Презентация История UK .ppt

- Количество слайдов: 98

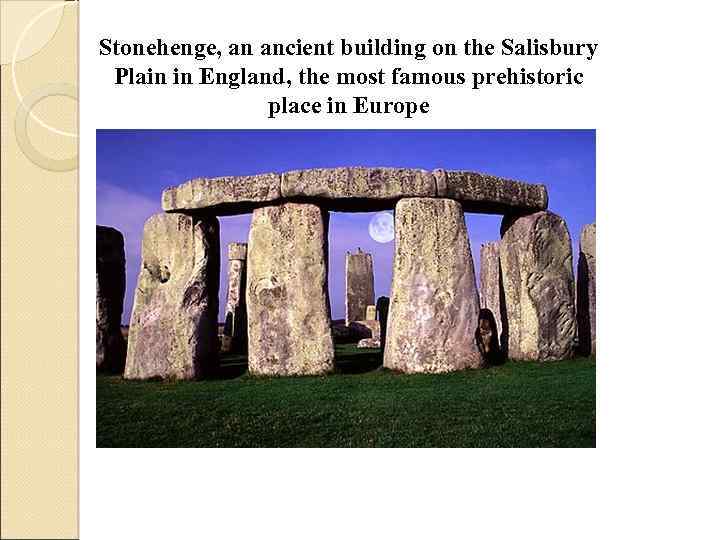

Stonehenge, an ancient building on the Salisbury Plain in England, the most famous prehistoric place in Europe

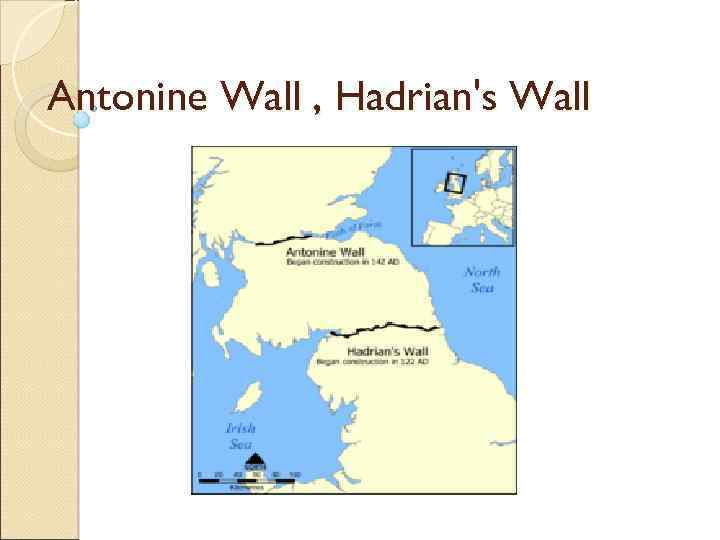

Antonine Wall , Hadrian's Wall

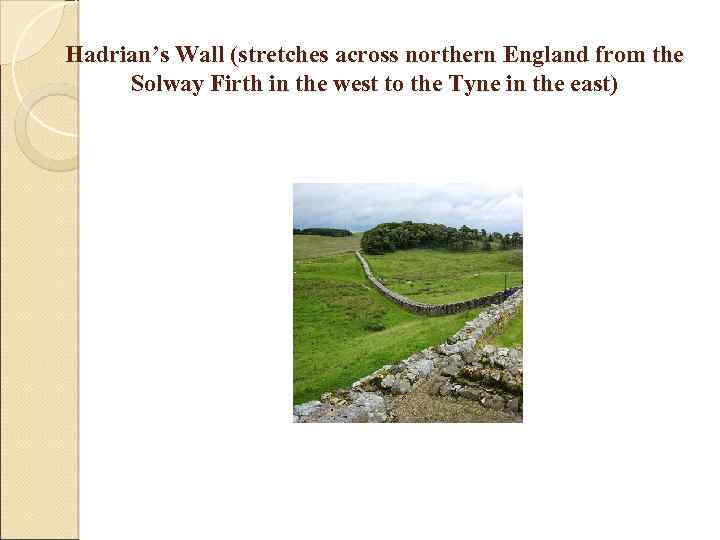

Hadrian’s Wall (stretches across northern England from the Solway Firth in the west to the Tyne in the east)

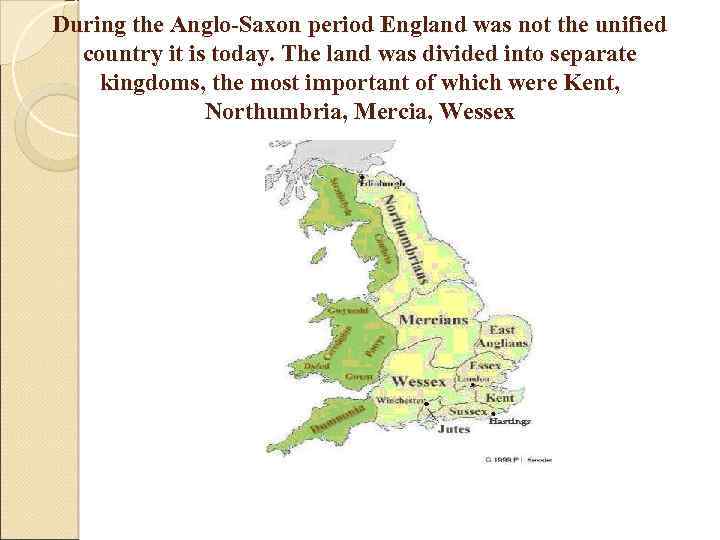

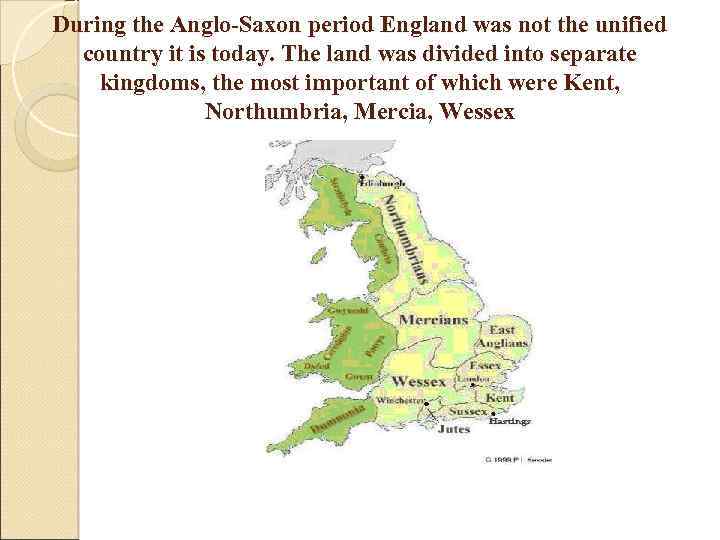

During the Anglo-Saxon period England was not the unified country it is today. The land was divided into separate kingdoms, the most important of which were Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex

