kucan. (2002). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction. New York: Guilford. Blachowicz, C. L. Z. , Fisher, P. J. L, Ogle, D. , & Watts-Taffe, S. (2006). Vocabulary: Questions from the classroom. Reading Research Quarterly, 41, 524 -539. Blachowicz, C. L. Z. , & Obrochta, C. (2005). Vocabulary visits: Virtual field trips for content vocabulary development. The Reading Teacher, 59, 262 -268. Biemiller, A. (in press). Words worth teaching. Columbus, OH: SRE/Mc. Graw-Hill. Biemiller, A. & Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 44 – 62. Chall, J. S. , & Dale, E. (1995). Readability revisited: The new Dale-Chall readability formula. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books. Collins COBUILD new student’s dictionary (3 rd ed. , 2005). Glasglow, Scotland: Harper. Collins. Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 213 -238. Frayer, D. A. , Frederick, W. D. , & Klausmeier, H. J. (1969). A schema for testing the level of concept mastery (Working Paper No. 16). Madison: Wisconsin Research and Development Center for Cognitive Learning. Fry, E. B. , & Kress, J. E. (2006). The reading teacher's book of lists (5 th ed. ). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Graves, M. F. (2006). The vocabulary book: Learning and instruction. New York: Teachers College Press, IRA, and NCTE. Graves, M. F. (2007). Conceptual and empirical bases for providing struggling readers with multi-faceted and long-term vocabulary instruction. In B. M. Taylor & J. Ysseldyke (Eds. ), Educational perspectives on struggling readers (pp. 55 -83). New York: Teachers College Press.

References Graves, M. F. (in press). Teaching individual words: One size does not fit all. New York: Teachers College Press and IRA. Graves, M. F. , & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds. ), What research has to say about reading instruction (3 rd ed. , pp. 140 -165). Newark, DE: IRA. Graves, M. F. , & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2007). Word consciousness comes of age. Unpublished paper. Hart, B. , & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: P. H. Brookes. Hart, B. , & Risley, T. R. (2003, Spring). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, 27 (1), 4 -9. Heimlich, J. E. , & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Hiebert, E. H. (2005). In pursuit of an effective, efficient vocabulary curriculum for elementary students. In E. H. Hiebert & M. L. Kamil (Eds. ), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice (pp. 243 -263). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Heimlich, J. E. , & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Longman Study Dictionary of American English. (2006). Edinburgh Gate, UK: Pearson Education Limited. Pittelman, S. D. , Heimlich, J. E. , Berglund, R. L. , & French, M. P. (1991). Semantic feature analysis: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Sales, G. & Graves, M. F. (2007). The First 4, 000 words. Grant funded by the U. S. Office of Education SBIR division of IES. Stahl, S. A. , & Nagy, W. E. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. White, T. G. , Slater, W. H. , & Graves, M. F. (1989). Yes/No method of vocabulary assessment: Valid for whom and useful for what? S. Mc. Cormick & J. Zutell (Eds. ), Cognitive and social perspectives for literacy research and instruction (pp. 391 -398). Chicago: National Reading Conference.

References Graves, M. F. (in press). Teaching individual words: One size does not fit all. New York: Teachers College Press and IRA. Graves, M. F. , & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2002). The place of word consciousness in a research-based vocabulary program. In S. J. Samuels & A. E. Farstrup (Eds. ), What research has to say about reading instruction (3 rd ed. , pp. 140 -165). Newark, DE: IRA. Graves, M. F. , & Watts-Taffe, S. M. (2007). Word consciousness comes of age. Unpublished paper. Hart, B. , & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore: P. H. Brookes. Hart, B. , & Risley, T. R. (2003, Spring). The early catastrophe: The 30 million word gap by age 3. American Educator, 27 (1), 4 -9. Heimlich, J. E. , & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Hiebert, E. H. (2005). In pursuit of an effective, efficient vocabulary curriculum for elementary students. In E. H. Hiebert & M. L. Kamil (Eds. ), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice (pp. 243 -263). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Heimlich, J. E. , & Pittelman, S. D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Longman Study Dictionary of American English. (2006). Edinburgh Gate, UK: Pearson Education Limited. Pittelman, S. D. , Heimlich, J. E. , Berglund, R. L. , & French, M. P. (1991). Semantic feature analysis: Classroom applications. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Sales, G. & Graves, M. F. (2007). The First 4, 000 words. Grant funded by the U. S. Office of Education SBIR division of IES. Stahl, S. A. , & Nagy, W. E. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. White, T. G. , Slater, W. H. , & Graves, M. F. (1989). Yes/No method of vocabulary assessment: Valid for whom and useful for what? S. Mc. Cormick & J. Zutell (Eds. ), Cognitive and social perspectives for literacy research and instruction (pp. 391 -398). Chicago: National Reading Conference.