4b875fdbe6d02094adb339ceb8e997f3.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 1

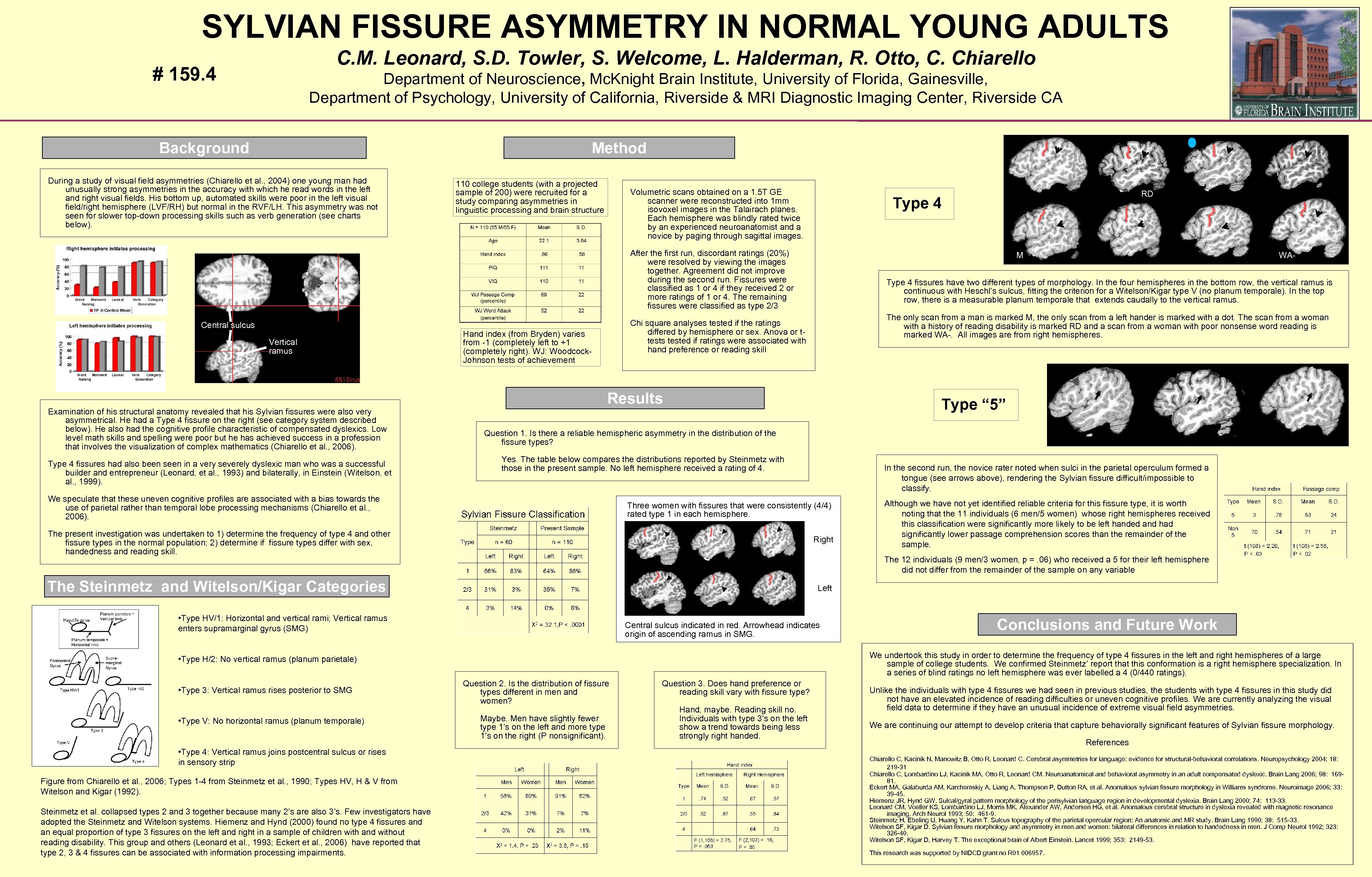

SYLVIAN FISSURE ASYMMETRY IN NORMAL YOUNG ADULTS C. M. Leonard, S. D. Towler, S. Welcome, L. Halderman, R. Otto, C. Chiarello # 159. 4 Department of Neuroscience, Mc. Knight Brain Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, Department of Psychology, University of California, Riverside & MRI Diagnostic Imaging Center, Riverside CA Background Method During a study of visual field asymmetries (Chiarello et al. , 2004) one young man had unusually strong asymmetries in the accuracy with which he read words in the left and right visual fields. His bottom up, automated skills were poor in the left visual field/right hemisphere (LVF/RH) but normal in the RVF/LH. This asymmetry was not seen for slower top-down processing skills such as verb generation (see charts below). 110 college students (with a projected sample of 200) were recruited for a study comparing asymmetries in linguistic processing and brain structure Volumetric scans obtained on a 1. 5 T GE scanner were reconstructed into 1 mm isovoxel images in the Talairach planes. Each hemisphere was blindly rated twice by an experienced neuroanatomist and a novice by paging through sagittal images. Type 4 After the first run, discordant ratings (20%) were resolved by viewing the images together. Agreement did not improve during the second run. Fissures were classified as 1 or 4 if they received 2 or more ratings of 1 or 4. The remaining fissures were classified as type 2/3 Central sulcus Vertical ramus Examination of his structural anatomy revealed that his Sylvian fissures were also very asymmetrical. He had a Type 4 fissure on the right (see category system described below). He also had the cognitive profile characteristic of compensated dyslexics. Low level math skills and spelling were poor but he has achieved success in a profession that involves the visualization of complex mathematics (Chiarello et al. , 2006). Type 4 fissures had also been seen in a very severely dyslexic man who was a successful builder and entrepreneur (Leonard, et al. , 1993) and bilaterally, in Einstein (Witelson, et al. , 1999). M WA- Type 4 fissures have two different types of morphology. In the four hemispheres in the bottom row, the vertical ramus is continuous with Heschl’s sulcus, fitting the criterion for a Witelson/Kigar type V (no planum temporale). In the top row, there is a measurable planum temporale that extends caudally to the vertical ramus. The only scan from a man is marked M, the only scan from a left hander is marked with a dot. The scan from a woman with a history of reading disability is marked RD and a scan from a woman with poor nonsense word reading is marked WA-. All images are from right hemispheres. Chi square analyses tested if the ratings differed by hemisphere or sex. Anova or ttests tested if ratings were associated with hand preference or reading skill Hand index (from Bryden) varies from -1 (completely left to +1 (completely right). WJ: Woodcock. Johnson tests of achievement RD Results Type “ 5” Question 1. Is there a reliable hemispheric asymmetry in the distribution of the fissure types? Yes. The table below compares the distributions reported by Steinmetz with those in the present sample. No left hemisphere received a rating of 4. We speculate that these uneven cognitive profiles are associated with a bias towards the use of parietal rather than temporal lobe processing mechanisms (Chiarello et al. , 2006). In the second run, the novice rater noted when sulci in the parietal operculum formed a tongue (see arrows above), rendering the Sylvian fissure difficult/impossible to classify. Three women with fissures that were consistently (4/4) rated type 1 in each hemisphere. The present investigation was undertaken to 1) determine the frequency of type 4 and other fissure types in the normal population; 2) determine if fissure types differ with sex, handedness and reading skill. Right The Steinmetz and Witelson/Kigar Categories Although we have not yet identified reliable criteria for this fissure type, it is worth noting that the 11 individuals (6 men/5 women) whose right hemispheres received this classification were significantly more likely to be left handed and had significantly lower passage comprehension scores than the remainder of the sample. Left The 12 individuals (9 men/3 women, p =. 