King Alfred the Great (849 – 899) is known for his defence of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms against the Vikings (Danes)

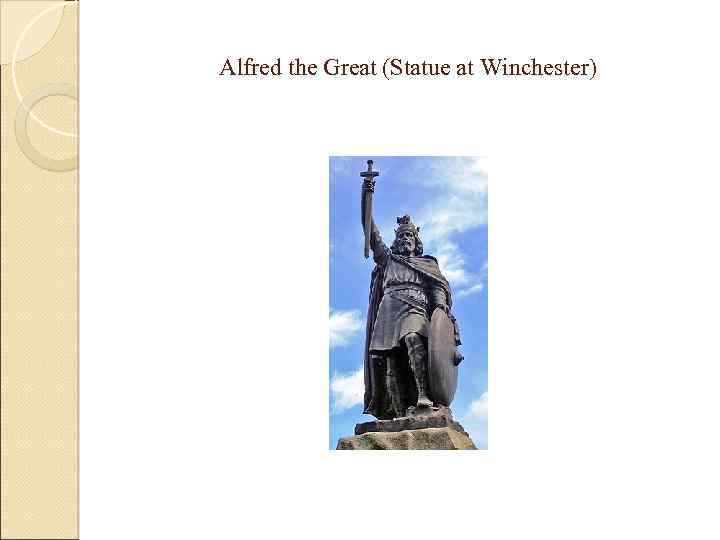

Alfred the Great (Statue at Winchester)

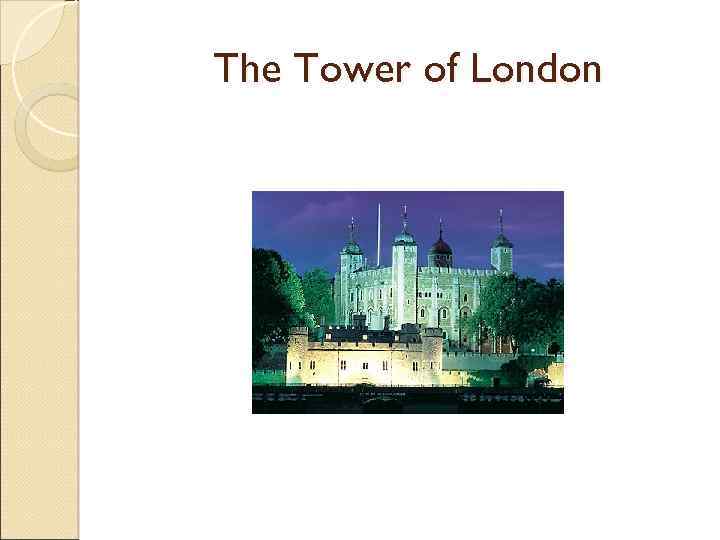

The Tower of London

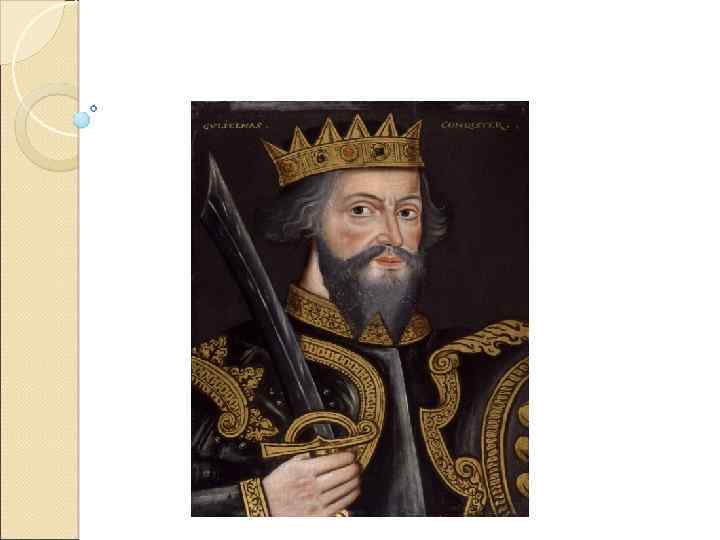

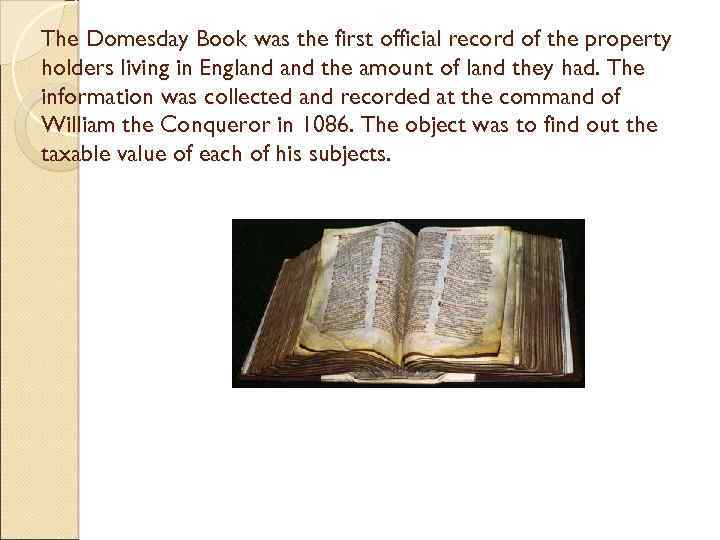

The Domesday Book was the first official record of the property holders living in England the amount of land they had. The information was collected and recorded at the command of William the Conqueror in 1086. The object was to find out the taxable value of each of his subjects.

