ce20590c34c42a0d7b1fe31c439a0853.ppt

- Количество слайдов: 26

Steve Wright, Kirsty Williamson, Jen Sullivan ITNR, Caulfield School of Information Technology Vivienne Bernath Monash University Library Research students’ understanding of information literacy www. monash. edu. au

Steve Wright, Kirsty Williamson, Jen Sullivan ITNR, Caulfield School of Information Technology Vivienne Bernath Monash University Library Research students’ understanding of information literacy www. monash. edu. au

Overview 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Introduction Literature review Philosophy and method Findings Conclusion Discussion www. monash. edu. au 2

Overview 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Introduction Literature review Philosophy and method Findings Conclusion Discussion www. monash. edu. au 2

1. Introduction: Information literacy Here is one common definition: ‘the ability to access, evaluate, and apply information effectively to situations requiring decision making, problem solving, or the acquisition of knowledge’ (Young & Harmony, 1999, p. 1) www. monash. edu. au 3

1. Introduction: Information literacy Here is one common definition: ‘the ability to access, evaluate, and apply information effectively to situations requiring decision making, problem solving, or the acquisition of knowledge’ (Young & Harmony, 1999, p. 1) www. monash. edu. au 3

1. Introduction: Themes Our project addressed research students’ – information needs – understanding of the scope and appropriateness of a variety of information sources – selection of search strategies and tools – views of the convenience and currency of access provided by electronic media – evaluation of information sources: reliability and authority – personal information management tools and strategies. www. monash. edu. au 4

1. Introduction: Themes Our project addressed research students’ – information needs – understanding of the scope and appropriateness of a variety of information sources – selection of search strategies and tools – views of the convenience and currency of access provided by electronic media – evaluation of information sources: reliability and authority – personal information management tools and strategies. www. monash. edu. au 4

2. Literature review ‘Ph. D students have specific needs which need to be fulfilled to enable them to manage their personal research information satisfactorily’ Pilerot (2004: 92) Macauley (2000, 2001) suggests reintermediation of librarians in supportive roles for postgraduate students’ information literacy needs. www. monash. edu. au 5

2. Literature review ‘Ph. D students have specific needs which need to be fulfilled to enable them to manage their personal research information satisfactorily’ Pilerot (2004: 92) Macauley (2000, 2001) suggests reintermediation of librarians in supportive roles for postgraduate students’ information literacy needs. www. monash. edu. au 5

3. Philosophical framework Interpretivist / constructivist framework, including grounded theory concepts Opportunity to explore and generate ideas serendipitous findings Elicits rich-picture, in-depth perspectives Represents multiple voices of participants. www. monash. edu. au 6

3. Philosophical framework Interpretivist / constructivist framework, including grounded theory concepts Opportunity to explore and generate ideas serendipitous findings Elicits rich-picture, in-depth perspectives Represents multiple voices of participants. www. monash. edu. au 6

3. Method Purposive, theoretical sampling Represents main variables Sample: - 15 research students from Faculty of IT. - participants obtained through lecturers. www. monash. edu. au 7

3. Method Purposive, theoretical sampling Represents main variables Sample: - 15 research students from Faculty of IT. - participants obtained through lecturers. www. monash. edu. au 7

3. Data collection Ethnographic technique - interviews Piloted semi structured interview schedule Revised questions and re-piloted Individual interviews May to December, 2003. www. monash. edu. au 8

3. Data collection Ethnographic technique - interviews Piloted semi structured interview schedule Revised questions and re-piloted Individual interviews May to December, 2003. www. monash. edu. au 8

3. Data analysis Influenced by Charmaz’s (2003) ‘constructivist grounded theory’. Recognises that - ‘the viewer creates the data and ensuing analysis through interaction with the viewed’. - researchers’ backgrounds influence interpretations. Team all involved in developing themes and categories of analysis. www. monash. edu. au 9