06) who received a 5 for their left hemisphere did not differ from the remainder of the sample on any variable • Type HV/1: Horizontal and vertical rami; Vertical ramus enters supramarginal gyrus (SMG) Central sulcus indicated in red. Arrowhead indicates origin of ascending ramus in SMG. We undertook this study in order to determine the frequency of type 4 fissures in the left and right hemispheres of a large sample of college students. We confirmed Steinmetz’ report that this conformation is a right hemisphere specialization. In a series of blind ratings no left hemisphere was ever labelled a 4 (0/440 ratings). • Type H/2: No vertical ramus (planum parietale) • Type 3: Vertical ramus rises posterior to SMG • Type V: No horizontal ramus (planum temporale) • Type 4: Vertical ramus joins postcentral sulcus or rises in sensory strip Figure from Chiarello et al. , 2006; Types 1 -4 from Steinmetz et al. , 1990; Types HV, H & V from Witelson and Kigar (1992). Steinmetz et al. collapsed types 2 and 3 together because many 2’s are also 3’s. Few investigators have adopted the Steinmetz and Witelson systems. Hiemenz and Hynd (2000) found no type 4 fissures and an equal proportion of type 3 fissures on the left and right in a sample of children with and without reading disability. This group and others (Leonard et al. , 1993; Eckert et al. , 2006) have reported that type 2, 3 & 4 fissures can be associated with information processing impairments. Conclusions and Future Work Question 2. Is the distribution of fissure types different in men and women? Maybe. Men have slightly fewer type 1’s on the left and more type 1’s on the right (P nonsignificant). Question 3. Does hand preference or reading skill vary with fissure type? Hand, maybe. Reading skill no. Individuals with type 3’s on the left show a trend towards being less strongly right handed. Unlike the individuals with type 4 fissures we had seen in previous studies, the students with type 4 fissures in this study did not have an elevated incidence of reading difficulties or uneven cognitive profiles. We are currently analyzing the visual field data to determine if they have an unusual incidence of extreme visual field asymmetries. We are continuing our attempt to develop criteria that capture behaviorally significant features of Sylvian fissure morphology. References Chiarello C, Kacinik N, Manowitz B, Otto R, Leonard C. Cerebral asymmetries for language: evidence for structural-behavioral correlations. Neuropsychology 2004; 18: 219 -31 Chiarello C, Lombardino LJ, Kacinik MA, Otto R, Leonard CM. Neuroanatomical and behavioral asymmetry in an adult compensated dyslexic. Brain Lang 2006; 98: 16981. Eckert MA, Galaburda AM, Karchemskiy A, Liang A, Thompson P, Dutton RA, et al. Anomalous sylvian fissure morphology in Williams syndrome. Neuroimage 2006; 33: 39 -45. Hiemenz JR, Hynd GW. Sulcal/gyral pattern morphology of the perisylvian language region in developmental dyslexia. Brain Lang 2000; 74: 113 -33. Leonard CM, Voeller KS, Lombardino LJ, Morris. MK, Alexander AW, Andersen HG, et al. Anomalous cerebral structure in dyslexia revealed with magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol 1993; 50: 461 -9. Steinmetz H, Ebeling U, Huang Y, Kahn T. Sulcus topography of the parietal opercular region: An anatomic and MR study. Brain Lang 1990; 38: 515 -33. Witelson SF, Kigar D. Sylvian fissure morphology and asymmetry in men and women: bilateral differences in relation to handedness in men. J Comp Neurol 1992; 323: 326 -40. Witelson SF, Kigar D, Harvey T. The exceptional brain of Albert Einstein. Lancet 1999; 353: 2149 -53. This research was supported by NIDCD grant no R 01 006957.