During the Anglo-Saxon period England was not the unified country it is today. The land was divided into separate kingdoms, the most important of which were Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex

King Alfred the Great (849 – 899)

Alfred the Great (Statue at Winchester)

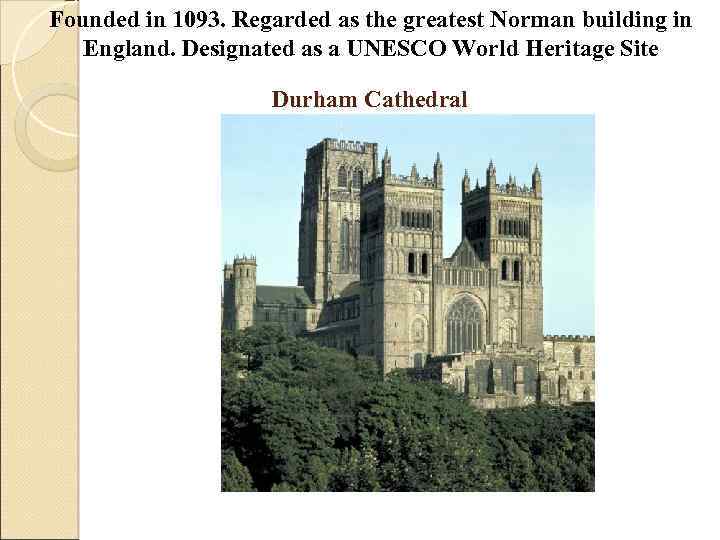

Founded in 1093. Regarded as the greatest Norman building in England. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site Durham Cathedral