3. Data analysis Influenced by Charmaz’s (2003) ‘constructivist grounded theory’. Recognises that - ‘the viewer creates the data and ensuing analysis through interaction with the viewed’. - researchers’ backgrounds influence interpretations. Team all involved in developing themes and categories of analysis. www. monash. edu. au 9

3. Assessing the methodological approach Disadvantages - discursive answers do not fit into easily managed categories - sample size is small, costly in time and money. Advantages - personal meanings can be studied in depth - conveys nuances - explores ‘why’ questions. www. monash. edu. au 10

3. Assessing the methodological approach Disadvantages - discursive answers do not fit into easily managed categories - sample size is small, costly in time and money. Advantages - personal meanings can be studied in depth - conveys nuances - explores ‘why’ questions. www. monash. edu. au 10

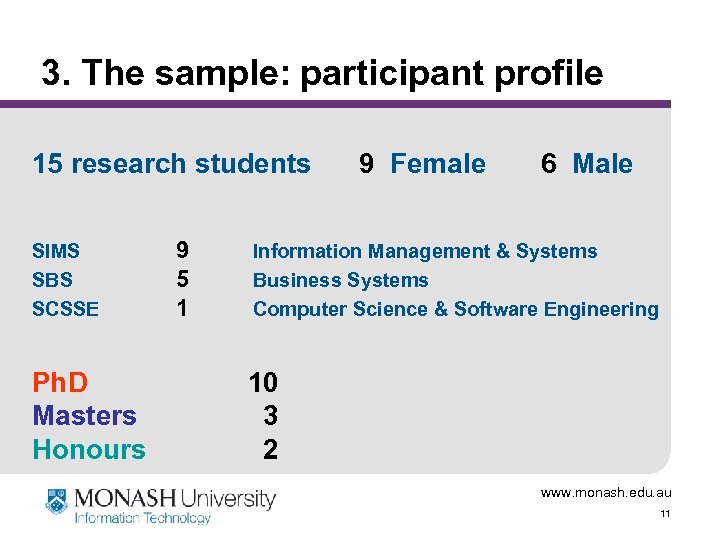

3. The sample: participant profile 15 research students SIMS SBS SCSSE Ph. D Masters Honours 9 5 1 9 Female 6 Male Information Management & Systems Business Systems Computer Science & Software Engineering 10 3 2 www. monash. edu. au 11

3. The sample: participant profile 15 research students SIMS SBS SCSSE Ph. D Masters Honours 9 5 1 9 Female 6 Male Information Management & Systems Business Systems Computer Science & Software Engineering 10 3 2 www. monash. edu. au 11

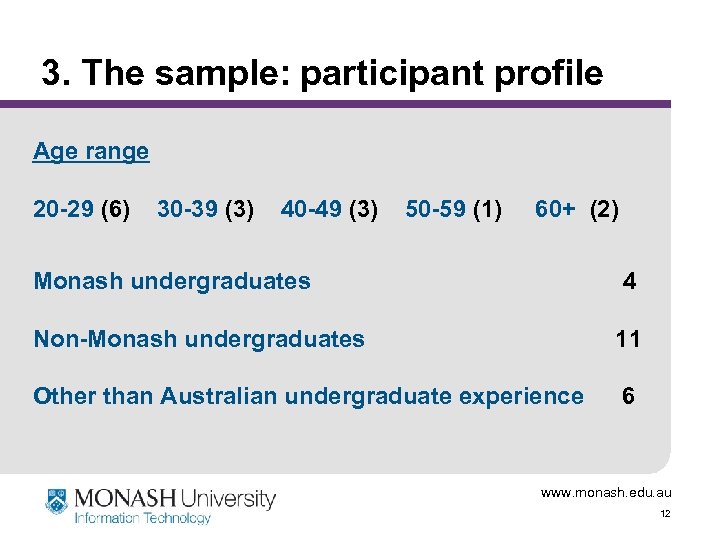

3. The sample: participant profile Age range 20 -29 (6) 30 -39 (3) 40 -49 (3) 50 -59 (1) 60+ (2) Monash undergraduates 4 Non-Monash undergraduates 11 Other than Australian undergraduate experience 6 www. monash. edu. au 12