SYLVIAN FISSURE ASYMMETRY IN NORMAL YOUNG ADULTS C. M. Leonard, S. D. Towler, S. Welcome, L. Halderman, R. Otto, C. Chiarello # 159. 4 Department of Neuroscience, Mc. Knight Brain Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, Department of Psychology, University of California, Riverside & MRI Diagnostic Imaging Center, Riverside CA Background Method During a study of visual field asymmetries (Chiarello et al. , 2004) one young man had unusually strong asymmetries in the accuracy with which he read words in the left and right visual fields. His bottom up, automated skills were poor in the left visual field/right hemisphere (LVF/RH) but normal in the RVF/LH. This asymmetry was not seen for slower top-down processing skills such as verb generation (see charts below). 110 college students (with a projected sample of 200) were recruited for a study comparing asymmetries in linguistic processing and brain structure Volumetric scans obtained on a 1. 5 T GE scanner were reconstructed into 1 mm isovoxel images in the Talairach planes. Each hemisphere was blindly rated twice by an experienced neuroanatomist and a novice by paging through sagittal images. Type 4 After the first run, discordant ratings (20%) were resolved by viewing the images together. Agreement did not improve during the second run. Fissures were classified as 1 or 4 if they received 2 or more ratings of 1 or 4. The remaining fissures were classified as type 2/3 Central sulcus Vertical ramus Examination of his structural anatomy revealed that his Sylvian fissures were also very asymmetrical. He had a Type 4 fissure on the right (see category system described below). He also had the cognitive profile characteristic of compensated dyslexics. Low level math skills and spelling were poor but he has achieved success in a profession that involves the visualization of complex mathematics (Chiarello et al. , 2006). Type 4 fissures had also been seen in a very severely dyslexic man who was a successful builder and entrepreneur (Leonard, et al. , 1993) and bilaterally, in Einstein (Witelson, et al. , 1999). M WA- Type 4 fissures have two different types of morphology. In the four hemispheres in the bottom row, the vertical ramus is continuous with Heschl’s sulcus, fitting the criterion for a Witelson/Kigar type V (no planum temporale). In the top row, there is a measurable planum temporale that extends caudally to the vertical ramus. The only scan from a man is marked M, the only scan from a left hander is marked with a dot. The scan from a woman with a history of reading disability is marked RD and a scan from a woman with poor nonsense word reading is marked WA-. All images are from right hemispheres. Chi square analyses tested if the ratings differed by hemisphere or sex. Anova or ttests tested if ratings were associated with hand preference or reading skill Hand index (from Bryden) varies from -1 (completely left to +1 (completely right). WJ: Woodcock. Johnson tests of achievement RD Results Type “ 5” Question 1. Is there a reliable hemispheric asymmetry in the distribution of the fissure types? Yes. The table below compares the distributions reported by Steinmetz with those in the present sample. No left hemisphere received a rating of 4. We speculate that these uneven cognitive profiles are associated with a bias towards the use of parietal rather than temporal lobe processing mechanisms (Chiarello et al. , 2006). In the second run, the novice rater noted when sulci in the parietal operculum formed a tongue (see arrows above), rendering the Sylvian fissure difficult/impossible to classify. Three women with fissures that were consistently (4/4) rated type 1 in each hemisphere. The present investigation was undertaken to 1) determine the frequency of type 4 and other fissure types in the normal population; 2) determine if fissure types differ with sex, handedness and reading skill. Right The Steinmetz and Witelson/Kigar Categories Although we have not yet identified reliable criteria for this fissure type, it is worth noting that the 11 individuals (6 men/5 women) whose right hemispheres received this classification were significantly more likely to be left handed and had significantly lower passage comprehension scores than the remainder of the sample. Left The 12 individuals (9 men/3 women, p =. 