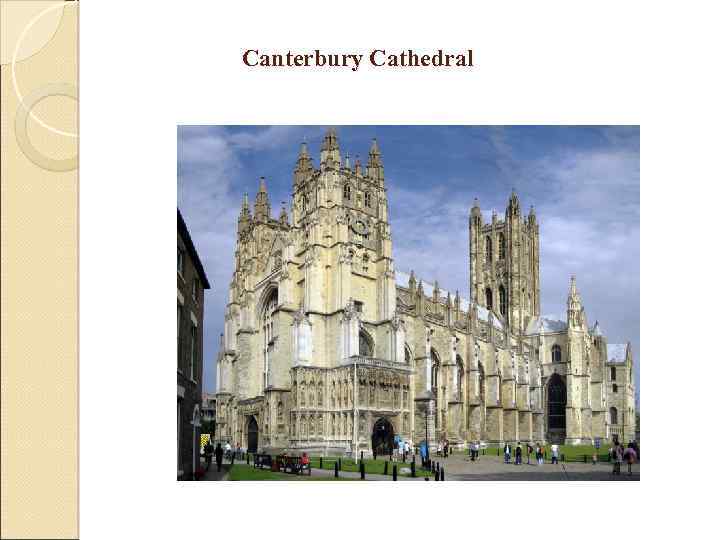

Canterbury Cathedral

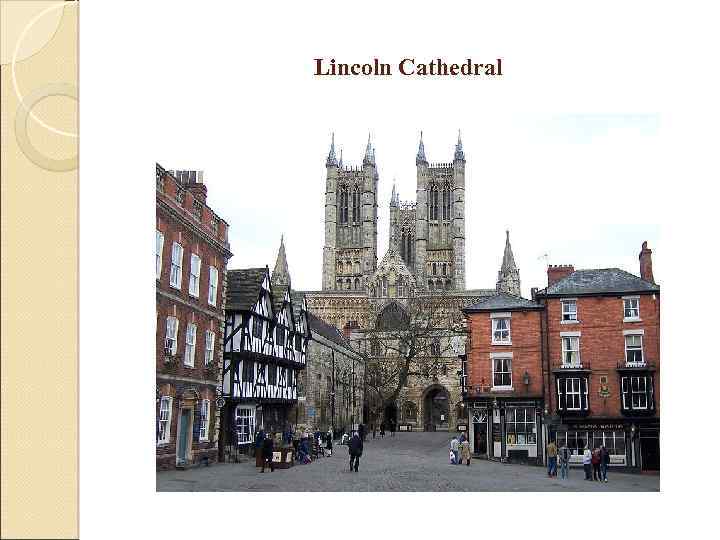

Lincoln Cathedral

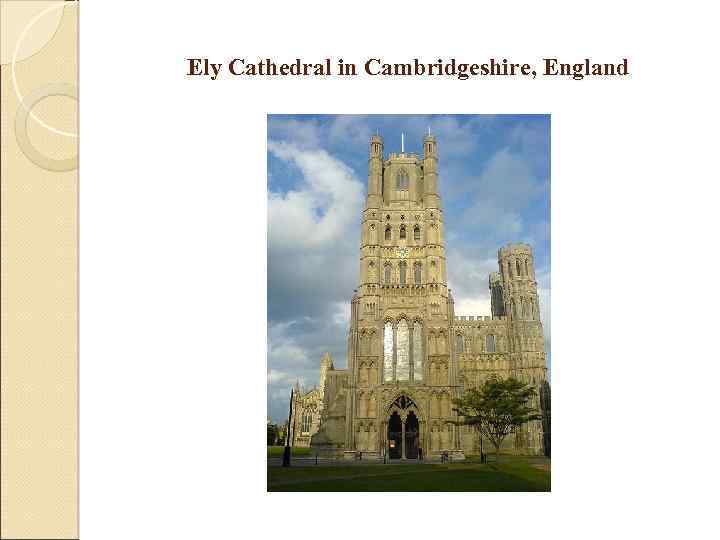

Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, England

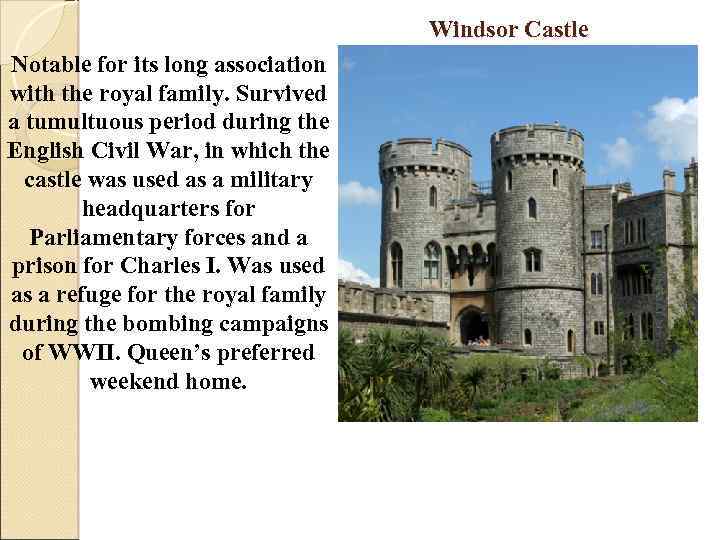

Windsor Castle Notable for its long association with the royal family. Survived a tumultuous period during the English Civil War, in which the castle was used as a military headquarters for Parliamentary forces and a prison for Charles I. Was used as a refuge for the royal family during the bombing campaigns of WWII. Queen’s preferred weekend home.

Henry II (1154 – 1189) spent most of his time travelling because it encouraged people to be loyal to the king. Was a man of a fiery temper, very intelligent, he made several important legal and military reforms. Henry II introduced royal law courts, the jury system: the investigation was carried out by 12 ordinary people. The system of common law, based on the decisions of the king's judges appeared. Common law reflected the customs and instincts of the English people.

Richard I (king of England from 1189 to 1199)

John the Lackland(1199 – 1216)

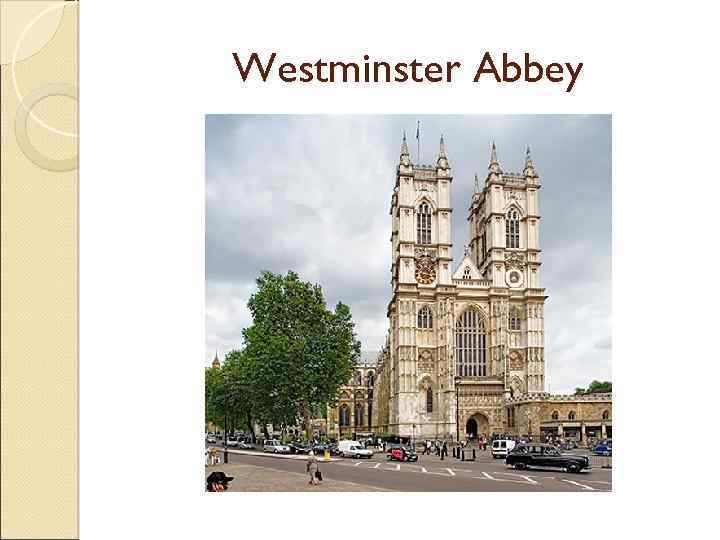

Westminster Abbey

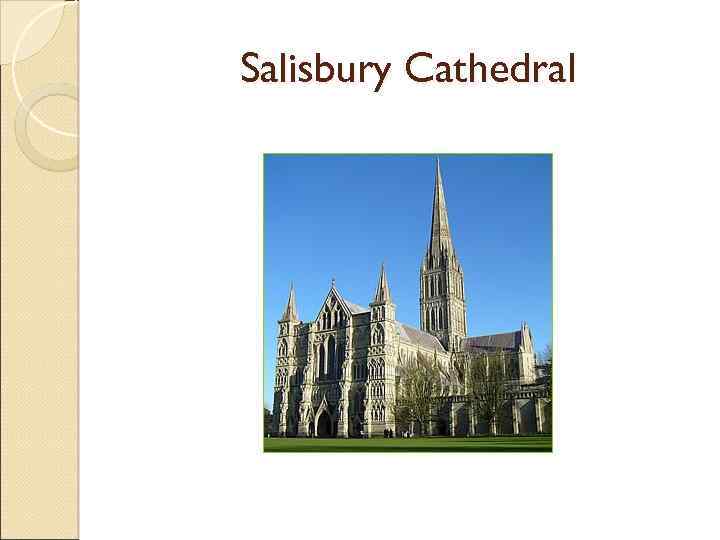

Salisbury Cathedral

Edward III ascended the throne in 1327 – 1377 , The Black Prince

Peasants’ Revolts (1381) To continue the war with France the English king needed money. Ordinary people had to pay new taxes: England was being defeated when a 14 -year-old Richard II became king. The main grievance of peasants was the Statute of Laboureres (1351) which attempted to fix maximum wages during the labour shortage following the Black Death.

The discontent produced Peasants’ Revolts (Wat Tyler). The rebels of Essex and Kent marched towards London. Richard met them and promised to fulfill their requirements but he did not do it. Henry Bolingbroke, Richard’s cousin forced Richard to abdicate and took his throne as King Henry IV (The House of Lancaster).

The Wars of the Roses A conflict between the royal houses of Lancaster and York for the English throne. The supposed badges of the contending parties are the white rose of York and the red of Lancaster. Both houses claimed the throne through descent from the sons of Edward III. ).

These wars (1455 -85) distracted the country at intervals without disturbing its social life. The conflict was brought to an end by the victory of the Lancastrian heir, Henry Tudor, over Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485.

Richard III Henry VII (1485 – 1509) Henry VIII (1509 – 1547)

The Tudors In 1485 Henry Tudor became King Henry VII of England. He was determined to make monarchy rich and strong. Henry did not fight wars. He was careful to keep the friendship of the merchant class. He created new nobility from among them. He also encouraged the spread of education by importing French scholars.

Reformation in England The enormous task of carrying out the Reformation in England was accomplished by Thomas Cromwell, the king’s chief minister. He arranged for Parliament to pass statutes which swept away the power of the papacy in England vested it in the Crown instead.