3. The sample: participant profile Age range 20 -29 (6) 30 -39 (3) 40 -49 (3) 50 -59 (1) 60+ (2) Monash undergraduates 4 Non-Monash undergraduates 11 Other than Australian undergraduate experience 6 www. monash. edu. au 12

4. Findings: Information need Reasons for selection of research topics: – Set by supervisors (Honours) – Often evolved from departmental research projects (Masters) – Chosen for fit with past experience or present interests (Ph. D) Several students mentioned changing direction with their topics and in one case the topic had been totally changed. Information need, particularly in these cases, involved continual re-evaluation. www. monash. edu. au 13

4. Findings: Information need Reasons for selection of research topics: – Set by supervisors (Honours) – Often evolved from departmental research projects (Masters) – Chosen for fit with past experience or present interests (Ph. D) Several students mentioned changing direction with their topics and in one case the topic had been totally changed. Information need, particularly in these cases, involved continual re-evaluation. www. monash. edu. au 13

Use of sources – our study Different needs for different kinds of research projects: ‘Mainly journals because of currency’ (H) ‘It’s great having the Internet because you can find almost anything’ (J) www. monash. edu. au 14

Use of sources – our study Different needs for different kinds of research projects: ‘Mainly journals because of currency’ (H) ‘It’s great having the Internet because you can find almost anything’ (J) www. monash. edu. au 14

Personal information sources – our study Important on one front above all: ‘Yes, I had a lot of support from my supervisor’ (K) ‘[My two supervisors] never agreed on anything … I found the disagreement good most of the time. But sometimes it could be confusing’ (H) www. monash. edu. au 15

Personal information sources – our study Important on one front above all: ‘Yes, I had a lot of support from my supervisor’ (K) ‘[My two supervisors] never agreed on anything … I found the disagreement good most of the time. But sometimes it could be confusing’ (H) www. monash. edu. au 15

Search tools – our study Google sets the standard? ‘Journals online … Google would probably be my second choice’ (A) ‘I do like Google. Even when I search Monash stuff I use Google is fast’ (M) www. monash. edu. au 16

Search tools – our study Google sets the standard? ‘Journals online … Google would probably be my second choice’ (A) ‘I do like Google. Even when I search Monash stuff I use Google is fast’ (M) www. monash. edu. au 16

Search strategies: the Internet – our study At one extreme, there was the following: ‘The more you use [the Internet], the more it will be helpful for you. It is a cumulative effect and it accelerates your searching capabilities. It tells you the searching techniques automatically’ (O) www. monash. edu. au 17

Search strategies: the Internet – our study At one extreme, there was the following: ‘The more you use [the Internet], the more it will be helpful for you. It is a cumulative effect and it accelerates your searching capabilities. It tells you the searching techniques automatically’ (O) www. monash. edu. au 17

Other search strategies – our study A range of approaches here as well: ‘I tend to start in a database and I'll search on keywords. Each one has their own set of keywords’ (A) ‘I look at the volumes searching literally through each volume seeing if any of the articles will interest me’ (B) www. monash. edu. au 18

Other search strategies – our study A range of approaches here as well: ‘I tend to start in a database and I'll search on keywords. Each one has their own set of keywords’ (A) ‘I look at the volumes searching literally through each volume seeing if any of the articles will interest me’ (B) www. monash. edu. au 18

Convenience of access – our study Time, distance, responsibilities: ‘the online library databases are probably the most important thing because they give me access to resources that I couldn’t physically get to otherwise’ (E) ‘It is just easier to go through a general Google search first’ (G) www. monash. edu. au 19

Convenience of access – our study Time, distance, responsibilities: ‘the online library databases are probably the most important thing because they give me access to resources that I couldn’t physically get to otherwise’ (E) ‘It is just easier to go through a general Google search first’ (G) www. monash. edu. au 19

Currency of information – our study Again, subject matter can make a difference: ‘things that were published five years before or one month before is available online so I can be in touch with the current research in a short period of time’ (O) ‘Some of the information is not available in printed form because it is too new to come into print’ (K) www. monash. edu. au 20