06) who received a 5 for their left hemisphere did not differ from the remainder of the sample on any variable • Type HV/1: Horizontal and vertical rami; Vertical ramus enters supramarginal gyrus (SMG) Central sulcus indicated in red. Arrowhead indicates origin of ascending ramus in SMG. We undertook this study in order to determine the frequency of type 4 fissures in the left and right hemispheres of a large sample of college students. We confirmed Steinmetz’ report that this conformation is a right hemisphere specialization. In a series of blind ratings no left hemisphere was ever labelled a 4 (0/440 ratings). • Type H/2: No vertical ramus (planum parietale) • Type 3: Vertical ramus rises posterior to SMG • Type V: No horizontal ramus (planum temporale) • Type 4: Vertical ramus joins postcentral sulcus or rises in sensory strip Figure from Chiarello et al. , 2006; Types 1 -4 from Steinmetz et al. , 1990; Types HV, H & V from Witelson and Kigar (1992). Steinmetz et al. collapsed types 2 and 3 together because many 2’s are also 3’s. Few investigators have adopted the Steinmetz and Witelson systems. Hiemenz and Hynd (2000) found no type 4 fissures and an equal proportion of type 3 fissures on the left and right in a sample of children with and without reading disability. This group and others (Leonard et al. , 1993; Eckert et al. , 2006) have reported that type 2, 3 & 4 fissures can be associated with information processing impairments. Conclusions and Future Work Question 2. Is the distribution of fissure types different in men and women? Maybe. Men have slightly fewer type 1’s on the left and more type 1’s on the right (P nonsignificant). Question 3. Does hand preference or reading skill vary with fissure type? Hand, maybe. Reading skill no. Individuals with type 3’s on the left show a trend towards being less strongly right handed. Unlike the individuals with type 4 fissures we had seen in previous studies, the students with type 4 fissures in this study did not have an elevated incidence of reading difficulties or uneven cognitive profiles. We are currently analyzing the visual field data to determine if they have an unusual incidence of extreme visual field asymmetries. We are continuing our attempt to develop criteria that capture behaviorally significant features of Sylvian fissure morphology. References Chiarello C, Kacinik N, Manowitz B, Otto R, Leonard C. Cerebral asymmetries for language: evidence for structural-behavioral correlations. Neuropsychology 2004; 18: 219 -31 Chiarello C, Lombardino LJ, Kacinik MA, Otto R, Leonard CM. Neuroanatomical and behavioral asymmetry in an adult compensated dyslexic. Brain Lang 2006; 98: 16981. Eckert MA, Galaburda AM, Karchemskiy A, Liang A, Thompson P, Dutton RA, et al. Anomalous sylvian fissure morphology in Williams syndrome. Neuroimage 2006; 33: 39 -45. Hiemenz JR, Hynd GW. Sulcal/gyral pattern morphology of the perisylvian language region in developmental dyslexia. Brain Lang 2000; 74: 113 -33. Leonard CM, Voeller KS, Lombardino LJ, Morris. MK, Alexander AW, Andersen HG, et al. Anomalous cerebral structure in dyslexia revealed with magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol 1993; 50: 461 -9. Steinmetz H, Ebeling U, Huang Y, Kahn T. Sulcus topography of the parietal opercular region: An anatomic and MR study. Brain Lang 1990; 38: 515 -33. Witelson SF, Kigar D. Sylvian fissure morphology and asymmetry in men and women: bilateral differences in relation to handedness in men. J Comp Neurol 1992; 323: 326 -40. Witelson SF, Kigar D, Harvey T. The exceptional brain of Albert Einstein. Lancet 1999; 353: 2149 -53. This research was supported by NIDCD grant no R 01 006957.