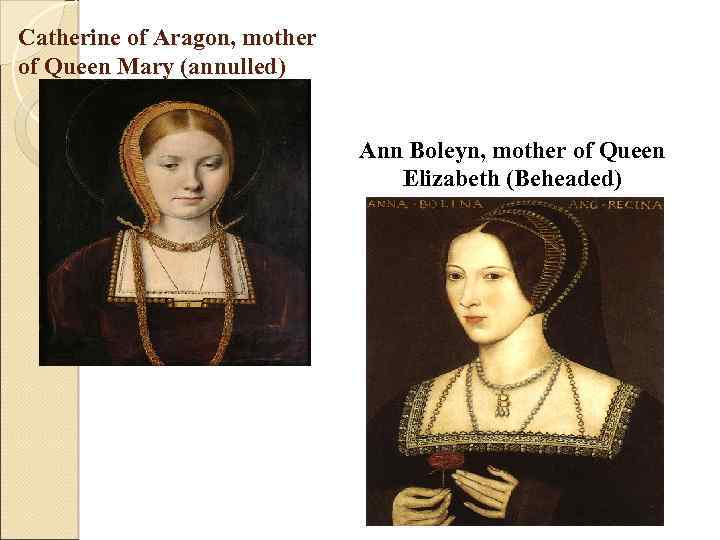

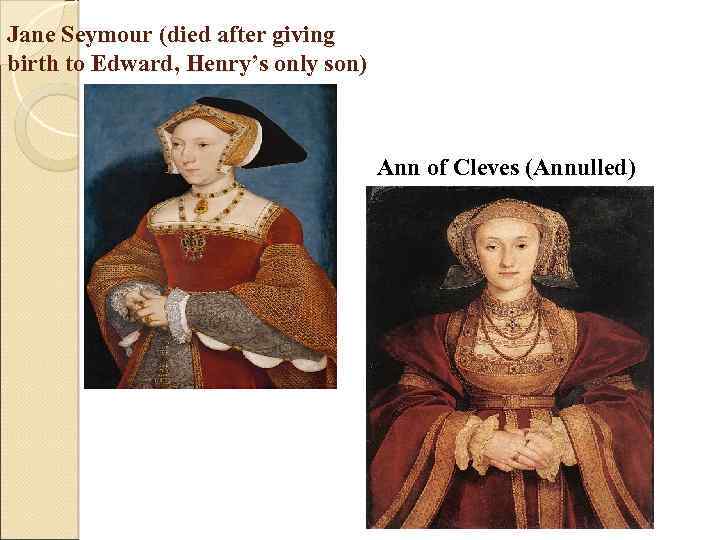

Henry’s marriage with Catherine of Aragon was pronounced null and he got married to Ann Boleyn who was crowned as Queen of England, but Henry was bitterly disappointed at the birth of Princess Elizabeth. Henry was declared supreme head of the Church of England in 1534, and all the payments made to the pope now went to the Crown. Ann Boleyn, accused of adultery was beheaded. The only son of Henry VIII and his third wife Jane Seymour was Edward VI.

Catherine of Aragon, mother of Queen Mary (annulled) Ann Boleyn, mother of Queen Elizabeth (Beheaded)

Jane Seymour (died after giving birth to Edward, Henry’s only son) Ann of Cleves (Annulled)

Catherine Howard (Beheaded) Catherine Parr (Survived)

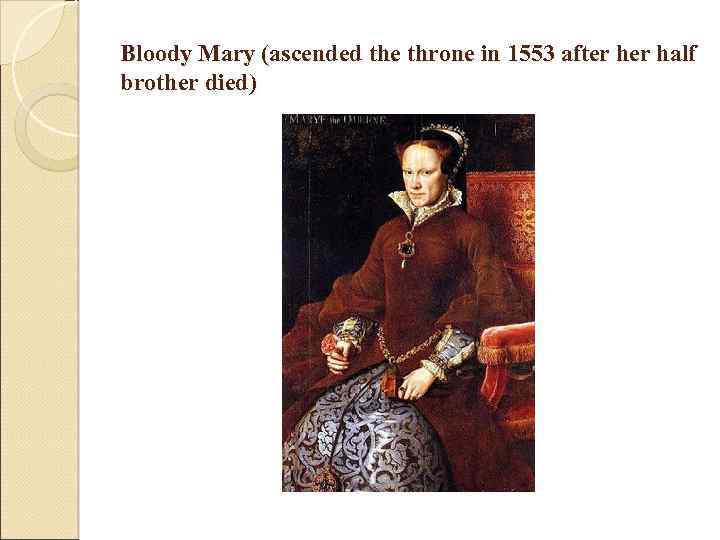

The only son of Henry VII, Edward VI (was crowned at the age of 9 in 1547) Bloody Mary (ascended the throne in 1553 after half brother died)

After King Edward died, his half-sister Mary became queen. She was a devout Roman Catholic and tried to bring England back to the Roman Catholic Church. Mary became known as “Bloody Mary”. More than 300 protestant were burned at the stake during her reign for their beliefs (all high-ranking protestant clergymen).

Bloody Mary (ascended the throne in 1553 after half brother died)

Conclusion During Henry VIII’s 38 -year reign, England experienced profound changes. Despite his despotic tendencies, Henry VIII was not a tyrant. He ruled with the general consent and with no standing army to back up his authority. Parliament was a vital part of his governmental procedure, and he summoned it far more regularly than his father had.

Elizabeth I (Glorianna, Good Queen Bess, the Virgin Queen) Elizabeth I (1558 – 1603) Mary, Queen of Scots (1542 – 1587)

Elizabethan Age Enjoyed enormous popularity during her life and became an even greater legend after her death. Firmly established Protestantism in England, encouraged English enterprise and commerce. Renewed voyages across the Atlantic and around the world (Sir Francis Drake, Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Sir Walter Raleigh).

Some English settlements were established in North America. Voyages searching for a Northeast Passage opened up direct sea routes to Russia and Persia. From 1580 direct trade with Turkey and the Middle East began

Defended the nation against the powerful Spanish naval force (the Spanish Armada). A long war between England Spain from 1585 to 1604 began. Spain was determined to keep other Europeans out of the New World. The defeat of the Spanish Armada of 1588 increased the self-confidence of the Elizabethans and gave a patriotic inspiration to the brilliant Elizabethan Age. This was expressed creatively in literature and the arts, in a general cultural renaissance.

Elizabeth I was the last of the Tudor monarchs, never marrying or producing an heir, and was succeeded by her cousin, James VI of Scotland.