Currency of information – our study Again, subject matter can make a difference: ‘things that were published five years before or one month before is available online so I can be in touch with the current research in a short period of time’ (O) ‘Some of the information is not available in printed form because it is too new to come into print’ (K) www. monash. edu. au 20

Knowing when to stop seeking A genuine challenge that evokes uncertainty in many cases: ‘I wish I knew’ (E) [If a given question is answered] ‘I just move on’ (N) ‘that’s something you use your supervisor for’ (G) www. monash. edu. au 21

Knowing when to stop seeking A genuine challenge that evokes uncertainty in many cases: ‘I wish I knew’ (E) [If a given question is answered] ‘I just move on’ (N) ‘that’s something you use your supervisor for’ (G) www. monash. edu. au 21

Evaluating authority of sources and information Once again, a wide spectrum of responses: ‘I know how easy it is to put stuff on the Web … If it doesn’t have that ostensible credibility, then I’m not going to use it’ (D) ‘I always think that what I get online is valid’ (L) www. monash. edu. au 22

Evaluating authority of sources and information Once again, a wide spectrum of responses: ‘I know how easy it is to put stuff on the Web … If it doesn’t have that ostensible credibility, then I’m not going to use it’ (D) ‘I always think that what I get online is valid’ (L) www. monash. edu. au 22

Personal information management From the tightly orchestrated to full-blown improvisation: ‘I print out or photocopy all the articles. I index them. I have a little Access database which I key in the titles and keywords and all the authors and then I can do cross-referencing’ (E) ‘It depends on what kind of mental mood I’m in … The easiest I find is just keep it all in my head and most of the time I will remember, “Oh I read that somewhere, and it’s over there”’ (A) www. monash. edu. au 23

Personal information management From the tightly orchestrated to full-blown improvisation: ‘I print out or photocopy all the articles. I index them. I have a little Access database which I key in the titles and keywords and all the authors and then I can do cross-referencing’ (E) ‘It depends on what kind of mental mood I’m in … The easiest I find is just keep it all in my head and most of the time I will remember, “Oh I read that somewhere, and it’s over there”’ (A) www. monash. edu. au 23

5. Conclusion • Research students – Information literacy needs – Awareness of avenues to address needs • Librarians – Bridge building – Targeted marketing • Information professionals – Research and publication www. monash. edu. au 24

5. Conclusion • Research students – Information literacy needs – Awareness of avenues to address needs • Librarians – Bridge building – Targeted marketing • Information professionals – Research and publication www. monash. edu. au 24

6. References Bruce, C. (1990). ‘Information skills coursework for postgraduate students: investigation and response at the Queensland University of Technology’, Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 21 (4): 224 – 232. Bruce, C. (1997). The seven faces of information literacy. Blackwood: Auslib Press. Charmaz, K. (2003). ‘Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods’, in N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (eds. ), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (2 nd ed. ). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. EPIC (2003. ‘The Electronic Publishing Initiative at Columbia (EPIC) Online Survey of College Students: Executive Summary’, www. epic. columbia. edu/eval/find 09. html, accessed 1 May 2005. Genoni, P. & Partridge, J. (2000). ‘Personal research information management: Information literacy and the research student’, in C. Bruce & P. Candy (Eds. ) Information literacy around the world: Advances in programs and research (pp. 223 -235). Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University. Hazard, H. , Hegarty, F. , & J. Baird (1994). Information Needs of Research Staff and Postgraduate Students at Swinburne University of Technology. Hawthorn, Victoria: Swinburne University of Technology. Heinstrom, J. (2002). Fast Surfers, Broad Scanners and Deep Divers: Personality and Information-Seeking Behaviour. Abo : Abo Akademi Förlag. www. monash. edu. au 25