The Civil Wars (1642 – 1651) The long-term causes of the war was the growing wealth of the middle class (gentry and merchants), who made up a majority in the House of Commons and demanded a larger influence upon the government, and the insufficiency of the king’s finances, which made him dependent on the Commons whenever he was involved in the foreign wars. The Commons disliked the way Charles I raised new taxes without their consent.

Oliver Cromwell led major military campaigns to establish English control over Ireland (1649 -50) and then Scotland (1650 -51). In the summer of 1650 before embarking for Scotland, Cromwell had been appointed lord general (commander-inchief) of all the parliamentary forces.

The Royalists became known as Cavaliers. The supporters of Parliament came to be called Roundheads (hair cut short to fit a steel helmet). The Royalists were superior in cavalry until the formation of Parliament’s New Model Army. Parliamentary forces won because they were able to finance a professional army.

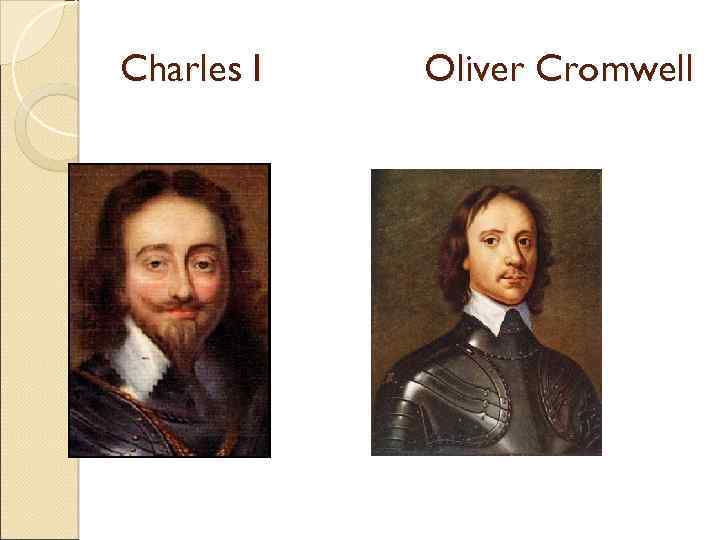

Charles I Oliver Cromwell

England, Scotland, and Ireland became a republic called first the Commonwealth, later the Protectorate, with Cromwell as Lord Protector. In 1657, Parliament wanted to give Cromwell the title of king, but he refused it. The death of the Protector, in his 59 th year threw all his achievement into disarray. His son Richard, named as his successor, was well -intentioned but not of his father’s calibre. The army began to disintegrate into factions.

The parliament called by Richard was equally riven by contrary opinions, with many royalist sympathisers. He dissolved it in April 1659 and resigned his post. Charles II was invited to assume his father’s English crown.

Charles II

James II

England, Scotland, and Ireland became a republic called first the Commonwealth, later the Protectorate, with Cromwell as Lord Protector. In 1657, Parliament wanted to give Cromwell the title of king, but he refused it. His son Richard succeeded him. The army began to disintegrate into factions. The parliament called by Richard was equally riven by contrary opinions, with many royalist sympathisers. He dissolved it in April 1659 and resigned his post. Charles II was invited to assume his father’s English crown.

The Glorious Revolution and the Bill of Rights It was a strange revolution, and the English took some pride in its strangeness. In England (though not in Scotland or Ireland) it was almost bloodless. And after it, apart from the provisions of the Bill of Rights, virtually nothing appeared to have changed. No grand new constitutional settlement was enacted, binding the king or extending the role of parliament. But from then on it was accepted that the monarch of England ruled through parliament, that parliament made law and that the king was under, not above, the law.

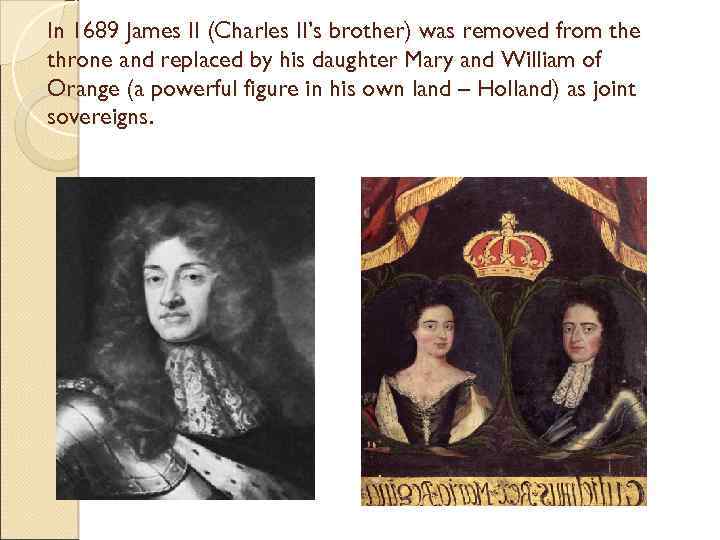

In 1689 James II (Charles II’s brother) was removed from the throne and replaced by his daughter Mary and William of Orange (a powerful figure in his own land – Holland) as joint sovereigns.

James had become increasingly unpopular on account of his unconstitutional behaviour and Catholicism. Seven prominent politicians, plotted to invite the protestant William to become king. William and Mary accepted a new constitutional settlement, the Bill of Rights (1689). The Bill of Rights was an act of Parliament which established Parliament as the primary governing body of the country. The joint sovereigns had to fight Jacobite armies to secure their crown in Scotland Ireland. In July 1690 the defeat of James II and his French allies by William III at the battle of Boyne (it took its name from the river Boyne) in Ireland confirmed the new situation.

Georgian England When the century ended in 1800, although Britain was still at war with France, she was a world power, rich and united. In fact, it was in the 18 th century that Britain laid the foundations for her worldwide empire. They call the 18 th century the Georgian period simply because for most of that hundred years Britain was ruled by kings who were named George, but the adjective has also come to epitomise (воплощать) a culture.

Georgian England was economically prosperous, enterprising and sturdily (сильно, крепко) self-sufficient; its policies were vigorous, but essentially peaceable; its ruling aristocracy was preoccupied with the idea of liberty; its architecture, literature and art were all suffused (заливать) with ideas derived from classical antiquity (античность); but its religion was a stoutly (крепко, прочно) Protestant, rather secular Christianity.

Education was highly valued even though the schools were highly valued even though the universities were in a torpid (бездеятельный, апатичный) state. There was a remarkable growth in learned societies, such as the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of Antiquaries, and the British Academy. Queen Ann’s reign (1702 – 1704) was marked by brilliant military successes against France, above all the stunning victory at Blenheim in 1704 (the war of the Spanish succesion), and by a growth in the country’s overseas trade, which laid the foundation for subsequent economic success.

None of Ann’s children survived her and, on her death, the Crown passed to her nearest Protestant relative, George, Elector of Hanover. So a German dynasty came to reign in Britain, both to placate (успокаивать) popular distrust of Roman Catholics and in accordance with the terms of the Act of Settlement of 1701 – the beginnings of constitutional monarchy.

Under the Act of Settlement of 1701, if Queen Ann failed to produce an heir, the succession was to be limited to another Protestant Stuart line; all future sovereigns were to be members of the Church of England. The Act was subtitled “An Act for better securing the rights and liberties of the subject”.

George I (1714 – 1727) and his son George II (1727 -1760) thought of themselves primarily as German rulers, and they spent as much time as they could at home in Hanover; George I, indeed, spoke little English. They relied largely on the aristocracy of Britain to manage affairs for them, a policy which seemed to be justified by successful wars, imperial expansion, and a rapid increase in national prosperity.

Between 1721 – 1742 Sir Robert Walpole accumulated so much power as First Lord of the Treasury that he was recognized at the time as head of the king’s government and has since been described as the first Prime Minister. George II was the last British king to lead his own troops into battle. On June 27 1743, he defeated a French army at the battle of Dettingen.

George III came to the throne in 1760. Was keenly British, willing to take sides at a time of rising difficulties both at home and abroad. In George III’s later years, however, as the nation rallied together (собраться) in struggle against revolutionary and Napoleonic France, the monarchy emerged as a symbol, not so much of national leadership, as of national unity. Ironically, during this period of growing royal popularity, the king suffered from increasingly severe bouts of insanity.

2. Political Activity Political activity in the 18 th-century Britain was intense, unscrupulous and frequently savage. The two main political groupings known as Whigs and Tories respectively, had much in common. Essentially, they were rival aristocratic factions, jostling each other ruthlessly for control of the source of political influence – the right to make effective appointments to profitable posts under the Crown. Those who could operate the system successfully held the levers of power.

Parliament provided arena where this power struggle took place. The party leaders were generally to be found in the House of Lords, which was in some respects, therefore more important than the House of Commons. Elections to the Commons were infrequent- a seven-year rule applied for much of the century – and few people were qualified to vote.

“Patronage” – the giving or withholding of favours, particularly appointments to offices under the Crown – and outright bribery were the main considerations in securing political results, at all levels of the system. In short, 18 th-century Britain was far from being a democracy. Rather, it enjoyed a partially representative system of government.

3. An economic explosion The British economy was transformed in the 18 century, and with it the lifestyles and expectations of the inhabitants of the British Isles. All of Britain’s subsequent prosperity has rested, in fact, on the foundations laid in the Georgian period.

Population growth began in the early part of the century, when landowners enriched by new sources of capital, some of it won from foreign trade, were able to improve their farms sufficiently to feed a small but statistically crucial increase in the child population. This expanding population both inflated demand for industrial produce and, by its labour made possible a startling growth in national productivity.

Finally, both the raw materials for industry and the finished goods which resulted were moved around the country with increasing ease and speed as the growth enabled enterprising individuals to build networks of canals and roads. In rough figures, Britain’s population rose from 5. 8 mln in 1700, to 10. 5 mln in 1800; her agricultural productivity increased by half, her overseas trade quadrupled, and her industrial capacity increased five times, while 2, 300 miles of canals and about 22, 000 miles (35, 000 km. ) of roads were constructed.

4. Empire The British Empire in the 18 th century was based on sea-borne trade. Colonies, to the merchant adventurers of 18 th century London and Bristol, were simply sources of goods – exotic products such as sugar from the West Indies, tobacco from Virginia, spices from the East Indies, furs from Canada or tea from China; or items of value to be had in trade with the locals – pearls and precious stones, silks and porcelain.

Only the Thirteen Colonies that later became the founding elements of the USA departed from the norm by developing increasingly as colonies of settlement; significantly they were the first to break away from the mother country, in the war of American Independence (1775 – 1783).

Britain’s great rival in the competition for world trade was France; the victim of both was Spain, an ailing power. It was a triangular relationship, which took a coldly diplomatic, formally military shape in successive European wars, particularly the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 -1714), the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718 -1720) and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740 1748).

In a less organized manner, hostilities broke out in fierce violence on all the oceans and distant coastlines of the world, at erratic times throughout the century; the Seven Years’ War, fought against the French in North America between 1756 and 1763, is an example of one such conflict.

The Industrial revolution The main changes involved in the Industrial Revolution included the following: the use of new basic materials, chiefly iron and steel; the use of new energy sources: coal, steam engine, petroleum; the invention of new machines, such as the spinning jenny and the power loom; new organization of work known as the factory system; important developments in transportation and communication;

deposits of coal and iron, the two natural resources on which early industrialization largely depended Educational and political privileges, which once had belonged to the upper class, spread to the growing middle class. People in business made huge amounts of money, the old aristocrats lost much of their power and influence.

Some workers were displaced by machines, others found new job opportunities working with machines. Many workers went on strike. In the riots, unemployed workers destroyed machinery trying to take revenge on the employers they blamed for depriving them of jobs. In 1769, Parliament passed a law making the destruction of machinery punishable by death. In 1811, organised bands of workers called Luddites began rioting against textile machines.

In 1783 Britain recognised the independence of the United States of America. Ten years later Britain was engaged in war with Napoleonic France. British government found it extremely difficult to defeat France because of its overwhelming military superiority on land. In October 1805, Nelson defeated the French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar, thereby preventing an invasion of Britain.