6. References Bruce, C. (1990). ‘Information skills coursework for postgraduate students: investigation and response at the Queensland University of Technology’, Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 21 (4): 224 – 232. Bruce, C. (1997). The seven faces of information literacy. Blackwood: Auslib Press. Charmaz, K. (2003). ‘Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods’, in N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (eds. ), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (2 nd ed. ). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. EPIC (2003. ‘The Electronic Publishing Initiative at Columbia (EPIC) Online Survey of College Students: Executive Summary’, www. epic. columbia. edu/eval/find 09. html, accessed 1 May 2005. Genoni, P. & Partridge, J. (2000). ‘Personal research information management: Information literacy and the research student’, in C. Bruce & P. Candy (Eds. ) Information literacy around the world: Advances in programs and research (pp. 223 -235). Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University. Hazard, H. , Hegarty, F. , & J. Baird (1994). Information Needs of Research Staff and Postgraduate Students at Swinburne University of Technology. Hawthorn, Victoria: Swinburne University of Technology. Heinstrom, J. (2002). Fast Surfers, Broad Scanners and Deep Divers: Personality and Information-Seeking Behaviour. Abo : Abo Akademi Förlag. www. monash. edu. au 25

6. References Kuhlthau, C. (1991). ‘Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42 (5), 361 -371. Macauley, P. (2001) Doctoral Research and Scholarly Communication: Candidates, Supervisors and Information Literacy. Ph. D Thesis, Faculty of Education, Deakin University, Geelong. Macauley, P. (2000). ‘Pedagogic continuity in doctoral supervision: passing on, or passing by, of information skills? ’, in M. Kiley and G. Mullins (eds. ) Quality in postgraduate research: Making ends meet. Adelaide: Advisory Centre for University Education. OCLC (2002) White Paper on the Information Habits of College Students, June, Dublin, OH: OCLC, http: //www 5. oclc. org/downloads/community/informationhabits. pdf, accessed 17 August 2005. Pilerot, O. (2004). ‘Information Literacy Education for Ph. D Students – a Case Study’, paper presented to the 12 th Nordic Conference on Information and Documentation, www 2. db. dk/NIOD/pilerot. pdf, accessed 17 August 2005. Tenopir, C. , with the assistance of B. Hitchcock and A. Pillow (2003). Use and Users of Electronic Library Resources: An Overview and Analysis of Recent Research Studies. Washington, D. C. : Council on Library and Information Resources. Accessed January 10, 2004. Available www. clir. org/pubs/reports/pub 120. pdf Young, R. & Harmony, S. (1999). Working with Faculty to Design Undergraduate Information Literacy Programs. New York: Neal-Schuman. www. monash. edu. au 26

6. References Kuhlthau, C. (1991). ‘Inside the search process: information seeking from the user’s perspective’, Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42 (5), 361 -371. Macauley, P. (2001) Doctoral Research and Scholarly Communication: Candidates, Supervisors and Information Literacy. Ph. D Thesis, Faculty of Education, Deakin University, Geelong. Macauley, P. (2000). ‘Pedagogic continuity in doctoral supervision: passing on, or passing by, of information skills? ’, in M. Kiley and G. Mullins (eds. ) Quality in postgraduate research: Making ends meet. Adelaide: Advisory Centre for University Education. OCLC (2002) White Paper on the Information Habits of College Students, June, Dublin, OH: OCLC, http: //www 5. oclc. org/downloads/community/informationhabits. pdf, accessed 17 August 2005. Pilerot, O. (2004). ‘Information Literacy Education for Ph. D Students – a Case Study’, paper presented to the 12 th Nordic Conference on Information and Documentation, www 2. db. dk/NIOD/pilerot. pdf, accessed 17 August 2005. Tenopir, C. , with the assistance of B. Hitchcock and A. Pillow (2003). Use and Users of Electronic Library Resources: An Overview and Analysis of Recent Research Studies. Washington, D. C. : Council on Library and Information Resources. Accessed January 10, 2004. Available www. clir. org/pubs/reports/pub 120. pdf Young, R. & Harmony, S. (1999). Working with Faculty to Design Undergraduate Information Literacy Programs. New York: Neal-Schuman. www. monash. edu. au 26