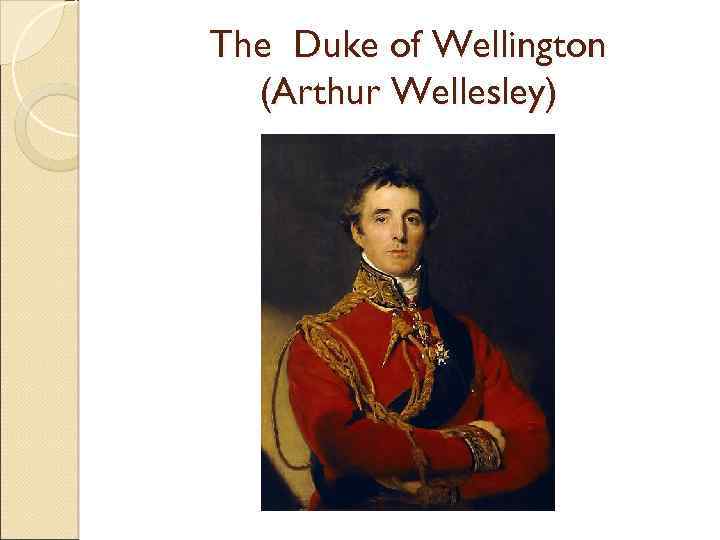

Napoleon invaded Spain. The war began to turn in Britain’s favour in 1809, because of Napoleon’s strategic mistakes. When the Spanish rebelled against French rule, substantial British armed forces were dispatched to assist them under the command of Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington. After Napoleon’s return to power, Wellington defeated him with the aid of Prussian troops at Waterloo on 18 June, 1815. After Waterloo, the Great Duke, as he was subsequently known, was drawn into British politics.

The Duke of Wellington (Arthur Wellesley)

Famous quotes The only thing I’m afraid of is fear. Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won. Being born in a stable doesn’t make one a horse.

The 19 th century A feeling very generally exists that the condition and disposition of the working classes is a rather ominous matter at present; that something ought to be said and done in regard to it. Thomas Carlyle 1839

The problem to which Carlyle referred arose from both economic and political causes. A major economic depression between 1837 and 1842 The consequences of the Reform Act (1832)

Working-class men who had campaigned for the vote but had been deliberately excluded from the Reform Act now felt betrayed. Since most of them rented their houses at 4 and 8 pounds per year they semed most unlikely to qualify for the new 10 pounds householder franchise (право голоса для съёмщика квартир)

Workingmen, especially in the North, were antagonised by the new poor law introduced by the whigs in 1834. Those who framed the legislation of 1834 intended to introduce a radical change. In particular they wished to end the control exercised by local squires, whom they blamed for demoralising the poor by their generous payments based on the current price of bread

Instead , those who received poor relief were to be required to enter a workhouse rather than receive help outside. This reflected a fundamental belief that the poor tended to be idle and irresponsible, and thus in need of a stimulus to live industrious lives. The new system had been designed to deal with the southern agricultural counties, which suffered from low wages and seasonal unemployment.

When applied to the North and the Midlands during 1836 the new poor law encountered massive resistance from all concerned. In these areas the workers saw the new poor law as a means of forcing them to accept lower wages and longer hours. The depression of 1837 – 42 had the effect of undermining the new system throughout the North, for the workhouse test was irrelevant when thousands of men were being thrown out of work.

However, the protests collapsed fairly quickly, partly because the discontent was diverted into Chartism from 1839 onwards. Also, the new poor law was never applied as the legislators had intended. In the south the poor law guardians, who often felt sympathetic towards the agricultural labourers, resorted to ways of paying extra poor relief. In the North the elected guardians frequently ignored their instructions and continued to offer outdoor relief.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the Victorian poor law made no impact. Expenditure on relief fell by 30 per cent per head of population between 1832 and 1844. Workhouses gradually appeared throughout the country. The working class regarded them with fear and loathing. Conditions inside the workhouse were both severe and humiliating

Chartism Was the most significant working-class movement in this period. Between 1837 and 1848 it mobilised hundreds of thousands of people in violent protest. It reached its height after 1838 when bread prices rose and Britain suffered the worst depression of the century.

Academic studies revealed that it was weaker in large towns like Leeds or Manchester where the more varied economy made it easier for men to find employment. It often reached its peak in smaller industrial towns and villages where the workers were dependent on a single industry for their livelihood. Collapsed in 1848

Mid-Victorian Britain An era of unusual economic growth and social stability. While other European states experienced outbreaks of revolution the British people appeared to accept their political system as legitimate and to take satisfaction in their economic achievements. Contrary to the expectations of Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, the English revolution failed to materialise.

Contemporary Victorians had their own explanations. The Whig view, as expressed by Macaulay, the famous historian, held that Britain had already undergone her revolution in the 17 th century, and achieved an open, liberal, representative system of government. Other mid-Victorians convinced themselves that there was something distinctive in the English national character, perhaps influenced by the climate, that fostered a practical non-ideological, industrious temperament.

A more sophisticated version of this view was articulated by Walter Bagehot in his book The English Constitution (1867), in which he argued that on the whole people accepted the social hierarchy and consented to be governed by their superiors. However modern historians have been less convinced by these ideas.

Some have simply explained the relative stability in terms of contingencies (cлучайность) notably the skill of the working class making concessions, so as to deflate threat of the revolution. Others stress the nature of class relations. In particular, the middle class played a crucial role in maintaining social and political stability by its moral influence both on the workers and the aristocracy

Moreover, the middle class was the engine that generated the prosperity of the mid-victorian Britain and thus made possible the equilibrium of the era. All cvlasses could participate in economic success, none really dominated. At times the middle class collaborated with the workers to push the aristocracy into reforms. When threatened by Chartism, the middle class took the side of the aristocracy to defend order and property

British society in decline (1873 – 1902) If the 1850 s and 60 s may be regarded as the hey-day of Victorian Britain, then the 1870 s mark the beginning of decline. Britain’s manufacturing superiority began to be undermined by American and German competition.

The real problem lay in the concentration of the economy in a narrow range of industries that had been the base for the earlier industrial revolution (cotton, metal goods). Where the economy failed in the late 19 th century was in exploiting the fast growing industries on which the next of industrilisation was to be based: cemicals, motor cars, machine tools, electricity

Queen Victoria Albert, Prince Consort

Презентация История UK .ppt